Forty years ago, New York reacted to the loss of old Pennsylvania Station by passing a law to protect city landmarks. In this series, in partnership with Open House New York, New Yorkers with a stake in the physical city will argue the consequences of the law, the merits and drawbacks of the preservation movement, and what the future might bring. |

In April 1975, 2,000 new apartments opened on Roosevelt Island -- a tram ride away from the East Side of Manhattan. And so this April 25 marked the 30th anniversary of the current Roosevelt Island community.

But while many New Yorkers think of Roosevelt Island as a new community, for much of the 19th and early 20th century it played an important role in the life of the city. Much of this history was lost in the 1960s and 1970s, when the city was only beginning to recognize the value of preserving its history – and its old buildings. As attitudes and policies changed – with, for example, the enactment of the Landmarks Law that created the city Landmarks Preservation Commission – a handful of buildings were saved. Now, with the real estate market putting new pressures on the island, it is more vital than ever to preserve the history of this 147-acre piece of land in the East River.

For decades, Roosevelt Island, Blackwells Island, or Welfare Island -- whichever name you want to use -- was home to a penitentiary, workhouse, lunatic asylum, Metropolitan Hospital, City Hospital, and various almshouses. Goldwater Hospital, for victims of polio and other chronic diseases opened in 1939.

And so Roosevelt Island was key to our corrections history, our medical history, our social service history. It is the history of how people were treated and of what people thought.

Over the years, much of this has been forgotten because, as someone once said to me, these were not the golden years. The institutions on Roosevelt Island were not the kinds of places you glow about, but they did provide desperately needed services. In the 1940s, 10,000 people lived on the island, mostly in institutions. We should not forget them.

Designed by James Renwick, the lighthouse at the northern tip of Roosevelt Island helped ships navigate their way through treacherous waters. |

Roosevelt Island is also part of our architectural history. The works of Frederick Clark Withers, James Renwick, and Alexander Jackson Davis -- three very prominent architects -- are still visible on the island.

If the island had been developed 10 or 20 years later, the builders probably would have saved more of the structures. But in the 1960s and 1970s, many beautiful buildings were just bulldozed. The development corporation had the attitude, "when in doubt, throw it out." Their theory was that it is cheaper to build new.

And so we lost the city hospital, a large Versailles-looking building at the southern end of the island. The administration tore it down, in the early 1990s, but it could have been restored into a beautiful chateau-like building.

The Central Nurses Residence, a massive yellow brick dormitory built for nursing students and staff in the 1930s, was a perfectly good building that could have been converted to a different use, but the island administration decided to abandon it, because it interfered with vehicular traffic flow. And some beautiful houses at the northern end of the island could have been rebuilt.

Our landmarks are technically owned by the state of New York, meaning the city has little control over them. The other dilemma is that the government exempts themselves from any penalties and protection of abandoned landmarks. Thus, the Smallpox Hospital, a government building, has never been rescued by a municipal agency.

We are lucky that the developers saved at least the six historic buildings we have today. Without our 40 years of landmark legislation, these structures would almost certainly have vanished as well, But today all are on the National Register of Historic Places and on the state register and are designated New York City landmarks.

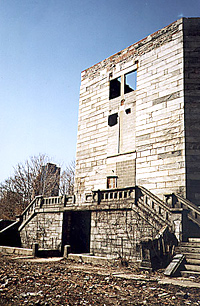

If you start from the southern tip of the island, you see the smallpox hospital designed by James Renwick in the 1860s. Back in the 19th century, this was about the only hospital where rich people went. Usually, poor people went to hospitals and died, while rich people were treated at home. But because smallpox was so communicable, even rich people who contracted it had to go to the hospital.

The Octagon once served as the entrance to the country's first municipal lunatic asylum but will soon link two wings of an apartment building. |

The building later became Riverside Hospital and then a school of nursing -- the third one in the United States -- until it was abandoned in the 1950s. For more than 20 years, the site remained closed to the public.

But some New Yorkers remembered the building, perhaps noticing it lit up at night when they drove along the FDR Drive. And so in 2003, when Open House New York featured it as one of its sites to visit, 400 people came on a single day to this landmark at the island's southern tip. In 2004m more than 700 people again visited the site in two days of Open House New York.

They saw a building in terrible condition. In winter, as water freezes and melts, cornice stones fall from the facade. But the building's grandeur shows through the flaws.

Imaging and computer work indicates that the hospital would need millions of dollars in repairs to stabilize it. No one has come up with an economically feasible plan to restore the building. Most likely, it will become a kind of stabilized ruin.

A kinder fate has befallen Strecker Memorial Laboratory, a charming Withers and Dickson Romanesque structure. Built in the 1890s, this medical research facility sat fallow for almost 50 years. Then the Metropolitan Transportation Authority decided to use the building for a power conversion substation for the train lines that run beneath the island. electricity station. The agency restored the building's exterior and installed equipment inside. It opened five years ago and remains in beautiful condition, an example of how creative thinking can save an old building.

As you go up Main Street, you see Blackwell House, a gray wooden farmhouse built in 1796 by the Blackwell family when they owned the island. In the 1970s, when the island was developed, architect Giorgio Cavaglieri completely restored the building. Unfortunately, the people who ran the island in the 1990s leased Blackwell House to tenants who did not take care of it. Now, we are in the final steps of obtaining the long promised state funds to do repairs and hope to reopen the house as a community building and preserve this building for the future.

The next landmark is the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, an 1889 brick and brownstone chapel designed by Frederick Clarke Withers, who also designed Jefferson Market Courthouse. Originally, the chapel served the residents of the city home or almshouse, which at one time, was home to between 2,000 and 3,000 poor and homeless people. Restored, also by Cavaglieri, in 1975, the church is used by both the Episcopal Church and the Catholic Church. It is also our largest community meeting space.

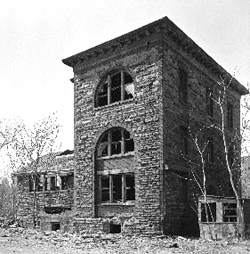

The Octagon offers a more complicated story. Built in the 1840s, it served as the first municipal lunatic asylum in the country until 1895 when it became Metropolitan Hospital. As a young writer, in 1843, Charles Dickens visited the asylum and wrote about the listless, mad people cowering in the hallways. As a reporter for Joseph Pulitzer's New York World, Nellie Bly, whose real name was Elizabeth Cochrane, had herself committed to the asylum for 10 days in 1887. She then wrote a scathing expose on the horrible conditions, which did succeed in improving it a little.

During this period, the Octagon functioned as the entrance to the asylum, with two wings coming off of it, creating an L-shaped building. Now the wings are gone, but the octagonal entrance is being completely restored. Two fairly modern-looking new wings will hold about 500 apartments. They have already added four floors adjacent to the Octagon -- the landmark Octagon. And some people do not see the merit of saving any of it. Recently, I was at the Octagon building and the construction site manager said to me, "Why didn't they just tear that down a few years ago?"

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority saved Strecker Memorial Laboratory when it renovated the 1890s building for as a power conversion substation. |

Putting modern wings on a landmark building is not an ideal solution. But at least a small piece of the original building, including a recreation of the beautiful interior staircase in the dome, remains. The exterior will be an exact copy of the original, since it is a landmark structure.

And in some sense, visiting the Octagon to get a sense of its history resembles going to Rome. When you go to the Coliseum, you don't see lions or people being slaughtered. You have to use your imagination. Sometimes, small fragments make people think about what was in a place and what went on there.

And last but not least we have the lighthouse, also designed by Renwick, which has been repaired and restored. Only 53 feet tall, it was built in 1876 to light the way at the tip of the island because the river's swirling currents are very treacherous.

While we celebrate these buildings, challenges remain. Raising money for the projects is always a problem. And today's real estate market could also affect the island, home now to some 10,000 people. About 1,200 people will move into the new wings of the Octagon. The Southtown development is supposed to include nine buildings. Plans to put affordable housing there now are in doubt. The landlords would like to see resident of 2,000 original affordable apartments lose their subsidy and rent the building at market rates. It has become a gold rush.

If you come to the island on a summer late afternoon or evening, parents and kids are sitting in the park outside the chapel. We have beautiful little cul-de-sacs and little grassy areas. They are empty because people like to be in public spaces. They like to be on the street. Developers and urban planners often do not seem to understand that. And people like our old buildings. They like to sit outside of Blackwell House and the little park next to it. The lighthouse park also is very popular. These landmark structures are somehow more comfortable than the concrete of our 1970s design.

I love Roosevelt Island. It's a small town, people caring about each other, people knowing each other, sitting around and schmoozing. It's almost like the old days. And our six historic buildings contribute to that feeling. They tell us about our past and they add character.

Judith Berdy is president and historian of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society