Judges' Stagnant Salaries

The Chief Judge of the State of New York is contemplating suing the State of New York. Several trial judges have already brought a lawsuit against the governor and legislature. And judges from Brooklyn to Buffalo are planning to march on Albany on May 1.

These unprecedented actions are last-ditch efforts to achieve an item dropped from the 2007 state budget in the final hours of negotiations: pay raises for judges.

WHY JUDGES SAY THEY DESERVE A RAISE

New York State Supreme Court justices are paid $136,700 a year; upstate Family Court and other judges receive $119,000 or less.

Although these salaries are higher than that of many New Yorkers, judges, with seven or more years of higher education, have given up far more lucrative opportunities that go along with careers in the legal profession. Major New York City law firms pay close to $200,000 to recent law school graduates who have not even passed the bar exam; federal trial judges are paid $162,500 and are expecting a salary increase; corporate law firm partners enjoy seven figure incomes plus bonuses.

New York judicial salaries are among the lowest in the nation. The state’s judges have had only two salary increases in the last 20 years, the last one eight years ago. Since then, the cost-of-living has risen by 26 percent.

Chief Judge Judith Kaye recently declared the situation to be "disgraceful," "devastating," "a crisis," and "an emergency."

WHY JUDGES HAVEN'T RECEIVED A PAY INCREASE

Editorials, good government groups and bar associations have all supported a pay increase. Governor Eliot Spitzer put increased judicial compensation into his proposed budget. But the governor, along with legislative leaders Sheldon Silver and Joseph Bruno, shut the judiciary out of the budget negotiations.

Legislators have decided that judges will get a raise only if they can also give themselves a pay boost. But since there is no public support for pay raises for legislators - who have been widely described as "dysfunctional" - judges are not getting one either. Meanwhile, Spitzer has said that, while he supports raises for judges, he opposes a pay raise for members of the State Senate and Assembly.

Albany lawmakers work part-time and are free to practice law or engage in other business, options prohibited for judges. In fact all three men who are holding up judicial pay increases enjoy income from other sources. Eliot Spitzer's 2006 income from his midtown Manhattan real estate holdings, alone, was almost $2 million. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver has a lucrative law practice, details of which have not been disclosed, and Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno a number of business dealings.

The three branches of government -- executive, legislative and judicial -- are meant to be equal, but the judiciary contends that the other two are interfering with judicial independence by withholding fair compensation. A lawsuit could challenge the legislature’s hold on the judiciary but it would take years to be resolved.

WHY IT MATTERS FOR NEW YORK

For the low-earners of the legal profession, living in New York City has become a daunting challenge. Many judges, who went to law school with the dream of serving the public from the bench and rejected opportunities to follow the money, now question that decision.

Every day judges throughout the state accept the profound responsibilities of deciding who is imprisoned and who goes free, deciding when a feeding tube should be discontinued, and deciding who should have custody of a child. Such work is essential to a democratic, civilized society.

The risk the public and the judiciary face is that only lawyers with independent wealth will become judges, causing severe damage to diversity and to a bench that reflects the community.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court justice. She frequently writes on the law.

Emily Jane Goodman is a New York State Supreme Court JusticeÂ

Saving New York's Middle Class

A white child being raised in Manhattan is likely to be treated to some of the finer things in toddlerhood - high-end strollers, swank birthday parties and designer label clothes. After all, he or she is ensconced in a family where annual income averages almost $285,000, the New York Times reported, which means "these toddlers are growing up in wealthier households than similar youngsters in any other large county in the country." The borough's other kids are not as quite as materially well off; the average black family withchild under five in Manhattan has an annual income of $31,171.

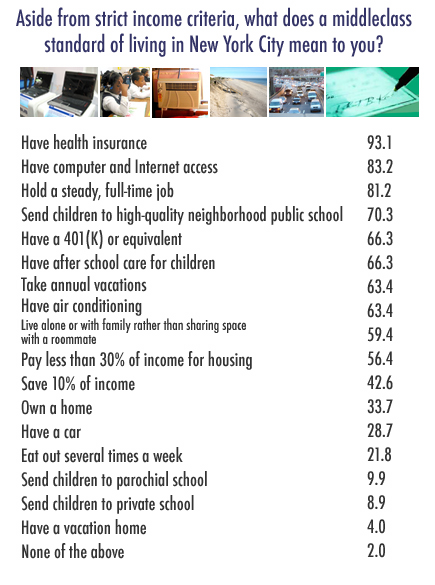

What about the people at neither end of this huge disparity - the middle class? Are they disappearing from New York's communities, even in the outer boroughs that for decades were their bastion. Some say yes - and have research to back them up. While the economy shows many signs of strength (see related story), a 2006 study by the Brookings Institution concluded that New York City had the smallest proportion of middle-income families of any metropolitan area in the country. And a new study by the Drum Major Institute (in pdf) found that most New Yorkers believe it is harder to enter the middle class today than it was just 10 years ago.

Last month the Drum Major Institute held a conference to discuss whether the middle class dream can survive in New York. A number of prominent New Yorkers described what they saw as the problem and offered some solutions.

The following are edited transcripts of some of those comments.

Reviving the American Dream

By Mario Cuomo

Aristotle recognized the importance of the middle class thousands of years ago. And it thrived in the 20th century. But today, the former governor says, growing disparities in wealth make it hard to survive on what most people would consider a middle income.

The Winners and Losers

By John Mollenkopf

The rich are getting richer, while immigrants, particularly Hispanics who recently arrived in the city, are clustered at the bottom of the economic ladder. The political scientist examines the numbers.

What Happened to Our Middle Class?

By William Thompson

Looking at the shrinking middle class, the city comptroller blames a number of things, including rising housing costs and a changed job market.

How to Speak to the Middle Class

By Anthony Weiner

The city government seems to be ignoring the concerns of many New Yorkers, says the congressman, who thinks politicians must convince these New Yorkers that they understand their problems and will work to solve them.

Invest in Neighborhoods

By Adolfo Carrion

To keep people from moving out of New York, the Bronx borough president says the city must invest in housing, health and, above all, education.

Cutting Taxes, Preserving Communities

By John Liu

New Yorkers have a right to expect government to meet some basic needs and preserve a degree of stability, the city council member says.

Reviving the American Dream

By Mario Cuomo

This topic of the middle class is a vital one, not just for New York, but for the nation. It is badly under appreciated in today's political campaigns. I don't feel that people are eager to address it and to identify the hard questions and answer them.

Part of that might be semantic. It is hard to define what middle class is, although it's been a demographic and a political reality for more than 2,500 years. Plato's student, Aristotle, described society as having three parts: the rich, the poor and the people in between, who he referred to as the middle class. He said a strong middle class would be indispensable to a well-ordered society. It would help protect against the domination of the rich and the desperation of the poor. The middle class' strength would come from its numbers and its intense desire to achieve a good life, by working hard, forcefully advocating for adequate compensation for its labors and fighting for the opportunity to own property.

That was 2,500 years ago. But middle class is still difficult to define.

Some people go to numbers. Lou Dobbs uses income numbers -- $26,000 to $150,000 is middle class to Lou Dobbs. But numbers depend on where you are and what other circumstances surround you when you are there.

Fifty thousand dollars and a lot of overtime in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, may be pretty good income. But if you're a single parent with two school-age children looking for an apartment in Manhattan, the definition is dramatically different. Now in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, you could have a one-earner family, as we did, with a spouse who stayed home and raised five kids in a Cape-Cod house in a safe neighborhood in Queens with good public schools and convenient emergency rooms that were free with a new car every two years a $30,000-a-year income. In those years, you could expect to earn more than your father did because the labor unions and the economy saw to that. The mobility was upward.

Given all the variances of the middle class, I've decided to stay with my own definition. It's closer to Aristotle's than anyone else's. Here it is: The middle class is made up of people who aren't rich enough to be virtually free of economic concern, nor poor enough to warrant any subsistence payment from the government or from charity. They are people who work for a living because they have to, not because some psychiatrist told them it's a good way to fill the grim interval between birth and eternity.

Some of them are two-parent families, one-parent families, and some of them single. There are police officers, firefighters, nurses, emergency responders, teachers, secretaries, bus drivers, taxi and limousine drivers, and clerks. Without these middle-class New Yorkers, we could not have built, operated, or survived comfortably in what is now the greatest city in world history. And if these workers are not adequately paid and otherwise reasonably accommodated, the quality of our city's life is sure to decline.

How is the middle class doing today? You'll find arguments that say, "Oh you shouldn't say that the middle class is in trouble. So many wonderful things have happened in the middle class." That is absolutely true. They live longer. Home ownership is up. More people seem to drive new and expensive cars. In my era, there were jalopies everywhere. But not now. Everybody seems to have a reasonably new car. They all own computers and flat-screen televisions. They fly across the country, and they call relatives overseas regularly. All these things are now taken for granted. In my days, we would have thought of them as the prerogatives of the very rich.

On the other hand, despite all of those advantages, the middle-class prosperity level is lagging badly. The economic balance in our country has become radically skewed by gross disparities between the extremely rich and the rest of the population. Of course, in market system, there are going to be winners and losers; that is obvious. But this disparity goes far beyond what is inevitable in a market economy. And as a result of this disparity, the stability of this society that Aristotle hoped for and that my family and I lived is threatened. Perhaps dangerously so.

Today a CEO is paid 420 times what the workers are paid. Some say that is not really a lot: The corporations are so large now that hundreds of millions of dollar in salary to run them is not a lot. Well, it is a lot to a worker. When I was living in the period of the American Dream, that ratio was closer to 20 times.

Today, more Americans than ever average a million dollars a year in income. There are more billionaires than ever. And a lot of that has happened recently. That is all good. What is not good is that they are only the top one percent of the taxpayers.

At the same time, the number of poor people has grown significantly. And middle-class firefighters, police officers, sanitation workers are forced to live outside the city because they cannot buy a house or pay the rent in an area where they think the public school is good enough. A lot of them who love this city and love their jobs find that they have to get rooted in the suburbs.

We are having difficulty finding teachers to teach the skills that our high-powered economy demands at the kind of salaries our city supposedly can afford. For how long will we be able to ask our young men and women to risk their lives as police officers for a meager starting salary of $25,000 a year before taxes?

Our society is wonderfully rewarding for high-level executives and investors but punishing workers of moderate or low skills with the cost of everything the middle class needs most: housing, education, healthcare, retirement security, transportation. The prices of all these things are going up faster than their wages.

The distinguished analyst, Kevin Phillips, one of my favorite Republicans, wrote in 1994, "The fragmentation is incredible. And I'm a Republican, I'm a conservative. This is bad and it has to be stopped." For years I said, "Kevin, you have to write another book because it is getting worse." He said, "Nobody's listening, nobody cares, nobody believes it. Somehow the country's been conned into believing everybody is better off. They don't understand that there are no savings.."

So Phillips wrote a second book recently, Wealth and Democracy, and he said this: "The current of extreme economic disparities are simply not sustainable without serious damage to the country's productivity patterns and performance."

I agree. What then must we do to help stabilize our society by strengthening our middle class? We have to provide current middle-class New Yorkers with an opportunity to earn a good life while making room for the poor.

We have to prepare middle-class New Yorkers for life in these challenging days and we have to protect them from serious threats to their welfare. How do we protect them? Give them education. From pre-K to the end of their life. You can't stop because the world is changing rapidly and the complexity is growing.

It's fun to learn and to stay with the wave. That's what's necessary.

We are nowhere near doing what we have to do with education. How many years ago was it that this country decided that, in order to be successful as a nation, you'd have to have a certain minimum level of proficiency at reading, writing, and things like that? If you depend on the market, then only the rich people are going to get an education.

What about Mario Cuomo in south Jamaica, Queens, whose mother and father cannot read or write and were broke with a little grocery store that was not working? What do you do for him? Public schools. To when? Age 16, high school. Why? Because we need it. For what? For the good of the country.

Mario Cuomo was governor of New York State from 1983 to 1994.

The Winner and Losers

By John Mollenkopf

There is an economic paradox in New York City. In some ways, the city is prosperous: There are gains in employment, higher than average incomes, rising prices for housing and a construction boom. At the same time, the numbers of people on the bottom and on the top of the income distribution are growing, and New York City's middle class is shrinking. The income distribution in the city is growing more unequal over time. And yet, we do not feel the level of class resentment that might be thought to be inevitable from the income distribution numbers.

Over the past three decades, New York City's employment numbers have fluctuated between 3.2 million and 3.8 million jobs. And the fiscal health and prospects of the city have ridden the rollercoaster of employment. We have experienced three steep drops in unemployment since the 1970s. There was the fiscal crisis in the mid 1970s when the city was in dire financial shape. We grew our way out of that into the late 1980s, but then we experienced a second recession, even sharper in some ways than the previous one. We once more worked our way out of that and reached a peak of employment in 2000. The city had a third - also sharp, but less deep - dip in the economy after September 11, 2001. The city has recovered in many ways, but we still haven't made it all the way back to the peak numbers.

Despite these fluctuations in employment, if you add together all the money of all of the people who work in the city, as reported to the state unemployment insurance system, New York has experienced fairly steady growth. There has been an even sharper rise in the annual average wages by the people working in the city. In other words, even when employment dips, people don't necessarily earn less money.

All of these numbers point to upward growth in the total amount of earnings, the amount of money that people have in their pockets. These measurements of the city's economy give us an image of prosperity.

Of course, there are problems with these numbers. People don't always accurately report their income to the government. And these numbers do not take into account what people must spend on housing, health care or other expenses that have increased as well.

If you divide the residents of the city into five income brackets and then look at the number of people in each category, you see a picture of the city's changing class structure.

Between 1990 and 2005, the number of people in the bottom two-fifths of income grew substantially. The number of people in the third and fourth brackets of income decreased. And the number of people in the top one-fifth in income stayed about the same.

And if you look at how much New Yorkers in each bracket earned, you will find that the fruits of the economic prosperity that the city has experienced over the last 15 years is concentrated at the top. If you looked at the top five percent, or the top one percent, or the top one-tenth of one percent, you see that each of those refined groups was receiving a more and more disproportionate share of the growth in income.

Anyway you look at it -- and there are hundreds of ways to look at income distribution and how to define the middle class -- we are seeing a growth in polarization or more unequal income distribution. In particular, the top part is growing, relative to the others, not only in terms of how many people are clustered there , but also in how much of the gain they have gotten. In terms of income and the share of wealth, those at the top are pulling away from those in the middle and bottom.

So why isn't there more anger in the streets?

The number of white households, which are generally on the top, has been declining and shifting toward the upper end of the distribution. To a lesser extent, this is also true of people in households headed by native-born African-Americans and native-born Hispanics. While blacks and Hispanics tend to be toward the lower end of the income distribution, their overall numbers are also in decline. And lower-income blacks and Hispanics have been moving out of the city. Native-born poor people are moving out over time to places where they do not face competition from immigrant, low-wage workers who have been flooding into New York City.

The low-wage workers who have been flooding into New York City in recent years are immigrants. But if you look at the other immigrant groups and classify them by race, the immigrant groups are fairly evenly divided across the income brackets. Many of these people are poor, but many are middle class and even upper class. The one group that really stands out as not fitting that pattern are people living in Hispanic immigrant households. They are clustered at the bottom of the economic ladder.

John Mollenkopf is a professor of Political Science and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center and director of the Center for Urban Research.

What Happened to Our Middle Class?

By William Thompson

When I graduated from college in 1974, I came back to live with my parents in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where I grew up. I was not making a lot of money at the time, but within six months, I got my own apartment in Brooklyn Heights. Within a couple of years, I was able to get a new car and the insurance for it. And I had a little money in the bank.

Fast forward to today: When my daughter graduated from college in 2001, she moved back home as well. But she couldn't afford to get her own apartment. She couldn't afford to get a car, much less pay the insurance on it.

That, to some extent, is an example of the plight of the middle class.

The American dream is that your children's lives will be better than your own. But that is getting harder to achieve. In New York City, we all strive and want to do well, but over a period of time, you look at almost the barbell effect, with both ends -- lower income people and higher income people -- expanding, and those in the middle being squeezed.

A combination of factors is responsible for this.

Housing is one key issue. Costs are up, property values have driven up rents, and the number of affordable apartments in programs like Mitchell-Lama is dwindling. New Yorkers, particularly those in the middle-income brackets, are scared of being priced out their own neighborhoods. They've lived in their neighborhoods for decades - when times weren't good they stayed - and now they may not be able to survive the good times.

Another contributing factor is the changing workplace. In the past, part of the American dream was to work for a corporation. People were loyal to the company. You used to be able to work for a corporation and expect that if you did a good job, you would be there for a lifetime. That doesn't exist any longer. Over time corporations have become less loyal to the people who work for them.

People used to be able to earn a modest salary, take a couple of weeks vacation each year and have a retirement plan. For many, those things are disappearing as well.

There is a rise in the number of self-employed people. In the last seven years, 210,000 individuals moved into the ranks of the self-employed. It is part of the future of the city, but there are also problems like health insurance that we have to confront.

Manufacturing jobs have left and gone overseas, not just in New York but nationally. We're not getting those jobs back. We need create different types of jobs you create and built other industries.

New York also did away with residency requirements that mandated that those who work for our uniformed services live within the city limits. Those middle-class workers -- police officers, firefighters, teachers and others -- now live outside of New York.

All of these factors contribute to a shrinking of the middle class, but there are ways that we can work to address the issue.

Small business across the city is going to be an area of growth. We must create access to capital, through micro loans and small-business loans. We have to change tax regulations that prevent the growth of small businesses across the city, like a reduction in the unincorporated business tax. It is something that we need to continue to focus on in the future: to create and spur small business growth across the city, and particularly outside of Manhattan.

The massive housing programs of the past, like Mitchell-Lama, are evaporating. The Bloomberg administration has put more focus on affordable housing -- and the tag "affordable" isn't on just for the low end, it's across the spectrum. But we need to do more in the area of affordable housing -- different and unique programs to help bring people back to the city. We need housing growth in all five boroughs.

Education is another factor. We need to continue to improve our education system, and offer middle-income families, and all families, greater opportunity.

One of the best things that is happening in New York City in the last five or six years has been the stability, growth and attractiveness of the city university. There have been studies that say that, as higher education systems go, so goes your city, and so goes the middle class. Elementary and high schools have always done better than middle schools. That is where you need to create a major focus. Some middle-income parents are here through elementary school and go some other place because of middle school. If you stabilize your middle schools, you keep those families here for the entire school career.

We need to maintain our public transportation. The Long Island Rail Road, for example, is at 100 percent state of good repair, and Metro North will take another seven years to reach that standard. But New York City Transit is 25 to 35 years away from being in a state of good repair. We have to able to move people around the city - not just move people into and out of the city from the suburbs.

William Thompson is New York City comptroller.

How to Speak to the Middle Class

By Anthony Weiner

You could say, without fear of contradiction, that New York City is the financial capital of the world, although there has been some conversation about whether we are losing that edge. We are the entertainment, creative capital of the world. And up until rather recently, you would have said we were the middle-class capital of the world. When you thought of the iconic middle-class family, you would think about New York. But it is not an overstatement to say that New York is not a place that you go anymore if you are middle class or trying to make it into the middle class.

You get a call from a friend who says, "I just got a great job. Seventy-five thousand dollars working at a local law firm. Tell me a nice place I can go to set up shop and raise my middle-class family in New York City."

It would not be anywhere in Manhattan. It would be fewer and fewer places in the outer boroughs. Think about saying, "Uh, Jersey City? Hoboken?"

One of the things that is most troubling to me is that it is very hard to point to anything that the city is doing to address this. If you need evidence of that, just look at what Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who I think generally has done a pretty good job, points to as proof of how well the city is doing. He points out is how the property values are up.

That is undeniably a good thing. But you have to understand on a fundamental level that that rise in property values makes many New Yorkers deeply insecure about their fate, even if they live in one of those homes that have gone from $300,000 to $600,000.

Mayor Bloomberg has characterized New York as a luxury product. But you cannot sustain any economy if you do not have an affordable place in economy for those who provide the services. Even if you own a yacht, you need somebody to swab the deck and cook the meals. Even if you own a beautiful home, you need someone to maintain it. You need someone to patrol the streets and collect the garbage.

Part of our problem is that we in elected life don't talk to these families in a way that they care about. We are not engaging middle class families. When I talked in 2005 about giving the middle class a tax cut and asking that those who make more than a million dollars pay a little more, people responded because it was something they could understand.

When somebody sits at the table with their daughter, about to send her off to their local public school, they are not thinking about the nuances of the reorganization of the school system. They want to know that their daughter will have an experienced teacher, that she is getting some face time with that teacher, that she is in a safe school where discipline means something.

Part of what we're doing is selling to New York City residents and the middle class is that we in government understand their plight. We need to say to middle-class families, the families that we're trying to make stay here in the city, "We understand what you're thinking."

Let me give you a brief example: This year, did you see the announcement of how many Westinghouse scholars we have? You didn't, because the education department did not release the numbers. They haven't for the last three years because there has been a precipitous decline.

Now, most middle-class kids do not get Intel scholarships. Those are the most brilliant kids imaginable. But what those scholarships do is say to the middle class that the public schools are an aspirational place.

You want to know if these new, younger teachers can still get it done like the more senior teachers who have aged out like my mother. Gifted and talented? It's a fight every year to get them funded.

We have been so obsessed and focused on the big businesses in Midtown that we have forgotten that about 60 percent of job creation has come from small businesses in the outer boroughs. Yet we do very little to address their concerns. We need to do things like help small businesses pool together to provide health insurance.

What keeps me up at night, and perhaps the reason I pursue these issues with a little excess of passion, is the idea that my middle-class family story -- father who went to college on the GI bill, mother a civil servant, me in public schools -- can't be repeated. My fear is that we are tiptoeing up to a tipping point where anybody who is able to take their kids out of public schools will have done it and where anyone who is thinking about coming here will decide that they can't. We have one priority among all others, and that is to make sure we stay safe. And thank God we have stayed safe. But the close second is making sure this city is hospitable in for creative energies, for ambitious energies, for those entrepreneurial energies of all economic stripes.

Anthony Weiner represents part of Brooklyn and Queens in the U.S Congress. He ran unsuccessfully for mayor in 2005.

Investing in Neighborhoods

By Adolfo Carrion

The fact that 300,000 of the highest income earners in our country earn the equivalent or more of the 150,000,000 Americans at the bottom is astounding and worrisome. The problem is not unique to New York, it is across every urban center. New York's problem is one of having abandoned a large sector of the population that is crafty and hard working and tends to figure things out on their own and doesn't necessarily rely on government or see it as a crutch.

If we don't pay attention to that sector it could be the beginning of the end. The real New York and the life of New York plays out in the hundreds and hundreds of neighborhoods across the city where people pay mortgages and shop for good schools, where they're concerned about basic issues like transportation, traffic in their neighborhoods, and the businesses in their neighborhoods, and the regulatory maze that they have to live with everyday. That's what regular New Yorkers and that bleeding middle class, that hemorrhaging middle class, is worried about.

When Ed Koch was mayor, he made a decision that was unpopular at the time, especially with some members of the City Council. He said, "I'm going to take $5.2 billion of city capital funds. We're going to fix our own problem, we are going to invest." As a result, we created neighborhoods all over the city and restored neighborhoods that had been devastated by the policies of the 1970s and '80s. Now you go to some neighborhoods, and there are people owning homes, raising their kids. They own a little patch of green.

Do we need to support tourism? Absolutely. We get 44 million people coming to this city. Entertainment, hotels, the theaters, all the tourist attractions. The financial sector is critical. Of course Manhattan is critical for us, and we need to ensure that it works. That's the heartbeat of the region. But we have to pay attention to our most important asset, which is working families that are ultimately generating those little bambinos that will become good, strong, participating citizens in this free market and this free democracy.

The middle class, aspiring family is simply shopping for a good place to live where they can raise their family and do better in the future. The players in that game are the public sector and the private sector.

On the private sector side, we try to create the platform for good economic activity that churns out wealth and creates jobs. Then we try to encourage the banking community to move money out into the economy. On the public side, we try to create a monetary policy that says, "Ease the cost of money and keep it flowing." So we manage the interest rate. And we have the challenge of whether or not we are really going to invest in the building blocks that matter. We need to have a conversation about return on investment.

To build a stronger city that is friendly to the middle class, we have to make some structural changes. Our tax policy and structure needs to be progressive. We need to continue to plan very aggressively for the hundreds of neighborhoods that are imbalanced right now, and we need to ensure they are going to be nurturing communities for families. We need to turn the conversation to return on investment and invest in the building blocks.

It is not a burden, and it is not charity to support public education, public health care and investment in housing. Housing that is subsidized is not a giveaway, it's an investment. It's a platform for people to move up. And we need to have a five-borough economic development strategy that is also very aggressive.

But the single most important issue that is still unresolved for us is education and the quality of that education. People are shopping with their feet and their dollars for education in suburban communities because they know they can get a bang for their buck there.

Adolfo Carrion is Bronx borough president.

Cutting Taxes, Preserving Communities

By John Liu

We have to figure out a way to give people in the middle class or who strive to be in the middle class good places to live. That means good neighborhoods, whether they are in the form of apartment buildings or low-density residential neighborhoods. We need to provide affordable housing and, at the same time, we need to keep the character of some residential areas intact, whether they are in high-density Manhattan or low-density areas in Queens or other boroughs. And at the same time, we have to keep jobs because the middle class need places to earn decent incomes. And we need to give people viable ways to get to and from their residences and their jobs -- good public transportation that will discourage people from driving their cars and adding to congestion.

There needs to be a tax reduction. Property tax, as well as income tax. If we are really facing surpluses, then we should be rolling back the rates, just as in times of deficit, we found it necessary to increase rates. In surplus times, we have to roll back the rates in the income and property taxes, and if possible in the sales tax as well.

Even if we are able to reduce tax rates just minimally, it is still necessary. We should not discount that. The cuts send a message that government understands it has to be lean and mean. We should not take more from people than is absolutely necessary.

At the end of the day, the middle class in New York City understands that taxes are going to be high. It's always been that way in a city like New York where we have such great diversity.

Health insurance for the middle class or the aspiring middle class is obviously critical. There are many new American immigrants in New York City who either have attained or are close to the middle class, yet have no insurance. Many of them are entrepreneurs or work for very small businesses. They have to go out into the marketplace and pay exorbitant premiums for individual or small group coverage. This is something that requires a state, and ultimately, a federal policy.

People want to stay in New York. They want the reasons to stay in New York. Over and above the tax rebates and the renters' rebates, or the tax reductions, the middle class and the aspiring middle class would like to see predictability. That means knowing that the neighborhood where they live will be stable, that there will not be illegal conversions next door. That the neighborhood character will stay the same because that's what they expected from the zoning code. That their schools will be effective and will educate their kids or their neighbor's kids. And that those kids have a way to get safely to and from school.

They want to be sure that the city or government is not selectively and arbitrarily enforcing laws that may not be effective. When someone goes to work for the entire day and comes back to find a $100 sanitation fine because a cup that was blown and landed in front of that person's house, that enrages the middle class person living in this city.

John Liu is a member of the City Council and heads the transportation committee.

Â

The Council's Budget Response

The public library on East Broadway and Catherine Street doesn't open until noon on Thursdays, so the City Council had the run of the place last week when it showed up on Thursday morning to present its official response to Mayor Michael Bloomberg's preliminary budget.

Libraries are almost always a major bargaining chip in the annual budget negotiations -- and this spring will be no exception. When times are tough, libraries are usually asked to absorb cuts. Now, with Bloomberg estimating a $4 billion budget surplus, the council wants to increase funding for libraries by tens of millions of dollars.

The big-ticket item in the budget was Council Speaker Christine Quinn's tax credit for renters. [To read more about the tax credit craze, click here to read Many Ways to Spell Tax Relief.] Overall, the council wants to add $300 million in tax cuts and new initiatives, while also restoring $266 million in existing programs left out of the mayor's budget.

But the council is also trying to shed its reputation as the city's spendthrifts. Quinn accompanied the new spending and tax cut proposals with plans to cut wasteful spending in government agencies, and even to end some programs that the council itself started. Her presentation mirrored the mayor's, as she warned that the good times will not last forever, and that city officials must plan for leaner years ahead.

Overall, the council's budget is $61 million larger than the mayor's.

This is the council's first offer, and Quinn said that she doesn't expect conflict with the mayor. That will be seen in the coming weeks, when Bloomberg will release his executive budget and the two sides begin to wrangle over the details. If past years are any indication, this process will end in the wee hours of an evening in late June.

THE SIZE OF THE BUDGET

The council and the mayor disagree on how much money the city has to spend.

The council predicts that the city will receive over $600 million more in taxes than the mayor has accounted for. Such differences are common -- Mayor Rudolph Giuliani has boasted that he intentionally underestimated tax revenue to keep spending down. Quinn does not Bloomberg of such chicanery, but she does say that the council "almost always projects more than [the mayor], and we're almost always right."

In recent years, at least, this has been the case, according to the Independent Budget Office.

HOW THE COUNCIL WANTS TO SPEND MONEY

The council budget response includes $258 million in new tax cuts and $45 million in new spending initiatives not included in the mayor's preliminary budget. It also proposes spending more money to prepay expenses for the next year.

Housing Initiatives: The main initiative in the council's budget response is a $300 tax credit for renters. Two-thirds of the city's residents live in rental housing, and more than half of them pay at least 30 percent of their income on rent. Rents rose when property taxes were raised after 9/11. Renters, however, have not benefited from the tax rebates that homeowners have received over the last several years.

Quinn's rebate would be given to families that rent and make less than $75,000, and individuals who make less than $43,000. It would cost the city $261 million. She describes the plan as an extension of the mayor's tax rebate for property owners, which the council's budget response officially endorses.

The mayor has withheld judgment on the credit, saying it will be discussed in negotiations. Some critics argue that a renters credit will further distort the city's housing market. Others question whether $300 will make a real difference in renters' lives.

"It's a tease," said Councilmember John Liu. "And it's something I support."

The council is proposing several other housing initiatives.

It wants to make more people eligible for a program that helps first time homeowners with down payment and closing costs, known as Renters to Owners Opportunity Fund, or ROOF. The council wants to raise the program's income cap from $56,000 to $92,000, which would cost City Hall about $5 million. In an attempt to avoid foreclosures, the council wants to expand the city's efforts to educate homebuyers about mortgage costs and other expenses.

The council would add $25 million per year to the capital budget to subsidize the renovation of "distressed" affordable housing owned by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. This housing would then be transferred to private owners who would guarantee that the apartments would remain affordable.

Full Day Pre-Kindergarten: The council wants to spend $10 million in fiscal 2008, increasing to $13 million by fiscal 2011, to fund full-day pre-kindergarten classes. This would provide 2,100 spots for full day classes in the coming fiscal year.

Increased Hours for Libraries: The council is calling for all public libraries to be open for six full days each week. The council plan would reach this goal within three years, at a cost of $47 million over that time.

HOW THE COUNCIL WANTS TO SAVE MONEY

Agency Cuts: The council plans to save almost $400 million by readjusting spending for agencies that have overestimated their costs. In addition, it is proposing cutting another $22 million from the Department of Education, the Human Resources Administration, and the Department of Housing Preservation.

About 80 percent of the council's agency cuts would come from the Department of Education, whose budget would shrink by $17.9 million. The savings would come mainly by removing staff from the Panel for Educational Policy, an advisory board that is supposed to review policy changes. The panel is toothless -- when several members opposed the mayor's plan to end social promotion several years ago he simply forced them out. Yet the council claims that it has grown in size in recent years, and now has funding for 14 full-time staff members. It wants to redirect that money to classroom uses. The mayor says that these employees do not exist.

The council wants to cut the Human Resources Administration's budget to combat welfare fraud, arguing it has less work to do with the welfare caseload at it lowest point in 40 years. It would also end the Narcotics Control Unit at the department of Housing Preservation and Development, arguing that the police department can now handle this responsibility.

Ending Unneeded Council Programs: The council is also willing to cut some programs it has championed in the past. It has identified $6.2 million in "potential initiatives that may not need renewal." These range from $2.2 million used to combat hepatitis B among Asian Americans, to a $900,000 tennis league, to $50,000 used for a program to count youth runaways.

Within the context of a $57 billion budget, $6.2 million is hardly significant. But Speaker Quinn says that the council's eventual goal is an annual review of all council programs to determine whether they are effective. She cautioned that such thoroughness was still on the horizon.

"We're in the first stage of that overall," she said. "This is the first first stage."

With the exception of the education panel, the mayor responded positively to Quinn's proposals.

"One of the things that I was pleased to see in her budget was that she did have some money saving ideas," he said. "Whether those are the ones will be appropriate when everybody gets together and looks at them I don't know."

SIGNS OF REFORM?

Since she became speaker, Quinn has made reform of the budget process a priority. Last week, the council claimed a victory in the effort to eliminate the process by which the mayor takes items out of the budget knowing that they will be restored, known as the " budget dance."

In his preliminary budget, the mayor included permanent funding -- an action that budget watchers refer to as "baselining" -- for various arts, parks, and cultural programs that have been used regularly as bargaining chips in the budget dance. But the council still identified $266 million in programs that they want restored and baselined in this year's budget.

In another reform taking effect this year, the city's budget will include the names of the council members who requested member items, which are grants for local projects backed by individual legislators or groups of legislators. On all levels of government, such grants are derided as pork barrel funding, and there is a move to hold lawmakers accountable for pushing for this funding.

The theory behind increased disclosure is that it will lead to more responsible spending by forcing lawmakers to answer for their decisions. Dick Dadey of Citizens Union (whose sister organization, the Citizens Union Foundation, publishes Gotham Gazette) said that such changes are already being seen in the moves by the council to stop funding its own unnecessary projects.

"They're rightfully preparing to say that not everything we've funded behind closed doors should be funded with the doors open," he said.

Â

The Many Ways to Spell 'Tax Relief'

|

Defining the Terms Tax credit: A dollar-for-dollar offset of a tax obligation. A couple might have a personal income tax bill of $1,290. With the newly increased state personal income tax credit of $290, they would pay only $1,000. Some credits call for taxpayers who owe no tax to get a check for the amount of the credit. Tax rebate: A dollar-for-dollar return on a portion of a taxpayer’s obligation, it is basically a temporary tax credit, often issued as a check directly to the taxpayer. It is the big political ingredient in the changes in the School Tax Relief, or STAR, program. Tax deduction: A subtraction from a taxpayer’s total taxable income. While this reduces the tax bill somewhat, the amount saved depends on the specific taxpayer’s tax rate. Governor Eliot Spitzer proposed a $1,000 tax deduction for households that send their children to private or parochial schools. This would have meant that a family with $50,000 of state taxable income would pay taxes on only $49,000. At a tax rate of five percent, the savings would have been only $50. The bid failed, largely because the Democratic State Assembly saw it as a means to provide public funding for parochial and private schools. Tax exemption: Property or income not subject to any tax. The STAR program depends on tax exemptions. At least $30,000 of home value (and much more in higher some high priced areas) is exempt from local property taxes, saving the taxpayer whatever the local property tax would have been on the $30,000 or more. Seniors get higher benefits. |

As New Yorkers rush to file their tax returns by April 17, city and state officials have been assembling a crazy quilt with every form of tax relief: tax credits, deductions, exemptions, rebates, tax rate reductions. While Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the City Council negotiate over several proposed tax relief plans, including a tax credit for renters (see related story), Governor Eliot Spitzer and the State Legislature have agreed on a plan to reduce taxes that illustrates the complexities and problems associated with political tax doctoring.

CITY RATE CUTS, CREDITS AND REBATES

In his 2008 preliminary budget, Bloomberg offered several plans to ease taxes. One highlight is a five percent, across-the-board cut in the city’s property tax rate. This will cost the city $758 million in revenues in 2008 and $941 million in 2011, according to the Independent Budget Office. This alone represents about one-quarter of the projected $3 billion a year deficits for 2009 through 2011.

Bloomberg also proposes a four-year extension of the current $400 property tax rebate for homeowners at an additional cost of $256 million a year. The rebate serves as a temporary tax credit and gives the mayor the enviable political task of writing a city check to every each homeowner. Permanent tax credits, on the other hand, get lost in accountants’ work sheets, and their creators go unremembered.

The mayor also proposes several traditional tax credits that would provide tax relief to a narrowly defined group of taxpayers.

The childcare tax credit is one. It helps only families that that earn less than $30,000 and have children under the age of three. The maximum benefit would go to families with incomes of $15,000 or below, providing them with as much as $1,155 per child. Families earning $15,000 to $30,000 would receive lower benefits on a sliding scale. The mayor estimates that 49,000 city families would benefit, at a cost of $42 million in 2008 and $45 million by 2011. The tax credit would take the form of a refund if the family owed no personal income tax.

The mayor has put forther two other tax credit proposals, both aimed at smaller businesses and partnerships. Some business owners now essentially pay taxes twice on the same income -- once in the business tax and then, when the money shows up as part of their income, through the personal income tax.

Earlier changes eliminated this for more than 20,000 businesses with relatively low incomes. This year, the mayor wants to expand that. Resident sole business proprietors and partners with taxable incomes of $42,000 or less could take a credit for 100 percent of their business tax, in effect eliminating that tax for them. The percentage declines for those with higher incomes.

This new credit would cost the city $30 million -- a little more than the mayor anticipates -- the IBO estimates, and would benefit some 21,000 businesspeople. The IBO also estimates that 86 percent of the benefits for the calendar year 2007 would go to people earning more than $142,000. (This change does not require state approval.)

The mayor’s second proposal recycles a measure that was adopted in 2002 but failed to get the necessary state OK. Similar to the tax credit for business owners, this would let resident shareholders of small businesses eligible for certain federal and state tax benefits -- known as subchapter S corporations -- take a tax credit for some of their city corporate income taxes.” (For more on these tax changes, see the IBO analysis of the mayor’s preliminary 2008 budget.)

The estimated costof this change, according to the mayor, is $70 million in 2008. As with the business/income tax credit, the proposal would not apply to taxpayers who are not city residents.

THE COUNCIL’S TAX RELIEF

The City Council has also put forth its own tax breaks.

The main proposal is a $300 tax credit for renters, which would be available to families making less than $75,000 a year or single renters with annual incomes below $43,000. The council describes this credit as an extension of the mayor's rebate for homeowners, which provides relief to New Yorkers who saw their property taxes increase after 9/11. While renters don’t pay the property tax directly, its cost is reflected in their rent, so, the reasoning goes, they also are entitled to some kind of break. But the council credit has one sharp distinction from the homeowner's rebate. While the mayor’s rebate gives all homeowners -- regardless of income -- $400, the council ties its credit to income level.

The council wants to give tax credits to businesses that hire welfare recipients, former felons, or people with physical or mental disabilities. It also would like to increase the city's Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income workers.

TAX RELIEF FROM THE STATE

The main tax change in the new state budget, passed on April Fools’ Day, is a $1.3 billion expansion of the state’s School Tax Relief program, known as STAR. This program, aimed at reducing the impact of property taxes, will now save New York State taxpayers $5 billion a year or cost the state $5 billion in tax revenues, depending on one’s point of view. As the New York Times reported, the deal on STAR includes tax credits, property tax exemptions and rebate checks

STAR sets out some property tax reductions. Then the state reimburses the local taxing authority, usually the school district, for what it has lost in property tax revenues because of STAR. Last year, though, the state started sending some of the property tax savings to the homeowners directly in the form of rebate checks. These rebates will double with the new STAR budget. Although touted as a middle-class homeowner tax-savings program, benefits can go to households making up to $250,000.

New York City does not fare as well under STAR as other jurisdictions. In 2007, it got about $1 billion in reimbursements for lost personal income tax and property tax revenues, according to the Independent Budget Office -- far less proportionately than many other governments in the state receive. This is because STAR is targeted at lowering property taxes for homeowners, and a smaller percentage of city residents own their homes than people in the rest of the state. Also, the average property tax burden in New York City is much lower than in communities outside the city.

In addition, residents of the city receive less tax relief from STAR, again because of the lower property taxes and percentage of homeowners in the city. But city residents do pay a local income tax. And so to provide them with some tax relief, the state budget deal increased the personal income tax credit for people filing a joint return from $230 to $290. The credit on an individual return will go from $115 to $145.

Clearly STAR has a pro-suburban/upstate bias. And some critics charge that STAR may actually serve to increase property taxes. “The reason for this,” the state comptroller’s office has written, “is that STAR lowers the effective tax rate on homeowners - the largest group of people who vote on and otherwise influence local school budgets…. By reducing the local tax share paid for greater school spending, STAR actually provides an incentive to increase school spending.”

As a result, Edmund McMahon, director of the Empire Center for New York State Policy, has written, “It’s an inefficient use of funds that basically encourages what it’s supposedly trying to fix.”

That indicates the kind of pitfalls that can confront politicians who play the tax relief game. While some remedies, such as the city childcare tax credit and its two business tax credits, are tightly targeted, relatively inexpensive, and serve specific social or economic goals, the same cannot be said of many of the other tax relief proposals. Tax policy provides fertile ground for politicians, but they would do well to be wary. Often their approach offers only short-term answers to long-term problems.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.

Tax Cuts For Tenants And Other Budget Debates

The city’s spring budget process looks to be an especially interesting one, as substantial proposals get debated at City Hall.

Tax Cut Mania

It is no surprise that New York City carries by far the biggest tax burden of the nine largest cities in the United States. According to a study by the Independent Budget Office, New York’s taxes are 47 percent higher that the average for the other eight cities. Taxes took $9.02 out of every hundred dollars of taxable resources in New York City in fiscal year 2004 ($5.62, local and $3.40, state).

Though Mayor Michael Bloomberg responded quickly with a defense of the city’s high taxes, saying that New Yorkers want and get more services than other cities, both sides of City Hall are flush with proposals to cut taxes.

In January, the mayor proposed a $1.3 billion tax reduction plan that includes a five percent property tax rate cut for all residential and commercial owners, another year of $400 rebates for all homeowners, and elimination of the four percent city sales tax on all clothing.

In February, City Council Speaker Christine C. Quinn proposed her own tax cut in her State of the City address, with a plan to give working-class and middle-class renters (i.e., families of four making $75,000 or less) a $300 tax credit. Initial reports suggested such a credit would cost the city approximately $261 million in lost city revenues (which roughly matches the annual $256 million cost of the $400 homeowner rebates). Those lower-income renters who could not use a city tax credit (because they earn too little to pay any city income tax) would get a $300 check from the city.

Rainy Day Fund

The city’s $3.9 billion surplus has also prompted Speaker Quinn to propose creating a rainy day fund, presumably a reserve account that would be established through joint city and state legislation. The idea would be to set aside some surplus funds and then use the funds in the future to soften economic downturns and budget emergencies. Quinn said, “Families do it, businesses do it, even squirrels save nuts for the winter.”

Under current state law the city can’t do a rainy day fund. The city cannot end the fiscal year with a surplus, so it spends down some of the surplus in that year and prepays some of next year’s bills with the rest, usually for debt service. But the mayor has thus far not encouraged a joint council/mayoral plan to craft a rainy day fund, so it will be interesting to see what happens next. (As noted in earlier columns, the mayor has created his own version of such a fund -- a retirees health benefits trust fund -- that will get a total of $2.5 billion by 2008.)

The Spitzer Budget – More For NYC Education, Less For Everything Else

The March report on the mayor’s January financial plan from the Office of the State Deputy Comptroller for New York City is a useful analysis of the impact of Governor Eliot Spitzer’s proposed budget for the state’s next fiscal year (beginning April 1, 2007) on the NYC budget. The good news here is that Spitzer would send $3.2 billion in increased state education aid over the next four years ($637 million in 2008).

Added to the $2.2 billion in increased city funding over the next four years in the mayor’s January plan, that’s $5.4 billion in new education funding for city schools. According to the comptroller report, this represents “more than twice the minimum amount recently ordered by the New York Court of Appeals, which concluded the longstanding Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit.” How that huge influx of money gets spent will be one of the big budget stories during the next few years.

The bad news for New York City in the Spitzer budget proposal is that all the non-education proposals add up to a “net loss of $317 million over the course of this year and next year” to the city. The main reason is the governor’s elimination of the state’s annual $328 million in general revenue sharing funds to the city. That’s no-strings-attached, unrestricted money for the city. (Spitzer wants to focus revenue sharing on distressed communities.) To make up for that loss, the governor proposes eliminating certain corporate tax loopholes that he says will generate approximately $375 million a year in new revenues for the city.

Tax Reform – Not

Council Speaker Quinn’s tax credit for renters would make the city’s property tax system somewhat more equitable. Renters, who contribute to property taxes through their rent and who on average earn much less than the average homeowner, have not benefited from the mayor’s $400 rebate to homeowners. They would thus get some tax relief. But the new policy will also further complicate the system.

The deputy comptroller’s report, for instance, describes another example of the bizarre nature of the city property tax. Property tax collections are projected to grow from $12.5 billion in 2006 to $17.5 billion by 2011 (excluding the impact of the Bloomberg proposed tax rate cuts). The big reason is that since 2000 citywide market values have more than doubled.

But because of many complex restrictions on assessments, much of the market value increase either never gets taxed (house owners get this big benefit) or is phased in over five years (for rental landlords and commercial owners). Some $22 billion of assessments (called a “pipeline”), for example, will get phased in during future years. This helps assure future tax revenues, even if market values fall, but in the short run it denies the city current revenues, as well as maintaining inequitable distinctions among different categories of owners and renters.

Nevertheless, taxes and tax cuts are on the table, and there are competing visions of what’s fair and what’s not, at least in property tax policy. That is a good start for a broader debate about taxes in the city, and the need for more simplicity, transparency, efficiency, and equity in tax policy overall.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Putting Limits On Pay To Play

When Richard Hutchens turned his attention to the Erie Canal in the late 1990s, the famed waterway's heyday had long since passed. Still, the businessman knew a deal when he saw one -- and so he happily paid $30,000 for the development rights to 524 miles of state-owned property along the once-legendary waterway. That came to $57.25 a mile.

Hutchens was not the only developer who saw that such rights could be worth many millions. But he had one big advantage: a close relationship with several staff members at the Canal Corporation, the part of the state Thruway Authority that was selling the rights to develop the land. These friends rebuffed other bidders, fed Hutchens inside information, and hid the Buffalo developer’s lack of experience and prior failures from other officials, according to a 2004 report prepared by the office of then Attorney General Spitzer and Inspector General Jill Konviser-Levine.

Hutchens' friends also asked him to fork over more than $10,000 in campaign contributions for various candidates. In the vernacular of government corruption, Hutchens had to "pay to play."

New York's public officials have long accepted money from those with whom their agencies do business, and such donations are often perfectly legal. But quid pro quos such as Hutchens' are getting increased attention from public officials. In his inauguration speech as governor, Spitzer said he wanted to restrict such practices. Mayor Michael Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn used their respective State of the City speeches to say that they would also limit political contributions from people who do business with the city. And Attorney General Andrew Cuomo has committed his office to developing an Internet database to allow New Yorkers to track the links between political donations from lobbyists and special interests on one hand and state contracts on the other.

Hutchens' sweetheart deal was cancelled by State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, who cited ethical violations in the process. Spitzer, who was attorney general at the time, called the deal the result of "bureaucratic incompetence, cronyism, ethical lapses, and lack of oversight."

Hutchens insisted he had done nothing wrong. But, perhaps inadvertently, he acknowledged what he was doing. "Everybody makes a political contribution for a purpose,” he said. “My purpose was that I'm living in New York, and I need to be a friend, be acquainted with people that make things happen."

OUTRIGHT BRIBERY…

At its most blatant, pay to play is simply bribery and plainly illegal. One of the most notorious cases involved Guy Velella, then a state senator representing the Bronx, who sought campaign contributions and legal fees from a contractor in exchange for the senator’s support in seeking renewal of a state contract to paint a bridge. Court documents seemed to indicate that Velella engaged in many other corrupt practices as well. In 2004, the senator ended up behind bars (his imprisonment turned into a dark comedy in its own right).

Businessman Ron Laberge, who did a large amount of business with state agencies, said that bribery is standard procedure in New York State. In 2003, after the FBI confronted him with proof that he had bribed a state official, Laberge "prepared memoranda outlining the methods used by politicians and business owners to contribute money to campaigns and to have those contributions recognized for later business opportunities," according to court documents obtained by the Albany Times-Union: "This information laid out the blueprint for the FBI concerning the manner in which business is often conducted in New York."

Laberge and two other men, a state employee and a real estate broker, ended up being convicted of trading money for a lucrative lease.

…AND MORE SUBTLE PERSUASION

Laberge and Velella's crimes were particularly blatant. But the pay-to-play system is not always so obvious. Instead, good government groups say, lobbyists, contractors, and developers pressure public officials through campaign contributions. This does not necessarily result in quid pro quos, they say, but exerts a creeping influence on government decisions.

“Actors in this field are presumably shrewd enough to structure their relations rather indirectly,” Stephen F. Williams, a senior judge of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals said in a decision addressing pay to play on the federal level.

The case of State Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno serves as a possible example. Bruno is being investigated by the FBI for his relationship with a personal friend, businessman Joe Abbruzzese. Abbruzzese has paid for Bruno to fly on his private jet to Florida, where the two men played golf and visited an upscale strip club. He also contributes a large amount of money to Bruno's campaigns. Meanwhile, businesses that Abbruzzese has a financial stake in receive hundreds of thousands of state dollars in the form of state grants called member items, money that Bruno has a lot of control over. Abbruzzese is also bidding for the state's horseracing franchise.

The investigation is not complete, and both men insist that they have done nothing wrong. Bruno says Abbruzzese's business ventures should not be seen as questionable simply because the two are friends. But one thing is certain: There is a lot of money involved.

Bruno’s case and the others that make the newspapers are hardly isolated incidents. Vendors who do business with New York State donated almost $2.2 million to state officials between 2001 and 2003, with health, construction, and financial service interests being the most generous, according to a study by the good government organization New York Public Interest Research Group. During the same period, officials gave out about $26 billion in “influence-able" contracts, or contracts where price was not the primary factor in deciding how they were awarded, the group said. In addition, 15 vendors directly violated campaign finance law, giving more than was allowed.

According to a report (in pdf format) published by the city Campaign Finance Board, 22.3 percent of campaign contributions for the 2005 municipal election cycle came from people or entities that do some kind of business with city officials. Certain offices seem to attract a larger proportion of money from this group. In the races for borough president in 2001, for instance, 81 percent of contributions came from lobbyists, their clients, or contractors – even though they accounted for only 8 percent of contributors.

DOES IT MATTER?

Money flowing between officials and those with whom the government does business does not mean that anything improper is taking place, the Campaign Finance Board cautions.

"There is nothing in our data that allows us to conclude that contributions have influenced the awarding (or refusal) of any contract or other benefit," it wrote. "As such, our data do not provide direct evidence of a 'pay-to-play' culture in New York City."

But even if there is not outright corruption, the board, good government groups, and elected officials say that the perception of pay to play is damaging.

"When we look the other way while those who do business with the state give huge contributions to the officials who determine state contracts, we invite even greater cynicism in our public institutions," said Attorney General Cuomo.

Some developers are also concerned.

"When you do business with the city, you get solicited by everyone from U.S. senators down to members of the City Council," said Atlantic Yards developer Bruce Ratner in former Public Advocate Mark Green's 2004 book on campaign finance, Selling Out. Reflecting on his past contributions and fund-raising efforts, Ratner added, "I didn't want to be a person on the outs, nor could my business afford to be a person on the outs given how much business we do with government."

Despite his qualms, Ratner still plays the game. As the Atlantic Yards Report, a blog opposed to his plan for downtown Brooklyn, writes, Ratner no longer makes campaign contributions – directly. But his brother and sister-in-law both contribute large amounts to public officials who may have sway over development projects he hopes to pursue.

Not everyone, however, sees this as a very big deal.

Both the city and state comptrollers – the government's official financial watchdogs – question whether campaign contributions really influence the way that officials grant contracts and do business. Thomas DiNapoli, the new state comptroller, said he would not forgo contributions in future campaigns from those who want to do business with the $145 billion state pension that his office controls. DiNapoli did say he would limit those contributions to $10,000 or less, instead of the $50,000 that is legally allowed under state campaign finance law.

"It is important for people to run for office who are not wealthy people," DiNapoli has said.

City Comptroller Bill Thompson has also questioned whether pay to play is such a big problem. "It's a great catch phrase, but what does it mean?" he told the political blog the Politicker. Accepting a relatively small amount of money from those who do business with the government will not lead to corruption, Thompson argued. He added that the current $5,000 contribution limit for candidates for citywide office is reasonable. "I don't see pay to play on the $5,000 level," said Thompson, who is considered a strong candidate for mayor in 2009.

THE RULES OF THE GAME

There are relatively few restrictions on how public officials and candidates for office can raise money from those with whom the government does business. Money flows particularly freely in Albany, which has relatively permissive campaign finance laws.

Still, there are limits. If they personnally are running for office, state employees are allowed to solicit contributions for their campaign from a person with business before their agency. They cannot, however, direct someone to donate money to other political campaigns – a rule that Hutchens' friends at the Canal Corporation violated.

In addition, a federal rule restricts investors who buy municipal bonds from contributing to officials in charge of issuing those bonds. (They are allowed to make small donations in elections they can vote in, however.)

Many city agencies, including the Health and Hospitals Corporation, the city Housing Authority and the Department of Education, are covered by these state laws. But when city officials do play a role, they tend to be more aggressive than state officials in campaign finance reform. Pay to play has been no exception.

Last year, the city passed a series of laws that tighten restrictions on lobbyists. One of these laws changes the city's campaign finance system so that contributions from registered lobbyists can no longer be matched with public funds. In the past, such contributions were matched $4 to $1.

The city has not moved so quickly on restricting contributions from businesses seeking city contracts, however. In 1998, voters approved a charter amendment that called for the Campaign Finance Board to write stricter rules concerning such contributions. It still has not done so.

In 2004, the Bloomberg administration attempted to move on adhering to the charter provisions and introduced a bill that would have put a $250 limit on campaign contributions from people doing business with the city. Larger contributions would not be eligible for matching funds from the Campaign Finance Board.

That bill failed, with critics saying it went too far. For one thing, the language of the bill was so unclear that homeowners would have been considered to be "doing business" with the city if they applied for certain zoning variances.

Last year, the Campaign Finance Board came up with a series of proposal and asked the City Council to retrict pay to play. But nothing ever came of the plan.

The Bloomberg administration and the Campaign Finance Board disagree about whether the city has fulfilled its obligations under the 1998 charter amendment. The board says it has submitted rules for public comment and that, in any event, the city does not have the ability to enforce pay-to-play regulations.

But the administration disputes this. "The mayor has been clear that voter mandates should not be ignored for bureaucratic reasons or dismissed on technical grounds," said a spokesperson for Bloomberg.

CHANGING THE SYSTEM

Spitzer has said he would set limits on contributions on the state level but has not offered anything specific. So far he and Cuomo are not trying to directly restrict donations but would simply make the contributions more transparent. Cuomo's proposed "Project Sunshine" Internet database would track donors, lobbyists, special interests, state contracts and elected officials, and allow users to find the connections between them. Spitzer's executive budget contains money for the attorney general to pursue this project.

City officials have their own database of people who do business with the city called VENDEX. They hope to make it compatible with the city's campaign finance database, so that officials could monitor which contractors make campaign contributions. But VENDEX only includes current contractors, not those bidding on city contracts. In addition, the database does not include contractors involved in land use even though real estate is the city's biggest industry and developers are among the top donors to city campaigns.

One key dilemna in regulating pay to play is determing what, exactly, it means to "do business" with the city or state. This could be defined narrowly to mean someone with a city contract worth over a certain amount of money or it could be construed more broadly. "If you apply for a license for a sidewalk café, do you have to register? I don't think so," Gene Russianoff of the New York Public Interest Research Group has said. "You have to draw the line somewhere."

And there is the issue of what the city has the legal right to do. In many places, pay-to-play laws put the responsibility for compliance on the campaign contributor. If contractors make an illegal donation, their government contracts can be cancelled. But New York City does not have the legal authority to penalize contractors without the permission of the state.

Bloomberg's 2004 proposal avoided that problem by putting the responsibility on the candidates, punishing them if they accepted money from contractors illegally.

But good government groups see problems with this plan, too. Asking candidates, particularly for local offices such as City Council, to guarantee that none of their contributors hold contracts gives them "a great incentive to opt out of the public financing program," said Megan Quattlebaum of good government group Common Cause New York. "You essentially destroy this great program," she said.

Â

Tax-And-Spend No More

With his sixth preliminary budget, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has taken a big step toward a bold goal: to rid New York City of its reputation as a liberal, tax-and-spend city. How else to explain over a billion dollars of tax cuts, the squirreling away of billions in reserve funds, and a four-year plan that, with the exception of education, caps discretionary city spending? And the only roadblock to achieving the goal – the Democratic city council – thus far seems to buy into the plan.

The January 2007 budget plan carries a distinctly conservative stamp – but only to a point. The mayor, like former Mayor Rudy Giuliani before him, seems unwilling, even in the best of economic times, to take the ultimate conservative step: to offer a four-year structurally balanced budget. That’s something the conservative State Financial Control Board has been pleading for the past 15 years. And with budget surpluses of $3.5 billion two years ago, $3.8 billion last year (actually much more – see below), and nearly $4 billion in prospect this year, the times could hardly have been better to satisfy the plea.

Tax Cuts

The Bloomberg tax cut program – initially proposed for just one year – is scheduled for all four years of the plan. (Whenever City Hall proposes a budget for the next fiscal year, it also presents a more preliminary plan for the following three years as well.) The costs in lost city revenues from cuts in property, sales, and business taxes for fiscal years 2009 through 2011 make them a substantial cause of the big deficits in those years:

- In 2009, the lost revenue is projected at $1.4 billion, and the deficit at $2.6 billion.

- In 2010, the lost revenue is put at $1.5 billion, and the deficit at $3.7 billion.

- In 2011, the lost revenue is put at $1.6 billion, and the deficit at $3.6 billion.