Rent Regulation and The Division Of Housing and Community Renewal

For many New Yorkers, the words “rent regulation" immediately conjure up the boisterous annual deliberations of the Rent Guidelines Board. The board's deliberations this year, now ongoing, promise to be more boisterous than last year, when political pressure from the mayor's office kept the board from giving landlords a huge spike in rents on the almost one million rent-stabilized apartments in the city.

The board's June 19 hearing, which will take place for the first time in the Bronx, could be the most intense yet. Tenant organizers are working to bring out as many tenants as possible in the borough that has the highest number of tenants hauled to court for non-payment of rent.

The rent spike this year could set a record. Its public members, appointed by the mayor, largely determine the final outcome of the board's deliberations. It does not bode well for tenants that last month the mayor dumped the one public member, Martin Zelnick, an architect, who showed the greatest concern for tenants in recent years.

The board's annual deliberations, however, are just one piece of the rent regulation system, albeit the piece that generally gets the most attention. Of equal or greater significance is the work of the state's Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR), the agency charged with enforcing the laws that apply to rent-regulated apartments.

Some tenant advocates are hopeful that with the election of a new governor next year, the state agency would do a better job of protecting tenant rights. Critics charge that the agency has gotten so bad under Governor George Pataki that the Emergency Tenant Protection Act, which the agency enforces, should be renamed the Emergency Landlord Protection Act.

The Division of Housing and Community Renewal is also the state's main housing development agency and its efforts on that front, too, have drawn complaints from housing advocates.

The agency is adamant in its own defense, releasing a statement that said in part: "This agency has a very strong and distinguished record supporting affordable housing and tenants' rights across this state, and we take that role very seriously."

Pro-Landlord Or Pro-Common Sense?

State Senator Liz Krueger is one of those who is disappointed in the agency’s performance. "It's not a surprise that people have a high frustration level" with the state's housing agency, Krueger said. "Dramatic problems have been growing in DHCR over the years. Some of their interpretations [of housing laws] raise red flags."

Tenant advocates charge that on virtually every type of complaint tenants can file and every type of request to increase rents landlords can file, the agency comes out on the side of landlords.

Take the case of "preferential rents." Wherever landlords have trouble renting apartments or where they have sought to keep a tenant, landlords have offered to rent apartments for less than the rent registered with the agency. For years, the agency considered preferential rents the base rent for that tenant. But following a change in the law in 2003, when a lease renews on a rent stabilized apartment, the landlord can now charge an increase based on the (higher) legal registered rent. The agency's interpretation of this change show its favoritism,say some critics.

"Even when the lease says the preferential rent will last the length of the tenancy, (DHCR) is ignoring it and allowing landlords to charge the legal registered rent upon renewal," said Kenny Schaeffer of the Met Council on Housing. "It's a terrible idea" for tenants to complain to DHCR about preferential rents, he added. Instead, they should seek to address the matter at housing court, he said.

The decisions on preferential rents are not unfair, replied Mitch Posilkin, general counsel of the Rent Stabilization Association, a trade group that represents property owners across the city.

"We think it's common sense," Posilkin said. "When a landlord is willing to accept less, and then at some point down the road the landlord says he wants to collect what he's allowed to collect, tenants view that as the end of the world."

Major Capital Improvements

Tenant advocates said another example of pro-landlord bias is Major Capital Improvements. Landlords who make big repairs or improvements to their buildings - say, installing a new boiler or replacing the elevator - can pass along the costs of such improvements to tenants. These costs are added to tenants' rents -- permanently. Landlords who make such improvements will get reimbursed for much more than the actual cost of the work.

Over the years, the state agency has decided that costs associated with MCIs can also be passed along. These "enhanced MCIs" stretch the rules, said Bob Katz, general counsel to the Queens League of United Tenants.

"They included the costs of pruning trees and seeding lawns -- in order to put in a boiler," Katz said of one MCI request made by a Queens landlord.

Pushing Towards Deregulation Or Toward More Evenhandedness?

Advocates believe that one motivation pushes every request landlords make to increase rents: Deregulating rent stabilized apartments.

"All of this happens because landlords want to deregulate apartments," said Katz, who added that he overheard a state official telling landlords’ attorneys ten years ago that by the time Governor Pataki is out of office, “most of the apartments will be deregulated.”

"It's coming to pass. They're going down very, very quickly."

Others agreed that deregulation of rent regulated apartments - which can occur when a rent reaches $2,000 and becomes vacant - is the force pushing interpretations favoring landlords on MCIs, among other examples.

"Since George Pataki has been governor, there has been a shift toward landlords in the state legislature, the appellate courts and the housing court," said Sam Himmelstein, a tenant attorney.

But landlords see the agency as finally emerging from years of bias toward tenants.

"There's no question that historically DHCR was notoriously biased in favor of tenants," said Posilkin of the Rent Stabilization Association. "We would view it as a more evenhanded organization today. In the past, there were two possible results: no determination, where the case would languish, or a ruling against the owner."

Whether it is "evenhandedness" or "pro-landlord bias," the state housing agency's interpretations can be traced to its leadership, which changed significantly when George Pataki became governor, said Michael McKee of the Tenants Political Action Committee.

"As soon as Pataki was elected, he brought in top people from the real estate industry and turned the office of rent administration over to them," McKee said. An attorney who represented slumlords in Harlem, Marcia Hirsch, became the agency's general counsel, McKee said.

A former employee who worked at the agency for over 15 years agreed.

"Four or five people were hired to run the show," explained the former employee, who requested anonymity because he says he is still in the field and fears retaliation. "They basically swung the agency 180 degrees. (Agency staff) just assumed the top people wanted it interpreted in a pro-landlord way and they would, on their own, issue orders in favor of the landlords.

"Most of the people who were hired had worked as landlord representatives before. That certainly was a total change under Pataki."

And the agency came under pressure from attorneys representing landlords with cases before the agency, the former employee charged.

"There were certain landlords' attorneys who knew these few key people in the agency and could find a way to get a ruling in favor of their clients," the former employee said. "Eventually the exceptions they created would swallow the rule.... I think that went on a lot and probably still goes on to some extent."

The agency denied that allegation.

"These assertions are obviously the work of an unidentified former and disgruntled state employee," the agency said in a statement. "And we cannot say in stronger terms that the charges are false, inflammatory and wholly without merit or truth."

A Change In The Next Adminstration?

Would a Spitzer administration hire people to make the agency over? Housing advocates are not counting on it.

"My fear is that Mr. Spitzer comes from real estate money," said Himmelstein. "His father's a big landlord in New York.... He's been very good at going after Wall Street, but I bet you can't name one real estate person he's gone after."

"I am not aware of the attorney general's position on any of these issues," Posilkin said.

Spitzer could help everyone if he were to indicate more clearly how he views critical housing issues, McKee said.

"We don't know if Eliot Spitzer is going to be pro-rent regulation," he said. "He's carefully avoiding any mention of it. We've asked him. He hasn't said a word about being in favor of rent regulation, repealing home rule, or repealing high-rent decontrol.”

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â

Greenpoint Waterfront Fire

People fighting for the character of Brooklyn's waterfront see a tragedy -- and suspect a crime -- in the spectacular fire that engulfed 15 abandoned industrial buildings on Greenpoint's waterfront May 2. "I'm in a state of mourning over the loss in Greenpoint," says industrial archeologist Mary Habstritt.

The buildings were likely to obtain landmark status, she says. The character and history of the industrial waterfront could have been maintained while transforming the site into a residential and business area befitting the burgeoning residential character of Greenpoint.

That isn't what the developer wanted. He planned to raze the old buildings to put up 2.6 million square feet of residential towers, townhouses and retail. The 10-alarm fire that ravaged the 21-acre site and took days to put out will probably make it more convenient, less complicated and less expensive for him to proceed as he had wished.

Suspected Arson

A day after the blaze, the Daily News reported that Fire Commissioner Nicholas Scoppetta immediately suspected arson. A tell-tale sign was that the fire began in the quiet pre-dawn. Another indication of suspicious origin was that many buildings quickly went up in fierce flames, even before the first fire trucks arrived.

Based on her knowledge of construction methods in the past, Mary Habstritt, who is president of the Roebling Chapter of the Society for Industrial Archeology, had additional reasons to see an arsonist's hand. She says that in the 1890s, when some of the buildings on the site went up, there weren't sophisticated methods, as there are today, for preventing and fighting fires. Giant timbers, heavy and dense enough to withstand all but the hottest fire, spanned the floors and were set into holes in the brick walls. If a fire did rage through, the timbers should have fallen out of the walls, leaving the outside structure intact. But in this fire, Habstritt says, walls collapsed.

These buildings had resisted flames for more than a hundred years, says Habstritt. "They were constructed to resist fire. You couldn't get those timbers burning without help."

She dismisses the idea reported in some media that rope left over from the old rope factory was in the buildings and contributed to the flames. She has been inside of one of the old rope factory buildings, and it was completely bare.

A former tenant of one of Guttman's Brooklyn loft buildings, Anne McDonald, also harbored suspicions as soon as she learned of the fire, she says. The Guttman building she had lived in at 247 Water Street in the DUMBO area of Brooklyn (whose troubled history has been recounted in the Village Voice)had burned in 2004. The fire was investigated but evidence as to arson was inconclusive. Four other Brooklyn buildings owned by Guttman have burned since 1991, according to the New York Times, all of them judged as arson.

Guttman, who owns properties all over Brooklyn, Staten Island and Queens, has never faced arson charges. Gotham Gazette's calls for comment to Guttman's home in Lawrence on Long Island and to his Brooklyn real estate office were not returned. His attorneys have told the media that he had nothing to do with the fires. They speculated that squatters or vagrants started the fire. One of his attorneys noted that Guttman did not have property damage insurance on the buildings.

Brooklyn Lofts

Some 20,000 people live in a state of legal limbo in lofts on the waterfront in Brooklyn, says McDonald. In SoHo in the 1980s, when artists moved into the lofts abandoned by light industry in the neighborhood, the legislature legalized residential use by artists. That led to the transformation of the neighborhood. No such legal dispensation aids Brooklyn loft tenants. Not everyone would want the law amended to include Brooklyn. That would lead to an even faster-paced change to the neighborhood with higher rents.

"Usually, the landlord and tenant are complicit" in the illegal residential use of loft spaces, says McDonald. "It's a little bit of a gray zone."

After leaving Guttman's building, McDonald found a new loft space in the East Williamsburg Industrial Park. The landlord there upgraded the property and recently received a certificate of occupancy, allowing residential living.

Landmark Worthy

Residential living in industrial property is the kind of thing that should have happened to the Greenpoint Terminal Market, say preservationists. The Municipal Art Society, a preservation group, had applied for landmark status. At least some of the buildings would have been preserved. There would have been accomodation for new high rises as well.

City Councilmember David Yassky supported landmarking of the buildings, which were in his district. He's not a knee-jerk preservationist. He favored substantial changes to the Austin-Nichols warehouse last year, even though the Landmarks Commission recommended landmarking the building. He persuaded the City Council to support the changes. The mayor supported landmarking, but the council overrode his veto. (Read my article on this, Old Industrial Buildings on the East River)

Habstritt and other preservationists see the loss of irreplaceable landmarks that convey the vital hurly burly of New York's industrial past. The value of the Greenpoint Terminal Market was in unique features, such as the dramatic bridges from building to building over West Street. There was the historical value, too. The buildings once held the largest rope and twine factory in the world. The waterfront location was practical. Materials to make rope came from imported materials unloaded from ships right by the factory. The place showed how it was the working waterways that made it possible for New York to become the great city it is. "We were really convinced that we were on the way to saving it," says Habstritt.

Â

Jane Jacobs and New York

Jane Jacobs left New York City in 1968 and went into self-imposed exile in Canada. Yet when she died April 25 at the age of 89 in Toronto, she was remembered as one of the greatest advocates of New York City’s urbanism. While the rest of the country thought of New York as too densely developed, overcrowded, and dangerous, Jane Jacobs wrote passionately about how its density and diversity made the city livable and exciting.

In a nation that was mostly rural in 1898 when the City of New York was created, the American Dream was small town America and the big city was its nightmare. Jane Jacobs helped retire the myths of the big city.

Jacobs didn’t just wake up one morning in 1961 and write her classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities – today, required reading for architects, urban planners and everyone who study cities. Her ideas arose from her lived experience on Hudson Street, in Manhattan’s West Village, and from her years of active struggle to protect her neighborhood from the city’s grandiose urban renewal plans. A nemesis of Robert Moses, the city’s development czar, she saw the city’s planners call lively human-scale neighborhoods “slums” and “blighted,” then bulldoze them. They were replaced by dull high rises set in wide-open wastelands without a street life – the modernist model of the “tower in the park.” She fought and helped kill the Lower Manhattan Expressway and an urban renewal plan for her own neighborhood. Her book, released in 1961, resonated with the thousands of activists who were fighting battles against urban renewal, highways that cut through the hearts of cities, and grandiose megaprojects. Thus, her brilliant insights are best understood in their historical context, as contributions to the struggles to save neighborhoods from orthodox urban planning.

Jacobs saw incredible richness and diversity in neighborhoods that development-hungry planners disqualified as chaotic and dysfunctional. Of course, she had no financial stake in seeing her neighborhood leveled, and perhaps because of that there was a fundamental difference in the way she perceived the city. Cities aren’t just physical forms but rich landscapes for social and economic relations among people. How do people use the streets and sidewalks? How do the people who work in industries, retail customers, tenants and homeowners interact and coexist with one another? By asking these questions she came upon principles of physical planning that were embedded in the built environment. These relations, which at one point she likened to a “symphony,” and not the abstract visions of planners and developers, were for her the starting point for planning.

Jane Jacobs’ remarkable catalog of urban treasures has inspired generations of urban professionals searching for alternatives to the modernistic bombast and monumentalism that created sterile downtowns, isolated public housing, and sprawled suburban enclaves. Her work contributed to the flourishing of the neighborhood preservation movements, and influenced many other progressive New York urbanists including City Planning commissioners from Beverly Moss Spatt in the 1960s to Ron Shiffman in the 1990s, both advocates of decentralized planning involving neighborhoods. Author Roberta Gratz (The Livable City) and William Whyte, founder of Project for Public Spaces, carried forward many of her ideas. Indeed, there aren’t too many professional planners of all stripes who don’t acknowledge in some way her important contributions.

The city’s fiscal crisis in the 1970s and the federal government’s withdrawal of funds for large urban renewal and public works projects created fertile ground for Jacobs’ alternative way of seeing the city. After Robert Moses retired, government austerity left no money for ambitious public projects or for aggressive urban planners that would reincarnate the master builder. With widespread neighborhood abandonment, professionals had to search for ways to improve communities using the resources that were already there. Organizers and activists in community-based organizations, consciously or not, followed Jacobs’ approach of strengthening the human bonds in neighborhoods and building on existing assets. The city’s housing agency created neighborhood preservation programs. The city created a Landmarks Commission in 1965 that would help protect historic buildings and districts. And the City Planning Department later initiated contextual zoning to encourage new development in context with the existing built form. While all of these initiatives have their limitations, and some of them are used mostly to protect exclusive enclaves, they are part of a toolkit of measures that can be used to protect everything valuable in neighborhoods.

One area in which Jacobs’ admonitions have been mostly ignored is in planning for streets and sidewalks. She showed how mixing pedestrians, cars and bicycles and encouraging an active street life was important to livable neighborhoods. The city’s Department of Transportation, however, is mostly dedicated to moving as many vehicles as quickly as possible through streets. For the most part, the same logic applies to sidewalks. Jacobs felt that having many “eyes on the street” contributed to a lively and safe environment. That means encouraging people to move slowly, stop, talk, and “hang out,” and slowing vehicular traffic.

As happens with many great thinkers, Jane Jacobs is cited by real estate developers and planners who interpret her work in ways she might well question. For example, Alexander Garvin, influential urban planner in New York City, was quoted in the April 27 New York Times as saying The Death and Life of Great American Cities, “changed my life.” Yet Garvin’s reputation is as a pragmatic planner who tries to find better ways to accommodate new development, not community preservation. For example, he was the author of the city’s ambitious Olympics 2012 plan that created sports venues sharply disconnected from neighborhoods. Jane Jacobs on many occasions spoke up against such megaprojects in Toronto.

The New Urbanism is a recent trend in urban planning and architecture that proposes re-creating traditional, walkable communities following the model of 19th Century small-town America. But contrary to many of her critics, Jacobs wasn’t a nostalgic looking to idealize the old. The sterile New Urbanist experiments like Seaside and Celebration in Florida are a far cry from the bustling diversity that Jacobs saw in her West Village.

Jane Jacobs was hardly a traditionalist. She was truly a rebel. She dared to look lovingly and with care at her neighborhood. She stood up to the powerful Robert Moses. She criticized racial discrimination in housing and employment (for example, in her book The Economy of Cities, she cites W.E.B. DuBois and goes on to criticize the inadequacy of programs to aid minority contractors). Her family’s opposition to the war in Vietnam drove her to self-exile in Canada. And ever since then she supported progressive planning, and good hearty urban protest, throughout North America. She most recently sent a message of solidarity to community groups in Greenpoint/Williamsburg (Brooklyn) fighting the city’s massive waterfront rezoning project. Jane Jacobs was a true New Yorker.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

Dredging In New York Harbor -- Economy vs. Environment?

When the Queen Mary 2, the largest cruise ship in the world, docked in Brooklyn for a day earlier this month, it marked the official opening of the newest cruise ship facility in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The terminal will create hundreds of new jobs and attract millions of passengers –- and they owe it all to dredging.

The city had spent millions of dollars to dig a deeper channel. They felt they had no choice. As the size of ships have grown, so too has the demand to accommodate them. Indeed, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is the government agency that does the dredging, is in the midst of the largest New York Harbor dredging project since World War II.

But there is another demand growing as well –- that the environment be protected in the process. The latest step in a lawsuit that has been dragging through the courts could lead eventually to an agreement that will prevent further contamination of already-polluted waters. Environmental groups want the Army Corps of Engineers to come up with a meaningful plan to clean up as well as dredge. The corps responds that they are doing just that.

Ever And Ever Deeper

Dredging to make way for seafaring trade has been ongoing for much of the history of the New York Harbor, but in recent years, the pace and depth has picked up, with the dredgers not just scooping out silt and sand but blasting away bedrock as well.

In the 1980s, ships carrying a thousand boxes full of cargo, each of which would fit on the back of a truck, could fit down channels that had been dug to 35 feet deep in New York Harbor. But then the container ships quadrupled in size. The steroidal growth didn't stop with "Panamax" vessels, so called because they were the largest ships that could fit through the Panama Canal.

Shippers started bringing the clothes and cars and computers from around the world through the deeper Suez Canal with even bigger "Post-Panamax" ships. The U.S. Army Corps on Engineers recently finished dredging channels as deep as 45 feet to accommodate them.

As soon as that was done, the corps began planning 50 foot channels that will cost $1.6 billion to make way for gargantuan "Post-Panamax Plus" ships that bring as many as 7,000 to 8,000 containers to the New York and New Jersey terminals.

Polluted Waters

All this dredging is complicated by some terrible contamination of the waterways. A factory up river in New Jersey that manufactured Agent Orange to defoliate jungles during the Vietnam War spilled toxic dioxins into two of the channels between Staten Island and New Jersey, the Kill van Kull and the Arthur Kill.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency is testing levels of pollution and methods of cleanup in the channels. Environmental groups including the Natural Resources Defense Council, NY/NJ Baykeeper and Green Faith charge that the latest dredging operation interferes with the EPA's ability to make accurate assessments and cleanup plans. The groups also doubt the Corps' commitment to cleanup. In fact, they brought a lawsuit in early 2005 to force the Corps to provide a more complete analysis and plan. They asked for an injunction to stall the dredging until the studies could be done.

That is not what they got. In a March 2006 decision, the court imposed no injunction, but the corps did receive a strongly worded directive. U.S. District Court Judge Shira A. Scheindlin found -- as she had in an earlier ruling--that the corps had failed to present plans for an accurate assessment. She sent them back once again to get more and better information.

"The Corps must consider the issues that were inadequately addressed in its final Environmental Assessment, including alternatives to the projects and mitigation measures. The Corps should also take affirmative steps to ensure that its review is objective and made in good faith," Judge Scheindlin wrote(in pdf format).

They have four months to create the new report.

"What we'd like to see happen is that the corps approach this not just as a navigation dredging project, but as an environmental cleanup," says Larry Levine, Natural Resources Defense Council staff attorney. The corps can "use the dredges that are out there to dig up the contaminated sediment in a safe way that achieves the cleanup of the channels rather than stirring stuff up and moving it around the harbor." What they are doing now just uncovers contaminated material and leaves it exposed, he says. "The environment isn't a side consideration that has to be dealt with as a nuisance."

Even though the judge didn't enter an injunction as requested, it feels like victory to Levine. "In a practical matter, they can't go forward with the next stage of the deepening until they get their house in order."

An official for the Army Corps of Engineers seems unfazed by the court, however. "Dredging was not halted," says William Slezak, Chief of Harbor Programs Branch. The corps will use existing information and newly available data from the Environmental Protection Agency to put together additional models for the court. They are not collecting new samples. The consultants who have been hired to do the report are engineers, chemists and biologists, he says.

Slezak feels confident that what the corps is doing is adequate and will actually benefit the environment. He explains that most of the dredged material in their massive operations is free of contamination. Dredged material, including rock from debris created from blasting bedrock, goes into the ocean, creating fishing reefs. He is reassuring about what happens to the polluted sand and silt. Some of the contaminated material can be combined with cement to create a material that is stable and will not leach contaminant. That is used in such projects as capping landfills. High temperatures or washing are ways to deal with the more contaminated materials. Clamshell dredges -— big scoopers that pull sediment from the bottom of the estuary -- usually have open tops, but when there are contaminants, the clamshell is covered so that it doesn't spill materials over the sides. Furthermore, the channels that are being dredged are not in the Superfund site. That's upstream, he says.

Environmental groups are not confident that the corps' plans are adequate or that they are actually committed to cleanup as well as channel digging. "The Army Corps is notoriously bad on environmental issues," says Levine. The environment takes a back seat when it comes to economic considerations. "They're told by Congress, 'Here's a couple billion dollars, go dig these channels."

Politics

While the corps' Slezak says that the environmental concerns are important, he acknowledges that Congress is most interested in the economic benefits of getting more business to the ports. When the container ships began to grow and need deeper channels, Halifax, with its naturally deep bay, tried to line up business. Baltimore was interested, too. The only way to maintain the largest port facility on the East Coast -- the third largest in the nation, which generates 230,000 jobs regionally -— was to deepen the channels.

It doesn't matter which party is in power, Republicans or Democrats, the New York/New Jersey ports get their funding. The expense of Hurricane Katrina affected Corps projects elsewhere in the nation, but not the New York Harbor, says Slezak. Even the environmentalist Larry Levine supports the deep channels for the harbor.

The only issue for everyone concerned with the dredging is whether the Army Corps of Engineers will make the effort to keep contaminants from swirling around and adding to the considerable pollution already there Even Slezak would not eat the fish from these waters. It is not just the dioxins that make the water hazardous. This is a long-term problem generated by years of industrial pollution. It remains to be seen whether the Army Corps of Engineers dredging operations will make it better or worse.

Â

Finding Space for a Million More New Yorkers

Which city in the United States added the largest number of people over the last 15 years? The answer is not Las Vegas. It's not Phoenix. It's not Dallas. It's New York City. New York City added more than 800,000 additional residents since 1990.

And, according to forecasts, this will continue. We expect that probably a million, and perhaps as many as a million and a half, additional residents will come to New York City in the next 25 years.

By then, the whole tri-state region, the already-crowded 31 counties in and around New York City, is expected to grow to 26 million people.

All these people will arrive in an area that is built to capacity in many ways under existing land use plans and regulations. We are already feeling ill effects of dramatic growth. Residents of parts of Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island see every sliver of space in their neighborhoods being developed as pressure builds for taller buildings to house new residents. Our area now has by far the longest commutes in the country. And as some suburban areas pull up the drawbridge, making it very hard to construct multifamily or affordable housing, people who might choose to be in the suburbs are forced to live in the city.

Finding ways to accommodate even more residents will require public education and support. People have to understand that the city and region are going to grow, and it is either going to happen in a thoughtful way or it is in an unthoughtful way, an unplanned way.

Across the country, cities have come to realize they must join in a regional growth strategy that emphasizes public transportation, improving existing urban centers and creating new ones. Many have enlisted political, business and civic leaders as well as ordinary citizens in a dialogue about how to accommodate growth and at the same time respect the needs and fabric of existing communities. It is time for the New York region to embark upon this kind of effort.

WHAT OTHER CITIES HAVE DONE

Chicago provides a good example of how regional planning might work here. Mayor Richard Daley reached out to suburban mayors and built an alliance of elected officials from across the region to work on growth and transportation issues.

A new group, Chicago Metropolis 2020, initiated a regional visioning process. This basically involves harnessing new technologies such as computer mapping and computer generated visual simulations so people in an area can see what the alternative futures for their communities and regions really look like. It also employs electronic town meeting techniques like we used at Listening to the City in 2003 to help shape plans for lower Manhattan.

A new group, Chicago Metropolis 2020, initiated a regional visioning process. This basically involves harnessing new technologies such as computer mapping and computer generated visual simulations so people in an area can see what the alternative futures for their communities and regions really look like. It also employs electronic town meeting techniques like we used at Listening to the City in 2003 to help shape plans for lower Manhattan.

The first step is engaging public officials and citizens to define tangible goals for their region and to set benchmarks to measure their progress. In the second step, residents develop growth scenarios. People are divided into small groups of eight or ten and sit at small tables working with maps. It is a little like playing Sim City. Each group gets chips that represent the number of people and the amount of new development that needs to be accommodated.

Usually, participants start by spreading the people and projects out in very low densities. Half an hour later, they have run out of land. That is when they come back and stack up the chips. It is kind of magical: Citizens reach the conclusion that the only way to grow is by creating a new mix of density in their region and by developing existing and new centers. When they add up the number of cars that would be generated by spread-out development, they conclude that they must have alternatives to single occupancy vehicles.

Every place that has done this has ended up focusing development in new and existing urban centers. Many have concluded that if communities with just 2 percent of the region’s land area welcome development and accept growth, they can accommodate about 80 percent of the projected growth for the entire region.

And so, in Chicago, this exercise produced a set of recommendations about transportation investments and land use changes. The usual wars about where the third airport is going to be and so forth remain – it’s still Chicago after all -- but the participants have reached real consensus about patterns of growth and the investment needed to support major growth in the region.

An even more relevant example is the Los Angeles region. Los Angeles is, if anything, larger and more complex than the New York metropolitan area. The whole area is in one state but, politically, it is thoroughly balkanized.

People from throughout the region spent about two and a half years on the visioning process, and then they spent the last two and a half years working out a way to implement it. They reached consensus on a new regional transportation plan with a network of truck-only toll lanes on major freeways and of high occupancy toll lanes in key corridors. And they have agreed on a set of transportation investments across the region.

They also adopted some land use changes. The city of Ontario, California, which is an older industrial city with an eroding manufacturing base, decided it could accommodate a substantial amount of growth. They agreed to adopt zoning changes to allow for more residents, and the region agreed to make investments around Ontario’s airport and in a new regional downtown that will double the city’s population. When this is done, Ontario will have almost half a million people, a major new employment center and new housing.

Other cities in the region said they could not accept 30 or 40 housing units per acre, but they were willing to see what 20 would look like. And so they ended up with former industrial areas and strips being rezoned for mixed use, mixed income development.

Los Angeles is expected to grow from 18 million to 22 million people over the next 25 years. The New York region is going from 22 million to 26 million, so we need to think about following Los Angeles’ example.

SPACES IN THE CITY

Bensonhurst, Brooklyn

Finding space for all the additional people arriving in New York City will be hard because we have built on the easily developed vacant sites.

Throughout the city, people do not want additional development or additional density.

But there are still plenty of places to develop. The city has begun the process of rezoning in Greenpoint/Williamsburg, the Far West Side and so forth to prepare for additional population and employment growth. We have got a network of what the Regional Plan Association calls regional centers, places like Jamaica, Flushing, downtown Brooklyn and the Bronx Center. All of these have the potential to accommodate some additional development. And in the suburbs, areas such as the Nassau hub and Hicksville could be developed to house more people and jobs.

Queens, which is projected to add about a half million additional residents over the next 25 years, will have to accommodate more growth than any other place in the region. It has a lot of areas along the avenues currently dotted with one-story commercial buildings. Those plots could be recycled and more intensively developed. And we have the potential to expand Long Island Rail Road service in large areas of Queens that do not have subway service. Doing that would create some new development opportunities without adding to congestion.

If we can harness population growth and reinvest in existing and new urban centers we can improve mobility, create better development patterns in the region and heighten the economic prospects for our citizens.

For an example of why we should do this, we can look to Orange County, California. Twenty-five years ago, it was a very conservative place. It said, “We really don’t want a lot of immigrants and â€those people’ coming here.” They adopted a number of “pull up the drawbridge” zoning and housing regulations to prevent multifamily housing. They did not accommodate growth. But growth came anyway. People doubled and tripled and quadrupled up in single-family houses. This caused serious housing safety problems and other dilemma.

So planning for growth is essential. But the city cannot go it alone. Both New York City and its suburbs are in the same boat, and it will take collaborative action to keep as all afloat.

REGIONAL PLANNING IN NEW YORK

We have a number of assets to work with.

Demographic Changes: The baby boomers are aging, their kids are out of the house, and many are deciding to chuck the keys to those suburban houses and move into New York City and or another of the region’s older urban centers. At the same time, crime rates in the city have dropped, making the city a more attractive place to live.

Transportation: Over the last 25 years, we have invested more than $50 billion in the transit system. That has created a safer and more reliable transportation system in the core of the region.

We also have the largest regional rail system in the world. And in many ways the commuter rail system is not as intensively used as its counterparts in London, Tokyo, Paris and other world cities. There are many places where the density of development within walking distance of a station is relatively low. And so we have enormous potential to fill in development around this system.

To promote that, we have several very large transportation projects that are now partially funded, have full funding agreements with the federal government or are expected to get them. These include the East Side access project and the Second Avenue subway. The ARC project, including a new Hudson River tunnel, is coming along just behind them, and the rail link between lower Manhattan and Kennedy airport has partial commitment of state and federal funds and Port Authority funds. None of these projects, however, can fulfill its potential unless we coordinate land use and transportation around them.

Planning: Our area has strong public agencies, as well as regional organization such as the Regional Plan Association and the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This tri-state area also has a track record of successful visioning exercises, such as Listening to New York, at the sub-regional and local level

But there are obstacles as well.

We have one region as far as the business community and commuters are concerned. But unfortunately, King Charles II decided it would be convenient to make the Hudson River the boundary between the province of New York and the province of New Jersey. The province of Connecticut was just 30 miles away. Like plate tectonics, these three places that don’t really like each other rub up closely against each other. To make matters worse, we have 31 counties, and things get really messy when you drop in the political subdivisions: towns, villages, small cities, boroughs, unincorporated areas and so on. We are the most politically balkanized metropolitan region in the country. This makes reaching consensus on the major land use and transportation investment policies and investments a lot more difficult than it would otherwise be.

Flushing, Queens

And then there is history. Robert Wagner was probably the last mayor of New York City to reach out beyond the city’s borders. Through much of the last 25 or 30 years, New York City felt like the region is a zero sum game: If Nassau or the Jersey waterfront grew, city officials thought, it was at the city’s expense.

But that may finally be changing. I think Mayor Michael Bloomberg -- maybe partly because he ran a company that has operations in New York and New Jersey -- understands that we live in a region with an integrated economy. And the city has been doing really well of late, so there is a growing realization that there’s plenty of development and growth to go around. We are not managing decline here, we are managing success -- and that makes it easier to reach across the political boundaries.

As part of this whole regional planning process, we must build a broad base of political support around tough things: Finding the money to pay for the next generation of transportation investments. Making difficult land use decisions. Promoting growth.

Doing this right can produce many benefits. We can conserve the environment, create a mix of housing types and densities, and get the governance and tax reforms to make this work. It is hard to reach consensus around anything in this big messy place that we call home, but we must do it.

Robert Yaro is president of the Regional Plan Association.

Â

Residency Requirements

|

Carpetbagger |

As principal of Brooklyn Tech, one of the city’s largest and most prestigious public high schools, Lee McCaskill had been described as a “polarizing figure...ruling by intimidation.” But what eventually cost him his job was not that – but the fact that he lived in New Jersey.

Earlier this year, the Department of Education learned that, while McCaskill and his family lived in Piscataway, he sent his daughter to a highly regarded New York city public elementary school without paying, as the city requires of those who live outside the five boroughs. Under investigation, McCaskill resigned.

And McCaskill is not alone. In March, after McCaskill lost his job, at least 132 school employees told the Department of Education that they too lived outside the city, sent their kids to public schools and did not pay $5,500 a year tuition. But while some of those educators may gripe about having to pay to send their kids to free city schools, they can take solace in one thing: Unlike most other New York City employees, teachers can live wherever they want. Many city employees are required by law to live in the city itself and thousands more have to live in New York State.

It is apparent why the Department of Education sought to crack down on McCaskill and the other teachers. In essence, they cheated the city out of money as their children occupied seats -– usually in highly regarded schools -– that could go to bona fide New York City residents. But, in general, does it matter where a public employee or elected official lives?

NEW YORK’S POLICY: EXCEPTIONS RULE

|

Today, about 80 percent of all people who work for the New York City government live within the five boroughs, but this is far more than are legally required to do so. New York has a patchwork of laws and attitudes on residency requirements. While city residents voted overwhelmingly in 2000 for a senator who had lived and voted in Illinois and Arkansas, but never New York, the municipal government requires that a receptionist in the planning department live within the five boroughs. And while a teacher can reside wherever he or she pleases, a firefighter must have his or her home in one of 11 counties in New York State. Police Commissioner Ray Kelly must live in the city, but a beat cop does not have to.

The move for residency requirements gained force in New York City and much of the rest of the country in the 1970s. As middle class people fled to the suburbs, city officials struggled to keep as many salary-earning, stable people in the city as they could, and municipal employees fit that profile. Some officials argued that residency requirements would keep taxpayer money in the city rather than giving it to people who would use it to buy groceries and pay property taxes in New Rochelle. This argument still holds sway in poorer, more beleaguered cities, such as Buffalo and Detroit, but others question whether, in increasingly affluent New York City, the requirements have outlived their usefulness.

On a radio call-in program last August, Mayor Michael Bloomberg alluded to this. In the 1970s, he recalled, “there were forces to try to keep people in the city. Today we’ve got the reverse problem: Too many people trying to live here.”

The debate over residency requirements is as old as the country. "Every matter, and thing, that relates to the city ought to be transacted therein and the persons to whose care they are committed [should be] Residents," wrote George Washington in 1796.

And some residency laws date back centuries: In 1829, New York State enacted a law dictating that all firefighters live in New York. In New York City, the Lyons Law, passed in 1937, required city employees to live in the city. Under urging from Mayor Robert Wagner who called the law “inequitable,” the Board of Estimate repealed it in 1962.

By the 1970s, New York had a state law that said so-called public officers –- a vague term that includes people who have decision-making authority –- had to live in the jurisdiction that employed them. But the state expressly exempted from the law uniformed workers and those in independent agencies, such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority or the Board of Education. (Teachers remain exempt even though the mayor has assumed control of the schools.) Over the years, the state has created some 70 exceptions to the rule, ranging from New York City sanitation workers to the dogcatcher of Onondaga County. As a result, city police and firefighters can live in the city, or in one of six surrounding New York State counties.

Mayor Ed Koch wanted all city workers –- even the exempt ones -– to live in the city, and the city passed a law doing just that. But the courts threw it out on the grounds that the city could not override the state law on uniformed employees. In response, in 1986, the city council passed a law that said any city employee hired after September 1 1986 and not exempted by the state laws had to live in the five boroughs. This law remains largely in effect.

DEBATING RESIDENCY REQUIREMENTS

In New York, the debate over residency requirements has involved activists on one side and employee unions on the other.

The Arguments For

Workers will be more available in emergencies: A commission appointed to investigate the violence that broke out during the 1977 New York City blackout cited a slow police response. It blamed this partly on the fact that, when the lights went out, many officers were at home in the suburbs, far from the streets of Bushwick and other hard hit neighborhoods. More recently, Bloomberg said that, if sanitation workers were allowed to live in the suburbs, it would be harder for them to respond promptly to emergencies, such as snowstorms. Ironically in New York City, many of the workers most vital to emergency response — such as police and prison guards – can live 90 miles away, while clerks and managers have to stay closer at hand.

City residents are more likely to understand and empathize with city residents: This argument is frequently raised with regard to the police department. “The hidden assumption, “the Times said in a 1986 editorial, “is that officers residing outside the city fall too easily into thinking of their patrols as â€occupation duty’ over an alien population.”

"If a person lives in the city, he can't help but have a greater feel for the city because he is here 24 hours a day," former Police Commissioner Lee Brown once said.

Following several fatal police shootings, as well as the police torture of Abner Louima, the Campaign to Stop Police Brutality, led by the New York Civil Liberties Union among other groups, called for a residency program “tied to an affirmative action plan for police officers to improve police/community relations” and increase the department’s effectiveness.

Following several fatal police shootings, as well as the police torture of Abner Louima, the Campaign to Stop Police Brutality, led by the New York Civil Liberties Union among other groups, called for a residency program “tied to an affirmative action plan for police officers to improve police/community relations” and increase the department’s effectiveness.

But others haved questioned whether it would make a difference. In 2001, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani said the city received fewer complaints against police officers who lived in the suburbs than against those who live in the city. “That doesn’t mean that police officers who live in the city are better or worse,” he said at the time.

But according to a 2001 poll (in pdf format) done by the City Council, 45 percent of city residents surveyed said requiring police officers to live in the city would be “very beneficial,” and 13 percent considered it “moderately beneficial.” Twenty-nine percent said it “would make no difference.”

Hiring city residents would create a workforce that, to paraphrase Bill Clinton, looks like New York: A study done in 1991 found that city residents applying for the police department were three times as likely to be Hispanic and four times as likely to be black as people applying from outside the city. If the city had to choose its employees from a pool of candidates where blacks and Latinos predominate, some argue, the workforce would reflect that.

Taxpayers’ money should stay in the city: People who work in the city do not live here do not have to pay city income tax or a commuter tax – it was eliminated in 1999.

The Arguments Against

People have a right to live where they want: This position sounds powerful, but the courts have not accepted it. In 2004, for example, the state’s highest court rejected the claims of a city maintenance worker who challenged the city’s residency law. And in 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the state courts and ruled against firefighters challenging the law that required them to live in New York State.

The courts seem to agree with a former mayor of Madison, Wisconsin, Paul Soglin who told Governing magazine, “People have a constitutional right to live anywhere they want. They do not have a constitutional right to public employment.”

The city is too expensive: Unions raised this objection when the city first moved to enact stricter residency requirements in the 1970s, and it has gained force today as middle class people find it increasingly hard to rent or own a home anywhere in the city, which represents many maintenance workers, clerks, technicians and other municipal employees who must live in the city, has said it is unfair that some of the lowest paid city workers are the ones who must live in the most expensive part of the metropolitan area.

Residency rules keep the city from getting the best employees: Hiring only people who live (or are willing to live) in the city narrows the pool of applicants from which the city can choose. When city school districts found it increasingly difficult to find qualified, certified teachers, many districts that had residency requirements for educators abandoned them. “With such a teacher shortage throughout the country, most districts are trying everything they can to attract teachers rather than create barriers,” a spokesperson for the American Federation of Teachers has said.

The rules are difficult to enforce: Some cities have resorted to spying. Buffalo has had a residency sleuth who conducted on site surveillance and interviews with neighborhoods to root out employees violating that city’s rules.

In New York City, some government agencies have asked some workers to sign affidavits and, in some cases, employees may blow the whistle on other employees. It seems likely the teacher’s union, which had been warring with Brooklyn Tech principal McCaskill, may have alerted education department officials that he lived in New Jersey.

THE EFFECT ON SPECIFIC PROFESSIONS

Whatever the merits of these arguments, residency requirements, and the debate about them, play out in different ways, depending upon the job.

Firefighters

Residency is a particularly sensitive issue in the fire department. Despite frequent vows by the city to diversify, the department remains 92 percent white and almost entirely male. And about half of all firefighters live outside the city. Some advocates argue that requiring firefighters to live in the city would bring more blacks and Latinos to its ranks.

Residency is a particularly sensitive issue in the fire department. Despite frequent vows by the city to diversify, the department remains 92 percent white and almost entirely male. And about half of all firefighters live outside the city. Some advocates argue that requiring firefighters to live in the city would bring more blacks and Latinos to its ranks.

For now, though, like police officers, firefighters must live in one of 11 New York counties: the five that make up the city along with Nassau, Suffolk, Westchester, Rockland, Putnam or Orange. Changing that would require action by the state legislature.

The department does give preference to city residents, adding five extra percentage points on to the department’s entrance exam. But according to Paul Washington, president of the Vulcan Society an organization of black firefighters, many people claim to live in the city when they do not. The additional five points “would have an impact if it was really enforced,” Washington says, but “it’s easy for candidates to get around it,” and the department “seems to find it impossible to come up with a residency criteria that really works.”

A 2001 audit by the city’s Equal Employment Practices Commission agrees that residency requirements might help bring people other than white men into the department. It cited an array of reasons for the department’s homogeneity, including a failure to verify residency claims. But the corrections department has the same residency requirements as the fire department, and has a uniformed force that is more than 80 percent black and Latino.

Sanitation Workers

Since 1986, city sanitation workers have had to live in the city. But late last year, the state legislature said that sanitation workers, like police and firefighters, could also reside in six other counties. The workers “are ecstatic,” Harry Nespoli, head of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, told the Daily News after Governor George Pataki signed the bill easing residency requirements. “They want a piece of the American pie. They want to own a home.”

Since 1986, city sanitation workers have had to live in the city. But late last year, the state legislature said that sanitation workers, like police and firefighters, could also reside in six other counties. The workers “are ecstatic,” Harry Nespoli, head of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, told the Daily News after Governor George Pataki signed the bill easing residency requirements. “They want a piece of the American pie. They want to own a home.”

Bloomberg, though, expressed irritation at the state’s intruding in what he saw as city business. “I don’t think any of these things should be up to the state legislature,” he said on the radio at the time. “It should be the city negotiating with its unions and the state should stay out of it -- whether it’s medical benefits, pension benefits, where you can live or any of those kinds of things.”

Elected Officials

Perhaps because so many New Yorkers come from somewhere else, voters here have accepted politicians from elsewhere. When New York was filling its first Senate seat in 1789, a Long Island native lost out to Rufus King of Massachusetts.

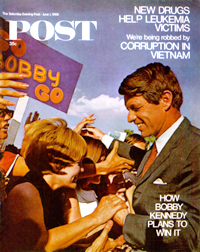

And in the years since, voters seem unfazed by politicians branded as Carpetbaggers, to use the term first coined to describe the Northerners who went South after the Civil War. Robert F. Kennedy became a New York senator even though he had spent most of his adult life in Massachusetts and Virginia. Hillary Clinton followed successfully in his footsteps more than 30 years later.

This year, people question whether William Weld was a carpetbagger when he ran for governor of Massachusetts, where he had lived for a number of year, or whether he is a carpetbagger now as he seeks to become governor of New York, where he grew up and has kept a summer home.

But some politicians have stumbled on the residency issues. Councilmember Bill deBlasio met with some derision earlier this year as he pondered whether to run for a congressional seat from Staten Island; the district includes a sliver of Brooklyn, but not the Park Slope area where deBlasio lives (and which he now represents in City Council).

But some politicians have stumbled on the residency issues. Councilmember Bill deBlasio met with some derision earlier this year as he pondered whether to run for a congressional seat from Staten Island; the district includes a sliver of Brooklyn, but not the Park Slope area where deBlasio lives (and which he now represents in City Council).

DeBlasio decided not to enter the race, but his City Council colleague David Yassky continues his quest to represent a congressional district, which his home is close to but not in. (To remedy the problem, Yassky recently moved.)

And residency requirements can offer an opportunity for the canny politician. Take Brooklyn Assemblymember Roger Green. In 2002, Green faced a vigorous challenge from lawyer Hakeem Jeffries. Green won but did not want to risk facing Jeffries again. So, when the state legislature set about redrawing assembly districts, Green made sure they moved the boundaries of his district by one block -- just enough to put the Jeffries home outside of it.

And now? Jeffries and his family have moved so they will be in the district. And Roger Green is running for Congress, to represent a district where he has lived for many years.

Â

Willets Point: A Defense

Here come the marshals again! After evicting 23 businesses in the Bronx Terminal Market to make way for a development deal with the Related Company, City Hall now wants to get rid of ten times that number in a Queens district. The city plans to use its power of eminent domain to foster what it calls economic development in the area around Willets Point. But it could instead mean economic disaster to the long-established business community that would be broken up and scattered. And while it proposes a multi-billion dollar project that would make Willets Point a “regional destination,” possibly with a hotel, convention center and retail space, the city’s planners appear to have little appreciation for businesses that already draw customers from all over the region.

Willets Point is a small triangle of land (often called “The Iron Triangle”) that sits near Corona and Flushing in the shadows of Shea Stadium. Indeed, the New York City Economic Development Corporation’s intense interest in Willets Point coincides with the announcement of the city’s latest stadium deal with the Mets.

225 Businesses (Not 80)

While the Economic Development Corporation claims there are 80 businesses in this 48-acre area, a recent survey I conducted through the Hunter College Center for Community Planning & Development instead found 225 businesses that provide an estimated 1,300 jobs. The business survey was part of a land use study, including maps prepared by the CUNY Mapping Service, commissioned by Council Member Hiram Monseratte, who has questioned the city’s plans to relocate area businesses from his district.

What accounts for the huge statistical oversight by the Economic Development Corporation? Were the small auto repair outfits run by recent Latino immigrants invisible to the agency’s planners? Perhaps we counted the ones they missed because our survey was conducted in both English and Spanish. Perhaps the fact that most businesses are renters and not owners, and many share precious high-rent building space, has made them invisible to city officials. At a time when elected officials are acknowledging the important role of immigrant labor in the city’s economy, it would appear that the city bureaucracy has failed to open its eyes to a thriving business district that serves as an entry point for immigrant workers and entrepreneurs.

While the largest number of businesses are involved in auto repair, there are also several large parts and salvage operations. The largest employer in Willets Point, however, is The House of Spices (India), Inc. According to Girdhar Assar of The House of Spices, they employ 100 full-time people and are “the largest distributor of Indian foods in the United States.” A significant portion of land is used for waste transfer and building materials storage. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority also has a large strip of land used for rail yards and parking.

The Image of Blight

Over the years, public officials who have coveted the area’s excellent location at a nexus of highway and train lines have played along with a negative public image of Willets Point as a junkyard, dangerous, and foreboding. The city government has helped foster this image by failing to put in sewers, pave public streets, and fix sidewalks. In other words, city officials helped create a condition of “urban blight” that they then propose to fix by evicting the existing businesses.

One Saturday last fall, along with a class of Hunter College students, I walked every block of Willets Point with Joe Ardezzone, a member of the Willets Point Business Association and life-long resident of the area (in fact, the only resident). We saw a thriving though sometimes chaotic and noisy business district. On Willets Point Avenue, a driver would stop and ask one of the workers where to get a new carburetor and a windshield. The curbside broker would direct him to one of the many specialized businesses. A wide variety of parts dealers and salvage yards were there to meet every need of people who came from as far as northern Bronx and eastern Long Island. Ardezzone complained that “people don’t realize there are hard-working people here just trying to make a living.”

What we saw on the ground was the kind of bustling business district that economic development experts across the country keep trying to re-create in giant development schemes, often with little success. The many specialized auto repair shops in Willets Point both compete and cooperate with one another, and the links between them make for a cooperative business community offering a wide array of services.

An Opportunity For Clean-Up

By focusing on Willets Point, city officials have an opportunity to help strengthen this network instead of destroying it. At the same time they could confront head on some of the city’s biggest environmental headaches. When auto repair facilities are concentrated, as they are in Willets Point, then City Hall has an opportunity to apply its pollution prevention programs and deal with the critical issues of waste and emissions. If these activities are dispersed, mechanics are less likely to use cleaner and more efficient technologies. More mechanics would end up working on residential blocks and dumping crank case oil down the city’s storm drains, and it will be more difficult to regulate these businesses.

As for the waste transfer stations that occupy a big chunk of land in Willets Point, there are precious few alternative locations for them in Queens. By paving the streets and enforcing environmental regulations in Willets Point, city officials could help make these waste facilities a model of sustainable management. The dust and debris that workers and business owners have to deal with would diminish. And since Willets Point is right in the flight path for LaGuardia Airport, something needs to be done about the deafening roar of planes no matter what happens to the area!

Rich In Potential

The economic potential of Willets Point businesses can be linked to the growing recycling industry as well as auto repair. The proponents of redevelopment who are quick to call the Iron Triangle a big junkyard might have missed the recent front page article in The Wall Street Journal (March 21, 2006) that hails auto scrap yards as a big source of “healthy profits.”

Contrary to the impression that The Iron Triangle is worthless, the total assessed value of property comes to some $181 million. Property values and the number of jobs per square foot are roughly comparable to those in other areas zoned for heavy industry in the city, and so are tax revenues.

Even after planning for an improved auto repair and recycling district, it would still be possible to allow for some limited redevelopment for new industrial, commercial and recreational facilities. But this should be determined through open and transparent public planning, not a developer-driven process.

Developer-Driven Planning

Over the last three decades, Willets Point has been a favorite target for grandiose development plans, all of which failed when businesses refused to be displaced. When the city’s development czar Robert Moses wanted to get rid of the local businesses, the Willets Point businessmen hired a young attorney named Mario Cuomo and beat Moses. A 1991 rezoning plan also went nowhere.

In 2004, the city’s Economic Development Corporation issued a Request for Expressions of Interest to redevelop Willets Point, and recently selected several large companies to submit proposals. While development proposals may include only a portion of Willets Point rather than a blanket condemnation of the whole area, there are two problems with this piecemeal approach. First, it will pit property owners against each other, and can very well play into the hands of a small group of speculators that have started to move into the area. Secondly, it could pit the property owners against the large group of mostly Latino workers and business owners who rent (82 percent of the total) and who stand to lose everything. Even what might seem at first to be a generous relocation benefit could be worthless when it comes to finding comparable space in a city where low-cost industrially-zoned land is disappearing from sight.

If there were an open and transparent planning process incorporating all business owners and workers, and property owners and renters, the division of the territory in a redeveloped area might look quite different from the one that will be cooked up by the consultant firms hired by the big developers. The Economic Development Corporation appears to be open so long as they keep tight control over the process, but not open enough.

Spotlight On Shea Stadium

The proposed new Shea Stadium, which would go up in the huge parking lot bordering Willets Point, is likely to overshadow the Iron Triangle in more ways than one. Local community groups are likely to focus on Shea, which long has been a sore point for many of them, because -- like so many other urban stadiums -- it turns away from its neighbors in the interest of getting fans in and out as fast as possible. Since the new Shea will have more luxury boxes and fewer affordable seats, more fans are likely to drive in and out by car, never stopping for arroz con pollo in Corona or Kimchee in Flushing. And if City Hall has its way, fans won’t even be able to get a tire fixed in the neighborhood.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

Stadiumania: Snapshots of an Obsession

When a new Yankee Stadium (above) was approved by the City Council one day before the Mets unveiled their design for a new stadium in Queens (below) last week, it was just the latest episode in New York City’s sports building frenzy.

Nine sports teams in the metropolitan area –- the Yankees, Mets, Knicks, Rangers, Jets, Giants, Devils, Islanders and soon to be Brooklyn Nets –- all have plans to build new venues. And there are even plans to build a NASCAR race track in Staten Island.

Together, the projects will cost more than $5 billion and require hundreds of millions in taxpayer subsidies. The plans have also sparked vigorous debate over jobs, the use of parkland, and traffic –- and whether public money would be better spent elsewhere.

In an effort to win over New Yorkers, the baseball teams in particular aren’t just arguing that their new stadiums are good for the city’s economy - they are trying to appeal to feelings of nostalgia in a town where baseball was born, the first ballpark hot dog was served, and some Brooklynites still mourn the loss of a team that left a half a century ago.

"I almost feel like I'm walking through the rotunda, 8 or 9 years old, holding my dad's hand,” said Mets chairman Fred Wilpon, his voice cracking as he described the new stadium design meant to evoke memories of Ebbets Field, where the Brooklyn Dodgers played until they left for California in 1957.

Click Here for a Photo Essay on New York City Stadiums and the Issues Surrounding Them

Â

Subsidized Housing

Since the 1950’s, government subsidy programs have helped private developers build affordable rental housing in neighborhoods across New York City — housing that has improved conditions and stabilized communities.

But now we are losing this supply of affordable housing at a fast rate, because, on the one hand, a soaring housing market has more and more landlords opting out of the subsidy programs, and, on the other hand, the federal government is cutting off the subsidies to landlords accused of poor management and neglect. Since 1990, the city has lost close to 30,000 apartments, a quarter of the apartments created by the largest subsidy programs for families of low and moderate income. And thousands more units are in the process of being de-subsidized right now.

Housing For The Poor And Families Of Color

Who lives in this threatened housing? The answer is mostly low-income tenants and families of color. Last year, New York City lost a record 5,518 apartments, as landlords removed their buildings from subsidy programs: Nearly 80 percent of the losses were in Harlem and the South Bronx.

Tenants in federally-funded housing developments (mostly "section 8" housing) are 45 percent black and 33 percent Latino, with a median household income of $12,000 a year. Tenants of Mitchell-Lama housing (a program established by the state in 1955 to encourage low- and moderate-income housing by offering developers low-interest mortgages and tax abatements) are 44 percent black and 20 percent Latino. Though Mitchell-Lama is often thought of as a middle-income program, about 40 percent of its households have incomes below $20,000 a year. Another 30 percent of households earn less than $40,000 a year. The median annual household income is just $26,000.

Priced Out Of Harlem, And The Bronx

These people cannot hope to survive in New York City without affordable housing. In Harlem, with over 3,200 Mitchell-Lama households, the average unregulated – market level – occupied apartment in the neighborhood rents for about $1,000 a month. How could a household with a $20,000 yearly income, taking home about $16,000, pay $12,000 of that in rent?

The cost of housing is rising fast even in many traditionally lower income communities like Bushwick and Williamsburg. In the latest Community Service Society survey, we found that housing was a major concern for low-income residents, topping safety issues such as crime or fear of a terrorist attack.

Until last year, the loss of Mitchell-Lama housing was concentrated in higher-rent Manhattan areas south of Harlem, just as one would expect if high rents were providing the landlords the motive for removing buildings from subsidy programs. But the market forces driving the loss of subsidized housing finally hit home in Harlem, with the landlords of three large developments opting out of the program -- Riverside Park Community, Schomburg Towers, and Metro North. And now it appears to be hitting the Bronx, where eight more Mitchell-Lama buy-outs are currently pending.

Owner Neglect Or Mismanagement

The other threat to subsidized housing is owner neglect or mismanagement, which can lead the federal government to cut off subsidies or even sell the property through foreclosure. This tends to happen in neighborhoods where rents are low and the tenants are poor. In the last 15 years, the Department of Housing and Urban Development foreclosed on 17 developments in New York City, with 2,264 apartments –- more than half in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. Thousands more are at risk for the same reasons.

Foreclosure isn’t always a bad thing; the outcome can be good if the new owner is committed to preserving affordability and maintaining decent conditions. Last year, the city worked with a coalition of nonprofit tenant and housing groups to transfer three distressed buildings – two in Harlem and one in Bedford-Stuyvesant – to nonprofit ownership. But more resources and cooperation are needed from the federal government to finance improvements and transfer buildings to a preserving owner.

Squeezed From Both Sides

Usually we think of exploding rents as affecting one group of neighborhoods and deterioration as affecting another. But what’s happening to subsidized housing in Harlem and the Bronx today shows how both threats can converge on the same neighborhood. There is reason to be concerned that more neighborhoods will soon find themselves squeezed from both sides – and low-income New Yorkers will be squeezed out.

Given soaring rents and the numbers of homeless, the city cannot tolerate further losses to these urgently needed housing resources. There is a danger that Washington will withdraw further from the housing it helped develop at great public cost. The city and state must continue to press Washington and also do what they can to fill the void.

A partial response to the threat of severe rent increases is Local Law 79, passed by the City Council over the mayor’s veto. It allows tenants to buy their buildings if landlords decide to take them out of subsidized programs. Landlords sued to stop the law from taking effect. The case is still in court.

The mayor has proposed that all Mitchell-Lama rentals in the city be placed under rent stabilization. This would help, but only action by the state Legislature can make it happen.

David R. Jones is president of the Community Service Society of New York, a social services organization that deals with the problems of poverty. Â

New York's Port, Beyond Dubai

Bye Dubai Buy: The New York Cruise Ship Terminal

For many New Yorkers who make their living from the city’s harbor, the high-pitched, month-long debate over the so-called Arab takeover of the port was beyond baffling.

Dubai Ports World, a company owned by the United Arab Emirates, was going to operate only one facility in New York -- a port terminal that handles just cruise ships, not cargo. (It would also have shared control of another terminal in New Jersey.) But there are seven other port facilities in New York Harbor, and the company would have had nothing to do with them.

Faced with ever-increasing opposition in Congress fueled by public opinion, DPW announced that it was dropping the port deal, and would "transfer" the lease to an American company. But even if the deal had gone through, Dubai -- despite what politicians and columnists said over and over again -- would not have “owned,??? “controlled??? or “taken over??? the ports. The port is owned by the taxpayers and controlled by state and local governments. The lease that DPW had purchased from a British company was simply to manage the facilities.

“It’s not like foreigners are just coming in and doing their own thing,??? saidCaptain Timothy Ferrie, a ship pilot and president of the Maritime Society of New York City. “There’s American involvement every step of the way.???