Building Transportation for the Next Century: We Can Do it All

U.S. Senator Charles Schumer argues that a downtown train to the airport and the extension of the number 7 train on the west side must not get lost amid all of the debate over memorials and stadiums.

MetroCard Discounts

The transit system’s fare discounts helped produce rapid increases in subway and bus ridership in the late 1990s. But has the success of the fare incentives, which include 30-day and 7-day passes and discounts on bulk purchases, become too much of a good thing

That was the implication last month as Metropolitan Transportation Authority board members discussed a projected $500 million-plus deficit next year. Channel 2 reported that “transit sources” say the MTA is considering another fare hike, which would take effect in January 2005, less than two years after fares rose last May. Channel 2 reported that 30-day unlimited MetroCards could be going up $3 to $73 per card, and weekly passes by $3 to $24.

The MTA has promised not to touch the $2 base fare until 2007 at the earliest. But the promise of a stable $2 base fare leaves room to increase the cost of discounted fare cards.

The news reports last month may have been a trial balloon to test public reaction to an increase in the price of unlimited ride passes. If the base fare stays the same, how do riders and the press react to an increase in just pass prices?

Press reports on this development focused on the average cost per ride. The MTA expected the average cost per ride to increase from just over $1.00 before the fare increase to $1.30 after the fare hike. Because more riders moved to discounted fare cards than the MTA expected, the average cost per ride increased to only $1.25 instead of $1.30. The MTA had to adjust downward its projection of fare revenue for 2004 and subsequent years as a result.

But the terms of this discussion about the fare are as antiquated as the token since riders no longer pay by the ride. The “per ride” in these costs include every time riders board a bus or swipe through a turnstile. Counted this way, “free transfers” are not free at all but are “costing” $1.25 each. And anyone who borrows a family member’s unlimited ride card for a weekend trip is not getting a “free ride” at all but is “paying” $1.25 per swipe.

An example illustrates how the per ride figure can be distorted by the way people take advantage of the fare incentives. Take a rider who normally makes 21 round trips a month using a bonus per-ride card and then switches to the 30-day card and makes 25 round trips a month. The cost per ride drops from $1.67 to $1.40. But MTA revenues? No change.

In the big picture, the MTA may be better off signing up as many 30-day card users as it can. Many New Yorkers are more and more orienting their life to use the subway and bus, not only to work but also for shopping and leisure trips. Most of the gains in ridership in the 1990s came on the weekend, not weekdays. Those folks are seen walking the streets in SoHo and shopping at the new big box retailers on Sixth Avenue instead of hopping in the car and going to New Jersey. This has all the look and feel of building a loyal customer base.

These loyal customers may produce benefits for the city as a whole in other ways as well. In 2002, the number of cars registered in the city experienced its largest decline in a decade. Isn’t that a good thing?

The new fare policy question, then, is what someone who has unlimited use of the transit system should pay in fares, as compared with those who buy a la carte. There are issues of equity and fairness here, as the frequent-users include some of the more affluent people in the city and the per-ride folks include students and part-time low-income workers.

There are also issues of cost. It matters when the new trips are taken. If you ride in the off-off-peak when the trains are relatively empty, the additional cost imposed on the transit system of that trip (the “marginal cost”) is nearly zero. If you ride at the peak when the MTA runs as many trains as it can, the marginal operating cost is about zero to the MTA, although there is a pretty fair price in crowding to others on the train or bus. If you ride in the “shoulders” when the MTA adds service as ridership expands, then the marginal cost of riding is well above zero.

Finally, there is the issue of to what extent riders should pay versus the general taxpayer. The MTA has loaded up on debt to finance rebuilding the transit system, buying new trains and buses, etc. That is forcing upward pressure on fares. Should riders pay, or should the city government, Albany or the feds be more forthcoming with dollars.

Results of the Fare Increase:

The MTA set the relative prices of passes and other parts of the new fare last May to encourage riders to “buy up” to 7-day and 30-day passes, and to move away from small-value MetroCard purchases. The proportion of fare revenue from 30-day passes increased to 22.5 percent of fares paid in January 2004 compared with 12.0 percentearlier. That is a big change, and more than the MTA expected.

The fare increase not only made the 30-day pass more attractive, it also made boosted use of the pay-per-ride bonus by increasing the size of the discount from 10 percent to 20 percent, reducing the threshold purchase amount from $15 to $10. As the graph below shows, the 30-day pass and bonus card increased market share, while the 1-day pass (which increased greatly in price) lost share and the token was eliminated.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Long Commutes and Lost Opportunities for Planning

Why does the city with the largest mass transit system in the country have the longest commutes? Tom Angotti offers a few answers – and lost opportunities for planning.

Awaiting The Fate Of City-Subsidized Private Bus Lines

The long-simmering controversy over the fate of New York City-subsidized bus lines was brought to a boil early this month when news reports revealed that the Bloomberg administration has $150 million in unspent funds to replace aging buses and improve bus facilities of the seven private bus companies. This pot of money has accumulated over more than two years as Bloomberg and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority have been negotiating the authority’s takeover of the bus routes, which primarily serve local bus riders in Queens and the Bronx and express riders coming into Manhattan.

Bloomberg wants to turn the bus routes over to the MTA and eliminate the city’s $100 million annual subsidy of the bus companies. Shedding the subsidies for the private bus companies would help close city budget deficits. It would also further reduce the city’s contribution to mass transit. City contributions to the authority’s capital budget fell from $205 million in the early 1990s to only $75 million last year.

Critics believe that the city has refused to purchase new buses as a way to intensify political pressure for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to take over the bus routes. Using the existing old buses leads to more breakdowns and poorer service for riders. The private bus companies charged in a lawsuit last year that the city had decided “to starve the companies of new buses as part of its plan to create intolerable operating and financial pressures.”

The Bloomberg administration responded that the authority and private bus lines use different types of buses. “If we purchase the buses before the negotiations are complete,” a Bloomberg spokesman reportedly said, “we run the risk of buying obsolete buses that the MTA does not use and cannot service.”

This argument has not passed muster with critics. Unless the city insisted on purchasing more buses fueled with compressed natural gas (CNG), there are no fundamental differences between MTA and city-purchased buses. If the city wished to do so, it could order buses that meet the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s bus specifications and could be used by the MTA once the agency takes over the routes.

The authority would gladly take over the bus routes under the right fiscal arrangements. It believes that it can provide better service by applying its expertise in bus operations and through economies of scale. But the authority has rejected Bloomberg’s proffered deal unless it is “made whole” financially. If it takes over the bus routes without receiving additional funding, it would have to find scarce dollars either through increased state or federal subsidies – an unlikely possibility – or through higher fares.

Already, the city and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority have missed self-imposed deadlines of last June 30 and of January 1 to complete a deal. The city has extended the current franchises with the seven bus companies until June 30, 2004 and hopes to agree to a transfer by that date.

Meanwhile, service on the lines deteriorates. According to the city’s latest Mayor’s Management Report, the cleanliness rating on the city-subsidized buses declined from 85 percent in July-October 2002 to 68 percent a year later. In interviews with the New York Times, riders complained of buses taking 30 minutes or longer to show up.

(Large) Relic Of A Bygone Era

In the context of public transportation in the New York region, the privately operated bus lines seem like small potatoes and generally receive scant attention. But compared to any other city, the service is substantial – 82 routes, 1,250 buses and 400,000 riders a day make the private operators as a group the twelfth largest transit bus fleet in the U.S. and Canada.

Current franchise arrangements are a relic of a bygone age when private bus operators could make a profit providing service. The city once franchised or contracted with a variety of transportation providers including bus companies, trolley operators and even the companies that operated the first subways. When bus companies were profitable, franchises made sense as a way to select which operators would have the right to use the city streets. But the city has provided capital subsidizes to the bus companies since 1974, thus making for an odd arrangement of public subsidies for franchise operators.

The city owns the buses and some of the bus depots while the bus companies own most of the depots and provide the service. Drivers, mechanics and other workers are bus company employees. Most employees are unionized and have the right to strike – a right exercised several times in recent years, cutting off vital service to riders.

This system has survived previous attempts at change. Revisions to the City Charter in 1989 mandated that the bus franchises be rebid periodically to create competition among companies and thus, it was hoped, cut costs and improve service. None of this happened, however. A combination of political influence, bureaucratic inaction and the likelihood that any rebidding would be unfair led to periodic extensions of the long-running franchises. Although some conservative writers have continued to advocate for competitive bidding for the franchises, it is difficult to imagine how new companies, lacking bus depots, could compete effectively against the incumbents.

Thus, the city has turned from the idea of franchising to the hope of transferring the routes to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Aside from the budget and subsidy issues that have played prominently in the press, the transfer raises enormously complex issues. Presumably, unionized employees would be transferred to the MTA, as would facilities owned by the city and the companies. Under law, employees would have their jobs protected. But the private bus companies and the MTA have different unions, creating hurdles for the authority to switch bus routes between garages and rationalize operations to save costs. The different pension plans of the authority and private companies will also need to be resolved. While these issues are ultimately solvable, there may well be more bumps in the road for riders, even once the city and MTA resolve the subsidy issue.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

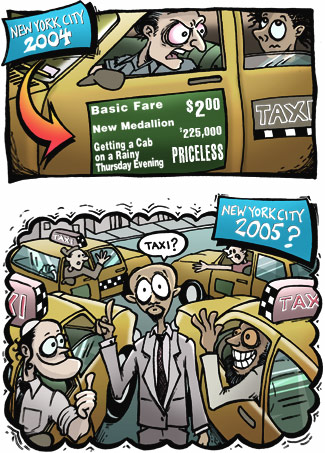

Taxi Fare Hike

After more than two years of start-and-stop debate on the issue of a taxi fare increase, the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) proposal for a 26 percent hike, which would increase the average fare from $6.85 to $8.65, was no surprise. It has been eight years since the last fare increase and news reports indicated that many of the nine taxi commissioners favor a fare increase. Moreover, a fare hike, broadly supported by taxi owners and drivers, has won editorial endorsement in the city’s papers and apparently some combination of acceptance and support from taxi riders.

What is remarkable is the commission’s plan to allocate three-quarters of the fare increase to driver incomes, with the remaining one-quarter allocated to cover increases in taxi owners’ expenses. This 75/25 driver/owner split of the fare increase is an historic change from past practice. Traditionally, taxi fleet owners and the now-defunct Taxi Drivers Union negotiated a 50/50 split of fare increases. Ironically, if the plan is adopted, drivers will have gained a larger portion of this fare increase now, when they have no union to represent them and a Republican mayor is in office, than when the drivers were unionized and Democrats occupied City Hall.

Why The Shift Towards Drivers

The Taxi and Limousine Commission’s proposal partly reflects the emergence of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance as a vocal and effective driver advocacy group. Drivers have not had a strong voice in the industry since the late 1960s, when the dissolution of large fleets weakened the influence of the Taxi Drivers Union.

A second factor in the new 75/25 split is the recognition that both taxi owners and drivers and the public benefits when driver incomes increase. Drivers obviously benefit from higher incomes. To the extent that higher incomes attract a stable and committed driver workforce, the quality of cab service is also likely to improve. My recent report also concluded that higher driver incomes are associated with lower accident rates for taxicabs. And to the extent that higher driver incomes attract more drivers to the industry, taxi owners benefit by getting their cabs leased for more shifts a week and generating greater income from lease fees.

A third factor is simply that government officials and the public sympathize with the needs of hard-working, largely immigrant cab drivers. Although estimates of driver incomes vary from the $22 per shift sometimes claimed by the Taxi Workers Alliance to my estimate of up to $120 a shift on average (with a wide variation from one driver to the next), even $120 for a 10 to 12 hour shift is clearly too low, particularly considering that as independent contractors, drivers do not have an employer paying Social Security, health insurance or pension benefits.

While there is broad public and industry agreement that drivers should receive most of the fare increase, there is sharp disagreement on whether the city’s proposal has struck the right balance. Bhairavi Desai, co-founder and organizer of the Taxi Workers Alliance, says that the city’s proposal is a “good start.” But she believes that the city should give drivers a better deal, ensuring that they can earn a “livable wage” of $14 per hour for 12-hour shifts. After the proposed fare increase, drivers will still make less than $10.10 an hour.

The Metropolitan Taxicab Board of Trade, which represents taxicab fleet owners, believes that the owners' predicament should be taken into account, citing 37 percent increases in operating costs since the 1996 fare increase, and additional costs from the Taxi and Limousine Commission’s proposed service improvements.

Will Cabs Operate Differently?

The debate between drivers and fleet owners is complicated by uncertainty about how the fare increase may lead to changes in the way that cabs are operated. In a traditional fleet operation, fleets pay all the costs of operation except for gasoline, which drivers pay. However, most of the industry (aside from the one-third or so of cabs that are owner-driven) lease by the week rather than by the shift. Weekly leasing reduces owner expenses for operating a garage, checking cabs between shifts and, in some cases, maintaining and repairing the cars. Furthermore, some weekly leases involve the lease of just the medallion license. In these “driver owned vehicle” leases, drivers pay for both the purchase and maintenance of the car. As I discussed in another recent report, some proposed changes by the Taxi and Limousine Commission may prompt some owners to move further in the direction of weekly leasing, thus shifting some operating costs to drivers, and might reduce the availability of cabs.

900 Additional Medallions

Beyond the driver/owner income split, the city’s taxi fare proposal is notable for its timing. The proposal comes in the midst of environmental reviews for issuance of 900 additional taxicab licenses over three years, with the first batch of 300 planned for issuance by the end of the current fiscal year on June 30. Although the fare and new medallions are officially considered in two separate processes, it was widely expected that the city would increase the fare prior to the first medallion auction. One reason for the timing is to ensure that any boost to medallion prices from the fare increase would be captured in auction prices. In addition, unofficially linking the fare to the medallion sale discourages any taxi owners that are inclined to oppose the medallion sale from actively working to stop it.

No Increase In Wait-Time Charges

While the overall size of the proposed fare increase, 26 percent, is widely accepted, some have questioned the structure of the proposed new fare. The proposed fare increases the mileage charge from $1.50 per mile to $2.00 a mile, a 33 percent increase, but leaves the wait time charge of $12 an hour unchanged, just as it was not changed in the 1996 fare increase. This means that drivers will make the same money waiting in traffic in 2004 and beyond as they did in 1990, while they will make 60 percent more when moving at any reasonable speed. Drivers will thus be encouraged to avoid congested Midtown traffic if they can find passengers elsewhere in Manhattan. This may be good from a traffic standpoint (potentially fewer cabs in Midtown) but would not help increase taxi availability for passengers.

Taxi and Limousine Commission Chairman Matthew Daus said that the wait time issue is likely to draw comment at the commission's March public hearing on the fare proposal and that the commission will “deal with drivers’ concerns” after the hearing.

Drivers will also be encouraged to serve Kennedy Airport since the flat rate from JFK to Manhattan is proposed to increase from $35 to $45, a 29 percent increase. Press complaints of a lack of cabs at JFK may thus be alleviated.

Rush Hour Surcharge

The city’s proposal abolishes the 50 cent night surcharge, instituted in the early 1980s when it was difficult to attract drivers to work at night. The night surcharge would be replaced with a $1 rush hour surcharge in effect between 4 p.m. and 8 p.m. The rush hour surcharge is intended to increase cab availability during this peak-demand period by encouraging drivers and owners to move shift change times out of the traditional 4-5 p.m. period. Whether this will happen remains to be seen. The surcharge may also increase cab availability because the higher fare will somewhat depress demand, thus following the tenets of “congestion pricing.” In this respect the $1 surcharge makes sense and might also be applied to the morning rush hour.

Paying By Credit Card And Other Improvements

The city also announced four other service improvement proposals along with the fare increase. Two of the proposals are much-needed improvements: mandating acceptance of credit and debit cards for payment of the fare, and mandating scratch-free partitions so that passengers can see out the front window and can see the driver and cab licenses, which are mounted on the driver’s side of the partition.

The city also proposes to establish a group ride program at various as-yet unannounced locations. Group riding promises to give passengers a break on the fares they pay. Unfortunately, most group ride experiments have failed due to the difficulty of matching up passengers with similar destinations and because the process of grouping passengers compromises a main benefit of taking a cab, which is speedily getting to one’s destination.

Mapping Technology

The city proposes to mandate GPS (global positioning system) technology in each cab. The idea is to bring cabs up to speed with current technology, a sensible idea that fits nicely with the mayor’s background and goals. The announced specifics of the program, however, are weak – in-car mapping capabilities and automated data collection. A much better idea would be to use GPS to track the location of occupied and unoccupied cabs in real time and immediately feed this information back to drivers on a map that shows their immediate geographic area. Drivers could use the map to drive toward areas of high demand for cabs, benefiting both themselves by getting more fares, and benefiting customers by getting cabs to the areas they are most needed.

More Income For Drivers; More Availability For Riders

Overall, the implications of the fare increase, which is likely to take effect in the late spring, are most significant for driver incomes and taxi availability. Driver incomes would increase by as much as 40 percent. Their cash take-home incomes would reach record levels in inflation-adjusted dollars.

For taxi users, the fare in inflation-adjusted dollars will be in the upper end of the range that the fare has occupied over the past two decades, and significantly below the fare in the 1970s.

More significantly for taxi riders, the fare increase combined with the proposed sale of 900 new medallion licenses will increase cab availability as the number of cabs expands and the higher fare somewhat reduces demand. Using economic growth and inflation estimates in the city’s January budget plans, I estimate that cab availability will increase by six percent from 2003 to 2007. This is a significant increase, particularly in the face of a growing economy, and will bring availability back to the relatively healthy level experienced in 1992.

Once the fare increase and medallion issuance are completed, the Taxi and Limousine Commission will need to decide whether it wants to continue treating these essential policy issues like the flu -- once it's over, it simply goes away. A better course of action, once current controversies are resolved, would be to evaluate industry finances and taxi service availability on a regular basis and place decisions on fares and new medallions in the context of providing the city with good quality, readily available cab service.

Bruce Schaller is principal of Schaller Consulting, providing research into transportation. He is also a visiting scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Urban Issues: Mass Transit

URBAN ISSUES - MASS TRANSIT

• • • • • • •

• • • • • • •

John Edwards

Edwards supports federal mass transit initiatives like the Federal Transit Administration's Job Access and Reverse Commute program, that helps low income people who do not have cars get to jobs in the suburbs.

John Kerry

Kerry supports giving cities options on how they spend federal transportation money, including projects for light rail, streetcars, and redesigning streets and sidewalks.

Dennis Kucinich

Kucinich calls for federal financing of $50 billion in zero-interest loans every year for ten years. State and local governments could use the money to build roads and mass transit. States would have to repay the principal, but these bonds would pay zero interest. The plan would cut infrastructure improvement costs in half.

Al Sharpton

Sharpton advocates spending $50 billion a year over five years on highways, railways, and infrastructure.

George W. Bush

In 2002, President Bush guaranteed an increase in the Department of Transportation funding level with $6.7 billion, $486 million earmarked for expansion projects in mass transit. The Bush administration provided Amtrak with $521 million to continue operating.

In December 2003, the Department of Transportation announced $2.85 billion in grants to build a new PATH terminal, connect 12 subway lines in a new Fulton Street subway station, and replace the South Ferry subway terminal in lower Manhattan.

• • • • • • •

Back to Urban Issues Main Page

• • • • • • •

GOTHAM GAZETTE’S RELATED ARTICLES

• Urban Agenda: Mass Transit

• How New Yorkers Get to Work

• New Subway Projects and their Benefits

• Same Projects, No New Money

• Debating Transportation in Lower Manhattan

• Permanent PATH Station

How New Yorkers Get To Work

Debates about transportation often focus on big construction projects such as the Second Avenue subway, the extension of the #7 subway line and a new transit center on Fulton Street in lower Manhattan. One might think from this that the only means of transportation in New York is the subway to Manhattan. But, according to recently released data from the 2000 census, less than a third of New Yorkers take the subway to work in Manhattan.

Of the 3.7 million people who work in the five boroughs of New York City, 2.1 million work in Manhattan. (That's 56 percent. The other 44 percent work in the other four boroughs). Of the 2.1 million who work in Manhattan, 1.2 million take the subway or a commuter railroad to get to work.

The homes of these 1.2 million workers are not spread evenly throughout the city. As Map 1 below shows, commuting to Manhattan by subway is more prevalent among workers who live on the Manhattan's west side above 59 Street, in lower Manhattan west of Broadway, and in certain neighborhoods in western Queens and western Brooklyn.

Of those taking other forms of transportation to work in Manhattan, 53,000 regularly take a taxi, 163,000 walk to work, and 245,000 take the bus.

Another 360,000 people drive to their Manhattan jobs. Map 2 shows, not surprisingly, that auto commuters live disproportionately in the outer parts of the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island in areas with poor transit access to Manhattan and/or very long transit commutes. Even in these areas, however, no more than 15 percent of workers drive to Manhattan.

In sum, the Manhattan jobs powerhouse plays a huge role in the lives of residents of Manhattan as well as those of Astoria, Sunnyside, Forest Hills, Brooklyn Heights, Red Hook and Park Slope. The arc of neighborhoods from Forest Hills in Queens to Park Slope in Brooklyn might be thought of as part of Metropolitan Manhattan, providing relatively high-paying jobs as well as shopping and entertainment to residents of these areas.

As to the rest of the city, there are two basic commuter profiles. The first group is commuters who take transit (subway or bus) to non-Manhattan jobs. Map 3 shows that this group is concentrated in central Brooklyn and parts of the Bronx. One-third to 40 percent of commuters living in these areas take transit to non-Manhattan jobs, most of which are in their home borough.

The final group is comprised of workers who drive to non-Manhattan jobs. In eastern Queens, the northeast section of the Bronx and southeastern Brooklyn, auto commuters going to non-Manhattan jobs constitute 40 percent or more of workers living in these areas. These workers are the least like the typical New York commuter since they do not work in Manhattan and drive instead of taking transit. In this respect, these workers fit the national profile of commuters more than the New York profile.

Amid the diversity of New York, then, three main commuter profiles are evident:

- The subway commuter to Manhattan;

- The subway/bus commuter to outer-borough jobs (mostly in workers' home borough); and

- The auto commuter to outer-borough (and sometimes suburban) jobs.

The first group is concentrated in or near the Manhattan core, the second group in the neighborhoods somewhat further from Manhattan, and the third group in the outermost parts of the outer boroughs.

What does this profile mean for thinking about transportation improvements? First and perhaps most obviously, it raises the question of what type of transit improvements would serve non-Manhattan subway, bus and auto commuters.

Second, these data point to areas that transit may help to continue to transform New York even without any new subway construction. One such area is along the L and M lines in Williamsburg, Greenpoint and along the Brooklyn/Queens border. Only one-quarter to one-third of workers living in these areas take the subway to work. These areas are already becoming more attractive to Manhattan professionals who may be priced out of housing in Manhattan. The once-dowdy L train has acquired some cachet. This trend is likely to continue.

Thus, not only subway lines that might be built, but lines built long ago but currently underutilized, will shape New York's urban landscape.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Taxis

Â

Next time you're standing on a corner in rush hour, muttering in frustration because you can't get a taxi, consider this:

Next time you're standing on a corner in rush hour, muttering in frustration because you can't get a taxi, consider this:

In 1937, when Fiorello LaGuardia was mayor and a youngster named Joe DiMaggio was the toast of the town, 13,566 licensed taxis patrolled the streets of New York.

Today, LaGuardia is an airport, Joltin' Joe's name is affixed to the West Side Highway and there are just 12,187 medallion cabs in the city, a decrease of 1,379. And on a rainy night, it seems like every single one of them is occupied.

The taxi is a vital component of New York's transportation system and a part of the city's history, culture and identity. Yellow cabs carried 240 million passengers in 2002 -- more than 50,000 New Yorkers use taxis as their primary means of getting to work every day (not counting commuters who take cabs from the railroad terminals) -- and they cover some 800 million miles of asphalt each year. Yet cabs and their drivers, among the most regulated of the city's institutions, are also a frequent source of confusion and aggravation.

Now, the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission is proposing a major overhaul of the taxi system, making some of the most visible changes since the city ordered all medallion cabs painted yellow in 1967.

Chief among these is a plan to add 900 taxis over the next three years, the largest increase in almost seven decades. Because taxi medallions currently sell for more than $200,000, the city, which would issue 300 of them in each of the next three years, expects to gain about $190 million, a third of which is already included in this year's budget.

With the increase in the number of cabs would come a fare hike expected to be roughly 25 percent.

Together, these moves are touted as a way of making additional cabs available, easing a shortage that often leaves riders stranded in rush hours and inclement weather, and raising pay for drivers who have not seen the fare increase since 1996.

But not everyone is eager to see these changes.

Additional taxis on the streets will create more pollution and more traffic congestion. Some drivers and owners also worry that more cabs will mean more competition, less pay, and a decline in the value of taxi medallions. And New Yorkers, who are already weary from increased taxes and rising subway and bus fares, are not happy to endure another hike.

"I think that in this economy, when people aren't prospering, it's a lousy time to introduce a fare increase," said Angela Dirks, an architect who takes a taxi at least once a day.

CHECKERED PAST

New York first regulated taxi fares in 1913, fixing the cost of a ride at 50 cents a mile. The Great Depression brought a huge influx of drivers as the unemployed sought to make a buck any way they could, and the explosion in the number of taxis depressed wages and sparked tensions between large fleets and independent owner-drivers. The system grew rife with corruption and labor strife, including a 1934 taxi strike that was the subject of the first play by Clifford Odets, "Waiting for Lefty" (starring future film director Elia Kazan), which became a smash hit, the audience joining in with the actors at the end as they chanted "Strike! Strike! Strike!"

In 1937, LaGuardia attempted to bring order to the chaos by issuing licenses - the first medallions -- for ten dollars apiece. Although the medallions ended the free-for-all that existed for much of the 1930s, they severely limited access to the industry.

As a result of their scarcity, the medallions skyrocketed in value. Owners, seeking to protect their investments, successfully campaigned to prevent the city from issuing new medallions. Due to attrition, the number of medallions actually shrank.

Proposals by the Lindsay, Koch and Dinkins administrations to raise the limit on medallions were soundly defeated. It was not until 1994, under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, that city was able to add another 400 yellow taxis.

The high price of medallions led to the two-tier taxi system that the city now has. Medallion cabs began to focus on the central business districts and the airports because that was the only way to generate enough revenue to justify the high price of a license, leaving the rest of the city to car services or so-called "gypsy" cabs.

Meanwhile, buying and selling the valuable medallions has become an industry of its own, with brokers, consultants and lenders who specialize in financing such purchases.

Medallion Financial Corp., a publicly traded company that, as its name implies, finances medallion purchases (its Nasdaq ticker symbol is TAXI), boasted in a press release just last week that over the past 70 years, taxi medallion prices have risen over 13 percent per year, outperforming the stock market for the same period.

That big rise in medallion prices, particularly in the last 20 years, has also brought about a sea change in the way the taxi industry is structured.

A CHANGING INDUSTRY

For decades, medallion owners operated large fleets of cabs and hired salaried drivers - think of Alex, Elaine, Iggy and the other drivers for the Sunshine Cab Company on the TV series Taxi.

By the time "Taxi" went off the air in the early 1980s, however, such arrangements were already becoming a thing of the past.

Medallion holders got out of the operations business and started charging drivers a fee to use their cars for a 12-hour shift. Around the same time, increased immigration brought an influx of drivers lured by the low barriers to entering this line of work. Pay went down even as the fees drivers had to pay for cabs rose to as much as $100 per day.

It was around this time that the image of the cabbie as a raconteur and crusty but endearing veteran of the streets gave way in the public mind to that of an immigrant who drove recklessly and knew little about the city. (That is, when the public was not picturing a deranged Travis Bickle, as played by Robert DeNiro in the 1976 movie "Taxi Driver".) In response, the city made an effort to educate cabbies and require that they speak English.

September 11 and the ensuing recession made things worse for cabbies, cutting into ridership for the first time in decades. A study released in September 2003 by the Taxi Workers Alliance, which represents 4,800 of the city's 40,000 drivers, said that some drivers took home as little as $22 per shift after expenses and 62 percent were behind on their rent and bills.

Taxi industry officials disputed the precise figures in the survey, but there is general agreement that rising costs have been hurting drivers since the last fare increase almost eight years ago.

SELLING MEDALLIONS - MORE CABS VS. MORE TRAFFIC AND POLLUTION

The sale of 900 medallions proposed by the city would be the largest since the LaGuardia years.

Bruce Schaller, a former Taxi and Limousine Commission official who runs a consulting firm that focuses on the taxi industry, has written about the problems in the taxi industry in his Transportation topic page on Gotham Gazette. He believes that the proposed sale of medallions would result in a noticeable improvement in taxi service.

"I think more cabs are needed to serve the longtime growing demand for service and the industry," Schaller said.

Although 900 cabs over three years does not sound like a lot of additional vehicles, the majority of them will be concentrated in Manhattan below 96th Street, the most congested part of the city.

To critics of the plan, including several environmental groups, that is exactly the problem. Most of these cabs will be in motion throughout the day, adding substantially to the number of vehicle miles on the city's streets. Also, because taxis travel an average of 64,000 miles per year, they are responsible for far more emissions than private automobiles.

"If you make it easier to take a cab people will go from public transportation to taxis." said Noah Budnick of Transportation Alternatives, an organization that promotes bicycling, walking and public transportation. "It's not like you're replacing a car trip with a taxi trip."

The Taxi and Limousine Commission's environmental statement, prepared by the engineering firm Urbitran Associates, concludes that the city can accommodate the extra taxis if it changes the timing of many traffic lights so that they show green for an extra second during each cycle.

The study also maintains that the extra pollution will not be a problem because the city has dramatically improved its air quality in recent years. And it insists that there will be no significant impact on noise in the city because the additional cabs will be operating on different shifts and would be spread out across a large area of the city.

MORE CABS EQUAL MORE COMPETITION

However, some taxi drivers believe there is no justification for additional cabs. They worry that more cabs will mean more competition, less pay, and a decline in the value of taxi medallions. To them, the city is merely trying to grab revenue.

"The city wants to raise money without raising taxes," Bhairavi Desai, the director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, told The New York Times recently. "But the mayor shouldn't balance his budget on the backs of taxi drivers, who work 70 hours a week."

Many argue that a fare hike must accompany an increase in the sale of medallions.

"We do believe that there needs to be a fare increase for current medallions to retain their value and in order for new medallions to bring in the amount the city expects," said Michael Woloz, of the Metropolitan Taxi Board of Trade, a group that represents about 20 percent of the industry. "It's a good investment but only if the owner of the medallion and the driver of that cab can make a good a living."

FARE HIKE - BETTER PAY VS. RIDER BACKLASH

The base fare for a cab ride is $2, and each additional one-fifth of a mile costs 30 cents. Between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m., a night surcharge of 50 cents is added.

In recent months, drivers have threatened to strike if the fare is not increased. Officials are currently proposing a 25 percent hike.

Several drivers testified before the Taxi and Limousine Commission last week that there is a shortage of cabbies because the pay is so low. As a result, many taxis never even make it out of the garage. Supporters of a fare hike say it will go a long way toward making things more equitable for drivers and offset the effects of additional medallions by making each cab more profitable.

But taxi industry representatives also claim that everyone, even riders, will benefit if the fare is raised.

"We believe that if a fare increase is approved that people will invest in the industry and get more cabs on the street to serve the riding public," said Woloz.

David Pollack, executive director of the Committee for Taxi Safety and editor of the Taxi Insider newsletter, agrees it's time the city stopped playing politics with the taxi fare.

"It's been a hot potato," said Pollack, who is also a part-time cab driver. "We would like to see a review every two years so the public doesn't have to get hit with a big increase. Three, four or five percent every two years doesn't hurt as much as 20 percent in one shot."

But if taxi fares increase, some fear a backlash from the public.

A fare increase typically means that more people choose to take public transit or walk. Also with ridership already down, a recent article in City Journal questioned the rationale of raising fares now.

"As the businessman-mayor will remember from Econ 101, you don't respond to sagging demand by raising prices," wrote Howard Husock. "You will only chase more customers away, so that every dollar you gain in higher fares will be lost by decreased ridership."

Even some drivers caution that they may not get to keep the increase; leasing companies, they say, could raise their fees, leaving drivers with little in the way of extra income. Several drivers, speaking on January 7 at the Taxi and Limousine Commission hearing, said the plan would squeeze drivers' incomes while offering riders false hope.

While Pollack of Taxi Insider supports the 900 more cabs as a good start -- "there will be 900 happier people every few minutes in this city, especially in the rain and cold and in rush hour" -- he is philosophical about what the increase will accomplish. In the end, he believes, no amount of additional taxis will satisfy everyone: "If they put on 900,000 medallions, maybe - maybe - there'd be enough taxis."

#####

Related Links

• Taxi and Limousine Commission

• New York Taxi Alliance

• Medallion Financial Corp.

• Committee for Taxi Safety Transportation Alternatives

• Cab Watch - Program to include taxi drivers in bringing safety to the streets.

• Fare Policy - A paper by Bruce Schaller about the effect of fare hikes on the taxi industry

•Checker Cabs - a Web site about a once-ubiquitous kind of taxicab that no longer exists on NYC streets.

#####

New Subway Projects And Their Benefits

The New York City subway, which celebrates its 100th anniversary next year, was built to provide faster and less crowded transit service than the street cars they replaced, and thus to open new areas of the city for development. One hundred years later, the next generation of proposed new subway lines embraces very similar goals. The proposed Second Avenue subway, for example, is intended to relieve severe overcrowding on the Lexington Avenue subway and create faster, more direct travel options from the Upper East Side to Sixth Avenue in Midtown. East Side Access, which will bring Long Island Rail Road trains into Grand Central Terminal, will shorten the commute for thousands of LIRR riders who work near Grand Central. The proposed extension of the #7 subway line in Manhattan would spur office and residential development on the Far West Side.

While these and other big-ticket transit projects have many benefits, the city clearly cannot afford all of them and must thus decide on priorities. Unfortunately, comparing the relative merits of different projects is no easy task. A new report released by the Partnership for New York City, a prominent business group, takes up the daunting challenge of estimating the costs and benefits of seven major Manhattan-oriented transit projects. The results of the report, "Transportation Choices and the Future of the New York City Economy," are surprising, provocative and hotly debated.

The partnership report focuses on two types of benefits - transportation benefits and economic development benefits. Transportation benefits are based on the value of savings in personal travel time, waiting and walk times, changes in the number of transfers and reduction in overcrowding and congestion. Time savings are translated into dollars based on the value of the saved time to travelers.

The partnership report tallies economic benefits based on the value of new office and residential space constructed as a result of better transit accessibility and increases in property values, jobs, incomes, retail sales and tourism.

The value of transportation and economic development benefits are then compared with the cost of constructing the project. The table below summarizes benefits as a percentage of costs, a standard way of comparing projects.

|

Benefits of Seven Transit Projects

(Net Present Value for Next 50 Years) |

Project Economic Benefits as

Percent of Project Cost |

Transportation Benefits as

Percent of Project Costs |

| Farley/Penn Station |

878%

|

46%

|

| #7 train extension |

640%

|

65%

|

| Lower Manhattan Transit Hub |

522%

|

136%

|

| East Side Access (LIRR to Grand Central Terminal) |

161%

|

70%

|

| Second Avenue Subway |

82%

|

55%

|

| Access to Region's Core (tunnel from NJ)* |

54%

|

48%

|

| PATH to Newark Airport* |

10%

|

38%

|

* Projects include only benefits to New York, not New Jersey. Source: NYC Partnership

The most striking aspect of this table is that economic benefits are far larger than transportation benefits for most of the projects. Of course, the two are closely related; faster and more comfortable commutes to work make the city a more attractive place for employers and employees. But these results suggest that the economic benefits of transit projects should be weighed at least as heavily as the transportation benefits. The partnership, reflecting its business orientation, thus brings to the fore the question of which transit projects generate the greatest economic development "bang for the buck."

At the top of the list are the Farley/Penn project, which expands the existing overcrowded Penn Station into the Farley Post Office building; extension of the #7 train to Manhattan's West Side; and the Fulton Street Hub in lower Manhattan, which will connect PATH trains to subway trains and try to rationalize the tangle of subway lines at Fulton Street. Each of these three projects returns five to nine times its cost in economic development benefits and one-half to 1.36 times its costs in transportation benefits, according to the partnership report.

Of these three projects, the most attention has focused on the #7 extension because financing for the Fulton Street Hub and Farley/Penn projects is essentially in place. Indeed, the partnership report recommends building the #7 line extension "because it will generate significant economic development benefits and is essential to the redevelopment of the Far West Side."

Another striking result is that the Second Avenue subway, long prized by transportation advocates as the number one priority for subway system expansion, comes out in fifth place on the list. According to the partnership report, the Second Avenue subway returns only 82 percent of its cost in economic benefits and only 55 percent of costs in transportation benefits.

These figures are relatively low in part because the Second Avenue subway is projected to take 17 years to complete. Given the long construction timetable, the partnership recommends consideration of phasing in the project. Much of the benefit of Second Avenue would be realized from the segment north of 63rd Street, which would allow trains to run down Second Avenue, then across 63rd Street and down Broadway in the center of the island. It may be possible to open this "stubway" segment while the rest of the line is under construction.

Not surprisingly, advocates of the Second Avenue subway are unhappy with the partnership report, which can be seen to undercut the case for federal funding of the project. The Regional Plan Association (RPA), a long-time proponent of the line, points out that the partnership report leaves out of its calculation certain benefits from Second Avenue such as environmental benefits of attracting auto users to transit and social equity considerations such as the Second Avenue subway's potential to spur economic activity in Harlem. The partnership report is thus not a complete cost/benefit analysis.

RPA also points out the "network" benefits of the Second Avenue subway. The concept of network benefits is that building one line adds to the overall subway system in ways that have impacts throughout the city. Ironically, some of the higher-ranked projects need the Second Avenue subway to be viable. For example, adding LIRR passengers to Grand Central will put additional strain on the Lexington Avenue subway line unless the Second Avenue is built. Likewise, extending the #7 will create additional demands on the Lex and Grand Central Terminal. The partnership report agrees that a full network analysis should be conducted and might yield different results than the report's project-specific analysis.

The biggest difference of opinion between the Partnership for New York City and Regional Plan Association lies in how each side values transportation and economic development benefits. The partnership report estimates that the benefit of Second Avenue in reduced travel time, reduced crowding and fewer transfers totals $0.97 billion annually. Taking into account the assumption that the line will not open for another 17 years, the report calculates the transportation benefits of Second Avenue over the next 50 years as only $8.4 billion, using a net present value methodology that discounts the value of future benefits and costs.

By contrast, the Regional Plan Association assumes that the line can be built in 12 years rather than 17 years. The association also calculates a somewhat higher annual transportation benefit of $1.26 billion instead of $0.97 billion. Transportation benefits thus total $12.8 billion over the next 50 years rather than $8.4 billion.

Using a higher assumption for the amount of office, retail and medical space that would be spurred by the Second Avenue subway, the association estimates $23.1 billion in economic development impacts compared with $12.6 billion in the partnership report.

Clearly, all of these calculations are highly sensitive to the assumptions used to calculate economic development and transportation benefits. Both the Partnership for New York City and the Regional Plan Association acknowledge that more work needs to be done to make the analysis more reliable.

Even though the numbers are somewhat rough, the staggering size of potential economic development from the #7 extension underscores the possible viability of new methods of financing development on the Far West Side. Daniel Doctoroff, deputy mayor for economic development and rebuilding, is leading the city's efforts to develop the Far West Side into a mixed use office and residential neighborhood and to prime this "Hudson Yards" development plan with a new football stadium that would help attract the Jets and the 2012 Olympics. According to the Daily News, Doctoroff believes that the project could conceivably be financed based on the incremental tax revenue from the development. The city is now seeking bids from investment banks to help finance $2 billion in development, some of which would go to the #7 extension.

The theory on the Far West Side is, in simple terms, build it, they will come, and the tax revenues from the development will pay for the project. If the theory holds for the Far West Side, tax increment financing might also be applied to other transit projects.

The final and most fundamental question raised by the report concerns the city's potential for economic growth and the role of transportation, office and housing development in bringing about the growth. Economic development experts have long viewed additional housing and transit capacity as prerequisites for long-term job growth in Manhattan. The fundamental question is not so much whether these are necessary prerequisites, but whether they are sufficient conditions for growth. Now that New York is the safest big city in the country - crime having been a major deterrent to growth a decade ago -- will better transportation accessibility and additional housing spur large increases in jobs and population?

The Partnership for New York City report highlights the importance of this question but is far from providing the definitive answer.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Staten Island Ferry Crash Remains A Puzzle

One very simple question lies at the heart of the investigations into the October 15 crash of the Andrew J. Barberi ferry into a Staten Island pier, which killed 10 people and injured dozens of others: Why didn’t the vessel slow down as it approached the pier? National Transportation Safety Board investigators have found that the ferry was moving at nearly its top speed when it hit the pier. Investigators have also concluded that the ferry had no mechanical problems and have found no illegal drugs, no alcohol and no prescription drugs in the pilot’s blood.

The ferry’s pilot, Richard J. Smith, suggested in a brief statement immediately after the crash that he had lost consciousness. The captain, Michael J. Gansas said on the same day that he was in the pilothouse of the ferry and tried to stop the ferry from slamming into the pier. This initial story quickly fell apart, thanks to eye witnesses, but thus far, neither Smith or Gansas have been talking.

The second puzzle about the accident involves where Gansas should have been during docking. City officials say that standard operating procedures require the captain to be in the pilothouse. Yet the New York Post reports that 10 former or current ferry workers said that the city notified them of this requirement for the first time on November 3, two weeks after the crash. The Post reports that city officials were unable to prove that employees had been notified of the rule prior to October 15. Ferry workers said that it was standard practice for the pilot and captain to be at opposite ends of the boat, with one handling dockings on the Staten Island side and the other handling Manhattan dockings. According to the workers, “ferry bosses” were well aware of that practice. Gansas’ lawyers are now hinting that their defense will claim that captains were never required to be in the pilot house during docking.

A third puzzle about the crash is why city officials are acting so surprised about the accident. City transportation officials point out that the Staten Island ferry has experienced “no major accidents” in its 98-year history. Yet the ferry’s history of minor accidents and near misses suggest that it was only a matter of time. Two hundred passengers were injured in 1978 when the ferry crashed into a seawall, and a December 1992 accident injured no one but caused $120,000 in damage to the vessel. More importantly, the New York Times reports that Coast Guard investigations concluded that mistakes or acts of negligence contributed to these and other accidents. Coast Guard recommendations were never implemented, however, a fact noted by subsequent Coast Guard investigations. In fact, after a September 1998 accident that injured two passengers, the Coast Guard recommended that two crew members be present in the pilot house to watch for potential problems as the ferry approached the terminal. Had that recommendation been put in effect, the October 15 accident might never have occurred.

A fourth puzzle thus is why the Coast Guard safety recommendations were not implemented. The Times reports that ferry operations vary widely from one captain to another. Each ferry is run as a virtual fiefdom of the captain. The Times concluded that “tradition and habit often trump formal procedure” on the ferries. The New York Observer adds another factor – patronage. The Observer reports that ferry workers were protected so long by politicians that workers did not even bother to hide the fact that many do not live in the city, as required by city policy. This context may help explain the lack of follow-through on the Coast Guard’s simple recommendations for corrective action.

A fifth and perhaps the most important question is whether the city will now fix the ferry. One would like to see the city identify the systematic problems with ferry procedures, training and supervision that contributed to this and previous accidents. Indeed, city transportation officials say they are exploring whether new safety procedures need to be developed.

But the city’s initial actions give the appearance that the city is focused on assigning blame to individual workers. Questioned about whether workers had received the standard operating procedures, a spokesman for the City Transportation Department said simply, “The captain is ultimately in charge of the ship.” As to the rest of the crew, the city required all ferry workers to sign an acknowledgement that they recently received the standard operating procedures. The city is also taking steps to ensure that ferry workers live in the city after press reports that Gansas actually lived in Haslet, New Jersey. These steps rather beg the issue of whether the crew is properly trained and supervised.

Ferry safety will apparently require not only clearer procedures, better training and more vigilant supervision, but given comments by a former senior ferry worker quoted in the Times, also a better understanding of what safety requires. This former official said he would put Staten Island ferry officers “up against anyone at Cunard or anywhere else. They’re stone-cold professionals.” But this same former official said that having a second officer assist in docking “would be redundant and necessary only if someone is gong to have a heart attack or some type of episode.”

Yes, well, exactly. Even on the cute little Staten Island ferry, redundancy could be a very important part of safe operations.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.

Bruce Schaller is Principal of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis to government, business and non-profit groups seeking to identify and meet customer needs in the transportation sector. He is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.