Animal Rights Activists Split Over Bill to Save 'Oreos'

Photo © Don Brandenbur

The sad story of Oreo the dog made headlines last year. Now her unfortunate death may spur a change in state law that could, supporters believe, ultimately lead to saving more animals from being put to sleep.

Oreo, a one-year-old pit bull mix, was thrown off the sixth floor roof of a Brooklyn public housing project. After surviving the fall, she was rescued by the ASPCA, which operated on her broken ribs and legs, nursing her back to "health" over the next several months. However, ASPCA professionals ultimately deemed Oreo to be too aggressive, the result of so much trauma, and decided she had to be euthanized.

Pets Alive, a group opposed to euthanasia and claiming to have experience in animal rehabilitation, tried to save Oreo. Its representatives maintain the ASPCA willfully ignored those efforts. While the ASPCA disputes that, Oreo was eventually put down.

Thus followed an uproar from the animal rescue community. Almost immediately, Manhattan Assemblymember Micah Kellner submitted legislation -- "Oreo's Law" -- to prevent adoptable pets from being destroyed; Tom Duane sponsored a similar version in the State Senate. Advocates include assorted local and national rescue and no-kill organizations and several of the nation's top law professors.

While most rescuers agree that sometimes an animal is indeed too injured to save, a key issue concerns determining whether an animal's damage or suffering is "too" great. Moreover, many in the community argue that city shelters and established organizations like the ASPCA may use euthanasia on healthy animals or on animals that could become healthy because of space or financial constraints. Oreo's law "requires the release of a shelter animal to a rescue group upon request of the rescue group prior to euthanasia of the animal." Supporters believe greater access for more no-kill rescue groups will translate into more animals being spared.

From California to New York

Kellner's bill is based on a 10-year-old California law named for former State Sen. Tom Hayden, who wanted to reform that state's shelter system. The goals included promoting animal adoption, reducing euthanasia rates and creating a system for animal control shelters to place at-risk animals with no-kill groups instead of killing them. According to Kellner, Oreo's Law is a "bigger Hayden's Law for New York."

The original version has been rewritten to address concerns of opponents and proponents alike. It now includes establishing liability, exempting animals deemed dangerous by a court of law, and prohibits rescue groups that have been charged with or convicted of neglect, abuse, or dog fighting from being able to take animals. The bill also includes a definition of physical suffering.

"This is the best possible compromise for the greatest number of animals," Kellner observed.

Detractors, though, fear shelters would be forced to turn over animals to just any rescue group -- whether suitable or not; that some groups might horde animals or worse; and the law would create additional expenses for providers like the ASPCA by requiring longer hours, additional staff and larger facilities.

Saving Animals

Traditionally, most animal rescue organizations are volunteer efforts aimed at rescuing otherwise healthy homeless animals and placing them in foster or permanent homes. The animals usually come from the street or municipal shelters.

In New York City, the Mayor’s Alliance for Animals was founded in 2002, and consists of approximately 160 rescue non-profits with a no-kill (anti-euthanasia) objective by 2015. (February is I Love NYC Pets month, a series of events designed to encourage adoption.

The ASPCA is a founding member of the alliance and, according to Anita Kelso Edson, its senior director of media and communications, provides significant funding to the Mayor's Alliance.

After the ASPCA stopped running city shelters in 1994, the city created Animal Care and Control to fill the void in animal control the next year. Edson said the ASPCA also provides that group with funding.

"The ASPCA 'pulls' more animals from AC&C than any other single agency,” wrote Edson in an email. The society, she said, took in "more than 1,200 dogs and cats" in 2009, including many in need of medical care. According to Edson, a total of 17,600 cats and dogs were transferred out of Animal Care and Control by all groups and individuals in 2009.

Rescuers say taking animals from the Animal Care and Control, and finding other homes for them is of the utmost importance because of terrible overcrowding there. They believe this overcrowding has lead to the death of countless animals because there’s been no room for them.

Supporters of Oreo's law said it would reduce overcrowding by allowing more groups to pull animals from Animal Care and Control. That would lead to more animal being placed, reducing the likelihood of euthanasia.

This issue was underscored by a recent emergency email disseminated by an Animal Care employee. "We need your help! Our shelter is COMPLETELY full. We are even turning away owner surrenders because we have NO cage space. … We have no room and that means tomorrow’s euth list is going to be enormous," pleaded the worker.

In response to the communiqué, Animal Care director of administrative services Richard Gentles emailed that the shelter tries, "to maintain open cage space for newly arriving animals. … Each day people are in our shelters adopting and we are transferring animals to rescue groups. Therefore, cage/kennel space is always being turned over."

In a later email, Gentles admitted, "We unfortunately have to euthanize animals for space, behavior and illness."

Money and Access

The dispute over Oreo's Laws comes as Animal Care and Control's euthanasia rates have hit at an all-time low. As recently as 2002 the euthanasia level was as high as 75 to 80 percent, reported Shelter Reform Action Committee. It’s currently about 32 percent.

Gentles credited the decline to work with the mayor's Alliance for Animals and to new initiatives. For example, the New Hope Program serves as a network to distribute animals who aren't adopted directly from the Animal Care. Maddie's Fund is a low-cost spay/neuter project, available to city residents on public assistance.

Despite such efforts, almost 43,000 animals still enter the city's shelter system every year. Meanwhile, Animal Care and Control, like all city agencies, faces budget cuts. It's "about a 4 percent decrease in FY10," according to Gentles, but "the impact on operations is unknown."

"We don't want to lose any ground. We don't want to take steps back," he continued. And, "we don't want to euthanize animals for space."

Oreo's Law, according to Kellner, would save cities money by transferring some costs, such as housing and feeding as well as euthanasia, onto participating rescue groups.

The law also would provide more groups with access to animals needing care. Currently, critics charge that the criteria use by the alliance and Animal Care to accept or reject partners can be capricious and even punitive.

"It's willy-nilly," said Kellner, who recounted tales of groups being arbitrarily or incorrectly barred from the network.

Brooklyn Animal Foster Network director Laurie Bleier recounted online how a previous Animal Care director disqualified her organization after it had removed more than 1,000 animals from Animal Care. "My group was banned because one of my dogs in foster care was found to be emaciated," she wrote. "After a thorough investigation … those charges were found to be completely baseless and the case was dropped. Despite our complete exoneration ... we have not had due process to regain our status."

Opposing Opinions

The bill has exposed rifts in the animal rights community. One of the measure's strongest advocates is Nathan Winograd, director of the No-Kill Advocacy Center, who touts it as a "second chance for animals." He said some groups in the alliance fear reprisals if they support the measure. For its part, Winograd believes the alliance worries the bill could reduce its influence. "If this law passes, and the grassroots is empowered, they lose control," he said in an email.

Alliance president Jane Hoffman sought to downplay the rift. "We are all working toward the same goal -– to save animals lives. ... Shelters and rescue groups are not and should not be enemies," she responded in her own email.

Hoffman said the alliance does not take positions on legislation." However, as an animal lawyer, she has concluded "that there are better ways of developing cooperation between shelters and rescue groups" than Oreo's law.

The organization most vociferously opposed to Kellner's bill has been the ASPCA. At the time of Oreo's death, it released a statement, saying, "We have done everything humanly possible to save Oreo's life; yet, as a result of the abuse she suffered ... she has come to a place where she can no longer be around people or other animals. We make this decision -- and others like it -- with a heavy heart."

The group thinks the law might place too many restrictions on shelters. "A successful transfer program requires … discretion on the part of shelters to determine, in good faith, whether transfer is in the best interests of the individual animal, the shelter and the public-at-large," Edson wrote, especially in New York State, where shelters and rescue organizations are largely unregulated.

Ironically, Oreo's Law advocates say that National ASPCA president and CEO Ed Sayres championed Hayden's law. And in 1999, when Sayres was president of the San Francisco chapter of the SPCA, he testified against its repeal.

"There is no inherent discrepancy -- laws in different states even on the same subject can be very different, " wrote Edson. "That was a comprehensive law change after a lot of public hearings and deliberation, and it was also 10 years ago, and in a different state where there was a serious problem."

The ASPCA has faced widespread criticism for its position on the New York bill. Protests have been staged in front of its building and Sayres' residence. Online petitions have called for Sayres' resignation, and numerous web postings have assailed the organization.

According to Winograd and Kellner, the ASPCA has been on the defensive since Oreo's death and the euthanasia of a dog named Max in December. "To have the incident memorialized forever by the name of the proposed law would be to remind animal lovers of that betrayal," Winograd wrote. "They are trying to confuse groups and others into opposing the law by claiming it would put animals in harm's way by opening them up to being placed in hoarding situations or with dog fighters."

Additionally, the ASPCA's opposition also explains why certain rescue groups and the alliance won't take an official position on Oreo's Law, according to Winograd. "Some are supporting the ASPCA because they are financially beholden to the ASPCA or want a share in the ASPCA’s largesse," he said.

Enmity against the ASPCA has gotten so bad that one group, Best Friends Animal Sanctuary, tried to mediate between the two sides. "We're trying to get folks around the table. A lot has been personal," described Francis Battista, Best Friend's cofounder.

As the debate swirls, some animal advocates fear people have lost sight of the real issue -- that too many, usually healthy, animals are euthanized every day. The debate has "become distorted, and out of context," complained Jennifer Panton, president of United Action for Animals and co-creator/head of the Animal Care and Control's Cruelty Seizure Committee. "The public needs to be reminded, on average per day, 45 animals are put to sleep."

For its part, the ASPCA may be backing off from its opposition to Oreo's law. "We understand that amendments to recently proposed legislation have been drafted and address some of our concerns," Edson wrote. "As always, our goal is to help develop or support legislation that we believe will do the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of animals."

Jillian Jonas is a freelance journalist focusing on local and national politics, government and public policy. She is a former national political analyst for U.P.I.

After Escaping Domestic Abuse, Survivors Confront the Housing Crisis

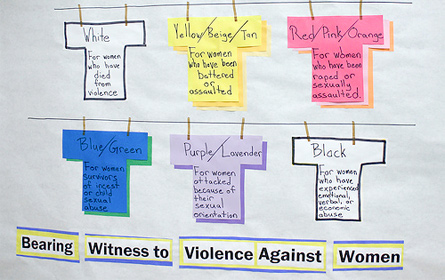

The Clothesline Project seek to draw attention to the problem of violence against women.

Emergency response to domestic violence survivors and their children has, over the past two decades, come a long way. Those who work in the field can point to a partnership of shelters and advocacy organizations, government offices, legal experts and police precincts that now provide assistance to protect women and their children from dangerous and abusive partners.

Despite these significant advances, the city still has not come close to meeting the need for shelter beds and for transitional and permanent housing. This forces many survivors to choose among street homelessness, the revolving doors of the city's homeless shelter system or returning, with their children, to their violent abuser.

Even with a 35 percent increase in emergency shelter beds for survivors and children over the past year, emergency shelters report they turn away hundreds of callers away everyday. Many of those they do shelter fail to secure follow-up transitional and permanent housing.

The Epidemic of Abuse

Advocates say one in four women experience a domestic violence incident. The New York City Domestic Violence Hotline answered more than 134,000 calls in 2008, an average of 370 calls per day. (The hotline, which provides help in many languages, operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and can be accessed by calling 911, 311 or 1-800-621 HOPE.)

City police responded to more than 234,000 domestic violence incidents in 2008 -- an average of more than 600 incidents per day.

The Role of Law Enforcement

This level of police involvement represents a huge change in just a few decades. Thirty years ago, police often did not respond to domestic violence complaints. Many thought such violence was a private family matter and that a woman was her husband's property. Officers essentially blamed the victim.

Now, the New York City police respond and "respond skillfully", said Maureen Curtis, associate vice president of Bronx Criminal Justice and Community Programs for Safe Horizon, one of the largest providers of services to survivors of domestic violence in the country. Advocates credit some of this to the state's Mandatory Arrest Law, enacted in 1984, which requires police to arrest the abuser under certain conditions.

Training in domestic violence intervention has also improved. Safe Horizon advocates can be found in 13 of the city's 84 police precincts, concentrating on those with the highest crime rates. High crime districts are also the districts with the most reported domestic violence incidents, according to Curtis.

Getting Help

Most survivors have called the police and the domestic violence hotline many times before they try to break free from their abusive partner and seek emergency shelter.

Once they make that decision, though, there is no guarantee they will find the shelter they need, according to Sanctuary for Families, the largest nonprofit agency in New York aiding victims of domestic violence and their children. But only "several hundred" get emergency shelter.

While many victims can stay with friends or relatives, hundreds of women seeking shelter are turned away from Sanctuary every day for lack of available beds, said Shugrue dos Santos, deputy clinical director of Economic Empowerment Programs for Sanctuary for Families. "All our services are overextended and we are asking the city for more shelter beds," Shugrue dos Santos said.

The Human Resources Administration administers some 50 emergency shelters for 700 families with approximately 2,500 emergency shelter beds citywide. The maximum stay for emergency shelter is 135 days.

As soon as the victim enters the emergency shelter, counselors try to determine her safety risk. The survivor and her children will be assessed for trauma by a psychiatrist and a psychologist.

"The children need crisis intervention services not only because of the devastating impact of watching their father beat their mother but because in 60 percent of the cases we get, the father is also battering the kids," Shugrue dos Santos said. She added that survivors arriving at the shelter are suffering from post traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression or bi-polar illness, and often have medical problems like asthma and high blood pressure that are exacerbated by the stresses of abuse.

"Sanctuary's roots are feminist, rooted in the belief that gender oppression and inequality is at the root of domestic violence. Violence occurs when one person uses their power to control another person," Shugrue dos Santos said.

Not all victims of domestic violence are women and not all perpetrators are men. Also, men are abused in both heterosexual and gay relationships. However, statistics indicate that these forms of domestic violence are much less frequent than men abusing their female partner.

"Shelter is a last resort, a place to hide. It's reserved for families in acute safety risk, and only after all other options fail. …These women come with their kids and a garbage bag of clothes,” Shugrue dos Santos said. "They have tried to get away from the abuser many times before. It's a choice between … a full refrigerator and hunger. Many survivors choose the full refrigerator for their kids over their own personal physical safety."

Different Women, Different Needs

Not every victim of violence falls under the stereotype of a badly bruised victim "fleeing in the middle of the night," said says Barbara Brancaccio, spokesperson for the city Human Resources Administration. "Every client comes in at a different place in her life, with her own set of options, her own individual needs, her own unique scenario. Some can find a job on her own, while others need employment training and placement. In some cases, the woman must get public assistance, but others have money and income of their own."

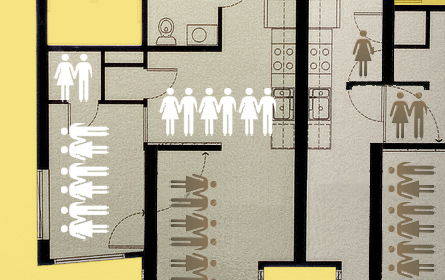

The New York City Family Justice Center, a partnership of government and nonprofit domestic violence agencies all under one roof, is an example of the evolution in domestic violence services. While the centers -- one in Brooklyn and one in the Bronx -- doesn't offer anyone a bed, it is a multi-faceted, all in one stop, emergency intervention, needs assessment and resolution center. In one visit, the victim can get help finding emergency shelter, documenting and filing a police report, and applying for public assistance. She can be examined by a forensic medical practitioner, get legal help, meet with advocates from non-profit agencies, and, if she wants it, get spiritual counseling. Help comes in 150 languages.

According to the mayor's Office to Combat Domestic Violence, 96 percent of victims who used the services of the Family Justice Center did not report subsequent harm from their abusers. And there was a 36 percent decline in domestic violence homicides in 2007, which the office credits to the work of the Family Justice Center.

After the Shelter

Following their time in emergency shelter, survivors need permanent housing. The Human Resources Administration tries to find transitional homes for shelter clients who need a place to stay for an extended period while they wait for permanent housing or other services to come through.

According to Shugrue dos Santos, approximately 20 to 25 percent of Sanctuary emergency shelter clients move directly into permanent housing. Of those who need to go into transitional housing first, about 50 to 60 percent then find permanent homes.

Some survivors choose homelessness over returning to a dangerous home. "These women don’t have the option of moving out of state to stay with a friend or relative. They’ve already tried that and their husband has tracked them down, putting their extended family members at risk as well," Shugrue dos Santos said.

Women coming out of shelters confront the general scarcity of affordable housing in New York City. “While domestic violence cuts across all socio-economic lines, race, and ethnicity, 98 percent of our clients are, at or below, poverty level,” says Shugrue dos Santos. About 70 percent of Sanctuary clients are immigrants and about 30 percent are not legally documented, making it difficult to secure work or get public assistance.

The women Sanctuary serves, Shugrue dos Santos said, "are not poor as a consequence of domestic violence. Generally, they have always been poor."

Sanctuary's "My Door" after-shelter program helps women who are unemployed, or underpaid, to find jobs. However, clients need recovery time before they can take steps to start working. "They are women, people of color. They are facing classism, anti-immigrationism. …They suffer self-esteem problems: No one ever asked these women what they wanted to do when they grew up, what they were good at,” Shugrue dos Santos said.Approximately 46 percent of the survivors who complete the My Door program are currently employed, Shugrue dos Santos says.

Despite the advances, advocates say that society still needs to confront the magnitude of domestic violence. "Domestic violence is not a private family matter. It is a global human rights violation," said Marcia Pappas, president of the National Organization for Women -New York State.

According to state law, domestic violence is a "family offense," but Pappas believes it should be treated as a "hate crime." “Misogynism, sexism is no different from other isms, like racism and anti-Semitism. It is ingrained in society."

Society still does not take it seriously enough, Pappas said. She said she had recently read in the Albany Times Union, about a man that was sentenced to three and a half to seven and a half years in prison for stabbing a horse. That's more time than men get who do the same thing to their wives."

Illegally Divided Homes Pose Dangers but Fill a Need

Image by YH Huang

Three people were killed and four were injured in a firethat started in the basement of an illegally subdivided house in Queens early on the morning of Nov. 7. The basement reportedly had been split into four bedrooms and the second floor divided into two apartments.

The changes almost certainly contributed to the deadlines of the blaze, An obstructed basement door kept firefighters from reaching the victims, forcing them to cut through bars on the window The crowding made escape difficult for those caught inside, and to make matters worse, the smoke detectors did not work.

The accidents once again focused attention on thousands of illegal -- and dangerous -- homes in the city. While some people simply want to see such houses padlocked, other say that that would leave many poor New Yorkers, newly arrived immigrants and students with no place to live in this high-rent city.

"The argument that these accessory dwellings should not be fined because they provide affordable housing for a lot of people is a wonderful argument before the fire. After the fire the city is blamed for it," said Dan Andrew, press spokesman for Queens Borough President Helen Marshal. "The goal is not to put people out in the snow. We want to put these people in safer, better housing."

The question confronting city policymakers is how to do that.

Cramped Quarters

Illegal units have been around since the 1940s when owners opened their doors to returning World War II veterans. But the homes first got negative public attention in the 1990s after a series of fires occurred in Queens.

Today, most of the illegal residences are one and two family homes whose owners have reconstructed cellars and basements to rent out. Cellars, which have more than half of their height below curb level, cannot be legal apartments under city regulations. Owners also carve out illegal single-room occupancy residences by partitioning bedrooms on upper floors.

This "housing underground," as Chhaya Community Development Corp., a nonprofit housing advocacy and economic development and justice organization, calls it, has mushroomed in predominantly middle-class residential neighborhoods of Queens. These neighborhoods attract immigrants seeking a new start. Many feel fairly comfortable because they already house people from their home countries.

Property owners created more than 114,000 illegal so-called "accessory dwellings" between 1990 and 2000, accounting for about 50 percent of apartments produced in the city during that period. In Queens roughly 48,000 illegal units were built, representing 73 percent of all housing constructed in the borough during that decade, according to the Pratt Center for Community Development, a university based advocacy, planning, the actual number of such residences is almost certainly higher.

While the divided houses often violate fire and other safety ordinances and zoning regulations, they offer many New Yorkers their only source of affordable housing. The city has an apartment vacancy rate of less than 3 percent, according to the latest Housing and Vacancy Survey. Under state law, anything below 5 per cent constitutes a housing emergency.

In addition to recent immigrants, the divided buildings house college students and provide a lifeline for low-income people as well as New Yorkers hard-hit by the recession.

The foreclosure crisis has spurred more of these divided homes. The illegal apartments provide steady rental income to homeowners who cannot otherwise meet their mortgage payments.

A Strain on Communities

But while the divided dwellings fill a need, the units clearly pose serious dangers, most notably to the people who live in them. Many basements and cellars have only one exit, limiting means of escape in an emergency. Exposed and overloaded electrical wiring create an increased risk of fire, as do the portable accessory heaters and hot plates that many tenants use.

Neighbors express irritation about the population explosion on their streets. Complaints to the city's Department of Buildings, its 311 non-emergency hotline and community boards have phones ringing off the hook. These "overstuffed units," to use Chhaya's term, have put a strain and drain on city resources and services, community spokespeople say. In some neighborhoods they contribute to overcrowding at schools and hospitals.

"The result is that a lot of people who grew up here are moving to Long Island, or upstate, or out of state. They say, 'That's it. I'm done. I've had it. It's not worth it. I'm leaving,'" said Wendy Bowne, president of the Richmond Hill Block Association.

In Fresh Meadows and Jamaica Estates, the issue is college students, who rent out upper floor of houses from absentee landlords, according to Marie Adam-Ovide, district manager of http://www.queenscb8.org/ Community Board 8. "We have a weekend, 11 p.m. to 2 a.m. problem," she said. That's when college students' parties spill over into the front yard. ? We have an underage drinking problem," Adam-Ovide said.

In Community Board 10, "about 40 per cent" of complaints are about illegal conversions, estimates chairperson Elizabeth Braton. "Most are cellars," she said. "Cellars are never legal."

The City's Approach

Following the deadly fire in Queens, the city stepped up its efforts to educate people about the dangers of illegal conversions. The buildings department and the fire department have been distributing tens of thousands of leaflets in a number of languages warning people that such homes can turn into deathtraps in the event of a fire.

Building Department inspectors are the front line in the city's fight against illegal conversions. When the city receives a complaint, sends the inspectors to check out the situation. But politicians and community and housing groups say the complaint-based system is punitive, inefficient and lacks sufficient enforcement mechanisms.

The inspectors, however, often cannot get access to the property. According to an audit of the Queens division of the Department of Buildings by New York City Comptroller William Thompson, Jr., inspectors with Queens Quality of Life Unit responded to 8,345 complaints of illegal conversions in fiscal year 2008. They could not gain access on the first time around to 3,279, or 39 percent of the locations.

If inspectors do not get access the first time, they return. Then, if they still are not admitted, they can either drop the case or issue a warrant. Thompson found warrants were issued to less than 1 percent of the illegally converted properties. Throughout all five boroughs, the city has obtained 107 warrants - only about 13 a year -- since 2002, the Daily News has reported.

The Mayor's Management Report, however, paints a somewhat different picture. It said that during fiscal year 2009, the buildings department received 23,326 complaints about illegal conversions of residential space. Inspectors managed to gain access to 49 percent of those locations and "issued violations to property owners in 16 percent of these cases."

In the case of the Queens fire, the city sent investigators to the building in response to complaints in 1990 and 2004. Both times, the inspectors found no violations, Tony Sclafani, a building department spokesman told the New York Times.

Units that are inspected and found to be illegal receive a notice of violation. If the owners do not make the necessary repairs, they are fined and fined again. The fines for repeated violations can reach $15,000. But the fines are rarely paid.

If the inspector deems there is imminent danger to the occupants, a vacate order is filed. According to Thompson?s audit, the buildings department did not follow up on 657 vacate orders in Queens that were issued in fiscal year 2008.

Sclafani has said the city evacuated 1,086 illegally converted apartments in 2008. After the Nov. 7 fire, the Times reported, inspectors found eight rooms next door and evacuated all of them.

Closed Doors

Thompson and Queens Borough President Helen Marshall say the city needs more inspectors. But more inspectors do not mean more access.

"Without a permit they can?t do much," said Bownes. She said that when Rudolph Giuliani was mayor, people from the fire and police departments accompanied the inspectors. Now, she says the homeowners "laugh in the face of the Department of Buildings."

"Maybe if the Department of Buildings were able to enforce the law, word would get out and people would not buy over their means, would not resort to making illegal apartments," Bowne says.

"When the inspector comes, the kids just don't open the door," Adam Ovide said. She said she has seen only one successfully conducted inspection in her two and a half years working for the community board. That building, she said, "was just terribly dirty and unkempt. The yard was full of weeds."

But Mary Ann Carrey said the situation has "improved greatly" over the more than 20 years she has been district manager of Community Board 9.

She said that, in an average month, she gets seven or eight complaints. Her staff goes with the inspectors who usually get access to the building. Still, she said, "enforcing the system is a problem. ? Complaints are so low priority that the courts seldom hear the case."

Even if the hazardous condition in the home can be removed, the problem has not been solved, Carrey said. "If you have three families living in a zone for one or two families in a home, then you?ve got a problem. You cannot just change the zoning code. So what do you do then? I remember Koch saying back when he was mayor, 'What do we do after we evict them? Where are we going to put these people?'"

Looking for Answers.

That is the issue Chhaya hopes to confront. The current complaint system "is not working," said Seema Agnani, the group's managing director of Chhaya. "Penalizing owners has little impact on the housing ground. ? Moreover the complaint system pits neighbor against neighbor, causes discord and distrust."

Chhaya, whose name means shelter, focuses on improving housing opportunities in New York for South Asians and other immigrants. In a survey of homes in Jackson Heights and Briarwood/Jamaica, Chhaya estimates that about a third had an "accessory unit" that could be "potentially legalized."

To accomplish this, Chhaya envisions a pilot program to create a new category of residence, the "Accessory Dwelling Unit" in the city's building code. A panel of expert architects, engineers and planners could determine how these rooms and apartment could meet fire, safety and health rules. Education program in several different languages, offered through private and nonprofit partnerships, would teach homeowners and new homebuyers the city's ordinances and rental laws.

Owners who voluntarily comply with the process and fix their residences to comply with standards for the new accessory units would receive financial assistance from the city and be given a grace period of 12 to 18 months, during which time they would not be fined. "Currently, owners do not have enough of an incentive. "It can take $10,000 to $15,000 to legalize the dwelling. It can take a year," Agnani said.

After the completion of the reconstruction, the owner would receive a certificate of residential status.

In addition, be a community task force would access the impact of increased population density on neighborhoods. "Public resources are allocated based on population. If you bring these units into regulation, if you account for them, the city can allocate more resources for sanitation, can better accommodate overcrowded schools," Agnani says.

Bowne says she refers renters and owners to Chhaya. "They educate people who do not know the law," she said. But, she has doubts about whether the group's proposal will address her community's concerns.

Bottom line, she said, "The illegal conversions are exhausting our city services."

New Efforts Fail to Reduce Homelessness

As Mayor Michael Bloomberg approached the end of his first term in 2004 with his eye toward re-election in 2005, the administration was able to momentarily turn away from the city’s economic turmoil. Bloomberg began re-examining some of New York’s social service policies, putting fighting poverty and homelessness at the top of his list.

In June 2004, Bloomberg announced an ambitious five-year plancalled "Uniting for Solutions Beyond Shelter" with the goal of tackling the complex questions of homelessness -- particularly ending chronic homelessness within 10 years -- and cutting the homeless population by two-thirds. "At its heart, this new plan aims to replace the city's over-reliance on shelter with innovative, cost-effective interventions that solve homelessness -- and to make visible headway in reducing homelessness on the streets and in shelters," said the mayor.

To be sure, there have been bumps along the way: controversial moves offering homeless individuals one-way tickets out-of-town or enforcing a never utilized Pataki-era state law charging homeless families for their shelter stay. There also was an extremely unpopular attempt to move a Manhattan intake shelter to Brooklyn. And, at a recent Working Families Party mayoral forum, media reports quoted Bloomberg as saying New York's homeless find shelters "a lot more attractive" than "permanent living situations."

But more significantly, Bloomberg’s lofty goals have not materialized. In fact, rather than cutting the population by two-thirds, the administration has seen homelessness increase substantially.

A Rising Population

According to the Coalition for the Homeless, the city's homeless shelter population has increased by 65 percent between 1998 to April 2007. Earlier this month, the coalition released revised numbers revealing the homeless shelter population reached its highest level ever at the end of September 2009. It reported "39,000 homeless New Yorkers -- including 10,000 homeless families, an all time high -- sleep in municipal shelters every night." It also found since Bloomberg took office, 45 percent more New Yorkers are in shelters every night.

These updated numbers detailed that in August "an all-time record 1,914 new homeless families entered the shelter system, and the past year has seen the largest number of new homeless families entering shelters since modern homelessness began."

Moreover, the coalition found the number of homeless New Yorkers sleeping in city shelters in fiscal year 2009 was "10 percent higher than the previous fiscal year, and 45 percent higher than fiscal year 2002, when Mayor Bloomberg took office." This data includes more than 16,500 children sleeping in shelters, a 12 percent increase since last year.

The city sees some successes in its fight to end homelessness. In its recently released Mayor's Management Report, it noted that the number of single adults in a shelter on an average day has dropped from 8,474 in 2005 to 6,526 in fiscal year 2009 and attributed some of the drop to shorter shelter stays.

The city also says it has kept many people from becoming homeless stating, "More than 90 percent of families and adults receiving prevention services did not enter the [Department of Homeless Services] shelter system." However, even by the administration's own figures, the average number of families with children in shelters has increased steadily since fiscal year 2006. In fiscal 2009, 12,959 families with children entered the shelter system, a 61 percent rise from 2005.

But its homeless policies continue to attract criticism. Chastising the mayor for thinking some people "would choose to live in a homeless shelter over permanent housing," Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum said in a statement, "Because the administration doesn’t understand the problems facing homeless New Yorkers, its policies fail to present real solutions. Policies should be reevaluated to respond to the worsening economy, the scarcity of jobs and affordable housing, and the reality that recent strategies have not been working."

The City's Tactics

In its effort to fight homelessness, the administration adopted what its Web site describes as "a first-ever effort to bring together the public, nonprofit, and business sectors in a coordinated campaign to address homelessness."

The plan was multi-faceted and integrated a myriad of city agencies. It has included an expansion of community-based homelessness prevention programs, a centralized database to better track the homeless, and ways to redirect funding and priority into prevention and away from the shelter system. It set stricter eligibility requirements, a redesigned intake process, shorter shelter stays and the creation of more supportive housing.

Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs, former commissioner for the Department of Homeless Services and one of the advisors who helped create the new approach, said what was really innovative was that the city "flipped the paradigm." Traditionally, once someone enters "a shelter, your [other] needs are met, and then we figure out housing." Now, Gibbs said, the priority is being placed on housing needs, followed by other support services.

Patrick Markee, senior policy analyst with the coalition, though, said the administration has made mistakes from the start. While the faltering economy accounts for some of the increase in homelessness, Markee also attributes the surge to a 2005 decision by city officials to stop giving homeless families priority for federal Section 8 housing vouchers and apartments in public housing.

"From the days of Mayor Ed Koch," Markee said, "the neediest have always received a portion" of these programs. Now, non-homeless poor families receive all the priority. "It's not that they are undeserving of housing [assistance] -- there's now just anti-homeless discrimination," Markee said.

Gibbs said the administration made this shift because the supply of vouchers and public housing "is insufficient to meet the demand from the shelter system," and so it opted to give preference to "disadvantaged lower-income people." To deal with homelessness, she said, the city decided to focus "on preventive [programs] versus re-housing."

Changing Programs

In 2005, the city introduced a housing assistance plan called Housing Stability Plus, which was authorized by New York State. Gibbs said in a recent interview that the plan was "not as attractive as Section 8, where the voucher is less time-limited," but there was a shortage of Section 8 vouchers during the Bush administration when housing assistance was perennially on the chopping block.

"Housing Stability Plus," Gibbs said, "was tied to the case of a family and to receiving money and welfare... and freed up Section 8 for other community needs." Housing aid for a family decreased in value by 20 percent each year and assistance ran out after five years.

The program was "initially successful” according to Gibbs. However, the administration abandoned it two and a half years later because, Markee said, it was "a failure…and deeply flawed." The city replaced it in 2007 with Advantage New York/Work Advantage, a rent-subsidy program for homeless families that required them to work at least 20 hours a week.

Robert Hess, commissioner of Homeless Services described it in an email as, "the most generous municipal rental assistance program in the nation." According to Hess, over 13,000 leases for permanent housing have been signed under the program. "Each week 131 families sign Advantage leases, an increase of 52 percent over Housing Stability Plus levels and 79 percent over Section 8,” he said. This subsidy lasts for only two years.

Both Gibbs and Hess described how Advantage New York "incentivizes" participants, to create savings accounts and to work. The city matches dollar-for-dollar up to $250 a month in a bank account to strengthen "asset development strategy, banking skills and rewards for savings." Gibbs also said the plan gets beneficiaries "in the habit of contact with a landlord." In addition, Hess said, the program "enhances landlord participation and creates options to serve a broader population. Most importantly, it focuses on quickly returning families to their communities.”

Markee, though, disputes the administration's claims of success. What is especially galling, he said, is that there is no evidence that time-limited rent subsidies are effective, but the administration continues to use them to replace other, proven programs. The city, he charged, wants change for the sake of change. It is, he said, preoccupied with the "fetish of the new."

Markee also expressed concerns over the short time limit, noting that work advantage vouchers are expiring this year for approximately 2,000 formerly homeless families. The city "has never addressed" what will happen to these people, Markee said.

Homeless Services also invested in HomeBase, a homeless prevention pilot program that has since gone citywide. Its budget increased by 22 percent in fiscal year 2010; its client service levels increased by more than 10 percent in the first quarter of fiscal year 2010; and funding for anti-eviction services was raised by 16 percent, all according to an agency spokesperson.

The administration should not take the credit for that, though, Markee said. In an email, he wrote, "Bloomberg and City Council adopted a budget cut of $150,000 from the homelessness prevention fund," for fiscal year 2009. Bloomberg, he said, "also proposed major cutbacks to eviction prevention legal services," but the City Council restored those.

For fiscal year 2010, which began in July, Bloomberg initially called for a cut of $5 million for HomeBase prevention offices, according to Markee, but federal stimulus money then provided approximately $74 million for homelessness prevention in New York City over three years.

No Room at the Shelter?

As the cold weather approaches, capacity at shelters has also raised red flags. Another Coalition for the Homeless report claimed the city has virtually run out of space, especially for homeless single adults. It noted, "the number of homeless single adults... this year has increased by more than 7 percent -- the largest one-year increase since the 2001 economic recession." The coalition discovered on the night of Sept. 30 only two available shelter beds for homeless men and eight for women.

Gibbs described this as normal: “Capacity is always at 99 percent… and the single numbers always go up in winter; [These are] tried and true projections.”

Bloomberg pledged to construct about 12,000 units of supportive housing across the city. These would address the needs of various people, including substance abusers and domestic violence victims, Gibbs said.

Many units are currently in the works. There is "a major dent made to move the chronically homeless" from the streets and shelters, in part by learning more about, as Gibbs put it, "the who, where, their history … tracking [and] understanding their needs."

However, the coalition said, supply continues to lag behind demand. "More than half of the newly-constructed supportive housing -- 3,276 units of the planned 6,250 new units -- will not be built until at least 2011," a coalition reportsaid. That’s a different timeline than the one set out by Bloomberg, which applies until 2016.

Hess, though, said the city is prepared for future demand. "We function somewhat like an accordion, expanding and contracting as needed, so that our system does not keep space open unnecessarily at the taxpayers' expense and minimizes impact on communities, while at the same time, being ready at any moment to meet need," he wrote in a email.

Underlying all the specifics for many homeless advocates lies a question of philosophy. "One of the major reasons the Bloomberg administration gave for changing the old system of giving homeless families preference for some housing program was that it acted as a perverse incentive for families to go into the shelter system. Even without the priorities, family homelessness has escalated, suggesting either that the homelessness is driven by housing market and economic pressures pushing families out, not by perverse incentives. The priorities should be restored,” said Victor Bach, director of housing research at the Community Service Society.

With an eye on those economic pressures, Brooklyn College sociology professor Alex Vitale said in an email that the city needs to "step up and reinsert itself into housing markets through new construction of affordable housing... The amount we spend to [house] homeless families in the emergency system... is a misuse of resources that could be put into permanent affordable housing if government would embrace the reality of the current market failure and quit trying to work with for-profit landlords and developers.”

The administration often points to its record of creating new housing. Whatever its successes, though, more demand clearly exists, leaving some New Yorkers with no place to live.

Jillian Jonas is a freelance journalist focusing on local and national politics, government and public policy. She is a former national political analyst for U.P.I.

Affordable Housing Not Included

This is the first in a series, to run between now and Election Day, examining Mayor Michael Bloomberg's record in key areas.

Judy Stein has lived in New York City all of her life, and in Williamsburg for a third of it.

She spent most of her time there in a one-and-a-half bedroom apartment on Bedford Avenue above the street's 60-year-old print shop -- once owned by her former roommate and confidante.

That shop is now about to become a cell phone store. Stein at age 63 is now homebound, stuck in a wheelchair after her left leg was amputated last year. And last week, her attorney was headed to housing court to battle an order of eviction for the third time.

Stein used to pay $550 a month in rent. The building's new owner wants closer to $2,100, she said. She brings in $9,000 a year in social security and disability.

"They don't want this to be a neighborhood," said Stein, sitting in her yellow and blue kitchen last week. "All of these people that are buying these buildings... they don't live here. They don't care about what's going to happen to this neighborhood," she said, slamming her hand against the kitchen table. "All they are interested in is this." Stein rubbed the tips of her fingers together. "The money," she said.

Stein's story is familiar to tenants across the city. As gentrification and the now-busted housing market fueled astronomical rents and luxury development, some lower-income New Yorkers (just call them "poverty people," said Stein) have been left with fewer housing options.

Almost five years ago, the Bloomberg administration came up with several solutions. One of them was to rezone scores of communities, Williamsburg included, across the city and provide financial incentives to developers to build permanent affordable housing -- otherwise known as inclusionary zoning.

The problem, some advocates and experts say, is that it isn't meeting expectations.

A review of the units created by this type of financial incentive shows that the administration is not close to hitting its goal. And given the economy, it is unlikely to anytime soon. What a spokesman from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development calls a "key piece" of the administration's affordable housing agenda has to many advocates, officials and experts been disappointing. The city disagrees, saying the program already has created thousands of units, despite being temporarily set back by the crippled housing market.

For their part, advocates and experts wonder how the mayor's free market driven development and affordable housing policies will fare now that the boom has gone bust.

It's Not Just Luxury

View NYC Inclusionary Housing sites in a larger map, Purple markers are completed inclusionary housing projects, yellow markers represent housing projects that have been closed and financed.

Nowhere was the mayor's inclusionary housing program predicted to take off more than in Williamsburg.

The beacon of the newly expanded program, which had once applied only to skyscraper-saturated areas of Manhattan, the massive Greenpoint-Williamsburg rezoning has produced 768 affordable rental apartments since 2005. According to the Department of City Planning, the city had hoped for more than 2,200 over the course of a decade. About 20 percent of the units that have been built or are now under construction are renovations of existing affordable apartments, according to the Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

Back in 2005, the administration said the rezonings already approved -- like Hudson Yards and Greenpoint-Williamsburg -- would alone create 6,000 units of affordable housing thanks to inclusionary zoning.

Nearly five years later and with more than a dozen new neighborhoods under the program, less than half that number have been preserved or built during Bloomberg's first two terms. A vast majority of those apartments, 1,786 of the total 2,716, are in Manhattan, according to the Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

Some of these developments were projected to create affordable housing over an extended time period. Even taking those deadlines into account, they are behind schedule.

Inclusionary zoning gives developers the option to increase a project's total floor to area ratio by 33 percent if it designates 20 percent of all the apartments as affordable housing. Up until this year, it applied exclusively to rentals. That bonus could mean seven additional stories for a 23-story building. In addition, the affordable apartments can be financed with public subsidies. They can also be located on the same site as the rest of the project or within the same community district.

For most projects, tenants must make less than 80 percent of the area median income -- $61,920 for a family of four. Portions of some projects, like Hudson Yards or West Chelsea, can opt for higher brackets, between $96,750 and $135,450 for a family of four, and still receive subsidies and the density bonus.

These incentives were supposed to make the voluntary construction of affordable housing economically feasible for developers. And for communities, the promise of these affordable units was seen as compensation for high-density luxury development in their midst.

Since 2005, the administration has extended inclusionary zoning to 20 neighborhoods -- including the Bronx's Lower Concourse, Brooklyn's Flatbush and Queen's Dutch Kills. So far, in more than half of them (some of which were approved in 2009 and 2008) developers haven't taken the bait.

In Brooklyn's South Slope, only six units have been a part of the program since it was rezoned in 2005. In Maspeth and Woodside, which was rezoned in 2006, there has been nary a unit.

Or take East Harlem, which was included in the massive 125th Street rezoning approved in April 2008 -- just as the market started to reel. According to the Community Board 11 Chair Robert Rodriguez, affordable units from inclusionary zoning are not on the map.

"The simple answer is no, we haven't seen any development in the areas that were rezoned," said Rodriguez. "It's hard to tell the free market what they can and cannot do."

According to the housing department, 37 units are under construction in that community district.

Those in the real estate industry say the city shouldn't expect to see any increase in these numbers soon.

"A lot of stuff out here is stalled," said David Maundrell, the president and founder of aptsandlofts.com, a real estate marketing firm that specializes in Williamsburg. Maundrell just saw a more than 400-unit development fall through, a portion of which would have been inclusionary housing. The developer, he said, couldn't get financing. "People aren't building."

Opting Out

According to Eric Bederman, a spokesman for the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, inclusionary housing will work -- eventually.

"While the current economic climate has slowed the development of market-rate housing, inclusionary zoning was put in place as a forward thinking initiative to ensure that affordable housing can still be created during the strongest housing markets, when it is historically more difficult to do so," Bederman said in an e-mail. "The good news is that even in a time when we're seeing drops in housing starts and new construction, the city still has projects being developed through the mayor's inclusionary zoning plan."

Officials tout projects like Williamsburg's Edge, which will bring 346 affordable units to North 6th Street, or its neighbor, Toll Brothers' Northside Piers, which provides 263 units within a half-mile of its waterfront Williamsburg towers. These have been Northern Brooklyn's largest success stories so far.

Simultaneously, housing advocates and policy experts claim the inclusionary zoning program was flawed from the start.

"I think there is some Peter principle for public policy that anything that is a good idea on a small scale will inevitably be expanded and pushed to a much larger scale so it no longer works," said Julia Vitullo-Martin, the director the Regional Plan Association's new Center for Urban Innovation. "I think inclusionary zoning is in that category."

Nationally, the program has had its ups and downs. According to a report from the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, inclusionary zoning created more than 15,000 affordable units as of 2003 in the Washington D.C. area. But in suburban Boston, where 43 percent of the jurisdictions had adopted inclusionary zoning as of 2004, there were no affordable homes at all.

Vicki Been of the Furman Center says traditionally the most flexible inclusionary housing programs -- the ones that give developers multiple options, such as a density bonuses or tax incentives -- have been the most successful.

But some advocates disagree. They claim if inclusionary housing was mandatory, then the city would finally have a steady stream of affordable units with every project.

"It hasn't generated the number that people thought it would, partly because the subsidies weren't deep enough," said Adam Friedman, the director of the Pratt Center for Community Development. "Now that the market is in the doldrums, it's time to look at mandatory inclusionary zoning."

Recently, the city has retooled the program to include a home ownership option, which it hopes will encourage more developers to participate in the program.

A New, New Housing Plan

Inclusionary zoning is just a sliver of the Bloomberg administration's housing plan, and it alone can't solve the city's housing drought.

So, enter the Bloomberg administration's larger affordable housing program, dubbed the "New Housing Marketplace Plan." Its goal: to create and preserve 165,000 units of affordable housing in a decade. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development says it has created or preserved 94,000 affordable homes so far -- more than half of that number have been reconstructed and rehabilitated apartments, not new construction.

But that housing plan, which includes preserving affordable housing stock and finding new land for affordable units in addition to inclusionary zoning, is facing a far different economy than when it was first proposed.

In front of a packed audience at the New School late last month, the department's new Commissioner Rafael E. Cestero explained the approach.

"The reality is that many of these neighborhoods have had a hard time supporting those kinds of developments and many of those developments are in trouble," said Cestero of the large luxury condominium developments now stalled across the city. "Faced with the current economic realities, we must and are examining every element of the plan, every new market-driven innovation in front of us and looking at the way forward with a different lens and a different focus."

With that in mind, the department (borrowing from the campaign slogans of the mayor's Democratic competitors), will look at every project through a "neighborhood lens," said Cestero. Some of that, he added, would include turning failed luxury condominiums into affordable housing as well as reclaiming apartments taken off of rent stabilization rolls during the booming market.

Advocates, though, aren't applauding yet. They say much of the Bloomberg administration's housing policy has focused on getting private developers to create new housing -- not on trying to preserve the existing stock. For instance, between 2005 and 2008, according to the city's most recent housing survey, about 20,000 rent stabilized units, or 2 percent of the entire stabilized stock, were lost to the market. Focusing on rent stabilization reform and rent control -- as proposed by City Council Speaker Christine Quinn -- is the real solution, they say.

"The priorities that Bloomberg has put on development of new construction as a solution to affordable housing has been the wrong emphasis," said Mario Mazzoni, the lead organizer at the Metropolitan Council on Housing. "You cannot build yourself out of the affordable housing crisis in New York City."

Another Four Years

In Williamsburg, Stein was never optimistic about the neighborhood's waterfront development. She knew she would never be able to live there.

"My grandparents came here as little kids. They worked. My parents were born here. My family had a business. We owned a house. Things were looking so nice," recalled Stein. "And now, you know, my mother is 91 and is living in a nursing home in Pennsylvania. Maybe I'll have to go live with her."

Stein could be just one more New Yorker displaced by the city's affordable housing shortage.

There is no question that luxury development and the city's changing landscape have been hallmarks of Bloomberg's tenure at City Hall. But given the drastic change in the economic climate, advocates and experts are waiting to see, if Bloomberg is re-elected, how he will adapt.

"OK, he had two pretty good terms on this issue, and now all the problems are coming home to roost and the future looks grim," said the Regional Plan Association's Vitullo-Martin. "In a way the question is what is he going to do next."

Homes, including Judy Stein's, hang in the balance.

Housing Project Splits Bushwick District

Photo by Dana Farrington

Politics are personal in Brooklyn's 34th City Council District. Candidate Maritza Davila, a local community organizer, is running with the help of the Brooklyn Democratic leader, Assemblymember Vito Lopez, who was once a mentor and supporter of the incumbent councilmember, Diana Reyna. The third Democratic hopeful, Gerry Esposito, is hoping that the relationships he's built during his 32 years as district manager for Community Board 1 will help him break away from the pack.

District 34 encompasses Bushwick, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Ridgewood and Williamsburg. This predominantly low-income, Hispanic area has confronted the candidates with questions surrounding affordable housing, new development, job security and the general safety of its residents. A dispute over a proposed housing complex in a neighboring district has played a central role in the campaign.

Thanks to the extension of term limits that she helped pass, Reyna is now running her third campaign for the position. So far, the third time clearly has not been a charm.

"There certainly is a different component in the sense where, you know, my mentor, who at one point was supporting me, is now not supporting me -- but even further than that is supporting a candidate to run against me," said Reyna. But, she added, "I don't think we've allowed it to affect us." Instead, she said, the campaign has remained focused on the services it wants to provide to the community.

Nonprofits and Politics

Photo by Dana Farrington

Diana Reyna

This is a district where non-profit community based organizations have become entwined in politics. In the 2007 book, Bargaining for Brooklyn, sociologist Nicole Marwell, a professor at the Baruch College School of Public Affairs, explains what she refers to as "voter education," where politicians help secure government funding for specific groups and then "educate" the population -- the voters -- about the politician's role. The Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizens Council, founded by Lopez, played an integral part in Marwell's research.

The senior council has played a key role in devising a plan for affordable housing on the Brooklyn Triangle in District 33 and also has been selected by the Bloomberg administration to develop the property. Davila has worked with the council since 1993.

The plans calls for building 1,895 apartments in low-rise buildings on the Broadway Triangle, a 31-acre plot bordered by Broadway, Union Street and Flushing Avenue. The plan requires City Council approval.

Supporters say the housing is needed. Reyna, though, has opposed the project. She said the project goes against the wishes of a number of community organizations and described her opposition as a way of standing up for various "voiceless" community groups and nonprofits that have not been included in developing the plan.

The Broadway Triangle Community Coalition has emerged as an opposing force as well. Though not against affordable housing, the coalition includes over 40 religious and community organizations that seek to open up the planning process to more groups.

The city awarded no-bid contracts for the project to the Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizen's Council and the United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg. On its website United Jewish Organizations describes itself as having a "well-established partnership" with the senior citizen's council.

Reyna said the Broadway Triangle has affected her City Council race. "I would say it has to do everything with the election. It speaks to the leadership as to who is going to be representing this constituency," she said. "Anybody who supports this plan will be turning their back on the community of the 34th district because it doesn't matter whether it's inside our outside the community district, the point is it's part of the community and whatever's built there we should have access to it."

Davila could not be reached for comment.

As district manager of the community board that oversees the area, Esposito approved the plan with stipulations.

Photo by Dana Farrington

Gerry Esposito

"The community board reviewed what was placed before us for property that was -- lest we not forget it has been empty for decades, alright -- and we saw the possibility of bringing affordable housing into the community, and the community board accepted it with conditions," said Esposito.

Despite his involvement, Esposito tried to distance himself from the controversy.

"I think people are familiar with my positions as district manager for the Community Board for the past 32 years, and they know that I'm a fair and honest person, and I want to bring fairness and honesty to the City Council," he said. "I want to bring government back to the people."

In general, Esposito is wary of links between nonprofit work with politics. "I think they [community based organization] are very important... Oftentimes they provide services where the city is void," he said. "However, I think they need to stay one million percent clear of the political process."

Lining Up Support

A sign for Davila hangs in the window of a local Internet spot on a corner along Wyckoff Avenue in Bushwick. The business is about a block away from Davila's campaign headquarters at the Bushwick Democratic Club, founded by Lopez. Victor Borja owns the business that proudly displays Davila's smiling face. Wearing a Mexican soccer jersey and shorts, Borja explained his reason for supporting Davila.

Photo by Dana Farrington

"Because we know her, because she has chatted with us, even if they're get-togethers, she's here in the area," he said in Spanish. Borja later added, "We hope she wins, and all of us Hispanics in this area are going to vote for her, including me."

Approximately 60 percent of the district's residents are Hispanic. Davila, born in Puerto Rico, is the only one of the three, born outside of New York. Reyna is the first woman of Dominican descent on the City Council, and Esposito's grandparents emigrated from Argentina in the early 1900s.

Just a few blocks away on the last Sunday in August, a handful of local community-based organizations gathered in MarĂa Hernandez Park with Reyna's blessing for a back-to-school event co-organized by her liaison Francisco Mercado.

Local resident Gwen Schantz handed out fliers and free food to families in the park. Schantz, 28, is the founder of the Bushwick Food Co-op, a group organizing to open a storefront food co-op in the area. Schantz has decided to vote for Reyna on Sept. 15.

"For the food co-op, she has been very supportive of our plan, and she's given us advice with regards to how we should reach out to the community," said Schantz. She later admitted that she did not know "very much" about the other candidates, but said she "just lean[ed] in the direction of Diana Reyna because I like what she's done thus far."

Representing the District

As for Esposito, he consistently refers to his experience as district manager and his lifelong familiarity with Williamsburg as having prepared him for the job of councilmember. Esposito has worked closely with small businesses and their owners during his time on the Community Board and said he hoped to strengthen and not strain small businesses during financially difficult times. In terms of organizations providing services to the community, Esposito pointed to the need to "think outside the box."

"You can't just throw money at issues. You have to make sure that money is going appropriately to solve the problem so it will address the issue," he said.

Reyna said Esposito had done a "great job" in his position, but did not accept that this necessarily qualified him for City Council. The district, Reyna said, includes not one, but three, community boards, and any council member must reconcile the distinct needs of all these communities is unique to her position. In addition, every councilmember has to work with the other 50 members, and Reyna said she already had the "good relationships."

Reyna said her priorities had not changed over the last eight years. Her platform still emphasizes affordable housing, job creation and education.

Davila, whose website feature a picture of her with Lopez, says on the site she will work for rezoning for projects that are "100 percent affordable." Her platform offers few specifics. In education, for example, its cites her experience as president of Community School Board 32 and said she " understands the needs that are needed inside of classrooms, that will benefit our children."

Beyond Vito Lopez

For the campaign, Davila has secured not only Lopez's help, but also the endorsement and financial contribution from Local 1199 SEIU and a number of other unions. Plus, she has the Working Families Party at her side, support usually provided to the incumbent.

In an email, party executive director Dan Cantor said, "Maritza Davila knows first-hand how hard New York's working families have to fight in this economic climate for good homes, good schools and good jobs. Her years of experience as a tenants' rights advocate and organizer will make her a strong voice on the City Council."

The New York Times has endorsed Reyna, as has the United Federation of Teachers, Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, who also backs the Triangle Project and U.S. Rep. Nydia Velazquez. The New York League of Conservation Voters and the Greenpoint Star have endorsed Esposito.

As of the Sept. 4 filing deadline, Reyna had raised $84,414 in private funds and $84,122 in public funds. Davila had received $88,127 in private funds, with $84,122 matched by public funds. Esposito raised $91,424, mostly from a number of private local businesses and $73,028 in public funding. He has spent the most money thus far on the campaign and Reyna has spent the least.

The Democrat elected in the Sept. 15 primary will face Republican candidate Jacqueline Haro in November.

Housing Bias Persists, Fueled by the Internet

Photo (cc) travelertish

It's been some 40 years since the federal Fair Housing Act was passed allowing the Department of Justice to prosecute "patterns or practices" of housing discrimination" and 20 years since that act was amended to permit the department to act against municipalities that violate fair housing standards.

Yet housing discrimination persists in New York, according to the Fair Housing Justice Center, a city-based non-profit fair housing organization. The city's acute shortage of affordable housing combined with the fact that "real estate brokers and agents handle much of the rental market, unlike any other U.S. city" has created an unchecked system riddled with corruption and abuse, said Diane Houk, executive director of the center.

Even though city government has taken some measures to fight this kind of discrimination, fair housing advocates still see the need for better and more flexible enforcement. They say that all levels of government have failed to keep up with rapid technological changes -- like the advent of the Internet to advertise apartments -- to monitor compliance and ensure rules are followed.

Segregated City

The Fair Housing Justice Center's latest data reveals a considerable increase in complaint volume. Since opening in 2005, it has received some 400 allegations of housing discrimination, about 55 of which have led to lawsuits or the filing of agency complaints. The most common complaints registered "involve allegations of discrimination because of a person's disability or source of income discrimination." This kind of discrimination may occur against tenants who lawfully pay rent with money other than earned income, usually in the form of a government subsidy.

Utilizing statistics from the most current census, the Fair Housing Justice Center determined the New York City metropolitan area is the fourth most segregated metropolitan area in the United States for African Americans and the fifth most segregated for Latinos. As recently as this month, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development charged two Queens landlords for denying housing to prospective black tenants in what the landlords described as a "white neighborhood."

The center's findings reflect national indicators. Earlier this spring, the National Fair Housing Alliance issued its annual trends report based on surveys from member organizations and data from state and local governments, and federal agencies such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Justice Department. The alliance concluded 2008 was a peak year for housing discrimination complaints, reaching almost 31,000, an increase of 3,735 since fiscal year 2007. This is the highest total number of complaints ever taken from all reporting agencies.

The increase may have been fueled by the economic downturn and the foreclosure crisis, as people who have lost their homes turn to the rental market. These problems have disproportionately affected minority communities, who face the greatest threat of housing discrimination

Barriers for the Disabled

The disabled find themselves at a particular disadvantage in New York's housing market. A Fair Housing Justice Center 2007 newsletter cited New York City for "substantial non-compliance with … accessibility requirements" for all new multifamily buildings. Federal standards call for accessible common and public areas and sufficient floor space in bathrooms to allow wheelchairs, among other features to accommodate the disabled, but the city, according to the center, has not enforced the rules.

In 2008, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York filed charges against a private development group, Chrystie Venture Partners/Avalon Bay Communities and others, for discrimination against people with disabilities in the design and construction of a building in the East Village, which was built only a few years ago. The developers flaunted the accessibility rules even though the building was constructed on one of the city's last remaining large plots of land and in conjunction with the city's Department of Housing, Preservation and Development.

The Council Acts

In 2008, City Council targeted a different kind of discrimination as it moved to protect people who receive housing vouchers, disability payments or other types of government assistance to help pay their rent. The legislation bars landlords from refusing a person's eligibility to let an apartment because of an income source.

The Bloomberg administration and the city's Commission on Human Rights, designated to enforce the measure, opposed the bill. Council then overrode Mayor Bloomberg's veto.

Patricia Gatling, chair of the Commission on Human Rights, explained the administration opposed the measure as a matter of semantics more than substance. There was, she said, "concern over the wording and who would be most affected by it, particularly in the case of small landlords where it would not be cost-effective for them to retrofit their units" to be able to rent to someone receiving disability payments.

Now that the law has gone into effect, Gatling enthused, it "has been really effective." Of the almost 1,000 cases a year the human rights commission reviews, about 20 percent now relate to source of income housing complaints. The law, she said, has been especially beneficial for long-term tenants receiving subsidies. "We're seeing cases [dating] from the Koch administration," Gatling said. "People can use vouchers now who couldn't before."

Discriminating On Line

In addition to lax government enforcement -- particularly on the federal level -- fair housing advocates say a key culprit in illegal behavior has been Internet advertisements and postings on list services.

"Internet advertising is becoming more and more important in how people look for housing, especially apartments to rent, so even if a few illegal ads are posted, this discourages renters from contacting the landlords and gives the impression that it is legal for a landlord to refuse to rent to a family with children, for example," explained Houk in an e-mail.

The Fair Housing Justice Center conducted its own analysis of apartment postings on one such service, Craig's List, over several days during 2008 to monitor compliance with fair housing procedures. The study, "No License to Discriminate," found countless examples of apartment listings with "conditions" --many of them placed by licensed real estate brokers who should know better. Examples ranged from limiting family size to phrases such as "no government programs."

Focusing just on July 2008, the center also examined income source violations specifically. It found New York City brokers violated the new legislation close to 400 times in that one month. Some 161 different reat estate companies put up the illegal postings.

Houk criticized city government, and the Commission on Human Rights in particular, for a lack of aggressiveness to force compliance. "We are not seeing vigorous enforcement by the commission or other city agencies of this new provision." she said.

Commissioner Gatling vehemently disagreed with this analysis. Since the bill's passage, "there's so much more work." To address that, Gatling said she is considering "sectioning off some attorneys" to work exclusively on housing discrimination/income source cases.

Although Gatling said her staff carefully keeps an eye on Craig's List, she wants the city to adopt a policy mandating that developers who publicize vacant apartments must advertise throughout the mainstream printed media and not just at sites aimed at their targeted demographic. Because more people could be notified about empty units, this would "improve access to new and bigger buildings."