Experts Warn Of Foreclosure Crisis As Floodwaters' Toll Persists

NEW YORK — If the water that destroys much of your house comes up from below the structure, would you describe that as a flood? Grantley Hunt was mulling this question when his insurer balked at covering the damage caused by Superstorm Sandy over a year ago to his two-family house, which has an almost unobstructed view of Jamaica Bay in Queens.

The house is almost dead even with the bay. But Hunt was ready – he thought he was ready – when the water from the bay surged onto the streets of the Rockaways one year ago: He had encircled the house with sandbags.

“There was no way that water was coming into my house,” he recalled thinking. “So, when my son told me there was water in the basement, I said, ‘No, that’s not possible.’”

But the water was rising in the basement. “Oh Sandy, she fooled us,” Hunt said, his tone of voice changing as he started to talk about the hurricane as if she were an unannounced visitor. “She came from under the house!”

{pullquote}If the water that destroys much of your house comes up from below the structure, would you describe that as a flood?{/pullquote}

To Hunt, it didn’t matter how the water had gotten into the house — only that it did. But to his insurer, water that comes from underneath a house is technically not a flood, Hunt said, and his insurance company told him so when it refused to cover some of the damages. Up to now, Hunt has paid for all of the repairs himself – about $22,000 to rip out the dry wall that was soaked, replace appliances and electrical fixtures, flooring.

Like thousands of others whose lives were upended by the storm on Oct. 29, 2012, Hunt and his family may have escaped the storm surge, but a year later, the floodwaters’ toll on housing in New York City persists.

Forbearances on mortgages are set to expire, flood insurance premiums are expected to rise significantly and affect a larger number of homeowners due to new flood maps and the release of disaster recovery funds that could help homeowners has been slow.

All of the problems have compounded an already acute affordable housing crisis in the city.

“Hurricane Sandy exposed a lot of the deficiencies we have in affordable housing in New York City,” said Nick Charles, spokesman for the Local Initiatives Support Corporation of New York, which has overseen a mold remediation program in affected areas. “These are communities struggling with economic, social, and education issues. Hurricane Sandy comes in and exacerbates all of that.”

And other advocates warned that the expiring forbearances on mortgages — usually lasting 12 to 18 months — is a crisis in the making. “There’s a potential for a large foreclosure crisis – tens of thousands will be at risk of foreclosure,” said Matthew Hassett of the Center for New York City Neighborhoods.

SANDY’S IMPACT ON HOUSING

Sandy’s 13-foot storm surge reached nearly 76,000 residential buildings with nearly 300,000 housing units in the city’s five boroughs, according to a report by the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at New York University. Roughly 75 percent of the structures affected by the surge were single- and two- to four-family homes, but they made up only 30 percent of housing units affected by the storm. Most of the housing units affected were in larger residential buildings.

In some cases, entire homes were destroyed — for instance, more than 120 burned to the ground in Breezy Point where firefighters watched helplessly because they couldn’t pump water without electricity. Scores of New Yorkers living in residential buildings – Mitchell Lama cooperatives, public housing projects, rent stabilized and rent subsidized apartments – lost electricity, water and sewer services.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has spent $6.6 billion overall and almost $1 billion in New York to help homeowners pay for repairs, dislocated tenants pay rent, and to cover additional costs associated with the storm. The National Flood Insurance Program has paid nearly $3.4 billion in claims to 56,766 policyholders, the agency stated in a press release. Congress approved about $60 billion for storm relief overall.

The city itself allocated $108 million for repairs to New York City Housing Authority buildings – 402 of which were in the surge area, the agency said in an email, adding that those buildings are home to nearly 36,000 residents. The city demolished 275 buildings and issued almost 2,000 violations on buildings in the areas affected by the storm.

{pullquote}There’s a potential for a large foreclosure crisis – tens of thousands will be at risk of foreclosure," says one housing advocate.{/pullquote}

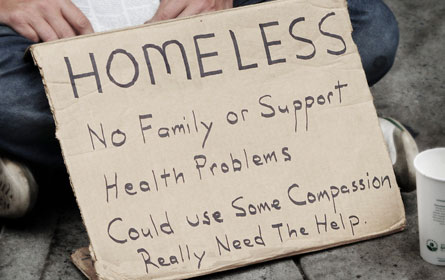

But all of that money has not been enough to shelter some people rendered homeless by the storm: Some evacuees continue to be displaced, with as many as 200 people still living in hotels paid for by the city.

Advocates say that number doesn’t encompass others who are living with relatives and renting apartments. “That’s really only a small fraction of the people who are displaced,” Hassett said.

The storm has put the city’s affordable housing issues atop the list of issues facing the city, advocates said – just in case the record number of homeless people in city shelters had not already.

Housing First!, a broad coalition of community, business, labor, civic, and religious organizations, issued a set of recommendations for the next mayor to turn concern into action.

"Looking forward, the next administration must not only redouble rebuilding efforts but must also partner with state and federal agencies to tackle the prohibitive insurance premiums that threaten to further damage our coastal communities through displacement and disinvestment,” said Rachel Fee of Housing First!

The city has estimated that the cost just to repair housing damaged by the storm will reach $3 billion.

SLOW REPAIRS, SLOW RECOVERY

The signs of Sandy remain visible in Far Rockaway. In Hunt’s house, two-by-fours are laid bare in the walls, where workers cut out paneling that was soaked. The work is on hold, however, because Hunt’s insurance company is balking at paying for the repairs. Aside from arguing over the definition of a flood, the company also insisted he did not send in a form years ago that would have continued his insurance; he said he sent it three times.

The Legal Aid Society has retained additional attorneys to help homeowners and tenants navigate the process of obtaining help from FEMA and insurance companies.

Since the storm, requests for legal aid have increased rapidly, according to Tashi Lhewa, one of the attorneys.

"The real problem is the lack of uniform guidelines by government agencies providing repair assistance" Lhewa said. "This leads to applicants being denied assistance on improper grounds and lacking access to an adequate appeal process."

As for homeowners’ efforts to obtain payments, he said the process is very time consuming.

"Claims have been taking time — a lot of time," he said. "And there's still a lot of people who need help."

The city launched a repair program, too, with FEMA called “NYC Rapid Repairs.” According to the city’s after-action report, “Rapid Repairs is the first program of its kind in the country and repaired approximately 11,500 homes with more than 20,000 units when it concluded in April 2013. At the peak of the program in January, Rapid Repairs completed work on more than 200 homes per day with labor from more than 2,300 skilled workers in a single day working under 10 prime contractors.”

In June, the city introduced “Build It Back,” another program to assist those impacted by the hurricane. The city extended the deadline to apply for the program to Oct. 31 and is urging people who were affected to apply. The city also reduced property tax payments for property owners in affected areas.

Hunt got some good news in August when his application for assistance from the Build It Back fund had been approved. But he has yet to see any of the promised money.

Not far from Hunt’s house in Far Rockaway, dumpsters line the streets and emergency heating systems are set up. The entrance to Breezy Point is guarded by a police checkpoint. Still, businesses are gradually reopening and life is getting back to normal, Hunt said, even though the local home improvement stores cannot seem to stock enough tiles, paneling and other building supplies.

“There has definitely been a psychological impact, lots of people won’t admit it, but it has affected them,” Hunt said. “Me, I’ve always been a little crazy.”

Hunt, a veteran of the Vietnam War, owns an almost identical two-family home next door and he had rented one floor of the house to a woman and her two children. The family evacuated in a hurry as the hurricane approached, leaving behind papers, family pictures and clothes.

Hunt recently gave a reporter a tour. A framed copy of the serenity prayer hung on a wall next to the Ten Commandments. Red Cross blankets scantly covered a couple sofas.

“I won’t throw it in the street – that’s a constructive eviction – and it wouldn’t be right,” he said, scanning the apartment recently. “A lot of tenants who’ve left, I don’t think they’ll ever come back.

De Blasio Pins Affordable Housing Hopes On Mandatory Inclusionary Zoning

Democratic mayoral hopeful Bill de Blasio has ambitious plans to reshape the inequalities in the real estate market by mandating developers build affordable housing.

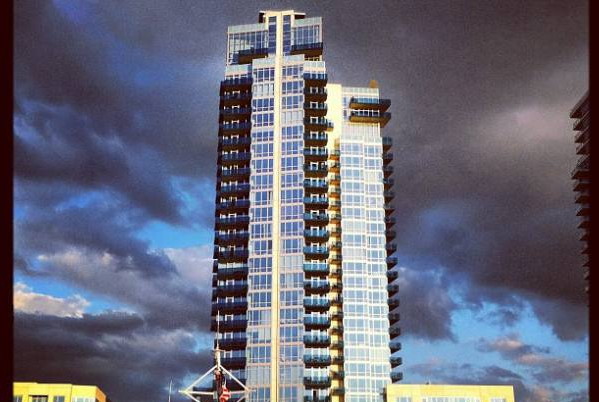

His plan to ensure that New York is no longer a “tale of two cities” is seeded in his affordable housing proposal known as mandatory inclusionary zoning. The policy would require developers to set aside a certain percentage of a building's units as permanent affordable apartments in exchange for increased building heights and tax breaks.

But an optional version of the policy, instituted by Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, has had a checkered history in New York City. Instead of stimulating the creation of more affordable housing, many developers have chosen to opt out — leaving policy experts skeptical of how a mandatory plan might work.

The Bloomberg administration’s optional zoning policy pairs well with its pro-development mentality. The policy gives developers the choice to participate in the program and receive perks like taller buildings or government subsidies to make up for the added development costs, or not participate at all.

Dozens of neighborhoods in Manhattan and Queens currently qualify for inclusionary zoning because big real estate developments are already underway in those areas (see map below). But only 13 percent of all new multi-family units are currently designated as affordable housing and more than a third of the city has been rezoned during Bloomberg’s tenure.

De Blasio’s hopes of breaking away from the Bloomberg mold by implementing mandatory inclusionary zoning is paramount to his campaign promises to revamp the affordable housing crisis in the city.

“I want to see much more aggressive policies in terms of how the city works with the real estate industry,” de Blasio said in a recent Ask Me Anything forum on the online aggregator Reddit. He said he plans to add an additional 200,000 affordable housing units in the next decade.

At a recent mayoral debate, Republican mayoral hopeful Joe Lhota said inclusionary zoning is unconstitutional.

"I don't believe in mandatory inclusionary zoning,” he said. “I don't believe that that will work. I think it's a violation of the constitution.”

Supporters of a mandatory program like City Councilman Brad Lander, who represents Brooklyn’s 39th district, said he thinks de Blasio has a shot at passing a citywide mandatory inclusionary zoning policy.

“It’s an important part of a much bigger plan motivated by addressing the tale of two cities and the affordability crisis,” Lander said. “He’s built a great campaign on the basis that the inequality in New York City is much too big.”

There are many potential problems with a mandatory program, according to The Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at New York University. Slowing of new development of market-rate housing could create a domino effect that would provide less affordable housing. Extra construction costs may also be passed on to market-rate tenants to make up for the losses incurred by creating affordable units.

Allowing developers to build taller to accommodate more people exacerbates the stress on public services and would require finite plans for more schools and better infrastructure.

Lander admitted there are pitfalls to the program, but his 33-page report makes a case for why the city could benefit from inclusionary zoning. He said it is important that the specifics be spelled out early on to ensure the program can be successful.

A comparable policy might be the city’s Inclusionary Housing Program, created in 1987, with a goal to incentivize developers to create affordable housing in market-rate developments. In its 26-year history, inclusionary housing has created a little more than 4,500 affordable units. Prior to the creation of the inclusionary zoning program in 2005, there were only 1,753 affordable housing units preserved or created.

Recent massive rezoning projects in the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Greenpoint, as well as in Manhattan’s Chelsea, have accounted for about 2,700 affordable units, or less than two percent of the total housing units built in the last eight years.

The Edge in Williamsburg is an inclusionary zoning fairytale. The zoning allows developers to build an additional 1.25 square feet for every square foot of affordable housing built. Of the 1,000 residential units at the Edge, 347 are affordable housing units (about 35 percent).

But the success of the program at the Edge is an exception. Even in areas with the strongest participation seen in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards and West Chelsea, there is only 18.6 percent of total development designated for affordable units — falling short of the 20 percent standard set by the program.

To avoid any legal concerns, de Blasio’s legislation will need to set clear-cut guidelines on the types of projects that will be mandated and what real estate developers will be required to build or pay for.

The Furman Center has already done part of de Blasio’s work of determining the hurdles he might face by creating a list of four specifics it thinks is necessary for a mandatory program to be successful. Those include the duration the units need to remain affordable; whether or not affordable housing requirements need to be met on or off site; whether developers can contribute to an affordable housing fund instead of building units; and what kind of density increases developers might be offered.

Inclusionary zoning is not the only option that incentivizes affordable housing. The 80/20 subsidy program gives developers tax-exempt bonds for their commitment to provide 20 percent of their units to low-income tenants in desirable city locations.

But that program also has shortcomings, at least one policy expert said.

“It is merely a zoning bonus,” said Josiah Madar, a research fellow at the Furman Center. “The developer provides affordable housing, the city lets them build bigger.”

Without a mandated inclusionary zoning, Lander said he fears affordable housing will disappear, especially in upscale neighborhoods.

“There’s not a silver bullet,” Lander said of the affordability crisis in New York.

Hurricane Sandy Buyouts Cause Storm Of Confusion, Worry From Politicians

ALBANY, N.Y. — The Fox Beach community of Staten island sits only a few blocks from the ocean on wetlands where tall reeds sprout across the landscape.

After the lives of three of its residents were lost during Hurricane Sandy and flooding destroyed a number of the small bungalows that make up the community, more than a few people who live in Fox Beach were ready to abandon the previously idyllic area.

A few days after the storm, a large group of local homeowners began meeting in the St. Charles School auditorium to discuss how to move forward and, when the prospect of government buyouts was brought up, the room was casually polled.

“Every person in that auditorium raised their hands,” said Joseph Tirone, who owns a home in Fox Beach and is the head of the Oakwood Beach Buyout Committee. He said the homeowners pressed officials for weeks, and eventually caught the attention of Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Cuomo announced on Feb. 25 that the Fox Beach community, which is a subsection of the larger Oakwood neighborhood, would be the testing ground of his general buyout program designed to return parts of the seashore to a natural state to create a storm buffer.

“There are some places that Mother Nature owns,” Cuomo told the audience at the College of Staten Island. “She may only come to visit every two years or three years or four years. But when she comes to visit, she reclaims the site.”

Weeks later, the buyout program is coming into focus for the Fox Beach community, but what will happen with the rest of storm-ravaged New York is still hazy. For months, homeowners have heard sometimes conflicting reports about the city’s plans, the state’s plans, as well as programs offered through the Federal Emergency Management Administration.

Lawmakers and community members say they have been told that the state under Cuomo will be unveiling a number of “enhanced areas” in the next few weeks where homeowners will be able to apply for a buyout worth 100 percent of their homes pre-storm value, with a five percent incentive if they move within their borough. The Cuomo administration has yet to confirm.

The state has allocated $171 million for buyouts, but officials estimate they could ultimately spend $400 million. Officials estimate 10,000 homes were severely damaged during Hurricane Sandy but expect only 10 to 15 percent of owners will take buyouts.

Meanwhile, the Bloomberg administration is not billing its efforts as a “buyout” program and will refer those looking for buyouts to the state.

Instead, the Bloomberg administration has also proposed a program that, if approved by U.S. Housing and Urban Development, will allow the city to buy damaged property at post-Sandy rates for redevelopment. The city’s program would appeal to property owners who aren’t part of the “enhanced areas” that would be covered under the state.

City officials say the properties would first be offered to homeowners who are staying and might want a larger yard, or to add to their property. It is unclear exactly how much the city plans to spend on this program.

Staten Island Borough President James Molinaro says his office has received 400 inquiries about home buyouts but is unsure how the programs offered by the city and state will help.

“Almost every block is a different story, every home has a different problem,” Molinaro said. “Some of these people are already underwater on their mortgage.”

Molinaro said it is unclear how those homeowners would benefit from a buyout if the money they get from the city or state does not cover their mortgage and they are left without a home.

He noted, however, that some banks in New Jersey have been working with homeowners to come to mutually beneficial solutions.

“I wouldn’t say there is an easy answer, but it is a problem we are aggressively addressing,” Tirone said. He said he expects banks to work with homeowners who are underwater on their loans and who want to take a buyout.

The press and local officials have underestimated the desire for buyouts, he said. “Elected officials are opposed to buyouts because they can’t visualize unbuilding,” said Trione, who feels city lawmakers have failed to do enough to ensure local homeowners are briefed on all their options.

Tirone recalls the story of a retiree who had tapped out his life savings to make repairs to his house following Sandy. “If he had been made aware that he could get the pre-storm price for his house and buy a new house that is not in a storm zone, he could have been set for life with his savings still intact,” Tirone said.

Molinaro is skeptical of the process so far, saying, “I have not seen any movement yet. The governor said he would buy homes at 100 percent of their value pre-Sandy but I have not seen any purchased yet.”

He emphasized that he has advocated for prioritizing buyouts to homeowners who have completely lost property and who have no mortgage so that they can quickly purchase a new home. Molinaro said he had warned residents that the buyout process can take years.

Randy Douglas, Town Supervisor of Jay, N.Y., knows firsthand that the government buyout process is anything but quick.

The Town of Jay suffered flooding in 1996 and 2008 from the AuSable River; then, in 2011, Hurricane Irene hit and the flooding was worse than ever. Roads, parks, youth facilities and sewer systems were wiped out along with homes. The town nearly lost its iconic covered bridge.

Some residents had simply had enough. Eighty homeowners out of the town’s estimated 2,500 residents were interested in a buyout program — one that paid 75 percent of pre-storm value.

Eighteen months later, residents are just now signing contracts with FEMA for the purchase of their properties. And the number of interested homeowners has dropped to 40.

”Some of them just couldn’t wait due to the length of time,” Douglas said. “A two-year process is way too long. I actually had people pass away during the process. It is just really sad.”

Douglas said he hopes that the concerns of victims of Irene and Lee have helped push officials to expedite the process for other homeowners. (The good news for Douglas: the state has included funds in its Sandy recovery plan to make sure homeowners who are bought out from Irene and Lee get a full 100 percent of their homes’ pre-storm value).

Despite having advocated for buyouts and having helped his residents push through the process, Douglas said there isn’t anything terribly positive about seeing residents decide it is time to pack it up.

“I’ve said since day one this isn’t a good thing,” he continued. “You lose your tax base, you lose families who have lived here for generations and you lose your identity. But with us, we couldn’t continue to put people in harm’s way.”

Douglas said he understands the reluctance of New York City officials to fully back buyouts. “Mayor Bloomberg has said he wants to build back stronger and seems to want to avoid buyouts. I’m not criticizing him because you don’t want to lose these people. You don’t want to give them up,” he said.

Sen. Joe Addabbo of Queens, who represents some of the neighborhoods hardest-hit by Sandy, including Breezy Point where dozens of homes went up in flames, said he has not seen a great deal of interest in buyouts. “We have a lot of longtime homeowners whose families have been here for generations who just want to rebuild. They aren’t looking to go somewhere else,” Addabbo said.

Addabbo acknowledged, though, that there has been confusion about buyouts. "Whenever there is a lack of information there is confusion," he said, "but I think it will end as we get more information on the two programs in the next two weeks.”

But Addabbo admits he doesn’t favor buyouts — in fact, he thinks they are a bad idea. “Personally, no, I don’t buy into the buyout program so to speak. It is a loss of revenue for the city, and the neighborhood behind that neighborhood loses their storm buffer, I think it causes other problems,” Addabbo said.

The state senator said not enough is being done to address flood mitigation. “What about seawalls, jetties, things that mitigate flood damage? Why aren’t we talking about that? Instead we are gonna buy 'em out? I don’t want them to leave,” he said. “As an elected official I want them to stay. Whether they have to elevate or [do] flood mitigation — whatever it takes.”

The Fox Beach community of Oakwood was labeled an “enhanced area” where the entire neighborhood was eligible for a buyout. Of the 183 households that were eligible for the state program, 180 have submitted applications according to state officials. Those homeowners are eligible for 100 percent of their homes pre-storm value.

Tirone said he thinks Cuomo’s motivations are completely apolitical. “I truly believe this plan has nothing to do with politics. The governor wants to create a natural buffer for those inland,” he said.

Meanwhile, plans for his neighborhood are developing apace. Homes have been appraised and, although he thinks Cuomo might be unhappy with him for such a bold prediction, he speculated that the process could be completed before the end of the year — a notable accomplishment given that the federal process can take three to five years at times.

But, for now, Tirone is still helping get the word out about the state program. “I get five to 10 calls a day from residents asking me to help them get bought out,” he said.

Image of destroyed home in Oakwood, Staten Island, by Paul Soulellis, used under Creative Commons license.

Families Displaced By Superstorm Sandy Are Running Out Of Time

NEW YORK — Since being displaced by Superstorm Sandy from their Far Rockaway apartment, Cherrell Manuel and her four children have lived in two different hotels.

At the Park Central Hotel near Times Square where the family is now, they are spread across three different rooms. Aware that the situation cannot last, Manuel says she gets up everyday at 6 a.m. to go apartment hunting. She doesn't get back until about 6:30 p.m.

“There's some apartments you go, the landlord say they’re ready. When we get there, the floors are all messed up, the ceiling is leaking, and they’re telling us, ‘Oh, sign the papers and I’ll fix it.’ Thats not fair to us," she said. "If we take an apartment like that and they don’t fix it then we’re stuck there for the year."

Six months after the storm, time is running out for Manuel and hundreds of other people displaced by the hurricane and living precariously in hotel rooms. The city-funded program that pays for the rooms is being terminated on Tuesday and with it will go the shred of stability that these families have come to rely upon.

Some elected officials and advocates are warning that many of the families could end up in the city's homeless shelter system unless a plan is put into place and are calling for a month-long extension to the city's program.

"While we agree that this program cannot continue indefinitely, we question whether the April 30 deadline is realistic for those remaining 196 households that do not qualify for the housing options currently available," wrote Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Councilwoman Annabel Palma in a letter sent to Department of Homeless Services Commissioner Seth Diamond on Friday following a hearing on the hotel program.

"It would be unfortunate for these households who have suffered such serious displacement as a result of Sandy to be left with the DHS shelter system as their only option," they continued.

They said the city’s decision does not make sense since other options are being discussed by policymakers, such as specialized housing vouchers.

Public Advocate Bill de Blasio sent a letter to Mayor Michael Bloomberg on Friday, calling the decision to end the program on April 30 without finding long-term housing solutions for the remaining households "a wrong-headed approach that lacks compassion and pragmatism."

"If it is going to set an arbitrary date for ending hotel stays, the city must better assess the individual needs of each household, and ensure that an accessible, long-term housing solution is reached for these impacted New York City families," he wrote in the letter.

Both Quinn and de Blasio are running for the Democratic nomination for mayor.

The impending termination of the hotel programs, and the fact that many families displaced by Sandy continue to be in limbo, is one of the legacies of the hurricane. Officials have said about 10,000 homes in the state were damaged or destroyed by the storm.

The federal government said on Friday that it had approved a $1.7 billion state plan for rebuilding. The city is receiving its own pool of funds, $1.8 billion, but its plan has not received approval. Both city and state officials have funds will be directed toward helping homeowners rebuild.

But the hotel program under the city may not be reimbursed by the federal government, and it’s unclear whether more money would be made available to house families in hotels.

DHS Commissioner Diamond testified for an hour Friday about the hotel program before the Council general welfare committee that Palma chairs. Council members questioned Diamond about a range of issues, including complaints about case managers and possible alternatives to the hotel program that may soon become an option. Dozens of people, including Sandy evacuees and housing advocates, crowded the hearing that was preceded by a rally on the City Hall steps.

As of Friday, Diamond said 488 households — about 1,000 people — were still in the hotel program, which has cost the city $40 million and involves some 50 hotels. Some 290 households will remain in hotels until the end of May because they have established clear transition plans, he said, with 43 households waiti ng for repairs to be completed and 249 going through the city's public housing application process or Section 8.

Of those households, however, he said 196 don't qualify for existing programs or rejected apartments that they were qualified to take.

Diamond said case managers continued to work with those remaining households to help identify more sustainable alternatives for them.

But during the hearing, Council members that represent some of the most storm-ravaged neighborhoods expressed skepticism that enough was being done to help those remaining families find more permanent housing solutions.

“I totally fail to believe that 71 individuals have rejected apartments from my district who have no place to go," Councilman Donovan Richards, of Queens, said to Diamond.

“I understand that you’re having difficulty with that and, as we said before, we continue to do what we can to work with those families," Diamond responded, but he later added: “We are disappointed too, as you are, that more of them didn’t take us up on the offers we’ve made.”

Richards also said that he had received complaints about how cases were being managed, and that Diamond was trying to make the process seem less challenging than the reality.

“I didn’t say there were no issues. I said I thought they’ve done an excellent job,” Diamond replied. “To the extent that there have had issues, we’ve addressed them.”

Councilwoman Gale Brewer, of Manhattan, asked Diamond during the hearing whether he thought 71 households who had been matched with apartments — but rejected them for whatever reason — might end up in the homeless shelter system, Diamond did not answer directly. "Nobody wants them in the shelter system," he said.

The existence of a separate hotel program run by the Federal Emergency Management Administration, has also caused some confusion, especially after it was extended for another month last week because the agency could not identify long-term housing solutions for them. Diamond said that, as of Friday, 114 evacuees were in the program. At its peak, Diamond said that the FEMA program was helping 1,070.

"We will have three times more people in our hotel system after the extension than FEMA has," Diamond said during the hearing. "While they’ve extended all along, they have reduced 90 percent of their population. We have been much fairer, much more compassionate, much more deliberate in the way we have handled the families."

After the hearing, Diamond emphasized to reporters that the "overwhelming number of people" who the city has helped have left the hotels without resources and not ended up in the homeless shelter system.

"We’ve worked for six month with these families. Very intensively," he told reporters after testifying. "We’ve had $15 million of case management resources invested in the program, and we've worked tirelessly with all the families in the program. Over 800 have been able to leave. I think that’s a tremendous success."

Manuel, 46, said facing eviction felt like the city was sending them a message that they had failed to meet their part of the bargain for accepting help.

“They’re acting like we’re not doing what we’re supposed to do," she said. "We’re up and about every day and there’s nothing more we can do. We can’t make landlords take us.”

She said she had scoured advertisements for rental apartments in newspapers, Craigslist and from Section 8, and has seen a little more than 40 apartments. But landlords will reject the family for a variety of reasons, including the ages of her children. She said they said the youngest is 7, the eldest 25.

“All we want is for the city to help us. We want them to stop feeling like we’re sitting in a hotel, relaxing like this is a vacation," Manuel said. “We need help. And we need people that are going to work with us. We don’t need people who don’t understand our situation.”

––––

Cristian Salazar contributed to this report. Image of children displaced by Sandy on the steps of City Hall during rally to call attention to the end of the hotel voucher program. Photo by William Alatriste, courtesy of the City Council.

A Harlem Voice For Tenants In Albany?

ALBANY, N.Y. — Assemblyman Keith Wright has resided at the same apartment at the storied Riverton Houses in Harlem for all of his 58 years. “Not many people can say that,” says the father of two.

Wright has played many roles at the Riverton Houses on 135th and Fifth Avenue — child, son, student, father, elected official.

But when Wright was announced as the new head of his chamber's powerful housing committee, it was his other role — as tenant advocate — that was seen as a boon to the city's vocal housing activists. Here was someone, they figured, who was deeply familiar with their plight and powerful enough, connected enough and friendly enough with the one man who really matters in Albany — Gov. Andrew Cuomo — to get things done.

Only a few days after his appointment, though, Wright's committee helped push through and ultimately pass a rent law package that gave tax breaks, known as J-51, to condo owners, which tenant advocates say help landlord to improve luxury apartments.

“What he did was really disgraceful," said Michael McKee of Tenants Political Action Committee, a group that works to elect pro-tenant legislators. "But I suppose he was taking directions from leadership."

Just days before, McKee had hailed Wright's appointment, saying: "He will be excellent."

Jaron Benjamin, the executive director of Metropolitan Council on Housing and a member of the Real Rent Reform Campaign, also said he was disappointed by the J-51 program vote. But he said he was "taking a wait-and-see approach" to Wright's appointment.

Wright admitted that his office "got some blowback" on the J-51 bill, but that it had to be passed. “I was named housing chair on a Friday and we had a very large bill that was somewhat controversial that had to be done on Monday," he said, but then added, "I know folks in the tenant movement were upset, they wanted that bill to be used as leverage but it was a bill for coops, condos and lofts and those type of people do live in New York City. We had to do this bill.”

The highly influential Assembly housing committee was once used as a lever of power by Vito Lopez, the disgraced Brooklyn political boss, who was removed from the spot after a sexual harassment scandal blew up last year. Lopez notoriously used his position as the housing committee chair to get friends and political allies perks, jobs, and apartments.

Before Wright was named head of the committee on housing by Speaker Sheldon Silver, he had steadily grown in stature over his 21 years in Albany. He served as the chair of the powerful labor committee and social services, as well as the black and Puerto Rican caucus. Last year, Gov. Andrew Cuomo personally picked Wright to co-chair the state Democratic Party.

He is also well-liked by his colleagues. Wright strolled through the ornate but basically empty Assembly chamber on a recent Tuesday afternoon, binders of legislation sit neatly on desks with empty seats. Wright’s colleagues were mostly gathered in conference but a few linger outside the chamber speaking to visiting school children or chatting on their phones. But they all take the time to stop and greet Wright. Wright returned their greetings in a deep, echoing rumble — the kind that could announce movie trailers or be the voice of god.

As long as his history in Albany might be, Wright’s been deeply involved in housing issues for significantly longer.

He traces it all back to Riverton Houses, which had also been called home by former Mayor David Dinkins and jazz great Billy Taylor.

“It was the first so-called development that was built for the quote unquote black middle class,” Wright explained during an interview this week at the back of the Assembly chamber. “When my father was away in World War II in Europe, my mother was in charge of trying to find an apartment and she went down to Stuyvesant Town and she was told that no blacks were allowed in Stuyvesant and I guess by eminent domain and Robert Moses and those folks, much picketing and outcry Metropolitan Life built Riverton, which is supposed to be the uptown equivalent of Stuyvesant Town.”

Life was good in Riverton for the young Wright. He recalled it as a melting pot of families from all walks of life. “There were folks who had money, folks who were middle income: teachers, police officers and folks that were on public assistance as well and it made for a fantastic community," he said. "I really had one of the best childhoods anyone could ever imagine.”

In the 1980s, Wright found the condition of his apartment building lacking and decided to do something about it. He became head of the tenant’s association and quickly became the go-to for his neighbors who had similar concerns about the building. “People would knock on door day and night looking for some sort of relief. They might want to clean up the common areas, need a new refrigerator, a new stove or need help dealing with the rights of succession. Some of them were late on rent.”

Wright had success and failures. Common areas were cleaned up, 40-year-old elevators were replaced, they even got some rent reductions, but they were unable to stop a major capital improvement request by the landlord. “These are the type of experiences that go into my formative years before I became the chair of housing-it has molded and shaped me to a certain extent,” Wright said.

Wright may have had sensations of deja vu in the days following his appointment as chair of the housing committee — with everyone wanting to talk to him about housing and this time it isn’t just tenants.

“What I find is that everybody wants to talk to me now from the titans of industry to Mrs. Smith pushing the shopping cart about housing," he said. "What I find with the titans of industry is that they try to dazzle you with their knowledge --using a lot of acronyms expressions that are customary to the housing industry but I got to get caught up to speed. I’ve been playing off my naivety asking a lot of ‘what do you mean? What do you mean?”

Forgive landlords, though, if they eye Wright with some skepticism — though he has been known to be open to both sides on the issue of housing. But Wright is clear about where his bias lies.

“Landlords are slick, they are business folks. When we first did vacancy decontrol stuff in 1997, no one had any idea," Wright said. "If you made more than $175,000 a year and the rent for your apartment was over $2,100 you were not eligible for rent control. At that time the only one who fit that criteria in my neighborhood was a guy named Percy Sutton" — referring to the black businessman who had also been Malcolm X's attorney — "No one made that kind of money. Of course, landlords get in there now and they say they are fixing them up and suddenly the rent is $2,100 and it is off the ranks now.”

Wright said at one point his landlord offered him $10,000 to move out of his apartment. “It was a sucker’s bet,” he said. “Landlords now actually hire private investigators to see how many people are living in apartments, how many days people in an apartment. Some landlords just ain't good people,” says Wright. “I’m not saying tenants are always right.”

Wright said he thinks that the Cuomo administration will be addressing a lot of concerns through the tenant protection unit Cuomo created in 2011.

Tenant advocates might laugh at the idea in some ways, since the unit has been seen as an underfunded and understaffed nod to tenants' groups. But Wright noted that Cuomo has put $4.8 million in his budget this year for the unit that is designed to help tenants who are being harassed, whose apartments are being wrongfully taken off the affordable housing ranks and to generally enforce landlord/tenant regulations.

Wright clearly has great respect for Cuomo and his knowledge of housing issues. “He can talk housing ad nauseam,” Wright said. “He can roll!”

Affordable housing has already become a focus of the mayoral race. Council Speaker Christine Quinn used her state of the city address on Monday to tout a package of legislation called the Permanent Affordability Act, which she said would be sponsored by Wright in the Assembly and Martin Golden in the Senate. The three-pronged measure that calls for building 40,000 units of affordable housing for the middle class, capping building owner’s taxes at a certain percentage of their rental income as long as they keeping units affordable even after they age out of affordability protections and extending 421-a tax exemptions to developers.

Wright said he has yet to see the legislation but says he did talk to Quinn this past Sunday. “She called me and asked if I would look at a bill. When the speaker of the house calls you at least have to look.”

Housing groups tend to favor the first part of the measure but feel the rest of the proposals are giveaways to landlords.

“We applaud Speaker Quinn for focusing on the need for both middle-class and affordable housing and the tax policies impacting them, and we look forward to reviewing the details and the legislation involve,” said Real Estate Board of New York president Steven Spinola in a statement.

Golden however said the 421a extension and the tax break proposal are in the works and won’t likely get a vote until the end of session.

Wright says he has a good relationship with Sen. Kathy Young who chairs the Senate housing committee and expects to have pleasant dealings with the other chamber.

Above all the things Wright’s colleagues say of him it is that he weighs issues, and takes the time to listen. “He listens and he is extremely thoughtful,” said Sen. John Sampson of Wright.

“I’m assuming the Assembly’s agenda isn’t going to change much. He hasn’t even had his first committee meeting and we haven’t talked to him yet,” says Frank Ricci of the Rent Stabilization Association of New York. “But he has always been willing to listen to both sides on the issues and you can’t ask for more than that from an elected official.

And Golden has similar praise. “I’ve worked well with him. We know each other well. I’ve found him to be a responsible individual, soft spoken but nobody should be fooled he is a very intelligent and articulate man who knows what has to get done. He is a very formidable man and I look forward to working with him.”

“I have a lot to learn,” says Wright, “but I am excited for this position.”

Who Will Live In Bloomberg's Micro-Apartments?

NEW YORK — Nicole Guzzardi's first experience living in Manhattan was, to say the least, cramped.

She had gotten herself a sub-300-square-foot studio in the Lower East Side, but space was so tight when her cousin came to spend the night he ended up relegated to bunking in the bathroom — with half of his body on the tile floor and half in the flat-bottomed shower.

“I had no room for anything. I obviously had no kitchen table. I had a desk but I barely ever sat in it because it was kitty-cornered and very uncomfortable,” said Guzzardi, who had just gotten into graduate school and needed a place where she could commute easily to New York University. “So I ate on my bed, I did my homework on my bed, I slept on my bed. … I had my small dog, and she just sat around all day in this little box. It was not fair to her.”

Claustraphobic living experiences like Guzzardi's are not unusual in one of the world's tightest, priciest residential real estate markets. And it's an experience that could become even more common after Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s “micro-unit” apartments start filling vacancies.

Last July, Bloomberg and other city officials announced adAPT NYC, the pilot program seeking new and affordable housing models for a growing number of one- or two-person households.

Thirty-three developers submitted proposals for the units, which are expected to be between 275 and 300 square feet — about 100 square feet smaller than what is currently permitted under city zoning regulations. (Guzzardi's Lower East Side apartment building was constructed before a 1901 law regulating the minimum square footage.)

The winning proposal for the adApt NYC program could be announced as early as today.

The Bloomberg administration wants the developer to build as many as 80 micro-units at 335 E. 27 St., in Manhattan. The units are intended to be affordable housing for one- or two-person households, which the latest census data found to be a rising demographic in the city. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there are 1.8 million one- and two-person households, but only one million studios and one-bedroom apartments.

But some have called the micro-units tenements for the 21st century, though at an expected $2,000 a month and a 10-by-30-foot layout, they would certainly not be housing large, low-income families. They also would likely be out of the price range of most people within the target demographic — single New Yorkers. According to the city comptroller's office, 81.2 percent of single tax filers in the city made under $75,000 in 2009, with the largest group — 36.6 percent – earning under $20,000.

“It doesn’t really fit the need for families and for growing a family or staying long term in the city,” said Matthew Dunbar, the advocacy and community relations manager for HabitatNYC, the local branch of Habitat for Humanity. “Anybody who wants to expand their families would not be able to use a micro unit to be able to do that.”

City officials said the micro-units will help to meet the changing needs of New Yorkers and are “critical to the city’s future economic success.”

“We hope that this pilot will turn out really well,” said Catie Marshall, a spokeswoman for the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. She added that the city hopes and expects to develop micro-units across the city.

Policymakers in other U.S. cities are also considering tiny apartments to deal with the scarcity of affordable housing.

In San Francisco, lawmakers have approved that city’s smallest apartments, allowing the construction of 220-square-foot units, expected to range in rent from $1,200 to $1,500, according to the Los Angeles Times. In Boston, one firm displayed a 300 square-foot apartment in the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, as a housing option submission to a research program launched by Mayor Thomas M. Menino in 2004 aimed at finding a way to better serve the one-in-three Bostonians between the ages of 20 and 34. They are expected to cost about $1,500 a month.

In China, Japan and Paris, micro-units, sometimes no larger than a compact car parking spot, have also become increasingly popular.

THE SIZE OF A MICRO-UNIT

To understand the size of a micro-unit, try picturing half of a No. 6 train car, furnished. Imagine your bed — likely a sofa bed because of spatial constraints — in the middle. That’s the living room. Replace the poles and seats with a kitchen sink and a bathroom, complete with a tub. Now add in clothes, books, a computer, maybe a dresser — feeling crowded?

But what people might not get in terms of space they get in location.

“If they want to live in Manhattan, they have to forego a lot of things, and space is one of them,” said Zaida Farnham, an agent with Prudential Douglas Elliman.

Another real estate expert, Jeff Rothstein, vice president in charge of rentals and sales at Prudential Douglas Elliman, said that, for most young people, an apartment is “just a bed.”

“Most young professionals are never in their apartment anyway,” he added.

The New York micro-unit’s expected rent is 40 percent higher than the median New York City household can sustain without infringing on basic necessities. The Census found that city residents’ per capita income is $30,398, and that the median household has an income of $50,285 and is made up of two to three people. That means, for an average household making $50,000 per year, affordable rent should not exceed $1,250 per month.

Although the developer will have the final say on the cost of rent, the $2,000 per month cost undercuts the average market price of a downtown Manhattan studio, which has grown to $2,669, according to September’s market report from Prudential Douglas Elliman. One bedrooms go for $3,528.

Rothstein said he expects the micro-units to be filled by young professionals and graduating college students, like Guzzardi, looking to stay in the city. But, according to a salary survey published by the National Association of College and Employers, the average starting salary for college graduates is $44,259. Affordable rent for that income is about $1,100 a month.

That salary looks about average when compared to a report issued by the city Comptroller in May that showed 68.3 percent of New York City tax filers earned less than $50,000 in 2009.

A different report issued by the Comptroller in September found that half the households in New York City couldn’t afford their rent. Forty-nine percent of New York City households pay more than 30 percent of their income on rent, and of that, 30 percent are paying more than half of their income on rent.

Rothstein said the micro-unit project might be part of the solution to the affordability problem.

“I think that it’s something proactive; that the mayor is taking responsibility to keep young professionals in Manhattan,” he said. “The average one-bedroom is, what, $3,500? So, how can a young professional just starting a career in Manhattan afford that? Unless they get subsidized by a parent or they work another job.”

Joseph Gabriel, project manager for Blesso Properties — which submitted a micro-unit plan to adAPT NYC — said he expects micro-units to be a success, and cited the response of a recently opened apartment building in Chelsea as evidence. He said eight of the nine units were 450 square-foot studios, costing as much as $3,200 a month at the higher end. Gabriel said his firm received favorable responses after renting most, if not all, the building’s units shortly after putting them on the market.

Gabriel said he hopes to win Bloomberg’s competition, but added that he expects to implement the housing model around the city regardless of whether the Blesso Properties’ proposal is chosen.

"We’re hopeful that any zone changes or code changes do allow for a more flexible and more progressive type of development than has historically been possible in New York," he said.

BIG CITY LIVING IN TINY SPACES

Despite the growing cost of rent, shrinking salaries and lack of job opportunities, people continue to move to Manhattan and other expensive neighborhoods in the outer boroughs. Renters are willing to cut back spending elsewhere to call a piece of the city their own.

“Even though it’s the size of a shoe box, it’s their own apartment,” Rothstein said. “They don’t have a roommate situation where somebody ate their yogurt.”

Guzzardi moved to Manhattan in 2011 to pursue a graduate degree in journalism at New York University. Like many young adults, she wanted to live on her own.

As a full-time student balancing school, social life and work as a blogger for the Huffington Post, it was unlikely she could spend a considerable amount of time at her East 11th Street apartment.

Guzzardi originally set a $1,500 budget for rent, with the money coming from financial aid for school and money from her father, but upped it to $1,600 after initial apartment hunts came up dry. When she found the studio, perched atop Tu-Lu’s Bakery on 11th Street in the Lower East Side, she settled for $1,750.

“It was wicked nice, though,” she recounted. “Everything was redone. It had marble countertops and a pretty nice shower and a little balcony. I was like, whatever, I can deal with living in this amount of space. It’ll be fine.”

That optimism proved to be short-lived as the days wore on and the lack of space became more of an issue; she left after her lease was up. She now lives with a roommate in Gramercy.

Guzzardi said she wouldn’t choose to live in the same cramped apartment outside of her budget again, but she doesn’t regret her choice either. “If this is going to be my only [New York City] experience, I’m glad it was in Manhattan.”

___

Image courtesy of the mayor's office. Mayor Michael Bloomberg and HPD Commissioner Mathew M. Wambua at launch of adAPT NYC (July 2012).

Council Wants To Force Landlords To Fix 'Underlying Conditions'

NEW YORK – After moving from a homeless shelter to an apartment in the South Bronx, Kymm Moore said he found his new home plagued with mice, mold and multiple water leaks.

He said he couldn't get the landlord to repair anything, either, even after he called to complain to the city several times and inspectors issued violations. “It was very frustrating,” Moore said on Wednesday. “A lot of my stuff was going to get ruined.” He said he ended up paying $7,000 out of his own pocket for repairs before moving out.

A new bill approved by the City Council at Wednesday's stated meeting aims to give housing officials more enforcement tools to crack down on landlords who fail to fix underlying conditions that have been the cause of multiple housing code violations — before tenants like Moore are forced to move out.

The bill would allow the city's housing inspectors to make the repairs themselves, if necessary, and let them recoup the cost from the landlord.

Council Speaker Christine Quinn said in remarks before the Council vote that the legislation would empower the city’s housing inspectors to target “the root cause of repeat housing violations.” Mayor Michael Bloomberg is expected to sign the bill into law.

Councilwoman Gale Brewer, who sponsored the bill, said that Moore's case is representative of those that she sees. "Right now, [the landlord] kind of gets away with a fine here, a fine there," she said. Inspectors "have to keep going back and back."

An official with the city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development said that the building where Moore lived had a large number of open violations and had been identified for proactive intervention by the agency. The building is not expected to be a prime candidate under the new law.

The building was foreclosed in 2012, and the debt was bought up by a private equity firm.

Moore's former landlord, Asher Neuman, said he did not recall Moore as a tenant. But he disagreed that repairs weren't made. "Any time someone came to me with a complaint they were always repaired,” he said.

WHY THE POLICY MATTERS

The legislation could potentially save city taxpayers money. The Daily News reported that the city spent $26.3 million on repair jobs dealing with repeat violations.

Quinn said the exact savings to taxpayers may not be known for some time, but that “it could be quite significant.”

Besides cutting down the number of times that inspectors have to go out to a site for the same violations, repairing underlying conditions before problems get worse also may help to preserve the quality of the city’s limited affordable housing stock, she said.

“Certainly preserving it, making the housing livable, has much long-term savings,” she said.

WHAT THE POLICY DOES

Intro. 0967-2012 is a local law that would amend the administrative code of the city of New York and was discussed in the Committee on Housing and Buildings.

It would grant inspectors for the HPD the authority to issue orders to building owners requiring them to correct any underlying conditions that are causing repeat violations of any city or state housing code. Currently, the HPD is allowed to issue violations for “observed damage,” but not unseen root causes of that damage.

A building owner will have four months (with a possible two month extension) to fix the underlying condition and submit documentation to the HPD from a licensed plumber, registered architect, or professional engineer verifying that they have done so. The HPD will then re-evaluate the site and, if satisfied, rescind the violation.

Failure to comply with the HPD’s order could result in a fine of $1,000 per dwelling unit with a minimum of $5,000 per building.

The HPD will be charged with establishing the criteria that will bring about an order to fix an underlying condition. Vito Mustaciuolo, HPD Deputy Commissioner of Enforcement and Neighborhood Services, told the Committee on Housing and Buildings during his testimony that this process could take up to six months.

After this criteria is determined, Mustaciuolo estimated that during the first year of the legislation, 100 buildings with a history of multiple violations specifically related to water leakage and mold will be inspected by the HPD to check for underlying conditions.

Mustaciuolo emphasized that these buildings will not be ones that are under the authority of the Alternative Enforcement Program, which already repairs underlying conditions. Established in 2007, each year the AEP identifies the city’s 200 most distressed buildings and, throughout the year, works with their owners to address structural problems. The HPD will use the AEP workforce, however, in inspecting the buildings identified by this new legislation as possibly having underlying conditions that need correction.

Brewer said the new legislation came about when she realized there was an entire subset of buildings that did not fall under the AEP but that had chronic, underlying conditions that were going unrepaired. “That’s when I decided to do it,” she said.

WHO DID WHAT?

The bill was first proposed by Speaker Christine Quinn in her February 2012 State of the City address. Brewer, who represents the Upper West Side and Hell’s Kitchen in Manhattan, sponsored it in the Council.

The bill has been backed by the HPD "as a means of ensuring residential units in New York City are well maintained and habitable,” Mustaciuolo said. “We are hopeful that this new initiative will better focus enforcement resources on properties which fail to treat repairs in a serious and holistic way.”

Tenants groups and housing advocate organizations, such as the Association For Neighborhood and Housing Development, Inc., and Tenants & Neighbors, also support the legislation.

Kerri White, director of organizing and policy at the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board, which also supports the bill, said that without the new law landlords can patch over problems without actually fixing them. Tenants, she said, “go through this cycle of patch repairs.”

She said this was a keen problem with mold. “The landlord will come and paint over the mold and say the problem is fixed,” she said.

A spokesman for the Rent Stabilization Association, which represents New York City landlords, said the group had some concerns about the bill.

“We’re going to take a wait and see attitude,” said Frank Ricci, director of governmental affairs for the RSA, in an interview on Monday. “We have some reservations about the bill, especially because of the subjective nature of inspectors determining what is or is not an underlying condition.”

This aspect of the bill was also brought up by Councilman Erik Dilan, chair of the Committee on Housing and Buildings, at the bill’s hearing on Dec. 13, 2012.

“I think the bill is intentionally very broad in scope” — he said while questioning Mustaciuolo — “but it sounds, by your testimony, you have a limited scope which you hope to identify during the rulemaking process.”

NEXT STEPS

The bill, which passed unanimously during the Council’s stated meeting Wednesday, goes to the mayor’s desk for his signature next. If it becomes law, there will be a rulemaking process to define the policy.

REFERENCE

View Intro 0967-2012 legislation text and details

View Local Law 29 for the Year 2007, which established the Alternative Enforcement Program

View Urban Homesteading Assistance Board’s blog post about 836 Faile Street

___

Additional reporting by Cristian Salazar.

This version was updated on Jan. 11, 2013. The original post erroneously reported that Councilwoman Gale Brewer represents the Upper East Side. She actually represents the Upper West Side.

After losing rent subsidy, disabled NYers face eviction

NEW YORK – Judith Patel, a disabled senior who was homeless for years until she got her apartment in 2009, is going to housing court this week for the third time in as many months. If she loses her case, she could be evicted.

Patel is one of thousands of New Yorkers – including hundreds who are disabled – struggling to pay bills and stay in their homes since a key rent subsidy, known as the Advantage program, was defunded last year. The program also provided help specifically for disabled New Yorkers like Patel through Fixed Income Advantage.

Patel said that without any kind of rent subsidy, she would be unable to continue paying for her Bronx apartment.

“Here are the cold, hard facts: I get $785 a month as of last January, and my rent is $936 a month,” said Patel, 62, during a recent interview.

The City Council’s general welfare committee plans to hold a meeting on June 6 to discuss how to help people who were once on the Advantage program. The state Court of Appeals is also expected to hear a lawsuit this week that would force the city to continue paying the subsidy.

But advocates for the homeless and people with disabilities fear the courts and city officials won’t act in time to prevent Patel and others like her from being evicted and finding themselves back in homeless shelters or on the streets.

“We have no idea when the court will make its decision,” said Pat Bath, a spokeswoman for the Legal Aid Society, which brought the lawsuit against the city.

Patel, who has diabetes and hypertension, became homeless in 2007. With an avalanche of medical bills compounded by a lack of health insurance, she couldn’t make ends meet. During a stay at a homeless shelter, she developed numbness and pain in her feet and was diagnosed with neuropathy.

One of the places she lived before moving into her apartment was the Valley Lodge shelter on the Upper West Side, one of two homeless shelters in the city for people with disabilities.

Since the rent subsidy was cut, the shelter has been working with the recently formed Coalition to Save the Fixed Income Advantage to lobby the state and city to develop a new subsidy.

Karen Jorgensen, the shelter’s director, said she worries some previous residents of Valley Lodge who, like Patel, moved out with the help of the now defunct Advantage subsidy, will be forced to return to the shelter.

“We never thought that they would be left dangling,” she said.

A Critical Rent Subsidy

The Advantage program was started in 2007 as a rent subsidy funded jointly by the city and state. New Yorkers could apply for the fixed income version of the program if they also received Supplemental Security Income, a federal fixed income program for people unable to work because of their age or disabilities. The two-year subsidy paid 40 percent of a recipient’s rent in the first year of the program, and 30 percent in the second year.

The state defunded its share of the Advantage program last year – including the fixed income version – when Governor Andrew Cuomo decided not to include funding for the program in his annual executive budget, citing the need for the state to tighten its budget.

The governor’s press office didn’t return several requests for comment for this story.

But Cuomo spokesman Josh Vlasto released a statement when the cuts were made public last year, defending the state’s position. “New York City has the funds to support the continuation of this program if it so chooses,” he said.

But when the state withdrew the funding, the city announced it would discontinue the Advantage program subsidy immediately, saying it did not have the money to continue it on its own. The city estimated the program would cost $140 million a year; the state disputed that, saying it would cost $103 million.

The Legal Aid Society sued the city and won a court order forcing it to continue paying the subsidy for the next nine months until an appellate court reversed the decision in February, effectively terminating the subsidy. The society appealed. The appellate court could make the city start paying the subsidy again until the two-year time limit on the program is up.

Since the end of the Advantage program, the city’s Department of Homeless Services has been emphasizing a “work-first” approach focused on helping families who are homeless find employment. Asked about programs that might aid people like Patel, DHS said it offered many eviction prevention options.

“We must reject the misconception that a rental subsidy is the only ticket out of shelters,” Department of Homeless Services Commissioner Seth Diamond said at a recent conference on homelessness in the city. “Most families can work and want to work.”

This focus on families and employment means that, in order to be eligible for many of the city’s eviction prevention programs, a person has to be working, have children under the age of 18 or have some means to pay rent in the future. Many of the disabled New Yorkers who were on the Fixed Income Advantage program don’t qualify for these programs and have nowhere to turn to for help.

A month after the city stopped paying the Fixed Income Advantage subsidy, Patel was in housing court facing eviction proceedings along with several other tenants in her building who receive the same benefits. Her leasing agent has twice adjourned their case to give the tenants time to resolve the situation out of court. But since Patel and her fellow tenants had nowhere to go for help, they found themselves back in housing court this week confronted with another round of eviction proceedings.

Advocates described the situation for the city's disabled as dire. “We are in the face of a catastrophic housing crisis for the disabled,” said Susan Dooha, the executive director of the Center for Independence of the Disabled, New York, one of the groups behind the Coalition to Save the Fixed Income Advantage.

Dooha said that 41 percent of New Yorkers living with disabilities face difficulties paying their rent. More than 806,000 New Yorkers are living with disabilities, according to the 2010 U.S. Census. That number, Dooha said, is likely to grow in the near future. The city projects that the number of New Yorkers over the age of 65 will increase from more than 937,000 last year to more than 1.35 million in 2030.

“As age increases, the prevalence of disabilities go up as well,” Dooha said.

Those with disabilities who get evicted often wind up either in shelters, or in supportive housing and nursing homes that are more restrictive than they need, she said. Supportive housing and shelter stays also cost the taxpayer much more than rent subsidies.

“I don’t need supportive housing. They’d be paying for services I don’t need,” Patel said.

But the city receives federal and state funds for homeless shelters. The city would have to pay any rent subsidies on its own, since the state changed its executive budget last year to prohibit any future rent subsidies to residents of New York City.

Waiting for Help

The Coalition to Save the Fixed Income Advantage has been lobbying since the state defunded the program last year to get a rent subsidy to replace it, but it is unlikely that any subsidy will be made available in time to help those disabled New Yorkers like Patel who are already in housing court.

The Department of Homeless Services could use some of the funding that it receives from the City Council to provide a short-term subsidy for disabled New Yorkers facing imminent eviction, said Eduardo Sanchez, a social worker at the Valley Lodge shelter who is involved with the coalition’s lobbying efforts.

But he said the city is unlikely to support any short-term subsidies without state aid.

“The sad reality is that with the end of the Advantage program, a great number of formerly homeless individuals are in dire straits,” Councilwoman Annabel Palma, who chairs the general welfare committee, said in a statement. “Those individuals on a fixed income will be in a particularly difficult position with few, if any, options to fill the void left by the elimination of the voucher payments.”

The Council is in negotiations with the mayor’s office about ways to keep people out of shelters, said Council spokeswoman Robin Levine. She would not comment on any specific proposals being discussed.

Meanwhile, many who had come to depend on the Fixed Income Advantage program are waiting for help that may never come.

“It’s really not fair. We have no other programs or alternatives,” said Sharon Franklin, 55, another formerly homeless disabled New Yorker who got off the streets with the help of the Advantage subsidy. “We’re all about to get thrown out.”

Like Patel, Franklin has also been in housing court since she lost the subsidy. She has until June 23 to pay her rent arrears or she will be evicted. She is hoping to receive a grant from the city’s Human Resources Administration by then to pay her back rent. But she is afraid that if she doesn’t get the grant she will have to go back to a homeless shelter.

“I feel like I’m reliving my past. It’s bringing up a lot of bad memories,” Franklin said.

NY tenant groups gear up for another round

Gov. Andrew Cuomo touted it as “the greatest strengthening of rent laws in decades” when the state Legislature approved a package of bills last year that renewed the city’s rent control laws until 2015. But the most optimistic housing advocates would only call it a draw in their battle with real estate interests.

Tenants Political Action Committee and other tenant advocacy groups wanted more -- they wanted the state to limit landlords’ abilities to claim that they made costly repairs to apartments, thereby pricing them out of rent regulation. They wanted tougher enforcement to make sure claimed improvements to apartments were actually made. And they wanted the 2011 increases to keep up with inflation. But they didn’t get any of it.

While still smarting from last year's brawl with real estate interests, advocates for tenants have renewed their push for rent law reform this year, arguing that current policies are continuing to decimate the ranks of rent-controlled apartments and making it harder for low-income families to live in the city.

Last Wednesday night, several of the groups, including the Real Rent Reform Campaign -- made up of organized tenants, labor organizations and community groups that advocate for “progressive” pro-tenant legislation -- held a well-attended town hall meeting in Brooklyn (they estimated the crowd at about 200 attendees) while the board of the influential Tenants PAC met separately and decided on endorsements for state legislative races.

The groups hope that, with the entire state Legislature up for re-election this November, they can help get candidates into office that are more willing to pass legislation they favor.

Meanwhile, the groups are sensing a deal between the Assembly and Senate might be possible because of the sunset of the J51 tax abatement that gives developers tax breaks to renovate apartment buildings as long as they provide low income housing.

The idea goes something like this -- the real estate lobby wants the tax renewed and, while Senate Republicans want to give it to them, the Assembly Democrats won’t pass it unless pro-tenant sweeteners are included.

Meanwhile, the piece of legislation that could have the greatest impact on rent that is being backed by advocates would change the requirements for serving on the Rent Guidelines Board -- the group that sets the rates for rent-controlled apartments and give the City Council approval over the Mayor’s appointments to the body. The board has raised rates by around 3 percent each year for the past 40 years. Its deliberative process is secret.

Putting the mayor’s picks in the hands of the Council would be a major loss of power for the mayor. Currently, the nine-member board is made up of two appointees to represent owners; two tenant representatives; and five members representing the general public.

Jack Freund, vice president of the Rent Stabilization Association, slammed the bill.

“We think it’s a catastrophic idea. It would be the death knell for private rental housing in New York. There would be zero increases forever. I certainly hope the bill doesn’t go anywhere,” he said.

Stefan Ringel, spokesman for City Councilman Jumaane Williams, said his boss thinks the current makeup of the RGB “fails to reflect the interests of real people. It seems like no matter what the economic condition is, the rent goes up.”

State Sen. Daniel Squadron and Assemblyman Brian Kavanagh are sponsoring the bill. The City Council is expected to pass a resolution in support of the legislation, and Council Speaker Christine Quinn has attended rallies and spoke out against the RGB. At a rally to support the legislation held in front of City Hall on April 16, Quinn compared the RGB to a "kangaroo court" because its decisions seemed to be preordained.

NYC Council Proposed Res. 1329-A

Missed Opportunity

Michael McKee, treasurer of Tenants PAC, said the 2011 increases were “bare bones” and didn’t even keep up with inflation.

The deal raised the level at which apartments can be removed from rent regulation from $2,000 to $2,500, and the income threshold for rent-control apartment eligibility from $175,00 to $200,000. But the $2,000 -- set in 1997 -- should now be somewhere around $3,100, tenant advocates argued.

In June 2011, McKee had practically lived in the capital for weeks with fellow tenant activists by his side, chanting, cajoling, arguing and pleading with legislators and staffers for rent laws that would end loopholes that allow landlords to take rent-regulated apartments off the roles.

The Tenants PAC had watched in horror for the past two years while the Senate Democratic majority they had helped elect ignored and buried their legislation.

Former state-Sen. Pedro Espada was not shy about his ugly relationship with housing advocates. Espada, recently convicted of stealing tens of thousands of dollars from the network of Bronx clinics he helped start, was repeatedly accused of bottling up housing bills. In multiple interviews with the Gazette, he said he disdained tenant advocates who he insisted did not care about his constituents’ interests. In 2010, the Tenant’s PAC made a commitment to defeat him and helped elect Gustavo Rivera to replace Espada.

Gov. Cuomo had never made it clear in the lead-up to the legislative showdown what qualified as tougher rent laws -- only that he wanted them.

The new laws were scheduled to sunset in 2015 -- meaning that advocates wouldn’t have the benefit of the pressure created by an evaporating law to lobby legislators. But, on Dec 31, 2011, the J51 Rent Abatement expired, and tenants’ advocates saw opportunity.

Another Bite

In April, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver held a news conference focusing on tenant legislation. The to-do list read something like this: close the preferential rent loophole; make rent increases for major capital improvements temporary; reduce the vacancy bonus; limit a building owner's ability to recover a rent-regulated apartment for personal use; and reforming the Rent Guidelines Board.

That was only the start of an ambitious list -- ambitious because Senate Republicans have almost religiously sided with real estate groups that donate generously to their party’s candidates; ambitious because the laws are not set to sunset and be vigorously reviewed until 2015; and ambitious because real estate interests have generally opposed these sorts of changes.

“Last year we were able to ensure the rent regulations were renewed and strengthened,” Kavanagh said. “This year, we hope to see some modest improvements to the system.”

Specifically, his bill would change the requirements to serve on the RGB.

Current requirements dictate an appointee must have a background in financing, economics or housing. But Kavanagh’s bill would add allow appointees to have backgrounds in social sciences, urban planning, public service and philanthropy.

The assemblyman said he thinks the current requirements “don’t reflect all of the aspects” that need to be considered by a board that is tasked with setting guidelines for rent-controlled housing.

“If the bill passed, it would make a significant improvement in how the guideline board is structured,” said McKee.

No deal has been proposed, and tenants’ advocates like McKee said the real estate industry has not been making much of a fuss over J51. “In a non-sunset year it is really hard to get the Legislature to do anything on rent,” said McKee.