Taxi Smartphone Apps Seen As Threat to Street Hails

NEW YORK — Smartphone apps that allow passengers to hail yellow taxis could divide the city into those who can afford to pay a premium to get a ride and those who cannot, elected officials argue.

A number of companies are looking to break into the yellow cab industry with smartphone apps that would let New Yorkers hail a taxi without having to wave one down on the street. But yellow cabs are banned from making prearranged pickups, raising questions about the legality of hailing apps. Drivers of yellow cabs also aren't supposed to use electronic devices while in transit.

At an oversight hearing yesterday, members of the City Council also questioned whether smartphone apps were necessary or even fair.

"We cannot have a two-tiered taxi system in this city, where people with money pay a premium to get a cab, and the rest of us are left out," said City Councilman James Vacca, chairman of the transportation committee, during the hearing.

He said the use of smartphone apps to hail taxis could "change the game for passengers on the street" because drivers could refuse service to pedestrians and blame it on an "app call" — especially if it meant a ride that would be more profitable.

"How are we not to think that cab drivers won't respond to those using apps because there will be a higher fare?" he said later in an interview with Gotham Gazette. "If we allow those with apps to be charged more for a cab rider, then how are people who are going to hail going to be treated equally?"

He said that could be a particularly pernicious problem in the outer boroughs, where yellow cabs are rare and residents might be less likely to own smartphones.

"It could pose a have and have-not dilemma, which I would not encourage," he said. "There has to be an assessment of how we prevent that from occurring."

The use of new technology in cabs is one of Vacca's key policy priorities this fall as chairman of the transportation committee, particularly legislation (Intro. 599) to make the credit card payment system in yellow taxis accessible to people with visual impairments. Advocates testified at the oversight hearing in support of the bill.

"I want to make a contribution. You know, my father was blind for the last 30 years of his life," Vacca said.

But it was the question of whether to allow hailing from smartphone apps that some Council members saw as having the potential to upend the way that yellow cabs have traditionally been required to do business — by picking up passengers who flag them from the street.

"There's a reason why we don't allow you to use a telephone to call a cab. That's because we want cabs on the street to be available to be hailed," said Councilman G. Oliver Koppell to Ashwini Chhabra, a deputy commissioner of Taxi & Limousine Commission who was at the hearing representing the agency that regulates the city's more than 13,000 medallion cabs.

Chhabra made the point that he didn't personally see the purpose of smartphone apps for getting a cab. "For me it's just as easy to go outside now and stick my hand out and get one," he said, but added that consumers should have the option if they wanted it.

Koppell said the use of apps could potentially destroy the use of street hails. "I think this whole idea of allowing you to call is frustrating one of the hallmarks of New York, which is just like you said, that most of the time you can hail a cab," he said.

Livery cabs, the black cars that are popular in the outer boroughs where yellow cabs rarely appear, are allowed to respond to calls and have already begun using some types of smartphone software, Chhabra said.

In testifying at the hearing, he said the TLC was keen to revisit the issue of whether to allow "e-hailing" apps and promulgate rules, seeing potential in the software to improve the experience in riding in cabs for passengers and to help drivers increase the number of hails. Rules could be issued as early as October (separately, he said the agency had put out an RFP calling for companies interested in developing payment software for mobile devices.)

The legal limbo for taxi apps hasn’t stopped a number of entrepreneurial companies flush with cash from making plans to enter the New York City market.

One of these companies, Hailo, became operational in the city six months ago after successful launches in London and Dublin. In London alone, the company says it has signed up 30 percent of the city's 23,000 cabbies. And the company has big ambitions for North America, where it also plans to expand in Toronto, Chicago and Boston.

Jay Bregman, CEO and founder of the company, said the idea of Hailo is to “complement” street hails by creating more opportunities for drivers by filling in those hours when they are roaming for passengers. “We are not trying to dominate the driver's day,” he said, adding that, in London, street hails "have not been affected at all."

Hailo's model works by getting cabbies to register as members of its exclusive network, which, in the case of New York, passengers will have to pay an upfront fee to access. Bregman said the fee is collected outside the cost that shows up on the meter.

"What we aim to do is provide services where a proprietary network has access to really great drivers," he said. "That's one of the great compliments people say in London — that hail seems like a better drive than you can usually get."

He said that 3,500 taxi drivers had pre-registered to be part of its network in New York City.

In his testimony at the hearing, Chhabra said that the TLC conducted a survey in the back seat of taxis in recent months and found that almost 70 percent of passengers own a smartphone. He said 50 to 60 percent responded that they wanted to hail taxis with their smartphones. He did not say how many people responded to the survey.

But he said there were other reasons why these services could provide positive improvements for customers.

"They may assist passengers late at night when there are fewer taxis cruising," he said. "They may also serve to reduce driver reluctance to take trips out of Manhattan, if drivers think these apps can provide them with a greater prospect of finding a passenger for the return trip."

The Drama Behind the Bike Share Delay

NEW YORK — The firm picked by the city to run what is meant to be the nation's largest bicycle share program has been dogged by questions about how it got a contract to run a similar system in Chicago, while its partner is being sued by a key software developer.

City officials announced last week that the much-anticipated bike share program would be delayed from its expected roll-out this summer to March 2013. Mayor Michael Bloomberg blamed the system’s software. “The software doesn’t work. Duh,” Bloomberg said on his radio show. “We’re not going to put it out until it does work.”

There may be a good reason why the software doesn’t work: It’s unfinished. According to the city official in charge of the recently launched bike share program in Chattanooga, Tenn., which uses the same platform, the software is undergoing “ongoing development.”

"There's still work to be done — features to be added — and that's where we are at the current time," said Philip Pugliese, of Bike Chattanooga.

Chattanooga's program only involves 30 bike stations and 300 bicycles. In New York, plans originally sold to the public called for 10,000 bikes at several hundred stations.

Pugliese said that while the Chattanooga system is operational and the software is able to complete transactions, there is a delay in the time it takes for transactions to be completed.

"The software probably wasn't robust enough to complete transactions in an operation your size," he said, referring to New York City.

Portland, Ore.-based Alta Bicycle Share, which was awarded the contracts for both Chattanooga and New York City, did not respond to emails and calls requesting comment for this story.

In September 2011, the city awarded the contract for the bicycle share program to Alta, which had worked with its Canadian-based partner, Public Bike Share System Company, to successfully deploy similar systems in Washington, D.C., Boston and elsewhere. Four months later, PBSC ditched the software that provided critical technology for the system and began developing its own.

"To this day, we don't understand, why are you doing this? You can not just remove the heart and the brain," said Isabelle Bettez, president and CEO of Montreal-based 8D Technologies Inc., which developed the original software for the bike share program.

She said that it appeared that Alta Bike Share and PBSC were selling the infrastructure 8D developed to Chicago and New York — and then attempting to install something entirely different as if it didn't matter. She claimed the 8D technology solution comprised over 60 percent of the total bike share system infrastructure — from payment security and wireless solutions to the solar panels that power the kiosks.

"New York would be up and running now without any flaws,” she continued. “We shouldn't even be talking about this now.”

This past April, 8D Technologies filed a $26 million lawsuit against PBSC for ending their relationship and hiring an American firm to develop new software for the systems in Chattanooga, New York and Chicago. PBSC countersued for $2.5 million, saying 8D overbilled for its products. PBSC didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The American firm that PBSC hired, Hopkinton, Mass.-based Personica Inc., also did not return calls or email messages requesting comment.

Alta Bicycle Share was supposed to have had at least 1,000 bikes on New York City’s streets on or before July 31, according to its contract with the city. Unlike most other Alta cities, taxpayers aren't on the hook for the costs of the program, thanks to sponsor Citibank, which ponied up $41 million to get the program rolling.

Still, the much-hyped program has been a topic of discussion, debate and now scrutiny as New York's greenest mayor ever makes bold attempts to turn the city into a bike-friendly utopia.

In an August 17 Wall Street Journal interview, New York Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan suggested that the city was surprised by the problems with the bicycle share software. "We thought that there would be a substantial transfer of the Washington/Boston software capabilities, not a total rewrite, which is why we thought a July launch was feasible," Ms. Sadik-Khan said. "But it turned out it's not just a software upgrade."

In April 2012, the Chicago City Council approved a plan to hire Alta for that city's bike share program. Like New York, the Chicago program has been delayed until next year. But unlike New York, city officials in the Windy City are not attributing the delay to technology.

"Our program didn't really have any software issues or anything like that," said Tom Alexander, a spokesman for Mayor Rahm Emanuel, adding that he didn’t know whether the software that would be used in Chicago was the same as New York City’s.

Instead, he attributed the delay in Chicago to a need for more planning and the advent of winter, when cycling is more difficult. "We just felt like we needed a bit more time to make sure all the infrastructure was in place,” he said.

Bike Chicago, which lost out to Alta for the contract to set up a bike share in the Windy City, called the mayor’s office’s excuse for the delay “spin.”

"Alta/PBSC are clearly over-extended and the $28 million lawsuit from 8D has created a very serious problem for them,” said Bike Chicago’s Josh Squire. "Without the software they have no product to sell, and their contracts should be canceled.”

He said Alta and its partner had lied. “They made it sound like they are upgrading software when, in fact, they are developing new software from scratch.... It could take up to two years to get it right,” he said.

The Chicago inspector general’s office is also looking into allegations of misconduct in the selection of Alta during the procurement process, according to local press reports.

Among the allegations is that the city’s transportation commissioner received a $10,000 consulting fee from Alta to evaluate a bike share system in New York shortly before his appointment by Emanuel last spring.

According to an April 30 report from Crain's Chicago Business-Chicago's bike-share request for proposals was written by Jeremy Pomp, a Chicago Department of Transportation intern who was reportedly a former Alta consultant. Almost immediately after the internship, Pomp was hired by Alta to head the company’s effort in Chattanooga. Calls to Pomp's office in Chattanooga were not returned by press time.

Jonathan Davey, a spokesman for the inspector general’s office, told the Gotham Gazette that by law he was prohibited from commenting on any ongoing investigation, but said the agency had not disputed earlier reports of the investigation into Emanuel's Department of Transportation. "We didn't issue any denial,” he said. “Make of that what you want."

Alta Bicycle Share was founded in 2010 as a partnership of Portland, Ore.-based Alta Planning & Design, which designs bike lanes and parks, and BIXI, the commercial unit of PBSC.

PBSC was set up as a nonprofit in 2007 by the Canadian taxpayer-funded parking authority of Montreal to create a modular bicycle sharing system for the city. PBSC then launched BIXI in 2009 to expand the model into cities such as Washington D.C., and London.

But by 2011, PBSC was in financial trouble, so the City of Montreal provided a $37 million loan and guaranteed $71 million in credit.

The Montreal Gazette reported Aug. 7 that PBSC had projected $91 million in revenue for its 2011 financial report, $83.6 million of that from international sales. New York accounted for the biggest part of PBSC’s sales, although the company didn't see the revenue.

PBSC instead reported $32 million in revenue, $27 million of that from international sales. If the company had delivered its bikes to Chicago and New York this year, it would have made an additional $67 million in revenue.

Canadian press reports show that, in July, the City of Montreal's auditor said that under the city charter, PBSC had no legal right to be in a commercial enterprise through BIXI. The auditor wrote that "basic elements of management were neglected, including risk and cost-benefit analyses and allowance for a financial margin of error.”

Around that same time, The New York Post reported that it had discovered through a Freedom of Information Act request that Alta Bicycle Share had asked Citibank to speed up payments of $3.5 million in case the New York system was delayed until spring and runs out of cash.

In an email message, Andrew Brent, a spokesman for Citibank, said that "even on questions about sponsorship financing, we’ve nothing to say at the moment."

MTA willing to evaluate integrated fares for subways, bike sharing

Workers install a dock to model how the city's bike share program would work, 2011.

NEW YORK – In the near future, subway riders may be able to use their fare cards to check out a bike from hundreds of nearby docking stations.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority said it is open to evaluating ways to integrate fare payment with the city's bike share program as it moves toward a wireless, smart card-based system by 2015, agency spokesman Aaron Donovan said in a recent interview.

The smart card will be based on an open payment system that will allow customers to simply tap and go at a turnstile with their own credit or debit cards.

The city's bike share program -- which promises to put 10,000 bikes that can be checked out on the streets in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens -- is expected to begin rolling out this summer. Officials have said the program will likely begin in early August.

Department of Transportation spokesman Nicholas Mosquera said that in other cities, up to 50 percent of bike share trips are connections to other modes of transit.

But he said while he expects to see the same here, the DOT is currently not working on fare payment integration at this time. "We look forward to exploring it in the future," Mosquera said.

The Paris Region Transit Authority currently issues a tap-and-go fare card called Navigo that makes it possible to pay for the city's VĂ©lib’ bike share system as well as other means of transportation.

"Users can then just show up at any station and take out a bike from a docking station without having to go through any other process: you simply select a bike, swipe your card over the card reader and wait for the green light and signal to release your bike," said Albert Asséra-Directeur, strategy and marketing director for JC Decaux in Paris.

Valeau said the transit authority has allowed JCDecaux’s infrastructure and systems to recognize particular transit cards. Each system is otherwise independent.

The Smart Card Alliance, a non-profit association that works to stimulate the widespread application of smart card technology, said it backs a similar plan for New York City.

Executive Director Randy Vanderhoof said he could foresee a Paris-like situation where the Alta-run bike share accounts could be linked to a card issued by the MTA.

That way, people who use both services would have a common way to check in and check out of both systems, he said.

The widespread use of such technology will also be spurred, in part, by a new initiative backed by the major credit card issuers requiring all U.S. banks to switch over to smart cards by 2015. "Soon, everyone will have a card that they can use in open payments systems like the MTA and the bike share program," Vanderhoof said.

Mosquera said New York City's bike share program is designed to provide sufficient bike share capacity at transit hubs, allowing riders to transfer quickly from bike other modes or vice versa.

He said the bike share stations extend the reach of the transit system, making distant parts of neighborhoods easily accessible from subway stations.

"The system will be perfectly suited to any potential fare integration," Mosquera said.

City set to begin rolling out nation's largest bike share program

Photo courtesy the New York City Department of Transportation

NEW YORK – On a recent Sunday afternoon at the outdoor flea market along the Williamsburg, Brooklyn waterfront two blue bikes splashed with the Citibank logo stood under a tent awaiting riders.

As hundreds of people walked among the flea market vendors, a few peeked in to check out the cycles. One guy said the bikes "ride pretty smooth."

The unisex, 3-speed, bell-and-light-laden upright bikes were being demoed to give New Yorkers a chance to try out the city's big bike share before it gets up and running later this summer.

Once it has been completely rolled out, the program will likely be the largest of its kind in the nation – and New York City will have finally joined other cities in the U.S. and in Europe, where such systems have been around for years.

If the $41 million program makes it in the city, it could potentially transform the way that New Yorkers get around the metropolis with hundreds of thousands of new bike trips being taken each year.

But will the Big Apple's collective psyche shift from the bike being perceived as a tool of recreation and exercise to that of a more utilitarian or alternative form of public transit?

Will it be safe, in a city that is notoriously peevish toward cyclers?

Simply put, will the share program usher in broader acceptance of the bike?

Josh Moskowitz, project director for the Capital Bike Share program at the Washington D.C. Department of Transportation, has no doubt that the answer to that question is an "unequivocal yes."

"We've seen daily bike trips in D.C. grow from 3,600 rides per day in 2011 to 6,800 rides per day so far this year," Moskowitz said, adding that DC commuters often jump on bikes near subway stations to complete their jaunts to work.

A NEW FLEET OF PUBLIC BIKES

New York's 24-hour-a-day program, known as Citi Bike Share, will eventually include 10,000 bikes and 600 bike-docking stations throughout parts of Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens.

The solar-powered, wireless docking stations will be located on sidewalks, curbside road spaces, plazas and other locations suggested through a community-driven process.

Each station can accommodate between 15 and 60 bikes. They are self-contained and require no utility connections. Installation can be completed in minutes.

Oregon-based Alta Bike Share will be running the system and splitting profits with the city.

Annual memberships cost $95. There will also be price options for day and weekly memberships. Members must be at least 16 years old and are entitled to unlimited use of the system for individual bike trips of up to 45 minutes.

It is generally assumed that, like the D.C. program, Citi Bike will likely be used primarily for short trips. The DOT says around 54 percent of all "trips" taken within the city are between two points less than two miles apart.

And although City Comptroller John Liu recently raised concern regarding potential liability issues from bike share accidents, DOT spokesman Nicholas Mosquera said the bike share contract indemnifies the city from claims.

"The city has no additional exposure related to the bike share," he said. "Other bike share cities have not had claims either."

The nonprofit Transportation Alternatives, which advocates for better bicycling, walking and public transit, had been advocating for a bike share program in New York for years.

The group even conducted focus groups before talking to the DOT and city planning officials. Efforts for a large-scale bike share were based in great part on the belief that such a program would lead to a more bike-centric New York City, much like the situation the group had witnessed during a visit to Paris in 2008.

Most of Paris' 273 miles of bike lanes within the 40.7-square-mile city were built after 2001. But, eventually, transportation officials realized that most Parisians simply didn't get what the lanes were for.

"They didn't have a culture for commuter cyclists," said Caroline Samponaro, director of bicycle advocacy at Transportation Alternatives.

Since 2007, when the bike share program was introduced, the City of Paris has seen a 41 percent increase in the number of cyclists on its streets. A recent proposal before the Paris City Council called for expansion of the bike lane network to 435 miles.

Samponaro thinks the city could see a similar reaction.

"Given its geography, the distance of our trips thanks to high density, New York City has the potential to be the biking capital of the world," she said.

She reasoned that when you don't have a bike, and you see all the new bike lanes you may wonder, hey, what does this have to do with me? What's the point of this? But suddenly with the bike share, observers who may not have cycled in the city before will experience eureka moments where they realize that they too can use the bike lanes.

The city is committed to having 1,800 bike lane miles on streets, parks and paths by 2030, according to a 2012 Department of Finance briefing paper. The DOT plans to install 50 lane miles each year until the citywide network is complete. The 2012 DOT fiscal budget includes over $6 million – mostly federal funding – to expand the network.

But Samponaro said one key to full saturation of all those lanes might be the full integration of the bike share with public transit. A key model is the Paris bike share, Velib.

The program has six bike stations around each of the city's 385 metro stops, according to Thomas Valeau, who was in charge of the bicycle project in Paris for JCDecaux, the vendor that runs the program there.

Valeau, who now manages customer relations for 14 similar programs in cities across France, said the Paris system made for a very dense network.

"Many customers use our bikes for going to work, and take a bike in the morning for going to the closest metro, then take the metro and/or finish their trip by bike or walk to their final destination," Valeau said.

BIKE SAFETY

Perhaps the biggest obstacle standing in the way of fully tipping New York's collective psyche towards cycling are the perceptions that is unsafe.

That includes safety for bicyclists, as well as the safety of pedestrians.

Between October and December 2011, 26 pedestrians were injured in crashes with bicyclists; six bicyclists were injured in those incidents, according to DOT data from June obtained by Transportation Alternatives. In the same period of time, 4,336 bicyclists and pedestrians were injured by drivers. That means that, for every 356 injuries caused by car crashes, one pedestrian or bicyclist was injured in a bicycle-pedestrian crash.

But the DOT statistics also show the number of New York cyclists quadrupled over the last decade. During that time, the rate of risk to cyclists was down by 75 percent.

Still, New York bike lanes are pocked with hazards in certain parts of town. As any cyclist will lament after a rush hour trip down a bike path on Broadway between 42nd and 14th streets, the green strips clearly marked for bikes often turn into sidewalks, filled with talking, texting or camera-wielding pedestrians. That, coupled with occasional errant delivery men on bikes heading the wrong way or a car that turns in front of a cyclist, the lanes can be rife with potentially hazardous situations.

In 2010, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer released an informal study called “Respect the Path, Clear the Lane” that found 1,781 bike lane blockages and other infractions during morning and evening rush hours at 11 Manhattan locations.

Observers from Stringer's office charted 741 instances of pedestrians encroaching upon bike lanes, including over 275 occurrences of motor vehicle blockages, among them police cars and school buses. The study also found 242 cyclists riding the wrong way in a bike lane; 237 cyclists riding through red lights; and 42 instances where cyclists rode on the sidewalk on streets with a bike lane.

Stringer's office hasn't collected data on bike lane congestion since the 2010 study, though a spokeswoman said the office knows from recent reports that safety issues related to cycling continue to be a concern for New Yorkers.

At a February 2012 City Council hearing on traffic enforcement, the executive officer of the NYPD Transportation Bureau, Deputy Chief John Cassidy, said the police issued 48,556 summonses to bicyclists in 2011. The Department only issued about half that number, 25,000 tickets to truck drivers.

The NYPD did not respond to repeated requests by phone and email for comment.

"It is a fact in major urban areas that less people opt to ride simply because they do not feel safe," said Ryan Zagata, founder of bike company Brooklyn Cruiser.

But he said education is critical. Zagata also said cyclists have an obligation to obey all traffic laws, as if they were driving a vehicle – and that includes riding with traffic as well as stopping at all stop signs and lights.

Jim Brown, communications director for the California Bicycle Coalition, said with all the new cyclists or cyclist trips each day on city streets, the new bike share program has the potential to eliminate at least some hazards since more bikers on the road ultimately affect traffic speed and pedestrian patterns.

"It's well understood that increased bicycle ridership correlates to a lower incidence of collision between cars and bikes," Brown said.

Still, he said in places like New York that are making fast strides with bike planning, it may still take time for cyclists, drivers and pedestrians to figure out how to share the road effectively.

For its part, the DOT said it continuously works with the NYPD on cyclist safety in general and it did so during the planning of the bike-share program as well.

In one list of rules from the DOT, taxi cabs drivers are told it is illegal to drive, stop or park in a bike lane and punishable with a $115 fine. Drivers are cautioned that "dooring" – opening of doors onto a bike lane – can be fatal. And drivers are expected to yield to cyclists when turning.

As Transportation Alternative's Samponaro noted, the streets haven't been so fundamentally changed in close to 50 years. She said the bike share will show New Yorkers whether or not biking is something that makes good sense to them.

"People are used to doing things a certain way but pedestrian lanes, dedicated bus lanes and safe bike lanes are all essential to keeping the city moving forward, " she said.

Council Tackles City Transportation Issues

Photo by William Alatriste

The City Council approved three bills today to make travel in New York less hazardous for people living with disabilities.

The first bill (Intro 183-A) established an Accessible Pedestrian Signals Program (APS) that will place audible alert systems at pedestrian crossings to let those with impaired vision know when it is safe to cross. The Department of Transportation will be charged with installing these alert systems at the most dangerous pedestrian crossings in the city.

“It’s not easy for a visually impaired person to get around New York City today,” said Councilmember James Vacca, who chairs the Council’s Transportation Committee.

The councilman recalled his blind father listening at street corners for the sound of approaching cars to know when he could cross. Nearly 200,000 New York City residents suffer from visual impairment.

The other bills (Intros 449-A and 745-A) would include the right to a wheel chair accessible car to the livery passenger’s bill of rights and require that the Department of Transportation inform people with disabilities about changes to sidewalks because of construction on its website.

Defying the Mayor

The Council also voted to override the mayor’s veto of two parts of the Fair Parking Legislative Package passed in January. One of the package’s provisions (Intro 490-A) called for traffic enforcement agents to automatically cancel parking tickets issued while the driver was getting a pass from a Muni-Meter.

The mayor contended that the bill would lead to illegally parked drivers trying to cheat their way out of tickets. Council Speaker Christine Quinn said that this would be impossible because those getting a ticket would have to provide a Muni-Meter pass issued no later than five minutes after the ticket.

She added that giving a reprieve to someone ticketed while trying to get a parking pass was simply common sense.

Another of the package’s provisions (Intro 747) prohibited the city’s practice of putting stickers on vehicles in violation of the alternate side parking rules. Mayor Bloomberg said that this practice helps keep New York’s streets clean. But Speaker Quinn said that the mayor’s past Street Cleanliness Scorecards don’t support that claim and added that the hard-to-remove stickers are an unnecessarily harsh punishment.

The mayor is also expected to veto another bill the Council passed today that would require a prevailing wage for maintenance and security employees at certain buildings developed or leased by the city government.

Under the legislation (Intro 18-A) employees at buildings where the city leases a majority of the space and at least 10,000 square feet, and projects that receive at least $1 million in city funding, would be eligible for the prevailing wage. The bill would raise the wages for more than 100 workers by more than 35 percent at qualifying buildings that are not fully unionized.

Speaker Quinn said that the Council was concerned about the possibility of non-unionized workers with lower salaries dragging down the wages of other workers in the building services industry – an industry that provides jobs for the city’s working class people.

“We should be treating workers fairly by paying them a decent wage. Our taxpayer dollars shouldn’t go toward undercutting working families in a race to the bottom,” the speaker said.

The wage increase would come at minimum cost to the city, according to the Council, and would amount to less than one percent of what the city spends on leasing office space.

West Village Redeveloped

The Council also passed the proposed redevelopment plan for the former location of St. Vincent’s hospital in the West Village.

Several residents of the community booed the decision from the upper balcony of the council chambers.

Speaker Quinn said that the redevelopment project would include an intensive care center to replace St. Vinvent’s. But Councilmember Charles Barron said that the facility was not big enough or properly equipped to replace a full service hospital. He called the project a case of the city government capitulating to rich private developers.

“You have a community that now needs to travel too far to get basic medical services. This is a life or death matter,” said Barron, who, along with other council members, was wearing a hoodie in a show of support for the family of Trayvon Martin.

Several members of the Council participated in a remembrance ceremony on the steps of city hall before the council meeting for Martin, an innocent teenager shot in Florida last month by a community patrol officer.

The Council passed a resolution supporting the federal Justice Department’s investigation into Martin’s killing. In addition, the Council also passed two other resolutions urging the state government to pass the Dream Act and the New York Dream Fund Commission for the children of undocumented immigrants.

Selling Discounted Rides on a Metrocard a Fare Practice?

Photo by Keegan Jones

Sometimes it’s the little cases that go to the highest courts and establish new and surprising law. That’s what happened last month in the 2009 case of People v Joseph Hightower in which a New York City unlimited MetroCard was actually put to unlimited use. About ten million weekly swipes in the city’s transit system are on monthly unlimited cards, a card can only be used once in an 18 minute period at the same transit stop.

Hightower, a New Jersey resident, then 28, had purchased the unlimited use card but used it to sell discounted rides to travelers other than himself. He was arrested and by pleading guilty was eventually convicted of the misdemeanor of petit larceny. While the use of the card is transferable, selling rides on the card is prohibited.

An interim appellate court had upheld the conviction. But writing for the Court of Appeals, Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, rejected the prosecution theory of larceny although conduct of the same type had long been treated as larceny. Citing the state Penal Law, Lippman held that no property or money had been taken from the New York City Transit Authority because they had never actually received money from the purchasing passenger. Had Hightower been charged with accepting money for the use of the card that would have been upheld. Although in addition to the larceny he had been charged with unauthorized sale of transportation services and also illegal access to Transit Authority services, he hadn’t been convicted of the charge of the unauthorized electronic swipe of the card.

The definition of larceny requires a taking. When, with intent to deprive another of property or to appropriate the same to himself or to a third person, he wrongfully takes, obtains or withholds such property from an owner thereof.”

While lawyers for the Manhattan District Attorney argued that the defendant deprived the Transit Authority of a portion of its business, Lippman’s Opinion rejected that theory, citing cases in which unpaid taxes could not be considered property stolen from the state. Here, the judge wrote in the unanimous opinion, “defendant was not in possession...of monies owned by the NYCTA.”

Hightower’s case was dismissed and with it his conviction. He had spent a day in jail. Counsel for him was Adrienne Hall of the Legal Aid Society.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court Justice

City Council Acts to Slow Transportation Projects

Photo by New York City Department of Transportation

The transportation department has created pedestrian plazas, like this one on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan, throughout the city. The porgrm has won wide praise, but area residents do not always approve.

The City Council yesterday flashed an orange light at a city Department of Transportation that some members see as ignoring warning signs in its push to make city streets more hospitable to pedestrian and bicyclists.

By unanimous votes, the council approved two measures, sponsored by transportation committee chair James Vacca, on projects that reconfigure city streets One measure looks forward, the other back, but both reflect the feeling among some council members and residents that the transportation department under commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan has become an agency with a mission that forges ahead with its plans for plazas and bike lanes without benefit of consultation or facts.

In Vacca's view, these bills would change that. "The days when the Department of Transportation could unilaterally reconfigure our streetscapes are gone," he said.

The first bill -- Intro 626A -- would require the transportation department to consult with other city agencies, including Small Business Services and the police and fire departments, before it reconfigures streets. It also would have to report to the City Council and relevant community board on the results of those talks.

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Vacca said the measure was prompted in part by complaints from small businesses.

"Many of the bike paths, many of the pedestrian plazas negatively impact small businesses and their ability to survive in the City of New York," Vacca said.

In addition, people with disabilities -- particularly the visually impaired -- have told council members that "pedestrian plazas have not been constructed in a way so that it is safe for them to move through the plaza," Quinn said.

The second measure – Intro 671 -- requires the transportation department to provide statistics on the effects of the street change within 18 months of when the reconfiguration went into effect. This would include data on traffic flows, accidents and emergency vehicle response times. Quinn said was in part a response to complaints from residents of the Borough Park section of Brooklyn that the establishment of a pedestrian plaza there had slowed response time for emergency vehicles.

The administration has come under fire for its use of data to justify its ambitious street changes. When it announced the establishment of a pedestrian mall around Times Square, the said its would improve traffic flow. While the mall has done many things, it has not, by the city's own account, reduced gridlock or increased traffic speeds. The city first tried to keep that data private and then, when it finally was released, sought to dismiss the importance of its numbers.

Putting on the Brake

Yesterday's votes are the latest in a series of attempts by council members to slow down the transportation department's plans. Earlier this month, the council unanimously passed a bill requiring that the department give community boards advance warning of any planned bike lanes in their area and that the department participate in any hearing on the proposal the community board might wish to hold. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has signed the bill.

In February, council members approved a measure, later signed by the mayor, requiring the city to report on pedestrian and bicycle accidents – including those in which a cyclist struck someone on foot -- as well as automobile related accidents. Those backing the bill, including the widow of a 50-year-old man killed when he was hit by a bike said more accurate figures could help the city craft a better policy on bike lanes.

As the administration has stepped up its effort for pedestrian plazas and especially bike lanes – it has added some 250 miles of the lanes in the last four years -- opposition has increased as well.

Along with taking issue with the street enhancement themselves, opponents have criticized the administration for not adequately consulting with people in neighborhoods about where the bike lanes and plazas should go -– or it they should be there at all.

"Bike lanes drop out of the sky without any notice to the community," Council member Lew Fidler, the sponsor of the bill requiring consultation with community boards, said last year.

While supporters of the recent council bills -- including Fidler -- deny they are anti-bike lane, some doubt it. Bicycle advocates said the measures would subject the lanes to a level of scrutiny not seen on many other projects. "No other safe-street improvement seems to get that kind of treatment," Michael Murphy of Transportation Alternatives told Capital.

As the debate has grown increasingly acrimonious, bike and pedestrian advocates say city residents want to slow traffic and make street safer for those who walk or bike. They cite a poll released in October, which found that 58 percent of New Yorkers support the bike lane program.

"Most New Yorkers like bike lanes," Noah Budnick, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, has said. "I don't know anyone who s pro-crash or wants to see more injuries and deaths on our roads. Streets with bike lanes in New York City are 40 percent safer than those without."

Murphy expressed concern to a reporter that bills such as those passed yesterday might slow down the installation of new bike lanes. Of course, some council members might say, that's the idea.

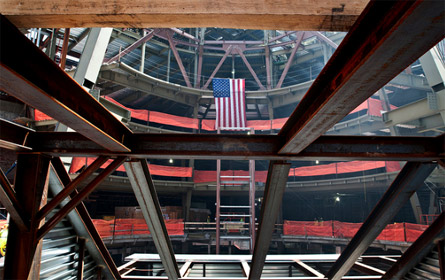

After Delays, Fulton Street Transit Hub Takes Shape

Photo by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority

By this summer there were clear signs of progress at the downtown transit hub, although completion is not expected until 2014.

After years of political wrangling and delays, components of the Fulton Street Transit Center are finally coming together.

Yesterday, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority reopened the southbound platform of the Cortland Street station, which has been closed since 2005. Recently the authority celebrated the openingof a new entrance at 135 Williams St., which offers improved access to the A, C, 2 and 3 platforms. The entrance is decorated with a refurbished mural from a now defunct midtown hotel, and is one of three entrances that will offer similar improvements.

"We have reached yet another significant milestone as we move forward to complete what will become a landmark transportation facility," MTA Chairman and CEO Jay Walder said at the event. "Once complete, this complex will provide our customers with a more seamless experience at this major downtown hub."

The openings come as the above-ground dome begins to take shape, as does the Dey Street Passageway, which will connect the Fulton Street Transit Center with R train service and the World Trade Center Transit Hub, which provides PATH train service to New Jersey.

By the time the complex is complete, it will link 12 subway lines and is expected to serve 300,000 riders a day.

Years in the Making

The original concept for the project dates back to the 1990s. The transit center idea came out of the Lower Manhattan Access study, which aimed to improve transportation in Lower Manhattan, according to Bill Wheeler, director of MTA planning. One of the main report's proposals called for reconstruction of the Fulton Street Complex to make it easier for passengers to transfer between various trains and navigate the complex. The project, though, gained momentum after the 9/11 attacks as part of the general push to rebuild and improve lower Manhattan.

"Anyone who knows the transit system as they do knows that the complex is a mess and is a real pain for anyone who tries to negotiate from one line to another, especially if you're unfamiliar with it," said Jeffery Zupan, senior fellow for transportation at the Regional Plan Association. "It occurred to the MTA that they could put some money into this to help make the complex better and help Lower Manhattan. It didn't come out of nowhere, but it wasn't on top of the list."

Once completed, the transit center will connect the Fulton Street complex, with its 2, 3 ,4 and 5 train services- to the Cortland Street station that serves the R, the Broadway-Nassau Station with the A and C trains, and the Chambers Street-World Trade Center station, which serves the E and PATH trains. The station will also feature a glass station house with 23,000 square feet of retail space at Fulton Street and Broadway.

The centerpiece of the complex will be a large egg-shaped structure on top of the glass station house – usually referred to as the oculus -- that will act as a sunroof and reflect sunlight down to platform level.

The Right Answer?

While the existing subways stations needed work, Nicole Gelinas, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, contends that the Fulton Street Transit Center designed after 9/11 will not address the transportation problems in the area, namely the lack of direct connections to residential areas outside of the city. In her view, the entire project was the result of a rush to rebuild the downtown area after the 9/11 attacks.

"There was kind of this big focus that we have to rush to concentrate on the World Trade Center site, and maybe they should have done more to help the region," said Gelinas. "It may have been better for them to spend on actual rail connections."

According to Gelinas, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver played a big role into making the Fulton Street Transit Center a reality, the transit center being in his district. The speaker's office declined to respond.

"A lot of the rebuilding has been driven by local politics. Sheldon Silver really pushed this as one of the projects he's really been instrumental for," said Gelinas. "He made it clear in the months after 9/11 he wanted this transit center in lower Manhattan and to get funding for other projects, they [the MTA] supported this."

Designs and Delays

Groundbreaking on the transit center took place in June 2005, with completion originally slated for 2007. Cost overruns, though, started to become a problem in 2006, mainly due to the expense of relocating businesses on the site and acquiring property. In 2008, the MTA indicated that it might have to abandon the dome structure, which was the centerpiece of the project, and that there might not be any visible above ground structure. By this time, the project was slated to be done in 2010, and was $111 million over its original $799 million budget.

After reviewing and revising plans in, the MTA announced in 2009 the new completion date as June 2014, and the revised cost as $1.4 billion. Despite the federal government's refusal to pay for any cost overruns, the MTA received $423 million in stimulus funds to help continue the construction of the project. To keep costs from rising further, it was decided to narrow the Dey Street Passage from 40 feet to 29 feet. After going back and forth on the design of the Fulton Street station, the MTA is constructing the dome as originally planned, but with additional 23,000 square feet of retail space; to increase potential revenue for the project.

Some delays were attributed to engineering challenges in the area, including the reconstruction of the nearby Corbin Building, which will be 124 years old when construction is complete. Meanwhile the World Trade Center transportation center has also had its share of problems. The cost for the building – with its birdlike design by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava – could reach $3.8 billion and may not open until 2015.

According to the MTA, the Fulton Street project will cost roughly $1.4 billion, with 97 percent of that covered by federal funds. And now, according to Donovan, the transit center is being opened in sequence, with expected completion in June of 2014.

Zupan cites the complexity of the Fulton Street project as a key factor in the delays there, but he said the woes will be a distant memory once the general public sees the completed center.

"It's clear they've had problems moving forward, they had to redesign it to reduce cost. With many of these infrastructure projects they're very complex ... and it's very difficult to assess these things in advance," said Zupan. "When the project is done, it's going to last for 100 years, and it'll long be forgotten that the project is over budget and it took as long as it took."

Council Approves Fines for Taxi Refusal

Photo (cc)

The City Council wants to slam the brakes on the taxi industry's bad apples.

To ensure taxi drivers do not discriminate against passengers' destination -- or race -- the council approved legislation Wednesday that would drastically increase fines for drivers who refuse certain passengers. The bill, which was approved unanimously, is part of a larger effort by the Bloomberg administration to ensure residents of the outer boroughs receive taxi service like those in Manhattan.

"You wait around, your arm out and a taxi finally drives up," Council Speaker Christine Quinn said. "You try to get in the car, and the driver won't let you. You say, 'Queens,' and the next thing you know the cabbie just drives off."

The council's proposal, Quinn said, would deter this practice.

The city's taxi drivers, however, criticized the measure, arguing it exaggerates the prevalence of driver refusal and distracts from the real issue discouraging drivers from outer borough trips: the economy.

"They seem more interested in punishing drivers than actually addressing the issue," said Bhairavi Desai, the executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, which represents yellow cab drivers.

The proposal is the latest battle between the City Council, the Bloomberg administration and the taxi industry within the last month -- disputes that have gone from fare hikes to a new class of cab.

No Right to Refuse

The legislation, which the mayor is expected to sign, would also affect drivers who overcharge passengers and who illegally ask riders where they are going before entering the vehicle. Asking the destination before entry, said council officials, is often seen as a way to avoid outer borough rides.

Under the legislation, a first offense would increase from $350 to $500. If a driver receives a second offense within 24 months, the maximum fine would double -- from $500 to $1,000. If a driver receives a third violation in a 36-month period, he or she could lose their license.

According to the City Council, the 311 system receives about 300 overcharging complaints a year. For refusals, council officials said 311 receives between 200 and 300 complaints a month.

Desai said the refusal figures are exaggerated.

"They've overstated the problem," she said. "Refusal summonses are actually fairly low when you consider the hours people work and the trips they complete."

The alliance has released its own proposal to spur rides in the outer boroughs. Desai said the Taxi and Limousine Commission needs to first approve a fare hike, which would make trips to Brooklyn or Queens more economical for drivers.

The alliance submitted a fare proposal to the commission last week. It includes a 50-cent increase for mileage cost, from $2 to $2.50, and a 10-cent increase in the waiting time fare -- from 40 cents to 50 cents. For the night surcharge, which runs from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. daily, the alliance proposes a 50 cent increase, bringing it up to $1. The drivers are also asking for the first time for a morning rush hour $1 surcharge.

The Taxi and Limousine Commission has two months to consider the proposal, Desai said. If they decide to move forward with it, it would then have a hearing and eventually go to the commission for a vote.

To further increase service in the outer boroughs, Desai said the city should create pick-up stands around commercial or nightlife areas.

Back in January, the administration proposed allowing livery cabs to pick up street hails in the outer boroughs as a way to increase service. The practice is currently illegal -- livery service must be prearranged.

After the yellow cab industry and some City Council members expressed opposition, the administration went back to the drawing board.

Currently, said Taxi and Limousine Commissioner David Yassky anything is on the table. He is meeting with stakeholders to consider proposals -- from creating a new class or outer borough medallion to upping regulation of livery cabs.

"Our bottom line goal is to get decent taxi service in all five boroughs," Yassky said. "We're working daily with elected [officials] both in the City Council and the State Legislature to hash through the details of the plan that gets us the service we want."

South Jamaica Rezoning

In addition to the taxi legislation, the council also approved its largest rezoning, covering South Jamaica. The rezoning would preserve the area's low-density character, officials said, but also allow for larger building heights on main thoroughfares.

Taxi Choice Not the People's Choice

Photo courtesy of the City of New York

Th city has selected the NIssan NV200, a minivan not currently available in the U.., as the Taxi of Tomorrow.

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the Taxi of Tomorrow project in 2007, New Yorkers rejoiced at its the potential to create a custom-built fleet of taxis designed specifically for their city and their needs. In 2010 when the finalists were unveiled, the realization of a mode of transportation designed to accommodate all New Yorkers seemed even closer. But now, four months into 2011, the vehicle overwhelmingly supported by New York residents has been rejected, leaving the city with a feeling that the project may not have focused on their needs at all.

Yesterday, Bloomberg announced the city had selected the Nissan NV200 as the winner, choosing a car that some have described as "bulky and ugly." Apparently, according to the New York Times, an analysis commissioned by the city decided that Karsan's model proved to be the riskiest of the three finalists, because the Turkish company is "a new manufacturer, with a new manufacturing paradigm, not familiar with the U.S. regulatory framework, with no current sales, service or support infrastructure."

Therefore, eliminating the car from the competition was not based on the merits of the design or its concurrence with the project guidelines, but because of its lack of pedigree.

According to Jan Nuham, the executive director of Karsan, the company had never been informed of the analysis or of the city's specific. In fact, the city's analysis failed to mention that Karsan that has been manufacturing cars in Turkey for over 40 years and has built cars for Hyundai, Peugeot and Renault, all respected foreign models. In the past few years, a number of automakers -- Hyundai, for one -- that had been unknown names in the U.S. have become a reliable commodity -- something that the report seems to ignore.

(My father works for Karsan but the views here are entirely my own.)

Popular Appeal

What it comes down to is that the decision from City Hall shows a decidedly business emphasis and complete lack of regard for public opinion. From the outset of the project, information on the taxi competition was hard for the average New York resident to come by. In fact, when the finalists were announced in November, many people did not even know that there was a competition.

When the public was finally asked for its input, one model seemed to stand out among the rest. In a poll on the Taxi of Tomorrow website , about two-third of those responding preferred the Karsan taxi. The Daily News ran its own survey that showed dominant support for the Karsan model and in yet another poll, this one commissioned by the Taxi and Limousine Company, 66 percent of New Yorkers either liked or loved the Karsan model, supporting the 61 inches of leg room (the most of any finalist), four seat designed and clear sky roof for optimal viewing of the cities famous skyscrapers.

"The people of New York City have spoken, and they've found the taxi designs from both Ford and Nissan lacking," Zach Bowman of Autoblog wrote in February. "Around 66 percent of respondents either liked or loved the design of the Karsan V1, and that was enough to seal the vehicle's fate as the people's choice for the Taxi of Tomorrow."

Furthermore, as Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz laid out in a press conference Sunday boosting Karsan's bid, the Karsan model brought the promise of new jobs for the city. If it was awarded the contract, Karsan had pledged to manufacture its vehicles at the Brooklyn South Marine Terminal in Sunset Park, creating up to 800 new jobs for residents. Contrarily, the Nissan model will reportedly be built in Mexico, while the Ford model would be built miles from the Karsan plant in Turkey.

Markowitz as well as representatives of labor unions and additional city officials from throughout Brooklyn, lauded Karsan's proposal to manufacture in Brooklyn as being an important step toward creating well-paying, middle-class jobs for New York residents. As recently as November, Brooklyn had the second highest unemployment rate in the state of New York, just behind the Bronx, at 10.8 percent . The plant would begin to alleviate some of that pressure and start the process of rebuilding Brooklyn’s economy.

Accessibility

Also appearing at the press conference on Sunday were members of the disabled community, which has steadfastly supported the Karsan model. Currently, fewer than 300 of the city’s 13,000 taxis can accommodate a passenger using a wheelchair. The Taxi of Tomorrow Project was supposed to require 100 percent accessibility, but when the finalists were unveiled in November, only the Karsan model fully complied with the Americans with Disabilities Act. It featured retractable ramps on either side of the vehicle, making curbside loading and unloading possible for all passengers in wheelchairs without the assistance of a cab driver. Once inside the vehicle, there were lock-ins to keep wheelchairs in place and 47 inches of headroom to comfortably fit even the largest model wheelchairs. The Karsan vehicle would have made it possible for a passenger in a wheelchair to hail any of the 13,000 cabs in the city and enjoy the benefits of public transportation, just like every other New York City resident.

Yet, somehow, despite vast public support, the promise of jobs for New Yorkers and the commitment to make Taxis accessible to every New Yorker, whether they use a walker, wheelchair or push a stroller, City Hall turned a deaf ear. In its announcement the administration did not address either jobs or handicap access, though it did say the Nissan "received high scores" in the categories selected as high priorities by 26,000 people surveyed.

It did not take long for some other city leaders to express their displeasure. Brooklynites Markowitz and Public Advocate Bill de Blasio have written to City Comptroller John Liu asking that he look into a possible conflict of interest that may have tipped the competition against Karsan. They charge that the consultant the city hired to analyze the Taxi of Tomorrow finalists had prior relationships with both Nissan and Ford.

For now, though, Nissan has the city's endorsement. In rejecting Karsan, the Bloomberg administration squandered an opportunity for New York to be a beacon of individuality and accessibility, as well as the chance to create momentum for an economy that has one of the highest unemployment rates in the state. But New York's loss may be some other city's gain. In a statement issued shortly after Bloomberg announced New York's decision, Karsan's Executive Director Jan Nahum said, "We fervently believe that there is a strong market and an acute need for a true Taxi of Tomorrow, and we look forward to working with other forward-looking cities around the globe to make the Karsan vision a reality." So you may see that slightly futuristic car with the curved glass top soon -- just not in New York City.

Eric Samulski is a writer/filmmaker and life-long New York City resident. He is the son of Karsan USA's project manager, but the statements expressed above are his own.