Income Numbers Show a Changing City

Incomes rose the most in the Bronx? The growth in earnings in manufacturing surpassed that for finance and information? New York City residents fared better than higher income commuters?

These sound like trends that might have occurred in decades past. Actually, though, they happened fairly recently -- from 2000 to 2005 -- according to the personal income series compiled by the U.S. Commerce Department. The Commerce Department's Bureau of Economic Analysisputs this report together using tax records and state administrative records on employment. You rarely read about such data in news reports, partly because the information is only annual, and there is a lag between the period of time covered by the data and its release. But despite that, this data tell us important things about the economy.

In 2005, the total personal income of New York City residents was $343.4 billion. This was 16 percent greater than in 2000, before adjusting for inflation. Since the city's population grew by 2.4 percent from 2000 to 2005, per capita income increased 13.3 percent. For the first half of this period (through mid-2003), the city's economy was declining. The downturn resulted from the national recession, the aftermath of 9/11 and the bursting of the Wall Street and technology bubbles. But the city's economy started to recover in the last half of 2003, and by 2005, total employment in the city had recovered although real total personal income (i.e., after adjusting for inflation) did not regain the 2000 level until 2006.

Consumer inflation was 3.8 percent in 2006, and the city's Office of Management and Budget projects that personal income increased by 6.6 percent in 2006.

EARNINGS FOR THOSE WORKING IN NEW YORK CITY

Personal income counts the income of all persons from all sources. It includes wages and salaries, proprietors' income, employer-provided health insurance, dividends and interest income, social security benefits, and other types of income. By far the largest component of personal income is a category called "earnings," which includes wages and salaries, and proprietors' income. In New York City in 2005, earnings totaled $351.7 billion. This exceeded residentsĂ total personal income of $343.4 billion because commuters who live outside the city took home nearly a quarter (24 percent or $83 billion) of the earnings generated in the five boroughs. Employee compensation accounted for 86 percent of New York City earnings by place of work and proprietors' income was the remaining 14 percent.

From 2000 to 2005, net earnings received by city residents grew more than twice as fast as earnings of commuters (an increase of 17 percent versus 7 percent). This reflects the fact that a lot of the jobs lost during the downturn early in the decade occurred in high-paying industries such as financial services, information and professional services that tend to have high concentrations of commuters. Also, much of the employment growth in the first half of this decade was in health, social and educational services, industries that tend to employ proportionately more city residents than commuters.

Employer contributions for pension and health insurance ñ which are included as employee compensation -- increased by nearly a third from 2000 to 2005 or more than three times as fast as the growth in wages and salaries, reflecting the steep rise in health insurance costs.

SELF-EMPLOYMENT UP, WAGE AND SALARY EMPLOYMENT DOWN

One of the unique features of the personal income series is that it includes data on the number and earnings of those who are self-employed. Self-employment grew rapidly in New York City from 2000 to 2005, increasing by 37 percent, reflecting an increase of 207,000 persons. On the other hand, New York City wage and salary employment registered a decline of 3 percent, or 120,000, over this period. A part of this spurt in self-employment results from the practice by some businesses of improperly classifying their workers as independent contractors. Since 2000, the earnings of the self-employed grew only half as fast as the number self-employed (18 percent vs. 37 percent). For wage and salary workers, total employee compensation (wages plus employer contributions) increased by 14 percent even though their number declined by 3 percent.

THE MAJOR COMPONENTS OF PERSONAL INCOME

The table below shows the three main categories of resident personal income, their shares of the total, and the 2000-to-2005 growth rates for each. (Capital gains, from stock or real estate are not considered "income" in this set of statistics, but are considered changes in the value of an asset.) The decline in interest rates largely accounts for the decline in the dividends, interest, and rent income.

Transfer payments come to city residents from state and federal social insurance and safety net programs. They increased by 30 percent from 2000 to 2005, largely because of the increase in Medicare and Medicaid payments. Medicare grew by 50 percent and Medicaid increased by one-third over this five-year period. These sizable increases have been due to rising health care costs as well as significant growth in the number of beneficiaries, particularly for Medicaid. Medicare and Medicaid payments go to health care providers and the total amount is nearly four times as great as the Social Security benefits paid to city residents. In 2005, city residents received $11.1 billion in Social Security while Medicare payments to health care providers in New York City totaled $12.8 billion and federal and state Medicaid payments to city providers totaled $27.7 billion.

The fourth major category of transfer payments includes various income maintenance benefits, which total $8.9 billion. Here the largest category includes the Earned Income Tax Credit, which gained by 44 percent from 2000 to 2005 and was $3 billion in 2005. Federal food stamp benefits totaled $1.4 billion in 2005, 50 percent higher than five years earlier, a growth that reflects improved enrollment procedures and a high level of continuing means-tested need in New York City.

Unemployment insurance was designed to function as an ìautomatic stabilizerî during economic downturns to help laid-off workers maintain some level of purchasing power. The income data bear this out. During the recession, unemployment compensation nearly tripled, rising from $800 million in 2002 to $2.2 billion in 2002. By the time the recovery was well underway in 2005, unemployment benefits had receded to $1.1 billion.

EARNINGS BY INDUSTRY: THE EXPECTED AND THE UNEXPECTED

The income series includes figures on earnings (wages and salaries, and proprietorsĂ income) by industry, but only for the 2001 to 2005 period. Overall earnings increased by 12.4 percent over these four years. Among the larger industry groupings, private educational services registered the fastest growth, with earnings increasing by 37 percent. Health care and social assistance came in second with a 24 percent increase. Four sectors had 21 percent gains: real estate, retail trade, arts and entertainment, and accommodation and food services. While the number of jobs in the manufacturing sector declined sharply, earnings increased by 11 percent -- several times faster than the 3 percent growth in finance and insurance sector.

The information sector had a 10 percent increase in earnings over the four years from 2001 to 2005, although the pattern for individual industries in this sector varied. Earnings in broadcasting gained by 39 percent, while motion picture production had a 9 percent drop in earnings, telecommunications a 10 percent earnings decline, and earnings for those working for Internet service providers and related activities fell by 22 percent.

BRONX LEADS THE WAY

One of the most interesting trends that emerges from the personal income data for 2000 to 2005 is that the ever-resilient Bronx had the most impressive income and earnings growth among the five boroughs. As the table below demonstrates, people living in the Bronx experienced total income growth of 24 percent over this period, half again as high as the cityĂs overall 16 percent income growth. On a per capita basis, incomes grew by 21.5 percent in the Bronx, also outpacing the other boroughs, although it still has the lowest per capita income -- $23,513 compared to the citywide average of $41,803. Jobs and businesses located in the Bronx showed similar gains, with earnings growing at twice the citywide rate. Brooklyn came in second for these three measures and Manhattan brought up the rear.

The relatively faster income growth in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens over the 2000 to 2005 period is largely due to New YorkĂs changing job picture and who has benefited from it. The number of jobs in health, education and social services has grown, and these industries are more likely to employ outer borough residents. On the other hand, Manhattanites, like commuters, are more likely to hold jobs in higher-paying financial services, a sector that has recovered somewhat but was hard hit by the recession and the bursting of the Wall Street and dot.com bubbles.

Health, education and social services now account for 10 times more earning in the Bronx than manufacturing does and provide 36 percent of total earnings from jobs in that borough. Earnings from the banking industry were flat in Manhattan, where most bank headquarters are located, but rose appreciably in other boroughs ñ by a huge 83 percent in the Bronx, for example ñ because of an increase in the size and number of branch banks. Brooklyn also saw strong earnings growth related to the relocation of some financial securities operations from Manhattan in the wake of 9/11.

Despite all this, Manhattan residents still have far higher income level than the residents of the other four boroughs. Even with many low-income residents, Manhattan's per capita income level was $93,400 in 2005, two-and-half to three-and-a-half times the per capita income levels for the other boroughs. All indications from other sources, including tax data, suggest that incomes at the top of the distribution have been growing rapidly since the recovery got underway. A future column will examine trends in New York City's income distribution.

James Parrott is deputy director and chief economist of the Fiscal Policy Institute (www.fiscalpolicy.org). He has been studying and writing about the New York economy since he landed in New York City a quarter century ago.Â

No Quick Riches for New York's Twentysomethings

After years of expensive education,

a car full of books and anticipation,

I’m an expert on Shakespeare and that’s a hell - a lot

but the world don't need scholars as much as I thought.

Jamie Collum’s “Twentysomething,” a wry anthem of the newly graduated, describes the fate of many of New York City’s twentysomethings better than some of the rosy pronouncements heard recently. While USA Today and others claim that this is a banner year for graduates, the good news mainly applies to students in several specialty fields, such as business, engineering, computer science and nursing. And the gains are more pronounced among recent graduates of prestige universities.

While young people with bachelor’s degrees in business, accounting and engineering command salaries of about $50,000, most of this year’s liberal arts graduates will see a salary of about $31,000 -- similar to the pay received by a starting public-school teacher. This represents a decline of 1 percent since last year.

For those with all levels of education, including college and beyond, wages today have yet to catch up with the “real” wages (in other words, adjusted for inflation) that twentysomethings received in 1970. Men have seen their real wages fall substantially and women outside of New York have seen only very modest gain. Table 1 presents median wage figures, taken from Census data, for all full-time workers in their 20s from 1970 through 2005. Wages for all twentysomethings in New York City and in the United States are still below those received in 1970.

Over this period, women in New York City saw an amazing jump in their wages compared with those of men in their age group. While women in the city earned, on average about $7,000 less than men in 1970, by 2005 they made about $5,000 more. Interestingly, women in the country as a whole have closed the gap between their earning and those of men, but still lag behind.

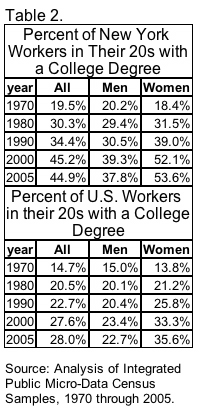

At the same time, as Table 2 shows, women eclipsed men in the proportion who were at least college educated by 1980. In New York City, over 53 percent of working women in their twenties have at least a college education compared to about 38 percent for men. Although working women in their 20s across the country are much more highly educated than are men, women in New York City, particularly those in Manhattan, are much more likely to be single, earn more money, and have more education than women living in the rest of the United States.

At the same time, as Table 2 shows, women eclipsed men in the proportion who were at least college educated by 1980. In New York City, over 53 percent of working women in their twenties have at least a college education compared to about 38 percent for men. Although working women in their 20s across the country are much more highly educated than are men, women in New York City, particularly those in Manhattan, are much more likely to be single, earn more money, and have more education than women living in the rest of the United States.

The data show a number of other striking trends:

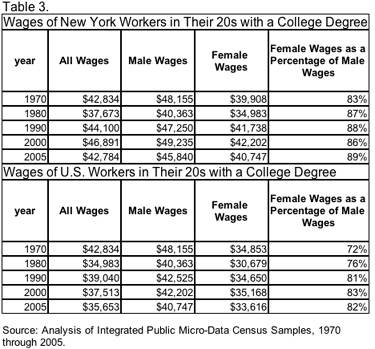

• For college graduate males, wages have declined in New York City and nationally, while women have had very modest gains in the city, but not in the U.S.

• For those with advanced levels of education (beyond a bachelors degree), wages of females have soared in NYC, while male wages have only crept up. Nationally, male wages have fallen, while female wages have stood still.

• For the college and even better educated, the wage gap between men and women declined, but it is still much smaller in New York City than nationally.

Furthermore, the gap between the wages of the most highly paid and the least highly paid of the college graduates in their 20s increased, as well. In 1970, those in the top quarter made at least $53,476. By 2005 that figure grew to $61,120. But those in the bottom quarter, who in 1970 made at most $35,917, saw their wages drop to $35,560 by 2005. So even among the young, affluent New Yorkers are becoming even more affluent, while the less affluent are not even holding their own. For those with education beyond college, the pattern is very similar: Those in the top quarter in 2005 made at least $77,419 up from $67,577, while those in bottom quarter made no more than $42,784 only slightly more than $41,504, the amount that they made in 1970.

In short, the lyric of Collum’s “Twentysomething” hits the mark for many in New York City as the picture is far from cheerful. But they have some consolation. If young males with a college or better education in New York City and the United States have seen their wages decline, those without college are much worse off. It may not better today than it was 35 years ago to be a college graduate twentysomething, but it is certainly better than being a twentysomething without a college degree.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Sealed with a Kiss: The 2008 Budget

|

The new budget removes the sales tax on clothing -- even luxury items. |

Years ago, council members would have been biting their nails and eyeing the clock as it ticked toward midnight on June 30, the deadline for reaching a new city budget. But at 4:30 p.m. Friday, several legislators played whiffle ball on the steps of City Hall and others were out of the door, most likely to celebrate one of the earliest and speediest budget negotiations in recent memory.

With a kiss and handshakes, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn announced a $59 billion budget agreement last week. On Friday, the full council swiftly and unanimously adopted it -- 16 days before the deadline. The agreement delivered a 7 percent reduction in property taxes - 2 percent more than Bloomberg proposed in January. The agreement was also in the nick of time for tax bills to be dropped in New Yorkers' mailboxes.

With an estimated $4.4 billion budget surplus, the largest in the city's history, the agreement produced little controversy or disagreement. But as in every other budget, some projects, cause or constituency was left out. And for the 2008 fiscal year, which begins July 1, advocacy groups and fiscal watchdogs question whether the city could have given some of its record-breaking surplus to help public housing and to provide real relief for two-thirds of the city's residents who rent, rather than own, their homes.

What the Council Got

In April, the council was already celebrating several budget victories and compromises with the Bloomberg administration.

Between the presentation of the mayor's preliminary budget in January and the release of the executive budget in April, the council had won Bloomberg's endorsement for several key initiatives: $320 million over 10 years to acquire land in the Catskill/Delaware Watershed and the creation of 10 state-of-the-art health care facilities.

And last week, the council's victories seemingly outweighed its defeats. Among the programs secured in this year's budget are expanding library hours so all branches will be open six days a week, at a cost of $42.7 million, and increasing the number of full-day, pre-kindergarten slots. Other allocations are geared toward upgrades for the 311 non-emergency hotline system, bulletproof vests for auxiliary officers and funding for individuals suffering health effects from 9/11.

This year's budget also guaranteed an additional $21 million for the City University of New York to retain faculty and slated $500 million for the Health Care Trust Fund to fund benefits for future and current retirees.

The council also ensured funding for the following programs:

- $25 million over two years to maintain and repair more than 12,000 units of affordable housing

- $200,000 to the Low Income Investment Fund for childcare centers' facility upgrades

- $5 million to the district attorney's offices and the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor to investigate child abuse, internet crimes and gun violence

- $3 million to fund education and fitness programs

- $5.6 million for high school drop out prevention

Homeowners Versus Renters

Some have termed the 7 percent tax break for all property owners as the greatest achievement in the budget. Real estate assessments are steadily skyrocketing – one estimate is a hike of 19 percent in 2006 – and the property tax cut is aiming to at least stabilize the amount homeowners pay. On top of the 7 percent rate decrease, each homeowner will also receive a $400 tax rebate at a total cost of $256 million.

To some housing advocates and members of the council, one constituency is blatantly missing: renters.

In her state of the city address this winter, Quinn said a renter's rebate was one of her top budget priorities. At a cost of $261 million, the tax credit would have applied to approximately 1.1 million households, putting $300 back in their pockets.

That initiative needed state approval and so was abandoned.

"We will continue to fight to make sure that renters get the relief that they deserve," Quinn said prior to the budget's approval on Friday.

Some attribute the failure of a renter's rebate to a lack of support from the mayor. Finance Committee Chair David Weprin said if the council and the mayor do not both lobby Albany for support, an initiative is unlikely to receive approval.

|

By the time the budget was passed, the renter's rebate, touted in |

"We pushed for it from the City Council's point of view," said Weprin. "Generally Albany doesn't take positions that affect New York City, unless the council and the mayor are on the same page."

Housing advocates were disappointed by the council's failure to win the renter's credit. Because real estate assessments have been climbing, rents have too, said Jenny Laurie, director of the Metropolitan Council on Housing. When the average renter in the city pulls in just $32,000 a year, a break would have been nice, she added.

"The renter's (credit) would have done something really great," she said. "It would have actually handed cash back to tenants at the end of the year."

Although renters and people with lower incomes may not see direct tax relief, Laurie said the tax breaks for homeowners could trickle down to the renter and keep prices stable at least for now.

"Its fair to say the property tax rate cut will largely benefit New Yorkers with higher incomes than renters," said Doug Turetsky of the Independent Budget Office. "Renters will not benefit from that break nor will they get from any portion."

Some fiscal experts said the entire tax break package was primarily geared toward more affluent New Yorkers. The budget eliminates the sales tax for clothing and shoes and provides a break to small, unincorporated businesses.

"The elimination of clothing sales tax over $110, the only parties that benefit from that are going to be high income consumers whether they're city residents or not," said James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute, a nonpartisan research organization. "What's an issue is that homeowners are getting two bites at the apple, the tax cut apple. Renters haven't gotten anything."

Some lower income people will benefit from the new child care tax credit. Offered for the first time at the city level and proposed by Bloomberg, it will provide $42 million to working parents who earn less than $30,000 and who have children under 3 years old. This would eliminate the need for 33,000 families in the city to pay city personal income taxes, according to the Independent Budget Office.

But according to a report from the Independent Budget Office, the credit is not a win-win for all working parents. Some 167,000 New Yorkers, who do not pay state or federal taxes, still must pay the city personal income tax.

Snubbing the Housing Authority

One group of renters fared particularly badly in the new budget - those who live in apartment buildings operated by the New York City Housing Authority.

In 2006, the New York City Housing Authority predicted a budget shortfall of approximately $30 million for 2007. It has since grown to more than $200 million. Faced with such a large deficit, the authority, which oversees public housing projects, has had to cut costs, increase rents, drastically reduce its workforce and sell off land to raise revenue. Even with a $130 million commitment earmarked in the executive budget, the agency still has a $51 million deficit for its budget this year.

Last year, the mayor appropriated a one-time only $100 million subsidy and council pushed for another $20 million to bail the agency out of fiscal crisis. Without a similar subsidy this year, the authority could face even more cuts, some housing advocates said, that threaten the amount of public housing in the city.

"We're asking, where is the city's help for dealing with (the New York City Housing Authority's) operating deficit?" senior housing policy analyst for the Community Service Society Victor Bach asked. "We know the city is planning to buy some vacant land, but that's a quid pro quo."

Although the agency's budget woes are a result of decreased federal and state aid, some advocates said the city should have assisted the housing authority -- and given its huge budget surplus, it could certainly afford to do so.

Councilmember Erik Dilan of Brooklyn said the council should look toward providing some help to the authority in the future.

"I think as we move to the fall there are some very serious concerns this body needs to take a look at regarding the New York City Housing Authority," Dilan said. "It would be very nice, along the way, if we could get some help from the state and federal governments."

The City Council successfully pushed for funding to open libraries six days a week, restoring services cut after 9/11.

Looking Ahead

While the budget surplus helped make this a relatively easy budget year, city officials caution that times will not always be so rosy. This year's surplus, attributed to gains on Wall Street and better than expected tax revenues, cannot be guaranteed in the future.

"Just five years ago the city faced financial ruin," said Councilmember Michael McMahon prior to the budget vote. "And now, we're opening libraries."

In what many officials have called "prudent" spending, the city put $2.3 billion toward covering debt services in fiscal year 2009 and 2010.

After all, if times get rough again, City Council members might have to put their whiffle bats away -- and council members and the mayor could be trading growls instead of kisses.

Â

With Pizza, Pinball and Panache, Boardwalk Vendors Face Changes

Paul Georgoulakos: "Coney Island raised my family."

As he bastes shish kebabs with a sweet-smelling barbeque sauce, 78-year-old Paul Georgoulakos, admits, Coney Island is "all I know." But the Coney Island Georgoulakos knows may soon change forever, leaving an uncertain future for his food stand and many of Coney Island's other mom and pop businesses.

Coney Island has long been the city's neglected — if beloved — playground. After its glory days of hotels, Dreamland and Luna Park, it remained the city's daytime getaway – cheap and a little sleazy -- for generations. But now Thor Equities, a large development corporation, has bought more than 12 acres in the heart of Coney Island and hopes to build a hotel, luxury condos and a glitzy entertainment area. Thor's vision for Coney Island does not include some of the area's amusements, including Astroland, whose lease was not renewed by Thor and will close at the summer's end. Some of the rides could be moved elsewhere. (The Cyclone and Wonder Wheel, however, will remain.)

Thor still confronts obstacles in making its high priced vision a reality. The city planning department has said it does not think Astroland site is appropriate for residential development, and under the current zoning, such development is prohibited. Thor Equities has been lobbying for rezoning that would change that. Meanwhile the city is developing a plan for the community, and other developers and property owners are trying to figure out how they fit in (see related story)-->.

A LIFE ON THE BOARDWALK

Small vendors like Georgoulakos remain in a state of limbo as they wonder whether or not their leases will be renewed. But Georgoulakos says he has survived difficult times at Coney Island before. When his milk stand burned down in 1950, he moved to the other side of Coney Island and built another one. Then, in 1970, Georgoulakos and his friend Gregory opened Paul and Gregory's, a restaurant that has served the Boardwalk with funnel cakes, pizza and more ever since.

The reality though, is that for many of the area's small businesses along the boardwalk, this season will be the last. Even if Thor Equities chooses to renew a business' lease for the coming year, the development is likely to bring gentrification and higher rents and that will squeeze out Coney Island's smaller entrepreneurs.

|

Manny Cohen: "They're going to make it look like Las Vegas." |

For now, though, the area's small-business owners have work to do. Clams must be baked, ice cream scooped, games painted and readied for throngs of visitors. And for the colorful cast of characters who continue to make Coney Island a destination unlike any other, one thing is certain: The show must go on.

It is still early in the season but Gregory and Paul's has a line of customers waiting to taste one of Georgoulakos' chicken kebabs, hot off the grill. A younger employee shouts out into the boardwalk. "Funnel cakes! Hot pizza! Hot dogs! Hot chocolate! Come and get it!" On the Boardwalk, it all is available and almost anything goes.

"Every year has been a good one," Georgoulakos says from behind the grill. "This year [though] is not so good," he said. Still, Georgoulakos is not angry. He talks of the sense of community he has found in Coney Island, and of a retirement that will allow him to spend time with his wife, who is not well. "There will always be someone else to take my place," he says. "I hope they do as good as I did because I did good. I'm happy. Coney Island raised my family."

He fears, though, that the Coney Island that supported his family way be doomed. "Coney Island without the amusement area? I don't know what you're going to call it," he said.

POOR PEOPLE'S PARADISE?

Not all the owners are at peace with their business' uncertain future. After 27 years on Coney Island, Manny Cohen, the owner of the Coney Island Arcade, featuring pinball machines and video games, is furious. His black tee-shirt is emblazoned with the hot green letters "KOOL," for the cigarette's logo. Tugging at his red, white, and blue suspenders with his thumbs, Cohen's defiance grows as the conversation goes on. "I hope they don't give me a lease," says Cohen. "I'll be out by September."

Coney Island, says Cohen, has been the "poor people's paradise." But he thinks that will change if Thor Equities builds its luxury condos and mixed retail space. Walking past a maze of arcade games and neon signs stored in his garage, Cohen enters his office and settles rather reluctantly into a well-worn chair. "After one summer or two, they're going to shut the beach on the poor people," he says. "There is no way Thor [Equities] can afford to open an amusement park after the price they paid for the land. "It's all a hooplop. They're going to make it look like Las Vegas."

But Cohen remains sanguine about his own future. "I'll move on," he says. "I'm going to do the very same thing," he said. Where will he go? Ironically enough – to Las Vegas, where Cohen says many of his friends may relocate their businesses. "There's a life beyond Coney Island," says Cohen. "If that's what the city wants."

Cohen wants Mayor Michel Bloomberg to send a couple of representatives to Blackpool, the oldest amusement park in England, so they can see how "civilized nations" preserve their historic amusement parks. "I'll donate the money for the trip if the city doesn't have it," he says. (The president of the Coney Island Development Corporation, Lynn Kelly, says she has indeed visited Blackpool, the closest thing in the world she could find to Coney Island, but still very different.)

Coney Island: "Every year has been a good one."

REFUGE FOR A FREE SPIRIT

Further down the boardwalk next to Nathan's is Cha Cha's Bar and Café. Formerly known as Club Atlantis, over the years, it has featured a surprisingly array of talent. Tito Puente, Steve Allen, and Jimmy Durante have all graced Cha Cha's small neighborhood stage. Black and white photographs, many of them relics from Coney Island's early days, mingle with newer color shots on the wall.

A man named J.T., who calls himself a "long-time friend" of Cha-Cha, the owner, sits with a cigarette at the bar and offers a brief history lesson. Cha Cha's he says, is only in its fifth season, but is already a mainstay on the boardwalk and was seen on "The Sopranos."

"I grew up [in Coney Island] and worked on the Boardwalk," J.T. says. "That's my baby picture on the wall," J.T. says, pointing to the frame. "I was booking entertainment by the time I was 12."

J.T. doesn't know what's going to happen to Cha Cha's or the Coney Island's other small businesses. "Only God knows," he says. But he hopes he can remain. "I'm a free spirit but this is the place to be." J.T. says.

A Nathan's Hot Dogs employee rushes in. "J.T.! Do you have $200 in change?" she asks. J.T. laughs, "What are you asking us for? You're Nathan's! You're a huge conglomerate!" The employee tries again: "So you don't have $200. "No," J.T. says. "But if we did, I'd give it to you."

Â

What the Campaign Finance Bill Would Do -- and Not Do

The sweeping campaign finance law introduced by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and leaders of the City Council last week is being championed as the most progressive campaign finance reform proposal in the country. Good government organizations applauded Bloomberg and Council Speaker Christine Quinn and congratulated them on taking on "pay to play" campaign contributions.

But, whatever its eventual impact might be, some experts said candidates, including members of the City Council, may be able to skirt its requirement for the 2009 city elections. If deadlines outlined within the legislation go unmet, candidates for the next citywide election would not have to comply with the tougher standards.

With dozens of council members facing term limits, many plan to seek another office and are already banking campaign contributions. Some of those donations would be banned or limited by the proposed legislation, giving some council members an advantage in the election and others an incentive to fundraise as fast as possible.

Tackling Pay to Play Per Se

Introduced at its stated meeting on June 5, the proposal (Intro 586) attempts to sharply limit the influence of corporate and special interests in city government. Having already been recognized for its public financing of campaigns and other aspects of its campaign finance law, the New York City government now proposes to reduce contributions from those with government contracts and from lobbyists by 90 percent.

The bill would:

- Reduce the cap on campaign contributions from government contractors or others who "do business" with the city, such as lobbyists or land use applicants from $2,750 to $250 for council races, $3,850 to $320 for borough-wide races and $4,950 to $400 for citywide races.

- Provide $6 of public financing for every dollar acquired in the first $175 in a contribution, instead of the $4 for every dollar up to $250.

- Prohibit matching public funds for contributions from those who "do business" with the city.

- Include limited liability companies and limited liability partnerships in a ban against corporate campaign contributions.

- Expand the definition of fundraising intermediaries, who are subject to disclosure, from those who deliver campaign contributions to those who solicit funding as well.

- Require that a race be competitive before a candidate can receive public financing.

|

Stated Meeting: Whistleblowers and Immigration While campaign finance reform captured much of the attention at the City Council stated meeting on June 5, the council also overturned Mayor Michael Bloomberg's veto of a bill to protect whistleblowers who report an act that endangers a child and approved a resolution on national immigration reform. The council approved the whistleblowers bill, (Intro 83), by a vote of 49 to 1 with Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr. casting the no vote. The legislation expands whistleblower protections to teachers, social workers and others and prohibits retribution if an individual reports conduct that harms a child. Critics have called the measure redundant and say it is another attempt by the teacher's union to strike back at the mayor for overhauling the public school system. The union had pushed unsuccessfully for a similar measure in 2006. But Council Speaker Christine Quinn called the bill "common sense." And Councilmember Eric Gioia, who sponsored the bill, said, "No one should ever have to decide between the best interest of the child and keeping their job." The override is one of few since Quinn has taken over the council. The council also approved Resolution 842 urging Congress to adopt comprehensive immigration reform, sparking a heated debate at City Hall. Democratic Councilmember Miguel Martinez of Manhattan said the bill proposed in Congress is “totally contrary to what this great country stands for.” He added that an opportunity to get permanent resident status “should not be limited to few.” But Vincent Ignizio, a Staten Island Republican, disagreed. "We're not talking about immigrants," he said. "We're talking about illegal immigrants - those who come to this country and try to jump the line." The resolution calls for Congress – which currently is deadlocked on the issue -- to provide a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants now in the country, to support family unification, and to restore due process to immigration procedures. |

The bill, according to those who worked on drafting it over a six-month period, is meant to empower New York City citizens by emphasizing smaller donations and limiting the contributions accumulated by those with government contracts.

"We set out to do three things: one to make sure we had a fair system, a system that was fair and clear and user friendly for all participants, a system that would encourage New Yorkers to run for office if they wanted to and be a part of our public campaign system," Quinn said at a press conference prior to introducing the bill. "And two, to protect the public's money… and third we wanted this bill to send a message to New Yorkers that all of us in public office work for them."

The Effects of Unmet Deadlines

The law takes direct aim at pay to play, a practice in which a company, person or non-profit contributes to a candidate's campaign fund hoping to influence decisions on government contracts later on. To combat such undue influence, the proposed legislation bans any donations from corporations and, for the first time, limited liability companies and partnerships.

According to a report commissioned by the Campaign Finance Board, in the last citywide election in 2005, $9.4 million out of $42.3 million in campaign donations came from those that "do business" with the city, while in 2001 those that did business with the city accounted for $15.6 million in contributions, or 22.3 percent.

In the proposed legislation, "they have successfully resolved issues that protect the right of the people to participate in campaigns, strengthen the value of small donors while limiting the influence of many big money interests who do business with the system," said Dick Dadey, the executive director of Citizens Union (a sister organization to the Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette).

But some of these measures, such as limits on contributions from government contractors and land use applicants, are accompanied by a timetable. Any delay in the creation of the "doing business" database by the mayor's Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications could affect when the legislation would go into effect. For example, if certain parts of the database are not certified by November 2008, the respective sections of the bill would not go into effect until the next election cycle.

Eric Friedman, a spokesman for the Campaign Finance Board, said officials designed the legislation to allow incumbents and prospective candidates to get accustomed to the new rules. Changing the guidelines quickly before Election Day, officials said, would not be fair to the candidates.

But whether the database, which would contain officers and individuals with more than a 10 percent stake in a contract, can be compiled quickly is another question. The data would have to be compiled within six to 18 months of the bill’s passage.

Despite the tight time frame for the massive amount of data compilation, some said the deadlines could, and should, be met in time for the '09 contest. "The bill makes the mayor ultimately responsible for the development of the databases," Friedman said. "We are certainly going to work with them to provide any assistance."

A spokesman for the mayor's office said the administration was "completely confident" it could meet the deadline, and a City Council spokesman echoed that sentiment, contending Quinn wanted the legislation, which is co-sponsored by 24 other council members, to apply to the 2009 election.

Time to Beat the Clock

In hopes of seeking higher office, more than three dozen officials have already registered with the Campaign Finance Board to begin fundraising for the election more than two years away. Many have collected contributions that would not be permissible under the reform bill, such as donations from liability corporations or gifts that exceed limits anticipated by the legislation for individuals, such as lobbyists.

The legislation is not retroactive; so any funding collected prior to its enactment is free and clear of the more restrictive standards. And with both term limits and contribution restrictions looming, some candidates might be particularly aggressive in courting big donors now – before it is too late.

"When this bill is implemented there will be a timetable with passage and implementation," said Republican Councilmember James Oddo, the minority leader. "Every person seeking office in 2009 will be on the phone to make as much money as possible to beat the clock."

Oddo, who is looking toward a race in Staten Island as borough president, has not yet pledged to support or oppose the bill.

Chair of the Government Operations Committee and one of the bill's co-sponsors, Simcha Felder said it was inevitable candidates would try to beat the legislation's timeline and accumulate as many contributions as possible.

"Unless there could have existed a moratorium for months and months beforehand, there would be a level playing field," Felder said of racing to fundraise. "I can't blame anyone” for fundraising, he added. “They really would be putting themselves at a disadvantage."

And some officials said the current edge is no different from the advantage incumbents and other prominent candidates usually have. "Challengers really don’t get started until the election is closer and on everyone's radar screen," Friedman said. "To that extent, yes, people that have gotten an early start may see some advantage. I don’t know if that’s different from any other election cycle."

For instance, Quinn has already received more than $84,000 in campaign contributions for the 2009 election, when she is expected to run for mayor. Approximately 7 percent of that is from limited liability corporations and partnerships.

A Classic Case: Does the End Justify the Means?

The bill, which will be before the Government Operations Committee this week and is expected to pass the full council, also intends to increase competition and influence of smaller, grassroots groups in citywide elections by upping the formula for public financing and specifying stricter criteria for declaring competitive elections, officials said.

However, some critics disagree on its ability to encourage competitive campaigning. Norman Adler, president of powerhouse, lobbying firm Bolton-St. Johns, said the proposed reforms close lucrative avenues of fundraising in a field with increasingly expensive elections.

"If you're talking about cause and effect, I know what the effect of this is going to be," said Adler, who has already surpassed potential limits on contributions to some candidates in the 2009 race. "It's going to be harder and harder to raise money, and it's going to penalize people."

Hank Sheinkopf, also a consultant, said the reforms could hurt candidates in minority or low-income districts who rely on larger donations from contributors limited by the proposed legislation. If passed, he said, the bill could hamper competition and make it easier for the more affluent, and self-financed, candidate or those with better name-recognition.

"People that contribute to politics happen to have an interest in politics," Sheinkopf said. "Where are these people going to get money from, the guy on the corner? It's nonsense."

Even Bloomberg has recognized the influence his own fortune played in his election.

And as with any other reforms, loopholes and detours will emerge, some said. "You know, how I would get around it?" Adler asked. "I would form a union."

An Equal Playing Field

The legislation largely leaves out one particular campaign contributor with a large influence in city government: unions.

According to the Campaign Finance Board, the top five contributors to City Council candidates in the last citywide election in 2005 were unions or union affiliated political action committees. Some critics said if government contractors are included in campaign contribution limitations, unions should be too.

"Clearly there is an 800-pound gorilla in the room," Oddo said of union's exclusion in the bill. "(The bill) is under inclusive, and it doesn’t address all the incarnations of influence and perceived influence garnered by money," he added.

Others said in retrospect, unions should have been included in the legislation but doing so could have killed the measure.

"They could have never gotten the council to give them support," Felder said if unions had been included. "It was very personal."

But others said the legislation remains notable not for what has been left out, but for what has been included. Several government watchdog organizations, including Citizens Union, Common Cause/NY and the New York Public Interest Research Group have hailed the legislation and used it to contrast the tight rules on campaign finance in New York City with the lax rules for state elections in New York.

"We commend the city for advancing these forward-thinking reforms," said Megan Quattlebaum, associate director of Common Cause/NY. "Now, it's time for citizens to demand that lawmakers in Albany get out from under their shroud of winter darkness and follow in New York City's footsteps by drastically overhauling what remain some of the worst campaign finance laws in the nation."

Questions Remain About the 2008 Budget

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has had a terrific budget year. New tax revenues keep rolling in, driving the budget toward a record-setting surplus. The City Comptroller reported in late May that the surplus may exceed $5.8 billion by the end of June. The fiscal monitors are pleased with the surplus and what the mayor has done with it. But some interesting questions about what to do with that surplus remain as the mayor and the City Council enter into the last weeks of negotiations over the fiscal year 2008 budget.

The mayor always holds the upper hand at this point in the budget year because he controls the revenue estimates that dictate how much city government can and cannot spend. Because the city must have a balanced budget, any money the council adds to the mayor’s executive budget must be paid for by adding revenues and/or cutting other expenses. Nevertheless, in a $60 billion budget there is always some wiggle room.

Tax Cuts for Low Income New Yorkers

With such good budget news, the budget negotiations have been fairly low key. But the mayor has yet to react to the council’s proposal for several relatively inexpensive, progressive tax cuts that would benefit renters, seniors and the disabled.

The proposals, outlined in the council’s response to the mayor’s preliminary budget, would benefit well over a million city households that would not see any savings from the mayor’s generous tax-cut package. That plan – endorsed by the council -- gives residential and commercial property owners $1 billion in savings through an across-the-board (5 percent) cut in the property rate tax cut and a $400 rebate to home owners, who represent only one third of New Yorkers. These savings are proposed to continue through 2011.

The council’s $300 tax credit for renters is progressive in that it only would go to some 1.1 million lower- and middle-income households – families earning less than $75,000, and individuals earning less than $43,000. If enacted, it would cost the city $261 million in lost revenues -- almost exactly what the homeowner rebates cost.

The council’s proposed expansion of the city’s earned-income-tax-credit – from 5 percent of the federal credit to 10 percent – is also targeted, in this case to working households earning less than $38,348. The total benefit would then range from $42 to $454 for eligible residents. Over 75 percent of the benefit would go to working households with incomes under $20,000. Combined with the $300 renter’s rebate, the council says, many working families would be raised above the poverty level, at a cost to the city of $62 million.

Council proposals for increased tax relief for seniors and the disabled would cost only $6 million in 2008, rising to $24 million in 2010. The council combines this with a proposal to eliminate the $12 million annual tax exemption for Madison Square Garden. This 25-year old political deal originally intended to keep the New York Knicks and Rangers from fleeing the city, has cost the city almost $300 million in inflation-adjusted tax revenues.

Money for Council Programs

On the expenditure side of the budget, the council has had some success in getting the mayor to include council priorities in the executive budget, including $12.9 million for district attorneys and support (for one year anyway) for 10 primary care clinics in high need communities.

The preliminary and executive budgets also “base-lined” some favorite council programs. These are programs that mayors traditionally fund for only one year at a time, resulting in a so-called budget dance as the mayor cuts the programs from the budget every year, and the council tries to bring back funding for them. Now these items will be included in the four-year plan, so they don’t need to be “restored” every year. Nevertheless, the council in its preliminary budget response noted that $266 million of council programs still are not base-lined and need to be restored in the negotiations this year – minimizing the council’s ability to fund new programs.

A Rainy Day Fund

The council’s comments on both the mayor’s preliminary and executive budgets include strong pleas for a rainy day fund, a city savings account for surplus funds from happy budget years like the current one. The money would then be available in tougher years to help stabilize city budgets.

Such an account would require approval by the state legislature and governor. Under current state law, the city cannot end the fiscal year with a surplus of more than $5 million and so cannot, the council has said, “carry forward funds from one fiscal year to the next.”

As a result, mayors spend down any surplus before the fiscal year ends. Generally, the city has pre-paid expenses, especially for debt service, that would otherwise be due the next year. This is called “rolling the surplus forward.” (In fact, Bloomberg has rolled part of the surplus into both the 2009 and 2010 budgets as well as 2008!)

Fiscal monitors say that, in effect, this technique works as a kind of rainy day fund. According to the council, “The problem with using the â€roll’ as a rainy day fund, however, is its lack of planning and transparency. The techniques used to move funds from one year to the next make it difficult for the council and the public to determine how much funding is available, how much was added in a given year, and how much would be subtracted, if applicable from it in the following year.”

The release of the executive budget pointed up this concern. In it, the mayor, faced with another $1 billion in unanticipated tax revenues, introduced a new way to spend down the expanding surplus, retiring $1.2 billion of debt (thus saving future debt retirement costs, mostly in 2009 and 2010). But the stated 2007 “surplus” of $4.4 billion doesn’t include that debt retirement, thus understating the resources available in 2007.

The confusion is apparent in reports by fiscal monitors. The state comptroller and the Independent Budget Office both say in their May reports on the executive budget that the 2007 surplus is $4.4 billion, but a third monitor, the city comptroller, includes the $1.2 billion debt retirement and says it’s $5.6 billion.

Of course, the issues here go beyond the numbers and the question of transparency to political concerns surrounding who makes the decisions on budget surpluses – the mayor, the council, or both. At the moment, the mayor seems to have total control. For instance, the May Independent Budget Office report notes that the mayor’s debt retirement “serves to take $1.2 billion â€off the table’ so it cannot be used for recurring expenditures or tax reductions that could be difficult to sustain.” So much for the council’s role.

A state-authorized rainy day fund, crafted by the mayor and council, would presumably give council a stronger role in decision-making about budgets than it has now. It would establish procedures – probably involving City Council in some way -- for determining how much money would be put aside and how that money could be used. Mayor Bloomberg, like his predecessors, would presumably prefer to keep things just as they are.

Glenn Pasanen, who teaches political science at Lehman College, has been in charge of Gotham Gazette's finance topic page since 2001.Â

Needed: Campaign Finance Reform

Governor Eliot Spitzer and members of the State Legislature came to Albany in January promising to change the way the state government does business. Now, with less than a month remaining before the scheduled end of the state legislative session, the Senate and the Assembly need to act on an issue that has the potential to change significantly the culture of Albany: reforming the state’s lax campaign finance laws.

New Yorkers have grown tired of the way in which special interests affect their state government and want to end the undue influence money has on campaigns, candidates and elected officials. Along with legislative gerrymandering (see related article), the flow of dollars to the re-election campaigns of elected officials enhances the power of incumbents, making it diifcult to challenge them and virtually impossible to unseat them.

In the past several years, reform proposals have passed in the Assembly but then died. Now, Governor Spitzer has proposed meaningful campaign finance reform that would take several necessary steps forward in limiting the influence of money in politics and thereby weaken the role of special interests.

The legislature must stop delaying action on this issue, because we have some of the weakest campaign finance laws in the country.

SKY HIGH LIMITS

How out of whack are our laws? Consider that campaign contributors can give 10 times as much to candidates running for governor of New York State than president of the United States. Candidates for federal office, including president, can't accept contributions larger than $2,300 per campaign or $4,600 per election, while in New York City, limits vary from $2,750 for City Council to $4,950 for mayor per election. But in New York State, contribution limits range from $7,600 for candidates for Assembly to $56,000 for governor.

Such high limits encourage candidates to go after contributors who can give the most rather than create a grassroots base of smaller donors. This lets a small but powerful group of campaign contributors hold significant sway over public policy decisions, arguably at the expense of the broader public interest. In fact, these special interests can stop just about any legislative action detrimental to their interests, adding to the gridlock that saddles our state government. If truth be told, many of contributors give not because they necessarily want to, but because they feel they must in order to protect their interests or advance their agendas.

GETTING AROUND THE LIMITS

To make matters worse, the current system allows unlimited "soft money" contributions. These "housekeeping" contributions are intended to support the organizational activities of the political parties and their various subsidiaries, but are often used surreptitiously to support the campaigns of candidates who need the party's help. Consequently, individuals and companies can give hundreds of thousands of dollars to party committees and flout the already high contribution limits of campaigns. "Soft money" contributions, along the money given to candidates, make up what has been tagged the "pay to play" culture where special interests feel an obligation to pony up to ensure access or favorable consideration of their issues.

Although corporations can contribute no more than $5,000 total in a calendar year, many get around that limit by forming various different and separate limited liability corporations that are subject to the same sky-high limits as individuals. Many of the corporations are established for the express purpose of getting around these minor restrictions and increasing the amount individuals and entities can contribute.

New York State also is exceedingly generous in how it lets politicians use their donations. Broad definitions of what are allowable campaign expenses encourage legislators to use their campaign accounts for personal reasons. The vagueness of state law permits them to use funds to pay for such items as swimming pool covers, vacation trips, rental cars, flowers, country club membership dues and so on.

WEAK ENFORCEMENT

New York State suffers from lax enforcement of its weak laws by a state Board of Elections, which is under funded and has limited authority. Tens of millions of dollars were spent in the last statewide election, but the state Board of Elections found only a handful of campaigns or committees guilty of violating state law and meted out less than $50,000 in fines. The board penalizes too few campaigns and fines them far too little for its actions to serve as a meaningful deterrent to violators.

TRACKING GIVING AND SPENDING

New York's disclosure laws do not require contributors to list their occupations or employers. They also don't require campaigns to report the names of those who helped solicit or deliver the contributions if there was a third party intermediary involved in the raising of the money, a practice known as bundling. Large campaign expenditures are also often not detailed, making it difficult to know what the expenses were for. And only expenses that have been paid for need to be reported, meaning a campaign may not report some expenses it incurred, but did not yet pay until after the election was over.

It is also very difficult to track the flow of campaign cash to incumbents during the legislative session. While there can be 10 or more campaign fundraisers every week from January through June, incumbents are not required to file even one campaign finance report during the legislative session. The first report due date comes in July, one month after the scheduled end of the session when all its business is done. This forecloses any real scrutiny of how contributions affected what happened or did not happen in Albany.

CHANGING THE SYSTEM

This dizzying array of sky-high contribution limits, multiple loopholes and loose enforcement have led good government groups like Citizens Union to call for major reform in the area of campaign finance. With the governor rightly connecting the dots among campaign contributions, undue influence and legislative gridlock, New York has reached a moment in time to change its laws, and hopefully before the legislative sessions ends in late June.

Whatever reform gets enacted needs to accomplish the following:

--Significantly lower the limits on campaign contributions from individuals and political action committees to candidates and party committees.

--Ban or restrict institutional contributions from limited liability corporations, partnerships, unions and corporations.

--Limit soft money contributions.

--Require greater disclosure of information about contributors and those who solicit and deliver the contributions.

--Require the filing of at least one campaign report during the legislative session.

--Restrict the "personal use" of campaign funds.

--Strengthen the power of the state Board of Elections to enforce these laws and increase the penalties and fines the board can assess.

In this fog of discussion about campaign finance and the race to enact real reform, it is difficult for voters to know where legislators stand on the specifics of the issue. This is why Citizens Union, Common Cause/NY, League of Women Voters and NYPIRG are pressing legislators to stand up and disclose their positions.

The legislature began its session in January by passing sorely needed and significant changes to our state’s ethics and lobbying laws. In doing so, the State Senate and Assembly signaled that fundamental change of state government was possible. It would be great and remarkable if they ended the session by changing New York’s notoriously weak campaign finance laws. Such action would help restore a small measure of citizens’ faith in our state government and send an important message to New Yorkers that the power of special interests in Albany can take a back seat in favor of the public interest.

Dick Dadey is executive director of Citizens Union and Citizens Union Foundation, which published Gotham Gazette.

Â

Breaks for Big Business

JP Morgan Chase, which boasts $1.4 trillion in assets, is a rich, powerful, and iconic New York City institution: the financial world’s equivalent of the New York Yankees.

And like the Yankees, who are building a new stadium with the help of more than $800 million in tax breaks and aid from the state and city, JP Morgan Chase also wants a new headquarters - and wants the public to help pay for it.

Representatives from JP Morgan Chase and the Bloomberg administration are currently meeting behind closed doors, trying to work out a deal for a 50-story, 1.3 million square foot skyscraper at the site of the old Deutsche Bank building near Ground Zero. The city is reportedly offering the bank about $100 million in tax breaks and subsidies. But Chase wants something closer to the $650 million deal that the city and state gave Goldman Sachs to build its headquarters in 2005.

And also like the Yankees –- who once threatened to leave the city if the team did not get a new stadium –- JP Morgan Chase has told city officials that if it does not get what it wants, it may move to Stamford, Connecticut.

"There's a viable alternative for them," Jim Fagan, of Cushman & Wakefield told the Stamford Advocate. "This should be a threat that New York should take seriously."

The current standoff between the city and JP Morgan Chase is just the latest example in a long running policy debate. Are tax breaks for big corporations a wise investment to keep jobs, businesses and tax revenue in the city? Or do they amount to corporate welfare?

WHO GETS HOW MUCH?

In the 1970s when the New York was in financial trouble, crime was high, and the future looked bleak, many Fortune 500 companies left the city. Since then, the government has looked for ways to use tax incentives to help create and keep businesses and jobs in New York, But over the last two decades, the practice – and the amounts given – have increased dramatically.

The main beneficiaries have been financial, insurance, media or real estate firms. But in the late 1990s the city gave aid to a number of dot com companies, according to a report by the Center for an Urban Future. Then as the dot com boom collapsed, the report said, many of the companies that “benefited from city retention deals … announced large-scale layoffs or merged with other media/Internet firms.” Manufacturing companies have also received incentives, mostly from the city Industrial Development Agency or from Industrial and Commercial Incentive Program, according to Jonathan Bowles, director of the nonprofit urban policy think tank Center for an Urban Future. Because manufacturing companies in the city tend to be smaller than the financial and media behemoths, these deals tend to involve less money – and receive less attention – than those affecting bigger corporations.

Precise numbers of the amount of subsidies are hard to come by. Since 1994, the state and city have announced more than $2 billion in subsidies to New York City companies in the name of "job retention," according Good Jobs New York, although they say the real costs are likely much higher since the details of many deals are not disclosed to the public.

Giuliani made subsidies an essential part of his economic policy, negotiating nearly 100 high-priced deals.

In these deals, the city and state usually promise to forego up to a certain amount in taxes, most often sales taxes, said Bowles. He estimates that since 1998 New York City corporations have received “upward of a billion dollars” in such commitments, although it is difficult to determine how much this actually cost the city and state in lot tax revenue.

GIULIANI DEALS

Whatever the exact figures, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani made such subsidies an essential part of his economic policy, negotiating nearly 100 high-priced deals, according to a database compiled by the watchdog group Good Jobs New York.

The incentives included:

- $52 million for NASDAQ

- $20 million for Met Life

- $29 million for Reed Elsevier

- And $75 million to Bear Sterns and Young.

The biggest retention deal of the Giuliani-era involved the New York Stock Exchange. The city and the state agreed to shell out as much as $1.1 billion over a number of years to keep the stock exchange from leaving the city. The deal eventually fell apart after the September 11, 2001, attacks as Mayor Michael Bloomberg said the city could not afford such a massive investment. However, by that time, the city had already spent about $80 million. The stock exchange, of course, has remained in lower Manhattan.

BLOOMBERG’S APPROACH

Bloomberg, who faced budget deficits in his first few years in office, promised to be more disciplined than Giuliani in granting subsidies to big corporations.

"We have basically ended the era of corporate welfare, basically paying people to stay," Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff said in 2003. Doctoroff’s boss – Bloomberg – said, "Any company that makes a decision as to where they are going to be based on the tax rate is a company that won't be around very long."

Despite this rhetoric, Bloomberg has agreed to large subsidies for new stadiums for the Yankees and Mets, and the Atlantic Yards project. He has also given tax credits to large corporations like Time Warner, Hearst, the New York Times, Bank of America, Pfizer, Aon and the Bank of New York.

The main difference between Giuliani’s and Bloomberg’s subsidies, Charles Bagli argued in a New York Times article, is the rationale.

“During the recession in the early 1990s, city officials argued that the incentives were necessary to persuade corporations not to abandon the city,” Bagli wrote. “Now, city officials argue that the city economy is so robust that companies cannot find large blocks of prime office space and cannot afford new construction without city subsidies.”

KEEPING COMPANIES DOWNTOWN

In 2005, Mayor Bloomberg signed off on one of the biggest corporate retention deals in the city history.

To lure Goldman Sachs, which had recently moved 3,000 employees to New Jersey, back to the city, the New York State’s Liberty Development Corporation issued $1.6 billion of federally funded Liberty Bonds to pay for most of a new $2 billion headquarters near Ground Zero. And Goldman Sachs received an estimated $650 million cash grants, tax-exempt bonds, sales and utility tax breaks and discounts on required payments in lieu of taxes.

“I think this may have been something the Bloomberg administration believed was an important chance to keep these jobs and tax revenue in the city, as well as create an anchor tenant for the World Trade Center site,” said Bowles. “They believed this would have a domino effect and attract additional developers and investors to the neighborhood, many of whom wouldn’t even consider commercial projects in the area for years after 9/11.”

The destruction of the Twin Towers and recent conversions of office buildings into residential buildings has reduced lower Manhattan from the third to the fourth largest central business district in the country, behind Midtown Manhattan, Chicago and Washington. And firms such as Brown Brothers Harriman, the Royal Bank of Scotland and UBS Warburg have recently relocated or in the process of relocating thousands of jobs and a substantial amount of tax revenue to Connecticut and New Jersey.

Despite that, other financial firms like JP Morgan Chase, Lehman Brothers, and Merrill Lynch have pushed for deals similar to the one given Goldman Sachs, but officials have not anted up in the same way.

Recently, Bloomberg said that he would not agree to such lucrative incentive packages for companies in lower Manhattan in the future. “If anyone builds downtown now, they will get normal, as-of-right tax breaks and nothing more,” the mayor said in April.

But given the increased competition from other cities and state, some argue that New York must be generous if it hopes to retain its title as “the world’s financial capital.”

“Having commercial activity like this is very important to the future of the World Trade Center site in terms of keeping it an active, public and welcoming location, as well as a magnet for other major businesses,” said Carl Weisbrod, a board member of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation and president of the city’s Economic Development Corporation from 1990 to 1994.

CHASING CHASE

In the case of JP Morgan Chase, Kathryn Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York City argues that historically, the various banks that today make up the bank (Chemical Bank, Manufacturers Hanover, JP Morgan and Chase Manhattan) were anchored in the financial district and played a key role in the development of Wall Street and New York City becoming the global center of the financial services industry.

“I think JPMorgan should receive subsidies from the city so the deal could go forward – it represents the best way to really complete the solidification of Lower Manhattan as the world financial capital,” argues Wylde.

But others counter that the Lower Manhattan has changed dramatically since September 11 and particularly in the past two years.

At the time of the Goldman Sachs deal, for example, 7 World Trade Center had no tenants, and some real-estate experts feared that lease-holder Larry Silverstein would not be able to secure any major corporations to occupy the building. But now, Bowles notes, 7 World Trade Center is completely pre-leased, and the high vacancy rate for office space in Lower Manhattan post 9/11 has dropped significantly.

“There’s currently a lot of positive momentum for that area right now and simply not the same kind of need for Bloomberg to use financial incentives to keep businesses there,” said Bowles.

DO THEY CREATE JOBS?

The primary argument for corporate subsidies is that they help the city keep and create jobs.

“Everyone agrees that one-off deals are, in the abstract, bad policy, but everyone also agrees that having a company forced to relocate thousands of jobs out of New York … is even worse public policy,” said Wylde.

But critics say that there is no guarantee that millions in tax breaks actually translates into increased employment.

The 2001 study by the Center for an Urban Future found that “a large percentage of the firms that have benefited from city retention deals during the past decade have been acquired by other companies, put themselves up for sale, gone belly-up, moved major parts of their business out of the city or simply eliminated many jobs in New York shortly after taking advantage of city incentives.”

In 2005, Bloomberg signed off on one of the biggest corporate retention deals in the city history.

In other words, the city actually lost jobs rather than gaining.

In 1997, for example, the city and the state awarded Merrill Lynch $28 million in tax breaks over 15 years in exchange for the firm staying in the city and hiring an additional 2,000 employees. But as of last year, Merrill Lynch had fewer employees than it did when the deal was made. Now with its lease at the World Financial Center and its tax breaks set to expire in 2012, the firm has been threatening to move its headquarters out of the city again.

Bettina Damiani of Good Jobs New York argues that if subsidies are going to be used, the deals should guarantee a certain number of jobs stay in the city. She also says that there needs to be an emphasis on training and placing city residents in any jobs that are created.

“We should use any money for subsidies as leverage for these employers to provide work opportunities to residents if we are using their tax dollars, and right now that simply isn’t happening,” said Damiani.

NYC VS. NYC

While some companies threaten to move out of New York City if they do not get subsidies, many get handouts for just moving to a different part of town.

In 2001, the city gave Metro Metropolitan Life $26 million in subsidies to move its 1,700 employees from Midtown to Long Island City, Queens, and stay there until 2021, rather than relocate them to Jersey City.

Five years later, the company had a change of heart and wanted to move back to Midtown Manhattan.

The city could have fined Met Life $24 million for breaking the agreement. Instead, it chose to fine the insurer $5 million and obtain another promise that the company would keep at least 1,800 employees in Queens.

JP Morgan Chase’s current headquarters is at 270 Park Avenue in Midtown, and if it builds its new headquarters downtown as many predict, the city will give incentives to move the company just a few miles south.

“This deal is simply pitting lower Manhattan against Midtown, and it is unclear as to what kind of net benefit this deal would have for the city as a whole by shifting employees from its Midtown office to a new office downtown,” said Damiani.

BROKEN PROMISES

The subsidies offer no guarantees that the firms that get them will keep employees and revenue in the city long-term. Rather, critics charge these arrangements only buy the city five to ten years of guarantees, after which the firms return to the mayor with their hands out, seeking a second round of subsidies.

And some companies receive generous subsidies meant to keep them in the city, even though they never even consider leaving.

“We realize it's not the cheapest place to do business, but we're already here,” Greg Vahle, a vice president of Pfizer told Crains NY Business in 2004, shortly after it received $46 million in subsides. “We attract a high-quality workforce in New York City, and we think it's advantageous to be in the country's business and financial capital.” Only up to a point apparently. Earlier this year, Pfizer announced it was closing its Brooklyn packaging plant, eliminating 600 jobs in the process.

Related Articles:

Industries That Got Away (2004)

The New York Stock Exchange And Wall Street's Future (2003)

NYC vs NJ (2002)

Â

Behind The Low Unemployment Rate

Mayor Michael Bloomberg and others are touting the city's low unemployment rate, which dropped to 4.3 percent in March, the latest data at this writing. When he released his Executive Budget on April 26, the mayor stated, “The unemployment rate is at historic lows in the city.” While it’s not clear if the March unemployment rate is indeed the “lowest level ever,” as the mayor’s budget press release claimed, it is the lowest in the Bureau of Labor Statistics series that began in January 1976.

In the 30-year span of recorded unemployment rates, the highest annual levels were 11.1 percent reached in 1976 and 1992. 2006 marked the first time that average rate for the year dropped below five percent (it was 4.9 percent).

For the past several decades, the unemployment rate has been one of the key indicators used to gauge the condition of the economy, particularly the state of the job market and whether it is favorable or unfavorable to workers and job seekers. But the number alone does not tell the entire story. Three main factors enter into the determination of the unemployment rate (see box), and several issues – including whether people are looking for work, racial and age differences and the length of time people remain unemployed – need to be considered to really make sense of what the unemployment rate is telling us.

The unemployment, considers simply whether or not a person has a job, not whether the job is a good one. (For more on changes in the city’s economy, including the job market, see related article.

UNEMPLOYMENT STORY IN A NUTSHELL

The quick takeaway on what today's relatively low New York City unemployment rate means is this:

|

• Overall the 30-plus-year low New York City unemployment rate is good news although unemployment is much higher and employment rates much lower among blacks and young people.

• While it represents a huge improvement over the 1990s, the unemployment rate is low today mainly because of the continued growth in low-wage jobs. The unemployment rate considers simply whether or not a person has a job, not whether the job is a good one. (For more on changes in the city’s economy, including the job market, see related article.

• While unemployment may be less common than at other times in the past few decades, it still exacts a heavy toll since fewer unemployed workers receive unemployment insurance benefits than 20 or 30 years ago and many of the unemployed, particularly men, blacks and workers 45 and older, experience long spells without work.