How The Subway Shaped New York

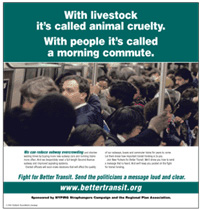

Although New York had long been the most heterogeneous city in the world, it took rapid transit to bring diverse social groups into regular contact. New Yorkers reacted differently to subway riding. For some, the subway’s speed and technology had a liberating, euphoric effect. Many other riders, though, resented the personal indignities of overcrowding and disliked being trapped in a small, confined space. When ethnic, gender and class differences were added to overcrowding and claustrophobia, the riding experience could be anxiety provoking.

The first subway route was the product of a mercantile elite. In 1913, though, a second stage of subway construction was authorized. The dual contract system, as it was known, was conceived by progressive reformers as an ambitious experiment in social planning designed to alleviate urban poverty and to assimilate immigrants. The dual system doubled the city’s rapid transit mileage to serve outlying portions of the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn and allowing working class residents to move to new areas on the outskirts.

The subway contributed to the modern city by reinforcing the extent to which New York’s spatial pattern differed from that of other big American cities. New York City is among the few U.S. cities that departs from the “doughnut” pattern of low-income and decreasing population in the center and high-income and increasing population on the periphery. New York is centered on Manhattan, which has a population that is both comparatively affluent and that has high residential densities, a combination that contributes to many of the city’s characteristics: its rapid pace, its emphasis on consumption and fashion and its 24-hour operation.

Most New Yorkers live in apartments. Every morning, hundreds of thousands empty out of their apartments and commute to midtown and lower Manhattan; every night they return home. Rapid transit’s ability to transport large numbers of people quickly and efficiently permits the dense concentration of nighttime populations in residential neighborhoods and daytime populations in midtown and Wall Street.

The subway also figures in the spatial and social gulf that divides New York City from its suburbs. New York City has the nation’s highest population densities, while its suburbs extend farther than any other.

|

Avenue Subway Construction, 16th Street. 1937 |

The New York region’s distorted transportation planning is largely responsible for this. When the third and last major phase of subway construction came to an end in 1940, the metropolis became committed to the automobile and almost all new improvement consisted of vehicular highways. More than ever before, the subway set New York City apart.

While New York has had to support its own transit network, cities such as Houston and Atlanta for their transportation rely on interstate highways, which have been financed by the federal government. Beginning in the 1960s, the federal government recognized that mass transit could no longer be dealt with on a local level. The Urban Mass Transit Act of 1964 initiated federal funding of transit construction. During the resulting boom, a number of cities built light-rail systems. Because these federal subsidies have been targeted to promote the construction of new lines rather than underwrite service or the rehabilitation of existing systems, New York City had to maintain its aging subway system largely by itself, a formidable undertaking at a time when the departure of middle-class residents to the suburbs was eroding its tax base.

The failure to correct the subway’s chronic fiscal problems, along with growing competition from the private automobile after World War II, led to the system’s near collapse in the 1970s. The subway has recently experienced a renaissance, however. Since the late 1980s, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has rebuilt every miles of track, refurbished dozens of stations and acquired hundreds of new cars. It is now considering the construction of the first new subway lines in decades, including the famously delayed Second Avenue route.

|

There is nonetheless good reason for caution. The new lines remain in planning stages and are at the mercy of changing political currents and economic conditions. Moreover, the subway’s renewal is imperiled by the financial constraints of the municipal government and the disregard of the federal government. Still, because the progress that has been made has created a new sense of hope and possibility, the subway’s second century looks promising: New Yorkers are not through making history with the subway. Clifton Hood, an associate professor of history at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, N.Y., is the author of “722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York.”

This article is excerpted from the spring 2004 issue of “The New-York Journal of American History,” the semiannual publication of the New-York Historical Society.

A Century Of Subway Activism

New York’s subways were born of activism. During the 1890s, reformers had a vision for the city. They dreamed of a reliable and inexpensive transit system that would allow workers to escape a squalid lower Manhattan and commute to and from affordable housing around town.

To a great degree, their vision came true. As subway lines opened between 1904 and 1940, so did thriving new neighborhoods from Harlem to Sunnyside to Bay Ridge. The subways shaped the city.

That tradition of activism continued, becoming particularly pronounced in the last 25 years as riders have fought to bring the subway and bus system back from near collapse.

UP FROM THE ABYSS

In the late 1970s, the decline of the city’s transit system echoed the city’s decline. The subway was notoriously unreliable, covered with graffiti and plagued with spiraling crime, fires and derailments. By 1981, subway ridership fell to its lowest level since 1917 and bus ridership also plummeted.

While city subways and buses are far from perfect today, riders and transit advocates have won tremendous progress since the early 1980s.

Today, trains are nearly 20 times more reliable than they were then. Ridership has bounced back to levels not seen since the 1950s. Graffiti on subway cars has been largely eliminated, and transit crime, fires and derailments have all been dramatically reduced.

Starting in 1997, riders could transfer for free between subways and buses — ending almost a century of griping about “two-fare zones” in neighborhoods from Sheepshead Bay to Coop City. A year later, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority began offering unlimited-ride monthly, weekly and daily passes. Today, more than half of all trips are taken on these cards.

Of course, none of this happened by accident. Since 1981, more than $30 billion (that’s billion with a B) has been invested in the subways and buses, and another $15 billion in our two commuter-rail lines.

The money was used to replace or rehabilitate every subway car and bus. The MTA expanded the subway fleet by 400 cars and increased the number of buses by 800 in order to meet growing service demands. It refurbished nearly half of all subway stations, and $750 million was invested in automating turnstiles to make fare discounts possible.

HOW TO SAVE A TRANSIT SYSTEM

How did the riders win these victories? Transit activism played a major role.

One good example is the Franklin Avenue Shuttle. The four-stop line would not exist but for local activists in central Brooklyn who struggled for more than two decades to rebuild the line, a vital transit link in Flatbush, Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Transit officials, eager to abandon the shuttle, had long neglected it. In winter, officials would routinely close the shuttle because they feared it would derail. Riders bought tokens at station booths riddled with bullet holes, and portions of platforms were sealed off because they had burned or collapsed.

But over many years, community leaders — like Helmuth Lesold, Mabel Boston and Francis Byrd — worked to restore the line. They were a constant prod at town hall meetings, news conferences and meetings with transit officials. They convinced the New York State Assembly to force the MTA to give the shuttle a $75 million top-to-bottom makeover.

The shuttle reopened in 1999, replete with bright accessible stations adorned with murals and windows created by local artists.

Time and again, the Straphangers Campaign, where I am staff attorney, and which is itself celebrating its 25th anniversary, has watched communities fight for their subway station or their neighborhood lines and bus routes:

- In the early 1980s, the organizing and outrage of West Side activists turned the 1, 2 and 3 from the worst subway lines in the city to among the best.

- Transit officials sought to abandon the Intervale Avenue station in the Bronx after arsonists destroyed it. But business and civic leaders protested and, in 1992, persuaded transit officials to rebuild it.

- Students at the College of Staten Island and Queensborough Community College won new bus routes to their campuses in 2001 and 2002.

(L) Pressure from transit riders and workers kept the fare at a nickel between 1904 and 1947. (R) Marilyn Ondrasik founded the Straphangers Campaign with support from the Fund for the City of New York and the New York Foundation. |

The 1980 Transit Speakout: A thousand people packed an auditorium on the West Side of Manhattan and vented on then-MTA Chair Richard Ravitch. One handed him a violin and said he was fiddling while the system burned; another said that people in the Bronx called the Number Two train the “Never Two.” A panel peppered Ravitch with tough questions, and a sixth-grader rated each answer as a “Yes,” “No,” or “Run Around.” Ravitch left discomforted, but the next day the forum made the front page of the Sunday Daily News. Ravitch carried that clipping around with him for months, waving it at state legislators who, several months later, approved a $7 billion, five-year transit rebuilding program.

Demanding Service: In 1991, New York City Transit officials proposed the most significant round of service cuts since the 1975 fiscal crisis. They held hearings and got an earful. A mother from the Lower East Side pointed out that cutting a route would force her children to transfer at a corner infested with drug dealers. Senior citizens on Grymes Hill on Staten Island showed how eliminating weekend bus service would isolate them from friends, church and shopping. To his everlasting credit, after the hearings, then-MTA Chairman Peter Stangl withdrew all the service cuts.

The Yellow School Bus: In 1995, former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani threatened to cut $128 million in funding for the student transit passes that more than half a million children rely on to get to school and extra-curricular activities. Scores of students, parents, education advocates, and elected officials crowded a public comment session to denounce the proposal. A deal saved most of the funding.

The Eyes and Ears of the Subways: In 2000, New York City Transit proposed closing scores of station booths and said no hearings were required. Along with a handful of elected officials, community groups and Transport Workers Union Local 100, the Straphangers Campaign differed. The courts agreed, the public showed up in droves, and transit officials pulled back on 112 of 177 proposed closings. (The same issue will play out in November, with the MTA proposing cutting another 164 booths.)

Now, the MTA plans to hold hearing on November 8, 9 and 10, on proposals to raise subway and bus fares. The public can make these meetings as memorable as some of those in the past. (For more information on the hearings or to comment by e-mail, go to the MTA Web site.)

Certainly, as it marks its centennial, transit needs riders’ voices more than ever. The system confronts many severe challenges.

The MTA faces large and growing deficits and has proposed fare increases and service cuts, less than 18 months after the biggest fare hike in city history. Starved by the state and city governments for adequate funds, much of the agency’s financial woes are due to soaring bills it must pay on the billions of dollars it borrowed to rebuild the system. The MTA’s debt service will double between 2004 and 2007 from $800 million annually to $1.6 billion.

At the same time, the MTA is proposing a new $27.6 billion five-year rebuilding program. This plan deserves public support because the system has critical needs, especially in its core program:

- buying new subway cars and buses;

- rehabilitating scores of dingy, outmoded and inaccessible stations;

- and maintaining the basic infrastructure.

Officials have also proposed a wide array of transit expansion projects. Some of the projects are essential to the city’s long-term future, like the Second Avenue Subway. Some are debatable, like a costly link between the Long Island Rail Road and Lower Manhattan.

But however worthy, none should move forward if the MTA cannot also continue its robust program to rebuild the existing system. New York should not go the way of London, which built a new subway line while letting its fabled Underground deteriorate.

New revenue sources are desperately needed to rebuild and to maintain fares and service at attractive levels. More than ever, we need business, labor and civic leaders and — most of all — the riders to speak up for transit.

Will Governor George Pataki and Mayor Michael Bloomberg save transit riders from having to pay more for less? Will the governor and the mayor continue 25 years of transit reinvestment and rebuilding? The odds are much better if riders ask them to.

A new round of victories would be the best way to celebrate what riders have done to win the rebirth of city transit over the last 25 years.

Gene Russianoff is staff attorney for the Straphangers Campaign.

“The Riders and the Rebirth of City Transit: 25 Years of Advocacy by the NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign” is on display at the Municipal Art Society until October 30.

Getting to the Airport

|

|

Several times a day, Wen Yen does something that many New Yorkers dread doing several times a year: he goes to the airport.

Yen has been working as a driver for a car service since 1993, trading pointers about shortcuts with other drivers, and developing his own routes and alternative routes as he shuttles passengers to and from Newark, La Guardia, and JFK.

Mainly, though, he gets stuck in traffic.

JFK is the worst of the three airports, thanks to crowded highways and poor parking facilities, but he says they are all pretty bad.

People like Yen have no choice but to travel to JFK - he drives wherever his company dispatches him - but companies like Nippon Cargo Airlines have more and more alternatives. When it was faced with a decision to send some of its flights into JFK or into Chicago's O'Hare Airport, it looked at how easy it would be to get trucks to both destinations. The company chose Chicago.

"I've had several trucking companies tell me that sometimes... it takes four hours to get from Fort Lee [New Jersey] to Kennedy Airport," said Peter Disenbach of Nippon Cargo. "When you're paying a truck driver $20 an hour, that's pretty expensive."

Getting to and from the airports is the number one issue affecting airports that were once indisputably on top.

"We're competing with so many other airports... that it's no longer guaranteed that La Guardia and Kennedy will maintain their dominance in this industry," said Jonathan Bowles, research director of the Center for an Urban Future, a local think tank that has long been advocating for airport improvements.

There are promising signs, though. The Port Authority has increased its capital investments in New York's airports, and the city is looking into improving the airports, using them to spark economic growth. In what is being touted as a good first step toward addressing the airports' transportation needs, a new Airtrain to JFK opened last year.

Most recently, Governor George Pataki has been among those advocating for a $6 billion rail linking lower Manhattan with the Long Island Rail Road and JFK. The plan's supporters describe it as the long sought one-seat ride from the airport to Manhattan. But skeptics question whether the project is the best way to solve the airports' problems - or spend the city's cash.

STRUGGLING AIRPORTS

New York is regularly named one of the country's best tourist destinations. When tourists get to the city, however, they face what respondents to a readers' poll last year in Conde Nast Traveler magazine designated the worst airport in the country: JFK. The same poll found La Guardia to be the fourth worst.

Aging terminals, long delays, and, above all, terrible transportation to and from the airports, have marked the decline of New York's airports, once seen as some of the country's best. The conditions have driven away business: JFK, the seventh busiest airport in 1991, is now 11th. La Guardia dropped from being the 15th busiest to the 20th busiest airport in the nation.

Troubling trends at the city's airports were aggravated by the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. In the first year, 10,000 airport jobs disappeared - the worst job loss of any sector in the city's economy after 9/11. The drastic decline in the airline industry nationwide tightened the market, increasing competition and further exposing the shortcomings of the city's airports.

Doubtless, there will always be passengers for JFK and La Guardia airports. But as passenger airlines and air cargo industries grow, the city may lose the benefits of this growth to its competitors.

NEWARK AND NEW YORK: COOPERATING OR COMPETING?

In recent years, Newark International Airport has undergone a $3.8 billion renewal, which was topped off in October 2001 by the opening of the Newark Airtrain. The new system, by connecting to New Jersey Transit, allows passengers to get from Penn Station to the airport in 20 minutes, and then to individual terminals in another 10 minutes.

Obviously, this benefits New Yorkers, who can get to the airport much quicker than they were able to in the past.

"New York City benefits by having all three airports available, regardless of which state the passenger takes off from, just as New Jersey benefits from having the two Queens airports available to them," said Jeffrey Zupan, senior fellow for transportation at the Regional Plan Association.

But New York's neighbor is also its biggest competitor, and the city does lose out in the form of jobs and tax revenues if business goes to Newark instead of La Guardia or JFK.

Between 1989 and 1999, for instance, the Port Authority focused on improving Newark's terminals and transportation, allowing that airport to increase its workforce by 79 percent. Over the same decade, the number of jobs at La Guardia increased by only 14 percent, and JFK actually lost nine percent of its jobs.

Because the improvement of Newark has been accompanied by decline at JFK and La Guardia, many have accused the Port Authority - which manages all three airports - of playing favorites. Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani was so convinced that the Port Authority's approach was harmful to the city that he tried to seize control of JFK and La Guardia.

The Port Authority - which recently renewed its lease of JFK and La Guardia under terms that will give the city much more in rent - responds to accusations of favoritism by saying it spends its funds where they are needed most. In recent years, the agency has shifted capital investment back across the Hudson.

"I think it may be that things go in cycles. Newark had this great potential for growth, and the Port Authority had to help accommodate that growth. But in doing so, Kennedy and La Guardia were neglected," said Bowles. "The Port Authority has turned its attention to the New York airports."

IMPROVING TRANSPORTATION

In looking to improve the city's airports, the Port Authority's most obvious challenge is improving access. Public transportation to the airports is poor and underused; a 2002 report by the Federal Transit Administration found that only eight percent of JFK passengers used public transportation (in pdf format), while five percent of La Guardia passengers did. Most rely instead on congested highways.

JFK's problems are much worse than those at La Guardia, causing it to lose its spot at the country's top air cargo location.

The airport was the world's busiest air cargo hub until 1990; today it's the country's fifth. While transportation is not the only reason for this decline, many in the air cargo industry cite it as the most serious problem facing their businesses in New York City.

There have been calls for modest changes on the highways surrounding JFK for years: closing some exits at certain times of day, allowing commercial vans onto the Belt Parkway (all commercial traffic is currently banned), or adding a lane to the Van Wyck Expressway to reduce gridlock. Some advocates believe tolls on the Van Wyck, coupled with better public transportation, are the answer.

These changes would probably make personal travel from JFK more pleasant and commercial traffic more profitable. But no movement has been made on these proposals; there is little political will for any tampering with the city's highways.

More politically palatable are ideas that would create better rail lines, which would take riders off the highways and, theoretically, reduce highway congestion. As an ultimate solution to JFK's transportation woes, advocates have long called for the creation of a so-called one-seat ride, which would take passengers to Midtown without having to change trains.

The Airtrain

The Port Authority completed the JFK Airtrain in late 2001, a project that came after decades of debate and does not provide a one-seat ride to Manhattan. After almost a year in existence, the Airtrain is nearing its goal of 34,000 daily riders. The majority of these passengers use the Airtrain not to get to and from the airport, but to get around the airport itself. Those who connect to the subway pay five dollars to use the Airtrain; those who use it to travel around the airport itself do not have to pay a fare to do so.

This has fed the argument of those who say the Airtrain is irrelevant for Manhattanites, who have to take the subway to far-off stations in Queens and walk prodigious journeys before boarding it. This debate was one of many that raged over the project in the decades between its conception and completion. Besides being expensive - it cost $1.9 billion, paid for in part by the Port Authority and in part by a surcharge on airfare - the project generated rigorous opposition from local communities.

Such opposition is common for the ambitious transportation projects that many believe are the only way to solve the airports' transportation problems. In Astoria, Queens, community opposition caused a plan to extend the N or R trains to La Guardia to be scrapped entirely. The Airtrain itself barely passed the city's review process.

The project's supporters acknowledge that it alone cannot put a serious dent in the transportation problems at JFK.

"I know the project's been criticized for not being a one-seat ride to the airport and therefore less appealing to non-business travelers and the like," said Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Union, a transit advocacy group that backed the project. "But it's a good first step, and hopefully in the long run we'll see a one-seat ride, at least to midtown."

Rail Link to Lower Manhattan

Tapping the post 9/11 attention on lower Manhattan, Governor Pataki and downtown business interests have been pushing to build a rail link from JFK and the Long Island Railroad, through downtown Brooklyn, and into lower Manhattan.

Before 9/11, proposed one-seat rides always terminated in Midtown. Many do not see a connection to lower Manhattan as anywhere near as useful.

The plan calls for an expensive new tunnel under the East River, and will cost a total of $6 billion. The governor's idea of paying for the project from the pool of federal grant money for rebuilding after 9/11, met tough opposition from others who had believed those funds would be better used for other purposes. Pataki has since changed course, convincing President George Bush to support converting $2 billion in unused tax credits - also part of the federal post 9/11 aid - into cash for the project. Congress still has to vote on the funding plan, and even if it does approve it, it is unclear exactly where the remaining funding will come from.

Supporters of the plan see its major feature as connecting lower Manhattan to the LIRR, spurring the downtown economy; but also describe the one-seat ride to JFK as a way to bring the airport back to the cutting edge.

The rail link "will position New York alongside other world-class cities that already have such seamless global access," said Pataki in a speech this May.

But skeptics abound, saying that the likely number of riders doesn't justify the price, and that the project overstates the economic benefit for lower Manhattan. Some see a threat to the funds needed for a 2nd Avenue subway; others fear the deterioration of the existing transportation system as capital is spent on ambitious new projects.

Whether this skepticism can be turned into support may rest on how the rail link connects to existing transportation systems: if it can be made compatible with city subways; how well stops between JFK and the World Trade Center Site serve local areas; and whether it is built to connect to any future 2nd Avenue Subway. With the project in preliminary stages, the answers to these questions are still unclear.

BUILDING ON POTENTIAL

The airports' shortcomings haven't completely hampered the ability of airlines to succeed in Queens. JetBlue Airways, a low-cost airline that is now the leading carrier out of JFK, brushed aside high real estate prices and poor transportation to set up operations in New York City.

David Neeleman, the company's CEO, was met with skepticism when he decided to anchor his company in Queens. Today, JetBlue's success has been a rare one in an airline industry struggling in recent years.

"The remarkable thing when you look at JetBlue… is that we operate out of one of the most expensive airports in the world," Neeleman told investors this summer. "Being able to be in New York…the largest travel market in the world, and being able to be efficient and use those costly assets wisely is one of our greatest secrets."

The airline is currently looking to expand at both JFK and La Guardia.

Further, the Federal Aviation Administration projects that the air cargo industry will grow by five percent every year until 2014, with international shipping appearing particularly strong. Due to its extensive experience in international shipping, JFK is particularly well suited to capture this market. Improvements over the last few years have put it in an even better position.

Through the efforts of the Port Authority, the city, and individual airlines, JFK has undergone significant changes. Several terminals have been torn down and rebuilt, much-needed warehouse space has been added, and numerous aesthetic improvements have been made.

Businesses operating out of JFK say that the improvements have made a difference. And, transportation problems aside, JFK is still a major stop for most airlines.

"It's in the center of the East Coast market ... obviously it's a major point for us," said Disenbach of Nippon Cargo, noting that the company has made long term investments in its own building at JFK. "We're going to stay here and make it work."

Proposed Fare Increases And The Cut In City And State Aid

When the Metropolitan Transportation Authority released its budget proposals this summer, the newspaper headlines focused on the proposed fare and toll increases. But more general funding and service issues loom just as large.

The MTA proposed a $6 increase in the $70 monthly unlimited ride MetroCards and a $3 increase in the $21 weekly passes. It also proposed a 50-cent increase in tunnel tolls (currently $3.50) and a $2 increase in the $4 fare for express buses. Metro-North and Long Island Rail Road fares would rise by about five percent. The fare and toll increases and cutbacks in some transit services will be voted on by the MTA Board in December and take effect sometime in 2005. The base subway fare of $2 would be unchanged, as would the discounts for buying at least $10 in fare value at a time.

Fare and toll increases, combined with service cuts, would eliminate the $436 million MTA budget gap in 2005. There remains a $695 million deficit in 2006 and larger deficits in later years. MTA executives say that another fare increase might be necessary in 2007.

The MTA also released a $27.8 billion five-year capital program for 2005 to 2009. While most of this vast sum goes toward maintaining the existing transit system, funding is also included for much-needed system expansion projects including the Second Avenue Subway, a link to Grand Central Terminal for LIRR riders and a rail link between JFK Airport and lower Manhattan.

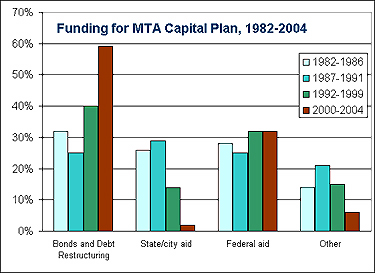

The need for another fare increase, coming on the heels of across-the-board fare and toll hikes in May 2003, shows how capital spending is related to fares. In a departure from past practice, capital spending over the past five years was funded largely by borrowing. A recent Regional Plan Association study reported that 59 percent of the 2000-04 capital program was funded by bonds and debt restructuring, up sharply from 40 percent for the 1992-99 period and 25 percent from 1987 to 1991. Payments on the increased debt load are putting pressure on the MTA budget and leading to the need for fare and toll hikes every couple of years.

The MTA's reliance on borrowing for the 2000-04 capital program was forced by cutbacks in state and city aid. The figure below shows that state and city aid covered only two percent of the 2000-04 capital program, down from about 30 percent a decade ago.

Source: Regional Plan Association

No one questions the importance of finding the money for maintaining and even expanding the current subway, bus and commuter rail system. And, despite the appeal of the expansion projects, no one doubts the critical necessity of maintaining the existing system. As former MTA Chairman Richard Ravitch, who put together the MTA's first capital program in the early 1980s that brought the transit system back from the brink of collapse, said to the New York Times, "The highest priority must be the capital maintenance of the existing system. Otherwise, the subway system and commuter rail system are going to start down the slippery slope again."

Transit advocates have long called on the state and city to resume their support of MTA capital spending. Elliot Sander, director of the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University, told the Daily News, "When the system was rescued in the 1980s, the state and city provided key financial support. They have now walked away." Gene Russianoff of the NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign, put the responsibility squarely on the governor. "If there is a fare increase," he said, "it has a name: It will be the George E. Pataki fare increase."

So where will the money come from? The experience with previous proposals for various funding sources, from a voter-rejected bond act to tolls on the East River bridges, is not encouraging. Neither the governor nor mayor want to increase taxes. The MTA was heavily criticized during last year's fare increase proceedings.

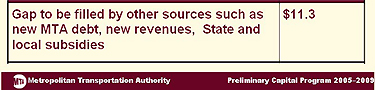

Given this backdrop, no one is talking about specific funding sources. The MTA's Powerpoint presentation on the capital program notes dryly:

The RPA report calls for "dedicated revenues" from the state, city and suburban counties and long-term subsidies from the state without providing specific recommendations. Others are even less specific. Katherine Lapp, MTA executive director, said, "The great debate will be how this need is met." Mayor Michael Bloomberg said, "We think that there are other alternatives that haven't been explored, and we wanted the staffs to do more work." A spokesman for State Comptroller Alan Hevesi told the Times, "You can see that there are some fundamental issues, particularly in terms of growing debt service. It's clear [the MTA] can't really count on something to magically come along and solve the problem."

The capital plan goes to Albany for approval and consideration of funding issues. It is anyone's guess how the governor and legislative leaders, who just now approved a state budget that was due in last spring, will address the funding challenge.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Transportation

|

Three Years of Rebuilding: |

A new sense of urgency and an influx of $4.55 billion in federal funding specifically earmarked for transportation has resulted in a wealth of ideas about transforming the way that people get around in lower Manhattan.

9/11 inspired New Yorkers to discuss ambitious transportation projects. In the past years, two connected stations in and around Ground Zero have been designed. The Ground Zero transportation hub will replace the PATH station that was destroyed.

Though underground walkways, the station will also connect to a new Fulton Street Subway Station, which itself will connect 12 subway lines that spread about 1,000 feet from east to west. The $750 million Fulton Street Station is scheduled for completion by 2007; the $2 billion transportation hub by 2009. Federal rebuilding funding will be used to fund both projects.

Other plans do not have such a clear future. Governor George Pataki has alternately spoken of using the money to bury West Street - a plan from which he has recently retreated - or to build a tunnel underneath the East River, connecting lower Manhattan to the Long Island Railroad and JFK International Airport.

The rail link plan got a boost recently when President Bush said that he supported converting unused tax incentives into cash for such a project. Congress has yet to approve the plan, but if it does, it will be a boon for the city, as it seemed unlikely that it would have been able to use the incentives themselves.

For more, see the Transportation section of Rebuilding

Next Page: Economic Impact

Urban Issues: Mass Transit

URBAN ISSUES - MASS TRANSIT

• • • • • • •

• • • • • • •

George W. Bush

In 2002, President Bush guaranteed an increase in the Department of Transportation budget, with $486 million earmarked for expansion projects in mass transit. The Bush administration provided Amtrak with $521 million to continue operating.

In December 2003, the Department of Transportation announced $2.85 billion in grants to build a new PATH terminal, connect 12 subway lines in a new Fulton Street subway station, and replace the South Ferry subway terminal in lower Manhattan.

John Kerry

Kerry supports giving cities options on how they spend federal transportation money, including projects for light rail, streetcars, and redesigning streets and sidewalks. (Learn more)

• • • • • • •

Back to Urban Issues Main Page

• • • • • • •

GOTHAM GAZETTE’S RELATED ARTICLES

• Urban Agenda: Mass Transit

• How New Yorkers Get to Work

• New Subway Projects and their Benefits

• Same Projects, No New Money

• Debating Transportation in Lower Manhattan

• Permanent PATH Station

How Disruptive Will The Convention Be?

How easily can New York absorb 50,000 delegates, dignitaries and press representatives for the Republican National Convention being held from August 30 to September 2 in Madison Square Garden?

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the Democrat-turned-Republican who enticed the Republicans to hold their national political convention in this Democratic stronghold, says, "The disruption will be a little bit annoying, but minimal." The mayor declared that, "If you don't live or work in the garment district, you won't even know that there's a convention in town."

Clearly, the mayor has a good point. My own experience during the 1992 Democratic National Convention was that from working on 42 Street, the only difference was the bright lights barely visible eight blocks to the south. Nevertheless, a lot of people do in fact work or live near Madison Square Garden, including 600,000 people who use Penn Station every day.

Perhaps the most visible disruption will occur for commuters exiting and entering Penn Station, which is buried under the Garden, during rush hour. Only two exits at the station, which serves Long Island Railroad, New Jersey Transit, Amtrak and several subway lines, will remain open. These are the main entrance on Seventh Avenue and the LIRR entrance on 34 Street. Station and subway entrances that are midblock between Seventh and Eighth Avenues and on Eighth Avenue will be closed for security reasons.

Penn Station exit closures mean that commuters will have to squeeze into two exits that are already jam packed at rush hour. The New York Times reported that railroad officials counted current passenger flows and found that two-thirds of Penn Station users already use the Seventh Avenue and 34 Street exits and the rest used the six exits that will be closed. Since ridership is normally down 10 percent in August, this means that the two exits will have to accommodate about 33 percent more commuters than normal. Given the normal level of crowding, that will be a challenge.

New Yorkers are famously adaptable and perhaps there will be less of a problem than these numbers suggest. Already, some commuters are planning their vacations to coincide with the convention. Others may avoid Penn Station by deboarding the LIRR in Queens and taking the subway into Manhattan. NJ Transit passenger flows will be lessened since Midtown Direct rail lines will be diverted to Hoboken during the convention, affecting 11,000 weekday rush hour commuters.

Subway and bus riders will also be affected. Bus lines on Seventh and Eighth Avenues will be diverted for the 13 hours that the convention is in session, primarily in the evening. Effects on subway service remain to be seen. Preliminary plans call for police officers accompanied by bomb-sniffing dogs and hand-held chemical detection devices to sweep subways and trains one stop before they reach Penn Station during the hours of the convention. The police will be checking for suspicious packages and terror suspects, according to Newsday. Thorough checks could substantially delay train service on both the subway and commuter trains, which perform a delicate and carefully timed dance to get into and out of Penn Station as quickly as possible.

And finally, what about transportation for convention delegates and the press? They will have more choices than the typical New Yorker. The Republicans plan to use 200 buses to shuttle delegates, dignitaries and reporters to and from Manhattan hotels. Buses will be whisked into Penn Station on specially coned-off lanes. But the bus is not the only option. Corporate sponsors are donating MetroCards to be given to each delegate. In addition, most of the hotels are in Midtown, within walking distance of the convention. Delegates' choice of bus, subway and walking is much like the choice locals make every day. How Republicans choose will depend partly on how much of a New York experience they want to have during their stay in the city.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

The Rail Freight Tunnel

Another big transportation project moved a step forward in May with release of a draft environment impact report on a rail freight tunnel between Brooklyn and New Jersey. The $20 million study, commissioned by the New York City Economic Development Corporation during the Giuliani Administration, found that a 5.5 mile cross harbor tunnel from Sunset Park in Brooklyn to Greenville Yard in Jersey City would improve the movement of goods in the region, spur economic growth and reduce both air pollution and traffic congestion.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler of Manhattan, who has pushed the project for years, supported by Senators Charles Schumer and Hillary Clinton, are seeking $1.4 billion in federal funding from the federal transportation bill now under consideration by a Congressional conference committee. If approved and funded, construction would start in 2008 at the earliest.

Freight transportation is a major issue in the New York region, although it receives much less public attention than auto travel and transit issues. The region is highly dependent on trucks for the movement of goods, and those trucks obviously encounter the same traffic congestion and unpredictable travel times as every other vehicle encounters on the highways and streets of the region.

This congestion drives up the costs of living and doing business in New York, and is thus an important impediment to the economic development of New York City and its suburbs. These costs are typically bundled into the costs of products and services, however, and thus hidden from the consumer. Occasionally the higher goods transport costs become apparent. As a personal example, I once found that it cost twice as much to ship a large skylight from California to Brooklyn than to the New Jersey suburbs - illustrating that goods shipment across the Hudson is particularly affected.

These problems are only going to worsen over the next several decades. The cross harbor freight tunnel study projects that overall traffic volumes will increase 47 percent for Hudson River bridge and tunnel crossings between 2000 and 2025 and by 25 percent for East River crossings.

Although the New York region developed in the heyday of railroads, remarkably little freight uses the rails. While 79 percent of regional freight movement (measured by weight) is by truck and 15 percent is waterborne, only 5.6 percent moves by rail. Furthermore, rail transportation accounts for only 1.6 percent of freight tonnage east of the Hudson River.

A major impediment to increasing the share of freight using rail transportation is the lack of direct connections across the Hudson. The closest rail bridge is in Selkirk, New York, 140 miles north of the city. A new rail tunnel connecting Brooklyn with either New Jersey or Staten Island could use the substantial capacity of existing rail lines in Brooklyn and Queens.

The environmental study favored building the tunnel to New Jersey instead of Staten Island due to lower cost, less environmental impact and offering better rail connections. The Staten Island tunnel alignment would require more circuitous routing for some trains to reach the Staten Island portal, and would thus attract less cargo than a New Jersey connection.

The study recommended further consideration between a single-track tunnel versus double-track tunnel to New Jersey. The single tunnel would cost $4 billion versus $7 billion for a double tunnel and would have lesser adverse environmental and neighborhood impacts. But a single tunnel would also divert less truck traffic from congested roads and bridges and thus produce lower benefits than a double tunnel. The single tunnel would divert 5.4 percent of all truck cargo, compared with 8.5 percent for a double tunnel.

Diversion of freight from truck to rail would obviously reduce traffic volumes and traffic congestion throughout the New York region. A single tunnel would reduce truck travel by three percent in the region while a double tunnel would produce a 4.5 percent reduction.

A cross harbor tunnel would have the most impact on commodity trucks - think of the big tractor trailers - using Hudson River crossings. Commodity truck traffic would decline by up to 11 percent on Hudson River crossings overall, and by up to 18 percent on the Verrazano Bridge.

While this is good news for New Jersey, Staten Island and Westchester, the effects are a bit different for Queens. Since rail freight would be transferred to trucks in Queens, truck traffic would increase on Queens roads and bridges. Commodity truck volumes would increase as much as 41 percentin the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, for example, as well as on major highways.

While a cross harbor tunnel would have major impacts on the volume of commodity truck trips, overall effects on traffic congestion would be extremely modest. Commodity trucks represent only 1.9 percent of all vehicles using the Hudson River crossings and 0.7 percent using East River crossings. Thus, total traffic volumes would fall by only as little as 0.1 percent on Hudson River crossings, while increasing by the same range on East River crossings.

The major benefits from a tunnel are economic rather than traffic or air quality. Based on complex economic models that are typically used to assess major construction projects, the study estimates that a double tunnel would produce $10.28 billion in total benefits over its lifetime. Most of this figure comes in economic benefits measured as growth in personal income as the tunnel's improvement to freight movement results in costs savings for businesses, spurs growth of existing businesses and attracts new companies to the region. The study projects $7.5 billion in growth in personal income over the life of the project, measured in constant 2002 dollars. Some of this is in the form of direct benefits (e.g., the incomes generated by new jobs). Also included in the $7.5 billion are so-called multiplier effects, attained as the money further circulates within the region. For example, if a new employee hires a babysitter, the babysitter's income is counted in the multiplier.

The study estimates that a double tunnel would produce $10.3 billion in benefits and $4.7 billion in costs, using 2002 dollars, for a 2.2-to-1 benefit/cost ratio. The ratio for a single tunnel is 1.9-to-1. Congressman Nadler points out that these ratios are unusually high for transportation projects.

While receiving scant attention from major New York media outlets, release of the tunnel study generated a lively debate in Queens and New Jersey. Queens newspapers focused on the loss of 44 to 52 businesses due to expansion of the West Maspeth rail yards, with possible loss of 1,200 to 1,400 jobs.. The tunnel would also attract additional trucks to the neighborhood. The Queens Chronicle quoted Gary Giordano, district manager of Community Board 5, saying that, "There are concerns with regard to increased truck traffic in that Maspeth industrial area. That's a big concern, as well as the pollution associated with that."

Although the study did not include solid waste as potential tunnel cargo, Jersey City officials assailed the project as a "trash tunnel." The Jersey Journal quoted Jersey City Mayor Glenn D. Cunningham saying that, "We do not need to be a garbage transfer locality for the city of New York."

The next step in the project is public hearings on the draft environmental impact statement in June. As with many other major projects -- including the Second Avenue subway, extension of the #7 train and linking the Long Island Rail Road to lower Manhattan -- the biggest stumbling block is funding.. It remains to be seen whether Nadler can secure partial funding from Congress.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Proposed Rail Link

Pushing ahead with plans to dramatically improve rail service to Lower Manhattan, Governor George E. Pataki announced his support this month for a $6 billion rail link from Downtown Manhattan to Kennedy Airport and Long Island. The project would create the long-sought one-seat ride from JFK to the World Trade Center area, and also provide a direct commuter rail service to Downtown for Long Island Railroad (LIRR) commuters.

The central part of the governor's plan is to construct a three mile tunnel from the Long Island Railroad's existing Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn, under the East River and terminating at Fulton Street in Lower Manhattan. There would also be a new 1,500 foot connector between AirTrain and LIRR tracks in Jamaica, Queens.

According to a fact sheet released with the governor's speech, the new line would provide 36-minute travel times from JFK to Manhattan, down from 55 minutes currently via the new JFK Airtrain and the A train. For Long Island Railroad commuters, the proposal would reduce travel time from Jamaica to Lower Manhattan from the current 36 minutes to about 21 minutes.

The LIRR service is expected to attract "up to" 100,000 riders per day; as many as 6,000 riders are expected to use the JFK connection daily. The line could be up and running by 2013.

Lower Manhattan business interests have pushed strongly for the rail link to create direct access to the suburban labor market. Currently, workers living in Long Island, Westchester and parts of New Jersey must take commuter rail trains into Midtown and then the subway downtown. This is one reason that many businesses choose Midtown over Downtown in deciding where to locate or expand their offices.

As with the Second Avenue subway and other transit projects currently under consideration, funding is a major hurdle for the proposed tunnel and rail link. The Port Authority has at least $560 million lined up. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation could tap into $1.2 billion in community development block grants, although some downtown community groups prefer that the money be spent on housing, community services and cultural institutions. Senator Charles E. Schumer has said that he will fight to obtain transportation funding from up to $2.5 billion in unused tax benefits that were allocated as part of the $21.4 billion post-9/11 federal aid package to New York.

Transit advocacy groups were cheered that the governor opted for a new tunnel rather than using the Montague Street subway tunnel used by the M and R trains. Transit advocates feared that using a subway tunnel for LIRR and JFK trains would compromise existing subway service for New York City residents. Moreover, building a new tunnel under the East River creates the possibility of extending into Brooklyn the Second Avenue Subway, which is planned to terminate near Hanover Square (a couple of blocks south of Wall Street). Such an extension would improve access to the East Side for many Brooklyn residents. A new tunnel might also allow the E train to continue into Brooklyn.

The governor pledged not to allow the tunnel and rail link to compete with other projects for funding. Transit advocates, however, fear that a new tunnel will eventually compete with other projects, principally the Second Avenue Subway, for scarce dollars.

They also question the official ridership projection. Based on 1990 Census data, the LIRR carries about 40,000 work trips per day between Long Island and Lower Manhattan. Especially since it is questionable whether all Long Island Railroad commuters would use the new link, it is difficult to see how the "up to 100,000" ridership projection is realistic.

Another way to evaluate the LIRR link is to compare its costs and ridership with those of other major rail projects that are currently in various stages of discussion, planning, design and construction. In addition to the tunnel project, these are:

- Second Avenue Subway, which would run from 125th Street to Hanover Square.

- East Side Access, which will allow LIRR trains to deliver passengers directly to Grand Central Terminal.

- #7 line extension, which would extend the #7 train west from Times Square to 11 Avenue and then south to 33 Street.

The table below shows ridership projections and construction costs for each project (except that ridership projections are not available for the #7 extension):

|

|

Peak hour AM ridership |

Weekday ridership |

Capital cost |

Capital cost per daily rider |

Source (ridership and costs) |

|

Second Avenue subway |

85,900 |

723,000 |

$17 billion |

$24,000 |

Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

|

East Side Access |

Not avail. |

178,000 |

$6.3 billion |

$35,000 |

Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

|

LIRR link to Lower Manhattan |

Not avail. |

Up to 100,000 |

$6 billion |

$60,000 or more ($120,000 if ridership is only 50,000) |

Lower Manhattan Development Corporation |

|

#7 line extension |

Not avail. |

Not avail. |

$2.2 billion |

Not avail. |

Partnership for NYC |

This chart is a very rough cost comparison and does not take into account the economic development benefits that proponents say are major benefits from the LIRR link - though it should be noted that the Second Avenue Subway is expected to generate economic development in East Harlem and perhaps on the East Side. The chart also does not distinguish between additional ridership attracted by the construction of new capacity and simply shifting riders from one line to another. Nor does the chart take account of benefits in reduced crowding and travel time.

All that said, however, the comparison is a useful starting point to evaluate the relative merits of each alternative. Clearly, the chart highlights a central question - in terms of ridership, the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access show costs per rider of about one-half or even one-quarter of the LIRR link. It will be the task of proponents to show that the LIRR link to Lower Manhattan has separate funding sources, or that in the overall equation, it is a more beneficial project than the seemingly lower-cost Second Avenue and East Side Access projects.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

12,000 NYC Taxis; Five Are Accessible

While many New Yorkers worry that they may no longer be able to afford to take a taxi cab with the 26 percent fare increase that went into effect this month, a whole group of citizens here have to wonder if they will ever be able to hail a cab.

April was the cruelest month for disabled New Yorkers. Half the drivers of the Access-a-Ride vans on which so many people with disabilities rely for public transportation went on strike. When medallions for 300 new taxis were auctioned, no one who was willing to deploy a wheelchair-accessible vehicle made a high enough bid to secure a medallion, despite the hope that nine percent of the new cabs would be accessible. And a bill to make all new cabs accessible has yet to have a hearing, despite having attracted 38 sponsors out of the 51 City Council members.

"There's lots of prejudice and discrimination and that's why our issues are neglected," said Jean Ryan, vice president of Disabled in Action and a leader of the Taxis for All Campaign.

While all Metropolitan Transportation Authority buses were made accessible by 1995 after a concerted campaign by disability rights groups, the 100-year old subway system has been slow to install the elevators necessary to make it accessible. In addition, the Transit Authority has not solved the problem of bridging the gap between the platforms and subway cars that make boarding them difficult and dangerous for those in wheelchairs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act does not require that all taxis be wheelchair accessible if a city provides an alternative for the disabled. In New York, that "paratransit" alternative is Access-a-Ride, private van services that contract with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to transport people with disabilities from point to point in the city for the price of a bus or subway ride. It must be booked "one to four days in advance" and can involve long delays as many riders use the same van and are picked up from different points.

Many people who use wheelchairs can use conventional taxis, albeit with difficulty. The first problem is getting the cab to stop. It is a violation for cab drivers to refuse to stop for a person with disabilities, but some risk it. I've witnessed cabs speed up after pausing and seeing that the potential fare was in a wheelchair. I once hailed a cab for a colleague in a wheelchair and when the driver was loading the chair into his trunk, he was muttering curses at "you cheap handicapped people who don't tip." My colleague bore the insults, as he desperately needed the ride.

I'm 50 and temporarily able bodied, but at 6 feet tall I have trouble getting in and out of the older New York cabs-and I do not mean the sorely missed Checker cabs that could sit five comfortably in the rear. Maneuvering out of a wheelchair into a cab is infinitely more difficult and many disabled people cannot manage it, even with help from the friendliest of drivers. They need to be able to stay in their chairs and roll them into the cab.

In London, where the taxis have always been more consumer-friendly, all taxis have been required to be accessible since 1989 and the passage of the Disability Discrimination Act of 1995 added the requirement that new taxis had to be designed so wheelchairs could roll right into the car. As the New York Times reported in a Travel Section feature in April ("Rolling Along in London"), accessibility is not perfect among London cabs due to some ramp malfunctions, but they are light years ahead of New York.

In New York, just five out of more than 12,000 cabs are fully accessible to people in wheelchairs. In these van-like cabs, a person in a wheelchair can roll right in through the back door using a ramp.

Local Law 496-A enacted by the City Council and Mayor Mike Bloomberg in July 2003, authorized 900 more taxi medallions (in part to close a budget gap) and was billed as "mandating alternative fuel and fully accessible taxis." "By providing that nine percent of the vehicles from each sale are accessible, we are reaffirming our commitment to providing transportation to persons with disabilities," said Bloomberg at the time. But there was a loophole in the law that resulted in none of the first 300 new medallion cabs being accessible. That's because none of the bids for accessible cabs were less than ten percent of the lowest winning bid for the non-accessible cabs. Ryan of Disabled in Action called the promise of accessible cabs under this law "a sham."

Even before this failed plan was passed, Councilmember Margarita Lopez introduced a bill to require that when a taxi is taken out of service--as it must be after 3-5 years with rare exceptions--a wheelchair accessible vehicle must replace it. This bill, Intro 84, now has 38 sponsors but does not yet have the endorsement of Council Speaker Gifford Miller or Transportation Committee Chair John Liu (D-Queens).

"People believe there is a lot of money to be made" from owning a taxi, said John Gresham, an attorney with New York Lawyers for the Public Interest who is fighting for the passage of the accessible cab bill. "They have access to cash and medallions are going for record prices, so now is the time to do this bill." When asked why his group has not sued over the lack of accessible taxis, Gresham said, "We believe the most direct way to get where we need to go is through action by the Council."

Advocates have met with Liu, but he said that he has "severe issues" with the bill, while acknowledging that the lack of accessible taxis is something "that should not be." He said, "I don't think you can make a requirement to force a manufacturer to make" accessible taxis. "If the manufacturer makes them, New York City should lead the way" in deploying them, he said. Wouldn't manufacturers produce them if New York required them? "I think we have to be reasonable when we make these kind of requirements," he said.

After speaking with Gotham Gazette, Liu told the Daily News, "The City Council will be putting together legislation that will require yellow cabs - as the older vehicles retire - to be replaced with new vehicles that will be accessible to people who use wheelchairs." But he later said that he is not in support of Intro 84 because it doesn't deal with "clean air" issues and it is a "total renouncement of the budget agreement."

While he told the News that full accessibility could be accomplished "in a matter of three to four years," he later said he was not sure "how quickly" it could be done.

"We want this bill within a few weeks," said Ryan. Liu has agreed to continue to meet with advocates of the accessible taxi legislation to see if a compromise can be worked out.

Gresham noted that Chicago has made one in fifteen cabs accessible, "but you can call for a cab there." Similar progress has been made in Boston, Las Vegas, Denver, Boulder, and Ann Arbor.

"We've learned one very important lesson from the wealthy New York City taxi medallion and fleet owners: it's going to be one hell of a fight," wrote Terry Moakley of the United Spinal Association as well as the Taxis for All Campaign. He was one of the leaders in the fight in 1985 to make New York the first city in the world to make all its buses accessible.