The Uniqueness of Dante de Blasio

As New York took in the extent of the win by Bill de Blasio in the Democratic primary for mayor, the impact of a powerful television ad starring his son Dante seemed plain.

The ad hit on de Blasio’s main campaign points of taxing the wealthy, ending a “stop-and-frisk era that unfairly targets people of color” and universal pre-K. But it was the messenger that made it a show-stopper: A mixed-race kid with an exuberant Afro speaking to the camera about how his dad was “the only Democrat with the guts to really break with the Bloomberg years.”

De Blasio’s wife is a black woman, and both Dante and Chiara (his daughter) are mixed race. With his family and the ad featuring his son playing key roles in his campaign, de Blasio split the black vote almost evenly with former comptroller Bill Thompson., the only black candidate for mayor

Remember, in the primary between Hillary Clinton and Obama, who is mixed race, in 2008 Hillary Clinton did better among white and Hispanic voters than she did overall, and Barack Obama won the black vote by a very wide margin in an overall close race. In terms of who voted for whom, race mattered.

{sidebar id=14}

As Joe Lenski, the man behind the exit polls, said in the Daily News, "I don't know if I could ever remember a race where a black guy is (close to) losing the black vote, the woman is losing the woman vote, the Jewish guy is losing the Jewish vote. It's quite impressive .... De Blasio did a good job of saying, 'I'm one of you even though I'm not personally one of you.' He was able to say, 'my wife is African-American, my kids are multiracial."

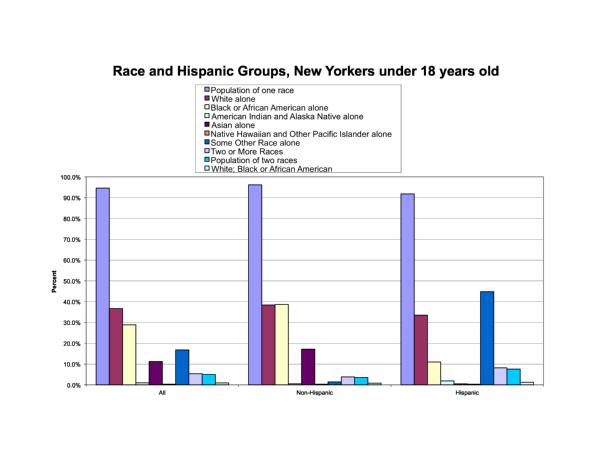

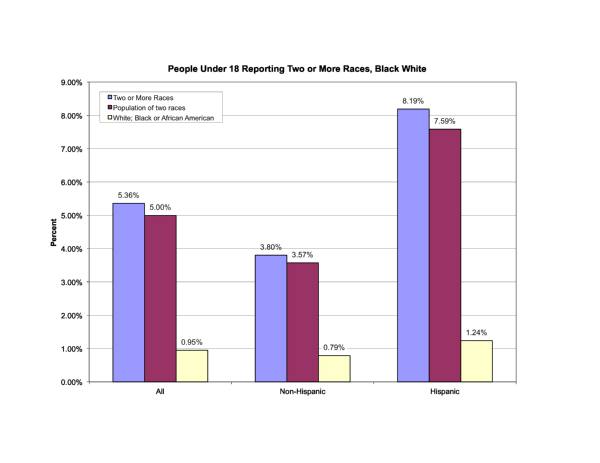

How unique is Dante de Blasio, the 16-year-old superstar of the 2013 elections, who communicated this important message? Just how many New Yorkers are non-Hispanic males who would identify themselves as black and white? An analysis of 2010 Census data shows that very few young New Yorkers are black and white, and even fewer are non-Hispanic black and white. Furthermore, there are much lower proportions of such individuals in New York City in the country at large. These data are presented in the accompanying table, and some are summarized in the two charts below.

For those under 18, there are 94,731 who report being of two or more races; 88,321 of these are of two races, and 16,735 are black and white. When one looks at those reporting that they are non-Hispanic black and white, there are only 8,980. Dante, it is plain, is in a very small group. However, these number also are self-reports; as has become obvious during the last few years, the genetic make-up of individuals does not necessarily mirror their self-reports.

The two charts also make it plain that the city has a lower proportion of multi-racial young people than does the United States in general; this is particularly true with respect to those reporting black and white. In the US as a whole, some 1.67 percent of youth are reported to be black and white, while in New York City the figure is 0.94 percent. (Other comparisons are in the accompanying table.)

But it’s clear that while Dante de Blasio may belong to a small group, the message he delivered was tailored for a much broader audience. It came in the midst of a contentious federal trial over whether the policy was unconstitutionally targeting black and Latinos.

Despite constant refrains by Bloomberg, Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly and some of the media to the contrary, the judge in the stop-and-frisk case, Shira Schiendlin, based her assessment of the practice on expert and factual testimony. Specifically, she drew her opinion on evidence that the police stops young blacks and Latinos disproportionately not only in terms of race and Hispanic status, but also in the neighborhoods that they tend to live in, and in terms of the crime rate in those neighborhoods.

Criminologist Jeffrey Fagan, the plaintiff’s expert in the case, in an article in the Columbia Law Review, has demonstrated that teenagers like Dante — who are perceived as black even though they may be mixed-race — have an 80 percent chance of being stopped. According to father de Blasio, he has discussed this with Dante at length to try to lessen his chances of being stopped.

Plainly, Dante’s uniqueness and the de Blasio family’s uniqueness, along with de Blasio’s position, which plainly attempt to address directly the concerns of many blacks and Latinos in New York City, helps to explain de Blasio’s electoral success.

But while the messenger may have been unique, it was the message that more than likely swayed voters to cast their ballots for his dad. Dante’s uniqueness and the powerful ad just made it possible for the message to get through.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer (www.socialexplorer.com), a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. He is co-editor of “New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future” (Oxford University Press, 2013). The opinions expressed are his alone.

New York’s Changing Electorate: What It Means for the Mayoral Candidates

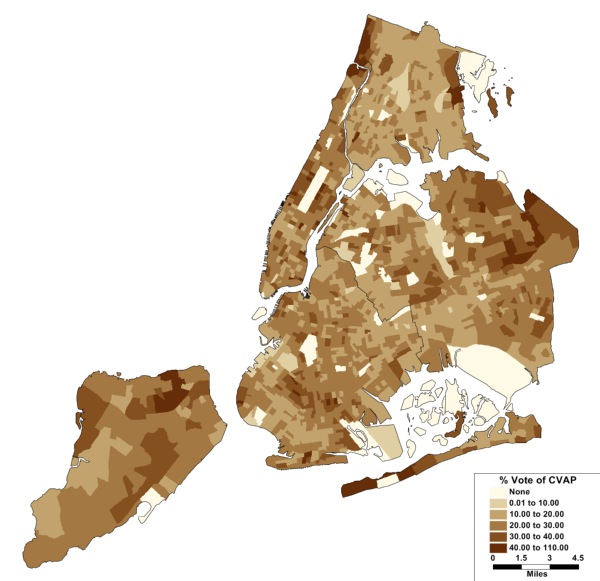

Most New York citizens of voting age do not vote — and they definitely do not vote in mayoral primaries or elections.

That means this year’s candidates, If they have any hope of getting to Gracie Mansion, will need to build coalitions of supporters willing to get to the polls on primary day and Election Day from an increasingly diverse voter roll.

When Barack Obama beat Mitt Romney for President in 2012, less than 50 percent of those in the city who could have qualified to vote did so, with some 2.5 million votes cast. When Michael Bloomberg beat former Comptroller Bill Thompson for mayor in 2009, only 24 percent of those who could have voted did so, with approximately 1.2 million votes cast. The ratios were similar for every election since 1989.

The record in primaries is even worse. In the contested Democratic and Republican primaries for president in 2008, less than 1 million votes were cast or about 20 percent. In the Democratic primary for mayor in 2009, only 330,000 votes were cast — which would mean that only about 11 percent of registered voters — and less of all of those who could enroll and probably would enroll as Democrats bothered to turn out.

New York City has roughly 4.3 million registered active voters and an additional 375,000 inactive voters as of April 2013. So registration of active voters is about 86 percent of citizen of voting age population. However, that number is misleading, since beyond the inactive voters, about 23 percent of NYC registrants are characterized as deadwood for either having moved or died since they registered.

In short, only small fractions of New Yorkers who could vote do vote, and many are not even registered.

Turnout isn’t the only challenge facing candidates; they also must deal with the diversity of the electorate.

Since David Dinkins was elected mayor in 1989, the New York City electorate has also changed substantially both racially and ethnically. Immigrants and their children — many of whom are either Hispanic or non-white — are now eligible to vote, while the proportion of non-Hispanic white voting age citizens in New York City continues to decline.

This shift, however, has yet to propel a non-white candidate to the mayoralty since Dinkins, though it is plain from the candidacies of Fernando Ferrer in 2005 and Thompson in 2009 that Hispanics and blacks will vote for one of their own.

Most notably, the proportion of the electorate that is non-Hispanic white has dropped from 54 percent in 1990 to about 42 percent for the latest year. Most likely it has declined even more since then.

At the same time, the percent of the electorate that is non-Hispanic black has declined to about 24 percent after increasing slightly from 1990 to 2000. Meanwhile, the Hispanic electorate has grown from about 18 to 23 percent, and the Asian electorate has gone from about 4 percent to about 10 percent.

While roughly 90 percent of voting age non-Hispanic white population are citizens, and virtually all Puerto Ricans are citizens, only 26 percent of Mexicans are citizens. For the other Hispanic groups, the range is from the 40 to 60 percent. For instance, about 59 percent of Dominicans over 18 are citizens. (Click to see the tables).

The same pattern holds for the Asian groups. For South Asians, generally about 60 percent of the voting age are citizens, while for the Chinese and Koreans it is also about 60 percent. Both the growth of the immigrant population and the length of time specific groups are in the United States and the extent to which such groups have children and their children become 18 affects the size of the citizen population of each group. So as time goes on, more and more will be citizens and thus have a potential political clout.

The South Asian group is now about 2 percent of the electorate, the Dominicans and Chinese are both about 5 percent, while the Puerto Ricans are 11 percent. All of the other groups are no more than about one percent — and often much smaller. Of course, they are larger in certain areas, but only in a few cases do they approximate an absolute majority.

What then are the general implications of these changes in the electorate and the fact that so few New Yorkers vote in the Mayoral and other local elections?

First, registration of citizens in any group is very important. Due to the limitations of the enrollment data (birthplace is not collected and the count is not an accurate reflection of who is actually in the city and registered to vote), it is very difficult to understand exactly what the registration level is for citizens for each group.

However, getting those who can to file citizenship applications and then get them registered is critical. Once they are enrolled, for a group to maximize its influence it is necessary for them to turnout and vote.

At the same time, because non-Hispanic white electorate has declined to near 40 percent, winning an election means that other groups must work in coalition. If the new groups are split apart or split among themselves and one or more candidates from each group runs a campaign that does not reach across groups, they will undoubtedly lose.

This is a lesson that John Liu learned when he unsuccessfully ran for City Council in 1997. He faced two other opponents of Chinese descent, and challenged an incumbent who famously characterized the increase of Asians in the Flushing area, as an invasion. It was also a hard-earned lesson in the 2001 election when term limits forced a large turnover in the City Council but the number of seats won by community and ethnic activists was very few.

Though the growth of immigrant and ethnic groups can empower such groups, to win elective office usually requires reaching across groups and ethnic divisions and fashioning a winning coalition. It is also means getting members of those groups through the citizenship process, registered and to the polls.

That last step — identifying and getting voters to the polls — is just as important to any candidate as gaining wide public recognition and developing a favorable image. This year’s election may have a high turnout for a primary, but a high turnout would be anything just above 15 percent of those eligible to vote.

Now that New Yorkers are beginning the process of choosing a mayor, looking at the data on the changing electorate simply reinforces the fact about how broad the appeal must be to win elected office in New York City.

Not only do Republican candidates need to go beyond the 16 percent of electorate who enroll in the GOP as Bloomberg and Rudy Giuliani did, but Democratic candidates need to get support beyond their ethnic group and local area to even have chance.

Given all of this, it is not surprising that few are certain where the current election will go, either during the primary in September, the likely Democratic runoff, or the final election in November.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer (www.socialexplorer.com), a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. He is co-editor of “New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future” (Oxford University Press, 2013). The opinions expressed are his alone.

What The Next City Council Will Likely Look Like

The next City Council will likely be demographically similar to the current one, though there may be an increase in both Asian and Latino membership.

That is one of the main takeaways from a review of the new Council lines approved by the city’s Districting Commission on Thursday but not released to the public until the following day.

A further look at the plan shows that it continues to protect incumbents, but was adjusted to accommodate some of the preferences of community and minority group advocates and others who complained loudly about the preliminary plan.

In addition, Lisa Hadley, a noted analyst of voting patterns in the context of redistricting, assessed the plan for any vulnerability to challenge by the Department of Justice and by Minority Voting Rights advocates and found that it unlikely to raise any issues.

Incumbency Protection

On average the new districts retain slightly over 87 percent of the population of the current districts, and 41 districts have at least 80 percent of that population.

Overall the plan continues the time honored tradition of incumbency protection, but it is worth noting that such concern for incumbents has been found by the Supreme Court to be a legitimate basis for redistricting.

However, there were noteworthy changes to districting lines that addressed concerns of critics.

A look at the data shows that a set of districts in northern Manhattan and the Bronx had large changes from 2003 to the new lines: Districts 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, and 15. It is also plain that 7, 8, 10, 14, 15, and 17, were changed substantially between the preliminary and the final plan.

This accommodates Hispanic and African American population change.

There was also substantial change between the current lines and the final lines, in Queens for Districts 25, 29, 32, and for District 39 in Brooklyn. Districts 25, 29 and 32 were modified substantially from the preliminary plan. Along with District 28, these changes satisfied some of the issues raised by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Nonetheless, the basic pattern except for the 10 districts noted, was for a plan that would serve to protect the incumbents or their likely successors.

Voting Rights Issues

Like many southern states and counties, the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn are subject to so-called pre-clearance by the Department of Justice.

This is to ensure that any changes to the voting system do not disadvantage minority groups: African Americans, Hispanics and Asians.

Generally a plan is tested to see if there is retrogression, which means that one would expect that fewer seats would be held by candidates of choice of minority groups.

The commission hired Lisa Hadley to conduct an analysis to assess whether the final plan met such a criterion. (I should note that in several cases, including a recent case in Port Chester, Lisa Hadley and I testified for the same parties. My work was more in formulating and analyzing the demographics of redistricting plans, while Lisa Hadley analyzed voting patterns.)

Hadley’s analysis finds that the plan passed by the redistricting commission preserves at least the same number of seats, where minorities will elect their candidate of choice compared to the current plan in the three covered counties.

I agree with Hadley on this, the plan will return a Council very similar demographically to the current council, though their may be an increase in both Asian and Latino membership.

A Jigsaw Puzzle

Redistricting for any jurisdiction is a series of tradeoffs among incumbency protection while following the five principles I outlined in an earlier column.

How these principles, along with incumbency protection, are implemented in practice depends on who is doing the map drawing. Redistricting is a bit like completing a jigsaw puzzle. All territory must go somewhere.

New York City redistricting is done by a Commission where a majority of members are appointed by the Council, while many of the mayoral appointees also have been very active politically. Though not exactly the same as being drawn by the Council itself, the Council still must approve the plan, and those in charge of drawing the map are beholden to the Council for their appointments.

If we had true non-partisan (as opposed to bi-partisan) redistricting in New York City, I am sure that incumbency would not play such a large role. (Indeed, it played little or no role in California, where the state’s recent redistricting was done by an independent non-partisan commission.)

Unless New York City adopts such a procedure, we can expect that the choice of constituents will still be shaped by the incumbents more than by the voters.

____

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer, a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

New Plan For City Council Districts

NEW YORK — A new proposed map for New York City Council district lines addresses some concerns of civil rights groups and reflects changing demographics, while also safeguarding incumbents.

But the Districting Commission was criticized for voting to approve the new plan at a meeting Thursday night before it had even released the information to the public. The full City Council must now approve the new map.

Since the commission also supplied an analysis related to the Voting Rights Act by Lisa Hadley, a renowned expert in that field, it is clear that the revised plan had been crafted days ago and could have been released at the Commission’s discretion.

The above map presents a view of the revised plan for new Council districts, along with whether or not the current incumbent is term limited. Courtesy of Social Explorer.

It took until Friday afternoon for the revised district plan to be posted on the Commission’s website for the public to view it.

Asked why the map was not released to the public before the Commission voted to approve it, the Commission’s executive director, Carl Hum, said there was still time for the public to make its comments on the plan.

“If there is a desire by the public to have more hearings, they can certainly voice that to the Council,” he said. The Council could also reject the lines, forcing the Commission to hold another hearing. “The process is far from over.”

He said that the new map was drawn taking into account comments from the public, civil rights groups and legislators, as well as maps created by members of the public.

Responding to criticism that the lines had been drawn to protect incumbency, he said legislators’ also had a stake in the process. “While not saying that's the primary consideration, or the overarching consideration … It is part of the toolkit,” he said.

>>>>Read Andrew A. Beveridge's analysis of the preliminary maps and how they protect incumbents.

Unlike the state, the city has a non-legislative redistricting commission, which has held hearings and a series of maps.

The commission consists of 15 members — seven appointed by the mayor, five by the Council Democrats and three by the Council Republicans. One third of the commissioners are from Manhattan, which has about one-fifth of the population, two from the Bronx and Brooklyn each, and three from Staten Island and Queens each.

This structure is seen by some political observers as an advance over the redistricting process at the state level, where legislators themselves were able to draw the lines for the Assembly and Senate lines after Gov. Andrew Cuomo waffled on his promise to veto any maps that were clearly gerrymandered.

Nevertheless, the proposed maps have been criticized for dividing neighborhoods and ignoring communities of shared interest.

>>>View a table about the new districts under the revised plan, including the incumbent, the year elected, term limit status, voting age, citizenship, race and Hispanic status.

The Unity coalition of minority advocates — including LatinoJustice PRLDEF, Asian American Legal Defense And Education Fund, and Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College — presented a common plan that attempted to keep neighborhoods intact and attempted to maximize the influence of African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans on the new Council.

In a statement released after Thursday night’s vote by the Commission, AALDEF noted that under the new proposed map that several Asian American communities remained divided but that some of the Unity Map’s suggestions were taken into account.

Jerry Vattamala, a staff attorney with ALDEF, said in a statement that the Commission’s proposed map “has room for improvement in enabling New York City’s federally protected communities of color to have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.”

___

Image of New York City, seen from space, courtesy of NASA.

Proposed City Council District Map Protects Incumbents

Editor's note: This commentary is based on the preliminary lines that were released before Thursday night's meeting by the Districting Commission. We will be updating it with additional information as it is released.

NEW YORK — The once-a-decade drama of redistricting the New York City Council is almost complete.

Much is at stake, not for party control, but over who will represent many of the city’s increasingly diverse neighborhoods for the next decade beginning with the 2013 election. Redistricting must be undertaken after each federal decennial Census.

The city's Districting Commission, appointed by the mayor and Council leaders to redraw the lines, voted unanimously in favor of a revised plan at a public meeting Thursday night. The new map has not been made available for review. The full City Council must now approve it.

The current Council has 46 Democrats and five Republicans. In 2013, an additional 18 seats will be open due to the impact of the change in the city’s charter regarding term limits. How those districts are drawn will have a lot to do with recruiting new political leadership in New York City for the next decade.

Unlike the state, the city has a non-legislative redistricting commission, which has held hearings and presented preliminary maps of the boroughs.

The commission consists of 15 members — seven appointed by the mayor, five by the Council Democrats and three by the Council Republicans. One third of the commissioners are from Manhattan, which has about one-fifth of the population, two from the Bronx and Brooklyn each, and three from Staten Island and Queens each. The most populous boroughs (Brooklyn and Queens) have almost three-fifths of the population, but the same number of commissioners as Manhattan. Staten Island, with not even six percent of the city’s population, has one-fifth of the commissioners. The commission has an executive director and a staff.

This structure is seen by some political observers as an advance over the redistricting process at the state level, where legislators themselves were able to draw the lines for the Assembly and Senate lines after Gov. Andrew Cuomo waffled on his promise to veto any maps that were clearly gerrymandered.

But since they are appointed by the mayor and the Council, it is perhaps unsurprising that the commissioners charged with redrawing the city's districts would follow the age old practice of “incumbency protection”: In the draft map that was released before Thursday's vote on a revised plan, district lines were tweaked at the expense of splitting some neighborhoods. This is a classic example of protecting those already in office by minimizing the amount of change within district lines — after all, probably the worst thing that can happen to an incumbent is to force him or her to run in a new district.

This seemingly business-as-usual approach appears to be in stark contrast to the Districting Commission’s efforts to be transparent about the process, allow for community input at hearings in the various boroughs and through an invitation to members of the public to submit their own proposed maps. Nevertheless, the proposed maps have been criticized for dividing neighborhoods and ignoring communities of shared interest.

The Unity coalition of minority advocates — including LatinoJustice PRLDEF, Asian American Legal Defense And Education Fund, and Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College — presented a common plan that attempted to keep neighborhoods intact and attempted to maximize the influence of African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans on the new Council. Most of their suggestions were spurned, likely because many of them would have made it much more difficult for incumbents to keep their seats, or would have forced incumbents to accommodate themselves to new neighborhoods.

Despite the outcry from the Unity coalition and other groups, the Commission has proposed a plan that is basically same-old, same-old.

The above map presents a preliminary view of the new Council districts, along with whether or not the current incumbent is term limited. Click to enlarge. Courtesy of Social Explorer.

Redistricting Standards

To successfully complete redistricting and not be subject to challenge under federal law, the following principles must be followed:

- Relative population equality — generally, this is interpreted as being within plus or minus five percent of the average or ideal district size based here upon the population adjusted for prisoner locations.

- Contiguity — that the districts are in one piece.

- Compactness — that the districts are compact in shape.

- Political boundaries — that the districts do not split political or community boundaries.

- Given all of the above, that they keep racial and Hispanic communities together.

The fifth provision is very important in New York City, since the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn are subject to pre-clearance by the U.S. Department of Justice. One of the main issues with pre-clearance relates to retrogression, meaning that the number of seats with a majority of the various minority groups from the 2003 districts must result in the same number or more seats unless population change makes this impossible.

It is this last point that has created the presents the biggest challenge to the Commission’s map-making.

Current Districts and Need for Change

Since redistricting is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, that 12 seats need to be adjusted, means that many more than that will be impacted, because the extra population to be added or subtracted from these 12 districts will need to come from or be put elsewhere. So substantial redistricting was necessary.

The Council currently has 2 Asians, 15 blacks, 8 Latinos, and one Black/Latino Councilman. But non-Hispanic whites make up 25 of the 51 seats in the Council. In terms of minority majority seats, the new Council will have nine majority Latino seats, 11 majority African American seats and one seat that is almost majority Asian. There are 21 non-Hispanic white seats and nine with no majority. Of those nine, five are plurality non-Hispanic white and four are plurality Hispanic. Based upon proportional representation by seats, the current Council is over-performing in returning minority districts.

>>>View a table about the new districts under the preliminary plan, including the incumbent, the year elected, term limit status, voting age, citizenship, race and Hispanic status.

The Unity coalition proposed a plan that would result in one more majority black district and one less majority Hispanic district. The Unity coalition asserts that their plan divides fewer neighborhoods. Such changes would be even more disruptive to the current set of incumbents, so was not seriously considered.

Of the council members retiring, six are black, one is black/Latino and two are Latino. In terms of majority seats, four are black, three are Hispanic, seven are majority non-Hispanic white and four have no majority. Of those four, two are plurality non-Hispanic white, and two are plurality Hispanic.

Based upon simple block voting, one might expect fewer black seats and more Hispanic seats. However, the last time that there were a large number of term-limited Council members, the vast bulk were replaced either by staff aides or family members. Few community activists or others could not find the wherewithal to win and sometimes to remain on the ballot.

One should expect that the 2013 election will be no different. Given the limited nature of the redistricting, I would expect that the new Council will maintain just about the same demographic profile as the current Council despite both population shifts and term limits.

____

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer, a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Image of New York City, seen from space, courtesy of NASA.

The Attempt to Kill the ACS: Its Implications for New York City

The map is an example of data available through the American Community Survey. It shows median household income from 2000 to 2006-2010. Maps courtesy Social Explorer.

Starting in 2005, the U.S. Census Bureau replaced the long form that the agency had relied on every 10 years to measure change in the nation's demographics with an annual survey that would deliver a much more immediate snapshot of the population. Now we have data that were available only once a decade, every year.

Today, the American Community Survey is used across the country by researchers, businesses and policymakers. Almost anything that a person would want to know about the population of the U.S. – from income to disability – can be found from a review of the data.

For New York City or, for that matter, any community across the country, the ACS is a critical tool for understanding demographic change down to the neighborhood level.

Given its importance, then, it might come as a bit of a surprise that the Republican majority in Congress wants to get rid of the ACS – and has even put forward an amendment to do so – arguing that it represents an unconstitutional invasion of privacy.

“It would seem that these questions hardly fit the scope of what was intended or required by the Constitution,” said Rep. Daniel Webster (R-Fla.), author of the amendment. "This survey is inappropriate for taxpayer dollar… It’s the definition of a breach of personal privacy. It’s the picture of what's wrong in Washington, D.C.”

It should, perhaps be noted, that there is no documented case of identifiable Census information falling becoming public or being used in an unauthorized way.

Compared to the data harvested by Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Amazon, Google, your credit card company and your healthcare provider, Census information is mostly quite benign. However, the ACS does collect information about race, ancestry, income, and marital status.

While the survey is not part of the constitutionally mandated population count, some version of it has been done by law as part of the decennial survey since the time of Thomas Jefferson. Virtually all questions on the current survey are there because of various Congressional mandates.

There has been an outpouring of support for the ACS, including from the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal: “Since the political class is attempting to define the GOP as insane and redefine â€moderation’ as anything President Obama favors, Republicans do themselves no favors by targeting a useful government purpose.”

The Times, in another editorial, pointed out that Webster has a link to ACS data about his district on his own website.

The outright ban is not expected to pass the Senate, but a bill making the ACS voluntary has been introduced there, and has already passed the house.Making the survey voluntary is certainly a possibility and would make it both more expensive to administer and less accurate and valuable, based upon the experience of Canada, which made a similar survey voluntary.

It is also possible that the House GOP will stick to its guns in committee and the Democrats will let the ACS be killed or compromised.

A recent workshop sponsored by the Committee on National Statistics of the National Academy of Sciences highlighted several hundred uses of the ACS, outside of the US government. Commercial users include Target Stores, Wal-Mart and others, as well as virtually all marketing research firms, political pollsters and so on. (The presentations are available here.)

Many of the Federal uses are mandated – including looking at commuting patterns to help plan transit facilities; understanding the affordability of housing; allocating funds for community block grants; allocating funds to school districts with high levels of poverty or immigrants; providing language assistance for voting; and assessing the need for free or reduced lunch at public schools.

Here's just a sampling of the ways that the ACS can be used to show important demographic change in New York City:

- That earnings for full-time workers showed a decline of 1.6 percent for all workers from $46,721 to $45,496, while for men the decline from $48,976 to $45,619 represents a drop of 6.9 percent. For women, the $43,126 to $42,198 decline is about 2.2 percent.

- That the proportion of the population now married declined from 43.4 percent to 39.0 percent from 2000 to 2010; the proportion of unmarried couple households increased from 5.2 percent to 6.2 percent; while those reporting same-sex unmarried partners showed a slight decline from 0.9 percent to 0.8 percent. (This may be due to the Census allowing same sex households to now report that they are married couples.)

- That, in 2000, 16.5 percent of all households had incomes of at least $150,000, but that by 2010, 17.1 percent of households had such incomes. Meanwhile, the median household income in the city had declined from $50,120 in 2000 to $48,743 in 2010 – a drop of about 2.5 percent. In other words, more New Yorkers had become very affluent, but the typical household had seen an income decline.

But forget about knowing all that if policymakers do away with the ACS. Politicians and researchers will know a whole lot less about who resides in the country, how they are faring and how the country is changing.

This may be the way the GOP House Majority would prefer it – so that politicians and commentators can make their appeals based upon opinion with no chance of contradiction or fact-checking. Of course, they point to cost-saving to tax payers and its supposed impact on privacy.

But the ACS’s demise will deprive the city and the nation of a major source of important information that researchers have relied on for decades.

It would be like asking astronomers to do astronomy without telescopes and physicians and biologists to work without microscopes.

____

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer, a premier on-line demographic web site, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Queens Groups Are Divided Over District Lines

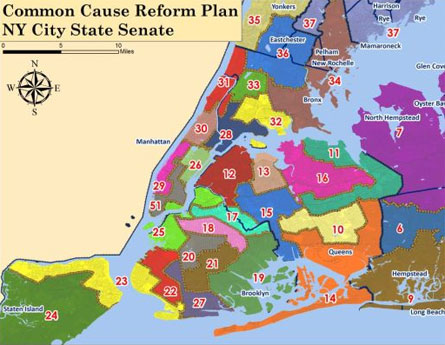

District Lines by Common Cause

With the preliminary redistricting maps to be announced next week, tensions are rising in Queens, where communities are split along legislative lines and rival plans to redraw them.

Many Asian-American groups, joined by some Latinos, have pushed for State Senate and Assembly borders to be redrawn around a single, cohesive Asian community which would cut across Queens and Nassau county lines. Others, led by the group Eastern Queens United, have categorically opposed this.

The groups’ main argument centers around what constitutes “communities of interest” and whether or not race and ethnicity is a key factor in determining these. Moreover, politicians and analysts have said that grouping voters from the two counties together will give Republicans an edge. Both sides have distanced themselves from party considerations.

“We were able to meet with numerous groups throughout the city and develop community boundary lines and narratives to accompany them,” said Jerry Vattamala, a staff attorney with the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF).

Asian-Americans are a growing population in New York. Over the past ten years, the number of Asians in New York City has risen from about 1 million to about 1.42 million, growing from 5.5 percent to 7.3 percent of the total New York population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Over 500,000 Asian Americans live in Queens.

The influx came mostly from immigration, according to James Hong, the Civic Participation Coordinator at MinKwon Center for Community Action, a Korean group. He said that many Asian-Americans who live in these areas have common interests, especially with regard to immigration law, language accommodations and socioeconomic concerns.

Despite their growing numbers, Asian voters are under-represented because their communities sit on top of many legislative partitions, according to AALDEF. Asian communities in Richmond Hill and Elmhurst are split into as many as six assembly segments, said Vattamala.

The current lines “absolutely split up Asian-American Communities,” said Hong. “The effect of diluting the Asian Vote has been very significant.”

In July 2011, 14 Asian-American groups including AALDEF and MinKwon have teamed up to form the Asian-American Community Coalition on Redistricting and Democracy (ACCORD), which has endorsed a proposed redistricting plan called “Unity map." The map was created by AALDEF, PRLDEF (Latino Justice group), the National Institute for Latino Policy and the Center for Law and Social Justice of Medgar Evers college. It was submitted it to the state’s legislative task force on redistricting.

But many other residents and politicians of Queens are opposed to the Unity plan, saying that it doesn’t make sense to put residents of Queens and Long Island in a single Assembly or Senate district. Eastern Queens United, which includes civic groups from Glen Oaks, Floral Park, New Hyde Park, Bellerose and Queens Village, said that the common interest of Queens communities far outweighs any common interests along ethnic lines.

“This is unacceptable,” said Bob Friedrich, the President of Glen Oaks Village Cooperative. “We don’t wan to divide these communities along ethnic, color or religious lines. It serves the needs of politicians to divide these communities.”

Eastern Queens United held a community meeting last week, discussing the redistricting. Assemblyman David Weprin and State Senator Tony Avella attended the meeting, with Avella pledging to vote against any plan, which cuts legislative districts across county lines.

“I understand the goal and agree with it but the way they’ve gone about it is not only inappropriate, it’s reverse gerrymandering,” said Avella, who has met with ACCORD and criticized its proposals. He said that the coalition’s proposals have only gotten worse since they were initially proposed and that they would give Republican legislators an unfair edge in Queens.

He added that as of October 12, ACCORD admitted to failing to consult with South Asian groups whose interests might be different than those of Chinese and Korean Americans. MinKwon’s Hong denied this claim, saying that ACCORD had met with many South Asian groups, including Taking Our Seat as early as July 11.

Still, many lawmakers and analysts think that combining sections of Queens and Nassau Counties would benefit Republicans because of the large number of conservative voters that live in Nassau. Arthur “Jerry” Kremer, a lobbyist and former Assemblyman said that there are no communities of interest that cross county lines that “it is not uncommon for minority legislators to find that their districts are cut up and combined with others.” He added, however, that significant change in Nassau County is likely this time around.

Both ACCORD and Eastern Queens United have denied that their proposals had to do with partisan considerations. Spokespeople for each have said that their primary interest is keeping communities together.

Senator Martin Malave Dilan said that the likeliest areas to see change in the coming redistricting process are in Queens/Nassau, Hudson Valley and the Saratoga area. However, Dean Skelos, the Republican Senate Majority Leader, said that the 63rd senate district will not be in Long Island. Eastern Queens United’s Bob Friedrich said that this was a good start while ACCORD offered no comment.

A previsous version of this article incorrectly named ACCORD as the author of The Unity Map.

Common Cause Helps the Public Get Involved in Redistricting

Map by Common Cause

Common Cause maps the city's Congressional Districts.

This week a number of Assembly Democrats got a peek at what their new district lines will look like if the Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment has anything to say about it. And LATFOR, with legislative leaders, has for decades had the final word on drawing district lines for the state. The process of redistricting was conducted in secret, lines were drawn to protect incumbents and maintain the senate Republicans’ majority, legislators were consulted on what would be convenient for them. The people were as far away from the process as possible.

Even when their plans were challenged in the court as politically motivated or inherently in violation of the law, LATFOR and the majority leaders came out on top.

But this time things have changed. Thanks to the internet, the process by which legislative districts are carved up is no longer such a mystery. Mapping technology allows any citizen with a computer, some spare time and the proper information to draw up their own set of maps. Earlier this week Common Cause issued their own lines and teamed up with Newsday to present the public with an interactive mapping tool so that they can try it themselves.

"We have been outspoken about the problems with the current process, which is characterized by partisanship and political self-interest," said Common Cause’s executive director, Susan Lerner, during a conference call with the press. "Our goal has been to show that there is no practical impediment—it’s only a political one—to achieving fair, non-politicized district maps."

Looking for Input

"It is kind of like pulling back the curtain,"said Sen. Liz Krueger, who has been looking forward to seeing Common Cause’s lines for months. She apparently wasn’t the only one.

Assemblyman Jack McEneny, Democratic chair of LATFOR, said that he and his colleagues have been waiting to see what Common Cause produced, and the plan is to utilize parts of their maps.

"We have been anticipating them for some time," said McEneny. "We will take a look at them and see what good parts we can incorporate into our plan. Then I would expect we will begin to have public hearings in January."

As for what it feels like to have the public breathing down his neck while he is doing a job that used to be draped in secrecy, McEneny said, "Things have changed. It is part of democracy to be second guessed. We grow up thinking things are either good or bad, but there is a lot of gray here, a lot of competing interests and groups who value certain things over others."

The Power of Politics

Although they are happy to see the public given a chance to be more informed and involved in the redistricting process, members of other good government groups are skeptical that Common Cause’s efforts will change the end result.

"I think they (Common Cause) looked at lines in a non-partisan manner, and that is refreshing. It looks to me that they managed to keep communities of interest together without regard to incumbents, and that is refreshing. But I don’t think it will make a darn bit of difference. I don’t think LATFOR has regards for anything but incumbency protection," said Barbara Bartoletti of the League of Women Voters.

Dick Dadey, executive director of Citizens Union (Gotham Gazette is published by Citizens Union Foundation, the sister organization to Citizens Union), agreed with Bartoletti.

"I think the maps are very instructive of how impartial districts could be drawn but I’m doubtful they will be utilized by LATFOR because of the political reality," said Dadey.”

The Compromise

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has promised to veto any lines that are drawn up by LATFOR, but he has also indicated that a veto would cause chaos—chaos that he would like to avoid. For months Cuomo’s office has been negotiating for a compromise that would avoid a veto. So far nothing has come of it. Cuomo’s office did not return calls for comment.

If such a deal came together it is unlikely to make use of Common Cause’s maps, as they are based on the kind of change that would happen if politics were not involved, whereas current negotiations are based on what will get senate Republicans to the table to agree to some sort of compromise.

Dadey said that he has spoken with the three parties involved in the negotiations. "Even though we may add a level of openness to the 2012 process it will be a political decision and Common Cause’s maps are apolitical," said Dadey.

The idea is to achieve a deal that would see less drastic change this year but perhaps something more substantive for the next round of redistricting in ten years. There is a sense among some at the negotiating table that Common Cause’s lines could frighten Senate Republicans away.

"To achieve reform we will need the unusual convergence of interests that include the Senate Republicans. Any reform any reform must treat all parties fairly now and in the future," said Dadey.

Others see things differently. They think the lines might make Senate Republicans more apt to make a deal that would avoid a veto, which would mean putting their future in the hands of a judge—especially when a judge could use Common Cause’s lines as an example of what districts might look like with without legislators drawing them.

But other advocates point to New York’s demographics and the fact that a majority of New Yorkers are registered Democrats.

Krueger thinks that Common Cause’s lines will serve as a guide post for LATFOR, Cuomo, or the courts if it does come down to a veto. Now that the public has been informed about the process, Krueger thinks it will be hard for LATFOR to ignore the fact that people are watching and won’t accept the excuses LATFOR used to make, excuses like, "There was no other way we could have drawn them."

Common Cause isn’t the only group allowing people to try their hand at redistricting. Fordham University is holding a competition for teams to redraw New York’s district lines. One of the participants is a ten-year-old child from Michigan.

Just How Bad is it?

A recent report by Citizens Union showed just how integral the redistricting process has been to keeping incumbents in their seats and maintaining the balance of power in Albany. The report showed that 96 percent of incumbents have been reelected since 2002. In 2006 100 percent of incumbents were reelected. The report shows that the current redistricting process makes elections far less competitive and as a result reduces voter turnout. Furthermore the report shows that minorities are underrepresented. "There are 15 different Assembly districts in New York City where the Asian-American population exceeds 20 percent, but there is only one [Asian] representative in the Assembly," Citizen Union’s Alex Camarda.

10 Years Later: Enumerating the Loss at Ground Zero

Photo by Joshua Schwimmer

The direct losses to New York and the United States from the World Trade Center attack are incalculable when one considers the personal and emotional loss to family and friends of the victims, as well as to all other New Yorkers, who have contended with the specter of 9/11 during the past decade. Yet, the magnitude of the losses and especially the recovery are being calculated daily. Indeed, Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently claimed: "As we look back on the past decade, and as the picture of what has happened here comes into sharper focus, I believe the re-birth and revitalization of Lower Manhattan will be remembered as one of the greatest comeback stories in American history."

Other aspects of the impact of the tragedy also can be measured. Here we use demography to look at the victims, the neighborhood and the financial businesses -- the so-called FIRE or Finance, Insurance and Real Estate, sector -- to gauge the magnitude of the loss and extent of the recovery from 9/11 for Manhattan and the city. As we will see though Lower Manhattan has come back in certain respects, Manhattan no longer accounts for over half of all employment in the FIRE sector. Perhaps, this is not surprising given the magnitude of the attack.

Individuals and Businesses Lost

Information provided by the medical examiner and the Federal Emergency Management Agency and unearthed by the New York Times helped fill in the picture of this unprecedented catastrophe. Census information on businesses and those working in lower Manhattan before the attack throw into high relief the stark dimensions of the direct toll.

All of New York City and the United States lived through the attack, but those who died came from very narrow slivers of space, both actual and socio-economic. Indeed, more than two thirds of the 2,753 victims, or at least 1,946, died on the upper floors near or above where the planes crashed: the top 19 floors of the North Tower and the top 33 floors of the South Tower. When one adds the firefighters (343), police and other rescue workers (about 90) and the victims from the two planes (157), one has accounted for almost 90 percent of all victims.

The bond trading firm Cantor Fitzgerald lost 658 employees; Marsh and McLennan, an insurance firm, 295; Aon, another insurance firm, 176; Fiduciary Trust International, a financial firm, 87; the Port Authority, 75; Windows on the World Restaurant, 73; Carr Futures, a brokerage firm that is now part of Newedge, 69; Keefe, Bruyette and Woods, a security brokerage firm, 67; and equity analysts Sandler O’Neil and Partners, 67. All these companies had offices on high floors in the towers. Risk magazine, the trade bible of the derivatives industry, which defined much of finance in the last two decades, was having a conference at the top floor restaurant Windows on the World. Everyone in attendance, including many high executives, perished.

Given the firms for whom many of those in the World Trade Center worked, as well as the large number of firefighters and other rescue workers, the other demographic facts should not be that surprising. The victims were overwhelmingly male (about 75 percent), young (many under 40, most under 50) and white (about 75 percent). Only about 8 percent were black, 9 percent Hispanic and about six percent Asian. About 75 percent were born in the United States, and the others originated from many different countries. Together New York and New Jersey residents accounted for about 87 percent of the victims. Many of the airplane passengers came from Boston and California.

As for the neighborhoods where the victims lived, we now know that the Upper East Side had the most losses (44), while Hoboken, N.J., had the highest proportion of loss of any single area, losing 39 residents, or about one per thousand. Given the high paying jobs at many of the companies in the World Trade Center, it is not surprising that many of the victims lived in very affluent parts of the metropolitan area, including the Upper East Side and Basking Ridge, N.J.

10048 and the Financial District

The World Trade Center had its own ZIP code, bounded by West, Vesey, Church and Liberty streets. According to the census, in 2000 only 55 people resided in that zone, but in terms of business activity, the area was something to behold. Within its boundaries, some 1,294 establishments employed about 31,119 people, and 928 of these firms were in finance or real estate, including insurance.

Altogether, the 1,294 companies paid about $3.9 billion (all figures are in 2009 dollars) in wages and salaries, averaging about $126,000 per employee, far higher than the average for the New York metro salary of about $69,300 per employee. Few other ZIP codes and none outside of the Financial District rivaled the World Trade Center in generating employment income per employee. Most of the stores, restaurants and other retail establishments paid high rent to be in the trade center. Sandwich shops and other establishments, where less well-off employees worked, were mostly "just" across the street in another ZIP code.

Lower Manhattan accounted for about 3 percent of the employment and over 5 percent of the earnings in the large New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania Metropolitan area, which extends to Montauk at the tip of Long Island in one direction and to Hope County, Pa., in the other. The finance sector accounted for about 9.2 percent of the employment in the entire region, but 19.2 percent of the wages paid in the New York metropolitan area in 2000.

The 2,000 or so victims who worked in offices will never return to their desks at the World Trade Center. The many victims who served them -- from the staff at Windows on the World, to the firefighters and other emergency personnel who tried to save them --will not return either. Beyond them, another 30,000 workers, who used to work at the trade center, also do not go there anymore.

The loss of ZIP code 10048 represented a blow to the heart of the financial district. Indeed, those working there, though just a small slice of the city's population, nonetheless represented many aspects of New York City society: the wealthy older executives at the Risk conference or running some of the firms, the young traders on the make (some of whom no doubt spent their very high incomes), the immigrants working in the service fields, the computer techs, the lawyers and others all supporting the financial community defined ZIP code 10048.

The Neighborhood Today

Ten years on, data suggest that the recovery from the 9/11 is not yet complete, neither for Manhattan's financial sector nor for the area in lower Manhattan that included the World Trade Center. Many more people live in Lower Manhattan today than were counted in the 2000 census, as the singular focus on finance and the rest of FIRE sector could have dimmed.

Considering employment in downtown Manhattan south of the Holland Tunnel, in 2000 there were about 248,000 employees with average salaries of about $120,000 per year. By 2005 that figure had risen to 271,000 averaging about $115,000. By 2009 in the midst of the financial crisis, the number had declined to 268,000 and the average income had dropped to about $106,000. Though employment is up somewhat, the average wages, even before the boom and bust, has lagged those in 2000, indicating, perhaps, more employment in other less lucrative sectors and less employment in the extremely lucrative FIRE sector.

When one looks at the entire financial sector including real estate and insurance, it employed just over 400,000 people in Manhattan in 2000 with average salaries of $202,000 per year. By 2005, the number had declined to 374,000 employees who averaged $208,000, and by 2009 some 362,000 employees averaged $195,500.

Though Lower Manhattan seems to have recovered in terms of employment if not in terms of income, the financial sector in Manhattan seems to have taken a blow from which it has yet to recover. When the financial sector in Manhattan is compared to financial sector in the entire metropolitan area it is plain that some of its jobs have moved away from Manhattan. The sector in this larger region showed some decline to 2005 and then a small increase to 2009. In 2000, Manhattan accounted for 50.7 percent of the employment in finance in the wider metropolitan area. By 2005 that percentage had declined to 46.6 percent, and by 2009 it dropped further to 44.0 percent.

So 10 years after 9/11, exactly what will happen to the area that was designated 10048 has yet to be fully determined, as conflicts continue over what will be built in the shadow of the towers and who will occupy the new offices. Beyond 10048, however, the financial sector seems to have not recovered completely, though employment, if not average income, has continued to increase in lower Manhattan. It seems Manhattan has permanently lost a substantial share of the financial sector.

It is true several banks and other businesses are planning sites inlower Manhattan and in the area around the trade center, and many have moved back to the areas. Despite all of that, the FIRE sector in Manhattan still is diminished and seems to be declining relative to the rest of the metropolitan area. So beyond the memories of the victims and the grief of their families, Manhattan and New York City are likely never to fully recover the losses to the financial sector brought on by 9/11.

Source Note: All the data regarding the number of employees and wages paid are from the County Business Pattern data,which includes some data on Zip Code Business Patterns)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Under a new name, census data stands ready for perusal

Photo by PaulSh

The 2010 census has been rolling out since February with New York state getting the first of its data on March 24 and more data releases during the summer. Yet, almost every day reporters, redistricting specialists and even other demographers ask when data to answer questions such as the following will be released:

- When will we know the number of immigrants in New York City and in various neighborhoods throughout the city?

- How many Hispanic citizens of voting age live in Washington Heights?

- Has the median income in Jackson Heights grown or declined since 2000?

- How many veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars live in Staten Island? In the Bronx? On the Upper West Side?

- Which recent college graduates are ending up with jobs? How much do they make? How many are living at home with their parents?

- Has the number of people working in finance increased?

The answer is simple and surprising: "All the information you need was already released on Dec. 14 last year."

As you may recall, the census form you filled out last spring had just a few basic questions. So the data released on the basis of that can only include: number of people, dwelling owned with or without a mortgage or rented with or without cash rent, relationship to householder, sex, age, and race or races, including principal tribe or group, if Native-American, Asian or Pacific Islander. The other data -- indeed the data that in many ways is the most interesting and heavily used -- comes from the American Community Survey, or ACS, which is actually "the rest of the census" and was released in December.

The New Census

The census has been radically redesigned, and many census users have yet to catch up. Every census from 1940 through 2000 included a "short form" given to everyone to get a full enumeration of the population, as dictated by law. It asked only for very basic demographic information. The Census Bureau also administered a "long form" questionnaire that went to only a sample of persons or households and included a much larger set of social and demographic questions.

In 2000 the short form included only eight questions for the householder and six for every person living in the household. These were the same basic questions that would be asked in 2010 about sex, age, relationship to the householder, race and Hispanic status.

About one in six households received the "long form," which included some 53 questions. In addition to the basic questions in every census form, this survey also contained questions on a whole panoply of characteristics, including housing, moving in the last five years, employment, detailed income sources, military service, disability status, ancestry, place of birth and education.

Until 2010, the long form and short form were distributed in tandem, but then the government split them. Beginning in 2005, the Census Bureau began to collect data for the American Community Survey, which is very similar to the old long form. That survey gets responses from about 2 million households and residents of group quarters (prison, dormitory, institution) every year, and tracks the same sort of data that was produced by the long form sample. The survey takes place all year and interviews, where necessary, are conducted by permanent staff -- not the temporary workers who interview for decennial census.

The Census Bureau releases three sets of data each year from the community survey: the one-year, the three-year and the five-year files. The one-year file is released for areas of at least 65,000 in population, the three-year file for areas of at least 20,000 and the five-year file for all of the areas for which the long form was released (block-groups, tracts and higher). The census releases data only for certain locations with larger populations at one and three-year intervals. This is because, since the ACS is a sample, its reliability depends on sample size.

So on Dec. 14, 2010, the Census Bureau released the first five-year file from the American Community Survey, including all the data that used to be released from the census long form. This totaled 32,000 columns with 675,000 rows of data. These data are comparable to what was compiled from the 2000 Census and allow one to answer many questions at the neighborhood level, where data are needed beyond the few questions in the 2010 census.

Using the Data

There are some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form. The first five-year file includes data from 2005 through 2009, while the long form data were collected on the same date as the census. So now relatively current data are available and updated every year. This can be problematic for users -- for instance, the five-year file includes data from both before and after the financial crisis of 2007-08. On the other hand, the benefit is that even for small areas data never are more than a few years out of date. For larger areas the one-year file (from 2009) and the three-file (for 2007-2009) also are available. So we now have detailed social and economic data for a large sample available in a much more timely fashion every year.

As was the case with the long form, the community survey is a sample and so subject to sampling error. The confidence interval is often expressed as percent or number plus or minus another number that defines the interval. For instance: Bush 51, Gore 49 plus or minus 3 percent. The estimate should be between 54 percent Bush, 46 percent Gore to 48 percent Bush to 52 percent Gore. This would be accurate 90 percent, 95 percent or 99 percent of the time, depending upon the level chosen.

Unfortunately, the Census Bureau's approach to estimating the confidence interval is flawed in a number of ways and vastly overestimates the potential error in many instances. For example, if no one is found from a given group, say Native Americans or Italians or Colombians in a given tract in Brooklyn, the confidence interval is arbitrarily set to some number (often 75) and is noted in the data. This would mean, if it were taken literally, that the number of a group in a given tract could be plus or minus 75 and potentially create a negative population count. The Census Bureau now has a note that such absurdities should not be taken seriously, but this implies that the method for computing confidence intervals they used is wrong.

The bureau also used this flawed method in deciding whether to release tables for specific areas from the one-year and three-year files, something it calls "filtering." For example, for years, the bureau did not release foreign place of birth for people living in the Bronx or Staten Island. There are many, many examples of filtered data, which makes the data less useful. (A memo I wrote to the Census Bureau on the topic of their estimation of confidence intervals and it misuse, along with the agency's response is available here. )

At this point, the Census Bureau is mulling over what to do, but in the meantime one should realize that many of the reported confidence intervals are too large and can make it difficult to correctly estimate the confidence interval in cases where the user wants to combine data from individual neighborhoods to come up with statistics for larger areas.

A second issue with the American Community Survey is that its results at the county level are forced to conform to the system used by Census Bureau for yearly population estimates. This means that the actual number reported for a given location in the community survey may conflict with the census counts. This problem, of course, afflicts New York City, where the American Community Survey and census estimates are much higher -- about 250,000 people -- than the census counts. However, the proportions of a given group or category in the community survey should be correct, even if the totals are incorrect. Direct comparisons of totals in the survey files with those in the census files, though, can lead to anomalies.

In sum, despite some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form data, the survey is in most ways superior. Not only is the data released more often and in a more timely fashion, but the numbers may be more accurate since the survey is conducted by a permanent interview staff. So the next time you cannot find the data you want in the census report look for it in the American Community Survey.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Under a New Name, Census Data Stands Ready for Perusal

Photo by PaulSh

The 2010 census has been rolling out since February with New York state getting the first of its data on March 24 and more data releases during the summer. Yet, almost every day reporters, redistricting specialists and even other demographers ask when data to answer questions such as the following will be released:

- When will we know the number of immigrants in New York City and in various neighborhoods throughout the city?

- How many Hispanic citizens of voting age live in Washington Heights?

- Has the median income in Jackson Heights grown or declined since 2000?

- How many veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars live in Staten Island? In the Bronx? On the Upper West Side?

- Which recent college graduates are ending up with jobs? How much do they make? How many are living at home with their parents?

- Has the number of people working in finance increased?

The answer is simple and surprising: "All the information you need was already released on Dec. 14 last year."

As you may recall, the census form you filled out last spring had just a few basic questions. So the data released on the basis of that can only include: number of people, dwelling owned with or without a mortgage or rented with or without cash rent, relationship to householder, sex, age, and race or races, including principal tribe or group, if Native-American, Asian or Pacific Islander. The other data -- indeed the data that in many ways is the most interesting and heavily used -- comes from the American Community Survey, or ACS, which is actually "the rest of the census" and was released in December.

The New Census

The census has been radically redesigned, and many census users have yet to catch up. Every census from 1940 through 2000 included a "short form" given to everyone to get a full enumeration of the population, as dictated by law. It asked only for very basic demographic information. The Census Bureau also administered a "long form" questionnaire that went to only a sample of persons or households and included a much larger set of social and demographic questions.

In 2000 the short form included only eight questions for the householder and six for every person living in the household. These were the same basic questions that would be asked in 2010 about sex, age, relationship to the householder, race and Hispanic status.

About one in six households received the "long form," which included some 53 questions. In addition to the basic questions in every census form, this survey also contained questions on a whole panoply of characteristics, including housing, moving in the last five years, employment, detailed income sources, military service, disability status, ancestry, place of birth and education.

Until 2010, the long form and short form were distributed in tandem, but then the government split them. Beginning in 2005, the Census Bureau began to collect data for the American Community Survey, which is very similar to the old long form. That survey gets responses from about 2 million households and residents of group quarters (prison, dormitory, institution) every year, and tracks the same sort of data that was produced by the long form sample. The survey takes place all year and interviews, where necessary, are conducted by permanent staff -- not the temporary workers who interview for decennial census.

The Census Bureau releases three sets of data each year from the community survey: the one-year, the three-year and the five-year files. The one-year file is released for areas of at least 65,000 in population, the three-year file for areas of at least 20,000 and the five-year file for all of the areas for which the long form was released (block-groups, tracts and higher). The census releases data only for certain locations with larger populations at one and three-year intervals. This is because, since the ACS is a sample, its reliability depends on sample size.

So on Dec. 14, 2010, the Census Bureau released the first five-year file from the American Community Survey, including all the data that used to be released from the census long form. This totaled 32,000 columns with 675,000 rows of data. These data are comparable to what was compiled from the 2000 Census and allow one to answer many questions at the neighborhood level, where data are needed beyond the few questions in the 2010 census.

Using the Data

There are some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form. The first five-year file includes data from 2005 through 2009, while the long form data were collected on the same date as the census. So now relatively current data are available and updated every year. This can be problematic for users -- for instance, the five-year file includes data from both before and after the financial crisis of 2007-08. On the other hand, the benefit is that even for small areas data never are more than a few years out of date. For larger areas the one-year file (from 2009) and the three-file (for 2007-2009) also are available. So we now have detailed social and economic data for a large sample available in a much more timely fashion every year.

As was the case with the long form, the community survey is a sample and so subject to sampling error. The confidence interval is often expressed as percent or number plus or minus another number that defines the interval. For instance: Bush 51, Gore 49 plus or minus 3 percent. The estimate should be between 54 percent Bush, 46 percent Gore to 48 percent Bush to 52 percent Gore. This would be accurate 90 percent, 95 percent or 99 percent of the time, depending upon the level chosen.

Unfortunately, the Census Bureau's approach to estimating the confidence interval is flawed in a number of ways and vastly overestimates the potential error in many instances. For example, if no one is found from a given group, say Native Americans or Italians or Colombians in a given tract in Brooklyn, the confidence interval is arbitrarily set to some number (often 75) and is noted in the data. This would mean, if it were taken literally, that the number of a group in a given tract could be plus or minus 75 and potentially create a negative population count. The Census Bureau now has a note that such absurdities should not be taken seriously, but this implies that the method for computing confidence intervals they used is wrong.

The bureau also used this flawed method in deciding whether to release tables for specific areas from the one-year and three-year files, something it calls "filtering." For example, for years, the bureau did not release foreign place of birth for people living in the Bronx or Staten Island. There are many, many examples of filtered data, which makes the data less useful. (A memo I wrote to the Census Bureau on the topic of their estimation of confidence intervals and it misuse, along with the agency's response is available here. )

At this point, the Census Bureau is mulling over what to do, but in the meantime one should realize that many of the reported confidence intervals are too large and can make it difficult to correctly estimate the confidence interval in cases where the user wants to combine data from individual neighborhoods to come up with statistics for larger areas.

A second issue with the American Community Survey is that its results at the county level are forced to conform to the system used by Census Bureau for yearly population estimates. This means that the actual number reported for a given location in the community survey may conflict with the census counts. This problem, of course, afflicts New York City, where the American Community Survey and census estimates are much higher -- about 250,000 people -- than the census counts. However, the proportions of a given group or category in the community survey should be correct, even if the totals are incorrect. Direct comparisons of totals in the survey files with those in the census files, though, can lead to anomalies.

In sum, despite some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form data, the survey is in most ways superior. Not only is the data released more often and in a more timely fashion, but the numbers may be more accurate since the survey is conducted by a permanent interview staff. So the next time you cannot find the data you want in the census report look for it in the American Community Survey.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.