large cities such as Taipei and Bogotá.

While U.S. cities such as San Diego and Las Vegas have recently rolled out bus rapid transit, New York can learn more from the experiences of cities in the developing world cities, such as Curitiba, Brazil, and Bogotá, Colombia. Like the emerging megacities of the south, New York urgently needs better transportation for a dense population that already embraces mass transit - and a solution that can be implemented quickly and cost-effectively.

In other US cities, transportation wonks debate whether bus rapid transit, or BRT, a series of measures to move buses faster and reduce waits, can make buses sufficiently attractive to attract upscale riders and/or spur transit-oriented development. In much of the country, what transit there is consists of conventional bus systems that are underfunded, often ill-managed and, as a result, used only by people too poor, too old or too disabled to drive. Planners trying to popularize transit in car-dominated cities fret over whether BRT has enough cachet to overcome the stigma attached to buses and the people who ride them.

In New York, though, our challenge isn't attracting enough riders to make transit viable - it's providing enough transit to handle what is already an overflow customer base, not to mention the million new riders that PlaNYC anticipates. The epic saga of the Second Avenue subway illustrates a hard truth - building new subway lines in New York City is too slow and costly to address a meaningful share of our need.

Even if money were no problem, few of the major rail projects on the boards would do much to make our commutes faster or less crowded. The extension of the Number 7 train extension is typical - it's about enabling development on the far West Side, not about improving the lives of the people packed onto that train today.

Transit-starved in a Transit-rich City

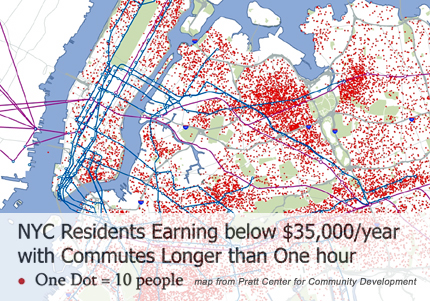

Meanwhile, three quarters of a million New Yorkers now travel over an hour each way to work. Two thirds of these commuters are on their way to jobs that pay less than $35,000 per year. These are folks who live at the far ends of subway lines or in places the subway doesn't go, or who commute to places the subway doesn't connect them to.

Rising housing costs have forced many low- and moderate-income people out of neighborhoods with good access to transit - such as Harlem, Williamsburg, Jackson Heights, to name a few -- to places like Soundview, East Flatbush, East Elmhurst and many others from which it's a bus ride or maybe two bus rides to the closest subway.

Another factor is where the jobs are. While jobs in the financial and creative sectors are concentrated in Manhattan, low- and moderate-wage employment in services, the trades and manufacturing is dispersed across the city. Most New Yorkers work in the same borough they live in, but unless that borough is Manhattan, this translates into long transit trips to work. An intra-borough trip that might take 20 minutes by car can take 45 minutes or more by bus because buses are slow and connections are poor.

As a result, poor transit access restricts economic opportunity. Workers with less than a college degree already struggle to find a limited universe of jobs that are a match for their skills; that universe is further reduced when they consider only jobs within a manageable commute from transit-poor neighborhoods. And opportunities for advancement through education are likely to be confined to the unaccredited colleges and trade schools that cluster around outer-borough transit hubs.

Long commutes also undermine family and community life. Low-wage workers seldom have the flexibility that allows higher-earning parents to juggle school and community meetings, get kids to after-school activities, doctor visits, etc., and handle the inevitable emergencies. When workplaces are an hour away from home, school and childcare, it's hard to find time for more than the most basic parenting tasks.

Many of New York's public housing developments are transit-deprived. Robert Moses, in particular, tended to build projects in isolated areas where land was cheap and local opposition was minimal. The Master Builder may not have cared whether his tenants had access to jobs, education, and services -- so to this day, tens of thousands of public housing residents remain stranded far from the nearest subway line.

BRT and Neighborhoods

As Phase 1 of the Second Avenue Subway inches toward completion, nobody in Morrisania, Canarsie or South Jamaica is holding their breaths waiting for the train to come in. But bus rapid transit -- "a subway running above the ground on rubber tires" could be in place relatively quickly and cheaply. Full BRT - with protected lanes, traffic signal prioritization and off-board fare payment - can move people at speeds and volumes that dramatically shorten travel times over long routes. Moreover, BRT will be accessible from its inception - to wheelchair users, seniors and everybody who has trouble climbing stairs - while the goal of providing access at every subway stop is still many years away. BRT will create an efficient no-transfer option for hundreds of thousands of people whose mobility is now limited to the radius a conventional bus can cover at a speed of 7.9 miles per hour.

Though dedicating lanes to buses presents a political challenge, BRT complements plans to reduce car use by making more efficient use of street space. There are a number of ways to ensure that the lanes are used by buses and buses alone. The lanes can be physically protected, but license plate cameras on the buses themselves are a more elegant solution -- letting the buses themselves nab the drivers who infringe on their space. However, enforcement cameras face an uncertain fate in the state legislature, where Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has thus far resisted pressure to authorize additional red-light cameras in the city.

The City's First Steps

On March 25, Mayor Michel Bloomberg presided over the joint announcement of New York's first BRT route by Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan and Lee Sander, executive director of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Dubbed "Select Bus Service," it will replace limited-stop Bx12 service on Fordham Road/Pelham Parkway in the Bronx starting June 29. Most of the key BRT features are part of the package including off-board fare payment. Machines at bus stops will accept MetroCards or cash in exchange for a paper receipt. Following the example of many European transit systems, riders will be subject to random checks - but passengers will be able to board through front and rear doors, eliminating the bottleneck that forms as each rider swipes at the front door.

BRT-specific vehicles - low-floor buses with multiple doors - are still in the future, but the willingness of the transportation department and MTA to try "honor system" payment, as well as the department's painstaking work with local stakeholders to resolve conflicts around truck unloading and parking, signals a will to make this first route work. The more successful the initial BRT project is, Sadik-Khan reasons, the more communities will clamor for BRT to come to them as well.

Transit Funding without Congestion Pricing

Now that the state has failed to act on congestion pricing, when BRT will roll in the other boroughs is anybody's guess. The federal Urban Partnership grant that New York forfeited when the State Assembly did not vote on congestion pricing earlier this month would have funded a five-route pilot project, adding one BRT route each in Staten Island and Brooklyn, and two in Manhattan. (Resistance to the removal of some parking along Merrick Boulevard was so fierce that plans for a Queens route were put on hold, and a 34th Street crosstown route advanced in its place.) Of the $354 million in federal funds, $112 million would have paid for BRT.

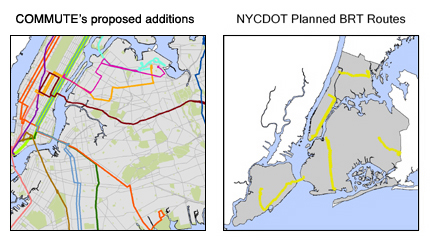

Meanwhile, a small but growing number of transit advocates and riders who know what BRT is are clamoring for more routes. COMMUTE! (Communities United for Transportation Equity), a coalition of community groups coordinated by the Pratt Center for Community Development, wants the BRT routes to cross bridges and connect the boroughs, making buses a more serious complement to the subway system.

The pilot program confined each route to its respective borough, so that the Rogers Avenue/Nostrand Avenue route in Brooklyn would serve a dense and underserved slice of East Flatbush, Crown Heights and Bushwick - but then dump passengers at Williamsburg Bridge plaza, presumably to elbow their way onto already full J, M and Z trains to get into Manhattan. Since the transportation department is already planning to put a dedicated bus lane on the Williamsburg Bridge, it would be logical to connect the Brooklyn BRT route to the also-planned First/Second Avenue BRT.

With both the one-time shot of federal funding and the projected $500 million per year in net revenues from congestion pricing off the table for the moment, BRT may be more important than ever. The MTA Capital Plan has, in words of Straphangers Campaign spokesman Gene Russianoff, "more hole than plan," with less than $12 billion of a five-year, $29 billion shopping list accounted for. As the rail and subway projects envisioned in that plan recede into the future, BRT makes more sense than ever. It will not prevent us from building light rail or subways in the future, but for now it makes intelligent use of the infrastructure we already have - our streets.

Joan Byron is the director of the Sustainability and Environmental Justice Initiative at the Pratt Center for Community Development.Â