Stated Meeting: Tax Bills on the Floor

The City Council has its own solution to New York's fiscal crisis: Don't tax New Yorkers. Tax tourists.

At least that is what Councilmember Lewis Fidler said Tuesday when he introduced a bill to increase the city's hotel tax by less than 1 percent. The bill has the support of Council Speaker Christine Quinn.

A less acceptable proposal, according to some council members, also was put before the council. It seeks to increase the city's property tax rate by 7 percent. Mayor Michael Bloomberg introduced the property tax legislation and argues the city must raise taxes and cut spending to close a yawning budget hole in fiscal year 2010 and a smaller one in this year's budget.

The mayor has not taken a positionon the hotel bill, though he has opposed similar proposals in the past.

These bills are the first tangible signs of the fiscal crisis in the council chamber, and they follow an unusual bout of mid-year public hearings on agency spending cuts.

Taxing Hotels and Houses

Fidler's bill (Intro 879) would increase the city's hotel tax from 5 percent to 5.875 percent, adding another $2.62 on an average $300 a room rate. The increase could raise an estimated $80 million in new revenue, say city officials.

For the current budget year, which ends in July, the city is facing an approximately $300 million budget gap. That hole widens to about $4 billion for next year's budget if the city does not cut spending or raise taxes this year, according to the mayor's November budget proposal.

The hike in the hotel tax, say supporters, could help close that gap, without deterring tourists from visiting the Big Apple.

"If you were to spend a week in the city of New York and spend $2,100 on your hotel, are you really going to change those plans because someone just told you that it went to $2,120?" asked Fidler. "I don't think so. I don't think $20 is going to stop anyone from coming to the greatest city in the world."

Not everyone is so sure. The Hotel Association of New York City vigorously opposes the bill, arguing the increase would drive away business and result in a loss of $533 million in room costs and tourist spending.

"Any tax increase would be gravely detrimental to the city's economic health," said Joseph E. Spinnato, the president of the association, in a prepared statement. "This increase could bring us back to the dark days of the 1990s when convention planners -- outraged by the fact that city policymakers would take advantage of our visitors to fix a budget hole -- boycotted our area."

The association argues that the city's tax is already 14.54 percent, factoring in the $2 per night hotel occupancy tax and the $1.50 Javits Center surcharge.

Fidler says, however, the "insignificant" increase does not compare to the skyrocketing hotel taxes during the 1990s.

"In this difficult economic climate, the truth is, as unfortunate as it is, everyone is going to have to pitch in," said Quinn. "This includes the visitors to our city."

A City Council spokesperson said the city would not have to receive approval from Albany to raise the hotel tax. Nor would it have to seek Albany's approval if the council chose to pass the mayor's legislation (Intro 887) and increase property taxes. The current legislation does not specifically state a 7 percent increase, though that is what the mayor has proposed in his November budget proposal.

Quinn said she has not taken a position on the property tax bill yet. She added the council has the power to amend the property tax bill and so could revise the 7 percent figure.

If approved, a 7 percent increase would raise about $576 million in additional revenue.

Women and Minority Businesses Boosted

In addition to introducing the tax legislation, the council unanimously approved legislation (Intro 888) encouraging companies that receive industrial or commercial tax abatements to contract with businesses owned by minorities or women.

The bill requires a business that receives a tax break for a project worth more than $1.5 million to solicit bids from at least three women or minority owned businesses for each subcontracting opportunity. The businesses would also have to identify firms in the city's minority and women businesses directory who could do the work.

If a firm does not comply with the bill, it could lose its tax break.

Budget Battle: Round 1

Â

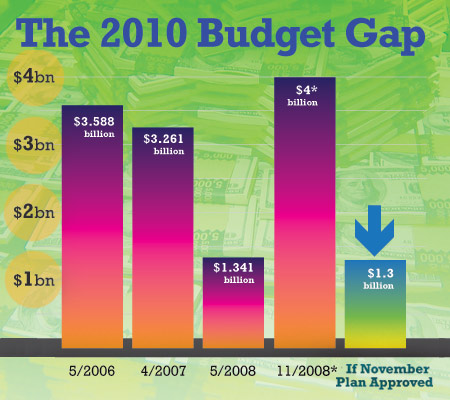

Image (c) Gotham Gazette

* This number is from the November financial plan, and includes the

fiscal year 2009 gap that has grown since the budget was passed in June.

See how the city has projected the budget deficit for FY 2010 over the years. Even in 2006, when the cityÂąs finances were in the black, the Bloomberg administration predicted a hole.

fiscal year 2009 gap that has grown since the budget was passed in June.

See how the city has projected the budget deficit for FY 2010 over the years. Even in 2006, when the cityÂąs finances were in the black, the Bloomberg administration predicted a hole.

Get rid of a property tax rebate or more than three police classes of 1,000 officers -- each will save about the same amount.

Increase property taxes by more than $200 for an average one- to three- family home or, maybe, slash supplies for public schools classrooms. Shut down the city's century-old dental program or add a five-cent tax on plastic bags.

Times are tough, say city officials, and we have to set some priorities.

This city budget season has started two months early, and the debate already involves lawsuits and squabbling. While it's not unprecedented, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's move to seriously revise city spending mid-way through the fiscal year gives some indication of how our economy has spoiled. Like it or not, some programs will have to be chopped.

Since the mayor announced his intention more than two weeks ago to cut city spending, rescind the $400 property tax rebate (a proposal whose fate remains uncertain) and increase property taxes by 7 percent come January, the City Council, uncharacteristically, has not waved any white flags. In some cases, they have called war.

Today is the last day of a weeks worth of hearings. Lines have been drawn and a victor is far from chosen. A vote is expected in early December.

Planning Early

In his typical fashion, Bloomberg's plan does not focus primarily on this year's gap, but the budget hole the city will face in 2010 and beyond.

He plans on cutting this year's budget -- through both raising taxes and reducing spending -- by $2.2 billion. (For more on the mayor's budget strategy, go here.)

That budget hole: $300 million.

Most of these cuts will go toward reducing the budget gap the city faces in fiscal year 2010. If the mayor's proposals win approval, they could reduce that deficit to an estimated $1.3 billion.

Why take these measures now?

"Everyone has to understand this is the only way we're going to get through this and have a future," Bloomberg said, sounding particularly doomsdayish, at a financial presentation earlier this month at City Hall.

The presentation, which normally takes place in January, sprang from the turmoil on Wall Street, which, Bloomberg argues, means the city needs to start cutting costs immediately -- seven months before the end of the fiscal year.

Most fiscal watchdogs say taking action early -- and addressing our fiscal problems before they turn too dire -- is characteristic of Bloomberg's approach to budget balancing.

"It's certainly consistent with the way he's operated since taking office," said Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office. "He doesn't just wait until you get there to start doing things."

Even so, there still may be some wiggle room now. For the City Council, that comes in a $400 property tax rebate.

Tax and Spend Policy

Rarely do the City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Mayor Bloomberg disagree publicly. Quinn has shepherded two controversial pieces of legislation -- both spearheaded by Bloomberg – through the council this year alone: term limits and congestion pricing.

But when it comes to delivering $400 checks to thousands of city homeowners, Quinn has staked out a position on one side, Bloomberg on the other.

Though the speaker declined to promise residents that they would get their rebate checks, which were supposed to be mailed in early October, Quinn said the council would do anything in its power to preserve the rebate.

"I can guarantee New Yorkers we are going to fight as hard as we can to get them those checks as quickly as possible," Quinn said at a press conference last week.

Part of that fight comes in the form of a lawsuit filed by council members Vincent Ignizio, James Oddo, Vincent Gentile, Lewis Fidler and Tony Avella. Assemblymember Louis Tobacco also signed onto the suit.

"This is just one of those out of touch with reality moments that you guys have over there from time to time," said Fidler addressing administration officials at a budget hearing on the rebate check. "I don't think you realize how much people who are living hand to mouth are expecting that check."

The council has argued the mayor cannot withhold the rebate checks without its approval -- which is a nonstarter. Bloomberg, who initially said he would not issue the check because the city had "no money," has started to back down. Last week, the mayor said he would work with the council to find "balance."

The rebate would cost the city $256 million. The tax hole for this year is $300 million. Do the math: The mayor's plan to increase taxes by 7 percent in January would bring $576 million -- more than enough to cover this year's gap. In fact, under his plan, the city would end the year with a surplus.

Again, it's about priorities.

Though the $400 rebate has become the council's cause of the moment, others say it's a regressive tax and the city should do away with it.

"They shouldn't have had the rebate in the first place," said Carol Kellerman, executive director of the Citizens Budget Commission. "This is not a need based amount. This is an amount if you are a single-family property owner. It doesn't matter if it's a townhouse on Fifth Avenue."

Who Wins and Who Loses

In addition to the tax increases, Bloomberg has proposed about $500 million in spending cuts in this fiscal year and more than $1 billion for next year's fiscal year. The agency cuts equal a reduction of 2.2 percent for fiscal year 2009 citywide.

Agencies have been ordered to cut their budgets by 2.5 percent for this year's budget and by 5 percent for fiscal year 2010. Some departments have received marginally more -- or less -- funding than others, but for the most part the cuts are across the board. (Check out a full funding breakdown here)

But for small agencies, a 2.5 percent cut can mean a lot. In addition, these cuts come on top of the spending reductions, which mostly hit social services agencies, that the council approved in June.

"They are looking to cut out anything that they are not required to provide," said Allison Sesso, deputy executive director of the Human Services Council. "This is just compounding cuts that were already taking place."

For example, the city plans to reduce the Department for the Aging's budget for "non-core social services," which has raised an alarm among some advocates. It also proposes to eliminate a $1.2 million program that provides adult day care to debilitated seniors and is doubling the co-payments parents pay to the Administration for Children's Services for day care programs from $1 to $2.

The mayor has also proposed eliminating 127 positions at the children's services agency, increasing caseloads for supervisors*. The city plans to close a job center and a clinic treating sexually transmitted diseases in Harlem and a homeless shelter at Bellevue Hospital Center.

At the Department of Homeless Services, the city will save $5 million in 2010 by providing incentives to city contractors for getting families out of emergency shelters and into public housing. Advocates say, however, the amount of available housing for these families remains stagnant.

The department also plans to require homeless working families to contribute to the cost of their shelter, which could bring in about $1.3 million next year.

For some advocates, that move touches a nerve.

"Many families actually save money while they're in a shelter," said Patrick Markee, a senior policy analyst at the Coalition for the Homeless. "It seems counterproductive and a little bit cold hearted."

Reductions in Blue

The Police Department plans to do its part to close the budget gap by putting fewer cops on the street. According to Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, the department will cut new hires by half, eliminating one of the two yearly officer-training classes. Normally, police academy classes begin in January and July, and slightly more than a thousand officers graduate from each class. The elimination of the January class will save $36 million next year, but it will bring the department’s force to its lowest level in years. Along with reducing the number of new recruits, Kelly said, further reductions will come through attrition and a cut in civilian staffing, generally in clerical, administrative and custodial positions.

Before Bloomberg mandated the budget cuts, the department had planned on a peak headcount next year of almost 37,000 uniformed officers. At a joint hearing of the City Council’s public safety and finance committees on Nov. 24, council members expressed concern that crime would rise with fewer officers on the street. Kelly countered that the overall crime rate has decreased by 28 percent since 2001, when there were about 40,000 officers on the force—the department’s all-time peak.

"We’re going to do everything we possibly can to continue to reduce crime in this city," Kelly told committee members. "We’ve done it effectively at a time when we lost some 5,000 officers. Crime has still come down and it's safer than its ever been."

Public safety committee chair Peter Vallone Jr. was not convinced. While overall crime has fallen, Vallone said, certain violent crimes have increased: Murder is up 6 percent, and rape and burglary are each up 2 percent so far this year. And, he said, the decline this year in overall crime is the smallest so far since 2001.

"The NYPD always says it can do more with less, but at this point, Batman would have trouble doing more with the amount of resources we have allotted," Vallone said in a statement issued after the hearing. "If public safety suffers, everything suffers."

Vallone is particularly worried that any rise in crime could exacerbate New York’s economic crisis, affecting tourism, retail and real estate.

The department plans additional savings by shifting additional law enforcement duties to traffic enforcement agents. For example, until now, only uniformed police officers could ticket vehicles for obstructing traffic at intersections. Gov. David Paterson recently signed a bill requested by Mayor Michael Bloomberg that allows the city’s traffic enforcement agents to issue these tickets.

Classroom Cuts

Even city's public school have not escaped the current round of budget cuts. The administration has proposed $180 million in cuts to the Department of Education's $21 billion budget this year and $385 million next year. In June, the department took a $200 million reduction but, partly through the efforts of the council, school classrooms were spared.

This time around though, classrooms would see a $103 million reduction. Where exactly that would fall will remain largely up to individual principals, although no teachers will lose their jobs. "The principals have made it clear that none of these cuts are easy or without pain, but they expected these cuts," Deputy Chancellor Kathleen Grimm told City Council.

For the first time, the administration proposes to reduce spending at the District 75 schools serving handicapped students – although by a relatively modest one half of one percent.

Other cuts will come in administration where the department proposes to eliminate 338 positions, cut back on the Teaching Fellows program, trim expenses on meetings and eliminate science assessment. Some maintenance positions serving schools will also be lost.

Given how volatile school spending cuts tend to be, Friday's hearing on the reductions was relatively low key. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum reiterated her concerns about the department's spending on its so-called accountability initiative, Fidler suggested the school use energy efficient light bulbs, and John Liu wondered how much the department had spent on an ill-fated plan to centralize kindergarten admission.

There were, though, apparently no real fireworks. Those could come at public hearings today. On the other hand, almost everyone at the hearing realized this round of cuts could be the relative calm before the storm. The state has not enacted any cuts for now, but everyone anticipates that will change. With the state providing 41 percent of the Department of Education's funds, how much of the cuts could fall on city schools remains anyone's guess.

"I make it a policy not to predict what Albany will do," Grimm said.

Other Battlegrounds

At another of many budget hearings last week, Councilmember Gale Brewer questioned the administration on how it collects taxes from vacant buildings.

Sitting at the very top of the dais, Brewer couldn't help but add a closing remark.

"Don't cut the libraries," she jabbed.

A typical council-mayoral battleground, libraries under the budget plan would cut back hours to an average of five and a half days from the current six. Some branches, said an aide to the council's libraries subcommittee chair, Gentile, would only be open for five days, while others will be budgeted for the extra half day. The library cut would save $8 million in this fiscal year.

The council will also almost certainly object to cuts at the police department and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The administration has proposed delaying a police class of 1,000 officers, reducing the overall headcount at the department. The training program at the fire department's academy will be cut from 23 weeks to 18 and several engine companies will lose their night hours, for a combined savings of $7.5 million.

Councilmember Peter Vallone, head of the council's public safety committee, has made this police headcount reduction part of his checklist for elimination.

The mayor's proposal to eliminate the city's dental program for children, which began in 1903, is also drilling up some ire. The program serves 1 percent of the city's kids and costs $2.5 million.

Looking Forward

Most agree the worst is to come.

All of these cuts do not factor in an estimated $12.5 billion deficit in Albany, which is sure to translate into deeper slices in school aid statewide. This year, the city received $11.7 billion from the state -- about 20 percent of the entire budget.

The State Senate is set to hold a special session next month to consider cuts by Gov. David Paterson. The governor is also scheduled to release an updated fiscal response to the crisis in December.

These budget revisions also do not take into account debilitating deficits at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the New York City Housing Authority. The city's public hospitals network, the Health and Hospitals Corp., is also struggling, say officials.

Our fiscal troubles are far from over.

"I think this is a very difficult budget year, but you typically don't see these budget modifications change very much," said Markee. "We're a lot more worried about what's going to happen in next year's budget."

*When this story originally appeared, it gave the impression that all caseloads at the Administration for Children's Services were increasing. In fact, regular caseworkers will not be affected by the budget cuts. Some supervisors, who had taken on only a few cases in the past, will now have a full caseload.

Dara L. Miles contributed reporting to this story.

The Mayor's Budget-Cutting Strategy

Photo (cc) Pixotropic

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's November budget modification is interesting for two reasons. First of all, it underscores the city's short-term budget health. Modifying this year's budget to keep it balanced remains a relatively easy task. Quite unlike the alarms spilling out of Gov. David Paterson's office, the modification for the city has no sense of immediate urgency.

(For more on the cuts and the City Council's reaction to them, see related story.)

Secondly, despite that, it is indeed full of warnings about the city's mid and long-term fiscal prospects. Further, it includes several hints of how the mayor will address big deficits in 2011 and 2012, including drawdowns from the Retirees Health Benefits Trust Fund and some less-than-progressive tax increases.

Short-term Budget Health

The city's conservative revenue estimates and the mayor's habit of building budget surpluses, then rolling them over into future years -- $6.5 billion last year alone - thus far have cushioned the economic decline's impact on city services. In fact, the November modification accomplishes its first priority -- re-balancing this year's budget -- quite easily. The budget shortfall at the moment (mostly from a drop in business income taxes) is only $300 million, a tiny fraction of a $60 billion budget, and the mayor's already implemented cutbacks this year - about 2.2 percent of agency spending - more than cover it.

The controversy has arisen from the mayor's two revenue recommendations -- rescinding the 7 percent property tax rate cut in January, worth $576 million in new revenues, and trying to cancel this year's $400 rebate for homeowners, worth $256 million. These revenues and the agency cutbacks together actually would increase the city's budget surplus for this year by nearly $1 billion. Assuming all this happens, these moves, along with other anticipated surplus and reserve funds, would put the city on the road to a 2009 surplus of over $2 billion.

The City Council usually just rubberstamps modifications. This time, though, the property-tax changes became the focus of council ire.

At the first of the hearings, on Nov. 17, council members grilled Bloomberg budget director Mark Page. During the questioning, Finance Committee chairman David Weprin produced a document -- from the mayor's office -- saying the rebate could not be canceled without council approval. Since the council has indicated it would not agree to this part of the mayor's plans, it seemed the checks would soon be in the mail.

On Wednesday, though, Bloomberg indicated he would continue to block the rebate, setting up a showdown between him and the council. By the end of the week, the mayor was striking a somewhat more conciliatory tone, opening the way to possible negotiations.

Whatever the result of this dispute, the mayor's proposed cutbacks continue his style of budget balancing thought across-the-board agency cuts. No priorities here: Not only does education share in the cutbacks - over 2 percent or $181 million this year and 5 percent or $385 million next year - but such popular agencies as the police department ($45 million this year, $167 million next), libraries (which on average will be open half a day less than they are now) and cultural organizations ($3.8 million this year, $7.2 million the next) all take hits.

The Education Cuts

One of the significant debates in current and future council hearings likely will focus on the actual impact of big cuts in education. The mayor argues that the cuts will be in administration and other non-classroom areas. The council will respond with its own list of administration cuts, saving $150 million, Council Speaker Chris Quinn said in an October speech to the business-sponsored Citizens Budget Commission

As the council and the Department of Education joust about "administration" cuts, they might look at the Independent Budget Office's new fiscal brief "The School Accountability Initiative: Totaling the Cost." The study - hampered, as the IBO puts it politely, by "the limited information available to outside agencies through the city's financial data systems" (See Gotham Gazette's "High Stakes Test" for more) - shows how slippery the definition of administration can be.

The IBO estimates that administering the schools' new accountability initiative, which prepares the school progress reports or report cards and launched in April 2006) cost $130 million last year, and will cost $105 million this year. Alternatively that $130 million could buy 13 million paperbacks at $10 each, or about 13 books for every student in city schools, pre-K to 12.

According to the education department, however, using a more narrow definition of accountability, the initiative cost only $37 million last year and $48.5 million this year.

Future Problems

The mayor's November modification takes care of the small 2009 budget deficit, and, if the council buys into the January 2009 property tax increases, also reduces the projected 2010 deficit from $2.3 billion to $1.3 billion. That too would be manageable.

Then the real trouble begins. For instance, the first major sign of fiscal stress stemming from Wall Street problems is the modifications projection that the city in 2011 and 2012 will have to make up for approximately $1.1 billion in city pension funds lost recently in the stock market.

The mayor proposes to solve the pension fund problem by taking a total of $1.1 billion from the Retiree Health Benefits Trust Fund in 2011 and 2012, a mayoral discretionary (or "rainy day") fund originally designed, as its name suggests, to meet city liabilities for future health expenses of city retirees. The fund received a total of $2.5 billion from budget surpluses in 2006 and 2007.

Both Quinn and City Comptroller Bill Thompson have in recent years proposed a legislated rainy day fund that would set the terms for a fund draw-down in a fiscal crisis, and it will be interesting to see how they respond to the mayor's sudden change in the use of that fund.

Even with drawdowns from the retirees fund, deficits for 2011 and 2012 will average $5 billion. The current modification looks ahead, and its revenue options in the modification for 2010 provide at least a hint of where Bloomberg might go with tax policy. However, his short laundry list of tax increase options reads more as a partial primer than as a comprehensive revenue plan, interesting as much for what it leaves out as what it includes.

Tax Options

The city's current four-year fiscal plan already assumes that, in July 2009, the average property tax rate will revert to its 2002 to 2006 rate and stay there. The proposed November modification, as noted earlier, would simply make the rescission effective in January 2009 rather than July.

This means other revenues will be necessary. The modification offers several possibilities to meet the 2010 deficit: three options for increases in the sales tax - the most regressive of all taxes -- and two options for across-the-board rate increases to the personal income tax.

Notable for their absence are any options to increase business taxes or to restore a more progressive personal income-tax rate structure. In a city that overwhelmingly voted for Barack Obama and, presumably, for his progressive tax agenda, including tax cuts for working and middle class families (see "Candidate Talk Taxes"), the mayor's options of 7.5 percent and 15 percent across-the-board increases in the personal income tax rate hit these same, most vulnerable of taxpayers.

Six years ago, as part of the huge November 2002 modification, the same mayor increased income tax revenues in a progressive way, by creating two temporary, three-year top rates for higher-income taxpayers. Other taxpayers' rates remained unchanged.

An across-the-board 7.5 percent increase would raise $585 million in 2010; a 15 percent increase would raise $1.2 billion. The 7.5 percent increase would cost a taxpayer with taxable income between $50,000 and $75,000 an additional $116. A 15 percent increase would cost her $233.

A taxpayer with taxable income between $75,000 and $90,000 would pay, with a 7.5 percent increase, an additional $178, and with a 15 percent increase, $356 annually.

The regressive sales tax options include increasing the city sales tax from 4 percent to 4.25 percent, raising $292 million in 2010, or to 4.125 percent, which would raise $146 million. Reinstituting a sales tax on clothing (the current exemption reduces the sales tax's regressivity) would raise $436 million.

Taking two of these options -- raising the sales tax rate to 4.25 percent and increasing the personal income tax across-the-board by 15percent -- would raise $1.5 billion in 2011, only 30.5 percent of that year's projected $5 billion deficit.

What then? The mayor in a brief statement in the modification said, "We have tried to strike a balance between increases in revenue and decreases in planned spending," so the balance in 2011 would presumably come from further unspecified (across-the-board?) agency cuts.

The mayor should be commended for providing extensive information in the November modification. The summary document alone runs 55 pages. But there is minimal explanation of the data in the summary and, more importantly, too few options and too little big thinking. In its February 2008 Budget Options for NYC, for instance, the IBO listed 29 revenue options.

The IBO lists five scenarios for the personal income tax alone. All would make the tax more progressive. The most familiar, a version of the 2002 increase, would add two top rates. A 3.9 percent rate would go into effect for joint filers with incomes of $225,000 and above and a 4.2 percent rate would kick in for joint filers with income of at least $450,000. This would raise over $600 million in 2010 and would leave the rates for working and middle-class New Yorkers unchanged, a big plus in a slumping economy.

One other big revenue producer is worth noting again, but it would require changing the conversation between mayor and council. Instead of debating how to cut $200 million or $400 million from the education budget, why not look seriously at tolling the East and Harlem River bridges? Kids vs. cars? The IBO estimates the city could raise over $800 million with a toll plan.

The pain ahead for New Yorkers is not likely to be "across-the-board," and at some point the budget decision-makers will need to set some priorities. Across-the-board tax increases and across-the-board service cuts don't meet that challenge.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

The Public Speaks on Budget Cuts

For David De Porte, the Department for the Aging's intergenerational program doesn't just provide him with companionship. It gives him a set of eyes.

De Porte, a blind lifelong resident of the West Village, meets with teenage volunteers who help him shop for groceries, fill out paperwork and check prescriptions at the drug store.

"Guide dogs are great, but they can't read labels, and people in stores are not always willing to help," De Porte, a freelance writer, said. Xia, his German Shepherd guide dog, lay quietly by his side during his two minute testimony in front of the City Council yesterday.

The intergenerational program costs more than $1 million. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's budget proposal, released earlier this month, would eliminate that funding.

De Porte was one of many members of the public who got their first opportunity to opine on the mayor's budget proposal Monday. The proposal cuts -- by both increasing taxes and slashing spending -- $2.2 billion from this year's budget. The funding decreases would shrink next year's anticipated deficit to $1.3 billion.

For more on this year's budget cuts, check out "Budget Cuts: Round 1" and our breakdown of each department's cuts.

Cuts to Culture

Among City Council members, the elimination of a $400 property tax rebate has caused the most alarm, but the scores of residents who came to City Hall were far more concerned over the cuts to cultural, health and aging programs.

From doing away with the city's century-old dental program to cutting day care programs for debilitated seniors, the city, residents said, is eliminating the programs that are needed most when times get tough.

As she wound up small chattering teeth toys, Judy Wessler, the director of the Commission on the Public's Health System, asked: "We're talking about children losing their teeth right?" -- referring to the axing of the city's dental program. She let the teeth loose, and they danced off the testimony table.

The heads of the city's most prominent cultural institutions, like the American Museum of Natural History, urged the City Council to revise the mayor's budget proposal to soften the cut's impact. While all of the city's agencies saw an approximately 2.5 percent cut in this year's budget, cultural institutions argue their funding has been cut far more drastically.

According to figures provided by the Cultural Institutions Group, groups have seen cuts as high as 42 percent in city subsidies. The American Museum of Natural History's city funding has been cut by 22 percent -- a total reduction of $2.8 million -- in this fiscal year, while Lincoln Center's has been slashed by 42 percent. The entire cultural consortium has seen a total loss of 18 percent, according to figures provided by the group.

A reduction in programs for the city's most vulnerable, including residents of public housing and senior citizens, drew extensive criticism. The mayor slashes funding for local nonprofit groups that, critics say, will drastically reduce the local services they can provide. Many wondered what would happen to the care programs for seniors with Alzheimer's or the arts and education classes at their local community center.

"Is the city of New York so impoverished that it must rob these seniors of a last modicum of dignity?" asked Patricia Dolan, executive vice president of the Queens Civic Congress.

The mayor's plan will reallocate community services at the New York City Housing Authority saving the city $18.6 million. The cuts, though, will result in the closing of 18 community centers, one in Karen Anglero's Flushing project.

"New York City Housing Authority residents are the city within the city, and we vote, and we'll remember in November 2009," said Anglero.

Where the Cuts Come From

Â

The "old" budget figures were in the city's 2009 fiscal budget, approved by the City Council in June. The "new" figures are from the budget modification the mayor proposed in November, which is still awaiting City Council approval. For more on the specific items being cut and the debate over taxes and spending see Bugdet Battle: Round 1.

> >

|

Budget figures do not include debt service, pension costs, and long term employee health care costs.

*Library figures are skewed because the administration pre-paid costs in the previous budget year. Therefore, budget cuts for major library branches are 2.5 percent for this budget year and 5 percent for fiscal year 2010. Some budget increases, including the police department, are attributed to increases in labor union contracts.

Stimulus Money: The Downturn's Silver Lining?

The doom and gloom minor-key melody that has been the city, state and federal government's economic song for the past few months has a contrapuntal drum beat beneath it: the steady call for infrastructure spending as an economic spur.

Since the financial crisis began, transportation advocates and trade groups representing the construction industry have called, frequently and loudly, for increased spending on transportation infrastructure. Nobel Prize laureate Paul Krugman joined fellow New York Times columnist David Brooks to suggest that investment in transportation infrastructure is both necessary and sensible given the state of the country's roads, bridges, transit systems and railways, as well as the dire need for jobs and domestic spending.

The economic turmoil has also created a huge financial shortfall for New York City's mass transit system, which relies heavily on dedicated tax revenues to fund its day-to-day operations. While a stimulus package could provide capital money for the city's subways and trains to expand and improve, current proposals would do little to remedy the billion dollar operational deficit facing the system.

On Sept. 26, the House of Representatives passed the Job Creation and Unemployment Relief Act of 2008, a $61 billion economic stimulus package with $30 billion set aside for transportation and infrastructure programs, including $12.8 billion for highways and bridges, $4.6 billion for transit and $500 million for Amtrak. The Senate has not yet taken action on the bill, but Rep. Jerrold Nadler of New York, who sits on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, said that he expects to see a $60 billion to $100 billion stimulus program, with large infrastructure allocations, signed into law during the lame-duck session this fall.

The New York Times reported that President-elect Barack Obama is already working with congressional democrats on a larger stimulus package to be passed in January, including "more jobless benefits, food stamps, aid to financially strapped states and cities, and spending for infrastructure projects that keep people at work." "Most economists I've talked to are saying between $300 and $400 billion for the larger stimulus bill" to be passed after Obama and the new Congress takes office, Nadler said.

If and when either of these bills becomes law, how much money will eventually find its way to infrastructure improvements in New York State and New York City?

Ready-To-Go Projects

This, in large part, depends on the list of "ready-to-go" projects prepared by the state and city transportation departments and regional authorities like the MTA.

For transportation infrastructure spending to work as an economic stimulus, the federal government's money needs to be put to use as quickly as possible, according to Nadler. "The point of a stimulus package is to get money spent and have it circulate, so part of an intelligent package is picking projects that can get done now: Environmental review is done. Plans are done. Shovels can go in the ground. Bricks can be laid. Workers can get paid," he said.

Projects that meet these requirements are termed "ready-to-go" and are given preference in the stimulus bill that the House passed in late September. It reads: "Priority in the use of funds shall be given to projects that can award contracts based on bids within 120 days of enactment." Similar language will almost certainly appear in any final stimulus legislation with large allocations for infrastructure spending.

According to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the economic impact of capital spending can be roughly estimated by assuming every $1 billion equates to 8,700 jobs, $54 million in wages, and $1.5 million in related economic activity. The House Transportation Committee staff estimates that the $30 billion set aside would create or sustain 834,000 jobs nationally.

Furthermore, because of Buy America laws, which require that steel, iron and manufactured goods used in federally funded projects be made in the United States, the benefits from these dollars will extend beyond construction companies. Parts producers, manufacturers, assembly-line laborers and every related industry, from food service to work-clothing companies, will see some of the benefit too.

Ready-to-Go in NYC

Because this money may soon be available, states, cities and regional transportation authorities across the country are scrambling to put together lists of ready-to-go projects. Last January both the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials and the American Public Transportation Association surveyed member groups about what projects they had in the pipeline that would be eligible for this kind of federal funding.

New York City Transit listed five projects in need of a total of $742 million, including $550 million for the rehabilitation of two dozen subway stations; $30 million for replacing obsolete rails and plates; $100 million for passenger-communications infrastructure at 87 stations; and $62 million for the construction of additional pedestrian overpasses and viaduct spans. The MTA's commuter rail lines responded by listing roughly $35 million in ready-to-go projects, including $23 million for maintenance facility repairs.

In response to the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials survey, the New York State Transportation Department listed 40 highway and bridge projects adding up to $200 million, although as of publication, specifics were not listed on the association's website. However, in a telephone interview, Felice Farber, director of external affairs at the General Contractors Association's New York chapter pointed to a Manhattan Bridge rehabilitation project as one that could be eligible for federal stimulus funds.

Of course, both here and around the country, there will almost certainly be more projects seeking funds than money available. The lame-duck session stimulus bill that the House has passed makes clear that fund distribution will be based on existing statutory formulas with preference given to ready-to-go projects. There is no indication of how funds will be distributed in the second stimulus bill, but some area advocates hope that, because of New York State's strong presence on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, as well as Obama's pro-urban inclinations, big cities might do relatively well.

Building on a Bad Foundations

Although transportation and construction advocates long involved in the fight for maintaining the country's transportation system are pleased that the federal government might soon step up and contribute large amounts of money to help the nation's ailing infrastructure, some worry about spending on capital construction at a time when agencies like the MTA are struggling to meet their day-to-day operating expenses.

On Nov. 10, the MTA held an emergency meeting of its finance committee and projected an operating budget gap of $1.2 billion for 2009, growing to upward of $2 billion by 2012. The federal legislation being considered right now would not help the MTA close these gaps but would instead focus on capital construction projects. To runs its subways, trains and buses, the MTA will have to fight for increasingly limited city and state funds, enact internal cost-cutting measures and raise fares and cut service.

"We've raised the alarm on MTA finances plenty of times before, but this is the worst the books have looked in a generation," said Wiley Norvell, communications director at Transportation Alternatives. "We're staring down the twin barrels of big fare hikes paired with big service cuts, and it isn't pretty."

The choices here are complicated.

"It creates a real question to where the money should be going," said Neysa Pranger, communications director at the Regional Plan Association. "It's vital to expand for many reasons, but what happens if fares skyrocket and tracks crumble while that's happening? I don't see that resonating well with the public."

Richard T. Anderson of the New York Building Congress disagrees. "They should cut operational spending before they cut capital," he said. "Cutting capital would be disastrous. If we cut operations it means that each office needs to economize, but if you slash the capital you're hurting the economic growth of the city when you need it most."

Judging by the legislation as it's written now, it seems likely that Anderson and other construction industry advocates will have their way, but there is a lot left to unfold. Congress must first pass a stimulus plan, the president must sign it into law, and New York City and state must be ready to go. All the while new interest groups and new constituencies will be looking for their piece of the pie. One thing is for sure, in an economy like this, it will be a scramble from start to finish.

Â

It's the Economy

Not to long ago it seemed immigration would play a key role in this year's presidential campaign. But the hot-button issue has faded into the background since the economy emerged to trump everything else.

The economy also dominates news in much of the immigrant press as it does in mainstream media. Immigrants will feel the pain spreading throughout society, Larry Tung reports, but the suffering will fall particularly hard on some people who are not citizens or who work in construction or have low-levels jobs in service industries.

This month's Citizen looks at the recession's effects on various immigrant communities and workers. We also present some last-minute stories on the presidential campaign, as well as articles on a court ruling on restaurant delivery workers, Hindu-Muslim marriages, the fate of an East Harlem market and more from the Spanish, Chinese, Russian and Polish language press, via our partner Voices that Must Be Heard.

Polish Workers Fear Job Losses Super Express

The troubled economy has taken a heavy toll on construction jobs, creating less work for many Polish New Yorkers. There are fewer jobs in the building trades, and those that remain offer fewer hours or lower pay.

Food Crisis Affects New York's Children El Diario/La Prensa

A new study documents one effect of the economic turmoil is having on low-income people in New York, particularly children.

Despite Flagging Economy, New York's Haitians Seek to Help Hurricane Victims Haitian Times

Campaign Offers Little Discussion of Immigration Caribbean Life

Because the third presidential debate focused on domestic issues and took place on Long Island, where immigration has been a controversial topic, many observers thought the candidates would finally talk about immigration. They did not. Advocates discuss why.

Churches Walk a Fine Line on the Election Carib News

Many ministers with West Indian congregations support Barack Obama for president -- but they can't come out and say so.

Court Decision on Pay Alarms Restaurant Owners World Journal

Chinese restaurant owners reacted with shock and dismay to a court's decision that Manhattan's Saigon Grill restaurant chain must pay 36 Chinese deliverymen a total of $4.6 million in back wages and damages.

What Union Membership Means to New York Latinos El Diario/La Prensa

Some 300,000 Latinos in New York belong to labor unions. A study investigates what unions mean for these workers.

Upstate Towns Seek Immigrant Doctors Novoye Russkoye Slovo

At a recent job fair, upstate communities served refreshments, touted their recreational opportunities and offered pictures of scenic landscapes -- all in an effort to convince immigrant doctors to leave the city and practice in New York's rural areas.

Some in Greenpoint Oppose Bike Lane Nowy Dziennik/Polish Daily News

Thousands of cyclists in Brooklyn are cheering the prospect of a 1.5 mile greenway that would go from Greenpoint to Sunset Park, but some community residents say the area already has enough bike lanes.

Fallout from Tainted Milk Scandal Reaches Chinatown World Journal

Since melamine was found in Chinese milk products and animal feed, New York's health inspectors have stepped up their scrutiny of Chinese products.

Plans for East Harlem Market Fade Latin Week NY

For years, residents, merchants and city officials have talked of revitalizing the La Marqueta marketplace, but now all efforts seem stalled.

Bangladeshi Community Sees Rise in Hindu-Muslim Marriages Weekly Thikana

Interfaith marriages were once a rarity in the Bangladeshi community, but in this country, where sexes and religions mix freely, they have become increasingly common.

Â

Amid Economic Turmoil, the Candidates Talk Taxes

In the short run, local politics in the next few weeks may well have more effect on individual New Yorkers and the city's budget than November's presidential and congressional elections. Because the city must keep its budget balanced, it will have to deal almost immediately with the current financial and economic turmoil. For now, though, the mayor's push to extend term limits has obscured a full discussion of the city's tax and spending options.

Nevertheless, proposals in the U.S. Senate and House of Representative, as well as those from the McCain and Obama campaigns, make it clear that there may well be significant changes in federal tax and spending priorities that will affect New York. The most immediate revolve around short-term Democratic economic stimulus programs that could be implemented soon after the elections.

In the longer term, the McCain and Obama campaigns have spelled out, particularly on the tax side, unusually detailed descriptions of what their administrations would pursue in 2009 and beyond. They provide a rare look at - and debate about -- basic conservative and progressive policies in the 21st century. Those campaign proposals that have been analyzed recently -- and new ones come out almost daily - provide an interesting context for New York City's own fiscal choices.

STIMULATING THE ECONOMY

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities recently analyzed the state-by-state impact of three provisions in House and Senate economic-stimulus proposals introduced in late September: extended unemployment benefits, increased food stamp benefits and new resources for states in need of fiscal relief. These, according to the center, are "among the most highly 'stimulative' policies available to Congress, primarily because they concentrate relief on those most likely to spend the money quickly, pumping dollars into an economy that needs more demand."

Because of legislation enacted earlier this year, unemployment benefits have been extended by 13 weeks. The new proposals would extend benefits another seven weeks in all states, and in the case of states with unemployment over 6 percent, another 13 weeks, for a total of 20 additional weeks of benefits in those high-need states. The center estimates that 1.4 million unemployed Americans will lose their benefits through December 2008, including 70,426 in New York State -- unless the Congress agrees to the extensions.

A temporary increase in food stamp benefits - a program fully funded by the federal government - would help offset recent sharp increases in basic food prices for 28.6 million eligible Americans. The Senate proposal would raise benefits by 10 percent, or $5.2 billion. The House proposal would increase benefits by $2.6 billion.

The report notes that food stamp benefits, because they are spent immediately, generate economic activity, so that one additional dollar of food stamps turns into $1.73 in total economic stimulus. Thus the total economic impact would be about $10 billion for the Senate plan and $5 billion for the House proposal.

Over 2 million people in New York State would benefit from the Senate and House food stamp proposals. Food stamp funding in the state would increase by $346 million in the Senate plan and $175 million in the House plan. The estimated total economic stimulus effect of the two plans in New York would be $640 and $320 million, respectively.

A third provision of the congressional plans would temporarily increase the federal share of state Medicaid spending, thus helping states avert budget cuts or tax increases. The Senate would increase federal funding for the healthcare program for low-income people by $19.6 billion over the next 14 months, the House by $14.4 billion over the next 13 months.

New York State would be the biggest beneficiary of this idea, receiving $2.65 billion under the Senate proposal, $2.44 billion from the House version. Because the city pays a substantial share of the state's Medicaid spending, this new benefit would presumably help ease New York City's budget problems. (New York City's share of Medicaid spending is projected to exceed $5.6 billion this fiscal year.)

THE CANDIDATES' TAX CHANGES

It will take longer for New Yorkers to feel the effects of any new federal tax policy arising out of the November elections. Whoever is elected, though, some state residents will benefit and others will lose from changes in personal income, estate, capital gains, dividends and payroll taxes.

The 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts, which McCain would continue, are currently scheduled to expire at the end of 2010. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities issued a report in March that calculated the cuts will total $3.8 trillion if they are extended through 2018.

The $3.8 trillion in income and estate tax benefits go overwhelmingly to wealthy taxpayers. Seventy-four percent of the gains -- $2.8 trillion -- go to the top 20 percent of taxpayers. Thirty-one percent of the benefits -- $1.2 trillion - go to the top 1 percent of taxpayers (those with annual incomes above $450,000 in 2008). In 2012 alone, with the extended tax cuts in full effect, the top 1 percent would get cuts totaling $109 billion, almost one third of total cuts that year, or $67,000, on average, for each household.

Any such extension would of course have similar consequences in New York State. An October 2006 study by Citizens for Tax Justice estimated that in the 2001 to 2010 period the wealthiest 1 percent of New Yorkers (with an average annual income nearly $2 million) will receive 48.3 percent of the tax cuts, an average of nearly $80,000 a year. The poorest 60 percent will get only 13.7 percent of the tax cuts over 10 years, averaging only $379 a year. Income Taxes

An Oct. 16 Citizens for Tax Justice report analyzes the most recent Obama and McCain campaign tax plans. Both campaigns have proposed large cuts in the personal income tax. McCain's plan would cost $489 billion in 2012, Obama's, $348 billion.

The candidates' personal income tax plans have quite different beneficiaries. "Obama's plan would give taxpayers in the bottom 60 percent of the income distribution a larger tax cut, on average, than McCain's plan ($1,044 vs. $823 in 2012)," according to the report, while "The average benefits for the richest 1 percent of taxpayers under McCain's plan would be 43 times as large as the average benefits for this group under Obama's plan."

This arises largely from the candidates' approaches to extending the existing Bush income tax cuts, plus their different additional tax-cut packages. For example, McCain would extend the Bush cuts for 100 percent of taxpayers, and Obama would extend them for over 97 percent of taxpayers.

In the Obama plan, those 2.6 percent of taxpayers who have taxable income of more than $200,000 (singles) or $250,000 (married couples) would lose their Bush tax cut. The top income tax rate would revert from the current 35 percent rate to 39.6, the rate during the Clinton administration. Thus the Obama plan on the tax cut extensions would cost less -- $146 billion - than McCain's plan, $216 billion in 2012.

But both candidates have proposed big additional income tax cuts. McCain's largest one is a so-called "alternative simplified" tax, which Citizens for Tax Justice says will cost $98 billion in 2012, with 58 percent of the benefit going to the richest 5 percent of taxpayers.

For his part, Obama proposes what he calls the Making Work Pay Credit. This is a $500 refund of Social Security taxes for each working person ($1,000 for a working couple). This would cost $65 billion in 2012, with over half of the benefit going to the poorest 60 percent of taxpayers. Obama would also exempt seniors with taxable income below $50,000 from income taxes.

Both candidates offer proposals on cutting the estate tax that Citizens for Tax Justice describes as "costly and regressive," only benefiting "people who inherit huge amounts of money." Both candidates would raise the amount of an estate that would be exempt from taxes -- Obama to $7.5 million for a couple, McCain to $10 million. McCain's plan, which would drop the estate tax rate from 45 percent to 15 percent, is much more expensive ($60 billion in 2012) than Obama's ($29 billion in 2012), which would establish a 45 percent rate.

Taxing Business

Both candidates plan cuts in the corporate tax. McCain would lower the current corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent. Obama would keep the 35 percent rate, but would introduce several new business tax cuts.

CTJ notes that its study of corporate tax liability from 2001 to 2003 found that, after factoring in loopholes, the average effective tax rate for 275 of the largest corporations was less than half the statutory rate of 35 percent. Nearly a third of those corporations paid no tax at all in at least one of those three years.

The report notes finally, "The best that can be said for either of these tax plans is that they might not be fully implemented." Given the economic turmoil, it says, "the next president -- whoever he is - could decide to significantly cut back on the portions of his proposals that are more targeted to the wealthy."

THE LOCAL PICTURE

New York City, with its own budget so dependent on tax revenues generated by Wall Street, faces a more immediate fiscal problem than the federal government does. Worrying about budget deficits doesn't seem to be a priority in Washington. In fact, any federal economic stimulus package will be funded by deficit spending. The federal government will borrow even more money to pay for it.

However, the city cannot do that. It must balance its budget despite declining tax revenues. In June, long before the financial meltdown on Wall Street and in the international financial marketplace, the city faced a deficit of $2.3 billion in fiscal 2010 (beginning July 1, 2009) and deficits averaging $5.1 billion in the next two years. Those deficits will be much bigger when the mayor proposes his modification in the city's financial plan in late October or November.

Despite the enormity of the city's problems -- and in contrast to the lively national debate about conservative vs. progressive tax and spending options -- New Yorkers heard very little public discussion about the options available to the mayor and City Council until Council Speaker Christine Quinn's comment in mid October. Absent the debate, the mayor has quietly pushed ahead with conservative actions and proposals. His initial response to the Wall Street crisis in late September was to repeat last year's mid-year modification and ask his agency heads to come up with spending cuts of 2.5 percent in the current fiscal year and 5 percent in the next fiscal year. This saved roughly $1 billion the first time.

What the mayor would do next if needed, given several comments he's made, is rescind the 7 percent property tax rate that has been in effect for two fiscal years. For the last half of this fiscal year (January 1 to June 30, 2009), this would increase property tax revenues by approximately $700 million. But that burden would hit every New York homeowner or renter (renters pay a substantial part of their landlord's property tax).

An alternative would be to increase the personal income tax rate. Mayors David Dinkins and Rudy Giuliani raised the rate on this more progressive tax in difficult times. Bloomberg did as well. In his November 2002 mid-year modification, he restored a top tax rate of 4.45 percent. That top rate is now 3.65 percent.

In a speech on Oct. 15, Quinn supported the idea of an income-tax increase. ""We'll need to look at personal income tax changes, and we need to consider other ideas," she said. So far, the mayor has not publicly taken a stand on this idea.

The elite group of 30 bankers, developers and other prominent New Yorkers who have publicly supported the mayor's rescinding of term limits would seem to be a perfect group to support the mayor and City Council in a progressive, share-the-sacrifice agenda that would balance the city's economic and budget needs with the needs of the city's residents.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Tackling Campaign Finance Reform

Campaign Finance Panel convened by Citizens Union on September 25th. From left: Dan Cantor of the Working Families Party, Assemblyman Adriano Espaillat, Common Cause Executive Director Susan Lerner and Michael Malbin, executive director of the Campaign Finance Institute.

In politics, it's all about the cash. And this year, as in most even-numbered years, New York State politics is awash in it, with candidates spending hundreds of thousands -- sometimes into the millions -- of dollars to win election to the state legislature.

Fueling a candidate's coffers, critics say, can buy the rich access to government the rest of us do not have. To remedy that, cities, states and the country have implemented varying types of campaign finance reform.

New York City has kept up with the trend. It has adopted public financing and, last year revised its law to increase public matching funds and limit contributions from those that do business with the city.

Of course, New York City has not addressed all the apparent inequities. The Supreme Court has prohibited limits on self-financing -- the justices equated spending one's own money with speech -- meaning a billionaire mayor can spend as much as he wants to win a third term. Recent reports say Mayor Michael Bloomberg could spend as much as $100 million in next year's mayoral contest, prompting some to call on him to voluntarily close his wallet.

New York State has not modified its campaign finance laws in 33 years. Individuals can give almost $56,000 to a candidate for governor, nearly $100,000 to a political party and an unlimited amount to party "housekeeping" accounts.

In an effort to address that, the State Assembly has put forth a proposal that would limit individual donations to $2,000 and include a public matching fund.

Gov. David Paterson has also proposed cutting contribution limits, though he is silent on public financing.

The State Senate, however, opposes any change.

With all of these options floating through the capitol, several experts surveyed the existing laws and how they could be changed at a forum held by Citizens Union -- the sister organization to Gotham Gazette's publisher. The following comments are adapted from the discussion at the forum.

Calculating the Shortcomings -- Blair Horner

What Reform Can Do -- Susan Lerner

How to Change New York -- Dan Cantor

Testing Different Approaches -- Michael Malbin

A Look at 'Corporate' Donations -- Adriano Espaillat

Calculating the Shortcomings

By Blair Horner

My job is to lay out the failings of the campaign finance system and the debate in Albany. To do that, I'm going to give you four numbers: 94,200; 200; less than 1 percent and -- the last is not really a number to the numerical concept -- unlimited.

One: 94,200 is the campaign contribution limit in New York law. The legal limit for our campaign contributions is $94,200 each and every year for the party of your choice. That money can be used to advance candidates under state law.

Two: 200 is the average number of fundraisers that occur in Albany during the legislative session -- 60 days a year, roughly 40 nights on average. They're not holding them for you to go up there. They're holding them for the people who write the $94,000 checks -- Albany's political elite.

Three: Less than 1 percent, that's the number of individuals in the state that write campaign contribution checks in a year. One percent of individuals whip out their checkbooks and make a campaign contribution.

Four: It's the concept of soft money. You say, "I gave $94,200, but I want to give more." Under New York state law you can give more. It's called "soft money." And just to show that lawmakers have a sense of humor, they call it the "housekeeping account." You think of somebody vacuuming or dusting, but it's really a gigantic loophole.

Those four numbers give you a flavor of how we view the campaign finance system. It's a system designed around "pay to play." It's about big donors writing big checks to lawmakers under the assumption that the favor will be returned during the legislative or regulatory process. That's at the heart of what's wrong.

To add insult to injury, New York doesn't have very good system of disclosing information about the finance system. It is riddled with loopholes so that, for example, you can create multiple limited liability corporations that can give as much money as an individual can. The last part of the insult is pathetic and riddled with loopholes. The rules are, for all intents and purposes, not enforced.

We should demand higher ethical behavior. In New York, for example, people can use campaign contributions for their own personal expenditures. If you're a legislator, you can legally use your campaign contributions to subsidize your lifestyle - lease a luxury car, pay for country club memberships, go for trips abroad. The money from interest groups goes to a legislator, who frequently has no opponent. And so that money is basically pocketed.

A more ethical system would deal with those kinds of issues, because the public needs to see not only participation, but also a confidence that the laws are fair and are being enforced.

This system has been in place for a long time, and it has profound impacts. For example, the public is denied competitive elections. Since 1982, 35 incumbents have been beaten in the general election -- that's in roughly 2,500 races. Campaign finance also has an impact on public policy because big donors don't give big money because they feel charitable. This is American capitalism, people expect something in return, and sadly I think they get it.

Blair Horner is legislative director of the New York Public Interest Research Group.

What Reform Can Do

By Susan Lerner

What are we trying to achieve concerning campaign finance? Here are some of the things that people talk about. Each one -- however you order this list and what you leave off this list -- has a very important impact on what you have to choose for the campaign finance system.

One possibility is that you open the ballot to a greater pool of candidates. Reform can provide people without personal wealth or without wealthy friends or access to a lot of money the ability to compete for private office.

It can encourage broader participation in support of candidates, increase competition for office, with more people running. It could level the playing field among candidates; free candidates from constant fundraising; emphasize the role of individual voters, rather than special interests and corporate interests -- organized people, not organized money; and let more viewpoints reach the voters, because candidates have the ability to get their word out more effectively.

If you emphasize opening the ballot to a greater pool of candidates and give those without personal wealth or wealthy friends an opportunity to run an effective campaign -- if that is your primary, or perhaps, your only goal -- then you are going to be inclined toward a matching fund system like the one that we have in New York City. These are found in several other cities around the country and in just a very few states that adopted their campaign finance programs about 20 years ago, about the time New York City adopted theirs, because a matching funds system was sort of the campaign finance reform idea du jour.

Now if you are looking to increase competition for offices, free candidates from constant fundraising or lessen the impact of campaign money on public policy, then you tend to advocate what we call "clean money" or "clean elections." That's the more current fashion du jour. It is what we have in Arizona, Maine, now Connecticut, a pilot project in New Jersey and in North Carolina for judicial and for down-ticket state-wide races.

Clean money is a system where you qualify to run by collecting a set number of $5, or in some cases $10 donations -- never more than $100 -- from a certain number of people in the district in which you're running. You don't collect more, you don't collect less, and once you have sufficient money to qualify, you get a block grant. Everybody who qualifies gets the same amount of money. If you're outspent, you get what we call Fair Fight Funds, which are matching funds.

In Arizona, this is funded primarily through a surcharge on civil and criminal penalties. It comes out of a general fund in Maine, and they have a tax check-off for judicial races in North Carolina.

So we need to think about what are we are trying to achieve. What are our policy goals? We need to get some clarity on that and then work backward to help us shape what we should use for the right public funding system.

Susan Lerner is eexecutive director of Common Cause/NY

How to Change New York

By Dan Cantor

The goal of campaign finance reform here is less about getting private money out -- I don't think that will ever happen -- than getting public money in. We want to reduce the advantage that the wealthy and the well connected have.

Let's build on the New York City system. It's not perfect but it's familiar. It's pretty good.

The introduction of the robust matching fund system has totally changed New York. Those of us who try to recruit people to run for public office can tell people who come out of a history of service to a community group or a union, "All you actually need to do is raise $17,000 and the city's going to write you a check for $90,000." If you can't raise $17,000, you probably shouldn't run for office.

The State Assembly, which has been pointed out, has a pretty good record on this. The Assembly has passed a good bill. The bill backed by Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver is quite interesting. It's a hybrid that combines elements of New York City's "matching system" with the so-called "clean money system" that has passed in Maine and now Connecticut. The vast majority of the Senate Democrats are on record publicly in favor of that bill.

The reason we don't have public financing in New York State is because of the State Senate. It remains in Republican hands. There will be no campaign finance legislation in New York State as long as Republicans hold the State Senate.

Now once the Democrats get the State Senate that doesn't guarantee we will get it. Senate Democrats are desperate for the support of people like us, and so they're making promises now that we think we can enforce very early next year. We are trying to get them obligated to actually pass campaign finance, otherwise they will become hooked, like drug addicts, on the same finance cash that has hooked the Republicans for so many decades. The whole thing is getting it done early.

We also need some help with the governor, who despite his long-term commitment to campaign finance is singing the blues theses days: He can't do it, because public financing will cost too much.

Dan Cantor is the executive director of the Working Families Party.

Testing Different Approaches

By Michael Malbin

We have often heard it said that the goal of campaign finance reform should be to get big money out of politics. You cannot prevent determined rich people from spending their money to influence politics. You can regulate direct contributions, but not independent spending. As a result, I agree with the statement that you have to "forget about getting private money out of politics." But I do not agree that "the goal is (simply) to get public money in." Public money may be desirable, but it is a means. It's not an end.

When political scientists describe goals, we acknowledge the negative or preventive goals stated by courts: avoiding corruption or the appearance of corruption. But we typically look also at affirmative goals: competition, expanding the pool of candidates, and greater and more equal public participation.

Much of the Campaign Finance Institute's work over the past several years has involved exploring the expansion of participation. The idea was to ask whether we could promote equality by building up the base -- the small contributors -- instead of just squeezing down on the top.

This has been a good year for small donors, largely because of the candidacies of Barack Obama and Ron Paul. From those campaigns, some have gotten the idea that the Internet would solve everything. I disagree. Technology is important, but public policy has an important role to play.

As political scientists, we can specify goals, but we are agnostic about how to achieve them. Our work at the Campaign Finance Institute has involved looking at a series of states, using extensive survey research and data analysis, to see whether public policy really does or can make a difference.

In most states, campaign contributions come from a few donors at the top.

Minnesota is unusual (See chart here). Donors who give no more than $100 account for 45 percent of the money. Minnesota has 100 percent rebates of up to $50 for donors who give to publicly financed candidates -- ones who agree to limit expenditures in exchange for public money.

The New York distribution is not unusual (See slide). Donors who gave zero to $100 donors accounted for only about 2 percent of the money raised by state candidates in 2006; donors who gave an aggregate of $1,000 or more accounted for 40 percent, and nonparty organizations another 39 percent.

But we then asked this question: Can we make states like New York look like Minnesota? In some obvious ways, no, but are the differences just a matter of political culture and background?

So we went ahead and modeled three different kinds of reforms, testing each one for its impact separately and in combination.

First, we assumed lower contribution limits, hypothesizing a $2,000 limit per candidate. Second, we assumed public matching funds -- multiple matching like New York City's (See charts here).

Finally, we asked what would happen if you also enacted policies that would get more people to play -- those small donors giving less than $100? Suppose -- either because you put in a tax credit or a rebate for small donors -- you could get the percentage of people who contributed up to 3 percent? Less than 1 percent of New York's voting age population contributed to any candidates in the 2006 state election. The number in Minnesota was 5 percent. (See Charts)

It turns out that building up the bottom like this could have a huge impact. And public policy -- including rebates, tax credits or matching grants -- can be structured to help make this happen.

The key lessons are first, that policy choices can change the situation radically and, second, that there is more than one way to reach the same goal. So it is important, when you talk about campaign finance reform, to think about what it is you're trying to get to, not just what you're trying to get away from.

I would argue that one of the key goals is to get more people involved in the process. We know that getting more small donors involved also means more volunteers. There is two-way feedback between giving and doing. Getting people involved is valuable for its own sake, so it's important when formulating campaign finance policy to think carefully about how best to encourage this goal.

Michael Malbin is executive director of the Campaign Finance Institute and professor of American politics at Rockefeller College, University at Albany

A Look at 'Corporate' Donations

By Adriano Espaillat

I will speak to you from the perspective of a consumer, since I have benefited from public campaign financing. In 2005, I probably wouldn't have been able to run for the borough presidency without some public financing involved. I came out in the middle of about 10 candidates running. I raised about $600,000 and was able to get significant matching funds, and I think that made my candidacy a more competitive one.

I am a supporter of public financing and am a sponsor of the Assembly bill that has been passed. I hope that some day that will come to fruition at the state level as it has at the city level, where it has fostered and encouraged many folks to run for office and represent their communities.

One goal, of course, is to take soft money out of politics. Another one is to make the government more transparent and accessible to the general public. The public finance system here in New York City has accomplished some of that. If you take a look at the makeup of the City Council, it is more reflective of the composition of the city of New York. People who may not be rich or middle class are still able to raise some dollars and be competitive in a race and represent their communities.

In the effort to get hard-core money out of politics, there is a proposal to restrict campaign contributions. To most people, that means limiting contributions from pharmaceuticals and the big insurance companies and the people that have a vested interest in what happens in Albany and Washington. But what happens to the Korean fruit store who has a corporation and like many New Yorkers is not a citizen? One third of New Yorkers are foreign born. These people play by the rules, they pay taxes, they send their kids to public school, and they ride the subway. What happens to them? How do they get involved in the electoral process? How do they have an impact on who is going to represent them or the district where they have their stores?

Many of them choose to write a $500 check to a candidate. I don't see it as trouble that a Dominican bodega owner or a Jamaican beauty shop owner or a Korean fruit storeowner writes a corporate $500 check for me. I don't thing that's twisting my arm. I think it's very much part of America and that's granting access to government to people.