After years of political wrangling and delays, components of the Fulton Street Transit Center are finally coming together.

Yesterday, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority reopened the southbound platform of the Cortland Street station, which has been closed since 2005. Recently the authority celebrated the openingof a new entrance at 135 Williams St., which offers improved access to the A, C, 2 and 3 platforms. The entrance is decorated with a refurbished mural from a now defunct midtown hotel, and is one of three entrances that will offer similar improvements.

"We have reached yet another significant milestone as we move forward to complete what will become a landmark transportation facility," MTA Chairman and CEO Jay Walder said at the event. "Once complete, this complex will provide our customers with a more seamless experience at this major downtown hub."

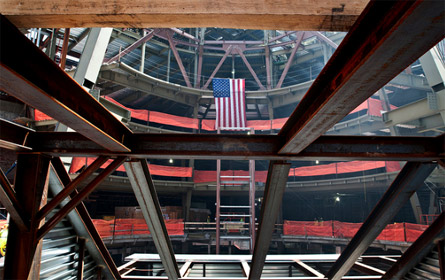

The openings come as the above-ground dome begins to take shape, as does the Dey Street Passageway, which will connect the Fulton Street Transit Center with R train service and the World Trade Center Transit Hub, which provides PATH train service to New Jersey.

By the time the complex is complete, it will link 12 subway lines and is expected to serve 300,000 riders a day.

Years in the Making

The original concept for the project dates back to the 1990s. The transit center idea came out of the Lower Manhattan Access study, which aimed to improve transportation in Lower Manhattan, according to Bill Wheeler, director of MTA planning. One of the main report's proposals called for reconstruction of the Fulton Street Complex to make it easier for passengers to transfer between various trains and navigate the complex. The project, though, gained momentum after the 9/11 attacks as part of the general push to rebuild and improve lower Manhattan.

"Anyone who knows the transit system as they do knows that the complex is a mess and is a real pain for anyone who tries to negotiate from one line to another, especially if you're unfamiliar with it," said Jeffery Zupan, senior fellow for transportation at the Regional Plan Association. "It occurred to the MTA that they could put some money into this to help make the complex better and help Lower Manhattan. It didn't come out of nowhere, but it wasn't on top of the list."

Once completed, the transit center will connect the Fulton Street complex, with its 2, 3 ,4 and 5 train services- to the Cortland Street station that serves the R, the Broadway-Nassau Station with the A and C trains, and the Chambers Street-World Trade Center station, which serves the E and PATH trains. The station will also feature a glass station house with 23,000 square feet of retail space at Fulton Street and Broadway.

The centerpiece of the complex will be a large egg-shaped structure on top of the glass station house – usually referred to as the oculus -- that will act as a sunroof and reflect sunlight down to platform level.

The Right Answer?

While the existing subways stations needed work, Nicole Gelinas, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, contends that the Fulton Street Transit Center designed after 9/11 will not address the transportation problems in the area, namely the lack of direct connections to residential areas outside of the city. In her view, the entire project was the result of a rush to rebuild the downtown area after the 9/11 attacks.

"There was kind of this big focus that we have to rush to concentrate on the World Trade Center site, and maybe they should have done more to help the region," said Gelinas. "It may have been better for them to spend on actual rail connections."

According to Gelinas, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver played a big role into making the Fulton Street Transit Center a reality, the transit center being in his district. The speaker's office declined to respond.

"A lot of the rebuilding has been driven by local politics. Sheldon Silver really pushed this as one of the projects he's really been instrumental for," said Gelinas. "He made it clear in the months after 9/11 he wanted this transit center in lower Manhattan and to get funding for other projects, they [the MTA] supported this."

Designs and Delays

Groundbreaking on the transit center took place in June 2005, with completion originally slated for 2007. Cost overruns, though, started to become a problem in 2006, mainly due to the expense of relocating businesses on the site and acquiring property. In 2008, the MTA indicated that it might have to abandon the dome structure, which was the centerpiece of the project, and that there might not be any visible above ground structure. By this time, the project was slated to be done in 2010, and was $111 million over its original $799 million budget.

After reviewing and revising plans in, the MTA announced in 2009 the new completion date as June 2014, and the revised cost as $1.4 billion. Despite the federal government's refusal to pay for any cost overruns, the MTA received $423 million in stimulus funds to help continue the construction of the project. To keep costs from rising further, it was decided to narrow the Dey Street Passage from 40 feet to 29 feet. After going back and forth on the design of the Fulton Street station, the MTA is constructing the dome as originally planned, but with additional 23,000 square feet of retail space; to increase potential revenue for the project.

Some delays were attributed to engineering challenges in the area, including the reconstruction of the nearby Corbin Building, which will be 124 years old when construction is complete. Meanwhile the World Trade Center transportation center has also had its share of problems. The cost for the building – with its birdlike design by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava – could reach $3.8 billion and may not open until 2015.

According to the MTA, the Fulton Street project will cost roughly $1.4 billion, with 97 percent of that covered by federal funds. And now, according to Donovan, the transit center is being opened in sequence, with expected completion in June of 2014.

Zupan cites the complexity of the Fulton Street project as a key factor in the delays there, but he said the woes will be a distant memory once the general public sees the completed center.

"It's clear they've had problems moving forward, they had to redesign it to reduce cost. With many of these infrastructure projects they're very complex ... and it's very difficult to assess these things in advance," said Zupan. "When the project is done, it's going to last for 100 years, and it'll long be forgotten that the project is over budget and it took as long as it took."