Bridging New York's Transit Gap

Photo (cc) Brooklyn-Queens Greenways Guide

New York City should examine successful Bus Rapid Transit expansions in

large cities such as Taipei and Bogotá.

large cities such as Taipei and Bogotá.

While U.S. cities such as San Diego and Las Vegas have recently rolled out bus rapid transit, New York can learn more from the experiences of cities in the developing world cities, such as Curitiba, Brazil, and Bogotá, Colombia. Like the emerging megacities of the south, New York urgently needs better transportation for a dense population that already embraces mass transit - and a solution that can be implemented quickly and cost-effectively.

In other US cities, transportation wonks debate whether bus rapid transit, or BRT, a series of measures to move buses faster and reduce waits, can make buses sufficiently attractive to attract upscale riders and/or spur transit-oriented development. In much of the country, what transit there is consists of conventional bus systems that are underfunded, often ill-managed and, as a result, used only by people too poor, too old or too disabled to drive. Planners trying to popularize transit in car-dominated cities fret over whether BRT has enough cachet to overcome the stigma attached to buses and the people who ride them.

In New York, though, our challenge isn't attracting enough riders to make transit viable - it's providing enough transit to handle what is already an overflow customer base, not to mention the million new riders that PlaNYC anticipates. The epic saga of the Second Avenue subway illustrates a hard truth - building new subway lines in New York City is too slow and costly to address a meaningful share of our need.

Even if money were no problem, few of the major rail projects on the boards would do much to make our commutes faster or less crowded. The extension of the Number 7 train extension is typical - it's about enabling development on the far West Side, not about improving the lives of the people packed onto that train today.

Transit-starved in a Transit-rich City

Photo courtesy of Pratt Center for Community Developmentt

A portion of a map for lower-income commuters. For full illustration, click here

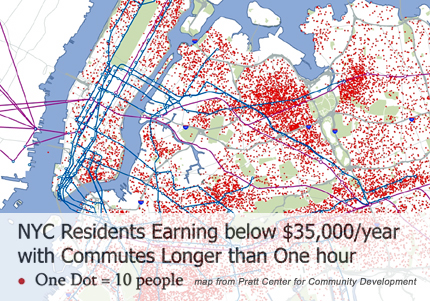

Meanwhile, three quarters of a million New Yorkers now travel over an hour each way to work. Two thirds of these commuters are on their way to jobs that pay less than $35,000 per year. These are folks who live at the far ends of subway lines or in places the subway doesn't go, or who commute to places the subway doesn't connect them to.

Rising housing costs have forced many low- and moderate-income people out of neighborhoods with good access to transit - such as Harlem, Williamsburg, Jackson Heights, to name a few -- to places like Soundview, East Flatbush, East Elmhurst and many others from which it's a bus ride or maybe two bus rides to the closest subway.

Another factor is where the jobs are. While jobs in the financial and creative sectors are concentrated in Manhattan, low- and moderate-wage employment in services, the trades and manufacturing is dispersed across the city. Most New Yorkers work in the same borough they live in, but unless that borough is Manhattan, this translates into long transit trips to work. An intra-borough trip that might take 20 minutes by car can take 45 minutes or more by bus because buses are slow and connections are poor.

As a result, poor transit access restricts economic opportunity. Workers with less than a college degree already struggle to find a limited universe of jobs that are a match for their skills; that universe is further reduced when they consider only jobs within a manageable commute from transit-poor neighborhoods. And opportunities for advancement through education are likely to be confined to the unaccredited colleges and trade schools that cluster around outer-borough transit hubs.

Long commutes also undermine family and community life. Low-wage workers seldom have the flexibility that allows higher-earning parents to juggle school and community meetings, get kids to after-school activities, doctor visits, etc., and handle the inevitable emergencies. When workplaces are an hour away from home, school and childcare, it's hard to find time for more than the most basic parenting tasks.

Many of New York's public housing developments are transit-deprived. Robert Moses, in particular, tended to build projects in isolated areas where land was cheap and local opposition was minimal. The Master Builder may not have cared whether his tenants had access to jobs, education, and services -- so to this day, tens of thousands of public housing residents remain stranded far from the nearest subway line.

BRT and Neighborhoods

As Phase 1 of the Second Avenue Subway inches toward completion, nobody in Morrisania, Canarsie or South Jamaica is holding their breaths waiting for the train to come in. But bus rapid transit -- "a subway running above the ground on rubber tires" could be in place relatively quickly and cheaply. Full BRT - with protected lanes, traffic signal prioritization and off-board fare payment - can move people at speeds and volumes that dramatically shorten travel times over long routes. Moreover, BRT will be accessible from its inception - to wheelchair users, seniors and everybody who has trouble climbing stairs - while the goal of providing access at every subway stop is still many years away. BRT will create an efficient no-transfer option for hundreds of thousands of people whose mobility is now limited to the radius a conventional bus can cover at a speed of 7.9 miles per hour.

Though dedicating lanes to buses presents a political challenge, BRT complements plans to reduce car use by making more efficient use of street space. There are a number of ways to ensure that the lanes are used by buses and buses alone. The lanes can be physically protected, but license plate cameras on the buses themselves are a more elegant solution -- letting the buses themselves nab the drivers who infringe on their space. However, enforcement cameras face an uncertain fate in the state legislature, where Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has thus far resisted pressure to authorize additional red-light cameras in the city.

The City's First Steps

On March 25, Mayor Michel Bloomberg presided over the joint announcement of New York's first BRT route by Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan and Lee Sander, executive director of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Dubbed "Select Bus Service," it will replace limited-stop Bx12 service on Fordham Road/Pelham Parkway in the Bronx starting June 29. Most of the key BRT features are part of the package including off-board fare payment. Machines at bus stops will accept MetroCards or cash in exchange for a paper receipt. Following the example of many European transit systems, riders will be subject to random checks - but passengers will be able to board through front and rear doors, eliminating the bottleneck that forms as each rider swipes at the front door.

BRT-specific vehicles - low-floor buses with multiple doors - are still in the future, but the willingness of the transportation department and MTA to try "honor system" payment, as well as the department's painstaking work with local stakeholders to resolve conflicts around truck unloading and parking, signals a will to make this first route work. The more successful the initial BRT project is, Sadik-Khan reasons, the more communities will clamor for BRT to come to them as well.

Transit Funding without Congestion Pricing

Now that the state has failed to act on congestion pricing, when BRT will roll in the other boroughs is anybody's guess. The federal Urban Partnership grant that New York forfeited when the State Assembly did not vote on congestion pricing earlier this month would have funded a five-route pilot project, adding one BRT route each in Staten Island and Brooklyn, and two in Manhattan. (Resistance to the removal of some parking along Merrick Boulevard was so fierce that plans for a Queens route were put on hold, and a 34th Street crosstown route advanced in its place.) Of the $354 million in federal funds, $112 million would have paid for BRT.

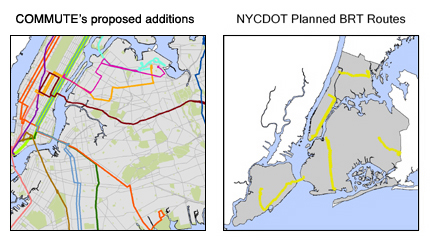

Meanwhile, a small but growing number of transit advocates and riders who know what BRT is are clamoring for more routes. COMMUTE! (Communities United for Transportation Equity), a coalition of community groups coordinated by the Pratt Center for Community Development, wants the BRT routes to cross bridges and connect the boroughs, making buses a more serious complement to the subway system.

The pilot program confined each route to its respective borough, so that the Rogers Avenue/Nostrand Avenue route in Brooklyn would serve a dense and underserved slice of East Flatbush, Crown Heights and Bushwick - but then dump passengers at Williamsburg Bridge plaza, presumably to elbow their way onto already full J, M and Z trains to get into Manhattan. Since the transportation department is already planning to put a dedicated bus lane on the Williamsburg Bridge, it would be logical to connect the Brooklyn BRT route to the also-planned First/Second Avenue BRT.

With both the one-time shot of federal funding and the projected $500 million per year in net revenues from congestion pricing off the table for the moment, BRT may be more important than ever. The MTA Capital Plan has, in words of Straphangers Campaign spokesman Gene Russianoff, "more hole than plan," with less than $12 billion of a five-year, $29 billion shopping list accounted for. As the rail and subway projects envisioned in that plan recede into the future, BRT makes more sense than ever. It will not prevent us from building light rail or subways in the future, but for now it makes intelligent use of the infrastructure we already have - our streets.

Joan Byron is the director of the Sustainability and Environmental Justice Initiative at the Pratt Center for Community Development.Â

How to Fix Our Transportation Woes -- Without the Fee

Photo (cc) Fabrizio Salvetti

Fidler's proposal includes creating taxi stands in busy areas and supporting hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.

Anyone who has seen the horror movie "Carrie" knows that you can't turn your back on the screen until the credits have finished running. It is only with that reservation that I am willing to even consider life after the death of the mayor's proposal for congestion pricing.

On the day after the obituaries were written in New York's papers, word filtered down from Albany that the three men were still in a room and so the proposal could reach its bloody hand up from its grave. Despite such reports, it is my fervent hope that this bad idea has been laid to final rest by both houses of the legislature. Indeed, while the editorial writers rant at Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, it is clear that neither the State Assembly nor the Senate had enough votes to pass the plan.

Nonetheless, the problems that this plan sought to address remain very real. Though in the end congestion pricing morphed into a plan that was just about the money, the initially stated goals were all laudable: reducing traffic congestion throughout our region, cleaning our air and raising the critical revenue to support regional transportation. That's how I define the goals, in any event.

The Truth About Transportation

As we roll up our sleeves and put some thought into these problems -- before we put the necessary energy into solutions -- we ought to acknowledge at least three critical truths about moving people in our area. The first is that it is a regional issue requiring a regional solution. We move people from both the city and surrounding counties to New York's central business district and to other places of business. The solutions -- and the burdens -- ought to be regional as well. And it would be nice if we didn't trip and fall over a state line and could include our neighbors from New Jersey in the process.

Second, until we reach the days of the Star Trek transporter, people will move about -- and need to move about -- by bus, by train and by car. The absence of any one of these three would cause the other two to collapse. No one of them alone can shoulder the burden of moving millions of people to diverse locations.

Third, someone has got to pay for it. The needed infrastructure for all buses, trains and cars is massive and in constant need of upgrading and repair. The corollary of that is that the method of paying for it has to be both fair and effective.

In the spirit of the musical "Oklahoma," now is the time for the cowmen and the farmers to be friends. Whether you commute by car, bus, train, ferry or bicycle, a sense of mutual goals has to emerge. And whether you were for or against congestion pricing, a sense of mutual cooperation and respect needs to develop, together with a measured sense of urgency.

Paying for It

There have been many alternative proposals that address the city's traffic and transportation problems that do not involve the objectionable practice of allocating access to the core of our city according to who can and who cannot afford it. I have offered mine, and it is a proposal with a decent level of support from my colleagues on the City Council. It might be a good starting point for discussion. It has nine key elements. Let me give you the highlights.

I am proposing a one third of one percent tax on business payrolls, to be paid not only by businesses in the City of New York, but by those in Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester and Rockland counties as well. (If only we could include suburban New Jersey...) That means that a business with an annual payroll of half a million dollars would pay an additional sum of $1,667. This tax -- and yes, I know that tax is a dirty word -- would raise over a billion dollars in its first year, more than the projected revenues from congestion pricing and the $354 million in promised federal aid combined. The money would go to support transportation infrastructure of all kinds, including our subways, buses and commuter rail, and would have to include a guarantee that it be used fairly in the nine counties paying it.

Other broad based taxes could do this as well. For example, the Assembly Democrats have proposed a millionaire's tax. The key is that the tax be regional and broad-based, be effective and be borne fairly throughout the region.

Clearing the Jams

There are creative ways to attack congestion, both long and short term, by looking at its root causes. In the short term, we can move some city agencies out of the central business district to outer borough neighborhoods along train lines. We can change the culture of the taxi cab industry -- cabs account for 39 percent of the vehicle miles traveled in the business district are traveled by cabs, with a third of all those miles being racked up while the taxis are empty and cruising for passengers. Let's put a taxi stand on almost every block of the central business district. Let's make them more attractive by blowing in some hot air in the winter and cool air in the summer- and then require that cabs only pick up passengers at taxi stands except in inclement weather and at night.

Let's finish the subway link to Staten Island that was begun in 1923, so that Staten Islanders can actually opt to take a train to work in lieu of a gasoline guzzling car or bus. And let's finally finish the mission for which the Port Authority was originally created: the construction of the Cross Harbor Freight Tunnel, which would take a million truck runs off the roads of our City each year. And yes, Maspeth, we can find a way to make that work for your neighborhood too.

Finally, we need to take the absolute world leadership in developing the infrastructure to support the use of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles. These zero-emission vehicles could be in our marketplace as soon as next year. But who would buy one if there is no place to re-fuel with hydrogen? White Plains has just signed on to an experimental program, but our city can truly lead the way.

For the past year, congestion pricing was the Holy Grail, but it turned to be a false prize. We still confront the goal of sustaining our transportation system, cleaning our air and reducing traffic congestion. There is much to do.

I am ready. Are you in, Mr. Mayor?

Lew Fidler, a Democrat, represents Brooklyn's 46th district on the New York City Council.Â

A Serious Solution for a Serious Problem

Photo (cc) Brian Rosner

London's successful congestion pricing plan was initially met with controversy.

Last Monday, the New York State legislature declined to vote on congestion pricing and let the deadline for $354 million in federal transit funds run out. The grant may be gone, but the challenges of unhealthy air, poorly funded mass transit and traffic-choked streets remain very much with us. Thankfully, they are now front and center in the public debate about the future of New York City.

Yes, charging people to drive in Manhattan is controversial. However, as a solution to our immense traffic and transit problems, congestion pricing is also effective and fair. It is the only solution that will both cut traffic and expand transit. That's why I believe that our leaders will return to it on its merits.

In fact, congestion pricing has come a long way in a remarkably short time. A year ago, it was scarcely on the political radar at all. Today, there is a specific proposal, put forward by a commission organized in collaboration by state and city government and vetted in dozens of public hearings.

And there's extraordinary public support. Two out of three (67 percent) of New Yorkers, including a majority in every borough, support congestion pricing when the revenue is dedicated to transit improvement. The City Council, in a strong act of leadership, voted 30 to 20 in favor. Labor, community, environmental justice, public health and business leaders stepped forward in support. Small businesses spoke in favor of less traffic, less wasted fuel and being able to reach more customers faster.

The debate has moved this far because we all know that less traffic and better transit are keys to New York City's economic growth and air quality. In the next 25 years, New York will grow by about a million more people. To be ready to serve this population, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority must have a well-financed capital plan immediately.

Our children must be also able to grow up in this city without being exposed to high levels of traffic pollution. The effects on asthma attacks, brain development, lung function and heart disease are just too strong to ignore. A recent study shows that the exposure to high levels of vehicle pollution can have a similar impact on children's IQs as exposure to lead or their mother smoking during pregnancy. How can we not act?

The congestion pricing proposal itself improved over the last year. The commission modified the mayor's original proposal: The northern border moved to 60th Street; the number of cameras was slashed from 300 to around 25; operating costs were cut close to $100 million; detailed environmental review was spelled out. The State Senate bill added relief for low-income drivers and demanded that New Jersey pay its fair share. Finally, individual legislators raised ideas that could easily have become amendments, including, for example, a three-year pilot program; expanded environmental review during the pilot; and exemptions for cancer patients needing to drive to medical care. Unfortunately, these proposals were never incorporated into an amended bill, and state legislators never got a chance to vote on them.

It is not surprising that asking people to pay more to bring a car into the central business district at peak business hours will be controversial. Every city that has tried congestion pricing, including London, Singapore and Stockholm, faced similar controversy. In each city, as people begin to see the benefits of congestion pricing, public support grows. Better transit. Less traffic. Cleaner air. Faster commutes. It is no wonder that public support in New York City is so high and that the City Council voted "yes."

Solutions for the Short Term

On April 7, we learned that Albany was not ready to vote yet. As a result, New York City missed out on a federal grant that would have brought expanded subway, bus and ferry service to every borough this year. We missed out on a 39 percent drop in gridlock in western Queens, a 22 percent drop in gridlock in northwest Brooklyn and a 20 percent drop in gridlock in Harlem. We missed out on $500 million in net annual revenues from the fees that would have delivered bus rapid transit, improved subway service and faster commutes.

We must continue to work together to find innovative solutions. There are important steps that can be taken now, including:

* Better traffic management. Slashing abuse of placards, the permits that allow many city employees to park for free. (Last week's crackdown in lower Manhattan is encouraging.) Better enforcement of traffic laws. Less double-parking. These simple steps can be taken with limited resources. However, they are not enough. Without congestion pricing, their benefits may not be long lasting, as freeing up more road space inevitably attracts more cars. We should take these steps but not stop there.

* Focus on transit that can be improved quickly. Bus-rapid-transit lines (especially for neighborhoods that lack subway access now). More ferries. Extra subway cars and buses. The lost federal grant would have paid for exactly these kinds of improvements. Now we will have to find the money elsewhere -- not easy, in a time of declining state and city revenues.

* Encourage clean vehicle technology. Diesel filters for the dirtiest trucks and buses, incentives to switch taxis and livery cars to hybrids, clean fuels for ferries -- these are all important. But with traffic volume on the rise, technology alone won't unclog our streets or speed commutes.

Many large-scale infrastructure solutions face uncertain financial futures. For example, Environmental Defense Fund has long supported the rail-freight tunnel and the full Second Avenue Subway, but there has never been enough federal, state or city money to get them built. In a time of declining state and federal revenues, where will the resources come from? Ideas for new income taxes, like the millionaires' tax, may well gain traction. But with state revenues declining, it may well be easier to dedicate a congestion charge to the MTA "lockbox" than to fight off competing demands on general tax revenue.

Congestion pricing is an idea that makes sense for New York, and we're tantalizingly close to a version that fits New York City's needs. New York City should have the chance to try congestion pricing.

Andrew H. Darrell is the New York regional director of Environmental Defense Fund and a former member of the New York Traffic Mitigation Commission. EDF works on economics-based solutions to environmental problems and has been active on congestion pricing both here and in other cities for many years.Â

Street Closures and the Battle of Prince Street

"If they want to come here with their engineers and bulldozers, we'll be at the barricades with balaclavas," said Sean Sweeny, director of the SoHo Alliance. For Sweeney and his supporters, the Department of Transportation's plan to close Prince Street in between Lafayette Street and West Broadway to automobile traffic from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. for 14 consecutive summer Sundays constitutes an assault on their neighborhood.

Last month, when the department presented the plan to Manhattan Community Board 2's Traffic and Transportation Committee, some people let the agency know as much. "The whole room erupted in boos. It turned riotous," Sweeney said. "I've been on the Community Board for 18 years and it was one of the most cacophonous, riotous, calamitous meetings I've ever been part of. SoHo has been ruined in the last 10 years with commercialism. This would have been the nail in the coffin. The meeting was our Little Big Horn, our last stand. We're not becoming a mall."

But other SoHo residents, like Ian Dutton and the rest of Community Board 2's Traffic and Transportation Committee disagree. "If you think that closing Prince Street on a couple of Sundays will turn it into a mall, you haven't walked in SoHo in 10 years," said Dutton. "What you have now is a very uncomfortable pedestrian experience for everyone ( the people who live here and the tourists) so why not see what can be done to make it better. There is no point in cutting off our nose to spite our face."

And so the battle lines were drawn.

Shutting Streets

Despite the almost immediate acerbic reactions to the plan (the Streetsblog.org post that broke the story received 75 comments , 10 of which were, to put it mildly, vehemently opposed). The Department of Transportation did not propose a temporary closure on Prince Street simply to flex its muscles. The idea probably had root in London's highly successful temporary street closures, called "Very Important Pedestrian days," on Regent and Oxford streets, two of the West End's premiere shopping corridors. The work of world renowned urban planner Jan Gehl, who conducted pedestrian counts and street life surveys for the city along Prince Street in 2007 may have also encouraged the proposal, along with a 2006 Transportation Alternatives's study conducted by Bruce Schaller, now a deputy commissioner at the transportation department.

All of these efforts point to a way of creating districts where pedestrians greatly outnumber vehicles. In some locations, the reasoning goes, a street has more value as a place for pedestrians than solely as a means of automobile transportation. This kind of thinking no doubt guided the transportation department, along with a desire to create a more pedestrian friendly city, an explicit aim of both Mayor Michael Bloomberg's PlaNYC2030 and Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan

Of course, temporary street closures are nothing new. New York City has a long history of them, most far less contentious than the recent Prince Street hullabaloo. In 1970, Mayor John Lindsay decreed that portions of Fifth Avenue and 14th Street be closed to cars in honor of Earth Day. The plan was so popular that Fifth Avenue was made car-free four times that July. A Department of Commerce and Industry survey concluded that 77 percent of the visitors stopped to shop on car-free days. "Suddenly the avenue was full of baby carriages, bicyclists, street musicians, smiling couples, all reveling in the car-free quiet and safety of what had become wall to wall sidewalk," Time magazine reported later that summer.

For five years in the early 1990s then-Bronx Borough president Fernando Ferrer closed the Grand Concourse from 161st Street to 198th Street every Sunday from July to November. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani put an end to that, but in 2005 Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion Jr. brought Car-Free Sundays back to the Grand Concourse where they remain a summer attraction.

Even small-scale temporary street closures, like the one on Sundays on the Lower East Side's Orchard Street, which has been happening since the mid-1960s, have proved popular over time and largely without a deleterious impact on area traffic. "Disappearing Traffic? The Story So Far," a paper by Sally Cairns and others, examined over 70 road closures and surveyed more than 200 transportation professionals on the subject. It found that "predictions of traffic problems are often unnecessarily alarmist, and that, given appropriate local circumstances, significant reductions in overall traffic levels can occur."

Still, when the idea of closing a street, even temporarily, is first proposed, many local businesses and residents object. "Communities tend to be resistant to any city-sponsored street closing. They claim that it's people in cars who are shoppers," said "Gridlock" Sam Schwartz, president and CEO of Sam Schwartz PLLC and a former first deputy commissioner at the city Department of Transportation. "It's kind of like a Yogi Berra-ism, trying to convince people that 'nobody goes there anymore because it's too crowded."

Fighting For Space

Few would argue that Prince Street isn't already crowded. There are narrow sidewalks, scores of vendors, cars, bikes and subway entrances between Lafayette Street and West Broadway. According to the transportation department's "Prince Street Pedestrian Project" presentation, about 4,500 people per hour walk on Prince Street's sidewalks on Saturday and Sundays between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m., while 200 cars per hour use the street during the same time period.

Those in favor of the plan see it as a sensible and proportionate allocation of street space, a precious commodity in downtown Manhattan. They emphasize that a trial closure one day a week will determine whether creating more room for people will make the street safer, the vending less intrusive and easier to regulate, and the neighborhood a more pleasant place to live, work and shop. They point to Schaller's study of Prince Street, which showed only 8 percent of people surveyed arrive there in a private car and 80 percent perceive the street as being overcrowded.

The Schaller Consulting study also found that "by a ratio of five-to-one, expanding pedestrian space would attract people to come to Prince Street more often, even if that meant taking away space to park. Results are almost identical for visitors and those who work or live in the area."

Many of the SoHo residents who oppose the Prince Street pilot program object for precisely that reason. They do not want more were people on their neighborhood streets. Many point to what Sweeney describes as the "garbage, traffic congestion and crowds of strolling tourists who think they own the street and stare at the residents in their windows like they are curiosities" brought annually by the Feast of San Gennaro, which runs for 11 days on neighboring Mulberry Street. "We don't like tourists," Sweeney said.

For its part, the transportation department has insisted that the temporary closure will not turn Prince Street into a permanent street fair. Representatives showed a slide at the Community Board meeting emphasizing "no stalls, no food kiosks, games or rides," and promised to address concerns about the street vendors by increasing enforcement. Many at the meeting, though, remained skeptical.

Ethan Kent, a vice president at the Project for Public Spaces, a non-profit group that works with cities all over the world to create engaging streets and public spaces that serve communities, said, "If I thought that temporary closures meant a street fair every Sunday, I wouldn't want it either, but that's just not the case. There are ways to make streets work for everyone, but you have to plan and manage. The best way to prevent a neighborhood from changing for the worse is planning for the best."

Kent, who has consulted on pedestrian projects from Hong Kong to Poughkeepsie, emphasized the importance of involving all the stakeholders as early as possible in any planning project. "Maybe if the DOT had gotten some businesses on board and partnered them with the supportive residents and then asked, 'what can make this street work better for you?' there would have been a different outcome. I'm sure all the naysayers weren't in favor of speeding cars and honking horns and exhaust fumes, but were afraid of a plan they had no part in," he said in response to the controversy in SoHo

Consulting The Community

"Planning" and "community involvement" have become buzzwords in the wake of all that has happened in SoHo. On both sides of the debate, people point to the need for community involvement in the planning of any temporary street closure. Shirley Secunda, a retired urban planner and chair of Community Board 2's Traffic and Transportation Committee, who supports the street closing plan said, of the administration "they came before us with a fully developed program ( before people had a chance to give input and even if it's a good plan ( that's a limitation right there. If they gave us more time we could have worked with them to make sure it was as good as it could be for everyone."

Sweeney, more colorfully concurred saying, "The process was so skewed and plutocratic and autocratic. The DOT tried to bulldoze SoHo."

And so despite their differences, the two camps of SoHo residents fighting over 14 summer Sundays on Prince Street agreed on the need for an open process. Community Board 2, at the behest of many area residents, eventually passed a resolution declining the transportation department's proposal that reflects as much. It reads: "CB2 also appreciates DOT's willingness to monitor and modify this test project based on community criteria and input and to sunset it if not affirmatively reviewed, but regrets the absence in this case of a true community-based process in which the neighborhood has been consulted from the start about its problems, concerns and improvement ideas."

For now the future of the Prince Street plan is murky. Now that the Communty Board has come out against it, the transportation department seems disinclined to go ahead with it in its current form. But the idea of street closings remains very much alive. Some people in SoHo would still like to see pedestrian imporvements in the area, and the department, without specifying any locations, confirmed that it is looking at similar proposals in different neighborhoods around the city.

Its statement about Prince Street implies that the department has learned a bit from what happened: "We have listened to the concerns voiced by SoHo residents and will find ways to address our shared concerns about traffic, street vendors, and congestion," said department spokesman Seth Solomonow. For their sake, and for the future of temporary street closures, that seems like a sensible course of action.

Graham Beck is the managing editor of StreetBeat, the biweekly newsletter of Transportation Alternatives and a writer. He lives in Brooklyn.Â

Breaking the Gridlock on Congestion Pricing

This article was revised on March 27 to reflect recent developments.

In the 11 months since Mayor Michael Bloomberg put forth a plan to charge people to drive in Manhattan on weekdays, the proposal has been caught in government's equivalent of rush hour on Canal Street. With time running out for a final decision, will the plan reach its destination? Or will its opponents bring it sputtering into the junkyard of failed public policy initiatives?

The past days have seen a flurry of activity around the issue. Gov. David Paterson's announced on March 21 that he supported the idea and had submitted a bill for consideration by the State Legislature. On the following Monday, as the City Council held hearings on congestion pricing, Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno introduced the bill in the Senate. And on March 26, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver introduced the bill in the Assembly -- without giving it his support

With the April 7 deadline for enacting the bill -- and getting $354 million of federal money -- fast approaching , the issue promises to be the subject of intense lobbying and debate in the days to come. As an indication, the City Council hearings were packed and went on from 11 a.m. until well into the evening. To kick things off, City Council has scheduled a full day of hearings on it for today (March 24). Testimony from people on all sides confronted the many issues that have swirled around this since last spring, particularly whether charging people to use city streets is fair and whether it can both cut air pollution and provide money for mass transit.

How We Got Here

In its current incarnation, the congestion pricing proposal would charge cars $8 a day to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays.

The mayor's plan for congestion pricing -- which has seen changes over the past months -- was part of his PlaNYC2030 for an environmentally sustainable city announced on Earth Day 2007. (For more coverage of the plan, see Gotham Gazette's new Sustainability Watch.) The idea was to charge people to drive into or around the Manhattan business district during the workweek and use that money to fund mass transit improvements.

Proponents viewed it as both a solution to New York's persistent traffic congestion and air pollution problems and the constant shortage of funds for subways and buses. Opponents questioned whether the plan really would reduce noxious emissions and charged that it could pose a hardship to lower income New Yorkers who have to drive to Manhattan for business, medical appointments and the like.

As is so frequently the case with schemes from the city, the plan stalled in Albany. Bloomberg originally anticipated bypassing the City Council entirely so congestion pricing would just need state approval. It won support from Majority Leader Bruno and then Gov. Eliot Spitzer but ran into opposition from the Democratic-controlled Assembly. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver kept his opinions on this issue -- whatever they might be -- to himself.

As reporters wrote the obituary for the driving fees, the governor, majority leader and speaker -- the three men in a room, joined for this round by Bloomberg -- drafted a compromise. A commission would be appointed to study proposals to reduce traffic and issue recommendations. Its plan would then go to the City Council, the legislature and the governor for approval.

Hanging in the balance was some $354 million in federal Department of Transportation Funds. To get the money, New York had to enact a traffic mitigation plan including fees by March 31.

With congestion pricing proponents in the majority, the commission issued its report, calling for a modified version of Bloomberg's original plan, on Jan. 31. And then it sat. And sat.

As of March 19, no bill had been drafted in either the legislature or City Council. No one had stepped forward to sponsor the needed legislation. The new governor had not expressed an opinion on the concept nor had Silver. Meanwhile, a New York Times story indicated support eroding on the council. Frustrated at seeing the plan falter, Bloomberg lashed out at opponents,

"Our children deserve better from us than an inheritance of excuses bequeathed by business as usual," he said in a speech Wednesday." This isn't just a test of our policies. It's a test of our character."

Paterson Steps In

Then Paterson not only said he would back congestion pricing, but put forward a bill with specifics, including the size of the congestion zone, how the revenues would be spent, what vehicles would be exempt and so on. Calling the governor's actions "tremendously helpful," Michael O'Loughlin, director of the Campaign for New York City's Future, a coalition backing congestion pricing, said the bill "gives people something to work with."

In a written statement, Paterson said he had come to this decision because "congestion pricing addresses two urgent concerns of the residents of New York City and its suburbs: the need to reduce congestion on our streets and roads, and thereby reduce pollution and global warming; and the need to raise significant revenue for mass transit improvements."

Opponents expressed dismay. "Even Governor Paterson's good name on Good Friday cannot resurrect this flawed and unfair tax legislation called congestion pricing," said a statement from Walter McCaffrey of Keep NYC Congestion Tax Free.

Paterson's support does not guarantee passage. The City Council still needs to put forth a bill, although that measure, rather than being a detailed proposal, could simply urge the legislature to back the fees. Even though this council has proved reluctant to defy Bloomberg and Speaker Christine Quinn, who supports congestion pricing, many opponents remain and a close vote is anticipated (see related story) Quinn has said she expects the council to back the pricing plan.

The council recessed rather than adjourned its regularly scheduled March 26 meeting, leaving the door open to convene an unplanned meeting to consider the issue. Quinn has denied widespread speculation that the council will vote on the pricing plan on Monday, March 31.

Up in Albany, Silver continues to be less than enthusiastic. He was quoted as saying "we still have a long road to go" before the Assembly passes congestion pricing. The Daily News quoted Democratic legislators as saying that Silver's announcement of the bill was greeted with boos at a closed door meeting.

Not unexpectedly, the measure again could become ensnared in Albany politics and package deals. The Times reported that Silver could let congestion pricing move ahead-- in return for support from Paterson and others for some kind of tax on New Yorkers making more than $1 million. That idea, unlike congestion pricing, seems to have wide support among Democratic members of the Assembly. It's unlikely, though, to win approval from the Senate Republicans who have backed congestion pricing.

And polls show many New Yorkers oppose the idea. A Quinnipiac University survey taken in January found opponents outnumbered supporters almost two-to-one.

Supporters, though, expressed optimism. "I don't see how it can't work out," said Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives. "We can't fit more cars in New York City and we can't move people around by car in the city. So we need to discourage driving and at the same time fund mass transit." Congestion pricing, in the eyes of its supporters, does all that.

The Current Plan

In the months since its original proposal, the specifics of congestion pricing have changed. The governor's bill incorporates the revisions put forth by the Traffic Mitigation Commission in January and includes a few changes made since then.

The zone: The Paterson bill adopts the zone set forth in the commission report and so would charge people simply to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street. Bloomberg's original plan would have set the boundary at 86th Street, would have exempted some peripheral highways, such as the FDR Drive, and would also have charged people to drive within the zone during the work week.

The fees: Under both the commission's recommendations and the governor's bill, the base fee for cars entering the area would be $8. Trucks would pay $21. But many drivers would end up paying far less since the system subtracts tolls used to enter Manhattan -- as long as the driver used E-ZPass to cross one of the rivers. So while someone using the toll-free Brooklyn Bridge would be charged an $8 congestion fee, a person who used the Queens Midtown Tunnel, which has a $4.50 toll, would pay that and a $3.50 congestion fee for a maximum charge of $8.

Residential parking: Many New Yorkers who live outside Manhattan but near subway stations objected not so much to the fee itself but to what people in neighborhoods without good subway or express bus access might do to avoid the fee. They feared their neighborhoods would become giant parking lots for commuters wanting to get closer to Manhattan and still avoid the fee.

In March, Bloomberg and Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan proposed a residential parking permit program that would, Bloomberg said, "specifically be aimed at discouraging park-and-ride activity" and at areas with large facilities like sports arenas. Individual communities would decide whether to enact the program and would set regulations for it.

The Paterson bill also calls for a residential permit parking program.

The money: New Yorkers, like most Americans, tend to be skeptical of what the government will do with their money. Some opponents of congestion pricing see it as just another tax. Many people express skepticism over whether the money really will go to transit as promised.

“I’m not going to believe for a moment the lock box can’t be broken,” said Councilmember Lew Fidler of Brooklyn, who opposes congestion pricing, at the March 24 hearing.

For now, the commission and the governor are saying it will not be. The $8 fees are expected to generate enough money to operate the program and another approximately $490 million for transit improvements. Most of that will go to support the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's five-year capital plan that by some counts could add up to $30 billion.

Critics contend that that means revenue from congestion pricing would be barely more than a drop in the bucket -- about 15 percent according to a calculation by the Times. Critics, such as Assemblymember Richard Brodsky, have charged that the fees have been “oversold” as a financing mechanism. "Congestion pricing was sold as a panacea, and what this [capital] plan admits for the first time is that it’s not,” Brodsky told the Times.

Supporters of the fees say city officials and the transportation authority have to meet their commitments. “The big problem people have is they don’t trust the MTA and even city government for following through and using the money effectively,” John Liu of Queens, chair of the transportation committee, said.

If the city and state approve congestion pricing, the city will get about $354 million in federal funds designed to promote plans to ease congestion. The substantial federal payment has spawned its own set of controversies. Last summer, Bloomberg said the city would lose the funds if the state didn't approve the proposal by July 16, 2007. It didn't - but the action the state took kept the city in the running for the money. Now Bloomberg has said the deadline is March 31. Most people think that, because of a technicality, April 7 is more like it.

Then last week U.S. Rep. Anthony Weiner, a candidate for mayor in 2009 and a congestion pricing foe, said that a congestion pricing plan might not bring in more federal money after all. Instead, Weiner said, the Bush administration might reason that since New York was taxing itself to fund transit improvements it did not need Washington's help. Bloomberg countered that Weiner's statement was "one of the stupider things I’ve ever heard said."

Whatever the specifics, proponents believe the prospect of federal funding helps their position. "It's a tough year to turn down $354 million," McLoughlin said.

Monitoring the plan: Will it work? Proponents expect the fees to cut traffic in the zone by about 6.5 percent during peak hours, resulting in "a 13 percent reduction in congestion," according to a report by the Campaign for New York City's Future. "That's the difference between a busy autumn rush hour and mid-summer when commuters are on vacation," it said. And in turn, proponents say, an easing of traffic jams will reduce pollutants, particularly those that cause asthma and the greenhouse gases that cause global warming.

Opponents counter that the plan's backers underestimate the costs and overestimate the benefits. In a report, the anti-congestion pricing group concluded congestion pricing would reduce citywide traffic by only 2 percent. And because cars and trucks are not the city's chief source of greenhouse gas emissions -- buildings are -- they say, "Even if the system is as effective as its proponents claim, it will reduce emissions by only 0.4 percent."

To address the claims and counterclaims, the governor's statement says his bill will require the city to "oversee a monitoring program for traffic, air quality, noise, parking and other environmental impacts and release annual reports" as well as a preliminary report six months after the program begins.

A Free Ride for New Jersey

Even among supporters of congestions pricing, two key issues remain unresolved. One is what some call the "Jersey inequity."

Because the plan subtracts bridge and tunnel tolls from the congestion charge, people crossing the Hudson River -- in other words -- those coming from New Jersey would not pay any more than they do now.

In a letter to Bloomberg last month, some 20 members of the City Council, most supportive of congestion pricing, laid out some concerns. One was the need for residential parking permits. The other was the question of the Jersey drivers. As it is now, said Tim Roberts, policy director for Councilmember David Yassky, who spearheaded the letter, "There's no disincentive for New Jersey suburbanites to drive in."

The council members then asked Bloomberg to fix the problem "either by amending the plan to require commuters from outside New York City to pay a congestion fee in addition to bridge and tunnel tolls, or by forcing the Port Authority to agree to devote a significant portion of their revenue from Hudson River crossings to funding mass transit in New York City."

While Bloomberg has not yet endorsed either of these ideas, he did leave the door open to compromise. In his response to Paterson's support Friday, Bloomberg issued a statement saying, "We will work with the governor and our partners in the State Legislature and the City Council to address outstanding issues - including reducing the impact on lower income drivers, and concerns about commuters who use Port Authority crossings contributing to the MTA Capital plan."

At the City Council hearing, transportation commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan seemed to back-pedal, telling council members it might be illegal for the city to have one fee for people coming from, say, Queens and another for people crossing the Hudson. Rit Aggarwala, director of the mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning, indicated the law might not be the only sticking point. “The other is a policy question of whether any special treatment is a good idea,” he said.

Regardless of its merits, the New Jersey issue is an important one, said Rich Kassel, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. "There is a large block on the council and probably of Assembly members for whom this is a threshold issue and it will have to be dealt with," he said.

Roberts said Yassky wanted the changes, but would support congestion pricing anyway because whatever the plan's failings "it's better than nothing."

Penalizing the Poor?

And what about those low-income drivers? Proponents of congestion pricing question how many there really are. For example, in a look at Paterson's old State Senate district in Harlem, the Tri State Transportation Campaign found that about 80 percent of the residents, with an average household income of about $38,000 a year, did not even own a car. The 20 percent who did own a car had an average household income of more than $89,000.

Opponents of the charges, though, say those numbers are misleading. With spotty transit service in outlying areas of the city, many people of modest incomes do rely on cars to bring them to Manhattan. In particular, they cite an elderly person who has to come to Manhattan for medical care.

Further the plan heavily favors people who pay tolls with electronic E-ZPasses. Under the plan, users of the pass pay a congestion fee of $8, while those without them would pay $9. And while the E-ZPass users have the fee deducted from the money in their accounts, those without the passes will have to figure out how to pay — and pay quickly The bill carries a $65 fine for anyone who does not pay a congestion charge within 48 hours of incurring it.

The city wants to encourage E-ZPass use. But the preferential treatment given those who have them raises concerns about equity since occasional and low-income drivers may be less likely to have the electronic tags than more affluent drivers.

There does seem to be movement toward providing a tax credit for lower income people who must drive into the city. The New York Post reported that officials could offer a break to motorists who pay the $8 and qualify for the earned-income credit, $35,241 a year for a family of three in annual income.

"It'll cost something like $10 million" out of the $500 million expected to be raised, the source told the Post adding, "We're not talking about a lot of money."

Even so, it would serve to blunt one of the more powerful arguments the opponents have at their disposal.

In a Jam

No one argues that New York City does not have a traffic problem. Over the past year, a number of plans have been put forth to address it. Some have called for putting tolls on the East River bridges, which the commission considered and ultimately rejected. Keep NYC Congestion Tax Free put out a multifacted plan to reduce traffic, including charging more for curbside parking, reducing the number of free parking permits for city employees, changing the toll system on the Verrazano Bridge.

In the days to come, people on both sides will press their representatives. Advocates will seek to convey the message that "this is an opportunity for elected officials to make a huge impact to improve things here," said Budnick of Transportation Alternatives.

But given the political volatility of the idea, and a complicated election calculus spawned by legislative elections this year and many term-limited council members casting about for their next post, no one expects it to be easy. Members of the legislature and the council seem to be eyeing each other warily, wondering who will blink.

"No one knows who moves first," said Kassel. But, he said, "I am seeing a lot of people not ready to vote for it but who recognize that congestion pricing is coming" and that we need to fund the transit system.

Â

A Seafaring Commute

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn endorsed the creation of a citywide ferry service and an expansion of a small business insurance program in her State of the City address last week. Now advocates and stakeholders are weighing in, and - for the most part - appear to be praising the proposals.

Last week, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn announced her support for a five-borough, year-round ferry system that Mayor Bloomberg and the city Department of Transportation are developing. Such a proposal may seem like a pipe dream to many New Yorkers, who have seen ferry service remain fairly stagnant, either from a shortage of funding or an apparent lack of demand.

But the next time you are heading between waterfront neighborhoods like Astoria, Queens and Red Hook, Brooklyn, just imagine how much nicer the trip could be on a ferry. Rather than fuming at the scarcity of G trains, envision yourself on the ferry’s top deck as you are whisked down the East River and the Manhattan skyline floats by.

A comprehensive ferry system would not only give us a better view, it would turn waterway commuting into a viable and appealing form of public transportation. If done right, a ferry system could be affordable, environmentally conscious and ease the mounting pressure on our rickety transit system.

Transit for a Coastal City

The Big Apple has had a long and complicated relationship with ferries. Gone are the days when steamers plied the waters between Manhattan and Rockaway several times a day with more than 3,000 passengers aboard. With notable exceptions like the Staten Island Ferry, waterfront commuting has gradually gone the way of the dodo. That’s because service is infrequent, fares tend to be relatively high and political support has been soft. Because of their high capacity, subways get most of the attention these days – New York City Transit just recorded its highest annual subway ridership in more than a half-century, with 1.56 billion rides in 2007.

But while the subway network hasn’t expanded in decades, the Big Apple certainly has. Neighborhoods that were once home only to industry are now coveted addresses – the only problem being that there is no subway to serve the new residents. And as anyone who has been on the subway recently knows, the trains are crowded. Congestion pricing is a great start, since it will help us pay for new buses and trains and help clean the air. But congestion pricing alone won’t solve all our transit woes, so we must explore complementary options.

Ferries have a number of advantages over other modes of mass transit. New York City is surrounded by water, and our waterways and waterfronts are, in many cases, untapped resources. Because they rely on the water to move passengers, ferries require very little infrastructure to set up compared with multi-billion dollar subway tunnels. Ferries are also flexible enough to keep up with changing population trends and would help commuters leapfrog all those local subway stops if they are going between boroughs outside Manhattan. There’s also a local economic benefit, as shops, restaurants and services would sprout near ferry terminals.

Getting Onboard

The first step should be to implement service where the need is greatest. That means in far-flung areas that have been clamoring for ferries for years. It seems barely a month goes by in Howard Beach or Broad Channel when the topic isn’t brought up at civic association meetings. Even as you are reading this, the Sunset-Ridge Waterfront Alliance is collecting signatures online for a petition to reinstate service at the 69th St. Veteran's Memorial Pier in Bay Ridge.

There is a compelling economic argument in favor of ferry service to these communities. Far Rockaway, for example, is one of the poorest areas in New York City, and its distance from the central business district of Manhattan has clearly contributed to its economic isolation -- the average commute time to Manhattan is well over one hour. The Economic Development Corporation is now reviewing bids from private ferry operators to start a two-year pilot program to lower Manhattan. The timetable isn’t clear yet, but, at a minimum, service would be provided Monday through Friday during peak rush hours.

Navigating the Obstacles

Ferries will in all likelihood require some level of government support – as our buses, subways and commuter trains all do. The price of a ticket must also be fair. In addition, a viable ferry system must include sensible connections to make the door-to-door commute a desirable one.

In too many instances, getting to and from the ferry itself is not a pleasant experience. For example, a number of large employers are located near the 34th Street dock in Manhattan, but getting to them from the water is a hassle, requiring commuters to cross the FDR Drive and another lane of cars. To reach the Hunters Point ferry terminal in Long Island City, pedestrians must use haphazard walkways and pass through an active parking lot. For commuters coming off the subways or buses in Long Island City, the shortest walking distance to the dock is 10 blocks.

We must also make sure the ferry system is environmentally sound. Energy-efficient, clean fuel vessels are essential to reducing air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Fortunately, clean-fuel watercraft is off in the future; solar-powered ferries, for example, already are in place in several cities around the world. If the new ferries are owned or operated by the city, they would also be required to use ultra low-sulfur fuel under legislation the City Council passed last week.

With New York City expected to grow to 9 million residents by the year 2030, ferries will also advance the discussion about how to create more transit-oriented development. Neighborhoods like Red Hook and Williamsburg are growing at a rapid clip yet have limited access to the subways. If we pair future communities with ferry service, we can ensure that our waterfront areas are models of 21st century design, urban planning and sustainability.

Marcia Bystryn is the executive director of the New York League of Conservation Voters. Â

Helping Old New Yorkers Get Around Town

Segundo Musse doesn't walk too much anymore. "I got hit by a car and broke both my legs," he said surveying the scene along Manhattan Avenue in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn. "I used to be quick on my feet. Now, I'm slow and I'm only getting slower."

Musse, age 67, is one of 1.25 million New York City residents over 60. Like many others his age, he has seen his mobility diminish over time. "If I need to go somewhere, I take the bus," he said. "It's a pain to get around, but with the senior pass it's cheap enough and it's better for me than walking or the subway."

Late last month, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a series of transportation improvements aimed at older New Yorkers like Musse. Bloomberg's plan, dubbed "Safe Streets for Seniors," promises traffic engineering improvements at 25 high-accident areas that are especially problematic for aging residents.

What has prompted these changes? And what will they look like?

Walk At Your Own Risk

As it is for most New Yorkers, walking is a key form of transportation for older residents. Whether one walks down the block for milk and groceries, gets to a bus or subway by foot or goes out to hail a taxi, walking is a necessary part of almost every trip in the City.

But for many older people, New York City streets are hostile turf. According to research by Transportation Alternatives, residents age 60 or over make up only 13 percent of the population, but account for more than 33 percent of all pedestrian injuries and fatalities.

Although pedestrian fatalities declined sharply in 2007, one third of the 138 pedestrians killed by cars on New York City streets were seniors. And as the elderly population grows -- the Department of City Planning predicts a 44 percent increase in residents age 65 and older by 2030 -- the need for infrastructure designed with older New Yorkers in mind becomes more pressing.

The loss of speed and agility that often accompanies old age, along with increased susceptibility to injury and fatality from falls and impacts, make seniors more vulnerable to injury and death from traffic accidents.

"The things that most people don't even have to think of, like crossing the street, some older people really struggle with. Stepping off and back on to a curb and making it across the street during a walk signal can be next to impossible," said Amy Pfeiffer, director of planning at Transportation Alternatives.

When calculating the length of a walk signal, the city transportation department uses an estimated walking speed of 4 feet per second, the speed of an average adult, to determine the length of time a pedestrian needs to cross an intersection. But many older New Yorkers move at a much slower pace.

Rachel Krug, a doctoral student at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and author of "Discriminatory by Design: A senior citizen focused study of streets and intersections on New York City's Upper East Side," found that only 25.2 percent of seniors that she observed in her research walked at 4 feet per second, with many moving closer to 2.5 feet per second. So while the transportation department calculates that it would take 15 seconds to cross a 60-foot road like 23rd Street or 72nd Street in Manhattan, many older New Yorkers would need 24 seconds.

"Near Lincoln Center, I've talked to seniors whose friends have been hit and killed at certain crossings," said Pfeiffer, who has spent hundreds of hours researching older New Yorkers' transportation habits. "They now walk out of their way to cross the street. For a senior to walk a block out of the way because they don't feel safe crossing the street is a real burden."

Krug also pointed out that perceptual impairments, like bad eyesight or balance, and even some mobility aides, like walkers, canes and wheelchairs, can make some parts of trips more difficult for elderly populations.

Getting Across Safely

So what is the city doing about this?

Following the mayor's pledge to improve 25 areas that are particularly problematic for seniors, the New York City Department of Transportation released some details of their plan. Flushing, Queens, Brighton Beech in Brooklyn, New Dorp on Staten Island, Fordham in the Bronx and Manhattan's Lower East Side will receive senior-minded safety upgrades this year. Officials state that there are 20 other neighborhoods being considered for similar enhancements in the future.

The specific improvements include:

:

- Retiming traffic signals to correspond with slower walking speeds.

- Giving pedestrians several seconds of dedicated crossing time before cars can start moving and/or turning.

- Repairing and establishing pedestrian ramps to make steps on and off the curb safer and more convenient for all people, particularly those with walkers and the like.

- Installing pedestrian islands in wide streets.

- Shortening crossing distances.

- Restricting vehicle turns.

Pfeiffer said such simple modifications go a long way. "Our basic safety treatment is so simple because we wanted to do as much as possible for as little money to help make it repeatable at other locations." More dangerous intersections, though, might require additional methods, such as enlarged corners, known as bulb-outs, she said. These expanded corners shorten the crossing distance at intersections and, by narrowing the space for cars, force the vehicles to slow down.

In 73 of New York City's 2,246 census tracts, more than 30 percent of the population is age 60 or over. In 16 of them, 40 percent of the population is 60 or above. The city hopes to concentrate its improvements in areas where they are needed most.

Making Transit Accessible

But the travel needs of older New Yorkers extend beyond crossing streets. Gene Russianoff, senior staff attorney for the Straphanger's Campaign, notes older New Yorkers are challenged on public transit as well. "If we want to have mobility for older New Yorkers the transportation system has to be more senior friendly," he said. "Signs that are easier to read would be a good start. Announcements that you can understand, that's the aim of a century long quest."

Ruth Finkelstein, vice president for health policy at the New York Academy of Medicine agrees. "Using a walker and living in Brooklyn should not mean that you lose access to a job, museums, the theater or a lifetime of friends that are in Manhattan. But to get from Brooklyn to Manhattan by bus can take two and a half hours. That's prohibitively long and so we have to get serious about subway access."

Access-a-ride service that is more consistent, convenient and courteous also is needed, according to Finkelstein and Pfeiffer.

More pubic seating, to enable those walking to take a short break, would also help. "Being comfortable in your neighborhood is a primary precursor in being able to stay independent and active. If you can't get around in your neighborhood first you can't get around anywhere else," said Finkelstein.

Checking On The Changes

In the coming months, the City Council and the New York Academy of Medicine in collaboration with the Bloomberg administration will hold a series of public forums in all five boroughs as part of the "All Ages Project" and "Age-Friendly NYC." The sessions will allow the public, and older New Yorkers in particular, to weigh in on the promised improvements and help shape further recommendations.

Millions of aging New Yorkers will be watching to see if the city makes good on its promises and whether the improvements really make it easier for older New Yorkers to move around the city.

"I've seen a lot of changes," said Musse when asked about the mayor's plans. "When the city wants to do something, I know they can."

Graham Beck is the managing editor of StreetBeat, the biweekly newsletter of Transportation Alternatives and a writer. He lives in Brooklyn.

Â

Next Steps for Congestion Pricing

On January 10, the New York City Traffic Mitigation Commission released a series of alternatives to Mayor Michael Bloomberg's original congestion pricing program for the city. The commission is slated to make final recommendations to the City Council and the State Legislature by January 31. With the commission -- and New Yorkers -- at a critical moment in this important debate, what are the alternatives under consideration and what would they mean for the city?

The Background

First, for newcomers to this issue, here are the basics: Last spring, Bloomberg released his PlaNYC 2030 proposal. PlaNYC 2030 is the mayor's environmental and sustainability legacy for the future - more than 100 transportation, housing, energy, land use and environmental programs and proposals that will reduce the city's global warming pollution by 30 percent and create the infrastructure for a city that will have 1 million more residents than it does today.

A key component of PlaNYC 2030 (certainly, the one that has received the most attention and controversy) is the proposal to create a congestion-pricing program that, for the first time, would charge drivers in midtown Manhattan at peak hours. Most of the coverage of this idea has focused on the notion of charging drivers in Manhattan's central business district to reduce congestion. But here's what's equally important: The city's proposal (and the new alternatives) will raise more than $400 million a year to give straphangers more elbow room on the 7 train, cleaner seats on the Bx1 bus and more frequent service on the F train.

In July, the state legislature passed a law that set up the commission, which embarked on a eight-month mission to consider the mayor's plan, outline alternatives and, many environmentalists and others hope, give a thumbs'-up to a three-year demonstration project by March 31, 2008.

The Five Options

The commission's January 10 report is a critical piece to figuring out what's on the horizon for the administration's proposal. (For details, check out the Interim Report itself.) In a nutshell, the commission has added four alternatives to the mayor's plan. They are:

The Mayor's Plan

Vehicles entering or leaving Manhattan below 86th Street from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. during the week would pay $8, and trucks would pay $21. Driving within the zone would cost $4 for cars, $5.50 for trucks. Vehicles paying a bridge or tunnel toll using E-Z Pass that day would pay only the difference between the toll and the congestion charge, if any. Driving on the FDR Drive and the West Side Highway would be free.

If the mayor's proposal works as planned, it would reduce the number of miles driven in the congestion pricing zone by 6.7 percent and generate $420 million a year in revenues for transit investments. On the other hand, it's a really complicated system to manage, thanks to the intra-zone charge. And despite all the pollution and traffic they generate, taxi and livery drivers would not be charged extra for the trips they make in and out of the zone all day long. Ditto, that 18-wheeler that crossed the George Washington Bridge and came down Second Avenue or Columbus Avenue en route to Midtown, since it paid $30 on the bridge already.

The Alternative Congestion Pricing Plan

This is similar to the Mayor's plan, but it has some key changes:

- The northern border of the congestion-pricing zone would be 60th Street.

- There would be no charge for private vehicles driving within the zone -- only for entering it.

- On the other hand, there would be a charge to drive on the periphery roads.

- Taxi riders within the zone would pay a $1 surcharge.

- The value of the toll offset would be capped at $8, meaning that those trucks on the George Washington Bridge would pay a $13 congestion charge if they cross 60th Street.

- Parking meter rates would go up in the zone, and residential parking tax exemptions would no longer exist in the zone.

This closely resembles a proposal offered by the Empire State Transportation Alliance, a broad coalition of business, labor, environmental and other civic organizations in the city co-chaired by the Regional Plan Association and the General Contractors Association. (Full disclosure: I'm on the alliance's steering committee.)

It would cut congestion a bit more than the mayor's proposal. More important, it would generate an additional $100 million a year to give straphangers, train commuters and bus riders some extra breathing room on their trips throughout the city. Plus, it's a heck of a lot easier to implement, thanks to the elimination of the intra-zone charge. And by eliminating the parking tax exemption and adding a surcharge for cab rides in the congestion zone, it really promotes transit as the best low-cost way to get around Manhattan.

The East River and Harlem River Toll Plan

Bye-bye, congestion pricing. Bye-bye, free bridge crossings. Hello, 24-hour bridge tolls on all river crossings. There would be no toll plazas, so this would be an E-Z Pass-only system and would charge drivers $4 to cross the rivers, no matter when they travel or what crossing they use. This would end the "free" ride on many of the 14 bridges that span the East River and the Harlem River and increase the current toll on those crossings that already have a toll (e.g., on the Henry Hudson Parkway).

The commission estimates that this would reduce miles driven by 7 percent and raise $859 million/year. They may be correct. But last time I checked, East River bridge tolls were what many would call a political "third rail," to borrow a phrase from the transit world. For this to go through, unless the governor and the mayor would have to come up with a way to convince Brooklyn, Queens, and Bronx residents that tolling these bridges does not discriminate against them, or that these new tolls won't create new, unintended traffic jams as people change their driving patterns in response to the new tolls.

The License Plate Rationing Plan

Using a rationing system based on the last digit of the vehicle's license plate, each vehicle would be prohibited from entering the congestion zone (south of 86th Street) once every five days. Cameras and extra police at each of the entry points into the rationing zone would enforce this plan.

Mexico City and Athens have led the way here - and the results were clear in both cities: a new black market in license plates and a stronger market for really old, really dirty, really cheap used cars that came with the appropriate license plate.

The Combination Plan

Like the rationing plan, this isn't congestion pricing per se, except for taxis, which would have an $8 per trip surcharge for trips that begin and/or end south of 86th Street. Instead, it's a series of measures to significantly raise parking costs (not only would the resident parking tax exemption disappear, but the city's parking tax would rise from today's 18.375 percent to 38.375 percent) and dramatically reduce the number of government parking permits in the zone.

This idea doesn't cut down on driving enough to meet the statutory minimum of a 6.7 percent reduction in the number of miles driven in the zone, even though it would raise roughly $660 million/year for transit.

Here's the bottom line: The commission has done a ton of strong analytical work to figure out the pros and cons of the mayor's original proposal, and has added four more ideas for consideration. There may be some fireworks at the commission's January 24 hearings, but the most important news will come on January 31, when the commission issues its final report to the mayor, the City Council and the State Legislature.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard.

Â

Speeding New York's Buses

New York City has the most bus riders of any city in the country -- but the slowest and most unreliable buses, according to city officials. Two and a half million people board New York City buses each day, then travel at an average of 7.5 miles per hour as their buses sit stuck in traffic, stopped at red lights or waiting for passengers to board.

"The buses are slow en route and in wait," said Gene Russianoff, attorney and chief spokesman for the New York Public Interest Research Group's commuter advocacy group, Straphangers Campaign. "It wouldn't hurt to have a copy of 'Gone with the Wind' if you're planning a long bus trip."

Almost 20 separate north-south bus routes in Manhattan require close to two hours to complete their 10-mile journey. You can take Amtrak 110 miles from New York to Philadelphia and enjoy an authentic Philly Cheese steak in about 90 minutes.

And the problem is getting worse. Incentives like free subway/bus transfers, ridership have boosted the number of bus riders by 42 percent over the past decade but between 2002 and 2006 bus speeds decreased by 4 percent, according to the mayor's office.

Despite the dismal statistics, any effort to boost the quality and popularity of mass transit in New York City must include buses. Improving bus service remains far easier, faster and more cost efficient to than improving the subway system.

"Unlike subway lines, when talking about buses these are not items that need huge multimillion dollar capital output," said New York City Councilmember John Liu, chairman of the Transportation Committee. "We're talking months, not years or decades. It is common sense."

The Road to BRT

Bus Rapid Transit, or BRT, is a major component of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's quest to improve mass transit and ease traffic congestion in New York City.

"BRT tries to combine the speed and reliability of rail services with the flexibility and cost effectiveness of bus services," said Russianoff. In true BRT, buses travel in a straight, traffic-free path, like subways and railroads, meaning that bus lanes must be specially dedicated. The methods for accomplishing this - and even the definition of "dedicated lane" -- vary from city to city and country to country. The lanes can entail painting the "bus only" lanes a bright, distinctive color, physically separating the bus lanes from other traffic or even moving the bus lanes to the middle of the road, to avoid problems with turning cars.

U.S. cities and cities around the world are successfully using an array of these techniques, to reduce traffic and wait times, increase bus speeds, rider capacity and rider satisfaction while at the same time improving the environmental and reducing the number of car accidents.

Speeding the Ride