Tracking Crime in the Parks

Photo (cc) Josh Jackson

For many years, New Yorkers were afraid to go into the parks. Instead of seeing them as an escape from urban stress -- a place to exercise, read a book, enjoy a picnic -- people viewed the run-down parks as even more dangerous than the streets. Over the past decade and a half, though, the parks have become much safer. Crime rates have dropped citywide, and one park after another has been restored. The city has increased maintenance staff and, since 2005, doubled the number of Park Enforcement Patrol officers, who enforce park rules and deter vandalism and crime.

But crime is still a problem, and until recently, the city had no hard data about how many crimes occurred in the parks. In the absence of that kind of solid information, when a terrible crime in a park is splashed across the headlines, like the 2004 murder of drama student Sarah Fox in Inwood Hill Park, it casts a shadow of fear over all the parks.

The New York City Police Department's Compstat computerized crime-tracking program, which analyzes patterns of crime by precinct and uses that information to address problem areas, has been credited with dramatically reducing crime in the city. But Compstat doesn't track crimes in parks separately (except in Central Park, which has its own precinct).

With the passage of Local Law 114 in 2005, the city began gathering data on crime in the parks for the first time. The law, which was introduced by Councilmembers Peter Vallone Jr. and Joseph Addabbo Jr., requires the police to report felonies that take place in parks and make the information available to the City Council. The program was supposed to be phased in over three years, beginning with a pilot project in 20 parks. The first data from the project have just been released in "Tracking Crime in New York City Parks," a report from the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks.

An Incomplete Picture

For each of the 20 parks, "Tracking Crime" provides the number of felony complaints, in seven different categories, from April 2006 to September 2007. The data examined by the report comes from the four largest (though not necessarily most heavily used) parks in each borough. For comparison's sake, it also includes crime numbers for Central Park, which has been monitoring crime for years.

There was a small increase in crimes in these parks over this time period, but as the report notes, the pilot project covered too few parks, over too short a time period, to allow accurate generalizations about trends citywide. It is also difficult to compare crime rates across parks because the parks department does not collect information on how many people use most of its parks.

Of the 20 parks in the report, Flushing Meadows Park, with 99 felonies, had the highest number of reported crimes. To put that in perspective, however, the report notes that a third of the crimes in 2006 and nearly half in 2007 occurred not on parkland but at the two sports venues within the park, Shea Stadium and the National Tennis Center.

Central Park, with 25 million visitors, had 103 major crimes in 2006, but its crime rate was lower than that of Prospect Park, which had about half as many felonies reported (57) but a third as many visitors. Two parks, both in Staten Island, had no reported crimes, but one, Fresh Kills Park, is not developed yet.

The tracking data also turned up a significant drop in crime in the colder months, when park usage is lower.

One finding that merits further scrutiny is that some parks had much higher percentages of violent crime than others. Parks where more than 70 percent of the crimes were violent (mostly robbery and felony assault, with a very few rapes and murders) included Prospect Park, Fort Washington Park, Inwood Hill Park, Forest Park and Riverside Park. On the other hand, only 35 percent of the crimes reported in Central Park were violent.

Making Parks Safer

Under the law, the city was supposed to expand the crime-tracking program to a total of 100 parks after one year, 200 parks after two years, and to all parks over one acre in size after three years. It has fallen behind this timetable, and the police department has not said when it would be able to meet it. New Yorkers for Parks called on the city to expand the program to 100 parks immediately and to all parks by 2010.

At a January hearing before the City Council Public Safety committee, the police department said that it still did not have the technology needed to give information on more than the 20 parks in the pilot project. At present, park crimes are still entered into the system manually. Vallone, who chairs the committee, called the lack of progress "disappointing at the very least." "We are trying to get the police to be a little more realistic and track parks that are most heavily used," he said.

The police department Web site posts crime data by precinct, but so far, information about crimes committed in parks is not available online. In its report, New Yorkers for Parks recommended that the parks department post park crime data on its Web site.

Vallone said that there is still a lack of communication between the police and the public. Referring to the discovery of a body in a pond in Flushing Meadows Park, which was part of a vicious crime wave for which two homeless teenagers were eventually arrested, he said, "It took a long time for police to alert the public" to a pattern in the crimes.

Beyond the need for more data, "Tracking Park Crime" focused on ways to keep the park safe. In particular, it called for the city to budget money for enough uniformed Parks Enforcement Patrol officers. They enforce park rules, such as prohibitions against adults using playgrounds, and issue summonses for health, traffic, sanitation and environmental violations. By keeping an eye on the parks, they also deter serious criminal activity. The report also suggested providing safety tips online and on signs in parks.

In his response (in PDF format), Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe said the department would add information on safety practices to its Web site. Noting the importance of the Parks Enforcement Patrol, or PEP, in preventing crime, he said, "At the height of the season, we have over 800 uniformed staff in the parks, including full-time and seasonal PEP and Rangers, and fixed post enforcement officers. " He said that the parks department works closely with the police and has been reaching out to community organizations in an effort to design safer parks and deter crime.

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Concerns Grow but the Grass Doesn't

In 1999, my son played on his first soccer team, a band of unruly five-year-olds called the Red Strikers who lost every game that spring. But I remember far less about the team than I do about the field they played on at Brooklyn's Parade Grounds. Hard use and neglect had left it as bumpy as a dirt road, with large bald spots that became puddles when it rained. My son invariably came home covered with either mud or dust.

So it seemed a small miracle when, a few years later, many of the Parade Ground's fields became some of the first in the city to be renovated with synthetic turf. The surface, made with green plastic "blades" packed with rubber crumbs made of shredded used tires, was beautifully smooth, cushioned and well-marked. It was durable and dried quickly after a rain, offering a lot more playing time to all the local teams clamoring for fields.

But some things bothered me. My son's cleats and uniform now shed little rubber pellets instead of dirt. Was there anything toxic in the bits of shredded tire that spread all over our apartment? The fields turned out to be brutally hot in summer, and the coaches at soccer camp warned the kids to bring extra water so they could withstand the heat. And then there was the loss of yet another connection to nature for urban children.

These concerns, as well as evidence that synthetic turf contributes to the urban "heat island" effect and stormwater runoff problems, have led elected officials and environmental groups to call for a time-out in the use of synthetic turf.

Today, Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum and three environmental and parks advocacy organizations are releasing a letter to Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe and Health Commissioner Thomas Frieden. It calls on the parks department to stop installing synthetic turf immediately and to a make schedule for replacing existing turf fields, which disintegrate within a decade. The letter also demands that the health department complete a review of the literature on the health effects of synthetic turf before the startof the spring sports season and calls for testing actual turf installed in the parks for contaminants.

On the state level, Assemblymember Steve Englebright has introduced legislation that would put a six-month moratorium on the purchase and installation of synthetic turf statewide until health and environmental agencies conduct a more rigorous study of the crumb rubber.

The Trouble with Grass

Grass athletic fields require frequent mowing, watering, spraying for weeds, and litter clean-ups, and need to be reseeded every five years. At a time when the demand for playing space has exploded, the city's budget for park maintenance and staff remains tight, and the parks department has not been able keep up with the maintenance of many of its more than 600 baseball, football and soccer fields. The advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks' annual report card on the conditions in 200 neighborhood parks consistently has found poor conditions in the city's athletic fields.

Grass fields must be rested on a regular basis and closed when wet. The Central Park Conservancy keeps its baseball diamonds verdant by shutting them all winter and resting them on a rotating basis throughout the rest of the year. This creates an impossible choice between preserving fields and providing enough playing time for the city's growing number of school teams and sports leagues. With childhood obesity increasing at an alarming rate, the need for places where children can run and play has become more important than ever. Groups already fight over the use of fields, as is evident from the furor over a plan that would have given private schools preferential use of new public playing fields on Randall's Island.

The New York City parks department has embraced synthetic turf as a low-maintenance, cost-effective way to meet the city's growing need for playing fields that can stand up to heavy, year-round use. Since 1998, the department has installed synthetic turf on 77 fields (60 of them replacing existing natural fields), and it has contracted to convert 25 asphalt space to turf over the next few years, making New York the largest municipal buyer of synthetic turf in the country.

Although the synthetic turf fields are more expensive to install than natural ones, the parks department says they are cost-effective when their life span and maintenance costs are factored in. A natural field costs an average of $152,739 a year, versus a maximum of $105,000 a year for synthetic turf, according to figures recently provided by department spokesman Philip Abramson. A new grass field with drainage, irrigation, rich soil and a special blend of grass seed costs $690,000, with an expected five-year life span; yearly equipment, staffing and other maintenance comes to $14,739. A synthetic turf field costs $600,000 to $1 million to install but has an expected ten-year life, plus $5,000 in annual maintenance costs.

Critics question these cost assumptions, however. It is not yet clear how long the synthetic turf will last, noted Christian DiPalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, which began noting the condition of synthetic turf fields as a separate feature in its 2006 parks report card. Also, the parks department's numbers do not include disposal costs, which could be higher than expected if it turns out that contaminants in the rubber crumbs require that they be handled as hazardous waste.

The parks department also highlights synthetic turf's positive environmental impact: It doesn't require watering, pesticides, fertilizers or mowing. However, according to New Yorkers for Parks' 2006 report, "The New Turf Wars," the parks department may be overstating these benefits. It notes that although grass needs to be watered to stay healthy, "synthetic turf also performs better when watered." (In any case, few of the city's athletic fields have irrigation systems.) The parks department also makes minimal use of pesticides and herbicides on natural grass, according to the report.

Although the city has said that synthetic turf will be used primarily as a substitute for asphalt, most of the existing synthetic turf fields replaced natural fields. "However, in most cases, when synthetic turf replaces grass, it's because the grass is actually gone, having been worn away from overuse," said Abramson in an e-mail. "Thomas Jefferson Park in East Harlem is an example of a grass field that became a dust bowl, causing such severe asthma concerns in the community that local elected officials asked us to shut it down. Now, with the installation of a synthetic turf field, it is a wonderful asset for the residents in that area."

What's in That Turf, Anyway?

Nearly all of the synthetic turf installed in New York City is made of plastic strands woven into a porous backing and filled in with a thick layer of pulverized rubber for cushioning. Most of the safety concerns focus on the rubber crumbs. A surprisingly large quantity is used: The average soccer field contains enough of the crumbs to make up 27,000 tires.

The parks department maintains that the particles are inert and do not release any chemicals when inhaled or swallowed. The New York City health department, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and the Connecticut Department of Public Health have all "essentially stated that these fields pose an unlikely health risk to the public and that there is no reason to stop installing these fields," Abramson said.

But a recent study conducted by the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, which found that toxic chemicals could vaporize or leach from the crumb rubber, recommended further research on the safety of the materials.

In the study, commissioned by Environment and Human Health, Inc., a Connecticut nonprofit, researchers heated the rubber particles to 131 degrees Fahrenheit, about as hot as they would get in sunlight when the air is 88 degrees. The crumbs released four volatile organic chemicals known to irritate the skin, eyes and lungs. One of the chemicals is a recognized carcinogen suspected to have adverse effects on the endocrine, gastrointestinal, nervous and immune systems. Two dozen other chemicals were detected at lower levels.

When the researchers exposed the granules to water, they released zinc, cadmium and lead, raising the possibility that these potentially harmful metals could migrate from synthetic fields into the soil and groundwater.

Creating 'Hot Spots'

Other concerns focus on the impact of synthetic turf on the urban landscape. Artificial turf offers none of the natural advantages of grass or even dirt - cooling the air, absorbing and filtering rainwater and offering foraging spots for migrating birds.

Unlike grass fields, which cool the surrounding air by reflecting sunlight and evaporating water, artificial fields absorb and reradiate the sun's heat. Synthetic turf fields are some of the hottest places in the city, said Dr. Stuart Gaffin, associate research scientist at the Center for Climate Systems Research at Columbia University, who discovered this from NASA satellite maps when doing research on the urban heat island effect.

Over the last two summers, researchers visited the hot spots identified in the maps and measured just how hot the city's synthetic turf fields can get: as high as 130 to 140 degrees Fahrenheit. Synthetic turf is hotter than asphalt, said Gaffin.

This could have a particularly negative impact on temperatures in communities where a significant amount of natural surface is replaced by synthetic turf. One such example is the area around the new Yankee Stadium. The stadium occupies the site of Macombs Dam Park, a 20-acre rectangle that formerly contained well-worn soccer and baseball fields and a running track and was bordered by hundreds of mature trees. To replace some of that park's facilities, the city will build an artificial turf soccer field and track on top of a parking garage.

Another consideration is the impact of artificial turf on the city's combined sewage overflows. In most of the city's sewer system, storm runoff combines with household sewage. During huge downpours, sewage treatment plants cannot handle the added rainwater, and untreated waste overflows into the harbor and rivers. Grass and dirt soak up rain, but synthetic turf fields, which are designed to drain quickly, very efficiently funnel rainwater into the sewage system.

Replacing natural fields with synthetic turf runs counter to the city's goal of increasing natural areas and permeable surfaces as a way to reduce stormwater runoff. This strategy is part of Mayor Bloomberg's sustainability blueprint, and likely to be included in the stormwater management plan the city is required to adopt by the end of the year.

"If New York is serious about becoming a greener, more livable city by employing reasonable, cost-effective and environmentally sound stormwater management techniques, then the installation of artificial turf fields needs to be significantly curbed, if not halted altogether, " Craig Michaels, an investigator with the environmental group Riverkeeper said in testimony at a December hearing before the City Council Committee on Parks and Recreation.

Another Alternative?

The Trust for Public Land, which has used crumb rubber-based turf at the 18 public school playgrounds it has transformed into community parks, has said it will switch to a different type of turf for future projects, the Daily News reported.

The parks department, however, has not suspended its use of synthetic turf with rubber infill, said Abramson, and opposes the proposed legislation to establish a moratorium on its use. However, he added, "As the technology advances, we are exploring alternative options, including carpet-style turf."

Given the realities of continued heavy demand for sports fields and limited funding for maintenance, synthetic fields seem here to stay. But advocates say the city needs to look more carefully at the full costs and the health and environmental effects, use synthetic turf where it is needed, such as on soccer fields that get the most wear and tear, and develop better maintenance strategies for grass baseball fields. They also call on the city to formally mitigate the installation of synthetic turf by creating new green space nearby.

"We live in a particular urban environment, and climate changes are going to make things worse," said Gaffin. "The last thing we need is to exacerbate it with our own urban planning decisions."

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

The Ferry Point Fiasco

In June 1998, then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani announced the creation of a world-class golf course at Ferry Point Park in the Bronx. For decades, Throggs Neck politicians had envisioned fairways replacing the local eyesore, an overgrown former city garbage dump that had been transferred to the parks department.

"This is ... a wonderful example of the public and private sectors working together," Giuliani said. For little public outlay, the city would get not only a Jack Nicklaus-designed course with striking views of the Whitestone Bridge and the Manhattan skyline, but also a banquet hall and two public parks, one a waterfront esplanade. A partnership led by J. Pierre Gagne, a developer with a longtime dream of building the golf course but no track record in similar projects, would invest $22.47 million and then pay a yearly concession fee of $1.25 million after the course opened in 2001.

But by 2006 -- eight years and numerous missed deadlines later -- Ferry Point Partners had made little progress aside from taking in a million cubic yards of dirt, sand and cement. The site was a bleak expanse of rubble, oddly shaped hills and muddy roads. The project's estimated cost had nearly quadrupled. High levels of methane gas were detected, requiring the city to pay millions of dollars for environmental remediation. People who bought new houses adjacent to the promised golf course saw their investments plummet. At that point, the city finally ended its contract with Ferry Point Partners and began planning the parks itself.

A year later, an audit by City Comptroller William Thompson Jr. charged that, over the years, the parks department had lost millions of dollars by failing to oversee the project properly.

On January 11, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Comptroller Thompson said that the city itself would finance the building of the golf course. As the administration picks up the pieces of this project, however, the environmental and engineering problems of building on a former landfill remained unaddressed.

"Looking back, it was probably overly optimistic to think that a developer with his own equity could build a golf course and golf house and two community parks and recoup his investment," said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe. "The city took a chance on a good deal for the public and it didn't work out. There is no bad guy in this scenario."

A Brownfield By Any Other Name

For decades, suspicions of environmental contamination swirled around the former Ferry Point dump, located on wetlands along the East River. Methane fires frequently broke out in the heat of the summer. Residents complained of foul odors, blowing debris and health problems.

At the time the landfill operated, industries routinely discarded chemical waste in city dumps. Moreover, illegal dumping continued at Ferry Point for years after it was closed in the 1960s. Other city sanitary landfills of the same vintage are listed by the state as hazardous waste sites. Environmental groups have tried to get records from the city of what was dumped at Ferry Point but have not succeeded.

Even ordinary garbage oozes a toxic cocktail, known as leachate, into groundwater and nearby waterways, as rain seeps through batteries, old cans of paint, bug spray, oven cleaner and other household chemicals. Rotting garbage also generates methane and other gases, which can reach combustible levels and, even at low levels, disperse toxic chemicals.

Federal and state laws now require the tracking of hazardous waste from "cradle to grave" and the careful engineering of solid waste landfills to prevent contaminated liquids and gases from leaking out. Once closed, landfills must be sealed with an impermeable barrier and covered with topsoil and vegetation.

Because the Ferry Point landfill stopped operating before these laws were passed, the city has not been legally required to seal it or make it comply with current standards. The rules at the time simply required covering the dump with two feet of soil.

Ordinarily, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation regulates projects involving solid and hazardous waste, including brownfields reclamation. But because the Ferry Point dump was exempt from the law, the parks department was made the lead agency in charge of determining whether there were any environmental problems. Before approving Ferry Point Partners' initial plans, which included adding a thick layer of construction and demolition debris to be sculpted into the contours of the golf course, the parks department required an Environmental Assessment, a quicker, less thorough review than an Environmental Impact Statement.

For the assessment, a consultant hired by the developer tested 15 samples of soil and subsurface taken over 222 acres. Although the tests detected methane gas and various hazardous chemicals, including volatile organic compounds, DDT, lead, arsenic and PCBs, the Department of Environmental Conservation determined that levels were too low to be a health threat, and the parks department gave the project a green light.

In 2000, after the golf course was approved, residents of a housing project across the street from the site, concerned about the project, alerted the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and the New York Public Interest Research Group.The organizations promptly sued to require the city to conduct a full Environmental Impact Statement. They charged that the Environmental Assessment did not look into the history of the dump, test for contamination of the groundwater or the East River, or address the possibility that construction could force methane to migrate to the basements of houses near the park. The suit was ultimately dismissed because the deadline for filing was missed.

Responding to questions about the proper remediation of the landfill recently sent to the Department of Environmental Conservation, citizen participation specialist Thomas Panzone wrote in an e-mail, "Ferry Point does not call for the reclamation of a site. What it does call for is for the planning of a golf course on top of a landfill."

Building on a Dump

In order to landscape the golf course without digging into the old dump, the contractors had to cover it with fill. The most economical option was construction and demolition debris, or C & D. But by taking in the debris, Gagne, through his subcontractor, Laws Construction, essentially would have been operating a construction and demolition landfill, which brought it under state solid waste regulations. This required a special permit and monitoring to make sure the debris was free of junk like pipes and radiators, as well as chemical contaminants.

Starting a process that would continue for the next eight years, construction companies began dumping truckloads of dirt and debris from demolished buildings.

As environmentalists had warned, the debris' weight began squeezing pockets of potentially explosive methane toward residential areas. To address this, the Department of Environmental Conservation required the construction of venting trenches and the monitoring of methane levels. (The agency, did not, however, test for chemicals that tend to migrate with the methane.) One trench runs along the edge of the community park, where children from the housing project still play even though a mountain of fill has swallowed up much of it.

"Had they done the proper EIS, they would have discovered things like this," said Leslie Lowe, who headed the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance when the lawsuit was filed.

The fill also compacted the spongy layers of trash and wetland below, so more of it was needed. A change in the design of the course, from traditional to a links style with rolling hills, also called for more fill. Every time the amount was increased, Gagne had to go back to the Department of Environmental Conservation for a new permit, requiring a lengthy approval process. Over time, the agency tightened its requirements for the quality of the fill.

Three permits were ultimately issued, the last in November 2005, allowing a total of 2.54 million cubic yards of debris. The city allowed Laws Construction to charge tipping fees to contractors who needed to get rid of debris, for a total of $15.13 million so far. In a November 2006 article in the Daily News, Gagne said that Laws kept the fees to cover its expenses, although it is hard to believe it cost that much for a small crew with bulldozers to push debris into little hills.

"The more they dumped, the more they compressed, and they have never been able to contour as they said," Lowe said recently. "Our engineer spotted this from the get-go. He said, 'I don't think they will ever be able to build this golf course.'"

Some local residents wonder if the city ever intended to build a golf course or whether it just needed a place within city limits for the construction industry to dump its demolition debris at lower cost. They also point out that the tipping fees provided an incentive for the developer to take in as much fill as possible. Dismissing these theories as absurd, Benepe said, "The only grassy knolls were on the golf course."

The Cost to the City

The city repaid Ferry Point Partners $7.2 million for building and maintaining venting trenches, installing monitoring wells and other costs of remediation. The analysis by the city comptroller determined that the cost should have been just $1.3 million. The comptroller's audit claimed that the city also improperly repaid capital improvement costs that the developer was required to cover.

Benepe vigorously disputed the findings. "It is completely wrong that the city overpaid for remediation," he said, adding that the audit showed no understanding of environmental obligations: "We generally agree with most of what the comptroller does when he audits us. In this particular case, we believe there has been a fundamental misunderstanding of both the contract and the city's responsibilities regarding environmental regulations."

After reading about the audit, Lowe, along with four other people who had worked on the earlier lawsuits, wrote in an unpublished letter to the New York Times, "In its haste to award the contract, parks couldn't take the time to do the proper testing and analysis. Doing the right thing then would have identified the real cost of the clean-up and protected the community and environment, thereby saving the project from the 'environmental complexities' in which it is now enmeshed."

The comptroller's audit faulted the parks department for forfeiting $3 million in concession fees because of missed deadlines and for allowing the subcontractor, and not the city, to keep the fees for the disposal of construction debris. In addition, the audit noted, the parks department ended the contract "without cause," requiring it to pay Ferry Point Partners an additional $7 million.

"It is simply astounding that after failing to perform any significant work at the site, Ferry Point and its contractors are walking away with millions of dollars," said Thompson.

Benepe said the city decided to reach an agreement with the concessionaire rather than risk protracted litigation. He said, "The most important consideration was to get this project moving."

The Future of Ferry Point

In an effort to do just that, the parks department has already begun to plan the two public parks slated for Ferry Point and has put out a request for proposals to build the golf course, although no cost estimate has been released. In a joint press release with Bloomberg announcing the new golf course plan, Thompson said, "As my office has done over the last several years, we will continue to monitor the progress of any work at the site."

Laws Construction remains at Ferry Point, continuing to accept truckloads of debris. The company is a subcontractor to an independent monitor the city hired to make sure it is in compliance with the Department of Environmental Conservation permit, according to city spokesman Jason Post.

Henry Stern, who served as parks commissioner under Giuliani, said, "Looking at the larger picture -- looking at the hundreds of acres and the golf course -- it's hard to believe that the environment would not be enhanced by replacing a garbage dump with a golf course."

The local community board and elected officials are pushing hard for the completion of the golf course. "My neighborhood feels that a golf course is a win-win," said Councilmember James Vacca. "Has our patience been tested? Yes. But if the end result means we're going to get a better project, I think the wait will be worth it."

Certainly, daunting environmental problems remain.

Driving on the Hutchinson Parkway service road along the edge of the golf course site, Dorothea Poggi, a longtime resident and founder of Friends of Ferry Point Park, pointed out brown liquid oozing from the ground. She said that no agency has tested the liquid seeping out of the ground and sidewalks near the site, as well as the runoff coming from Ferry Point every time it rains. Also, no one has tested the streams that flow underneath the former landfill or checked to see if toxic chemicals are being vented along with the methane.

Asked about the testing of waterways under or near Ferry Point, Panzone of the Department of Environmental Conservation said in an e-mail that the agency "conducts inspections at the site. While inspection observations have been limited to stormwater runoff at the site, we urge members of the public to notify our office if they observe a more serious condition, and we will investigate."

It does not appear that the city plans to take a closer look at the environmental and engineering problems associated with building on the former dump. No further environmental assessment will be conducted, according to Post. Residents also wonder whether the city will require a drainage system to address runoff and prevent erosion, which has been a continuous problem now that the site is many feet higher than the surrounding landscape.

In addition, it is not clear whether there will be coordinated oversight by all of the city and state agencies responsible for solid and hazardous waste disposal and environmental safety. "I'm not so sure the project was mismanaged solely by the parks department," said Christian DiPalermo, executive director of the parks advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks. "Really, the city itself seems to have dropped the ball."

DiPalermo noted that the Sanitation Department has primary responsibility for turning the mammoth Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island into a park. "Sometimes the parks department gets a responsibility that is really outside their expertise -- and their budget," he said. "This seems to be outside of the parks department's realm."

As the city has already learned, it is a complicated job to put tomorrow's golf course on top of yesterday's trash.

Â

Saving Arlington Marsh

In keeping with his goal of making New York City sustainable into the future, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has approved the preservation of the city's last major unprotected wetland complex, Arlington Marsh on the northwest shore of Staten Island. This is a major step forward in protecting a vital harbor ecosystem, but the marsh still faces threats.

In agreeing to make the 70-acre salt marsh a park instead of holding it in reserve for possible future expansion of the nearby container port at Howland Hook, the mayor is following the recommendation of the city Wetlands Transfer Task Force, which was established in 2005 to determine which city-owned wetland properties should be transferred to the parks department. The fate of Arlington Marsh was the major point of contention on the task force.

Arlington Marsh is one of the few pieces left of the once-vast wetlands of northwest Staten Island, one of the three great marshes of New York Harbor, along with Jamaica Bay and the New Jersey Meadowlands. "For the longest time Arlington Marsh has been at the top of most peoples' acquisition and protection lists, including New York Open Space Plan and the Harbor Estuary Plan," said Bill Tai, director of the Natural Resources Group at the parks department and co-chairman of the task force.

The Task Force Recommendations

The decision on Arlington Marsh is part of a broader effort to preserve New York's diminishing wetlands. The Wetlands Transfer Task Force identified 82 properties, including the march, to be transferred to the parks department, for a total of 225 acres. Its report was released in late September.

The task force also determined that an additional 76 small parcels on Staten Island should go to the Department of Environmental Protection for its Bluebelt natural stormwater control program. More than 100 properties throughout the five boroughs were identified as potentially appropriate parkland, but needing further review.

The parks department made it clear that it could take only a limited number of properties - those that it could successfully manage, given its budget constraints. Properties chosen for transfer were typically adjacent to existing parkland or had a potential local stewardship group. The task force called on the city to provide an adequate budget for ongoing maintenance of natural areas and wetlands and for the restoration of degraded wetland sites.

The task force also made a number of recommendations for a comprehensive policy for protecting and managing smaller city-owned and private wetlands that currently are not covered by federal or state regulations. Legislation has been introduced in City Council to require the city to develop such a policy; 2030 PlaNYC also sets forth the goal of developing a more systematic approach to wetlands protection.

Nature's Last Stronghold

The northwest corner of Staten Island, where the Arthur Kill merges into the Kill van Kull, is a site with both heavy industry, past and present, and significant biodiversity. It was once a thriving maritime and manufacturing center, but as industry left in the middle of the 20th century, wetland grasses, shellfish and birds returned and reclaimed the land.

Even amid rotted docks and abandoned industrial sites, Arlington Marsh has a range of healthy wetland habitats, from mudflats to salt marsh to shrubs to the freshwater wetlands of the adjacent 107-acre Mariner's Marsh Park. More than 100 species of birds feed or nest here. The mudflats and salt marshes are nurseries for fish, shellfish and other marine organisms. Plants and animals at the northern end of their range, including a number of rare and endangered species, flourish in the wetlands and uplands.

The marsh provides prime foraging ground for colonies of herons, ibises and egrets that returned to nest in the harbor's wetlands and islands in the 1970s. The Trust for Public Land, the New York City Audubon Societyand other environmental groups have been working for decades to protect the habitat for this significant wading bird population, known as the Harbor Herons.

West of the marsh is the 187-acre New York Container Terminal, operated under lease from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

There are also residential areas, including a subsidized low-income apartment complex, on the eastern side of the marsh. These largely low-income, minority communities seem more like villages than gritty urban neighborhoods like Hunts Point, but they have many of the same environmental justice issues, including toxic contamination and lack of access to parks, recreation and the waterfront. "You can go all the way back east to Snug Harbor before you come to anything that's public. Everything is gated," said Tai. "You can barely see the shoreline."

The Future Of The Marsh

Arlington Marsh presents a wonderful opportunity for environmental education and research, according to Beryl A. Thurman, executive director of the North Shore Waterfront Conservancy, which has been working to get waterfront access along the north shore. But she and other local activists are not celebrating yet. Although the city plans to dedicate most of the properties that make up the marsh as parkland, it still intends to put a sanitation garage on an eight-acre Department of Transportation site right in the middle of Arlington Marsh Peninsula, across the road from Mariner's Marsh Park.

It is generally agreed that the garage needs to be moved from its current location in a residential area, but local environmentalists say that the city needs to find a better alternative than the new park. "It breaks the natural connection between the freshwater and upland side and the salt marsh and coastal waters," said Richard Lynch, a botanist and president of the Sweetbay Magnolia Conservancy, whose mission is to study and conserve wild areas in the Arthur Kill area.

Robert Pirani, co-chair of the Wetlands Transfer Task Force and director of environmental programs at the Regional Plan Association, said, "Locating a sanitation facility in the middle of a park is a choice of convenience, not a choice of rational land-use planning."

The sanitation garage would be three blocks from the apartment buildings and across the street from a site slated for community ballfields. "Would you put something like that across from Silver Lake or Clove Lakes Park?" Thurman asked, mentioning two parks in more affluent areas of the island. "Why don't we build an education center and comfort station for visitors who live nearby or groups that come to Staten Island who want to do research?"

Local environmental groups are also concerned about the proposed expansion of the container terminal onto the Port Ivory peninsula next to Arlington Marsh Cove. The port expansion onto the former site of a huge Proctor and Gamble Ivory Soap factory would destroy 14 acres of regulated wetlands, four of which form the western edge of Arlington Marsh Cove. It would also require extending the bulkhead and channeling the creek that flows through the area, which could affect the tidal flow to other important wetlands.

Jim Devine, the president and CEO of the container terminal, has said that he does not foresee that the terminal would need to expand further into Arlington Marsh Cove, which influenced the city's decision to make the marsh a park, according to the Staten Island Advance.

In the future, protecting wetlands in the area may become more difficult. According to Staten Island 2020, a recent study by the Center for an Urban Future, the maritime sector offers one of Staten Island's best opportunities for economic growth and the creation of well-paying jobs over the next few decades.

" There is a reindustrialization effort going on at the same time that we're trying preserve as much of these large natural features as possible," said Lynch. Future expansion of the port and related industries calls for careful planning so that the economy can grow without losing the irreplaceable wildlife value and ecological services wetlands provide.

Even making Arlington Marsh a city park does not provide it with permanent protection. In recent years, the Bloomberg administration has persuaded the state legislature to alienate parkland for other uses, including a water filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park and a new stadium for the New York Yankees in Macombs Dam Park. Without further protection in place, who can predict what will happen at Arlington Marsh in 20 or 30 years?

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Replacing Parking with Parks

Someone looking for a parking spot on a sunny Saturday last June in Park Slope, Brooklyn, might have been annoyed to that discover two spots in a prime location were blocked by a plywood cutout of a car and filled with lawn chairs where people could stop and hang out. From 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., members of a neighborhood organization called Park Slope Neighbors fed the meters and invited passersby to sit and enjoy the space.

This parking spot squat, a brief re-imagining of what could be done with a couple hundred square feet of public space, elicited a lot of nasty posts on Curbed, the New York City real estate blog. One of the milder comments was, "I would have loved to see these pedestrian pansies blocking a spot I wanted to park my Ram Pickup in. I would just pull up reeaaal close and BLARE the horn."

On the street, however, "once people started coming out and seeing it, they were very excited about what was going on," recalled Geoff Zink, one of the organizers. People were able to "viscerally experience this alternative use for parking space and how it can improve their quality of life," he said. At the nexus of the Slope’s shopping district and across from the local elementary school — where parents with strollers, twenty-somethings and other locals already overflow the outdoor benches provided by the muffin shop on the corner — it was even possible, for a moment, to envision a permanent public space.

Parks for a Day

Zink and his compatriots will set up a more formal version of their "park" on Saturday, September 22, this time as part of National Park(ing) Day (officially September 21), sponsored by the Trust for Public Land and the San Francisco arts collective REBAR. In a dozen American cities, and around the world, metered parking spots will be turned temporarily into public spaces to call attention to the need for urban parks.

"We want to inspire people to think of creative ways to make New York City more livable, starting with our neighborhood," said Julie Raskin, a Columbia University senior who organized a group creating a mini-quad with Astroturf and lawn chairs — complete with Frisbees, books and free cider — to highlight the university’s shortage of outdoor space for studying and socializing.

About two dozen such "parks" are planned in at least four boroughs. The New York City pedestrian and bicycle advocate Transportation Alternatives is coordinating the effort. There will be greenery and benches in several midtown spots courtesy of New Yorkers for Parks and the Trust for Public Land; a scene of the city before the automobile staged by the Lower Eastside Girls Club; and shade, chairs, lemonade, a volunteer bike mechanic and musical entertainment in the West Village from Time's Up! and Green Map.

" We take for granted that a street has so much space for pedestrians, so much space for vehicles, and so much space for parking. It hasn’t always been that way," said Wiley Norvell, communications director for Transportation Alternatives. "Is the best use of the space to park one person’s private vehicle when nobody is in it, or to have children playing or seniors sitting or have a little bit of green space in an otherwise concrete area?"

What seems like another crazy art installation or a novel form of street theater may actually lead to a valuable discussion about the most efficient and productive use of a major piece of the city’s public real estate. About a quarter to a third of most city roadways are dedicated to curbside parking, while in parts of the city, sidewalks are jammed during peak hours. Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s blueprint for the next quarter century focuses on keeping the city sustainable as it adds an expected one million new residents, in part by creating new public plazas in every neighborhood and reducing traffic congestion and pollution. Reconfiguring some curbside space – in the context of a citywide parking policy -- could help meet these goals.

Parking’s Toll

Urban policy makers are looking more closely at how parking availability and pricing affects traffic congestion, pollution and energy use. Anyone who has ever driven in the city knows that even one perfectly placed double-parked car can snarl the traffic for blocks. Several recent studies have found that drivers searching for parking generate a significant percentage of traffic in the city. A survey by Transportation Alternatives conducted on four days in January and February found that 45 percent of the people driving on Seventh Avenue in Park Slope were cruising for a parking spot. In another study, by transportation expert Bruce Schaller, who is now a deputy commissioner at the Department of Transportation, 28 percent of drivers surveyed while waiting at traffic lights in Soho were looking for curbside parking.

Other studies have found that many New Yorkers drive because they want to – not because they have to – and that available and sometimes free parking offers a powerful incentive for them to use their cars instead of mass transit.

Any plan to reallocate parking spots would, of course, have to be part of a comprehensive plan for managing and pricing parking, something the city does not yet have. Other cities, particularly in Europe, have found many ways to provide parking for those who need it while discouraging unnecessary driving. These include charging market prices for metered parking, allowing only neighborhood residents to park on local streets and creating new space-efficient garages that stack cars on moving platforms.

New Uses for Asphalt Spaces

If some of the city’s parking spots were eliminated, that square footage could be used to make sidewalks wider and safer, add bike lanes, create little parks and plazas in areas that lack public space and provide more public seating for seniors and others who would venture out more readily if they knew there was a place to rest. Imagine wider sidewalks on Prince Street, greenery around Penn Station or benches every few blocks on the commercial streets of residential neighborhoods.

The idea of replacing parking spots for other uses might be starting to catch on. In July, for the first time ever, the New York City Department of Transportation removed car parking spots for bicycle parking, adding racks for 30 more bikes at the Bedford Avenue stop on the L train, a very popular bike-and-ride destination. Then, in August, the department turned a small triangular parking lot in Dumbo into a pocket park.

Transportation Alternatives is developing proposals for the city and community groups as part of a more extensive effort to swap parking spots for little parks and other community space. "In order to be compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act, there are limits to what you can put in on sidewalks in terms of amenities, like bus shelters, benches, or trees," said Norvell . "Only through increasing sidewalk space can these amenities be provided. We think this is a tradeoff a lot of New Yorkers would be willing to make."

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Reopening the 19th Century High Bridge

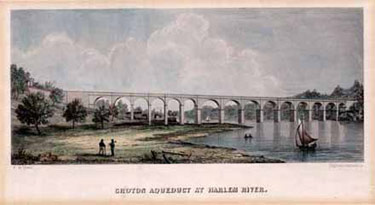

At one time, the High Bridge was known far and wide. Built in 1848 in the style of a Roman aqueduct, it carried water across the Harlem River. It was the most visible symbol of the city’s first water system, an engineering masterpiece that supplied abundant, clean water to a population previously dependent on fouled wells and subject to the twin scourges of disease and fire. Today, however, most New Yorkers have never heard of the High Bridge. Connecting Washington Heights Heights to the Bronx neighborhood of High Bridge, north of Yankee Stadium, it has been closed for decades, a forgotten historical footnote and a missing link between two communities

So it is fitting that the bridge, which helped New York City prosper into the 20th century, should play a role in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s blueprint for making the city sustainable into the 21st. One of the specific environmental and infrastructure goals of PlaNYC 2030 (and one that doesn’t need the approval of the state legislature) is reopening the bridge. The city has allocated $60 million for the project, in addition to an expected $12 million in federal funding. When complete, the reopened High Bridge will be an asset not only for the neighborhoods at both ends of the structure but for the entire city.

The Rise And Fall Of The High Bridge

With its 100-foot-high stone arches crossing from cliff to cliff over the Harlem River Valley, the High Bridge quickly became a popular attraction. The pipes were decked over, and a walkway was added. People flocked to what was then the countryside to spend the day along the river and promenade across the bridge dressed in their finest clothes. A tourist industry sprung up with a ferry landing, beer gardens and inns. Boathouses, marinas and rowing clubs lined the river.

The city eventually expanded up both sides of the Harlem River, but parks were created where the bridge landed. The Manhattan side features the 116-acre Highbridge Park, which has a swimming pool on the site of an old reservoir and a recreation center. In the Bronx, a one-acre park of the same name overlooks the bridge and the wooded hillside across the river. When the water pipes were taken out of service in 1958, then-Parks Commissioner Robert Moses had the bridge itself transferred to the parks department.

The neighborhoods around the bridge declined and sometime around 1970, the city closed the High Bridge because of safety and maintenance concerns. (There is no evidence, however, to support the story that it was closed because kids threw rocks onto the Circle Line.) No one seems to have noted the date that a parks employee padlocked the gates for good.

Keeping The Dream Alive

Practically from the moment the bridge closed, Bronx and Upper Manhattan residents started trying to get back their river crossing. Around the city and within the parks department, too, people worked to promote the idea of reopening the bridge.

Ellen Macnow, coordinator of interagency planning at the parks department, has been one of the bridge’s most persistent advocates. “It happens to be, when you see it, a really fabulous place,” she said. “It reeks of history.” Macnow said that the effort to reopen the bridge first got traction with the 1993 New York City Greenway Plan, a proposed 350-mile network of pedestrian and bicycle trails that included the High Bridge.

Discussions between the parks department and the Department of Environmental Protection, which owns the now defunct water pipes inside the bridge, eventually led to a study by the Department of Transportation to determine the cost of restoring the bridge. Word spread, and more groups became involved. In 2001, the parks and environmental agencies and a number of nonprofit organizations working to improve the parks and trails in the area, including New York Restoration Project, Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct, and the City Parks Foundation formed the High Bridge Coalition.

A key to the effort was getting the residents of the two neighborhoods involved. In 2003, Partnerships for Parks, a joint program of the City Parks Foundation and the parks department, chose the High Bridge area as one of its Catalyst for Neighborhood Parks sites. This effort, focusing on neighborhoods with problematic parks, provides private funding for activities and events that in turn build community involvement in the parks and so help them attract additional public and private resources.

Joseph Sanchez, the Highbridge project coordinator, grew up in Washington Heights and recalls that, even as a child, he saw the potential and beauty in the local parks, “as ugly and dirty as they were.” To get people into the parks, he organized hikes, clean-ups and other activities, and brought in community groups to run sports and education programs. He also spread the word about the High Bridge and urged residents to join the effort to reopen it. “We began to hear stories from residents about how they once used the bridge, how they still want to use it,” said Macnow. Community members joined the coalition and began pushing to get the bridge restored.

In November 2006, the parks department announced that it would take the first steps toward opening the bridge, with a $5 million allocation of federal transportation money from U.S. Representative JosĂ© Serrano and $1.5 million in city funding. But before the project was included in PlaNYC, coalition members thought it would take years to complete the repairs. “We are on our way to reopening the bridge much faster than we had ever thought,” said David Rivel, executive director of the City Parks Foundation. “It really just captured the imagination.”

The restoration will include repairing the bridge’s patterned brick walkway, its remaining stone arches and the steel span that replaced four of the stone arches in 1928 to allow boats to navigate the full width of the river. The bridge will also be safer than it was in its heyday with wheelchair ramps and higher fencing.

A Green Future For The Harlem River

Opening the High Bridge will bring multiple benefits. To begin with, it will make Highbridge Park, with its enormous pool and improved recreation center, more accessible to residents of the High Bridge neighborhood in the Bronx, who have few nearby recreational options. Even now, many Bronx kids climb over the bridge’s locked fences to get to the Manhattan side.

The bridge could also become the focal point of a revival of the Harlem River as a recreational destination, said Drew Becher, executive director of the New York Restoration Project, a private-public partnership founded in 1995 by Bette Midler to reclaim neglected parks in upper Manhattan and the Bronx. “It will make people look down and see what a great Harlem River Valley we have,” he said.

New York Restoration Project has contributed to the resurgence of boating on the river through its Peter Jay Sharp Boathouse, the first new community boathouse in New York City almost a 100 years. The organization recently planted 200 of an eventual 3,000 cherry trees along the river, which, they hope, will rival Washington, D.C.’s cherry blossoms in the spring.

Reopening the bridge also will promote the greenest and healthiest way to get around the city. It will become a vital link in city’s partially completed system of bike and pedestrian trails, including greenways being built on both sides of the Harlem River. It will also fill a gap in the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail, the 41-mile trail following the route of the city’s first water system.

And not least, the High Bridge is a unique recreational space in itself, a place that belongs only to pedestrians and cyclists, with magnificent views of the river and the cityscape. “A stroll on the bridge is just such an incredible thing,” said Joseph Sanchez. “You feel like you’re in the middle of the world.”

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Grading Neighborhood Parks 2007

Conditions in New York’s small, neighborhood parks vary widely across the city. And despite some areas of improvement, overall the parks are in worse shape than last year, according to the recently released 2007 Report Card on Parks, from the advocacy group New Yorkers for Parks.

For five years, the non-profit advocacy group has been evaluating conditions in local parks, from one to 20 acres in size. Trained surveyors assess eight different "service areas" used by park visitors, like conditions of sports field, benches, and bathrooms. They rate each feature following criteria developed from a park user's point of view.

As in previous reports from the group, parks with access to private funding earned the highest grades. Bryant Park, which is maintained by the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, got a near-perfect 99. But the report also found that maintenance levels vary widely among parks relying only on public funds, that maintenance can be inconsistent even in the same park from one year to the next. A number of parks have chronically poor conditions.

In this year's report, the average citywide grade dropped to 70 percent, down from a rating of 80 percent in 2005.

"We don't get consistent maintenance year to year, month to month, or even day to day," said Christian DiPalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks. "And that's because the system has been underfunded.”

Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe, however, called the report card a case of "grade deflation" and said that ratings for many parks were lower than the department's own inspection data indicate. "It flies in the face of reality, which is that parks continue to get better."

PROBLEM AREAS: TREES, DRINKING FOUNTAINS, GRAFFITTI

In addition to rating individual parks, the New Yorkers for Parks report looked at how the different elements fare citywide.

Among the areas that performed poorly this year were the "green" features: lawns, natural areas, and trees. The report recommended a greater investment in horticulture and forestry, areas that have received little funding in recent decades. At present, for example, park trees are pruned only on an emergency basis.

Once again, surveyors also found a litany of problems with drinking fountains, including lack of water pressure, leaks, mold, and basins filled with trash or broken glass. The average grade for all the drinking fountains surveyed was 40 percent.

Careless workmanship - sloppy paint jobs, poorly done repairs, and chipping or peeling paint - gave more than half of playgrounds, courts, fields, and sitting areas an unacceptable score for maintenance work.

The report also noted an upsurge in graffiti, which Commissioner Benepe confirmed. He suspects the increase is tied to a recent court ruling voiding the city's prohibition on selling spray paint to minors. The department has been working with the police and its Parks Enforcement Patrol to reverse the problem.

"Another thing we found is that playground conditions are starting to slip," said DiPalermo.

Ten years ago, the parks department made significant capital improvements to many playgrounds, he said, but wear and tear is starting to show because of insufficient maintenance.

GOOD NEWS: PATHWAYS, BATHROOMS, BUDGET

Parks do get some positive marks. Higher scoring park features included pathways and sitting areas, similar to previous years.

And despite the use of a more rigorous standard this year, the average grade for bathrooms held steady from 2005, a result of the parks department's focus on improving bathrooms through Operation Relief. More than 90 percent of the bathrooms inspected were open, compared with 50 percent four years ago.

Also this year, for the first time, the mayor's proposed budget for parks maintains last year's funding for areas like playground associates, tree pruning, and other maintenance, items that are usually eliminated and then restored during negotiations with the City Council.

As part of Mayor Bloomberg's ambitious greening blueprint, PlaNYC, the city is beginning to commit more funds to care for the city's trees and natural spaces.

Park advocates are lobbying for an additional $10 million for 250 to 300 new playground associates for parks that currently have no staff assigned. They are also asking $5 million more for forestry and $3 million to hire 60 full-time gardeners for specific parks.

THE PARKS DEPARTMENT RESPONDS

The parks department does its own ratings of green spaces through its Parks Inspection Program, which conducts 5,000 formal and 10,000 informal inspections a year.

Parks Commissioner Adriane Benepe said that the program, which allows the department to identify and fix unsafe conditions and other problems, has documented an upward trend in park conditions. Inspection reports can be found by park on the department's web site.

Commissioner Benepe agreed that some of the playground equipment was reaching its natural lifespan, but said that the department's inspection and repair program addresses problems quickly. He noted that a recent budget increase has allowed the department to hire 40 workers specifically to care for playgrounds.

"Contrary to the assertion that there is poor maintenance resulting from a declining workforce, the workforce is growing dramatically," he said. "By the next fiscal year, we will have added 1,000 full-time staff since Mayor Bloomberg took office, a 25 to 30 percent increase."

And although he disputes specifics, Benepe still sees value in the New Yorkers for Parks' annual report card.

"Although we feel we are doing better than the report card would indicate, it's good to have an organization that fights for parks and for better standards," said Commissioner Benepe. "We don't take umbrage at the overall message, which is that parks should be getting better and better."

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Private Partnerships For Public Parks

Randall's Island

Last year, the city parks department and the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation worked out a deal to allow 20 private schools near-exclusive use of the island’s ball fields during after-school hours in exchange for contributing $85.5 million over 30 years to help upgrade and maintain the fields. In a city with a steep divide between rich and poor, the agreement seemed to hit a nerve.

Daily News columnist Juan Gonzalez summed up the outrage felt by many (including public officials representing the area) at the notion of privileged private school students locking up public fields during the hours when many schools run sports programs: “No one has explained why public parks, these natural treasures of our great city, are suddenly being converted into private airlines with first-class and coach sections.”

The deal illustrates the complications that can result from the reliance on private organizations to support what traditionally has been a public, taxpayer-funded service. The issue has been raised in park controversies around the city, from the inclusion of apartment buildings within the planned Brooklyn Bridge Park to City Hall’s refusal to allow protesters to gather on the lawn in Central Park.

"The prospective agreement at Randall’s Island is actually forcing all of us…to address the park dilemma straight on," said Christian DiPalermo, executive director of New Yorkers for Parks, the advocacy group. "Do we think parks are worthy of public investment so that they may provide universal access, or is it time to move to a model that requires some sacrifice in the universality of parkland in return for essential funding?”

A KEY SOURCE OF SUPPORT FOR THE PARKS

Central Park

In the 1970s, after city funding was slashed and the parks fell into disrepair, the Central Park Conservancy pioneered the concept of the private-public partnership to restore the landmark park. Many similar private-public partnerships were started, providing funding, grassroots energy, and innovative ideas to spark a citywide parks revival.

Last week, Bloomberg and the City Council agreed to put more permanent funding into the budget for parks. But the political reality in New York City is that the parks budget is among the first to be cut during times of fiscal crisis. Although the parks budget has held steady in recent years, public funding for operating the parks, once one percent of the city budget, remains just .04 percent. More than 20 large park partnership organizations and dozens of smaller ones help to fill the gap.

The Bloomberg administration has sought to build on and expand this private support. In addition to traditional philanthropy and private partners, it has encouraged corporate donations, concessions, the sale of naming rights, and funding mechanisms that link commercial development with the maintenance of public parks.

Even cities with generous parks budgets have embraced the concept of private groups to support the parks. “No matter how well funded a city’s parks are, they still need some help,” said Andy Wiley-Schwartz, vice president at Project for Public Spaces, a non-profit that works to improve community life through public spaces. “Having community stewards is priceless, and every city knows that, whether they fund parks or not. New York City also happens to need money.”

Private partners can be also more flexible and creative than city agencies that may be set in their ways and bound by union rules. For example, Central Park’s innovative zone management system, in which a gardener has responsibility for a specific section of the park, has proven very effective in keeping high maintenance standards and good community relations. Such groups can also provide a way for people to get more involved in their local park.

THE RANDALL’S DEAL

The Randall’s Island Sports Foundation was founded in 1992 by parents whose children played sports on the island and who wanted to realize the island’s potential as parkland. The group has raised private and public funding to restore and build new recreational facilities, including the $42 million Icahn track and field stadium, and run free summer and weekend programs for thousands of children in the neighboring communities of East Harlem and the South Bronx.

Under the proposed contract with the private schools, the island would get 65 new and restored fields. The schools would cover half of the debt service on the $70 million cost of constructing the new fields and pay for ongoing maintenance, but use the fields less than 15 percent of the total available hours. The Daily News recently reported that city officials plan to spend an extra $53 million on drainage and other infrastructure improvements as well. “The primary beneficiary of the project is the public,” said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe, including the youth and adult sports leagues that play on the island on the weekends and in the summer.

The private schools have been busing students out to the island for years, claiming 95 percent of the fields after school. Their park department permits allow them to continue that use, whether or not the deal goes through. At present, there is not great competition for the fields after school because the island is difficult to get to by public transportation. But the school-age population of the adjacent neighborhoods is increasing, and if access is improved, demand for the fields will increase.

In addition to protesting restricted access to the fields, residents of East Harlem and the South Bronx say the Randall’s Island foundation hasn’t included their communities in planning for the island, has no local representatives on its board, and does not advertise events in their neighborhoods, keeping the island as an enclave for the wealthy.

At a recent City Council hearing on the proposed deal, board members of the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation acknowledged the board did not include representatives from those neighborhoods. But they stressed that the foundation’s goal was to provide a clean, safe place to play for all children. Karen Cohen, the group’s president and founder, said that it is working with 11,000 children from 100 local organizations. She said, “We want to make sure everyone is able to use Randall’s Island.”

OBJECTIONS TO PRIVATE FUNDING

The influence of private funding can extend to how a park is designed, renovated, and used.

A coalition of Brooklyn civic organizations and residents called Brooklyn Bridge Park Defense Fund, which is suing to stop the inclusion of luxury apartment buildings in the Brooklyn Bridge Park to subsidize its upkeep, says the planned towers would make the park into a playground for the residents, not a public park.

|

Washinton Square Park |

The original plan for the waterfront park, developed in a series of community workshops, included stores, a Chelsea Piers-like recreation center, and other uses that would bring people into the park. But when the final plan was released by the Empire State Development Corporation, which is overseeing the construction of the park, it contained luxury apartment buildings, a hotel, and office and retail space. The corporation said that when the actual economic analyses were done, the other commercial uses proved insufficient to generate enough revenue to support the park.

“The fear of privatization in any park is a reasonable fear,” said Marianna Koval, executive director of the Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy, which works to support the park. “It is important to strike the right balance. The housing will work to sustain 74 acres in perpetuity. That’s a great thing. Now, how do we protect against privatization from that housing, and across the board in this park?” Her organization is focusing on programming free activities and events in the park that establish “early patterns of use so that people feel welcome.”

A more subtle form of privatization can result when the financial investment by a private group or donor gives them a proprietary interest in a park. â€The city cedes authority, control, and responsibility to a new class of owner, who has rights and privileges because they are the ones who have to pay off the costs,” said Jonathan Greenberg, founder and coordinator of the Open Washington Square Park Coalition, which is fighting the park department’s redesign of Washington Square Park.

During the Republican National Convention in 2004, the city denied protesters’ request for a permit to rally in Central Park because it said the crowd would damage the carefully restored lawns. Protest organizers charged that the Central Park Conservancy’s interest in protecting the lawns it had paid to restore trumped the more basic right of public assembly.

Greenwich Village residents who are fighting the park department’s design for renovating Washington Square Park see the influence of New York University’s dollars in the redesign calling for a centered fountain and a fenced-in greensward instead of a more modest renovation of the vibrant but somewhat unruly existing space.

Parks Commissioner Benepe rejects that notion, however. “The issue that private dollars are driving the discussion in projects is somewhat of a red herring. It’s a substitute for the fact that some people just don’t like the decisions that are being made,” he said. “There are literally hundreds of projects at some stage of construction, design, and bidding. Unlike with most municipal projects, everybody has an opinion on it.”

FOLLOWING THE MONEY

Brooklyn Bridge Park (Illustration)

A reliance on private funding, observers say, lets the availability of money, instead of a more systematic assessment of park needs citywide, dictate which park projects will go forward. That can lead to prioritizing projects for affluent areas before meeting the needs of neighborhoods that don’t have private resources at their disposal.

There has been a lot of coverage in the press recently about a new playground near the South Street Seaport where children would use sand, water, and movable blocks to build giant constructions guided by adult “play workers.” Architect David Rockwell is designing this labor-intensive experiment at no charge and raising $2 million to pay for the staff. Meanwhile, the once ubiquitous “parkie” who kept playgrounds clean, unlocked the bathrooms, and kept an eye on children has gone the way of, if not the dinosaur, perhaps the panda. In 2005, the city funded 110 playground associates for the entire city during the summer months, two per City Council district.

The operations of the city’s private-public partnerships can also lack transparency and public accountability, advocates say. Even the extent of private support is not fully known, according to the Independent Budget Office. Between $60 and $70 million a year is provided to parks by partnership organizations, but that represents just part of the total. The budget office did an analysis of private funds spent on public parks at the request of the chair of the City Council parks committee, Helen Foster, but found that it could not give a full accounting because the necessary information was incomplete, out of date, or not publicly available.

In a letter to Councilmember Foster, budget office Director Ronnie Lowenstein wrote, “Since the city continues to rely on private funding for support of its parks and recreation programs, a more through annual accounting of private support would be beneficial in helping the City Council and others determine whether the total resources available for parks and recreation are sufficient and appropriately allocated.”

After the outcry on the Randall’s Island contract, city officials agreed to postpone the final vote by the city's Franchise and Concessions Review Committee and hold further discussions with all of the interested parties. Borough President Scott Stringer, Comptroller William Thompson, East Harlem Councilmember Melissa Mark Viverito and the local community boards have been negotiating to reach a compromise that would allow public school children and local residents to have greater access to the fields during after-school hours. The City Council's parks committee has scheduled another hearing on the issue for January 31. A vote by the franchise committee has been set for February 14.

However the Randall’s Island issue is resolved, the growing importance of private partners to the park system requires a closer look at the trade-offs involved.

“It’s the public sector’s responsibility to provide a framework, to define what it means to be a private partner providing a public service,” said Maura Lout, director of operations at New Yorkers for Parks. “We have to figure out a way to make this work, because we’re obviously going to see more and more of it.”

Editor’s Note: Rich Davis, chairman of the board of directors of Citizens Union Foundation(publisher of Gotham Gazette), is also chairman of the board of trustees of the Randall’s Island Sports Foundation.Dick Dadey, the executive director of Citizens Union Foundation, serves on the board of directors of the Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy.

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

Anne Schwartz, in charge of the parks topic page since its inception in 1999, is a journalist who specializes in environmental issues.Â

A Greener Governor?