Redefining Economic Development

A fledgling coalition of some of the most prominent economic development groups in the city have been meeting over the last year to create a blueprint that offers a comprehensive and alternative vision of what development should look like in the Bloomberg era. “Re-Defining Economic Development” -- or RED NY, as this coalition’s efforts are called -- began as an attempt to make new development projects in the city more accountable. Its participants all have the conviction that New York’s prosperity should be shared more broadly throughout the city.

Planning Sessions

The roots of Re-Defining New York go back to a series of meetings in 2004 -– the Subsidy Accountability Strategy Session -- that were put together by Jobs with Justice New York, a group that organizes to support the rights of workers and increase their standard of living. At these meetings more than 40 organizations, including the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, Good Jobs New York and the Pratt Center for Community Development, attempted to figure out how to demand more public benefit from projects that received incentives and subsidies from the city and state coffers.

The sessions didn’t produce the landmark organizing campaign that the participants had hoped for. But it did highlight the considerable economic development activism across the city. And so more than a year later, at a meeting in November of 2005, Jobs with Justice, along with Good Jobs and Pratt, again invited dozens of activists to participate in a series of meetings, this time called Re-Defining Economic Development (RED NY).

At this November meeting, participants offered a look at their current campaigns for progressive economic development, including efforts to:

- expand the New York living wage law

- establish immigrant worker centers

- create green spaces in low-income neighborhoods

- connect development proposals to workforce development

- regulate discriminatory financial services.(I made a presentation on behalf of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project).

This gathering did not try to come up with a new city-wide campaign, but rather to coordinate existing organizing efforts. The ultimate goal was to craft a comprehensive template for the public and private pursuit of economic development in New York City that served the interests of New Yorkers with low and moderate incomes.

The Underbelly of New York’s Success

The perspective of the RED NY organizers was best captured in a presentation made by the executive director of the Pratt Center, Brad Lander (who is also co-founder of this community development topic page). Lander first described the economic development priorities of the Bloomberg administration as laid out in the administration’s own literature: To make New York City more livable so that residents, workers and business owners would want to be in New York; to create an environment in NYC that enables businesses to generate jobs and be competitive; to diversify the New York economy and make it less Manhattan-centric and less dependent on the financial services industry.

But then Lander juxtaposed these laudable priorities with the starker underbelly of economic life in New York City. Yes, over the past 15 years, the city has been resurgent in several ways, with a declining crime rate, improved public transportation, extensive neighborhood re-development, rising property values and expanding service and entertainment industries. But in that same time, the city has experienced more poverty and widening income disparities between rich and poor. Rising costs in housing, health and energy are making it increasingly difficult for people to survive. New York has seen a decline in industrial employment, a concentration of environmentally destructive uses and a corresponding lack of quality-of-life investments in low-income areas, and a continued flight of the middle class to the suburbs. Property, rather than the lives of working people, has become the center of discourse and thinking around economic development. To help make his point, Lander showed pictures from the Bloomberg administration’s development plan dominated by pictures of tall buildings and a smattering of shiny white faces.

Andrew Brent, a spokesman for the Bloomberg Administration’s Economic Development Corporation said that it would be a “complete mischaracterization of the Bloomberg Administration’s economic development plan” to suggest that it puts brick and mortar before people. “We’re creating jobs in all the five boroughs”, Brent said. “To me that’s putting people first.”

Although he said that it would be inappropriate to comment on RED New York until it officially presented its “blueprint”, Brent said that he didn’t interpret RED New York as being critical of the administration.

Next Steps

Since the November meeting of RED NY, a working group consisting of more than a dozen organizations has emerged to establish a set of principles that could possibly be “endorsed” by a broad range of organizing and advocacy groups in the city. One suggestion is that these principles could then be used to judge the candidates for governor, and encourage them to adopt a progressive platform on economic development. RED NY is also organizing training sessions designed to help people from different economic development disciplines establish common ground and a common understanding of the issues.

The greatest challenge for RED New York is to turn what is now an ambitious conversation about a new economic development “vision” into something that will have a measurable impact on people’s lives. One problem is that economic development means different things to different people. Those, for instance, working to provide health benefits for home care attendants in Flatbush may be hard pressed to be part of the same “blueprint” with those trying to preventing toxic dumping in the South Bronx or those pressuring a developer to provide job training in Harlem.

But Michelle de la Uz, executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, is very clear on the practical uses for a new economic development blueprint. The Fifth Avenue Committee is one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit to stop Bruce Ratner from demolishing six buildings en route to building the Nets stadium and hundreds of commercial and residential units over Atlantic Yards in downtown Brooklyn.

What de la Uz envisions is a set of standards for job creation, environmental impact, buy-in from the surrounding area, etc. that the city or a private developer could be held to whenever they planned to use public resources. In her opinion such a standard would have set a much higher bar for Ratner to clear before he was able to pursue the Nets Arena project. The surrounding neighborhood, in de la Uz’s opinion, would have had “real” community benefit “guarantees” instead of what she considers to be the highly questionable and unenforceable promises for job creation and affordable housing that Ratner was able to negotiate.

“This process is long overdue”, insisted de la Uz. “I wish we had the political will a year ago to implement what will eventually come out of the RED NY process.”

Mark Winston Griffith, co-director of the Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project and a fellow at the Drum Major Institute, has been in charge of the community development topic page since its inception in 2003.Â

2 Fultons, 2 Futures

Â

Every weekday for 180 years, large men carrying fishhooks and wearing rubber boots gutted 300-pound tunas on Manhattan's Lower East Side waterfront. In November that chapter in New York's history ended as the Fulton Fish market moved to a modern facility in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx.

The fish market's move promises great changes in both the neighborhood it left, and the neighborhood it joined.

View a slide show on plans to improve Hunts Point. Read an article on ideas for the area around the old fish market

1. Remaking Hunts Point (slideshow)

2. Making The Old Fulton Fish Market Into Something New (article)

A Library Opens In The Bronx

In the month since the opening of the Bronx Library Center on Kingsbridge Road, at least three times as many people have been signing up every day for computer training classes than at the old Fordham Library that it replaced. During a recent drive, the new library had registered 150 students for classes by noon. This makes sense of course, since there is so much opportunity at the library to use the skills they acquire.

The Bronx Library Center is a technology haven, a focus that is clear as soon as you step beneath the swooping 80-foot-tall roof over an open-glass facade and walk onto the elegant terrazzo floor of the main entrance: there amid the Minnesota granite of the interior are large plasma screens and scrolling electronic announcement bars, both of which highlight forthcoming library events.

There are 127 computers throughout the building wired for Internet access. The library also has wireless capabilities, and provides 30 laptops that patrons can use anywhere on the premises.

Another technological innovation is self-checkout; there are still human librarians at the checkout counter, but their work is now made a little easier.

The library offers state-of-the-art technology in other, less obvious ways as well. It is the first "green" public library -- indeed, the first fully green public building -- in New York City, according to the the U.S. Green Building Council. It is largely illuminated by natural light and equipped with passive solar energy devices; energy costs are expected to be 20 percent less than a standard code-complaint building. Also, as the library itself puts it: "Approximately 80 percent of the building's wood-based materials were grown in environmentally responsible forests; over 90 percent of demolition debris was recycled; and 55 percent of its construction materials were manufactured within 500 miles of the site."

It is bracing to realize how long it took for the Bronx Library Center to be realized. The need for a new library was clear by the mid-1980’s. Officials say a new building did not become feasible until Con Edison closed its Kingsbridge Road facility in 1999. The library system acquired the land in 2001, and the new facility took five years and $50 million to build, with a combination of public and private funds.

In one way, though, the birth of this new library is well-timed. Since the Bronx Library Center was first conceived, a technological revolution has occurred in how people access information -- and not just how, but who. If more than 95 percent of public libraries in the United States provided Internet access by 2004 (up from 28 percent a decade earlier), individuals with very low incomes --$15,000 or less -- make up the largest proportion of Internet library users.

For many residents of the Bronx, which is New York City's least prosperous borough, the library is their best option for Internet access. At least half a million people are expected to visit by the end of the year.

Many won't just be checking out the computers. Although its technological offerings are impressive, the Bronx Library Center continues to provide services associated with traditional libraries. The library has the largest public reference book collection in the Bronx, as well as 200,000 print and audiovisual materials available for checkout. It features a 150-seat auditorium for public performances, and a story hour room for readings to children. Individualized career and educational counseling is available, as well as instruction in reading and writing for adults.

For all that, the library officials understand that the technology will be the main draw. But one of those officials, Gayle Snible, has already noticed a heartening trend: Many people have come to the library for computer training, and departed with books in their hands.

Marcus A. Banks is a librarian at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer CenterÂ

Livable Streets (For People, Not Cars)

The simplest way city officials can improve the quality of life for every New Yorker is to start thinking about the city's streets and sidewalks in a different way. That is the message of a new effort called the New York City Streets Renaissance Campaign, which was launched recently with an exhibition at the Municipal Art Society entitled “Livable Streets: A New Vision for New York.”

The Livable Streets exhibition is filled with ideas to make the streets more enjoyable, such as carving out plazas (complete with chairs and tables) in such barren, traffic-clogged intersections as Astor Place. (Click here for links to some brief videos).

But it also offers a wealth of examples from large cities throughout the world that already have given their streets back to the people. Over the last 25 years, for example, Copenhagen drastically reduced traffic and created one of the most elaborate and extensively utilized pedestrian and bicycle networks in the world. Cities like Philadelphia and Chicago are creating safer streets for people of all ages and abilities, reducing pollution and health risks, and making both business districts and busy neighborhoods easier places to walk to, and walk around. They are doing all this without compromising the regional road networks.

Unfortunately, this is not what’s happening in New York City. Here there is a disconnect between the city’s land use and transportation policies.

The City’s Car-Centered Policies

The limitations of New York City’s transportation infrastructure are becoming more and more apparent, especially given the tens of millions of square feet of new office, retail and residential development that are planned for the city, much of it in high-density clusters. Simply dumping more traffic onto local streets may very well make the new developments less attractive and accessible, and scare away investors.

A few mass transit projects aimed at improving accessibility in Manhattan, like the Second Avenue subway line, may help, but they won’t fully address the city-wide problems of gridlock, air pollution, noise, and dangers to pedestrians and cyclists caused by dependence on motor vehicles.

The problem is that the city’s transportation policy is mainly oriented towards moving as many vehicles through the city’s streets as quickly as possible. This is a monumental engineering task in a city with so many pedestrians, residential neighborhoods, and local retailers. And it doesn’t work. The more the city dedicates its asphalt to cars and trucks, the more vehicles that show up and fill the streets, making things worse instead of better. The losers are the majority of New Yorkers who walk and use transit, and the growing crowd of bicyclists (some 140,000 daily, despite enormous obstacles and unsafe conditions). New York City has the largest mass transit system in the nation, yet New Yorkers have the longest commutes in the nation because of vehicular traffic congestion.

A Better Goal: Moving People

The Department of Transportation should drop the goal of moving as many cars as possible and focus instead on moving people. According to Transportation Alternatives Executive Director Paul Steely White, the city “should follow London’s lead and develop new longer-term and more meaningful performance targets that aim to reduce traffic volumes and increase biking, walking and transit use.” Currently, New York City’s Department of Transportation ranks intersections by their “level of service” with the highest marks going to intersections that move more vehicles with the least delay. People on foot or bikes are not in the formula. But often we should be slowing traffic to make our neighborhoods safer rather than trying to speed it up. The transportation department doesn’t consider qualitative factors such as the vitality of shopping districts, public plazas, and residential streets.

Instead of starting with the assumption that the city’s street network has to accommodate as many cars as show up, the department could start by asking how much traffic the city wants, and then plan for the street system that’s needed to carry that traffic. Since the majority of New Yorkers don’t depend on cars, the central focus of planning could be on how to improve the infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists. Instead of only measuring car travel, we could measure how pedestrian and bicycle flow (and safety) is helped or hindered by the minority traveling in vehicles. We could plan for the city’s 12,000 miles of sidewalks instead of using them as targets for ticket blitzes. Efforts by the Department of Transportation to create a better environment for cycling are diminished by the agency’s inability to do much more than paint stripes along the side of streets that continue to carry huge volumes of vehicular traffic.

Sustainable Transportation Policy?

It might be productive for the sponsors of the Streets Renaissance Campaign -- Transportation Alternatives, The Open Planning Project, and Project for Public Spaces -- to try to start a new dialogue and share their vision with city officials. The political obstacles for this vision should not be underestimated. It has not been long since Mayor Michael Bloomberg was forced to withdraw his proposal to put tolls on the East River bridges, a simple measure that would have reduced traffic in Manhattan. On the other hand, it is no secret that Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff, who in the mayor’s second term has been charged with overseeing the Department of Transportation, commutes by bike on one of the city’s few safe off-street greenways. Perhaps the Department of Transportation will be prodded to envision how the city could be filled with safe, planned bicycle ways that are more than just stripes on pavement.

The dialogue could be broadened to include the city’s health officials, who are grappling with epidemics of asthma, obesity and diabetes that are related in one way or another to over-reliance on the auto. A 1996 study by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that every year over 46,000 New Yorkers die from illnesses related to particulate air pollution, most of which is related to traffic. Perhaps it’s time for the city’s analysts to tally the costs of this devastation in the Department of Transportation’s management reports.

Now is a good opportunity to usher in the concept of “sustainability” in the New York policy arena. This term started with a 1987 United Nations report on the environment and is used around the world to mean planning to meet present needs without jeopardizing the needs of future generations. On the West Coast and in some other large U.S. cities, sustainability is on the lips of elected officials and shapes their approach to planning. Seattle’s growth plan, for example, is called “Sustainable Seattle.” It requires that the planning horizon for new projects stretch beyond the terms of the bank loans and that new development goes along with planning for the city’s infrastructure and the quality of life of residents and workers. And perhaps city officials will look closer at the connections between land use and transportation. Some of the new mall-like mega-development in the city includes parking that induces more cars, displaces mixed-use neighborhoods and local retail centers that have had high proportions of pedestrian and mass transit use, and in several generations will transform New York from an open city with many choices to a city of enclaves no different from any other in the nation.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

Loving The City's Infrastructure -- And Explaining How It Works

Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club met with city official Kate Ascher (she is executive vice president for infrastructure at the Economic Development Corporation) to discuss her book "The Works: Anatomy of a City." An edited transcript is below.

Gotham Gazette: What inspired you to do a picture book about the city's infrastructure?

Kate Ascher: I love infrastructure. Big things, and the way things work, have always interested me.

Kate Ascher: I love infrastructure. Big things, and the way things work, have always interested me.

I didn't really think about writing a book until after 9/11 when in the newspaper you found a lot of these info-graphics about the bathtub at the World Trade Center, and the slurry wall, and the Verizon building that came tumbling down. And I remember thinking about David Macaulay's book The Way Things Work, and I went around looking for a book that had all this stuff in it. There hadn't been anything written that was at all similar since 1950, and even that book was not graphic at all. It was all engineer's prose about how the subways work; it was very dense. I thought this would be much more accessible to a lot of people.

Gotham Gazette: Was there one thing that you found particularly surprising that people did not know about the city's infrastructure after 9/11?

Kate Ascher: I guess it was some basic stuff about the trade center, how it was built, and stuff I knew from having worked at the Port Authority. People seemed horrified that in one fell swoop all these systems could go out. But it could happen anywhere, particularly in lower Manhattan. Everything is just built on everything else.

Gotham Gazette: You write in the introduction to the book that New York City is more dependent on infrastructure than other city in the world. Can you elaborate?

Kate Ascher: Every city is pretty reliant on infrastructure; I think what we have is more communal infrastructure. We tend to rely on these integrated systems like the steam system or the central sewage system because we're such a dense, vertical city.

The city can't really function without elevators, and it can't function without a subway, which both rely on electricity. I guess you could make an argument that we're more dependent on power than other cities, where people can at least get in and out of their house without electric power.

Gotham Gazette: Is there anything that our density allows us to do that you couldn't do in a less dense city?

Kate Ascher: You certainly wouldn't see the value of things like massive subway systems in a less dense city. It does make us more energy efficient.

|

Gotham Gazette: Do you think that as a whole New York is better served by its infrastructure, or worse served? Or is that even a fair question?

Kate Ascher: I would argue that our infrastructure is probably as good as almost any city. What I think is really interesting about it is that it is so very old. It was designed 100 years ago, when the city was a fraction of what it is now. It really seemed to have lived up to the task of expanding to accommodate twice the number of people, three times the number of people.

Gotham Gazette: Are there places where we can see it getting stretched?

Kate Ascher: I can't offhand think of an example that is a weak spot in our infrastructure. But my guess is without investment now there will be some things that will be creaking and breaking down soon. The water system is a great example of something that has been identified as needing investment, and the investment is being made in a third water tunnel. Were that not underway, that could be a real vulnerability.

BIG PROJECTS

Gotham Gazette: The third water tunnel is one of several big projects you outline in the book. Can you talk about which projects are the biggest, and tell us about them?

Third Water Tunnel

Kate Ascher: The water tunnel is the biggest project of all, and you can actually see some of the shaft work on the West Side not far from Penn Station. That project won't be done until 2020. Eventually it's going to bring water to the city.

It's been going on for decades; I'm not sure when it was started.

Book Club Member Jim Matthews: I actually worked on that when I was in school, at the field office at Roosevelt Island. That was 1986. At that point, we were rounding up the first phase of construction. They had the line already built from the Bronx down to Roosevelt Island.

Gotham Gazette: Will we get anything new when that is finished, or will that just keep the service from deteriorating?

Kate Ascher: The two main water tunnels serving the city lose many thousands or millions of gallons of water that just pour out of them each day because they are leaking. But they can't really attack those leaks, and do the maintenance work that is required, until there is a backup system.

I'm not an expert on this, but as I understand it the tunnels essentially can't be maintained, can't be checked, because we're so dependent on them. Nobody wants to shut off the water moving through the tunnels because we're reliant on them, but also in part because they're afraid the tunnels may implode when that pressure is removed.

So the idea is to have this third water tunnel, start using it, and then be able to take those other tunnels out of service to be maintained in turn.

New Bridges, Old Bridges

That’s probably the biggest capital project underway, but there are plans afoot to build a new bridge connecting Staten Island and New Jersey to replace the Goethels Bridge, which is aging.

The city is also selling the Willis Avenue Bridge, one of the little bridges that goes across from the Bronx to Manhattan. I guess anyone who wants it can take it free if they can comply to the constraints about keeping it intact and paying for it to be moved. It is being replaced.

Gotham Gazette: So what they're offering up in the Willis Avenue Bridge is free scrap metal, essentially?

Kate Ascher: If you want a big souvenir and you have a place to put it. It's not a small undertaking, and the city's not going to pay for it to be preserved, because the city doesn't really care.

Deepening New York Harbor

Gotham Gazette: Another project that you write about in the book is the deepening of the harbor. Can you talk about what that project is and why it's necessary?

Kate Ascher: I could talk for a very long time about that; I spent about five years of my life fighting with the Army Corps of Engineers about it.

The deepening of the harbor is not something that's happening just now. It has been happening pretty consistently since the beginning of the century, since the natural depth of the harbor is 17 feet. It's sandy, because the silt comes down the Hudson. This was fine when you had little skiffs and rowboats but as soon as you began to have bigger steam ships and cargo ships it wasn't deep enough.

Now they've gotten to the point where to get down deeper in a lot of the areas that are the shallowest you basically hit sheer rock, so you can't just dredge it up with a dredge. You have to go in and blast the rock to smithereens and then literally pick the rock up and dispose of it in a certain way. Mostly this is being done for the ships coming into the harbor and headed to Newark Bay, which are the biggest container ships that require the most depth.

|

|

|

It's a very big project. The cost of deepening the harbor from 45 to 50 feet – and then the corps will look at taking it down from 50 to 55 feet – is in the billions of dollars. It's funded two-thirds by the federal government, and then there's a local part that the Port Authority usually pays. At some point last year there were 70 pieces of dredging equipment in the harbor working on this project, which was the largest fleet of dredging equipment anywhere in the world.

There are some real noise issues with Staten Island, because some of this is in the Kill Van Kull, which is the channel that runs between Bayonne and Staten Island. Apparently they have to let all the neighbors know when they're going to blast so people don’t think it's an earthquake. It's pretty cool.

Raising the Bayonne Bridge

A related project that has not been formalized is the raising of the roadway on the Bayonne Bridge. A few big container ships have nicked the bridge, which is just a little bit too low, as they ride through the Kill van Kull. So the Port Authority has been looking at the costs and the physical requirements associated with raising the bridge ten feet or twenty feet.

They plan basically to keep the arches the same and lift the roadway. But it's not that easy; it will cost $200 or $300 million to do that. What kind of annoys me is that there are five ships in the world that need that extra height. That's a lot of money for some private companies to have greater efficiencies.

Gotham Gazette: What happens when a ship nicks the bridge?

Kate Ascher: They get in trouble.

Gotham Gazette: But there hasn't been any serious physical effects?

Kate Ascher: There hasn't been. They're not going very fast.

Jim Matthews: I know a little bit about that. The ships typically hit some superstructures of the mast, which are basically big poles. They might get a little bit banged up, but nothing significant. It's not like you have in the gulf, where you have barges running into bridges all the time and knocking them off their moorings.

Kate Ascher: Many ships that come into the harbor have been designed basically to max out in height to come under the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. The funnel of the Queen Mary Two, for instance, is designed to come within six or 10 feet of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge when it passes beneath its center.

"The real question is: are we being as ambitious as people were 100 years ago when they set up these very elaborate systems. I don't know that we're being as visionary about infrastructure as perhaps we should be."

I was actually at a meeting where they thought they had their calculations wrong. The bridge sinks about 10 to 20 feet in the summer when its fully loaded; it's the nature of the steel. At this meeting they thought that they hadn't taken into account that 10 to 20 foot drop, and were frightened that they were building $800 million worth of ship that couldn't come to New York. Luckily for them, they had taken it into account, but she still sails very, very close to the center of that bridge.

Other Projects

So those are the big projects. Then there are some more esoteric areas:

There's probably $500 million in the city budget to build stations where the city's garbage is going to be put into containers and put on trains or barges to be put in landfills in other states.

There's a lot of money involved now in developing a filtration plant to filter some of the city's water in Van Cortlandt Park. That was a big discussion with the community. That's been approved, and they're literally taking up the entire park, putting in the filtration plant, and then putting the park back down on top of it.

So there are some huge projects afoot, and there's always an awful lot of repair work.

DEVELOPMENT BATTLE

Gotham Gazette: There's a conventional wisdom in New York about big projects, which is that the politics are so intractable. I was surprised to hear about some of these enormous projects that haven't seemed to spark much controversy. Did the battles just happen in the past, or are there certain types of projects that for some reason are immune to that type of politics?

Kate Ascher: Well, you can't get anything done without some kind of a battle, but it's not necessarily a citywide battle. Nothing gets done easily. I'm not sure it ever did if you look back at history.

I sometime wonder how they even created the New York City water system. They took 2,000 square miles of upstate New York and flooded dozens of communities and built these aqueducts and these reservoirs. You could never do that today -- not a prayer! But somehow they were able to do it.

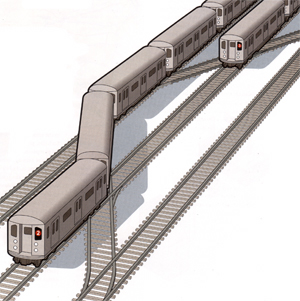

THE SUBWAY

Jim Matthews: One of the other projects that's underway, at least in very initial stages, is the 2nd Avenue Subway and the East Side access, which is a perfect example of one of the projects that has run into numerous problems throughout its history. It was started in the 1920s. They built a chunk of it in the 1960s and then basically abandoned it. The subway is citywide – everybody seems to have ownership of the subway, essentially. Everybody seems to be in tuned to what's going on with that. When it's a localized project, there seems to be less interest overall.

Jim Matthews: One of the other projects that's underway, at least in very initial stages, is the 2nd Avenue Subway and the East Side access, which is a perfect example of one of the projects that has run into numerous problems throughout its history. It was started in the 1920s. They built a chunk of it in the 1960s and then basically abandoned it. The subway is citywide – everybody seems to have ownership of the subway, essentially. Everybody seems to be in tuned to what's going on with that. When it's a localized project, there seems to be less interest overall.

Kate Ascher: When they're localized projects -– I hate to say this, but basically it ends up in a negotiation between a city agency and a fairly finite group locally. You can work through a solution. When you work on a project like the 2nd Avenue Subway that touches communities up and down the East Side, however, it's much harder to work out a package or a deal that's going to make them happy.

Gotham Gazette: Do you think that project will ever actually happen?

Kate Ascher: I don't think it will happen in my lifetime. Look at the history: fits and starts, money put in and taken away. There just never seemed to be the will to push it forward, because politicians change, and times change.

So my guess is that it will get built in parts over an extended period of time. I don't think it will ever be what it was originally intended to be. But it may turn out to be something useful even if it's only a partial completion.

How NYC's Subway Stacks Up

Gotham Gazette: One thing your book does is compare our subway system to other systems around the world. I was wondering if you could just go into that a bit. Where are we better? Where are we not as good?

Kate Ascher: I wouldn't attempt to compare our service to the service in Paris or something like that, but what the book does do is compare the number of route miles and the number of stations. I think we have more stations than the Moscow, Japan, or London systems.

So it's not the largest system in terms of the number of people, but we do have some of the routes that are the longest -– like the A train that goes out to Howard Beach. We also have some very deep stations, like the A train in Washington Heights. It's not that it's bigger in volume, it's that we have more stops.

One of the things we do have that none of those systems have is that we go all night. All the systems in the world's other major cities close at one or one thirty in the morning, and reopen at five or five thirty. Ours goes all night.

"I don't think [the 2nd Avenue Subway] will happen in my lifetime. Look at the history: fits and starts, money put in and taken away. There just never seemed to be the will to push it forward, because politicians change, and times change."

Book Club Member: That's why they're so much cleaner.

Kate Ascher: It could be. It's interesting to me to think why are we so different than London, Moscow, or Paris? They have people who have to get to work in the middle of the night too.

Gotham Gazette: Any ideas why?

Kate Ascher: I don't know. I lived in London for ten years, and probably could have asked someone to find out.

Jim Matthews: They typically shut them down at night for maintenance primarily, whereas New York does the maintenance while the system is operating. When the trains aren't running on weekends, for example, that's what it means.

"PHANTOM INFRASTRUCTURE"

Book Club Member Margie Dotter: Do you know anything about the hidden subway stations?

Kate Ascher: There are a number of platforms that are around that aren't used anymore, but there are also at least half a dozen – and maybe more – unused subway stations. There's a little map in the book showing where they are.

Some of them you can see. If you stay on the 6 train – and you're not supposed to – as it comes around City Hall, you can see the old City Hall Station, the real elegant one. It's only about four cars long, so it could never handle a real train. On West Side subways up between 86th Street and 96th Street there's the 91st Street station on the 1,2, and 3 lines. You can see some dim lights and graffiti. But somebody decided it was just too close to 96th Street and 86th Street. There are a bunch of them around. They're cool.

Gotham Gazette: It seems like they should close the 18th street stop on the 1.

Kate Ascher: I'm sure there's a political constituency to keep it open.

Book Club Member: I think the closest two stops are out in Brooklyn.

Kate Ascher: Well, there's a big constituency for not closing things once they're open. But somehow they did manage to close all those stations over time, with service changes and stuff like that.

There's a lot of fun stuff with the subway, weird little infrastructure stuff that's hidden unless you work with the MTA or know someone who works there. And then there are all kinds of interesting catwalks and escape passageways. Things that are all around us, but we don't really see.

Book Club Member Did you find in the course of your research any other phantom places underground, in other systems or whatever?

Kate Ascher: Well, the word phantom is very romantic. It's basically unused stuff. When pipes go out of service for whatever reason – because they've been supplanted by some kind of other technology, or something has been moved in another direction – it's amazing how many of them are just left in situ.

There are the old tubes from the pneumatic mail system. There are sewer pipes that are not in use any more that people are thinking about using for different types of telecom service, laying cable and stuff like that. There's an awful lot.

Gotham Gazette: In your book you mention some other type of non-functional infrastructure.

Gotham Gazette: In your book you mention some other type of non-functional infrastructure.

Kate Ascher: There are the crosswalk buttons, and I think there are something like 3,200 of them. A quarter of them work. They once worked, and they no longer work.

There are also red light cameras that look at an intersection and take a picture of your license plate as you violate the red light. There are a relatively small number of them, maybe two dozen, maybe fifty, that work. They definitely work, because I've gotten two tickets. Two! And both of them I was like "I didn't run a red light!" And then they send you the time and a picture of your car going through the red light, so you can't argue with it.

So I know where those two are. But in addition to the however many they have that really work, they put in an additional two hundred that are total fakes, but that are meant to make you feel like you're being watched. You're not being watched, but they're a lot cheaper than having a system that has 250 live, complicated cameras with sensors. Most of those are just for show.

Gotham Gazette: Are there other things that are just for show?

Kate Ascher: I can't think of anything offhand –

Book Club Member Calvin Johnson: There are fire hydrants that are just for parking tickets. They are not hooked up to the water veins, they're just there as a revenue generating measure – for parking tickets. Or at least that's the urban legend.

Kate Ascher: That seems like a cynical view to me. There may well be ones that are not connected, but my guess is that they were once connected.

There is a philosophy [behind leaving stuff in place when it stops working]. The actual cost of removing those traffic push buttons that don't work is $400 a pop. So it's not huge, but I guess they're not hurting anything. Arguably, that's different than a fire hydrant, because that is street clutter. You can imagine that if it's not working it should be taken away. But a push button on a pole?

INFRASTRUCTURE, POLITICS, AND THE CAPITAL BUDGET

Book Club Member Magda Adboulfadl: Can you talk a little bit about the politics of the capital budget? It's such a long-term issue being run by short-term mayors, and it seems like it would be easy to ignore. I was wondering how insulated from politics the capital budget is.

Kate Ascher: In the capital budget process there are teams of people representing each of these infrastructure interests who very clearly set out what needs to be done. You will find in this capital budget cycle that the Department of Environmental Protection is going to ask for capital funds to implement the filtration plan in Van Cortlandt Park, and to do a variety of things in Croton Reservoir. Those projects will get resourced, at least under this mayor. He's very concerned about that. I don't know that previous mayors have slashed the budget to those. I really have no indication that they have.

I guess the real question is: are we being as ambitious as people were 100 years ago when they set up these very elaborate systems. I don't know that we're being as visionary about infrastructure as perhaps we should be.

Calvin Johnson: I had a question about jurisdiction, and how many different governmental bodies you worked with in doing the research for your book – federal, state, local, public authorities – and how they all interact with each other in the city's larger infrastructure?

Kate Ascher: That's a big question. The city's infrastructure is so many different things. I broke the book up into five sections just to make iT manageable. But even within each of those sections there are so many entities.

If you take sewers, the city's Department of Environmental Protection is responsible for sewers. They have certain criteria that they have to meet for the state. But they have federal rules they have to abide by as well. I don't think that there's any area where you don't have to consider all levels of government.

One area where the states don't play a very big role is freight transportation, maritime, and aviation. That's pretty much localities and the federal government.

But every area has its unique bureaucratic mess that governs it. Sometimes it works better than other places.

"I can't think of an example of a weak spot in our infrastructure. But my guess is without investment now there will be some things that will be creaking and breaking down soon."

Calvin Johnson: Did you talk to them all in your research, or was the New York Public Library really the primary governmental body you dealt with?

Kate Ascher: Talking to knowledgeable people really helped. I had a researcher who is not here tonight, but who did most of the research.

It's amazing how much information there is over the Internet that wasn't before, and also how much information you can get from people. [You can really learn a lot] if you find someone at the MTA who is willing to help you – which is a very hard thing to do. Same with Con Ed; those are two examples of organizations that are perhaps less helpful. The city agencies themselves are very proud of what they do.

Most people were very forthcoming with information that wasn't going to create a security threat. Ten years ago probably no one would think twice if you wanted to look at what the Holland Tunnel looked like, or if you wanted a map of the steam system. Today however, you have to dig to find it.

WHY NEW YORKERS CARE ABOUT INFRASTRUCTURE

Jim Matthews: What did you find most interesting or most surprising in putting this book together?

Kate Ascher: A lot of people have asked me that, and there wasn't just one single part of the infrastructure system that I didn't know about. I have been impressed with how farsighted the original infrastructure planners were. It doesn't matter if it's water, sewer, power, roads. The whole street grid for Manhattan was put together in 1811. It's pretty amazing that it has held up as well as it has.

But the thing that has been most surprising to me is how many people actually care about this stuff. I wrote this book because it was in my head and I wanted to do it. It's a world I lived in for several years, but it's really kind of niche stuff. It's actually been totally shocking to me – and surprising to the publisher – how many people are genuinely interested in this stuff.

I got a call from someone from the City Section of the New York Times asking me to write an article about why people in New York are so interested in infrastructure. I told her, honestly I don't know. I couldn't answer the question. She was perfectly convinced that more than in other cities people were fascinated with this stuff. That's what surprised me.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • •

ANSWERS:

1. c) About 2,400 of the 3,200 crosswalk buttons in the city no longer work

2. d) 100,000 miles

3. c) 12 percent of the nation's freight comes through New York's port, making it the country's third largest by tonnage

4. c) The third water tunnel is slated to be finished around 2020

5. a) New York used slightly less energy than Austria, and a bit more than Portugal or Chile.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Â

Blacklisting Tenants

When Adam White withheld rent from his landlord in 1996 for failing repeatedly to repair a serious leak in his ceiling, he was doing what he knew New York tenants have the right to do when landlords fail to make vital repairs. The landlord started eviction proceedings against him, but they settled the dispute quickly -- White agreed to pay the rent and the landlord agreed to make the repairs and give him a small rent abatement -- and the housing court case was officially dismissed. But the case was far from over. Because of it, White was blacklisted.

He did not realize this until six years later, when he was looking to move. A prospective landlord denied his application, because the nation’s largest tenant screening company, First American Registry (since renamed First Advantage Safe Rent), had provided a report on White that said only that he once had been sued for non-payment of rent – without indicating that the landlord had acknowledged White’s legitimate basis for withholding the rent.

White sued, on behalf of all tenants similarly wronged.

This month, the company reached a tentative settlement in the class action lawsuit, White et al versus First American Registry, Inc., by agreeing to pay almost two million dollars to as many as 35,000 tenants who had a case in housing court that appeared in tenant screening reports produced by the company. The settlement was filed on February 3 for review and approval by the federal court.

The settlement points to a significant problem for tenants who are sued by their landlords in housing court -- getting labeled as troublemakers and becoming blacklisted, which effectively prevents them renting apartments in the future.

“Blacklisting I think is the most important issue facing tenants today,” said James B. Fishman of Fishman & Neil, LLP, one of the attorneys who filed the suit on behalf of the class. “It has a substantial chilling effect on tenants being able to enforce their rights.”

Tenant Screening

Talk to New York City landlords, and many will tell you that they have to screen tenants.

“Owners need to be able to protect themselves,” said Mitch Posilkin, general counsel to the Rent Stabilization Association, a landlords’ trade group. “They need to know who they are letting into their buildings. It not only affects them, it affects other tenants in the building. Once a tenant comes into your building, it is extremely difficult to evict that tenant. Owners have to be extremely vigilant.”

As many as a dozen companies provide such tenant screening services to landlords.

One of the things these companies do is check the records of New York City Housing Court.

The problem, as tenant advocates see it, is that many of the 300,000 cases filed in housing court every year, most of them non-payment cases, are withdrawn or discontinued. Sometimes, the landlord discovers that the case was filed in error –- that the rent already had been paid. In other cases, tenants have valid reasons for not paying the rent, as in White’s case when landlords fail to repair their apartments or provide required services like heat and hot water. And in other cases, advocates allege, landlords bring baseless eviction cases as a means of harassing rent-regulated tenants into leaving.

Court Records In A Digital Age

The tenant screening companies buy the case records from housing court. The court defends the practice. The records, it says, are public information.

“We have no discretion about giving out the information,” said David Bookstaver of the Office of Court Administration. “Under the law they’re entitled to it. Under the law we’re entitled to sell it. So if we didn’t sell it, it wouldn’t stop the information from being obtained.”

But James Fishman said the court was going too far in the way it provides the information to the tenant screening agencies.

“The law only says the court has to make court records available at the clerk’s office one file at a time,” he said. “What the court is doing here is selling in an electronic form a mass quantity of information all at once.” Fishman believes “the court system should not be selling this data. You would put these tenant screening companies out of business if the source of information dried up.”

The Settlement

If the court approves the settlement, First American Registry will significantly change the contents of its reports -- they will include the outcomes of the cases. Perhaps more importantly, the company will expunge a case from a screening report if a judge determined that a landlord’s case had no merit or if a landlord agreed that a case was brought by mistake.

“Prior to this they were refusing to delete any case because it was part of the public record,” Fishman said. “Getting those cases expunged gives a large number of tenants the ability to clean their report in a way that did not exist before.”

While the settlement may directly affect how tenant screening companies work, Fishman and other housing advocates said that the blacklisting of tenants simply because they had been to housing court was a problem that had to be addressed at other levels.

“The court system needs to realize that they are turning the housing court into a place that actually does harm, unintended harm, to tenants who simply want to enforce their rights,” Fishman said. “People have been following the advice for years to withhold rent to get repairs. But that advice is harmful. That’s a very significant issue for the court system to deal with. The records are being used to hurt people.”

Housing Court And Credit Card Ratings

Even as the tenant screening company case is all but settled, Fishman said he had noted what may be a more troubling development for tenants: The “big three” credit reporting companies (Experian, Equifax and Trans Union) are including housing court money judgments on people’s credit reports.

A spokesman for TransUnion said in an email that including the information on credit reports was not a new practice, as far as he knew, and that under law the company could include money judgments from housing court. A spokeswoman for Experian did not return a call for comment.

“It’s ominous because of the reasons why judgments occur in housing court,” Fishman said. “Most judgments happen because a tenant who does not have an attorney gets browbeaten in the hallway by a landlord’s lawyer into agreeing to a settlement. What they’re not told is that that judgment is going to show up on their credit report and have a substantial impact on their credit score.”

Credit reports and tenant screening reports are different. A person’s credit report includes information on credit accounts and debts -- any money judgment against the person in any civil court proceeding could conceivably end up on her credit report. Tenant screening reports, like First American Registry’s, however, focus on eviction cases in housing court.

Changes in housing court have made this development troubling for tenants, advocates said. In the past, tenants in housing court were generally given time to pay back rent when they first appeared at housing court; no official judgment was entered against them unless they failed to pay the debt within some agreed upon time.

But now, almost every settlement that tenants negotiate with their landlord’s attorneys in the hallways of housing court include “final judgments” on a first appearance, with a warrant for the person’s eviction issued immediately. The execution of that warrant (that is, the actual eviction by a city marshal) is “stayed” generally for 30 days, which is how much time the person is given to pay up.

This technical change has resulted in more landlord-tenant disputes being reflected in credit ratings. But Niles Wellikson, an attorney whose firm, Horing Wellikson and Rosen, P.C., represents landlords at housing court, does not think this is necessarily unfair to tenants.

“There’s no right to not pay your landlord and not have that come up on your credit,” he said. “The tenant advocates are saying this shouldn’t affect your credit. That’s like saying it’s OK not to pay your landlord. And I don’t agree with that.”

The issue of court's selling court record data for commercial purpose is a new problem as the Internet and computer technology make access to this data cheap and instantaneous. The ramifications are huge, affecting many aspects of people’s lives, as their dealings with the court system, from divorces to evictions to traffic tickets, become accessible to all for a small fee.

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â

Space Woes

To understand why artist Andrea Zittel moved to New York City –- and also why she, like so many others, left -- it helps to look at her art projects. For one, she lived in a small basement room for a week without sunlight, a clock or a calendar; “I wanted to see if my day-to-day activities would completely fall apart.” She also lived for a month in one of her “Cellular Compartment Units” (which are not much bigger than a jail cell), and she has designed and constructed even smaller “Homestead Units” (the size of a kitchen) and “Living Units”(the size of a closet) and “Escape Vehicles” (the size of a car trunk) that she likes to call “intimate universes,” though others might see them as "cramped spaces."

To understand why artist Andrea Zittel moved to New York City –- and also why she, like so many others, left -- it helps to look at her art projects. For one, she lived in a small basement room for a week without sunlight, a clock or a calendar; “I wanted to see if my day-to-day activities would completely fall apart.” She also lived for a month in one of her “Cellular Compartment Units” (which are not much bigger than a jail cell), and she has designed and constructed even smaller “Homestead Units” (the size of a kitchen) and “Living Units”(the size of a closet) and “Escape Vehicles” (the size of a car trunk) that she likes to call “intimate universes,” though others might see them as "cramped spaces."

So she did not mind that her first apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, when she moved to New York in 1990, was just 200 square feet, bigger than most of the universes that the city would help inspire her to create.

"I prefer small spaces," she told me the other day at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, where her work is on display in an exhibition that opened this month entitled "Critical Space."

There is nowhere where space is more critical than in New York City, and arguably no New Yorkers who struggle more for enough of it than the city's artists.

Fleeing For Space

“Space is the number one issue,” Robin Keegan testified last month in the third hearing by the New York City Council’s committee on cultural affairs into the problems facing the city’s cultural community. Keegan is one of the authors of Creative New York, a report (in pdf format) released in December by the Center for an Urban Future that examines the strengths and challenges of what it calls the "creative core" of New York. "In New York, complaints about high real-estate costs and too little space are hardly unique," the report concedes. But the space problems of artists and arts groups –- space for living, for working, and for presenting their art -- are "particularly acute.” For example, “the high cost and scarcity of studio time for musicians and visual artists, and rehearsal space for performing artists, regularly requires them to make heroic efforts to pursue their art in the city.”

Many have been giving up trying to be heroes. “Most artists are driven out of New York because they can’t afford space,” Andrea Zittel said.

She herself certainly still has a presence in the city -- besides her current exhibition at the New Museum and another one beginning February 9th at the Whitney, her art work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and in Central Park, where her “Deserted Islands,” about the size of bean bag chairs, were placed in the Central Park Pond. She also owns a three-story building in Williamsburg, which she bought once her art career had begun to take off, where she lived, worked, and presented her art in storefront exhibits on the ground floor.

But she left New York City five years ago for California, and visits only a few times a year; the ground floor of her building is now a cafĂ©. In a recent article about her in New York Magazine entitled “The Non-Manhattan Project: Andrea Zittel bolted New York for the California scrub…”, she is quoted as saying: “I wanted to show that there could be a viable arts community outside a cultural capital like New York or Los Angeles, somewhere more affordable.”

Artists quoted in the Creative New York report seem to be fleeing New York not because they want to prove anything, but because they feel they have no choice. Hope Forstenzer, a graphic designer and glass blower, moved to Seattle. “I love New York,” she told the authors. “But I couldn’t change my life in any way to make it more secure.” At the time he talked to the authors, sculptor and copy editor Doug Culhane had definitely had it with New York City: After living in the same building in Williamsburg for 12 years, he was being evicted by his landlord, along with 11 other artists who live in the building -- even though the presence of such artists helped revitalize the neighborhood in the first place. Culhane had decided to leave the city altogether, and was trying to choose among Hudson, New York, Providence, Rhode Island and several other destinations. “Cities everywhere want artists,” Culhane said, “and are making room for them.”

“Even cities like Paducah, Kentucky are developing tax incentives and affordable housing to retain and attract creative talent,” Robin Keegan testified. “And whose talent do they want most? Ours.”

Scrambling For Space

Nearly every day there seems to be an arts story in the papers that is as much a story about real estate. Two hit Off-Broadway shows can't find a Broadway theater to move to. The Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue announced this month that it will be turned into a venue for the performing arts, which worries the art and antique dealers who have been holding their fairs there. The Department of Education sent a letter evicting the Boys Choir Of Harlem from the public school where it has operated rent-free since 1993.

The one mention of art or culture in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s State of the City address -- delivered at Snug Harbor Cultural Center in Staten Island -- was, in a way, all about space. After boasting of having "dramatically increased capital funding for arts organizations in every borough," he continued: “This year, the 30th Anniversary of our city’s Department of Cultural Affairs, we will help unveil a number of exciting projects, including a new performing arts center at Harlem’s Aaron Davis Hall, and a beautiful new wing at the Bronx Museum of the Arts. And -– I know this will be a favorite with many here today -– the Staten Island Zoo will open its long-awaited Reptile Wing!”

If many arts institutions are looking to expand -- most art museums, for example, have enough exhibition space to show only one or two percent of their collection -- less-established arts groups and individual artists feel increasingly desperate about getting enough space just to meet their basic needs.

Artists “are losing hope and growing bitter about not being able to live and work and stay here,” testified Ted Berger, retiring director of the New York Foundation for the Arts.

Offering Space

Cultural Affairs Commissioner Kate Levin acknowledges the problem, and (during the second hearing of the city council committee in October) enumerated some of the ways the city government is trying to do something about it, such as creating a new cultural district in downtown Brooklyn "that will include rehearsal and performance spaces at affordable rates," and transfering ownership of a half-dozen city-owned properties on East Fourth Street "to the cultural tenants that have occupied them for years, including Ellen Stewart's La Mama Experimental Theater Company."

Several non-profit organizations also have stepped up to help.

NYC Performance Arts Spaces helps artists find rehearsal and performance space, with searchable online databases for musicians and for dancers, and one soon for theater performers and also authors looking for a place to give readings. (The average rate for a rehearsal space these days, according to program administrator David Johnston, is $20 an hour.)

Swing Space, a project of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, convinces owners of buildings below Canal Street to make available temporarily vacant space for free or at low cost. Currently, according to cultural council president Tom Healey, 140 artists have free use of some 80,000 square feet of “vacant storefronts, storage units, office floors and lofts.”

Workshop space is often available through artist residencies, such as those offered by the New York State Artist Workspace Consortium, a group of ten art institutions (five of them in the city, from Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City to the Lower East Side Printshop). Brooklyn installation artist Kim Mayhorn has been accepted to some half dozen artist residencies, most (but not all) offering workspace as part of the deal, including one at the Whitney Museum and a residency lasting two months in Utica, New York at Sculpture Space. “My brain tends to work on a very large canvas,” she said, “but I can’t afford to rent an art studio of the size that I would need for my work, unless I also moved to a cheaper apartment, which would have to be the size of a box.” The residencies, she said, “allowed me to have more space to think, and to create.”

There is even affordable housing specifically geared for artists. Some of it is famous, such as Westbeth, a century-old factory building in Greenwich Village which four decades ago was converted into what it claims is “the largest artists community in the world,” and the Manhattan Plaza on 42nd Street. Less well-known is the Aurora, developed by the Actors’ Fund, which also has been offering monthly seminars on finding affordable housing. The Fund is just about to construct new artist housing as well, Schermerhorn House in downtown Brooklyn, in a joint project with Common Ground. And they are not alone: Artspace, which bills itself as “America’s leading non-profit real estate developer for the arts,” is engaging in its first foray into New York City, a joint project with a local community group, El Barrio Operation Fight Back to create 65 affordable apartments for artists and their families in the building that once housed P.S. 109 on Third Avenue and 99th Street.

Nobody is pretending that any of this is enough.

“Many of these projects are becoming less and less replicable," Keegan said, "due to the continued escalation of real estate costs across the five boroughs."

Suggested Solutions

At the city council hearing in December, Norma Munn, of the New York City Arts Coalition, suggested three ways that the city government could help solve the problem, ideas that have the backing of many arts advocates in the city. One, which she called an interim solution, would be for the city to provide a package of tax incentives that would encourage landlords to rent to non-profit arts groups and to individual artists; and that would encourage developers to set aside part of their new building for an art group or individual artists.

Longer term, Munn suggested the establishment of a “citywide community cultural land trust” – basically, a not-for-profit real estate development corporation that would buy, renovate and resell buildings but restrict their use in perpetuity to something art-related, such as artist workspaces.

Munn also recommended that the city use its planning and zoning in a way that is more attentive to the real cultural needs of the city. “Right now the City Planning commission’s idea of planning for culture is to block off an area in a master plan and say cultural center,” Munn testified. The planners, she said, give no thought to what that center will actually be -- “It’s just a blob” – and as a result, it rarely happens.

Indeed, planning sometimes does as much harm as good. Ironically, the recent rezoning of Williamsburg and Greenpoint to create new affordable housing there has increased the price of real estate in these two arts-heavy neighborhoods to the point of threatening to drive out many arts groups.

A Room Of One's Own

"A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction," Virginia Woolf famously wrote . She understood why there could be no great female artist in Shakespeare's time: "One has only to think of the Elizabethan tombstones with all those children kneeling with clasped hands; and their early deaths; and to see their houses with their dark, cramped rooms, to realize that no woman could have written poetry then."

T.J. Volonis has a room of his own -- or almost his own; it's a room in a brownstone, without enough space for a bathroom, which is out in the hall and which he shares with the other tenant on the floor. Volonis does "functional art," sculpture-like chairs and tables, one of which sold at an art auction for $1,300, but he's having trouble doing it where he lives. "I've been looking for a new space so I can do my work. I'm tripping over my sculptures. It makes it difficult to produce more pieces."

On the other hand, he admits he is not one of those frustrated New York artists. It is hard to be frustrated after only a few months. Volonis, who moved to the city after graduating from college in 1999, did not make his first piece until last August, the one that sold in November. "If I had moved anywhere else," he says, "I don't think I would be producing art." Space isn't everything.

Related Articles

Is New York The Cultural Capital Of the World?

Space Wars

BAM And Its Cultural District

The Plans For Downtown Brooklyn Ignore Both People And Public Spaces

Fighting Over Outdoor Space

Industries That Got Away (some for lack of space)

Â

Portraits of Rebuilding

Several weeks after Governor George Pataki, in his State of the State address, spoke with pride about how New York had "established and met an aggressive timetable" for the rebuilding of lower Manhattan, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, in his State of the City address last week, spoke of his impatience at the slow pace of rebuilding: "We need this now!"

This is not all they see differently. Pataki has stuck by the idea of shoring up the area's status as an international finance center by replacing all the office space lost on 9/11 at Ground Zero. Bloomberg believes that the market for so much office space no longer exists, and that there should be retail stores, residential buildings, and hotels added to the mix to make Lower Manhattan an around-the-clock neighborhood.

Pataki in his speech credited the success he sees in rebuilding to the spirit of "true New Yorkers" who "dared to transcend the challenges before us"; Bloomberg, however, in his speech seemed to blame what he describes as the failure of the process on a single person: Larry Silverstein.

"We need to push aside individual financial interests and focus on what's best for our city," he said, calling for Larry Silverstein to give up his right to develop the entire site so that it can be built up more quickly.

It is not the first time that egos have clashed over Ground Zero. Indeed, it is possible to view the entire rebuilding process as a shifting parade of personalities. Individuals were symbols from the moment of the terrorist attack on September 11th, 2001, when the public was shown "portraits of grief" of each victim, and the world saw the rescue workers as heroes. The people who are now at center stage are those charged with rebuilding the World Trade Center site, and to many New Yorkers, they, too, have become symbols -- symbols of the stagnation, confusion and conflict in the rebuilding process.

Pataki will leave office by the end of 2006. Bloomberg, who hasn't had a large role in rebuilding, now has declared a commitment to getting more involved. The balance of power downtown seems to be changing, and not just at the top. A slew of new board members have been appointed to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and some new architects have been brought aboard. As these newcomers arrive, some of the old hands are either fading away -– or storming off.

Those involved in Ground Zero have conflicting short-term priorities, differing long-term visions, and distinct avenues of power available to them to accomplish their goals. How they interact will make a major difference in what happens over the next year, and what Ground Zero looks like years from now.

GOVERNOR GEORGE PATAKI…

|

Governor George Pataki has been in charge of development at Ground Zero for four years. He has until the end of 2006 to leave his mark on the site. |

For the last four years, Governor George Pataki has held formal control over the rebuilding process, and has chosen to associate himself closely with what is happening at Ground Zero. As a result, many blame the governor for the lack of progress.

But Pataki wrapped up his State of the State speech by celebrating what gains have been made.

For good news, Pataki first looked beyond the site, noting that $10 billion worth of construction is underway nearby. By the governor's account, 75 large companies and thousands of smaller ones are moving downtown, or staying there. Perhaps most significant is Goldman Saks, which has committed to building its headquarters directly across from Ground Zero, after backing away from the idea last fall.

But Pataki's main focus has been on rebuilding the site of the World Trade Center itself.

…And the Architects

|

VETERANS

Peter Walker and Michael Arad worked together to design the memorial, which still has major fundraising issues to overcome.

|

Since the Twin Towers were destroyed in 2001, world famous architects have flocked to the site. But most of their projects have been bogged down. Almost two years after the ceremonial start of construction, it is hard to find evidence of much actual building. Of all the big plans, only 7 World Trade Center has made progress significant enough to be noticed by the untrained eye.

Daniel Libeskind was selected to become the master planner in a high profile international design competition, but lost his bid to design the Freedom Tower. Since then, his master plan has seemed to become ever less central to the site's actual development. Today, the guidelines that he was supposed to develop for architects building towers on the site have yet to be put in place, threatening to marginalize his concept for the site permanently.

David Childs has the distinction of being the one architect to design a building that has been built at Ground Zero -– 7 World Trade Center. But he too has run into problems. His design for Freedom Tower was declared unsafe by the New York Police Department, and the building was redesigned to sit on top of a windowless, concrete block ten stories high.

The only part of the rebuilding project that has gone smoothly is the transportation hub. Its architect, Santiago Calatrava, has been working with the Port Authority, and his plan is quietly moving ahead on schedule.

The memorial has caused considerable controversy, but so far has avoided a drastic redesign. It is not without problems, however, the most immediate being funding. The World Trade Center Memorial Foundation is in charge of a $500 million fundraising campaign, and is scheduled to take over responsibility for the memorial from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation once it moves from the planning stages to construction.

That does not mean the memorial is a done deal, though. While it has yet to undergo a major rethinking, experiences with the Freedom Tower and, even more drastically, the planned cultural center, show how quickly things downtown can change.

NEWCOMERS:

|

|

… And Culture and the 9/11 Families

|

|

The original plan for Ground Zero placed a heavy emphasis on cultural development. Then Debra Burlingame, whose brother was the pilot of the plane that crashed into the Pentagon on 9/11, wrote an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal last June objecting to what she saw as the inappropriate political message being promoted on the site. The article inspired others who felt the same way to mount a campaign against the International Freedom Center and the Drawing Center, the arts institutions that the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation had invited to move to Ground Zero.

Responding to such pressure, Pataki effectively forced the two institutions from the site last fall. This brought into question whether culture will continue to be a part of the project. The planned cultural center has been redesigned. It is now to take up less than a third of its original size, and is being described as a visitors' orientation center.

This change has earned the governor some harsh criticism.

“The promise of culture at ground zero was in many ways the boldest part of the master plan for the site," wrote Eleanor Randolph and Verlyn Klinkenborg of the New York Times editorial board. "It took courage to propose it, and it would have taken courage to sustain it. Instead we have watched that courage drain away over the past year."

… And the Next Governor

Many are beginning to wonder what Eliot Spitzer – or whoever the next governor will be – wants from Ground Zero. Many are beginning to wonder what Eliot Spitzer – or whoever the next governor will be – wants from Ground Zero. |

Governor Pataki's is planning to run for president in 2008, and lack of visible progress would be an enormous political liability. There is the widespread expectation that he will put a high priority on getting tangible progress started on both the Freedom Tower and the memorial. But some fear that the governor, feeling the need to get something – anything – built by the time he leaves office, will make damaging sacrifices in the name of speed.

But some are already looking ahead to Ground Zero post-Pataki. The New York Post has already fired the first shot across the bow of the man many see as the frontrunner to become governor next year, state Attorney General Eliot Spitzer. Steve Cuozzo criticizes Spitzer for his public spat with Lower Manhattan Development Corporation chairman John Whitehead. "The harm he's done to replacing the World Trade Center" by picking a fight with Whitehead, writes Cuozzo, "is incalculable."

For his part, Spitzer has said little about his ideas for lower Manhattan. But as the end of Pataki's term nears, it is something more and more people seem interested in.

"Certainly you hear more and more people saying 'what does Eliot want from Ground Zero?'" said David Kallick of the Fiscal Policy Institute.

MAYOR MICHAEL BLOOMBERG …

|

Mayor Michael Bloomberg wants a bigger role in the rebuilding at Ground Zero, and his ideas differ from those of the governor.. |

While Pataki has been held accountable for the lackluster development at Ground Zero to date, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has been criticized for not getting more involved. But Bloomberg's approach is changing, and as it does it is becoming clear that the mayor sees Ground Zero differently than the governor. While Pataki has focused his attention on the large-scale and the iconic, Bloomberg seems more interested in what happens at the street level and what the smaller towers planned for the site are used for.

… And the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation

|

THE MAYOR'S APPOINTEES:

|

In the last year, several members of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation have left, leaving Mayor Bloomberg and Governor Pataki with open spaces to fill.

Bloomberg did so immediately after his reelection. The mayor appointed four members of his administration and two business leaders, while the governor appointed two high level state officials.

|

THE GOVERNOR'S APPOINTEES:

|

Bloomberg's appointments were "a political change of the highest order," said Ric Bell, head of the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects,

At the same time, however, Mayor Bloomberg questioned whether the corporation really makes a difference. This is a view that has been expressed at times from everyone from the governor to the civic groups involved in the redevelopment of lower Manhattan. The board has not been able to gain much independence from Governor Pataki, and has been shot down on the few occasions it has tried. Further, the corporation's power seems likely to decrease as time goes on.