The turmoil and uncertainty on Wall Street continues, punctuated by Merrill Lynch’s recognition last month that it had lost $8 billion in sub-prime backed mortgage securities. The profitability of many of New York’s financial giants has eroded and layoffs have multiplied, worrying city and state budget makers.

The latest losses, following three years of big gains, indicate the pitfalls of Wall Street’s all too frequent speculative binges. Wall Street’s tendency to create investment fads that enrich the few at the expense of the many, whether through dot.coms, Enrons, risky mortgages or whatever might come next, is not a smart way to run an economy. Beyond that, it all too often distracts attention from the financial realities facing people who live and work in the broader economy beyond Wall Street.

So, how are those people doing and how are they likely to fare if Wall Street’s woes continue?

Lately, wages and incomes have improved a little. Given that the economy has been in recovery since mid-2003 from 9/11 and the recession earlier in the decade, some gains should be expected. What’s surprising is that they took a while to materialize.

Against this backdrop, however, there are some troubling long-term trends in the New York economy. These trends have a lot to do with the economic well-being of average people and the neighborhood economy as opposed to the Wall Street economy that receives most of the media attention.

INCREASES IN INCOME

First, let’s take stock of the good economic news.

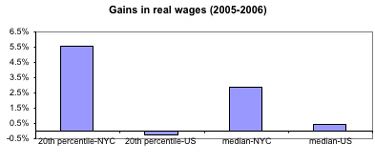

Hourly wages for most New York City workers, after adjusting for inflation, rose in 2006 and now are roughly back to 2002 levels. The New York worker in the exact middle of the pay scale made $15.38 an hour in 2006, 2.9 percent more than in 2005.The worker at the 20th percentile of the wage spectrum – a level representative of a low-wage worker – earned $9.27 an hour in 2006, 5.6 percent more than in 2005.

And as the graph below shows, wages for typical workers last year fared better in New York City than in the country in general.

NYC VS. U.S. 2005-2006, MEDIAN AND 20TH PERCENTILE HOURLY WAGE

Undoubtedly, earnings for low-wage workers received a boost from the increases in New York State’s minimum wage in 2005 and 2006 while the federal minimum wage of $5.15 remain unchanged until it was finally increased this July. New York’s minimum wage is now $7.15 an hour (a third and final increase took effect in January). The first of three annual 70-cent increases in the federal minimum wage lifted it to $5.85 in July.

Median family income has risen in New York City since 2003, climbing to $51,830 in 2006. Taking inflation into account, family incomes increased 3.9 percent between 2004 and 2006. This improvement resulted from increased wages and a slight increase in the number of people working. (It may also be that some of the apparent family income improvement results from a number of moderate income people –- those with incomes from $40,000 to $60,000 -- leaving the city, possibly due to rising housing costs and being replaced by more affluent household. See this report from the city comptroller’s office.)

Still, the city’s median family income is slightly more than 10 percent less than the U.S. median family income of $58,526.

SIGNS OF TROUBLE

The recent improvements in wages and family incomes are certainly welcome, but they could be short-lived given the turmoil on Wall Street and the likelihood that the national sub-prime lending crisis and housing market troubles will decisively slow overall economic growth. There is a growing realization that a good part of the national growth of recent years was fueled by the reckless expansion of sub-prime lending and other questionable Wall Street practices. Growth was fueled by excessive borrowing because there was not a broad-based growth in incomes.

There is more to the lopsided character of economic growth than irresponsible lending and the collapse of the housing bubble. The Fiscal Policy Institute’s recent The State of Working New York 2007 report highlighted other “troubling trends” that put recent economic news in perspective. These “troubling trends” characterize the state’s as well as New York City’s economy.

The “Productivity-Wage Gap”

Overall consumption spending has out-paced any growth in income and wages. Workers have not been sharing in the fruits of their labor. The “productivity” of New York workers – the value of what they produce -- has risen by over 11 percent since 2000 while inflation-adjusted average wages grew by only 1.1 percent. The emergence of this “wage-productivity gap” since 2000 is reflected in the fact that nationally, corporate profits have grown four times faster than total wages over the last six years.

Less Job Security, Fewer Benefits

An increasing number of businesses are hiring workers as “independent contractors” in place of employees. This results in a deterioration of working conditions and puts strains on social insurance systems. Employees get a range of benefits long taken for granted and essential to middle-class economic security: overtime pay, sick leave, co-payment of Social Security and coverage by workers compensation and unemployment insurance. As an “independent contractor,” a worker gets none of these. Nearly 10 percent of all private workers in New York are “misclassified” as independent contractors. The economic well-being of such workers undoubtedly falters compared to the status of a regular payroll employee.

This “misclassification” trend is part of the broader pattern of unregulated work and employer noncompliance with labor laws. Governor Eliot Spitzer recently issued an Executive Order, establishing an inter-agency task force to crack down on the illegal use of independent contractors.

Poverty-level Jobs

Despite recent wage and income gains, the number of working families who are poor or near poor is much higher now than it was in 1990. Today, poor people are more likely to have a job than was the case 15 years ago. Since so many jobs pay very low wages, having a job is no assurance of a decent standard of living. The number of people in working families in New York City who are poor, as defined by the federal poverty standard, has risen by two-thirds (222,000) from 1990 to 2005. Some 560,000 New Yorkers live in poor families, including over 250,000 children. Nearly half (47 percent) of children in working families in New York City live in families with incomes less than twice the poverty level. (The federal poverty level for a family of four is now about $20,000 a year).

A Widening Income Gap

Census data for 2006 confirm that New York State has the widest income gap between the rich and the poor (and the widest gap between the rich and the idle) of all 50 states. New York City’s income gap between the rich and the poor is considerably greater than for the state as a whole. In 2004, the richest 5 percent of people in the state accounted for 38 percent of all income while in the city, the top 5 percent garnered 47 of all income. Recent projections by the state Division of the Budget indicate the share of income flowing to the richest five percent jumped markedly between 2004 and 2007, a statewide trend that would also be evident in New York City.

All indications are that New York City’s economic recovery and expansion that began in mid-2003 is tapering off. The wage and income gains for most New Yorkers that finally materialized over the past year or two could be short-lived.

To confront this should involve more than crossing our fingers and waiting for the next Wall Street bubble to make things better. As with the increase in the minimum wage and the pending crackdown on the “misclassification” of workers, policy makers need to hone in on changes that will make a difference for average people striving to make ends meet in a city with a rising cost of living and in an economy that is all-too-prone to Wall Street-driven boom and bust. Otherwise, the “troubling” longer-term trends will completely swamp the short-lived gains that show up only at the top of the boom-bust cycle.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.Â