|

Forty years ago, New York reacted to the loss of old Pennsylvania Station by passing a law to protect city landmarks. In this series, in partnership with Open House New York, New Yorkers with a stake in the physical city will argue the consequences of the law, the merits and drawbacks of the preservation movement, and what the future might bring. |

When Gerard Wolfe, then a professor at New York University, first entered the main sanctuary of the Eldridge Street synagogue in the mid 1970s, he found a time capsule. The 19th century Lower East Side building still served as a synagogue but, over the years, as the size of the congregation dwindled, the worshippers had moved downstairs and shuttered the doors to the main area.

Wolfe, who was writing a book about the synagogues of the Lower East Side, discovered a space both spectral and spectacular. Cobwebs extended between the building’s hand-painted pillars. Old prayer books were scattered among the pews. Decades-old prayer shawls remained hidden in special compartments of the benches intended for the tallisim. Newspapers, from the 1940s, opened to the sports pages, lay on seats, a clear reminder of the people who attended services and would perhaps sneak a look during the rabbi’s sermon.

And yet the grandeur of the sanctuary remained intact. The sanctuary’s exquisite (if deteriorated) stained-glass windows, hand-painted murals, and Victorian fixtures signaling the importance of the structure for its Jewish immigrant founders.

And yet the grandeur of the sanctuary remained intact. The sanctuary’s exquisite (if deteriorated) stained-glass windows, hand-painted murals, and Victorian fixtures signaling the importance of the structure for its Jewish immigrant founders.

Wolfe’s discovery marked the beginning of a restoration project, still going on 30 years later, that serves as a model for other historical houses of worship in New York City and throughout the country.

SYNAGOGUE AND STATE

Under the leadership of leading preservationists and community activists, including Roberta Brandes Gratz, an urban critic and journalist, the Eldridge Street Project was founded. This group wanted to save the building. They also wanted to open this historic treasure to the public in the immediate community and beyond.

They faced daunting challenges. Unlike many other historic sites around the city, the synagogue was not about to be torn down and had not been vandalized. But it was in danger of falling down. The roof leaked, threatening the interior. The cellar had filled in, and a stair tower collapsed.

The city of New York does not give money to houses of worship for fear of violating the constitutional restrictions on state aid to religious institutions. Some foundations are also reluctant to aid religious groups. And so, it was very important to establish an educational and cultural center serving a diverse constituency. Today, the congregation -- officially called Congregation K’hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz -- owns the building. The congregation is several dozen strong, a stalwart group committed to the continued spiritual life of the building.

The city of New York does not give money to houses of worship for fear of violating the constitutional restrictions on state aid to religious institutions. Some foundations are also reluctant to aid religious groups. And so, it was very important to establish an educational and cultural center serving a diverse constituency. Today, the congregation -- officially called Congregation K’hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz -- owns the building. The congregation is several dozen strong, a stalwart group committed to the continued spiritual life of the building.

The restoration is the responsibility of the Eldridge Street Project, the non-profit non-sectarian group formed in 1986. Under a memorandum of understanding, the congregation controls all the religious aspects of the synagogue, while the project oversees the restoration – included related fundraising – and the cultural life of the building. The project runs educational and cultural programs, as well as tours, for some 20,000 visitors a year.

Whenever a church or synagogue asks us for advice about how to restore their site, we tell them the first step is to create a separate 501-C3 (tax exempt) organization to make a clear distinction between the religious life of the building and the historical or educational functions. While few, if any, groups are identical to us, some are similar. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is one. In some parts of the country, particularly the South, where the Jewish community is fast disappearing, not-for-profit organizations have taken over synagogues and restored them as museums or for other projects. In these cases, though, there is no congregation anymore.

In recognition of our public service, the city provided first program support and more recently capital support for the restoration of our landmark building. There was little resistance to public money coming to us. Norman Siegel, then executive director of New York Civil Liberties Union, called the funding “constitutionally suspect,” but that was about it. The city funds served as a rallying point for us to get other support.

The city was largely responsible for the most recent phase in our restoration -- the creation of a new cellar. Much of the area was filled with dirt, so workers had to excavate it while, at the same time, supporting the building -- an engineering feat. The city money, matched by private donations, was particularly welcome because private donors often do not want to pay for plumbing or mechanical systems. Now we can turn our attention to the most beautiful aesthetic parts of the restoration.

Another interesting example of the sensitivity of a sacred site receiving public funds arose in connection with funds received from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Commission rules bar it from supporting a capital project that includes religious iconography. Several years ago, we approached them for funding for our roof project. This turned out to be tricky as the finials mounting the roof feature elegant Stars of David. Eventually, we found a clear stretch of work without the stars and received a $25,000 grant from the commission.

Another interesting example of the sensitivity of a sacred site receiving public funds arose in connection with funds received from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. Commission rules bar it from supporting a capital project that includes religious iconography. Several years ago, we approached them for funding for our roof project. This turned out to be tricky as the finials mounting the roof feature elegant Stars of David. Eventually, we found a clear stretch of work without the stars and received a $25,000 grant from the commission.

Being designated a city and national landmark has also propelled us forward The city landmark recognizes the architecture, while the National Historic Landmark designation is both about the architecture and the building’s significance as being representative of immigrant religious structures. Receiving national designation is a real challenge, as you must explain in detail why your site is either the only one of its kind or a platonic ideal of a phenomenon. Much of our fundraising has been through national direct-mail appeals – many to people who have a tie to the neighborhood or see this site as a kind of portal to their ancestors’ Jewish experience. To these people, designation as a National Historic Landmark has been very meaningful. It serves as a kind of vetting.

A LOWER EAST SIDE STORY

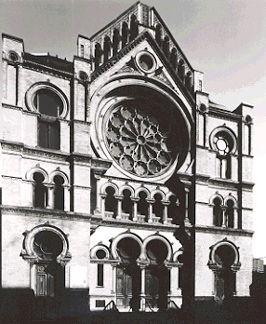

Certainly, this building has been enormously significant both in this neighborhood and to the East European Jewish experience in America. In 1886, when construction began on the building, most synagogues on the Lower East Side were shtetla, small storefront synagogues for people from a single city. But Eldridge Street was unique -- a cosmopolitan congregation of people from all over Eastern Europe.

It was the first grand structure in the neighborhood, taking 10 months and about $100,000 to build. The members constructed a building that dominated the block. This was the first time they could worship openly as Jews so they put Stars of David on the façade. And because many of them worked in factories and lived in dark tenements, they placed windows on every side of the building to beautifully illuminate their synagogue.

Some of the Eldridge Street synagogue founders had been in America for a while already. They had arrived in the 1850s -- before the major wave of East European Jewish immigration in the 1880s and 1890s – and had established themselves.

As many as 1,000 families belonged. They ranged from very wealthy members to people who could not afford the dues. We know from minute books that some people paid $2 for their seat, and some paid $200. It is and was an Orthodox house of worship so the men and the women sit separately.

As many as 1,000 families belonged. They ranged from very wealthy members to people who could not afford the dues. We know from minute books that some people paid $2 for their seat, and some paid $200. It is and was an Orthodox house of worship so the men and the women sit separately.

Until the 1920s, this was a very vibrant congregation. Then, the immigration laws changed, so the immigrants stopped arriving. At the same time, everyone who lived on the Lower East Side wanted to get out. The Jews left for the Bronx, Brooklyn and even the Upper East Side. With no new Jewish immigrants arriving to replace them, this and other congregations got smaller and smaller.

Some of our visitors are disappointed the area is not still Jewish. But this is a story of immigrant success. The East European Jews wanted to leave the neighborhood, and they were able to.

REDISCOVERING THE SYNAGOGUE

Despite the changes, a congregation always remained at Eldridge Street. But it could not maintain the building’s grand main sanctuary and so, at some point, probably in the 1950s, the members closed the doors and stopped coming upstairs to the main synagogue.

Today, the building boasts a new slate roof. The cellar has been dug out. Air conditioning and ventilation systems have been installed, while the crumbling stair tower, now rebuilt, will house an elevator. But the synagogue’s striking architectural details, including rose windows, 70-foot ceilings and a velvet-lined ark, remain. So far, the project has raised about $8 million of the estimated $12 million need for the renovation. At time progress has been slow-going, but the restoration is currently moving ahead, and we anticipate completion by early 2007.

And the building is once again open. Children, adults, and families come to learn about Jewish history, the immigration experience and architecture and historic preservation. They represent all cultural backgrounds (For a schedule of tours, click here)

BOTH EGG ROLLS AND EGG CREAMS

Many people visit because of nostalgia or because the Lower East Side was the gateway place for their families. Others come to see the space and learn about the American immigrant experience, particularly the East European Jewish experience.

Many people visit because of nostalgia or because the Lower East Side was the gateway place for their families. Others come to see the space and learn about the American immigrant experience, particularly the East European Jewish experience.

Amid all the educational programs the Eldridge Street Project offers – some focusing on architecture, others on the East European Jews in the United States – we also work to reach out to the synagogue’s neighbors, many of whom are first generation Chinese immigrants. The Eldridge Street Project’s relationship with these residents testifies to the continuing immigrant experience in New York.

A few weeks ago, our annual egg roll and egg cream festival showcased the two communities – Chinese and East European Jewish -- that have lived or live today on this block. More than 1,500 people joined us for klezmer music, Chinese opera, and Jewish and Chinese folk music performances; Hebrew and Chinese scribal art, Yiddish and Chinese games, and, of course, kosher egg creams and egg rolls.

Last year, we presented a video installation featuring a 12-minute film projected at night through the synagogue windows. It included a 12-minute history of the synagogue and its neighborhood and images that explained what is happening today.

Eldridge Street encapsulates a piece of our history that is important to preserve. It is an architectural landmark, a place of historic importance in the city, a beautiful place. But, as the festival and the video project have demonstrated, what is even more amazing about the building is the new life it has taken on as a place where people can come together and learn about the past.

Amy Milford is director of public and community relations for the Eldridge Street Project.Â