Private Report Card on Smaller Parks

There are wide disparities in the conditions of New York City's neighborhood parks, according to a "report card" recently released by New Yorkers for Parks, a non-profit advocacy group for parks. These are the smaller parks and playgrounds, the basketball courts and playing fields, the leafy spots where senior citizens sit on benches and chess players look for a game.

Almost a quarter of the parks received at least 90 percent for their excellent condition, and another 36 percent earned a 70 or above with reasonably well-kept lawns or playing fields, safe and clean playgrounds, and benches and paths in good repair. But a significant number had bedraggled plantings, dusty, uneven or littered fields, and bathrooms that were locked or out of order. Twenty percent of the parks got a failing grade, 59 or below. Parks in Manhattan and Staten Island fared the best.

Overall, the report card found much better conditions in the areas where the parks department has focused capital investment in recent years - playgrounds, sitting areas, and paths and sidewalks. Citywide, these features received an average score of 80 to 83 percent. The areas most in need of improvement were the active and passive recreation areas, as well as the bathrooms and drinking fountains. The average grade for bathrooms citywide was 48. The authors of the report noted, "In too many cases, existing bathrooms were either locked or desperately in need of maintenance and supplies."

The report card was compiled from a detailed survey of 181 of the city's 220 parks that are from one to 20 acres in size, conducted in the summer of 2002. (Parks not surveyed were either closed for renovation or lacking the park features on which the survey focused.) Trained staff from New Yorkers for Parks graded each park for cleanliness, maintenance, safety and structural integrity in eight "major service areas" - active recreational areas; passive recreational areas; playgrounds; sitting areas; bathrooms; drinking fountains; sidewalks, streets and paths; and how well the park is insulated from the surrounding environment. The group developed its rating system through focus groups with community members and park experts, aiming to assess park conditions from a user's perspective.

Some of the report card's conclusions differ from the parks department's highly regarded Parks Inspection Program, geared to improving park management and maximizing resources, and using somewhat different criteria. The department visits 200 parks a week, with 5,000 inspections annually, and finds 85 to 90 percent in acceptable condition. The department's web site posts the citywide results and will be adding park by park data this summer.

Regarding the park amenities that have improved and those most in need of attention, the parks department found the survey in line with their own assessments, according to a parks department spokesman. Deputy Commissioner for Operations Liam Kavanagh provided a statement that said, "Through our rigorous inspection program and direct experience, we know that the condition of our parks is strong citywide. We have identified and launched programs to address the same major service areas identified by New Yorkers for Parks in their report card." Among the programs under way to address these issues is the renovation of ball fields with artificial turf - so far, 21 such fields have been put in, with 11 more under construction, and 17 in the planning stages. Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe has also launched a large horticultural initiative that includes training parks maintenance staff in gardening basics. The department's "Operation Relief" targets drinking fountains to fix them and make sure they are turned on.

New Yorkers for Parks conducted the survey to quantify the varying conditions at the smaller, low-profile parks, which are mostly dependent on public funding. The goal, said the group's spokesperson, Rowena Daly, "is to use these results to understand where our parks are failing and draw together public and private support to lift up neighborhood parks in greatest need."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Dog Runs

|

|

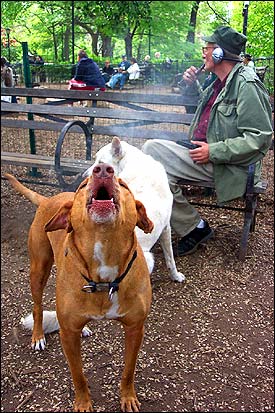

| Sounding off at First Run, New York City's first dog run. |

Mahatma Gandhi said that a society can be judged by the way it treats its animals. But in New York, another criterion may be how people treat each other when disputes over animals arise. The most contentious of such disputes center around dog runs:

• When the city first began constructing a playground on 42nd Street, a group of dog owners who opposed it sent a letter to the mayor calling the playground a "frivolous, costly, and ultimately wasteful construction."

• When dog owners at the Washington Square run became suspicious that a common water bowl may have spread a viral infection among dogs, they called in a veterinarian to examine the bowl. A pro-bowl contingent hired their own vet for a second opinion.

• At a community board meeting, a resident compared dogs in Stuyvesant Park to packs of wild dingoes in Australia who have been known to attack humans. The audience booed him.

An article in Governing Magazine, which tracks trends in local government, cites dog regulations among the most rancorous issues cities face today - on the same level as taxes.

The limited amount of park space in New York makes dog runs a particularly difficult issue, according to former Parks Commissioner Henry Stern, who helped found the city's first one in 1990.

"It's simple," said Stern. "For dog owners, they are a pleasure. For others, they are a nuisance."

FIRST RUN

New York City's health code forbids animals from being off a leash, but for years dogs have been allowed to run free in certain parks. When incidents do occur - people or other dogs get bitten, flowers are dug up, or poop goes unscooped - the Parks Department or police often respond with a crackdown on leash law violators.

Following a series of complaints and a crack-down on free-range dogs in the early 1990's, former Commissioner Stern came up with a compromise that would allow for some off-leash hours at certain locations.

Thus the city's first dog run came into being - aptly named "First Run" - in Tompkins Square Park in the East Village.

Today, there are 26 official dog runs in the city, according to the Parks Department. Central Park features some gathering places for dogs, but no official fenced-in runs.

Prospect Park in Brooklyn provides one of the largest and most lenient off leash areas in the city. But that's not enough for some Brooklynites. "There are many many owners who, for a variety of reasons, cannot let their dogs off leash in wide open spaces," writes Elizabeth Heeden, calling for an enclosed dog run in the park, on the Park Slope Gazette, one of Gotham Gazette's interactive community pages.

Proponents contend that in addition to creating a place for pets to play, dog runs are where New Yorkers can meet and build a sense of community. In this way, dog runs are not really about animals, according to Jeffrey Zahn of the New York Council of Dog Owners Group, which represents some 15,000 dog owners in the city; they are about people.

"A common mistake is that the issue is about the dog's rights, when it's not," said Zahn. "Dog owners are just one of many groups in the city competing for a limited amount of space."

Opponents counter that dog runs are a smelly, noisy, and poor use of the city's limited parkland.

"It's dusty, dirty, and they act like they own the place," said Laurel Harrington, a student who frequently studies in Washington Square Park. "I like dogs and they're cute, but of all of the things that happen in this park, the dogs are the only thing that makes it smell."

Even some dog owners are wary of dog runs because they fear for the safety of their pets. One of the most popular topics on the message boards of the website urbanhound.com, which touts itself as "the city dog's ultimate survival guide," is berating owners who cannot control their pets.

"Washington Square Dog Run has been getting too rough lately because of the people who either don't watch their dogs or correct bad behavior," one posting reads. "It's not always a safe place for small dogs to roam freely. I cannot risk my smallest dog's life there any longer."

Then there are those owners - who the responsible dog people argue give others a bad reputation - that ignore dog runs completely, because they do not think their companions should be fenced in.

In 1996, a woman was arrested in Central Park for letting her Bichons Frises, named Baby and Sugar, run off leash. After trying to run away, the woman, who was married to an Italian count, was wrestled to the ground and handcuffed to a bench for 45 minutes. "It's not like a herd of wild dogs," the countess reportedly said. "And even if it were it's not like they don't deserve a place to run."

CREATING A CANINE PARADISE

About a year ago, Olivia Lee had a seemingly simple goal: she wanted to start a dog run for her beagle-mutt Max.

So Lee, who had no experience in such a civic project, selected a rarely used handball court in a park on the corner of 35th Street and Second Avenue as her chosen spot. She founded a website, www.murrayhilldog.com and collected over 700 signatures of support. But when she took the idea to her local community board, Lee realized her battle was just beginning.

"One person said, `I don't know if you are new to the neighborhood, Missy, but your dog run is not going to happen,'" Lee recalled. "The person actually called me `Missy.'"

Gary Papush, of community board 6, said that the board always considers serious proposals, but that frankly the neighborhood is facing more pressing issues.

"If David Letterman did a top ten list of the major concerns of community board 6, dog runs wouldn't make the list," said Papush.

The encounter between Lee and her community board is a common, and by New York City standards, fairly tame example of the tensions that exist over dog runs. Getting just a few square feet of park space set aside for pets can take years, hundreds of thousands of dollars, and a lot of political lobbying.

"It can take anywhere from six months to ten years to get a dog run," said Jeffrey Zahn of NYCDOG. "My advice is to keep a sense of humor and be patient."

Even though local community boards do not have the power to block a plan, they still often hold the key to whether a plan is approved or rejected. If a community board is in favor of a run, it has a much better chance of being approved by the Parks Department. (Click here for a step by step guide to starting a dog run.)

But it is not just founding a dog run that takes effort; it is maintaining one after it is approved. The city's dog runs operate like miniature governments with their own elected leaders, rules, and committees.

One of the most successful, and well respected, organizers in the city is Mary McInerney, who runs FIDO, the Fellowship in the Interest of Dogs and their Owners.

Five years ago, many city parks began putting an end to off leash hours. Prospect Park in Brooklyn has no dog runs, and so McInerney approached Tupper Thomas, the administrator of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and offered to self-police dog owners. Now each evening, hundreds of dogs and their people enjoy off-leash hours in several meadows. In return, the owners must abide by a strict set of rules including keeping their dogs under control, picking up waste, ensuring no holes are dug, and staying away from horses and ball fields. The fine for breaking any rule is $100.

McInerney's mission is not only to educate owners in "responsible supervision," but to be a kind of liaison to anti-dog New Yorkers.

"Some people are afraid," said McInerney. "A lot of people who live their lives in the city have had a limited experience with animals, whether it's dogs, cows, or ducks."

POWER TO THE PUPS

While dog owners may not enjoy the political power of real estate, labor unions, or racial voting blocs, dog owners do make their presence known in local politics.

In 2001, the New York Council of Dog Owners Groups (NYCDOG - pronounced "nice-dog") organized a rating system for local candidates to make sure they were educated on leash laws as well as rent regulations and tax policy.

Over 80 candidates responded - including three Democratic mayoral candidates Fernando Ferrer, Peter Vallone, and Mark Green. Michael Bloomberg received a rating of "In the Dog House" for his failure to answer.

At a recent forum on how to run for political office, West Side City Councilmember Gale Brewer spoke to a room of future candidates and told them that along with fundraising, organization, and a rolodex full of contacts, dog runs were an essential part of a successful campaign in New York City.

"I don't own a dog," said Brewer, "But I hit the dog runs so often that when the dog groups did their endorsements, I got four paws."

Do you have issues with dog runs in your neighborhood? Visit the Community Gazette homepage, find your neighborhood, and post a message under "COMMUNITY VIEWS – Ideas to Improve Your Neighborhood."

RELATED LINKS

• New York Pet Policies (Gotham Gazette)

• Urban Hound - City Dog Survival Guide

• Dog Lawyers

• Ratings of NYC'S Dog Runs

• New York Council of Dog Owner Groups

• Parks Department Dog Run Info

• Dog Licenses

RELATED ARTICLES

• Sidewalk Cafés

• Car-Free Parks

• It Happens Every Spring (Overview)

Car-Free Parks

|

|

| A bicycle club enjoys the Central Park drive in 1895, four years before the arrival of the automobile. (Photo courtesy Transportation Alternatives.) |

In 1899, the newly-formed Automobile Club of America was granted the first permit to drive a car in Central Park. For the previous five decades, only pedestrians, bicycles, and horse-and-carriages had been allowed.

Many New Yorkers did not like cars in the park then – a 1906 letter to the New York Times bemoaned the "ugly, noisy, and evil-smelling" automobiles – and some still don't like it today.

Nearly a century and a half after they were built, some would like to see Central Park and Prospect Park in Brooklyn returned to their original purpose.

"The parks were not designed for cars," said Aaron Naparstek of the organization Transportation Alternatives, which has been lobbying for car-free parks for the last 20 years. "Because of the curves, you can only see 40 to 50 feet in front of you, which makes driving dangerous."

There have been accidents in the past. A woman cyclist was struck and killed by a van in Prospect Park in 1997. Two people were hit in Central Park in 1998.

Both Central Park and Prospect Park already have some car-free hours. Automobiles use the drives during morning and evening rush hours during the summer. (See blue box for car-free hours)

But advocates want to ban cars 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Opponents argue that banning cars from the parks completely would actually make the city less livable. Automobiles would be forced onto side streets, creating havoc for drivers and the surrounding neighborhoods.

"I simply don't see a compelling public need that justifies displacing thousands of cars into the surround area," argued Alvin Berk of Brooklyn's community board 14.

THE POLITICS OF CAR FREE PARKS

Support for car free parks has been growing in recent years. Environmental groups, running clubs, some former transportation commissioners, and the majority of the City Council members that represent the neighborhoods adjacent to both Central Park and Prospect Park are in favor of the idea.

But victories are still hard to achieve and even those are small. This winter the city agreed to close Prospect Park to cars for a few more hours a week as a trial period.

|

The major groups standing in the way, advocates say, are the mayor and Department of Transportation and the Parks Department.

"The Department of Transportation looks at those parks and sees unused road capacity," said Naparstek.

The city argues that it is balancing the needs of all New Yorkers with a compromise of car and pedestrian only hours.

"We want to balance the various needs of the residents so everyone can benefit," said Transportation Commissioner Iris Weinshall.

Until the mayor or the borough presidents hear enough outcry, there is little incentive for the parks to change their policies. And some of the most outspoken opposition comes from neighborhood residents or those who commute to work or school through the park areas.

Alvin Berk of community board 14 says residents fear not only more traffic, but also increases in accidents, higher exhaust emission in neighborhoods, and a reduced quality of life.

"It's not just a matter of inconveniencing drivers," said Berk. "Our concern is for the safety, well being, and health of residents."

BATTLES IN THE STREETS

Passions of drivers and pedestrians can sometimes run high.

During car-free hours in Prospect Park, some motorists have become so incensed, that they climb out of their cars, move the barricades blocking the entrance, and keep on going. Earlier this year, the park had to ask the 78th police precinct to step up enforcement.

And in their efforts to rid parks of cars, activists sometimes resort to environmental guerrilla tactics to battle their 3,000 pound steel enemies.

In recent years, activists armed with plants and banners erected a human barricade across Grand Army Plaza in Prospect Park. Or when a cyclist is killed, an outline of a body is often spray-painted on the city street.

And each month, bicyclists gather for what they call Critical Mass to ride as a group through the city streets, boxing in cars, and blocking intersections to protest for pedestrian rights. At times, the groups grow to include hundreds of cyclists, who will stop in the middle of a major intersection, lift their bikes into the air and chant slogans like "No More Cars!" while motorists honk their horns and curse.

Do you have issues with cars in your parks? Visit the Community Gazette homepage, find your neighborhood, and post a message under "COMMUNITY VIEWS – Ideas to Improve Your Neighborhood."

RELATED ARTICLES

• Dog Runs

• Sidewalk Cafés

• It Happens Every Spring (Overview)

Reviving the Filtration Plant Underneath Van Cortlandt Park

The Bloomberg administration has been quietly working to resuscitate the controversial plan to build a water filtration plant under the Mosholu Golf Course in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx. That plan was declared dead a year ago, when the State Supreme Court ruled that building in the park was an "alienation" requiring approval by the state legislature. By tradition, the legislature almost never approves the taking of parkland over the objection of the legislators from the district where park is located.

The city needs to build the facility in order to comply with an order from the federal Environmental Protection Agency to filter and treat the part of the city’s water that comes from the Croton watershed. The city is under a court order to come up with a plan by April 30th.

The New York Observer reported that the administration has been lobbying Bronx elected officials for months, and has gained the support of two key politicians, Assembly member Jose Rivera, the Bronx Democratic county leader, and Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion. According to the local Bronx papers, Christopher Ward, commissioner of the city Department of Environmental Protection, met with Bronx members of the Assembly at the Bronx Democratic Party headquarters in March to present his department’s case for putting the plant in Van Cortlandt Park. He said that it would save the city between $200 and $500 million over the alternative sites, and keep jobs in the Bronx.

The agency has scaled back the original plan, reducing its size and putting it completely underground, with the golf course’s driving range rebuilt on top. The original design called for the plant to rise to a height of 30 feet at one end. Originally, the Mosholu Golf Course was to be closed during the four years of construction, but the new plan would keep it open, although the driving range would still be closed. The department has also made promises of greater funding for Bronx park projects.

The city says that the plant could be built more quickly at the Van Cortlandt site because all the environmental reviews have been completed. Park advocates dispute that, saying that because of the changes in the plan a new Environmental Impact Statement is required. They also note that new security issues have arisen since September 11, and want to know how the city would be able to allow recreational use on top of and next to a potential terrorist target.

Assembly member Jeffrey Dinowitz, who represents the district, and local residents are outraged at the Bloomberg administration’s efforts to fast-track alienation legislation, and are organizing to fight the project all over again. Park advocates are concerned that putting the filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park could set a dangerous precedent. "We can’t take parkland because it’s the cheapest option – it’s always going to be the cheapest option for the city," said Christian DePalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, a citywide parks advocacy group. "It’s land held in the public trust."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Report Card On The Parks

Politicians are reluctant to make specific promises to which they can be held accountable. Mayor Michael Bloomberg, determined to apply business principles to running the city, not only made such promises for what he would do if elected mayor, but he has now issued a "report card" listing the 380 proposals he made and how many of them he has accomplished in his first year.

The report card rated 80 percent of the proposals either "done," "launched," or "to be launched in 2003." But it is interesting to take a closer look at the scores he has given himself to see how the mayor's report card matches the facts.

The 58-page document included more than two dozen proposals, large and small, in the category of parks and open space. The mayor considered seven "done" so far, 15 "launched," and six "not done" or "reconsidered." Mayor Bloomberg has indeed fulfilled many campaign promises on parks in just one year, and has been particularly effective in carrying out promised policy changes and negotiating solutions to difficult situations. Sometimes, especially in the "launched" category, his grades might be a bit padded, since in some cases the only accomplishment is issuing a memo in support of proposed state legislation or contacting another agency for discussions. In other cases, he has just continued existing projects. The mayor also took credit for something that is not actually being done. And one unfulfilled promise, perhaps the most important one, was left out of the report card altogether.

Following is a rundown of some of the park-related campaign promises and what Mayor Bloomberg has or has not done to keep them:

COMMUNITY GARDENS

One of the major park-related achievements of the Bloomberg administration has been negotiating a settlement of the community garden lawsuit, resolving one of the most bitterly fought battles of the Giuliani era. The lawsuit, by state Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, had temporarily blocked the city's plans to raze hundreds of community gardens for development. The compromise protected 198 gardens while leaving 114 gardens open to possible future development, subject to a review process. Another 38 gardens, which had already been through the city's land use process, were released for sale or development without further review. Although the final agreement did not please all parties and has left community gardeners with some unanswered questions about the status of the gardens that were saved, it protected hundreds of community green spaces in neighborhoods where parks are scarce.

BLOOMINGDALE PARK

The mayor worked out a compromise between the Staten Island borough president and the parks department that will allow ball fields to be built in Bloomingdale Park, which the mayor promised Staten Island voters even though the project was opposed by environmental groups.

SUPPORT EFFORTS TO TURN THE HIGH LINE INTO A PARK

A mayoral commission appointed to study the feasibility of creating an aerial green promenade on the abandoned West Side rail line "launched" this proposal. Also, in December 2002, the city applied for a Certificate of Interim Trail Use for the High Line from the Surface Transportation Board, reversing the previous administration's efforts to demolish the track.

RETURN CONCESSION FEES TO PARKS

The parks department does not get to keep the $60 million raised through concessions for restaurants, golf courses and other commercial enterprises in the parks; the money goes to the general fund. Mayor Bloomberg promised in the campaign that he would give this money back to the parks department, but nothing has been implemented yet. He did return $2 million collected from corporate sponsorship in the parks to the department - with half the money credited against budget cuts.

FIND ASPHALT AREAS APPROPRIATE FOR ARTIFICIAL TURF TO ALLEVIATE THE SHORTAGE OF BALLFIELDS

Expanding an ongoing program, the parks department installed nine synthetic turf fields on asphalt areas in 2002 and plans to install 21 more in 2003 - although whether this will actually happen because of future budget cuts is anyone's guess.

OPEN CITY HALL PARK

Mayor Giuliani beautifully restored City Hall Park and then kept it off limits to the public, ostensibly because of security concerns. Mayor Bloomberg has reopened most of the park.

DEVELOP A GREENWAY AROUND MANHATTAN

Pieces of this waterfront pedestrian and bicycle route have been built over the last decade, following a plan created by the Department of City Planning in 1993. Bloomberg has given the greenway a large boost through his enthusiastic support. The report card designates this proposal "launched," with a new section on the Harlem River recently opened and an interim route due to open in the summer of 2003. It also says that the parks department is in discussion with the United Nations and various state and city agencies on the next step for completing the long-term route.

ENSURE A PRESENCE IN PARKS WHEN PEOPLE ARE THERE BY HAVING A SECOND SHIFT OF WORKERS ON DUTY

Most park maintenance and operations staff work an early shift, leaving the parks by 3:30 p.m. The department has established a second shift, staffed mostly by seasonal playground associates and Parks Enforcement Patrol officers, to get more employees in the park during times of peak usership. But there is still a very small staff presence in most parks most of the time. (The exceptions are parks with private funding like Central and Bryant parks.) There are just 51 playground associates citywide, one for each city council district, and 158 Parks Enforcement Patrol officers (with 100 actively patrolling the parks) for the city's 1,700 parks. Further budget cuts could eliminate the playground associate positions this summer.

FERRY POINT PARK REMEDIATION

Under the campaign proposal to "clean brownfields that can be used as parks," Mayor Bloomberg took credit for "brownfields remediation work" in Ferry Point Park, a former municipal landfill in the Bronx that is being turned into a championship-level golf course. But in fact, golf course construction has proceeded without the usual remediation techniques generally applied to former landfills and other brownfields sites - no efforts to keep toxic dust stirred up by construction from blowing on nearby residents, no impermeable barriers to seal off the decaying garbage and its load of chemicals, no testing or collecting of the rainwater percolating through the dump. Explosive and possibly contaminated methane gas produced from decomposing trash is being vented, not through tall pipes as is usual, but an open trench that runs through a community park. The "clean-up" consists only of piling on nearly 2 million cubic yards of construction and demolition debris (that the developer gets paid to take), then covering it with soil and grass.

Bloomberg should subtract points from his score for allowing work to proceed without the proper cleanup of the underlying site, endangering the residents of the nearby homes and housing project. He is also leaving the city open to enormous potential liability because the concession contract granted during the Giuliani administration exempts the developer from responsibility for any environmental contamination stemming from the former landfill.

WORK TO COMMIT ONE PERCENT OF THE CITY'S ANNUAL BUDGET TO PARKS

Mayor Bloomberg seems to have forgotten to grade himself on one of the most important promises of his campaign to parks advocates: to double city funding for parks to one percent of the city budget. The city's financial difficulties have obviously prevented him from keeping his pledge, although the parks department now gets an even smaller piece of the pie than in previous years, .0357 percent. But because this promise is absent from the report card, it is impossible to tell if the mayor hopes eventually to fulfill it or is reconsidering.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Turning Parkways Into Parks? Turning Trees Into Sports Fields?

If the state legislature approves, Staten Island could gain 500 acres of parkland and finally put to rest a long abandoned highway plan dating back to the era of Robert Moses and the 1930s. A bill, introduced by Assembly members Robert A. Straniere and Michael Cusick and State Senator John Marchi would officially abandon plans to complete the Willowbrook and Richmond parkways and transfer the land intended for the highways to the state Department of Environmental Conservation and the New York City Parks Department. Much of the land, which is now under the jurisdiction of the state Department of Transportation, is in the heart of the Greenbelt, 2,800 acres of parks and natural areas in the middle of Staten Island.

The two parkways were part of a plan to speed traffic across the island between New Jersey and Brooklyn. Three separate studies over the past 20 years — by the Metropolitan Transportation Council, the City Department of Planning, and the State Department of Transportation — found that the highways would not ease the real traffic problem in Staten Island, which is local congestion from people traveling within the island. Although the state does not ever plan to build the highways, the land has remained under the control of the transportation department, which has issued permits for park-and-rides and other projects on it, avoiding the usual review process.

"People could see that if this is allowed to continue, then gradually this open space is whittled away," said David J. D'Ermilio, an aide to Straniere. He said that in addition to preventing the gradual encroachment of development into the heart of the Greenbelt, the proposal, called a demapping bill because it would remove the highways from the official map, would eliminate uncertainty over the highways and offer a cost-free way to add parkland to the city in bad fiscal times.

The legislation has support from residents who live in the Greenbelt, numerous Staten Island civic associations, and city and regional environmental and planning organizations. But the chairmen of the three Staten Island community boards, whose members are appointed by the borough president, issued a press release saying that they will not support abandoning the highways "until plans for improving all local streets impacted by the loss of the roadways are finalized," according to the Staten Island Register. Borough President James Molinaro's office declined to comment on Straniere's bill, but said that he would present his own proposal soon at an editorial meeting with the Staten Island Advance.

The community board chairs worry that, if sections needed to widen or straighten local roads become park, those projects could be stopped because state legislation would be required. The bill's supporters say, however, that the park bill would have no practical effect on the process of approving roadway widening plans, because any road changes on the land already require state legislation to resolve questions of title, a city land use review process and various other public reviews.

BALL FIELDS WIN AT BLOOMINGDALE WOODS

A bitter three-year battle over a plan to put recreational fields in Staten Island's Bloomingdale Woods came to an end with a snowy ceremonial groundbreaking in early February. Mayor Michael Bloomberg dug into a pile of dirt instead of the frozen ground to inaugurate a scaled-down version of the project, a compromise he negotiated between the Parks Department, which originally opposed the project, and its chief proponent, Staten Island Borough President James Molinaro. The compromise also involves building additional fields at the nearby Charleston site, most of which is slated for a retail complex.

While South Shore sports leagues and civic groups celebrated, former Parks Commissioner Henry Stern characterized the groundbreaking as a "dark day in park history," although he gave the mayor credit for reducing the size of the project, "so it's far better than the earlier plan."

The Parks Department and environmental groups opposed the project because thousands of trees would be cut down and wildlife habitat destroyed, and because they believed the park's sloping and soggy terrain would be unsuitable for playing fields. A study commissioned by the Parks Department showed that fields could be built more quickly and far more cheaply at other sites on the South Shore. "From the moment this controversy began, parks offered them recreational fields on flat lands," said Stern.

Former borough president Guy Molinari, however, had plans for the other potential sites, none of which were under the jurisdiction of the Parks Department. He made the building of fields in Bloomingdale Woods a top priority and used his political clout to win the support of former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. The mayor silenced the Parks Department and had the project moved to the Department of Design and Construction.

Environmentalists, led by the local Protectors of Pine Oak Woods, sued to stop the project, raising the ire of sports and civic groups on the South Shore. In recent years, the area has developed rapidly, without an accompanying investment in schools, recreational facilities, public transit and other infrastructure. "We have all these new homes and new developments, huge new developments, I might add, and there is no place for these children to go," said Dee Vandenburg, president of the Staten Island Taxpayers Association, a civic organization addressing quality of life issues.

Protectors lost its final appeal last summer.

Chuck Perry, a board member of Protectors, said that he agreed that the area needed ball fields and recreation for the children. But, he said, "we should be upgrading the areas that are degraded, not cutting the natural areas we have left." He noted that a privately owned forest near Bloomingdale Park was recently clear cut for a large development. Perry also said it was "fiscally irresponsible" to spend three or four times the money to build fields in an area not suited for them.

To Mike Nagy, the borough engineer who did the redesign, the natural setting is the key to the appeal of the park. "Engineers can build many things," he said, "but we can't build fully grown trees." Nagy envisions the park, with three ball fields, two half-court basketball courts and a playground surrounded by trees, to be like a park somewhere in Connecticut — "where kids can sit under a tree and have lunch, where the temperature in the summer can be ten degrees cooler that it is on the street, where you can take a walk and see a ravine."

The final $9.1 million plan for Bloomingdale Park, which also includes a perimeter greenway, walking trails, bridges, and wetland boardwalks, is scheduled to be completed in the spring of 2004. An additional $6.5 million has been allotted for roadwork to increase access to the park, including two cul-de-sacs leading into the park. At the Charleston retail site, 42 acres will be transferred to the Parks Department, which will build a new 42-acre park with 12 acres of ball fields, tennis and basketball courts, and a fitness trail. The Staten Island Advance reported that the Parks Department has asked the contractor of the retail complex to provide a $7 million maintenance endowment for the new park, which is expected to be ready in the fall of 2004.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Crime, Christo and Car-free

IS CRIME INCREASING IN THE PARKS?

A burst of violent crime in the parks has alarmed park advocates and raised questions about whether the parks are becoming less safe. In the past five months, there have been two murders and four rapes, including a brutal attack on a woman by five homeless men who were living unnoticed at the edge of Flushing Meadows Park in December.

There is no way of knowing if crime is increasing in the parks. Compstat, the New York Police Department´s computerized crime-tracking process, analyzes patterns of crime by precinct. According to the police, crimes that occur in parks are included in the precinct data, but the police department doesn´t break out information specifically on parks. The only park for which crime data are available is Central Park, which is a separate precinct. There, major crimes increased very slightly last year, from 127 to 132. Citywide, crime remains at a low level after declining dramatically in the last decade.

The parks department´s Parks Enforcement Patrol, or PEP, officers serve as a deterrent to crime by patrolling the parks, enforcing rules, and issuing summons for a variety of quality-of-life offenses. They have many other functions as well, including crowd control, first aid, and ice rescues. But after two decades of staff reductions at the parks department and the most recent round of budget cuts, there are very few officers actually in the parks. According to Joe Pulio, vice president of Local 983 of District Council 37, the union that represents the PEP officers, there are about 100 officers doing active patrol work in all five boroughs. They are stretched the thinnest outside of Manhattan, with 9 in the Bronx, 12 in Brooklyn, 7 in Queens, and 6 in Staten Island. (These numbers don´t include supervisory staff, officers stationed at recreation centers, or those who work at special events.) The high-profile and privately funded Manhattan parks, like Central and Bryant parks, have their own police or security forces.

Short of staffing up the Park Enforcement Patrol force – wishful thinking with the city´s current budget problems - park advocates say there are some steps the city could take to fight crime more effectively in the parks. At a recent news conference at City Hall, the park advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks and several city council members, including parks committee chair Joseph Addabbo, made several recommendations.

They called for the creation of a separate Compstat process to identify recurrent problems in the parks, which the police can miss because many large parks are divided among several precincts. Also, the police sometimes record a crime in the park at the closest street address, rather than a park location, according to Joe Pulio, whose union supports the recommendations of the park advocates.

They are also recommending putting the PEP officers under the supervision of the NYPD, as the city has done for school, housing, and transit officers. This would lead to more effective policing by improving communications and coordination between the PEP officers familiar with the parks and the police, park advocates said.

The Daily News reported that NYPD spokesman Michael O´Looney and Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe "politely rebuffed" the proposals, although Mayor Bloomberg has previously endorsed the idea of upgrading the Parks Enforcement Patrol officers and putting them under the control of the NYPD.

CHRISTO TO WRAP CENTRAL PARK

A quarter of a century after it was first proposed, the temporary artwork "The Gates" by Christo and Jeanne-Claude will be installed in Central Park. For two weeks in February 2005, 7,500 gates hung with saffron fabric will line 23 miles of park pathways. In making the announcement, Mayor Bloomberg said, "'The Gates' represents the latest provocative and innovative addition to our city´s grand tradition of public art." When the project was first proposed in 1979, it provoked an outcry from New Yorkers and was rejected by the parks department.

CAR-FREE TRIAL IN PROSPECT PARK

Prospect Park has begun a three-month experiment of banning cars during the weekday (except rush hours) in the winter. Until now, there were no car-free hours in the park during winter weekdays. The park is always closed to motorists on weekends and holidays.

Bicycle and pedestrian activists have long campaigned to keep cars out of the park completely. But some residents fear that the move will increase in traffic on local streets to intolerable levels. After the trial period, which ends April 4, officials will assess the impact on traffic in neighborhoods around the park.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Golf Clubbing Bronx Residents? Also: When Stadiums Win, Do Parks Lose?

Environmental groups and residents of a nearby housing project are suing to stop the construction of a golf course at Ferry Point Park, a large and neglected tract near the Whitestone Bridge that was once a municipal garbage dump. The groups charge that the city pushed ahead with the project without fully investigating potential health and environmental threats. They claim that the city and state accepted the results of an inadequate environmental assessment conducted by a consultant hired by Ferry Point Partners, the golf course developer, bypassing the more thorough environmental impact statement that would usually be required for a brownfields redevelopment project like this.

The developer began work last summer, clearing the land and bringing in fill for the project, which besides a golf course also includes a 7-acre community park across from the housing project and a 19.5-acre public waterfront park and esplanade. The course has the vigorous support of the local community board and city officials. They note that the developer is paying for it, not the taxpayers, and that environmental watchdog agencies approved it. Parks Commissioner Henry Stern called the lawsuit "frivolous." City Councilwoman Madeline Provenzano, who represents the Throggs Neck area, said, "This group didn't surface until everything was a 'go.' It's been planned and thought about for a good long time."

But the environmental groups got involved at the request of housing project residents, who were upset when the golf course plan was changed to block access to the waterfront from their side. The residents also told of their concerns about the old dump and health problems in the community.

The Ferry Point landfill was closed in the 1960s, although illegal dumping continued for years afterward. It was one of many dumps throughout the city that were closed before laws were enacted to regulate the disposal of solid and hazardous waste. At that time, industrial chemicals ended up in many municipal landfills (five other city dumps of that era are now listed by the state as hazardous waste sites), although no evidence exists that this occurred at Ferry Point. But even household trash contains small amounts of chemicals and heavy metals that are leached out by rainwater, combining in a toxic brew called leachate that can seep into rivers, lakes or groundwater. Decomposing garbage also produces methane and other combustible and toxic gases. Modern landfills are engineered to prevent the spread of these wastes. Ferry Point was not

The city eventually covered part of Ferry Point with a layer of soil and let nature take its course, but the dump was never properly sealed or monitored. Longtime residents say that during the 1970s and 80s, spontaneous methane fires frequently broke out during the heat of summer. In the early 1980s, according to an affidavit by Lehra Brooks, a resident of the housing project, numerous complaints about the fires, foul odors, blowing debris, and health problems led to community meetings with the Parks department and Community Board 10. Tests at that time showed the presence of chemicals that, while not dangerous individually, could be toxic or combustible when combined. Brooks recalled that the city promised to clean up the site, but nothing ever came of it.

The recent environmental assessment conducted by the developer found toxic chemicals in the park, including volatile organic compounds, DDT, lead, arsenic, and PCBs. The state Department of Environmental Conservation determined, however, that the levels were too low to be a health threat. Methane was also detected, requiring modifications in the golf course plans. Department spokeswoman Jennifer Meicht said, "We've thoroughly evaluated the potential environmental and health impacts related to the site, and we're confident that, as proposed, the project will be fully protective of public health and the environment."

The New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and the other parties to the suit (the New York Public Interest Research Group, the Throggs Neck Houses Resident Council, and the Blue Angels Radio Control Model Airplane Club) disagree, noting that the environmental review didn't delve into the history of the dump, test groundwater, or address the possibility that the construction could force methane to migrate to the basements of houses near the park. "We want to see the site thoroughly investigated," said Michael Livermore, an environmental associate at the New York Public Interest Research Group. The groups are also concerned about potential contaminants in the 750,000 cubic yards of construction debris being used to top the landfill. This phase of the project required a permit from the Department of Environmental Conservation because the developer is essentially operating a construction and demolition landfill. The permit calls for extensive oversight to make sure the fill is "clean" (as defined by the department, which does allow for some level of contamination), but Meicht said she had no information yet about the monitoring.

Anne Sounds Off: Stadiums 3, Parks 0?

Why does it often seem that when stadiums win, parks lose? There is always public money for another new stadium, but private groups are increasingly expected to pick up the tab for maintaining our parks. Sometimes, actual parkland is taken away for sports arenas. And at the same time that commercial sports venues are promoted, a crying need for playing fields and recreation is ignored. To our shame, New York City has the fewest public recreational facilities per capita of any major city in the United States.

Two new minor-league baseball stadiums, for the Yankees in Staten Island and for the Mets in Brooklyn, are expected cost the taxpayers about $150 million. The mayor has offered to pay one-third of the cost of a proposed new stadium on the West Side, this time being promoted for both the Jets and a long-shot 2012 New York Olympics bid. Estimated costs for that project are $1 billion for the stadium, and another billion for the necessary infrastructure. And these figures don't include the additional services (like police, transit, fire, and sanitation) that will be needed to support the stadiums when built.

The Parks department's entire operating budget is about $150 million a year, about half of what it was in the mid-1980s. The reason Central, Prospect and other showcase parks, especially in Manhattan below 110th Street, look so good -- in spite of 64 percent reduction in Parks maintenance staff in the last decade -- is that they have the financial support of affluent neighbors or the business community. But go to parks in the poorer neighborhoods of Queens or the Bronx, say, and you'll find a different story. The Parks department has also been able to compensate for the loss of maintenance staff by using thousands of Work Experience Program workers to clean the parks. The results of this were documented in a recent study by the City Independent Budget Office, which also shows that the number of those workers is now declining.

In an article in the Daily News reporting that New Yorkers oppose public funding for a stadium on the West Side by a 3-1 margin, Mayor Giuliani was quoted as saying, "Very often, people misunderstand economic development. I don't agree with them." With all due respect, there is one aspect of economic development that the Mayor doesn't understand. Although economists have found a poor return, in terms of jobs and economic growth, on taxpayer subsidies for stadiums, studies have shown that public investment in well-maintained parks does pay real economic dividends. Among other things, it increases real estate values, reduces crime, and draws tourism. It also makes a city more attractive to people and businesses looking to relocate. Money magazine's Best Places to Live 2000 listed good parks among its criteria: "Along with our usual emphasis on solid schools, low crime and job growth ... we also wanted areas ... where city fathers have put a premium on green space ..."

Sure, sports teams have their place in our city and our hearts. But putting public funds into our public parks, instead of building more stadiums -- now that would be a fabulous legacy.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Budget cuts and the parks

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's recent proposal to patch the enormous hole in the city's budget includes the inevitable budget cuts, as well as tax increases and new revenue sources like bridge tolls. The cuts will squeeze all city agencies, parks included. But unlike past eras of austerity, the pain seems to be distributed more evenly, an indication that this administration sees parks as an important factor in the city's quality of life. "Our sense of it is that the parks department has been treated like other agencies," Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe said, "where in the past, the parks department was cut disproportionately, treated as if it were a non-vital service."

These new budget cuts, however, fall on a department whose funding has already been reduced to a minimum. According to the Independent Budget Office, money for maintaining and operating the parks and providing recreation programs was never fully restored from the cutbacks of the previous recession in the early 1990's. The parks department's share of the city budget has also declined, from .65 percent in 1991 to .52 percent in 2001. (It was .82 percent as recently as 1986.) "Parks have been cut in the good and bad times, drastically over the last 30 years," said Christian DiPalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, a parks advocacy group. "We would hope that City Hall and the mayor would consider exempting further cuts from parks because of this history."

HOW WOULD PARKS BE AFFECTED?

The mayor's proposed adjustments to the parks budget would require combined cuts and new revenues of $8.7 million for this fiscal year and $18.6 million for the next. The department would lose 157 fulltime workers through attrition and reduce the number of street trees pruned by a third this year and by half next. There would also be an increase in the fees charged for the use of ball fields, tennis courts, recreation centers, and parking at Yankee and Shea stadiums. Except for the yearly recreation center fees, which mostly go back to the centers to cover their expenses, the rest of the new revenue would go to the city's general fund and be used as an offset to cuts.

Commissioner Benepe said there will be some impacts - water fountains and sprinklers might take longer to get turned on in the summer because of fewer plumbers, supervisors will be managing more people, and playgrounds that formerly had attendants in the summer won't have them. But, he said, "we should be able to maintain the overall quality of parks; people should not see a diminution of safety and cleanliness."

The funding reductions will further erode a fulltime staff that has declined steeply over the last 30 years. The number of fulltime employees has dropped from more than 6,000 in 1970 to about 2,000 in 2001. This labor pool has been replaced by seasonal workers, as well as by participants in welfare-to-work programs, who are paid by the Department of Human Resources, using federal and state money. The welfare workers fill the parks department's need for large numbers of people to do unskilled work, like raking, cleaning, and painting. "The welfare-to-work program is at the core of how we deliver se rvices," Commissioner Benepe said. The parks department now has 4,000 welfare-to-work participants, although in recent years the number has dropped at times to around 2,000. The department trains the workers and helps place them in jobs outside the department.

What the parks department has not been able to replace with temporary and seasonal staff are the skilled workers needed to tend trees and plantings and to keep plumbing in working order. Decades of staffing cuts have left the department with very few gardeners, tree pruners, and plumbers. According to the IBO report, by 2001, the department had only 12 fulltime gardeners for the entire city, down from 30 in 1991. (Central Park alone, which is funded almost entirely through private donations, has 73 gardeners.) During that time, the number of tree pruners declined from 99 to 55, and the number of plumbers from 30 to 18. The staff reduction slated for this year and next would further deplete the department's skilled staff.

THE SPECTER OF THE 1970s

In presenting his budget plan, Mayor Bloomberg stressed that the situation is not as bleak as the 1970s, when the city drastically cut services, stopped maintaining its infrastructure, and all but abandoned the parks. "This city is not going to cut its expenses below where the quality of life would start to deteriorate," he said.

Still, people are worried. "We're hearing from community groups that they're fearful that parks are going to return to the 70s when people were afraid to walk through dilapidated parks," said Christian DiPalermo. "We do think the commissioner is doing everything to avoid that in the way he manages the parks."

The parks are also in a different position than they were in the 1970s. Having come back from the abyss, in part because of partnerships with private groups like the Central Park Conservancy, the parks now have a vocal and committed constituency. The private sector contributes about $50 million a year for the maintenance and restoration of parks and facilities, and for programs, although the benefits have flowed mostly to parks in affluent areas. A network of 60,000 volunteers, with a core group of 5,000 to 10,000 people who work regularly, provides about $10 million in labor each year.

Although Commissioner Benepe is optimistic that donors will rise to the challenge and increase their support, the city can't rely on private funding alone. If the State Legislature and City Council don't approve the mayor's plans for increasing revenues, there could be deeper service cuts. Parks need regular maintenance, especially those that are heavily used. There is not much room left in the parks budget to cut before the downward spiral of the 1970's begins again.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

State Protections For City Parkland

Cities and towns are frequently tempted to use parkland for other public needs or commercial uses. Local governments are called on to widen roads, improve public transit or water systems, build schools and housing, and encourage economic development. Sometimes, a park is the most practical, or most expedient, site. Actions by municipalities may affect parks in other ways -- for example, through the draining of wetlands to build ball fields or the rerouting of traffic next to a park. State law in New York (and many other states), however, helps hold off potential park intrusions, as a number of recent and ongoing New York City park controversies illustrate.

The Public Trust

The major state safeguard for parks is known as the parkland, or public trust, doctrine, a widely accepted legal principle that parks are to be kept for the people. In New York, this doctrine is part of the common law, a body of law established through judicial decisions that recognizes rights that are generally agreed upon by society. New York State's common law is rooted in the centuries-old English common law brought here by the colonists.

The state courts have repeatedly ruled that if land has been dedicated as a park -- or, in some cases, used as a park consistently for many years to the point where it has been recognized as public space -- it cannot be "alienated," or taken for a non-park use, without the approval of the State Legislature.

This doctrine was invoked by the state Court of Appeals, the state's highest court, when it ruled that the city could not proceed with its plans to site a federally mandated water filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park unless it got approval from the New York State Legislature. According to the city's plans, building the plant would have required closing the park's golf course and driving range for five years. The finished plant was to be partially underground, rising to a height of 30 feet at one end, with the driving range rebuilt on top. Residents of the adjacent neighborhood opposed the plan, as did the local state legislators, making legislative approval unlikely.

Public trust law also allowed Tribeca residents to sue to resurrect Canal Street Park, one of the city's first public parks. It was a small but elegant space first created by Ignatz Pilat and later remade by Samuel Parsons, both eminent landscape designers. The park fell into disrepair, and in 1929, without legislative approval, it was transferred to the state Department of Transportation and paved over to use during the construction of the West Side Highway. In recent years the city used it for parking garbage trucks. "This was one of those lawsuits that had a happy outcome," said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe. As part of its reconstruction of Route 9A, the state Department of Transportation agreed to build a new park. The design, by the department and the city parks department, is inspired by a combination of the two original versions, according to the commissioner, who said they hope to have construction under way by next spring.

In Staten Island, a controversy is brewing over the use of beaches for public transportation and commuter parking, a possible alienation of parkland. The city recently turned over a parking lot at South Beach to commuter parking during the week. The Staten Island Advance recently reported that the Port Authority is proposing to build a high-speed ferry pier and commuter park-and-ride lots somewhere on the beachfront, possibly Midland Park. Jim Scarcella, president of the Staten Island-based Natural Resources Protective Association, said, "If they're going to use our parks for purposes other than they've been intended, we're going to request they do the full act of the State Legislature that's required to do this."

Even when an alienation is approved, state law provides leverage to get something equivalent in exchange -- new parkland or park improvements -- as mitigation. The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation publishes a guidebook on the process, which can be requested by mail from the Counsel's Office, Empire State Plaza, Building 1, 19th Floor, Albany, NY 12238.

A proposal for the United Nations to erect an office building on Robert Moses Park, an asphalt yard and dog run on 42nd Street, would have to go through the alienation legislative process. The new tower would provide offices for the 5,000 people who now work in the Secretariat building while it is being renovated. Acknowledging the importance of keeping the United Nations headquarters in New York and allowing it to improve its facilities, Dave Lutz of the Neighborhood Open Space Coalition speculated about what the city might get in return for giving up the only park in that area: "For years, people have been looking for a greenway past the U.N.," he said. Parks Commissioner Benepe confirmed that an extension of the pedestrian promenade along the river near the United Nations is one option being discussed. "There is very little open space in that community," he said, "so it would have to be replaced on a square foot for square foot basis."

Environmental Protections -- Or Not

State environmental laws also can be applied to protect the integrity of parks and natural areas, though there are loopholes, and enforcement remains spotty. State law covers wetland areas over a minimum size, including those in parks, but only if the wetlands have been officially identified on agency maps, whose accuracy has been questioned. The State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) mandates a review of potential environmental impacts (the environmental impact statement, or EIS) for major land use changes. But projects are often allowed to proceed when the state accepts a preliminary "environmental assessment" concluding that no further review is needed.

A project also is not required to have an environmental impact statement if it is a replacement "in kind," noted Mark Caserta, Director of the Waterfront Park Coalition. He said that his group is concerned about the effects of the city's replacement of the bridges over the Harlem River. The work could shower lead paint on waterfront parks adjacent to the bridges, increase traffic and air pollution in the area, and use as staging areas sites earmarked to complete a greenway along the river. But, because no environmental impact statement is needed, the city will not have to mitigate the impact.

But the fact that environmental laws are on the books gives citizens and advocacy groups legal tools when fighting a project they believe would cause environmental harm. These laws have also had an advocate in Attorney General Eliot Spitzer. The Attorney General's office played a significant role in the Van Cortlandt Park case, and also sued to stop the city from selling or developing community gardens on city land.

In the community garden lawsuit, which was recently settled, the state based its case both on the State Environmental Quality Review Act and the public trust doctrine. Although the community gardens are not officially dedicated parks -- in fact, the city viewed them as quite the opposite, vacant lots temporarily growing tomatoes until a better use for them could be found -- the Attorney General's lawsuit argued that they had become parks by implication. "Some have been in existence for 20 to 25 years of continuous, uninterrupted use," said Assistant Attorney General Chris Amato. "They have large trees. They have benches. Some have amphitheaters. They have all the attributes of a public park, and are used that way by the community."

The lawsuit also maintained that developing the garden lots violated the environmental law because the city was proceeding to sell off or develop the lots without adequate environmental review or public input.

The final agreement released 38 gardens for the development of low-income and market-rate housing. These were the gardens that already had gone through the city's land review process. The largest number of gardens, 198, were offered transfer either to the New York City Parks department or one of the land trusts set up by two nonprofits that purchased more than a hundred threatened gardens several years ago. Gardens already under the jurisdiction of the Parks department, the Department of Education, and other non-developing agencies -- a total of 193 - will continue as community gardens. The remaining 114 gardens are subject to possible future sale or development, but only after a "garden review process" that is yet to be established. The city must offer an alternate site, which may or may not be feasible to the existing community gardeners.

As in the community garden issue, it can be a tough call whether a project is important enough to displace open space. Should senior housing, for example, take precedence? "Citizens take very seriously the value of the parkland at the end of their streets -- which is a double-edged sword, because sometimes there is a very good, rational reason to change the use of parkland," said Commissioner Benepe. "If there ever is a good, rational use for alienating parkland, we have to make sure we do our homework ahead of time, and make sure that substitute parkland is provided."

Sites For Beginners:

- Neighborhood Open Space Coalition's Treebranch Network-- Among the areas covered by this longtime advocate for New York City open space are greenways, community gardens, parks, the waterfront, and Gateway National Park. Subscribe here free to the electronic version of Urban Outdoors Bulletin, an excellent source of news about parks and related issues.

- NYC Department of Parks and Recreation-- It's easy to look up any park location, facility, program, or event at this site. You can also take a "virtual tour" (actually, more words than pictures) of several important parks in each borough, or design your own park by playing the NYC planner game. The "Daily Plant," circulated within the department, offers an inside look at park programs and events. Various park permits and applications, including a request for a street tree, can be printed and submitted through the site.

- OASIS-- An interactive site that lets you view NYC land use maps or aerial photos by borough, neighborhood, community board, or zip code, then zoom in on details like parks, community gardens, or vacant lots and obtain zoning and ownership information. There are some inaccuracies, but users can help update the information.

- Partnership for Parks-- A joint initiative of the City Parks Foundation and the NYC parks department. Under "What We Do," there is information about the Bronx River and other projects, citywide volunteer events, small grants programs, and many other efforts that help communities support and build constituencies for their parks.

- Trust for Public Land-- This national open space group has increased its focus on urban areas in recent years. It has helped save community gardens and negotiated the purchase of several new state parks in the city recently. The site provides frequently updated information on the trust's projects and open space issues nationwide. Look under "Research Room" for urban land conservation and federal and state funding.

- Urban Parks online -- An electronic toolbox for people working on city parks issues, from the Urban Parks Institute (part of the Project for Public Spaces, a NYC non-profit that aims to build community life through public spaces). The site brings together ideas from all over for creating, funding, and maintaining urban parks, and highlights park places and park news from around the country.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.