The End of 'White Flight?'

Year after year, decade after decade, New York City was home to a rapidly changing and increasingly diverse population. Whites were seen as fleeing the five boroughs, while blacks, Hispanics and immigrants replaced them. At the same time, the median incomeof city family was barely growing and often declining. Now according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s huge 2006 American Community Survey, as well as the census’ own estimates, most of these trends seem to have ended. There even are signs that they may have been reversed:

Some highlights:

* The African American population is declining. The proportion of non-Hispanic African Americans dropped from 24.5 percent of the city’s population in 2000 to 23.7 percent in 2006. The number declined from 1,962,154 to 1,947,328.

* Hispanic growth has almost ceased. The proportion of Hispanics in New York barely grew from 27.0 percent in 2000 to 27.6 percent in 2006. In the last year for which estimates are available, the Hispanic population in the entire city increased by only 911people.

* The non-Hispanic white population is no longer declining. The proportion of Non-Hispanic whites declined from 51.9 percent of the population in 1980 to 35.0 percent in 2000 -- a drop of about 17 percent. From 2000 to 2006, the proportion dropped by only 0.2 percent.

* The increase in the number of foreign-born New Yorkers has slowed from a stream to a trickle. After rising from 18.2 percent of the population in 1970 to 35.9 percent in 2000, the percent of foreign-born grew only an additional 1.1 percent from 2000 to 2006.

. The Asian population continues to grow at a rapid pace. The proportion of Asians in New York City grew from about 19.6 percent to 23.3 percent and increased by over 350,000 in six years. This is one trend that continues.

* There remains little growth in income. In constant 2006 dollars, the median income of a New York City family was $53,105 in 1970. Since then, it has gone up and down a bit and in 2006 was $51,830. During the past 36 years, there has very little net change in median family income in New York City.

Reversing the Trends

The reversal of many long-standing demographics trend is particularly pronounced in Manhattan, as Table 1 shows. The proportion of foreign born, Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks all declined in the borough, while the percentage of non-Hispanic whites increased. But Manhattan differed from the rest of the city when it came to income. Rather than remaining stagnant, median family income there soared from about $61,000 in 2000 to $71,000 six years later.

The trends embody a shift in attitudes about the city. In the 1970s and 1980s, many middle-class people and whites left New York City, and even Manhattan was considered a “difficult” place to live. Now New York City -– particularly Manhattan -- is becoming a sought after venue, at least for those who can afford it.

For instance, in 2000 the median house value for all owner-occupied housing in Manhattan was $423,000. By 2006 it had risen to $787,000, an increase of 86 percent. In the city as a whole, the median value of homes occupied by their owners climbed from $259,000 in 2000 to $496,000 in 2006, an increase of 91 percent.

The increases in income and the declines in the percentage of foreign-born, black and Hispanic New Yorkers, particularly in Manhattan, seem to indicate that the people who have come to the city recently are more affluent than those who left or decided not to not come at all. More analysis will elucidate this.

The real question is whether the trends that shaped New York City for much of the latter half of the 20th century historic will reemerge, whether the trends will substantially reverse or whether the city will experience little change. In Manhattan the trends already have reversed, with the borough becoming increasingly white and affluent. The rest of the city could follow. This already seems to be the case in some “Manhattanesque” neighborhoods, such as Brooklyn Heights, Williamsburg and Astoria.

On the other hand, the recent changes may simply be the result of the recent boom in finance and real estate. If that boom ends, then the demographic change of the first years of the 21st century could simply represent a blip in the continued long-term trends. Or some other trend or trends may emerge.

Only the future will reveal the answer. But one thing is certain; the demographic and population changes in New York City will likely be both unexpected and fascinating.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Feeling the Effects of a Housing Bust

The soaring values of apartments and houses in the city gave many New Yorkers a major real estate obsession during the first part of this decade. After residential real estate prices took over a decade to climb back to their levels of 1987 (the beginning of the last real estate crash), property values began to soar in 2000 and continued their heady ascent until recently. Now, of course, real estate price increases are yesterday's news as buyers dry up, inventories of unsold properties mount, sub-prime mortgages readjust and foreclosures increase.

This fall in the housing market will have many effects in New York City. But some New Yorkers, particularly lower-income people, blacks and Hispanics, will feel more pain than others.

The End of the Boom

The 2000 census reported that the median property value was $258,966 (in 2006 dollars) for all owner occupied housing in New York City. By 2006 the value had risen to $496,400 an increase of $237,434 or 91.7 percent. By 2005, though, much of the escalation had run its course, and from 2005to 2006, the median increased by a mere $32,916 or 7.1 percent.

Meanwhile, according to U.S. Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke, losses from sub-prime mortgages (higher interest loans taken out by people who cannot qualify for conventional mortgages) have far exceeded "even the most pessimistic estimates."

These will probably mean pain for the New York City. As residential real estate prices decline, tax revenues will fall. Some residents will lose their homes, and others will be strained near the breaking point to pay their mortgages or will take advantage of various state and federal loan "stretch-out" or "work-out" provisions that have yet to be enacted.

The rise in housing prices was fueled by new mortgage products that allowed people to buy homes with no down payment upfront. Many of these loans did not require income verification. Then the mortgages were packaged and sold as securities to financial institutions. The failure of many people to repay their loans set off the recent credit crunch.

The Big Losers

What does the housing bubble and likely bust mean for New York City. Which residents are most affected?

For one, the credit crunch and its reverberations on Wall Street could ultimately affect the bonuses of Wall Street traders and brokers.

The effects, though, go far beyond that. New York City, despite many claims to the contrary, actively participated in the housing bubble of 2000 to 2006. Data from the Census Bureau’s 2006 American Community Survey, released on September 12, 2007 provides a view of the many ways that New Yorkers are vulnerable to any meltdown in real estate value and accompanying credit crisis in the mortgage industry.

In New York City in 2006, almost half of all those with mortgages spent more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs, including mortgage, taxes, insurance and utilities. More than one quarter paid over 50 percent. Of those who purchased homes with a mortgage in the last two years, half were paying at least 32 percent of their income for housing costs, and one quarter were paying 55 percent or more.

For Hispanics, African-Americans and Asians, the figures were even higher. Half of Hispanics paid at least 37 percent and one quarter spent 81 percent or more. Among non-Hispanic African Americans the figures were 44 percent and 71 percent, and for non-Hispanic Asians the figures were 38 and 63 percent. On the other hand, for non-Hispanic whites half were paying at least 24 percent and one quarter 40 percent or more. Plainly, non-Hispanic whites are not straining their budgets to the same extents as Hispanics, blacks and Asians to buy a piece of the American dream.

The high home ownership costs often reflect the introductory terms of loans that make them "affordable," for the first few years. When such loans readjust, the costs increase.

The picture looks particularly difficult for people purchased homes in 2005 and 2006. They made their purchase at what appears to be the top of this particular housing bubble. They may be in for a serious financial loss, as mortgages readjust while the underlying value of their properties decline. Those who have been in their houses for years generally do not pay as much of their income for housing costs, and though they may lose paper value, they will be able to continue to live in their home, as long as they did not refinance it using a new mortgage product.

Those most at risk of losing their homes because of high housing costs are more than proportionally minority, less educated, either very young or very old, and most especially with much lower incomes than those living in affordable situations. (See Table for the results.) The median income of those paying less than 30 percent of their income on housing is $120,900. For those paying between 30 and 50 percent of their income, though, the median is $74,390, and for those paying over 50 percent the median income is $39,900.

Not surprisingly, the areas with the highest proportion of income going for home ownership costs are in Queens (especially Jackson Heights, East Elmhurst and Corona), Brooklyn (notably Borough Park, Greenpoint/Williamsburg, Bushwick, East New York, Ridgewood, Cypress Hill, Highland Park and New Lots) or the Bronx (in particular Morris Heights, University Heights and Fordham.) Manhattan homeowners do not appear to be spending more than they can afford to anywhere the extent of those in the other boroughs. (See map.)

In short, the housing bubble, fueled in part by sub-prime mortgages affects New Yorkers in different ways. However. even many New Yorker who do not work on Wall Street or have a sub-prime mortgage may feel the pinch. As residential property values decline and tax revenues fall, all New Yorkers who depend on city services or who work for the city or state will face stringencies. Thought the housing bubble may have been exciting for many, particularly those selling mortgages or moving into houses they probably could not afford, its hangover is likely to affect everyone.

(Note on sources: This analysis was largely based upon the Public Use Micro Data Sample, or PUMS, from the 2006 American Community Survey, while some data are drawn from tabulated data from that survey and the 2005 survey and the 2000 Census. All responses are based upon self-reports of income, house value, race, education, etc. The data are subject to sample variation.)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

Women of New York City

New York women are different, especially those who live in Manhattan. They are much more likely to be single, earn more money, and have more education than women living in the rest of the United States. And while the same percent of New York women are working as women elsewhere in the country, the jobs they are doing are much different. These are some of the significant results from an analysis of data from the 2005 Census.

About 45 percent of New York City women ages 25 to 64 ever married. In Manhattan, it’s just 37 percent. Elsewhere in the country, however, some 61 percent of women live with a spouse. Manhattan is one of the counties with the highest percent of those living on their own in the United States. Table 1 shows the proportion living with a spouse for men and women in two age ranges. As is plain from that table, those living in Manhattan and the outer boroughs follow a very different pattern than those in the rest of the United States.

Among those 25 to 64, while 63 percent of all Manhattan women have at least four years of college, slightly less than 30 percent of outer borough and other women in the United States have that level of educational achievement. When it comes to holding a job, 69 percent of Manhattan women, 60 percent of outer borough women, and 67 percent of women living elsewhere were working. When one looks at the type of jobs held by women in Manhattan compared to the rest of the United States the differences are striking. Though relatively small proportions, Manhattan women are much more likely to be actresses (about 14 times), authors(about 9 times); lawyers and judges (about 9 times), as well as dancers, photographers, stock and bond salesmen, psychologists, editors and reporters, architects, artists, economists, designers, physicians and surgeons and a range of other professions than in the rest of the United States.

Considering earnings, Table 2 present some information for women working full time in various occupations. In most occupations, men out-earn women. But this is especially true in Manhattan for law, medicine and stock and bonds salesmen. In each of these areas men out-earn women by more than two to one. Even the very high levels of education for Manhattan women do not wipe out this disparity. But female secretaries, designers and authors in Manhattan do earn more than men in those fields.

Women with a spouse in Manhattan have much higher household income, but have lower earnings than those who do not have a spouse. For men, however, those with a spouse have much higher earnings and household income than those without. The pattern is much less marked for those living in the outer boroughs or in the rest of the United States. This suggests that some women in Manhattan though working do not contribute to the family or household income as much proportionately as do their male spouse. This is directly related to the occupational income gaps between men and women in Manhattan. Remember, the very high income professions, such as law and financestill are predominantly male, at least at the highest income levels, even if more women are in them in Manhattan than any where else.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

Many Issues, Many Nationalities in Central Brooklyn

Candidates and their Web sites

The 40th City Council district sits at the geographic center of Brooklyn. It is an area of immigrants. People from every Caribbean island, along with residents of other ethnic groups, populate the district, which includes part of Flatbush and East Flatbush.

The ten candidates running in the special election say they seek to represent everyone in this diverse community. But given the likely low turnout, many will have to motivate their base – and often that core support consists of people who share their national roots. Eight of the ten candidates are black and have some connection to the Caribbean or Central America.

In 1991, the 40th elected the first Jamaican to City Council, Una Clarke. And the Clarkes still wield influence. Una Clarke served on the council until forced to leave office by term limits in 2001. Her daughter, Yvette Clarke succeeded her, staying on City Council until she won election to the U.S. Congress last November. The special election is to fill her seat.

In this race, the Clarkes have endorsed Mathieu Eugene, the one Haitian in the race. That support gave Eugene a boost in his quest to become the first Haitian on the City Council. But the large field leads most to believe this contest is very much up for grabs.

THE ISSUES

The candidates list an array of issues as being of major concern to residents of the 40th district. And while the candidates differ in their emphasis and offer varying solutions, the campaign has been marked by few, if any, clashes over policy.

Affordable Housing

Most of the candidates believe that developers should set aside a certain percentage of apartments – about 30 percent, several said -- for affordable housing. Some also questioned the definition of affordable housing, saying that many homes the city considers “affordable” are too expensive for residents of the 40th district. Wellington Sharpe said people in each community should determine what affordable housing means for their neighborhood.

Jesse Hamilton would survey the area to determine places where new housing could be built, while Mathieu Eugene would do an assessment of buildings to determine which ones are vacant “and figure out how we can help those owners and get affordable housing” in now empty properties. Similarly Joel Toney sees opportunity for development on commercial strips in the district where many building have just one story. He would encourage additional floors for housing.

Zenoba McNally, who has made housing the focus of her campaign and describes herself as “passionate” about the issue, said that “instead of building homeless shelters, the answer is more affordable housing.”

To get that housing built, “we have to talk about holding developers’ feet to the fire,” Jennifer James said. She cautioned that programs to encourage more economical housing have to be carefully crafted. “Once you have a loophole, people will take advantage of it,” she said.

While residents in the less affluent parts of the district want more development, those at the district’s western edge, such as in the Ditmas Park neighborhood, worry about too much development. Harry Schiffman, who lives in one of those areas, said he has been working to get landmark status for the neighborhood to protect the existing housing.

“You have to find a happy medium,” said Wellington Sharpe. “I would not be ready to build a 15-story house on every block but you cannot say no more building because people are coming into the community daily.”

Education

Most of the candidates expressed concern about the quality of schools in the area, particularly the size of classes. Speaking with people in the community, Mohammad Razvi said he found residents are “really upset about the size of classrooms. They really have to focus on downsizing.” As a member of the council, Leithland "Rickie" Tulloch said he would push for more funding to hire additional teachers and reduce class size. He would also like to see the Bloomberg administration abandon its push for publicly financed but privately run charter schools. “We need to have all of our funding invested in the public school system,” he said. And Zenobia McNally said other activities, such as art and music, could serve to involve students who are not as interested in the traditional academic subject.

Many say that the changes in city’s education system over the last several years have not solved the problems facing the area’s schools.

The new programs have not helped student learn how to think critically, said Harry Schiffman, adding, “We need to have kids in our schools understand how to operate a business.”

Jesse Hamilton, a former chair of a community school board, said that since the mayor assumed control of the public school system the “City Council has been cut out” and the administration has been trying “to use a corporate formula for public school system, which is really not working.” That structure has made the school system less personal than it once was, he said, discouraging many parents from becoming more involved in their children’s education.

Those obstacles are particularly daunting for immigrants said Mathieu Eugene. “There is a language barrier and a culture barrier,” he said, and “the parents are working very hard. They are low-income people.”

Jennifer James also has qualms about recent changes in education, particularly breaking large failing high schools into smaller schools. “It theoretically sounds great,” she said, but James believes this approach adds more administration without improving teaching. “We have to stop thinking about administrative answers,” she said and instead focus on teachers.

Karlene Gordon agrees. “It troubles me that the solution to failing schools is to shut them down,” she said at a recent candidates forum. “I don’t think that’s the answer. The answer is to hold our leaders accountable.” Closing schools, she added, “sends a horrible message to the community, a horrible message to the students.”

Jobs

“A lot of people are looking for work,” said Jesse Hamilton. In some parts of the city, says Mathieu Eugene, as many as 60 percent of black men do not have jobs. Better training could help address this, he said, as would assistance for small business. Although such businesses are “the backbone of the community,” Eugene said, it is difficult for them to get loans and other help. “I would like to make it a little easier,” he said.

Jennifer James thinks the city should expand vocational programs within the public school system so young people who do not go to college can “continue to be productive members of society.” Wellington Sharpe would like to establish a training institute to teach marketable skills to young men and women not planning to attend college.

In a twist on that idea, Zenobia McNally proposes that government or private groups buy the long vacant Loew’s King Theater and let teenagers work with construction unions to renovate the building and learn a skill in the process.

Developers should provide jobs to Brooklyn resident, said Mathieu Eugene. If elected, he said, he would sit down with developers and tell them “I want you to be there but I want you to provide jobs for the community” – jobs with fair wages.

Health Care

Residents in the 40th district have high rates of HIV and AIDS, diabetes, hypertension and childhood obesity, according to Jennifer James. But many residents, particularly immigrants, do not take advantage of existing programs that could help them confront these and other health problems.

Mathieu Eugene, a physician, said offering more information on health care is key and notes that he has helped provide free screening for colon rectal cancers and spearheaded health fairs in the district. But Eugene concedes not all problems can be addressed at the community level and said he would do whatever he could to push for universal health coverage. Many of the small businesses in the district do not offer health insurance to their employees, Jennifer James said. She suggested City Council try to provide tax credits or other incentives to make it easier for them to provide such coverage for their employees.

Immigrant Issues

The many immigrants living in the 40th district often do not know about services available to them. Most of the candidates said they would seek to provide translation services and more public information to address that. Wellington Sharpe said immigrants often spend lots of money going to lawyers for routine matters. This is a burden he would like to ease by helping to establish a nonprofit agency that could offer some of those services. “When you are an immigrant and 50 percent of your income goes to rent, the small issues loom large,“ he said.

EXPERIENCE AND ENDORSEMENTS

Along with issues, the candidates stress their work in the community as evidence that they – and not one of the nine others – should be elected. Mohammad Razvi and Mathieu Eugene say they are already doing the kind of work they would do as council members. Both run community nonprofit groups that do extensive work with young people in the area. Hamilton cites his experience on the school board, while Ron Schiffman touts his work in housing issues. Joel Toney, Zenobia McNally, Leithland Tulloch and Wellington Sharpe all point to their time on community boards.

The candidates speak of their deep and long ties to the 40th district, And many point to their endorsements. Yvette Clarke and Una Clarke’s support for Mathieu Eugene garnered the most attention. The physician has not raised a lot of money and had not won the backing of a number of Haitian civil leaders. The man who did – Ferdinand Zizi – withdrew because of problems with his nominating petition.

On the other hand, Jennifer Jones had worked in Yvette Clarke’s congressional campaign. Saying she still has a good relationship with Yvette Clarke, Jennifer James said she did not know why the new member of Congress made the decision to endorse Mathieu Eugene. For his part, Eugene said his endorsement from the Clarkes and others indicates that his support goes beyond the Haitian community, although he added, “something I bring to the table is the participation of the Haitian community.”

The ethnic issue looms large here – at least in blog entries and media accounts. A recent New York Times article saw the race through that perspective. The contest, wrote Jonathan Hicks, “has become a test of ethnic primacy among the fervently political West Indian groups that are prevalent in the district. And just as Irish and later Jewish and Italian politicians clawed their way to political power by first capturing local offices in previous generations, the Caribbean groups are viewing this contest as a vehicle for showing their growing political clout.”

Wellington Sharpe said that people should vote for the best qualified candidate but then joked that, if people vote along ethnic lines he would come out ahead as Jamaicans represent the largest group in the district.

Most candidates say their support extends beyond an ethnic base. After September 11, 2001, Mohammad Razvi said, “I was afraid there was going to be a backlash against my community and other communities.” In response, he started the Council of Pakistani Organizations. But as a wider spectrum of people in the community began availing themselves of the group’s service, Razvi said the P in COPO came to stand for People, indicating, Razvi said, that he has a record of working with all parts of the district.

The Kings County Democratic organization has not officially backed a candidate, although Wellington Sharpe seems to have garnered the support of the most politicians, including City Councilmembers Kendall Stewart, Lew Fidler and Dominic Recchia and State Senator John Sampson. James cites the backing the activist group ACORN, Razvi has the endorsement of the District 9 union, while another Hamilton said that District 37, of which he is a longtime member, backs him.

THE OUTLOOK

Do not expect to see any television ads in this race but money still matters as candidates run phone banks and send out mailings. Mohammad Razvi leads the money race, according to February 1 filings, with $41,379. Jennifer James came in second with $27,413. Mathieu Eugene raised a mere $3,445 according to http://blogs.nydailynews.com/dailypolitics/archives/2007/02/council_race_ro.php The Daily Politics, although he has borrowed $35,000. Wellington Sharpe boosted his campaign coffers by lending himself $25,000.

The sheer number of candidates makes the race hard to call. To Mohammad Razvi, the crowded field is a sign of vitality. “I think that’s great,” he said. “It makes it more exciting. It wakes up people to participate. If there were just two candidates, there wouldn’t be that buzz.”

But others worry that so many contenders could enable someone with a scant support to capture the seat. Jesse Hamilton said it would be better if the law provided for a runoff rather than awarding the seat to the top vote getter, regardless of how narrow his or her margin. Reviewing the numbers, Hamilton figures that, if the weather is cold, turnout could be as low as 3,000 voters. That means, he said, that someone could win the elections with just 400 votes.

The Candidates:

Mathieu Eugene: A physician and native of Haiti, Eugene runs a non-profit organization that helps young people in the community.

Karlene Gordon: A teacher she has been involved in efforts to fight domestic violence.

Jesse Hamilton: Hamilton, who grew up in a housing project in the South Bronx is an attorney who has worked for the city Department of Finance for more than 20 years. He is a Democratic district leader, served as president of his community school boards and is active with a number of civic and political groups.

Jennifer James: A professional political fundraiser, James most recently served as finance director for Yvette Clarke’s successful campaign for U.S. Congress. She has also worked in campaign for Carl McCall, Kevin Parker and Fernando Ferrer. She was a founding member of the Council of Urban Professionals, which works to encourage political involvement and develop political leadership in black and Latino communities, and a lifelong a member of Lenox Road Baptist Church.

Zenobia McNally: A marketing executive who owns her own company, McNally ran unsuccessfully against Yvette Clarke for this City Council seat in 2005. She has been a member of the Community Board 17

Mohammad Razvi: Originally a business owner, Razvi now serves as executive director of the Council of Peoples Organizations, a community group based on Coney Island Avenue that he founded.

Harry Schiffman: Director of government and community relations for Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, Schiffman has long been active with a number of community health, business and social service organization. He formerly worked for Public Advocate Mark Green.

Wellington Sharpe: A native of Jamaica but longtime resident of East Flatbush, Sharpe, a family counselor, is founder and president of a private company, the Nelrak Child Development Center. A member of Community Board 17, he has served on many the boards of many community groups and been politically active, including running unsuccessfully for State Senate.

Joel Toney: A native of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Toney was living and working in the United States when the island nation named him its ambassador to the United Nations. He has served on Community Boards 5 and 14, and is co-chair of the Environment Committee for Community Board 14.

Leithland “Rickie” Tulloch: A longtime financial officer for health care institutions, Tulloch has been a member of Community Board 17 for 15 years, particularly involved in land use issues. He was active in the effort to name part of Church Avenue for Bob Marley.

Campaign Finance Board Filings:

• Mathieu Eugene

• Karlene Gordon

• Jesse Hamilton

• Jennifer James

• Zenobia McNally

• Mohammad Razvi

• Harry Schiffman

• Joel Toney

Â

The Idle Rich

Forgive New Yorkers for envying their fellow citizens; it's hard to avoid. Librarians read recently in the New York Times that their bosses at the New York Public Library each make hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Teachers read in the Chronicle of Higher Education that many of the presidents in area colleges make about half a million dollars: John Sexton at NYU $798,989; Lee Bollinger at Columbia, $685,930; David Caputo at Pace, $672,239; Matthew Goldstein at CUNY, $471,500. But even Wall Street bonus babies, who are expected to be awash in money this year, reportedly complain because they aren't making as much as hedge fund managers.

But however much doctors envy bankers, or lawyers envy managers, there is one group that may attract the most resentment of everyone -- the idle rich, also known as trust fund babies, and coupon clippers (an archaic term, dating from a time when one needed to clip a coupon to get interest from bonds). These are people who do not work, living on the money from investments –- their own, or their family’s.

If there is resentment, there is also fascination. How else to explain Paris Hilton? E! True Hollywood Story even did a show on those “celebutantes” who try to cash in on their wealth to achieve stardom, including a quiz with such sly questions as:

Which heiress has a parent who not only competed in the Olympics but was once nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize?

Amanda Hearst

Zara Phillips

Athina Onassis Roussel

Paris Hilton

(The answer, to spare you taking the quiz, is Zara Phillips, the daughter of England’s Princess Ann, who competed as an equestrian in the Montreal Olympics and was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for her philanthropic endeavors).

The Village Voice looked at the issue last year in an article entitled Rich Little â€Poor’ Kids, quoting most of them anonymously: "Those who bear the dreaded "trustafarian" tag say they have problems with guilt, embarrassment, and most importantly, figuring out what to do with their lives."

Several years ago, Melik Kaylan, writing in the Wall Street Journal as part of an ongoing debate over the estate tax, said that inherited wealth allows people “to lead lives on a higher plane.” In response, Timothy Noah of Slate wrote that while he was sure that “some people who inherit vast sums of wealth devote their lives to contemplation and philanthropy,” his experience led him to believe that “enlightened magnificos constitute a very small fraction, and are dwarfed by the number of head cases, drug addicts, and rustic dropouts. (Abigail Trafford of the Washington Post coined the marvelous phrase "WASP rot" to describe this phenomenon.) “ Following up a week later on his article, Noah tried to make good on a promise “to hunt down statistical data examining the lifestyles of the idle rich--incidence of alcoholism compared to the general population and that sort of thing.” He admitted to not having found much.

But now, using a bit of data analysis suggested to me by He Huang, one of my graduate students at Queens College, I have put together an admittedly tentative and incomplete profile (using material from the census and the American Community Survey) of New Yorkers who do not need to work.

There were about 140,000 in the tri-state area in 2005 who received at least $60,000 in investment income. (To receive such an amount would require at least $1.2 million in assets).

About one-sixth lived in Manhattan; almost two fifths were in the suburbs. Those in New York City who do not work for a living are older, more male, more likely married, more educated and less minority than New Yorkers as a whole. About three fifths have been to college. Over 80 percent are white, about nine percent are black, about five percent Asian and about 10 percent Hispanic. About 60 percent are male and about 55 percent are married with a spouse present.

The median personal income of those who do not receive any unearned income is $15,000 while for those that do it is at least $191,200 (and may be much higher.) Only about one-quarter of those who are receiving such income are working, and about 10 percent are making more than $100,000, so many members of the group choose to spend their time in other ways. Indeed, very few report social security income, business or farm income, retirement income or wages and salaries. In short, their investment income is their main source of income. They are substantially older than all New Yorkers older than 15, but even among the younger ones only a small fraction work.

Unfortunately, we can not put together a picture based on the statistical data of how they spend their time, though we know that only a few are working full-time. Some undoubtedly volunteer their time, spend time at vacation spots, or work at jobs that pay relatively low wages, such as docents in art museums or other rewarding pursuits. There are very few surveys that would have enough information to even begin to depict the idle rich.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, Then and Now

The news that Metropolitan Life would like to sell Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village strikes some New Yorkers as the end of an era. The question is: Is the era that is ending one in which middle class people can live in Manhattan?

Both Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village are seen as one of the few remaining middle class bastions in a borough filled with the affluent and the poor.

Both places were built for the middle class, mostly returning veterans and their families. In 1950, residents at Stuyvesant Town paid a median rent of only $76, and those at Peter Cooper Village $100. This was a time at which the median income of the residents was $5,866. Thus, the median household paid only about 15 percent of its income for rent. By 2000, the median rent had climbed above $1,000, but since the median household income had shot up to $68,422, the median household still pays only about 18 percent of its income for rent. This is well below the 35 percent that is considered non-affordable, making the two complexes one of the few bargains left in Manhattan.

This is not likely to stay the same. The city is changing – has already changed -- and so are these two housing developments. It seems instructive to compare the demographics of its residents in 1950, shortly after they were built, with who lived there in 2000, the most recent census. (Conveniently Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village span two census tracts).

Married Then, Single Now

In 1950, the two complexes were places for young married couples with kids. In 2000, they had become a home for mostly unmarried singles and many older people.

In 1950, there were 31,173 residents living in 11,630 households in the two complexes. About one-fifth of the residents were five years of age or under. Almost 90 percent of all adult residents were married. Only 1.3 percent of residents were over 65. The make-up was not surprising -- there was a veteran's preference to live in the complexes, and the vets had recently returned home and begun families.

By 2000 the number of people living in the two complexes had declined to 19,101, but the number of households had only dipped slightly to 10,926. Over half the households were occupied by unmarried people without children. Only about four percent were five years old or younger, while almost one-quarter were over 65.

White Then, Mostly White Now (But Also Black, Asian, Hispanic)

When Stuyvesant Town opened in 1947, it excluded non-whites, which is why in 1950, out of more than 30,000 residents, only 114 were black.

By 2000 the complexes were about 8.3 percent black, 4.4 Asian and 5.4 percent Hispanic. About 15 percent were foreign born, the most from Asia, but substantial numbers from both Europe and Latin America.

Clerical and Professional Then, Professional Now

In 1950, of those employed (predominantly men) about one-third were in professional occupations, some 18 percent were managers, but 35 percent were either clerical or sales workers. By 2000 slightly more women than men were employed, but about two-thirds of both sexes were in professional or managerial occupations. So the occupational level of the residents had increased.

What Might Happen

If Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village are sold to a entity interested in moving the complexes to non-stabilized private sector rental, the prospects for middle class housing in the complex will be bleak, according to a recent article in the New York Times: "At Peter Cooper Village, where the apartments are more spacious, the average monthly rent for regulated apartments ranges from $1,178 for a one-bedroom unit to $1,581 for three bedrooms, while the average rents for market-rate apartments range from $2,662 to $5,842. At Stuyvesant Town, where hardly any of the standard apartments have more than one bathroom, renters in regulated apartments pay an average of $1,096 for a one-bedroom apartment and $1,514 for three. Average rents for deregulated apartments range from $2,406 to $3,833."

At 30 percent of income, to rent such apartment a household would need an income between $96,240 and $233,680. This would make the complex off-limits except to the top fifth of Manhattan residents. Only about 11 percent of current tenants have incomes approaching a level where they could afford the least expensive apartments in Stuyvesant Town.

Moving this huge complex to the free market rent will mean that the composition of the tenants will radically change. Even now, as tenants leave, the new occupants may face rents several times what had been paid. After substantial renovation most any apartment in the complexes could fetch above $2,000 rent and be lost to stabilization. The segment of the middle class that is still in Manhattan: those older and living out their days here, along with singles and others who work in professional and other jobs and a few families with children, will need to look elsewhere for housing.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

What New Yorkers Are Like Now -- First Results of the American Community Survey

Massive amounts of new census data were released just after midnight on August 15th, which show among other things:

1) New Yorkers have become much better educated since 2000.

2) Though immigrants continue to stream into the city, the number of foreign born residing in the city only increased by about 160,000 in the five years through 2005, well below the increases of the 1990s.

3) The number of blacks has declined in the city.

4) The number of whites has increased in Manhattan and now Brooklyn.

The midnight data dump was the first release from the United States Census Bureau's new American Community Survey. Three more releases from the 2005 survey are planned, including one on economic status (August 29th), one on housing, and one on detailed characteristics by race and Hispanic status. In the future, the data will be constantly updated.

Some of the questions that the American Community Survey will ultimately answer include:

1) Has Manhattan become even more unequal? After the 2000 Census the richest 20 percent in Manhattan had incomes 50 times those in the lowest 20 percent. Could this have increased?

2) What changes are discernable in the various community planning districts?

3) If the net number of foreign born residents is increasing more slowly than it was in the 1990s, while the number of Mexicans is soaring, which groups are showing a decline?

4) Has the trend toward a more highly educated population in the city and especially Manhattan affected the housing opportunities of affluent and non-affluent New Yorkers?

5) How are the various immigrant groups faring in the post 9/11 world?

American Community Survey

The advent of the American Community Survey represents a sharp departure from the way the census bureau collected data on so-called social and economic characteristics in earlier decades.

It is important to realize that the census bureau’s clients are the United States Congress and the governments of the 50 states. The United States Constitution requires that there be a census every ten years in order to carve the United States into an appropriate number of Congressional Districts, each representing the same number of residents. This redistricting and reapportionment also occurs on a state and local level, for legislative, judicial and other districts.

To accomplish the redistricting, the Census Bureau need only collect a handful of variables – the location of each person, age, sex, race, Hispanic status, whether one owns or rents a house or apartment or lives in a group quarters (such as a college dorm, prison, or chronic care hospital).

Along with these so-called "short form" data, a sample of respondents in the past was asked many more questions about income, occupation, veteran status, citizenship, education, disability status, ancestry and ethnicity, migration, journey to work, and so forth. About one-sixth of the households in the United States, or about 18 million, received this "long form."

The American Community Survey is the replacement for the long form. It is a rolling survey with a set number of interviews each month totaling about 3 million per year. One of the largest advantages of this survey is that those doing follow-up will be professional interviewers, and methods have been established to count hard-to-reach groups effectively. Five years of testing ensures quality control. As more and more data become available; in all, the census bureau will publish about 15 million records. Information on tracts and block groups, the small areas that were released for the "long form" will be available in 2010.

The just-released 2005 American Community Sruvey includes some data for places and counties with population 65,000 or larger, including most of New York City's community planning districts, which are released as areas called Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMAs). PUMAs are required to contain at least 100,000 people, and there are about 2,100 across the country. New York chose to make them largely coincident with the community planning districts. However, since the sample is not quite three percent, one can expect that only about 2,500 people will be interviewed in each PUMA or planning district. This means that for very detailed variable categories, such as the 123 individual foreign birthplaces that are counted, most PUMAs may have a very small number of a given population type. When this occurs, the census bureau suppresses the data since no accurate estimate of such groups are possible.

So far the American Community Survey has provided a surprising new look at NYC. Though immigration is continuing, immigrants along with non-immigrants seem to be leaving the city. The increasing affluence of Manhattan seems to be spilling over into Brooklyn. These and other trends mean that the remaining data releases are of great interest. We will know now how New York City is evolving, we will not have to guess or wait until the results of the new census in 2012.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Ethnic Politics in Changing Flushing

|

New York State Assembly- District 22: The Candidates • Ellen Young, former district administrator (D). Other Races • New York State Assembly- District 57: Succeeding Green in Fort Greene – and Beyond • New York State Senate-District 13: Bringing the Money Back from Albany |

When Jimmy Meng became the state assembly's first Chinese American member in 2004, many people credited ethnic appeal in an increasingly Asian district. Meng, suffering from chronic back pain, has decided against running for re-election. The ethnic politics of the Queens district will likely come into play again as three candidates vie for his seat.

Three candidates are running for the Democratic primary. Ellen Young, worked for Councilmember John Liu before stepping down to campaign. Julia Harrison, who held Liu's seat in the council before stepping down due to term limits. Terence Park, a district leader, and member of Community Board Seven, was removed from the ballot for a technicality but successfully appealed, reversing the decision. Young is Chinese, Harrison is white, and Park is Korean.

Meng's daughter, Grace Meng, also attempted to run for the seat, but was removed from the ballot after it was determined she did not live in the district. Young has raised about $250,000, and Terence Park has raised $219,000, while Harrison has raised $32,000. The primary winner will face Republican candidate Christopher Migliaccio in November.

ETHNIC POLITICS

Young and Harrison insist that race is not an issue in the campaign. But some frame the election as a contest between the old, mainly white Flushing represented by Harrison, and the changing, more racially diverse community represented by the Asian candidates. Fifty-one percent of the district's residents are Asian.

"It is very obvious and very honest to say that race is a factor … but real voters care for what your record is about," said Park.

Young is considered an immigrant advocate, and has served as the president of the Chinese American Voters Association, and has organized programs to help immigrants fill out Census forms. Harrison and Park, meanwhile, say immigration issues should be left to the federal government. Harrison has questioned the very practice of categorizing people as immigrants, and says that as long as they are citizens she would represent them like any other constituent.

Harrison's comments about immigrants have led to trouble in the past. In 1996 she was criticized for making derogatory comments about Asian Americans when she was quoted saying they "were more like colonizers than immigrants. The money came first. The paupers followed, smuggled in and bilked by their own kind." She maintains that her words were misconstrued.

Harrison has said the Democratic Club of Flushing, Whitestone and College Point asked her to run because it felt that the other Democratic candidates were running on personal and racial appeal, but lacked legitimate experience. Young maintains that her two-decade record of public service is more than adequate experience.

SIMILAR PHILOSOPHIES, DIFFERENT FOCUSES

Candidates have largely focused on relatively uncontroversial issues, such as an increased police force, more funding for schools, and better transportation. The candidates did, however, have different plans for how to best achieve common goals such as safer streets. Young, Park, and Harrison mentioned increased police presence to fight crime, while Migliaccio focused on stronger penalties to deter crime.

Park focuses on overdevelopment, saying that plans for downtown Flushing could bring "chaos to our community" if better planning for parking is not taken into consideration. He also worries that the character of the neighborhood is threatened by increasingly dense residential construction projects.

"There are too many developers invading our neighborhoods and knocking down houses to build multiple dwelling houses," he said.

In regard to education, the candidates agreed upon the need for increased funding for public schools and increased hours for after school programs. Migliaccio, however, differed from the Democratic candidates in emphasizing the need to give students the means to obtain education out of district, instead of limiting educational funds to improvements within the district.

Transportation was also a frequently mentioned issue. Migliaccio and Harrison emphasized the importance of extending the 7 subway line to reach farther into Queens. This would better connect various neighborhoods of Queens to one another, as well as giving residents of the farther bounds of the district better access to Manhattan.

One area of contention, however, has been that of health care. While Young and Harrison spoke of improving Medicare and Medicaid, Migliaccio disagreed. “I don’t think the state should be the primary provider,” he said. “That’s not our job.”

Â

The Way in San Jose

|

Taking the Public Pulse |

San Jose is the third largest city in California, larger than San Francisco, larger than Oakland. We have a $2.7 billion combined budget, about 6,700 employees, 27 departments and offices, 10 council members elected by district and a mayor elected at large.

We deliver services. We are not just a group of people who get together to drink coffee or stand around a hole in the street and take home nice salaries and good benefits.

The customers only see the results of what we do. They may see us standing around the hole, but then they have to drive across the field once the hole is filled in. That’s what most people see: how the hole is filled in, if the street is smooth or not.

Surveys are very different from normal ways that we receive information, policy desires and even service requests.

In the survey, many of the people who give us information are not registered voters or likely voters. They are probably not the people who show up at meetings. They are not the people who get together in a neighborhood association. Some of them are probably not even citizens. We actually don’t call it a citizen survey; we call it a community survey because almost half of the respondents in some of our neighborhoods are probably not citizens.

We do the survey every two years on the telephone in English, Spanish and Vietnamese. A hundred questions. That selects out certain people right there; you have to have 20 minutes to spend.

It covers issues. What’s the major issue for San Jose? What’s the condition of your neighborhood, what’s the condition of the streets?

Half of these questions relate directly to performance measures. Others are, “What do you see as the major issue? What would you like done?” That sort of thing. We ask if people volunteer and a bit about demographics. And finally we do a couple of research questions.

Our report is done by a survey consultant, who is a pollster. It is under the direction of the city manager. We feel, of course, that it is balanced, fair and honest.

The survey got us the first positive headline in a while on the front page of the Mercury News. It said that San Jose “was a good place to live.” Seventy-nine percent of the people thought the quality of life was good, up four percent since 2000. Seventy-six percent were satisfied with services. Eighty percent were happy with our employees.

A couple of survey questions that were new this year were surprises. We asked people “How do you want to get services or find information that’s not emergency in nature?” People want to call a person. They don’t want to go to a Web site, they don’t want to go to a call center. That surprised me because I think the 311 system is a great gateway and having a good Internet page will be a gateway of the future. But it’s clear that, even in the capital of Silicone Valley, we are not quite there.

We have learned some lessons. There are multiple voices in government. You don’t have just one customer who pays. You have customers who don’t even use the service, but who care as well.

Brooke Myhre is with the budget office of the City of San Jose, California.

Â

Hitting the 9 Million Mark

New York City’s population will reach 9 million around 2025, according to a spate of demographic projections featured in various news stories. But will the city really hit the 9 million mark in the next 20 to 25 years, as Con Edison, researchers for the Metropolitan Transportation Council, and Deputy Mayor Daniel Doctoroff predict?

The answer is a resounding yes, if one accepts the underlying assumptions of such projections. But since, like all projections, these estimates seek to predict the future, we will not be able to judge their accuracy for many years to come.

To get a sense of their accuracy though, we can compare projections with recent estimates and with patterns of historical growth. Urbanomics has produced one of several such studies projecting 9 million New Yorkers. To arrive at that number, it expects a growth rate in New York City higher than the rate between 1940 and 2000 and well in excess of what has occurred since 2000, as estimated by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Estimating New York City

The census estimates of New York City's population in the 1990s vastly underestimated the city's growth. (See Gotham Gazette.) Since 2000, however the bureau changed its procedures. It is instituting a new American Community Survey to provide a yearly census update. Along with records of births, deaths, and internal migration from the Internal Revenue Service data, that survey tracks the foreign born population. The first full release of the survey is due at the end of August and could change the picture of the city’s current and projected growth.

But the figures now available indicate that, since 2000, the estimated growth rate varied from a high of 0.718 percent between 2000 and 2001 to a small loss in population between 2004 and 2005. On average, the estimated growth rate since 2000 has been 0.353 percent. (These figures are summarized in Table 1.) Now many theorize that the growth rate has surely slowed, a consequence, they believe, of a slight ebbing in immigration, the end of the stock market boom, and the shock of 9/11.

But despite all that Urbanomics projects a much higher growth rate of 0.564 percent for the 30 years through 2030. Since the city’s population increase for the first five years of that period has already failed to reach that level, New York City’s growth must rise in the next few years if Urbanomics and its colleagues are to turn out to be correct.

A Century of Population Growth

New York has been the largest city in the country since 1790. (Since the consolidation of the city in 1897, the city population includes all five boroughs.) Table 2 shows the census population for each decade from 1900 through 2000, the percent change from the previous census, and the annual growth rate (compounded).

The decades from 1900 through 1930 were years of explosive growth. In many ways, New York City was the Sunbelt of the 1910s and 1920s, with its population more than doubling from 1900to 1930.

But to evaluate the new projections, the decades from 1940 through 2000 are especially relevant, since by 1940 much of New York City's transportation infrastructure was completed, the vast bulk of its road network already existed, and many buildings still in use had been erected. In short, New York City looked much like it does today in many ways.

As the data make plain, New York City was very near the 8 million mark twice -- 1950 and 1970 -- but in both instances the city then lost people. Indeed the population was officially at little more than 7.3 million in 1990. Economic downturn, white flight and the slowing of immigration until the 1980s led to New York City's slow growth until the last decade of the 20th century.

Then, quite unexpectedly, the population reached 8 million in 2000, spurred largely by the city's economic rebound and the robust increase in immigration.

Some of the apparent growth from 1990 to 2000 was simply the result of better counting in 2000. The difficulties and uncertainties in counting New York City's population led to a substantial undercount in 1990.

Despite all this, though, during the whole period from 1940 through 2000 the average growth rate (compounded) was 1.21 percent, less than one-quarter of the optimistic rate projected by Urbanomics and similar prognosticators for the next 30 years.

Assuming and Projecting

The latest high growth projections imply a population growth rate that vastly outstrips the historic growth patterns in New York City from 1940, as well as the recent brisk growth estimated since 2000. Small differences in a rate of growth for one year, when compounded, result in very large differences in projections.

If New York City grew during the 30 years after 2000 at the rate it averaged from 1940 to 2000, including that period’s booms as well as its two population declines, the population by 2030 would be about 8.3 million. If the average growth for the 30 years starting in 2000 matches the recent census estimates, New York City will almost reach 8.9 million by 2030. But the Urbanomics estimate expects an average growth rate of 0.564 percent through 2030 resulting in almost 9.5 million New Yorkers.

So, in predicting the future, it depends on how one views the past and the present. Historical population trends would seem to imply very little growth in population between now and 2030. A continuation of recent trends would imply somewhat more growth. And relying on a series of economic assumptions could put New York City's population at about 9.5 million by then.

Framed this way, it seems it could well take considerably more time than Urbanomics and others predict for New York City's 8 million to become 9 million. But only the future will tell for sure.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

New York's Asians

Who are the Asians of New York City? They are foreign-born and native-born New Yorkers with a background in East Asia (China and Japan, for example), Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia), and South Asia (India, Pakistan and Bangladesh), according to the official U.S. government classification of the Asian race. (Those from Central Asia -- Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey, etc. -- are not included.) Members of these diverse populations now constitute about 11 percent of the city's population.

But can one really consider as one race people coming from several continents and speaking many different languages?

It should not be surprising that Asian groups vary greatly from one another.

Taken as a whole, though, there are some generalizations that can be made based on recent census data. The vast bulk of Asians in the metro area live in or near New York City, as the accompanying map shows. In fact, over half of all Asians in the tri-state area live in the city.

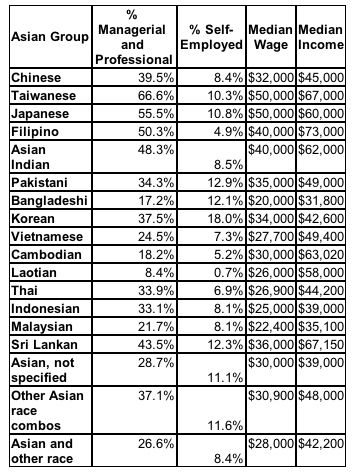

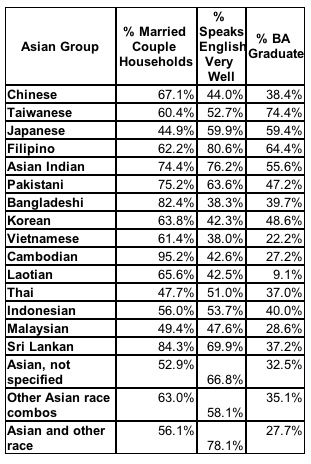

Asian households also have higher median household income than any other of the main racial groups except for whites.

But there are sharp differences as well. The command of the English language varies greatly by group. Only about 38 percent of Bangladeshi speak English well, while over 80 percent of Filipinos do. The proportion of those over 25 years of age who have a BA degree also varies greatly, from a low of 9.1 percent for the Laotians, to a high of 74.4 percent for the Taiwanese. The proportion holding a professional and managerial job varied from 8.4 percent for Laotian and 17.2 percent for Bangladeshi to over 66 percent for the Taiwanese. The percent self-employed also varied greatly, with Koreans in the lead with 18 percent. In terms of wages the Taiwanese and Japanese had median wages of $50,000, while the Bangladeshi had only $20,000. Other groups were also quite low including: Thai, Vietnamese, Maylaysian and Indonesian. Household income also varied greatly among the Asian groups. Figures for the Filipino was $73,000, while Japanese, Asian Indian, Cambodian, Taiwanese and Sri Lankan were all at least $60,000. However, Bangladeshi, Maylaysian, Indonesian and Asian not-specified all report median household incomes less than $40,000.

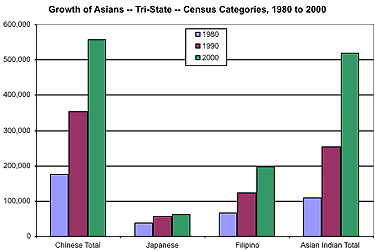

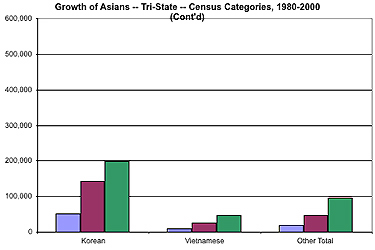

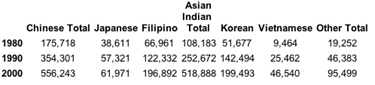

Growth of the Asian groups in the New York area has been dramatic for the last several decades. Though growth since the 2000 Census is not reported for the various Asian groups in a reliable way, the pattern of growth shown in the accompanying figures likely has continued.

The charts show a dramatic increase in Chinese (which includes mainland, Taiwanese and other Chinese), and in Asian Indian, which includes Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Indians, as well as in the Filipino population. The growth of Korean and other groups though marked is not as strong.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â