New Bills: Biking On The Boss's Dollar

At its stated meeting September 25, several council members introduced legislation that makes a business liable when their delivery workers or bike messengers violate traffic regulations. Legislation was also introduced to allow advertising on sheds surrounding scaffolding.

Fining Bicyclists' Bosses

Councilmember Jessica Lappin received a letter from 9-year-old Annabel Azziz of the Upper East Side, saying she worried about bicyclists who violate traffic regulations. "Now we cannot take a simple walk without being nervous of bicycles zooming next to us in the park," Annabel wrote of her strolls with her father in Central Park.

The councilmember decided it was time for someone to pay. Not the bicyclist, Lappin said, but his or her employer.

Lappin introduced legislation (Intro 624) with Councilmember Alan Gerson that shifts the burden of traffic fines from the bicyclist to the bicyclist's employer. The move, Lappin said at a recent press conference on the City Hall steps, will encourage employers to train their messengers and delivery personnel and keep pedestrians safe on the city's sidewalks.

"For children and seniors, getting hit by a bicycle can be life threatening," said Lappin – one of her elderly residents was struck by a bike last month and needed hip replacement surgery. "So the message is simple. Businesses have to be held responsible for their bikers."

Currently, a bicyclist can be fined between $100 and $300 for violating traffic rules, and is also subject to an additional $200 fine if the rider hits a pedestrian. In 2006, Lappin said, the New York City Police Department issued approximately 40,000 traffic violations to cyclists. Because bicyclists are required to wear a logo or sign with their place of employment, the violation's transfer will be smooth, she added.

Restaurants and companies will likely comply with the legislation, Lappin added, because she hopes to publicize habitual offenders.

Transportation Alternatives, a nonprofit advocacy group, supports the legislation. "(Employers) should be responsible in seeing that their workers follow these laws and culpable if they do not," the group said in a prepared statement.

Advertising on Scaffolding

Despite efforts by arts associations, the buildings department and Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer to eradicate illegal advertisements on the city's scaffolding, Councilmember Melinda Katz would like to see advertising on sidewalk sheds - the structures that enclose portions of scaffolding.

According to legislation (Intro 623) introduced last month, the commissioner of the Department of Buildings would set a price to lease space to businesses looking to place their ads. The sidewalk shed advertisements would only be permitted in commercial or manufacturing zones and could not abut a building or property located in a historic district or that is designated a landmark site.

Katz, who is a candidate in the 2009 race for city comptroller, said the advertising could boost city revenue. The legislation's critics contend the advertising can be an eyesore, and the removal of scaffolding could be stalled so the owner of the property could continue making a profit.

Retaining Walls

Councilmember Michael McMahon also introduced (Intro 625) legislation that requires the construction of retaining walls be scrutinized more thoroughly.

Currently, retaining walls are included in the Department of Buildings professional certification program, which allows plans submitted by a certified architect or engineer to go through the approval process more swiftly. In this program, the certified professional ensures the plans comply with all applicable city codes, and thus is not subject the same intense examination.

According to the legislation, retaining walls greater than 3 feet would no longer be included in the program, and thus construction would be subject to more scrutiny no matter who submits the plan.

Â

State of Cycling

Even in packed subways, high gasoline costs and concerns about health, less than 1 percent of all New Yorkers regularly use their bicycles to commute to work. At the same time,18 percent of all New York City adults still smoke cigarettes.

Over the past five years, the Bloomberg administration has made a massive and somewhat successful effort to reduce the number of smokers. Now, can the same government that persuaded New Yorkers to stop smoking create an environment that will convince them to start cycling?

More than ten years ago, the Giuliani administration formally introduced the Bicycle Master Plan for New York City, an initiative to develop a city-wide bicycle network to increase ridership and integrate cycling into the city's transportation system. Since then, the plans have evolved. This spring, cycling has emerged as part of PlaNYC 2030, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's ambitious proposal to make New York City more environmentally friendly and reduce carbon emissions believed to cause global warming. The current plan calls for the completion of an 1,800-mile system of bike routes by 2030, as well as improvements to biking facilities and increasing public awareness. But New York still lags behind many other cities when it comes to promoting bicycling, and a number of questions remain about safety, facilities and the fight for always scarce space in the crowded city.

Building The Network

Since Bloomberg announced PlaNYC in April, the city has already begun work on trying to increase bicycling. Some advocates viewed earlier city efforts as sluggish. The city's previous transportation commissioner, Iris Weinshall, was criticized for being uninterested in cycling, and the department's bicycle program director resigned last summer. But advocates have praised Weinshall's successor, Janette Sadik-Khan, who was named commissioner in April, for her commitment to alternative transportation and environmental sustainability.

The administration is already trying to reach the cycling program’s first benchmark -- adding 200 miles of bike lanes by 2009. Overall, PlaNYC calls for:

• 500 miles of separated bike paths

• About 1,300 of miles of striped or marked bicycle lanes

• Additional greenways, or car-free paths that connect the city’s parks.

• Improving public education on cycling and safety issues and observation of traffic laws

• Installing 1,200 additional bike racks by 2009

The city’s move toward a complete bicycle network has not been without debate. A proposed bicycle lane on a car-free block of East 91st Street has drawn opposition from members of the local community who want to preserve the tranquility and safety of the street. The Upper East Side residents of Community Board 8 are also frustrated that city officials did not consult them before deciding on the lanes, according to David Liston, the board's chairman. "On something so serious, so important, and recognizing how important bike lanes are for the city, I don't know why they did not come to us sooner," he said. The community supports the city's efforts to install new lanes and encourage cycling, according to Liston, but he added, East 91st was "simply the worst location" for a bike path.

According to the New York Sun, residents of the Upper East Side have enlisted their elected officials all the way up to their congresswoman. The transportation department is considering an alternate route.

A plan to have bike lanes along Ninth Street in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn encountered opposition from residents hostile to bicyclists and from those who said the lanes would make it more difficult for them to double park in front of their homes to drop someone off. The city approved the lanes anyway.

Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, said the community tension over facilities for bicycling stems from New York’s longstanding focus on cars at the expense of cyclists and pedestrians. “Our city for the past six or seven decades has been designed around cars, which is the most inefficient use of city space to move people around,” he said. “What we’re left with is that bikers and walkers are fighting over the scraps.”_

Bike Sharing

Many New Yorkers cannot take advantage of the city’s lanes and paths because they either do not have a bike – it can be hard to store them in tiny apartments—or find it difficult to transport their bikes around the city. To address that issue, some cities around the world have implemented bike sharing. Advocates want New York to follow their lead.

" I think a look to a city like Paris would really be instructive," said David Haskell, founder of the New York Bike Share Project, referring to the French capital's recent launch of its own bike-share program. Paris currently provides more than 10,000 bikes that can be picked up, ridden and dropped off at another station in the city. Renters swipe a pre-paid subscription card and pay for any time beyond the first 30 minutes. And the city plans to install 10,000 more bikes within a year.

The Paris initiative, the largest in the world, is one of several around Europe that Haskell looks to when envisioning one for New York City. Last month he organized a five-day project in which riders could rent a bike for a free 30 minutes in SoHo and drop it off at another location. The program drew hundreds of people eager to try it out.

Since then, support has continued through e-mails and calls to his office, he said, and he hopes to launch an expanded follow-up project next spring. That program will be temporary, but Haskell called it “a way to keep the public interested,” while the city ultimately considers a permanent system.

Advocates are excited about the idea, and city officials considering whether it could work here. A bike-share program would require hundreds of stations at which to pick up and return the rented cycles. The department would not speculate on what else those stations might include. “Finding the space for all those stations is really something that’s under consideration,” said Joshua Benson, the Department of Transportation's bicycling program coordinator.

A Cycling Infrastructure

A system of shared bikes, though, is just one element in creating an entire infrastructure for cycling in New York. “We’re just seeing what’s out there in other cities,” Benson said. He said a “complete bike network" would include increased bicycle lanes, as well as bike parking and storage.

Budnick of Transportation Alternatives also emphasized the need for bicycle parking and storage -- the lack of safe storage is the number one reason why people in the city don’t take their bikes to work, according to 1999 report by the Department of City Planning. To that end, the transportation department under PlaNYC is continuing its CITYRACKS program -- in which the department builds racks based on requests from throughout the city -- and aims to put up 1,200 more racks in the next two years. The plan also calls for a law that would require commercial buildings to provide bicycle storage.

Budnick of Transportation Alternatives also emphasized the need for bicycle parking and storage -- the lack of safe storage is the number one reason why people in the city don’t take their bikes to work, according to 1999 report by the Department of City Planning. To that end, the transportation department under PlaNYC is continuing its CITYRACKS program -- in which the department builds racks based on requests from throughout the city -- and aims to put up 1,200 more racks in the next two years. The plan also calls for a law that would require commercial buildings to provide bicycle storage.

Safety

One challenge to increasing bicycle rider ship in the city is making it safer. A 2006 city study found that from 1996 to 2005, 225 cyclists died in crashes, 92 percent of them in accidents involving cars. Also, several high profile deaths in the past year, two from car crashes on a popular Hudson River bike path, have further highlighted the need to protect cyclists. One motorist, who killed a cyclist, drove along the bike lane, apparently not realizing it was not intended for motor traffic. Flexible plastic pylons are all that separate the Hudson River from motor traffic, prompting transportation officials to consider a switch to bollards, or steel posts or other barriers that are cemented to the ground.

A study released by Transportation Alternatives earlier this month found that 52 percent of cyclists surveyed felt “very safe” or “safe” in buffered lanes, in which there is an additional five-foot-wide painted space between the bike lane and auto traffic. Meanwhile, the study found, only 21 percent felt secure in conventional bike lanes, which offer no barriers between cyclists and drivers.

The study concluded that the city should come up with “more innovative ways” to protect bicyclists from car traffic as it adds bike lanes to major routes. “I think the next step in making the city’s bike network stronger is the city putting in actual protected bike lanes on the street,” Budnick said. He suggested that bollards be used to physically separate bike lanes from motor traffic.

The transportation department has recently begun to paint some bicycle lanes throughout the city bright green in order to make them more visible to car and truck drivers. Although many residents find the color ugly, the city plans to paint about five miles of these lanes in areas where drivers are more likely to clash with cyclists.

The city’s other current safety efforts include a free helmet giveaway and a recent law to protect bicycle delivery workers. Benson, the city’s bicycle program coordinator, also said an ad campaign would be launched in September that would “highlight the rights and responsibilities of motorists and cyclists.”

Haskell said the city deserves a lot of credit for its work with bicycles in the last two years. “There’s definitely been a shift in the understanding of how bikes can conquer the larger transportation challenges in the city,” he said. But, Haskell added, the administration still has work to do. “I would still urge the city to be a bit more bold with their thinking and a bit more visionary in terms of the scale of what might be done,” he said.Â

A Divided Council Confronts Congestion Pricing

In the touch and go, back and forth, here and there negotiations over Mayor Michael Bloomberg's congestion pricing plan, a new player got caught up in the controversy: the City Council.

If the mayor receives enough federal funding to move his plan forward and if it then receives the blessing of a 17-member commission, 51 council members will have to decide where they stand on charging cars $8 and trucks $21 to drive into or out of Manhattan below 86th Street during the workday.

Most council members are not yet ready to make that decision. But over the next several months, they could face a divisive issue, featuring the kind of democratic and sharp debate not really seen in council since the 2005 controversy over the city's waste management plan.

The Breakdown

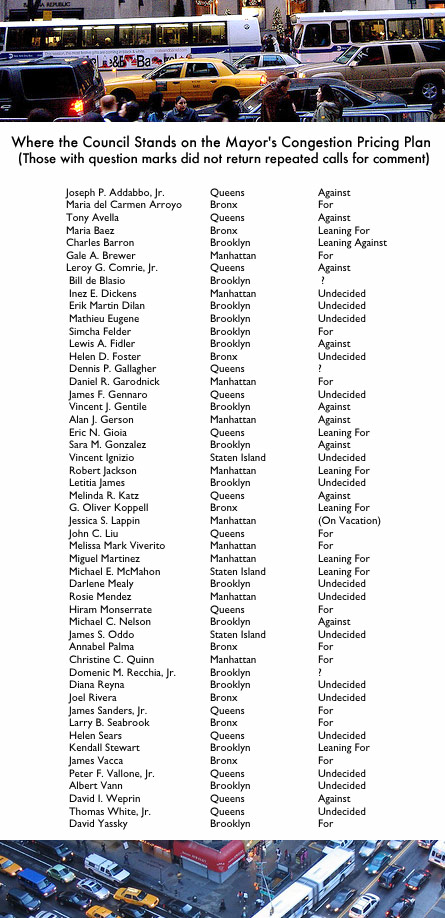

Of the 47 City Council members who responded to Gotham Gazette’s query, only 23 council members took definite positions on the mayor's proposal. The others are leaning one way or the other or say they are undecided.

Twenty council members support or lean toward the plan. Another 11 oppose it or lean against it. Nearly a third of the council, or 16 members, contacted by Gotham Gazette said they were undecided, and three others did not return repeated phone calls. Jessica Lappin was on vacation and so unavailable.

For the plan to pass, 26 council members would have to approve it. With City Council Speaker Christine Quinn supporting the fees, Bloomberg may be able to move some members over to his side.

The next step for congestion pricing could come as early as this week when the federal government tells the city whether it will receive up to $500 million to purchase equipment to implement congestion pricing and for mass transit improvements, including buses. The plan must then receive a favorable review from a 17-member commission charged with coming up with a plan to reduce the city’s notorious traffic jams, according to the bill approved by the state legislature late last month. If all that happens, then it will be the council’s turn to weigh in. If they approve congestion pricing, the final say will rest with the legislature and the governor.

Who Stands Where on Congestion Pricing

Surprisingly, where the council members’ districts are seem to have little effect on their position. One could assume those from the outer boroughs would be the most likely to oppose the idea. But some of congestion pricing's most outspoken supporters, like Councilmember John Liu, hail from Queens, while others who have expressed doubts, like Councilmember Alan Gerson of lower Manhattan, are from districts that supposedly would reap the most benefits from it.

Many of the council members listed as for or leaning for said their continued support hinged on the city making improvements in mass transit. Bloomberg has promised to do that, using first the federal funds and then the revenues from congestion pricing.

Council Gets Its Say

Congestion pricing has the potential to be that rare thing in City Hall – a divisive issue that could split alliances. As he has repeatedly done, the mayor initially wanted to exclude the City Council from having any role in congestion pricing. But during negotiations over the plan in Albany, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver reportedly insisted that the compromise creating the commission require the council's approval before the legislature could vote on any plan to relieve congestion.

"I've been insisting that the council has an absolute right to weigh in on this," said Councilmember Lewis Fidler – a congestion-pricing foe who introduced a resolution several months ago against the proposal. "Institutionally it's very important for the council that that be done. This is the issue of whether or not tolls are going to be imposed on the streets of New York," not Albany, he added. "I for one feel relieved."

Although the deadline for council to approve or reject the plan put forth by the commission is not until March 31, 2008, Council Speaker Christine Quinn is already gearing up to reach a consensus. Quinn, who will appoint three representatives for the 17-member commission, supports congestion pricing, albeit with conditions.

In a memo sent to council members last week, the speaker stated she would schedule individual meetings with every member to review their complaints, concerns and apprehensions regarding congestion pricing.

The memo states: "While I support congestion pricing, I am keenly aware that many of you have expressed concern about congestion pricing and will have questions about the agreement. I understand that a plan of this magnitude, whether congestion pricing or another method, will profoundly and uniquely affect each of your districts. I am committed to working with each and every one of you to hear and address those issues."

Their Reasons For Support

Council members, like other New Yorkers, recognize traffic is more than an inconvenience here – it creates health problems and affects the city economy. According to the mayor's proposal, congestion costs the city $13 billion in lost business revenue, lost time and increased vehicle costs. With congestion pricing, the report contends, 94,000 commuters would shift from driving to mass transit. A transition of that magnitude would consequently reduce the emissions that cause global warming and better the city's environment.

Council members, like other New Yorkers, recognize traffic is more than an inconvenience here – it creates health problems and affects the city economy. According to the mayor's proposal, congestion costs the city $13 billion in lost business revenue, lost time and increased vehicle costs. With congestion pricing, the report contends, 94,000 commuters would shift from driving to mass transit. A transition of that magnitude would consequently reduce the emissions that cause global warming and better the city's environment.

"Besides alleviating a lot of the pollution that goes into our environment from so many people that drive into work, it will help us improve our transportation system," said Councilmember Annabel Palma, a supporter of the mayor's plan dependent upon certain transportation improvements in her Bronx district. "And again it always helps to be able to put together a plan that will keep people healthier for longer periods of time."

While some council members said congestion pricing unfairly burdens those outside of Manhattan, others see the plan as righting a longstanding inequality from borough to borough. "I lean toward it from the fact it spreads out the burden Staten Islanders have borne," said Councilmember Michael McMahon, referring to the tolls his constituents pay. Under the plan, the tolls will count toward the $8 congestion fee.

Their Reasons For Concerns

Most council members' who oppose or lean against congestion pricing say they worry that the tolls will be implemented without the transportation improvements promised in Bloomberg's PlaNYC 2030 environmental proposal. These include five bus rapid transit routes in each borough, allowing buses to travel in special designated lanes, and increased capacity on the city's most traveled subway lines. Even those who have endorsed the mayor's pricing proposal, like council members Simcha Felder, Palma and Quinn, have said their support depends on these other promised improvements.

"I don’t believe we've exhausted every alternative before charging residents to drive into the city," said Queens Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, an outspoken critic of congestion pricing. "We could enforce cars (to stay out of) bus lanes. We could enforce other traffic rules. We could look at delivery hours."

A short list of other complaints include:

--fears that outer-borough neighborhoods would become parking lots for commuters wanting to leave their cars outside the congestion zone;

--concerns that congestion will increase outside the zone. This would raise emissions in some neighborhoods and increase health problems, like asthma, there;

--a belief that the $8 toll equates to a regressive, commuter tax that is unfair to the poor.

"I think the plan is myopic and shortsighted and does not show the real depth and purpose in creating the types of resolutions that would benefit the entire city of New York," said Councilmember Leroy Comrie.

The Undecided

The many council members who have not made up their minds raise an array of issues including whether commuters will use parking places, crowding out neighborhood residents, and what effect hundreds of cameras photographing drivers going into, within or out of the zone could have on the privacy and security of New Yorkers.

"What about above 86th Street?" asked Councilmember Thomas White of Queens. "What about the other boroughs? On face value, I'm not satisfied."

Other members representing districts outside the zone, like Maria Baez and James Sanders, worry about plan's effect on the poor. Both suggested incorporating a tax rebate for those charged by congestion pricing.

The undecided are united on one thing: Their main concern remains getting their constituents to their destinations in the fastest, easiest and cheapest way possible.

"What I fear is mass transit won't be prepared for it," said Councilmember Joel Rivera, who also questions the impact of a looming fare increase by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Rivera, though, is still open to the concept. "As a person that drives into the city… it gets congested."

Some are simply holding off on pledging support or opposition because the final details have not been determined. "The proof is in the pudding, and the pudding isn't even in the oven," said Councilmember Robert Jackson.

In fact, the council might never get to vote on congestion pricing. The commission, comprised of members appointed by the mayor, City Council speaker, governor, State Senate majority leader, Assembly speaker and minority leaders of both houses, would meet over the next several months. The plan it recommends does not have to resemble the mayor's. Its only criteria would be to reduce congestion by as much as Bloomberg's proposal – 6.3 percent.

Whatever comes out of this, many officials expressed optimism that in several years New York City will be healthier, greener and less congested. "It's going to be definitely different," said Councilmember Gale Brewer, a pricing supporter, discussing the so-called inevitable revisions to Bloomberg's plan. "If there is real mass transit plans, if we really have a discussion about high quality mass transit that happens with the $500 million, then I think people would be interested."

Â

Compromising on Congestion and Campaign Cash

Just a few days ago, the world as viewed from the State Capitol and City Hall, looked far different than it does today. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver played his spoiler role as Mayor Michael Bloomberg, fresh from Sun Valley, Idaho, desperately tried to convince legislators to approve his plan to charge vehicles to enter or driver around Manhattan. Governor Eliot Spitzer smiled coldly from the cover of New York Magazine defending the anger that has become his hallmark - including his increasingly tawdry battle with Senator Majority Leader Joe Bruno. For his part, Bruno expressed little use for the Assembly or Spitzer

Just a few days ago, the world as viewed from the State Capitol and City Hall, looked far different than it does today. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver played his spoiler role as Mayor Michael Bloomberg, fresh from Sun Valley, Idaho, desperately tried to convince legislators to approve his plan to charge vehicles to enter or driver around Manhattan. Governor Eliot Spitzer smiled coldly from the cover of New York Magazine defending the anger that has become his hallmark - including his increasingly tawdry battle with Senator Majority Leader Joe Bruno. For his part, Bruno expressed little use for the Assembly or Spitzer

Just another day in New York politics.

But following three days of plot turns that delighted bloggers up and down the Hudson, by Thursday evening everything had changed. The four men - individually -- announced deals on congestion pricing and campaign financing. A commission would try to hash out a plan to fight traffic congestion, and new limits would go into effect on contributions to candidates.

Still at the close of business last week, much remained murky, including when the legislature and governor would approve the deal, details of the agreements and the status of other outstanding issues, including legislative pay hikes, a key part of New York City's solid waste plan, expansion of the state's DNA database and more.

FOUR DAYS IN JULY

When legislators went home at the end of June, a number of issues remained unresolved. One, campaign finance reform, was a top priority of Spitzer's but Bruno stood in the way. Meanwhile, Bloomberg, with Bruno as an ally, was pressing his congestion pricing proposal. According to the mayor, the state needed to approve the plan by July 16 - last Monday - in order for the city to qualify for an estimated $500 million in federal transportation funds. But many members of the legislature objected to the driving fees and Silver seemed intent upon stymieing the plan. At the same time, Spitzer was blocking a pay hike for legislators, an increase in turn tied to raises for the state's judges.

Bloomberg wanted the legislature to go back into session on July 16 and hammer out its differences in time for the city to get the transportation aid from Washington. But the putative deadline for the federal funds came and went with no deal.

An irate Bloomberg fumed at Albany's inaction. For their part, the denizens of the capitol said that, unable or unwilling to deal with politics, the mayor had hurt his own cause. "When it came time to deal with people he didn't control, he didn't know how to do it," Assemblymember Richard Brodsky of Westchester, a key opponent of the congestion pricing plan, told the Times.

But talks continued. Finally on Thursday afternoon, Spitzer announced agreement on congestion pricing and campaign finance, along with two issues of less concern to New York City: a capital spending measure targeted largely at upstate and property tax relief for seniors. To the surprise of some, he did not mention salaries.

Four men in a room -- Spitzer, Silver, Bruno and, this time around, Bloomberg or more accurately, his representative Kevin Sheekey - had sat behind closed doors and hammered out a deal pundits called "The Big Ugly." In the horse-trading of politics, seemingly disparate issues became inextricably linked.

"Were this still a stand-alone issue, it would be dead right now," said Walter McCaffrey of Keep NYC Congestion Tax Free, an anti tax group, referring to the fee. "If anyone thinks this is not moving because of pay raises they are naive in the extreme."

At weeks' close, there was apparently no written official document detailing the agreements on congestion pricing or campaign finance reform. The leadership has not yet announced when members would assemble in Albany to vote on the deals hashed out secretly. Experienced observers expect announcements on other matters, particularly salaries, will be forthcoming but can't say what they will concern and when they will be announced.

With so much confusion, any or all of the agreements could still collapse. Capitol Confidential asked, "Will the deal hold long enough for lawmakers to come back? Will Bloomberg really get his traffic plan? And will New York find happiness in campaign finance reform?"

Stay tuned.

That said, here's the apparent status of the big issues at posting time.

CONGESTION PRICING

|

"We live in Staten Island, and we pay a lot of tolls. I know it works in other countries, but we seem to have so many more people. It would certainly be nice to get $500 million though." |

|

"I don't know much about it but it doesn't sound like a bad idea." |

|

"People should be allowed to drive into the city and I don't think they should be charging people more than what they already pay, especially since most people already can't afford to live in the city." |

|

"There are probably alternatives that can be resorted to before we do that, a last resort. I don't think we've tapped everything we need to tap. I know there are other cities that don't allow trucks and deliveries during certain hours, they make deliveries happen during the middle of the night. I frequently see congestion here because of trucks blocking the street." |

|

"You know, we're not on the highway, we're in the city. You're gonna charge people, what, $4.50? That's ridiculous. $8.00? No, he lost his mind. He could fix that manhole cover, that's 100 years old that blew up. That would be a good thing." |

|

"As someone who takes mass transit to work, I see first hand how badly the subway system could use the extra funds that congestion pricing would provide. As a cyclist, I'd be thrilled to see more cars taken off the road. And as someone who has a car, I think anyone who drives into the city during rush hour should be charged $8 for tying up traffic." |

|

"It's a necessary evil. Traffic is getting noticeably worse even within the 18 months I've owned a car. And it helps the environment, so why not? But I probably wouldn't drive into city if it gets implemented. I can't afford $8 a day." |

Last April, unveiling his PlaNYC 2030 for a more environmentally sustainable New York, Bloomberg proposed charging a fee for cars and truck entering or driving around much of Manhattan during peak hours. Known as congestion pricing and modeled on a program in effect in London since 2003, the plan was designed to reduce traffic and the pollution and congestion from it, generate fees to fund improvements in mass transit and qualify the city for a half a billion dollars in federal transportation aid.

Congestion pricing, and much of PlaNYC, won enthusiastic backing from an array of environmental, labor and business groups. But it also encountered staunch opposition from some politicians from Brooklyn and Queens and a number of state legislators. Given that the measure required approval from the state government that seemed likely to prove fatal.

The Deal

Faced with a shattering defeat that could have affected many parts of PlaNYC, Bloomberg late last week - three days after the deadline he had described as inviolate -- accepted the kind of deal he had once dismissed. Similar to a proposal previously made by Silver, the agreement sets up a commission to recommend a plan to reduce traffic congestion in New York City. Although a written proposal has not been released, Streetsblog and other sources report that it would:

--Establish a 17-member commission with three members each appointed by the mayor, the governor, the City Council speaker, the Senate majority leader and the Assembly speaker. The Senate minority leader and the Assembly minority leader would each get one appointee.

--After holding hearings and reviewing information, the commission will submit a plan to reduce traffic to the legislature, governor, mayor and City Council by January 31, 2008.

--The plan must be expected to reduce traffic by at least 6.3 percent.

--The City Council must first approve the plan. It would then require approval by the legislature and governor.

--All of this is contingent on the U.S. Department of Transportation providing at least $200 million.

Despite the many steps the city must go through before it can implement congestion pricing, Bloomberg remained impatient. "We will begin immediately to prepare for the installation of needed equipment to make our traffic plan a reality," he said.

Silver tried to put on the brakes. The mayor, the Assembly speaker told a press conference, is "prohibited from collecting a fee... He can put cameras on every street corner, but he can't use them to collect a fee."

Silver's cautions aside, advocacy groups had a generally upbeat reaction to last week's actions in Albany.

"Today is a watershed day for the health and the future of New York City," said a statement from Michael O'Loughlin, director of Campaign for New York's Future. In her official reaction, Marcia Bystryn, executive director of the New York League of Conservation Voters said, "We can all breathe a little bit easier today - and every day in the future - thanks to the leadership of Mayor Bloomberg, Assembly Speaker Silver, Majority Leader Bruno and Governor Spitzer."

While advocates recognize much work needs to be done, "six months ago no one would have said we would have gotten this far. We've made enormous strides," said Neysa Pranger, campaign coordinator of the Straphangers Campaign in an interview.

"Elected officials - the four men in that room - came to agreement that something needed to be done about traffic and air pollution and transit funding," said Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives. "A course has been set for action. It has gone beyond talk."

The Looming Fight

The compromise changes the political equation by bringing the City Council into the picture - something Bloomberg had sought to avoid. While City Council Speaker Christine has endorsed the plan, her members seem largely divided. One count compiled by the Daily Politics lists 11 members other than Quinn as essentially in favor and nine as opposed or having major reservations. That leaves 30 members whose position is not known.

""I'm surprised that more council members aren't talking," said Queens Councilmember Tony Avella, who opposes the fees. "Even though it's the state legislature that will ultimately make the decision, the council should play a role."

Councilmember David Weprin who has opposed congestion pricing from day one, said he thinks most of his colleague agree with him.

But despite apparent opposition, City Councilmember John Liu, head of the transportation committee and a supporter, thinks many members will come around. Getting improvements in mass transit - particularly better express bus service for more distant parts of the outer boroughs - could go a long way toward persuading skeptical council members, he said. Now, Liu said, many New Yorkers have to "hop on a local bus for a half hour to get to the subways and then if they can even squeeze themselves in" have a 90-minute trip to work in Manhattan. If those riders could instead take a good, reliable express bus to their jobs, councilmembers, Liu thinks, would feel more comfortable "imposing that charge on people who still insist upon driving their own cars."

And even if the council can be won over, the legislature remains a barrier - and maybe not just the openly obstreperous Assembly. On Monday night, "congestion pricing could not muster enough votes in the Republican Senate. No one should forget that," McCaffrey said, adding that even some Senate Republicans, the groups thought to be most supportive of the idea, opposed it.

The Final Answer

So, what could emerge?

Supporters of congestion pricing think their plan will triumph.

Liu, in fact, thinks it may be all but inevitable. "I don't know how long we can stave it off in New York City," he said.

While congestion pricing has proved successful in London, many of the alternatives - restricting access to the city on certain days, for example - have not worked as well, according to Pranger.

And she thinks the logic of congestion pricing remain inescapable: It offers, she said, " the benefit of assisting those who can afford to get around the least which far outweigh charging drivers who are by and large wealthier."

But Hope Cohen, deputy director of the Center for Rethinking Development at the Manhattan Institute says alternate ideas could win more support and still meet federal guidelines for getting the transportation aid. Those requirements including some "tolling component" - not necessarily a congestion fee -- and using technology. (Cohen notes that under the federal rules, any plan must also promote telecommuting as a means to reduce car trips.) One possibility, which Cohen termed "the most American thing out there," would set aside special high occupancy vehicle lanes and charge people to use them.

The next several months will provide "the opportunity for this to be looked at in a more thorough fashion," said McCaffrey. He hopes that discussion will give rise to alternate solutions, such as stricter laws barring cars from "blocking the box" and removing tens of thousands of permit that allow city employees to park for free.

Whatever emerges, Pranger said, "After a three-month gap, people are finally talking about the details and what will work. That's a useful and good sign."

CAMPAIGN FINANCE

As much as Bloomberg wanted congestion pricing, Spitzer wanted campaign finance reform. He had been vowing to clean up Albany since before he became governor and campaign finance reform was an integral part of that drive.

Certainly many would argue that change was long overdue. It has been more than three decades since New York revised its campaign finance laws. The neighboring states of New Jersey and Connecticut have introduced some aspects of publicly financed campaigns and pay to play regulations. New York City far surpassed the state on campaign finance regulations years ago and instituted even more restrictions earlier this month. But the state lagged behind, setting few constraints on who could donate to political campaigns or how much they could contribute.

The accord last week came after a period of intense acrimony - including profanity-laced tirades and accusations of spying - between Spitzer and his campaign finance nemesis Bruno. The agreement delighted some good government groups, but they cautioned, the proposed changes are just a start. The changes do not go into effect until 2009 - the year after what could be a bloody - and expensive fight - between Democrats and Republicans for control of the State Senate.

Unwritten Legislation

Without a bill, it is difficult to analyze what the legislation, if and when it's passed and signed, would or would not allow. But in announcing the agreement on Thursday, the governor's office did reveal some details:

- Individuals will be limited to contributing $25,000 to a candidate for statewide office, down from the current ceiling of more than $50,000.

- For State Senate candidates, the contribution limits would be $11,500, down from $15,500.

- Maximum donation to an Assembly candidate would drop to $4,600 from $7,600.

These limits are far more lenient than those for federal or New York City elections. For example, the maximum amount an individual can give to a candidate for mayor is $4,950.

In addition, the new campaign finance system would:

-- Close the corporate subsidy loophole. Under current state finance laws, corporations can give only $5,000 annually to a campaign. But corporate subsidies are treated as separate entities, with each one able to contribute $5,000. Under the agreement, a corporation and its subsidiaries would be treated as one unit, allowed to contribute a total of $5,000.

--Bar contributions from lobbyists

--Prohibit contributions from so-called limited liability companies that were recently created or have few, if any, assets. This is aimed at special interests groups, which create dozens of pseudo-partnerships to avoid complying with limits on campaign contribution.

--Phase in caps on contributions to political parties' "housekeeping" accounts. These accounts are supposed to cover the parties' organizational activities but are often actually used to finance campaigns. A $300,000 annual cap would take effect in 2009, decreasing to $150,000 in 2013.

--Require individuals to list their occupation and employer when they make campaign contributions. Contributors would also have to disclose who, if anyone, is bundling, or collecting, money from multiple donors for one campaign.

A First Step?

The agreement does not include public financing of campaigns, and many other aspects of it remain vague. Reviewing this, good government groups and advocates said the new rules represent a step in the right direction, but do not go nearly far enough.

"The contributions were dramatically lowered, but by any point of comparison they are still dramatically high," said Suzanne Novak, the deputy director of the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law. "I think everybody including Governor Spitzer agrees that this is only a first step... There a nine million things in New York that needs to be corrected."

Some reforms initially on Spitzer's agenda appear to have been lost. One, said Novak, would have prohibited the "personal use" of campaign contributions. Currently use of these funds is largely unrestricted, letting legislators and candidates use their campaign funds on everything from flowers to lavish dinners at swanky restaurants. But putting control on this is anathema to some legislators in Albany, said those involved in the negotiations.

The compromise also sidesteps further limits on contributions from political action committees. New York has the highest cap in the nation for contributions from these committees in a governor's race -- more than $50,000 per election cycle, according to the Brennan Center.

Overall, advocates see the agreement as weaker than what the governor initially wanted. "The proposal that started off from the governor was a strong proposal, because it addressed each of the areas that need improvement in the state campaign finance laws," said Russ Haven of the New York Public Interest Research Group. "In the beginning they were very significant, but they weren't radical overhauls. In the natural progress, there were some areas that either fell off the table or got weakened."

Some political professionals do not expect the reforms to change much. "It's going to mean that fundraisers are going to have to be more inventive to get big bucks, but they will," said Norman Adler, president of lobbying firm Bolton-St. Johns. "It's like water in a basement. No matter what you do it always creeps in."

For their part, good government forces hope to see a second phase of campaign finance reform that would include the public financing of campaigns. But considering state leaders have not even approved this first phase - and Spitzer has expressed readiness to move onto other issues - a second part could be unlikely anytime soon.

AWAITING ACTION

The legislators left a number of other issues unresolved when they ended their regular legislative session. These are some pieces of unfinished business of particular interest to the city:

Gansevoort Recycling Station: Bloomberg's solid waste plan for the city calls for construction of a recycling station on Gansevoort peninsula in the Hudson River. Because the land is in Hudson River Park, the city needs state approval to build the station there. The Senate has said yes, but the issue stalled in the Assembly, where several Manhattan members have moved to block construction. The station, city officials said, is vital to its overall waste management plan.

Tax Credits for Housing: The legislature has approved a version of 421a, a city program that provides tax breaks to housing developers in an effort to encourage construction of affordable housing. The mayor and City Council had proposed their own version late last year. But the version approved by the legislature - and apparently authored by Assemblymember Vito Lopez of Brooklyn -- included a huge tax break for Bruce Ratner's controversial Atlantic Yards project. And according to the city housing agency, the legislature's bill places additional conditions on developers that would hamper the city's effort to promote building of middle class housing. Bloomberg and Quinn have both urged Spitzer to veto it.

DNA Data Bank: Spitzer would like to expand the collection of DNA to individuals found guilty of felonies or misdemeanors, in state prison or on parole or probation. The measure has been stalled in past years in the Assembly.

Wicks Law: The legislature planned to overhaul the Wicks Law -which requires multiple construction contracts for projects over $50,000. The law allegedly increases construction costs by 20 percent. A measure has passed the Assembly, but not the Senate.

Brownfields: Spitzer introduced legislation in early June to overhaul how the state would distribute tax credits to businesses and nonprofits that clean up, restore and development contaminated brownfield sites. The legislation stalled amid disputes between Spitzer and Bruno.

Â

Tracking and Video: Coming Soon to a Taxi Near You

In a matter of months, New Yorkers riding in taxicabs will have more to look at than the view. The constant media buzz of modern life – television programs, sports scores, advertisements – will invade the back of cabs starting in October, the result of a new city regulation requiring that all yellow cabs be equipped with global positioning systems and video screens.

The city Taxi and Limousine Commission says it simply wants to make cab rides safer and more enjoyable for passengers. But the drivers of the city’s 13,000 yellow cabs have protested, arguing that the new technology will cost them money and impinge on their privacy.

WHAT THE SYSTEM WILL DO

Through the GPS system, taxi passengers will be able to know where they are at any moment. For New Yorkers who never want to be out of touch, the monitors and tracking system will make a cab ride -- 13 minutes on average -- more enjoyable. Passengers will be able to follow sports scores, get up-to-the-minute news, weather and more. (Those who want some peace and quiet will be able to turn off the monitors.) The driver will also notified of traffic congestion in the area and of large parties or concerts that are ending – and could be fertile ground for finding fare-paying customers. With the new system, passengers can pay their fares using credit or debit cards.

Taxi and limousine commissioner Matthew Daus has called the tracking and the monitors “nothing short of revolutionary and evolutionary for the taxi industry" and has written that the technology “will benefit both drivers and customers.” The commission believes it will make it easier for tourists, who may not want to carry much cash, to use cabs. And the system believes such high-tech taxis will enhance New York’s image as the "city of the world.”

But cab drivers are not convinced. They worry that the tracking system will enable the police department and traffic agents to follow the cabs and prosecute drivers for violating traffic laws. “For myself, I am not against it, but I can see my fellow drivers being angry for being dictated to sacrifice for other people's extra entertainment," said one driver, Ibrahim Jane.

Some cab drivers question whether it is proper for the city to require private business owners to install a system that would monitor their activities. “We are not paid by the cab companies or the city. We rent these vehicles for over $100 per 12 hour shift,” a cab driver who identified himself as Jose wrote on the blog. “Why should we be tracked? Not even the city buses are tracked this way….What benefit is there to the driver?

The debate over the system derives to some extent from the fact that drivers and passengers do not always share the same interests. One of the supposed benefits of the technology is that it will make it easier for passengers to locate any items they mistakenly left in a cab, even without a receipt. The passenger will call a hotline, say where he or she was, and the tracking systems will determine which cabs were in that location at that time. A message will then go out to the drivers in that area to check their back seats for the lost goods. Certainly, if this works as advertised, it will benefit passengers. But cab drivers worry about lost time checking for items and then delivering them to their owners, particularly if the item involved is of little value, such as an umbrella.

THE COST OF TECHNOLOGY

The new system will cost an estimated $3,000 to $5,500 pr cab. This cost will be borne by the taxicab owners. Individual drivers fear the medallion owners could pass the costs on to them and that they could end up paying maintenance costs as well.

Beyond the initial cost, cab drivers fear fixing and maintaining the high-tech machines will take up precious time and hard-earned money.

But Daus, the taxi commissioner, has said the drivers were already compensated for some of those expenses when they city approved a 26 percent fare increase in 2004. And according to some reports, the drivers could get a commission from the advertising profits.

Tallying the financial costs and benefits of the plan for drivers is difficult. On the one hand, the technology will benefit the drivers because once they can pay with credit and debit cards, people may take more cab rides and give bigger tips. Since the fares will not be paid in cash, the money cannot be stolen from drivers. But the credit system will require the owners to pay processing fees. No one can yet determine what the bottom line will be.

THE NEXT STEP

The taxi commission wants the new systems to be in all yellow cabs by January 2008. But cab drivers have other ideas.

A strike is a possibility, according to the executive director of the Taxi Workers Alliance, Bhairavi Desai, "Drivers are angry and ready to take action," Desai, whose group represents about 7,000 cab drivers, said. Some protests have already been held. At one, in front of the Taxi and Limousine commission headquarters on Rector Street, about 100 demonstrators said they would take action to block the installation of the new technology.

But barring something unforeseen the high tech cab will be a mainstay of city streets by next year. And riders who want peace and quiet will have to turn off their monitors.

Â

Will the Critics Kill Congestion Pricing?

Mayor Michael Bloomberg proved prescient when he introduced congestion pricing in his Earth Day address as “the elephant in the room.” Before Bloomberg even delivered the speech outlining ways to make the city more environmentally friendly, some politicians shot down the most controversial idea: charging drivers $8 to travel below 86th Street during rush hour.

"I think congestion pricing is a non-starter," said State Senator John Sabini prior to the speech. "We're one city. I don't think we should penalize people for where they live."

The criticism, mainly from representatives of areas outside of Manhattan, hasn't subsided.

U.S. Representative Anthony Weiner, who plans to run for mayor in 2009, charged that the proposal "creates class conflict" and constitutes a "regressive tax on working middle-class families and small-business owners."

In a press release provided by the Queens Chamber of Commerce, City Council Finance Chair David Weprin called the proposal "another unfair tax which would hurt working-class people."

Walter McCaffrey, a former City Council member and spokesman for the Keep NYC Congestion Tax Free Coalition, said the idea that the fee would be kept at the mayor's proposed level of $8 per day is a myth. "Anyone who thinks it's going to be $8 is either delusional or they are trying to deliberately hoodwink the public," McCaffrey told the Daily News.

On the Fence – Or in Favor

So is the mayor's plan for congestion pricing dead on arrival?

Don't count on it. Some elected officials such as Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, who has vehemently opposed tolls on the East River bridges, and Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion are keeping an open mind. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver said he would like to see "what the proposed benefits are, and I'd like to see what the impact on business is projected to be."

The proposal has substantial support from business groups such as the Partnership for New York City. A coalition of 70 organizations and individuals ranging from the American Lung Association to the Citizens Budget Commission and General Contractors Association came out strongly in favor of the mayor's plan.

The plan can also attract federal funds to pay for the fee-collection system. U.S. Secretary of Transportation Mary Peters, in a statement following Bloomberg's speech, said the congestion pricing plan "is the kind of bold thinking leaders across the country need to embrace if we hope to win the battle against traffic congestion."

It is important to remember that this is just the start of the debate.

The mayor is clear about his commitment to his plan. He has prevailed in other areas where his predecessors failed, such as taking over the city school system. In cities such as London and Stockholm that have adopted congestion pricing, the idea gained support after strong initial opposition.

What the Charge Will Buy

As the debate continues, it is likely that New Yorkers will focus more on the benefits to them personally and the city at large. The mayor's proposal is not just about charging tolls.

Congestion pricing fees, combined with city and state contributions, would underwrite a new transportation financing authority that would fund $31 billion in transit projects in the metro area. The list of projects includes completing the Second Avenue subway, bringing the transit system and city roads and bridges to a state of good repair, implementing a total of 10 bus rapid transit routes, building a new rail tunnel from New Jersey to Manhattan and adding bus lanes to East River bridges.

Far more people will benefit from the mayor's plan than will be affected by the congestion fee. The mayor correctly pointed out that only 5 percent of New York City residents drive to work in Manhattan.

Even in outlying areas of the city that lack subway service, public transit commuters outnumber auto commuters by two to one or even three to one.

Transit commuters who currently endure hour and a half commutes can greatly benefit from the mayor's proposed upgrades to transit services, ranging from express buses to better utilization of the commuter railroads' city stations. If New Yorkers understand the benefits to their commutes, won't these folks weigh in with their elected officials?

Perhaps the most biting criticism is the claim that a fee is an unfair tax on the working person. Yet the fact is that outer borough auto commuters tend to have higher incomes than subway commuters, so a fee that improves transit is actually more equitable than the current system. In fact, auto commuters who use the free bridges are being subsidized by transit users whose taxes pay for bridge reconstruction and maintenance. Is that equitable?

What’s the Alternative?

Opponents will also have to respond to the public's increasing focus on environmental aspects of this issue. The mayor pointed out that childhood asthma rates are four times higher in the city than nationally. How unfair are steps to reduce vehicle emissions that carry these severe health effects?

Given the public's desire to see something done about traffic congestion, opponents will also have to convince people suggest that they have a better idea.

Councilmember Weprin called for "simple traffic mitigation alternatives to reduce congestion," but the city has made major avenues one-way, timed signals to maximize traffic flow, restricted turns and taken numerous other auto-friendly steps. Will the public buy the idea that a few more tweaks will significantly reduce congestion, especially in light of the anticipated city's growth?

Congestion pricing clearly faces an uphill climb. But the more New Yorkers understand the benefits of the mayor's entire plan, the more support congestion pricing is likely to increase.

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller, who has been in charge of the transportation topic page since its inception in 1999, is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Taking on the Traffic

There are powerful economic reasons for adopting Mayor Michael Bloomberg's congestion pricing policies. Thirty five years ago, I wrote a plan for the Lindsay administration that included tolls across the East and Harlem rivers. But to avoid the political heat of instituting tolls, our congressional leaders proposed to meet federal Clean Air Act's requirements to reduce auto use by making a serious commitment to capital financing for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. However, the investment of $40 billion in transit has demonstrated that transit improvements alone do not sufficiently curb auto use.

Now, 35 years later, we finally have a mayor with the insight and guts to take on the "elephant in the room" -- our failure to charge drivers more than a fraction of the costs they impose by using their cars. Motorists who gripe about raising their cost to drive don't appear to realize that car and truck travel create huge public costs-lost productivity from congestion, traffic accident costs not covered by insurance, environmental damage, air and water pollution and noise.

This is not trivial. In the New York metropolitan area, the costs related to cars and trucks total more than $40 billion annually. Every time someone drives into Manhattan it costs the rest of us $30.

The addition of the million more residents and 750,000 more workers envisioned by plaNYC will increase car and truck use by 2 million trips a day in New York City and add millions of daily riders to our subway system. Accommodating this growth will take billions of dollars of investment. It will cost even more if we are to meet the mayor's goal of cutting carbon dioxide emissions by 30 percent.

At the same time, auto-centric mega-development like Gateway Center and Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn and the Bronx Terminal Market will further clog our roads and subways. New York can do better. The plan that I proposed 35 years ago recommended creating what we then called "urban activity centers." These were to be new communities within New York City where people could live, work, shop and play within walking distance without having to drive or even depending on transit. Cobble Hill in Brooklyn is such a community. Bloomberg's plaNYC overlooks this approach to real sustainability.

The other key to a successful plaNYC is congestion pricing. While the system the administration has proposed is unnecessarily complex and costly, those features are negotiable. What is important is that we finally have a mayor with the vision and persuasiveness to embolden timid elected officials to see the true equity of congestion pricing and give it a try. This took great courage.

Motorists cannot defend getting a free ride into Manhattan and imposing huge costs on everyone else, including other drivers stuck in traffic. Congestion pricing is the only fair way to level the playing field. It is also one of the few ways left to secure funding to expand and improve public transit.

Brian Ketcham is a traffic engineer who lives in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn.

Â

Improve Transit Before Congestion Pricing

There are 24 transportation proposals in Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plaNYC, but one is getting all the attention: a pilot program to test congestion pricing.

The political battle is heating up over whether to impose a charge on motorists both to discourage driving in car-clogged Manhattan and to yield the money needed for big-ticket investments like the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access. The plan's transportation list also features smaller, less expensive improvements that could and should be implemented now, without waiting for congestion pricing.

We Have The Technology, But…

According to his own plans, the mayor has about two years to put congestion pricing in place. In all likelihood, it will take even longer - for technological reasons as well as political ones. The mayor's plan is modeled on London's geographic system: Vehicles entering the central zone during designated business hours must pay a flat fee. The proposal sounds simple: Charge every car $8 and every truck $21 for coming into Manhattan south of 86th Street between 6:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. on weekdays. But first, all river crossings, including those that are now free, and all southbound avenues at 86th Street, will have to be equipped with EZ-Pass readers. Cameras will have to be installed to find and fine violators, as in London.

And a number of details, while sensible, will complicate implementation:

-- Drivers will be credited for tolls paid at bridges and tunnels to and from Manhattan, requiring a new, system to reconcile fees collected by various charging entities, including the Port Authority and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

--Since moving a vehicle already within the zone will incur only half the fee, sensors and cameras will have to be installed throughout the business district, not just at the boundaries.

--Because cars moved for alternate-side-of-the-street parking will not be subject to the charge, the system must be able to distinguish among types of vehicle movements and trips.

--Many vehicles, including emergency vehicles, buses, taxis and cars with handicapped license plates - will be exempt from the charge, meaning the system will need to be able to recognize them.

All of this is technologically feasible. But information technology projects nearly always exceed the time and money budgeted by proponents.

Money for Transit

The city needs $2.7 billion for the first two phases of the Second Avenue Subway, $2 billion to connect the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal, and $175 million to reopen the defunct rail line along Staten Island's North Shore. Another $10 billion is needed to bring subway infrastructure and roads and bridges to a state of good repair.

The administration is anticipating state and federal contributions, but congestion pricing would be the most important local source of funds. Without congestion pricing, argues the mayor, the big projects cannot be built, nor is there money to complete repairs to existing transportation infrastructure anytime soon.

But Will It Reduce Traffic?

To get off the ground politically, congestion pricing cannot be seen as just a new source of revenue. New Yorkers have to believe that it will help reduce traffic.

The administration expects congestion pricing to decrease vehicles entering Manhattan by 6 percent and increase speeds within the charging zone by 7 percent. In other words, the traffic improvement in Manhattan would be modest.

However, the program will surely reduce congestion in neighborhoods like Downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City that have long suffered from through-traffic. The different costs for the various East River crossings have demonstrated for decades that tolls do affect driver behavior. The free Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro bridges, as well as their feeder roads, are clogged, while traffic flows more smoothly to and through the tolled tunnels. The mayor's proposal would correct this pricing irrationality by crediting drivers for the cost of their tolls. The price for a round-trip using E-ZPass through a tolled East River crossing is $8-exactly the same as the automobile congestion charge proposed for the pilot.

Many New Yorkers will welcome the news that the administration plans to step up traffic enforcement. In addition, The administration's plan to install Muni-Meters (modern, credit-card-friendly parking meters) should ease traffic problems related to curbside parking in business districts outside Manhattan. There are projects to expand ferry service and promote cycling.

But one of the most important potential reforms has gone unmentioned-doing something about the excessive amount of free parking in the city, especially for government employees. Because they often get unlimited free parking at a wide range of designated areas, government employees drive to work in the Manhattan central business district at just about twice the rate (27 percent versus 14 percent) of private-sector employees. To demonstrate its commitment to reducing congestion, the Bloomberg administration should eliminate free parking privileges for city employees-and urge other employers to do the same.

Make The Improvements Now

But the single most important thing the mayor can do to convince New Yorkers to give his congestion-pricing pilot a shot is to implement transportation improvements first. London increased bus service before implementing congestion pricing - and that was one of the keys to London's success.

In his "A Greener, Greater New York" speech, the mayor announced that transportation upgrades for underserved areas would begin right away, and plaNYC features a chart of improvements for 22 neighborhoods with concentrations of Manhattan-bound drivers. These include adding bus routes (College Point, Jackson Heights and Woodside/Sunnyside), adjusting bus routes (Bay Ridge, Canarsie and Cambria Heights), improving connections between bus and subways (15 of the 22 neighborhoods, including Co-op City, Soundview and Flatlands), changing traffic signals to favor buses (Schuylerville, Flatbush and Sheepshead Bay), and improving access to subway and rail stations (Clinton Hill, Kensington and South Ozone Park).

Starting these improvements now-transportation services that should already exist - will correct a long-standing wrong and make Mayor Bloomberg's ambitious vision more achievable.

Hope Cohen is deputy director of the Manhattan Institute's Center for Rethinking Development.

Â

The High Costs of Driving - and Parking

(Robert) Mosesian in its ambitious bid to establish a new transit financing authority, and (Jane) Jacobsian in its attention to the pedestrian and transit taking majority, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's sweeping transportation plan represents a welcome full frontal attack on traffic congestion and all of its attendant ills. Unfortunately, much of it depends on the state legislature. And so the mayor should take a closer look at something he can control: where New Yorkers park and how much they pay to park there.

Traffic ills -- health, economic and environmental -- are poised to get much worse. In addition to the much publicized influx of population and tourists and their attendant travel needs, the city is facing an estimated 83 percent increase in truck traffic (by 2020 over 1998 levels) and a torrent of new traffic unleashed by a bevy of major development projects like Atlantic Yards.

Despite the resurrection of Robert Moses' ambition, neither the mayor nor anybody in their right mind is proposing that we solve the problem with new roadways. The human and financial costs are too great, and new roads, we have long understood, just invite more driving.

Leaving Cars Behind

The wiser approach is to make better use of the street space we already have by switching car trips to methods of travel that make better use of our limited space. This "mode shift" forms the bedrock of the mayor's 16 green transportation initiatives. To make alternatives to the private car more appealing, the mayor wants to improve and expand bus service, enhance pedestrian access to transit stations and promote cycling with more paths and bike parking.

But two of the 16 initiatives hold by far the most potential to solve New York City's transportation problem: a $50 billion transit expansion program and a London-style congestion pricing system to help pay for it.

Congestion pricing, in addition to raising $400 million per year for the transit expansion program, would yield immediate transit benefits just by clearing away many of the cars that currently slow city buses. And by forcing drivers- especially city employees who currently drive at twice the rate as everyone else- to switch to subways and buses, the plan would significantly strengthen the political constituency for further transit improvements.

Even for the 5 percent of outer borough workers who currently drive to Manhattan (the other 95 percent take transit or drive elsewhere), congestion pricing holds benefits. Their commutes will shorten markedly, and all New Yorkers will benefit from cleaner air and less health eroding traffic.

As much sense as congestion pricing makes, its success is far from secure. For congestion pricing, and the long list of transit projects it would fund, to become reality, it must first gain the approval of a gauntlet of state legislators who with a nudge from the powerful parking and automobile lobbies could easily block it.

The Lure Of The Parking Space

Unless Mayor Bloomberg and Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff are content to leave their legacy in the hands of Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority leader Joe Bruno, they should pursue three parking policy reforms that would, like congestion pricing, reduce traffic and generate millions for transportation and street improvements. Unlike congestion pricing, these reforms do not require the approval of the state legislature.

Most Manhattan-bound drivers (in pdf) drive out of choice, not necessity. A recent Schaller Consulting study uncovered the reason why: Most drivers do not pay for parking. As any transportation expert will tell you, the carrot of free parking is too irresistible for drivers to refuse, even when they have decent transit options.

Government workers have their coveted (and often counterfeit) placards, and all drivers have access to a bounty of free and $1.50 per hour spaces, even if they have to circle the block for 40 minutes to find one. Because under-priced spots along the curb are always full, cruising for parking accounts for up to 45 percent of all traffic on city streets.

Three steps, used in other big cities, would enable the mayor to redress root causes of traffic congestion while generating a windfall to fund street improvements:

--Increasing the price for metered parking to a level that frees up spaces and reduces cruising;

--Charging residents for permits that would give them preferences for parking on public streets;

--Cleaning up the rampant misuse and abuse of city issued parking permits.

With a new generation of transit improvements funded by congestion pricing, Bloomberg and Doctoroff are poised to move mountains, if only they can move Albany. As a hedge, they should tackle what they can clearly control: New York City's broken parking policy.

Paul Steely White is executive director of Transportation Alternatives.

Â

Getting the Most from Congestion Pricing

Those who have labored a lifetime on the city's environmental fronts were blown away on Earth Day to hear our words articulated by Mayor Michael Bloomberg with more mastery and conviction than any of us have mustered. Brilliantly couching congestion pricing in the context of the city's survival, the mayor made it a moral imperative. To convince motorists there is a trade-off, the mayor shrewdly seeks to get tangible transit improvements in place before charging motorists for entering Manhattan.

But the Mayor and Governor Eliot Spitzer must act quickly if they are not to be hamstrung in their commitments to expand transit use. They must reverse New York City Transit's plan to junk 607 subway cars as new ones arrive this year and next. NYC Transit's reason for throwing away usable cars, which could also be rebuilt for one-third the cost of new ones, is that there is no yard space for overnight storage. Accepting that limit will leave NYC Transit with no spare cars, its smallest fleet ever, and unable to deliver the increase of subway service central to the mayor's plan.

The mayor cites bus rapid transit as a quick, high-visibility way to boost ridership, but even this will take too long if it relies on dedicated buslanes. What can be installed quickly is the high-tech component ofbus

Rapid transit -- a GPS tracking and radio communication system. This would eliminate much of the bus bunching that infuriates riders, and the monitors at each bus stop, posting wait times for each route, should help make waiting for a bus more tolerable, even seducing some drivers out of their cars.

Congestion pricing could be made simpler as well. A lot more funds would be available for transit users if the congestion fees were simply collected on the bridge spans and along 60th Street, rather than at dozens -- even hundreds -- of charging points south of 86th Street. Equalizing the charges on all crossings would provide a strong signal to motorists that it doesn't pay to drive out their way to avoid tolls. While the mayor's proposed adjustments in congestion charges levied in Manhattan may remove any advantage of untolled bridges, the complexity muddies the message.

Instead of capitalizing on Manhattan having just four untolled entries, the proposed multiple checkpoints, exceeding London's charging cordon, will be a lot more costly and may raise new objections to tracking motorists' movements.

Even the staunchest supporters of congestion charges in the boroughs see neighborhood parking permits as an essential element of any plan to reduce traffic. The permits would not guarantee a parking place, but would

Charge outsiders a hefty price for precious curb space. Fees and fines could be reinvested in streetscape improvements and effective traffic calming. Such measures would reinforce the quality-of-life benefits of tolls.

The old pre-E-ZPass image of bridge tolls of long spillback of traffic from toll plazas is dead. There is a growing concession in the boroughs that a seamless charging technology can unclog approach roads to free bridges from the lemming-like traffic that is drowning neighborhoods and delaying drivers. Armed with the mayor's powerful ability to change the political

equation, why not institute congestion fees in the fastest, most productive way?

Carolyn Konheim is chair of Community Consulting Services.

Â

Dorothy Coven

Dorothy Coven  Abu

Abu Dana

Dana Dan Milstein

Dan Milstein Tina

Tina Bill Yates

Bill Yates Rodney Tan

Rodney Tan