Hallway Settlements In Housing Court

The hallways in the city’s housing courts are filled with landlords’ attorneys and tenants all talking at once, mothers with young children in tow, people arguing, sometimes heatedly, over the various circumstances of the cases. The hallways are where most of the action –- the arguments between landlords and tenants –- in the housing courts takes place. And the hallways are where many landlords (almost always represented by attorneys) work out deals with their tenants (almost never represented by attorneys).

But these “hallway settlements” are often unethical, according to Russell Engler, a law professor at the New England School of Law, who explored the subject during a recent ethics course held by the New York City Bar Association. Many of the lawyers involved in hallway settlements, Engler said, may have no idea they are breaking ethical rules.

The court itself has acknowledged the problems with hallway settlements -- and vowed way back in 1997 to eliminate them. But that effort has largely failed.

“The court discourages hallway settlements" said Judge Fern Fisher, the administrative judge who oversees housing court. However, there is a "practical issue," she says. "We’re doing our best."

Why Hallway Settlements Are Unethical

The ethical rules attorneys follow are written with the assumption that two attorneys are negotiating for their respective clients. But in housing court almost all tenants represent themselves –- and not by choice. Many are poor and cannot afford attorneys; free legal services are available to a small fraction of the poorest among them. The providers of such services have had their funding cut substantially over recent years and can represent fewer and fewer people.

In criminal matters, the courts have ruled that a defendant has a constitutional right to legal representation. No such right has been established in housing cases -- though housing advocates believe it should be.

Unrepresented litigants in housing court do have a right to have a court attorney mediate the discussion that occurs between a tenant and a landlord’s attorney. But many tenants are unaware of this right and the volume of cases limits the amount of time and personnel that can be used on each case. Each and every day, the 51 housing court judges deal with about 1,200 cases.

The Lawyer’s Code of Professional Responsibility, put out by the New York State Bar Association, states that when dealing with people who are not represented by attorneys, "a lawyer should not undertake to give advice to the person who is not represented by a lawyer, except to advise the person to obtain a lawyer."

For attorneys, giving advice means one of two things, Engler explains --telling people how the law applies to their cases, or proposing or suggesting a course of action. This includes telling people the possible outcomes of their cases and listing a “parade of horribles,” he said.

In the negotiations occurring daily in the hallways at housing court, tenants are routinely told that if they do not sign agreements to settle cases, they will be evicted. Others are told the repair issues they cite for not paying rent “don’t matter.”

"Many conversations violate the rules that prohibit lawyers from overreaching, threatening, misleading and pressuring in their negotiations with unrepresented litigants," Engler explains. But these happen routinely, he says, in housing court hallway settlements.

Surprised Attorneys

The news that attorneys’ behavior often violates ethical rules was met with some incredulity by some attorneys in Engler's class. One commented during the class that the court itself instructs litigants in housing court to talk to each other in the hallway.

“Lawyers are permitted, and expected, to speak with unrepresented litigants,” Engler says. “The problem is with what many of them say."

The rules governing such interactions are clearly not well understood.

"Many attorneys are not familiar with the rules of the game, and part of the reason for that is that there are no repercussions,” Engler says. “Complaints are not triggered for a variety of reasons. First, the behavior is in the hallway and is not monitored. Second, the unrepresented person does not recognize the problem and has enough to worry about without filing an ethics complaint."

Judges Can Only Do Just So Much

Judges do not seem to be big fans of hallway settlements. For one, they can only do so much when they review the agreements. “I can’t supervise conversations in the hallway,” one judge at the ethics class said. “There’s a great deal that goes into the creation of that document that I have no access to.”

That is one reason why in a 1997 initiative to reform housing court, the court sought to eliminate hallway settlements. But court officials appear to have given up the fight.

Judge Fisher said the bar association’s class, which she moderated, was one part of an effort to educate attorneys, who need to take the lead on addressing the problem.

“It has to be an effort by the profession because we’re not in the hallways spying on attorneys, nor would it be appropriate for us to do that,” she said. “It’s a matter of the profession as a whole understanding that the prevalence of self-representation is not going to stop. It’s going to grow.”

But Engler believes the court has to step up.

“I agree the profession as a whole needs to act,” Engler wrote in a follow-up email message. “However, the court itself bears responsibility since the negotiations occur under its auspices. Through oversight of the negotiation and stipulation process, the court can have the most immediate impact.”

Like other professions, lawyers themselves establish ethical guidelines for their work.

“From a point of ethics, the rules should be enforced and the misconduct should be addressed,” Engler said. “Having unenforced rules may be worse than having no rules at all because it seems hypocritical. I would add that the ethics problem is just part of the bigger problem of fairness in the courts for people without lawyers.

“You can’t leave people at the mercy of lawyers who are trying to represent their clients but along the way are misbehaving,” he said. “It’s a mismatch. Most citizens, if you ask them if it’s fair to pit an unrepresented party against a lawyer would immediately see the unfairness of it.”

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations that has worked to end these hallway settlements. Â

Bronx Terminal Market And The Subverting Of The Land Use Review Process

It used to be that big developers had to take a chance, not knowing whether their projects would get approved in the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). Now, with the Related Company’s proposal for the Bronx Terminal Market, City Hall has put up a money-back guarantee. The city, through its Economic Development Corporation, is a co-applicant, but is assuming all of the risk while Related could end up with all the profits.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg is taking yet another bite out of ULURP, a public review process that is mandated by the city charter. He is already letting the state’s Empire State Development Corporation override local planning powers in Brooklyn’s Atlantic Yards project. He gave the state a ULURP-free hand at Ground Zero. And now with the Bronx project he’s sending a strong message to everyone involved in the ULURP process that the city’s money is at stake if they don’t approve it.

This month the City Planning Commission is poised to approve the conversion of the Bronx Terminal Market into a million-square-foot shopping mall for big-box retailers. The Related Company bought the lease to the city-owned land under the market with the idea of evicting the 23 retailers on the site and building what they call a “gateway” to the Bronx. As reported in the Village Voice and the New York Times, Related boss Stephen Ross is a friend of the mayor and former business partner of Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff, who once consulted with Ross about development of the site. Not only did the city offer Related tax incentives, tax-free Liberty Bonds, low-interest loans, and $14 million in cash; they promised they would reimburse the developer for the cost of the lease if it didn’t get the zoning changes it needed.

This is a bold use of the mayor’s power, and the taxpayer's money, to undermine the ULURP process and everyone who has a role in it -– community boards, borough presidents, the City Planning Commission and City Council. It’s not as if the community boards and borough presidents have much to say anyway, because their votes are advisory. The local community board and Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion approved the project with conditions, but at the end of the day they won’t be standing in front of the bulldozers. The planning commission never votes against the mayor, who appoints the majority of its members.

Though the City Council could be a deal-breaker or trouble-maker, in this case the Bronx Council members are mostly on board. The Bronx political establishment swooned at the promise of new jobs and woke up too late to influence the project. According to recent press reports, Bronx City Council member Maria Baez, for one, received generous contributions from Related and supports the project. Council member Helen Foster, also from the Bronx, has come out against the project but so far hasn’t found a second.

But aside from feeding the political money machine, here’s what the mayor’s $32 million money-back guarantee to Related does: everyone involved in ULURP is effectively on notice that the city has a financial stake and will lose out if the project is voted down. The city will be stuck with a piece of property they have no plans for and 23 angry site tenants.

The mayor is also sending a message that he can guarantee zoning changes before they go through the required land use review process. The various bodies involved in the ULURP process, not just the mayor, are jointly entrusted with the responsibility for making decisions about the future of the city. Imagine if a borough president or the City Council were to offer an insurance policy to their favored developers -– there would be an immediate outcry from City Hall.

Following the Related project, everyone who applies for a zoning change should have the right to demand an insurance policy from the city. Is the mayor, who once said corporations don’t need incentives for doing business in the city, now inventing a new one?

Relocation of Unique Business Complex

Another problem with this project is the city’s cheerful readiness to evict the merchants at the Bronx Terminal Market. This is a truly diverse group of small immigrant entrepreneurs, among the many thousands in the city that reflect its noted international character. They are from Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. They supply unique ethnic and tropical produce to local retailers throughout the city. They are a Chelsea Market in the making. If only the city had an economic development policy that could promote such enterprises.

Instead of incorporating the 23 tenants in a plan to redevelop the site, the city wants to disperse them. According to Richard Lipsky of the Neighborhood Retail Alliance, who supports the tenants, “the thing that makes the most sense is a site on the footprint” of the new project. Dispersed relocation would destroy the unique one-stop-shopping value for customers. The Bronx Terminal Market merchants have long-lasting ties with customers from all over the Bronx and northern Manhattan who have been shopping there for decades. They also complement each other’s businesses. In their place, local consumers will be treated by Related to the same industrialized, processed food and packaged merchandise that is already available at every suburban mall in the nation. This blindness to ethnic businesses comes from an administration that filled its bid for the 2012 Olympics with romantic rhetoric about New York City’s multi-ethnic character.

City-Planned Blight

This is not to romanticize the conditions at the Bronx Terminal Market, which the site tenants have complained about for years.

The sad state of the market isn’t just the fault of a bad landlord. It is the product of decades of benign neglect by the city. When the city fails to be proactive and plan for development, it sets up any outside developer who barges in and automatically looks like a savior. The city is in the habit of blindly taking any offer that produces quantitative results –- jobs and housing -– without seriously evaluating other options or looking at the impact on the quality of neighborhood and city life.

When David Buntzman extorted a 99-lease to the property from the Lindsay administration, to which he made generous contributions, the market had 100 merchants. The city never lifted a finger to improve conditions on the site. They never bothered to involve the merchants, who were summarily told to get out in March of this year. There was never a serious public discussion about what kind of development there should be on the site or how the existing merchants could be incorporated. Sadly, this same approach has been taken for decades in other areas of the city, like Willets Point in Queens, where the city is complicit in the blighting process and ignores the local businesses.

The Bronx Terminal Market project also has not been carefully planned in conjunction with another nearby megaproject, the proposed redevelopment of Yankee Stadium. The environmental studies for both projects fail to look at cumulative impacts on traffic and open space. Together, they could very well reverse the successful revival of Bronx’s business and civic center that took decades of incremental improvements by local merchants and residents. Together they turn the core of the Bronx into a suburban-style mall and entertainment complex. The one hopeful sign is that Bronx’s Community Board four voted down the new Yankee Stadium.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

Eminent Domain Benefits Developers, Not the Public

In general, I do not believe that eminent domain should be used for private economic development.

|

Related Articles: |

There are alternatives to eminent domain. Private developers who want to build large projects can buy the existing tenants out. And if there are holdouts – as was the case with the one building, that refused to sell out for the Rockefeller Center development - it is possible to build around an existing location.

I also believe that when you take a huge swath of property and try to build it all at once we generally end up with a less interesting, less textured, and less vital environment that may not produce as much in terms of economic development as a more mixed plan.

In the case of Atlantic Yards plan with the Frank Gehry buildings and the arena, developers plan on taking over not just residences, but a lot of small businesses as well. There is a tendency of people who run economic development corporations to see anything that is not big business that is not a multi-national corporation, as unworthy. Small businesses are often the birthplaces of larger businesses that drive the economy. We must always look at who benefits and who loses in cases of eminent domain.

I would be less concerned about the use of eminent domain if I thought that it was really for a public purpose, rather than for the benefit of developers. We are in an era of public/private partnerships and what typically happens is a developer comes to the government and says, “We like that property. We think we could make good use of it. Why don’t you condemn it for us.” Then the government goes through with a charade of a public process and does it.

Also the argument that these decisions should be left up to elected officials or legislative bodies is problematic. When we voted for Michael Bloomberg in the last election, we didn’t get to vote on whether we should develop Willets Point or the West Side of Manhattan, we just had to choose between two candidates.

Unless you have input into the actual programs as opposed to saying we can kick these officials out – and think of how long it took before Robert Moses finally met his demise – there isn’t much that can be done.

Eminent domain can always be used for a high school or an actual public facility, but it should not be used for economic development that benefits a developer, corporation, or shopping mall operator. We use the public sector, and then rationalize it by saying the development will produce jobs and taxes.

Many of these projects also get tax abatements. So it is not even clear that they create much in taxes. And it is difficult to say whether new jobs are created as a direct result of physical development or whether it is just a movement of jobs from one place to another.

Susan Fainstein is a professor and acting director of the urban planning department at Columbia University. Her remarks were adapted from an address at a recent event at the New York University Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and the New York Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association.

Â

Eminent Domain is a Tool, Not a Conspiracy

There is nothing evil about eminent domain.

|

Related Articles: |

Eminent domain is a tool. Whose hands that tool is in determines whether or not is used for what people may see as “good” or “bad.” The political process is defined by public participation or unfortunately, the lack thereof. Whether government makes the right decision or wrong decision is not a function of the tools that are wielded, but of the process.

When it comes to the issue of eminent domain, I think we are seeing a pendulum swing.

In New York City, we have a uniform land use procedure, known as ULURP, because there was the backlash against the unfettered powers wielded by Robert Moses in building roads, bridges, and other projects. The ULURP process was the people’s way of saying to their government, “Wait a minute, you cannot just make these decisions and slash through our communities.” As good and decent as roads may be, you have to ask people what they think. And there has to be a process where people get to say what they think. So our land use procedure was born.

My fear is that now that we have integrated a way for the voices of the local communities to be heard in the process – which is very good and desirable thing – that many of these voices have become advocates for community museums.

There is a notion that communities should never change - that they are sacrosanct the way they are. I think that is a troubling swing of the pendulum in the other direction. I think we should think about what that entails.

I agree that a lot of urban renewal projects of the past have been failures. But I do not think they have been failures because of eminent domain. They are failures because of bad planning.

Bad planning comes from the inability of government and the public to think and act coherently in relation to decisions about the future. Planning is about the future, and it is always at odds with the immediacy of political decision-making and land use changes that affect the people who are there right now. That is where government has to strike a balance. Everything can’t be a beauty contest. Everything can’t be decided on the popularity of a decision.

If that were the case, we would never build a homeless shelter or even a high school; we would only build elementary schools because no one wants teenagers near them.

We are seeing this in our garbage crisis. We can’t have a landfill. We can’t build marine transfer stations. And we can’t burn garbage. And we don’t recycle very well either. So I’m not sure where that takes us.

All of these things are about land use changes, and in New York, that is always a complex issue.

In many projects eminent domain is not being used to eliminate “blight” like urban renewal projects of the past, but to generate jobs and taxes into the future.

We don’t live in a country where the federal government supports all of these local uses, like schools and police. We have to come up with those dollars ourselves. I agree that there has to be constraint on eminent domain decisions, just as there has to be constraint on anything that government does. But we shouldn’t think that these projects are “bad” just because they are the work of private developers. We need to have these kinds of uses to generate jobs and taxes.

Jerilyn Perine is the president of Block by Block LLC. She served as Commissioner of New York City Department of Housing, Preservation, and Development under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Her remarks were adapted from an address at a recent event at the New York University Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and the New York Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association.

Â

Eminent Domain Revisited

Three proposed development projects in NYC that may involve the condemning of private property: Columbia University expansion, Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn, new Mets stadium in Willets Point, Queens.

Joy Chatel fears she will lose the house that has been her life for decades.

The four-story brick building on Duffield Street in Brooklyn serves as her home, a classroom where she home schools her seven grandchildren, and a business where she operates a hair salon.

Under the city’s plan to rezone and develop downtown Brooklyn, approximately 130 residences and 100 businesses, including Chatel’s, would be condemned. The city says the plan to replace them is a key element in a larger strategy to retain jobs that are leaving for New Jersey and elsewhere – and that it will ultimately benefit the residents of Brooklyn and the entire city.

Chatel argues there is more at stake than her private property. She and several other building owners in the area say that their houses are historic treasures where slaves found sanctuary as part of the “underground railroad,” a claim the city disputes.

“Oral history is all we have to prove there was an underground railroad,” she told the Daily News. “It’s not like they have a neon sign outside.”

|

Related Articles: |

In New York City, the government's power to take over private property -- eminent domain -- is a factor in so many pending development projects that the one involving Joy Chatel’s home is actually among the least-known current battles.

In Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, the real estate developer Forest City Ratner Companies has a proposal to take over private homes and businesses and replace them with the Atlantic Yards project, a basketball arena, thousands of condos, and 16 towers.

In upper Manhattan, Columbia University is considering eminent domain as an option in its efforts to expand its campus.

And in Willets Point, Queens, the city is looking to replace a 13-block area that is home to scrap metal yards and auto shops with a waterfront shopping district to complement a new stadium for the New York Mets.

New York City’s landscape has been remade over and over again, and in the process hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers have lost their private property so that the government can build roads, bridges, public housing, parks, playgrounds, and hospitals.

The concept of eminent domain – and debate surrounding the practice - dates back to the founding of the nation.

“Eminent domain means the power of the crown over his or her domain,” said Dwight Merriam, author of the book Eminent Domain Use and Abuse. “The theory is that the government really owns all of the property and can take it back whenever it wants.”

The nation’s founders tried to address the issue in the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees citizens “just compensation” when private property is taken for “public use.”

But what exactly is a “public use”?

Until the case of Berman vs. Parker in 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that it was for such clearly public physical structures as bridges, highways, schools, and train tracks.

Today, in an era when government and private developers often work closely with one another, the term “public use” is used for sports stadiums, corporate headquarters, office buildings, museums, and even shopping malls.

NEW YORK’S EMINENT DOMAIN POWERS

In New York State, eminent domain can be used to remove areas of “blight” – which means deteriorating, vacant, or obsolete buildings or even oddly shaped parcels of land. Historically, the courts and lawmakers have used the term “blight” rather liberally.

For 40 years, “master builder” Robert Moses, made use of the power to level entire neighborhoods for projects like the West Side highway, Lincoln Center, and the Triborough Bridge

An entire downtown neighborhood, including a string of small electronics shops known as "Radio Row," was demolished to make way for the World Trade Center.

In the 1980s, the city and state condemned property in Times Square to rid the area of sex shops and other abandoned buildings. Currently, on 43rd Street, the New York Times is building a new headquarters on a property obtained through eminent domain. (Read an article about efforts to remake 42nd Street over the last 50 years.)

In 2001, the state took over several buildings on Wall Street in order to make way for an expansion of the New York Stock Exchange, an idea which never became a reality.

And recently in Harlem, a dozen businesses were demolished to make way for a Home Depot.

THE KELO vs. NEW LONDON CASE

The issue of eminent domain gained a new level of attention last summer when the United States Supreme Court ruled that the government could use eminent domain to take away private property and then sell it to a private developer.

In the case, known as Kelo vs. New London, the court ruled in a 5 to 4 vote that the city of New London, Connecticut could take the property of 15 homeowners for the purpose of economic development. The city plans to transfer the property to developers who will build office space, a hotel, housing, and a riverfront esplanade.

The Kelo case has sparked new debate among legal and planning experts. (Read What the Supreme Court Ruling Means to NYC.)

Some say that while eminent domain is appropriate to build schools or hospitals, it should not benefit private developers, because it can too easily abused.

“We never hear that eminent domain should be used to take a Hyatt and build mixed-income housing,” said Susan Fainstein a professor of urban studies at Columbia University. “It is always about taking property away from poor people and give it to someone who is much better off.”

(Read Eminent Domain Benefits Developers, Not the Public by Susan Fainstein.)

Others say that if a project produces tax revenue and jobs, economic development can be considered legitimate “public purpose.”

“We shouldn’t think that these projects are `bad’ just because they are the work of private developers,” said Jerilyn Perine, who served as housing commissioner under Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

(Read Eminent Domain is a Tool, Not a Conspiracy by Jerilyn Perine.)

BACKLASH AGAINST EMINENT DOMAIN

Concern over the Kelo case has also inspired a flurry of legislation at the national and local level.

In Congress, a bill, dubbed the “Private Property Rights Protection Act of 2005, has already passed the House and is awaiting a vote in the Senate. It would withhold federal aid from states that Congress believes abuse eminent domain.

In New York, there are several bills being considered in Albany, including a package of legislation drafted by Assemblymember Richard Brodsky which would slow down local eminent domain proceedings, create an ombudsman to oversee the use of the law, and require 150 percent of market value be paid for private property that the government takes over. This week, the New York City Council will hold hearings on the subject.

And recently opponents of eminent domain claimed victory when the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the city of Port Chester, New York failed to properly alert a businessman of his right to challenge an eminent domain decision before the government seized his four buildings to make way for a convenience store. The court’s decision, some said, was a warning to local governments who may be tempted to take private property without properly notifying the people who own it.

THREE CURRENT EMINENT DOMAIN PROJECTS IN NEW YORK CITY

While the experts debate how eminent domain should be used, residents and businesses in neighborhoods where it is being considered struggle to preserve the future of their communities.

Atlantic Yards and Prospect Heights, Brooklyn

In December 2003, developer Bruce Ratner, along with Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Governor George Pataki, unveiled plans for a massive project in downtown Brooklyn, known as the “Atlantic Yards.” The latest version of the plan would build a Frank Gehry designed basketball arena for the New Jersey Nets and 16 skyscrapers with office space and 7,300 apartments.

The Brooklyn skyline as it looks today (left) and as it would look after the Atlantic Yards project (right) The Williamsburg Savings Bank in middle of image.

In order to acquire the 22 acres of land needed for the project, New York’s Empire State Development Corporation is planning to use the government’s power of eminent domain to condemn two parcels of land.

Opponents of eminent domain say that the state would take over approximately 53 properties. Local groups, which oppose the plan, say more than 330 residents, 33 businesses with 235 employees, and a 400 person homeless shelter will be displaced by the project.

And Daniel Goldstein, who works for the group Develop Don’t Destroy and lives in the area of the proposed development, warns that the definition of “blight” could apply to any neighborhood in the city.

“On any six square block in this city you will find a property that might be `dilapidated’ or `structurally unsound’ or `vacant,’ and all throughout the city nearly every property could be considered `economically underutilized,’” said Goldstein.

However some in the area, including many local officials, have praised the development, in particular for the "community benefits agreement" with neighborhood representatives that promises that 50 percent of the 4,500 rental apartments will go to low and middle-income residents, with 10 percent of these set aside for seniors. The project also sets aside 35 percent of the jobs for minority workers and another 10 percent for women.

But even some supporters of the project, like Assemblymember Roger Green, question the use of eminent domain.

“Under the definition of blight, as related to poverty or environmental degradation, this definition is not related to Prospect Heights,” Green said at recent state hearing.

Read the commentary Life in the Atlantic Yards Footprint by Daniel Goldstein.

Columbia University Expansion, Manhattanville

|

Columbia University plans to build a new campus in Manhatanville. |

Last summer, Anne Whitman, who runs a moving company out of her building on Broadway and 129th Street, received a letter from Columbia University informing her that the institution planned to build a biotech research center where her business stands.

Columbia offered to help Whitman find a single-floor building outside of Manhattan; she rejected the offer.

“Since then,” Whitman said, “it has been all out war.”

Columbia University plans to spend $5 billion over the next 25 years to build a new campus in upper Manhattan. The 18-acre complex would stretch from West 125th Street to West 133rd Street between 12th Avenue and Broadway and would house biotech research facilities, a building for its art school, student and faculty housing, and administrative buildings.

The university says the campus will create 14,500 permanent jobs in the area.

Columbia hopes to convince area residents and businesses that there is a mutually acceptable resolution. Failing that, it has suggested that the state could use eminent domain to transfer control of these properties.

However, local businesses, community board members, and students at Columbia University oppose the plan and criticize its approach to the negotiations with the community.

For some of the area’s landowners, the talk of eminent domain has poisoned negotiations.

“They say â€deal with us now or deal with the state later,’” said Whitman, who also sits on Community Board Nine. “It’s like having a gun to your head.”

Read Columbia University’s Expansion and the Threat of Eminent Domainby Joshua Brustein.

Willets Point, Queens

|

The area of Willets Point, Queens may become a shopping area next to a new Mets Stadium. |

In the 1960s, Robert Moses attempted to force out the local business owners to make way for the World’s Fair. In the 1990s, the New York Mets wanted to build a new stadium on the land. Recently, some have proposed a new stadium for the New York Jets football team or facilities for the now-defunct 2012 Olympic bid on the grounds. All of these plans failed.

Now, the city is determined to transform the area to include an attractive waterfront shopping and residential enclave, which would complement another proposed stadium for the New York Mets.

Although the city will not discuss the details of its plans at the current time, scrap metal yard owners fear that eminent domain may be used to move them out.

“Sounds to me like they’re going to pull a sneak attack,” said Richard Musick, president of the Willets Point Business Association.

There is little doubt that the area – which is riddled with large potholes and abandoned cars, and even lacks plumbing in some areas – will meet the definition of “blight.” And some local officials, like Councilmember John Liu expresses confidence that the owners “will be given fair compensation, and relocated, if necessary.”

But the scrap metal and auto shop owners say that it will be nearly impossible to find other neighborhoods that would welcome their businesses.

Read The Battle Over the Iron Triangle by Gus Garcia-Robertsfor more.

Related Articles:

Eminent Domain: What The Supreme Court Ruling Means To NYC

Condemning (For) Private Businesses

New York as a College Town

Robert Moses Revisited Â

Cleaning Up The PCBs In the Hudson River

For decades, a lot of electrical equipment contained chemicals known as PCBs -- polychlorinated biphenyls -- because they didn’t burn easily, and could act as insulation. But some 30 years ago, scientists learned that even a small amount of these chemicals could be harmful to people and other living things, such as waterways.

By that time, General Electric had been dumping PCBs into the Hudson River upstate for many years, turning 200 miles of the 315-mile-long body of water into a hazardous waste site.

"About 50 percent of PCBs in New York Harbor come from General Electric PCBs upstream," says Rich Schiafo of the environmental group Scenic Hudson.

GE stopped dumping the chemicals into the river way back in the 1970s, but for a long time, the company resisted getting rid of the PCBs that were already there, arguing that dredging them up would just make things worse.

The company also argued that it shouldn't bear the brunt of the very expensive cleanup when it didn't knowingly dump a dangerous substance into the water. However, the river falls under the federal Superfund law, which holds companies responsible for cleanups even when the discharges were legal.

After much legal wrangling, in October of this year, General Electric finally agreed with the federal Environmental Protection Agency on a clean-up plan.

Many environmentalists were not happy with the plan. Neither were some state officials; the State Attorney General’s Office found the plan inadequate, an assessment with which General Electric disagrees. But now, it turns out, at least one federal expert wasn’t happy with the plan either.

PCBs in the City

Even today, some 30 years after dumping of the chemicals ended, some 500 pounds of PCBs spill over the dam at Troy every year, contaminating wildlife and people who eat fish as far downstream as New York City.

The compound is a probable carcinogen and can damage neurological, immune and reproductive systems. PCBs have recently been linked to Parkinson's, type-2 diabetes, and non-Hodgkins lymphoma. The pollutant does not break down much over time, but it can easily spread through waterways.

Advisories warn pregnant women and children not to eat any fish out of the river. And river watchers caution everyone to avoid eating bottom feeders from the river. But warnings do not stop consumption of fish, says Robert Goldstein, senior attorney at the environmental group Riverkeeper, because some people have no other way of feeding their families.

There's an economic impact on New York City's infrastructure, too. It takes dredging to maintain the waterways, but it's costly and difficult to dispose of contaminated sediment. While New York waterways have been getting cleaner, the presence of the PCBs from the Hudson hampers the progress toward a healthy ecosystem.

A Criticized Plan

The first phase of the current plan begins in the spring of 2007, when General Electric has agreed to dredge 10 percent of the PCBs. But in a later phase, they may be able to avoid further dredging, instead capping a large area with a layer of fill. Some experts say the cap won't hold the PCBs down, that storms and even boat propellers in shallow areas will stir up the new layer, exposing and releasing PCBs into the river. More worrisome to activists is an opt-out section of the plan that could allow General Electric to do nothing at all after the first phase.

General Electric has argued in the past that dredging will actually stir up more PCBs, making the situation worse, a contention that environmentalists say has been disproven by studies of dredging projects in other states.

But now General Electric has ceased arguing and has agreed to the initial dredging, with promises to follow through with the second phase. In fact, a spokesman said, they will be undertaking the largest dredging project in the nation's history.

The Leaked Memo

A leaked confidential memo from an expert at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says the agreement General Electric reached with the federal Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Justice announced in October is inadequate -- the same conclusion voiced by environmental groups and the state attorney general's office. The memo was given to Robert Goldstein of Riverkeeper, who released it to the press. Goldstein believes that the only reason the Environmental Protection Agency would have for not releasing itself the document is that the report found the proposed cleanup wanting. "It's very suspicious," he says. "This is not some wacky wayward employee.”

The Environmental Protection Agency told the Westchester Journal-News there was no cover-up, but that the memo was "part of internal communications between consulting agencies." A spokesman also told the paper that capping would be used only after other efforts did not reduce the PCBs.

Still, critics are concerned. If the plan proceeds as now written, Goldstein proclaims, it will lead to "General Electric having the remedy which it initially proposed, which is leaving the river alone and letting it recover itself.”

Â

Community Development Television

Those who do not know public access television might take a look at Manhattan Neighborhood Network’s line-up of shows -- with names like Rappin With Rockstars, Outside My Window, Mark After Dark -- and conjure up images of a real-life Wayne’s World.

But then they do not know the story of the three women from the Lower East Side who, after taking a workshop at the Lower East Side Worker’s Center of the National Mobilization Against Sweatshops , each created her own separate first-person documentary about her health problems in the wake of September 11th.

The documentaries were first shown on one of MNN’s public access TV channels. Then they were projected onto the wall of a neighborhood church during a community organizing event. These screenings helped spur a neighborhood campaign that prompted Bellevue Hospital to provide better medical service to people suffering post 9/11 health effects, regardless of income.

MNN, which arguably runs the most prominent of the 3,000 public access television channels in the country, boasts 560 hours of local programming per week, including programs used by youth, immigrants, women and people of color to maintain an electronic dialogue with people living in Manhattan. MNN also provides grants to 25 neighborhood-based groups so that they can create video content that furthers community development agendas.

Esperanza del Barrio used one of these grants to document police harassment of street vendors. The Neighborhood Economic Development Advocacy Project, the organization I now work for, discussed how homeowners can avoid deed-theft scams on a talk show it produces on MNN.

But the opportunity for community development on public access television may change if pending federal legislation is passed –- because there may no longer be any public access television as we know it.

Shifting Regulatory Ground

Current federal law requires cable companies in New York City to provide service to all areas of the city as part of the price they pay to be given permission for ripping up streets and using city resources to lay their cable. Under “franchise” agreements that cable companies entered into with the city, cable companies must also provide television channels for public, educational and government (known as PEG) programming as well as provide these non-profit institutions with television production capacity. As a result, every borough in New York has public access television channels, facilities, equipment and operations that are paid for by the cable companies.

But this may change. In an effort to compete with companies like Time-Warner, RCN and Cablevision who provide cable services throughout the New York area, telecommunication behemoths like Verizon and SBC are looking to provide video services themselves. And to do this, they are lobbying for various laws that would make it easier for them to compete. Several of them are wending their way through Congress now.

''My bill seeks to keep limitations and regulations to a minimum in order to encourage an active, growing marketplace rather than the atrophied one we have right now,'' Marsha Blackburn, Republican Congressman of Tennessee, explained to Felicia Lee in an article about the various legislative proposals in the New York Times earlier this month. Lee added: “Advocates of the legislation say that the fears of the demise of public access are exaggerated and that some local control of franchises is written into the bills.”

But the supporters of public access are skeptical. “The introduction of broadband technology is a good thing,” said Lyell Davies, one of the 40 staff members at Manhattan Neighborhood Network. “But there’s no reason why it can’t be introduced with the same franchise requirements.”

If some of this legislation is passed, there may no longer be the conditions that ensure universal cable service, and enable neighborhood-based voices to make an impact through their use of public access.

Instead of having to report to City Hall, companies would conceivably report to the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) where there would almost certainly be less local oversight and less capacity to respond to consumer complaints.

Instead of providing service to all corners of the city, new high quality Internet, television and phone services could conceivably land in Murray Hill and the Upper East Side while circumventing Red Hook, Hunts Point, Washington Heights or anywhere else that is perceived as offering less profit potential.

And instead of having the option to tune into one of your neighbors providing information on a matter of immediate relevance to your surrounding area, you could be restricted to a strict diet of non-local, corporate-run television.

Shred To BITS?

The fact is, no one is exactly sure what direction the telecommunications legislation will go. Right now there are several competing proposals. The one that advocates are focusing their attention on is referred to as Broadband Internet Transmission Service (BITS) II and still being debated in a congressional subcommittee. Public access advocates are concerned that it entails federal, not city, oversight over franchise enforcement; places a ceiling on the number of public access channels that would be provided; dramatically lowers the amount that companies would set aside for public access operations and gives companies considerable latitude in determining what neighborhoods they may – or may not – serve.

If Verizon and SBC are given a lower bar to clear when using city infrastructure to expand their services, it would certainly prompt cable companies to demand, in the name of fair competition, that their bar be lowered as well.

But beyond the worlds of television and Internet services, the stakes are high because cable company franchises are unique and have far reaching implications for how municipalities do business with companies that use public resources. Franchise agreements speak directly to what role these companies should play in community development. Rick Junger, the director of community media for Manhattan Neighborhood Network, agrees: “The cable franchise model is one of the only one of its kind that builds in public interest and support for the surrounding community.”

Mark Winston Griffith, the co-director of the Neigbhorhood Economic Development Project (NEDAP) and a fellow at the Drum Major Institute, has been in charge of the community development topic page since its inception in 2003. Â

Housing Advocacy Wins Election, With One Exception

Whichever candidate they supported for mayor, many housing advocates counted the latest election a victory, even before Election Day – thanks to a range of housing-friendly commitments.

“Overall, it’s been probably the most significant year for housing policy advancements in the last 20 years,” said David Greenberg of the Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development. “The promises made during the campaign were really exceptional.”

Some say there was one serious exception.

From 65,000 To 165,000 New Housing Units

In his re-election campaign against an opponent who made affordable housing one of his signature issues, Mayor Michael Bloomberg promised a commitment to expand the construction of affordable housing. What began as a $3 billion plan to build and preserve 65,000 units grew to a new $7.6 billion plan to build and preserve 165,000 units. Many advocates consider this the biggest victory.

But there were others. Bloomberg has also committed to preserving some existing affordable housing that is at significant risk of becoming unaffordable, like Mitchell-Lama apartments. Very recently, after advocates rallied to focus attention on the potential loss of thousands of Section 8 apartments, the city announced that it would develop a “comprehensive assisted-housing preservation strategy” within 90 days.

During the campaign, Bloomberg made a number of decisions that pleased housing advocates. The first sign of the mayor’s new interest in housing came in April when he agreed with City Comptroller William Thompson to use $130 million in Battery Park City funds to develop a trust fund for low-cost housing, a commitment advocates had been seeking for years.

Every Week A New Initiative

In October, it seemed a week did not pass without some new initiative on housing:

• A collaboration with national charities and financial institutions to build and preserve affordable housing

• A new initiative to combat predatory lending practices

• A plan to search exhaustively across the city for underutilized land on which to build, and A plan to build affordable housing for middle income New Yorkers.

To top it off, the day before Election Day, Bloomberg announced New York/New York 3, a state and city collaboration to build 9,000 more units of supportive housing. It was widely expected but obviously timed to swing any wavering voters who somehow missed or ignored Bloomberg’s ubiquitous advertisements.

One Serious Exception – Keeping Rent-Regulated Apartments

But Bloomberg’s commitments largely avoided a significant problem in housing that he has been virtually silent about; indeed, some advocates charge he is moving backwards. The problem is the preservation of rent regulated apartments.

Some in the mayor’s administration might not understand the extent of the problem, said Michael McKee of Tenants and Neighbors, a statewide coalition. McKee said he was stunned when he read in a recent newspaper article that the city housing commissioner said that the city had had a net increase in affordable housing in recent years.

“That’s totally absurd,” McKee said. “We’ve lost 200,000 rent regulated apartments in the last 10 years. We’ve lost 11,000 Section 8 apartments and we’ve already lost 40,000 Mitchell-Lama rentals.”

The city did not respond to a request for comment.

The mayor’s lack of action on preserving rent regulated apartments, which account for roughly a third of all rental apartments in the city, is “deadly,” McKee said: “It will be absolutely deadly and we will all pay for the failure of Mike Bloomberg to do something about this.”

Jenny Laurie, executive director of Met Council on Housing, agreed.

The loss of rent regulated apartments has been fueled by a change in the rent regulation laws in 1997 that allowed landlords to decontrol apartments when those apartments reach $2,000 monthly rents as they are vacated. They can also decontrol those apartments if the household income is $175,000 or greater for two years and the rent reaches $2,000.

Getting a rent stabilized apartment’s rent up to $2,000 seemed unlikely, perhaps, in 1997. But over his first term, Bloomberg’s appointees to the Rent Guidelines Board have allowed rents to increase significantly as landlords claimed operating costs had skyrocketed.

“You’re going to see the steady erosion through the vacancy decontrol provisions and if we continue to have high guidelines, you’re going to see steady erosion of tens of thousands of affordable housing units a year,” Laurie said.

Bloomberg’s main emphasis has been on building new affordable apartments, which is just one part of addressing the affordability problem. Saving what already exists is the other part.

“He’s putting drops of water in the top of the bucket while there’s a big hole in the bottom of the bucket,” Laurie said.

Advocates were hopeful once that Bloomberg was committed to addressing the loss of rent regulated apartment. In his first term, he supported repeal of the Urstadt Law, as I’ve written about before.

Simply put, the Urstadt Law prevents the city from passing any law stricter than the state housing laws. That effectively ties the city’s hands on enacting legislation to address rent regulated apartments. Bloomberg flipped on his commitment to repeal the Urstadt Law during his reelection campaign.

Hope Elsewhere

There may be some reason for optimism, however, on two other fronts – the New York City Council and the New York State Legislature. In contested elections for City Council, pro-tenant candidates won in races across the city. Advocates are working now to ensure that the next City Council speaker is pro-tenant, too. At the state level, anti-tenant Republicans lost seats.

“Whether we change Bloomberg’s mind on home rule, it may be that in 2006 or 2008 the state government will be controlled by Democrats and the state will return to localities the right to legislate over rent regulations,” Laurie said.

McKee said he was “very skeptical” about Bloomberg’s many promises during the campaign.

“I’ve been through this too many times,” he said. “I think it’s commendable that the Bloomberg administration has undertaken efforts to create new housing. I think it would be more commendable if they also expended some political capital and got involved in the fight to preserve the affordable housing we have.”

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â

Atlantic Yards: Through The Looking Glass

The Atlantic Yards story in Brooklyn is becoming a bit like the tale of Alice in Wonderland. In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, everything appears backwards, Alice is caught up in a giant chess game of powerful players over which she has no control, and the characters she meets talk nonsense.

The planning for Atlantic Yards is all backwards. Normally, government does a plan for the area, then looks at the potential environmental impacts of the plan, decides what to do, and then either does it or puts it out to private developers to bid on. In Atlantic Yards -- and increasingly in other megaprojects throughout the city -- it is just the reverse. First a private developer does a plan for the area, gets government officials to back it, then does an environmental impact statement, and in the process of looking at the environmental impacts all of the big planning issues that were never addressed in the first place come up for discussion. But the people who live and work in the area and will be most affected by the plan have the least to say about it.

The Atlantic Yards project was born two years ago when Forest City Ratner, one of the nation’s largest developers with a virtual monopoly on downtown expansion, proposed what now appears to be the largest-ever project in the borough. The latest version of its project includes a professional basketball arena, 7,300 units of housing, and over 600,000 square feet of office space. The developer then got Governor George Pataki, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz to voice full public support for the proposal. Then the governor unleashed the State of New York’s Empire State Development Corporation, which he controls, to place at the developer’s disposition the government’s powers of eminent domain so that privately-owned land on the site could be assembled.

With the Empire State Development Corporation at the head of the pack, Forest City Ratner could also avoid going through the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Process (nicknamed, ULURP), which would force it to face votes by the local community boards, borough president, City Planning Commission, and City Council. The developer needed to get the right to build over the rail yards owned by the Metropolitan Transit Authority, but since this is a state-run agency controlled by the governor, a hastily-planned Request for Proposals was put together so the developer could be guaranteed the rail yards. And $200 million in public subsidies were thrown in to sweeten the deal.

Finally, two years after the project was proposed, the Empire State Development Corporation decided it would start the legally-required environmental impact study. Earlier this year this corporation issued a draft scope of work that outlined all the things they proposed to study, including potential impacts on traffic, air quality, open space, and neighborhood character, including the effects on the economic and social livelihood of the surrounding Brooklyn communities. Comments on this scope of work were due to the corporation in late October, and the agency is expected to issue what’s called a draft environmental impact statement in the early part of next year.

On October 18, over 800 people packed an auditorium in downtown Brooklyn to tell the Empire State Development Corporation about all the potential impacts that the developer’s plan could have -- many more than the agency had proposed to study. This hearing was a crucial turning point for two reasons. First, it tarnished the image of inevitability and consensus that the developer had cultivated around the project. It was clear even to the press that had treated Forest City Ratner with kindness that there were large sections of the community that had serious doubts about the scale, design, and cost of the project. Secondly, it pointed out the need for careful, detailed planning for development of the Atlantic Yards site so that it would knit that development into the fabric of Fort Greene, Prospect Heights, Park Slope, Clinton Hill and other neighborhoods. Ratner’s Metrotech and Atlantic Terminal developments had already shown that the company, which invaded Brooklyn from Ohio, likes to do suburban-style malls. There was reference at the hearing to the Unity Plan, developed over a 15-month period through a series of community workshops, and the Extell Plan, rejected by the MTA without a hearing.

So now we’re back to planning, which should have been the starting point. The three community boards affected by the project and community-based organizations under the umbrella of the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods , among many others, seem to be raising all the fundamental questions that should go into the planning process but that were avoided during two years of cheerleading. There seems to be a fair amount of sentiment for developing something over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s rail yards, including affordable housing, but only a thorough planning process can produce consensus over what it should be. Community benefit agreements put together by the developer and several local groups might be useful if they too were part of a broader community planning process.

Is Environmental Review Backwards?

In this looking glass world, the environmental review process has been spun around and is now backwards. The laws establishing environmental review procedures by the city and state were designed to provide decision makers – the governor, mayor and borough president, for example – with information about potential impacts of new projects so that they could make informed decisions. Government could then determine what measures would have to be taken to mitigate the impacts before they approved or disapproved the project. But with Atlantic Yards, government leaders have already made up their minds, and given away the store. The environmental impact statement could very well end up as a useless exercise that satisfies no one except the project sponsors. Or it may turn out like the nonsensical poem, Jabberwocky, that Alice discovered in the Looking Glass World, filled with unintelligible jargon. Its multiple volumes will be more than your average community resident or business person can digest in the course of a normal lifetime. If past practice is any indicator, they will barely have enough time to get past the introduction before the state agency moves to put the final rubber stamp on the project.

The most troubling part of the Atlantic Yards project is that it seems to be part of a much bigger reversal in the public process set up to handle development proposals. The same thing happened with the Jets Stadium on the West Side of Manhattan, the rebuilding of lower Manhattan, and the Brooklyn Bridge Park. State authorities under the governor’s control make deals with private developers, then use their powers to override local land use procedures. And compliant local politicians pave the way, undermining the few regulatory tools they have at their disposal to empower their own constituents in the planning process. And while these mega- developers go through the back door and benefit from the magic mirrors, the thousands of neighborhood developers that are the backbone of local improvement have to follow the rules and go through ULURP.

New Yorkers from the boroughs outside Brooklyn who think Atlantic Yards has nothing to do with them should think twice. Atlantic Yards could be the place where the mirror gets shattered, the King is captured, and Tweedledee and Tweedledum have to walk away in shame.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.Â

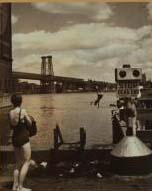

Clean Enough To Swim In Again?

|

|

If you happen to fall in to the New York Harbor, the Hudson, the East River, or Jamaica Bay, you need not fear bacterial infections or diseases from industrial pollution, according to a draft of a yearly report from the city's Department of Environmental Protection. Unless you fall in after a storm.

In fact, despite their sullied reputation, the quality of most of the waters around New York City has been pretty good in recent years. Since passage of the nation's Clean Water Act of 1972 and improvements in the city's handling of sewage in the 1980s, city waterways have improved. Perfection is a long way off. But for a city that disposes of 1.9 billion gallons per day from wastewater treatment plants in New York waters (in 2003) and lives with the effects of pollution from years gone by (such as PCBs dumped upriver in the Hudson), the waters are relatively clean.

"During the last two decades, water quality in New York Harbor has improved to the point that the waters are now commonly utilized for recreation and commerce throughout the year," says the Department of Environmental Protection’s draft report. Charles Strucken of the department says they are still working on the final report about New York water quality (not drinking water).

One problem that continues to plague the waterways stems from storm water and sewage being combined. When it rains, the pipes and water treatment facilities can't handle all of the waste. Sewage is sometimes discharged directly into the waters.

The storm runoff also brings pollutants from the land and streets, such as motor oil, pet waste and pesticides, says Maureen Dolan of the Citizens Campaign for the Environment.

In anticipation of the sewage discharges, the city closes beaches even before storms. In the summer of 2004, she reports, 12 beaches were closed, for a total of more than 400 days. The Bronx experienced the most with 289 beach closure days for eight beaches. Dolan expects similar figures for 2005 (results have not yet been tallied). The technology is there to keep the sewage out of the waterways. "In 2005 we should not have sewage flowing into the beaches," says Dolan.

IMPROVEMENTS

"Right now looking out my window, I can see down a depth of eight feet," says Dan Mundy, founder of Jamaica Bay EcoWatchers. He became active in the mid-1990s, when he saw conditions in the bay where he lives deteriorating. Since then, the waters have improved. Though 300 million gallons a day of treated sewage water comes into the closed estuary adjacent to JFK Airport, Jamaica Bay is holding its own, says Mundy. "The bay is swimmable. Fishing is great."

Swimming and fishing are all right in the Hudson and East Rivers, too. "The water is cleaner now than it was ten years ago -- and by some estimates 100 years ago. It is perfectly safe and sanitary to swim in it," says the Manhattan Island Foundation, which sponsors an annual swim around Manhattan.

Don Riepe, Jamaica Bay Guardian for the American Littoral Society, which looks after shorelines , says eating fish such as striped bass, bluefish and other game species from the waterways is generally safe. Because of pollutants that rest on the bottom, he recommends staying away from bottom feeders. "Things like American eels that live in the bottom of the bay you don't want to eat. You don't want to eat shellfish. Everything else, use common sense. Don't eat a lot, and make sure it's cleaned properly." He recommends taking off the skin and fat layer because that's where "pesticides and heavy metal accumulate."

"Floatables" (Litter And Debris)

Waterways around New York generally look better this year, reports Barbara Cohen, New York Beach Cleanup Coordinator for the American Littoral Society, which sponsors a statewide beach cleanup day each September. Volunteers collected 73,408 pounds of debris around Manhattan alone last year. Though figures haven't been compiled yet for the 2005 cleanup, Cohen says that this year "beaches seem to be cleaner than in the past."

The debris, what those in waste treatment call "floatables," contributes to the look and to the physical well-being of waterways. "The main source of floatables is street litter, which ends up in the city's storm drains (catch basins) and sewers," reports the city's environmental department Web site. Plastic accounts for 42 percent, paper and polystyrene for some 26 percent apiece.

"In New York, cigarettes, caps and lids, and food wrappers accounted for nearly half of all the debris items collected," reports the American Littoral Society about their 2004 cleanup.

Debris is a problem for the small waterways, too. In the cleanup this year, Cohen says, "Coney Island Creek is a bad area in terms of litter and other debris."

Debris is one of the Harlem River's problems as well, but as a tributary of the Hudson, it also suffers from the same PCB contamination that the Hudson does, reports the Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems at New York University's Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.

POLLUTION PERSISTS

The worst problem for the tributaries and "small embayments" are bacteria from the storm runoffs, says the Department of Environmental Protection's draft report. "Some of these tributaries are the only remaining areas where bacterial counts exceed standards on a regular basis."

The report details pollution from industry and storm water discharge in Newton Creek, which marks the border between Queens and Brooklyn and flows into the East River. Improvements to the creek are scheduled for completion in 2007.

The infamous Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn remains polluted and even smelly at times for the same reason, reports Crain's New York Business. Developers who want to build housing along the canal are reportedly daunted by the city's recent postponement of the canal's cleanup.

|

|

The Bronx River also faces storm runoff that pollutes other New York City waterways. That's a problem for Jamaica Bay, too. There are still algae blooms on occasion, caused by an excess of nitrogen from the runoffs. When the algae die, it sucks oxygen out of the water, and fish leave or die. "The bay is also losing 50 acres of marshland a year, and no one has figured out why so far," Mundy says. Shell fishing is still prohibited.

Still, Mundy says in the past four years, he has become optimistic. The Department of Environmental Protection is building huge holding tanks to handle the overflow. They are spending hundreds of millions of dollars on capital projects.

Mundy and others who have watched the water for a long time are convinced that the beauty of New York's rivers and harbors is not just on the surface.

Related Articles

The Waters of the Harborby Peter Fleischer, about the Department of Environmental Protection's 2002 water quality report.

Earth Day by Eric Goldstein, including a look at the waterways.

Congress Acts to Protect New York's Water by Congressman Ed Towns, about state water table legislation (for drinking water)

Â

Subsidizing Slumlords

Earlier this year, Housing Here and Now, a coalition of housing advocacy organizations, released a list of the city’s top ten worst landlords and set up a Web site to identify others. Now, the coalition has taken its campaign a step further. They issued a report that found that one quarter of buildings that receive rent subsidies from the city Department of Homeless Services and the Human Resources Administration have been cited by another city agency for serious violations, such as no heat and rat infestations.

The city’s record of paying landlords for substandard apartments is, unfortunately, not very good. By contrast, the federal Section 8 subsidy has rigorous standards for apartments it pays for. The agencies that administer Section 8 -- the housing authority, the city and the state -- routinely cut off the subsidy when an apartment fails inspection.

But the Section 8 program, disliked by the Republicans in Congress and the Bush administration, is on its way out. Last year, the mayor took a controversial step in light of Section 8’s troubles: The city created a new subsidy called Housing Stability Plus.

As I’ve written before, many advocates called this subsidy “Section 8 lite” when it came on line earlier this year. They considered it inferior in many respects, not least of which is because it declines by 20 percent each year until the fifth year when it ends entirely.

The city has yet to give a satisfactory response to how someone on public assistance is going to cover a 20 percent annual rent hike. At best, the city appears to be pinning its hopes on some strange ideas -- that landlords will not seek to evict tenants who do not pay rent or that tenants will somehow find the income.

Beyond this, however, in administering the new subsidy the city leans toward the more lenient housing quality standards that it uses for people on public assistance rather than those used by Section 8. Last year, the public advocate released a report of homeless people who received the subsidy living in apartments with significant violations of the city’s housing code. In its own report, Your Tax Dollars At Work: How NYC Subsidizes Slumlords, Housing Here and Now found more of those tenants.

“We share their concerns for client safety and commend them on the thoughtful report,” Jim Anderson, a spokesman for the city’s Department of Homeless Services, said of Housing Here and Now in a statement. “We are confident in the integrity of the apartment inspection process -- and, as the authors show, the vast majority of the certified apartments exist in buildings that meet their standards."

Many of the violations that do exist, Anderson maintained, were in the buildings, not in the individual apartments being subsidized. "We don’t think the appropriate response is to bar homeless families from competing for decent apartments in buildings that have violations, prolonging their shelter stays in the process....”

Housing Here and Now’s lead organizer said the city should simply not give priority to slumlords for the subsidy.

“In the case where there is a landlord with a sketchy record, that landlord should not necessarily be denied but they shouldn’t be at the top of the list,” said Chloe Tribich of Housing Here and Now.

The city has also launched an “aggressive” effort “to address unsafe building conditions through code enforcement,” the spokesman said. At the very least, they will have a good idea of where to start thanks to the advocates’ report.

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations. Â