42nd Street Trolley?

Should trolleys – now re-christened as “light rail” – return to 42nd Street for the first time since they were replaced by buses 59 years ago? The idea, which has been around for at least two decades, was approved by the City Council in 1994 but died when then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani withdrew his initial support.

A private group of urban and transportation planners and architects, calling itself vision42, resurfaced the idea of a 42nd Street light rail line recently with the release of a set of planning and economic reports. The reports, funded by an anonymous donor, set out an ambitious vision for 42nd Street as a tree-lined, pedestrian-friendly enclave running from river to river. Train tracks would be installed on a landscaped pedestrian boulevard. Unlike the 1990s plan approved by the City Council, the street would be closed to traffic. Futuristic low-floor light rail vehicles would replace taxis, buses, trucks and cars that now dominate the street. This famous east-west artery in Manhattan would join Fulton Street in downtown Brooklyn and Nassau Street in lower Manhattan as car-free streets.

Making The Dollars And Cents Argument

While all of this might sound much too nice to be New York, the advocates of the proposal, which would cost up to a half billion dollars to construct, make a dollars and cents case for light rail on 42nd Street. They start by computing time savings gained from replacing buses with light rail. A commuter traveling from the Port Authority Bus Terminal to Fifth Avenue, for example, would save up to five minutes on their commute.

In Manhattan, time is money. Office and commercial space that is closer to transit lines is more valuable than space further away. That simple observation is the basis for Mayor Bloomberg’s proposal to extend the #7 train to the West Side. Time savings from a 42nd Street trolley would mean that property values for owners of offices, retail stores, residential buildings and vacant lots would increase by a whopping $3.5 billion, according to the economic study prepared by the consulting firm Urbanomics. The largest benefits would occur between First and Third Avenues, with property values also rising along Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

Rising property values are also good for New York City and New York State, which are projected to take in $277 million in additional taxes annually from property, personal income, corporate franchise and commercial rent taxes.

|

An illustration of the "light rail." |

The vision42 group presented the light rail studies at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in Times Square earlier this month. Questions about the studies came primarily from area residents who were concerned about increased traffic on surrounding streets and access to parking garages.

The traffic study projected that traffic impacts would be greatest west of Sixth Avenue on 40th Street and 44th Street during the morning rush hour. These streets would absorb traffic from the Lincoln Tunnel and West Side Highway that now uses 42nd Street. During the afternoon rush hour, traffic impacts would be heaviest on Eighth and Tenth Avenue with some but lesser impacts on 40th, 43rd and 44th Streets.

Notably, area residents took little note of possible benefits to them, which would be especially pronounced to those who live several blocks from the nearest subway line -- perhaps in part because presentations focused on benefits to commuters.

The primary construction cost is moving the utilities that lie underneath the street. As one might imagine, 42nd Street is not only a main conduit for traffic but also for sewer, water, telephone, electrical and gas lines. There are even abandoned trolley ducts under the pavement. Utilities need to be moved so that future utility cuts do not interrupt light rail service. Also, the vibrations from the trains can cause damage to some utility lines.

Utility relocation is an expensive proposition – estimated by an engineering firm at $319 million of the $510 million cost of construction. It might be possible to relocate only some of the utility lines, reducing the relocation costs to $189 million, but that figure would still be about one-half of total construction costs.

Why Not A Bus?

The costs of utility relocation raise the question of why not use rubber-tired vehicles instead of light rail vehicles that rely on tracks? With huge increases in bus ridership since the MetroCard free transfers between buses and the subway took effect, haven’t New Yorkers proven that they will ride buses? Without tracks to worry about, a car-free bus mall would not require any utility relocations. Another advantage is that 42nd Street could be integrated with bus routes on North/South avenues. New York City Transit could run a bus rapid transit service on First and Second Avenues, for example, that would turn onto 42nd Street – a useful step until the Second Avenue Subway is built.

George Haikalis, a transportation planner and co-chair, with the architect and author Roxanne Warren, of vision42, cites several advantages of light rail over an improved bus service. Haikalis fears that without rail tracks, some vehicles will be allowed onto 42nd Street, and those vehicles would block the bus lanes – a problem that certainly does occur at times on Fulton Street in Brooklyn. Haikalis also cites the smoother ride of light rail vehicles over buses and that low-floor light rail vehicles do not need the large wheel wells of low floor buses. Passengers also like the certainty that rail vehicles will stay on the tracks and not unexpectedly divert to some unpredictable destination, a consideration that affects visitors more than residents or commuters.

What Needs To Be Addressed For It To Happen?

Many other issues would need to be addressed if the light rail plan moved forward. Further work is needed on traffic issues, deliveries to buildings on 42 Street and related implementation issues. More basically, who would fund the project? Who would operate the service – the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the city, or a private company franchised by the city (as was the plan a decade ago)? Could riders use MetroCard to pay the fare – and how would the “proof of payment” system proposed for the line work in a New York environment?

Does a 42nd Street trolley have a future? Currently it lacks any depth of support in the civic community, which is focused on the Second Avenue Subway, East Side Access and lower Manhattan redevelopment. Mayor Bloomberg is focused on extending the #7 train, building the Jets Stadium and winning the Olympics. Although Manhattan Borough President Virginia Fields sponsored the recent meeting, she has not endorsed the project, nor have other elected officials or the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

The 42nd Street light rail may need to wait a while before its day comes, if it ever does. In the meantime it will be yet another example of how many stars need to align before even a relatively modest transit construction project moves toward reality.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

The State Budget's $38.5 Billion Transportation Program

The on-time New York State budget approved by the legislature on March 31 included a $38.5 billion transportation program covering the next five years, to be split equally between transit and highways.

Legislative approval – assuming the governor does not use his veto pen to make any substantial changes – means that the Second Avenue Subway and the Long Island Rail Road link to Grand Central Terminal will begin construction. The budget also means that the transit system will continue to be maintained and upgraded, although possibly with a stretching out of some projects. It also means that while bridge and pavement conditions on state bridges and highways will not deteriorate, congestion will continue to worsen. Finally, the way the budget was financed means that in 2010, New York will face the same hard financing issues that it confronted this year.

Let’s look at how the $38.5 billion breaks down, starting with funding for the Capital Program of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and then the Highway Program of the New York State Department of Transportation. (NYSDOT).

MTA CAPITAL PROGRAM

System Improvements

Let’s start with the MTA’s “Core Capital Program.” The core program covers what is artfully termed “state of good repair” and “system improvements.” These refer to normal replacement and maintenance of rail cars, buses, tracks, signals, stations and the host of infrastructure items required to keep the subway, bus and commuter rail systems in good running order. The benefits of many “state of good repair” elements are readily seen by transit riders. New subway cars, for example, improve the riding experience and are less likely to break down.

But much of this program is unseen – until disaster strikes. The Chambers Street fire late last year illustrated the importance of modernizing signal systems, for example. Sometimes unnoticed, the system-improvement component of the program goes well beyond keeping the system in good repair. New train control and communications systems, for example, now being tested on the L line and scheduled for installation on parts of the F in the next few years, include signage that will announce when the next train will arrive.

Last September, the MTA requested $16 billion for the core program and $500 million for security, for a total of $16.5 billion. The legislature approved $15.4 billion. In discussions with the legislative leaders, the heads of New York City Transit and the commuter railroads apparently said they could live with the lower amount. How they will do so remains to be seen and thus, whether there are real impacts from this $1.1 billion reduction is unclear. The agencies may stretch out certain program elements, for example, or find ways to cut back on project scopes. Megaprojects

Next up are the widely-heralded expansion projects. These include the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access, which would bring Long Island Rail Road trains into Grand Central. The MTA requested $1.4 billion to begin construction of the first phase of the Second Avenue Subway, which will run from 125th Street to connect into the existing subway line at 63 Street. The MTA also requested $2.3 billion for East Side Access. The legislature approved $2.1 billion for the two projects -- $1.1 billion for East Side Access and $1.0 billion for Second Avenue. The $2.1 billion assumes that the federal government contributes $1 billion.

The approved funding level for these megaprojects means three things.

First, it means that the projects are moving forward. Construction will start during this Capital Program so you can expect that the Second Avenue subway will be built in your working lifetime (unless you are very close to retirement).

Second, don’t buy your tickets quite yet. The funding reductions mean that the projects will open somewhat later than had been planned. East Side Access will open probably in 2015 instead of 2011 or 2012. Second Avenue will also be pushed back, although it’s not clear how far or to when.

Finally, the way the funding is structured will create greater financial pressures down the road. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) requires that funding be identified up front before it approves federal assistance. In this case, state officials will request permission to “pay as you go,” having just enough money identified to meet the cash needs of the project. The federal agency appears likely to accept their request, although positive action is not certain. What this arrangement means, however, is that state officials will have to identify additional funding sources by the time the next Capital Program comes up for approval.

The legislature also approved $2 billion for the #7 extension, but that entire sum is to come from New York City sources. Finally, there is $400 million for the proposed rail connection between JFK Airport and lower Manhattan, a project that is still substantially unfunded.

MTA PROGRAM FUNDING

Transportation Bond Act

The most-publicized aspect of program funding is the $2.9 billion Transportation Bond Act that will go on the ballot for approval this fall. Proceeds from the Bond Act will be split equally between the MTA and the Highway Program.

Unlike in 2000, when advocacy and civic organizations were lukewarm toward a $3.8 billion Bond Act that failed to win voter approval, these groups are now solidly behind this proposal. They are likely to mount a strong publicity campaign to gain voter approval. The electoral calendar is also in their favor. The mayoral contest is likely to draw voters to the polls in New York City, where voters are likely to back the Bond Act by a large margin.

Tax and Fee Increases

The legislature also approved about $300 million in tax and fee increases to help finance the MTA program. These increases include a 1/8 percent increase in the sales tax, which will end up being 8.375 percent in the MTA service region after a temporary increase expires. The increases also include hikes in vehicle title fees and the mortgage recording tax.

Proceeds from these increases will leverage $4.2 billion in new bonds to be used in the MTA Capital Program.

Financing – A Fare Increase? Jets Stadium Sale?

The legislature also approved just over $3 billion in MTA bonds, a sum that is apparently in the MTA’s financial plan from last fall. Thus, as expected, the MTA’s debt burden will continue to grow, placing continued pressure on the fare. Warnings of a fare increase every two years could easily come to pass.

Other elements of MTA funding are $1.4 billion in asset sales (West Side rail yards/Jets stadium, Brooklyn rail yards/Nets stadium, and some other asset sales and revenues), the $1 billion from the federal government for system expansion, and several hundred million dollars in assistance from the city.

Looking Over A Cliff After 2010

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the financing is that only about $5 billion of the $17.9 billion program is continuing funding. In 2010, the MTA will once again be looking out over a cliff, wondering how in the world it can come up with roughly $12 billion for the next Capital Program. Once again, options will be to further increase the debt load, increase taxes, sell assets, etc. So, while the legislature has squeezed out enough funding to get the MTA through the 2005 to 2010 period, funding issues are by no means going away. Each time, of course, the issues become more difficult because some of the options were used up in the previous round.

HIGHWAY PROGRAM

In March, New York University released a report that I wrote assessing highway and bridge conditions and congestion levels in the New York area and capital funding needs for 2005-2010. The report showed that at current funding levels, bridge and highway conditions are likely to deteriorate and congestion will continue to worsen. The assessments of funding needs were striking – an additional $1.3 billion in the New York area alone just to prevent worsening of bridge and pavement conditions and a doubling of the program to meet a reasonable definition of “state of good repair.”

The governor proposed a $17.4 billion statewide program, although funding sources were identified for only $15.4 billion. The legislature approved $17.9 billion, matching the MTA program. (As the notion of matching took hold in Albany, highway advocates suddenly became advocates of transit funding as well.) With few details available, it is not clear how much of the $17.9 billion will be allocated to the New York area. Assuming allocations similar to historic patterns, however, it appears that the funding is barely sufficient to keep road and bridge conditions the same as they are currently.

That would leave only a few dollars for the “mobility” program, which includes added highway capacity, elimination of bottlenecks, bus lanes and similar steps to reduce congestion. While many New York City residents can avoid highway congestion by taking the subway, congestion is unavoidable for the movement of goods in the city and for most suburban residents. By not dealing with the problem, state officials are allowing congestion to be an increasingly significant drag on the region’s economy.

ASSESSING THE BUDGET

There are good reasons to be pleased with the Legislature’s transportation budget. The legislature provided sufficient funds to keep the transit system in good condition and prevent highway and bridge conditions from worsening. Two megaprojects, the Second Avenue Subway and LIRR link to Grand Central Terminal, are going to proceed. In a state where an on-time budget makes front page headlines, these achievements are worthy of praise.

But as Elliot Spitzer recently noted, the budget does not solve New York’s long-term financial challenges.

While coming up with the cash to start the megaprojects, for example, it leaves until the next round in 2010 how to pay for them fully. It loads increased debt on the MTA, ultimately to come out of fares paid by transit riders. And it fails to address long-ignored problems with congestion on the region’s highway network.

So while this budget can be seen as a step forward, the journey won’t be any easier from here.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Parking

Tavi Fields, a 25-year-old rapper, found the city's alternate side parking regulations more than she could handle. "I was going through a hard period of time for a while, where I slept in for most of the day," Fields told the Daily News. While she stayed in bed, her Lexis remained on the wrong side of the street. The result: 90 tickets now totaling $10,433, making her, by the paper's reckoning, one of the top 10 parking scofflaws in the city.

Most New Yorkers manage to avoid such a dubious distinction, but for the people who own the 1.9 million cars registered in the city, parking borders on an obsession. Its rules have spawned at least one novel, a guidebook, sitcom episodes, and two companies dedicated to helping New Yorkers outsmart traffic enforcement officers.

Parking presents elected officials with a quandary. Many New Yorkers with cars view a free space to park as a God-given right. But other New Yorkers, pointing to pollution and congestion from automobiles, object to any move that encourages driving. The city's need for revenue from parking further complicates the picture, along with politicians' natural reluctance to attract the ire of voters who get tickets.

These issues arise again and again - in the controversies over parking at the West Side stadium and the proposed Nets arena in Brooklyn and the debates over the future of city neighborhoods. (See related stories on Flushing and Bay Ridge.) The latest imbroglio is an election year tiff over the use of parking meters on Sunday, which the mayor's critic dubbed "pay to pray."

Most New Yorkers would say the problem is too many cars chasing too few spaces. But some planners disagree. The problem, they say, is not that parking is too expensive, but that it is too cheap. And some say the problem is not that there are too few spaces but that there are too many.

THE HIGH COSTS OF CRUISING

Paying for space in a parking garage, George tells Elaine as they seek a space on an episode of Seinfeld, "is like going to a prostitute. Why should I pay when, if I apply myself, maybe I could get it for free?"

Many New Yorkers apparently agree, and so spend long periods of time driving, in concentric circles or zigzags, looking for parking.

Even the smartest among us do this silly chore. In a 2000 interview, Horst Stormer, a Nobel Prize winner in physics, described his formula for finding parking spaces by scooting ahead of rival drivers.

The average cruising time for a parking space in some New York neighborhoods approaches 14 minutes, according to a 1993 study. That's twice the time spent in San Francisco, where it is so hard to park that residents leave their cars on the sidewalk.

But cruising takes up more than time. Environmentalists cite a 1984 study that found drivers in one 15-block neighborhood in Los Angeles spent 100,000 hours cruising, wasting 47,000 gallons of fuel and producing 700 tons of carbon dioxide emissions in a single year.

New York's rules complicate the process. Moving the car from one side of the street to the other is not required in every city. And any single spot can have three sets of rules governing its use at various times.

Such parking regulations attempt to address a variety of needs, according to Michael Primeggia, the Department of Transportation's deputy commissioner for traffic operations. In most of the city, the main concern is street cleaning, which dictates the alternate side rules.

But in busier commercial areas, particularly in Manhattan, other considerations come into play, such as the need to accommodate traffic flow and allow for deliveries. "New York City is not so lucky that there can be one regulation that regulates the curb for the entire day," Primeggia said. And that leads to two or three signs - with different rules - for a single space.

A WALKER'S CITY, DAMAGED BY PARKING

Ironically, the city famed for its convoluted parking rules and parking headaches is the only American city where a majority of residents do not own cars. This gives rise to a chicken and egg debate. Do New Yorkers not own cars because it is so hard to park? Or is it so hard to park because New York remains a pedestrian and mass transit city that has not destroyed itself to accommodate the automobile?

The number of cars registered to New Yorkers has declined by about 5 percent since its peak in 2000. According to the 2000 Census, 54 percent of all New Yorkers -- and three out of four Manhattan residents -- do not own a vehicle.

But cars still clog Manhattan streets. Although the number of auto trips into Manhattan dropped after September 11, 2001, it has begun to grow again. Some experts predict it could reach 1 million vehicles a day.

A majority of people in Brooklyn and the Bronx do not have cars, but two out of every three Queens residents and four out of five Staten Islanders do.

By some measures (.pdf format) , New York is the second most congested - after Los Angeles - of America's largest cities. In 1990, the average speed of crosstown traffic in a car fell to 5.2 miles per hour. Brian Ketcham, a Brooklyn transportation consultant, estimated then that traffic cost the city nearly $30 billion a year in losses in employee productivity, accidents, air pollution, noise and roadway damage. And a 2004 study concludes that congestion cost the metropolitan area more than $7 billion in wasted time and fuel alone.

HALF A BILLION DOLLARS OF PARKING TICKETS

Many New Yorkers decide not to own a car at least because parking costs so much - particularly for drivers who get a lot of tickets. City drivers paid $537 million for parking violations in 2004. This came from some 10 million tickets, a 20 percent increase from 2003.

Primeggia says parking regulations are not designed to produce revenue or to confuse drivers. Any average citizen who reads English should be able to figure where and where not to park. When there is more than one sign applying to a space, the city puts the most restrictive sign on top. "All it takes is reading the signs in order and determining which sign is in effect," Primeggia said

But not everyone agrees. Louis Camporeale said he became aware of the faulty enforcement of traffic regulations in the 1980s. As a student, he would try to park at broken meters. "Three or four dollars in meter money was a couple of hours work," he recalled.

But sometimes the plan backfired, and he got a ticket -- an unfair ticket. (You can park at a broken meter -- but only for an hour.)

Such disputes led Camporeale to become an advocate for New York City parkers. He has written "The New York City Motorist's Guide to Parking" and runs a web site www.parkingpal.com with parking tips. "New Yorkers think they're so savvy, but when it comes to parking regulations, they're not," he said.

Glen Bolofsky, the author of the city's first alternate side parking calendar, now runs a business www.parkingticket.com that fights people's tickets - for a fee. Its successful challenges arise from confusing signs, mistakes on the ticket itself and other gaffes by the city. The company, which also operates in Boston, San Francisco, the District of Columbia and Philadelphia, claims that it won dismissals or reductions on 75 percent of the tickets it challenged last year.

"The rules and regulation are pretty much stacked against the average person," Bolofsky said. "The city goes out of its way to create a situation to intimidate and bully people."

Although the city consistently denies setting quotas for parking agents, Bolofsky disagrees. "The city budget dictates what the revenue [from parking tickets] is going to be," he said.

THE DEMISE OF THE PARKING LOT

People risk tickets to park on the street, though, because lots and garages cost so much - and the fees seem likely to rise even higher.

A reserved space in a garage in midtown cost $496 in 2004, the highest rate in the country, according to a recent survey. This has prompted some developers to offer parking condos where people purchase a space for tens of thousands of dollars and then pay a monthly fee.

But, despite this, lots are closing as New York's real estate boom makes land too expensive to park on. The city owns lots, but when the land becomes valuable, sells them for other uses. (See related story on Flushing.)

The same thing is happening with private lots. Broker Anne De Marzo told the New York Times that she has sold five parking lots and two garages in the Hudson Yards area with 20 more deals in the works. And Sean Sweeney, director of the civic group SoHo Alliance said he counted 2,000 parking spaces that had been lost in his area. Owners say they can sell their property for $350 for each "buildable" square foot.

POLITICS AND PARKING

In Calvin Trillin's novel about parking - "Tepper Isn't Going Out" �fictional Mayor Frank "Il Duce" Ducavelli sees his poll numbers rise after he goes after the "scofflaws in striped pants" - Ukrainian diplomats who did not pay their parking fees. Trillin obviously drew his inspiration from Mayor Rudy Giuliani's attacks on United Nations diplomats who parked illegally and used diplomatic immunity to avoid paying their tickets. While the problem has eased, New Yorkers still hold a special animosity for foreigners who park freely and illegally, and politicians continue to use that sentiment to their advantage.

Similarly, because alternate side parking rules have few fans among voters, City Council has added to the list of days when rules are suspended, aiming the dispensations at various religions and ethnic groups. In 2002, for example, the council voted unanimously to suspend rules on Asian Lunar New Year, Purim and Ash Wednesday, overriding the mayor's veto.

This year's political parking dispute concerns the use of meters on Sundays -- something the city has done in recognition, it says, of the fact that stores now stay open on Sunday. The move also brings in about $7 million a year.

But a Bay Ridge minister complained that parishioners were ducking out during services to feed the meters. In response, City Councilmembers Vincent Gentile and Hiram Monserrate introduced a bill that would ban metered parking on Sunday. (See related story)

Other Democrats picked up the cause. "There shouldn't be a tax on worshipping," mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer said. "People shouldn't have to pay to pray."

The city has done a done a few things on parking that have met with general approval, particularly the use of multiple space meters. Rather than feed coins into a metal meter on a post, motorists purchase a ticket from a machine and then leave it on their dashboard. Cars can then park more tightly. The system also enables the city to charge different prices at different times or discourage long stays.

Currently, Primeggia said, many of the meters charge $2 for one hour but $9 for three hours to spur turnover. "We're encouraging them to use it as long as they need it, but when they're done leave," he said.

The city also addresses parking in zoning decisions. Residents often cite increased parking difficulties as a hallmark of rapidly developing - or overdeveloped - neighborhoods. So, on Staten Island, for example, the city has increased requirements for parking to accompany new buildings. Of course, more space for parking can mean less land for other uses, including lawns and gardens.

PARKING AND NEW PROJECTS

Concerns about parking also enter into one of the year's hottest political controversies: the proposed Jets stadium on the Far West Side. The extension of the No. 7 subway line aims to make the proposed West Side football stadium friendly to transit users and discourage automobile use. The Jets anticipate 70 percent of people attending games will arrive by mass transit. This would require parking for 7,000 cars.

And an anti stadium group, the New York Association for Better Choices, sees that number as unrealistic. It predicts that each Jets game would attract 16,000 cars and 100 buses, requiring 70 acres of parking lots and garages.

For the short term, the city has said it plans to allow approximately 1,500 new spaces near the railyards. Eventually, it says, thousands of new parking spaces would be provided to accommodate the residential and commercial development of the surrounding area.

Parking is also a concern for the Nets arena in Brooklyn, which, like the Jets Stadium, aims to be accessible by mass transit. The arena plans call for 3,000 parking spaces but critics say this will not be enough. And, they charge, an already congested area will grow more crowded as thousands of Nets fans cruise the streets looking for parking.

Parking is such a problem for new projects that developers want even racecar fans to get out of their cars. The proposed NASCAR track on Staten Island would accommodate about 95,000 people, but the plan only calls for parking for 8,400 cars. International Speedway Corp. hopes fans will park at some 16 off-site lots and take shuttle buses to the track.

PAYING TO PARK

Even though parking is a cherished commodity in New York, the city gives it away. A 2002 survey found that only 24 percent of the almost 30,000 curbside parking spaces in Manhattan south of 59th Street had meters.

Donald Shoup, a professor at University of California Los Angeles, argues in his new book "The High Cost of Free Parking" that free parking creates many costs, helping to explain "extreme auto dependence, rapid urban sprawl and extravagant energy use." Just charging $1 an hour for those unmetered Manhattan spaces, he said, would generate $250 million a year.

"People are paying a very high cost for housing and people even go homeless and cars are parking for free," he said.

Shoup believes the city should set rates for on-street parking high enough so that about 15 percent of the spaces are usually unoccupied. In some areas of London, this is eight pounds -- about $15 -- an hour.

To make such a sharp increase in rates politically palatable, Shoup proposes the money go to local community agencies to fund neighborhood improvements. "Nobody ever wants to pay for parking, so you have to create someone on the other side of the meter who wants the money," he said.

Some critics say such policies are unfair to lower income people. And while this is less true in New York City than other places, businesses worry (.pdf format) that high priced parking will keep people from driving to their establishments and spending money.

Some cities, though, have taken more drastic measures to stop parking. Copenhagen for example has a policy to reduce parking by about two percent a year.

That would be fine with Kit Hodge, campaign director of Transportation Alternatives, as long as people take transit, bike or walk instead. "Our aim is to discourage parking," she said.

For More Information

Organizations

New York City Department of Transportation

Alternate side parking, other parking regulations and how to pay a ticket online.

Parking Pal

Information and tips designed to help drivers park in New York City

Transportation Alternatives

An advocacy groups that seeks to reduce automobile use. Its web site includes information on car and bicycle parking.

Resources

Colliers Parking Rate Survey (in pdf format)

A survey of how much it costs to park in 55 North American cities.

Gridlock Sam

Web site run by former New York City Traffic Commissioner Sam Schwartz with information on parking, driving and congestion in the city.

parkingticket.com

Company that will fight your parking ticket - for a fee.

2004 Urban Mobility Study

The Texas Transportation Institute's study of mobility and traffic congestion on freeways and major streets in 85 cities.

Articles

The Autonomist Manifesto (Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Road)

(New York Times Magazine)

A Brief History of Parking: The Life and After-life of Paving the Planet

(Architecture Magazine)

The Dynamics of On-Street Parking in Large Central Cities

(Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management, NYU)

Fewer Cars (Same Traffic)

(Gotham Gazette)

The High Cost of Free Parking

(Donald Shoup)

The site includes the book's first chapter, articles on the book and comments by the author.

High Costs Drive Car Owners Crazy

(Daily News)

NYC Parking Policy is Backwards and Dangerous

(Transporation Alternatives magazine)

No Parking. You're Welcome

(New York Times)

The Overdevelopment Debate

(Gotham Gazette)

Parking Space and Public Spaces: Why Parking Can Destroy Communities and How to Find a Place for It

(Project for Public Spaces)

The Savvy Parker

(New York Chapter, American Automobile Associatin)

Shakedown: Sometimes It's the Little Things that Drive Your Over the Edge

"Tepper Isn't Going Out" by Calvin Trillin

(Salon)

Discusses the novel about parking in New York

Ticketing Blitz?

(Gotham Gazette)

Fewer Cars (Same Traffic)

What’s going on with auto ownership and traffic in New York City?

News reports in February highlighted an 8.4 percent decline in the number of registered autos in the five boroughs between 2000 and 2003. Vehicle registration data posted on the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) website in late February show a further 1.6 percent decline from 2003 to 2004.

Ex-car owners and various experts offered a assortment of explanations for the decline in registrations. Rising costs of owning a car was one favorite. A research firm quoted in Crains New York estimated that car ownership costs rose 15 percent since 2001. The cost of parking in Manhattan garages is climbing, as are gas prices. Fines for parking violations increased 30 percent in 2004, spurred by a 20 percent increase in the number of tickets issued.

A Newsday article cited not only costs but also the scarcity of parking spaces and the soaring costs of housing, which consumes a larger share of the household budget.

Another possible explanation is that more people are registering their cars out of town. However, while the streets are sprinkled with parked cars sporting out of state license plates, it is not clear that the number is increasing.

A Department of Motor Vehicles spokesman suggested that maybe more people are ditching their cars and using mass transit. Indeed, in 2004 subway ridership hit its highest level since the mid-1950s, with 1.4 billion riders passing through the turnstiles.

Funny thing is that the decline in vehicle registrations has not made finding a parking space any easier. Nor has it reduced traffic congestion. Although auto traffic into Manhattan dropped after 9/11, the number of vehicles entering Manhattan showed renewed growth in 2004. According to the NYS Transportation Department, total vehicle miles of travel in the New York region increased in 2001 and 2002 despite the effects of 9/11. (Figures since 2002 are not available.)

So if traffic is up and auto registrations are down, what’s going on?

Part of the answer is undoubtedly that it’s not the high-mileage drivers who are selling their cars. An ex-car owner quoted by Newsday said that in order to avoid losing her curbside parking space, she hardly ever used her car. Drivers stuck on the Gowanus “Expressway” did not see her before and won’t be missing her now.

Most likely it is the occasional drivers who finally decided that they could simply do without their cars. These would seem to be the folks who bought an unlimited ride Metrocard and so “ride free” after hours and on weekends. They can use transit and the occasional taxi ride as their wheels to move around the city.

Another part of the answer is undoubtedly the economy. Car registrations dropped during the early-1990’s recession and then bounced back during the boom years of the late-1990s. While registrations continued to decline in 2004 even as the economy began to turn around, the rate of decline was less than in the prior two years.

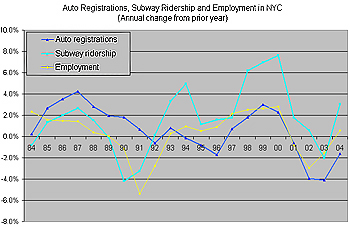

Whether the ranks of auto owners grow again remains to be seen. There has, however, been a fundamental shift from auto ownership to subway ridership. While auto registrations and subway ridership both rise and fall with the economy, as the chart below shows, prior to 1992 auto registrations grew more quickly than subway ridership (or declined by a lesser percentage). It was a consistent pattern evident year after year.

But since 1992, subway ridership has grown more quickly (or declined by a lesser amount) in every year – even years that there was a transit fare increase. On the margin, then, more people are plunking down money for their Metrocards than for their vehicle registrations.

This reversal of fortune does not mean that the city’s roads and highways are likely to be cleared of traffic congestion anytime soon, or that drivers will spend less time circling the block to find a parking space. But it does suggest that there is a viable choice, one chosen by more and more New Yorkers -- taking the subway.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Learning from the Subway Fire

Now that subway service has resumed to nearly normal -- several years ahead of schedule -- it is clear that last month’s fire in a subway signal room near the Chambers Street station created more than crowding and inconvenience for the public and higher expenses for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The fire also raised important questions. Why did the initial story need to be so heavily revised as the week wore on? Are there enduring lessons to be learned from this event?

First, why did the accounts of the cause and implications of the fire change so much from the initial news reports?

New York City Transit President Lawrence Reuter was initially reported as saying that the disabled lines would not return to service for three to five years. But two days later he revised his estimate to six to nine months. And on February 2-- about 10 days after the fire -- C train service resumed, and the A began running at almost normal frequency.

Officials initially attributed the fire to a homeless person setting fire to wood and refuse in a shopping cart 50 feet north of the Chambers Street station but now reportedly say they have found "no conclusive information to arrive at a definitive cause for this fire."

I think I can guess at the reasons behind these puzzling missteps. When Reuter predicted years of interrupted service, he was probably thinking how long it would take to rebuild completely the complex and antiquated signal room. But what most people wanted to know was when the trains would start running again. It appears that reporters took his response – about completely rebuilding the damaged equipment – to be the answer to their quite different question about the timeline for restoring service.

When officials attributed the fire to an unidentified homeless person rather than waiting for the investigation to be completed, they were probably thinking about the fire as just one more calamity beyond their control. Blaming the fire on the homeless matched their expectation that they could not have prevented it, and thus they looked no further for alternative causes.

Why did the press characterize the subway lines as “crippled or shut down” as though all the riders from the Rockaways to upper Manhattan would be left without any service? Part of the reason is that Reuter seemed to be saying just that. Another part of the reason is that reporters are not paid to plan subway re-routings. Any regular rider of the A and C lines knows that the trains are regularly switched to the F tracks in downtown Brooklyn during track work on the A and C lines in lower Manhattan – the exact tracks affected by the fire. Transit officials took advantage of this flexibility, and extended the V line from the Lower East Side into Brooklyn to serve C line stations in Brooklyn. They also added B service in Manhattan during rush hours to make up for the lack of C service.

What can be gained from this episode? No doubt, transit and fire department officials will be a little more focused on clear communications and not jumping to conclusions next time there is a fire or accident or other major disruption.

Another lesson is that the sprawling subway system can never be made completely secure. We do not know what started the fire, but no one is suggesting that terrorists are to blame. Whether it was, in fact, a homeless person, flammable material left by transit workers, or some kind of random electrical malfunction may never be known. It does seem obvious, however, that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s new ban on subway photography would not have prevented the problem.

Perhaps the most important lesson was learned by the public, or at least graphically illustrated for the public. For months, public officials, civic leaders, and transit advocates have been discussing the transit system’s capital program, which is up for refunding this year. Reporters have stepped up coverage of these issues but lacked a way to demonstrate what is at stake. The subway fire dramatized the city’s utter dependence on switches, control boxes, electrical cables and thousands of other highly technical and largely unseen equipment in the subway system. And thus, the subway fire served as an allegory for the repair and funding issues that most of the time seem only distantly related to the public’s daily experience of transit services.

The fire also helped to educate the public about how the system operates and how decisions about maintenance and upgrades can very tangibly affect the daily commute. It came to light, for example, that 158 of 200 signal relay rooms have been modernized and upgraded since 1982 with fire detectors, fire-retardant materials, and automatic fire extinguishers – just not the one north of Chambers Street.

Would more money have helped? More than any other MTA chairman appointed by Governor George Pataki, Peter Kalikow has been forthright about the need for increased funding for transit improvements. In this instance, however, Kalikow was quoted in the New York Times as saying, “If somebody gave us $50 billion tomorrow, we could not any faster upgrade these signals.” No doubt only so many subway repairs and maintenance activities can take place at any one time. But the MTA’s own budget recommendations include funding for far more projects, both repair and new construction, than anyone has found the money for. The value of those projects may be a little bit easier to explain this month than they were a month ago.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Pataki's Budget

“Pataki’s Budget Leaves Transit Projects In Doubt” read the headline in the New York Times online. (In the newspaper itself, the article, with a slightly different headline, was the lead story of the day).

Of course, many of these projects have long been in doubt, even as more and more people become convinced of their importance. A report released recently by the Rudin Center at NYU on commuter rail and subway expansion needs (in pdf format) concluded that, “Expanded transportation capacity is of vital importance to enable future economic and employment growth in the Manhattan central business district.”

It has been clear that one of the two major issues for transportation in 2005 will be financing the operation and expansion of the transit system. (The other is doing the same for the highway system.) The question has been: Where is the money going to come from?

As summarized here two months ago, the city’s Independent Budget Office and a respected civic group, the Regional Plan Association, discussed a range of ways to raise the money.

Last month, Peter Kalikow, the chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, called on Governor George Pataki to support increased taxes and fees on businesses, gas and mortgages that would keep the transit system in good working order and also fund such expansion projects as the Second Avenue Subway and the connection between the Long Island Rail Road and Grand Central Terminal. Stepping forth in more of a public leadership role than any MTA head during Pataki’s tenure in Albany, Kalikow warned that failure to fund at least the $17 billion core program would begin the transit system’s “descent” toward deterioration and financial crisis.

When the governor released his budget on January 18th, he proposed adopting two of Kalikow’s specific recommendations: an increase in the mortgage recording tax and increased motor vehicle fees. Pataki also asked for legislation to authorize innovative financing opportunities. He cited three examples from other states. Two involve the sale or construction of toll roads (in Chicago and Virginia), and thus are financed by motorist tolls. The third involves private investment in the Las Vegas monorail.

Overall, however, the governor’s budget came up well short of the MTA’s needs. The governor proposed to cover $15 billion of the $17 billion that transit officials consider essential.

Some transit advocates were cheered that Pataki proposed new fees to pay for transit improvements, while others criticized him for inadequate funding. The budget, which is subject to revision after a public hearing, is perhaps best viewed as the opening gambit in Albany’s long budget game, plagued for years by late budgets. Anyone keeping a scorecard on the progress of budget discussions might look for the following:

- When will the governor become more specific about additional revenue sources needed to plug the gap he left, and even to increase total spending from his proposed levels?

- Do revenue sources (fees, taxes or otherwise) provide new money and a long-term solution, unlike the crushing debt burdens that financed the transportation authority’s previous capital program?

- Do revenue sources require the governor and legislative leaders to gain broad political support, as a broad-based tax would, or is there continued effort to hide the pain through fees and taxes that most people do not pay (like the mortgage recording and business taxes)?

As New York struggles with how to pay for its transportation needs, a number of other cities around the country moved forward on major transportation expansion projects. In the November elections, voters approved new taxes to pay for system expansions, meaning that new, “real” money will be available for real projects. The Center for Transportation Excellence, a non-partisan policy research center in Washington DC, reports that:

- Phoenix area voters approved a 1/2 cent sales tax extension and a $16 billion regional transportation plan that will fund 30 additional miles for the region’s light rail system and expanded and improved bus services.

- Denver voters approved a 4/10 cent sales tax increase to construct 119 miles of new light rail and commuter rail lines; 18 miles of Bus Rapid Transit service, new parking at transit stations and expanded bus services.

- San Francisco East Bay area voters approved a “parcel tax” of $2 per parcel per month to underwrite continued bus services.

- San Diego voters adopted an extension to the 1/2 cent sales tax through 2028 to raise $14 billion for transportation improvements.

Each of these metro areas suffers from high levels of traffic congestion and are turning to transit expansions to help alleviate gridlock on their highways. Perhaps New York, blessed with the most extensive transit system in the country, can take inspiration from voter approval of higher taxes in other regions. New York can not only maintain the existing system but also fund forward-looking system expansions.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Should Public Funds Keep NY Waterway Alive?

Public funding for transportation goes back further than the eye can see, from building the Erie Canal to construction of the New York City subway and Interstate highways. In each case, the decision to expend public monies was based on pressing public needs for expansion of canal, transit and highway systems and the belief that public investment would pay dividends in economic growth.

New York and New Jersey officials are now faced with deciding whether privately operated ferries should be next in line for public funding. New York Waterway, which currently carries 32,000 passengers a day, primarily from New Jersey to Manhattan, is experiencing acute financial difficulties. The company’s president, Arthur Imperatore, announced this month at a City Council hearing that, “New York Waterway is dying.” The company has closed some routes and is planning to shut down additional routes later this month.

As with the region’s bus, subway, rail and highway systems, proponents of public subsidies argue that ferries provide a vital transportation service and spur economic development, in this case, along the New Jersey waterfront. Without the ferries, as many as 5,000 cars now parked near the New Jersey shore might travel into Manhattan each day, further burdening already congested tunnels and bridges into Manhattan. And ferries provide important redundancy in the transportation system, a fact graphically highlighted on September 11, 2001.

Ironically, NY Waterway, established in 1986, has long been hailed as a model of private entrepreneurship. Imperatore’s father set up the company to provide easy access to Manhattan for his New Jersey residential developments. The company offered not only ferry service but also bus service in Midtown to access West Side ferry terminals.

At first glance, ferry service might seem to be an ideal candidate for private operation. Ferries serve a niche market of customers who lack ready access to New Jersey’s bus and rail networks or who prefer the ambiance of waterborne transportation to the crush of PATH trains. Ferry riders are generally well-paid professionals. And by increasing access to Manhattan jobs, the ferries make private residential developments on the Jersey side of the Hudson River more attractive and valuable.

NY Waterway’s current troubles were spawned by decisions intended to build on its own success. Ferry ridership doubled after the 9/11 attacks, which closed the PATH system’s World Trade Center station. Both the company and public agencies leapt at opportunities to increase ferry services by adding routes and revamping ferry terminals. But after NY Waterway took on $33 million in debt to buy new boats, PATH reopened ahead of schedule, Manhattan job losses produced a drop in the number of commuters, ridership fell off after the Hudson River froze for two weeks last winter, fuel prices doubled and the company spent $4 million in legal fees over a dispute with the federal government over billing practices for post-9/11 service.

Some officials are now calling on government agencies to keep the service running. Hudson County (NJ) officials formulated a plan to buy the company and operate it in concert with Hoboken and Weehawken. But state officials last week nixed that plan.

Some Hudson County and New York City Council officials are calling on the City of New York and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to step in. New York City Councilmember David Yassky urged the city to waive docking fees that total $1.5 million a year. Council members also urged the Port Authority to authorize subsidies amounting to $16.6 million a year. Tom Fox of New York Water Taxi, a competitor to NY Waterway which is putting together a plan with three other ferry and sightseeing cruise companies to take over NY Waterway routes, said subsidies are needed to compete with the heavily subsidized PATH lines.

The City Transportation Department responded that the Council would need to offset the revenue loss if landing fees were waived. The Port Authority was noncommittal, calling for a “multiagency review of ferry service throughout the region.”

The Port Authority also pointed out that it has invested, or plans to invest, more than $100 million in ferry terminals, roadway upgrades and other infrastructure costs. Thus, the issue is not whether privately operated ferries should receive public subsidies, but what form of subsidies, and how much, and who will pay.

The most fundamental question is whether public agencies should subsidize specific ferry routes to keep them running. On the one hand, equitable treatment of commuters suggest that the public should subsidize ferry travelers. After all, the PATH system and NYC bus system only recover 41 percent of their operating expenses and even the NYC subway, which leads all transit systems in the U.S. in farebox cost recovery, only pays 67 percent of its expenses from fares, according to federal data (In PDF Format) summarized in a Brookings Institution study.

On the other hand, would political considerations overwhelm business decisions about which routes to keep, which to close and which to expand, leading to an inefficient and heavily subsidized ferry network that drains the public till?

The reticence of the Port Authority and NYC Transportation Department to agree to operating subsidies is well founded. The Port Authority has increased its funding for PATH while keeping PATH fares relatively low. Under pressure from Staten Island voters and elected officials, the Giuliani Administration abolished the Staten Island ferry fare. The average trip on the S.I. ferry costs $2.95, all of which is paid by the city, none by riders. The City Council recently adopted a bill to increase late night service and some rush hour service at an additional cost of $5 million a year.

The test for public officials is now to find a way to support continued ferry service where it provides substantial public benefits while maintaining the market-driven sensitivities to both changing demand and opportunities for service that are the hallmark of private companies. This is a difficult task, made more so in the current crisis-driven environment, as NY Waterway totters on the brink of closure.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Put Internet Access On The Trains

As the Metropolitan Tranportation Authority struggles with its newest round of financial and political woes, the agency is failing to consider a ripe opportunity for peripheral economic development: providing wireless Internet access, commonly called Wi-Fi (for wireless fidelity) on its commuter trains, the Metro-North and Long Island Railroads.

Wireless Internet access is proliferating worldwide, increasing by 145 percent (80 million users!) in 2003, helped along by a propagation of new digital technologies -- WiFi is now available on laptop computers, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and mobile phones.

While users grow accustomed to having Internet access, they demand more connections, including on their commutes. Market studies repeatedly indicate that ridership would increase tremendously if Wi-Fi were provided. The resource is already being provided for public transportation and commuter rail users in such major cities as London, Paris, Seattle, the Bay Area, Tokyo, and Chennai, India. Lufthansa and other airlines are also already offering Wi-Fi upwards of six miles in the air.

New York City, in comparison, provides Wi-Fi on no transportation mode other than the Hampton Jitney and the LimoLiner luxury bus to Boston. The MTA has responded to queries that it has no intention of providing wireless Internet resources.

But the benefits to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s roughly 12 million monthly train riders would be plentiful. Businesspeople could increase their individual productivity during the ride, which may be up to two hours long from some locales. Sorting through a plethora of new emails on the way to work, accessing the company intranet, or using new Internet-based technologies to make discounted international phone calls, all heighten productivity - so much so that in Sweden, a group has begun advocating for employers to consider commuter rail time as work hours, since employees conduct such a large amount of work during their ride.

The MTA’s trains stop at 28 higher education campuses outside New York City proper. Because it is expected at most institutions that students receive information via email and/or course Web sites, these students surely would appreciate extra time for access. And the trains could also offer entertainment ranging from films, as provided for example by AtomFilms.com (headphones required, of course), to virtual visits to the art scene such as available at Swissart.net.

Expanding work or academic hours and providing such entertainment in this way could prove such a lure as to decrease automobile traffic into the city

Far from further isolating passengers from one another, it might actually have the absolute effect – creating a kind of on-board online community. Hooked-in passengers could participate in networked activities by sharing music (legally) using radio station-like playlist broadcast technologies, play trivia and video games against one another, or use a localized Web-based job-hunting/dating/classifieds service, in which the network matches up potential employees/singles/apartment hunters through pre-completed surveys. (With matches nearby and in-person, convergences would play out faster and more faithfully).

But What Would It Cost?

Expenses are difficult to quantify, but studies of other deployments show an investment by the MTA would hardly dent its new $200 million rainy day fund. If the project still seems too expensive, consider air conditioning, which was seen as an unnecessary investment by train operators in the 1930s and 1940s. No one now questions the necessity of having invested in air-conditioning, and the same will surely be true eventually of Wi-Fi as well.

What’s more, the MTA would quickly see a return on investments through new abilities to streamline its own processes, including enhanced train tracking, improved communications to headquarters and customers, heightened emergency communications resources (redundancy of communication modes is a key). Plus, the potential for mobile ticket collection (think a human EZ-Pass) would lessen paperwork and improve efficiency.

Revenue generation from Wi-Fi use would come in several forms. If the agency partners with one of the multiple wireless access providers, such as PointShot or Boingo, which require users to pay a relatively modest daily or monthly fee for unlimited Wi-Fi use, the agency could surely work out a financial gain. These returns are not minimal: Revenue generation from wireless hotspots is expected to reach $9 billion by 2010 according to industry research. Further income would be derived from direct online advertising, partnerships with music and movie downloading services, and subsidized Web-only discounts at locations serviced by the train line.

An investment in Wi-Fi then – both on the train and, ideally, at the stations as well – would generate revenue, increase customer satisfaction, and improve internal efficiencies. It would also help New York catch up to the other world-class cities that do this already. Is this likely to happen during its current period of fiscal chaos? No. But it would make sense to do so – for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to show its customers it is thinking about their needs.

Sarah Kaufman is a graduate student in urban planning (specializing in infrastructure) at New York University's Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service Â

Cycling In the City

Cyclists riding across the Brooklyn Bridge. New York City has 480 miles of bike lanes and paths, including one over each East River bridge. |

Stu Cohen has not been involved in any of the police clashes or court cases or competing City Hall bills of the past few months. He does not see himself as a bike warrior. He simply wants to do what the majority of residents of Amsterdam, eight million Chinese in Beijing, and a half million or so other Americans (according to an estimate by the U.S. Census) do every weekday. He wants to use his bicycle as his principal means of transportation.

So, how did he get into that argument over his bike last week in the middle of Tiffany's?

"I always take my bike in with me," Cohen told the employee at the Fifth Avenue jewelry store who stopped him. "It's a folding bike; it's the same size as a stroller." It made no difference; he would still have to leave.

It isn't easy being one of some 100,000 daily bicycle riders in New York City.

Yes, cycling is fast, cheap, and pollution free. Yes, as any of those bicyclists will tell you, it offers good exercise and provides a great sense of freedom.

But Cohen, who commutes via a Dahon-brand folding commuter bike from his home in Stuyvesant Town to his job in a non-profit agency in Tribeca, also has the typical catalogue of bicyclist's woes -- he sometimes gets bike grease on his pant leg (he wears a dress shirt and khakis, rather than spandex); he has been "doored," the term cyclists use when a car door unexpectedly opens in front of them; he was recently cut off by a car with a "W" sticker.

And if New York has become a better place to bike in recent years, bicycling in the city has somehow, in recent months, become a political act -- even a criminal act.

Arrests at a Critical Mass event |

More than 250 cyclists were arrested and had their bikes confiscated in protests of the Republican National Convention this summer. Since then, bike advocates, the city, and the New York Police Department have been battling in a series of lawsuits that will decide how, when, and where groups of cyclists can ride. (See related article Can Critical Mass Negotiate a Truce?)

Recently, Bronx City Councilmember Madeline Provenzano introduced a bill that would require licenses on every bike in the city - and threatens jail time for those who do not comply. Cycling groups say Provenzano has a history of being anti-bike: she has stalled another bill that would allow bikes inside public buildings and even tried to remove bike lanes from her neighborhood.

"I have personally had a lot of trouble with bikes," Provenzano said.

THE STATE OF CYCLING IN THE CITY

The city's first urban bike path opened in 1895 along Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. On the first day, 10,000 riders showed up to ride, and it continued to be so popular that the city widened it.

A century later, that bikeway was still heavily used, but there were few others. In 1994, the city with some 5,700 miles of streets had only 56 miles of bike paths. An invention called the automobile had pushed the bike aside.

Over the last decade, however, things have changed considerably.

After years of work by cycling advocates and with millions of dollars in federal transportation funding aimed at reducing traffic and pollution, the city has begun to build more bike lanes, install bike racks, and outline a plan for car-free greenways, including a 32-mile loop around Manhattan.

Today, there are 408 miles of bike lanes and paths in the city, and pedestrian and bike pathways over each of the East River bridges.

"We hope that one day New York will be one of the world's great bicycling cities." Transportation Commissioner Iris Weinshall recently told the New York Times.

Still with all of these measures, New York can't exactly be called bike friendly.

An average of 20 cyclists are killed each year by motor vehicles. A reminder of the danger of riding on the city streets came last Thursday when a bike messenger was killed in midtown after he tried to swerve around a double-parked truck.

New York City is also often referred to as "the bike theft capital of the world." Between 60,000 and 80,000 bikes are reported stolen each year (many more go unreported), and only two percent are ever recovered, according to the New York Police Department.

Some of the heaviest and most expensive bike locks on the market are named after the city: an eight pound, steel chain that sells for $129.99 is called the "New York Fahgettaboudit" lock.

When it comes to policies that encourage cycling, New York surely lags behind European cities, but it is a poor second to other U.S. cities as well. Chicago is planning a downtown "bike station," where cyclists can safely lock their bikes, take a shower, and even grab a cup of coffee on the way to work.

"We're doing little better than running in place," said Charles Komanoff, a long-time cycling activist who has been riding in New York for 30 years.

ROAD RAGE

The city's streets can be hostile and dangerous places.

Many motorists - who already spend hours stuck in traffic - do not welcome cyclists or bike lanes and complain that cyclists don't follow traffic laws.

"The bike lane on 62nd Street between 5th and 6th Avenues is a nightmare for us residents," Sunset Park resident Noel Waters wrote on the Community Gazette's message board. "The lane has no connecting points. Nobody asked for it and nobody uses it. The Department of Transportation has allowed double parking outside the lane on alternate parking days in order to keep the bike lane open, which I've never seen a cyclist on."

Cyclists, in turn, often feel threatened by cars that cut them off, park in bike lanes, or honk their horns. And some cyclists lash out.

"I scream, bang on hoods, and I've taken off side mirrors," said Mike Kowalski, who manages a bike store in Tribeca. "If a car gets into my lane, I see it as a violation."

While cars, bikes, and pedestrians all have rights to the city streets and are required to abide by traffic regulations, the real issue, advocates argue, is which party can do the most harm. Roughly 200 pedestrians are killed each year by cars, compared to about one pedestrian every couple of years who is killed by a bike.

CRITICAL MASS

Critical Mass riders state their views |

On the last Friday of every month, the battle between bikes and cars plays out in a dramatic event, called Critical Mass.

Hundreds of cyclists ride together in a large group, taking over street lanes, riding over bridges usually open only to cars, and occasionally stopping in the middle of a busy intersection, raising their bikes in the air, and shouting slogans like "One Less Car."

The goal is to raise awareness of bicyclist and pedestrian rights and promote alternative forms of transportation, but it also offers cyclists the rush of speeding through the city's streets in the safety of a large crowd of other bicyclists.

For years, a few hundred participants have attended the New York City event, often with police escorts and little objection from city officials.

In August, a few days before the start of the Republican National Convention, 5,000 cyclists joined in the ride. The police, already prepared for the dozens of anti-Bush protests that would occur over the next few days, wrapped giant nets around part of the group, arresting more than 250 for traffic violations and disorderly conduct and seizing many bikes.

Since then, city officials and city cyclists have been locked in a legal battle.

In September, five cyclists, who had their bikes confiscated, went to court to block the city from seizing more bikes. A federal judge ruled in their favor, saying that the city could not take bikes of people who were not charged with breaking the law.

The city, arguing that the ride is a safety hazard and violates traffic rules, asked the court to ban the cyclists from riding without a proper parade permit or even to congregate at the usual meeting place at Union Square without permission from the parks department.

Lawyers for the cyclists say they do not need a permit. Bicycles, they say, have as much legal right to the road as automobiles, and the millions of cars that clog the city streets every day do not need a permit.

The battle between Critical Mass and the city has divided cyclists. Some say a group of reckless bikers are hurting the cause. But others argue that the case is helping build new grassroots support for cycling.

"The more people who bike the better," said Noah Budnick of Transportation Alternatives.

A BIKING BACKLASH?

Citing the issues with Critical Mass and her own negative encounters with reckless cyclists, Bronx City Councilmember Madeline Provenzano recently proposed a bill (Intro 497) that would require bike riders over the age of 16 to register their bike with the Department of Transportation and pay a fee of no more than $25.

Those who fail to do so would be subject to a fine of up to $300 and up to 15 days in jail.

"I have personally had folks ride their bikes into my car, and there is nothing you can do legally." said Provenzano. "Bikes should be subject to all of the same laws as automobiles."

Last year, Provenzano tried to get bike lanes removed from her Bronx neighborhood after 19 residents of Morris Park received tickets for parking in the lane. She said the lanes were painted incorrectly, are barely used, and the local community board did not want any bike lanes in the area.

The group Transportation Alternatives called the council member's bill "a malicious attack against people who ride bikes in New York City."

The Department of Transportation did not return calls seeking comment on the bill, but few other council members have voiced strong support for it.

When City Councilmember John Liu, who chairs the transportation committee, was asked about the bill, he told Newsday; "When I was a kid, I had a license plate on my bike. I'm trying to remember which cereal box I got it from."

WHAT CYCLISTS WANT - AND THE ROADBLOCKS THEY FACE

Cycling advocates argue that bold new policies are needed in order to convert an average New Yorker who may ride along the bike path a few times a year into someone who considers a bike as a mode of transportation on par with the subway, a bus, or taxi-cab.

1. Bikes in Buildings

The first hurdle, advocates say, is for the city to allow bikes inside buildings. There is a shortage of bike racks in the city, just 1 for every 33 riders. In surveys, New Yorkers have cited concerns over theft as the biggest deterrent to cycling in the city.

In 1999, a bill (Intro 155) was introduced to the City Council that would that would require all buildings to make reasonable provisions for those who wish to bring bicycles into their workplace.

But in the five years since the bill was introduced, it has gone nowhere. For the last two years, Councilmember Madeline Provenzano, who chairs the Housing and Buildings committee, has refused to hold a hearing on it.

When asked about the measure, Provenzano said she thought it was a "good bill," but that the commitee's schedule is full until the end of the year. But she said she may consider it next year.

"And of course, I'd like to consider my [bike license] bill at the same time," she said.

2. Car-Free Areas

Another issue is creating more car-free areas in the city. Those that do exist are often crowded. The Hudson River is frequently filled with cyclists, rollerbladers, joggers, and walkers.

For years, pedestrians and cyclists have been trying to ban automobiles from Central Park and Prospect Park in Brooklyn. Both parks already have some car-free hours. Automobiles use the drives during morning and evening rush hours during the summer, but pedestrians and cyclists want cars banned 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Transportation officials argue that banning cars from the parks would force automobiles onto side streets, particularly during rush hour, creating havoc for drivers and the surrounding neighborhoods. Despite support from environmental groups and the majority of the City Council members that represent the neighborhoods adjacent to both Central Park and Prospect Park, the effort to make parks car free has not been successful.

3. Traffic Enforcement

New York City automobile drivers run 1.2 million red lights a day, according to a 2000 report by the city comptroller. Advocates also say the police must do a better job of enforcing traffic laws and politicians must create stiffer penalties for drivers who hit pedestrians and cyclists.

Red light cameras, which can spot someone running a light and issue a summons through the mail, can help law enforcement cover more of the city. However, legislation that would pay for more red light cameras is currently stalled in Albany.

4. Reduce Number of Cars

Some advocate more stringent methods. The only way to really make streets safer, they say, is to reduce the number of cars on the road. And one way to do that is to add tolls to the East River Bridges or fees to use certain streets in the city.

London began issuing a "congestion charge" for motorists who drive through the central part of the city. The number of cars decreased, and the number of bicyclists increased. The money raised from the charge goes back into improving the city's transportation system.

The idea of putting tolls on East River bridges comes up periodically, most recently from Mayor Michael Bloomberg who proposed a toll in order to help balance the budget. The plan never materialized and recently Bloomberg called the idea "impossible to enact."

IS CYCLING A CULTURAL THING?

Even if all of these suggestions were implemented it is unlikely that New Yorkers would rely on bikes in the same way the Chinese or Europeans do. Car culture pervades America, and to a certain extent New York.

Charles Komanoff believes that this can change over time. The more people bike, the less abnormal it will seem; the less abnormal it seems, the more people will bike. He adds that New York City is already on its way to being separate from the rest of the country, both culturally and politically.

New York City is already the only city in the country where most residents don't own a car. Komanoff dreams of a New York City "where you don't have to be an athletic, young, risk-taking eco-freak to be a cyclist."

Related Links:

Bicycle Advocates and Clubs

Transportation Alternatives

New York Bicycling Coalition

New York Cycling Club

Five Borough Bicycle Club

New York Bike Messenger Association

Times Up

Right of Way

Bike the Big Apple Tours

League of American Bicyclists

Maps, Plans, and Rules

Department of Transportation Bicycling Maps

NYC Bicycle Network Development Plan (1997 city plan to encourage cycling)

NYC Greenway Plan (1993 city plan to build 350 miles of greenways)

Bicycle Traffic Rules and Regulations

Gotham Gazette's Related Articles

Can Critical Mass Negotiate a Truce?

Car Free Parks

Yield to Bicycles

Pedestrian Safety

Lessons Learned in Creating the Hudson River Parkway

Manhattan Waterfront Greenway