Helping Young Mothers Help Their Babies and Themselves

When Sheena Persaud became pregnant at 17, the Queens resident did not know much about taking care of a child. She did not have a high school diploma or many other resources.

Such difficult circumstances can often threaten the well being of both mother and child. But Persaud decided to try to improve her odds. She enrolled in the Nurse-Family Partnership, a free city program, and began getting weekly visits from visiting nurse Carol Coleman. Together, they discussed parenting techniques, healthy nutrition and communicating with infants.

"The program taught me what to expect when being a mom," Persaud said. "If I didn't join it I wouldn't know half of what I know when it comes to taking care of a baby."

Now a graduate of the program, Persaud has earned her GED high school equivalency certificate. She is working in a bakery and but hopes to train for a career in nursing. Her daughter Serena is two.

THE HIGH RISKS OF POVERTY

Children such as Serena face daunting challenges. More than half - 54 percent - of children of single mothers in New York City are poor. And, according to the Children's Defense Fund, poor children are more likely to die before their first birthday than more affluent children. Once they start school, they are twice as likely as to have to repeat a grade and three and half times as likely to drop out.

A lack of parenting skills can take a more immediate toll. New York City government recorded more than 65,000 reports of child abuse and neglect in 2006. In the first 11 months of that year, 40 of the children suspected of being abused died -- though not necessarily because of that abuse.

A SIMPLE REMEMDY

The Nurse Family Partnership takes a simple approach to such overwhelming problems. Under the program, a registered nurse visits a low-income, first time mother, starting during the woman's pregnancy and ending after the child turns 2. The goal is to help mothers have healthier pregnancies, to improve the child's health and development, and to assist the mothers in becoming more self-sufficient. During the visits, which take place every week or so, the mothers learn how to breastfeed, create a healthy environment for the child and plan their future pregnancies. The nurses also listen to the mothers' concerns.

The visitors "give young mothers the sort of cajoling and practical wisdom that in other times would have been delivered by grandmothers or elders," David Brooks wrote in a recent New York Times column.

"A first-time mom isn't sure of what's going to happen, you don't know what life is going to offer you and at least this is giving you a head start on it," visiting nurse Eulanda Greene, who works in Jamaica, Queens, said.

The program is the brainchild of psychologist David Olds. Working in a day-care center in Baltimore, Olds thought the care and he and his coworkers were providing there was "too little, too late" and that children would be better served if their parents received some assistance earlier. In 1977, Olds and some colleagues came up with the idea to have a registered nurse visit low-income, first-time mothers.

This concept, Katherine Boo wrote in a 2006 New Yorker article on the program, "is rooted in a pessimistic view of the future that awaits an American child born poor -- a sense that the schools, day-care centers, and other institutions available to him may do little to nurture his talents. Shrewder, then, to insulate him by an exercise of uncommon intrusion: building for him, inside his home, a better parent."

GETTING RESULTS

Pessimistic or not, it seems to work. A study conducted in Memphis, one of the first cities where the partnership was implemented, found children whose mothers were in the program spent 80 percent fewer days in the hospital for injuries or swallowing something hazardous than other similar children. Three studies of participants in the program found an array of other benefits. For example, both parent and child were far less likely to spend time in jail than they might have been had they not taken advantage of the program. The RAND Corporation has figured that every dollar invested in the program produces a return of $5.70, coming saving society about $34,148 per child.

"When it comes to improving the odds for poor mothers and infants, it's hard to beat the Nurse-Family Partnership," Mayor Michael Bloomberg said in this year's State of the city speech. "Through one-on-one nurturing and guidance, NFP helps first-time mothers build stronger futures for themselves and their children."

NEW YORK'S PROGRAM

Over the years, the program has expanded and today serves about 20,000 families in 300 communities across the country. It was first introduced in New York City in 2003 with an office in Jamaica. A year later the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene expanded it expanded to Harlem. The program is aimed at the parts of the city with the highest infant mortality and teen pregnancy rates: South Bronx, East and Central Harlem, Central Brooklyn, and Jamaica East. It also tries to reach young mothers in foster care, homeless shelters and at Rikers Island.

Now, Bloomberg has pledged to expand the Nurse-Family Partnership by 50 percent in New York City by the end of the year. That would raise the budget to $3 million, enough to serve 1,300 families. Currently, the program can visit 845 families, but only 420 take advantage of this free resource. Many others simply do not know the program exists.

One other obstacle to the program's further expansion, according to a report in New York magazine, is the city's shortage of nurses.

Though the program costs about $5,500 per family a year, Lisa Landau, director of the Nurse-Family

Partnership for the health department, said it will reduces costs for New York City taxpayers in the long term. "There are savings in health care costs, child neglect costs, juvenile justice and there are also lower arrest rates for children and their parents," Landau said.

A 2004 report by the health department anticipated, based on previous evidence, that in New York City, the program would reduce child abuse and neglect among participants by 50 percent, and increase the amount of time that mothers in the program wait before having their second child, a change that cuts the risk of the premature births.

Having worked in the Jamaica, Queens office for almost four years, Greene said she has already seen the effects. The young mother, she said, make real progress.

"We teach them how to understand the baby's cues," Greene said. "They find out that it's normal for babies to cry and always put things in their mouth. I even have them observe other mothers on the streets and they realize so many of the mothers are not really paying attention to their children. A simple thing one client told me is that she saw a toddler walking with his mom and the mom was practically dragging the baby. She has to know he has short legs and he can't walk as fast as she can walk."

After graduating from the program, Persaud said she learned how to take care of her daughter, but she also learned something she wasn't expecting: how to take care of herself. "The nurse always motivated me to do something with myself," Persaud said. "She would push me to do things all the time. She even picked me up and took me to get a library card one day so I could study. Because of her I have everything. If it wasn't for her I wouldn't be so active, I would just stay at home and take care of the baby."

Â

After Prison

GOTHAM GAZETTE:

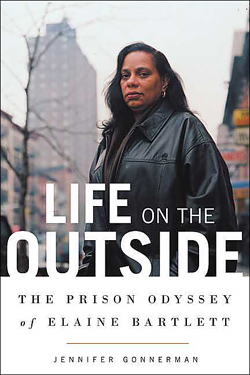

We're here with Jennifer Gonnerman, formerly of the Village Voice, who will talk to us about Life on the Outside: the Prison Odyssey of Elaine Bartlett. The book uses the story of one woman to talk about some issues facing the city, and the nation as well – but our focus is the city. These issues are the Rockefeller Drug Laws, and ex-prisoners' reintegration into society.

Ms.. Gonnerman, when you met Elaine Bartlett, you were working as a reporter for the Village Voice, meeting with various inmates. What struck you about her, that you would spend the next several years writing a book that rests on her story?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: I met Elaine Bartlett in 1998 when she was in Bedford Hills prison doing 20 to life, and she was in year 14. At that time I was at the Voice, and it was the 25th anniversary of the Rockefeller Drug Laws, which no one was even writing about because by news standards there was no real news reason to write about it – they had been on the books for so long and nothing had changed. I used the anniversary as an excuse to interview five people [in New York prisons] who were doing at least 15 to life for a first drug offense under the Rockefeller Drug Laws.

That day at Bedford I interviewed three women; she was the last. The first two women who came in got all dolled up for the interview. Elaine came in last, and she looked like she hadn't gotten out of bed in a month. She purposely wore her whole uniform; she certainly hadn't brushed her hair or anything. I didn't want to ask any questions because she looked so deeply depressed. I was afraid that if I asked her about her life, or her sentence, or her prison circumstances, that she might just break down and cry. But of course I was there, and that was my job. So I started asking questions, and she started answering them. She was so both blunt and honest about her life, and perceptive, that I was just very struck by her.

I found her to be such a good interview – and of course her story is so unbelievably compelling: she was doing 20 to life, went in when she was 26, when she was locked up she had four kids under the age of 10, it was a first offense –

GOTHAM GAZETTE: -- And she was set up.

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Yes, and she was set up. I didn't even know half the stuff that's in the book at that time. In fact, I didn't know there was going to be a book. But I did quote her in the piece extensively, and ended up writing another piece about her a year later before she got clemency. When she got out of prison, I was there. The book grew out of those articles from the Voice, but the relationship really started with that very first meeting.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Do you remember anything specific that she said in that first meeting that stuck with you?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: The meeting was April 1998, and her mother passed away in either February or March. She described going to say goodbye to her mother. This meant leaving Bedford Prison in a van, shackled, going to a hospital in East Harlem, and walking through the hospital in shackles to say goodbye to her mother, who she hadn't seen outside a prison setting in 14 years. Her mother is in bed, a day or two before her death, and she basically just climbed into the bed next to her wearing the shackles. It had happened just a few weeks before, and she was crying when she told the story. It's just the kind of thing you never forget.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You write that in many ways she is not typical of the people who are in prison, and the people who are in prison for the Rockefeller Drug Laws. So two questions: how so? And then, the obvious question: Why write a book about her in particular?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: It's probably impossible to pick any prisoner and say, "this prisoner is completely typical." Because prison is just like society – who is the typical American? She's unusual because she's female – that puts her very much in the minority.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: About 15 percent of prisoners are female?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: I think it's less than that.

Elaine was also unusual because she was at Bedford Hills, which is the only maximum security prison for women in New York State, and it also had a college program. Many prisons used to have college programs, but they eliminated virtually all of them in the mid-1990s when Congress voted to take Pell Grants away from prisoners. But Bedford raised money privately, so Elaine was able to continue an education, get an associates degree, and move towards a bachelors. So by the time she came out she was much better educated than most other people coming out of prison.

She also did a tremendous amount of time – 16 years. That's an extraordinary amount of time, especially for a non-violent offense. You see a lot of people going in and out, but for someone to do such a long stretch at one time is pretty unusual.

ROCKEFELLER DRUG LAWS

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How do the Rockefeller Drug Laws work? And you can say they don't really, but what is the mechanism of it?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: The Rockefeller Drug Laws were created in 1973 under Governor Nelson Rockefeller. They were the first mandatory minimum drug laws in the country, so in a lot of ways they kicked off the nation's War on Drugs.

Mandatory minimum sentences mean that your prison term is mandatory. The power has shifted from the judges to the prosecutors in a sense in determining what the severity of your punishment will be. The judge's hands were essentially tied; once you were convicted of a certain crime he or she had to give a certain punishment, a mandatory punishment. And the way that the punishment was determined was by the weight of the drugs involved, not, for example, by whether you were a drug kingpin or a drug mule.

In Elaine's case she was arrested for a drug sale to an undercover cop for more than two ounces, the highest level, an A1 felony, in New York State. So the judge was required to give her at least 15 to life. She had the bad luck of having a judge up in Albany county, "Maximum" John Clyne, who gave her twenty to life.

This way of fighting the War on Drugs was copied across the country, and also by the federal government. These laws are still on the books, even though many states have softened them.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: They also don't place all drugs on an equal footing.

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Well, the Rockefeller Drug Laws apply to cocaine and heroin. Meanwhile, New York State has a very lenient policy on marijuana. Possession of small amounts of marijuana is technically a violation, not a crime. Way back when, in the 1970s, a lot of middle college kids started getting a lot of state prison time for marijuana, and parents went ballistic. You had a lot of parents up in Albany lobbying, and that's when they started to really decriminalize marijuana in New York State. I always felt if you had the same kids getting locked up under the Rockefeller Drug Laws, maybe we wouldn't have the situation we have now, which is that roughly 94 percent of inmates in the state prison system who are there under the drug laws are African American or Latino.

BOB ZANE: It seems like before Governor Rockefeller signed these laws he had a liberal reputation. Then he made these drug laws. Do you think one of the reasons he did this is because he wanted to run for president or vice president of the United States?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: A lot of people who were around him at the time basically said as much. There was such a marked difference from the past; they felt he had gone from playing for a New York audience to a national audience. He had to shore up his conservative credentials, and what way to do that faster and easier than appearing tough on crime?

REJOINING SOCIETY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You write that when you interviewed Elaine after she got of prison, you imagined this as the happy ending to her prison story. But your book continues for years, following her difficult effort to rejoin society. What trials that she faced surprised you the most?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Well, everything surprised me. The day she walks out of prison, she describes it as the happiest day of her life, of course. I had been going up to visit her in the weeks before, as the excitement was building. After fighting for a couple of years, she had received clemency from Governor Pataki. He had only given it to three or four people out of 70,000; it's like winning the lottery. So she got four years shaved off her sentence.

Elaine imagined that this was a happy ending to a very traumatic and tragic story. I thought it was the beginning of better days. It turned out we were both very, very naĂŻve and overly optimistic.

I thought that when you get out of prison, you'd find a place to live, you'd get a job, and in six months you'd be up and running. After she got out of prison, I wrote a piece for the Voice about the release. I continued to stay in touch with her. Sometimes she would call me at the Voice and explain the scene in her apartment, and her relationships with the kids, which were increasingly frayed. She used to say things on the phone to me like, "I left one prison to come home to another." That phrase is almost like a mantra that runs through the book. I realized in a lot of ways that the story was just starting, the struggle was just beginning. It was another whole journey she was about to undertake.

I ended up following her for the first year for a piece that ran in the Village Voice in 2000. It was 18 pages in the Voice, very long. After the piece came out, she had a job. She didn't really have a place to live yet – she was still living with her children at the Lilian Wald houses on Avenue D. And we stayed in touch and would hang out sometimes. She would say, "Hey, how about you write a book." And I would say, "A book? 18 pages in the Village Voice isn't enough? How much more is there to say? Is there really anything else going to happen here?" I didn't know. She promised me that the story hadn't ended, and of course it had not.

It got to this question of how long it takes someone to re-enter society, and to get back up on their feet. The book ends up following her over four years, and I would say the process continues even to this day. Especially someone who did as much time as she did. She went in at 26, and when she got out in some ways she was still 26 and in other ways she was 42. So there was this incredible learning curve. That's a lot of what the book deals with. People use the term reentry. For a lot of people coming out of prison it's much more complex than that. In a lot of ways I think it's a lifelong process.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: In general, is the difficulty in getting out of prison because of actual legal barriers, or because prisoners have been damaged socially by being in prison?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Well, both.

The list is so long about what the problems people face coming home from prison. It's become an increasingly popular subject in the last three or four years. There's a long list of things prisoners can't do: in New York State you can't get a barber's license. If you're on parole you can't stay out after nine, can't vote, can't legally live in a housing project, even though the housing projects are full of people that have been through the prison system.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: No matter what the crime was that you were convicted of?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: The laws vary state to state. In New York you can't vote if you are on parole -- it doesn't matter what the crime is. Most people coming out are on parole. There are basic parole rules and then sometimes they add on special ones.

The barber's license you can't get if you're a convicted felon unless they make a special exception for you.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: In the Drum Major Institute blog there was the story of a guy who was in prison –

JENNIFER GONNERMAN; -- Marc LaCloche. He was a barber on the inside, he was trained by the prison system and became very good. He came out and wanted to be a barber and why not? He couldn't get a license, and he fought and it was a court battle, and he won, and then it was appealed. It was endless. One day I was sitting at the Village Voice and someone called me and told me Marc LaCloche had passed away. And in a very small world, he was a little bit of a celebrity, because he was the one person who actually tried to fight for his rights. He was en route to Potters Field, and we ended up writing a piece on him in the Voice. All these people came forward and donated money and he ended up being buried in New Jersey in a cemetery.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How had he died?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: He ended up dying of AIDS.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What I don’t understand is why they trained him as a barber in prison in the first place if he wasn't allowed to practice when he was released.

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: It makes no sense, but it's not really unusual. What people spend their time doing in prison often times has virtually no relationship to what work they may be able to do on the outside.

This speaks to a larger ambivalence on the part of society about what are we putting people in prison to do. Are we trying to punish them or are we trying to rehabilitate them? There was a time when prisons were thought to be correctional facilities and rehabilitation was the goal. But over the last thirty years or so there has been a shift to pure punishment. This is why you have virtually no college programs anymore, why you have people not trained for jobs that they could actually do, or trained for jobs that don't exist.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: These are things that are obviously barriers. What about the psychological issues? Would these exist no matter what?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: When I was thinking about Elaine getting out of prison, what her year would be like, and what I would be reporting on, I had been thinking that as long as she gets an apartment and a job that she'd be okay. But she had four kids, and for her the biggest struggle coming out was not finding an apartment or a job -– although those struggles were enormous –- it was trying to be a mother to her children and repair these deeply damaged relationships, and make up for all of this lost time.

She has four kids. When she got out of prison, one was at Rikers Island on a drug case of his own, which was something she had to deal with. And though obviously her kids were thrilled to have her home, her two youngest daughters were very upset because their mother had been gone virtually their entire lives. Trying to help these kids who had basically grown up without parents was her full time job in a sense. That speaks a little bit to the psychological ramifications that someone faces when they come home. I think that in some ways they are a little more pronounced for women if they are the primary caretaker.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is there a most common way that former felons end up in jail?

|

Bedford Hills, the prison for women. |

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Well, there are many ways, but one of the main ways is through parole violations. This can mean any of a host of things – that you give your parole officer dirty urine, failing your drug test; maybe you've stopped going to your parole officer altogether because you don’t want to give him dirty urine, or you're tired of parole. Drugs, in many ways, are the things that take a lot of people back. Either possession or sale, or some crime related to it, or using drugs and disappearing and not reporting to your parole officer anymore.

But also, and this isn't dealt with so much in the book, there are a tremendous amount of people in prison who have some sort of mental illness. And you think the problems were hard for Elaine. When mentally ill people come out of prison, they have very few resources, and often there are periods of time when they can't get their medication. They may behave in ways that are not criminal but just so bizarre that their parole officer thinks that it's better to lock them up before they do something. Mental illness is often what brings people back into the system.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is there a happy ending to the Elaine Bartlett story? The book ends in 2003. We don't even know if Nathan, her boyfriend who was arrested with her when she was 26, gets out of jail.

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: He did get out of prison, shortly after the book was published in 2004. This was not specifically related to the book's publication, but the legislature had changed the way that merit time was calculated in part because of the activism of people like Elaine Bartlett.

All of the problems that are detailed in the book don't stop existing after it comes out. Life goes on. The damage done to her entire family by her absence over such a long period of time runs so deep that [it can't be erased] no matter what she does over the next twenty years. She says this herself in a very memorable way: "After being away for 16 years you come home and you're a complete stranger to your family. They love you but they're angry with you at the same time because of everything they went through in those 16 years and you weren't there. You can't get the birthdays back, you can't get the graduations back, you can't get the nights they laid up crying wanting mommy and she was nowhere to be found. You can't get those years back. No matter what you do in life you can never go back." I can't say it any better.

MARTHA SOFFER: What's she doing now?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: She is living in the same place she is at the end of the book, in Washington Heights. She is still trying to rebuild her life. She puts tremendous amount of energy into her granddaughter Tanae. From the passage I just read you can see that the pain of not raising her children is never going to go away. So it's almost like she's trying to be a mother to the grandchild. She had her kids quite young, so if you saw her on the street with her grandchild you might think that was her kid.

MARTHA SOFFER: Is she working?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: She was working, but she just lost her job and I don't think she has a new one yet. The struggles go up and down. There have been good streaks and bad.

MARTHA SOFFER: What kind of work was she doing?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Her last job, I believe, was answering telephones at a community center on the Lower East Side.

EASING THE TRANSITION FROM PRISON

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Do city, state, and federal government have responsibilities or incentives to create programs for ex-prisoners? Are such programs politically feasible in New York?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: In the last three or four years there's been a tremendous focus on prisoner reentry, which means there's also been a lot of federal money going into a lot of programs across the country. There's been a tremendous sea change. It used to be that people just talked about, "lock 'em up, lock 'em up", and there was very little thought about what happened on the back end. Now there's been a real focus on that though it's hard to generalize nationally.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What about in New York?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: There are a number of different places people can go for services. The biggest thing is housing. It's a problem for everybody, but the shelters are full of ex-prisoners with nowhere to go.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Are there specific programs for ex-prisoners in terms of housing?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Not so much. There is a little bit of housing specifically for ex-prisoners, but a lot of people in New York City need housing who never committed a crime. That's just a huge problem citywide.

MARTHA SOFFER: What about organizations that can help you get a job?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Yeah, there are a lot of organizations. New York City actually has a much higher number than most places, so in some ways Elaine was fortunate that she came home here. There are places like the Osborne Association, the Fortune Society. There's a lot of different places that if you go in there after you've gotten out of prison they will help you get a job. What do you do in an interview? How do you make a resume? What do you say? What do you not say? How do you deal with the inevitable question, "Do you have a felony on your record?" It is possible to get a job for a lot of people when they come out of prison.

This is dealt with a lot in the book. This guy named George Lino helps Elaine to get a job. He plays a very important role by giving her very straight-up advice on how to get a job. He told me once that getting people into jobs is not the hard part; it's making sure they keep their job. This might seem counterintuitive, but these people are coming from a highly structured environment where every decision is made for them. Suddenly they're on the outside and responsible for themselves. They may not have used an alarm clock in ten years. They never wear a watch. There are a lot of things that people may have never dealt with that they must learn before they can be a reliable employee.

FORMER PRISONERS AND ACTIVISM

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Are there specific programs that are known to be most effective, and are they focused here in New York? You said New York is known for its programs. Is it because they're more effective, or just because there are more of them?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: There are a lot of programs here in New York. I mentioned a couple of them; there are many more I can mention. There's a program called Exodus that started in the last five years in East Harlem. It was started by Julio Medina, who was a drug gang leader from, I believe, the Bronx. He did a lot of time, he came out, and said he wanted to start his own organization for people coming out of prison. I met a lot of people who after coming out of prison said they wanted to start their own organization where they gave back and did something positive. He's one of the only people I saw who pulled it off. All the skills he had used in the past to commit crimes he put to good use. He was actually with George Bush at the State of the Union a couple of years ago as a model program. It was very much about people who have come out of prison helping other people who are coming out of prison – a peer model. I think it is a very powerful model, people saying, “I know what you're going though because I've been down that path before.”

One of the things about coming out of prison for Elaine and a lot of people that's so difficult is that you don't have role models. You may know people who have been locked up again, but it's hard to find people who have broken out in the ways you were suggesting. Elaine was very hungry to find those people, to try to follow their lead. Programs that hire a lot of ex-offenders, like Fortune Society, play a crucial role in helping people figure out how to overcome all the legal and psychological hurdles.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is there a group of people who have devoted themselves to fighting the Rockefeller Drug Laws? Has that given them a purpose in life?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: One of the themes that runs throughout the book is the role that Elaine's activism plays, politically and statewide, but also in her own personal life. After she gets out of prison she does become an activist, hanging out with Tony Papa and other prisoners-turned-activists who did time under the drug laws. For her becoming an activist, speaking at rallies, telling her story again and again, it was therapy, and it was also a way to rewrite her history. I don't mean rewrite by changing the facts of what happened, but by recasting prison as less about a tragedy that decimated her family, but more about, "I went through this and now I'm going to help people avoid the same fate, and change the laws so they don't have to do as much time as I did."

But one of the things about coming out of prison, as I mentioned, is that most people are on parole. And when you're on parole you can't associate with other people who are on parole – other felons. Now that makes sense on the one hand, because you don't want someone who you're trying to steer in the right direction to be hanging out on the corner with people who are selling drugs. But it does make this question of peer counseling or looking for new role models a little more complicated.

CALVIN JOHNSON: I have a question carrying on the theme of activism. To what extent were you motivated by activism as well? Certainly the Village Voice has a reputation of that journalistic style. Can you comment on where you saw an activism agenda or political implications of the book? Beyond telling a story, what are the effects that reach out into the larger situation?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: I felt like my personal goal, mission, or purpose was to tell the story as clearly and frankly as possible. What happened after that, politically or otherwise, was out of my hands. I also thought that it wasn't my concern in a sense. One thing that happens with journalists who are well meaning or trying to make a difference, is that there's an impulse to sugarcoat the story. And I think that doesn't make for good journalism.

As an example, when Elaine gets out of prison she is very frustrated and angry, like most people. Her youngest daughters are home, and she starts bossing them around, acting like she thinks a mom should. There's obvious tension, and a couple of times she becomes physical with them. I felt that was a very important thing to put in the book. This speaks to how deep the problems run, how deep the frustrations and anger truly are. Controlling her temper is going to be one of the challenges through the rest of her journey. Of course, this might not be something that an activist would want to read.

TARA McISAAC: I wanted you to comment more if you could about low-income housing. The state funds for low-income housing were re-routed into building prisons. I was appalled at that, and I was wondering if you could educate me any further?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: I don't know much more than what's in the book, but it talks about state money being earmarked for low-income housing and then being diverted, and I talk about how it was used to build prison cells in upstate New York. One of the saddest parts of Mario Cuomo's legacy is that he built more prisons than any governor before him.

In a lot of ways his hands were tied. You can say, "Well, that's a horrible thing. He shouldn't have done that." But the state legislature had passed these incredibly punitive Rockefeller Drug laws, so he's required, once they are given these very hefty sentences, to put them someplace. For the laws to be changed, the legislature had to change them. And no one was willing to go out on a limb – or what was perceived to be a limb – and change them. That only happened within the last year or two.

It is one of the little known tragedies. We have now 66,000 people locked up, most of whom are in upstate New York. You go to these little towns near the Canadian border and it seems like every other person is a prison guard, because that's the number one employer. All that money that's going up there is money that's not being spent for low-income housing here, or other things. It's extraordinarily expensive – about $32,000 a year – to keep somebody locked up. I think I estimated it cost about half a million dollars to keep Elaine locked up for all that time.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: There are two other aspects of what you were talking about. One were the electoral politics of that – how prisoners are counted as residents upstate.

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: This is something that has been getting a lot of attention thanks to the work of one or two people. I'm guessing on the numbers here, but between two-thirds and three-quarters of prisoners in New York State prisons are from New York City. Once they leave the five boroughs their numbers are counted in the Census wherever they are placed. Since virtually all the prisons are upstate, those districts look larger. Obviously they are allocated funds accordingly. There has been a push to count prisoners in their home zip codes, which would benefit New York City.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: The idea is not just that the money is allocated upstate, but that there are more representatives upstate than would be otherwise because there are more districts there because of the populations who are imprisoned, even though they are not allowed to vote for candidates. Some people have compared this to the 18th century where slaves were counted for purposes of apportionment but could not vote.

TERRI GOLDBERG: One thing that was very striking to me in the book was parole violations. I was amazed that they were as strict as they were: the voting, what kind of dog you could own. Do you have any idea of how and why they come up with these? It almost seems like they're still in prison.

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Well, you know you can't have a rottweiler or pit bull if you are on parole. Officers don't want to get bitten when they do a house visit. They don't make these rules up for no reason. You have to be home by 9 pm and can't leave before 6 am. That's because officers do house visits to check that you're actually living there. They want to be able to show up at 9:15 and know you'll be there.

But there is a sense that you're still in prison after you leave. Just as I was saying with the prison system that there has been a shift from rehabilitation being the focus to straight-up punishment, the same thing is true with parole. So while there are a lot of parole officers trying to help people when they get out of prison, the pressure is on them to just play the role of law enforcement, just be a cop in a sense. There is very little incentive to not lock someone up, and the fear is that if you don't lock someone up they're going to commit another crime and you're going to be called into your boss's office.

CHANGES IN THE DRUG LAWS

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Let's go back a little to the drug policy, which was changed in 2004. What did these changes mean to people who had been convicted of drug offenses, or for those who are being convicted now?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: I don't recall all the numbers off the top of my head, but people that were convicted under the A1 statute, the most extreme statute, received less time than they would have previously, a few years less. It was retroactive. But most people who are in the system under the drug laws are so-called B-level felonies, a lower level. They were not affected by these laws.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Do you think the change in administration in Albany will bring more substantial change to the Rockefeller Drug Laws?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: It might. But nobody wants to appear to be not tough on crime. It's political suicide. So it's very hard for even the most well-meaning lawmakers to make changes like this. There were some small reforms a few years back, but the laws had basically been unchanged for 31 years. So I don't think you're going to see overnight some dramatic difference. It's a very complicated issue, and very difficult for lawmakers to sort out.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: You mentioned that 48 other states have similar rules based on the Rockefeller Drug Laws. Have any of them rolled back since then?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: Most of them have softened or changed their drug laws over the years. New York was one of the last. A few years back State Senator David Paterson put a report out saying that our drug laws were still the harshest in the nation, and that's because so many other states that had followed our lead had either seen the light in a sense or could not afford to have so many people locked up for so long, and had consequently reduced the length of some of those sentences.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: The ones who have softened up, their reforms were more thorough than New York's in 2004?

JENNIFER GONNERMAN: It's hard to generalize, but yes. The perception was that New York State laws were changed, but it wasn't a huge reform. One of the sticking points in these debates about New York drug laws is the idea of mandatory minimums: who should have the power to decide how much time somebody is doing? Should it be in the hands of the judges or should it be in the hands of the district attorneys? A lot of activists want to undo that so that judges have more discretion. Of course the district attorneys association doesn't want to give up power and has been fighting that. So the structure has remained in place. There has been some tinkering around the edges, but it's a battle that is going to continue to be fought.

Â

New Help For the Working Poor?

After years of Republican policies in Albany and in Washington, Democrats are assuming power in both capitals. What difference will this make for the working poor and others struggling to make ends meet?

And what changes do New Yorkers, particularly low-income New Yorkers, want from their new officials? In the Community Service Society’s 2006 annual survey, “The Unheard Third,” both low-income and more affluent New Yorkers put two issues at the top of the list of their priorities for their newly elected officials:

*improving city public schools and decreasing the dropout rate,

*keeping rents down and building more affordable housing.

At the same time, The Unheard Third survey dispels two common myths. Though many things divide the poor and the affluent, at least this year they share a common political agenda. Improving the city’s public schools and creating more affordable housing are the top priorities across all income groups.

The second myth is that voters are uniformly allergic to taxes. While New Yorkers oppose higher state income taxes in the abstract, more than seven out of ten say they would be willing to pay more taxes to increase state aid to city public schools or to provide health care coverage for uninsured New Yorkers. Across the board, New Yorkers want real solutions to problems, and they are willing to pay in order to get results.

During the campaign neither Governor-elect Eliot Spitzer nor many of the congressional Democrats said much about what they would do to help the working poor. But Spitzer did say he would provide more money for New York City schools to comply with the court’s ruling in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit on school funding. When the new governor assumes office, he could immediately make good on his pledge to provide the billions of dollars more to deliver a better education to our public school students.

There are many things that the city could do with this money. Everyone understands that it makes sense to invest in the early grades. But problems exist for older students, as well. And the money from the Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit could give the city some of the resources it needs to address these issues.

According to Schools Chancellor Joel Klein, 138,000 New York City public school students are over-age and lack the required number of class credits). An estimated 170,000 disconnected youth 16 to 24 have left school but are not in the labor market. An overwhelming majority of these young people come from economically struggling black and Hispanic families.

To help teenagers still in school, the city could offer more programs and incentives to keep the students in classes and to help them gain the skills they need to graduate. Not every student is college bound. Would upgraded career and technical education give them a reason to finish school? We also need to send students, parents, teachers and school leaders a clear message that every student should earn a diploma. To reinforce that message, the state could raise the legal age for leaving school from 16 to 18.

Young people who have already dropped out of school and are struggling in the labor market need skills, credentials and stipends. Some successful models exist – the Job Corps, transitional jobs, GED programs with mentoring and support services, and apprenticeships. But these programs assist only a few thousand people. And the Campaign for Fiscal Equity money will come too late to help tens of thousands more who were failed by the schools system while the state fought against providing more money to city schools. The state could create a special fund to provide money to create the needed programs to assist these young people now.

Housing is the other problem New Yorkers most want their newly elected leaders to fix. While Mayor Bloomberg is trying to expand and preserve affordable housing, the state and federal governments have been largely inactive. The Spitzer administration could work to preserve the affordability of the state’s Mitchell-Lama rental housing and Congress could adequately fund existing public housing and other rent subsidies. Beyond that, there could be a new commitment of capital for affordable housing from both the state and federal levels. Federal and state tax breaks overwhelmingly favor higher income homeowners and seniors, offering little or nothing to low-income tenants who face the highest rent burdens. The new Democratic majority could address that imbalance with relief for low-income renters, who may not pay property taxes directly, but pay them indirectly as part of their rising rents.

Nancy Rankin is director of research at the Community Service Society and creator of The Unheard Third survey, which is based on telephone interviews with 1,230 lower-income New Yorkers and a sample of 500 moderate and higher income New York City residents. Â

The Poverty Commission: Measuring Up?

New York City officials have declared an ambitious campaign against poverty, but they must also put together a fuller picture of the effects of poverty in the city, according to Lawrence Aber, a member of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's Commission for Economic Opportunity, which last month released its report, Increasing Opportunity And Reducing Poverty In New York City. Aber, a professor of applied psychology at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Education, co-chaired the commission's “work group on data evaluation.” He chatted recently about the shortcomings in the current methods used to measure poverty, and about how to determine whether the city’s new anti-poverty efforts are succeeding:

THE SHAPE OF POVERTY IN NEW YORK CITY

GOTHAM GAZETTE: In its report, the Commission for Economic Opportunity says it wants to work towards developing a "more nuanced picture of poverty and well-being as experienced by New Yorkers." What don't the statistics we currently use tell us about poverty in New York City?

LAWRENCE ABER: The main statistic that the city and the nation use is the percentage of people in households with incomes below the federal poverty line, which is now $19,800 for a family of four. That official poverty measure has a lot of flaws. The main one is that it doesn't take into account differences in what it takes to live compared to what it took in the 1960s...

A second problem is that it doesn't account at all for regional differences in the cost of living. It's the same federal poverty line in Biloxi, Mississippi as it is in the Bronx. It doesn't stand to reason that a dollar goes as far in New York as it does in Biloxi.

The third big problem is that it is a measure purely of income poverty, and it doesn't include measures of families' wealth, assets, or debt. Imagine you're making $19,800 and you own your own house, car, and vegetable patch, and you don't have credit card bills. Then imagine you're making $19,800 and you don't own your own house, car or vegetable patch, and you've got extensive debt. The poverty line can't distinguish between those two families, and the second family is much more economically stressed than the first family.

The final problem is that [we] measure the percentage of people below a cutoff instead of some kind of continuous score. It doesn't stand to reason that someone who makes $10 above the cutoff is wealthier than a family that makes $10 below the cutoff.

1.5 Million Live In Poverty? Maybe Double That

GOTHAM GAZETTE: So do you think that the commonly cited figure that 1.5 million New Yorkers live in poverty is an understatement?

LAWRENCE ABER: Yes I do. That is technically the number of people who live in households with incomes below $19,800. Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs disagrees with me somewhat, because she says that if you take into account the benefits that families get, then the number of people living in households with economic resources below that level is lower.

That's technically true.

But the official line would be much higher today if the original methodology [were reapplied]. That was based on studies that showed that it cost about a third of a low or moderate family's income to feed four people adequately back then. Now food costs less than 15 percent of a family's income. There are other expenses that are much, much higher: transportation costs for going to work, health care costs, childcare costs to be able to work. If you total up in price what on average it costs to provide minimally adequate food, shelter, clothing, basic expenses, for a family of three in New York City, Wider Opportunities for Women estimates that it costs over $40,000 to reach what it calls family economic self sufficiency.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: About how many New Yorkers would be below that line?

LAWRENCE ABER: I haven't run those numbers, but nationally it about doubles or triples the number of people who live in families that cannot meet their basic needs.

Economic Opportunity Index

GOTHAM GAZETTE: One of the recommendations in the commission's report to measure poverty more accurately is to create an Economic Opportunity Index. What is that?

LAWRENCE ABER: An Economic Opportunity Index wouldn't just measure poverty; it would measure a number of dimensions that might go into the economic security of New Yorkers. This would include the percentage of New Yorkers who are covered by health insurance, and the percentage of New Yorkers who are employed. The idea behind an economic opportunity index is to create something like the Dow Jones Industrial Average -- a composite score of many dimensions of the economic and social life of New Yorkers that represents their economic wellbeing.

A single score like that would have several advantages. First, if one dimension of economic wellbeing went up and another went down, you might say things got better or worse if you're only tracking one when, trading off, they stayed the same. A multi-factor system like that is going to create a more reliable gauge.

Second, it's an effective communications tool. One of the things the commission recommended is to demystify this process and help citizens of New York understand the economic health of their fellow citizens and the city as a whole. We think an economic opportunity index could be a big contribution both scientifically and from a communications standpoint.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Is the city already collecting the data needed to do this?

LAWRENCE ABER: No. The city has a lot of the data, but a few things would have to be collected anew. Right now city data mostly comes from people who are seeking services. Well, if poor people aren't seeking services, they're not getting into the numbers. The only way you can get some of the numbers for the population of poor people as a whole is to survey them directly.

LOOKING FOR WHAT WORKS

GOTHAM GAZETTE: The report's recommended focus on the working poor, young adults, and children under five has been criticized as too narrow, but the overall report has also been described as too vague. What is your perspective on these critiques?

LAWRENCE ABER: First, on the issue of those three target groups: [the commission has] said very clearly that there is no intention to roll back any of the current investments in low-income families, the aged, welfare recipients, and a number of other subgroups of the poor for whom the city is already doing a fair amount.

The commission identified these three groups who, as the report said, we believe can benefit most directly, immediately, and dramatically from well-focused and coordinated interventions. I endorse that, and when you think of it, in a way they are groups that society as a whole invests the least in right now. Are these the only three subgroups to address? Absolutely not. Are they ones that represent over half the poor, and where we think we can identify strategies that could make a difference in the short-run and really significantly change things? Yes.

There will be a stage two of the initiative. If the city is successful in stage one, it should cast its eyes on the next challenge.

In terms of overly vague, there were 30 commissioners working on a five-month time line with a very active, ambitious, and savvy city administration. The main way we could reach consensus was to articulate recommendations at a general enough level to be of helpful guidance, but not to micromanage.

The people in the commission are not people in government, and they don't have all the technical resources necessary to turn general recommendations into a specific action plan. When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the initiative, he also charged Deputy Mayor Gibbs to come up with an action plan and implementation plan in 60 days.

The people in the commission are not people in government, and they don't have all the technical resources necessary to turn general recommendations into a specific action plan. When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the initiative, he also charged Deputy Mayor Gibbs to come up with an action plan and implementation plan in 60 days.

Things will get more concrete with the next phase of the action plan, and they'll get more concrete after that. It takes awhile for government to turn recommendations into specific actions.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Were you able to identify any specific programs or strategies for confronting poverty in New York City that you can definitely say, "this is something worth expanding", or, "this program is absolutely not working"?

LAWRENCE ABER: The city posed the challenge to itself that said, "How can we do this without more state and federal help"? I think that there was the perception that good quality childcare for our youngest kids both worked as a school-readiness strategy and worked as a work-support strategy. The childcare tax credit is an indication of the city taking responsibility to expand resources on a strategy that works.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Were there any strategies or specific programs that you didn't think were worth the investment?

LAWRENCE ABER: The commission did look at some strategies that did come under question, but I think there wasn't a lot of general conversation at the commission about things that weren't working. As a commissioner, I personally believe we should be ready to identify and eliminate expenditures that aren't having an impact on families' real economic security and investment, and then use that money to invest in more effective strategies.

We will undoubtedly find things where we want to shift the investment. That's hard to do in a commission where people pour their life's blood into different components of that. That job is going to end up falling on government. Personally, I think, appropriately so.

HOW WILL WE KNOW WE'RE WINNING?

GOTHAM GAZETTE: What tangible ways are there to measure the success of the city's effort?

LAWRENCE ABER: The first is that there are going to be action steps. In order to implement the childcare tax credit, for example, there are going to have to be several concrete steps taken. Some city and state legislative changes will have to be made, and a new governor will have to adopt these changes. Then the word has to get to families in ways that they actually take up the tax credits. Each of those steps is measurable; you can set up benchmarks.

The goal is to take each of the action items and create such measurable benchmarks, then track the city's progress against those benchmarks.

But even if city government does all of the things the problem can be getting worse if the nation goes into a profound recession. We would know that the problem is getting worse by having an alternative measure of poverty and an economic opportunity index; those would show a worsening economic condition for New York City residents caused by the national recession.

But these measures can't be used in a simple-minded way to say whether a city initiative is working, because other things affect the poverty status of New Yorkers.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How will city agencies be held accountable for their performances?

LAWRENCE ABER: The commission recommended that New York City continue to build on its beginning tradition of accountability in a couple of other areas in city life, [such as] crime control, and homelessness reduction. There, internal benchmarks are tracked, and commissioners are held accountable by the mayor, politically and directly.

We also encourage the city government to look at approaches in other places. The United Kingdom under Tony Blair developed a major anti-poverty initiative in the late 1990s. They have developed an approach where the budgets of national agencies are affected by whether they meet benchmarks or not. This is a process called joined-up government.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: How long will it be before we can expect to see results?

LAWRENCE ABER: I think we can expect changes in government action in a year, changes in patterns of investment in two years, and changes in outcome in three years. That's enormously ambitious, but you see the logical sequence there.

One of the things that was emphasized to us a lot by Deputy Mayor Gibbs is how important the mayor felt it was to hold his administration accountable to measurable change. That's the kind of guy he is. I think he would fail by his own standards if there wasn't measurable change in three years. And I don't think he expects to fail.

Â

Fighting Poverty

Disconnected Youth

David Jason Fischer

In recent years, public and government attention has begun to focus on New York City's "disconnected youth"—young residents between the ages of 16 and 24 who are neither in school nor working. A January 2005 report by the Community Service Society of New York estimated that nearly 170,000 city residents met this description; other measures that include unemployed young people who are actively looking for work peg the number above 200,000.

In recent years, public and government attention has begun to focus on New York City's "disconnected youth"—young residents between the ages of 16 and 24 who are neither in school nor working. A January 2005 report by the Community Service Society of New York estimated that nearly 170,000 city residents met this description; other measures that include unemployed young people who are actively looking for work peg the number above 200,000.

As is true in general for those in poverty, disconnected youth are not a uniform group. Some became disconnected when they dropped out of high school; others might be struggling to raise their own children; still others contend with physical or mental health problems or other barriers to education or employment. Roughly half have at least completed high school or a GED.

Given the differences in life circumstances, educational attainment and work readiness among the disconnected, there is no single-bullet strategy for reconnecting them to school or work. For many, high school or GED completion is the goal; others, particularly those with high school degrees and family responsibilities, are more likely to be tracked toward job readiness and employment. Unfortunately, the combination of severely limited public resources and bureaucratic confusion among numerous city agencies and programs has led to very small numbers receiving services: a 2005 report from the Young Adult Task Force estimated that fewer than 10,000 disconnected young New Yorkers were reached by city programs.

The Mayor’s Commission for Economic Opportunity identified “young adults,” including disconnected youth, as one of three groups to target for poverty alleviation. Its recommendations include expanding the alternative-education programs and settings now offered by the Department of Education, such as the Learning to Work program and Young Adult Borough Centers; increasing and strengthening “school-community collaborations” that combine education and community service to help keep youth connected; making available more programs that help young adults transition from GED attainment to college; and focusing on the most vulnerable groups -- ex-offenders and young people aging out of foster care -- with a range of services.

My organization, the Center for an Urban Future, noted in a May 2006 report that the problem of disconnected youth also creates a tremendous opportunity for New York City. As pending Baby Boomer retirements create a new and urgent need for workers in key New York City industries like health care and construction, we can work with stakeholders in these and other industries to create training curricula and career tracks that can reconnect young New Yorkers to jobs that will benefit all city residents.

David Jason Fischer is the project director at the Center for an Urban Future, a think tank focused on issue of economic development in New York City.

Lifting Children Out of Poverty

Donna Lawrence

Fifty percent of the children who are born in New York City today are born into poverty. That is a really frightening statistic. Once children are born into poverty it’s very hard to lift them out.

So, we need to ring the alarm on that alarming number. This report, this commission, is a good first step.

As a blueprint, it’s great. It sets out a framework and covers the critical areas for children and families. The fact that the mayor has done this and is taking leadership is a good signal. But the specific recommendations are going to be key.

For example, the report talks about providing health insurance to children who are uninsured. In New York City, there are about 300,000 children who do not have health insurance, and about 75 percent of those 300,000 are currently eligible for it. So it is good that the mayor recognizes that that children should get health insurance, but the plan does not go into any detail about how he will do that.

We need to know how he is going to reach those kids, what kinds of mechanisms will be put in place to insure that those kids don’t lose coverage and how to simplify the system so that families can get coverage and maintain that coverage.

The Children’s Defense Fund is trying to bring together the food stamp application with the health insurance application. Any child receiving food stamps should be eligible for health insurance, but there are a huge number of kids who get food stamps who don’t get health insurance and vice versa. This is very technical. A lot of federal regulations would need to be waived to bring those application processes together. The mayor talked in broad strokes about trying to bring the systems together. What we would want to see in six months is how far he has gone.

We need to look at things like enrolling children in health insurance at the time they’re born and enrolling parents. Now, when a mother who is uninsured comes to the hospital to give birth, there is no mechanism to enroll her or her children into health insurance.

The childcare issue is critical as well, and it’s good that the mayor is addressing it. To get mothers to go out in the workforce, we need to insure they have quality childcare. The challenge is going to be finding physical facilities. Where do we build these childcare centers, how do we get more programs up and running?

This report is a good first step. There is nothing like a mayor taking leadership on an issue like this, but he has got to keep the momentum going and make sure that the details that are filled in meet the overall recommendations.

Donna Lawrence is executive Director of the Children's Defense Fund-New York.

What Government Should – And Should Not – Do

Heather Macdonald

The government should focus on doing the things it can do and recognize what it cannot do. The dismal legacy of the War on Poverty, which destroyed the black family to the misery of generations of children, suggests that government has very little capacity to engage in what sociologist Nathan Glazer has called “social uplift.”

Government can, however, create the backdrop for individual success. New York should become the opportunity city by creating the most efficient public services in the country — the best roads, rails, communications services and parks — that allow all individuals to seize opportunity and to better themselves.

New York can become much more economically vibrant by cutting taxes and ineffective social programs that only enrich social workers. The tax burden in New York prevents many entrepreneurs from opening businesses here and creating more and better paying jobs. As Mayor Bloomberg himself says, the best antipoverty program is a job. But as long as the middle class is priced out of the city, our job growth will continue to lag far behind the rest of the country.

New York schools should be unfailingly rigorous and demanding; students should be drilled in spelling, writing, and their multiplication tables. Children should graduate not just with academic skills but also having learned to control their impulses and to show respect for legitimate authority. So far, our schools are far from achieving those goals, in large part because the educational bureaucracy remains in thrall to the knowledge-crushing nostrums of progressive education.

Government is responsible for public safety, and here, New York leads the entire country. Mayor Bloomberg and the New York Police Department come closer everyday to ensuring that residents of every neighborhood enjoy the right to safe streets.

What government cannot do is create personal responsibility and drive in individuals. Yet that is what Mayor Bloomberg is attempting to do by paying people to send their children to school or to keep medical appointments. This payment system creates a very odd situation for the long term, as well as the short term. Will the recipients ever be weaned off their payments? The entitlement mentality will inevitably suck in a larger and larger range of paid-for activities. Not just attending classes, but refraining from hitting your teacher, not bringing a gun to school, showing up for an exam, bathing your kids and feeding them -- all will be candidates for a bribe. How will the city choose which individuals to pay and explain to those it is not paying why they should act in their self-interest for free?

Finally, the single most effective way to reduce child poverty would be to restore the norm of marriage to the inner city. Children growing up in single parent homes are five times as likely to be poor as those raised by married parents. They are also many times more likely to fail in school, become juvenile delinquents, suffer mental problems, and, for girls, become teen mothers. Restoring marriage as the norm for raising children does not lie within the power of government. But the mayor can call on private groups to campaign for such a change, and put his own considerable rhetorical stamp on marriage. If successful, such an initiative would be the most important social change in a century.

Heather Mac Donald is a contributing editor at the Manhattan Institute's City Journal.

Don't Forget Those Who Aren't Working

Ketny Jean-Francois

I am one of the 400,000 New Yorkers on public assistance. I am also one of the 13,000 people in the city's Work Experience Program (WEP), administered by the Human Resource Administration. For over a year, I have been stuck doing dead-end and unpaid work. Each day I have to pull weeds from the streets and clean toilets. I do not receive a wage, benefits or a title in exchange for my labor. Instead I receive a public assistance grant. I am forced to do work that does not give me any experience to further my employment prospects. I am interested in entering the health care sector but am currently assigned to the Sanitation Department. Even if I wanted a full time job in the Sanitation Department, there is no pathway from WEP into a paid job at the Sanitation Department. This is the same for most city agencies with WEP workers.

The idea of the Commission for Economic Opportunity is a good and necessary one. But so far it is not clear how the commission’s new report will actually change the lives of people like me. It does not target the unemployed or public assistance recipients, overlooking some of the worst off in New York City.

To her credit, Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs, who oversees 11 city agencies including the Human Resources Administration, seems interested in discussing the challenges faced by public assistance recipients. Here are a few things I think the agency should do:

First, caseworkers must be re-trained in screening clients for employment and training. This screening should consider past employment experience and current interests, and should be used to place public assistance recipients in employment and training programs that will help them develop skills and access jobs that they want.

Second, the city should expand the paid transitional job programs, such as the Parks Opportunity Program, to all city agencies. This program should include different job types and positions to meet the varied interests and career aspiration of participants.

Third, as is being proposed by the commission for other populations, the Human Resources Administration should create career ladder training programs for public assistance recipients. This would enable us to get onto the first rung of the ladder and out of the revolving door of the public assistance system.

Fourth, the Human Resources Administration should work with other city agencies so that public assistance recipients can benefit from workforce development resources and programs targeted at the working poor.

Overall, while cost-efficiency tells the commission to focus on programs and populations where success is most likely, social justice requires it to not forget those of us most in need.

Ketny Jean-Francois is a member of Community Voices Heard, an advocacy organization composed of low-income New Yorkers. She lives in the Bronx with her three year-old son.

Strategies to Create Jobs

Bich Ha Pham

The establishment of the New York City Commission for Economic Opportunity and the issuance of its recent report are promising developments. The recommendations of the economic opportunity report that were particularly encouraging in regards to the adult working poor include improving and expanding benefits that support work along with ACCESS NYC (a web-based pre-screening tool for over 20 city, state and federal benefit programs), and increasing access to training for those who are working.

As the city looks to implement the strategies in the report, officials can look to a number of promising and model programs from around the country that have raised earnings and family income. These include wage supplement programs that provide cash payments on top of earnings from wages in order to raise an individual’s income to a certain level. That level can be a targeted percentage above the poverty level or a living wage level.

The transitional jobs program for one-time offenders contained in the report can be expanded to include all job seekers, including welfare participants, who along with people who have recently left welfare comprise a segment of the city's working poor. As it implements the report's strategies, the Human Resources Administration should try to provide opportunities to increase access to education and job training, including vocational job training and vocational and educational programs at community colleges.

Lastly, though it may seem like a minor part of the report, the city should not promote policies that imply that working poor people and the poor have behavioral problems. Low-wage, part-time jobs with little or no benefits are proliferating in our city and country. Consequently, so are the working poor. People are poor, not because of poor behavior, but because of a lack of jobs adequate to sustain families and of the vocational training and college education needed to get those jobs.

Bich Ha Pham is executive director of the Hunger Action Network of New York State

Barriers to College

Lynne Weikart

Though the Bloomberg report recognizes that college is an important way out of poverty, it does not address many of the obstacles that keep New Yorkers from getting a college education.

Because of structural, cultural, financial, and political barriers, millions of young people do not even contemplate college, are unprepared to attend the college of their choice or struggle to complete their studies. And those who do finish college often find themselves overburdened with debt. A new “report card on higher education,” by the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education found that, for many American families, college is becoming less affordable. Whereas Pell grants for low-income students covered 70 percent of a year’s cost in higher education in the 1990s, they now cover less than half.

The report gave New York a failing grade for affordability. In 2003, City University Chancellor Matthew Goldstein stated that almost half of CUNY students came from families in which neither parent had attended college and that 40 percent had adjusted gross incomes of less than $15,000. The cost of attending public universities and community colleges in New York represents nearly half of a low or middle-income students’ annual family income. New York does have tuition assistance but that alone does not solve the problem since New York State is investing less and less in higher education and depending more and more on tuition for revenue.

Other New Yorkers are legally precluded from attending college, since most people receiving public assistance are required to work and have no time to attend a four-year college program and do what they need to do to continue to receive their benefits. Race, ethnicity and citizenship status often affects a student’s ability to even contemplate higher education.

Moreover, recent studies suggest that policies adopted by federal and state agencies as well as institutions of higher education have discouraged low-income and minority students from attending or completing college. These practices include admitting low-income students but denying them meaningful financial assistance or conversely, encouraging wealthier, higher achieving students to attend a particular college by offering tuition discounts.

In New York and throughout the nation, the transition between high school and college is totally inadequate. Many high school students have an alarming ignorance of what academic and career avenues will be open to them after graduation. A few schools have adopted strategies to address this issue. We need to study these college readiness strategies and pay more attention to the issues of access to and funding for higher education.

Lynne A. Weikart is a professor at Baruch College School of Public Affairs

Tough Times for Seniors

Bobbie Sackman

Twenty percent of New Yorkers over 65 live in poverty, more than twice the national average. The typical elderly New Yorker living in poverty is a woman, minority, over the age of 75, living alone. Social security provides 80 to 90 percent of her income.

Unfortunately, the number of elderly people living in poverty looks like it will continue to increase dramatically. Growing numbers of minorities are reaching retirement age already poor – or near to it. Middle class seniors are moving out of the city, while the number of poorer elderly immigrants is increasing.

Unfortunately, the number of elderly people living in poverty looks like it will continue to increase dramatically. Growing numbers of minorities are reaching retirement age already poor – or near to it. Middle class seniors are moving out of the city, while the number of poorer elderly immigrants is increasing.

For the first time in history, the fastest growing segment of the city's population is people over 85. Old age brings with it declining income and wealth. Nearly 25 percent of all households headed by the elderly in NYC have incomes below $10,000, according to the census. Thousands more are near poor, which in New York City means having about $3 a day left for expenses after rent and food. A significant number of elderly New Yorkers spend over half of their income on rent. The Food Bank reports that 25 percent of people utilizing soup kitchens and emergency food banks are seniors, and that proportion is increasing.

If the city is going to address poverty in a comprehensive way, here are some things it should do to help poor seniors.

• Strengthen community-based services helping seniors to "age in place" in their homes and communities. These include senior centers that provide nutritious meals and social services, accessible transportation, affordable housing, case management to assist homebound elderly, home care, Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities, adult day services for people with Alzheimer’s, and caregiver support services.

• Help seniors access existing public benefits such as food stamps and the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption Program, which protects seniors living in rent controlled or regulated apartments from increases. Currently such programs are significantly underutilized.

• Advocate for increased Supplemental Security Income benefits from the state and federal governments.

• Create jobs and incentives for seniors who are able to work.

Bobbie Sackman is the director of public policy at the Council of Senior Centers and Services of New York City.

Getting Foster Teens Beyond the System

Betsy Krebs and Paul Pitcoff

Most young people who “age out” of the foster care system at 18 can expect to live in poverty. Too many are not prepared for college and too many end up homeless, jobless, and incarcerated. They lack the financial and educational resources they need to become successful adults.

Young people from foster care have the aspirations and potential to become fully participating citizens -- to work in accounting, design, health care, web design, the entertainment industry. The main challenge is convincing adults around them that these youth can – and must-- take on more responsibility while they are still in foster care to prepare for a future of economic opportunity. The culture of low expectations for teens in foster care and the lack of accountability for their success or failure must change.

The foster care system has been given the responsibility of raising thousands of teens to adulthood, but its primary purpose is to protect children from imminent harm, not bring teens to adulthood. As a result, the services provided by the foster care system for teens are typically inadequate, and do not focus enough on future planning as a way for the young people to rise above poverty.