Wall Street's Binge, Workers' Hangover

The turmoil and uncertainty on Wall Street continues, punctuated by Merrill Lynch’s recognition last month that it had lost $8 billion in sub-prime backed mortgage securities. The profitability of many of New York’s financial giants has eroded and layoffs have multiplied, worrying city and state budget makers.

The latest losses, following three years of big gains, indicate the pitfalls of Wall Street’s all too frequent speculative binges. Wall Street’s tendency to create investment fads that enrich the few at the expense of the many, whether through dot.coms, Enrons, risky mortgages or whatever might come next, is not a smart way to run an economy. Beyond that, it all too often distracts attention from the financial realities facing people who live and work in the broader economy beyond Wall Street.

So, how are those people doing and how are they likely to fare if Wall Street’s woes continue?

Lately, wages and incomes have improved a little. Given that the economy has been in recovery since mid-2003 from 9/11 and the recession earlier in the decade, some gains should be expected. What’s surprising is that they took a while to materialize.

Against this backdrop, however, there are some troubling long-term trends in the New York economy. These trends have a lot to do with the economic well-being of average people and the neighborhood economy as opposed to the Wall Street economy that receives most of the media attention.

INCREASES IN INCOME

First, let’s take stock of the good economic news.

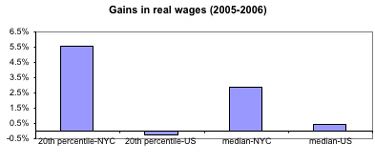

Hourly wages for most New York City workers, after adjusting for inflation, rose in 2006 and now are roughly back to 2002 levels. The New York worker in the exact middle of the pay scale made $15.38 an hour in 2006, 2.9 percent more than in 2005.The worker at the 20th percentile of the wage spectrum – a level representative of a low-wage worker – earned $9.27 an hour in 2006, 5.6 percent more than in 2005.

And as the graph below shows, wages for typical workers last year fared better in New York City than in the country in general.

NYC VS. U.S. 2005-2006, MEDIAN AND 20TH PERCENTILE HOURLY WAGE

Undoubtedly, earnings for low-wage workers received a boost from the increases in New York State’s minimum wage in 2005 and 2006 while the federal minimum wage of $5.15 remain unchanged until it was finally increased this July. New York’s minimum wage is now $7.15 an hour (a third and final increase took effect in January). The first of three annual 70-cent increases in the federal minimum wage lifted it to $5.85 in July.

Median family income has risen in New York City since 2003, climbing to $51,830 in 2006. Taking inflation into account, family incomes increased 3.9 percent between 2004 and 2006. This improvement resulted from increased wages and a slight increase in the number of people working. (It may also be that some of the apparent family income improvement results from a number of moderate income people –- those with incomes from $40,000 to $60,000 -- leaving the city, possibly due to rising housing costs and being replaced by more affluent household. See this report from the city comptroller’s office.)

Still, the city’s median family income is slightly more than 10 percent less than the U.S. median family income of $58,526.

SIGNS OF TROUBLE

The recent improvements in wages and family incomes are certainly welcome, but they could be short-lived given the turmoil on Wall Street and the likelihood that the national sub-prime lending crisis and housing market troubles will decisively slow overall economic growth. There is a growing realization that a good part of the national growth of recent years was fueled by the reckless expansion of sub-prime lending and other questionable Wall Street practices. Growth was fueled by excessive borrowing because there was not a broad-based growth in incomes.

There is more to the lopsided character of economic growth than irresponsible lending and the collapse of the housing bubble. The Fiscal Policy Institute’s recent The State of Working New York 2007 report highlighted other “troubling trends” that put recent economic news in perspective. These “troubling trends” characterize the state’s as well as New York City’s economy.

The “Productivity-Wage Gap”

Overall consumption spending has out-paced any growth in income and wages. Workers have not been sharing in the fruits of their labor. The “productivity” of New York workers – the value of what they produce -- has risen by over 11 percent since 2000 while inflation-adjusted average wages grew by only 1.1 percent. The emergence of this “wage-productivity gap” since 2000 is reflected in the fact that nationally, corporate profits have grown four times faster than total wages over the last six years.

Less Job Security, Fewer Benefits

An increasing number of businesses are hiring workers as “independent contractors” in place of employees. This results in a deterioration of working conditions and puts strains on social insurance systems. Employees get a range of benefits long taken for granted and essential to middle-class economic security: overtime pay, sick leave, co-payment of Social Security and coverage by workers compensation and unemployment insurance. As an “independent contractor,” a worker gets none of these. Nearly 10 percent of all private workers in New York are “misclassified” as independent contractors. The economic well-being of such workers undoubtedly falters compared to the status of a regular payroll employee.

This “misclassification” trend is part of the broader pattern of unregulated work and employer noncompliance with labor laws. Governor Eliot Spitzer recently issued an Executive Order, establishing an inter-agency task force to crack down on the illegal use of independent contractors.

Poverty-level Jobs

Despite recent wage and income gains, the number of working families who are poor or near poor is much higher now than it was in 1990. Today, poor people are more likely to have a job than was the case 15 years ago. Since so many jobs pay very low wages, having a job is no assurance of a decent standard of living. The number of people in working families in New York City who are poor, as defined by the federal poverty standard, has risen by two-thirds (222,000) from 1990 to 2005. Some 560,000 New Yorkers live in poor families, including over 250,000 children. Nearly half (47 percent) of children in working families in New York City live in families with incomes less than twice the poverty level. (The federal poverty level for a family of four is now about $20,000 a year).

A Widening Income Gap

Census data for 2006 confirm that New York State has the widest income gap between the rich and the poor (and the widest gap between the rich and the idle) of all 50 states. New York City’s income gap between the rich and the poor is considerably greater than for the state as a whole. In 2004, the richest 5 percent of people in the state accounted for 38 percent of all income while in the city, the top 5 percent garnered 47 of all income. Recent projections by the state Division of the Budget indicate the share of income flowing to the richest five percent jumped markedly between 2004 and 2007, a statewide trend that would also be evident in New York City.

All indications are that New York City’s economic recovery and expansion that began in mid-2003 is tapering off. The wage and income gains for most New Yorkers that finally materialized over the past year or two could be short-lived.

To confront this should involve more than crossing our fingers and waiting for the next Wall Street bubble to make things better. As with the increase in the minimum wage and the pending crackdown on the “misclassification” of workers, policy makers need to hone in on changes that will make a difference for average people striving to make ends meet in a city with a rising cost of living and in an economy that is all-too-prone to Wall Street-driven boom and bust. Otherwise, the “troubling” longer-term trends will completely swamp the short-lived gains that show up only at the top of the boom-bust cycle.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.Â

Reviewing Federal and City Tax Cuts

The large tax cuts in the city’s budget -- $1.6 billion in 2008, growing to an estimated $2.2 billion in 2011 – are part of a national tax-cutting movement that has flourished since 2001.

What, though, is the impact of cutting taxes? And how do New York City’s efforts to cut taxes compare with the moves taken by the Bush administration at the national level?

The national and city cuts both have reduced tax bills, particularly for people with high incomes. Neither has sought to make the tax system much fairer for people at the lower end of the economic ladder. But President George W. Bush’s tax cutting springs at least partly from ideology while Mayor Michael Bloomberg has been more pragmatic, adjusting his tax policies to meet immediate fiscal realities. The president’s tax cuts have spawned large deficits, but Bloomberg, who by law must balance his budget, has seen large surpluses for much of his administration — at least until now.

A Sea of Red Ink

Several new studies on Bush’s 2001 and 2003 federal tax cuts find that the cuts have had a regressive impact, widening the gap between the rich and the rest of America.

According to the president, the tax cuts have spurred the economy. He has also said they put more money in the hands of individuals as opposed to government. To some extent, that is correct. The tax cuts cost the federal government about $300 billion in lost revenues in fiscal year 2007 alone, according to a July report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Because the federal government has had to borrow money to pay for those tax cuts, the reductions have contributed to the $3 trillion that Bush has added to the national debt since he became president in 2001.

As reported in a September 13 report by Citizens for Tax Justice, a research and advocacy group, the impact of the tax cuts and the size of the new debt is masked by the way in which Bush defines annual “deficits.” The president announced this summer that estimates of the 2007 budget deficit had dropped from $244 billion to $205 billion. That figure, though, included only the $205 billion borrowed from outside government to help balance the federal budget. It does not consider the additional $180 billion in Social Security funds Washington borrowed. Including that brings the actual deficit to $385 billion. The best one can say is that the projected $385 billion actual deficit in 2007 is lower than the deficits of more than $500 billion a year that the federal government ran in 2003, 2004 and 2005.

The result of this deficit spending is that the Congress has had to raise the national debt limit five times. The new limit will be $9.815 trillion, some $3.9 trillion more than it was when Bush took office.

Shifting the Tax Burden

In an April report, Citizens for Tax Justice noted that, contrary to popular opinion, the United States is one of the least taxed industrial countries in the world. Of 30 nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, only two, South Korea and Mexico, have lower taxes. In 2005, total federal, state and local taxes in the U.S. were 25.8 percent of our economy, as measured by our gross domestic product (GDP, the market value of goods and services). The 27 countries with higher taxes ranged from Japan – with taxes at 26.4 percent of GDP – to Sweden at 51.1 percent.

Because of relatively high income and property tax rates, residents of New York State pay a greater percentage of their income in taxes than most other Americans. The federal state and local tax bill for an individual in the U.S. averaged $3,699 in 2005, according to figurescompiled by the Business Council of New York State. New York State residents, the council said, paid an average of $5,770.

The Citizens for Tax Justice report also shows that in the last 40 years there have been significant shifts in taxes, both as a percentage of the economy (measured by the GDP) and in individual taxes as a percentage of total taxes. Business taxes account for a much smaller percentage of total taxes today than in the 1960s. In 1965, U.S. corporate income taxes were 4.0 percent of our GDP. By 2004 they represented only 1.9 percent of GDP.

Personal income taxes are the main source of U.S. federal (and many state) tax revenues. In 2000, largely reflecting President Bill Clinton’s 1993 progressive (i.e., higher earners pay at a higher tax rate) new top rate of 39.6 percent, total personal income taxes in the nation (including state and local taxes) accounted for 41 percent of all taxes. After Bush and the Republican Congress dropped the top rate to 35 percent in 2001, personal income taxes as a percentage of all taxes declined to 34 percent by 2004. Since the bulk of personal income tax revenues comes from higher income households, this high-income households save much more money than lower-income ones.

At the same time working- and middle-class households are carrying a higher tax burden because of social insurance and payroll taxes like Social Security and Medicare. In 1965, these taxes were only 13 percent of all the nation’s taxes. Since 2002 they have totaled 27 percent of all taxes each year.

The 2003 capital gains and dividend income tax cuts have proved particularly regressive. The capital gains rate was cut from 20 percent to 15 percent. And the tax rate on dividend income, which had been treated as ordinary income at the time and so taxed up to 35 percent, was also cut to 15 percent.

It will come as no surprise that the very rich made out like, well, bandits. An August 10 Citizens for Tax Justice report shows that the cost in 2005 alone of the capital gains and dividend income cuts was $92 billion. Three quarters of the benefit went to less than 0.6 percent of all tax filers, providing those earning over $500,000 in 2005 with an average benefit of $81,204.

“Most amazing, the 13,776 tax filers with adjusted gross income in excess of $10 million – a mere 0.01 percent of all filers – received 28.2 percent of the total tax savings,” the report said. Their average tax break was almost $1.9 million.

A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report issued in March 2007, asked, “Have the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts made the tax code more progressive?” No, it answered. The 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, the report said, “will increase the incomes of high-income households by a much larger percentage than the incomes of low- or middle income households.”

It calculated that if the tax cuts become permanent – they are currently scheduled to expire at the end of 2010 – by 2012, those earning over $1 million a year will see an increase of 7.5 percent in income, compared to only a 2.3 percent increase for middle-income households and an increase of just one half of one percent for the one fifth of households with the lowest income.

Conservative proponents of the tax cuts argue that the rich pay a higher share of taxes now than they did before the cuts. Yes, between 2000 and 2004 the share of personal income taxes paid by the top 1 percent of taxpayers went up slightly, from 36.5 percent of all personal income taxes paid to 36.7 percent. But total income tax revenues dropped by $250 billion between 2000 and 2004 because of the rate cuts, so the top 1 percent paid about $100 billion less than they would otherwise have paid at the higher rates in 2000.

Further, between 2000 and 2004, federal income tax rates dropped by 4.6 percentage points for the top 1 percent of taxpayers, 2.1 percentage points for those in the middle of the income scale, and by only 1.6 percentage points for those at the bottom.

New York City’s Tax Cuts

The Bush tax cuts clearly reflect a conservative, regressive-tax ideology. The recent New York City cuts are harder to characterize.

During his more than five years in office, Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s policies reflected no consistent position on taxation. Instead, he has variously adjusted the city’s tax system for pragmatic and political reasons.

The mayor determined in 2003 that the city needed $2 billion in new taxes to avoid a huge deficit, and he increased all the big taxes (except on corporate income): property, personal income and sales taxes. In 2007 he went the other way and cut taxes by $2 billion a year because he had the (one-year) surplus money to do it. At the same time, Bloomberg shows little interest in a progressive tax agenda.

The elimination of the 4 percent city sales tax on all clothing in the 2008 budget is marginally progressive, since clothing expenses as a percentage of income will be slightly lower for low-income households. But the loss of tens of millions of dollars in high-end taxes on clothing like the outfits touted in the recent fashion shows is a reminder of how much the modest gains for low-income New Yorkers have cost us.

The biggest part of the 2008 cuts – the across-the-board property tax rate cut and residential owner ($400) rebate -- no doubt eased the tax burden of many lower- and middle-income homeowners who needed it (and many wealthy residential owners who didn’t), but the bulk of the rate-cut benefit went to large corporate property owners.

Further, the one significant progressive idea in recent years never made it into the adopted budget because the mayor rejected the City Council’s proposed $300 rebate to low- and middle-income renters. That’s a missed opportunity.

In terms of creating a more progressive city tax system, the city’s personal income tax offers a big opportunity. The rates for this tax currently resemble a flat tax (where everyone pays the same tax rate, regardless of income) because they range only from a 2.9 rate for joint filer with an annual taxable income of $21,600 or less to a top rate of 3.7 percent for joint filers making $90,000 or more. There were higher top rates through much of the 1990s and from 2003 to 2006.

In comparison, the federal personal income tax has six brackets and ranges from 10 percent on joint taxable incomes up to $15,650 to 35 percent on joint taxable incomes above $350,000.

Without a more progressive personal income tax rate structure and without a review of inequities in the property tax system, the city under its current leadership seems likely to continue to use taxes – reducing them or increasing them in an ad hoc way -- as immediate economic conditions dictate. That’s non-ideological, but it’s also a missed chance to establish a fair and more stable city tax policy for the long term.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Worrying About Wall Street

Although Wall Street firms employ only 5 percent of workers in New York City, they account for 20 percent of the city's total wages and salaries. Any ups or downs in the financial district can subsequently create a ripple effect elsewhere, seeping unsteadiness and insecurity into the pockets of New Yorkers citywide, from real estate brokers to waiters.

Thus, when the market acts volatile – as it did on Friday following a U.S. government report on job losses -- the city is at risk.

The End of an Era?

As the stock market dives and climbs, plummets and rallies, city financial experts and officials cannot help but ponder what effects that could have on the city's overall economy and the city government's upbeat fiscal outlook.

Some fear the current turmoil could end a rosy economic era that featured billions in budget surpluses, which enabled the city to cut taxes it had raised during a recession earlier in the decade.

"People have gotten used to, in the last several years, for every year to be better than the last," said Marcia J. Van Wagner, the city's deputy comptroller for budget. "I think what is going to happen here, as the economy turns a little bit, we're going to have to get out of the habit of thinking that way."

The Bloomberg administration, the city's Independent Budget Office and the city comptroller's office all expected an economic slowdown even before the recent dives. The Bloomberg administration’s decision to use some $2.3 billion in this year's budget to cover debt service in future years, Van Wagner said, could offer some initial protection. Although it is still too early to speculate on future fallouts from the market, Van Wagner added that any concern should not be directed toward this calendar year, but the next.

Wall Street's Reach

The city relies on revenues received from Wall Street. Bonuses alone last year, estimated Van Wagner, contributed $20 billion to the city's economy. These bonuses, Wall Street wages and capital gains have accounted for nearly half of the state's growth in its income tax base since 2003.

The market's swings - sparked by a so-called crisis in the sub-prime mortgage market and subsequent credit crunch (see related stories below) – could affect other industries as well. Sales of luxury items could decrease, New York City's soaring housing market could sink, nonprofit organizations could have difficulty fundraising, brokers could lose their jobs and gourmets might find it easier to get a table at exclusive restaurants, said city officials.

However, Van Wagner said, there is no reason to panic. "There are certain people who have jobs in certain parts of Wall Street that have every reason to be worried right now," said Van Wagner. "For New York City residents in general, I don't think they should be alarmed at the moment."

Predicting the Future

That should officials watch for? City officials said they would turn to business tax returns due at the end of the month as an economic indicator. They will also keep an eye on layoffs. Employment growth is another indicator to watch. The comptroller's office projected that employment in the city would grow by 50,000 jobs this year, and it has already increased by 54,000, Van Wagner said.

Nationally, however, employment dropped in August for the first time in four years. On Friday, an employment report revealed the country had a net job loss of 4,000 last month, despite economists' predictions of more than a 100,000 gain. The stock market's drop in response indicated how national economic developments could affect New York's financial workforce and eventually the wider city economy.

In the months to come, New York City definitely will see a slowdown in its economy, said Doug Turetsky of the city's Independent Budget Office. How bad it is or whether it's better than previous estimates, remains to be seen, he added.

"The city is still very dependent on the financial services sector," said Turetsky. "It's still the main driver of the New York City economy. We haven't had the kind of diversification that people have talked about that would help the city insulate from the cyclical downward trend that Wall Street goes through."

Others are not so pessimistic. James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute wrote in Gotham Gazette that Wall Street would have to go into a “sustained slump” for city economy to suffer a serious downturn. “Many other parts of the economy should continue to generate jobs and economic stimulus – even if the stock market gets the jitters,” Parrott said.

Whatever happens in the long run though, the coming days promise to be anxious ones on Wall Street as experts try to figure out whether August’s job loss represented a one-month glitch or an early sign of a looming recession. And as long as there are jitters on Wall Street, there promise to be some restless moments in City Hall as well.

Also this week:

--Charles Geisst, a professor of finance at Manhattan College, predicts real estate brokers are likely to see prices fall as a result of turmoil on Wall Street and in the national housing market.

--New York City-based credit risk analyst Rebecca Jones explains the foreclosure crisis and looks at whether – and how – it affects New York City.

Related coverage in Gotham Gazette:

• Jittery Wall Street, Calm City? (April 16, 2007)

by James Parrott

Even though New York remains heavily dependent on Wall Street, other sectors of the local economy continue to remain strong.

• Neighborhoods and the Fiscal Boom (August 2007)

by James Parrott

The economy's surge on a citywide scale has boosted tax revenues, but some communities have not felt the full effects of the good times.

• Looking at the Four-Year Financial Plan (August 2007)

by Glenn Pasanen

How the city plans on spending its money – including all those surpluses -- over the next several years.

• Behind the Low Unemployment Rate (May 2007)

by James Parrott

Why the city’s jobless rate has reached an all-time low.

• Wall Street Bonus Babies (January 2005)

by Andrew Beveridge

Who gets Wall Street's record-breaking bonuses.

Â

Looking at the Four-Year Financial Plan

The latest gyrations on Wall Street may complicate the city's financial picture somewhat but, assuming things do not go badly awry, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council can look forward to one and maybe two happy budget years. That's the finding of the city’s three major fiscal monitors in their July reports on the city’s recently adopted 2008-2011 financial plan.

The reports from the city comptroller, state comptroller and stateFinancial Control Board are especially informative on three major components of the plan: the big four-year tax cut, the large increase in education funding and city’s plans to spend the $6.5 billion “windfall” that accumulated in 2007. They also provide insight into the capital budget, hiring and accountability in education and stress what they see as the plan’s fiscal prudence.

The $6.5 Billion Surplus

Enjoying $6.5 billion in “surplus resources” the city, in the fiscal year that ended in June, pre-paid $2.7 billion that would otherwise be due in 2008, $2.9 billion due in 2009 and $1 billion for 2010. In doing this, the government retired $1.2 billion of debt early and spent $4.7 billion (what the mayor calls the official 2007 “surplus”) on other pre-payments, mostly on debt service.

This unique distribution of excess one-year revenues over three years apparently encouraged the big tax cuts, which cost $1.6 billion in 2008 and $2.2 billion in 2011. The monitors accepted and even cheered the tax cuts -- despite their professed worries about long-term budget problems. The state comptroller’s report applauds the tax cuts because they “stimulate economic activity and improve the city’s competitiveness with surrounding jurisdictions”

Bloomberg has often said that taxes have little effect on business location decisions. So who actually benefits from the property tax cuts?

Of the $1.6 billion in 2008 tax cuts, $1.05 billion came form the cut in the property tax rate. Although the mayor and council spoke of a 7 percent cut in the property tax rate, that was only an average. In fact, different types of property got different rate cuts, because of the bizarre structure of the city’s property tax system.

Commercial properties got an 8.5 percent rate cut and private home owners got a 4.2 percent rate cut. But that was actually good news for the home owners, because without a last-minute change in state law in June, they would have seen a slight rate increase under existing law, according to the control board.

Many of the ostensible gains from the rate cuts were washed out by increases in assessments. Projected revenue from the property tax system in 2008 is nearly $13 billion, or about $50 million higher than in 2007, says the control board.

Property market values increased by $122 billion, or over 18 percent, in 2007, according to the city comptroller. And assessments, which determine actual taxes paid and are always much lower than market values, went up $9.3 billion, or about 8 percent. (The actual tax for a home or business is the property’s tax rate times its assessment.)

The financial reduction plan also included elimination of the city sales tax on clothing, a child care tax credit and some business tax cuts. Together, over four years, they will cost a total of nearly $8 billion, according to the city comptroller.

Money to the Classrooms

The other big new expenditure in the plan is for the city’s public schools. By 2011, funding for the city’s public schools will rise by $5.5 billion, according to the state comptroller’s report.

The report shows a shift in education funding, from the city to the state, as a result of the settlement of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity case on spending for schools. Although both the city and state will greatly increase their funding for education over the four years, more will come from the state. In 2007 the total education budget (including pension and debt service costs) was $18.6 billion. Some $9.5 billion, or 50.9 percent, of that is city funds; $7.2 billion, or 38.9 percent, is state funds; $1.8 billion, or 9.8 percent, is federal funds.

By 2011 the education budget (including pension and debt service costs) will be $5.5 billion higher, or more than $24 billion. The financial plan assumes the city will then be paying $11.9 billion, or 49.2 percent of the total education funding, and the state $10.3 billion, or 42.6 percent.

Perhaps the best illustration of the increase in education spending is in the city comptroller’s report, which points out that per-pupil spending in Department of Education programs will jump by 35 percent over four years. “Even after adjusting for inflation, projected per pupil spending would still jump 23 percent during [the four-year] period, driven primarily by a 33 percent increase in real dollar growth for instructional spending,” the comptroller said.

With all this money come worries about accountability and management in the city’s education department. As the state comptroller points out, the increase in state education funding comes with strings: “The state will now require the city to submit plans and report annually on how it will use additional state education aid to improve student academic performance and to achieve other measurable educational goals.” The State Board of Regents is developing additional accountability measures. At the same time, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity and other advocates have criticized the Bloomberg’s administration’s plans for some of the state funding.

Plusses and Minuses

Overall, the city’s expense budget is projected to increase from $59.1 billion in 2008 to $69.1 billion in 2011. According to the financial control board, the bulk of the increase goes to wages, pensions, health insurance and other benefits for city workers (reaching $37.9 billion in 2011); Medicaid ($5.9 billion in 2011); and debt service ($6.2 billion in 2011) for the city’s capital program.

Other spending – so-called discretionary, other-than-personal-service, which includes all the contracted youth, health, social, and other human services – will rise by only 0.8 billion over four years.

The monitors include some other interesting details:

-- The city realized over $1.2 billion from tax audits in 2007, far more than the $600 million it usually gets from such audits each year. According to the state comptroller, the increase stemmed from “the settlement of several outstanding audits of financial firms and the clarification of the tax treatment of investment capital,” another example of the city budget’s dependence on Wall Street.

-- The city-funded workforce increased by 12,186 from fiscal 2004 to 2007, to about 264,000. Another 6,095 will be added in 2008. The largest growth is in new hires for the Department of Education. The uniformed police force remains at about 35,500, 11.5 percent below the total in June 2000. Since 2004, the police department has added 1,411 civilians to replace uniformed officers performing administrative duties, a cost-saving reform long sought by city comptrollers and council members.

-- The city has a massive $83.7 billion ten-year capital plan. By far the biggest element, according to the financial control board report, is the education capital budget of $28.2 billion. Some $20.4 billion of that will go toward bringing current schools to a state of good repair. More than 50 percent of the funding for the education capital projects, it is currently assumed, will be provided by the state.

--At the same time, the control board reports, the city will invest only $2.5 billion of the $5.1 billion needed to bring city capital assets up to a state of good repair over the next four years. The $5.1 billion figure comes from the recently published 2007 Maintenance Report. Projected highway maintenance funding is only $885 million of a recommended $1.9 billion. Bridge maintenance, on the other hand, is fully funded at just under $1 billion over four years.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Lessons from Deutsche Bank

August 18 was a tragic reminder of the dangers associated with rebuilding our community six years after September 11, 2001. Two firefighters, Robert Beddia and Joe Graffagnino, needlessly died putting out a fire at 130 Liberty Street at a building that had long sparked controversy.

The History of a Troubled Site

When Community Board 1 urged the adoption of an emergency and community notification plan in October 2005, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation told the board that residents should "call 911."

Unsatisfied with this clearly problematic answer, Chairperson Julie Menin wrote to then President Stefan Pryor of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation regarding the need to expeditiously implement a codified community notification plan with phone trees. We proposed a myriad of ideas, including email blasts, building captains and two-way hand-held radios. Unfortunately, the letter received no response.

On April 18, 2006, Community Board 1 unanimously passed a resolution expressing our serious concerns about the safety record of Bovis Lend Lease’s subcontractor, John Galt Corporation. Specifically, the board questioned the poor safety record of John Galt and one of its affiliates.

In addition, Community Board 1 had pulled out of a Lower Manhattan Development Corporation sponsored “open house” on October 24, 2005 when the previous corporation's administration under Governor George Pataki would not let the community ask questions publicly.

The Actions Since The Fire

In light of the most recent tragedy at Ground Zero, we once again met with state and local leaders to discuss the need for a notification and an emergency plan.

Three days following the fire, Community Board 1 members met with Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, the Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center and other elected officials. At that meeting, we discussed the need for a notification and emergency plan to be in place and our concern with Bovis Lend Lease and their subcontractor John Galt, as we had done numerous times in the past.

Community Board 1 held an emergency public hearing following that meeting, which also included representatives from numerous city, state and federal offices, such as the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center, the Bloomberg administration, the Community Assistance Unit, Department of Buildings, the fire department, Office of Emergency Management, Department of Environmental Protection, Department of Health & Mental Hygiene, the federal Occupational Safety Health Administration and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – Region 2.

More than 100 downtown community members attended, serving as a true testament to the dedication and concern downtown residents have about our community. The meeting not only gave the downtown community an opportunity to hear directly from the agencies involved but also resulted in many productive initial steps.

First, we urged that John Galt [which has since been fired] be removed from the job, given the numerous Occupational Safety Health Administration violations and buildings department complaints against it. (Although Bovis Lend Lease and John Galt were specifically invited, they failed to appear much to the consternation of the community). [Bovis has since agreed to meet with Community Board 1 and other elected officials.]

Second, at this meeting Edward Skyler, the deputy mayor for administration, and Lower Manhattan Development Corporation Chairman Avi Schick committed to meet with Community Board 1 immediately to devise a community notification plan.

Third, we voiced our strong concerns that the Deutsche Bank building be immediately resealed without any delay.

Fourth, fire inspection teams will be evaluating the fire-fighting systems inside two other buildings that will be shortly decontaminated and deconstructed/rehabilitated -- Fiterman Hall at the Borough of Manhattan Community College and 130 Cedar Street, respectively.

Where We Go From Here

Although we all want the 130 Liberty Street building to be taken down, we have requested that it be done in a manner that is safe for both the workers, first responders and the people who live and work nearby. The next steps include:

1. Secure the fire-damaged, World Trade Center-contaminated building so that debris will not fall out and injure someone. [Two firefighters were injuredlast Thursday at the site when a John Galt worker lost control of a forklift and it toppled from the building].

2. Determine why the fire occurred and put in place a plan so that it will never happen again. Such a plan should mandate that the water main that supplies water to the building and various floors would be functioning during the remainder of this difficult project.

3. Develop a contingency plan for various emergencies – including fighting a fire – and make sure that as work proceeds in this building the response team is given the floor plans as they change.

4. Create an effective communication plan from city agencies to neighborhood residents and businesses – consider text messaging, a phone tree, reverse 911, televised announcements and e-mail blasts in real time. Such communications should include whether residents/workers should evacuate or stay in their homes or at work, whether they need emergency breathing apparatus and if a building is in danger of collapse.

5. Determine whether the fire re-contaminated the previously decontaminated area, and if so, require such area to be re-cleaned and re-inspected prior to demolition.

6. Review the impact of water damage from putting out the fire so that mold will not be an issue in the remaining hot days of summer.

7. Hire a responsible subcontractor to replace John Galt -- one that, as required by the Procurement Policy Board Rules of the City of New York, is capable "in all respects to perform the contract requirements fully" and has "the business integrity to justify the award of public tax dollars."

8. Require vigilant enforcement of city building, construction, safety, and fire codes and regulations --including no smoking on the construction site.

9. Test residential and work areas in the immediate area and, if necessary, clean them.

It is imperative to take the lessons learned from the 130 Liberty Street tragedy and make sure that they are implemented going forward at that building and at Fiterman Hall and 130 Cedar Street as well.

Unfortunately, our community has already been the target of two terrorist attacks, and if any lesson has been learned, it is that we must prevent a senseless tragedy like this from ever happening again and ensure that the community is protected.

Julie Menin and Catherine McVay Hughes are chairperson and vice-chair of Community Board 1, which includes Ground Zero and the surrounding area.

Â

The Mayor's Legacy: Educational Improvements and Poverty Reduction, Or Bold Budgeting and Economic Development?

What will be Michael Bloomberg's legacy as mayor? Bloomberg has said what he would like it to be - reforming public education in his first term, addressing poverty in his second. But public officials cannot usually control how they are viewed by history, and, while much can happen in the more than three years left to the Bloomberg administration, events over the past few months may wind up helping determine what ultimately will be seen as this mayor's main accomplishments.

What seems likely right now (at least for those of us who pay attention to the city's finances) is that the mayor's legacy will revolve around his bold moves in budgeting - his introduction of a three billion-dollar tax increase in the middle of the fiscal 2003 year, and his unilaterally setting aside $2 billion for a city retirees health fund in 2006 - and in economic development -- his giving of huge subsidies to sports owners and real estate developers, the impacts of which will not be known for decades.

Why Not Poverty?

Mayor Bloomberg appointed a Commission on Economic Opportunity to come up with innovative ideas to address poverty in the city. The commission's initial report is scheduled for release sometime this month.

New data from the United States Census Bureau underscore the potential relevance of Bloomberg's second-term focus on poverty. The city's poverty rate has not changed in the past five years. In Manhattan the earnings of the top fifth of earners ($330,244 on average) are 41 times the earnings of the bottom fifth ($8,019 on average). The Bronx is the poorest urban county in the United States.

Yet some critics now wonder what will come of the mayor's attention. A memo from the leaders of the commission leaked recently to the press suggests that the commission will not be addressing aid to the elderly, the unemployed, the homeless, and those returning from prison.

The implication seems to be that the resources simply are not there to tackle the problems of all those New Yorkers affected by poverty. Rather, the commission's focus reportedly will be on three groups -- children, young adults, and the working poor. And, if little new city money is invested to fight poverty, management reform is likely to be key. For example, the Times noted that food stamp administration will be important for all three of the groups targeted by the commission. Food stamps are fully funded by the federal government, so any expansion of their use is a cost-free reform for the city.

Food stamp use has increased from about 800,000 at the beginning of the mayor's first term in 2002 to nearly 1.1 million today. But this is far from the nearly 1.5 million receiving them in 1995, even though hundreds of thousands more are eligible and in need. The Times also noted that the mayor in March rejected an expansion of food stamp eligibility to unemployed adults proposed by his own social service agency officials.

Education?

The Bloomberg administration instituted a major restructuring of the city's education bureaucracy in his first term. There is not universal agreement on what this has meant for the education of individual students. In the meantime, the Daily News recently reported that the city's education department issued about $120 million in no-bid contracts last year without public review. According to the News, city comptroller data show that this is ten times the amount of no-bid contracts awarded in 2002. School officials responded that these contracts are a only a small fraction of the $3 billion in education contracts, and that such contracts are used only under time constraints, for limited extensions, or for specialized companies.

But the more important point here is that education contracting does not follow the same rules as does other city agency contracting. The schools' deputy chancellor for finance and administration said to the News, "We all work for the mayor.But in terms of actually what this entity is, it's not a city agency." This "entity" follows state, not city contracting rules. This means the city comptroller, who oversees the city's contracting process, has limited powers over the new department of education.

The city comptroller does have audit oversight of the education department, though, and his June audit in one area of contracting - job order contracts that involve expeditious maintenance, repairs, and minor construction work in schools - found "significant weaknesses" in the department's administration of this program, including incomplete work, unsatisfactory work, and failure to meet deadlines. The audit made 24 recommendations for improvement.

Economic Development

Much of the Bloomberg administration's economic development plans have focused on subsidizing stadiums for sports teams - the Jets football team, the Yankees and Mets baseball teams, the Nets basketball team. The stadium for the Jets is a broken dream. The ones for the Yankees and the Mets are being fulfilled, though critics grumble. (It's an interesting sidelight to the story that a report by the city comptroller found the Yankees more than a quarter of a million dollars in arrears in payment to the city for its use of the current city-owned stadium.) The arena for the Nets is a dream not yet realized that critics are broadcasting as a nightmare.

The Forest City Ratner basketball arena and commercial development plan in Brooklyn - controlled by the state's Empire State Development Corporation -- was challenged at a raucous hearing by neighborhood advocates who attacked the size and location of the project. Shortly afterward, the developer reportedly planned to reduce the size of the project; this apparently won over few critics.

Another big development plan faced a new roadblock during the summer. The city's offer to buy the development rights to the MTA's West Side railyards for $500 million will have to overcome a new appraisal that says it's worth $1.5 billion.

On the other hand, the NYC Industrial Development Agency's August 3 hearing on the proposed tax breaks for future West Side Hudson Yards commercial developers (discussed in my August finance column) was followed quickly on August 8 by the agency's approval of the proposal. This deal -- rushed to judgment before the Independent Budget Office or other fiscal monitor could confirm or question the assumptions and fiscal projections - could result in a loss of more than a third of the future property taxes from the area over the next 30 years.

Will these tax breaks stimulate development and wind up generating more revenue for the city? This is what the Bloomberg administration hopes will be part of its legacy.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Hanging Out and Hurting Business

Paros Apostolopoulos, an employee at a pastry restaurant on Third Avenue in Bay Ridge Brooklyn, is used to hearing customers complain about teenagers who hang out in and around his shop.

“One time I had a table at the restaurant next door kids were so loud and the language so bad that the older couple just left. It could be nice if they had something else to do, some activities,” said Apostolopoulos, who has worked at the restaurant for two years.

Parents ask restaurant employees not to not to allow their children to be at the restaurant when they should be in school. But Apostolopoulos and other owners and workers at businesses along Third Avenue worry mainly that the young people will drive away other customers and hurt business.

Their concern is shared by establishments on Bay Ridge’s other commercial strip -- 13th avenue from 69th to 78th streets – and by stores and restaurants around the city. The issue has been discussed by Brooklyn’s Community Board 10, which includes part of Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights and Fort Hamilton. Regardless of whether the young people have a right to hang out, their presence can create a problem for businesses.

|

Conflicts and Resolutions Police in the Schools: Hanging Out and Hurting Business: Breaking the Cycle of Violence: Taking A.C.T.I.O.N. at The Point: Cutbacks After School: |

“We get complaints about large groups of kids hanging out on the commercial strips,” said Josephine Beckmann, district manager for Community Board 10. “The complaints range from late night noise to acts of vandalism like graffiti.”

Ada Lin, an employee at Fujiyama Japanese restaurant on 73rd Street, said kids as young as 13 years old hang out in front of their store after school hours. Once, the owner called the police because he was worried that the young people might keep customers away.

“They treat the restaurant as a playground,” she said. “I don’t think there is another place that has more kids. But if they had more stuff to do, like activities for kids, I think they wouldn’t hang out here.”

Later at night, Rosa Pizzeria on the 13th Avenue stretch becomes a favorite and popular place for teenagers. Although this does not bother the employees, residents complain about the noise.

Brooklyn Community Board 10 has tried to find way to keep the teenagers occupied with age-appropriate activities. Beckmann said that the district has a program for middle school students that is open three times a week.

However, an afterschool program (see related story) aimed largely at younger students, at PS 170, faces cutbacks. Because of reductions in funding, the program which serves 220 youngsters, will have to reduce its slots for 60 to 80 youngsters, according to Christie Hodgkins, director of after-school services at CAMBA, which runs the program. In addition, a movie theater and bowling alley in the neighborhood have closed.

In response, the community board has voted to ask the parks department to allow teens to use two neighborhood parks with supervision at night “These programs are really needed in the district and in the neighborhoods since kids are looking for activities,” Beckmann said.

Â

Stated Meeting: Cell Phones, Yes, Markers, No

In muted gesture of defiance of the Bloomberg administration, the City Council last week approved legislation guaranteeing a student's right to take a cell phone to and from school, despite a Department of Education ban on the devices inside school property.

The legislation, however, does not address what occurs inside schools. And despite its overwhelming approval, many question whether the bill will have any effect on the department's policy.

At its stated meeting on July 25, the council also targeted graffiti by restricting the possession of certain markers, etching acid and spray paint and approved several bills that continue the effort to modernize the city's building codes.

A Call for Safety

The overwhelming approval of the cell phone bill (Intro 351) comes after more than a year of hearings and complaints from parents about cell phone confiscations. Under current policy, if a student is found with a cell phone, school officials will take it and return it only to a parent or guardian.

It remains unclear whether the legislation, sponsored by 39 members and spearheaded by Councilmember Lewis Fidler, would change that. The bill may guarantee students' rights to carry a cell phone while en route to school, which they can already do under the current law.

The cell phone frenzy was ignited not when the ban was initially approved, but when the department began enforcing the long-standing rule in 2006. In light of a new security initiative, the city started conducting random screenings at middle and high schools. While searching for weapons, they found the most popular contraband was none other than a cell phone.

School officials contend that cell phones in classrooms can be used to cheat on tests and otherwise serve as a distraction. Following the council vote, the Department of Education released the following statement: "Our policy prohibiting cell phones in schools has not changed. Whether used for talking, messaging, surfing the Web, or taking photos, cell phones inevitably disrupt a school's learning environment."

The legislation is likely to set up a confrontation between the mayor and the council, because Bloomberg is a staunch supporter of the cell phone ban and plans to veto the legislation. That could bring about the sixth veto override in Council Speaker Christine Quinn's tenure.

"The City Council does not have the authority to even pass the law that would change how we do things in the schools," Bloomberg told The Post. "So this doesn't really change anything."

The Bloomberg administration and the City Council have clashed repeatedly over oversight and power sharing in the city's school system since the mayor took over in 2002.

The legislation was approved by a vote of 46 to 2 with council members G. Oliver Koppell and James Sanders dissenting. In supporting the bill, Councilmember Peter Vallone said, "It is not an education issue. It is a public safety issue."

The department's cell phone policy recently landed in court when a group of parents also claimed the prohibition of cell phones in schools was a public safety concern. The state Supreme Court disagreed and upheld the ban. The parents are reportedly appealing the decision.

Vallone said the council's action could bolster the parents’ position in court because it states that any person prevented from carrying a cell phone to and from school "shall be entitled to seek equitable relief in any court of competent jurisdiction."

As for compliance, Quinn said the issue now rests with the Department of Education. "Yes, they can say no cell phones in the classroom. They can say cell phones shouldn't be on in the classroom," Quinn said. "This bill puts an onus on the Department of Education to make sure that children can have cell phones coming to and from school."

The legislation's approval also comes as the Department of Education prepares to launch a pilot program that would install lockers outside of about 16 schools in the city specifically for storage of cell phones.

Can I See Your ID?

In an effort to suppress graffiti, the council also passed a bill (Intro 576) prohibiting the sale of etching acid (or hydrogen fluoride), broad tipped indelible markers or cans of spray paint to people under 21 years old.

Similar legislation was approved in 2005, but several artists, who contended it violated their first amendment and equal protection rights, successfully challenged it in court.

To try to address the court's concerns, the new legislation, which was sponsored by Vallone and passed by a vote of 46 to 1 with council members Alan Gerson dissenting and Melissa Mark Viverito abstaining, includes several exemptions. People can possess the substances if the tools are used for educational or professional purposes, if they are locked in a sealed container or if the individual has consent from the property owner where the substance is possessed or used.

Building a Better Building's Department

As part of the continuous modernization of the convoluted and confusing code of the city's Department of Buildings, the council approved several bills that create better administrative oversight and include broader safety measures for construction in the city.

The bills, all of which were approved 48 to 0, require general contractors for one, two and three-family homes to register with the department, impose civil and criminal penalties for the illegal conversion of manufacturing buildings to residential use and implement a staggered timetable for building façade inspections.

Currently, according to the bill's (Intro 33) sponsor, James Oddo, the city does not regulate or calculate the amount of single, two or three family homes being constructed in the five boroughs. Under this legislation, contractors would be required to submit information to the buildings department, including their chief officers as well as proof of insurance.

The department will electronically publish the information and include suspensions or revoked registrations that the contractor has incurred, thus warning individuals of contractors who habitually violate the city's construction code.

The illegal conversion of warehouses to lofts is common in areas of the city, like Williamsburg.

The death of firefighter Daniel Pujdak, who fell from an illegally converted warehouse during a fire in Brooklyn last month, focused the city's attention on the hazardous conditions of these conversions. In addition to safety concerns, the conversion of certain buildings to residential use depletes the availability of industrial space, which eventually drives up costs for the manufacturing sector, council members contend.

"We are facing terrible times in the arena of industry, where there was industrial and manufacturing space at one time is no longer the case," said Councilmember Diana Reyna, the bill's main sponsor. "To replace all of the square footage we have lost, it would cost $100 million."

Under the legislation (Intro 34), an individual who illegally converts such a space could be subject to a year in prison and up to $5,000 for the first offense. For subsequent offenses within 18 months, an individual could pay up to $20,000 per conversion.

The council also approved legislation (Intro 550) introduced by Councilmember Daniel Garodnick, which staggers the time of inspections for building facades six stories tall or higher. The mandatory inspections currently are conducted in mass once every five years. Staggering the inspections, would allow engineers and architects to better manage the workload.

Zoning for Preservation

The council also approved rezoning in several neighborhoods, specifically 99 blocks in Fort Greene and Clinton Hill in Brooklyn, 159 blocks in Dyker Heights and Fort Hamilton also in Brooklyn and 64 full blocks and 70 partial in the Bronx neighborhoods of Wakefield and Eastchester. The zoning, which passed by a vote of 48 to 0, attempts to preserve the character of these neighborhoods and protect against overdevelopment.

Bloomberg commended the rezoning approvals for keeping within the sustainability goals of PlaNYC. "Specifically, these plans will catalyze growth on key corridors near transit hubs, fostering nearly 900 units of new housing and strengthening local retail activity," the mayor said in a statement. "At the same time, they protect the scale and character of these lower density neighborhoods."

In response to the mega-development Atlantic Yards, part of the rezoning addresses preserving the commercial corridors of Atlantic Avenue and Fulton Street, but also keeps nearby areas of low-rise and historic residential rowhouses intact. The rezoning, according to Councilmember Letitia James, will ensure historic residential properties do not immediately abut gargantuan developments.

Historic Crown Heights

The council also approved a historic district for the North Crown Heights area of Brooklyn by a vote of 48 to 0.The blocks feature Neo-Grec-style homes and Romanesque Revival residences. The designation will help preserve the architectural style of the residences dating back to the 1860s.

Â

Mixed News in a 'Good News' Budget

The city’s $59 billion FY 2008 budget is a remarkable document: full of good news for city property owners, bad news for renters, discouraging news for those hoping for real tax reform and uncertain news for long-term budget stability. Given the nearly $6 billion in extra tax revenues and other resources that became available in fiscal 2007, there should have been more good news to spread around.

Ironically, the huge city surplus may have served to further erode the City Council’s role in the budget process. Much of the extra revenues generated in 2007 went to pre-pay billions of dollars in debt service that are not due until 2008, 2009 or 2010. These one-time payments left little money for expanding social services and other government program.

Much of the rest of the money went to a narrowly targeted property-tax cut. Because the 2007 surplus had grown since April’s executive budget, the mayor and City Council at the last minute decided cut the property tax rate more than originally planned -- upping the reductions in the average property tax rate for residential and commercial property owners from 5 percent to 7 percent.

That will cost the city an additional $300 million, bringing the total expense of the cut to $1.05 billion in 2008 -- and more in subsequent years. In addition, the mayor and council extended the $400 rebate for homeowners, costing more than $250 million. They also eliminated the city sales tax on all clothing -- not just items priced at less than $110 as had previously been the case -- at a cost of $110 million.

WHAT THE BUDGET DIDN’T DO

The mayor rejected the council’s proposal for a modest $300 tax rebate for the two thirds of New Yorkers who are renters, a cut that would have cost $261 million. The plan would have been a small step toward reversing the burden that the last 25 years of property tax politics have placed on renters. For instance, according to an Independent Budget Office report, the median household income of renters in 2005 was $33,904 -- just over half the median income of $66,000 for people who own their homes.

Ironically, even for homeowners the property tax relief may not be everything its supporters would have liked. Press coverage showed that most, if not all, residential owners will still pay more in property taxes in 2008 than in 2007. The confusion stems from the bizarre assessment structure of the city’s property tax system, detailed in the Independent Budget Office report.

The budget also missed an opportunity to help low-income New Yorkers, either with substantial new services or a break in their income taxes. The budget does include a modest child-care credit. But the Independent Budget Office points out that some 167,000 low-income New Yorkers will still pay the city income tax, although they pay no state or federal income taxes. Some 94 percent of these taxpayers have household incomes between $20,000 and $50,000, with most in the $20,000 to $30,000 range.

And, for all the cooperation between the City Council and the mayor the past year, the council seems to have gained little more than in previous years. It again had to focus on “restorations” of council programs cut by the mayor in the executive budget ($266 million this year). Yes, a few programs were “base-lined” into the mayor’s four-year plan, but the great bulk of this year’s restorations remain subject to mayoral discretion another year.

FUTURE DEFICITS

Much like former Mayor Rudy Giuliani and City Councils in the late 1990s, Bloomberg and the current council continue to ignore long-term budget stability. The pre-payments and property tax cuts in the 2008 budget help create an estimated $3.4 billion deficit in 2010 and a $4.3 billion deficit in 2011.

But, with the term-limited mayor and council leadership leaving office in December 2009, any 2011 deficit will be the responsibility of others.

As the state Financial Control Board has noted in its May 31 report on the executive budget, this year’s big surplus is largely the result of a phenomenal year on Wall Street. In calendar year 2006:

· Security industry profits were $20.9 billion; · Wall Street bonuses were $25.5 billion; and · Capital gains realizations reached $38.9 billion.

These big profits, bonuses and gains brought in an unanticipated $1.9 billion in business income taxes and over $700 million in personal income taxes. In addition, in the booming real estate market, taxes on property transfers and the recording of new mortgages were over $1.4 billion more than projected in June 2006. At the moment, no one thinks these numbers will be repeated next year.

PAST SURPLUSES

But huge budget surpluses are hardly new. Although Rudolph Giuliani had fiscal problems in his first years in office, he later enjoyed successive budget surpluses. For the four fiscal years 1998 through 2001, Giuliani budget surpluses totaled nearly $11 billion, or about $2.7 billion a year:

* FY 1998: $2.1 billion

* FY 1999: $2.6 billion

* FY 2000: $3.2 billion

* FY 2001: $2.95 billion

Each year Giuliani and the council used the one-time surpluses to pre-pay a large part of the following year’s debt service. A 1999 cut in the personal income tax (reversed by Bloomberg in response to the 2002-2003 budget crisis) cost the tax base over $500 million a year.

But the surpluses did not go on indefinitely. Recently Bloomberg has suggested that Giuliani left him with, as the New York Times put it, “a huge budget deficit” when Bloomberg became mayor in January 2002.

Indeed, Giuliani did contribute to Bloomberg’s fiscal problems through his use of one-time surpluses and tax cuts. Giuliani’s last budget used a nearly $3 billion surplus for 2001 to balance 2002’s budget. That left Bloomberg vulnerable to the terrible human, economic and fiscal impact of events in the next year: a growing national recession and, of course, the effects of the September 11, 2001, attacks.

For the last four Bloomberg fiscal years, budget surpluses -- using Bloomberg’s definition of “surplus” -- have totaled about $14 billion, or $3.5 billion a year, according to the office of the city comptroller and the city Office of Management and Budget.

* FY 2004: $1.9 billion

* FY 2005: $3.5 billion

* FY 2006: $3.8 billion

* FY 2007: $4.7 billion

Bloomberg, like Giuliani, has used each year’s surplus to pre-pay large parts of future debt service. Unlike his predecessor, Bloomberg has spread the pre-payments over two future years (and, as noted above, a third year in the 2008-2011 financial plan). Another difference is that Bloomberg’s tax cuts are considerably larger than Giuliani’s, reducing the city tax base by $1.3 billion dollars in 2008 alone.

By some calculations, Bloomberg’s surpluses are actually even higher than he says they are. He does not count the $1 billion used to fund a new retiree health benefits trust and the $1.25 billion used late in 2007 to retire debt early as “surpluses.”

If those two actions are included, the Bloomberg surpluses are $4.75 billion in 2006 and $5.9 billion in 2007 -- or 12.5 percent and 14 percent of city funds.

MODIFYING’ THE BUDGET

This means that a substantial chunk of the budget-- as much as 14 percent -- is not subject to the May-June budget process. The mayor decides to spend these surpluses throughout the fiscal year. Although the City Council technically must approve his decisions, the councils in both the Giuliani and Bloomberg eras have been reluctant to challenge the mayors’ decisions.

By state law the city must spend any surplus before the next budget begins. In an effort to do that and still safeguard the city against further fiscal crises, Bloomberg put aside, or saved, $2 billion through the retiree health benefit fund in 2006 and 2007. Another $500 million will go there in 2008. Fiscal monitors applaud those moves, but the mayor rejected the City Council’s effort this year to create a real rainy day fund, which would give the legislative body some say in how surplus funds are spent.

Bloomberg’s surplus strategy is essentially quite conservative -- at least politically -- in two senses. First, using the surplus to prepay debt service means the money will not be available for human services of equivalent value. Second, the mayor’s tax cutting strategy benefits big firms and higher-income New Yorkers much more than low- or middle-income New Yorkers. At the same time, the failure to solve long-term budget deficits means the strategy ignores a conservative fiscal goal of setting the structure for balanced budgets in years to come.

A structurally balanced budget requires a long-term, consistent, and adequate tax base that matches long-term projected expenses. A progressive budget ensures that the tax burden is fairly distributed and that expenses provide comprehensive public services. The 2008 adopted budget is neither structurally balanced nor progressive.

The huge surpluses -- and the inability of a Democratic council to play a countervailing role in the political and fiscal decisions about how to use the money -- suggest that both term-limited mayors found and used a structural weakness in the city’s budget process. Giuliani’s decisions contributed to a monster fiscal crisis within a year of his leaving office. The city can only hope that Bloomberg’s successor has better luck.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.

"Imperfect" Campaign Finance Bill Wins Approval

The City Council overwhelmingly passed sweeping changes in the city's campaign finance system, despite reservations by several council members on the bill's approach to public financing and its exclusion of unions from the caps on campaign contributions. At its stated meeting June 27, the council also approved an overhaul of the city's building code, an exemption for small business establishments from billiards regulations and a measure more strictly regulating the placement of clothing bins on public and private property.

Counting the Cash in City Campaign Finance

The City Council's campaign finance bill attempts to put more emphasis on smaller donations by broadening a ban on contributions from corporations to include limited liability companies and partnerships and by reducing caps on campaign contributions from those that do business with the city by 90 percent.

The legislation was approved by a vote of 44 to 4 with council members Erik Dilan, Vincent Ignizio, Oliver Koppell and James Oddo dissenting.

Under the bill those that "do business" with the city include lobbyists, city contract holders, land use applicants and economic development recipients. But, much to the dismay of some advocacy groups and council members, the legislation does not include unions.

Calling the bill (Intro 586) the "gold standard of good government," Council Speaker Christine Quinn defended its exclusion of unions. "The situation here is to require that everyone gets treated the same way," Quinn said, contending that the limits on individual contributions create equality.

But not everyone agreed.

"It's not what's in the bill," said Councilmember Ignizio. "It's what's not in the bill. The fact that we are leaving out interest groups, unions in this particular case, at the expense of the rest of the city is questionable at best. I believe we have to treat all three groups equally."

The legislation, which was also spearheaded by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, increases the public matching contribution from $4 for every dollar in the first $250 of a contribution to $6 for every dollar for contributions of $175 and below. The contribution limits on city contractors range from $250 for gifts to City Council candidates to $400 for those seeking citywide office. Those contributions also will not qualify for public matching funds. The individual contribution caps will continue to range from $2,750 to $4,950.

Supporters of the legislation argue that by increasing the public matching funds and greatly limiting contributions for those that do business with the city, the bill will empower average citizens and sharply curtail the supposed influence of special interests eyeing lucrative city contracts.

According to the legislation, the city will also study whether donations from family members of city contractors should also be included within the contribution limits. Currently, Quinn said, the state prohibits the solicitation of such personal information from city contractors.

The legislation also does not apply to providers of affordable housing or to contributors whose name is accompanied by a professional designation, such as Esq. or C.P.A., who might otherwise be interpreted as a limited liability company.

While some council members objected to the bill's treatment of unions, others contended that the contribution limitations could favor rich candidates who can finance their own campaigns and hurt efforts by politicians in poorer communities to gain financial support.

"In order for a campaign finance system to work it has to facilitate realistic campaigns," said Koppell prior to the council's vote, "This proposal unfortunately is unfair. It's unfair to candidates, especially to candidates from poor or minority districts who will find it very difficult to raise enough money to run, especially for races beyond the City Council race."

Several members who voiced opposition but still supported the measure, pointed to a discussion on the legislation's imperfect approach to campaign finance. Councilmember Simcha Felder, a sponsor of the bill, said, "The bill's not perfect. I don't think anything is perfect."

Even so, the city's good government groups support the sweeping reforms, which will take effect in intervals and are all intended to apply to the next citywide election in 2009.

Modernizing the Building Code

Nearly four decades since its inception, the city's building code has itself become dilapidated, city officials said.

Like bad plumbing or broken windows, the code was widely thought to be in need of an overhaul - a long-awaited rehabilitation that was approved, nearly unanimously, by the City Council last week. The code (Intro 578) was supported by 47 council members with one abstention by the Bronx's Koppell.

Following 9/11 -when officials recognized that small stairwells in skyscrapers could become a safety hazard - the Bloomberg administration and the City Council set out to revamp the city's construction code. The new code is a product of a commission formed by the Bloomberg administration in November 2002, which was charged with reviewing and reforming what was known as an "antiquated" set of regulations.

The code now incorporates national and international standards for new construction and mandates the installation of sprinkler systems for all residential buildings with three or more apartments and for one to two-family homes over three stories.

The new code, which takes effect in July 2008 and applies to new construction, also requires buildings over 125 feet to have a back-up generator for emergency lighting as well as at least one elevator in case of an emergency. It also classifies student dormitories as hotels to ensure devices, such as sprinklers and fire alarm systems, are incorporated into the building.

The bill included a mandatory three-year review of the building code to guarantee it is kept up to date.

"The code, because it's updated every three years, will kind of be a living, breathing document," said Dilan, the chair of the Housing and Buildings Committee. "It's not a perfect document… It's a long, complicated, technical bill."

In addition to stricter safety requirements, the new building code also offers incentives for environmentally friendly construction. It hands out rebates for projects that abide by the United States Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design rating system for renewable energy, energy use reduction and bicycle storage facilities, among other green building elements.

Some real estate and building professionals have raised concerns that the new code would drastically raise the cost of construction. But, city officials said, a hike in cost initially could save more in the end through the elimination of redundancies in the code and including more energy efficient products.

Billiards Exemption

City Council unanimously approved a bill (Intro 577) so that bars and restaurants with less than three pool tables will not have to seek a billiard's license from the city. Introduced by Councilmember Leroy Comrie, the bill does away with a bureaucratic procedure and eliminates a burden on small businesses, officials said.

"This is a silly law and it doesn't need to be regulated," said Comrie. "This gives our business people one less onerous burden that they have to hurdle in order to do business in the city."

Illegal Clothing Bins

The council also approved legislation that gives the Department of Sanitation greater power to control the condition and location of clothing collection bins. Some council members defined the bins as an intrusion on public sidewalks, an eyesore and hub of graffiti.

The council approved the bill, (Intro 105), which would allow the Department of Sanitation to remove the containers if they do not comply with city regulations, by a vote of 47 to 1, with Councilmember Inez Dickens dissenting.

"The situation that we look at now is clothing bins that are popping up, as I like to say, like wild mushrooms in a rainy forest in the mid-summer," said Councilmember Michael McMahon, the chair of the Sanitation Committee "As you can see this a problem. It becomes a fungus in our community."

The bins will be prohibited on public property, and the owners of the bin will have to obtain permission to place a bin on private property. The legislation will require contact information be displayed on the bin and that it be kept clean.

Â

Dividing the Wealth: Who Gets the Council's Discretionary Funds?

Many of David Weprin's constituents would undoubtedly like to pat him on the back. By one measure, the mustachioed councilmember from Queens gained more funding for individually sponsored projects and initiatives than any of his 50 council colleagues, corralling more than $735,000 for nonprofits and community-driven organizations.

Gotham Gazette’s analysis of the City Council's so-called "pork-barrel" spending -- officially known as the member items list -- also found that newer members of the council, such as Mathieu Eugene and Darlene Mealy, both of Brooklyn, got far less funding for their individual initiatives.