In Albany, Budget Battles Behind Closed Doors

Gotham Gazette image by Ya-Hsuan Huang

State Republicans said it would happen under the cover of night with little to no warning. Good government advocates said legislators would be ordered to their chambers and reminded there is no time to waste. Printers would roar to life, packets of hot paper would be distributed and in a blink of an eye, groggy legislators would vote to approve New York State's 2009-2010 budget.

To a great extent, the cynics were correct. The legislature and the governor did agree on a budget deal behind closed doors -- over the weekend and late at night. The documents were printed over the weekend. It now appears, though, that members of the Assembly and Senate who are so inclined will have a few days to read the nine bills, some with thousands of pages, before the expected vote early this week. Nevertheless observers reviewing recent events still say the budget process this year has been one of the most secretive negotiations in recent memory. (Gotham Gazette will continue to cover the budget throughout the week in Eye on Albany and The Wonkster.)

New York State faces a $16 billion budget gap and by law must pass a balanced budget by Wednesday. As the clock ticked down last week, about all one heard in the Capitol were rumors. At a recent negotiating session with the three men in a room (otherwise known as the governor, Assembly speaker and Senate majority leader) a reporter asked Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver for one detail about what is actually in the budget. Silver replied, "We'll have an on-time budget."

At first, it seemed things might be different this year. Gov. David Paterson started talking about the state's perilous finances months ago, warning that the state would have to make "draconian" cuts. Paterson even released his budget proposal in December -- earlier than most governors have done -- and used his State of the State address to hammer home the need for fiscal responsibility and shared sacrifice.

All three Democratic leaders have, at one point or another, pledged to reform Albany and ensure state government would be more transparent. The Senate Democrats started a Web page and a hot line to take budget suggestions from the public.

Now, though according to Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group, the leaders seem to have gambled that an "on-time budget" means more to voters than "transparency." Instead of openness, the three Democratic leaders hammered out the budget in closed-door sessions with limited, if any, input from Republican leaders.

"Talk is cheap," said Horner. "Reality is hard."

Crafting a Budget

New York State's budget process in kicked off when the governor introduces a budget proposal in January. The legislature's financial committees then hold hearings to review the soundness of the governor's plan.

According to the New York State Department of Budget Web site, "the legislature, primarily through its fiscal committees -- Senate Finance and Assembly Ways and Means -- analyzes the governor's spending proposals and revenue estimates, holds public hearings on major programs, and seeks further information from the Division of the Budget and other state agencies."

In most years, both houses of the legislature would pass separate budget bills, and then, since 2007, they would hold conference committees to discuss differences between their separate budget bills -- an attempt to clarify the process. "Under budget reform legislation passed in 2007, the legislature is required to use a conference committee process between the two houses to organize its deliberations, set priorities and reach agreement on a budget," the Division of Budget Web site says.

The legislature held hearings on Paterson's proposed budget earlier this year, but so far the leaders have chosen not to hold another round of conference committees.

The Quiet Before the Storm

No one doubts the state faces a dire budget situation. Up until the last minute, though, it was hard to detect that from the scene in the Capitol. Last week, normally talkative Democrats scuttled away from reporters who had questions about the budget on their lips. Near the Senate chamber Sen. Eric Schneiderman blurted to a reporter, "What do you want from me?" The reporter shot back, "I want answers!"

In all fairness, Schneiderman might not have had the answers since the three men in the room stingily parceled out information. As the negotiations dragged on, legislators who were told about parts of the deal dished out tidbits on what they thought might be in place but warned that things were steadily shifting.

Legislative action in the Senate slowed to a crawl in recent weeks as the focus shifted to the budget deal. The Senate spent the last few weeks honoring citizens and commending the recently deceased rather than passing substantive bills. Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith, when asked about serious pieces of legislation, repeatedly said they will be addressed "after the budget."

The Assembly, thanks to a Democratic supermajority, moved quickly on again approving bills that it had passed in previous years, bills addressing issues like Rockefeller Drug Law reform and rent control. However, the members hesitated to consider new legislation knowing that their action would be futile without support from the Senate. Silver did not act to pass his compromise plan to address the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's financial straits, nor did his house vote on an income tax increase for the wealthy, a measure that is now in the budget bill.

Hopes for Transparency

Advocates of open government initially thought they had allies in the Democratic leadership. Paterson, for example, had made a number of comments about his commitment to ending the secretive budget practices, which long plagued Albany.

Advocates had solidified relationships with the new majority after years when Senate Democrats -- then in the minority -- struggled to gain a seat at the table and to have their input taken seriously. At the same time, good government groups pushed to make the budget process more open.

Much, though, has changed since then -- as evidenced in the Democrat's new attitude toward the budget conference committees.

The 2007 law that created the committees was passed when the Republicans controlled the Senate and Democrats controlled the Assembly.

And Silver signed on. In a 2007 press release now being distributed by Republicans, the speaker said that conference committees would "move our state's budget process in the 21st century with a strong constitutional emphasis on mutual respect between the executive and legislative branches in forging a fiscal plan for our state. We will continue to rely upon the joint conference committees. We will have a more transparent, more easily understood budget process."

This year, with Democrats controlling both houses, Silver said there is no need for conference committees. "We're all Democrats," he said. "We're not going to have big philosophical differences."

Republican Minority leader Dean Skelos has said that not holding conference committees is illegal. But Silver has repeatedly declared that, if there are no differences between the budget bills in the two houses, there is nothing to be discussed in conference committees. In fact, Silver has said, there might not even be separate Assembly and Senate budget bills. For his part, Smith repeatedly insisted that he would hold conference committees. But as of Sunday night, with the budget apparently all but certain, that had not happened.

Those who observed conference committees in previous years point out that they were heavily scripted and did not actually produce more open government. Legislators would use the meetings to give speeches and hold their substantive discussions in private. By doing away with the committees and one-house budget bills, however, Silver is admitting that they were only window dressing on an ugly budget process -- just another way to placate the public.

Barbara Bartoletti of the League of Women Voters noted that the legislature fought to amend the budget process under Gov. George Pataki because he kept the budget process notoriously secretive. "It was known as Fort Pataki," she said.

According to Bartoletti, Gov. Eliot Spitzer made it a priority to open up the process and now Paterson, Smith and Silver are disregarding that work.

"This is a blatant violation of the law they passed in 2007!" said Bartoletti. "If regular people violate the law they get in trouble, but apparently these guys think they are above the law."

At a briefing Friday, reporters asked Paterson about the lack of transparency in the budget process. "I think there should be transparency in terms of the process and openness in terms of government," Paterson responded. "However, when you are in a budget position, it is very hard to negotiate in public. You never see President Obama and Senator Reid and Speaker Pelosi do it. You don't see it in any other state." And Paterson continued, "You don't see it in labor negotiations and I dare say that your negotiations with your own media outlet, your contract, is not, the last I checked, publicly observed."

Paterson failed to mention that his salary is paid by the taxpayers and reporters' salaries are not.

"There comes a point in the negotiations," continued Paterson, "where anyone who is really negotiating has to take things off the table. This is a very difficult endeavor, and it's hard to do it when the advocates you are fighting for are right there."

New Leaders, Old Habits

Silver, of course, is the only leader remaining from 2007. This year's budget negotiations took place with two new leaders -- Paterson and Smith, both of whom are considered weak and vulnerable. Smith has been rendered powerless by the combination of a slim majority and indecisive behavior. Paterson, thanks to plummeting poll numbers and his own brand of indecision is seen by many as nearly "irrelevant."

Smith and Paterson apparently hope that an on-time budget, no matter what it contains -- or how it's drafted -- will make them look responsible to the public and give them a political boost.

In addition, the lack of transparency might have helped Smith move things into the budget that would be controversial to some members. His majority is so slim that he can't afford "no" votes from any Democrats. That is why instead of passing legislation on drug law reform Smith has included it as part of the budget negotiations.

"The thinking on this issue is that there is an explicit rush to get this through," said Robert Gangi, the executive director of the Correctional Association of New York State. They wanted to have it included as part of the budget so that neither side can cherry pick. They have to vote up or down for the whole kit and caboodle."

The three announced they had reached a deal on drug reforms on Friday but did not offer a detailed account of what was agreed on.

Health care advocates have spent the last week using advertisements to target individual legislators and alert citizens about what they think will be tremendous cuts to health care funding and Medicaid payments to hospitals.

William Van Slyke from the Healthcare Association of New York, which represents health care networks and hospitals, thinks it is important to make sure legislators and voters know exactly what kinds of cuts are being considered. But he said last week, "Rank and file legislators don't even know what is in the budget. The Senate is in disarray."

For a week, information about "tentative" deals made its way around the Capitol before quickly being denounced or refuted by one of the three men in the room. Silver flatly denied a New York Times report that a deal on drug law reform had been reached, only to hold a meeting to announce the deal the next morning.

There was talk that a deal had been reached to institute the Bigger Better Bottle Bill, which would have put a deposit fee on noncarbonated beverages like water and tea and made beverage companies give the state unclaimed deposits. But it was reported quickly thereafter that the tentative deal had fallen apart. The bill is now back in as part of the budget deal, but only with deposits on water -- not juice or tea.

Bartoletti said there are many advantages for the three men in a room to keep the deal hush-hush as long as they possibly can. "Special interests still run Albany. It was probably lobbying or campaign contributions that killed the bottle deal but we won't know for two months till we see the contributions," she said before word came that parts of the bottle bill were back in. "It is the same thing with healthcare: We don't know because it is behind closed doors and special interests have their influence."

According to Horner, the budget crunch provides another convenient excuse to do business in secret. "This is unlike any other year," he said. "Thanks to the federal stimulus, the budget the governor presented is being entirely reworked, and it is being reworked behind closed doors."

"They are going to get away with it this year," said Bartoletti. "They think the public has a short memory and they will say they did it because of the financial crisis. They will even come out and say this was a bad process this year but we had to do it and we will do it better next year."

Opaque Government

Bartoletti describes this year's budget process as a "drive-by negotiation," because legislators driving away from leaders' meetings at the governor's mansion sometimes had the decency to pause briefly to give reporters placating, dismissive answers about what was discussed -- or, in the case of Republican leaders, to complain about how little input they actually have.

Last Tuesday, March 24, Republican legislators and open government groups stood together in the same room to call for Democrats to make the process more open. Skelos said he had not been invited to attend the "secret leaders meeting" that was going on just one floor below among the three Democratic leaders.

He said he thought Democrats would probably rush the budget through by issuing a so-called "message of necessity" that would eliminate the three-day waiting period normally required before the legislature votes on a bill. This would ensure, of course, that even fewer senators and Assembly members would have any idea about what's in the spending plan.

"Under the guise of getting a budget done on time, Governor Paterson, Senator Smith and Speaker Silver are prepared to rush through a budget in the dead of night with no time for public input or examination," said Skelos in a written statement.

Bartoletti expected that "legislators won't see the budget until 15 minutes before they vote and no one will even know what's in it." It was not quite that dire: Legislators will have part of the weekend and two days to review the bills. And, of course, getting bills on short notice is nothing unusual in Albany. Longtime Democratic Sen. Neil Breslin said he has "gotten bills two minutes before" he voted on them.

Last Tuesday, Smith canceled a number of public appearances to attend "budget negotiations." Meanwhile, the three leaders released a statement saying the budget deficit had increased by $2 billion to $16 billion. Republicans said the announcement was just cover for an impending announcement of a tax increase. Then news broke that Paterson had ordered the layoff of 8,900 state workers. The big three were nowhere to be seen.

At 3 p.m., school children in white shirts observed a poorly attended session of the Senate. The Senate asked the children to stand to be recognized, and then the few legislators in attendance voted to honor a recently deceased labor leader and tabled legislation pertaining to warning lights on bicycles. When the end of the session was called, a young girl looked up incredulously and said, "We came all the way for this? That's it?"

Taxing the Rich: An Idea Whose Time Has Come?

Photo from the Library of Congress

Henry Clews, a wealthy Wall Street financier and economic consultant, in 1910

Since the economic collapse in the fall, Americans have acquired a taste for watching CEOs squirm. They lapped up the scenes of executive sweating before Congress while being grilled about multimillion dollar bonuses and cheered in knowing their outrage had forced the heads of the major American car companies to abandon their private jets and drive to D.C. for congressional hearings. There's even a Brooklyn artist, Geoffrey Raymond who takes his portraits of CEOs to Wall Street to let passersby scrawl nasty messages on them.

So, not surprisingly, polls suggests that raising the income tax on the wealthy, popularly known as a Millionaires Tax, has strong support. Quinnipiac polls have found a steady 80 percent of New Yorkers in favor of such a tax hike. Labor and education groups are pushing hard for it using television campaigns and grassroots initiatives. With such strong popular support, a Millionaires Tax seems imminent.

Some legislators seem to have gotten the message. The Assembly is expected to vote to increase the tax on affluent New Yorkers. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has stated that he won't "allow the burden of addressing the economic crisis to fall disproportionately on the backs of our already overburdened working families."

Yet, the plan has not attracted the support of a majority of senators, and despite some indications he might compromise, Gov. David Paterson still officially opposes the tax hike, preferring a mixture of budget cuts, some new taxes and increases in other taxes, such as the sales tax.

Higher and Highest

Although a number of different proposals for a millionaire tax have been discussed the most popular is the Fair Share Tax Bill that has been supported by advocates such as the Working Families Party and put forward in the Senate by Sen. Eric Schneiderman on Feb. 9. The Fair Share Tax Bill would increase the current 6.85 percent income tax rate to 8.25 percent for individuals who make more than $250,000 a year. Those making more than $500,000 a year would see their income tax rise to 8.97 percent, and those making more than a million a year would be taxed 10.3 percent. Currently everyone making over $40,000 a year -- from a schoolteacher to Michael Bloomberg -- pays the same 6.85 percent income tax rate.

Schneiderman's proposal was co-sponsored by 18 other senators. However, Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith opposes raising the tax rate for the wealthy. Smith, who previously called the measure a "last resort," said he believes such a tax would drive more affluent residents out of the state.

"During difficult economic times the senator is not in favor of raising taxes as a revenue generator," Smith's spokesperson, Austin Shafran, said. He added, however, that since there is support for the measure in the Democratic caucus, Smith will not stifle debate of the issue. "This fair share tax proposal will be openly and honestly debated on the floor of the Senate," he said.

Paterson has echoed Smith's sentiments, agreeing that a tax increase on the rich would be a "last resort." But with flagging poll numbers and public opinion heavily in favor of such a tax, spectators wonder if Paterson is wavering on the issue. At a banquet hosted by the State Association of Black and Puerto Rican Legislators last week Paterson said, "To those of you who are not here, who think you are too wealthy or too influential or have too great of a title to be part of New York's budget-balancing formula, let me make you aware that every New Yorker will share in the sacrifice to get this budget balanced." Paterson spokesperson Errol Cockfield reportedly told reporters afterward that Paterson's statement did not reflect a change in position.

Taxing, Not Cutting

Critics of the tax such as E.J. McMahon, director of the Empire Center for New York State Policy, said that unions representing public employees advocate the millionaires tax because they reject what he views as reasonable cuts to address the budget crisis, such as postponing increases in wages or benefits.

"The top one percent paid 40 percent of the taxes in the state in 2007," said McMahon. "People with a pie slice view of the economy think, 'Hey, if we jack up the rate 50 percent the rich won't notice it.' They think, 'Oh they have money! Let's get it.'"

According to McMahon, the state has relied on taxing the wealthy for too long. He noted that the reason there is such a budget gap this year is because the state got a large percent of its revenues from Wall Street and those revenues have plummeted. An increased tax on the rich, who have already lost great amounts of their wealth due to the market crash and who have "volatile" incomes is not a smart way to patch the budget deficit, he said.

Karen Scharff, executive director of Citizen Action, a group that strongly advocated Fair Share Tax Reform, disagreed. "It comes down to whether we should ask wealthy New Yorkers to pay a small amount in additional taxes to protect average New Yorkers facing job losses, foreclosures and school cuts," she said.

Scharff said that if one percent of New Yorkers paid 40 percent of the taxes that's because "they have 40 percent of the income in the state." As she sees it, tax rates on the rich have steadily been reduced for years and a small increase now is "only fair."

Schneiderman said his bill is not simply the product of unions but is supported by a "state wide coalition." He acknowledged that there will have to be cuts in the state budget but called his tax proposal "fair and a good way to raise money." It is time, he said, to stop "redistributing wealth from the working family to the rich," and with President Barack Obama having campaigned on the idea of a progressive tax, Schneiderman said he thought the mood is right to return a progressive tax to New York.

In the end, Scharff said, she expects to see Schneiderman's proposal taken into consideration during budget negotiations between the Senate, the Assembly and the governor. She thinks Smith and Paterson will bow to public pressure on the proposal and will change their stance.

In Schneiderman's view, New York's politicians have a history of "crying wolf" and suggesting cuts before ultimately restoring the spending because of public outcry. He said Paterson has been trying to hammer home the gravity of the situation by stressing the need for major budget reductions, but in the end Schneiderman thinks a tax increase on the wealthy will be part of the solution to New York's $14 billion dollar budget deficit.

The Opposition in the Senate

Given the Democrat's thin majority in the Senate, Smith's position may hinge somewhat on his members. Senators Jeff Klein and Pedro Espada Jr., who represent middle class and working class districts in the Bronx, have stood, along with Smith, in the way of the millionaire's tax as well as rent control laws that would benefit their constituents. "What Smith, Klein and Espada won't acknowledge is the tiny percentage of households in the city that earn $1 million a year, or even $250,000, after taxes," Juan Gonzalez wrote. "State records show a mere 393 households in Smith's Queens senatorial district reported incomes above $250,000 in 2005. More than 93,000, or 99.6 percent, were below that figure."

Scharff said that organizations like hers that helped the Democrats win their majority in the Senate will pay attention to where these senators' allegiances lie. She thinks most voters will pay attention as well. "I find it very puzzling that New Yorkers overwhelmingly voted for Obama and his progressive agenda, they sent a message to politicians and voted for change and yet somehow in New York it feels like we are going backward," she said. "New Yorkers won't allow it."

Creative Ways to Tax and Cut

Gotham Gazette image by Ya-Hsuan Huang

The Independent Budget Office's new Budget Options for New York City is a timely reminder of the many ways a city can balance its budget. As a slumping economy and declining city tax revenues threaten a fiscal crisis in New York, the IBO's eighth edition of its publication is a rich resource for a public debate about how to raise revenues, make spending more productive and set priorities for spending and cutting. Its analyses are comprehensive, impartial and non-ideological.

Budget Options also offers a useful contrast to the more crabbed style of budget presentation in Mayor Michael Bloomberg's recent financial plans. For the past year in particular, the mayor's Office of Management and Budget has provided few budget options, and many of those have been ephemeral. The OMB options, in fact, often look like mere placeholders -- general options with big numbers that are likely to change or be abandoned altogether.

For instance, the mayor's Financial Plan for Fiscal Years 2009-2013 offers only four broad components to fill next year's $4.4 billion deficit, three of which are likely to change dramatically. Yes, some $900 million in savings will come from agency cuts already well under way. But $900 million in sales tax increases, a projected $1 billion savings from labor concessions, additional state aid and a projected $1 billion from federal Medicaid relief represent, at best, fluid estimates.

In contrast, the IBO's Budget Options analyzes 70 ways the city could save money or raise revenues. The range is from the small -- eliminating grass clippings from trash collecting would save $2.1 million a year -- to the very large and controversial -- tolling the East River and Harlem River bridges, an idea once championed by Bloomberg that would raise $830 million a year.

The political range of the IBO's options goes from conservative, such as increasing the work week for city employees by five hours save $129 million, to liberal, such as making the city's personal income tax more progressive, which could raise as much as $455 million. In all cases, the IBO offers arguments both for and against each option.

Another Way to Cut

Because Bloomberg has been making across-the-board agency cuts regularly since fall 2007, usually in mid-year budget modifications rather than during the public spring budget process, the total cuts over that period may surprise many New Yorkers. Since the January 2008 budget modification, the mayor has cut a total of $3.1 billion, or 14.7 percent, from the fiscal year 2010 budget.

The police department has seen an aggregate $391 million cut, or 10.2 percent reduction, since January 2008, and the Department of Education's budget, a $944 million cut or 11.9 percent. Social services, health, youth, aging, parks and homeless services, as well as libraries and cultural institutions, will have taken cuts of 18 to 20 percent over the same period.

The IBO report presents some alternative budget savings. As part of its budget cutback, the police department, for example, planned to delay hiring 1,000 cops, saving approximately $50 million a year.

To avoid cutting the force, one of the IBO options would have police officers work fewer but longer tours, while eliminating 20 minutes of paid "wash up" time and so saving $55 million.

The Department of Education, by far the biggest city agency, will be cut by an additional $306 million (4.1 percent) in 2010 alone. Yet the IBO notes several ways the city could save nearly $300 million. Eliminating public funding for private school student transportation would save $57 million. Increasing the average class size by two students would save $187 million. A four-day workweek for pproximately 40,000 employees would save $33 million

One of the mayor's big budget proposals is the $1 billion savings from restructured contracts with employee unions. As part of that, city workers would pay 10 percent of their health insurance premiums. Most currently pay nothing.

The IBO gives the pros and cons to the proposal. On one hand, proponents argue that it would save the city considerable money every year and reflects current practice in the private sector and increasingly in the public sector. Opponents argue it would burden lower-income employees, with little chance of saving actual health costs.

Raising Revenue

Since the January 2008 Financial Plan, revenue proposals to fill the gap of the 2010 budget deficit have been changing. In January 2008, OMB, looking ahead, projected eliminating the 7 percent property tax rate cut then in place for 2010, while keeping it for fiscal 2009. OMB was warning, 18 months in advance, that there would probably be a tax increase.

As the economy slowed, the mayor shifted gears, and in the November 2008 budget modification proposed eliminating the 7 percent property tax cut earlier -- halfway through the fiscal year, on Jan. 1, 2009. After a brief fight with the City Council, the mayor got his way, although the council refused the mayor's request to cancel the $400 property tax rebate for homeowners.

Moreover, the mayor not only got nearly $600 million of new revenues for fiscal 2009, but the modification eliminated the 7 percent rate cut for the rest of the four-year plan -- as well as eliminating the $400 rebate in future years. That went a long way to fill the 2010 budget deficit -- over $1.2 billion of it. The mid-year tax increases also avoided raising an unpopular tax during the spring of an election year.

The November 2008 budget modification listed two other major revenue options for 2010: increasing sales tax revenues and raising personal income tax rates by either 7.5 or 15 percent. The January 2009 plan drops the income tax option but increases the size of the sales tax option to over $900 million by raising the sales tax rate by a quarter of a percent, extending the tax to more services and items, and dropping the current tax exemption on clothing sales.

In other words, the city's most regressive tax, the sales tax, has become OMB's primary new tax option and somehow increasing the city's most progressive tax, the income tax, gets shelved.

The IBO provides analyses on both options. For instance, extending the sales tax to laundering, dry cleaning and similar services would raise $35 million. Extending it to cosmetic surgical and non-surgical medical procedures would raise $60 million, and imposing the sales tax on capital improvements would raise $200 million.

The sales tax is regressive, of course, because everybody pays the same rate, so the sales tax poses a greater burden on lower-income residents than high-income ones. The city's personal income tax, on the other hand, is at least modestly progressive, with rates ranging from 2.91 percent to 3.65 percent. (The top rate starts at $90,000 of taxable income for joint filers.)

The IBO analyses of income tax options include two versions of a commuter tax. The most familiar is the proposed restoration of the small tax -- 0.45 percent for wages and salaries and 0.65 percent for self-employment, earned in the city -- that existed between 1971 and 1999 until it was eliminated without city input in 1999 by a Republican governor, Republican State Senate and a Democratic State Assembly (controlled by Democrats from the city). Restoration would bring in $715 million.

An alternative, progressive commuter tax, with a rate one third the city's resident income tax rates, would bring in nearly $1.4 billion in 2010. Either of these would have to muster support with the governor's office, State Senate and State Assembly, a questionable proposition.

The mayor's November 2008 reference to income tax options -- since dropped -- included only an across-the-board rate increase of either 7.5 percent or 15 percent. Neither would be progressive, although they would raise a lot of money: $660 million and $1.32 billion, respectively.

The IBO sets out two other options, both of which would increase rates progressively.

The first option is similar to the structure of tax rates in effect during an earlier fiscal crisis, from 2003 to 2005. It would add two new rates to the current four rates. They would range from 2.91 percent to 4.2 percent, with the highest rate starting at $450,000 for joint filers. (The top rate from 2003 to 2005 was 4.45 percent, as it was for much of the 1990s.) That would raise $455 million in 2010. Proponents say this would affect only 4.5 percent of all city resident taxpayers; opponents argue city dwellers are heavily taxed already and those affected might leave the city.

A more progressive option would lower the lowest income tax rates, creating six brackets. They would range from 2.68 percent to a 4.2 percent top rate that, as above, kicks in at $450,000 for joint filers. Proponents argue this makes the rates more progressive and gives a majority of taxpayers a tax cut, while raising an additional $342 million in 2010 because of the two higher rates. Opponents say this would cause some taxpayers with incomes about $1 million, whose average tax increase would be $144,000, to leave the city, thus reducing new revenues.

Poetry, Prose and 'Graphatas'

Along with its 70 budget options, The IBO offers clear, independent, and comprehensive analyses. It seems reasonable to expect the mayor and OMB to do the same. Readers of city budget documents expect to find little poetry. But they do expect prose.

What OMB writes, however, could be called "tablese/graphese." Tables and graphs are the lifeblood of budgeteers, but they generally get an interpreter. (Former Mayor Rudy Giuliani used his electronic pointer at budget briefings with skill and evident joy.) OMB currently gives us numbers, hundreds of pages of numbers. But little else.

The summary to the mayor's January 2009 financial plan -- presumably intended for the City Council and the general reader has in its 63 pages exactly 36 bulleted sentences. Not a single paragraph. What we're left with is tables and graphs, with often opaque headings. ("If the Current 30% Loss in Asset Value Continues, NYC Retirement Systems' Employer Contributions Will Increase by $10.9 billion Through FY 2016 to Cover the Loss in Corpus Value" is typical.) The 19 pages of the summary's Economic Update offer not one sentence of explanation.

The city may catch a big break through the economic stimulus plan that has just been signed by President Barack Obama. Apparently $87 billion of the $789 billion plan will go to states as Medicaid spending relief. Assuming New York State shares those savings equitably with the city, Bloomberg's $1 billion projected federal revenues in the January financial plan may turn out to be an underestimate.

But whatever happens with federal aid, at a time of national and local economic/fiscal uncertainty it would be good to have a dialogue with our elected officials in this city. The effectiveness of any such dialogue begins with the quality of the city's budget reports. More plain English and more usable information - as in the IBO's report -- would be a good start. This is a time for gravatas, not "graphatas."

Meet the Independent Budget Office

Have any questions about the administration’s new preliminary budget? Ronnie Lowenstein of the Independent Budget Office will join Gotham Gazette City Hall reporter Courtney Gross to answer your questions live. Check back here at 2 p.m. to participate.

You can also send your questions by twitter or email them to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

From 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. Feb. 10, Gotham Gazette will host the Independent Budget Office’s director for a live online chat. Lowenstein has been director of the office since 2000 and a staff member since its inception as the city’s independent, nonpartisan fiscal analyst. She will take your inquiries on what is included and not included in the budget, how its proposals could affect you and what the city’s options really are to reduce a gaping $4 billion deficit.

Comment

Fix the Budget

No one ever said you needed to start a multi-billion dollar company or get an MBA to set the city's finances straight.

With Gotham Gazette's help, you can increase spending for education or reinstate the commuter tax from the comfort of your own laptop.

Last month, Mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed a $58.8 billion budget that could slash $1 billion from city spending, increase the sales tax by .25 percent (not to mention broaden it to include clothing, hair cuts and more) and seriously lean on Albany and Washington to pitch in billions of additional funding.

So that's his plan. But what would you do?

Bloomberg overturned the city's term limit so he could have a chance to lead the city through this ever-more dreary recession. With our new budget game, BALANCE, you can bypass the City Council entirely and fix our fiscal woes on your own.

Would you increase spending and raise taxes? How about the personal income tax or tolling the East River crossings? Which departmental cuts do you think are the most severe and should be reversed?

Take the reins, but make sure you end balanced or with a surplus. We're not Washington -- we can't run a deficit.

Once you're done, send us the results and we'll report back on how Gotham Gazette readers would balance the fiscal year 2010 budget.

Keep your home page set here, and we'll continue to update you on how the city's real fiscal plan unfolds between now and when our budget must be approved in June.

Play BALANCE now.

How to Balance the State Budget

The financial meltdown and the recession have thrown state budgets out of whack across the country. Plummeting revenues have given New York State a projected budget gap of $1.7 billion for the current fiscal year and $13.7 billion for the new fiscal year that will begin April 1. The combined deficits of New York and 45 other states through 2010 are predicted to reach a staggering $350 billion, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Meanwhile the recession is taking a toll on people across the state. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers have lost their jobs, their homes or their hopes for a secure retirement or a better future for their children. New York's unemployment rate jumped by a full percentage point in December to 7 percent, the greatest one-month increase on record since 1976. The state has lost 121,000 jobs since its August 2008 job peak. More than 50,000 New Yorkers lost their homes through mortgage foreclosures last year.

As the economic damage ripples out from Wall Street, Gov. David Paterson has proposed drastically slashing state spending. School aid, health care, SUNY and CUNY, child care, program for the elderly, homeless prevention and long-overdue wage increases for social service workers struggling to stay above the poverty line will all feel the effects of the budget ax. While he chops away, though, the governor has steadfastly refused to call for a progressive hike in the state income tax -- an increase that would affect only the most affluent New Yorkers.

For the governor, "shared sacrifice" means that the state's low- and moderate-income families and communities must sacrifice while the fortunate few at the top, who benefited the most from the tax cuts of the last 15 years and from this decade's economic growth, will emerge from the budget largely unscathed.

Too Much Spending -- or Too Little Revenue?

Anti-government voices have mounted a steady drumbeat calling for steep budget cuts, ostensibly to rein in "out of control" state spending. The reality? State spending has increased to fund important new commitments such as providing medical care to people without health insurance and aiding urban school districts with high concentrations of children from poor families. The state government also dramatically expanded spending on property tax relief and acted to partially undo years of underinvestment in mass transit and public higher education.

Aside from these major commitments—all supported, by the way, by David Paterson when he was a state senator and lieutenant governor--state spending from 2004 to 2008 grew at less than 2.9 percent a year, barely the pace of consumer inflation.

What the state failed to do, however, was provide the revenues needed to finance such initiatives through the ebbs and flows of the business cycle. Much of the state's current budget crisis might have been averted had the state reversed even part of the tax-cutting spree carried out from 1994 through 2000. All tolled, these cuts now reduce the state's tax revenues by about $20 billion a year, an amount that would erase even the huge projected budget gaps of $17 billion for 2011 and 2012.

Less Pain, More Gain

Like the other 49 states, New York has to balance its budget in both good times and bad. Facing a sizable budget gap during a recession, states have only bad choices. Neither cutting spending nor raising taxes eases the downturn.

Many economists, however, point out that it is less harmful to the economy to raise taxes in a way that limits its effects largely to high income people than to cut state spending that mainly benefits low- and moderate-income people or that pays the salaries of teachers, police officers and other civil servants. In December, 120 economists from across the state sent a letter to Paterson saying, "Economic theory and historical experience [show] it is economically preferable to raise taxes on those with high incomes than to cut state expenditures."

This is because high earners typically spend only a fraction of their incomes in any given year, saving the rest. On the other hand, state spending goes to pay workers, provide services and put money in the hands of New Yorkers in need. This means the money goes directly into the economy, priming the pump at a time when it is desperately needed. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University made the same point in a letter to the governor last March.

Public opinion across the state strongly favors increasing income taxes on high earners over cutting spending for health care and education. The governor, though, has argued that raising taxes on the wealthy will drive them from the state.

No evidence exists to support that claim. In 2003, New York temporarily raised its top income tax rate from 6.85 percent to 7.7 percent. During the three years that this increase was in effect, the number of high-income returns grew significantly. This experience in New Jersey, which permanently raised its top personal income tax rate to 8.97 percent in 2004, has been similar, according to a Princeton University study.

Beyond a High-End Tax Hike

Paterson and the two top legislative leaders -- Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith -- have committed to closing the projected $1.7 billion budget gap for the current fiscal year by Feb. 4, even though the year does not end until March 31.

What should they do? In addition to its investments in infrastructure, unemployment insurance modernization and other measures, the massive economic recovery bill now making its way through Congress includes aid, called “state fiscal relief,” for the explicit purpose of helping states balance their budgets without putting too much additional drag on the economy. Since this legislation is likely to go to President Barack Obama for his signature in mid to late February, the sensible course would be for Paterson and the legislature to wait to see exactly how much “budget balancing” aid New York will receive under the final legislation. The chances are excellent to certain that the state will get several billion dollars it can use right away, since important parts of the “state fiscal relief” is retroactive to Oct. 31, 2008.

In the unlikely event that the immediate “state fiscal relief” does not close this year's gap, the governor has already identified at least $600 million in various reserve funds that could be tapped to balance the books. On top of that, the state has at least $1 billion in its Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund that it could us if needed. Even if it had to borrow against that -- which seems unlikely -- the state still has $400 million in a newer "rainy day" fund as well as a few hundred million in other reserves.

Closing the projected $13.7 billion gap for the 2010 fiscal year will prove more difficult. A progressive tax increase would generate roughly $5 billion. This, along with several billion more from an increase in the federal payments for Medicaid or state fiscal relief in the stimulus package will address most of the budget gap.

Some budget cuts may be unavoidable, but the state should also consider closing tax loopholes such as one that benefits non-resident hedge fund general partners working in New York State and taking other actions to generate budget savings. These could include ending the wasteful and failed Empire Zones program, increasing the use of state engineers rather than contracting out that work to expensive consultants, or using the state's sizable purchasing power to get better prices on prescription drugs.

Restoring Tax Fairness

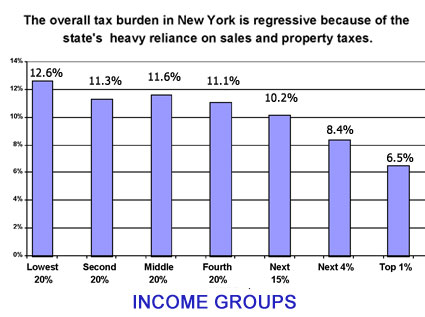

Click here for a larger image

Raising taxes on high earners would also be a step toward restoring fairness to New York's graduated income tax, which has become significantly less graduated over the years. Today, because of the state's increased reliance on regressive sales and property taxes, New York's middle- and lower-income households pay a higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes than the top 1 percent or the top 5 percent (see chart).

Moreover, as astounding as it may seem, data indicate that all of the income growth in New York State from 2002 to 2009 has gone to the wealthiest 5 percent. In 2009, the other 95 percent of households have roughly the same incomes they had in 2002. When you factor in inflation, the combined income of the bottom 95 percent of New Yorkers actually shrunk.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman recently wrote in his New York Times column that, in the absence of Obama's massive stimulus proposal, we might see 50 Herbert Hoovers in state houses across the country respond to revenue shortfalls by slashing their budgets or raising regressive taxes, making the economy worse in the process. The new stimulus program is designed, in part, to head off that result. For the part of the budget gap that cannot be closed through federal funds, the state should turn to progressive tax policies. This is the right economic policy, sound fiscal policy, and the only approach in keeping with the governor's theme of "shared sacrifice".

Frank Mauro is the executive director of the Fiscal Policy Institute. James Parrott writes a regular column on the economy for the Gotham Gazette and is FPI’s deputy director and chief economist.

An Election Year Budget

It was the same scene: reporters scrunched into rows of blue plastic folding chairs chaotically checking their BlackBerrys; the chiefs of the city government's largest departments lining the front row; and the mayor -- charcoal power suit, red tie -- delivering a particularly morose PowerPoint, presenting a practically apocalyptic view of the city's budget.

Let the 2010 budget season begin.

On Friday, Mayor Michael Bloomberg released his preliminary budget for fiscal year 2010, which starts July 1. With the economic meltdown showing no sign of stopping, the mayor proposed to slash almost $1 billion from city spending and raise the city's sales tax to create $900 million in revenue. He has threatened to chop the city's work force by about 8 percent -- including 14,000 teachers -- if funding from Albany does not materialize or municipal employee unions do not compromise on health benefits.

Though most city officials say the country's dire straits call for serious measures, they also recognize that 2009 is an election year. Election years breed political compromises. Not only will city officials hear from advocates and constituents protesting the cuts, they also will hear from their political opponents. Inevitably, decisions made in June affect the election's outcome in November.

Forget the 2010 budget cycle. Say hello to the '09 campaign season.

The Budget Breakdown

In 2005, after several years of gloomy budget scenarios, the mayor was upbeat -- he called his preliminary budget then "cautiously optimistic."

Translation: Things had improved since the downturn following September 11th, and Bloomberg was looking for another four years as the fiscal guardian of one of the biggest budgets in the country.

Fast forward four years and we see the same mayor seeking another term in office (albeit unexpectedly). This time around, with the economy in disarray, Bloomberg's forecast is less confident.

"I am as optimistic as I can possibly be for the longer term," the mayor said, reiterating that the city would not return to the 1970s when core services were slashed due to an economic downturn.

"I think we'll be able to do it together," the mayor added. "We have the seasoned leadership and the public support."

The city faces a yawning $4 billion budget gap due to a decline in tax revenues, attributed to the financial crisis on Wall Street. To address these fiscal woes, the mayor proposed a $58.8 billion budget -- a decrease from the projected 2009 budget of $60.1 billion. The city's deficit, the mayor reminded reporters Friday, could have been as much as $6 billion if the City Council and mayor had not acted to cut spending and increase property taxes late last year.

Essential to the mayor's proposal is funding from both the federal and state governments -- funding that is far from guaranteed. Lobbing the problem a few hours north, the mayor urged the State Legislature to rescind a proposed $770 million cut to education aid for the city or see close to 14,000 layoffs at the Department of Education, most likely teachers (with attrition that number is 15,630). The mayor said aid the state receives from Washington's economic stimulus package could right Albany's wrong. (See related story on state budget cuts.)

"I am sympathetic with the state," the mayor said, referring to the projected $15.4 billion deficit in Albany. "Here is a chance for Albany to pay for their fair share of education with someone else's money. If there was ever a case for us to put pressure on them, it's now."

The mayor plans on filling the budget gap through $1 billion in aid from the federal government for Medicaid, almost $1 billion in agency spending cuts and about $1 billion from the restoration of state cuts and renegotiating health care benefits for union workers. He also is considering increasing the sales tax to 8.625 percent from 8.375 percent in addition to repealing the exemption for clothing and starting to tax items, like haircuts that previously were tax-free.

Bloomberg said a sales tax increase is not definite since the economic climate is still settling and revenues could change between now and when the budget must be approved in June.

Overall, unless the city gets help from unions and the state, the municipal workforce could decline by nearly 23,000, Bloomberg said, through both layoffs and attrition.

Under the mayor's doomsday proposal, the majority of layoffs are slated for education, but other departments would not be immune: the Administration for Children's Services could see 608 layoffs, Homeless Services 222, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 57 and the Finance Department 17. The mayor proposed losing 7,686 positions through attrition from multiple agencies, including a reduction of 1,000 uniformed police officers.

The Teachers Take Their Toll

Just in time for the Superbowl, the mayor punted.

The most drastic of cuts, specifically the Department of Education layoffs, which comprise 80 percent of the total proposed workforce reduction, are because of Albany, the mayor said.

That sparked this reaction from United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten: "The union has pledged, and indeed has been working together with the mayor on the federal recovery and on ensuring we get a fair share from Albany. But making virtually all our first, second and third-year teachers pawns in this political battle is callous and unfair to them and their students. Worse, in blaming Albany, the city itself masks the magnitude of its own cuts.”

Weingarten is not alone in thinking the mayor is pegging Albany for the city's problems.

Baruch College Professor Doug Muzzio said the mayor's budget was overflowing with "wishing and hoping." If the federal and state funds he is expecting do not come through, then his re-election prospects could suffer.

"If you lay off 15,000 teachers, man, that’s going to resonate," Muzzio said. "It's going to resonate loudly, through bull horns."

Whether it's political maneuvering or financial strategy, other officials and political observers think the mayor has a point. At the end of the day, they say, teachers will not be sacrificed.

"It would not be acceptable to lose 15,000 teachers, period," said Councilmember David Yassky, who also is a candidate for city comptroller. "The mayor is absolutely right that it's up to Albany to keep our school funding constant. What he is trying to highlight there is that the governor's budget would reduce our school aid quite dramatically."

Already Unpopular Cuts

As for spending in general, Bloomberg recognized some departments were harder hit in this preliminary budget than others.

"It would be fair to say everybody takes the same hit, but the real world is you have to keep the streets safe, and the real world is you have to have a certain amount of guards for each prisoner," Bloomberg warned.

Of all the agency cuts, social services have been slashed the most -- by about 8.2 percent. Youth programs, libraries, cultural affairs, CUNY, transportation, and health and mental hygiene all have cuts around 7 percent. The Administration for Children's Services, which is slated for significant layoffs in comparison to some agencies, has seen a 6 percent cut.

The police, fire, correction and sanitation departments all received cuts of between 2 and 3 percent.

But how will these reductions, if approved by the City Council come June, affect the average New Yorker?

The Sanitation Department will reevaluate trash routes (and their frequency) so workers will pick up more tonnage. The city is doing away with pickups of grass clippings. After-school programs, including summer youth programs, will be cut significantly.

Bloomberg proposed to eliminate dual company firehouses by taking away either an engine or a ladder in certain stations. He also proposed to eliminate a firefighter position on 64 engines, bringing down the count to four (It will be done through attrition and it excludes lieutenants on the scene).

He wants to increase rates for single rate parking meters from 50 cents to 75 cents an hour, stop the city's nutrition counseling for those with HIV, increase admission fees at the Central Park Zoo and the Queens and Prospect Park wildlife centers and cut funding to senior centers.

Proposals floated to increase revenue include an increase in CUNY tuition by $200 a semester and a 5-cent tax on plastic bags, both of which would require approval by the state government.

All of these proposals, particularly the cuts to social services, could provide ammunition for challengers come November.

"I think it's shortsighted by Mayor Bloomberg to propose these cuts in terms of managing the city's budget and in terms of managing his political future," said Sean Barry, the director of the NYC Aids Housing Network. "We don’t want to return to the time where New York City is warehousing homeless people with AIDS in welfare hotels."

Politics or Policy

Bloomberg didn't have the last word on Friday.

Not to be outdone, one of the mayor's political rivals, Comptroller William Thompson, came out with his own proposal immediately following the address: upping the city's personal income tax on those earning more than $500,000.

When Gotham Gazette asked for more details about the comptroller's suggestion, a spokesman said Thompson was reviewing a number of ideas and would release details once finished.

Already some advocates and council members see an income tax increase as a better option than a hike in the sales tax, which they call "regressive," since it will have a disproportionate effect on lower-income people.

"Sales tax are regressive," said Jennifer March-Joly, executive director of Citizens' Committee for Children of New York. "You raise revenue that way, that’s clear, but the problem is for those that need to shop and make far less money. It's much more burdensome than the income tax."

With sides taken and criticism thrown, revenue options may be the first concrete mayoral campaign issue in 2009.

"The mayor’s plan would balance the budget on the backs of working people," read a statement from Thompson released following the mayor's budget address. "The mayor’s budget proposal relies far too heavily on a sales tax increase at a time when the city’s hardworking families and small businesses are suffering."

The mayor said he had not put an income tax increase on the table, because he anticipated the state would increase it to solve its own fiscal woes. (See related story.)

Tackling A Base

A critical element in the mayor's budget plan is tapping city unions to pay 10 percent of their health insurance premiums. According to the Independent Budget Office, 90 percent of city employees enrolled in its insurance program do not premiums.

Brave, maybe. But political observers say it could be tough to cross unions in an election year.

"The mayor is now in a position, regardless of re-election issues he is going to have, to make the unions his partners or his election will be more problematic," said a source close to the unions in New York City. "If he gets re-elected he will have real war."

Obviously, Bloomberg does not rely on the city's unions for financial support for his campaigns, as many politicians without billions of dollars do. In a citywide election, though, union support is key.

So far, the reaction to his proposal has been icy.

In response, Lillian Roberts, the executive director of city's largest municipal employees union, District Council 37, released the following statement: "Union members should not be asked to shoulder the bulk of this burden. Workers did not create this fiscal crisis and cutting into their hard earned benefits should not be viewed as the quick fix that will solve it."

Others scoffed at how realistic this proposal would be: "Be serious here, Mr. Mayor," quipped Muzzio.

The mayor has previously been criticized for not doing more to rein in rising pension and benefit costs, often thought of as "uncontrollable." Some, including political consultant Joseph Mercurio, say now is as good a time as any to negotiate union contracts. According to the mayor's office, payments to retirees for pensions and health benefits will increase from $11.7 billion in 2007 to $16.8 billion in 2015.

An analysis last year by the Independent Budget Office projected about $400 million in savings could be garnered during the first year of city employees paying 10 percent of their premiums.

The Political Hurdles

Councilmember John Liu, a candidate for public advocate, recognizes a tough budget year can mean tough politics.

"It stinks to run for election in a very difficult time," said Liu.

Though officials interviewed by Gotham Gazette say politics will not enter into their decisions on the budget, their policy choices could certainly affect the election.

"Politics plays a role in everything," said Councilmember Letitia James, who is running for re-election to her seat in Brooklyn.

Bloomberg extended term limits and launched his third term candidacy because he said he was needed to lead the city through tough times. That said, the outcome of this year's budget could dramatically influence whom the electorate (which still favors Bloomberg) chooses this November.

Most politicians, even those who themselves are seeking higher office (like Yassky, Liu or David Weprin), contend politics will not come into play this budget cycle.

"It's fiscal reality," said Councilmember David Weprin, the council's finance committee chair and a candidate for comptroller. "I think you need somebody in the comptroller's office that is going to recognize the fiscal situation and deal with it."

Yassky, agreed. "You first decide what's the right policy and then you go and make your case to voters and they can understand it."

Arguably the most eternal optimist is the alleged non-politician, the mayor himself.

"I hope and I expect that the fact that it's an election year will not enter into it at all, because (the council doesn't) have any choice, nor do I," the mayor said Friday. "We have to address these issues, and I would argue the public wants these issues addressed and wants you to make the tough decisions. My advice to anyone in government is do what you think is right and in the long term it will work out."

Can Obama Help Save New York?

As Barack Obama takes office today, many New Yorkers have high hopes that change has come -- and it will be change for the better. Much of that hope springs from excitement surrounding the first African American president ever and the first one in decades with urban connections. And in this overwhelmingly Democratic city, where Obama beat Republican John McCain by a four-to-one margin, there is a palpable hunger for new ideas and attitudes.

Like most Americans, New Yorkers want action too -- particularly on the economy. The recession has hit New York, the home of Wall Street, hard, with rising unemployment, job losses and slowdowns in all types of businesses. As a result, the state faces a $15 billion deficit over the next 15 months and the latest projections show the city government, thought to be on firmer ground, peering into a $4.3 billion abyss.

City and state leaders, along with fiscal experts and ordinary New Yorkers, hope Obama can help. At his State of the City last week, Mayor Michael Bloomberg rolled off a number of initiatives that called for some federal dollars, including a proposal to revamp the city's air traffic control system and a pilot program that offers jobs to struggling students if they stay in school. (For more on the mayor's State of the City, see A Recovery Package From Bloomberg.)

Highest on the city's wish list may be federal dollars for infrastructure. "Our cities have to be a central focus of any recovery plan," Bloomberg said recently. Any federal funding should first go to our urban environments, Bloomberg added, especially for bridges, roads, trains and tunnels.

Other New Yorkers have their own ideas. Here several experts offer their views about the proposed economic stimulus package and what the new administration can do to help lift New York -- and the nation -- out of the economic crisis.

Paying Attention to Cities By Jonathan Bowles

After years of federal policies neglecting urban areas, Barack Obama has sent some encouraging signals that he understands their importance. Certainly, New York could use a helping hand. The director of the Center for the Urban Future lays out some ideas for what the president could do to aid New York.

An $825 Billion First Step By James Parrott

The stimulus package proposed by Congress is key to halting the economy's downward spiral but it will not solve all our problems. Economist James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute looks at what the package would do -- and what more needs to be done.

Using the Crisis to Prevent the Next One By J. Mijin Cha

The current turmoil can help us reduce our dependence on Wall Street and create good "green collar" jobs that help fuel a resurgence of the middle class. The director of campaign research at the Urban Agenda explains how.

Infrastructure Investments that Make Sense By Carter Craft

As big as the stimulus package may be, the country has to invest the money wisely. An urban planner offers some novel ideas for New York projects -- from recycling grease to ferries for freight.

From Gas-Guzzling Cars to Clean Buses By Charles Stone

Simply lending funds to struggling auto companies won't spur economic growth. Instead, an economist suggests, the government should create a voucher program to deploy the resources of the auto companies, spur investment -- and help the environment.

Previous Articles

A Federal Stimulus for City Parks By Anne Schwartz

Advocates hope that President Obama and Congress will recognize that funding parks would not only improve the quality of life and the environment but also spur investment and raise real estate values.

Stimulus Money: The Downturn's Silver Lining? By Graham Beck

The stimulus package could offer more federal funds for transportation projects. The MTA is making its list, but there are sure to be lots of restrictions -- and competition

Using This Crisis to Prevent the Next One

Photo (c) Urban Agenda

While the economic picture is grim across the country, New York City has been especially hard hit in recent months. The city's heavy dependence on Wall Street revenues has left us facing a projected budget shortfall of nearly $4 billion. Adding to the city's crisis, a quarter of the shortfall is due to state cuts resulting from Albany's crippling financial difficulties.

For More on Helping New York's Economy

Paying Attention to Cities By Jonathan Bowles

After years of federal policies neglecting urban areas, Barack Obama has sent some encouraging signals that he understands their importance. Certainly, New York could use a helping hand. The director of the Center for an Urban Future lays out some ideas for what the president could do to aid New York.

An $825 Billion First Step By James Parrott

The stimulus package proposed by Congress is key to halting the economy's downward spiral but it will not solve all our problems. Economist James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute looks at what the package would do -- and what more needs to be done.

Infrastructure Investments that Make Sense By Carter Craft

As big as the stimulus package may be, the country has to invest the money wisely. An urban planner offers some novel ideas for New York projects -- from recycling grease to ferries for freight.

From Gas-Guzzling Cars to Clean Buses By Charles Stone

Simply lending funds to struggling auto companies won't spur economic growth. Instead, an economist suggests, the government should create a voucher program to deploy the resources of the auto companies, spur investment -- and help the environment.

Previous Articles

A Federal Stimulus for City Parks By Anne Schwartz

Advocates hope that President Obama and Congress will recognize that funding parks would not only improve the quality of life and the environment but also spur investment and raise real estate values.

Stimulus Money: The Downturn's Silver Lining? By Graham Beck

The stimulus package could offer more federal funds for transportation projects. The MTA is making its list, but there are sure to be lots of restrictions -- and competition.

The crisis highlights the danger of the city's economic over-reliance on Wall Street. Even when times are good, only a few New Yorkers reap economic windfalls. When times are bad, the entire city suffers.

For all the pain it is causing, though, the sagging economy presents us with the chance to rebuild our economy in a way that prevents similar economic crises in the future. The federal economic stimulus package before Congress presents an opportunity to build a greener and more equitable economy. Urban Agenda, convener of the New York City Apollo Alliance, urges Congress to fund projects that will create high-quality, "green collar" jobs and help make New York City more environmentally sustainable.

A stimulus package for New York City must focus on increasing investments in public infrastructure -- rehabilitating and retrofitting schools, buildings and mass transit systems - not on giving tax breaks. Currently, the Obama administration is proposing $150 billion in tax cuts for businesses. However, prominent economists, including an advisor to Republican presidential candidate John McCain, note that every dollar spent on public infrastructure projects generates $1.50 in economic activity, while tax breaks lack this "multiplier effect." Every $1 in tax cuts produces less than $1-- and sometimes as little as 30 cents -- of economic activity.

Green Is Not Enough

While we need to act quickly, we must also act responsibly. It is not enough to just create "green" jobs. Instead, we must create "green collar" jobs that pay well, provide health benefits and offer opportunities for career advancement while improving our environment.

This is key. Creating jobs that pay poorly and do not provide health benefits or pathways out of poverty will lead to an underclass of workers employed in green jobs but unable to make their way into the middle class. If we consider both environmental benefits and wage and job standards, we can have jobs that will help the resurgence of the middle class, strengthen our economy and make New York City a leader in sustainability.

The NYC Apollo Alliance has compiled a list of recommendations for evaluating projects to ensure that we maximize the potential of our green collar workforce. (The full document can be found here.). Projects funded with stimulus dollars should:

- Create employment for a wide spectrum of workers, from low-skilled to highly skilled.

- Support local employment opportunities. Outsourcing occurs not only when jobs are sent overseas, but also when labor is imported into an area with an already trained and ready labor pool that can, and should, be employed.

- Create jobs that offer good wages, health care benefits and paid time off.

- Promote employment in environmentally sustainable areas, such as retrofitting building, brownfield redevelopment and urban forestry.

- Promote the retrofitting and maintenance of existing infrastructure, such as mass transit systems, roads and bridges.

Using these criteria to evaluate projects proposals will help rebuild our economy and create a greener, more sustainable city. For instance, using federal stimulus funds to create an "Efficiency Matching Fund" providing a 100 percent federal match for state-approved energy efficiency programs would help quickly channel funds to green job development. Every $1 invested in such programs saves $2 to $4 in energy costs for consumers, freeing up additional consumer purchasing power. Energy efficiency programs also bring us closer to environmental sustainability.

The economic stimulus must fund training and readiness programs to ensure there are enough skilled workers ready to do these tasks. The Consortium for Worker Education, the Association for Energy Affordability and the New York Industrial Retention Network developed a plan to integrate economic development and workforce development to promote energy efficiency. With funding, this proposed Green Jobs Center would include a training center to assess, train and place over 2,700 workers in the energy efficiency industry. The center also would provide business services for over 900 businesses seeking to expand or enter the energy efficiency market over a three-year period.

Finally, to ensure that stimulus spending creates jobs in the near future and new industries in the long term, it must include language that allows cities and states to give preference to local companies when they purchase goods and materials used in federally funded capital projects. This will nurture local green manufacturing and reduce the carbon footprint of projects by removing the need to transport products long distances.

The Wall Street disaster offers us the opportunity to build a new economic future. Wisely invested, the federal stimulus can generate the green collar jobs that will rebuild our middle class and create a more sustainable environment for generations to come.

J. Mijin Cha is director of campaign research at Urban Agenda, convener of the Apollo Alliance. The alliance is holding a public forum on Feb. 2nd to discuss the New Apollo Plan, the economic stimulus and New York City. For more information, visit www.urbanagenda.orgÂ

The Budget Outlook Goes from Bad to Worse

Left photo (cc) Nic McPhee

The Independent Budget Office's January Fiscal Outlook and other recent budget reports just might give Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council members who extended term limits at least a brief twinge of regret. For the remainder of this term and probably for part of their next, they will confront increasingly grim economic and fiscal prospects. The mayor's November Plan, the modification of this year's budget approved by the council in December, already looks like ancient history.

The mayor in November forecast a $1.3 billion budget deficit for fiscal year 2010, which begins July 1, 2009. The Independent Budget Office now projects a $4.3 billion gap. While the mayor in November set the estimated 2011 deficit at $5.0 billion, the IBO now puts that number at $7.0 billion. A report by the state comptroller says the 2011 deficit could reach as high as $8.0 billion.

What has happed since November, of course, is that the economy has spiraled downward. The now-acknowledged recession is costing hundreds of thousands of people across the nation their jobs and causing plunging tax revenues at all levels of government.

The impacts of that recession were slow to affect New York City. But now everything has changed. Job losses in the city are accelerating and, with that come projections of sharper tax revenue losses and growing budget deficits.

The Employment Outlook

The IBO report says the city will lose 243,000 jobs the peak of 3.8 million jobs reached during the first quarter of 2008. Some 82,300 of those lost jobs will be in the financial activities industry, 48,900 in securities jobs alone.

In general, the IBO report paints a weaker job picture than the mayor did two months ago. Bloomberg forecast a loss of 147,000 private-sector jobs through this calendar year and assumed the number of jobs would begin to grow again in 2010.

The Revenue Slump

As a result of the jobs losses and overall deteriorating economy, business and personal income taxes will plummet, according to the IBO. The three business income taxes -- the general corporation tax, the banking tax, and the unincorporated business tax (mostly a tax on professionals like accountants and lawyers) -- tripled to over $6 billion from 2003 to 2007. By 2010, the IBO see them declining to $3.7 billion, a 38 percent drop in three years.

The office expects personal income tax revenues to drop by $1.4 billion from the current 2009 fiscal year 2010. And its sees only modest increases in revenues from the tax in 2011 and 2012.

There is some good revenue news. The most stable -- and by far the biggest -- of the city's major taxes is the real property tax, which, because of the complex nature of the tax, is much less subject to current economic conditions. The IBO says property tax revenues - after the 7 percent rate increase for the second half of fiscal 2009 approved by the council in December -- will total $14.4 billion this fiscal year, a 10.1 percent increase from 2008.

"Because of the gradual phase-in of past increases in property values and the second step of the tax rate increases, revenues are expected to continue growing at double-digit rates in 2010, rising by 11.8 percent to $16.1 billion," the report says. As the phase-in of increases in property values is completed, though, revenue growth will slow in 2011 and 2012.

The IBO projects that the other big city tax, the 4 percent city sales tax, will decline by 3.1 percent in fiscal 2009, to $4.7 billion, and by 7.1 percent in 2010 to $4.4 billion. Sales taxes, the report says, will rebound in 2011 and 2012, reaching $5.0 billion in the following two years.

Balancing the Budgets

The current and future deficits have forced the mayor into a new budget strategy. In recent years, the big surpluses, for the most part, have been carried over to cover expenses for subsequent years, making each year's budget balancing that much easier. In addition, the mayor placed $2.5 billion of the 2006 and 2007 surpluses in a new reserve fund, the Retiree Health Benefits Trust Fund, to be used to meet future liabilities for retirees' health expenses.

Today, both these strategies have faltered. The $1.8 billion surplus in 2009 that the mayor hoped to use to fill gaps in the 2010 budget has shrunk to $568 million, according to the IBO.

Furthermore, Bloomberg proposes to use more than $1.1 billion of the retiree health fund to make up for the anticipated growth in pension expenses caused by losses in pension fund investments. That move has caused some grumbling from the IBO and the state comptroller.

The IBO, for instance, says the new use of the retiree trust fund "undermines the city's goal of beginning to fund its enormous liability for future retiree healthcare expenses."

And the state comptroller's December report says that the move can be seen as "a sign of serious fiscal stress" that will shift the burden of paying retiree costs to future taxpayers. In contrast, the city comptroller in his December report on the state of the city's economy accepts the temporary use of the retiree money but urges a quick replenishment of the fund.

To fill the deficit, the mayor has asked agency heads to prepare for an additional 7 percent cut in expenditures, which would save $1.4 billion. He also has proposed an unspecified $800 million in new taxes. These moves would cover only half of the IBO's projected $4.3 billion deficit, although Bloomberg may come up with additional cuts and taxes when he announces his preliminary budget at the end of this month.

The State and Federal Role

That preliminary budget for fiscal year 2010 will represent the next step in what will likely be a tough five-month struggle to balance next year's budget and stabilize the city's longer-term fiscal condition. Uncertain state and federal politics complicate the picture.