Back To (Public and Private) School

The back-to-school experience in New York City depends on who you are and where you live. The most obvious distinction is between public and private school. Public schools educate about 1.14 million of the city's kids, or more than 80 percent of the total student-age population. The remaining 266,000 students go to private school.

An analysis of recently released data from the 2000 census confirms what any educator will tell you: Private school kids are far richer and whiter than their public school counterparts.

The schools that many New Yorkers conjure up when they think of "private school" -- Fieldston, Horace Mann, Brearley, Dalton and Collegiate, and perhaps two-dozen other such institutions -- actually serve only a small fraction of those who go to private schools. The vast majority of private school students are enrolled in schools associated with either the New York Archdiocese, which has about 115,000 students in 293 schools in the Bronx, Manhattan and Staten Island (as well some suburbs), or the Brooklyn Diocese, with 70,000 in 178 Brooklyn and Queens schools. There are also a large range of religiously-affiliated schools, including Yeshivas.

The United States Census Bureau makes no distinction between independent private schools and those that are religiously affiliated.

This makes the statistics even more startling.

| 2000 NYC SCHOOL KIDS |

%TOTAL

|

%PUBLICĂŠ

|

%PRIVATEĂŠ

|

| h |

1,409,221

|

1,142,935

|

266,286

|

| h |

h

|

81.1%

|

23.3%

|

| RACE AND HISPANIC STATUSh | |||

| WHITE NON-HISPANIC |

22.8%

|

15.9%

|

52.6%

|

| BLACK NON-HISPANIC |

30.3%

|

32.8%

|

19.4%

|

| AMIND NON-HISPANIC |

0.4%

|

0.4%

|

0.3%

|

| All OTHERS NON-HISPANIC |

12.3%

|

13.3%

|

8.0%

|

| HISPANIC |

34.2%

|

37.6%

|

19.7%

|

| SPEAK NON ENGLISH LANGUAGE AT HOME (FIVE YEARS OLD OR OLDER) | |||

| YES |

48.6%

|

50.3%

|

41.1%

|

| ABILITY TO SPEAK ENGLISH AMONG THOSE WHO SPEAK NON-ENGLISH LANGUAGE AT HOME (FIVE YEARS OLD OR OLDER) | |||

| VERY WELLĂŠ |

67.5%

|

66.6%

|

72.0%

|

| WELLĂŠ |

22.3%

|

23.1%

|

18.3%

|

| NOT WELLĂŠ |

9.0%

|

9.1%

|

8.7%

|

| NOT AT ALL |

1.2%

|

1.2%

|

1.0%

|

| CITIZEN STATUS | |||

| BORN U.SĂŠ |

80.5%

|

78.3%

|

89.9%

|

| BORN OUTLYING |

1.3%

|

1.5%

|

0.4%

|

| ABROAD/AM PAR |

1.0%

|

0.9%

|

1.4%

|

| NATURALIZED CITIZEN |

3.6%

|

3.9%

|

2.2%

|

| NON-CITIZEN |

13.6%

|

15.4%

|

6.1%

|

| HOUSEHOLD TYPE | |||

| FAMILY MARRIED COUPLE |

56.0%

|

51.8%

|

73.9%

|

| FAMILY MALE HEAD |

5.7%

|

6.1%

|

4.0%

|

| FAMILY FEMALE HEAD |

38.0%

|

41.7%

|

21.8%

|

| NON-FAMILY MALE HEAD WITH OTHERS |

0.2%

|

0.2%

|

0.2%

|

| NON-FAMILY FEMALE HEAD WITH OTHERS |

0.2%

|

0.2%

|

0.1%

|

| EMPLOYMENT STATUS BY FAMILY TYPE | |||

| NOT IN FAMILY HOUSEHOLD |

0.3%

|

0.4%

|

0.3%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/BOTH IN LABOR FORCE |

26.8%

|

24.4%

|

37.2%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/HUSB IN LABOR FORCE |

17.6%

|

15.7%

|

25.7%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/WIFE IN LABOR FORCE |

4.2%

|

4.2%

|

4.4%

|

| MARRIED COUPLE/BOTH NILABOR FORCEĂŠ |

7.4%

|

7.6%

|

6.6%

|

| MALE HEAD/IN LABOR FORCE |

3.9%

|

4.1%

|

2.8%

|

| MALE HEAD/NILABOR FORCEĂŠ |

1.8%

|

2.0%

|

1.2%

|

| FEM HEAD/IN LABOR FORCEĂŠ |

21.5%

|

23.1%

|

14.5%

|

| FEM HEAD/NILABOR FORCEĂŠ |

16.5%

|

18.6%

|

7.2%

|

| HOUSEHOLD INCOME | |||

| UNDER $20,000ĂŠ |

29.4%

|

32.5%

|

15.9%

|

| $20,000-29,999ĂŠ |

12.6%

|

13.5%

|

8.7%

|

| $30,000-39,999ĂŠ |

11.5%

|

12.1%

|

8.8%

|

| $40,000-49,999ĂŠ |

9.2%

|

9.3%

|

8.6%

|

| $50,000-74,999ĂŠ |

16.8%

|

16.2%

|

19.7%

|

Private vs. Public School Students

As the chart indicates:

*About 53 percent of private school kids are (non-Hispanic) white, but only 16 percent of public school kids are white.

*Public school kids are twice as likely to come from households with less than $30,000 per year of income. But more than a third of private school kids are from households with incomes above $75,000, while only a sixth of public kids come from such households. Some eight percent of private school kids live in households with incomes above $200,000, while only about one percent of public school kids do.

*The families of private school kids are more intact, with almost three-quarters of them living in married couple families, while little more than half of all public school kids live in such households.

*Private school kids are more likely to use English at home, and more likely to have their parents in the work force.

Neighborhood Differences

This overall demographic portrait of NYC's school kids masks the fact that there are very large variations if sorted by neighborhoods. In Brooklyn, over 60 percent of the kids who live in community board 12, which is in and around the orthodox Jewish area of Borough Park, go to private school, while in community board 4, which includes heavily Hispanic Bushwick, only about 6 percent of kids go to private school.

Generally speaking though, the affluent neighborhoods are the ones with the highest private school enrollment, especially in Manhattan. Only 12 percent of students in Harlem (community board 10) attend private school, while on the Upper East Side (community board 8), it is 66 percent.

Other Manhattan neighborhoods:

Washington Heights - 11 percent

Greenwich Village - 44 percent

East Harlem - 14 percent

Murray Hill - 53 percent

Upper West Side - 39 percent

In Queens, almost all community board districts send close to the city-wide average of 20 percent to private school. In Staten Island, all districts have between 20 and 30 percent of students in private school. In the Bronx only the Co-Op City Throgs Neck area (District 10) has more than 30 percent of its school kids in private schools.

Simply put, areas in Manhattan that have high proportions of whites have high proportions of kids in private school. In the areas of Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens where there are very few white school kids, the proportion of students in private school is much lower. In mixed areas, where there are some white school kids but also blacks or both, then the private schools are much less diverse than the public schools. In all neighborhoods, as with the city as a whole, private school kids are more affluent and come from more intact families than do public school kids.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Counting Drop-Outs

For at least 50 years, business leaders, politicians and parents berated students to “Stay In School.” Dropping out of high school condemned one to a life of economic uncertainty, welfare dependency or worse. Low dropout rates for high schools became a measure of school success, while high dropout rates were signs of failure. Where retention rates determined success, schools were expected to get all students to the goal of a high school diploma.

Recently “accountability” trends in education policy, culminating in the Bush administration’s ”No Child Left Behind” legislative mandate have shifted the focus from dropout rates to test performance. The results of such tests now determine which schools are “failing” and which are “succeeding.” Administrative actions to “restructure” failing schools and to let the students choose other schools hang in the balance. In New York State, the newly revised Regents Exams is to become the graduation standard, despite the recent flap concerning the scoring of the mathematics exam and the recent and the continuing 55 percent passing grade. In effect, New York State and City already grade high schools based upon the students who can be tracked from 9th grade to 12th grade. The percentage of students who graduate in four years is computed. However, students who transfer out often are not found in these figures, and many of them could be dropouts stop-outs or push-outs. Though New York State does not report, “dropout rates” per se, many individual schools often do give their dropout rate. Yet, no school knows its true dropout rate unless it knows where every single non-returning student goes.

Recent stories in the New York Times plainly show that attempts to cut the test failure rate increased the number of students pushed out of school in both New York City and Houston, which is the school district that Lod Paige, US Secretary of Education, used to lead. But the practice of students being dropped from the rolls in Houston and then inaccurately reported as transfers seems also to be popular in New York City. Because of such misleading reporting measuring dropout rates becomes even more elusive. Though a very well known phenomena among education insiders, these discrepancies in reporting dropout rates are hidden from the public.

The Census Bureau provides an excellent measure of dropouts. Instead of asking school administrators for a number saying how many students dropped out and computing a rate based upon enrollment, the census tabulates the number of persons 16 to 19, who do not have a high school diploma and who are not enrolled in school. From this one can easily figure out what the proportion of dropouts or non-attendees there are. According to the 2000 Census one finds that the 11.05 percent dropout rate in NYC is somewhat higher than the New York State rate of 8.77 percent. For non-Hispanic Whites the rate is 4.51 compared to the state rate of 5.31 percent. For Hispanics both the city and state rate is 18.08 percent, while for blacks the rate is 10.65 percent, slightly lower than the state’s 11.33 percent. Simply put, the dropout rate for Hispanics is about four times that for whites in New York City, while the rate for blacks is more than double that for whites.

Though it is based upon the neighborhood or city of residence (census tract or larger area), such a dropout rate becomes a very good measure in a setting where virtually all students go to public schools. Where many chose private or parochial school, the public schools still are the “last resort,” since they are obligated to take all comers. Since it is computed for most census areas, it also can directly compare one jurisdiction with another.

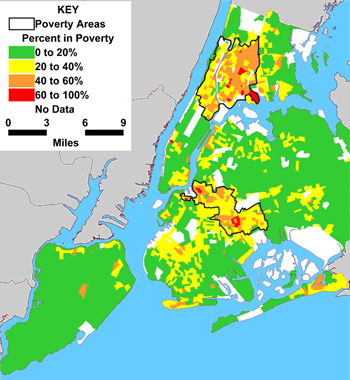

Many educators despise this measure. Indeed, an official at the National Center for Education Statistics, which includes it in their census compilation of school district data, told me that an urban school administrator threatened to kill himself (they assumed he was joking but he was very upset) if they continued to include it. Yet, the patterns that the census finds become quite telling and raise an issue not usually addressed: To what extent is dropping out of school a school- based phenomenon? In other words, to what extent can schools affect dropout rate? Or do some students from some areas just have a high propensity to leave school without a diploma. The accompanying map shows the dramatic variations in dropout rate among neighborhoods. Dropout rates are more than 25 percent in the South Bronx, around Flatbush in Brooklyn, and also in areas of high immigrant concentration in the Corona area in Queens. Can one really expect schools in such areas with highly mobile populations of limited means and many of them non-English speakers, to have dropout rates as low as those in Bayside, Queens in the affluent portions of Manhattan and Staten Island, in Riverdale, and in Forest Hills?

From “stay in school” initiatives to performance tests, officials recognize a high school diploma and the skills associated with it as vital to a student’s full participation in society. The judicial ruling (in PDF format) in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity case makes this plain and a right. The new trend in grading schools by test scores and holding administrators accountable for them may encourage educators to get rid of the poorly performing students. Using the census data on dropouts, soon to be available on a continuous basis from the census bureau, will allow educators and concerned citizens to monitor dropouts more honestly.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

The Vanishing Jews

The number of Jews in New York City fell below one million by 2002, according to the 2002 Community Study by the United Jewish Appeal-Federation of New York. But the real decline may be higher. The recent survey used methods for finding and defining Jews that were different than those used in the 1991 UJA-Federation survey. Indeed, several researchers resigned from the survey's Technical Advisory Committee from the survey, including Bethamie Horowitz, the director of the 1991 study; Charles Kadushin, an emeritus CUNY professor and researcher with the Cohen Center for Jewish Studies at Brandeis, and me. Each concluded that a direct comparison of 1991 and 2002 studies ignores the change in methods. Such an analysis would yield misleading conclusions.

Often such problems are written off as "merely technical," not affecting either the results or conclusions of the study. Here however, the technical disputes go to the heart of the survey. They revolve around two central questions: Who is a Jew? and How many Jews are there in New York City? Though downplayed somewhat in the new survey, which is not called a "population study" but rather a "community study," the fact of the matter is what determines Jewish identity and the size of the population remain central concerns of the organized Jewish community. In earlier topic page updates I discussed counting Muslims, gays, and the population of New York City. It is clear that when groups are put in charge of analyzing their own population, there is a temptation to overestimate their own size and thus their own importance.

WHO IS JEWISH?

Measuring religious or ethnic identification through a survey is not simple. The US Census Bureau, itself, experiences enough difficulty trying to disentangle the concepts of race, national origin, ethnicity and language. The First Amendment bars the Census asking questions about religion. In Great Britain, where the census used self-identification to classify religious affiliation, 390,000 people claimed their religious affiliation to be "Jedi Knight" in 2001. Sparked in part by an internet campaign, this Star Wars religion was just behind Hinduism and just ahead of Sikhism according to census returns in Great Britain.

People who belong to churches, synagogues or mosques usually know their religion. Religious identification becomes problematic for those with a lower level of affiliation. According to the 2002 Jewish Community study only 43 percent of Jewish households in the New York area belonged to a synagogue. For the 2002 study, when telephone interviews were conducted, the interviewer would tell the respondent that they were conducting the Jewish population study sponsored by the Jewish Federation, and then the respondent was asked if he or she were Jewish.

Some researchers think that this introduction and first question would make it more likely that those who considered themselves Jewish would continue the survey, while non-Jews would not continue. If such were the case, then the number of Jews would be overestimated by the survey. The screening introduction and first question were much more neutral in 1991 and thus may have led to a lower number of self-identified Jews in that survey.

HOW MANY JEWS?

According to the 2002 survey Jews make up about 12 percent of the eight million people who live in New York City. To arrive at this number the survey used a very complex set of techniques to "stratify" the sample (One of the four groups to which they divided up their sample was names taken from UJA membership lists). To complete the 4500 interviews used for the survey, they dialed 174,000 different phone numbers a total of 578,000 times. They contacted about 70,000 of these households, and 30,000 provided enough information to classify them as either Jewish or non-Jewish. Of these about 6,000 were classified as Jewish. Interviews were completed with about 75 percent of these. In 1991 the overall response rate was much higher than it was in 2002 if one uses the method for computing response rates favored by the American Association of Public Opinion Research.

To get to the estimates, the group carrying out the UJA Federation survey had to assume that they knew how many people were in each strata, and that the people that they contacted (about 1/5 of those they tried to contact) were the same as those they did not reach. This assumption is unlikely to be true. In fact, of course, they only really knew the size of the stratum made from the federation's list. To figure out how to weight all of the other respondents required using a combination of assumptions and updated census estimates. In summary, as those running the survey in 2002 have argued, it may very well be the case that the 2002 survey provided a better and higher estimate of the Jews living in New York than did the 1991 survey. However, if such is the case, it means that comparing the two surveys underestimates the decline in the Jewish population in New York City.

Despite the significant doubts about how comparable the new survey is to the old one, and how much the Jewish population has declined in New York City, the new study has much valuable information. Even if one is not exactly sure how many Jews there are, one can still learn a great deal about the Jewish community. One can only hope that the survey that the UJA Federation does in 2012 will be comparable to the one done in 2002. Then we will be able to accurately measure how much further the Jewish population may have declined in NYC.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

The Affluent Of Manhattan

The top fifth of Manhattan households received more than 50 times as much income in 1999 as the bottom fifth, according to analyses based upon Census 2000 data. Those in the top 20 percent averaged $366,000, those in the bottom 20 percent, $7,054. Those in the top group saw their average income increase $140,000, while those in the bottom group moved up only seven dollars. Manhattan is now the U.S. county with the highest disparity of income, surpassing the only county ahead of it in 1989, a former leper colony in Hawaii.

In 1989 a household needed at least $95,623 to be in the top 20 percent; by 1999 $115,800 was needed to make it to the top fifth, the highest amount for any county in the United States. When comparing income inequality among all 3,200 counties in the United States, Brooklyn ranks 24th, the Bronx ranks 35th, Staten Island ranks 234th and Queens ranks in the middle of the pack.

Who Is Affluent?

When considering New York City households, the characteristics of the affluent seem to prove F. Scott Fitzgerald's assertion that "the rich are different from us." Of the three million households in New York City in 1999, only about 110,000 (or about one in 26) had incomes above $200,000. The members of those households are very different from the rest of New York City's population. These elite are much more non-Latino white (83 percent compared to 42 percent of the population as a whole), and more likely to include a married couple (64 percent compared to 37 percent). Householders of the affluent households are better educated (79 percent of those over 25 with at least college compared to 28 percent.); more likely employed (93 percent compared to 73 percent), and more likely in managerial, business and finance, or professional and related occupations, (73 percent compared to 36 percent). Fully 56 percent of the affluent households consist of a married couple family with both partners in the labor force, which is 30 percent higher than for other households. The secret to affluence in New York, it seems, consists of having the right educational background (parents may be a big help here), succeeding in the right occupation, and having a spouse that did the same. Children of such couples certainly will have advantages over the children of the less affluent.

Affluent Areas

Digging a little deeper into income distribution for New York City, one finds high concentrations of upper-income households in the Upper East Side. In 1999, households in only 15 of the 2216 tracts in New York City had average incomes above $200,000. Twelve of those 15 tracts were on the Upper East Side, most bordering Fifth Avenue. This is no surprise of course; this is the way it has been for a century.

Two of the other three affluent tracts were in the Soho area near Wall Street, and one was in the Riverdale area in the Bronx that includes the private community of Fieldston, which surrounds the Horace Mann and Fieldston schools, with Riverdale school nearby.

When one walks up Fifth Avenue starting at 49th Street and continuing up to 96th Street every census tract through which one passes had an average income above $200,000 in 1999. This area of Manhattan contains one of the highest concentrations of the truly affluent in the United States. The co-ops along Fifth Avenue often sell for more than $20 million each. This is the neighborhood where a double-sized town house reportedly sold for more than $30 million, some of the doormen wear Ermine collars in the winter. Elite boutiques and other specialty stores dot Madison Avenue, where an appointment is preferred and one must ring a bell to be admitted.

The Upper East Side zip code 10021 generated the most donations for the presidential campaigns of 2000 of any zip code for both Bush and for Gore. Mayor Michael Bloomberg has one of his houses in the area. The Dalton and Brearley schools area located nearby, as is the Whitney, the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan Museum and many art dealers. Of course, Central Park is near, and supporters of the Central Park Conservancy disproportionately come from this area. After all it is their backyard.

Though the affluent are concentrated in the Upper East Side, they also dot many other neighborhoods throughout the city, especially newer neighborhoods in Manhattan (e.g. Tribeca, Chelsea, Battery Park), as well as posh outer borough neighborhoods, including Fieldston, Forest Hills Gardens and Brooklyn Heights. Despite economic uncertainty the predominance of the Manhattan affluent is unlikely to end anytime soon.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

How Different Is New York City From The United States?

The population and demographics of New York City are vastly different from most of the United States. Immigrants from the heartland know that this is so, but many long time city residents forget that New York City is not the United States. The recent annual meeting of the demographers (the Population Association of America) in Minneapolis drove this point home.

IMMIGRATION AND RENEWAL

Compared to the rest of the United States, New York City is a city of immigrants and their children. The United States overall is 11 percent foreign born; New York City is 36 percent foreign born. While 82 percent of those that live in the United States speak only English at home, in New York City only 52 percent do so. New York City draws its immigrants from many different countries, while much of United States immigration is from Mexico. As happened at the turn of the century, immigration renewed New York City, but it is doing so by making the city a place vastly different from the rest of the United States.

At the demographers convention by contrast one of the largest trends seen now affecting virtually every European country and parts of the United States are declining birth rates (especially among the "white" population), increasing the proportion of old people compared to the younger population of workers. Women are not having enough babies to replace the population. A United Nations report indicates that to stem this massive trend the European Union would need 135 million immigrants by 2025.

UNMARRIED MANHATTAN

Though fewer and fewer Americans in general are getting married, New York City is less married than the rest of America, which is probably not a surprise to viewers of Sex and the City. For the United States as a whole, about half of all adult men and women are living with their spouses; for New York City, it is about two-fifths, and in Manhattan alone the figure is not even one-third, which makes it the least paired-up major county in America. In their book, The Case for Marriage, Linda Waite and Maggie Gallagher show that married people generally live longer and better by many measures than single people. Of course one does not know if those who are more likely to be healthy and wealthy get married or if marriage brings one health and wealth.

TRENDS AFFECTING NYC, BUT NOT U.S.A.

A series of other trends also affect New York City much more than other parts of the United States, including concentration of poverty, income inequality and its spatial concentration, the special needs of the immigrant populations, health disparities.

Though demographers at the Population Association of America conference came from across the country and around the world, many of the great demographic training centers are in the Midwest and the West. None are in New York, but the city is home to some of the premier demographic institutions including the Alan Guttmacher Institute, and the Population Council. Sometimes the sort of social science conducted by demographers has been derisively called "dustbowl empiricism" in recognition of its midwestern flavor. One cannot help but be struck by how mid-American most US demographers appear. So maybe it is not a surprise that the demographic trends shaping New York are not central to the concerns of most US demographers.

UPDATE: Racial Classification, the Census, and DNA

The great debate about how to collect data on race, Hispanic status and ethnicity and ancestry continued unabated at the Population Association of America conference. At one session a well-known sociologist and demographer made the stunning suggestion that perhaps a good way to classify the racial background of people in the United States would be to use DNA testing. According to this researcher, one can discover the proportion of various racial origins for a specific person by using DNA testing. He cited various websitesthat offer this service. The results of this test purports to provide racial proportions of one's ancestry based upon various regions of the world - which can be directly mapped to races. In a way, this is the high tech version of the 1890 Census interviewer instruction that asked about the racial proportion of the respondent's blood. Panelists and members of the audience questioned the scientific basis of the procedure, while treating the suggestion as absurd.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

The Poor In New York City

There are more than a million and a half people in New York City who are living “below the poverty line,” according to official statistics. The poverty line for a family of four was about $18,000 in the year 2000. In a city where many New Yorkers with five times that salary feel that they are just scraping by, some argue that the poverty line should be much higher. But by any measure, poverty in New York City has increased. Almost 300,000 more people in New York City’s population lived below the poverty line in 2000 than in 1990, according to data from the census. In 1990, some 1.38 million New Yorkers -- or 19.3 percent of the population -- were living below the poverty line. By 2000, the number had increased to 1.67 million or, 21.2 percent.

DEFINING POVERTY

Poverty in the United States is defined based upon a formula created in 1963 by Mollie Orshansky. She figured out what income would be needed to purchase the minimum level of food needed for a family. Food was the only area where a clear minimum standard existed. She then multiplied that amount by approximately three, based upon a survey that showed that low-income families spent about one-third of their money on food. Though it has been slightly revised since then, the only real changes have been adjustments for inflation. The thresholds are the same throughout the United States, so those deemed to be “officially” poor in Peoria have the same income as the poor in New York City without regard to different living costs.

A series of other approaches to poverty lines have been proposed,each of these measures giving slightly different results, but no consensus has been reached on what should be the standard gauge.

WHO IS MORE LIKELY TO BE POOR?

Families headed by women with children under 18 are more than twice as likely to be poor (44 percent) as are all families (18.5 percent). Support for elderly through social security has massively reduced the poverty of the older Americans, while poverty among children has increased over the last 30 years: 17.8 percent of New Yorkers over the age of 65 live in poverty, but almost one-third of all children do so.

Many people who are poor at one time do not stay in poverty very long. Indeed, for most people poverty, like unemployment, is episodic. For instance, a student graduates from college and does not immediately find a job. Before finding one he or she might live in poverty. One person loses a job and needs time to find another. During that period that person may have little or no income and might be living in poverty. In such cases, however, official poverty is likely to be short lived. Studies have shown that household dissolution (caused by divorce, death, abandonment, etc.) is the number one cause of poverty, especially for women and children. Job loss is the second major cause of poverty.

When people talk about poverty as a problem usually they focus on the “persistent poor,” those who were born poor and remain poor. Indeed, social scientists (such as several at the Urban Institute) have identified a series of characteristics in the areas where the "persistent poor" are likely to live. These factors include:

- high rates of welfare dependency

- high school dropouts

- female-headed households

- and male joblessness.

Such factors contribute to high levels of urban crime, drug sales, and other urban ills, including graffiti, litter and a lack of neighborhood social control. Abandoned cars, check cashing establishments, advertisements for 40-ounce malt liquor adorn such neighborhoods. Often there are public housing project and high concentrations of minority members.

WHERE ARE THE POOR?

Since many poor are not poor for very long, the levels of segregation among poor residents are not that great. Nonetheless, New York City has two areas of concentrated poverty, as shown in the accompanying map. The first is the broad expanse of Northern Manhattan, including Harlem up into the Bronx. This area contains many African Americans and Latinos (especially Dominicans and Puerto Ricans). The other area is centered on Flatbush and Bedford Stuyvesant, also an area with many African Americans and Latinos. (It is important to point out that many Latinos are not impoverished, and there are many areas in New York City with affluent African Americans, including Southeast Queens and Northeast Bronx). The major “poverty areas” contain neighborhoods that traditionally are seen as containing “ghetto poverty,” where the persistent poor are more likely to make their home.

Areas in the South Bronx and areas in and around Bedford Stuyvesant have contained large concentrations of poverty for decades. Nothing that happened in the 1990s changed that. In fact, the poverty population in New York City grew. The 1990s boom did not trickle down enough to pull such New Yorkers out of poverty. The current economic downturn will only serve to exacerbate the problems of the poor and produce more poor people.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

Eight Million New Yorkers? Don't Count On It

New York City officially had a population of eight million in 2000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. But is this an accurate number? Can we know what the actual number was? The answer is: probably not. To complete a truly accurate census two things must happen: First, one must be able to find all the places in New York City where people live. Second, one must count all the people living in each place (and count them only once), whatever the place is (a single-family home, or a dormitory, a prison, a mental hospital, an old age home, or a convent). Census methods do not readily capture New York City's incredible diversity. Assumptions and procedures that easily count Ozzie and Harriet Nelson and their two children (or even Ozzy and Sharon Osbourne and their two children) living in a single family house in the suburbs, do not work well in much of New York City. With its large number of immigrants, households of roommates and unmarried partners, illegally converted apartments and lofts, and homeless and transient population, New York poses unique challenges for enumeration.

2000 COUNT MORE ACCURATE THAN 1990

To improve the 2000 census, the U.S. Census Bureau asked for help from local authorities. Using a variety of city lists and other methods, the NYC Department of City Planning found households that the census had overlooked. Many were concentrated in areas of high immigration, including Northwest Queens, as well as the Bronx and Brooklyn. According to Joe Salvo, director of the Department of City Planning's population division, the Census Bureau sent forms to at least 160,000 of these households. Since the average household in New York City holds 2.6 persons, that means there were 420,000 persons who otherwise would not have been counted. Such households were probably uncounted in 1990, so a large part of New York City's 680,000 population increase was probably just a result of having a more accurate count.

COUNTING HOUSEHOLDS AND MAKING UP DATA

The census uses a variety of methods to contact households and collect census data. First, they send out a form hoping that it will be mailed back. Nationally, about two-thirds are returned. The fraction is lower in the city and varies greatly by neighborhood. Follow-up methods must be used to count those households that do not return the forms. If a phone number is known, the household is called. For those that do not answer the phone, or for which the phone numbers are unknown, enumerators are sent to the household. When, after repeated attempts, no one is found at home, the enumerator contacts a landlord, a supervisor or even a neighbor to confirm that someone lives in the unit. At that point, the census substitutes for those data. Since they do not know how many people live there, they fill in the household responses by using information from a nearby unit. This is known as the "hot deck" procedure, so named because in the distant past, the data was actually processed using computer cards, and the information was drawn from a "hot deck" of recently processed households. In other words, the census makes up data for households that they cannot reach.

To give one small example of the special difficulties in using current methods to get an accurate count in New York City: A trained Census Bureau enumerator, unable to reach individual households, may look at a building that has been divided into a multi-family dwelling and count the doorbells. In one actual example that was explained to me, one house had three doorbells in one location and what appeared to be two additional doorbells in another location. It would seem obvious that a homeowner or landlord may have created additional apartments. But is the presence of five doorbells proof that there are five households? I posed this question to my students who, for the most part, live in Queens. One woman from Elmhurst lived in a single-family home that had previously been divided into three units. Her house, she said, had four doorbells: an older set of three that no longer worked and one working that she had installed. At the same time, my student also had three mailboxes. Since the basic address list that the U.S. Census Bureau uses is from the U.S. Postal Service, she received three census forms instead of just one.

The census expects one person to fill out the form for each household. Even where data are supplied by one of the occupants of a unit, difficulties may ensue. In certain cases, the degree of cooperation or knowledge about the other residents may leave something to be desired. For understandable reasons, sets of roommates, boarders, illegal immigrants, and live-in household help (who may or may not be documented) may be purposely omitted. When the long form, which is received by about one-sixth of households and includes detailed data on economic standing, occupation, education, housing cost, migration, birth place, and the like, is involved, missing data are even more likely. If characteristics of some individuals are left blank, the census bureau imputes (makes up) those data. In short, the results from every census include made-up data for entire households and for particular characteristics for particular individuals. According to preliminary results such made-up data for NYC increased greatly since 1990.

ANOTHER APPROACH THAT MAY BE MORE ACCURATE

Since 1980, demographers and survey research experts, backed by a report by the National Academy of Sciences, have advocated "statistical sampling" to get at the hard to enumerate households. By this approach, the census bureau would use completed interviews or questionnaires with residents in most households. But for those that proved difficult to reach, they would attempt to interview only a random sample, perhaps one in ten. Results from that sample would be used to estimate the number and characteristics of all of the unreached. These sample interviews would be done by well-trained enumerators, who would use their resources to "get answers" from the hard to reach households.

Though backed by most scientific opinion, the use of statistical sampling in the census is highly controversial. The GOP, perhaps fearing that it would increase the numbers and thus the power of Democratic urban areas, has consistently blocked its use. Scientific procedures to get a more accurate count have repeatedly been rejected by Congress and two Bush administrations. As late as this month, the director of the Census Bureau rejected any sort of adjustment or correction for ongoing programs of population estimates. Instead for Census 2000, Congress allowed the bureau to pour billions of dollars into coverage improvement to help reach more of the hard to count, but still required that every household be enumerated. As we begin to prepare for Census 2010 most demographers think it would make sense to follow the recommendation of a panel of the National Academy of Sciences and use statistical sampling.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

Does Archie Bunker Still Live in Queens?

The image of Queens shared by many Americans, especially those old enough to remember, begins with the character of Archie Bunker, who debuted in All in the Family in January 1971. Through the eyes of those (about half of all people watching TV on Saturday) viewing this seminal TV program, Queens consisted of tightly knit, prejudiced, argumentative families living their lives in relatively well defined neighborhoods.

Such people frowned on marrying outside of ones own group. Archie never got over the fact that his daughter Gloria married a "polack." Other insular attitudes abounded: "Girls were girls and men were men," as the theme song said. Edith, Archie's wife, stayed at home to serve Archie; later she did take a part-time job at a nursing home. Through Archie's bigoted eyes, Jews, who he called "hebes," blacks, Puerto Ricans and others should not be part of his America. Archie and his family continue in reruns to the present day. The show and its successor Archie's Place stayed on the air into the early 1980s, and were reprised for a while in the early 1990s on CBS. Now it lives on in reruns -- one cable channel runs two episodes a day, everyday. All my students are very aware of Archie Bunker.

One year before the launch of All in the Family, the borough of Queens did largely resemble the place Archie and his family lived. The borough was 86 percent white, 13 percent black and about 1 percent Asian. The likelihood that a black family like the Jeffersons would move near Archie's house was near zero. Like Archie, about 80 percent of Queens residents were born in the United States, and only 3.5 percent were not citizens. Only about 3 percent (or less) were Hispanic and only about 1 percent were Asians. Aside from the United States itself, just five countries -- Italy, Germany, Poland, the Soviet Union and Cuba -- supplied more than 1 percent of the population. Almost 90 percent of men and about one half of women 18 to 64 were in the labor force. Only 24 percent of those 15 or older had never married. In short, Archie, a Protestant though he was played by a Catholic (Carroll O'Connor), was living in a Queens populated mostly by native born people who lived in married couple households.

Today, of course, Queens is radically different. It is only 44 percent white. The borough is 20 percent black and 18 percent Asian. Still it remains highly segregated with blacks rarely living in neighborhoods with many whites or Asians. Only 54 percent of the residents were born in the United States, and those from Asia and various Central and South American counties make up about 40 percent of the population. Now only three quarters of the men aged 25 to 64 are in the labor force, while two thirds of similarly aged women work.

Today, the vast majority of Queens residents 15 or older have been or are married. In 2000 less than one-third never had been married. Throughout the United States, of course, the percent of people never marrying has been rising steadily.

Given the radical changes, would Archie still live in Queens? If one does not consider ethnic, racial or foreign-born origin the answer is yes. In 1971, Archie may have been a bigoted and insular native-born white Protestant suspicious of foreigners, blacks and Puerto Ricans. Today, one could find Archies among many of the diverse groups living in the borough and elsewhere. (The fact that Archie struck such a responsive chord throughout the United States may mean that his attitudes expressed those of many in the 1970s and early 1980s.) Though they may come from different parts of the globe, speak different languages and be members of different racial and origin groups, Queens residents mostly live in family households in family neighborhoods. They are intently focused on their own family, their own neighborhood and their own group. They probably are as much against intermarriage as was Archie. Many immigrants are very conservative politically. Many have hostile attitudes toward African Americans, according to recent exit polls and other surveys.

Indeed, the immigrants have become Americanized. Many have a foot in two societies, the United States and the one from which they immigrated. Queens was a borough of married families in 1970, and it is still a borough of married families today. Of course, more of the Ediths of today work. But today's Archies, though they come from many different origins, remain family centered and ethnocentric.

The Queens Library recently mounted an exhibit, much of which is now on-line, entitled From Burgh to Borough: Queens Enters the 20th Century, which focuses on the development of Queens' neighborhoods. Archie Bunker lived in one of these neighborhoods (there is dispute as to which one); his successors live in these same neighborhoods. Indeed, such neighborhoods look very much the same today, as they did when Archie lived here. It is just the people's background that has changed.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

Is There Still A New York Metropolis?

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently introduced the idea of imposing a large tax on commuters, one of his advisors made an argument for the tax that people in New York City have been making for a long time. Without New York City, he said, the rest of New York would be Appalachia. Is this really true? Do suburbanites see the city as the center? Does the rest of the region depend on New York City? Is there still a New York Metropolis?

A century ago when Jacob Riis wrote How the Other Half Lives, both halves lived in the city. This began to change with the growth of the suburbs. By 1940, the United States Census Bureau began considering New York City to be part of a "Metropolitan District." Over the years, the New York metropolitan area has been defined more and more broadly, as the map below indicates.

The New York metropolitan area has been defined more and more broadly over time.

Click image for larger version.

The Regional Plan Association, has believed for decades that, whatever the arbitrary political boundaries of New York City, it is in reality a region encompassing 31 counties. Many people say the metropolitan area extends 75 miles from Times Square.

The census bureau began referring to the New York region in 1940 but its definition kept changing. (See map above.) By 1995 the Consolidated Metropolitan Statistical Area, or CMSA, for New York City consisted of much of Litchfield, Middlesex, Fairfield and New Haven counties in Connecticut, Pike County, Pennsylvania, a swath of counties in New Jersey, as well as near and far suburban New York counties. For this column, this area is divided into three groups of counties, the City, the seven counties that border any of the five boroughs of New York City the "near suburbs," and the rest of the region, "periphery."

There are many trends that have shaped the New York Metropolis since 1940:

- the large movement of population to the suburbs;

- continuing migration of African Americans from the South, at least until about 20 years ago;

- a dip and then increase in the number of migrants from abroad;

- large scale migration of population out of the area to other parts of the United States.

Since 1940 the suburbs rather than the city have grown the most, as the chart (below right) makes plain. In 1940, the New York metropolitan area had about 13.5 million people, of whom 7.5 million, or 55 percent, lived in the city. In 1940, eight years before E.B. White wrote "Here is New York," New York still meant New York City. (Yet White himself was born in Mount Vernon, and by then was living in Maine.)

Today, the "metropolis" contains about 21.5 million people. The city now constitutes only 37 percent of the region. While the city is about seven percent larger than it was in 1940, the near suburbs grew 58 percent, and the periphery grew 211 percent!

Since 1940 the suburbs rather than the city have grown the most.

Click image for larger version.

It was not just people who shifted to the suburbs, it was their wealth. In 1950, the median family income in New York City was a little higher than that of the periphery and somewhat lower than that of the near counties. By 2000, the median family income had increased by 73 percent in the city, but had jumped 145 percent in the near suburbs and 193 percent in the periphery. In short, the suburbs reaped large gains in both population and income. In 1940 those living in the city were about on a par with their suburban compatriots. By 2000 they had fallen far behind.

In the midst of the yearly squabble over tax revenue for New York City, several years ago Mayor Rudy Giuliani opined that New York probably had a higher proportion of workers commuting into New York City -- and earning higher incomes -- than any other city. This is simply not true. When the ten largest metropolitan areas are considered, in 1990 New York City actually had the lowest proportion of its labor force commuting from the suburbs. Said another way, New York City had the highest proportion of its labor force living in the city, about 80 percent. This was 12 percent higher than the next highest, Philadelphia, and 18 percent higher than Los Angeles. The fifth of the city labor force who commuted into New York from outside the five boroughs earned more, were more highly educated, and were much less likely to be members of minority groups.

The commuter tax and other recent policy conflicts in New York point up some of the implications of these developments. The repeal of the commuter tax for New York State residents who commute to New York City largely benefited highly paid, well-educated suburbanites at the expense of New York City residents. Its reimposition would affect them the most. George George Pataki is the first New York governor who does not have a strong connection to the city. A lifelong Westchester resident, he served as mayor of Peekskill and as a member of the State Assembly. With the votes and power now outside of the city, things like the repeal of the commuter tax happen with ease. A telling example may have been the governor’s $ 54 billion proposed package to deal with the World Trade Center attack. Incredibly, it included much economic and transportation aid for upstate New York. These trends and the policies shaping and exacerbating them do not bode well for the overall health of the city. The affluent now build a suburban society away from New York City, with no legal requirements to help those in the five boroughs. Mayor Bloomberg, a consummate salesman, has his work cut out for him.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

Can The US Live Without Race?

After nearly 10 years of controversy, the federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) determined before Census 2000 that each United States resident must be classified as a member of one or more of the following racial groups: White; Black, African-American or Negro; American Indian or Aleutian Islander; Asian; or Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. For the census questionnaire if you were unsure which group you belong to you could answer "Other." However, your response eventually will be placed in one of the official categories, at least for statistical purposes.

At Queens College, where I teach, many of my immigrant students are indignant about such an arbitrary racial classification. The Greek students, who claim that the Greek language does not have a simple translation for race, consider themselves Greek, not white. Most Haitian and some Jamaican students do not consider themselves "Black, African American or Negro." Students from various countries in East, Southeast and South Asia do not understand how they are all from one specific racial group: "Asian." The much ballyhooed multiple race answers to Census 2000 amounted to very little in most locales, including New York City, as I wrote in a previous column. Despite the genetic reality, made plain by the controversy surrounding whether Jefferson fathered Sally Hemmings' children and books such as Slaves in the Family, about 99 percent marked only one racial box on Census 2000.

The Human Genome Project, the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, and the American Anthropological Association all cast doubt on the utility of the concept of "race." Indeed, the anthropologists' statement puts race into its historical context: "As they were constructing US society, leaders among European-Americans fabricated the cultural/behavioral characteristics associated with each 'race,' linking superior traits with Europeans and negative and inferior ones to blacks and Indians. Numerous arbitrary and fictitious beliefs about the different peoples were institutionalized and deeply embedded in American thought. Early in the 19th century the growing fields of science began to reflect the public consciousness about human differences. Differences among the 'racial' categories were projected to their greatest extreme when the argument was posed that Africans, Indians, and Europeans were separate species, with Africans the least human and closer taxonomically to apes."

As for collecting race data, the anthropologists indicate that they would be more comfortable with using ethnicity for origin data, though they acknowledge that it will take a long time to change to such a formulation. In the early 20th Century, there was little doubt about race. In 1925, when the census was reporting on the population in Detroit, it bluntly characterized the population as White, Black, Red and Yellow. The Yellow were subdivided into Chinese and Japanese. Such classifications have not b een completely retired. A 2002 voter list from Allegheny County in Pennsylvania had the same racial groups: R for Red, W for White, Y for Yellow, and B for Black.

Recent work emanating from psychology, most particularly Hernstein and Murray's The Bell Curve and J. Philippe Rushton's Race, Evolution, and Behavior revisit this early characterization. Rushton argues that races differ in intelligence and reproductive behavior, and that those differences have evolutionary origins. "Orientals" have the largest brains and highest cognitive abilities, "Negroids" have the smallest brains and strongest drive to reproduce, and "Caucasoids" are somewhere in between. He supports his claims with comparisons of IQ scores, sexual behaviors, and even genital size.

Opposition to the use of the concept of race for collecting data about origin continues to build among many groups of professional social scientists based upon its mistaken biological basis. A self-report (on the census or other surveys) or a report by an official (for schools, hospitals or other organizations) seems an odd way to collect data about supposed biological origin. The confusion of my immigrant students, the sub-classifications of Asian race and Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander race by country of origin, and the sub-classification of American Indian or Alaska Native race by enrolled or principal tribe, show that race has become very difficult to classify and interpret. The census short form's official designation of Hispanic or Latino origin collected by a different question also expects a sub-classification by country of origin, The Census, of course, collects other data on origin on the long-form, including "ancestry or ethnic origin" and actual place of birth.

Ward Connerly, whose initiative forced the end of affirmative action at the University of California, now wants to end the collection of racial information in California by the government with exceptions for medical, legal and employment and housing enforcement. At the same time, the American Sociological Association, a group of which I am a member, recently issued a "Statement on Race." It not only calls for the continuing collection of information on origin, but the continuing use of the term race, "so that scholars can document and analyze how race--as a changing social construct--shapes social ranking, access to resources, and life experiences." No where in the statement is there any recognition that "race" began life as a biological concept to be used for invidious distinction among groups. Nor do they seem to recognize that it has become a more and more complex concept to measure in the United States, while it is now conditioned by many other factors related to origin. Native-born whites may be different than most immigrant whites. The differences and similarities between immigrant and native-born blacks could prove to be very important as "influences on social ranking, access to resources, and life experiences." Many immigrant blacks, for instance, assume that their fortunes in the United States will be much different and much better than those of native-born Blacks. Understanding whether this is true would show whether racial origin or classification trumped other factors.

Plainly, much of the interest in the new census data revolves around the fate of various social groups, including those traditionally considered race groups, as well as immigrants from various locales around the globe, the Hispanic groups, the disabled, the highly educated, and others. Given the growing diversity in the United States, it seems increasingly important to understand the widely varying origin of United States residents. For this very reason, it may be time to retire the concept of race, and combine it with other information on origin, including Hispanic or Latino origin and ancestry. Reynolds Farley, a sociologist at the University of Michigan and perhaps the premier demographer following the United States Census data most particularly concerning the state of the black population, proposed a single census question to measure race, Spanish-origin and ancestry. Such an approach recognizes that answers to race, as with those other questions, really are self-identifications.

So far apparently, the collection of data on race is too controversial to become simply part of a question on origin and ethnicity, even if the responses to such a question might be more accurate than answers to the current questions. Such an approach would in no way undercut the use of such categories for affirmative action, to stop invidious group profiling, or to track the impact of racial identification or other origin on disease. Instead, it would make it possible to respond to the actual diversity that now exists in the United States. Until then, those interpreting the Census 2000 results concerning race should realize that race as a biological concept no longer exists, but rather it is simply self-identified origin, as is Hispanic or Latino, or Italian or Irish.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981. Since 1993 he has done demographic analyses and consulted for the New York Times. He has provided expert testimony in districting and redistricting, housing discrimination, and numerous other civil rights cases in the metropolitan area and elsewhere. The opinions expressed in Topics are his alone.

New York's Declining Ethnics

New York City's population may be made up more and more of the foreign-born, but, according to the latest U.S. Census, there are fewer ethnic New Yorkers, and "white ethnics" have declined by almost half over the past two decades. This phenomenon, though, may have less to do with demographic shifts and more to do with changing attitudes

Part of the uncertainty is that the census bureau has changed the way it has defined and counted ethnicity over the years, just as it has done with race. Starting in 1850, the census asked Americans where their parents were born, and then fit them into one of three categories:

1. "Native Born of Native Stock" -- born in the United States and parents born in the United States

2. "Native Born of Foreign Stock" -- born in the United States, but parents (at least one) born abroad, or

3. "Foreign Born of Foreign Stock."

Thus, if a New Yorker's grandparents had immigrated from Mesopotamia, that New Yorker was put in the same category (native born of native stock) as a descendant of a voyager on the Mayflower. A third-generation American was officially considered to be American, period.

Of course what's official and what's for real are not always (seldom?) the same thing, especially in New York, the ethnic capital of the nation, if not the world.

After lobbying by various ethnic organizations, the census bureau changed its classifications. Starting with the 1980 census, it asked for "ancestry or ethnic origin." This question, not as precise as "where were your parents born?", really requires a kind of subjective self-identification. By the time of the 1990 census, the change in the official demographics of the United States based on this question was summed up in the wry title of an article in the American Sociological Review: "How 4.5 Million Irish Immigrants Became 40 Million Irish Americans."

But ten years later, things seem vastly different. In New York City, the percentage of those claiming Irish ancestry has dropped from 9.2 percent in 1980 to 7.3 percent in 1990 to 5.3 percent in 2000. For the other "white ethnic" groups one finds similar declines:

- Italian -- 14.2 percent in 1980, 11.5 percent in 1990, 8.7 percent in 2000;

- German -- 6.4 percent in 1980, 5.4 percent in 1990, and 3.2 percent in 2000;

- Polish -- 4.8 percent in 1980, 4.1 percent in 1990, and 2.7 percent in 2000.

- English -- 4.3 percent in 1980, 2.4 percent in 1990, 1.6 percent in 2000.

The census allows for up to two ancestries, so a sizable fraction (roughly about 1/6th) of these individuals reported another ancestry as well. All together, the proportion of people reporting themselves as a member of one of these white ethnic groups in New York City declined from about 39 percent in 1980 to slightly over 20 percent by 2000.

There is no question that the population has changed in the city. But how much of the decline in, say, Italian-Americans in New York is simply because fewer New Yorkers are now calling themselves Italian-American? In 1990, 157,000 New Yorkers (about 2.1 percent of the population) identified their ancestry or ethnic origin simply as "American" or "United States." In 2000, that number had grown to 238,000 (or about 3 percent.) Were these extra "Americans" newly arrived New Yorkers, or were some of them long-time New Yorkers who used to call themselves Irish-American or Polish-American?

These self-identified "un-hyphenated" Americans are clearly a growing trend. At the same time, though, other "ethnic" groups are on the rise in New York, even officially. Those New Yorkers claiming Arab ancestry now number about 71,000 (in 1990, there were 52,000.) The number of New Yorkers with African ancestry has more than doubled, from 54,000 in 1990 to 122,000 in 2000. (The largest group of Africans are the 18,000 Nigerian-Americans.) About 550,000 New Yorkers claim non-Hispanic West Indian ancestry, which is up from 392,000 in 1990. Of these about 213,000 are Jamaican-American.

But, the question: In the censuses of the future, will their children keep the hyphen? Will their grandchildren?

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.