Failure of Redistricting Reform Could Bring Reprise of 2002's Fiasco

Photo by Boss Tweed

Former Mayor Ed Koch got a majority of state legislators to sign a pledge saying they supported redistricting reform but, so far, that has not translated into change

As the current state legislative session winds down, efforts to reform the redistricting process in New York state appear to be dead. Yet, at this very moment the new Citizens Redistricting Commission in California, which has final authority, has released a preliminary plan that in the process of cleaning up lines would radically alter the California congressional delegation.

It would add up to five Hispanic seats, increase the number of Democrats and throw a number of sitting U.S. representatives into the same district. Beyond that, the commission's proposal may end up creating the Democratic super majorities in both houses of the state legislature needed to raise the state's taxes and pull it out of its financial crisis.

Meanwhile in New York state, despite former Mayor Ed Koch's efforts to get many legislators to pledge to vote for reform, despite the fact that Gov. Andrew Cuomo claims to be making it a priority and despite universal support of the usual good government groups, no bill has been reported out or is expected to come to the floor before the session is over in a few days. This means that the same chaotic system that brought us an impasse in Congress and the deadlocked State Senate will remain in place for this round.

Obstacles n New York

The California experience throws into high relief why reform of the legislature by the legislature repeatedly fails in New York state despite receiving lip service support for the last few years. Two reasons stand:

- If the system changed, incumbents would not be protected, and many would face opponents who are also sitting legislators.

- Under the current system, demographic shifts that would throw both houses into Democratic hands can be contained. This was done in 2002 and will likely be repeated this time around.

A constitutional amendment would make it possible to have the type of reform that happened in California. But for that to happen, the legislature would have to pas the measure in two sessions, and the voters would then have to ratify it.

The Democrats could have started the process by passing a constitutional amendment on redistricting reform last year when they controlled both houses of the legislature. They did not. If they had -- and if the amendment passed again this term -- it could have been on the ballot this November, in time for this round of redistricting.

The enactment of a legislative reform remains possible. This would mean that a commission would draw lines, but the legislature and the governor would have to approve the lines and so would have final say. Even this limited reform has not made it to the floor of either house.

When one looks at what is ahead for redistricting, it is obvious why this has happened. Republican senators do not want to lose their majority, and the Democrats in the Assembly do not want to risk their individual seats and lose a few members from the majority, despite their overwhelming advantage. This stalemate occurred even though the fiasco that was redistricting last time is about to be rerun, and everyone claims to support reform.

The Results Last Time

The population shifts found in the 2010 census are very similar to those in 2000, and now as then two congressional seats have been lost. In 2002 a judge declared an impasse after the legislature failed to act, and a set of congressional lines were proposed by a special master. At the point a deal was cut and the present congressional lines were approved.

In the last redistricting, all plans initially considered for the State Senate involved 61 seats, the total number at that time. Then at the 11th hour, a new plan was proposed. It added one seat downstate bringing the total number of senate districts to 62.

In addition, the plan carefully allocated the population so that every district downstate was overpopulated and every district upstate was under populated. It also maintained the so-called Velella racial gerrymander, (the seat now held by Jeffrey Klein); and cracked and packed minorities in Long Island. "Cracking" involves splitting a large bloc of minority voters into several districts, so that they cannot chose their preferred candidate. "Packing" means putting a large block of minorities into one district so as to reduce their impact several districts.

This plan was challenged in federal court unsuccessfully. Because it allowed for an even number of senators, it led directly to the State Senate deadlock in 2009.

The Assembly plan in some ways was the mirror image of the Senate plan. Most districts upstate were over populated, many downstate were under populated. Incumbents were protected.

What Can We Expect This Time?

I have prepared data on the population and the citizens of voting age population by various groups for the present set of lines. Here is what New York State faces. For Congress:

- All congressional districts are under populated. (Congressional seats are required to be effectively equal.)

- Two seats will be lost, One from districts from 1 to 14 or 15, which encompasses the city and its suburbs. The other seat will come from upstate -- from districts 16 through 29.

- Districts 10, 6 and 11have a majority of voting age citizens who are African Americans.

- District 16has a majority of Hispanic voting age citizens.

- Two additional districts have a majority of Hispanic and African Americans of voting age combined. Two more are near such a majority.

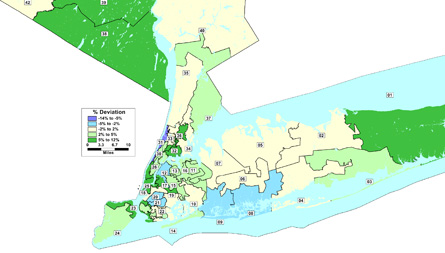

Currently all but one of the state's congressional districts -- District 1 in eastern Long Island -- is smaller than the ideal district. For a larger map showing how much each district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

For the State Senate:

- 13 districts are under populated (based upon a deviation of 5 percent from the ideal), while eight are over populated.

- Most under-populated districts are upstate.

- Six districts have a majority of African American citizens of voting age.

- Two districts have a majority of Hispanic citizens of voting age.

- Four districts have a majority of Hispanics and African Americans of citizen of voting age combined.

Under New York's current State Senate districts, voters upstate -- many in largely Republican areas -- have more clout than their downstate counterparts. Most of the districts with fewer voters than average are upstate, while those with a larger number of voters are more likely to be closer to New York City. For a map showing how much each State Senate district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Under New York's current State Senate districts, voters upstate -- many in largely Republican areas -- have more clout than their downstate counterparts. Most of the districts with fewer voters than average are upstate, while those with a larger number of voters are more likely to be closer to New York City. For a map showing how much each State Senate district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Many of the State Senate districts in and around the city are larger than normal for the state, giving their residents less power. A glaring exception is District 31, stretching along the West Side of Manhattan and into the Bronx. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Many of the State Senate districts in and around the city are larger than normal for the state, giving their residents less power. A glaring exception is District 31, stretching along the West Side of Manhattan and into the Bronx. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.For the Assembly:

- 26 districts are under populated and 22 are over populated based upon a 5 percent deviation.

- Fifteen districts have a majority of Africans American citizens of voting age.

- Twelve districts have a majority of Hispanic citizens of voting age.

- Eight additional districts have a majority of Hispanics and African American citizens of voting age combined.

For a table listing all 150 State Assembly districts and their demographic characteristics, as well as their size, go here.

With 150 Assembly districts, those deviating sharply from ideal size are more scattered around the state than is the case with State Senate districts. For a map showing how much each State Assembly district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Heavily Democratic New York City has a large number of State Assembly districts that are substantially smaller than normal, giving their resident ore clout in the Assembly than people who live in more Republican Long Island. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Hammer Lock

The population's changes are massive, but the legislature together with the governor have chosen to keep complete control of the redistricting process (except for possible court or Justice Department intervention) for another round. They will maintain their power, as they have in the past. Unlike California, there is little prospect for fair redistricting in New York State, only chaos similar to the last round. (To view my recent testimony in Albany on Redistricting Reform, go here and here.)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Wounded City's Pride but Probably Got the Numbers Right

Photo by Jason Chiu

The 2010 census poured cold water on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's rosy view that New York City would hit 9 million long before 2030. The census found that, instead of growing to 8,421,789 residents as the census estimated just a few days before the official numbers were released, New York City had only 8,175,153 residents, some 246,636 less than expected.

The estimated brisk growth pace of 5.2 percent since 2000, suddenly became a phlegmatic 2.1 percent. Indeed, if present trends continue New York City will not make it to 9 million until sometime in the decade of 2050. In short, the growth rate, if correct, means that many of the enthusiastic proclamations about the city's unique growth and its attractiveness as a place to live are simply wrong.

Predictably, the mayor, who made his fortune purveying presumably accurate financial information, is not willing to believe that the census's careful enumeration of New York’s population could be correct. He is planning to challenge it, and other officials are supporting that challenge. However, instead of taking the issue to court, they plan to invoke the Census Bureau's own Count Resolution process. This is a technical procedure that generally corrects blatantly wrong counts. After 2000, for example, the Census Bureau placed a number of prisons and college dorms in the wrong cities, counties and towns. When these mistakes were brought to the Census Bureau’s attention, it corrected such obvious errors.

New York's argument for an adjustment is much more complex relying as it does upon the increase in vacancies and the undercounting of immigrants. Indeed, there are at least four reasons to have confidence in the census count.

1. Housing vacancies are on the rise in New York City and throughout the country:

Over the decade New York City did see an increase of about 170,000 housing units, but, according to the Census, the number of vacant units rose by some 82,000.

Bloomberg explanation: The census misclassified many occupied units as vacant.

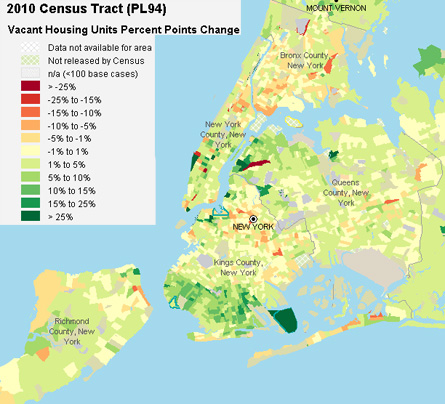

Home and apartment vacancy rates rose between 2000 and 2010 -- in New Yrk and throughout much of the country (For a larger version of this image, go here.

Possible other explanation: Many of the new units were built as part of the boom and remain vacant. As the accompanying map shows, the rise in vacant units occurred not in the immigrant areas in Brooklyn and Queens, but rather in other areas such as the far West Side and Bay Ridge Brooklyn. Most of the other cities in the United States experienced a large increase in the proportion of vacant units. Indeed New York City's increase of 2.15 percent means that it ranked 79th out of the 109 cities with more than 200,000 population in 2010. New York City, along with the rest of the United States, experienced a housing bubble and still working through the extra units that were constructed during that bubble. So the vacancies may be real, unless New York City experienced growth unlike any city in the country.

2. This census missed many immigrants.

The Bloomberg administration has said the census staff was unable to count many newcomers to the city, particularly those who came to the country illegally or live in illegally divided apartments.

Other explanation: Of course some immigrants were missed, but it is also true that immigration of all sorts slowed during the financial crisis. It may be that New York’s immigrant fueled growth may have tapered off.

Certainly the strong increase in immigrants seen in places like Queens and Brooklyn during the decade of the 1990s has slowed substantially, as the climate for immigrants has become much less friendly nationally and their job prospects have ebbed. Indeed, Jeffrey Passel and D'Vera Cohn at the Pew Center estimatedthat the number of illegal immigrants to the US declined by about one million between 2007 and 2009. New York City seems likely to have experienced some of this decrease.

3. The 2000 census may have overcounted New York City.

This is a seldom discussed point, but if the census, because of the very real difficulties of getting an accurate count in a city as diverse as new York, could have overcounted the number of people in the five borough in 2000 due to putting phantom residents into housing units that did not exist or by double counting some. (For more on this, see my earlier column.) If this happened and the excess was reversed in 2010, New York City's apparent growth would be less than its real growth.

Apparently the census also considered this possibility as I outline in another previous column: . If the city had been overcounted by say 200,000 in 2000, and was not overcounted this time, its real growth would actually be about 4.7 percent. Any overcount would serve as the base for the census estimates during the past decade, so if the city were overcounted by 200,000 in 2000 -- and so really had about about 7.8 million people -- then the estimated growth of roughly 420,000, would bring the census estimate almost exactly to the same number as were counted in 2010.

4. The 1990 census undercounted New York's population.

An undercount in the 1990 census, which New York and other big cities challenged in an unsuccessful lawsuit, means that the increase in the 1990s was overstated. Any undercount in 1990 combined with the possible overcount in 2000 would have inflated the percentage growth between 1990 and 2000. Because many demographic and econometric models use recent growth to estimate future growth, the projection for the first decade of the 21st century then could have vastly overestimated population growth.

All in all then, it is quite likely that the 2010 census count is basically accurate, but that the growth rate for the city is more than suggested by the change between 2000 and the 2010 census. New York, it seems, did participate in the slowing of immigration and overbuilding that were common in the 2000s.

When question about the city's growth, Bureau of the Census director Robert Groves said, "This is the time when many mayors receive counts that disappoint." Though Bloomberg and his administration indeed may be disappointed, the census surprise for New York City pales in comparison with that for Detroit. The wrong estimate there implied that Detroit had about 200,000 more people than it had -- meaning the numbers originally projected the Motor City as being 28 percent larger than it turned out to be.

Many cities in the United States, especially in the East, had population loss or very slow growth since 2000. Maybe it is disheartening that New York’s apparent growth in the 1990s did not continue into the 2000s, but after the 9/11 attacks and the financial crisis, maybe the city's continued though slower growth indicates not weakness but just how robust New York City is.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Brings Unpleasant Surprise for State Politicians

These maps show the estimated shifts in population between the 2000 Census and 2009. As has been true for decades, upstate regions continue to lose population.

New York state received a nasty surprise from the Census Bureau on Dec. 21. According to the first results from census 2010, the state has 163,351 fewer people than the bureau estimated it did on July 1, 2009. As a result, New York will lose two congressional seats, bringing its total down to 27, tying it with Florida.

The loss of two congressional seats will set off a huge redistricting fight. Beyond representation in Congress, the diminished New York state population will have a major impact on the amount of federal aid that the state receives.

The Missing New Yorkers

If New York's population had matched the July 1, 2009 estimate, it would have lost only one seat. If the estimated rate of growth in the population from 2008 to 2009 had continued to April 1, 2010, then the state would have 19,596,910 residents, some 218,808 more than the 19,378,102 persons who were actually enumerated.

This chart compares the population count in the 2000 census and the year-to-year estimates with the final count in 2010. The purple indicates how much larger the 2010 count would have been if the estimated trends had continued. (Click on the chart to view a larger image.)

Demographers and politicos are scratching their heads trying to figure out how this happened and what the implications will be. Unlike California, which has already claimed an undercount and protests the census results , New York state is still contemplating the impact and sources of this apparent population loss.

An examination into which parts of the state were overestimated or undercounted is necessary. Once the redistricting data are released in March, we will have much better information.

In general, though, there are three possible explanations:

-- The procedure by which the census creates estimates is flawed.

-- There are problems with the census 2010 count.

-- The 2000 count may have been somewhat inflated, and the new count reflects a return to reality.

Each of these explanations could be true in various ways. The census estimates are based upon births and deaths and international and domestic migration. Immigration -- foreign or domestic -- is particularly hard to capture, and the number of immigrants to New York state may have declined. Foreign immigration would mostly affect the city and downstate, while domestic immigration is important upstate.

New York state has many "hard to count" areas, especially in the city. Though major efforts were made to count residents from these areas, it may be that the backlash from 9/11 and a perceived increase in anti-immigration sentiment led some immigrants to be less willing to participate in the census than they were in 2000. Similar problems may have affected upstate, if the census outreach was ineffective.

Finally, technical issues related to the addition of extra addresses arising from a census check of addresses in 2000 may have led to duplication. If so, it is possible that the city population was somewhat overcounted in 2000. Since the census numbers from 2000 become the base for the census estimates, if those extra addresses were removed or the Census Bureau eliminated more duplicate addresses, then the population in the city, especially in parts of Queens and Brooklyn would be less than was estimated.

Up for Grabs

Whatever the reason for the lower count in New York State, the implications for congressional redistricting are massive. Most of the population losses occurred in upstate New York, while the gains were in areas in and around the city, most particularly in outer ring suburbs.

The table below shows each district's population gain or loss, and some characteristics of the district, including the current incumbent, his or her party, the member's vote in the November elections and the degree to which the districts deviates from the ideal population size of 717,707 people.

| District | Party | Name | Incumbent | 2010 Vote Percentage | Pop 2000 | Estimated Population 2010 | Change from 2000 | Deviation from Ideal | % Deviation |

| 1 | Dem | Timothy Bishop | Yes | 50.05 | 654,360 | 713,122 | 58,762 | -4,586 | -0.64% |

| 2 | Dem | Steve Israel | Yes | 56.60 | 654,360 | 687,889 | 33,529 | -29,819 | -4.15% |

| 3 | Rep | Peter King | Yes | 72.00 | 654,361 | 653,477 | -884 | -64,230 | -8.95% |

| 4 | Dem | Carolyn McCarthy | Yes | 53.70 | 654,360 | 657,810 | 3,450 | -59,897 | -8.35% |

| 5 | Dem | Gary Ackerman | Yes | 62.40 | 654,361 | 699,143 | 44,782 | -18,565 | -2.59% |

| 6 | Dem | Gregory Meeks | Yes | 94.90 | 654,361 | 654,564 | 203 | -63,144 | -8.80% |

| 7 | Dem | Joseph Crowley | Yes | 79.70 | 654,360 | 673,522 | 19,162 | -44,186 | -6.16% |

| 8 | Dem | Jerrold Nadler | Yes | 75.00 | 654,360 | 695,491 | 41,131 | -22,217 | -3.10% |

| 9 | Dem | Anthony Weiner | Yes | 58.50 | 654,360 | 691,231 | 36,871 | -26,476 | -3.69% |

| 10 | Dem | Edolphus Towns | Yes | 91.00 | 654,361 | 680,793 | 26,432 | -36,915 | -5.14% |

| 11 | Dem | Yvette Clarke | Yes | 90.30 | 654,361 | 668,394 | 14,033 | -49,314 | -6.87% |

| 12 | Dem | Nydia Velazquez | Yes | 92.90 | 654,360 | 688,434 | 34,074 | -29,273 | -4.08% |

| 13 | Rep | Mike Grimm | No | 51.50 | 654,361 | 698,637 | 44,276 | -19,071 | -2.66% |

| 14 | Dem | Carolyn Maloney | Yes | 74.90 | 654,361 | 666,335 | 11,974 | -51,372 | -7.16% |

| 15 | Dem | Charles Rangel | Yes | 79.90 | 654,361 | 661,747 | 7,386 | -55,961 | -7.80% |

| 16 | Dem | Jose E. Serrano | Yes | 95.40 | 654,360 | 684,421 | 30,061 | -33,287 | -4.64% |

| 17 | Dem | Eliot Engel | Yes | 72.10 | 654,360 | 668,910 | 14,550 | -48,797 | -6.80% |

| 18 | Dem | Nita Lowey | Yes | 62.00 | 654,360 | 669,824 | 15,464 | -47,883 | -6.67% |

| 19 | Rep | Nan Hayworth | No | 52.80 | 654,361 | 709,848 | 55,487 | -7,859 | -1.10% |

| 20 | Rep | Christopher Gibson | No | 55.40 | 654,360 | 675,617 | 21,257 | -42,091 | -5.86% |

| 21 | Dem | Paul Tonko | Yes | 59.30 | 654,361 | 660,109 | 5,748 | -57,599 | -8.03% |

| 22 | Dem | Maurice Hinchey | Yes | 52.40 | 654,361 | 662,365 | 8,004 | -55,342 | -7.71% |

| 23 | Dem | Bill Owens | Yes | 48.10 | 654,361 | 652,743 | -1,618 | -64,965 | -9.05% |

| 24 | Rep | Richard Hanna | No | 52.90 | 654,361 | 633,497 | -20,864 | -84,210 | -11.73% |

| 25 | Rep | Ann Marie Buerkle | No | 50.20 | 654,361 | 646,863 | -7,498 | -70,845 | -9.87% |

| 26 | Rep | Christopher Lee | Yes | 73.80 | 654,361 | 646,879 | -7,482 | -70,829 | -9.87% |

| 27 | Dem | Brian Higgins | Yes | 60.80 | 654,361 | 624,284 | -30,077 | -93,423 | -13.02% |

| 28 | Dem | Louise Slaughter | Yes | 65.20 | 654,360 | 604,913 | -49,447 | -112,795 | -15.72% |

| 29 | Rep | Thomas Reed | No | 56.50 | 654,361 | 647,243 | -7,118 | -70,465 | -9.82% |

As the table makes plain, Districts 1 through 19 will need to lose one seat, while districts 20 through 29 will lose the second seat. Though District 28, represented by Louise Slaughter, and District 27, represented by Brian Higgins, are the farthest below the new ideal of 717,707, it will require 10 districts becoming only 9 to make upstate districts conform to population equality. Similarly, even though most districts in the downstate area have been growing, the 19 downstate districts will need to become 18 to leave New York with the 27 seats to which it is entitled.

Thanks to the new census count, New York state is now in for two separate games of musical chairs to find out which representatives will no longer have seats to call their own.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Likely to Offer Accurate Count of New Yorkers

Photo by Quinn Dombrowski

The 2010 census appears to be on its way to be a major success for New York City. We should be grateful for the unprecedented engagement of community, neighborhood and ethnic organizations, as well as adequate funds for communication, outreach and advertising. This all led to a substantial increase in the rate of initial mail response for New Yorkers. When the state population counts that determine the number of seats in Congress are released on Dec. 28t and the block level data for reapportionment for legislative districts are released in March, New York City should do quite well.

The initial response rate rose from 57 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2010 in New York City. The overall national rate stayed the same at 72 percent.

The increased initial participation in the city means both better data and cheaper data collection. When people respond to the initial mailing, the Census Bureau does not have send out enumerators to knock on doors and collect the information, saving money.

While some households that do not respond become "hard to count," the largest fraction of households visited by enumerators easily provided information when contacted, some even apologizing for not sending in their form on time. Other housing units whose residents did not respond proved to be vacant. Enumerators revisited any vacant units to confirm that no one lived there.

Filling in the Gaps

Of course, in any huge operation like the census there are bound to be glitches here and there, but the Census Bureau established built in checks to assure accuracy. Most of the error and difficulties encountered by some census enumerators will be corrected during the quality control phase. For instance, any home that had an incorrect address was rechecked, and a small sample of households is being reinterviewed to validate the accuracy of the original count. Checks also exist to eliminate duplicate responses for those who filled out the form in more than one residence.

Despite the relative success and the efforts at quality control, some groups are very difficult to interview, leaving some missed homes and some incorrect or inconsistent information. To address this, the Census Bureau has a number of procedures it follows when it cannot get an interview or the response is either not complete or inconsistent with other responses from the household. These technique, based on statistical methods, come under the heading "imputation and allocation. "

There are two types of imputation and allocation:

Whole unit imputation comes into play when there is no answer for a unit known to be occupied. In such cases, the census applies what is known as the "hot deck" procedure and determines -- or imputes -- the characteristics of the household from those of other nearby households.

The term "hot deck" harkens back to the time when computers used punched cards. The hot deck contained information on those who were recently tabulated from the same neighborhood living in the same type of unit. Such data still exists -- even if the hot deck does not -- and is used to fill in information on nearby, missing with similar known characteristics.

The other method is "item and person allocation," where a household has provided answers, but they either incomplete answers or include inconsistencies. Here the information on the occupants that do exist is used to impute, much as the "hot deck'" was for the vacant unit So one can impute sex by using first name, if it is known. A Committee of the National Academy of Sciences discussed and reviewed these census procedures.

The New York Data

In the past, New York City has relied more on imputed data than the U.S. as whole has. The table below presents information on the imputation of basic characteristics in the city in 2000. The census reported that 4.7 percent of the housing units' vacancy statuses were imputed. In 8.9 percent, it imputed whether or not the unit was owned or rented. This compares with 2.6 percent for vacancy and 4.8 percent for owned or rented nationally.

| United States | New York City | Bronx | Kings | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | |

| Overall Person Imputations | |||||||

| Any Item Imputed | 10.9% | 20.0% | 26.4% | 22.3% | 16.5% | 17.8% | 10.6% |

| Population Substituted | 1.2% | 3.9% | 5.7% | 5.4% | 1.2% | 3.4% | 1.5% |

| Specific Imputations | |||||||

| One or more items Impurted | 9.6% | 16.1% | 20.7% | 16.9% | 15.2% | 14.3% | 9.1% |

| Race Impurted | 4.0% | 7.4% | 12.3% | 6.9% | 7.1% | 5.9% | 3.7% |

| Hispanic Impurted | 4.4% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 7.5% | 5.6% | 6.2% | 4.1% |

| Sex Impurted | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 1.7% | 0.9% |

| Age Impurted | 3.7% | 5.8% | 5.9% | 6.7% | 5.7% | 5.3% | 3.5% |

| Relationship Impurted | 2.1% | 3.6% | 3.9% | 4.2% | 2.8% | 3.5% | 2.0% |

| Housing Imputations | |||||||

| Vacancy Impurted | 2.6% | 4.7% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 4.0% | 5.7% | 3.1% |

| Tenure Impurted | 4.8% | 8.9% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 5.8% | 8.0% | 5.1% |

| Source: Census 2000 Tabulation From Summary File 1. | |||||||

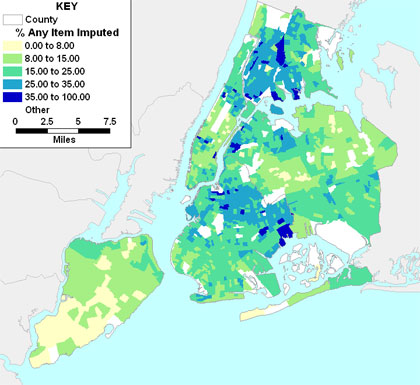

As to imputation for persons, some 20 percent of New York City's 2000 population had at least one item imputed, compared with 10.8 percent for the United States as a while For example, in New York City 11.3 percent of people had their race imputed, versus 5.2 percent for the United States . In the Bronx, the figures are 26.4 percent for any imputation, and 16.0 percent for race..

Imputation varies widely throughout the city, as the table and map show. Areas with high proportions of poor and minority households, such as much of the Bronx, Bedford Stuyvesant, Flatbush and Harlem, as well as heavily immigrant area like Northwest Queens have high levels of imputation. In most of Staten Island and parts of Queens, and of Manhattan levels of imputation are low.

<br/ >

<br/ >

Imputation makes up for many of the problems in data collection, including non-response and inaccurate or misleading information. It improves the quality of the census and the overall results by filling in holes and fixing other problems.

Since 1980, many have argued for statistical adjustment of the Census based upon sampling of the "hard to count" population. The Supreme Court has ruled against adopting this approach. The census has used imputation and allocation since 1960. So in a later ruling the court found that such methods were a legitimate means to improve the count.

What then of the 2010 census? First, it seems to have done even better in New York than the 2000 Census. Like the 2000 census, 2010 will prove to be better than the 1990 census, which missed on the order of 400,000 New Yorkers. Second, the various quality control methods will help assure accurate information. Third, the use of allocation and imputation means that even where there are gaps or inconsistencies in the collected data, the data will be improved, so the census will be even more reliable. In short, the 2010 Census is shaping up to be very accurate and reliable.

You can count on it!

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Likely to Offer Accurate Count of New Yorkers

Photo by Quinn Dombrowski

The 2010 census appears to be on its way to be a major success for New York City. We should be grateful for the unprecedented engagement of community, neighborhood and ethnic organizations, as well as adequate funds for communication, outreach and advertising. This all led to a substantial increase in the rate of initial mail response for New Yorkers. When the state population counts that determine the number of seats in Congress are released on Dec. 28t and the block level data for reapportionment for legislative districts are released in March, New York City should do quite well.

The initial response rate rose from 57 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2010 in New York City. The overall national rate stayed the same at 72 percent.

The increased initial participation in the city means both better data and cheaper data collection. When people respond to the initial mailing, the Census Bureau does not have send out enumerators to knock on doors and collect the information, saving money.

While some households that do not respond become "hard to count," the largest fraction of households visited by enumerators easily provided information when contacted, some even apologizing for not sending in their form on time. Other housing units whose residents did not respond proved to be vacant. Enumerators revisited any vacant units to confirm that no one lived there.

Filling in the Gaps

Of course, in any huge operation like the census there are bound to be glitches here and there, but the Census Bureau established built in checks to assure accuracy. Most of the error and difficulties encountered by some census enumerators will be corrected during the quality control phase. For instance, any home that had an incorrect address was rechecked, and a small sample of households is being reinterviewed to validate the accuracy of the original count. Checks also exist to eliminate duplicate responses for those who filled out the form in more than one residence.

Despite the relative success and the efforts at quality control, some groups are very difficult to interview, leaving some missed homes and some incorrect or inconsistent information. To address this, the Census Bureau has a number of procedures it follows when it cannot get an interview or the response is either not complete or inconsistent with other responses from the household. These technique, based on statistical methods, come under the heading "imputation and allocation. "

There are two types of imputation and allocation:

Whole unit imputation comes into play when there is no answer for a unit known to be occupied. In such cases, the census applies what is known as the "hot deck" procedure and determines -- or imputes -- the characteristics of the household from those of other nearby households.

The term "hot deck" harkens back to the time when computers used punched cards. The hot deck contained information on those who were recently tabulated from the same neighborhood living in the same type of unit. Such data still exists -- even if the hot deck does not -- and is used to fill in information on nearby, missing with similar known characteristics.

The other method is "item and person allocation," where a household has provided answers, but they either incomplete answers or include inconsistencies. Here the information on the occupants that do exist is used to impute, much as the "hot deck'" was for the vacant unit So one can impute sex by using first name, if it is known. A Committee of the National Academy of Sciences discussed and reviewed these census procedures.

The New York Data

In the past, New York City has relied more on imputed data than the U.S. as whole has. The table below presents information on the imputation of basic characteristics in the city in 2000. The census reported that 4.7 percent of the housing units' vacancy statuses were imputed. In 8.9 percent, it imputed whether or not the unit was owned or rented. This compares with 2.6 percent for vacancy and 4.8 percent for owned or rented nationally.

| ' | United States | New York City | Bronx | Kings | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island |

| Overall Person Imputations | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Any Item Imputed | 10.9% | 20.0% | 26.4% | 22.3% | 16.5% | 17.8% | 10.6% |

| Population Substituted | 1.2% | 3.9% | 5.7% | 5.4% | 1.2% | 3.4% | 1.5% |

| ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Specific Imputations | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| One or more items Impurted | 9.6% | 16.1% | 20.7% | 16.9% | 15.2% | 14.3% | 9.1% |

| Race Impurted | 4.0% | 7.4% | 12.3% | 6.9% | 7.1% | 5.9% | 3.7% |

| Hispanic Impurted | 4.4% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 7.5% | 5.6% | 6.2% | 4.1% |

| Sex Impurted | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 1.7% | 0.9% |

| Age Impurted | 3.7% | 5.8% | 5.9% | 6.7% | 5.7% | 5.3% | 3.5% |

| Relationship Impurted | 2.1% | 3.6% | 3.9% | 4.2% | 2.8% | 3.5% | 2.0% |

| ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Housing Imputations | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Vacancy Impurted | 2.6% | 4.7% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 4.0% | 5.7% | 3.1% |

| Tenure Impurted | 4.8% | 8.9% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 5.8% | 8.0% | 5.1% |

| Source:' Census 2000 Tabulation From Summary File 1. | |||||||

As to imputation for persons, some 20 percent of New York City's 2000 population had at least one item imputed, compared with 10.8 percent for the United States as a while For example, in New York City 11.3 percent of people had their race imputed, versus 5.2 percent for the United States . In the Bronx, the figures are 26.4 percent for any imputation, and 16.0 percent for race..

Imputation varies widely throughout the city, as the table and map show. Areas with high proportions of poor and minority households, such as much of the Bronx, Bedford Stuyvesant, Flatbush and Harlem, as well as heavily immigrant area like Northwest Queens have high levels of imputation. In most of Staten Island and parts of Queens, and of Manhattan levels of imputation are low.

<br/ >

<br/ >

Imputation makes up for many of the problems in data collection, including non-response and inaccurate or misleading information. It improves the quality of the census and the overall results by filling in holes and fixing other problems.

Since 1980, many have argued for statistical adjustment of the Census based upon sampling of the "hard to count" population. The Supreme Court has ruled against adopting this approach. The census has used imputation and allocation since 1960. So in a later ruling the court found that such methods were a legitimate means to improve the count.

What then of the 2010 census? First, it seems to have done even better in New York than the 2000 Census. Like the 2000 census, 2010 will prove to be better than the 1990 census, which missed on the order of 400,000 New Yorkers. Second, the various quality control methods will help assure accurate information. Third, the use of allocation and imputation means that even where there are gaps or inconsistencies in the collected data, the data will be improved, so the census will be even more reliable. In short, the 2010 Census is shaping up to be very accurate and reliable.

You can count on it!

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Discuss this Article

Other Related Articles:

Under a New Name, Census Data Stands Ready for Perusal (2011-08-11)

Census Wounded City's Pride but Probably Got the Numbers Right (2011-04-26)

Census Could Set Off Major Redistricting in State (2010-02-25)

Documenting the Undocumented (2009-06-18)

The Citizen (2009-04-20)

New York and the Fight Over the 2010 Census (2009-02-25)

Will the 2010 Census "Steal" New Yorkers? (2007-12-24)

Visit the complete Topic Archives

Census Could Set Off Major Redistricting in State

Numbers denote State Senate district, To find out who represents the district, see the table below.

Your census form will arrive in the mail around March 14 unless, of course, you live in a New York state or a federal prison, where it will be distributed by the warden and collected in a sealed envelope and sent to the Census Bureau in Washington. How that return is counted -- and indeed if it is counted at all -- will have a major impact on power and politics in New York state over the next decade.

Since the 2000 census, the Census Bureau has estimated massive population shifts that should be confirmed by the results of the 2010 census. The bottom line is all legislative bodies across the country will face massive redistricting challenges.

In New York, the State Senate will likely move further into Democratic hands, particularly if the Democrats maintain control after the 2010 election. But whoever ends up in charge of redistricting will find it virtually impossible to ignore the fact that the population and power shift from upstate to downstate continues unabated.

Revised congressional, Senate and Assembly districts must be drawn to accommodate this and other population shifts. They also must take into account the commands of the Voting Rights Act to district in a way that allows of minority voters to exercise influence in the election of representatives. (Redistricting in New York is done by both houses of the legislature as a bill that then must be signed by the governor to take effect. If the legislative process fails, courts can intervene after a suit is filed.)

Finding Everyone

The census will provide the raw material for redistricting. The main clients for the Census Bureau are Congress, the state legislatures and the governors in the United States. A variety of factors will affect the outcome of the census, as well how it is used to divide the state.

Efforts are underway to count the so-called "hard to count" parts of New York City. Mostly the poor and immigrants reside in such neighborhoods. During the Census 2000, some upscale African American neighborhoods did not participate very well, at least initially. On the other hand, some immigrant areas did better than expected. Apparently, some data may have been falsified by workers struggling to meet what they saw as unrealistic deadlines.

Since substantial efforts are underway in New York City to count the "hard to count," one should expect that the 2010 census will do about as well as did the 2000 census.

People Power

What, then, to expect in terms of the Congress, the Senate and the Assembly for 2012?

The State Assembly is so overwhelmingly Democratic that the chance for major political change based upon population changes seems remote. Nonetheless, many members will find that they will represent significantly changed districts.

As for Congress, an analysis that I did for Real Elections Project shows that New York State is likely to lose at least one congressional seat, and that Louise Slaughter's Rochester area district is very under-populated. Nevertheless, the loss of one seat will require the redrawing of every congressional district so many areas will face major changes.

The real battle, however, will be in the New York State Senate. Last time around, with the Republicans facing the loss of seats in their upstate base, the GOP crafted a plan that it sprung on Democratic legislators and public at the last moment -- after numerous mandated public hearings were over. To avoid having to cut a Republican seat, the plan added a new seat to the Senate and carefully distributed the rest of the population shift to dilute New York City’s power. (By creating an even number of Senate seats, the plan bears some responsibility for the deadlock that paralyzed the Senate last summer.)

If the GOP should regain control of the Senate in time for redistricting, they may try a similar scheme. But such efforts would run into a difficult demographic reality. This decade, as in the last, population generally grew in the city and its environs and declined upstate. The accompanying maps and table, based upon population figures from the 2008 American Community Survey and estimated through 2010, show that almost all of the upstate districts have lost people, while most of the downstate districts, including New York City, the northern suburbs and Long Island gained population.

This means that to if districts are to be of relatively equal size, seats and voting power should shift away from upstate. Redistricting experts measure the departure from the ideal (total population equality) in terms of how much a specific district deviates in size from the average district. Since districts should be as equal as possible, measuring the degree of inequality is expressed as "deviation." Any plan with a total deviation (the difference between the largest positive and negative deviation) greater than 10 percent is legally suspect. Thus, deviations greater than 5 percent positive and negative are cause of serious concern.

Using this yardstick, 17 upstate districts have populations that are more than 5 percent below the ideal size, while 14 downstate and Long Island districts have deviations higher than plus 5 percent. This result is not at all surprising, since during the last redistricting round, the GOP majority did everything possible to pack population downstate and spread it out upstate. The party's stratagems prevented http://www.gothamgazette.com/article/demographics/20020701/5/591 a massive redistricting upstate in 2002, but may not be able to avoid it in 2012.

Prisoners Upstate

Further exacerbating the population trend is the recent announcement that the Census Bureau will make data available so that the prisoners (and other so-called group quarters residents) might be excluded from the totals for state and local redistricting. The bureau will identify where such facilities are and how many people occupy them.

New York counts prisoners as being residents of the place where they are incarcerated -- not the community they came from. Given that most prisons are upstate and many prisoners are from the five boroughs, this inflates the upstate population. Any change in that would have the effect of decreasing the number of people counted for redistricting upstate even further.

Many advocates and a recent court decision, as well as a National Academy of Sciences report, support the idea that prisoners are really not residents of prisons, since they generally do not plan to remain in the surrounding community after they are released. Instead, they should be counted where they were living before they were incarcerated. The census data would only allow states to not count prisoners in prison. It would not solve the problem of where they should be counted. (The impact of just excluding prisoners is estimated in the attached Table, as well.)

State Sen. Eric Schneiderman has introduced legislation that would force the state to count prisoners as residents of their prior homes, using Department of Corrections Data. The bill's fate is uncertain.

In short, New York State faces massive redistricting once the 2010 census is released in the first quarter of 2011. As those downstate work to get their "hard to count" population enumerated, upstate residents and voters can feel even more of their power slipping away. If the State Senate joins the Assembly in being solidly in Democratic hands with stronger downstate representation, it is inevitable that government appropriations will follow this power shift. So, as you complete your census form, remember that the data generated have a tremendous impact on the distribution of, power and money.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

| District | Senator | Party | First Elected | Residence | Estimated Population 2010 | Estimated Deviation | % Estimated Deviation | Population | Estimated Change | Estimated % Change | Estimated Prisoners | Estimated Deviation Excluding Prisoners |

| 1 | Kenneth LaValle | R | 1976 | Port Jefferson | 348,512 | 32,383 | 10.24% | 305,238 | 43,274 | 14.2% | 0 | 10.6% |

| 2 | John J. Flanagan | R | 2002 | East Northport | 348,742 | 32,613 | 10.32% | 305,951 | 42,791 | 14.0% | 0 | 10.6% |

| 3 | Brian X. Foley | D | 2008 | Blue Point | 313,863 | -2,266 | -0.72% | 305,989 | 7,874 | 2.6% | 0 | -0.4% |

| 4 | Owen H. Johnson | R | 1972 | West Babylon | 333,382 | 17,253 | 5.46% | 305,962 | 27,420 | 9.0% | 0 | 5.8% |

| 5 | Carl Marcellino | R | 1995 | Syosset | 325,865 | 9,736 | 3.08% | 305,450 | 20,415 | 6.7% | 0 | 3.4% |

| 6 | Kemp Hannon | R | 1989 | Garden City | 316,021 | -108 | -0.03% | 306,033 | 9,988 | 3.3% | 0 | 0.3% |

| 7 | Craig Johnson | D | 2007 | Port Washington | 327,036 | 10,907 | 3.45% | 305,501 | 21,535 | 7.0% | 0 | 3.8% |

| 8 | Charles Fuschillo | R | 1998 | Merrick | 311,252 | -4,877 | -1.54% | 305,908 | 5,344 | 1.7% | 0 | -1.3% |

| 9 | Dean Skelos | R | 1984 | Rockville Centre | 316,182 | 53 | 0.02% | 305,990 | 10,192 | 3.3% | 0 | 0.3% |

| Long Island Total | 2,940,856 | 95,695 | ||||||||||

| 10 | Shirley Huntley | D | 2006 | Jamaica | 339,608 | 23,479 | 7.43% | 318,481 | 21,127 | 6.6% | 0 | 7.7% |

| 11 | Frank Padavan | R | 1972 | Bellerose | 339,018 | 22,889 | 7.24% | 318,482 | 20,536 | 6.4% | 0 | 7.6% |

| 12 | George Onorato | D | 1983 | Astoria | 302,555 | -13,574 | -4.29% | 318,484 | -15,929 | -5.0% | 483 | -4.2% |

| 13 | Vacant (Monserrate) | Was D | 336,495 | 20,366 | 6.44% | 318,484 | 18,011 | 5.7% | 0 | 6.8% | ||

| 14 | Malcolm Smith | D | 2000 | St. Albans | 333,981 | 17,852 | 5.65% | 318,481 | 15,500 | 4.9% | 0 | 6.0% |

| 15 | Joseph Addabbo Jr. | D | 2008 | Ozone Park | 326,700 | 10,571 | 3.34% | 318,484 | 8,216 | 2.6% | 0 | 3.6% |

| 16 | Toby Ann Stavisky | D | 1999 | Flushing | 331,878 | 15,749 | 4.98% | 318,483 | 13,395 | 4.2% | 0 | 5.3% |

| 17 | Martin Malave Dilan | D | 2002 | Bushwick | 329,649 | 13,520 | 4.28% | 311,260 | 18,389 | 5.9% | 0 | 4.6% |

| 18 | Velmanette Montgomery | D | 1984 | Brooklyn | 349,252 | 33,123 | 10.48% | 311,260 | 37,992 | 12.2% | 0 | 10.8% |

| 19 | John Sampson | D | 1996 | Brooklyn | 319,165 | 3,036 | 0.96% | 311,258 | 7,907 | 2.5% | 0 | 1.3% |

| 20 | Eric Adams | D | 2006 | Brooklyn | 316,927 | 798 | 0.25% | 311,259 | 5,668 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.5% |

| 21 | Kevin Parker | D | 2002 | Brooklyn | 332,960 | 16,831 | 5.32% | 311,259 | 21,701 | 7.0% | 0 | 5.6% |

| 22 | Martin Golden | R | 2002 | Bay Ridge | 316,595 | 466 | 0.15% | 311,260 | 5,335 | 1.7% | 0 | 0.4% |

| 23 | Diane Savino | D | 2004 | Staten Island | 326,256 | 10,127 | 3.20% | 311,259 | 14,997 | 4.8% | 0 | 3.5% |

| 24 | Andrew Lanza | R | 2006 | Staten Island | 347,083 | 30,954 | 9.79% | 311,258 | 35,825 | 11.5% | 767 | 9.9% |

| 25 | Dan Squadron | D | 2008 | Brooklyn | 335,843 | 19,714 | 6.24% | 311,258 | 24,585 | 7.9% | 0 | 6.5% |

| 26 | Liz Krueger | D | 2002 | New York | 346,965 | 30,836 | 9.75% | 311,260 | 35,705 | 11.5% | 0 | 10.1% |

| 27 | Carl Kruger | D | 1994 | Brooklyn | 315,681 | -448 | -0.14% | 311,259 | 4,422 | 1.4% | 0 | 0.2% |

| 28 | Jose M. Serrano | D | 2004 | Spanish Harlem | 328,693 | 12,564 | 3.97% | 311,261 | 17,432 | 5.6% | 0 | 4.3% |

| 29 | Thomas Duane | D | 1998 | New York | 364,179 | 48,050 | 15.20% | 311,260 | 52,919 | 17.0% | 350 | 15.4% |

| 30 | Bill Perkins | D | 2006 | Harlem | 325,817 | 9,688 | 3.06% | 311,263 | 14,554 | 4.7% | 660 | 3.2% |

| 31 | Eric Schneiderman | D | 1998 | Washington Heights | 291,273 | -24,856 | -7.86% | 311,257 | -19,984 | -6.4% | 0 | -7.6% |

| 32 | Ruben DĂaz | D | 2002 | Soundview | 342,758 | 26,629 | 8.42% | 311,260 | 31,498 | 10.1% | 0 | 8.7% |

| 33 | Pedro Espada Jr. | D | 2008 | Bedford Park | 316,101 | -28 | -0.01% | 311,258 | 4,843 | 1.6% | 0 | 0.3% |

| 34 | Jeffrey Klein | D | 2004 | Throgs Neck | 325,052 | 8,923 | 2.82% | 311,251 | 13,801 | 4.4% | 0 | 3.1% |

| 35 | Andrea Stewart-Cousins | D | 2006 | Yonkers | 317,719 | 1,590 | 0.50% | 311,016 | 6,703 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.8% |

| 36 | Ruth Hassell-Thompson | D | 2000 | Williamsbridge | 324,061 | 7,932 | 2.51% | 311,259 | 12,802 | 4.1% | 186 | 2.8% |

| 37 | Suzi Oppenheimer | D | 1984 | Mamaroneck | 322,366 | 6,237 | 1.97% | 310,865 | 11,501 | 3.7% | 1,811 | 1.7% |

| Downstate Total | 9,204,631 | 353,019 | ||||||||||

| 38 | Thomas Morahan | R | 1999 | Clarkstown | 337,005 | 20,876 | 6.60% | 320,433 | 16,572 | 5.2% | 590 | 6.7% |

| 39 | Bill Larkin | R | 1990 | New Windsor | 326,445 | 10,316 | 3.26% | 304,986 | 21,459 | 7.0% | 0 | 3.6% |

| 40 | Vincent Leibell | R | 1994 | Patterson | 323,184 | 7,055 | 2.23% | 299,689 | 23,495 | 7.8% | 1,054 | 2.2% |

| 41 | Stephen Saland | R | 1990 | Poughkeepsie | 306,888 | -9,241 | -2.92% | 298,789 | 8,099 | 2.7% | 5,298 | -4.3% |

| 42 | John Bonacic | R | 1998 | Mount Hope | 318,665 | 2,536 | 0.80% | 298,208 | 20,457 | 6.9% | 4,660 | -0.4% |

| 43 | Roy McDonald | R | 2008 | Wilton | 312,604 | -3,525 | -1.11% | 300,304 | 12,300 | 4.1% | 0 | -0.8% |

| 44 | Hugh Farley | R | 1976 | Schenectady | 312,531 | -3,598 | -1.14% | 300,641 | 11,890 | 4.0% | 1,091 | -1.2% |

| 45 | Betty Little | R | 2002 | Queensbury | 298,855 | -17,274 | -5.46% | 295,991 | 2,864 | 1.0% | 10,391 | -8.5% |

| 46 | Neil Breslin | D | 1996 | Albany | 296,682 | -19,447 | -6.15% | 294,026 | 2,656 | 0.9% | 0 | -5.9% |

| 47 | Joseph Griffo | R | 2006 | Rome | 283,051 | -33,078 | -10.46% | 290,288 | -7,237 | -2.5% | 2,850 | -11.1% |

| 48 | Darrel Aubertine | D | 2008 | Cape Vincent | 293,423 | -22,706 | -7.18% | 289,932 | 3,491 | 1.2% | 4,233 | -8.3% |

| 49 | David Valesky | D | 2004 | Oneida | 285,279 | -30,850 | -9.76% | 290,514 | -5,235 | -1.8% | 2,305 | -10.2% |

| 50 | John DeFrancisco | R | 1992 | Syracuse | 289,462 | -26,667 | -8.44% | 291,064 | -1,602 | -0.6% | 0 | -8.2% |

| 51 | James Seward | R | 1986 | Milford | 288,707 | -27,422 | -8.67% | 288,702 | 5 | 0.0% | 2,486 | -9.2% |

| 52 | Thomas W. Libous | R | 1988 | Binghamton | 282,392 | -33,737 | -10.67% | 290,843 | -8,451 | -2.9% | 205 | -10.5% |

| 53 | George H. Winner Jr. | R | 2004 | Elmira | 289,204 | -26,925 | -8.52% | 292,782 | -3,578 | -1.2% | 2,426 | -9.0% |

| 54 | Michael Nozzolio | R | 1992 | Fayette | 294,361 | -21,768 | -6.89% | 289,191 | 5,170 | 1.8% | 2,841 | -7.5% |

| 55 | James Alesi | R | 1996 | East Rochester | 324,059 | 7,930 | 2.51% | 301,947 | 22,112 | 7.3% | 0 | 2.8% |

| 56 | Joseph Robach | R | 2002 | Greece | 277,400 | -38,729 | -12.25% | 301,862 | -24,462 | -8.1% | 81 | -12.0% |

| 57 | Catharine Young | R | 2005 | Olean | 282,090 | -34,039 | -10.77% | 293,587 | -11,497 | -3.9% | 2,962 | -11.4% |

| 58 | William Stachowski | D | 1981 | Lake View | 282,681 | -33,448 | -10.58% | 298,637 | -15,956 | -5.3% | 0 | -10.3% |

| 59 | Dale Volker | R | 1975 | Depew | 288,895 | -27,234 | -8.61% | 292,189 | -3,294 | -1.1% | 7,161 | -10.6% |

| 60 | Antoine Thompson | D | 2006 | Buffalo | 273,986 | -42,143 | -13.33% | 298,636 | -24,650 | -8.3% | 0 | -13.1% |

| 61 | Michael Ranzenhofer | R | 2008 | Clarence | 295,493 | -20,636 | -6.53% | 298,490 | -2,997 | -1.0% | 0 | -6.3% |

| 62 | George Maziarz | R | 1995 | Newfane | 291,182 | -24,947 | -7.89% | 301,784 | -10,602 | -3.5% | 2,281 | -8.3% |

| Upstate Total | 7,454,525 | -448,700 | ||||||||||

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

New York's Now Beleaguered Financial Workforce - Tables

Table 1.

|

|||||

| Finance |

230,366

|

247,143

|

7.28%

|

||

| Other Sectors |

1,380,109

|

1,571,381

|

13.86%

|

||

| Percent in Finance |

14.30%

|

13.59%

|

|||

| Outer Boroughs | |||||

| Finance |

39,717

|

39,562

|

-0.39%

|

||

| Other Sectors |

1,115,297

|

1,387,362

|

24.39%

|

||

| Percent in Finance |

3.44%

|

2.77%

|

|||

| New York City | |||||

| Finance |

270,083

|

286,705

|

6.15%

|

||

| Other Sectors |

2,495,406

|

2,958,743

|

18.57%

|

||

| Percent in Finance |

9.77%

|

8.83%

|

|||

| Rest of Metro Area | |||||

| Finance |

163,613

|

188,191

|

15.02%

|

||

| Other Sectors |

3,147,039

|

3,344,789

|

6.28%

|

||

| Percent in Finance |

4.94%

|

5.33%

|

|||

| Total NY Metro | |||||

| Finance |

433,696

|

474,896

|

9.50%

|

||

| Other Sectors |

2,495,425

|

2,958,762

|

18.57%

|

||

| Percent in Finance |

7.14%

|

7.01%

|

Table 2.

|

Table 3.

Table 4.

|

New York's Now Beleaguered Financial Workforce

Photo (cc) asterix611

New York City is reeling from the Crash of 2008. Unemployment in the city has increased from 5.1 percent in May 2008 to 8.9 percent in May 2009. New York City's Independent Budget Office predicts a substantial decline in employment and revenue for the next three fiscal years.

The Bloomberg boom has become the Bloomberg bust, and it may be with us for the next several years. Furthermore, as the city recovers it seems unrealistic to expect that the finance sector, the city's economic driver, will soon regain its full luster. It may well be a long, long time before it once again spins off new high paying jobs in finance, much less in industries that cater to finance and generates the billions in tax revenues that the city and state have come to depend upon. A close look at the finance industry in New York reveals not only what everyone know -- that it paid well -- but that the largesse extended to people in a variety of occupations, who will now all bear the brunt of its decline.

Blowing Up the Bubble

Through 2007, the finance sector rode a wave fueled by its packaging of mortgages as derivatives, creating and selling insurance for these mortgages and securities, rating these instruments as triple A, and selling them through financial institutions to various funds and institutions worldwide. Indeed, many in finance made literally millions, some multi-millions, doing this business. The lawyers handling the deals also became wealthy.

As analysts and journalists explore the wreckage wreaked by the finance sector upon the city, the country and global economy, it is now obvious that much of the prosperity was based upon a huge bubble. The bubble generated billions of dollars in bonuses, profits and tax revenues, and thousands of jobs. The growth and prosperity of this sector really began as the city emerged from the crash of 1987, through the 1990s, and rose again after the tech crash in 2000 and 9/11.

Just before the meltdown the finance sector employed some 475,000 full-time workers in the New York metropolitan area, including parts of New Jersey and Connecticut, Long Island and the northern suburbs in New York State. Of these, 287,000 or 64 percent worked in New York City. Of the city workers, 86 percent worked in Manhattan.

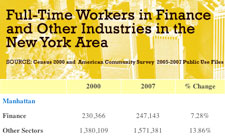

Interestingly, though, while jobs in finance increased by 7 percent from 2001 to 2007, the number of jobs in all other sectors increased by even more. In 2007, jobs in finance accounted for 7.01 percent of all jobs in the metropolitan area, down slightly from 7.14 percent in 200.

Click to enlarge Table 1

(Table 1has information on the full-time employment of workers in the finance sector between 2000 and 2007).

The crash and meltdown have led to the unraveling of much of the finance sector. All investment banks have now become conventional banks, Lehman and Bear Stearns are no more, Merrill Lynch is part of the Bank of America, Wachovia of Wells Fargo and many banks have announced layoffs, and most are now partially owned by the U.S. government. Though Goldman seems to have dodged much of the bullet, as has JP Morgan Chase, the same cannot be said of Citigroup and some of the other large banks, former investment banks, brokerages and insurance companies, such as AIG.

The Finance Workforce

The financial area lost 37,400 jobs in the metropolitan area from May 2008 to May 2009, decreasing 4.7 percent, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has reported. "Over the year, New York City shed the most financial activities jobs since September 2002 with the city's securities, commodity contracts, and investments industry accounting for almost 60 percent of the area's job contraction in the sector," the bureau found.

Click to enlarge Table 2

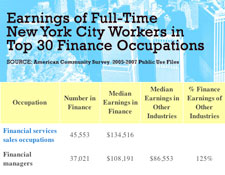

As finance led the city and region into a boom, it is now leading them into the most serious economic downturn since the Great Depression. As Table 2 shows, jobs in finance cover a wide array of occupations. Many jobs are sales jobs; others are directly related to finance and management. For instance, sales was the number one occupation in finance followed by financial managers, and other financial specialists were number three. However the top 30 finance occupations includes computer professionals; secretaries; software developers; office supervisors; bank tellers; guards, watchmen and doorkeepers; receptionists and other garden variety occupations. Obviously, the need for salesman and managers has substantially declined. But the reductions in finance also include the other ancillary occupations that supported the industry.

In general, as table 3, above, shows, these jobs in finance paid better than similar work in other sectors.

Grouping the occupations, one finds that for all types of jobs, the median earnings in finance were higher, often substantially higher than in other sectors. Indeed, for all full time workers, finance median earnings were more than double those in other industries, and for the top 10 percent of earners, finance paid almost five times as much as other sectors. Many finance jobs were in sales and management, two areas where earnings were much higher for those in finance, however all workers were paid more in this sector, even support staff, which paid 14 percent more than their counterparts in other fields.

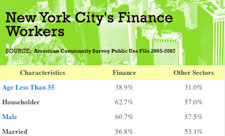

Click to enlarge Table 4

Aside from being very highly paid, compared to others, those working in finance were different in other ways, as Table 4 shows. They are younger than the average New York City worker and more likely to be male, live with a spouse and reside in an owner occupied dwelling. More of them are white and Asian and fewer are black, Hispanic or multi-racial. They are less likely to be foreign born and much more likely to be college grads -- 69.4 percent versus 42.3 percent. In short, they were richer, whiter, and more educated than other city workers.

The decline of the finance sector is now in full swing. Already, about 10 percent of the finance jobs have been lost. More are being lost daily. Manhattan and the tonier sections of Brooklyn have faced sharp declines in housing prices, and even in rent. Laid-off financial executives and sales people are looking for other lines of work.

The collateral damage of both the bubble and bust will affect all New Yorkers. Those such as high-end car dealers, real estate developers and the like, along with restaurant owners and even storefronts selling Chinese take-out already have been affected. Though some New Yorkers may get satisfaction from seeing the finance sector and its rich employees take a beating, in fact, all of us will be worse off from the crash. Because even if the gains may be seen as "ill gotten," we all depended upon them. Replacing or rebuilding the sector will not bring back the days of wine and roses. Soon the boom of the early 21st century may be just a distant memory, as we all learn to live with much more straitened circumstances.

Andrew Beveridge, professor of sociology at Queens College and the Graduate Center of CUNY and instigator of www.socialexplorer.com, has been in charge of the demographic topic page since January 2001.

Documenting the Undocumented

Photo (c) Dave Ward

At a community center in Sunnyside, Rosalva Rodriguez, a Colombian immigrant, sits working on a quilting pattern. The room is filled with the sound of consecutive Bingo numbers, called in both Spanish and English to an elderly crowd.

Rodriguez of Woodhaven talks openly about her immigration status. She says she has a green card, and her sons are both citizens. She's extremely knowledgeable about the upcoming 2010 Census, citing its implications and benefits, and says that she will, of course, participate.

But Rodriguez is a rarity among New York's hard-to-count immigrant community.

Many are scared to share their information, reported the U.S. Census Bureau at a recent press briefing. But on a survey where population is directly tied to federal funding and congressional representation, New York officials and organizations want to ensure every person is accounted for. In particular, calculating the city's estimated 500,000 undocumented immigrants has proven to be a substantial hurdle in achieving accuracy. For many of these individuals, the 2010 Census represents a murky unknown -- a vast question mark, which many fear could lead to a one-way ticket home.

"They are scared to participate because they think this survey will work to deport them," says Rodriguez in Spanish.

Adds a woman quilting beside her, "They think the information collected from the census will later go to immigration [enforcement], and then immigration will tell on them."

This is the exact mentality the Census Bureau is trying to combat. On June 2, a coalition of immigrant organizations, government officials and census representatives held a press conference for ethnic and community media.

The panel urged the 50-some reporters to get the word out to their constituents, allay their fears and promote the benefits of taking part in the national count.

"I want to assure you that participating in the census is safe," said Allison Cenac, senior officer in the New York regional census office. "We just want to get New York City counted… No one will be deported or lose their homes."

Why Do It?

Not only safe, officials said it is highly advantageous for undocumented immigrants to take part, since their involvement would lead directly to increased federal monies for services used daily by non-citizens, such as subways, hospitals and schools. Officials reiterated that the information would not be handed to other government agencies, and that sharing of census data was a punishable offense.

Though the census won't be mailed out until March of next year, the bureau has already started an aggressive campaign to reach undocumented individuals, according to Stacey Cumberbatch, the New York City census coordinator. They've partnered with local grassroots and immigration nonprofits to tailor their outreach to specific ethnic and religious communities. In addressing the wide range of languages -- 146 are spoken in city public schools -- the Census Bureau has translated their website into 18 and will mail out language guides on how to obtain a form in 59 languages, said Cumberbatch.

To increase response among all demographics, the form is the shortest in a participant's census history, and it does not include questions about social security numbers or income. Census representatives are also stressing the role of ethnic and community newspapers in getting the word out.

"No one can get this information to your communities like you guys can," said Juana Ponce de Leon, the executive director of New York Community Media Alliance.

By using these trusted, local mediums as outlets, the bureau is hoping they will get the message across to hard-to-count communities. If not, said one official, the effect would be "devastating."

"If undocumented folks do not participate they do not exist," said Cumberbatch.

Why Not?

An overwhelming number of organizations and politicians have heeded the call of the Census Bureau and have urged participation in their communities.

But Reverend Miguel Rivera, chairman and chief executive officer of the National Coalition of Latino Clergy and Christian Leaders, is leading a boycott against the national count. His organization represents over 20,000 pastors in 34 states, who are asking their undocumented constituents to protest the census unless "comprehensive immigration reform" is established first. Rivera claimed one million members, about a quarter of the group's affiliates, have already expressed support.

"Yes, our presence here and an accurate count are very important, but only if we have the same rights as everyone else," said Rivera. "The reality is, for the last eight years, and many more, we have been waiting for some solution."

Rivera said a boycott would have occurred with or without his help. He argued, however, that an official protest pushed by the coalition would effectively "bring the immigration issue to the forefront of dialogue" and "finally put pressure on Congress." Additionally, he claimed there are no benefits for the participation of undocumented immigrants in the census, aside from allocation of resources to public schools.

Census organizers and community groups promoting an accurate count are calling the movement counter-productive and illogical.

"It's slightly absurd," said Alan Kaplan, civic and electoral participation program coordinator for the New York Immigration Coalition. "It will lead to an undercount of a population which desperately needs to be counted correctly in order to show their power, their strength, and get their federal dollars."

Marlene Cintron, executive director of the New York State Senate Puerto Rican/Latino Caucus, echoed the point, emphasizing the political value of the census.

"This effort threatens to undermine our badly needed representation at all levels of government," said Cintron. "It's extremely important that all of us be counted so we receive… a bigger share of individuals that will represent us."

But, Rivera contended, this is the exact point he takes issue with. He said that since undocumented immigrants are counted, yet cannot vote, they are not able to choose who is representing him. The result, he said, is an increase of delegates pushing an anti-immigration agenda in areas with a strong conservative base, like parts of Long Island.

"The people who actually get to vote are the ones who are grateful for that effort from undocumented people," said Rivera.

Back in Sunnyside, Rodriguez says she understands why Latinos would join this boycott, considering restrictive laws and the aggressive policies of agencies like the Immigrations and Customs Enforcement.

"It's logical. It's logical that people think this because they have seen what the government has done," she says. "They have seen two men at the door at four in the morning…" she adds, her voice trailing off.

Kaplan said regardless of the national clergy coalition's support, in the end, their efforts will hurt their own communities.

"Whatever media coverage, whatever their gain, it's going to be discounted by the fact that their communities will be underrepresented."

Counting Everyone

According to a 2008 report by the Pew Hispanic Center, there are 11.9 million "unauthorized immigrants" living in the U.S. Though Hispanics constitute about three quarters of that figure, Kaplan said it's critical that efforts to count non-citizens reach even the smallest factions.

"We're not only dealing with Latinos in the city. We're dealing with small groups who aren't necessarily being reached out to," he said.

Kaplan named other groups like the African population in Staten Island and South Asian and Arab immigrants in Queens -- each present specific challenges to be counted.

Lester Farthing, director of the regional census office, said that the attacks of September 11, 2001 produced a particularly difficult problem for an accurate count.

"We realize our greatest challenge is working against the fears of what happened with 9/11," said Farthing.

Mohammed Razvi, executive director of the Council of Peoples Organization agreed that the aftermath of the attacks created an atmosphere of distrust among South Asians toward the government.

"They already had a misconception and the atrocities that occurred after 9/11 where people were apprehended just because of their name, without a warrant or any wrongdoing made it even more of an uphill battle," he said.

Razvi said this further compounded their tendency of being underrepresented.

"We are so unbelievably undercounted. I think we were undercounted for almost 100,000 people [in 2000]," said Razvi. He offered a reason: "I think this is the misconception of people coming from a third world country that the government coming and taking your information is a dangerous thing."

Razvi is working against this fallacy by holding town meetings, talking to imams and recruiting community members to become census representatives.

Getting the attention of each diverse group, said Cumberbatch, needs a different approach.

"It may be the mosque, it may be the soccer league," she said. "It's where people live, work, play, worship. We try to look at for different groups on how to access."

Don't Look Back

It appears undocumented immigration participation in the 2010 Census comes down to one thing.

"It's trust. That's it and nothing else," said Razvi. "That's the way to move forward. It's unfortunate that these are the communities that need the most services that they are entitled to but lack of involvement in the census hinders the service that they will be given."

Cintron said this is why organizations, politicians and the government have started galvanizing support nine months before the first census is mailed out.

"It's going to impact us for ten whole years and that's why we want to start this now and why we're having this conversation now. We have to figure out ways to get people interested."

New York and the Fight Over the 2010 Census

Gotham Gazette image by Ya-Hsuan Huang

The contretemps over Judd Gregg's aborted nomination to be commerce secretary reveal once again the fault lines over the 2010 census between Republicans and Democrats. Gregg's difference with the administration over economic policy attracted much of the attention, but the census also reportedly played a major role in the whole affair.

The Census Bureau is in the Commerce Department, and the nomination of Gregg, a Republican senator from New Hampshire, prompted an outcry from black and Latino groups who feared a census under Gregg's direction -- in the Senate, he had voted against fully funding the 2000 census --would result in an undercount of minorities and immigrants. In response, the Obama administration guaranteed that it would watch over the census from the White House. That in turn sparked complaints from the GOP and right-wing bloggers about political interference by the Obama administration in census 2010.

Gregg has returned to the Senate, but the controversy over next year's national headcount remains. None of this is surprising or new, since how the 2010 census is conducted will greatly affect the division of power and the allocation of money in New York State and the city, as well as elsewhere in the United States. Framed as neutral counts of the "whole population," the U.S. census, as all censuses, concerns the allocation of political power and money. The 2010 count will:

- Lead to no change or a loss of one or two congressional seats in New York State.

- Affect the distribution of the State Senate and Assembly seats.

- Affect allocations of federal and state funds.

Who gets counted depends on how the counting is done. That has been the source of controversy for decades.

How Many New Yorkers?

The city has claimed an undercount in every census since 1950. Things turned particularly ugly in 1980. A suspicious fire in the census office responsible for counting Bedford-Stuyvesant occurred the weekend before Washington was to send a team to investigate a massive undercount in the area. This and other problems led to a lawsuit demanding an adjustment for the 1980 count.

To resolve the issue, the Census Bureau agreed to add a survey, revisiting some households in person, to make it possible to adjust the 1990 census. Adjusted counts were prepared, and the Census Bureau staff and director recommended using them, but Commerce Secretary Robert Mossbacher, who went on to run George H.W. Bush's reelection campaign in 1992, rejected the plan.

Information also existed to adjust the 2000 Census, but thanks to the work of Kenneth Prewitt, then director of the Census Bureau, and the funding that Judd Gregg and others tried to block, the 2000 census stood without adjustments, a decision with which most professional demographers agreed. The release of the 2000 census made it plain that the 1990 Reagan-Bush census was seriously flawed. especially with respect to populous states with big cities and large minority and immigrant populations.

The Issues in 2010

The census count, however, continues to be mired in controversies. These include: