Three people were killed and four were injured in a firethat started in the basement of an illegally subdivided house in Queens early on the morning of Nov. 7. The basement reportedly had been split into four bedrooms and the second floor divided into two apartments.

The changes almost certainly contributed to the deadlines of the blaze, An obstructed basement door kept firefighters from reaching the victims, forcing them to cut through bars on the window The crowding made escape difficult for those caught inside, and to make matters worse, the smoke detectors did not work.

The accidents once again focused attention on thousands of illegal -- and dangerous -- homes in the city. While some people simply want to see such houses padlocked, other say that that would leave many poor New Yorkers, newly arrived immigrants and students with no place to live in this high-rent city.

"The argument that these accessory dwellings should not be fined because they provide affordable housing for a lot of people is a wonderful argument before the fire. After the fire the city is blamed for it," said Dan Andrew, press spokesman for Queens Borough President Helen Marshal. "The goal is not to put people out in the snow. We want to put these people in safer, better housing."

The question confronting city policymakers is how to do that.

Cramped Quarters

Illegal units have been around since the 1940s when owners opened their doors to returning World War II veterans. But the homes first got negative public attention in the 1990s after a series of fires occurred in Queens.

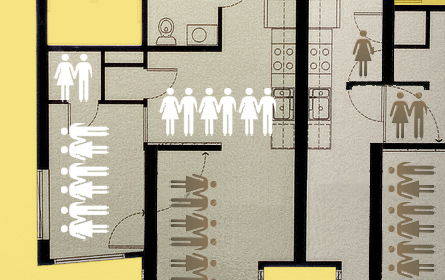

Today, most of the illegal residences are one and two family homes whose owners have reconstructed cellars and basements to rent out. Cellars, which have more than half of their height below curb level, cannot be legal apartments under city regulations. Owners also carve out illegal single-room occupancy residences by partitioning bedrooms on upper floors.

This "housing underground," as Chhaya Community Development Corp., a nonprofit housing advocacy and economic development and justice organization, calls it, has mushroomed in predominantly middle-class residential neighborhoods of Queens. These neighborhoods attract immigrants seeking a new start. Many feel fairly comfortable because they already house people from their home countries.

Property owners created more than 114,000 illegal so-called "accessory dwellings" between 1990 and 2000, accounting for about 50 percent of apartments produced in the city during that period. In Queens roughly 48,000 illegal units were built, representing 73 percent of all housing constructed in the borough during that decade, according to the Pratt Center for Community Development, a university based advocacy, planning, the actual number of such residences is almost certainly higher.

While the divided houses often violate fire and other safety ordinances and zoning regulations, they offer many New Yorkers their only source of affordable housing. The city has an apartment vacancy rate of less than 3 percent, according to the latest Housing and Vacancy Survey. Under state law, anything below 5 per cent constitutes a housing emergency.

In addition to recent immigrants, the divided buildings house college students and provide a lifeline for low-income people as well as New Yorkers hard-hit by the recession.

The foreclosure crisis has spurred more of these divided homes. The illegal apartments provide steady rental income to homeowners who cannot otherwise meet their mortgage payments.

A Strain on Communities

But while the divided dwellings fill a need, the units clearly pose serious dangers, most notably to the people who live in them. Many basements and cellars have only one exit, limiting means of escape in an emergency. Exposed and overloaded electrical wiring create an increased risk of fire, as do the portable accessory heaters and hot plates that many tenants use.

Neighbors express irritation about the population explosion on their streets. Complaints to the city's Department of Buildings, its 311 non-emergency hotline and community boards have phones ringing off the hook. These "overstuffed units," to use Chhaya's term, have put a strain and drain on city resources and services, community spokespeople say. In some neighborhoods they contribute to overcrowding at schools and hospitals.

"The result is that a lot of people who grew up here are moving to Long Island, or upstate, or out of state. They say, 'That's it. I'm done. I've had it. It's not worth it. I'm leaving,'" said Wendy Bowne, president of the Richmond Hill Block Association.

In Fresh Meadows and Jamaica Estates, the issue is college students, who rent out upper floor of houses from absentee landlords, according to Marie Adam-Ovide, district manager of http://www.queenscb8.org/ Community Board 8. "We have a weekend, 11 p.m. to 2 a.m. problem," she said. That's when college students' parties spill over into the front yard. ? We have an underage drinking problem," Adam-Ovide said.

In Community Board 10, "about 40 per cent" of complaints are about illegal conversions, estimates chairperson Elizabeth Braton. "Most are cellars," she said. "Cellars are never legal."

The City's Approach

Following the deadly fire in Queens, the city stepped up its efforts to educate people about the dangers of illegal conversions. The buildings department and the fire department have been distributing tens of thousands of leaflets in a number of languages warning people that such homes can turn into deathtraps in the event of a fire.

Building Department inspectors are the front line in the city's fight against illegal conversions. When the city receives a complaint, sends the inspectors to check out the situation. But politicians and community and housing groups say the complaint-based system is punitive, inefficient and lacks sufficient enforcement mechanisms.

The inspectors, however, often cannot get access to the property. According to an audit of the Queens division of the Department of Buildings by New York City Comptroller William Thompson, Jr., inspectors with Queens Quality of Life Unit responded to 8,345 complaints of illegal conversions in fiscal year 2008. They could not gain access on the first time around to 3,279, or 39 percent of the locations.

If inspectors do not get access the first time, they return. Then, if they still are not admitted, they can either drop the case or issue a warrant. Thompson found warrants were issued to less than 1 percent of the illegally converted properties. Throughout all five boroughs, the city has obtained 107 warrants - only about 13 a year -- since 2002, the Daily News has reported.

The Mayor's Management Report, however, paints a somewhat different picture. It said that during fiscal year 2009, the buildings department received 23,326 complaints about illegal conversions of residential space. Inspectors managed to gain access to 49 percent of those locations and "issued violations to property owners in 16 percent of these cases."

In the case of the Queens fire, the city sent investigators to the building in response to complaints in 1990 and 2004. Both times, the inspectors found no violations, Tony Sclafani, a building department spokesman told the New York Times.

Units that are inspected and found to be illegal receive a notice of violation. If the owners do not make the necessary repairs, they are fined and fined again. The fines for repeated violations can reach $15,000. But the fines are rarely paid.

If the inspector deems there is imminent danger to the occupants, a vacate order is filed. According to Thompson?s audit, the buildings department did not follow up on 657 vacate orders in Queens that were issued in fiscal year 2008.

Sclafani has said the city evacuated 1,086 illegally converted apartments in 2008. After the Nov. 7 fire, the Times reported, inspectors found eight rooms next door and evacuated all of them.

Closed Doors

Thompson and Queens Borough President Helen Marshall say the city needs more inspectors. But more inspectors do not mean more access.

"Without a permit they can?t do much," said Bownes. She said that when Rudolph Giuliani was mayor, people from the fire and police departments accompanied the inspectors. Now, she says the homeowners "laugh in the face of the Department of Buildings."

"Maybe if the Department of Buildings were able to enforce the law, word would get out and people would not buy over their means, would not resort to making illegal apartments," Bowne says.

"When the inspector comes, the kids just don't open the door," Adam Ovide said. She said she has seen only one successfully conducted inspection in her two and a half years working for the community board. That building, she said, "was just terribly dirty and unkempt. The yard was full of weeds."

But Mary Ann Carrey said the situation has "improved greatly" over the more than 20 years she has been district manager of Community Board 9.

She said that, in an average month, she gets seven or eight complaints. Her staff goes with the inspectors who usually get access to the building. Still, she said, "enforcing the system is a problem. ? Complaints are so low priority that the courts seldom hear the case."

Even if the hazardous condition in the home can be removed, the problem has not been solved, Carrey said. "If you have three families living in a zone for one or two families in a home, then you?ve got a problem. You cannot just change the zoning code. So what do you do then? I remember Koch saying back when he was mayor, 'What do we do after we evict them? Where are we going to put these people?'"

Looking for Answers.

That is the issue Chhaya hopes to confront. The current complaint system "is not working," said Seema Agnani, the group's managing director of Chhaya. "Penalizing owners has little impact on the housing ground. ? Moreover the complaint system pits neighbor against neighbor, causes discord and distrust."

Chhaya, whose name means shelter, focuses on improving housing opportunities in New York for South Asians and other immigrants. In a survey of homes in Jackson Heights and Briarwood/Jamaica, Chhaya estimates that about a third had an "accessory unit" that could be "potentially legalized."

To accomplish this, Chhaya envisions a pilot program to create a new category of residence, the "Accessory Dwelling Unit" in the city's building code. A panel of expert architects, engineers and planners could determine how these rooms and apartment could meet fire, safety and health rules. Education program in several different languages, offered through private and nonprofit partnerships, would teach homeowners and new homebuyers the city's ordinances and rental laws.

Owners who voluntarily comply with the process and fix their residences to comply with standards for the new accessory units would receive financial assistance from the city and be given a grace period of 12 to 18 months, during which time they would not be fined. "Currently, owners do not have enough of an incentive. "It can take $10,000 to $15,000 to legalize the dwelling. It can take a year," Agnani said.

After the completion of the reconstruction, the owner would receive a certificate of residential status.

In addition, be a community task force would access the impact of increased population density on neighborhoods. "Public resources are allocated based on population. If you bring these units into regulation, if you account for them, the city can allocate more resources for sanitation, can better accommodate overcrowded schools," Agnani says.

Bowne says she refers renters and owners to Chhaya. "They educate people who do not know the law," she said. But, she has doubts about whether the group's proposal will address her community's concerns.

Bottom line, she said, "The illegal conversions are exhausting our city services."