Wall Street Bonus Babies

Every year at this time, wine sellers take out their $500 bottles of Bordeaux; car dealers expect a rush on $100,000 Bentleys, Porsches and Lamborghinis; real estate agents witness perfectly normal-looking people plunking down several million dollars -- in cash -- to buy an apartment. “I call them ego apartments,” one agent told the New York Sun.

It is bonus time on Wall Street, and this year in particular, there are some very happy people, from luxury suit salesmen to municipal tax collectors; the total estimated amount of bonuses(In PDF format) given out this quarter for work done in 2004 is expected to be the second biggest in history -- $15.9 billion.

Officially, the average bonus on Wall Street is $100,000. But this is an example of when statistics bear little relationship to reality. The truth is that there are a relative handful of people who work on Wall Street who get bonuses, and what they get can be astronomical.

So who are the Wall Street bonus babies?

Overwhelmingly they are involved in securities and investments, according to an analysis of Census and other data. They either help make markets, make sales, make deals, or give advice – brokers, investment bankers, traders, financial analysts, financial advisers, portfolio managers, and a few chief executive officers.

Working on Wall Street does not guarantee a high income, as most any Wall Street secretary, food service worker, or techie can attest. So can the average auditor and accountant; one-quarter of the 11,000 auditors and accountants who work in the investment and securities industries in Manhattan make $38,500 or less; the worst-paid brokers make little more than that:

|

Income of Financial Occupations in Investment and Securities in Manhattan

|

||||

| Occupation |

Number

|

Bottom Quartile

|

Median

|

Top Quartile

|

| CEO |

3,652

|

$75,000

|

$120,000

|

$347,000

|

| General Manager |

2,111

|

$47,000

|

$95,300

|

$130,000

|

| Financial Executive |

8,782

|

$60,000

|

$100,000

|

$347,000

|

| Account, Auditor |

11,068

|

$38,500

|

$62,004

|

$100,000

|

| Financial Analyst |

6,074

|

$40,000

|

$81,000

|

$321,000

|

| Personal Financial Analyst |

8,289

|

$44,500

|

$80,000

|

$321,000

|

| Other financial Occupation |

1,096

|

$46,000

|

$70,000

|

$321,000

|

|

Broker

|

42,039

|

$40,000

|

$80,000

|

$321,000

|

| Based Upon 2000 Census Data | ||||

The median income for the 23,000 highest earners on Wall Street – the ones most likely to get a year-end bonus – is so high that the U.S. Census Bureau stops counting after $347,000. For 2004, merger specialists expect to receive total compensation on average of $900,000, while commodities traders in oil and gas can expect to earn $1.3 million or more. Compare this to the median income for all other earners in the securities and investments industries – a mere $60,000. (The median income for all other workers in Manhattan was $35,000).

Bonus babies (many far from babies) are much more likely to be white, male and married, as the accompanying table makes clear. They are virtually all college graduates.

|

Workers in Financial Jobs in Securities and Investment Sector and Others in Manhattan

|

|||

|

Top Earners

|

Other Earners

|

Other Manhattan Workers

|

|

| Median Income |

More Than $347,000

|

$60,000

|

$35,000

|

| % White |

93

|

79

|

59

|

| % Hispanic |

2

|

6

|

18

|

| % Married with Spouse |

75

|

46

|

44

|

| % Male |

86

|

65

|

57

|

| % Born in United State |

84

|

80

|

63

|

| % At Least 4 Years College |

93

|

79

|

48

|

|

Based Upon 2000 Census Data

|

|||

And they almost all work in Manhattan. Pay in the financial services industry in Manhattan towers above that in all the other 3042 counties in the United States. Manhattan is the center of this whole industry. During the first quarter of 2003, the average wagespaid in that industry in Manhattan was $5,680 per week. Fairfield County in Connecticut, which includes Greenwich, was a distant second at $1,492.

The annual bonus can easily be 90 percent of the average investment banker's or bond trader's total annual income. An investment banking analyst right out of college will make about $65,000 salary, plus a $35,000 bonus, while an associate just out of business school might make $85,000 in salary and $115,000 in bonus. At the other end of the career ladder is Lloyd Blankfein, president and chief operating officer of Goldman Sachs, who made $20.1 million in 2003 -- only $600,000 of which was salary. That same year, E. Stanley O'Neal, chief executive of Merrill Lynch, made $500,000 in salary, but received a bonus of $13.5 million.

Since so much of their compensation is based upon bonuses, some of these highly paid executives and financial professionals have very volatile incomes. One year they make their base and several times that in bonuses; other years the bonuses may be much less than their base salaries, and during real down turns (such as existed in 2000 through 2002). they may face lay-offs.

The bonus-setting process is highly political and largely secret. Each group or division in a firm argues for bonuses based upon their "contributions" to earnings; then each professional argues for his or her share. So the relative size of each bonus indicates an employee's worth, while the money can affect his or her life-style immensely.

Members of the financial community are quite close mouthed when it comes to compensation, yet using the information we have we can make an educated guess about the size of an average or median bonus for a high earner in this sector. Let us assume that the 23,000 high earners split about three quarters of the $15.9 billion of bonuses. This would mean that the median bonus on Wall Street would be approximately a half a million dollars. But even here, one would expect a great deal of inequality. Some will make multi-million dollar bonuses; others will have to settle for a few hundred thousands. So these 23,000 very privileged New York workers really did find their fortune on Wall Street.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Repealing the Urstadt Law

Ask most housing advocates what one move would improve the lot of tenants in New York City, and they would answer: Repeal of the Urstadt Law. The state law, which then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller pushed through in 1971, and which Governor George Pataki strengthened in 2003, is named after Rockefeller’s housing commissioner, Charles Urstadt. For more than three decades, it has effectively handcuffed the city when it comes to dealing with the main problems facing housing here -- rents and evictions.

That is because the law largely took control of rent regulation out of the hands of the city government and gave it to the state legislature. The legislature, a body with many representatives from upstate districts that have few renters, has weakened rent regulation laws year after year. Changes in the rent regulation laws have resulted in what some estimate to be more than 100,000 rent stabilized apartments in New York City becoming “decontrolled” – the rents hiked up to whatever the landlord wants to charge.

Advocates say repealing the Urstadt Law would give the city the power to keep rents affordable.

“In my mind, it is the only way to reverse the crippling of the rent and eviction protections that we’ve seen at the hands of the state legislature,” said Kenny Schaeffer, vice chair of the Metropolitan Council on Housing. “Right now, the City Council’s hands are tied. The rent stabilization laws have had so many holes poked in them by the state legislature that they’re dying a death of a thousand cuts.”

Revoking the city’s control over rent laws was a strategic political move Rockefeller made to help in his re-election campaign, recalled Michael McKee, associate director of Tenants and Neighbors. As a result, it led to four sets of laws that fill hundreds of pages noted for their complexity, if not incomprehensibility.

There are state rent control laws and city rent control laws, state rent stabilization laws and city rent stabilization laws. Over the years, these have been revised and sometimes rewritten. Some of the laws are specific to New York City while others apply to smaller cities. The laws have spawned thousands of pages of commentary and doubtless assured the employment of many attorneys, legal journalists and, yes, even housing advocates. It takes years to figure out just what the different laws say and how they are applied in practice

Reclaiming home rule over rents and evictions would make understanding those laws easier, McKee said, in addition to making housing advocates’ work less onerous.

“We have a rent regulation system that makes no sense at all,” McKee said. “It’s a patchwork quilt that no one understands.”

Repealing the Urstadt Law would not create a “paradise” for tenants, McKee said, but would help them be more effective.

“Tenants will still have to organize and put pressure” on elected officials, McKee said. “But at least we won’t have to fight a two-front war. Especially in years where the (state’s and city’s) laws sunset at the same time. From an organizers point of view it’s a nightmare. People say, â€I thought the laws just got renewed, why do I have to go to Albany?’”

Political considerations could make a repeal of the Urstadt Laws possible this year, Schaeffer said. Record homelessness, high rents and the continued loss of rent regulated apartments have put affordable housing firmly on the political agenda and the mayoral election will only increase the pressure for solutions.

At the same time, Democrats scored significant victories in last November’s elections to diminish the Republican majority in the State Senate. Those victories have led Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno to compromise more readily on progressive issues. A higher minimum wage and less draconian drug crime punishments are some of the results of the new political realities for Bruno.

While Mayor Michael Bloomberg has said in the past he supports a repeal of the Urstadt Law, McKee noted that he was silent when Pataki strengthened the law in 2003. Tenants have not forgotten, he said.

“Even when Pataki pushed, there wasn’t a squawk from the mayor, he didn’t say a word,” McKee said. “And we are fed up with this posturing in City Hall.”

People gather at City Hall February 2 in support of affordable housing and in protest of the Urstadt Law. |

A rally planned for Feb. 2 is meant to send that message loudly and clearly to politicians. The rally on Brooklyn Bridge will call attention to affordable housing, and specifically three actions that would allow the city to address the problem: Making sure that a significant portion of Battery Park Authority funds actually finance affordable housing construction as originally intended; Persuading the city to adopt inclusionary zoning that would allow developers to build higher density developments in return for setting aside a percentage of the units for affordable housing; And calling for a repeal of the Urstadt Law.

Joe Lamport is the assistant director of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing Court, a coalition of community housing organizations.

New York Lawyers: A Profile

Think “New York Lawyer” and it is easy to picture a partner who earns $1.391 million a year (which was the average compensation for a partner in a top New York law firm in 2003, according to the American Lawyer). Even first-year associates – people just out of law school – can make up to $150,000 a year. The top earners make more than anywhere else in the United States, and there are so many more of them in New York. The largest New York firm, for example -- Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom -- employs some 1,700 attorneys, 350 of whom are partners who each made $1.6 million last year. Is it any surprise that New York is often seen as the major center of the legal profession.

But there were 57,000 practicing lawyers in New York City in the year 2000, according to the U.S. Census, and, as several recent stories make clear, they are not all doing the same thing. The Legal Aid Society, the “main legal provider for New York City’s poor,” as it was described in a recent New York Times article detailing how it was recently saved from bankruptcy, employs 1,396 people (not all of them lawyers of course). There are many other non-profit legal service providers; three recently received a court victorythat will allow them to serve their poor and immigrant clients more effectively, according to Newsday – making it easier, for example, to file class action lawsuits.

So what would a portrait of New York lawyers really look like?

WHERE DO NY LAWYERS LIVE?

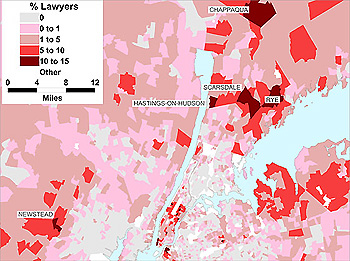

Nearly half of all New York lawyers work in Manhattan.Only a quarter live there.

So where do the rest live?

More than half live in the suburbs. Chappaqua, Hastings-on-Hudson, Rye and Scarsdale have high concentrations of lawyers, as does Newstead, New Jersey. In Long Island, the North Shore (Great Neck and Manhasset) and South Shore (Hewlett Bay Park and Hewlett Harbor) of Long Island have relatively high concentrations.

|

Where Lawyers and Other Work in NYC Metro Area

|

||||

|

Where They Live

|

Where They Work

|

|||

|

Lawyers

|

All Other BA +

|

Lawyers

|

All Other BA +

|

|

| Outside of Area |

1.3%

|

2.2%

|

11.6%

|

13.5%

|

| Suburbs |

58.2%

|

64.1%

|

31.2%

|

42.8%

|

| Outer Boroughs |

15.3%

|

20.4%

|

9.6%

|

14.2%

|

| Manhattan |

25.2%

|

13.3%

|

47.7%

|

29.6%

|

| Total |

118,810

|

3,361,608

|

117,850

|

3,308,860

|

In New York City, there are large concentrations of lawyers in areas in the Upper West and to a much greater extent on the Upper East Side, downtown near the river and Battery Park, as well near Astor Place. In Brooklyn, there are large concentrations in Brooklyn Heights and somewhat lower ones in Park Slope.

Interestingly, the highest concentration of lawyers living in New York City is in Forest Hill Gardens, a community with private streets just beyond the LIRR tracks and east of 71st Street in Queens.

WHAT IS THEIR ETHNIC MAKEUP?

Of the 57,000 lawyers practicing in New York City in 2000, 87 percent were white; only six percent were black. Compare this to all New Yorkers who have at least a B.A. and are employed – 70 percent of these are white, and 12 percent black.

Thirty-six percent of New York lawyers are female (compared to 47 percent of employed college graduates as a whole). Only four percent of lawyers are Hispanic (compared to eight percent of employed college graduates as a whole.)

Eighty-seven percent of New York lawyers have always lived in the United States, and 84 percent speak English at home. Over 60 percent of lawyers are married and living with their spouses (compared to 50 percent of the employed college graduates as a whole), and 62 percent own their own residences. New York lawyers may be diverse, but it is clear they are more affluent than average.

LAWYERS’ INCOMES

The median income for New York Lawyers in 1999 was $100,000. That means that half made more and half made less. This vastly exceeds the $46,000 median income for other employed college graduates. More recent data suggest some modest increases for both lawyers and others. In the 1990s for the US as a whole, lawyers median income exceeded that of doctors for the first time. This is also true in New York City, where the median income of physicians is $80,000.

One-quarter of all lawyers made $280,000 or more, while one-quarter made $50,000 or less. The median income of male lawyers is $107,000; for female lawyers it is $75,000.

|

Earnings of Lawyers Working in NYC

|

||||

|

Number

|

Bottom Quartile

|

Median

|

Top Quartile

|

|

| All Lawyers | 51,180 | $50,000 | $100,000 | $280,000 |

| Self-employed, not incorporated | 13,844 | $40,000 | $95,000 | $280,000 |

| Self-employed, incorporated | 4,792 | $70,000 | $120,000 | $347,000 |

| Private firm employee | 29,822 | $55,000 | $100,000 | $160,000 |

| Non-Profit org employee | 1,497 | $41,000 | $65,000 | $77,000 |

| Federal govt employee | 139 | $50,000 | $58,000 | $58,000 |

| State govt employee | 385 | $35,600 | $45,000 | $77,000 |

| Local govt employee | 701 | $47,000 | $73,000 | $80,000 |

| Male | 35,478 | $57,000 | $107,000 | $280,000 |

| Female | 15,702 | $43,000 | $75,000 | $125,000 |

Lawyers in the private sector earned the most. Among those who are self-employed but incorporated, lawyers with their own practice, the median income was $120,000 and those in the top quarter made at least $347,000. Those who are self-employed, but not incorporated made somewhat less, while those working for private employers, including law firms, had a median of $100,000 and those in the top quarter made at least $160,000. Such lawyers are predominantly associates not partners of law firms, so they earn salary and bonuses but do not get a share of the profits. The self-employed lawyers may more likely be in such areas as divorce, personal injury and class action, where the practices are relatively small, but the possibility of a multi-million dollar payday exists.

The census did not release information about the actual earnings of those making more than $627,000. Such respondents were “top-coded,” their income was reduced to a figure that represented the cut-off for the top three percent of all earners. The American Lawyer does published data on the top 100 law firms in the United States, the Am Law 100. Using those data, one finds that the 3,276 partners (about seven percent of New York’s lawyers) of the 23 New York firms making that list split about $4.6 billion dollars in 2003, for an average compensation of $1.391 million dollars. The average was highest at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen and Katz, where the 78 partners averaged $2.585 million. Indeed, 18 of the top 23 firms had average partner compensation in excess of a million dollars.

|

New York Law Firms In The American Lawyer 100 in 2003 (Adapted from the American Lawyer, July 2004)

|

Average Compensation

Per Partner |

Total Partners

|

| Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz |

$2,585,000

|

78

|

| Cahill Gordon & Reindel |

$2,375,000

|

62

|

| Cravath, Swaine & Moore |

$2,080,000

|

77

|

| Simpson Thacher & Bartlett |

$1,940,000

|

145

|

| Davis Polk & Wardwell |

$1,925,000

|

146

|

| Sullivan & Cromwell |

$1,900,000

|

152

|

| Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison |

$1,840,000

|

101

|

| Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy |

$1,725,000

|

120

|

| Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom |

$1,600,000

|

350

|

| Schulte Roth & Zabel |

$1,525,000

|

66

|

| Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft |

$1,480,000

|

92

|

| Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton |

$1,445,000

|

161

|

| Willkie Farr & Gallagher |

$1,410,000

|

116

|

| Weil, Gotshal & Manges |

$1,340,000

|

251

|

| Debevoise & Plimpton |

$1,260,000

|

119

|

| Shearman & Sterling |

$1,160,000

|

231

|

| Kaye Scholer |

$1,040,000

|

130

|

| Proskauer Rose |

$1,040,000

|

154

|

| Dewey Ballantine |

$980,000

|

150

|

| Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson |

$980,000

|

126

|

| Stroock & Stroock & Lavan |

$920,000

|

92

|

| Chadbourne & Parke |

$880,000

|

109

|

| Wilson, Elser, Moskowitz, Edelman & Dicker |

$445,000

|

248

|

|

$1,391,039

|

3276

|

Those lawyers working for the government or a non-profit agency earn substantially less. Indeed, the median income for lawyers employed by non-profits was $65,000. For those working for New York State, the median was $45,000; for those working for the city government, it was $73,000; for those with the federal government, it was $58,000.

Included among these lawyers are the public defenders, the legal aid lawyers, the prosecutors, as well as those working for various public interest entities, such as the ACLU and others.

So, clearly, a monolithic image of the New York lawyer is just as inaccurate and unfair as most lawyer jokes. Of course, the trouble with lawyer jokes is lawyers don't think they're funny, and nobody else thinks they're jokes.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

Bush Does Better, and Other Election Results In NYC

Among the thousands of Americans posting pictures of themselves apologizing to the world for the election of George W. Bush on SorryEverybody.comare surely a sizeable number of New Yorkers. After all, three quarters of the voters in New York City, we have been told again and again since November 3, pulled the lever for John Kerry for president. But this, as it turns out, may be even less than the slim consolation it has been for Kerry supporters this month. The fact is, Bush did better in New York City than he did four years ago.

Bush had a total of 544,359, or 24.5 percent of the vote in New York City. In 2000, he had only 18.2 percent.

Kerry received 74.3 percent; in 2000, Gore received 77.9 percent. The percentage for Bush increased in every borough except Manhattan. Bush actually received the majority of voters in Staten Island (56.7 percent). In 2000, Gore received the majority.

Indeed, looking at all 3142 counties in the United States, Staten Island had the 20th highest increase in support for Bush. Brooklyn had the 105th highest increase.

Nationally, Bush did better among every category of voter except the young and very old (over 85.) Why should we expect New York City to be any different?

|

Election Results 2004

|

||||||

| Borough | Kerry | Bush | Nader | Others | Kerry 2004 vs. Gore 2000 |

Bush 2004 vs. Bush 2000 |

| Bronx |

82.3% |

16.7% |

0.7% |

0.3% |

-3.9% |

4.9% |

| Kings | 74.1% |

24.8% |

0.8% |

0.2% |

-6.5% |

9.1% |

| New York | 81.7% |

16.6% |

1.4% |

0.3% |

1.9% |

2.4% |

| Queens | 70.8% |

28.0% |

0.9% |

0.3% |

-4.2% |

6.0% |

| Richmond | 42.1% |

56.7% |

0.8% |

0.4% |

-9.8% |

11.7% |

| Total | 74.3% | 24.5% | 1.0% | 0.3% | -3.6% | 6.2% |

|

Election Results 2000

|

||||

| Borough | Gore | Bush | Nader | Others |

| Bronx |

86.3% |

11.8% |

1.4% |

0.6% |

| Kings | 80.6% |

15.7% |

3.2% |

0.5% |

| New York | 79.8% |

14.2% |

5.5% |

0.5% |

| Queens | 75.0% |

22.0% |

2.5% |

0.6% |

| Richmond | 51.9% |

45.0% |

2.5% |

0.6% |

| Total | 77.9% | 18.2% | 3.3% | 0.5% |

Turnout

Much has also been made of the higher turnout – that whatever the results of the election, the high turnout showed that democracy works. It is true that turnout did go up a bit – 46.5 percent of those eligible, compared to 45 percent in 2000 – and it increased in every borough but Staten Island. The fact is, though, that, as usual, more New Yorkers who are eligible to vote stayed home than voted; New York City is still a non-voting town. The reports of long lines at the polls seem to be the product of early voting or a badly administered election, rather than a massive increase in turnout. And, remember, many more people go to the polls in a presidential election than in any other race.

|

Turnout Estimates 2002 and 2004

|

||||||||

| Borough | Vote 2004 | Est Citizen Voting Age Pop 2004 | % Turnout 2004 | Total vote | Est Citizen Voting Age Pop 2000 | % Turnout 2000 | Change in Votes | Change in Turnout |

| Bronx |

316,264 |

767,291 |

41.2% |

308,048 |

770,989 |

40.0% |

8,216 |

1.3% |

| Kings | 631,774 |

1,414,480 |

44.7% |

617,105 |

1,444,139 |

42.7% |

14,669 |

1.9% |

| New York | 574,109 |

1,039,624 |

55.2% |

563,232 |

1,047,668 |

53.8% |

10,877 |

1.5% |

| Queens | 555,573 |

1,242,030 |

44.7% |

555,930 |

1,286,661 |

43.2% |

-357 |

1.5% |

| Richmond | 148,660 |

325,355 |

45.7% |

142,121 |

306,684 |

46.3% |

6,539 |

-0.6% |

| Total | 2,226,380 | 4,788,780 | 46.5% | 2,186,436 | 4,856,143 | 45.0% | 39,944 | 1.5% |

The Exit Polls

Blue-staters seem to be taking this electoral loss much harder than many in the past, and one reason may be that, on Election Day itself, it looked as if Kerry might win. Throughout the afternoon, bloggers and others offered the results of early exit polls that showed Kerry building a large lead in many of the swing states.

But by that night, Florida, Ohio, Iowa, and New Mexico had turned from blue to red, and the count was much closer than the exit polls suggested in Michigan, New Hampshire, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Kerry went from being a shoo-in to being a loser, and his predicted two-percent vote lead became a three percent loss. How did this happen? At this writing no one knows. Indeed, a recent paper “The Unexplained Exit Poll Discrepancy” (In PDF format) by Steven F. Freeman of the University of Pennsylvania pulls together the exit poll data and eventual tallies in the battleground states. His conclusion: “. . . two broad categories of explanations: the polls were flawed or the count is off.” At this point, since the raw data have not been released, it is impossible to conduct further analyses and definitively answer that question.

Flawed Voting Process

However, the election of 2004 was not free of the problems that made the election of 2000 so controversial. Once again, election officials were accused of being partisan, and of suppressing the vote of the opposition. Ohio’s Secretary of State tried to make it harder for new registrants to be added to the voting roles, originally voiding voter registration applications printed on the back of fast food restaurant menus because the paper was “too thin.” Other evidence of voter suppression -- not having enough voting machines in poor and black areas, so that the voter lines lasted for hours. In 2004, such suppression probably did not cost Kerry the popular vote majority, but it certainly could have cost him Ohio, and thus the election.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

The Citizen

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

New York's Creative Class

New York City is a world center for the creative arts: drama, music, dance, entertainment of every kind, art, photography, writing and publishing. Those hoping to be successful in these fields flock to New York City. These creative New Yorkers make the city distinctive in many ways - not just as a cauldron for innovation in the arts, and a magnet for tourism and conventions, but also as an engine of the economy: A new study for Lincoln Center found that the arts complex generated $1.52 billion in sales and employed 15,200 workers. Some argue that urban economic development and growth depend upon "The Creative Class."

Who are the individuals that make New York City the creative center that it is? Where do they come from, how are they faring? By analyzing census data we can get some answers.

How Many Are There? Where Do They Live?

Those who work in the creative and performing arts make up less than one percent of those who either worked or lived in the New York City metropolitan area, according to the 2000 Census. These included:

- 34,066 artists

- 28,682 writers and authors

- 22,860 musicians or singers

- 14,318 photographers

- 11,346 actors

- 3,684 dancers and choreographers

And 4,394 other entertainers.

Over a quarter of the people in these groups made their home in Manhattan, including 56 percent of all actors and 41 percent of all dancers.

This is sharp contrast to New Yorkers over all; only eight percent of people who either work or live in one of the five boroughs, reside in Manhattan.

Wherever they live, most creative professionals work in the city -- 73 percent of actors, 70 percent of dancers, 55 percent of artists -- most of these in Manhattan.

Who Are They Ethnically, Etc.?

A higher fraction of New York City's creative workers are white (e.g. actors 82 percent, artists 80 percent) than are other workers (51 percent).

Dancers are more likely to be female, but photographers and musicians are more likely male. A higher proportion than other New York City workers have never married. Members of the creative class are much better educated than other New York City workers, except for dancers; a much greater proportion finished at least four years of college. It is clear that many move from other parts of the United States to New York for their art. Fewer than average were born in New York State, but much more than average were "native-born", born in the United States, as opposed to abroad.

Struggling Or Thriving?

There are large differences among the various creative fields in terms of whether they worked at all "last week". About 28 percent of all actors did not work in the last week - the largest proportion out of work. Except for dancers, those in creative fields were more likely to have worked in the last year than other New York City workers.

However, the creative worker, except for artists and writers, earn less than the average New York worker; actors and dancers earned the least.

Considering how well educated the creative workers are they do not earn what their skills and background would command in more conventional fields. The average New York worker earned $29,000 in 1999. By contrast, one quarter of all actors earned $9,000 or less. Except for writers, the bottom quarter of each creative group earned less than did the bottom quarter of all New York City workers.

On the other hand, it really is possible to hit it big in New York in the arts. The top quarter of most creative groups earned as much or more than the top quarter of New York City workers as a whole. Some musicians and singers and artists reached the maximum reported income in New York in 1999, $627,000. (Of course, this represented just a small number, and it is not clear how accurate the numbers; the very wealthy among any group are well known to be much harder to reach and much less likely to give full information about their income.)

Generally, though, the creative in New York City, especially actors and actresses, earn less than the average New Yorkers, much less than New Yorkers of similar education and skill level. Some exist on very meager incomes and supplement their earnings from creative endeavors with that from waiting on tables, driving taxis, working in telemarketing and so on.

A few earn phenomenal amounts of money and live the celebrity dream, and a few more become quite successful and live comfortable upper middle class lives. But for the most part, if New York City's creative workers are a driving force for urban development, they are not the main beneficiaries.

The Citizen

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

New York City Is a Non-Voting Town

Though it is common to call New York City a Democratic town, Democrats are actually in the minority. In election after election, the solid majority is made up of non-voters.

That is how roughly only 15 percent of all New Yorkers eligible to vote made Michael Bloomberg the mayor in 2001. In the last presidential election, in 2000, fewer than half of New Yorkers eligible to vote bothered to do so - and that is the highest it ever gets.

So who are these non-voters?

First of course are those who are not eligible to vote. Of the six million New Yorkers who are 18 years of age and older, only about 4.7 million are citizens. Breaking that down ethnically, there were:

• 12 percent of non-Hispanic whites not eligible to vote

• 20 percent of non-Hispanic blacks not eligible to vote

• 34 percent of Hispanics not eligible to vote

• 54 percent of Asian not eligible to vote

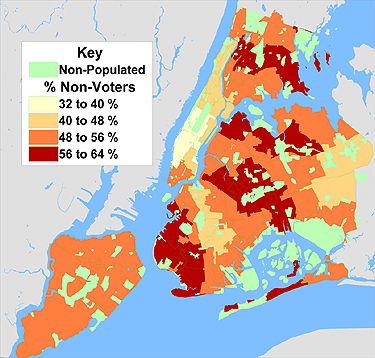

As the accompanying map shows, the areas with the smallest proportion of non-voters are in Manhattan, including the Upper East Side, the upper west side and areas south of 59th Street.

The highest proportion of non-voters live in

- Bensonhurst, Borough Park, and Bay Ridge in Brooklyn

- East Tremont and Bronxdale in the Bronx

- Astoria, Flushing and East Elmhurst in Queens, along with Middle Village, Howard Beach, and Ozone Park.

In short, there is no direct relationship between economic distress of an area and non-voting among those eligible.

Every two years after every national election, the United States Census Bureau asksa representative sample of the US population if they voted. Using those data for the period after the 2000 Presidential election one can get a picture of those who do not vote even for President. (Of course asking someone whether or not he or she voted is likely to elicit a certain amount of lying. Indeed, about 55 percent of those sampled claim they did vote, about seven percent more than those who actually did.)

- Women are more likely to vote than men (57 percent to 52 percent).

- Blacks are more likely to vote than whites (61 to 57 percent).

- Renters are slightly more likely to be voters than owners (57 to 54 percent).

- Those that own a business are more likely than those who do not (62 to 55 percent).

- Those working and those retired are more likely to vote than those without jobs (60 to 50 percent). However, there is no relationship between family income and voting.

Those in higher status occupations and those with college degrees voted at a higher proportion than others eligible (68 to 55 percent).

Those married with spouse present, as well as those widowed, divorced or separated voted at much higher rates than singles or those living without their spouse. Those born in the United States were slightly more likely to vote, while those from Puerto Rico were slightly less likely to vote.

Though some demographic and other groups do vote at a somewhat higher rate than others, it is nonetheless the case that for virtually every population category non-voting is rampant. This is all the more true in non-Presidential contests, even when a handful of votes would make a difference.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

The Citizen

|

The Citizen is in another location. If you are not automatically directed to the correct page, click the following link: |

New York's Divided Afghans

Â

As a recent court case makes clear, the Afghanis who fled to New York City do not seem to have entirely escaped the turmoil back in Afghanistan, one of the poorest countries in the world, and one that has been wracked with both internal divisions and external invasions for most of the last 25 years.

Shortly after September 11th, 2001, Imam Mohammed Sherzad, the spiritual leader of the Hazrat-I-Abubakr Sadiq Afghan Mosque in Flushing, accused the founders of the mosque of supporting the Taliban, and in effect kicked them off the premises. The founders accused the imam of making up his accusations in order to take control of the mosque. They sued. Last month, a state supreme court justice reportedlyreturned the mosque to their control.

The case offered a glimpse into a community that seems nearly as divided here as in Afghanistan. And, thanks to the U.S. Census Bureau, which for the first time released data on 89 so-called ancestry or ethnic groups from the 2000 census, we can begin to piece together a demographic portrait of this complicated community as well.

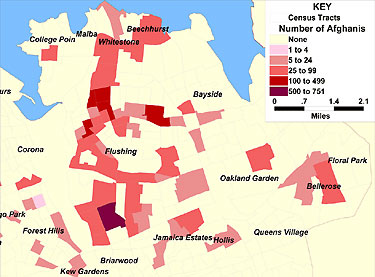

The census found about 9,119 individuals of Afghan ancestry who live in the New York metropolitan area, a figure far smaller than the 20,000 normally cited. Of course, the census bureau may have missed some Afghans (as many as 30 percent), but it also likely that the higher figure is an exaggeration.

About two-thirds of the Afghanis were foreign born. Most left their homeland because it was no longer safe. Of these, more than half fled the Soviet invasion starting in 1979. Others fled when the Taliban militia took over in 1996. Still others fled during or after our bombing of Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002. These three groups may well have very different views.

The Afghanis in the city are relatively poor, with a median household income in 2000 of about $25,000, compared to about $38,000 for all New Yorkers, and about $50,000 for Afghanis in Long Island. Afghans are highly concentrated residentially in and around Queens, especially Flushing, as shown by the accompanying map.

Afghanis are more likely to be male, to live in a family, and to have had no schooling than New Yorkers as a whole. The 55 percent of Afghani New Yorkers who are male are much better off than the women. About eight percent of the men and almost 25 percent of the women have never attended school. Indeed, over 70 percent of Afghan men between 21 and 64 were employed in 2000 according to the Census, which is almost identical to the 69 percent rate overall for men in New York City. But only 26 percent of Afghan women were employed, which is well below the 58 percent rate for all New York women.

Manizha Naderi, the director of Women for Afghan Womenreports that before some Afghani women are allowed to go to the ESL class sponsored by her organization, their husbands check it out to make sure that the class is not being run by a communist or Catholic organization. The organization also helped to sponsor a conference in Kandahar to write a Bill of Rights for Afghan Women that was supposed to have been made part of the new Afghan constitution. Despite many promises, it was never added. Many Afghanis in the New York City would agree that Afghan women should not have a Bill of Rights.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Ikea And Red Hook's Racial Divide

"I have to laugh at the groups who say Ikea is splitting the neighborhood," says Judith T. Dailey, a long-time resident of Red Hook in Brooklyn. "The fact is Red Hook has always been split."

Dailey was among scores of Red Hook residents who attended a recent meeting of Community Board Six in Brooklyn to support the proposed building of a 350,000 square foot Ikea superstore on the Red Hook waterfront. . The boardis expected to give the necessary approvals for the project to go ahead.

Environmental groups have joined with some Red Hook residents to oppose the project. They point to the proliferation of big box stores on the city's waterfront, as well as the increase in traffic and air pollution.

The longstanding divide that Judith Dailey alludes to is between residents of Red Hook Houses, a public housing project where about 70 percent of the neighborhood population lives, and homeowners in "The Back." But this division is more than just about turf. The majority of people in Red Hook Houses are people of color, and the most vocal residents of "The Back" seem to be white. Only the public ethic of color blindness allows everyone to politely forget the mention of race as a factor in this division.

Ikea's opponents correctly point out that the trucks and over 9,000 cars per day that Ikea will attract will create havoc in this peninsula that functions well as an urban village. The planned reconstruction of the Gowanus Expressway, or its deconstruction and replacement with a tunnel, will route even more traffic through Red Hook for over a decade. Ikea is proposing to re-engineer several intersections and widen some streets, but that will only make it easier for people to drive to Red Hook, whether for Ikea, the new Fairway planned for another waterfront site, or any number of other new commercial giants waiting in the wings to gobble up Red Hooks vacant waterfront sites.

But according to Judith Dailey, "The traffic won't kill us, we need this window of opportunity." Representatives of tenants at Red Hook Houses believe the 500 to 600 jobs promised by Ikea are more important. Perhaps 60 percent of those jobs will be full-time and Ikea has promised to accept applications from Red Hook residents before opening up the hiring process to others. They also propose to provide training.

Ikea Looking Good

On the surface, Ikea looks pretty good when compared to the standard head-strong developer who plows ahead without consulting with their future neighbors. This Swedish multinational giant with 180 stores in 31 countries looks like a socially responsible neighbor when compared to bull-headed predators like Wal-Mart and Home Depot, or the despots of downtown Brooklyn, Forest City Ratner. Instead of ignoring public housing tenants as developers, Ikea talked with them. And tipping their hats to the other side of the Hook, they put in a few environmental innovations, like a small green roof. They committed to keeping a barge operator - one of the last vestiges of the working waterfront - as a neighbor, and say they'll start a ferry service and shuttle to the nearest subway. In all, despite charges that it exploits labor and contributes to the destruction of forest land in poor countries, Ikea has a pretty good public image.

But before giving any civic awards to Ikea, consider what they're NOT doing. First of all, there's nothing in writing to guarantee local jobs. Verbal commitments alone can easily evaporate, and the recent history of big box stores raises serious questions about the quality and long-term viability of their jobs (see the recent articleby Hilary Russ in Gotham Gazette). Ikea's goal of 100 prtvrny local hires is hardly altruistic. Most of the jobs pay modest wages that won't attract workers from long distances anyway.

Secondly, the street improvements Ikea says they will pay for are more likely to help the SUV drivers coming to shop from all over the region than Red Hook residents. Ikea isn't helping to create safe pedestrian or bicycle ways in Red Hook and instead will bring more traffic through the most heavily populated areas, including public housing. Ikea needs to make the street improvements to get past the legally-mandated environmental review and they would lose time and money if they had to wait for the city to make the changes.

Third, the ferry and shuttle bus seem to be only icing on Ikea's cake, since the company estimates that 85 percent of its shoppers are going to drive there anyway.

Fourth, by providing public access to the waterfront, Ikea is not giving anything extra to Red Hook. It would be required to do this under the city's commercial waterfront zoning.

Lost Opportunities

Precisely because Ikea is more open and willing to give something back to the neighborhood that welcomes it, we have to ask why they're allowed to get away with giving so little. Wal-mart and other big box developers are eyeing Red Hook, so doing the right thing with Ikea could set a higher standard for future proposals. If Ikea could genuinely integrate their project into a revitalized Red Hook it may not turn out to be yet another corporate enclave on the waterfront.

There are at least three reasons why Ikea is a lost opportunity.

The first reason is that it leaves intact the historic divide among Red Hook residents (and businesses, too). This fits neatly with the classic role that racism has played in community development: it allows developers to divide and conquer. Until our color-blind officialdom starts talking honestly about race, it will continue to undermine the ability of communities to have a say in planning their futures.

Secondly, city agencies that should be playing a proactive role are, at best, passive players. Why isn't the Department of Transportation and the Department of City Planning telling Ikea to reduce the amount of parking, beef up public transit, or find a better location? The Department of Transportation years ago rejected the de-mapping of truck routes in Red Hook that run through residential streets, so I guess it would be out of character to now be concerned that pedestrians might get run over by Ikea's trucks and shoppers.

Finally, the Ikea proposal ignores the official plan for Red Hook, which was approved by the City Planning Commission and City Council. This plan was developed a decade ago in a two-year-long process that brought together the neighborhood's diverse residents and businesses. It projected a vision of a mixed industrial/residential community without separate waterfront enclaves. The city takes no responsibility for implementing this plan. After it was approved the Red Hook plan was put on the shelf and forgotten. If the city's planners took it seriously they would remind everyone that the Ikea site was to be preserved for industrial and maritime uses. This policy is consistent with the city's own Waterfront Revitalization Plan. So why isn't the city sending Ikea and the parade of other big box stores to downtown locations where subways and buses are already in place, and promoting industrial and maritime uses on this section of the waterfront?

Perhaps the divisions in Red Hook give city officials a good excuse for their actions and inactions. Both Ikea and the city could use their considerable power and resources to bring everyone to the table. But perhaps that's too much to ask for. When people start working together they may envision a future that goes far above the bottom line and remember their own visions for the future of their neighborhood.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.