New York City is reeling from the Crash of 2008. Unemployment in the city has increased from 5.1 percent in May 2008 to 8.9 percent in May 2009. New York City's Independent Budget Office predicts a substantial decline in employment and revenue for the next three fiscal years.

The Bloomberg boom has become the Bloomberg bust, and it may be with us for the next several years. Furthermore, as the city recovers it seems unrealistic to expect that the finance sector, the city's economic driver, will soon regain its full luster. It may well be a long, long time before it once again spins off new high paying jobs in finance, much less in industries that cater to finance and generates the billions in tax revenues that the city and state have come to depend upon. A close look at the finance industry in New York reveals not only what everyone know -- that it paid well -- but that the largesse extended to people in a variety of occupations, who will now all bear the brunt of its decline.

Blowing Up the Bubble

Through 2007, the finance sector rode a wave fueled by its packaging of mortgages as derivatives, creating and selling insurance for these mortgages and securities, rating these instruments as triple A, and selling them through financial institutions to various funds and institutions worldwide. Indeed, many in finance made literally millions, some multi-millions, doing this business. The lawyers handling the deals also became wealthy.

As analysts and journalists explore the wreckage wreaked by the finance sector upon the city, the country and global economy, it is now obvious that much of the prosperity was based upon a huge bubble. The bubble generated billions of dollars in bonuses, profits and tax revenues, and thousands of jobs. The growth and prosperity of this sector really began as the city emerged from the crash of 1987, through the 1990s, and rose again after the tech crash in 2000 and 9/11.

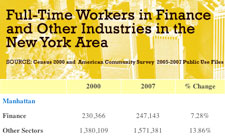

Just before the meltdown the finance sector employed some 475,000 full-time workers in the New York metropolitan area, including parts of New Jersey and Connecticut, Long Island and the northern suburbs in New York State. Of these, 287,000 or 64 percent worked in New York City. Of the city workers, 86 percent worked in Manhattan.

Interestingly, though, while jobs in finance increased by 7 percent from 2001 to 2007, the number of jobs in all other sectors increased by even more. In 2007, jobs in finance accounted for 7.01 percent of all jobs in the metropolitan area, down slightly from 7.14 percent in 200.

(Table 1has information on the full-time employment of workers in the finance sector between 2000 and 2007).

The crash and meltdown have led to the unraveling of much of the finance sector. All investment banks have now become conventional banks, Lehman and Bear Stearns are no more, Merrill Lynch is part of the Bank of America, Wachovia of Wells Fargo and many banks have announced layoffs, and most are now partially owned by the U.S. government. Though Goldman seems to have dodged much of the bullet, as has JP Morgan Chase, the same cannot be said of Citigroup and some of the other large banks, former investment banks, brokerages and insurance companies, such as AIG.

The Finance Workforce

The financial area lost 37,400 jobs in the metropolitan area from May 2008 to May 2009, decreasing 4.7 percent, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has reported. "Over the year, New York City shed the most financial activities jobs since September 2002 with the city's securities, commodity contracts, and investments industry accounting for almost 60 percent of the area's job contraction in the sector," the bureau found.

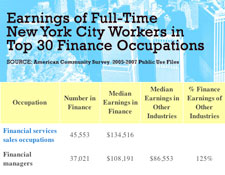

As finance led the city and region into a boom, it is now leading them into the most serious economic downturn since the Great Depression. As Table 2 shows, jobs in finance cover a wide array of occupations. Many jobs are sales jobs; others are directly related to finance and management. For instance, sales was the number one occupation in finance followed by financial managers, and other financial specialists were number three. However the top 30 finance occupations includes computer professionals; secretaries; software developers; office supervisors; bank tellers; guards, watchmen and doorkeepers; receptionists and other garden variety occupations. Obviously, the need for salesman and managers has substantially declined. But the reductions in finance also include the other ancillary occupations that supported the industry.

In general, as table 3, above, shows, these jobs in finance paid better than similar work in other sectors.

Grouping the occupations, one finds that for all types of jobs, the median earnings in finance were higher, often substantially higher than in other sectors. Indeed, for all full time workers, finance median earnings were more than double those in other industries, and for the top 10 percent of earners, finance paid almost five times as much as other sectors. Many finance jobs were in sales and management, two areas where earnings were much higher for those in finance, however all workers were paid more in this sector, even support staff, which paid 14 percent more than their counterparts in other fields.

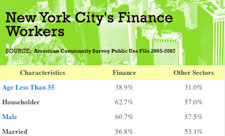

Aside from being very highly paid, compared to others, those working in finance were different in other ways, as Table 4 shows. They are younger than the average New York City worker and more likely to be male, live with a spouse and reside in an owner occupied dwelling. More of them are white and Asian and fewer are black, Hispanic or multi-racial. They are less likely to be foreign born and much more likely to be college grads -- 69.4 percent versus 42.3 percent. In short, they were richer, whiter, and more educated than other city workers.

The decline of the finance sector is now in full swing. Already, about 10 percent of the finance jobs have been lost. More are being lost daily. Manhattan and the tonier sections of Brooklyn have faced sharp declines in housing prices, and even in rent. Laid-off financial executives and sales people are looking for other lines of work.

The collateral damage of both the bubble and bust will affect all New Yorkers. Those such as high-end car dealers, real estate developers and the like, along with restaurant owners and even storefronts selling Chinese take-out already have been affected. Though some New Yorkers may get satisfaction from seeing the finance sector and its rich employees take a beating, in fact, all of us will be worse off from the crash. Because even if the gains may be seen as "ill gotten," we all depended upon them. Replacing or rebuilding the sector will not bring back the days of wine and roses. Soon the boom of the early 21st century may be just a distant memory, as we all learn to live with much more straitened circumstances.

Andrew Beveridge, professor of sociology at Queens College and the Graduate Center of CUNY and instigator of www.socialexplorer.com, has been in charge of the demographic topic page since January 2001.