Neighborhood Banking Is About To Change

Imagine this: You walk to the corner store with your paycheck loaded on an electric card and slip it into an ATM-like machine. You take out a short term, high interest loan, download $60 into a savings account, transfer 40 bucks to your checking account, pay your electric bill, send fifty dollars to your sister who lives overseas -- and, oh yes, purchase that George Forman grill you’ve been eyeing. Finally, the machine spits out $31.35, coins and all, in cash that you requested. You do all this with one swipe of the card.

What is so tellingly futuristic about this scene is not the technology – we’re pretty much already there. It’s the virtual walls you just crashed through which, for now at least, separate various forms of financial and commercial transactions.

No walls have arguably been more impenetrable than those between banks and check cashing stores, more politely known as financial service centers. Like the kind of neighborhoods they are associated with, check cashers have operated for years on the other side of the tracks from bank branches, kept apart by regulatory boundaries and divergent business cultures.

But lately, driven by new technologies and a growing appreciation for the enormous, untapped profit and market opportunities in low-income neighborhoods, maverick providers of traditional banking services and check cashers have been taking pages from each other's playbooks and, in some cases, even collaborating. This experimentation will not only shape the course of neighborhood banking in New York and nationwide, but also redefine who and what is considered part of the banking mainstream.

Different Worlds

Commercial banks, thrifts and even most credit unions have long looked down their noses on check cashing operations, and, by extension, the predominately low-income people who use them, concluding there was either too little profit to be gained, or too much respectability to lose, in this gritty business.

On the other hand, check cashing operations, which offer products and services like money orders, pre-paid debit cards, utility payments and remittances, dominate certain inner city turfs by deliberately shunning the alleged white collar elitism of the banking industry. The 660 check cashing centers in New York specialize in serving customers in search of a simple financial transaction, rather than the institutional relationship sought by retail bankers.

Despite their different worlds, a few banks, such as Chase and Banco Popular, have over the years attempted modest, fairly low-impact, forays into check cashing or have, on occasion, purchased check cashing operations. Yet none have brought non-traditional financial services into the core of their business or have used these so-called “fringe” services to link customers to banking products.

Outside New York, however, some banks have been testing check cashing services in their branch lobbies alongside traditional teller lines and are creating new financial service prototypes.

Pioneering In The Bronx

Taking careful note of developments in areas such as California and Ohio, the Checkspring Community Corporation, headquartered in the Bronx, currently has a bank charter application pending in New York State. If its charter is approved, Checkspring will be poised to introduce a more fully integrated bank/check casher business model, the likes of which the New York City market has never seen.

Some of this territory has already been traveled through a collaboration between RiteCheck, a prominent check cashing chain, and Bethex Federal Credit Union, both of which serve low-income populations in the Bronx. In 2001 they piloted a program in which members of Bethex accessed their accounts through RiteCheck storefronts and cashed their checks at RiteCheck for free or at a reduced fee (In PDF Format) . The program worked so well that RiteCheck is expanding it to include partnerships with several new credit unions.

As options for electronically transmitting cash increase, and use of the traditional check diminishes, check cashers are trying to find new ways to engage customers and add value to their lives. In May of this year the Financial Services Centers of America (FiSCA), the trade association for check cashing operations, announced the roll-out of a “revolutionary”, “All Access” Savings Program, which promises to provide “underserved Americans greater access to mainstream financial services” by giving check cashing customers the ability to make electronic deposits in federally insured, interest bearing, savings accounts.

7-Eleven and Wal-Mart In On The New Trend

While a few industry watchers I talked to in New York see these developments as more or less isolated events, Jennifer Tescher, the Director of the Chicago-based Center for Financial Services Innovation, views them as part of a certifiable industry trend and realignment. She insists that “the entire financial services industry is dramatically changing in ways that weren’t even possible five years ago”.

Tescher points to the rise of the non-bank sector in financial services as an indicator of how segmentations within the financial services universe are dissolving. In 2003 the nation’s largest convenience store chain, 7-Eleven, using their own “virtual commerce” technology, placed kiosks in a thousand of its convenience stores machinesthat enabled customers to conduct ATM transactions, cash checks to the penny, purchase money orders, send wire transfers and pay bills.

A year later Wal-Mart raised the bar. Wal-Mart offers check cashing, money orders and wire transfers while also providing banking services in “Wal-Mart Money Centers”. Some analysts believe Wal-Mart, which targets low-income customers and is the world’s biggest retailer, is trying to create a physical and psychological, environment for the customer in which banking, alternative financial services and shopping are collapsed into a single retail experience.

A Gold Rush In Low-Income Financial Services

The sudden “discovery” of the low-income financial services niche by retailers and mainstream bankers is propelled by the explosion in the alternative financial services industry. The lure of this market comes at a time when banks are finding intensified competition in middle class, suburban markets. Meanwhile, branch presence in low income areas has been steadily declining over the last thirty years. One quarter of Black and Latino families, as well as 25 percent of all American families making less than $20,000 per year, don’t have bank accounts.

The very idea of a “fringe” economy is somewhat misleading. About a quarter of the nation’s gross domestic product reflects unreported income and a study conducted by Social Compact, which promotes business investment in inner city communities, estimates that Harlem, a poster child for fringe financial services, has a $1 billion cash economy. And as low income families look for ways to move cash around, check cashers are there to serve them. The alternative financial services industry is racking up an estimated $200 billion in transactions annually.

Of course alternative financial services are widely viewed as exploitative of poor people, particularly in states where there is a lack of regulatory restraint. Customers have very little opportunity to save and build assets using alternative financial services, and whereas banks have some semblance of a mandate to give back to communities where they do business because of the Community Reinvestment Act, check cashing operations have no such obligation.

But in the end, financial service centers are so compelling to their customers because they provide convenience and a wide range of options, with few questions asked: Money orders function as checking accounts. Where banks place holds on checks, check cashing offers immediate liquidity. Pre-paid debit cards, otherwise known as stored value cards, can facilitate everything from long distance phone calling and credit card purchases, to bill paying and, now, even limited-service savings accounts. The fact that check cashers charge, some say, unreasonable fees, is in a way no different that what low-income people expect from a bank or any other kind of capitalist institution doing business in the â€hood.

The Filene Research Institute, which studies issues affecting the future of credit unions, believes so much in the future of alternative financial services that it has created a program that counsels credit unions on how to offer check cashing products. Citing what they see as the declining relevance of credit unions, thrifts and banks in certain areas, Filene issues a stern warning to depositories of all stripes: Begin adopting the ways of the check casher or perish.

Some banks have clearly seen the writing on the wall.

Union Bank of California (UBC) owns and operates over 50 hybrid financial service outlets, in which check cashing services are offered in banks and stores, and banking services are offered in check cashing locations.

KeyBank, just one of many enthusiastic UBC disciples across the country, has created “KeyBank Plus”, a separate product (and teller) line designed especially for low-income customers without bank accounts. Officials from KeyBank maintain that, once a customer enters a Plus branch, Key creates conditions that will prompt that customer to establish a long term - and higher profit margin – relationship.

“The banking industry has done an amazing job of sending messages of exclusion through its product design and minimum balances.” says Edna Sawady, chief operating officer for community development at KeyBank. “At banks many customers fear that they won’t qualify for something…In check cashing lines you don’t run the risk of being rejected”.

Rising Challenges and Criticisms

Regulatory agencies will be challenged to catch up to, much less stay ahead of, these changes because the fundamental elements that help us make distinctions between financial services industries -- the deposit, the check, the branch, credit -- are themselves moving, morphing targets.

Pre-paid debit cards, for example, are exploding in popularity and operate in a virtually unregulated environment. As pre-paid debit cards are used to perform traditional banking functions, like checking, what classifications and regulatory jurisdictions will be applied to monitor and standardize their use?

Financial service entrepreneur Joe Coleman of RiteCheck, a co-engineer of the RiteCheck/Bethex collaboration, is leery of banks encroaching on his territory. He thinks RiteCheck and credit unions like Bethex, whose products are designed for low-income people, have a future together because “we have the same customers”

New York poses its own particular restrictions for check cashers. One notorious service that is popular throughout the country, pay day lending, a type of short term, very high interest loan, is illegal in New York. More importantly New York requires that licensed financial service centers cannot operate within 3/10 of a mile from one another and cannot charge a check cashing fee exceeding 1.5 percent of the check’s face value.

But ultimately, it is the low profit margin on fringe financial services (Coleman calls it “1 million people with a dollar”) that is most daunting to institutions who don’t measure success by the number of live bodies in their lobby. Even Joy Cousminer, president of Bethex and Joe Coleman’s collaborator, acknowledges this tension. “Check cashers lose less money on a bad check than on a slow line. With us, it’s exactly the opposite.”

Cousminer also doubts that banks are actually interested in building relationships with poor people and believes banks are in fact keeping their check cashing and banking customers distinct and separate.

Whether banks using integrated bank-check cashing services are making money on the check cashing side, or through the “migration” of customers to the bank side, or both, is unclear. At least one of the bank representatives I spoke to refused to disclose that information. What is clear is if Checkspring, or any other New York bank, faithfully follows the UBC and KeyBank strategy, and doesn’t mind masses of poor people in its lobby, it stands a fighting chance of turning a profit after a few years. UBC has been at it for thirteen years and Keybank is preparing to expand its program dramatically. Once one bank pulls it off in New York, others might follow.

Not everyone thinks this a good thing. Sarah Ludwig, executive director of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Projectfears that banks will, in trying to turn a profit, give shorter shrift to the goal of building a bridge between the underserved and asset-building opportunities. “We’ve got this massive problem of low-income people needing essential financial services,” says Ludwig, “but now banks are starting to provide services that not comparable to the services that are provided” in middle class areas.

For Ludwig, and many other advocates who are highly critical of the check cashing industry, alternative financial services are a symptom of the problem, not a solution. “The fringe products that banks offer will look cleaner and meet regulatory standards, but the bottom line is they are still inferior products…There is an unequal, two-tiered financial services industry…We shouldn’t try to serve the low-income market in a way that perpetuates this segmentation.”

Coleman shrugs off this criticism. “In banks there is a middle class prejudice. They want to sign you up. They think everybody wants to be like them...I know we are helping people. We are helping them build their lives.”

Mark Winston Griffith, a founder of the non-profit Central Brooklyn Partnership and a fellow at the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy, has been in charge of the community development topic page since its inception in 2003.Â

Restoration on Eldridge Street

|

Forty years ago, New York reacted to the loss of old Pennsylvania Station by passing a law to protect city landmarks. In this series, in partnership with Open House New York, New Yorkers with a stake in the physical city will argue the consequences of the law, the merits and drawbacks of the preservation movement, and what the future might bring. |

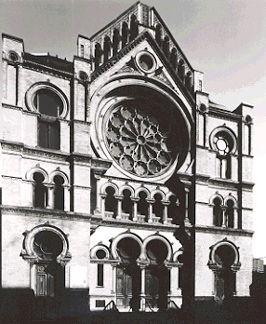

When Gerard Wolfe, then a professor at New York University, first entered the main sanctuary of the Eldridge Street synagogue in the mid 1970s, he found a time capsule. The 19th century Lower East Side building still served as a synagogue but, over the years, as the size of the congregation dwindled, the worshippers had moved downstairs and shuttered the doors to the main area.

Wolfe, who was writing a book about the synagogues of the Lower East Side, discovered a space both spectral and spectacular. Cobwebs extended between the building’s hand-painted pillars. Old prayer books were scattered among the pews. Decades-old prayer shawls remained hidden in special compartments of the benches intended for the tallisim. Newspapers, from the 1940s, opened to the sports pages, lay on seats, a clear reminder of the people who attended services and would perhaps sneak a look during the rabbi’s sermon.

And yet the grandeur of the sanctuary remained intact. The sanctuary’s exquisite (if deteriorated) stained-glass windows, hand-painted murals, and Victorian fixtures signaling the importance of the structure for its Jewish immigrant founders.

And yet the grandeur of the sanctuary remained intact. The sanctuary’s exquisite (if deteriorated) stained-glass windows, hand-painted murals, and Victorian fixtures signaling the importance of the structure for its Jewish immigrant founders.

Wolfe’s discovery marked the beginning of a restoration project, still going on 30 years later, that serves as a model for other historical houses of worship in New York City and throughout the country.

SYNAGOGUE AND STATE

Under the leadership of leading preservationists and community activists, including Roberta Brandes Gratz, an urban critic and journalist, the Eldridge Street Project was founded. This group wanted to save the building. They also wanted to open this historic treasure to the public in the immediate community and beyond.

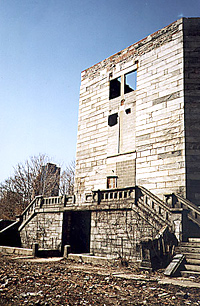

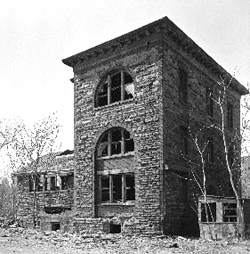

They faced daunting challenges. Unlike many other historic sites around the city, the synagogue was not about to be torn down and had not been vandalized. But it was in danger of falling down. The roof leaked, threatening the interior. The cellar had filled in, and a stair tower collapsed.

The city of New York does not give money to houses of worship for fear of violating the constitutional restrictions on state aid to religious institutions. Some foundations are also reluctant to aid religious groups. And so, it was very important to establish an educational and cultural center serving a diverse constituency. Today, the congregation -- officially called Congregation K’hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz -- owns the building. The congregation is several dozen strong, a stalwart group committed to the continued spiritual life of the building.

The city of New York does not give money to houses of worship for fear of violating the constitutional restrictions on state aid to religious institutions. Some foundations are also reluctant to aid religious groups. And so, it was very important to establish an educational and cultural center serving a diverse constituency. Today, the congregation -- officially called Congregation K’hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz -- owns the building. The congregation is several dozen strong, a stalwart group committed to the continued spiritual life of the building.

The restoration is the responsibility of the Eldridge Street Project, the non-profit non-sectarian group formed in 1986. Under a memorandum of understanding, the congregation controls all the religious aspects of the synagogue, while the project oversees the restoration – included related fundraising – and the cultural life of the building. The project runs educational and cultural programs, as well as tours, for some 20,000 visitors a year.

Whenever a church or synagogue asks us for advice about how to restore their site, we tell them the first step is to create a separate 501-C3 (tax exempt) organization to make a clear distinction between the religious life of the building and the historical or educational functions. While few, if any, groups are identical to us, some are similar. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is one. In some parts of the country, particularly the South, where the Jewish community is fast disappearing, not-for-profit organizations have taken over synagogues and restored them as museums or for other projects. In these cases, though, there is no congregation anymore.

In recognition of our public service, the city provided first program support and more recently capital support for the restoration of our landmark building. There was little resistance to public money coming to us. Norman Siegel, then executive director of New York Civil Liberties Union, called the funding “constitutionally suspect,” but that was about it. The city funds served as a rallying point for us to get other support.

The city was largely responsible for the most recent phase in our restoration -- the creation of a new cellar. Much of the area was filled with dirt, so workers had to excavate it while, at the same time, supporting the building -- an engineering feat. The city money, matched by private donations, was particularly welcome because private donors often do not want to pay for plumbing or mechanical systems. Now we can turn our attention to the most beautiful aesthetic parts of the restoration.

Another interesting example of the sensitivity of a sacred site receiving public funds arose in connection with funds received from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Commission rules bar it from supporting a capital project that includes religious iconography. Several years ago, we approached them for funding for our roof project. This turned out to be tricky as the finials mounting the roof feature elegant Stars of David. Eventually, we found a clear stretch of work without the stars and received a $25,000 grant from the commission.

Another interesting example of the sensitivity of a sacred site receiving public funds arose in connection with funds received from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Commission rules bar it from supporting a capital project that includes religious iconography. Several years ago, we approached them for funding for our roof project. This turned out to be tricky as the finials mounting the roof feature elegant Stars of David. Eventually, we found a clear stretch of work without the stars and received a $25,000 grant from the commission.

Being designated a city and national landmark has also propelled us forward The city landmark recognizes the architecture, while the National Historic Landmark designation is both about the architecture and the building’s significance as being representative of immigrant religious structures. Receiving national designation is a real challenge, as you must explain in detail why your site is either the only one of its kind or a platonic ideal of a phenomenon. Much of our fundraising has been through national direct-mail appeals – many to people who have a tie to the neighborhood or see this site as a kind of portal to their ancestors’ Jewish experience. To these people, designation as a National Historic Landmark has been very meaningful. It serves as a kind of vetting.

A LOWER EAST SIDE STORY

Certainly, this building has been enormously significant both in this neighborhood and to the East European Jewish experience in America. In 1886, when construction began on the building, most synagogues on the Lower East Side were shtetla, small storefront synagogues for people from a single city. But Eldridge Street was unique -- a cosmopolitan congregation of people from all over Eastern Europe.

It was the first grand structure in the neighborhood, taking 10 months and about $100,000 to build. The members constructed a building that dominated the block. This was the first time they could worship openly as Jews so they put Stars of David on the façade. And because many of them worked in factories and lived in dark tenements, they placed windows on every side of the building to beautifully illuminate their synagogue.

Some of the Eldridge Street synagogue founders had been in America for a while already. They had arrived in the 1850s -- before the major wave of East European Jewish immigration in the 1880s and 1890s – and had established themselves.

As many as 1,000 families belonged. They ranged from very wealthy members to people who could not afford the dues. We know from minute books that some people paid $2 for their seat, and some paid $200. It is and was an Orthodox house of worship so the men and the women sit separately.

As many as 1,000 families belonged. They ranged from very wealthy members to people who could not afford the dues. We know from minute books that some people paid $2 for their seat, and some paid $200. It is and was an Orthodox house of worship so the men and the women sit separately.

Until the 1920s, this was a very vibrant congregation. Then, the immigration laws changed, so the immigrants stopped arriving. At the same time, everyone who lived on the Lower East Side wanted to get out. The Jews left for the Bronx, Brooklyn and even the Upper East Side. With no new Jewish immigrants arriving to replace them, this and other congregations got smaller and smaller.

Some of our visitors are disappointed the area is not still Jewish. But this is a story of immigrant success. The East European Jews wanted to leave the neighborhood, and they were able to.

REDISCOVERING THE SYNAGOGUE

Despite the changes, a congregation always remained at Eldridge Street. But it could not maintain the building’s grand main sanctuary and so, at some point, probably in the 1950s, the members closed the doors and stopped coming upstairs to the main synagogue.

Today, the building boasts a new slate roof. The cellar has been dug out. Air conditioning and ventilation systems have been installed, while the crumbling stair tower, now rebuilt, will house an elevator. But the synagogue’s striking architectural details, including rose windows, 70-foot ceilings and a velvet-lined ark, remain. So far, the project has raised about $8 million of the estimated $12 million need for the renovation. At time progress has been slow-going, but the restoration is currently moving ahead, and we anticipate completion by early 2007.

And the building is once again open. Children, adults, and families come to learn about Jewish history, the immigration experience and architecture and historic preservation. They represent all cultural backgrounds (For a schedule of tours, click here)

BOTH EGG ROLLS AND EGG CREAMS

Many people visit because of nostalgia or because the Lower East Side was the gateway place for their families. Others come to see the space and learn about the American immigrant experience, particularly the East European Jewish experience.

Many people visit because of nostalgia or because the Lower East Side was the gateway place for their families. Others come to see the space and learn about the American immigrant experience, particularly the East European Jewish experience.

Amid all the educational programs the Eldridge Street Project offers – some focusing on architecture, others on the East European Jews in the United States – we also work to reach out to the synagogue’s neighbors, many of whom are first generation Chinese immigrants. The Eldridge Street Project’s relationship with these residents testifies to the continuing immigrant experience in New York.

A few weeks ago, our annual egg roll and egg cream festival showcased the two communities – Chinese and East European Jewish -- that have lived or live today on this block. More than 1,500 people joined us for klezmer music, Chinese opera, and Jewish and Chinese folk music performances; Hebrew and Chinese scribal art, Yiddish and Chinese games, and, of course, kosher egg creams and egg rolls.

Last year, we presented a video installation featuring a 12-minute film projected at night through the synagogue windows. It included a 12-minute history of the synagogue and its neighborhood and images that explained what is happening today.

Eldridge Street encapsulates a piece of our history that is important to preserve. It is an architectural landmark, a place of historic importance in the city, a beautiful place. But, as the festival and the video project have demonstrated, what is even more amazing about the building is the new life it has taken on as a place where people can come together and learn about the past.

Amy Milford is director of public and community relations for the Eldridge Street Project.Â

NASCAR, The Largest Proposed NYC Sports Stadium Of All

Despite all the press about proposed new sports stadiums, many New Yorkers know surprisingly little about the largest one. Which one would have the biggest field, the most spectator seats, feature the biggest new retail mall, and sit on the largest redevelopment site?

Not the West Side Stadium, even if it hadn’t gone down to defeat through a mix of community organizing, Cablevision cash, and political pique. Not the Nets Arena at Forest City Ratner’s proposed Brooklyn Atlantic Yards (which received something of coronation recently from The New York Times, as if to reassure the public that this is still a developer’s town), even though the project’s 21 acres could wind up having as many as 6,000 units of housing and 200,000 square feet of retail space. Not the new Yankee Stadium, with its new lucrative luxury sky boxes, to be built on the site of Macombs Dam Park in the South Bronx.

The largest sports facility proposed for NYC right now is a NASCAR track on Staten Island. The track would seat 80,000 fans, watching cars race around a track three-quarters of a mile long, near a new 620,000 square foot big-box retail mall on a 675-acre site. The site, the former BATX oil tank farm located off the West Shore Expressway, south of the Goethals Bridge in Bloomfield, S.I., is the largest vacant industrial property in New York City (and the site of a gas tank explosion in 1973 that killed 40 workers).

Who Among Us Does Not Love NASCAR?

Blue-state, subway-riding New Yorkers -- who don’t feel the pressure that John Kerry did to be loved by American stock-car racing fans -- might be forgiven for knowing little about the fastest growing sport in the United States. NASCAR – the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing -- was founded in 1948 by Bill France, Sr. Several years later, he founded the International Speedway Corporation, which owns the racetracks. Stock car racing remained a largely Southern sport, with a limited audience, until the 1970s, when the R.J. Reynolds tobacco company became a lead sponsor, and the Daytona 500 became the first nationally televised stock car race. Still a family-owned business, NASCAR has annual revenues in the billions and is regularly cited as the fastest growing spectator sport in the United States.

The International Speedway Corporation, also owned by the France family, owns 12 of the NASCAR racetracks around the country (they recently opened tracks near Kansas City and Chicago). The ISC has been actively looking to expand into the northeast for a while. After deciding that an available site in the Meadowlands was too small, they set their sites on Staten Island. In December, the ISC and the Related Corporation (one of NYC’s largest real estate developers, whose recent projects include the AOL Time Warner Center and the Gateway Center mall in East New York) teamed up to buy the property for $110 million.

Traffic, Environmental, and Fiscal Lessons from the Gas Guzzlers

Since purchasing the site, the International Speedway Corporation has been hard at work to pre-empt local concerns about environmental issues and especially traffic. They have put forward an innovative traffic plan for the three races that would take place each year. There will be only 8,400 parking spaces for the 80,000 fans, and Staten Islanders will have priority for these. Everyone else will have to come by ferry (NASCAR says they’ll rent just about every available ferry in the region on race weekends), bus (from parking lots in New Jersey and elsewhere), and perhaps even a new light rail line. And fans shouldn’t count on driving anyway and parking on local streets. Every ticket will be tied to a means of transportation, and you won’t be allowed into the race any other way. NASCAR also promises to pay to widen the Goethals Bridge toll plaza and add new ramps to their site from the West Side Expressway.

In addition, the International Speedway Corporation says they will preserve 245 acres of the site as wetlands (the site features heron and ibises). The new ferry docks on the site could be used by commuters during the work week. Local schools and not-for-profits will be able to use the track on the 300+ days per year when there is not race activity, and they are allowed to solicit in the stands on race weekends.

When lined up against NYC’s other mega-projects, Aaron Naparstek has written, “the Nascar track is in many ways the most innovative, thoughtful and urban-friendly … So, what does it say about the state of New York City urban planning and development that the toothless, beer-bellied rubes of Nascar are doing a better job of caring for our city than we are?”

One other feature distinguishes the NASCAR proposal from the Jets and the Nets: The International Speedway Corporation is seeking no public subsidies for their $550 million track, and it is likely they would even pay some real estate taxes – although it is still possible that the Related Companies will seek subsidies or city money for infrastructure for the mall.

Local Opposition Growing

Despite these innovative features, local sentiment has not been favorable. Last week, 40 Staten Island activists, including ministers and the leaders of civic organizations, gathered to form a united group to oppose NASCAR. They are hoping to form a broader umbrella group of civic organizations opposed to the project.

As a result of growing civic pressure, several elected officials have become more critical of the project. Republican South Shore Councilmember Andrew Lanza was quoted in the New York Times in May, 2004 as saying, “It’s an intriguing idea that we would like to explore further. At first you are concerned about the additional traffic and noise, but then you take a closer look at it, and you are only talking about a couple of events a year and you have a great facility that can be put to other uses.” By this March, however, Lanza said he was gearing up to intensify his opposition to the track. Democratic North Shore Councilmember Michael McMahon mused in December that with community benefits like a new high school and an indoor track & field complex, the project might be made to work for the community. But more recently he has been critical of NASCAR’s traffic assessment. And Republican Mid Island Councilmember James Oddo, who represents the area, has consistently expressed skepticism. Their opinions will matter -- since (also unlike the Jets and Nets) the project is not sponsored by the Empire State Development Corporation and will therefore have to go through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) which includes a vote by the City Council.

Residents and elected officials are concerned that while the track will start with 8,400 parking spaces, the ISC will find it unworkable and try to expand to more. NASCAR fans often come for the entire weekend (a good many in Winnebagos – current plans call for 635 RV parking spaces on site), so how will they get around while they are here? Others are concerned that even if race weekend traffic is managed, the proposed retail mall would cause more consistent problems on the West Shore and Staten Island Expressways, and on the Goethals Bridge.

In addition, because there are only three races per year, the track could be of limited benefit to the local economy. There will be construction jobs, and it will surely be good for Lois and Richard Nicotra, who have recently built a surprisingly successful hotel complex nearby. However, because the traffic plan will prevent people from driving, it is unlikely there will be much spillover to many area businesses. The big box retail stores are likely to be national chains, which won’t help local businesses, and which generally create lower-wage jobs.

But NASCAR suggests that other uses for the site could be even less desirable. The site is contaminated, and will require more than four million cubic feet of silt to raise the ground to a level that won’t be underwater in heavy rains. As a result, it is unclear if it would be appropriate for residential use. Staten Island residents have recently protested against what they see as overdevelopment, so many might frown on new housing there anyway. Some have called for a movie studio, but with the new Steiner Studios in Brooklyn already competing with Silvercup and Kaufman in Queens while the film industry is increasingly leaving the U.S. altogether, it is hard to see how a studio here would compete.

Whether Staten Island and New York City will be willing to go for the ''noise and speed and glory and death'' that is NASCAR (32 drivers have died in crashes) – as described in Jeff MacGregor’s new book, Sunday Money: Speed! Lust! Madness! Death! A Hot Lap Around America with Nascar – remains to be seen. One thing is certain, though. If the track is built, New York politicians running for national office will have less distance to travel to show their solidarity with American race car fans … so long as they don’t forget their ferry ticket.

Brad Lander is the director of the Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development Â

The Mayoral Candidates On Housing

The following is an edited transcript of a forum on housing issues with five mayoral candidates, conducted on April 4th by three of the major housing advocacy organizations in the city: Tenants and Neighbors, Met Council on Housing and Coalition for the Homeless. Michael Bloomberg declined an invitation to attend.

Almost 700 people listened to the candidates answer eight questions on housing issues ranging from the unfulfilled promise to use Battery Park Authority funds to build affordable housing to an expansion of the Senior Citizens Rent Increase Exemption, which pays rent increases for income-eligible senior citizens.

Since some of the candidates arrived after the beginning, the transcript below has been somewhat rearranged to make it easier to read:

- OPENING STATEMENTS

- BATTERY PARK MONEY FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING

- REPEALING THE URSTADT LAW

- EMERGENCY SHELTER

- RENT GUIDELINES BOARD AND ONE-YEAR RENT FREEZE

- SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

- INCLUSIONARY ZONING

- PRESERVING GOVERNMENT-SUBSIDIZED AFFORDABLE HOUSING

- EXPANDING RENT INCREASE EXEMPTIONS TO THE DISABLED

OPENING STATEMENTS

Fernando Ferrer: There is a crisis of affordability in New York. New Yorkers are getting priced out of their own town. You may remember I said this four years ago. It hasn’t gotten any better in the last four years. One of the reasons why is because we have a mayor who thinks it’s more important to subsidize major league football stadiums on the West Side than to get serious about affordable housing, than to get serious about schools, than to get serious about good jobs with health care. Well, I think it’s time to get serious about those things.

Over the course of my public life, there isn’t a whole lot of doubt about where I’ve stood on the issue of affordable housing, presiding over the biggest revival of affordable housing in the Bronx at any one time anywhere in America. But now, in private life I’m still chairman of a not-for-profit housing group in the South Bronx that was rescued from decline.

We see first hand the failure of this administration in fighting for enough Section 8 vouchers, the failure of this administration in keeping costs low, like water, like real estate taxes, that reflect themselves in everybody’s monthly rent. This administration has been a failure in affordable housing preferring to spend a whole lot more time on where the javelin throw event will be staged than how many people can live affordably in their own town. That’s why I’m running for mayor.

Steve Shaw: I think that most candidates in this election all want the same thing. We want to have strong neighborhoods, we want to have people live in those neighborhoods without spending an arm and a leg for it. But the question is is how do you achieve it?

I believe you achieve it in a much different manner than which Mr. Ferrer and which the Democrats and Mr. Bloomberg believe you do it. I believe that the way that you achieve affordable housing is through home ownership. That’s the way you do it. That’s the way that the majority of Americans build wealth. That’s the way that you make your housing cost consistent for the rest of your life.

I know I’m not going to be popular for saying this, but if you look at the impact that rent regulation has on homeownership it kills it. If you look at the cities that have high rent regulation, cities like New York, Santa Monica, homeownership is 30 percent. Look at other cities, such as Philadelphia, Seattle, homeownership in those cities – no rent control, no rent regulation – homeownership of 50 to 60 percent.

We have to address rent regulation. We have to cut taxes so we put money back in the hands and people’s pockets so that they can make decisions for themselves. So they can save for a down payment on a home. And lastly we need to create jobs. Because the only way that people are going to afford housing is if they have jobs in order to pay for it. Under Mayor Bloomberg job creation has been nothing; over the last two and a half years, the city has lost about 30,000 private sector jobs. We need pro-growth policies, we need to create jobs. That’s the way you create affordable housing and make this city better.

C. Virginia Fields The number one issue that is facing all New Yorkers is the need for affordable housing... As I look at my time in elected office, someone recently reminded me that one of the reasons I first ran for office in 1989 as a member to the City Council was because of housing -- to turn housing conditions around in the district that I represented, primarily central Harlem and East Harlem, to make sure that we were able to keep housing available for people who had lived there during the years when the community was not where it is now as well as to continue to build and grow a community so that others who were moving to New York right out of college, wanted to have a good start, could also stay there. I am pleased to say that housing was my top priority then, housing has continued to be my top priority, and it continues to be that today.

I will as mayor use the office to develop a real comprehensive plan to create affordable housing. And one way we do that is number one by investing in it, putting dollars in it. When we look in the past in terms of how we have been able to create affordable housing, it is when we had a plan, we had dollars in it, and we leveraged those dollars and we were able to see results so that it is one place we start. I’m passionate about affordable housing. So, I will continue my work that I have started as a community board member, a City Council member, a borough president and as your mayor, to make that a number one priority.

Gifford Miller I’m here to ask you for your support for my candidacy for mayor...Everywhere I go I talk to people who are hanging on by their fingernails either trying to find housing that they can afford or hold on desperately to the housing that they have.

Unfortunately we have a mayor who is making the wrong choices for this city. He’s making the wrong choices for us. Choosing to spend more than a billion and a half dollars worth of taxpayer subsidy – because that’s what it is when you add it all up – in a football stadium? Instead of building the housing and the schools that we need here in this city. And you know, amazingly, he has said – it isn’t just that we want to say no to a stadium, we want to say yes to housing – and this mayor has said if we build housing on that site there will be too much housing in Manhattan. No honestly he said it. I don’t know how much more graphically he can show he’s out of touch with the needs.

He’s also made the wrong choice though on protecting tenants rights, vetoing the strong lead paint legislation that I worked with all of you to enact, to protect children in this city from lead paint poisoning. He’s made the wrong choices.

Now what are the right choices? It’s not enough to say he’s made the wrong choices. What are the right choices? First of all we have to protect tenants. And that’s what that lead paint legislation and other things I’ve done as Speaker have tried to lead the way on. Secondly we have to preserve our housing. And that means repealing the Urstadt Law and protecting Mitchell-Lama units and keeping them in the system and not letting them leave. Third we have to put more resources toward affordable housing. And as Speaker of the Council, I’ve put tens of millions of dollars into the budget to build more affordable units and to make what units we’re creating more affordable. And finally we have to use innovative techniques, like inclusionary zoning, things that won’t require money. And I’m proud of the fact that we’ve just passed the Clinton-Hell’s Kitchen rezoning and created 3,400 units of permanent affordable housing. Those are the right choices. That’s the kind of city that we can be. I look forward to doing it with all of you.

Anthony Weiner: I have a fundamentally different view of the city than the mayor does. Maybe it comes from the fact that I went to public schools, I grew up in Brooklyn, I live in Queens. It’s been awhile since we had a mayor from Brooklyn, huh? You know, I fundamentally believe that when Mayor Bloomberg says, “Ah, it doesn’t really matter that I’m a Republican and I give money to Republicans and endorse Republicans and give a fancy party for Republicans and stand up at a convention for Republicans and say that we should vote for the Republican George Bush,” that’s not what makes him a Republican. What makes him a Republican is fundamentally he has a level of contempt for rooms like this. He has this notion that it is not necessary to talk to other officials of government, it’s not necessary to talk to advocates about how to solve problems, it’s not necessary even to have a vote on something like the allocation of nearly $2 billion of city subsidies for a stadium on the West Side of Manhattan. He doesn’t believe that those processes are necessary.

Well, I argue that democratic ideas, with a capital and a small “d,” not only are the right ones because they give people their say, but you wind up getting better policies. And if he truly had his ear and cared about what the people of the City of New York had to say about these things, and gave us a chance to talk to him about them in a way that is not condescending, then he would find out that there are a lot of good ideas out there, a lot of good ideas from the men and women on this stage about ways to govern this city differently. And he’s going to find them out. He’s going to find them out on the first Tuesday in November when we let him know that he’s going to be a one-term mayor.

BATTERY PARK MONEY FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Question:As mayor what will you do to ensure that the promise of Battery Park City is kept and revenues are spent on the production and preservation of affordable housing?

Fernando Ferrer: Proceeds from Battery Park City, the excess proceeds, were more than twice promised to the people of this city to create and sustain affordable housing. And twice that promise was violated...I want to restore that promise.

But we’re going to need, by the way, not only the proceeds from Battery Park City but so much more city investment in developing affordable housing. There are two important approaches to it: the intelligent use of public land, inclusionary zoning, and the intelligent use of public resources. Not only to develop affordable housing but to keep housing affordable. Now let’s be clear. I’ve got nothing against home ownership. Mr. Shaw made a very interesting point. We need to give people an affordable ownership opportunity. Small homes, co-ops, but we got to remember that this city is a city of renters for a whole host of reasons. And they need not to be priced out of their own town. I’ll keep the promise of Battery Park City.

Virginia Fields: I have repeatedly called for reinstatement of the funds that were established to build affordable housing through the Battery Park City funds, most recently in my state of the borough [address]... When we look at the amount of excess revenue over the next decade we could be looking at close to one billion dollars in terms of the dollars that could be used to leverage private investment in building affordable housing. So, as mayor, I will certainly reinstate that in the way that it was initially intended when Mayor Koch and Governor Cuomo worked to put it in place. In addition to that, I think it is important too to look at the inventory of city-owned land and to make sure that we are not selling that at market-rate prices as it is being done today as another way to look at addressing dollars to be able to build affordable housing.

Steve Shaw: It is true that in 1989 there was a commitment to make $600 million investment in affordable housing from funds by the BPCA. And it’s reasonable to ask for that commitment. But subsequent to that, promises that weren’t even made back then have been made and have been executed. Billions and billions of dollars in subsidies have been given out – billions and billions of dollars. But ladies and gentlemen, more subsidies is not the answer. It is true there is an area for public subsidies, in areas such as supportive housing, which I totally support. There is an area for that for helping the disabled, helping the elderly. But enough’s enough. Where I believe the money should be spent is on our mass transit system. Mass transit system is what really builds this city, it’s what makes this city, apart from the people, makes this city what it is. But the mass transit system is crumbling today. Instead this administration, rather than focusing on the existing mass transit infrastructure, wants to spend over a billion dollars so people could be ferried back to the stadium. That’s not how mass transit money should be spent. So with regards to this, I would not fight for the reinstatement of the $600 million. I would instead allocate that money to the city’s mass transit system.

REPEALING THE URSTADT LAW

Question:Do you support repeal of the Urstadt Law? If you are elected mayor what specific steps will you take to win repeal of the Urstadt Law, and restore full home rule power over its rent laws to the city of New York? How you will overcome the opposition of the governor and senate majority leader to repeal this law?

C. Virginia Fields: I think it is important to repeal this law to give the right to NYC to make decisions around rent stabilization. It’s amazing every time we go to Albany to fight in order to keep these laws in place, we’re talking to people who do not live in NYC, who do not support our concerns nor care about the impact of what is happening here.

Secondly as mayor the specific steps I would take is to go to Albany and not give lip service to it at the time that rent stabilization laws are being discussed, but on a regular basis working with not only our delegation from NYC but working with others, we believe we can turn their opinions around.

This is not something that just the mayor cares about, but many constituencies throughout the city care about this issue. So I would certainly work with other constituencies.

The way we overcome this is to do what the Democratic leader in the State Senate recently said and that is to get a majority in the Senate as we now have in the Assembly. We are close to it. We cannot believe that it cannot happen. So we have to keep working so that we have a majority of Democrats in the Senate working with the majority in the Assembly working with a Democratic mayor leading the way. In '06 having a Democratic governor. And then hold all of us accountable for the things that we say when we’re running for office to make sure that they’re the same things we do when we’re in office. And that’s how we get it done.

Steve Shaw: Typically, I believe that government closest to the people should be in charge of making the policies. I know my mass transit idea didn’t go over too well but I believe that, I believe it should be NYC that controls its mass transit rather than the MTA.

As I mentioned before I am in support of limiting regulation on housing and as a result I would not fight for the repeal of the Urstadt Law. Instead, I would focus my political capital on the ways that I believe will help New Yorkers build better lives for themselves. Work with the state legislature, work with the governor to limit the tax burden on New Yorkers, work with them to create a pro-growth, jobs-friendly environment for New Yorkers, that’s what I would focus on, that’s how I would spend my political capital.

I think it’s important for everybody to realize that when I say I’m against rent regulation people think you got to be pro-landlord. Well, if you look at my campaign contributions, granted there aren’t many of them, I’ve taken about $50 from landlords. So, I’m not in the pocket of the landlords. What I want is I want the market to be just like it is in other cities. For instance, if you go to another city, if you go to Chicago, if you go to Philadelphia, if you go to Seattle and you start looking for an apartment you’ll see a wide array of prices, prices at every price point. The reason why it is that way is because they don’t have rent regulation. That’s why it is. But in New York City, one million units are out of the market. And as a result of that, as a result of that when you go and you look for an apartment the only ones that are available for rent are ones which are thousands of dollars. That’s not acceptable. We get rid of rent regulation, we’ll make significant steps in this area.

Fernando Ferrer: In case anyone hasn’t noticed, there’s a housing shortage in this city. And in spite of the fact that there are a million non-controlled units, we have seen record high homeless rates not seen since the Depression. The two are related. People are getting priced out of their own town and it’s not right. We need rent regulation in this city.

We also need to have home rule. I’ve believed that for all of my public life. And I agree with Borough President Fields. The way to achieve that right now -- it’s achievable, it’s realizable -- is to get the Republican majority out of Albany. The way to achieve that is to elect a Democratic governor and to get George Pataki or any of his surrogates out of Albany. And the way to achieve that is to have a Democratic mayor who won’t [support] the bad and failed policies of George Pataki, Joe Bruno and George Bush.

You know this mayor’s getting ready to go to Albany to fight for the state’s $300 million for Jets Stadium. I haven’t seen much fight for Section 8 vouchers, I haven’t seen much fight for affordable rents. Oh yes, oh yes, some get a $400 rebate check from Mayor Bloomberg. But the bill you know actually never has his name on it. Did you ever notice that?

Gifford Miller: Absolutely I’ll support repealing the Urstadt Law and you don’t have to guess what I’ll do as mayor – you know what I’ve done as Speaker. As Speaker of the New York City Council, I led the Council in for the first time ever passing a resolution calling upon the state to repeal the Urstadt Law and as mayor I will fight again to make sure that happens.

There is no reason, no reason, that we should have to go up to Albany and bargain with some upstate senator for our homes. It is wrong. And I as mayor will change that, partly -- absolutely I agree with my colleagues -- by making sure that we get a Democratic Senate who will care about the needs of New York City and put New Yorkers first and just give us an opportunity to take care of our own, because we’re not asking for anything other than to be able to take care of our own. We’re not asking them for anything.

I will also get you involved in repealing the Urstadt Law. You know I took an enormous amount of heat because last year I took buses and brought working New Yorkers -– tenants -– up to Albany to lobby to make a difference. You would have thought that the walls would come tumbling down. You know, it’s supposed to be only lobbyists who have the money to be able to go to Albany and be able to lobby Albany. Well I’ll tell you, if I’m elected mayor, I will bring all of you back to Albany and we will make a statement again that we will not accept having Albany making decisions for us, we deserve to be able to make our own decisions for ourselves.

EMERGENCY SHELTER

Question:As mayor, will you promise to guarantee the right to emergency shelter for all homeless adults and children?

Gifford Miller: Absolutely. People have a right to shelter in this city. And it’s a sensible thing to do. We can’t be the city that we want to be unless we’re making sure that everyone in the city has shelter. There’s nothing more fundamental. Basic shelter.

Audience member: What do you mean by shelter?

Gifford Miller: Well, the question was about the right to shelter...We absolutely should have a right to shelter and I’m proud of the fact that not only am I saying that but as Speaker of the Council I have fought for that. Amazingly, when this administration took office they were requiring people who were domestic violence victims to show police reports before they got access to the shelter system. These are our people who are literally mothers and children on the run for their lives and the administration was saying come back when you’ve got a fully completed police report. I passed legislation in the City Council to make sure that those victims weren’t re-victimized by our system. That’s the kind of principles that we ought to be bringing to our system. As mayor I definitely will continue that.

Steve Shaw: As we examine this issue, the right to shelter, I believe there is a distinction to be made between the word “right” and the word “privilege.” I believe that when you call something a privilege that it comes with certain responsibilities. That’s what I believe comes with providing shelter, there are certain responsibilities that come with it.

Audience member: Shelter’s not a privilege!

Steve Shaw: You have to behave. If you’re having problems with drugs, you have to get counseling. If you’re having problems with domestic violence, you need to address those issues...You have the same issue that you have with school discipline. You have one or two bad kids and they mess up the situation for everyone. And as a result fewer people are willing to go to a shelter, they say, “you know what, this shelter is going to be extremely violent, its going to be very difficult to sleep there, I’m going to stay on the street.” But if instead, we make those shelters safe and we make people have responsibility, then more people will go into the shelters. And that’s what we’ve been seeing.

Virginia Fields: Yes, I certainly do support the right to provide shelter, emergency shelter as well as other housing for the homeless. And I will continue that as mayor.

But what I want to say up front is I think we’ve got to give more emphasis to prevention. We must look at creation of jobs so that people do not become homeless. We must invest in jobs at every level. I think there was an article in one of the newspapers today, people were talking about manhole covers being made somewhere in India. Why can’t we make them right here in New York City and put people to work? So, on the position side, we must look to put New Yorkers to work so that the issue of homelessness is addressed on that end.

Secondly, we must also invest in programs and services for people who might need them, whether they are alcoholism, drug programs, and supportive housing for the mentally ill because these people need other kinds of support And to the extent that we make those distinctions then we are reducing the number who end up for emergency housing overall.

So yes to providing housing for people who need it on an emergency basis and people who are homeless. It is our obligation, it is our right to do that for them. But working on the other end also.

Anthony Weiner: When the mayor gave his state of the city address he had this tone and he even had a bunting behind him that talked about how great things were in the city. And he talked about how unemployment was down and things were going so well. In fact, the truth of the matter is that last year in the City of New York, in this great city in the year 2004, over 500,000 children showed up at a soup kitchen or a church basement or went to HRA for food to eat.

Let us not be so sanguine in the success that we might have because the property values have gone through the roof to say that we don’t have challenges for those of us to face. And the fundamental difference between Mayor Bloomberg and all of us, is we, in all the disagreements we may have -- and some of them are greater than others -- in all the disagreements that we have, we are fundamentally united by one idea: that we are grateful to live in such a great city, but we are constantly dissatisfied that things aren’t better.

Mike Bloomberg gets up every morning and dislocates his shoulder patting himself on the back because when he sits down for dinner, he sits at a table full of well-to-do developers who say “Oh, aren’t you great.” Well, here’s what I’m going to do: when I get up in the morning, I’m always going to be thinking about the fact that there are people in New York City who are not getting up in a home, who are in the street or in a shelter, I’m always going to get up in the morning knowing that tonight in this city, nearly 15,000 children are going to be without a place to sleep. We can never be satisfied with that.

And that also means that standing up – and I will do this – standing up when it’s Governor Spitzer and saying, “Listen, I don’t care if you are a member of my party, I’m going to fight you every step of the way to make sure the basic needs and the basic dignity of all New Yorkers is protected.”

And that means finding a place for them to live, a job that gives them dignity, education that lets them live up to their greatest potential. And I will never, ever be satisfied unless those things are delivered to my constituents.

RENT GUIDELINES BOARD AND ONE-YEAR RENT FREEZE

Question:Will you support a one-year rent freeze by the Rent Guidelines Board this year? If you are elected mayor, what qualities will you look for in the public members you will appoint to the Rent Guidelines Board? Will you support amending the Rent Stabilization Law to allow for the City Council to vote on your appointments to the Rent Guidelines Board?

Anthony Weiner: I would support a freeze. Part of my concern is that we have started to measure too much about our success as a city by whether or not property values are rising a lot. You hear the mayor talk about this all the time. There is something that must be very nice when you see in the newspaper that wow, this apartment just like the one I own is going up in value a great deal.

But let’s look at what it’s doing. First of all, it’s forcing more and more apartments off the market because more and more people are taking rental units and converting them in to co-ops and condos. That makes it harder to find a rental apartment.

Secondly, it’s driving more and more small businesses clear out of New York. You know, when I led the fight to stop Wal-Mart from coming to Queens -– and I’m doing it now to stop Wal-Mart from coming to Staten Island –- part of it was because I believe what it winds up doing is big corporations like that drive out the small businesses that employ the young people in our community and provide people like all of us our first job.

The real concern I have is that developers in this city, the big guys, have too much access right now. Now we have a city that is driven by access to City Hall that is dominated by the big developers in our city and I’m going to change that.

Quickly on point two, I look for someone who understands every day the plight of New York renters, understands New York City, understands where to go. And as far as 3, no, I wouldn’t give the City Council that vote, I want as much authority as I can because I have big dreams for this city.

Virginia Fields:For the past two years, I have supported non-increase of rent and I would continue to do that as mayor. When I spoke before the Rent Guidelines Board last year, I made it clear that I did not support the rent freeze by the Rent Guidelines Board because we have one of the most serious housing crises in our city today. And rents continue to go up without any information or support in terms of the impact that that is having. So, yes, to that question.

The second question, if elected the type of person I would look for, is clearly someone, people like you, who are in this room -- people who are knowledgeable, people who understand these issues, people who are willing to give the time, people who really do care about this and are not going to be pressured one way or the other but will do what is the right thing to do.

And they will relate to you and hold audiences with you. I think one of the complaints that I have gotten about some of the members on the board is that they won’t meet with advocates, they won't meet with tenants. Well you don’t have that choice. You will meet with people because you are a public representative.

I’m going to agree with my colleague over there from Congress on the last one. I would not look to give this right to the City Council in terms of making the appointment or advising on it. My view on this issue -- someone who has been actively involved in this movement now for a long time, one who has invested in the building of affordable housing, one who has established a Mitchell-Lama task force to make sure we protect all of those rights -- I know that...consulting with you, talking with you, as well as the City Council, I would be able to make that appointment in your best interest, too.

Gifford Miller: First of all, the first question to me is really who are you going to appoint to this board. This board is not some abstract board. This is a board that makes decisions about people’s lives, about whether they are going to be able to stay in their homes, about whether their housing is going to remain affordable. So I think it is one of the most important appointments that a mayor can make. And I would agree with my colleagues that the kind of a person that I’m going to be appointing to that is the sort of person who understands what they’re doing. Who understands that there’s a real difference between four percent and a freeze in people’s lives.

At a time when fare hikes are going up, CUNY tuition is going up, the cost of milk going up, this is a huge decision in people’s lives. And I would want to make sure that whoever is making this decision is somebody who is a fair person, an honest person and who understands the impact of the decisions they’re making.

And absolutely I would expect that person to be the sort of a person to understand that it is time for a freeze. Why should there be a freeze? Because the way that they make this decision is skewed. They never take into account the fact that the returns the landlords are getting on their properties have been going up and up and up and up and up and up. They don’t take that into account, and they ought to.

I would support giving the City Council the right... even if I was mayor. Because if I appointed somebody who couldn’t get through the City Council, I shouldn’t be appointing that person in the first place. And so, I have no problem if I’m the mayor of the City of New York in submitting my appointments to another body for approval. I’m not going to give them the appointment power, because I believe I’m going to make the right decision for the people of the City of New York, but I have no problem having a certain level of public review for it.

Steve Shaw: I don’t believe it’s really up to the government to determine how much money a landlord makes.

Audience member: Who’s it up to?

Steve Shaw: Well, it’s up to how well the landlord operates the property, that’s who it’s up to. A landlord has every right to operate his business as he sees fit. While it’s true that not all landlords are necessarily reputable people, they have the right to operate their business and make a profit.

While I will not support a zero percent increase, what I will do is I will do every thing that I can to cut the tax burden of New Yorkers because in fact that is the largest operating expense of landlords, real estate tax. So, if you want to look at a way that you would be able to lower that, that’s the way that you do it.

Now, in terms of how I would reform the Board, what I would do is as follows. I don’t like when decisions are made with a stacked deck. Just like the MTA approved that the stadium that was going to be there. It’s a stacked deck. It’s appointed by Pataki, some cronies of his, and Bloomberg, some cronies of his. That’s not how it should be made. What I propose is as follows: the mayor has to make five appointments. What I would do is have the mayor nominate five people, have the City Council nominate five people, have public hearings, and then after all those hearings have the mayor select three and the City Council select two. This is too important of an issue to have just one person make. It needs to be made in conjunction with the entire City Council and that is what my solution would do.

SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

Question:What will you do as Mayor to ensure that additional supportive housing is provided for New Yorkers living with mental illnesses?

Virginia Fields: I know the value of supporting supportive housing, as a Council member working to increase the number of supportive housing...It worked. And it provided a safe environment for people who had tremendous needs. So one of the first things that I would do is work with our New York delegation in Congress in an effort to get federal legislation changed to allow subsidies for permanent supportive housing. That would go a long way in terms of making this more of a permanent solution.

That is related to an overall reform or initiative that I would take with respect to our budgets. I would immediately work with our state legislators and our people in Washington to advocate for the things that we need in New York City, including more money for permanent supportive housing. Leading the charge because when we involve our legislators in both areas –- Albany and Washington -– we’re taking care of the business of New York City. Because you know what? The people the mayor represents are the same people Congress people represent, the same people Senate and Assembly people represent. So I would...include them in addressing these issues. And I cannot think of a more important one than to work for federal legislation to change and provide... funding for supportive housing.

Gifford Miller: Absolutely. I’ve long supported moving toward a supportive housing approach from the current scatter site housing and shelter approach. And there’s two reasons: First of all, it’s cost effective. Supportive housing saves money. Because when you can put somebody in an environment where they are going to succeed, give them an opportunity to really hold on to their home and to participate in society with the array of services that they need in order to be able to hold their own, you save money, not just in terms of the shelter system but in terms of the additional costs from entrance into prisons or so many other of the enormous costs that come when we force people to make desperate decisions. So supportive housing is a good investment for the city.

But much more importantly it’s the right thing to do. What we’re here to talk about is how we can help people live in their own homes and provide for themselves. And there’s a lot of New Yorkers that need some support in doing that. So I strongly support supportive housing...

In the Council, I and some of my colleagues have pushed hard for the administration to adopt this...approach, and in the last year they’ve made some progress. You know it’s good to come up here and criticize and say everything that they’ve been doing wrong, but in the last year they started to make some progress towards investing more in supportive housing and moving away from the scatter site housing and that’s the right thing to do. And I as mayor would continue to do it.

Steve Shaw: I believe that supportive housing is a good use of public funds...It attacks the problem at the root, before it becomes a much worse problem. And that’s where public money should be used –- to solve these problems before they become huge issues. What I will say, however, is that using the word “permanent” is very dangerous. Government only has a finite amount of funds. So, if you say that everyone is going to get permanent, then what that’s going to do in the end is it’s going to limit the funding that you can provide for the people on the front end, which is where I think it needs to be focused. So, while I support supportive housing, it cannot be permanent in all cases.

Anthony Weiner: You know this is kind of like shooting fish in a barrel, but I disagree with Mr. Shaw. But...I give Mr. Shaw a great deal of credit. I think if Mike Bloomberg were here, we’d all be a lot better off.

As a Democrat I have no fear talking about...housing services to the disabled, housing services to those with mental illness as not just being something we leave to the whim of the capitalist market. We have to recognize one of the reasons that government exists is because we’re not in this as individuals. We’re not in this as disjointed from society. All of us benefit when those who need care get care. We’re a more civilized place and the economy as Speaker Miller points out winds up benefiting when we care for one another. I don’t believe in the Mike Bloomberg Republican model that says, “You know what? If the free market doesn’t give it out, we’re not going to give it out.”

We have to recognize that programs the federal government has come up with –- like the Section 202 program that provides housing for seniors so that they get out of their market rate apartment (that maybe has two or three or four bedrooms but no services), free[ing] that up for a working family... The government says, “Look, if you find a sponsor and you find a piece of land, we will underwrite virtually all of the construction, if you agree to have these services available for seniors and the disabled.” It’s a model that worked; therefore, George Bush has done away with it. And we have to recognize that there’s value to bringing those programs back.

New York City and New York State entered into a rather progressive agreement, something called the New York New York agreement, in which they said, “You know what? The city and state are in this together, to provide housing for those who need these services.” Naturally, Governor Pataki and the state have walked away from it. Wouldn’t it be remarkable if at the Republican Convention Mike Bloomberg stood up and says, says this to his Republican brothers and sisters, says, “I am here to welcome you to New York and to express my outrage at the 70 percent cut in housing.” It would have elevated that issue to the front pages of the New York Times and finally gotten a national debate. That’s why it’s going to be different with Mayor Anthony Weiner than it was with Mayor Mike Bloomberg.

INCLUSIONARY ZONING

Question: Do you support a mandatory approach to inclusionary zoning, requiring developers to produce a percentage of affordable housing? If so, what percentage do you believe is appropriate? Do you believe that the units developed as affordable should be permanently affordable – or be permitted to convert to market-rate prices after a set period?

Gifford Miller: I absolutely support inclusionary zoning. In fact, I haven’t just said I support it, I’ve forced inclusionary zoning into our zoning amendments that the City Council has been making over the last three years.

When I took office, the administration said, “No way, no how, there’s no way.” But look if we’re going to give property owners the enormous value that comes from upzoning their properties, we ought to take some of that value back for the public.

We have to be realistic. The federal government is not going to come in and bail us out on affordable housing. Because they’re in the process, as the congressman said, of cutting support for housing. The state is not going to come in and bail us out on housing. Cause they’re under court order to meet our schools’ needs and they’re not even doing that. So what do we have as an opportunity? What we have is tools like inclusionary zoning, which says, “You know if we’re going to let you build this high, you can build a little bit higher but you got to use a significant portion of that for affordable housing.”

Not only have I said that I’m for this, I forced this into our plans, as I’ve said. Just recently with the Hell’s Kitchen-Clinton rezoning that we did, I set a new standard for what is going to be acceptable in terms of rezonings: 28 percent of that housing is going to be created affordable housing and yes I believe it should be permanent. Because we’re giving these benefits permanently to property owners, we ought to make the housing we’re creating permanent. It’s the right thing to do.

I’m very proud of the work that I’ve already done on inclusionary zoning, and as mayor I would continue that not just in Manhattan but all over this city in order to create more affordable housing opportunities for all New Yorkers.

Steve Shaw: The issues that I have with inclusionary zoning are as follows. The first is, what it does is it’s putting investment in parts of the city which are of less need than much others. For instance, many of the inclusionary zoning programs are in Manhattan, excellent neighborhoods in Manhattan. They’re in parts of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which is an amazing neighborhood. I’m from Brooklyn. Congressman Weiner’s from there, I actually live there right now. Manhattan – and those areas – is not really where we need the investment. It needs to be done in the outer boroughs, in parts, Brownsville, Brooklyn, East New York, Brooklyn, parts of Queens, et cetera, et cetera. That’s where it needs to happen. But if all the incentives are toward areas which are already prime neighborhoods it doesn’t make a lot of sense...

The second issue is this: part of inclusionary zoning is upzoning. So, we’re going to let more units be built. Has anyone been to Staten Island recently? Has anybody read the Staten Island Advance? The one issue which they talk about time and time again is over-development. What over-development does is that it taxes the roads, it taxes mass transit, it taxes the schools. It overpopulates those areas. So, it’s not a solution.

In addition, one of the parts of inclusionary zoning is this subsidy called 421-a, where I believe developers get about a 10-year tax abatement. There are all sorts of abatements if you are going to build a ritzy new building which is part of this, but how about the tax policy for the small business owner, the person who really needs it? The person who is being driven out of New York City? That’s what tax policy needs to be focused on and that’s what I’ll do as mayor.