The Transportation Bond Act: Vote No

Gotham is an old city with an aging physical infrastructure. But the state’s $2.9 billion Transportation Bond Act, which will be on the November 8 ballot as “Proposal No. 2,” is not the best way for New York City to get the money it needs for its vital transportation assets.

The city certainly does need money for its mass transit, roads and bridges. New York’s subway system, parts of which turned 100 years old last year, needs $18 billion in investment over the next four years just to maintain its current state of repair. More than half of the city’s bridges are considered to be in less-than-stellar condition, and some are actively deteriorating.

But the transportation bonds on the ballot, if approved, will be issued by the state, not the city. The state doesn’t have infinite funds, and thus should make each dollar go a long way. But, despite this, it has not prioritized its proposed transportation-infrastructure investments according to urgent need.

THE CITY’S SHARE

What does this mean for New York City?

The city’s subways, roads and bridges will receive about $1.6 billion of the bond proceeds. At 55 percent of the total, this doesn’t sound like such a bad deal – especially in light of the fact that city residents, workers and businesses pay a little less than half of state taxes.

But the problem is that of that $1.6 billion earmarked for New York City, the bonds provide only about $700 million in funding for projects that the city needs completed now. So, in effect, New York City taxpayers will pay about $1.3 billion (their share of state taxes to fund the bond issue) in order to get back about half that in investment so critically necessary that it justifies new debt.

To wit: The bond act would provide the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority with $450 million to maintain the MTA’s core infrastructure, much of it within New York City. This means hundreds of millions of dollars for such mundane but crucial investments as new subway cars and buses, track replacement, tunnel lighting and other maintenance.

BIG TICKET ITEMS

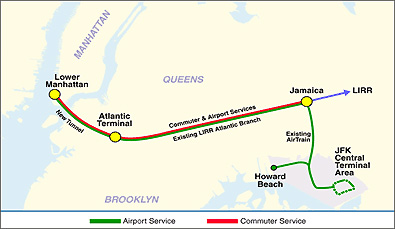

But the bond act would provide a further billion dollars for several pie-in-the-sky expansion projects at the MTA: $450 million each for the Second Avenue subway (from the Bronx to Lower Manhattan) and for the East Side Access project (to connect Long Island Rail Road commuters to the East Side of Manhattan), and $100 million for a rail link from Lower Manhattan to Kennedy Airport.

Any one of these expansion projects might be worth seeing through to completion – but neither the city nor the state has committed to doing that. The Second Avenue subway, for example, will cost $16 billion.

In a rational world, the city and state would pick one of these projects – and make room in the budget to raise the capital necessary to build it. But each Albany official has his pet New York City project (Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver likes the Second Avenue Subway, while Governor Pataki likes the rail link to JFK), so no single project ever gets enough funds to make real progress.

Until the state and the city can figure out which of these three multibillion-dollar projects it likes best, the MTA would do better to commit the entire $1.45 billion raised through the transportation bond act to making critical investments in the assets it already has, to ensure that New Yorkers can depend on a reliable transportation system.

IMPROVING ROADS

What about roads? Of $1.45 billion earmarked for roads and bridges statewide, the city will get $273 million, or 19 percent. Some of the projects involve work on critical arteries in and out of the city: $81 million to rehabilitate the Van Wyck Expressway in Queens and $23 million to make repairs to the Henry Hudson Parkway between Manhattan and the Bronx. But at least one major project is not quite so critical: $19 million for a “green oasis” in the Bronx.

And to get its $273 million, the city must help pay for $1.2 billion road projects outside the city, including $21.5 million for 11 miles of new hiking trails in Washington County and a new pedestrian bridge near the Erie Canal.

CONTROLLING STATE SPENDING

These initiatives, and dozens of relatively small upstate road projects, may indeed be worthy – and no one is suggesting that upstate be deprived of infrastructure critical to its economy, or that the congested Bronx be deprived of green space.

But the state has so badly mismanaged its finances in recent years that it already has far too much long-term debt: more than $48 billion, which puts it fifth in the nation in terms of debt per person. According to state Comptroller Alan Hevesi, only about half of that debt was for prudent investment in long-term capital assets like transportation infrastructure – another 20 percent was for day-to-day operations, and another 25 percent was to fund state and local programs that should be paid for upfront.

Thus, it is not prudent for the state to raise new debt for worthy “extras.” Every penny should go toward the critical infrastructure that is badly in need of maintenance and repair.

Hiking trails and greenways are great – but the taxpayers who want them should pressure their local politicians to pressure Albany to get the state budget under control, so that we can afford to help pay for them without breaking the bank. If Albany were to cut its bloated and fraudulent Medicaid program by 15 percent, for example, state and local governments would have an extra $3 billion each year to fund smaller capital projects upfront.

Until then, city taxpayers would do better to vote down the Transportation Bond Act, and Gotham would do better to raise $700 million in debt on its own to pay for critical investments in its roads, and to help the MTA pay for critical investments in the subway.

This would send Albany a message: No more debt until state leaders reform the budget to get the debt we have under control.

Nicole Gelinas, a chartered financial analyst, is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor to City Journal magazine.

• • • • • • •

• The Transportation Bond Act: Vote Yes by Jeremy Soffin

• • • • • • •

For more information against the Transportation Bond Act:

• CBC Announces Opposition To Transportation Bond Act (in .PDF format)

A statement from the Citizens Budget Commission

• New York's Endangered Future: Debt Beyond Our Means (in .PDF format)

A report on state borrowing by the Citizens Budget Commission

• Vote No

A position paper by the Conservative Party of New York

• Staten Island Borough President Opposes Transportation Bond Act

• No on Prop 2

A New York Post editorial Â

Transportation Bond Act

With mayoral candidates giving little attention to transportation issues, voters' biggest choice in the transportation arena will be their vote on the 2005 Transportation Bond Act. The bond act, approved by the Legislature this spring as part of a 5-year, $36 billion capital plan, would authorize $2.9 billion in state-backed borrowing for transportation, to be repaid through general revenues. One-half of the bond act funds would be dedicated to public transportation in New York City and its suburbs. Projects to be funded include:

• $450 million to move ahead with the Second Avenue Subway

• $450 million for the East Side Access project, connecting the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal;

• $100 million for a rail link between lower Manhattan and Kennedy airport;

• $115 million for purchase of new subway and commuter railroad cars;

• $90 million for new buses; and

• $161 million for track replacement and tunnel lighting. An additional $235 million is set aside for upstate public transportation systems.

Although many people think of New York City as synonymous with transit and upstate as synonymous with highway spending, in fact, a substantial amount of statewide highway spending goes to New York City projects. Twenty-three percent of the bond's highway funding will be spent in the city. New York City highway projects (In PDF Format) include:

• $81 million for Kew Gardens Interchange/Van Wyck Expressway Improvements;

• $30 million for closed circuit television cameras, electronic message signs, vehicle detection devices and highway advisory radio on the FDR Drive and Henry Hudson Parkway;

• $23 million for Henry Hudson Parkway Rehabilitation;

• $25 million for West Shore Expressway Access and Safety Improvements;

• $19 million for the Bronx River Greenway; and

• $11 million for Long Island Railroad Bridge Upgrades to allow heavier, larger rail cars to access the Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island market areas.

Bond act spending also aims to maintain the percentage of state highway bridges in New York City that are rated as in good or excellent condition and slightly improve the proportion of interstate highway lane mileage in New York City that is rated as in good or excellent condition.

No one seriously disputes the importance of maintaining and upgrading the state's transportation system. The Bond Act has thus attracted a long list of supporters including Governor George Pataki, Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, and transit advocacy, environmental and civic groups, including the NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign and the New York Public Transit Association. Both Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his opponent, Fernando Ferrer, support the bond act.

Supporters say that the Transportation Bond Act funds are vital to maintaining the state's sprawling and aging transportation infrastructure. The funding is also critical to construction of the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access -- projects long discussed and planned but only now garnering the necessary funding. As much as $4 billion in federal funding is contingent on the bond act passing since the federal government evaluates projects on the level of local financial support. Supporters also point out that bond act spending will create construction jobs in the short term and spur economic growth for years to come.

The bond act has also attracted opposition, primarily from groups that feel the state already has too much debt. The Citizens Budget Commission (In PDF Format) says that the state is poised to take on $19 billion in new debt in the next five years. Only the $2.9 billion in the bond act requires voter approval, however. The budget commission argues that voters should reject the bond act as the only way to say no to the overall growth in borrowing.

The Automobile Club of New York also urges voters to reject the Transportation Bond Act. The Auto Club criticizes the state for raiding the highway trust fund, whose revenues come from the gas tax and auto registration fees. The Auto Club says that the state has used trust fund revenues to plug general budget shortfalls. The Auto Club argues that instead of borrowing to pay for transportation improvements, the integrity of the trust fund should be maintained and used for these projects.

Supporters reply that the real choice -- aside from underfunding transportation -- is between state-backed borrowing and borrowing that would be paid back through transit fares. They point out that after the 2000 Bond Act failed, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority borrowed heavily, leading to two fare increases since then.

In 2000, a $3.8 billion Transportation Bond Act narrowly failed to win voter approval. Prospects for this year's proposal are uncertain. A recent Quinnipiac University poll found voters statewide supporting the measure by a 56 percent to 36 percent margin. New York City voters supported it by 67 to 26 percent and suburban voters by 60 to 32 percent. Upstate voters were about evenly split.

While encouraging to supporters, these poll numbers also provide reason for caution because polls before the 2000 election also showed a majority in support. On election day, many New York City voters "who would be expected to vote favorably" overlooked the proposition in the lower right corner of the ballot. In fact, had the dropoff from the presidential vote to the bond act vote been the same downstate as upstate in 2000, the measure would have passed.

Supporters are aiming to heed the lessons of 2000. A group of business and building associations has funded a statewide Vote Yes for Transportation campaign. The $1.5 million campaign will include door to door canvassing and upstate radio ads.

Supporters have also moved to shore up support on Staten Island. The MTA recently shifted funds to build a third MTA bus depot on the island after the borough president, James Molinaro, criticized the measure.

Chances for passage of the 2005 Bond Act appear to be better than the 2000 measure, which failed narrowly, but are not assured. Voters thus have an important and very real choice to make on November 8.

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Mayoral Issue Grid: Transportation

TRANSPORTATION

-2nd Ave Subway

-7 Extension

-Rail Link from Lower Manhattan to JFK Airport

-Rail Freight tunnel

-East River Tolls

-Congestion Pricing

-Subway Commute?

The last new subway line opened in New York City nearly 65 years ago, but candidates for mayor are making bold promises to undertake new mass transit plans.

For years, officials have been promising a Second Avenue Subway. It was first proposed in the 1920s. Recently, the MTA committed $1 billion for the subway line that would run from 125th Street to Hanover Square. It will cost an estimated $12.5 billion and take 17 years to build.

As part of his plan to develop the West Side of Manhattan, Mayor Michael Bloomerg has also proposed an extension of the number 7-subway line to 11th Avenue. It will cost an estimated $2 billion.

In Lower Manhattan, officials have plans to build a direct rail link from downtown to John F. Kennedy airport.

Some officials are also calling for a cross-harbor rail tunnel to be built between New Jersey and Brooklyn. The 5.5-mile tunnel would ship goods into the city and reduce truck traffic on area roads. As part of a new federal transportation funding bill, U.S. Rep. Jerrold Nadler secured $100 million to help launch the project.

While there are tolls on many bridges and tunnels in New York City, there are 12 city-owned bridges between Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx that are free to cross. Some estimate that charging $7 to cross the East River bridges and $3 for the Harlem River bridges could generate as much as $690 million a year.

Another way to reduce traffic and pollution is called "congestion pricing," charging drivers varying prices to come into the city at certain times of day. The city of London has instituted congestion pricing, charging people higher fees for driving in and out of the city at rush hour. The practice has reduced traffic in the city by 30 percent.

When running for office in 2001, Michael Bloomberg committed to ride the subway to City Hall to demonstrate his commitment to the environment and to public transportation.

Fernando Ferrer supports the construction of the Second Avenue subway and the 7-train extension to the West Side of Manhattan.

He is also a supporter of the cross-harbor freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn.

Ferrer is opposed to tolls on the East River bridges. At a recent forum he said, "Tolls on the East River bridges, even Mike Bloomberg walked away from that because he knows one other thing: There are people in this city who work hard every day who depend on their vehicles to make deliveries or get in to work. We've got to find a way to get them to use mass transit. But I'm not going to be the one to say they can't earn a living in New York City."

However, Ferrer does support congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the New York League of Conservation voters, he wrote; "I do favor a congestion pricing policy, but one that is part of a larger framework; a framework which incorporates an expanded freight rail system, an efficient subway system, and an expanded ferry system."

At a recent forum, Ferrer said, if elected, he would take the subway from Gracie Mansion to City Hall.

Michael Bloomberg has expressed general support of the Second Avenue subway line, but has spent considerable effort on the plan to extend the 7-train, because it was part of his plan for a West Side stadium.

Bloomberg supports a lower Manhattan rail link to JFK, which he called “the single most important project for the future of Lower Manhattan” in his 2005 State of the City address

In March, Mayor Bloomberg withdrew city support for the cross-harbor rail freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn. Some residents of Brooklyn are opposed to the project because they say it will bring more traffic and pollution to their neighborhood. Bloomberg says he now agrees with them.

Bloomberg proposed tolling the East River bridges to help raise money during the fiscal crisis, but he dropped the idea.

Bloomberg is open to the idea of congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the League of Conservation Voters, Bloomberg wrote; "To determine the feasibility and effectiveness of implementing a congestion pricing program, the administration is closely studying the impact of London's program on that city's traffic congestion, as well as any corollary effects of the policy. While London's program has reduced traffic congestion dramatically in the business district, according to reports by the London Chamber of Commerce and the Royal Institute for Chartered Surveyors, there has been a significant decrease in business activity in the area since the policy was introduced. The program's high operating costs have also limited the city's net revenue. We will continue to study the issue, but will not implement such a policy that could have a deleterious effect on local businesses."

Mayor Bloomberg regularly takes the subway from his house on the Upper East Side to City Hall.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Security and the NYC Subways

- The State Budget’s $38.5 Billion Transportation Program

- What's Better, What's Worse During Bloomberg's Administration?

- Rail Freight Tunnel

- New Subway Projects and Their Benefits

- The Proposed Trains to Planes

Â

Katrina's Wake-Up Call For New York?

Could a disaster like Hurricane Katrina happen in New York City? If it did, could New Yorkers find the transportation they need to move to safety?

“If we don't view Katrina as a wake-up call in New York City and surrounding areas, then we are fooling ourselves," Assemblyman Richard Brodsky, chairman of the committee that oversees the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, declared (as reported in Newsday and the Daily News ), when he released a report this month critical of the MTA’s evacuation plans.

Although hurricanes are less common in New York than in Florida and along the Gulf Coast, the city is still quite vulnerable. Major hurricanes have hit the metro area in 1938, 1954 and 1999. In 1821, a hurricane raised the tide 13 feet in an hour in the city. A hurricane expert at Queens College, Nicholas Coch, says that a major hurricane in the city is “inevitable.”

The key failure in New Orleans was the failure of the city to evacuate residents of its low-lying areas. Louisiana’s emergency operations plan, adopted in 2000, recommended that cities use public transportation to evacuate residents if necessary. Yet as the Houston Chronicle reported, the city of New Orleans emergency management plan suggested that people develop their own way to get out. But many poor residents living in the lowest lying areas of New Orleans do not have a car and were thus left stranded at the same time that the city left 550 buses sitting idle.

A second key failure in New Orleans was not ordering evacuation sooner. Mayor Ray Nagin issued the order at 10 a.m. Sunday for a storm expected to hit Monday morning. That left inadequate time for the evacuation to proceed, especially for people in hospitals and other special needs populations.

New York is in many ways less vulnerable to a hurricane than was New Orleans. While much of New Orleans is below sea level and thus relies on levees and pumps to stay dry, New York is above sea level. Even if inundated, the city will drain dry in a few days. Thus, even in the worse case, residents could return home in a matter of days instead of months.

On the other hand, there are a whole lot more people to evacuate in New York than in New Orleans. But unlike the plan in New Orleans, the New York emergency evacuation plan emphasizes the use of public transportation. Residents of low-lying areas in Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island and the Bronx would be urged to use trains and buses to move to friends or relatives on higher ground or to go to one of 20 “reception” centers around the city – many without any parking whatsoever. City officials would then channel evacuees to up to 300 shelters.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has said that, “We have ways to call and get MTA buses to take residents who likely wouldn’t have cars or money for transportation.” With most outlying areas of the city lacking direct subway service, buses would presumably be the primary mode for evacuees. How buses would be deployed, where they would run or how quickly residents could get to shelters is not clear from the emergency plan on the city’s Web site, however.

New York’s plan explicitly urges residents not to use their automobiles. The plan recognizes that roads will be jammed and the trip will be very long. If you do drive, the plan advises that you make sure you have a full tank of gas.

Would there be time to evacuate? That depends on when the order is issued and how quickly residents pack up and go. Bloomberg has made clear that he would use forcible means to evacuate residents if necessary. Whether he or another mayor would order a disruptive evacuation 36 or more hours in advance – when no one knows whether the storm will divert from the city – cannot be known in advance.

Could it happen here? The city seems better prepared and better positioned to handle a major hurricane than was New Orleans. If fully deployed, city buses could move tens of thousands of people over a 36 hour evacuation period. But the human response –- when a mayor issues the order to evacuate, whether residents would voluntary leave their homes -– is as key an unknown in New York as it was in New Orleans.

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

42nd Street

|

Forty years ago, New York reacted to the loss of old Pennsylvania Station by passing a law to protect city landmarks. This series, in partnership with Open House New York, looks at the physical city since the birth of the preservation movement. |

Famed Broadway director Hal Prince was horrified when he visited the New Amsterdam Theater on 42nd Street in 1986, 83 years after it really was new: "I will not lie to you," he wrote to the owner. "That can be the best legit theater in New York City and of course it would have been ideal for Phantom of the Opera. But there is no way I would go near 42nd Street or ask anyone else to."

Why wouldn't he?

"While we were waiting in front of the theater," he explained, "on one side of us a drug sale took place, and on the other..." something salacious.

Two decades later, Matthew Postal was also horrified when he visited the newly New Amsterdam Theater, which for the last seven years has been home to Disney's The Lion King, but horrified for a completely different reason.

"What they did at the New Amsterdam Theater is astonishing, preserving the building and bringing it back to life," said Postal, an architectural historian who gives a midnight tour of Times Square called "Peeling Back the Neon." "But as you walk further west, it's horrific. I don't have any reason to go there."

Why wouldn't he?

"It's completely for tourists," he explained.

And there it is - the new 42nd Street versus the old 42nd Street.

On the old 42nd Street, the marquee on the Victory Theater promised "Best Porn XXX in Town." On the new 42nd Street, the theater, renamed the New Victory Theater, doesn't even have a marquee anymore; it was restored to its original turn-of-the-century, pre-porn look, and is now a children's theater.

On the other hand, the old 42nd Street had theaters with names like Lyric and Apollo, the Greek god of the sun. On the new 42nd Street, those two theaters have been merged and renamed not after Greek gods but a succession of corporate ones -- first a car manufacturer (Ford), then a hotel chain (Hilton). It is currrently operated by Clear Channel, one of the largest media conglomerates on the planet.

On the old 42nd Street -- way back in the 1920s -- visitors to the city attended the Liberty Theater to see Fred Astaire or Jeanette MacDonald. On the new 42nd Street, they go to Madame Tussaud's Wax Museum to see a replica of Fred Astaire.

And on 41st Street and Eighth Avenue, where there used to be a student dormitory, the state used its power of eminent domain for the "public purpose" of building a new headquarters for the New York Times. The 52-story building will even bar tenants with actual public purposes, such as a social service office, a court-related facility, a medical clinic, or even a school.

Ten years after the old 42nd Street -- sleazy and scary -- started being transformed into "The New 42nd Street" -- cleaned-up, crime-free, and corporate -- all the critical questions of urban planning facing the city seem to be playing out on that one famous street.

ADDRESSING CRIME THROUGH PLANNING

Each Friday, Judy Richheimer gives a free tour of Times Square on behalf of the Times Square Alliance, and each week she begins by asking, "What is the first thing that comes to mind when I say Times Square?"

"Red light district," said one man on a recent tour.

"High crime," said another.

Richheimer nodded. Although neither of these things are still the case, she said, they are still the answers she gets most frequently. Indeed, the tour group is still accompanied by a safety officer "in case someone thinks a three-card monte player is going to grab them or something."

Times Square is still living down a reputation, earned in the 1970s, of world headquarters for sleaze.

The two police precincts in the area had the highest crime rates in the city, with a murder occurring almost every day. The New York Times described its own neighborhood as a "boulevard of filth" and a "sordid and dangerous place."

After years of trying to address crime by hiring more police or cracking down on prostitution or drugs, city officials tried a different approach: they set out to remake the physical landscape of a 13-acre area of 42nd Street from Broadway to Eighth Avenue.

In 1979, the first grand scheme for the area was entitled "The City at Forty-second Street." It called for a gigantic indoor mall with "educational, entertainment, and exhibits" and 2.1 million square feet of retail shopping connected by aerial walkways and a monorail. The notion was to create a controlled environment where business people and shoppers would feel safe, separated from the street below.

Mayor Ed Koch dismissed the proposal as "Disneyland at 42nd Street" and argued that people wouldn't come to Times Square to ride a ferris wheel. The plan was scrapped.

In 1983, another plan emerged. Architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee proposed building four massive office towers in Times Square that would house law firms and other corporate clients.

The plan had the support of the city and state, but it met strong opposition from those with vested interests in the area.

Powerful real estate families like the Bradts and the Dursts, who owned many of the properties in the area, filed dozens of lawsuits to block the new buildings. The Municipal Art Society, concerned that Broadway may come to resemble the office towers of Sixth Avenue, worked to create a law that mandates a minimum amount of lit billboards on each block. And the arts community rallied to save the area's historic theaters.

The legal battles lasted for ten years and the developers eventually won their case. But by that time, many of the original investors no longer wanted to be part of the project.

But out of the process city offices gained powerful tools: zoning regulations to drive out porn and sex shops, the approval for taller buildings, and the power to condemn private property for its own use.

THE NEW VICTORY THEATER: PRESERVING HISTORY

In 1990, ten years after the first failed plan, the city launched a new effort called The New 42nd Street, a non-profit group charged with reviving seven old theaters and luring new businesses to the area.

|

|

Cora Cahan, who had a background in the arts and fundraising, was chosen to head up the project. The first challenge was restoring the Victory Theater, the oldest theater in Manhattan.

The theater, originally called the Republic, was built by Oscar Hammerstein in 1900, and was successful until the Great Depression. In the 1930s, it was a burlesque theater and in the 1950s it featured first run films. By the 1970s, it became the first porn theater on 42nd Street.

In her office, Cahan still keeps a giant picture of the theater taken in 1987, when it screened titles like "French Orgy" and "Scent of Sex."

|

|

In an act of defiance, the board of directors of New 42nd Street voted to turn the sleezey Victory into a quaint children's theater. The 16-month renovations cost $11.4 million and when it opened in 1995, the theater was restored largely to its original state, with a domed ceiling and marble staircase.

"This little theater heralded a change on a famous - and often infamous - block," said Cahan. Now, instead of "Scent of Sex," the theater offers shows like "Twinkle Twinkle Little Fish" and "Dear Fizzy."

THE NEW AMSTERDAM: A MARRIAGE OF CORPORATIONS AND THE ARTS

With the New Victory Theater's redevelopment underway, the city and state began negotiations with a powerful new tenant. Disney CEO Michael Eisner was looking for a place to showcase a Broadway production of Beauty and the Beast, and the city brought him to look at the New Amsterdam Theater.

|

|

The New Amsterdam, which opened in 1903 and was later home to the Ziegfeld Follies, had been abandoned. The previous owner, who had wanted to knock the theater down and put in parking garage, walked away after the Landmarks Commission declared it a historic landmark.

When Eisner toured the theater, there was a giant hole in the roof, ice waterfalls had formed on the box seats, and a tree was growing out of the orchestra pit.

After two years and $38 million in renovations, the New Amsterdam opened in 1997. In 1998, the Lion King opened, earning six Tony Awards, including "Best Musical."

Tapping into corporations who wanted to be associated with the street's revival - and wanted to sell their products to the tourists now flocking to the area - proved to be a successful model. And it was replicated all along the street.

Developer Forest City Ratner moved the entire 3,700-ton Empire Theater 168 feet down 42nd Street, then merged it with the Liberty and the Harris theaters to create a five-story entertainment complex, which includes a 25-screen AMC movie theater and Madame Tussuad's Wax Museum.

Livent, a Toronto-based theater company, agreed to merge two theaters, the Lyric and Apollo, into a new 1800-seat Ford Center for the Performing Arts. The building is currently operated by the media company Clear Channel and was recently renamed Hilton Theater.

The Roundabout Theater Company agreed to restore the Selwyn Theater, which was renamed the American Airlines Theater.

In 2000, New 42nd Street launched a new project, a ten-story building of rehearsal spaces and offices called the New 42nd Street Studios, and a 199-seat theater called Duke on 42nd Street.

"We claimed a place for the city's performing artists in the middle of 42nd Street," said Cahan. "It's a building where people can create work in the best of circumstances."

But the studio and performance space for artists is only possible because companies like Clear Channel, Reuters, and Ecko Unlimited help pay rent to New 42nd Street. And in order to lure these kinds of companies, the city offered significant tax breaks and subsidies.

THE NEW YORK TIMES AND EMINENT DOMAIN

One of the final aspects of the area's revival is 41st Street and Eighth Avenue, where the New York Times is currently building its new headquarters.

|

|

Developer Forest City Ratner believes that the 52-story building, designed by architect Renzo Piano, will not only be a significant addition to the area, but will stand out as one of the city's enduring sky-scrapers. (They have even hired photographer Annie Leibovitz to document the construction, as Lewis Hines did with the Empire State Building and Margaret Bourke-White did for the Chrysler Building.)

The building features translucent glass that the architect says will reflect the "transparent" nature of the namesake tenant. It also includes a 350-seat auditorium for civic and community events and an open-air garden.

Developers also believe the building will help lead to a similar revitalization of the area west and south of 42nd Street.

"It is a stepping-stone to all of the rezoning on the West Side, the Javits Center, and projects up and down Eighth Avenue," said James Stuckey, a vice president for Forest City Ratner. "In many ways, it has allowed the plan unveiled in the Koch years to come into its full glory."

But critics question how the state can justify the use of eminent domain to build a building that bans many public uses like classrooms, employment agencies, or medical offices.

They also say the public is paying too much of the cost.

Developers of the New York Times building will get $26 million in tax breaks and subsidies, and they are reportedly seeking $170 million more.

"Thanks to a deal with the Pataki and Giuliani administrations, The New York Times Company is in line to get a choice midtown property at tens of millions of dollars below market value - and city taxpayers will foot the difference," Paul Moses wrote in the Village Voice.

MEASURING 42ND STREET

The transformation of 42nd Street in the last ten years is, by any measure, astounding.

The area is remarkably safe (although crime across the city is also at record lows and many still argue over exactly what has lead to the decline.) Nearly 60,000 people a day walk down the street, up 45 percent from five years ago. There are 5,000 theater seats on 42nd Street, which had not been the case since the 1930s. The street boasts two hotels and two huge movie cineplexes, including the AMC Empire 25, which its owners claim is the single most lucrative movie theater in the nation. Not to be outdone, the McDonalds on the block bills itself as the world's largest.

That, critics say, is part of the problem. The new 42nd Street resembles exactly what New Yorkers didn't want it to be, what public officials rejected in the 1980s.

It is indeed the tourist theme park that Koch derided as "Disneyland on 42nd Street"; not only is Disney itself programming much of the entertainment on the street, there is even literally a ferris wheel, around the corner at the Times Square Toys R Us (which -- no surprise -- bills itself as the world's largest toy store).

"Las Vegas and Times Square had very little in common 40 years ago; now they bear a strong family resemblance," wrote James Traub, author of The Devil's Playground, a book on the history of Times Square.

And the giant office towers that so many fought against for a decade now dominate the area. "The tall buildings that line Broadway look a lot like the tall buildings that line Third Avenue and have much the same tenants," said Traub.

The revival has also come at a steep price for taxpayers.

The renovations of the Times Square subway station cost an estimated $180 million. The 42nd Street Economic Development Corporation says it spent $140 million to acquire and knock down old buildings. And many companies in city-owned buildings - like Disney in the New Amsterdam - are charged below market rate rents.

But Times Square is not just any neighborhood. Battles among artists, corporations, real estate developers, and politicians have been playing out there for over a hundred years - and they will continue in the future.

"Ultimately, it is in the spirit of what it has been for 100 years," says Matthew Postal. "It was a relatively user friendly, over the top, commercial place in 1920. And that is what it is now."

MORE LINKS:

Times Square Alliance

New 42nd Street Project

New Amsterdam Theater

Victory Theater

The Duke on 42nd Street

New New York Times Building

Interactive Timeline of Times Square

RELATED BOOKS:

Times Square Roulette by Lynne B. Sagalyn

The Devil's Playground by James Traub

Mayoral Issue Grid: Transportation

TRANSPORTATION

-2nd Ave Subway

-7 Extension

-Rail Link from Lower Manhattan to JFK Airport

-Rail Freight tunnel

-East River Tolls

-Congestion Pricing

-Subway Commute?

The last new subway line opened in New York City nearly 65 years ago, but candidates for mayor are making bold promises to undertake new mass transit plans.

For years, officials have been promising a Second Avenue Subway. It was first proposed in the 1920s. Recently, the MTA committed $1 billion for the subway line that would run from 125th Street to Hanover Square. It will cost an estimated $12.5 billion and take 17 years to build.

As part of his plan to develop the West Side of Manhattan, Mayor Michael Bloomerg has also proposed an extension of the number 7-subway line to 11th Avenue. It will cost an estimated $2 billion.

In Lower Manhattan, officials have plans to build a direct rail link from downtown to John F. Kennedy airport.

Some officials are also calling for a cross-harbor rail tunnel to be built between New Jersey and Brooklyn. The 5.5-mile tunnel would ship goods into the city and reduce truck traffic on area roads. As part of a new federal transportation funding bill, U.S. Rep. Jerrold Nadler secured $100 million to help launch the project.

While there are tolls on many bridges and tunnels in New York City, there are 12 city-owned bridges between Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx that are free to cross. Some estimate that charging $7 to cross the East River bridges and $3 for the Harlem River bridges could generate as much as $690 million a year.

Another way to reduce traffic and pollution is called "congestion pricing," charging drivers varying prices to come into the city at certain times of day. The city of London has instituted congestion pricing, charging people higher fees for driving in and out of the city at rush hour. The practice has reduced traffic in the city by 30 percent.

When running for office in 2001, Michael Bloomberg committed to ride the subway to City Hall to demonstrate his commitment to the environment and to public transportation.

Fernando Ferrer supports the construction of the Second Avenue subway and the 7-train extension to the West Side of Manhattan.

He is also a supporter of the cross-harbor freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn.

Ferrer is opposed to tolls on the East River bridges. At a recent forum he said, "Tolls on the East River bridges, even Mike Bloomberg walked away from that because he knows one other thing: There are people in this city who work hard every day who depend on their vehicles to make deliveries or get in to work. We've got to find a way to get them to use mass transit. But I'm not going to be the one to say they can't earn a living in New York City."

However, Ferrer does support congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the New York League of Conservation voters, he wrote; "I do favor a congestion pricing policy, but one that is part of a larger framework; a framework which incorporates an expanded freight rail system, an efficient subway system, and an expanded ferry system."

At a recent forum, Ferrer said, if elected, he would take the subway from Gracie Mansion to City Hall.

C. Virginia Fields believes the Second Avenue subway should be the city’s top priority.

She also supports an extension of the 7-subway line.

She is a supporter of the cross-harbor freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn.

Fields is opposed to tolls for East River bridges. At a recent forum, she said, "I think that it would be strictly unfair to people who live in this city and have to pay from Brooklyn just to come into Manhattan or from other areas. And I don't think that that is the way that we should look to improve our transportation system." Fields says she supports congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the New York League of Conservation Voters, she wrote; "London is the world-wide exemplar of this strategy, and its mayor, Ken Livingstone survived tremendous initial resistance to now be congratulated for significantly easing congestion and reducing travel times."

At a recent forum, Fields said, if elected, she would not take the subway from Gracie Mansion to City Hall.

Gifford Miller says his number one transportation goal is to conduct a repair and modernization program of the subway system.

Miller has campaigned for the Second Avenue Subway, as well as the 7-subway line extension to the west side of Manhattan.

Miller is also a supporter of the cross-harbor freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn. (Read Millers’ plan for transportation)

Miller is opposed to tolls on the East River bridges.

At a recent forum, Miller did not directly answer a question about congestion pricing. He told the New York League of Conservation Voters that he would consider it in a pilot program.

At a recent forum, Miller said, if elected, he would not take the subway from Gracie Mansion to City Hall. "It's a long walk from Gracie Mansion," he said.

Anthony Weiner’s top transportation priorities are expanding high-speed ferry service and developing a “Rapid Transit” bus system.

Weiner supports the Second Avenue subway and the extension of the number 7 subway line to the west side of Manhattan.

While Weiner supports the idea of the JFK Air Train rail link, he expressed concerns about getting people to use it.

Weiner is also a supporter of the cross-harbor freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn. (Read Wieners’ transportation plan)

At a recent forum when Weiner was asked about tolls on the East River bridges, he did not answer the question. He said the city should use more ferry service.

Weiner is opposed to congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the League of Conservation Voters he wrote: "Charging commuters more during peak hours may help reduce traffic by a couple of minutes. But a comprehensive policy is needed to encourage greater use of environmentally-friendly public transportation."

At a recent forum, Weiner said, if elected, he would take the subway from Gracie Mansion to City Hall.

Michael Bloomberg has expressed general support of the Second Avenue subway line, but has spent considerable effort on the plan to extend the 7-train, because it was part of his plan for a West Side stadium.

Bloomberg supports a lower Manhattan rail link to JFK, which he called “the single most important project for the future of Lower Manhattan” in his 2005 State of the City address

In March, Mayor Bloomberg withdrew city support for the cross-harbor rail freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn. Some residents of Brooklyn are opposed to the project because they say it will bring more traffic and pollution to their neighborhood. Bloomberg says he now agrees with them.

Bloomberg proposed tolling the East River bridges to help raise money during the fiscal crisis, but he dropped the idea.

Bloomberg is open to the idea of congestion pricing. In a questionnaire for the League of Conservation Voters, Bloomberg wrote; "To determine the feasibility and effectiveness of implementing a congestion pricing program, the administration is closely studying the impact of London's program on that city's traffic congestion, as well as any corollary effects of the policy. While London's program has reduced traffic congestion dramatically in the business district, according to reports by the London Chamber of Commerce and the Royal Institute for Chartered Surveyors, there has been a significant decrease in business activity in the area since the policy was introduced. The program's high operating costs have also limited the city's net revenue. We will continue to study the issue, but will not implement such a policy that could have a deleterious effect on local businesses."

Mayor Bloomberg regularly takes the subway from his house on the Upper East Side to City Hall.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Security and the NYC Subways

- The State Budget’s $38.5 Billion Transportation Program

- What's Better, What's Worse During Bloomberg's Administration?

- Rail Freight Tunnel

- New Subway Projects and Their Benefits

- The Proposed Trains to Planes

Campaign 2005: Democratic Mayoral Candidates' Transportation Agendas

Where do the Democratic candidates stand on transportation issues?

Although transportation is a critical part of every New Yorker’s daily life, only two of the candidates running in the September 13 Democratic mayoral primary have announced positions on the major issues.

Miller

Council Speaker Gifford Miller centers his transportation agenda on giving first priority to continued restoration of the subway system. In a May 12 speech, the most comprehensive address on transportation issues of any candidate, Miller declared that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s two-decade program to bring the subway system to a state of good repair is “stalling.” Miller charged that the MTA cut the five-year construction budget for the subway and bus system by $5 billion, resulting in delays for “already underfunded items such as communications and signals systems, power stations, ventilation plants and passenger stations.”

Miller called for repairing and modernizing the system before spending money on new subway or commuter rail lines. He says that funding should be funneled to the repair program from expansion projects and new taxes. He would give priority to extension of the #7 line to the West Side and the Second Avenue subway project in preference to the commuter rail project that would send Long Island Rail Road trains to Grand Central Terminal. Miller also called for reinstatement of the commuter tax, once paid by suburban residents who work in the city but repealed in the late 1990s in an Albany political deal. Miller asserts that the mayor should “stop accepting defeat” on a commuter tax and proposed a graduated tax.

Another source of new revenue in Miller’s plan is to obtain full value on the West Side rail yards. Miller opposed the Jets/Olympic stadium plan and now opposes the new MTA plan to build a new headquarters on the site and thus generate funds by selling the MTA’s valuable Midtown office building.

The Council Speaker has also addressed transit security issues in the wake of the London subway bombing, advocated improved rapid bus services, and proposed an expanded ferry system.

In response to a question in the August 16 candidate debate, Miller opposed tolls on the East River bridges.

Weiner

Congressman Anthony Weiner proposes to modernize the city’s transportation system, but in a quite different fashion. Where Miller emphasizes underground transport -- over which the mayor has no direct control -- Weiner emphasizes waterborne and surface transit programs that are subject to City Hall’s direction.

First on Weiner’s plan is building ferry landings throughout New York. Weiner would thus expand ferry service to neighborhoods like Red Hook, Long Island City, Sheepshead Bay, Marine Park, Coney Island, Bayside and the areas around LaGuardia and JFK airports. He believes that ferries, which are currently a small niche transportation provider, can circumvent congestion and spur economic and residential growth in these areas. Toward this end, Weiner, who sits on the House transportation committee, secured $15 million toward ferry service from the Rockaways to Manhattan.

Weiner also emphasizes creating a bus rapid transit system throughout the city, including bus-only lanes on major travel corridors. Weiner thus seems prepared to support plans currently being drawn up by a joint City-MTA task force to establish at least five bus rapid transit corridors in the city.

From his seat in Congress, Weiner also helped obtain $100 million in the new federal transportation bill for a freight tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn. The tunnel is a controversial proposal that lacks the support of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which would be charged with finding financing for the multi-billion proposal and building the tunnel. Mayor Michael Bloomberg at first supported, and then under pressure from Queens community groups opposed the tunnel plan.

Finally, Weiner also jumped on transit security issues after the London bombings. He announced a six-point security plan that includes bomb resistant trash cans, digital station cameras and 911 subway cell phone service.

Ferrer and Fields

Remarkably, a search of news clips and the campaign Web sites of Fernando Ferrer, the former Bronx borough president, and Virginia Fields, the Manhattan borough president, turned up only sparse comments on transportation issues.

Ferrer’s most widely publicized transportation issue has been reversing the expansion of metered Sunday parking instituted in 2003 and recently rolled back by the City Council. Ferrer assailed metered parking, which forced some worshippers to feed the meter in the middle of services, as “a tax on worshipping.” Ferrer has also advocated using the MTA surplus for security cameras and counter-terrorism training.

Fields has not made transportation issues a focus of her campaign. As borough president Fields has supported the Second Avenue subway and lower Manhattan’s new transit hub, and opposed the Jets stadium deal and MTA plans to purchase more diesel buses.

In the August 16 candidate debate, Fields said she is open to the idea of London-style congestion pricing and using the revenue toward improving mass transit. But like all her opponents, she opposed tolling the East River bridges. She also stated her support of a commuter tax, with revenues directed to mass transit.

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Hybrid Vehicles

Evgeny Friedman, with slicked-back hair and Adidas trainers -- talkative in two languages and on two cell phones -- is the no-nonsense co-owner of Taxi Club Management Inc., managing a fleet of 650 cabs that cruise the streets of New York. Talk to him about the City Council’s plans to replace the city’s taxis with hybrid vehicles, and he has a...well...hybrid reaction.

The typical hybrid vehicle combines a gas engine with an electric motor, using the gas engine to charge up the electric motor, and the electric motor to supply supplemental power when needed. The result is about half the gas consumption of a regular vehicle. It also means more headaches for mechanics learning to deal with the added complexity.

"My mechanic has to wear a rubber suit just to avoid electrocution," says Friedman.

Complications aside, however, Friedman is a big fan of staying one step ahead of the technology curve. That is why, when the Taxi and Limousine Commission offered up its first set of hybrid vehicle medallions at auction this spring, Friedman and his partners ponied up an $8 million bid for 18 medallions.

"It's a no-brainer," he says. "Look at gas prices now and look at the Middle East. Within five to six years there's not going to be a regular gas taxi on the road. Every cab you see will be either hybrid or alternative fuel."

And, he says, "with hybrid vehicles, my drivers don't have to put in so many hours, and I don't have so much turnover.”

Friedman is not the only enthusiastic pioneer. Hybrids are a can't-miss both politically and fiscally. Mayor Michael Bloomberg was equally enthusiastic in May when he signed a law requiring a 20 percent boost in city fleet's fuel economy through additional hybrid vehicles.

But they are, by definition, an imperfect solution, especially in a city already earning poor marks for air quality.

No Hybrid Meeting NYC Standard?

In the course of putting the hybrid medallions to use, Friedman and his partners have hit a major bureaucratic pothole. His company received a congratulatory note from the commission after winning the auction and had its initial $486,000 deposit accepted. A few weeks after the deposits, however, the bad news arrived. Citing a 2001 mandate on minimum back seat leg room for authorized cab models, the commission said it could find no hybrid models available yet on the market that met the current standard.

Friedman promptly filed suit in local court to get a resolution on this regulatory Catch 22. He suspects that somebody inside the Taxi and Limousine Commission chafed at the medallions' reduced cost. The usual market price for a New York City taxi medallion is $800,000, meaning Friedman and his colleagues received a 40 percent subsidy at city taxpayers' expense . Given the cabs' experimental status, however, he expects to spend the bulk of that subsidy on maintenance costs: "At the end of the day, I'll probably break even.”

Taxi and Limousine Commissioner Matthew Daus, meanwhile, says the key sticking point isn't cab company buy-in so much as manufacturer buy-in. Taxi cabs, much like police cruisers, undergo a rigorous qualification process, focusing on everything from interior amenities to long-term durability. In the case of the Crown Victoria, currently the most popular model among city cabs, the Ford Motor Company went out of its way to build a special New York City model. So far, no manufacturer has stepped forward to do the same for hybrid vehicles.

"There's no one who's told us yet that they want to focus on this as a market," Daus says. "There's been give and take, but right now, [the manufacturers] have not presented vehicles to us and asked them to put them on the road for testing."

Bill To Push Hybrid Cabs

The New York City Council recently passed legislation to help break the impasse. Three years after authorizing 900 new medallion sales on the condition that nine percent go to hybrid vehicles at a discounted price, the council passed a bill that now makes it possible for all new medallion holders to operate hybrid cabs. Lauded by environmental groups such as the Coalition Advocating for Smart Transportation and the Natural Resources Defense Council, the bill leaves it up to the commission to decide which exact models qualify but puts a 90 day limit on the deliberation process.

Although the bill still awaits the mayor's signature, Daus says the commission is ready to accept the council's challenge. It is currently in talks with Ford and Toyota about taxi versions of the Escape and Highlander SUV models respectively. The Toyota Prius, while currently the most-recognized symbol of hybrid technology to most U.S. consumers, remains "totally unworkable" Daus says because of interior legroom limitations.

"We're excited about the opportunities opening up, but we've had to be proactive just to get to this point," Daus adds. "Usually the manufacturers come to us and say, 'Can this be a cab?' In this case, none of the vehicle models existed until a very recent period."

As for Friedman, he remains in limbo, waiting to see if the medallions he legally purchased at a discount also qualify for the new program. He expects a court to resolve the issue this summer.

"I hate to go up against the TLC, because, to be honest, the TLC has made me a lot of money," he says. "I just want to close this issue and put these vehicles on the road and make TLC part of the solution."

HYBRID BUSES IN HARLEM

Attempts to put hybrid diesel buses on the streets of Manhattan have drawn less attention and, interestingly, less acclaim from local environmental groups. Chalk it up to diesel's dirtier reputation as an air pollution source and a still lingering dispute over bus depots north of Central Park.

The dispute began with a 1998 deal between West Harlem Environmental Action, a group that goes by the acronym WE ACT and the Metropolitan Transit Authority to put more "clean air" buses burning compressed natural gas instead of diesel on Manhattan streets. Backed by Governor George Pataki's office, the deal pegged the Manhattanville bus depot at 133rd St. and Broadway as the most likely site, although left the site open for negotiation.

In the following years representatives of New York City Transit, the MTA agency responsible for public bus and subway transit inside the five boroughs, pressed to make the Mother Clara Hale Depot, a smaller facility located at 146th and Lenox Ave., the main site for compressed natural gas buses, noting the smaller cost of re-conversion.

According to Swati Prakash, environmental health director for West Harlem Environmental Action, the negotiation process began to falter around 2003, the year New York City Transit opened a new depot at 100th Street and closed one of its two remaining depots in Lower Manhattan. When the agency announced a year later that it would be housing hybrid diesel buses instead of compressed natural gas buses at the Mother Clara Hale depot, negotiations broke down completely.

"We were waiting for the agreement to wend its way through the legal department," says Praksash. "Then we read a story in the New York Times saying that the MTA is set to use hybrid-diesel in its buses."

Prakash says hybrid buses are an unsuitable compromise for her group, because Harlem and nearby neighborhoods already boast some of the nation's highest youth asthma rates. According to a 2003 Harlem Hospital study, one in four Harlem children has asthma, more than four times the national rate as determined by the Centers for Disease Control.

Linking those rates directly to diesel is tough, but not impossible. Diesel engines tend to be more efficient than regular fuel and compressed natural gas engines, lowering the number of carbon-based "greenhouse gases" produced as well as overall fuel consumption. At the same time, however, even the cleanest-burning diesel engines generate soot and ozone, two chemical "triggers" of youth asthma according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

"Despite tighter regulation of air pollution, widespread diesel engine use generates microscopic particles that penetrate deep into human lungs and circulation," reads an Academy summary of a recent health journal article. These particles contain chemicals that lead to cell damage.

For New York City Transit, the choice of diesel hybrids over compressed natural gas comes down to cost. In a 2003 study published by the U.S. Department of Energy, New York City Transit noted that hybrid diesel buses require no major capital investments in terms of fuel storage, resulting in a $1,800 incremental cost per new bus vs. an $8,000 incremental cost per compressed natural gas bus.

So far, New York City Transit has already seen delivery on its first major order of 125 hybrid buses and is slated to have at least 325 operating on Manhattan streets by the end of the year. In the meantime, members of WE ACT and their Harlem neighbors have taken their complaints to the MTA board. In May they asked the board to resume talks on a natural gas depot above Central Park but left without a commitment.

Prakash is undaunted. She labels her group's appearance at MTA headquarters a "show of numbers" as her group gears up to remind neighborhood voters of the deal forged back in 1998.

"The MTA already sites six diesel bus depots above 99th Street," she says. "Community residents are not going to let this go."

Â

Security and the NYC Subways

The bombing of three subway stations and a bus in London on July 7 brought into stark relief, once again, the ongoing threat to New York City. New Yorkers have long known that their city -- and its often jam-packed transit system -- is a prime target of terrorists. While the city's residents and visitors may sometimes set aside the risks, one would be hard-pressed to find anyone who is not aware of the possibility of another terrorist attack.

The London bombings also cast the spotlight on the NYC transit system's snail-like progress in spending nearly $600 million to improve security in the subway system. Two and one-half years after announcing the completion of a thorough security review, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) reportedly has spent only $30 million of that sum, mostly on studies and consultants. Boston and Washington have deployed sensors to detect the presence of biochemical agents in the subway system. Houston has closed-circuit television cameras that can be used for surveillance. Atlanta upgraded two-way radios to allow transit workers to communicate with police and rescue workers. Compared with these efforts, New York lags behind.

Reaction to this news was predictable. Senator Charles Schumer called for a "crash program" because terrorists "have chosen mass transit as their target of choice." Mayor Michael Bloomberg called on the MTA to "ratchet up the pace of increasing security on our subway system." Mayoral candidate Anthony Weiner said, "It's not money that's standing in the way, it's bureaucratic foot-dragging that's stopping the MTA from doing it."

According to press reports, the MTA plans include

• strengthening transit facilities against explosives

• restricting access to sensitive areas

• detecting intrusions

• surveillance

• and communications systems.

These are clearly valuable security improvements that will improve the MTA's ability to monitor and respond to possible security threats.

While spotlighting the transit system's vulnerability, reaction to the London bombings also highlighted New Yorkers' sophistication in understanding and responding to the terrorist threat. A simplistic reaction to physical threats would be to seek absolute safety, no matter the cost or consequences. The power of this reaction is seen in the newly fortified design for the Freedom Tower at the World Trade Center site, and NASA's struggles to define acceptable level risk and safety after the two shuttle accidents. Discussions between the MTA and the Army, reported by the Times, aiming to develop motion detectors, infrared sensors and sophisticated software to monitor subway tunnels and other infrastructure also evidence the notion that the system can be "hardened" to repel attack. The comment in a television interview by Michael Chertoff, the Homeland Security chief, that "there is a technological and a system-based solution for this" is another example of this way of thinking.

New Yorkers do not seem to be buying the idea of absolute protection, however. On-street interviews carried in various press reports show a public partially willing to accept, partly trying to deny and partly attempting to rationalize the risk of terrorist attack. Mainly, the public seems to be trying to get on with life, knowing that they can neither avoid nor prevent what officials in London called a "shock" but not a "surprise." As an example, it was notable that in the two days following the London bombings I sat through a series of day-long meetings with city staff and others without anyone even mentioning what happened in London.

Terrorism and transportation experts cite four basic tasks in dealing with the threat. The four are:

• Deterrence, such as police patrols and chemical-sniffing dogs;

• Prevention, such as intelligence to catch terrorists before they strike, "saying something" when you "see something" in the subway and erecting bollards around key buildings to keep truck bombers some distance away;

• Mitigation, such as hardening stations and tunnels to minimize the damage from an explosion; and

• Prompt response to minimize casualties, such as good communications between emergency response personnel and regular drills to sharpen response procedures.

None of these approaches are foolproof, but each has been shown to be effective in reducing the risk.

Experts such as Brian Jenkins of the RAND Corporation (In PDF Format) also emphasize creating a net benefit rather than simply displacing the threat or the threatened. Jenkins says that security measures "should not merely displace the risk toward other equally vulnerable targets" - for example, from train stations to equally crowded shopping malls. Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute (In PDF Format) points out that it would be counterproductive if people stop using mass transit and drive instead, since the risk of a fatal traffic accident far outweighs the risk of dying in a terrorist attack.

In addition to these practical considerations, there are larger dangers to overreacting to the London bombings. As Jenkins has said, "We cannot allow fear to become the framework of American governance." Thus, we will continue, as Susan Jacoby wrote in Newsday, to try and do "a very good job of not thinking about what I know perfectly well - that it is absolutely impossible, in a city the size of New York, to make the subways and buses and public buildings safe from bombings."

Meanwhile, New Yorkers might feel a bit safer, and a bit more in control, if we act on the advice from the ad in the subway, "When you see something, say something."

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Cell Phone Use By Drivers -- A Threat To Public Safety?

In 2001, New York State became the first state to ban the use of hand-held cellular telephones by drivers. Several other states and cities have followed suit, including New Jersey and Washington DC. Chicago banned hand-held cell phone use last month, as did the Connecticut Legislature earlier this month.

Despite their growing popularity, the effectiveness of these laws is open to question. Publicity and enforcement of the New York State ban produced a drop in the proportion of drivers using cell phones from 2.3 percent to 1.1 percent. But a study published in Injury Prevention found that the rate of cell phone use rebounded to 2.1 percent in 2003 after the initial publicity subsided.

That study focused on several small to medium size upstate communities. The rate of cell phone use by drivers in New York City appears not to have been measured. Nationally, however, a 2004 survey by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimated that eight percent of all motorists were using cell phones at any given time while driving, up from four percent in 2000. Casual observation suggests that New York City drivers at least match the national average. With the continued proliferation of cell phones and increasing functionality of the phones, the number of drivers using phone is likely to continue to grow.

Is cell phone use by drivers a threat to public safety? Published studies have been used to argue both sides of this question. A February 2005 University of Utah study found that young people tested in driving simulators were 18 percent slower in hitting their brakes than drivers who did not use cell phones. Cell phone users suffered from “inattention blindness” – while your eyes may be looking at something, you may fail to see it, or you may fail to see it in time to avoid a collision.

A widely-cited 1997 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that the risk of collision when using a cell phone was four times higher than the risk when a cell phone was not being used.

But other studies minimize the actual danger of cell phone use. The University of North Carolina Safety Research office review of State Trooper crash reports (in pdf format) found that cell phones appeared to play a role in only 0.16 percent of crashes. In 2003, Delaware police reviewed 1300 accidents in Delaware and found only four in which motorists were distracted by a cell phone.

Self-reported behavior is notoriously unreliable, however. Accidents are likely to have a number of contributing factors, and what motorist wants to believe that their own actions were key factors?

If government policy is based on the statistical studies of crash risk, then New York State should indeed ban handheld cell phone use by motorists. It should also ban motorists’ hands-free cell phone use, based on University of Utah studies that found that using a hands-free or hand-held phone makes no difference to the level of motorist distraction. About 20 percent of cell phone owners have hands-free devices.

But more than a ban is needed. The history of seat belt laws demonstrates that vigorous public education and enforcement programs are needed to change the public’s behavior. Seat belts have long been proven to be an extremely effective way to reduce injuries from motor vehicle collisions. Yet for years, many people refused to buckle up. But with a extensive educational program and highly publicized enforcement, restraint usage rose dramatically. According to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) surveys seat belt restraint use increased from 58 percent in 1994 to 80 percent in 2004.

Since the Buckle Up New York Campaign was initiated in May 1999, seat belt use in New York State has risen from 74.2 percent of motorists to 88.3 percent in 2001, though the rate slipped to 85 percent in 2004.

Whether a similar educational and enforcement campaign for the cell phone ban prevents enough injuries to be worth the cost needs further investigation. But there seems to be little question that without such a campaign, laws to ban motorists from using cell phones don’t do much good.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â