Adopt-A-Park

Dominic Ortiz owns a running store in Fresh Meadows, Queens. He is also president of the Quantum Feet Road Runners Club, which organizes group runs and sponsors races. So when he heard about the new Adopt-a-Park law the city recently approved, he was immediately interested in the possibility of the store and club adopting sections of the greenway that connects a number of parks in Queens. In addition to providing good publicity for his store, he said, "it would help promote our running club, which is a separate entity than the business. It would get people running in Queens – hopefully help us as we help them."

Ortiz is one of 30 individuals or groups who have expressed interest in adopting a park since the law was passed unanimously by the City Council and signed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in early September. The law authorizes the parks commissioner to make agreements with individuals or groups to sponsor a park, playground, ball field, or other park space or facility -- even park equipment like a lawnmower -- by donating a specific amount of money or labor. The payments are to be used only for the sponsored areas. The program does not include parks that already have conservancies or trusts contributing more than $500,000 a year.

Many groups and individuals already help out in their local parks, playgrounds, and gardens by cleaning, weeding, organizing activities for kids and paying for the upkeep of plantings, benches, ball fields, and other park elements. The Adopt-A-Park program is intended to reach out to more people and businesses and create a way for smaller donations to be directed to a specific park, according to Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, who chairs the parks committee and introduced the legislation. The law also provides a more transparent process for tracking the donations.

The Parks department has three months to put the program in place. Department spokesman Chris Osgood stressed that volunteer efforts and sponsorships that already exist will continue. The department views Adopt-A-Park as a way to package and promote the philanthropy and volunteerism that is already benefiting many parks. The department is developing a menu of opportunities for people to get involved, Osgood said, depending on the amount donated. This could range from adopting a bench or tree to a whole park or playground. Small and appropriate signage would recognize contributions ; no parks would be renamed.

Adopt-A-Park is directed particularly at the smaller parks in the outer boroughs that have most felt the impact of the decline in public funding for parks maintenance and recreation over the past 15 years. While many parks could benefit, the law could create a new set of inequities, bringing funding to parks in areas that have more businesses or well-off residents.

There is also the danger that increased donations may reduce the pressure on the city to fund what is truly a public service. Councilmember Addabbo said, "Written into the language of Adopt-A-Park is the fact that this is not to be in lieu of budgetary funding. We didn't want an influx of volunteers and funding, and out of the back have the funding taken out of parks and put somewhere else." He said that the council's oversight during the budget process would be a check on any attempt by the city to reduce its appropriations for parks because Adopt-a-Park can pick up the slack.

Businesses, groups or individuals interested in Adopt-a-Park can call 311 or Councilmember Addabbo's City Hall office at 212-788-7069. For more information, check the New Yorkers for Parks website.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

New Threat From Asian Long-Horned Beetle. Also: Van Cortlandt Park And The Water Filtration Plant

Bush administration budget cuts could set back efforts to eliminate the Asian long-horned beetle from the New York City area, leaving the city and the Northeast at risk for widespread damage to parks, forests and street and backyard trees, as well as to the maple syrup, lumber, fruit-growing, and tourism industries. Funding for the eradication program, run by the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in cooperation with local and state agencies, was cut to $26 million this year from $50 million last year.

The tree-killing beetle, first found in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, in 1996, was believed to have stowed away in wooden packing material used in shipments from China. It has since spread to a number of locations throughout New York City, including Central Park, Flushing Meadows Park, and Forest Park, as well as Long Island and New Jersey. A separate infestation was discovered in the Chicago area in 1998. Almost 6,000 trees in the New York City area have been cut and burned in the effort to wipe out the pest. The U.S. Department of Agriculture says the beetle has the potential to cause more devastation nationwide than Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight, and the gypsy moth combined.

As a result of the budget cuts, the service has had to reduce eradication efforts, particularly in Brooklyn and Queens, where it eliminated contracts with outside tree services that provided bucket trucks and tree-climbers to examine trees and also applied preventative pesticide treatments. Last year, the pesticide imidacloprid was injected into 134,000 healthy host trees – maples, ash, and other species preferred by the pest – in the entire New York quarantine zone, the areas of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island where the beetle has been found. This year, the service treated 18,000 trees only in Manhattan and Islip, focusing on places where it believes the pest is contained and could be eliminated entirely. "Ideally, we would like to treat all non-infested host trees," said USDA spokesperson Daniel Parry. "When we have times like this with limited funds, we want to work from the outermost boundaries and compress the infestation inward."

Representatives Anthony Weiner and Joseph Crowley, who represent Congressional districts in Brooklyn and Queens, are calling on the federal Office of Management and Budget to restore emergency funding it has provided in the past for the beetle eradication effort. In an August 5th letter to the budget office director, Joshua Bolton, they asked him to approve the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s $46 million request for the beetle eradication program.

The service continues to conduct tree-to-tree surveys in the entire New York City quarantine zone, although at a slower pace. Trees found to be infested are destroyed and replaced with a species not attacked by the beetle. "The biggest ally in all of this is the public," said Parry, asking people to report suspected beetle infestations to the toll-free number 1-877-STOPALB. "All calls are taken seriously - an inspector will come out," he said.

Signs of the beetle are perfectly round holes (slightly larger than the diameter of a pencil) bored in trunks; piles of sawdust at the base or crotches of trees; sap and water oozing down the trunk; and the villain of this real-life horror flick itself – a one to one-and-half-inch shiny black beetle with white markings and outsized black-and-white antennae. For more information check the TreesNY web site.

Van Cortlandt Park

Just hours before the deadline, Governor George Pataki signed legislation allowing the use of 48 acres of Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx for a water filtration plant. The city is under a court order requiring it to filter the water coming from the Croton Reservoir to meet federal water quality standards. After years of disputes on whether and how this should be done, the governor's decision cleared the way for the city to build a $1.3 billion plant underneath the park's Mosholu Golf Course after completing a supplemental environmental impact statement.

The governor approved the bill only after receiving assurances from Mayor Michael Bloomberg that the city would consider two other potential sites for the filtration plant in the required environmental review. The Bloomberg administration also guaranteed in writing that the governor would be included in the process that determines how $243 million promised for Bronx parks would be spent. The money, mitigation for the years-long loss of parkland and the traffic and pollution generated by the construction of the plant, was crucial in persuading Bronx politicians to vote for allowing parkland to be used for the plant.

Several large environmental groups supported the construction of the filtration plant after the city Department of Environmental Protection went on record with a promise to provide new protections for land in the Croton watershed, according to the New York Times.

Local residents and Assemblymember Jeffrey Dinowitz, who represents the community near Van Cortlandt Park, continue to oppose the plant. In an article in the Norwood News, they charged the legislators and governor with environmental racism for agreeing to put the facility next to a low-income, ethnically mixed community with high asthma rates. Opponents of the plant question whether a fair selection process is possible now that the Van Cortlandt site has been approved by the state. Friends of Van Cortlandt Park, the group that stopped the city’s first attempt to build in the park without legislative approval, may sue again if the promised environmental review is not conducted properly.

Christian DiPalermo, executive director of the citywide parks advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, said, "The shortcuts used by the city in taking Van Cortlandt Park for this water filtration plant set an alarming precedent for future park alienation cases and place all parkland at risk." The organization will be carefully watching how the city plans to spend the $243 million promised for Bronx parks. It has urged its supporters to ask city Controller William Thompson to make sure that the money really goes to improving Bronx neighborhood parks - not Yankee Stadium (which is officially on parkland).

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

How Park Improvements Affect Community Real Estate Values

Investing capital funds in parks can generate significant economic returns in the form of increased property values, but New York City is not making the most of this opportunity, according to a study released at the Great Parks, Great Cities conference, an international urban parks conference held in New York City last month.

The study, conducted by the accounting firm Ernst & Young and the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks, selected at random 30 parks from all over the city and analyzed the relationship between capital investments and how tax assessments differed between parts of the same neighborhood closer and farther from the park over the past ten years. It also chose six different parks, at least one in every borough, to examine more closely as case studies, looking at capital funding, planning, and community involvement and comparing real estate prices, tax assessments and turnover rates in areas next to the park with those in the broader neighborhood.

A more thorough analysis also would have included the maintenance dollars allocated to each park, but this data was not available because the parks department uses roving crews for most park maintenance.

The analysis found that simply upgrading a park does not automatically add value to the surrounding area. From the sample of 30 parks, 55 percent of the 15 parks with the largest capital expenditures had either no increase or a decrease in the value of the real estate surrounding them. "The conclusion was that you cannot just throw money at a problem and expect to get results," said the project’s director, Glenn Brill, senior manager of real estate advisory services at Ernst & Young.

The detailed case studies showed that capital spending has higher economic returns when it is part of a larger plan for the community and includes long-term maintenance as well as the involvement of local residents and organizations.

The best example of this in the study is Prospect Park in Brooklyn, where $103 million – including $78 million in city funds -- has been invested since the 1980s. The Prospect Park Alliance, a public-private partnership that operates the park, has planned and overseen the park’s gradual restoration, working together with a wide range of community organizations. It also raises private funds to help maintain and program the park. The study found that the gap between the average single-family home sale price in the "park impact area" of adjoining Park Slope and comparable areas of the neighborhood farther from the park widened dramatically from 1996 to 2000. Before 1996, prices closer to the park were from 90 to 170 percent higher. Between 1996 to 2000, the price spread increased to 300 to 600 percent, before leveling off to 150 percent as prices farther from the park continued to rise.

Brill said that the research underlined the need for the city to take a strategic approach to investment in parks and coordinate it with other aspects of community development, like housing and policing. He also stressed the need for continued maintenance to preserve the city’s investment. "Our study supports the concept that a well-maintained park can make a significant contribution to real estate values," he said. "In doing so, it’s generating wealth for the owners and certainly a portion of it will be recirculated through the New York City economy."

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Our Project for the Park

2002 Christo

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

We create works of art of joy and beauty that have no purpose whatsoever -- like all true art. It gives us great joy to do this -- and if the public enjoys it, it is a bonus.

We have chosen Central Park for one of our projects because we have lived in SoHo for the past 40 years at the same address, and New York is our town. We wanted to use Central Park because it is in the heart of the city. The 23 miles of walkways we are using go over the entire park from one of the richest streets in the world -- 59th Street -- all the way to Harlem and Spanish Harlem. The diversity of the people living around the park is extraordinary.

There are many parks in the five boroughs of New York City but Central Park is the only one that is totally cut off from anything natural. Riverside Park is by the river, a natural element. Prospect Park is surrounded by lovely houses that have gardens so the trees of the park and the trees of the gardens are mixed together. But Central Park is absolutely cut off from any other natural element. It is a pillow of green encased in concrete.

The Gates Project was started in 1979. It took 24 years to get the permit. Thanks to Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Patty Harris, the deputy mayor, we now have the permit. Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe and park administrator Douglas Blonsky also have been unbelievably helpful.

One hundred fifty years ago when Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted started designing Central Park they surrounded it with a stone wall but they left openings to allow the public to enter the park. There are no gates, but Mr. Vaux and Mr. Olmsted called the interruptions in the stone wall gates and gave them names: Boys’ Gate, Girls’ Gate, Engineers’ Gate, Warriors’ Gate, etc. So the word “gate” comes from Mr. Vaux and Mr. Olmsted.

In our Gates Project, we are going to place 7,516 gates along walkways in the park. The gates are made of vinyl poles 16 feet tall and 5 inches by 5 inches square. The fabric panels, made of a nylon called ripstop, will hang from the horizontal top bar. The project will be ready the second half of February 2005 and will remain in place for 16 days.

This is absolutely a project for Central Park. The geometric pattern of the city blocks -- hundreds of them, all very rectangular -- surrounding Central Park are in harmony with the geometry of our gates. Our gates are perfectly rectangular, a reminder of the geometry of the blocks all around Central Park.

We are using only the walkways for the gates. Mr. Vaux and Mr. Olmsted designed the walkways in a serpentine, noodle-like shape. The fabric panels moving capriciously in the wind will create many round, voluptuous serpentine shapes, a reminder of the design of the walkways.

This project will be in February, the only month of the year in which we can count on there being no leaves on the trees and so from far away you will be able to see the saffron colored fabric.

We are paying for the project ourselves as we have done for all our previous projects. We never accept sponsors.

To prepare the gates, we have rented an assembly plant in Maspeth, Queens. That is where 5,290 tons of steel, 65.11 miles of vinyl poles and 165,352 bolts and self-locking nuts will be delivered along with 15,032 steel leveling plates so we know the gates will remain vertical. One million ninety-two thousand square feet of fabric will be sewn into 7,516 panels, which means 54.11 miles of hems.

Each one of our gates is already numbered and positioned on our engineering map. We did that last June.

On January 3, 2005, we will enter Central Park. Steel weights that will support the gates will be placed on the hard surface of the walkways. We will not dig any holes. Professional workers with forklifts will distribute the steel bases. Each base weighs 700 pounds, and for each gate you need two -- 1,400 pounds. The workers have to deliver them to the exact position according to our engineering drawings.

Then we have a large number of unskilled workers, usually many students who come either on their own or as a class project. Everybody is paid. We have no volunteers.

They will secure to the steel base the assembly made of the two vertical poles and the upper horizontal pole. The fabric panel will be attached to the upper horizontal pole but you will not see it because it is restrained in a cocoon.

Those workers -- probably 700 of them, we don’t know yet -- will elevate the gate, bolt it to the bottom weight and leave the fabric restrained in the cocoon. Each team of seven or eight people will be raising between 70 and 100 gates. By Friday, all the gates should be standing secured, but you still will not see any fabric.

Then on Saturday morning the teams will open all the cocoons. The fabric will be freed. We hope that in one long morning the entire park will have the gates completed.

Then these people will remain as monitors to assist the public and answer their questions. They will distribute hundreds of thousands of fabric samples for free as we do at every project because the public enjoys having a little souvenir.

Then, after 16 days, the monitors will do the reverse work. They will take down the gates, remove them from Central Park and by March 15 everything should be gone and the materials will be recycled.

Christo & Jeanne-Claude are artists who have worked together for more than 40 years. They are best known for their large-scale projects, including “The Running Fence,” a curtain/fence of fabric stretching more than 24 and a half miles from the inland town of Cotati, California to the Pacific Ocean; “Surrounded Islands” in which 11 islands in Florida's Biscayne Bay were surrounded with 6.5 million square feet of pink polypropylene fabric; and the “wrapping” of the Pont Neuf in Paris and the Reichstag in Berlin.

Birth of the Park

Late 19th century, photographer unknown.

From "Central Park in Blue" at the Museum of the City of New York, one of several current exhibition about the Park.

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

Manhattan real estate is rather precious, so this was a momentous decision that took a great deal of political will. It required a general consensus among the population and the politicians that there had to be a park.

The need for a great central park in New York City goes back to the beginning of the 19th century and the creation of the grid plan in Manhattan. In 1807, the city was on the cusp of growth. Astute city builders knew that Manhattan's location, the quality of it port, the proximity of the Hudson River, and the idea that there would be an Erie Canal, would make this the city of commerce in America and that growth would be extraordinarily rapid.

The challenge was how to plan for it, and the planners came up with a very practical and logical scheme: 12 broad, north-south avenues and 155 narrow, east-west streets from Houston to 155th Street. This plan was imposed upon a very irregular, rocky, somewhat hilly landscape but had nothing to do with any of the natural topographical features. The only open of any size was between 23rd and 34th streets. Called "The Parade," it was a place for the local militias to exercise. By 1830 this park was gone, and because of great pressures of real estate development, all public land had disappeared.

Even the most stalwart builder knew that the city was going to require some sort of a park for peace and safety. People were beginning to think there had to be some reaction to the total control of Manhattan by the grid-planning of 1811. Andrew Jackson Downing, the editor of a very important magazine called The Horticulturalist, who had the ear of lots of Americans, started editorializing that New York needed a park of at least 500 acres. William Cullen Bryant, a leading poet and journalist, also editorialized about the need for major park.

By the 1851 mayoral elections, both the Democrats and the Republicans campaigned for a public park. The question was where, how and what is it going to look like.

Two locations were considered. One was Jones' Wood, a plot of land on the East River that was about 150 acres and pleasantly landscaped. You could easily put up a sign that said "New York Park," let the people in, and you would have been done. But it was not central, it only would have served a certain area, and it was not big enough. People like Andrew Jackson Downing said, "This is inadequate; it will not do."

The other choice was the site that we know today. It was already the site of the first great public works project in New York City, which was the Croton Water System. In the mid-1830s, the city found that if it did not come up with a municipal water supply that was adequate and sanitary, the city could not grow.

So a huge public works project was completed in 1842. Water from the Croton River in Westchester County was brought 42 miles across the East River into the Receiving Reservoir between 6th and 7th avenues, between 79th and 86th streets. From there it went down to 42nd Street and 5th Avenue to the Distributing Reservoir on the site of what is now the New York Public Library. By 1853, the managers of the Croton System began to survey for a huge North Reservoir, which still exists today north of 86th street.

There was a compelling logic that if you were going to take land from the private market for a park it should be tied in with the two reservoirs so the land between them would not be wasted. This was the anchor upon which the park was based. The receiving reservoir, which was filled in in the 1930s, is now the Great Lawn -- the park’s geographical center.

In 1853, everyone had agreed that the land around the reservoirs would be the place for the park. It would be about 848 acres, big enough to suit the requirements of landscape architects.

But it was a very unprepossessing piece of real estate. No one would have chosen it for its beauty or charm. It was rough, rocky and swampy, and it required a vast amount of work to make it into what it is today.

A board of commissioners for the park was established and hired a very accomplished engineer named Egbert Viele. He surveyed the area of the new park and did a pen-and ink drawing in 1855 of a design for a drainage system.

Meanwhile, in 1852, A.J. Downing had died saving victims of a tragic accident that occurred when two steamboats got into a race on the Hudson River. Just the year before he had brought back from England a young man named Calvert Vaux, a trained architect. Vaux looked at Viele’s design, which had been accepted, and said, “This is terrible. This is not adequate. Downing would not approve.” He began politicking behind the scenes and persuaded the commissioners to drop the plan and have an open competition.

The competition was announced in 1857, and 33 proposals were submitted in the spring of 1858. Twelve of the 33 were done by people who were already involved with the creation of the park. Few of these proposals have survived.

The proposals had to honor and incorporate 10 requirements. There had to be a playground, a parade ground, a cricket ground, a flower garden and a group of buildings for exhibitions.

How did Calvert Vaux, having started the competition, get into it himself? He realized he did not have the ability to do the whole thing himself. He did not know the topography well enough. And he also knew that if he were lucky enough to win, he would not have the ability to execute the plan. So he found Frederick Olmsted, who had lost all his money by investing in a publishing business and then ended up as superintendent of Central Park in 1857. Olmsted was working everyday in the park on horseback and knew everything about it.

Vaux persuaded Olmsted to join him in drafting a proposal for this competition. The two of them worked together every evening through the winter of 1857. Their entry was the last submission, and they won.

Vaux and Olmsted included all the things that the competition required: a parade ground, a playground, a flower garden, a conservatory, a museum area, cross streets, a skating park. But all of this was of no real interest to Vaux and Olmsted. What they saw was an opportunity to transform this piece of raw, rocky, narrow, very unsympathetic nature. They were given the worst possible playing deck of cards, the most unpromising piece of land, and that forced them to think outside the box.

The idea was to separate this piece of nature from the city entirely. Once you enter the park, you do not want the city to be included.

Vaux and Olmsted proposed great open areas, which they saw as beautiful landscapes; they saw it as a great, English, stately home meadow. This required major transformations of nature. Ten million cartloads of earth and rock were moved. Far more than simply creating a park, it was transforming nature into a work of art.

Vaux and Olmsted got the commission and went ahead with it. Theirs was a great partnership because they were complimentary in their talents.Vaux did everything architecturally. He designed all the buildings and the 35 or 36 bridges, most of which survive today and are the great glories of Central Park. The original design had only a half dozen bridges. But shortly after the plan was accepted, commissioner August Belmont said there needed to be bridle paths in the park. That requirement meant 35 or 36 bridges.

The biggest architectural component of the park was the Bethesda Terrace, which survives today and was one of the grandest public buildings in New York. It is virtually invisible unless you see it from the right angle; the point that Vaux was making was that architecture should always be subsidiary to nature in Central Park. And that may be why Vaux has, historically, been second fiddle to Olmsted. Vaux was not as charismatic, but he was crucial to the Central Park’s creation.

Central Park cost about $10.5 million. This was big money at the time -- the land alone cost more than $1.5 million. And in October 1857, times were really tough. How did they win approval for this huge public works projects.

The economic panic was a blessing in disguise because the politicians wanted to employ all these people who were out of work. Olmsted had up to 4,000 people on his payroll in 1859-61. It was not until 1862 and the Civil War draft that the numbers went down. Between 1858 and 1861, virtually the entire park up to 79th street, the most complicated part, was built. It was an extraordinarily rapid achievement using the best materials and no shortcuts.

The park was immensely popular from day one, and its constituency was as varied as the city -- and as varied as it is today.

Morrison H. Heckscher is the Lawrence A. Fleischman chairman of the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is adapted from a lecture he gave in conjunction with the museum’s exhibition, “Central Park: A Sesquicentennial Celebration,” which runs until September 28, 2003.

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

Kane's murder was the first of the homicides whose inherent brutality seemed incalculably worsened by their senselessness -- and their location in the Eden of Central Park. In fact, journalists since the 1930s have used incidents in Central Park as powerful symbols for urban crime in general.

The truth is, though, that, like the city itself, the park has been safe for most of its history -- until the "rogue crime wave," to use historian Eric Monkkonen's words, that engulfed New York between 1958 and 1991 and found Central Park to be a particularly tractable host.

And the first chapter in New York City's much heralded, triumphant campaign against that crime wave began in Central Park in 1980. Years before Rudy Giuliani was elected mayor or Bill Bratton appointed police commissioner, the team of officials overseeing Central Park devised a strategy for making Central Park safe again.

CRIME WAVE

In 1965, Robert Lowell published his poem "Central Park," which displayed the 1960s' odd combination of fear of violent crime and contempt for cops:

"We beg delinquents for our life.

Behind each bush, perhaps a knife;

each landscaped crag, each flowering

shrub,

hides a policeman with a club."

The design elements that helped make the park a refuge from the city -- secluded woodlands, hidden coves, paths that curve and dip from sight, Lowell's flowering shrubs -- also made the park hard to protect or patrol. Central Park's fame and beauty made it a prized site for concerts, protests, marches, rallies and celebrations. But the huge crowds also attracted crime.

These two factors, combined with public and police tolerance of so-called petty crime during the 1960s and 1970s, led to a wave of muggings and vandalism in the park that New Yorkers noticed -- and feared. Faced with public concern, park officials during the Wagner administration mowed down shrubs and removed trees from areas where muggers were thought to lurk.

And more draconian proposals were also put forward. Wagner's parks commissioner, Robert Moses, suggested building a senior center in the wooded Ramble in order to halt both gay sexual encounters and violent assaults on gay men.

The idea of the park as sanctuary faded as crime soared. In the 1960s and 1970s, felonies in the park surely averaged at least 800 to 900 a year; we cannot know for sure because it was so difficult for victims to report crime. The park had almost no functioning call boxes or public phones. Reaching the police precinct house in the park by foot was nearly impossible from many sections, even the adjacent Great Lawn. And those intrepid victims who managed to make it to the precinct house were often discouraged from filing criminal complaints.

WAS CENTRAL PARK EVER THAT DANGEROUS?

Many commentators today note that, for some time, the Central Park precinct has had the lowest crime figures in the city. Last year, for example, Central Park had only one of the city's 584 murders, and only 5 of the city's 2,024 rapes. Indeed, for all of 2002, Central Park (PDF Format) had only 132 major crimes -- a 72 percent decrease from 1993. The city as a whole had 153,682 major crimes in 2002 -- or a 64 percent decrease from 1993.

But comparing Central Park to other precincts isn't really fair. It not only has no resident population, making the calculation of crime rates impossible, it is closed at night, while all other precincts remain open for business, and crime.

Central Park's crime numbers are very low, which is wonderful. But in important ways, the problem never was simply the numbers of major crimes. Instead, Central Park has been plagued by three distinct crime problems.

First, it has always attracted heinous crimes that became highly publicized and discussed because of Central Park's symbolic importance, and its location in the middle of New York City, the nation's media capital. The three national television networks, for example, were headquartered within walking distance of the park. Their broadcasts, as well as Johnny Carson's regular nightly attacks, probably exaggerated the extent of Central Park's crime. But there is also no doubt that crime in the park was a real problem.

Second, public events such as concerts or parades have often resulted in rampages by young men. The low point of the park's early restoration occurred on July 21, 1983 -- exactly 20 years ago -- when, following a poorly organized concert by Diana Ross, hundreds of young men tore through the park and its neighboring blocks, assaulting anyone they encountered. A family that had just flown in from Paris for vacation told the New York Post that they had been assaulted and robbed by a gang of 20 teenagers. When, bleeding and bruised, they asked a cop for help, he told them, "That's life in the big city," and walked away.

Warner LeRoy, the owner of the Tavern on the Green, said that dozens of teenagers climbed onto the restaurant's roof and leapt down to the interior patio, where patrons were eating. They jumped on tables, stabbed diners, and stole purses and bags, before swarming back over the patio walls. Known as "the night Central Park got mugged," July 21 resulted in very few arrests -- or recorded crimes.

The third kind of troubling Central Park crime is the vast area of relatively minor crime, such as purse snatchings and bike thefts (before bikes cost thousands of dollars). A poll in 1983 found that over 65 percent of regular park users had experienced some "encounter" with crime in the park. Less than 5 percent said they had reported the incidents, assuming the cops would just dismiss them anyway. And seven percent of regular users said that they carried a weapon in Central Park.

MAKING CENTRAL PARK SAFE AGAIN

The team that began Central Park's rescue in 1980 included Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis, Central Park administrator Elizabeth Barlow (Rogers) and the captain of the Central Park Precinct, Carl Jonasch. They saw the safety of Central Park users, and of the park’s physical plant, as essential to the park's renaissance. They were practical people. No amount of restoration was going to work if the park was dangerous. Donors would not give millions of dollars to restore park treasures that were just going to be vandalized all over again. Nor would donors be enthusiastic if they and their fellow New Yorkers were afraid to enter the park to see the fruits of their gifts. The park had to be revived as the haven that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux had envisioned in the 19th century.

The team faced many impediments, an ominous one being that the Central Park precinct itself was a sorry mess. Housed in a badly maintained converted stable that reeked of urine on humid days, Central Park cops were often a demoralized, tired lot. Ambitious cops avoided being assigned to Central Park, which offered few chances for career-making arrests. Instead, the precinct attracted many who were eager to pass their final years before retirement peaceably. When they had to patrol, they stuck to their cars. There was not much pressure to get out of the cars since the 911 system, implemented in 1972, had centralized dispatch, removing it from the precinct.

Jonasch set out to change things. He was an athlete and one of the first cops to run in the park. He wanted cops to know the park as users rather than as drivers, a revolutionary idea. And he wanted the cops to get out of their cars and patrol on foot or scooters. He met with serious resistance.

But at the same time, Commissioner Davis started the ranger program, creating a uniformed force that would patrol the park and educate park users, concentrating on the quality-of-life issues that cops deemed beneath them. In 1982, Davis added Park Enforcement Patrol (PEP) officers, who could issue summonses for infractions of park rules. Both the rangers and PEP officers visibly patrolled restored sections of the park, enforcing high and previously unknown standards of behavior, such as no ball-playing on Sheep Meadow.

But the conceptual breakthrough in making Central Park safer was the now-familiar but then brand-new broken-windows theory of policing. Harvard professor James Q. Wilson said that cops underestimated the seriousness of disorder, whether the physical disorder apparent in vandalism, graffiti and neglect or the disorder of people behaving badly. The police had to take small signs of disorder seriously and deal with them. That could mean handling small-time offenders, confronting physical disorder or some combination of both. Police could not dismiss disorder as "petty" because petty had a way of growing serious.

Just after the March 1982 publication of his Atlantic Monthly article propounding this idea, Wilson gave a lecture to New York police brass about implementing his theory of policing. Jonasch argued this new approach would be ideal for Central Park.

Crime was still high in 1982, over 700 robberies and 9 murders, when Captain Jonasch set the new strategy for the park. Even as the park seemed to get safer every year, however, horrible crimes punctured its serenity.

In May 1985, gangs of teenagers attacked participants in a March of Dimes Walkathon. NYPD Captain Ray Vignola called them "jackals on the velt." In July 1986, Officer Steven McDonald was shot, and paralyzed, when he stopped a group of teenagers on the East Drive In April 1989, the Central Park Jogger (now known to be Trisha Meili) was beaten, raped and left for dead. On the same night, dozens of youths rampaged through the park, assaulting and robbing park users.

Since then Central Park has reflected the overall drop in crime in the city, although crime has not disappeared entirely. The park was, for example, the scene of attacks on women following the Puerto Rican day parade in June 2000. The lessons from Central Park are pretty clear. It is now probably the safest and the most beautifully restored of the world's great parks. But only constant vigilance will keep it that way.

Julia Vitullo-Martin, who writes Gotham Gazette’s topic page on crime, is a long-time editor and writer on urban affairs, and the co-author of a study on Central Park security conducted for the Central Park Conservancy in the early 1980's.

Dancing in the Park

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

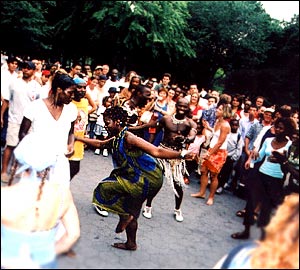

I usually enter through a gateway of benches at West 110th Street and roll on my inline skates past picnickers, tennis courts, the castle and the Boathouse Café. Every year, I promise myself a detour for a pick-up game of volleyball in the worn grass across from the reservoir. But instead, every weekend, my destination is always the same -- the African Drum and Dance Circle near the Band shell.

I was intimidated when I first encountered the African drummers in Central Park six years ago. The music and faces were different. They were from Senegal, Mali and Ghana. The circle made me wonder if I was out of touch with who and what I was as an African-American. The beat touched a primal nerve, reverberating in the torso, echoing in the ears, and I couldn’t help dancing on my skates to the drums. I did not know how the drummers would react, or what I would say or do if they said something to me.

Now I feel at home dancing in the drum circle. I have bonded with the African drummers and the other members of the circle, through languages, cultures, incense and comfort zones that intermingle and in some instances collide there.

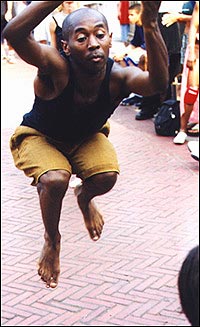

The music beckons passersby from all corners of the park. It is a legal intoxicant that causes foot-tapping, finger-snapping, hip-swaying and losing track of the time. The drum circle lowers inhibitions as people cross ethnic, religious and economic boundaries and dance. There is no need for red tape, velvet ropes or government polices. The circle is its own world. The only rule is to enjoy. Flailing of bodies, heavy breathing, and sweating is encouraged.

There is no special training or equipment needed to dance in the center or off to the side. It is

as simple as taking a deep breath, smiling and stepping back into the enclosed area. The drum circle is a family of brothers and sisters who aren’t keen on parental figures. The aim is unity without a pecking order. There is harmony among the core drummers

and dancers, yet there are periodic challenges from outsiders seeking to strike a sour note.

There is no special training or equipment needed to dance in the center or off to the side. It is

as simple as taking a deep breath, smiling and stepping back into the enclosed area. The drum circle is a family of brothers and sisters who aren’t keen on parental figures. The aim is unity without a pecking order. There is harmony among the core drummers

and dancers, yet there are periodic challenges from outsiders seeking to strike a sour note.

Prior to dancing with the drum circle, I can’t recall a time when I was airborne without being on an airplane or tossed in the air by an older cousin. The drum circle was the first time I was compared to a puppet without its strings, or having coils in my legs instead of bones.

I leave the circle physically exhausted, yet looking forward to the next weekend. Central Park and the circle have kept me happy and alive.

Kendall Williams is a freelance writer, editor and English as a Second Language tutor.

Central Park at 150

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

When New York City decided 150 years ago to build Central Park, it launched a project that became the model for city parks throughout the country. A major undertaking for the city, as Morrison Heckscher of the Metropolitan Museum of Art points out (“Birth of the Park”), Central Park was both a masterpiece of landscape art and a social experiment, a place where people from all walks of life could come together to enjoy a respite from the strains of urban life. After the park opened in the winter of 1858, every city in the country wanted its own version, and the American parks movement was born.

Today Central Park is cherished by the many New Yorkers who come to the park to escape from the rest of the city ("An Escape from Reality" By Sarah P. Lustbader), to appreciate nature, to form new communities (“Dancing in the Park” by Kendall Williams) or to make art (“Our Project For The Park,” by Christo and Jeanne-Claude). And Central Park remains a national model. The park’s rebirth over the last two decades, accompanied by a dramatic drop in crime within its boundaries ("Taking Back the Park from Crime" by Julia Vitullo-Martin) has shown other cities how they can restore their public landscapes. The Central Park Conservancy, begun by Betsy Barlow Rogers in 1980, pioneered the concept of a non-profit community organization raising funds and working with government to fix up and maintain a public park. Parks throughout the city and country -- even the national parks -- have adopted this idea of public-private partnership.

The very success of the Central Park model, however, raises some concerns. The reliance on private funding could weaken the government's traditional role in maintaining public space and ultimately reduce the opportunity for all citizens to enjoy it. Although Central Park has remained the quintessential public space, in Bryant Park, for example, private events held in the park temporarily keep much of the public out.

The reliance on private funding could leave the city with a two-tier park system. Individuals and corporations are most likely to donate to a park they care about, favoring parks in affluent areas. Despite efforts to provide private funds for the rest of the system, such as the non-profit City Parks Foundation, parks in poor neighborhoods, particularly outside Manhattan, could be left to depend on dwindling public dollars.

The activism of the Central Park Conservancy has fostered beautifully maintained grounds and funded many public performances and educational programs, "setting a standard to be achieved for the entire city park system," said Christian DiPalermo, director of New Yorkers for Parks. This has raised New Yorkers' expectations for all of the city’s parks. "You can't have Central Park with a completely different set of policies as the rest of the system," said Ethan Carr, a visiting professor in the Bard Graduate Center's landscape history program. But bringing the condition of all parks up to the level of Central Park would require the city to greatly increase its funding for parks, something it did not do even when the economy was thriving.

It is not only in fund raising that Central Park serves as a model. The conservancy, which operates the park under a contract from the city parks department, is in the forefront of park management as well. The conservancy does not just raise money – it runs the park and hires most park employees. The city parks department has ultimate oversight but does not manage Central Park as it does most other city parks.

The restoration of the park has been guided by a master plan, something urban park expert Peter Harnik says is key to a well-run park. And unlike the parks department in New York and many other cities, the conservancy plans for the long-term upkeep of areas that it has restored, protecting its capital investment and minimizing costs in the long run.

The park has had great success with its innovative "zone management" system, where one gardener is responsible for a specific section of the park. The gardener has the authority to enforce rules – such as prohibitions against trampling newly seeded areas, littering or letting dogs run loose – and is someone to whom visitors can complain or report problems. Doug Blonsky, the administrator of the park, said the zone system “works wonderfully in developing relationships with the community."

Any controversy within Central Park’s boundaries – be it crime, turning a blind eye to wine drinkers in the park while ticketing beer drinkers at the beach, or installing a work of art on its walkways -- immediately gains prominence because this is, though not our biggest, our most beloved and most used park. But a century and a half after it was first created, Central Park continues to inspire. The question is whether the New York City park system as a whole can benefit from its example. Ethan Carr said, "If we are going to call Central Park the great success story of American parks in the last 20 years, we have to find out how that can be extended throughout the New York City park system."

Anne Schwartz is the parks columnist for Gotham Gazette

The Manhattan Waterfront Greenway -- A Thin Green Line

When the Manhattan waterfront greenway opens in just a few weeks Mayor Michael Bloomberg will have achieved what 25 years of planners and policymakers could not: a nearly continuous waterfront esplanade (in pdf format) for walkers, cyclists, joggers, skaters, birdwatchers and many others in the world's most famous borough.

With this esplanade the mayor will have wiped away more than two decades of attention deficit disorder that plagued previous administrations, but the key to harnessing the waterfront to benefit the long-term growth of the city lies well beyond this thin green line. Here’s why:

Popular visions for the waterfront of the future generally swing between two extremes. The first is the sweeping green ring around the water’s edge in places like Little Neck Bay, East River Park, or along the Shore Parkway. The second vision of the waterfront is the “Gold Coast” model, where the remnants of industry are replaced with glistening towers in glass and steel.

Each of these models falls short in certain respects. One, the ribbons of green were in reality little more than decorative trim, a green lace edge alongside the massive investment of waterfront highways and parkways which themselves really cut communities off from the waterfront. The development of Hudson River Park is the most recent version of this thin green edge. The “Gold Coast” model similarly falls short as a community development tool because it generally only accommodates the high-end of the income spectrum. Herein lies the Catch-22 for post-industrial waterfront revitalization: can new life be brought to the waterfront in ways that accommodate all city-dwellers as residents and users, or will this new investment physically and economically exclude most people in favor or higher income brackets?

The city’s rezoning proposal for the waterfront of Greenpoint and Williamsburg will test this limit, and largely determine whether those casually referred to in the popular media as “inner-city” dwellers will in fact be relegated to literally inner city districts laden with asphalt and stricken with highways, or whether the city's emerging vision of a new waterfront will serve poor folks too.

One of the problems with a continuous ribbon of green is that it defies the reality that we are a city of islands. As such, we should be embracing modes of transportation that harness the waterways. In Manhattan, the city is making great efforts to expand ferry transit, with a slew of new or upgraded terminals ring the island from East 90th Street south around the Battery and north to West 38th Street (all connected by the greenway). There are efforts afoot to improve or expand landing facilities further north along the west side even as far north as Dyckman Street. But in addition to the city’s need to create new options for white collar commuters, there is a tremendous need to improve the movement of goods in and through Manhattan, home to two of the three largest central business districts in the city.

When the trend toward containerization carried the port to New Jersey nearly a half century ago, it inevitably took a lot of manufacturing and distribution facilities with it. All of these activities continued the seemingly irreversible trend towards highway and truck transport. Since that time, as traffic has increased exponentially, no new freight connections have been created. Getting a truckload of computers or foodstuffs from New Jersey to Brooklyn relies wholly on the same bridges and tunnels that existed back in the Great Depression more than 70 years ago. And Canal Street sure shows it!

While the Manhattan waterfront greenway celebrates the fact that we are an island, it doesn’t help us address the fact that in the grand scheme of highway-dependent economics Manhattan is nothing more than a congested through route to I-95, the Cross Bronx, or the Long Island Expressway. Yes, pedestrians, cyclists, and birdwatchers vote, but it’s the tens of thousands of trucks passing through Manhattan each day that are literally and figuratively paying the freight. Just as the first layer of asphalt on this new path is being laid, neighborhoods such as Washington Heights and Chinatown are still suffering the effects of noise, vibration, and air pollution of this perpetual truck dependency.

One of the greatest benefits of the greenway plan is that it will connect activity and opportunity that already exist at the water’s edge. Fort Washington, the Battery, Stuyvesant Cove and Harlem River Park will be linked to Riverbank and Hudson River State Park as well as dozens of other attractions. Surely every waterfront neighborhood needs such green destinations at the blue water’s edge, but the city also needs places for less-appreciated activities such as the transport of garbage or generation of energy. The pending sale of the Waterside Generating Station by Con Ed, for instance, has already placed pressure on the Lower East Side by causing the expansion of the East River Generating Station. The development of Hudson River and Riverside South parks on the West Side are only creating added pressure to relocate facilities such as the 59th Street marine transfer station which moves thousands of tons of recyclable paper every day. These facilities shouldn’t be closed, they should just be engineered to perform better. In reality, Lower Manhattan probably needs a state of the art marine transfer station far more than it needs more luxury housing.

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Manhattan waterfront greenway will not be the greenway itself, but the chain reaction of land-use pressures that heat up on the waterfronts of the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn. Now that Mayor Bloomberg has vanquished twenty five years of inaction for Manhattan, let’s hope he puts forth ambitious and positive plans for waterfronts of the opposite shores that have been abused or ignored for even longer.

Carter Craft, an urban planner, is program director of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.

Van Cortlandt Park And The Filtration Plant

In a close early-morning vote just before the end of the legislative session, New York State lawmakers approved the use of a section of Van Cortlandt Park for a controversial water filtration plant. In doing so, they broke a long tradition of going against the wishes of the legislator representing an area -- in this case, Assemblymember Jeffrey Dinowitz -- in turning parkland over for a non-park use. If Governor George Pataki signs the bill, it will put in motion a deal worked out between the Bloomberg administration and Bronx politicians to build the $1 to 2 billion facility underneath the park's Mosholu Golf Course in exchange for $243 million of park improvements in the Bronx.

The bill the legislature passed will not permit construction of the plant until the city completes a supplemental environmental impact statement on siting and running the facility in the park, which is like closing the barn door after the horses have escaped. The review is highly unlikely to conclude that two possible alternative sites would be preferable, although it may lead to better mitigation at the Van Cortlandt site. It would not consider a fourth site Assemblymember Dinowitz recently proposed, under the Major Deegan Highway in his district.

The law also requires the city to issue a Memorandum of Understanding, ratified by the City Council, identifying how much money will be dedicated by the city to "acquire and/or improve" Bronx parks and providing a list of eligible projects.

The city is under a court order to filter the part of its water supply coming from the Croton Reservoir to assure the safety of the drinking water. The city's first attempt to build a filtration plant partly underground in the park, proposed during the Giuliani administration, was derailed when the State Court of Appeals ruled that removing parkland from the public, even temporarily, amounted to a taking of parkland that required state legislative approval.

Under the revised plan by the Department of Environmental Protection, the filtration plant would be smaller and completely underground. As in the original plan, the golf course driving range would close during construction and be rebuilt on top of the plant, although plant opponents question whether this would be possible given the security concerns that have arisen since 9/ll. The golf course would continue to operate during construction, but would displace the open space used by the nearby community.

Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe said that the plan would provide "the greatest renaissance in Bronx parks since the WPA in the 1930s." He said that the parks department has a long list of projects that could be funded, including ballfields, playgrounds, and greenways, and will be seeking ideas from Bronx communities.

Organized labor has vigorously supported the siting of the facility in the park, although only about 5 to 15 percent of the various union members live in the Bronx and the legislation does not mandate that construction jobs go to city residents.

People who live in the neighborhood near the site, a low-income, ethnically mixed community, are still vehemently opposed to the plan because of the traffic, noise, and pollution that would be generated during construction and the years-long loss of parkland and of a popular after-school golf program. They are also concerned about additional truck traffic and the transport of chemicals to the plant when it is in operation. The communities near the park have had greatly increasing asthma rates in recent years.

Park advocates are concerned about the precedent of taking parkland for an industrial facility, and say that the enviromental "review" as well as a city land use review - should have been conducted first to determine whether the park is truly the best site, and not just the easiest and least expensive one. "Parks are always the cheapest sites if you think of them as free land," said Elizabeth Cooke Levy, president of the non-profit Friends of Van Cortlandt Park.

The advocates are also leery because the city has not yet released detailed plans for the facility and has made no written guarantees about the amount of money promised for Bronx parks and what projects would be included. Cooke said that she thought the parks department is "naive in believing they're going to control how the $200 million is spent."

Groups concerned about development in the Croton watershed question the necessity of building the plant at all, saying that the city should focus on watershed protection or look at newer technologies. They predict that filtering the Croton water would undermine efforts to protect the water at its source. Three major environmental groups had independent experts review the Department of Environmental Protection studies, and concluded that both filtration and watershed were necessary to safeguard the city's water supply.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.