A Vanishing Culture?

Image by Snohetta, (c) LMDC

Cultural institutions figured heavily in early plans for development of the World Trade Center site. The blueprint called for four independent cultural institutions that would complement the Memorial Museum, which will be dedicated to the 9-11 attacks.

But then an array of complications arose, including a heated debate over what kind of art would be “appropriate" on the ground where the Twin Towers fell. Now, as the seventh anniversary of 9-11 approaches, only one of the originally slated cultural institutions -- the Joyce Theater -- still hopes to locate at the site and even those plans are in jeopardy. Along the way, the saga eliminated one arts institution before it ever existed and left another without a home in Lower Manhattan.

Under Scrutiny

After officials made it clear that art would be an integral part of the plan to rebuild lower Manhattan, 113 cultural institutions applied to occupy the new buildings on Ground Zero. Four were selected in 2004.

The International Freedom Center, an institution imagined specifically for the site, and the Drawing Center, an established art museum, were to occupy a new Cultural Building next to the 9-11 Memorial Museum.

Now, neither arts venue will play a part in the site, nor will the Freedom Center ever exist. Their would-be home, a building designed by the Norwegian firm Snohetta, has been entirely scrapped. Instead, the firm has designed the entryway to the Memorial Museum.

"Originally there was a building that was going to house them and that was removed," Michelle Breslauer, a spokesman for the Memorial Museum, said.

The space that would have been devoted to that building will now be integrated into the memorial park as extra public space, according to the Lower Manhattan Development Corp.

The other arts building at the site -- a performance space designed by Frank Gehry -- sits in limbo, with funding in doubt and plans delayed for years, if not forever.

What happened?

Politically Incorrect?

The controversy over the arts institutions began with an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal by Debra Burlingame, whose brother had been the pilot of the plane hijacked and flown into the Pentagon on 9/11. She came out strongly against the International Freedom Center, which she saw as inappropriate for the site. In particular, Burlingame objected to the center's plan to present an exhibition on the struggles of freedom throughout history.

"The public will have come to see 9/11 but will be given a high-tech, multimedia tutorial about man's inhumanity to man, from Native American genocide to the lynchings and cross-burnings of the Jim Crow South, from the Third Reich's Final Solution to the Soviet gulags and beyond," she wrote. "This is a history all should know and learn, but dispensing it over the ashes of Ground Zero is like creating a Museum of Tolerance over the sunken graves of the USS Arizona."

What followed was a public debate on what art is appropriate for Ground Zero. A group called Take Back the Memorial -- with Burlingame on the board -- was formed to pressure then Gov. George Pataki to revise the plans. The Post and the Daily News weighed in against the Freedom Center as well.

In response, Pataki demanded an "absolute guarantee" that the Drawing Center and the Freedom Center would have "total respect for the sanctity of the site." At that point, the Drawing Center withdrew from the project.

"We really just decided it wasn't the right site for us," said Lisa Gold, the public relations and marketing director for the Drawing Center. "It got to be very complicated and we saw that we're better off in an autonomous location. There were a lot of different parties weighing in on what should and shouldn't be shown there, and we're independent we're just better off in our own space, programming our own content."

Then, in 2005, as the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation was still deliberating on how to proceed, Pataki unilaterally eliminated the Freedom Center from the plans.

While his choice mollified those offended by the Freedom Center's proposed content, Pataki faced heated criticism for his action. Two World Trade Center Memorial Foundation board members resigned in protest. Some critics charged he was curbing public debate and setting back the rebuilding process.

Since it was designed specifically for the site, plans for the Freedom Center will never be realized. Its planners expressed "deep disappointment" after the decision, calling it a "setback to one of the most ambitious and promising service and civic engagement programs in this country."

The High Cost of Art

The plans also called for a performing arts center designed by Frank Gehry's company. Initially, the Joyce Theater, a dance venue, and the Signature Theater Company, which features plays, were slated to share that building. Both are located elsewhere in the city and wanted to expand into Lower Manhattan.

Last year, the Signature left. In this case, the problem was logistics. According to the Times, the Bloomberg administration determined that having two institutions share the space was driving up costs and creating logistical problems. When the city offered to move the Signature into another location in the area, the company accepted without hard feelings.

The prospect for any performing arts center, though, remains somewhat vague. Discussing the Gehry building, the World Trade Center Web site, run by developer Larry Silverstein's company, said, "Funding details for the project have yet to be worked out, and construction cannot start until 2010 or 2011 because the site will be occupied until then by a temporary exit from the PATH train."

The city had said it would raise money for the center -- but not until the memorial and museum managed to amass $350 million needed for that project. Now that goal has been met, but as Downtown Express reported in April, there is no indication the city government is seeking support for the performing arts building. "

Meanwhile, Avi Schick, chief executive of the Empire State Development Corporation, has proposed -- in what he said was just an " idea or a concept" -- moving the performing arts center from the trade center site to the land above the subway station now being built at Fulton Street and Broadway.

Kate Levin, commissioner of the city Department of Cultural Affairs, has said the city and Lower Manhattan Development Corp. are working on a feasibility study for the theater, but there is no indication of when it will be completed.

"The performing arts center continues to be put on the back burner, and that's a huge mistake," Julie Menin, chairperson of Community Board 1 told Downtown Express.

The revised plans for the entire site, due to be presented to Gov. David Paterson later this month, could provide further indication of whether rebuilding officials think arts still have a place at Ground Zero.

Searching for a Space in Lower Manhattan

When the Drawing Center withdrew from the project amid concerns over content control, it was left without a home in Lower Manhattan. But administrators still feel they made the right decision.

"We're still looking for a space in Lower Manhattan," said Gold. "We looked at additional sites down by the seaport, and we're continuing to look. New York is a very complicated real estate market. It's hard."

According to Gold and others in the arts world, space has been a major problem for cultural institutions in Manhattan. Many have the means to grow but can't find a place to do it. And arts advocates said that because of the economy, many cultural groups are facing greater fiscal pressures in recent days, making it hard even for successful institutions to afford Manhattan real estate.

The Drawing Center wanted to be at the trade center site not because of some specific link to 9/11, but because they valued the location. Its decision to withdraw is looking even wiser as the rebuilding process remains complicated and slow.

"We weren't specifically wed to that site because of what its holds," Gold said. "It was a wonderful opportunity that turned out not to be such a great opportunity. I don't think we're giving up anything by not being there."

As for Signature, the city proposed that it move to a space planned for the site of Fiterman Hall, the Borough of Manhattan Community College building currently undergoing decontamination. That sites future, like so much near ground zero, also remains in doubt.

Signature, though, thinks the move away from the trade center site still makes sense.

"The city said it was going to be too costly to do it, and I think they're right," said James Houghton, artistic director of the Signature, told the Times last year. "Frankly, it's refreshing to get this straight talk about it. I don't think anyone wants to build a $700 million performing arts center."

Â

Harlem's Shifting Population

This is the text version of the chart included in An Affluent, White Harlem?

Townhouses in Harlem sell for millions of dollars and Columbia University continues to expand there, as the city foresees even greater changes again. Andrew Beveridge examines what it could mean for the future of America's most famous black community.

| Central Harlem | Greater Harlem | Rest of NYC | |

|

* Numbers do not add up to 100 percent. The remaining Harlem residents are HIspanics, who were not listed separately until 1980, and individuals who identified themselves as members of other racial groups. |

|||

|

Sources: 1910 to 1940, Census Tract Data from National Historical Geographical Information System, Compiled by Andrew A. Beveridge and Co-workers; 1950, Ellen M. Bogue File, as edited by Andrew A. Beveridge and co-workers; 1960 through 2000, Tabulated Census Data from National Historical Geographic Information System; 2006 Data from American Community Survey, U.S. Bureau of the Census. Boundary Files from National Historical Geographic Information System 1910 to 2000, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2006. All data and boundary files available from Minnesota Population Center. Since results are tabulated from the sources indicated, they may not necessarily match Census published figures for population and race. |

|||

| 1910 | |||

| BLACK | 9.89% | 4.28% | 1.73% |

| WHITE | 90.01% | 95.64% | 98.12% |

| total population | 181,949 | 593,598 | 3,191,961.84 |

| 1920 | |||

| BLACK | 32.43% | 12.28% | 1.46% |

| WHITE | 67.47% | 87.60% | 98.39% |

| total population | 216,026 | 652,529 | 4,767,727 |

| 1930 | |||

| BLACK | 70.18% | 34.82% | 1.99% |

| WHITE | 29.43% | 64.78% | 97.80% |

| total population | 209,663.38 | 580,277.29 | 6,168,983.97 |

| 1940 | |||

| BLACK | 89.31% | 48.32% | 2.65% |

| WHITE | 10.48% | 51.38% | 97.10% |

| total population | 221,974.31 | 576,845.91 | 6,677,186.53 |

| 1950 | |||

| BLACK | 98.07% | 57.52% | 5.64% |

| WHITE | 1.76% | 41.89% | 94.03% |

| total population | 237,467.79 | 593,246.28 | 7,078,649.58 |

| 1960 | |||

| BLACK | 96.71% | 58.53% | 10.71% |

| WHITE | 2.94% | 40.55% | 88.62% |

| total population | 163,632.28 | 467,633.59 | 6,829,199.34 |

| 1970 | |||

| BLACK | 95.42% | 63.53% | 18.48% |

| WHITE | 4.28% | 34.44% | 79.82% |

| total population | 157,178.07 | 430,567.1 | 7,083,454.85 |

| 1980 | |||

| BLACK | 94.17% | 58.76% | 22.20% |

| WHITE | 0.62% | 10.29% | 53.98% |

| total population | 108,236 | 339,490 | 6,732,149 |

| 1990 | |||

| BLACK | 87.55% | 52.37% | 23.93% |

| WHITE | 1.50% | 10.85% | 44.74% |

| total population | 101,026 | 334,076 | 6,988,199 |

| 2000 | |||

| BLACK | 77.49% | 46.03% | 23.67% |

| WHITE | 2.07% | 10.45% | 36.11% |

| total population | 109,091 | 354,057 | 7,654,221 |

| 2006 | |||

| BLACK | 69.27% | 40.54% | 23.40% |

| WHITE | 6.55% | 14.80% | 36.06% |

| total population | 118,111 | 374,854 | 7,838,724 |

Â

An Affluent, White Harlem?

Photo (c) Roger Smith, LOC

Harlem street scene, 1943.

Lenox Terrace, where U.S. Rep Charles Rangel had four apartments, now qualifies as a luxury building. Townhouses in Harlem sell for one, two and even more million dollars, as real estate developers build new condos in Hamilton Heights and elsewhere, Meanwhile Columbia University arranges to get much of West Harlem declared blighted so its expansion in Harlem, past the Fairway grocery store and Dinosaur Barbecue, can march on.

With the recent city rezoning of the area (see related story), many residents fear they will be pushed aside by new development. What is happening to Harlem? Is it becoming white? Is it becoming a neighborhood for the rich?

Harlem has gone through many changes since 1910. How far the latest transformation will go, though, remains to be seen.

As with many New York neighborhoods, defining Harlem's boundaries can be difficult. Central Harlem follows the definition set out by Gilbert Osofsky in his 1966 book Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto. The southern edge starts at 96th Street on the East Side; at Fifth Avenue and Central Park it goes up to 110th, and then cuts over to 106th Street on the West Side. The northern boundary of the area in most places is 155th Street, though it extends a bit further up on the East Side. Central Harlem is basically north of Central Park and east of Morningside and St. Nicholas avenues.

Prior to 1910, most of Harlem's settlers were middle class, including many notable African Americans. In the 1920s, an efflorescence of culture known as the Harlem Renaissance occurred, and the Apollo Theatre and the Savoy Ball Room were founded. As the "great migration" of blacks from the American South continued, and the size of the black population expanded, an area of concentrated poverty developed. Kenneth Clark's 1996 book, Dark Ghetto, certainly was influenced by Harlem.

Click on the image for full graph or view a text version here.

The changes in Central Harlem and New York City are shown in the table. In 1910, Central Harlem was about 10 percent black, Greater Harlem was a little more than 4 percent black, while the rest of New York City was less than 2 percent black. By 1930, Central Harlem was over 70 percent black and Greater Harlem was about 35 percent black, but the rest of New York City was still less than 2 percent black. In short, by 1930, during the Harlem Renaissance, Central Harlem had become very definably black area in a largely white city. By 1950, Central Harlem was about 98 percent black, while Greater Harlem was 57.5 percent black.

Central Harlem lost more than half of its population between 1950 and 1980, and Greater Harlem also saw its population drop as well. This was a period of sharp economic decline in New York City, especially for the black community. This also marked the era of urban renewal, and many older housing units were razed either for public housing projects or for other apartment developments. The new developments did not come close to housing the same number of people. Almost all of the people who remained in Central Harlem, though, were black.

Since1980, Central Harlem has become less black, and by 2006 a smaller percentage of the population was black than in 1930. Meanwhile, the white and Hispanic populations rose. In 1980, there were 672 whites in Central Harlem, constituting about 0.6 percent of the population. By 2006 that figure had increased to 7,741 or about 6.6 percent. Hispanics accounted for 4.3 percent of Harlem residents in 1980, the first year they were classified separately. In 2006,that number reached 18.6 percent.

In short, there had been a turnaround of sorts in Harlem. The white population that had moved to Harlem by 2000 was distributed in many different areas. Between 1980 and 2000, there has been a decline in the concentration of blacks in Harlem. Furthermore, according to the 2006 American Community Survey, the overall decline in black population has continued.

In the early days of Harlem, the black community there was quite diverse, especially when African Americans in Harlem were compared to those who lived elsewhere. During the period of the rapid influx into the area, the level of concentrated poverty increased in Harlem. That accelerated during the 1950s through the 1970s with urban renewal, housing deterioration and a decline in population. At the same time, areas such as Southeast Queens attracted affluent black families.

Now it appears that areas of Harlem are sought after once again. By 2000 and 2006, there were areas of some highly affluent black and white residents. Median household income in Central Harlem had increased from about $13,765 in 1950 to over $26,161 in 2006, in 2006 dollars. Still, this figure is well below the median of $46,285 for the rest of New York City.

Harlem has changed from an impoverished area with a few middle-class families to one where some middle-class people, including a few whites, have moved in and made their homes. In some parts of Harlem, blacks have been joined by Hispanics, but that percentage has not grown much since 2000. Rather, the new residents of Harlem seem to be non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic, who consider themselves to be "other race," neither black nor white. The traditional townhouse areas around Strivers Row, Sugar Hill and Marcus Garvey Park have undergone a rebirth. Stores and restaurants catering to the affluent have opened in West Harlem, while Magic Johnson opened a Starbucks and a Multiplex on 125th Street, near where former President Bill Clinton has his office suite. Columbia University's expansion will bring more change to West Harlem.

What these changes portend for New York City's iconic black neighborhood is hard to fathom. On the one hand, new residents mean that Harlem will have more diversity of income, occupation, educational level and race than it did in the 1970s and 1980s. At the same time, the large stock of public housing and the relatively low income means that high levels of poverty will continue to be a feature of Harlem. Harlem will not lose its black majority or its high concentrations of poverty anytime soon.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.ÂThe School Divide Starts at Kindergarten

The recent baby boom in New York City led to an increasing squeeze in the search for the best school for the budding kindergartner or first grader. Unlike other recent spurts in enrollment, the latest surge has had the great effect in Manhattan, especially among highly affluent non-Hispanic white families

The number of white toddlers (ages 0 to 4) in the city has increased greatly. In decades past, white families and more affluent families would often leave New York City for the suburbs, where the schools were small and elite (at least according to who lived there) and open to all residents. Now more of these families prefer to stay in New York City.

The impacts of the new trend are reverberating throughout New York City's elementary schools -- public and private, elite and neighborhood. One of the city's top elementary schools, Hunter, saw 1,550 children apply for 48 slots. The large increase in students sitting for the private school exams document that this is indeed the year of the crunch.

Many affluent parents have seen public school Gifted and Talented programs as a viable - and free -- alternative to private schools, but critics have long maintained the system unfairly favored these children, shortchanging those in poorer black and Hispanic areas. This year the city adopted a standardized test with uniform standards to select those eligible. However, we now know that this method resulted in a much less diverse program according to the New York Times.

Finally, just getting ones child into a neighborhood school seems to have turned into a difficult process for some. Confusion, competition for limited slots and changes in the selection methods for the relatively few desirable elementary programs seem to be the order of the day.

Who Goes Where

Which kids go to public schools and which attend private schools in New York City? Which get into the sought after programs, such as Hunter or the Gifted and Talented programs? What do we know about the location, race, ethnicity and economic standings of the families of New York City's elementary school parents, public and private, gifted and not so gifted?

To answer some of these questions I pieced together data from the Census and the Department of Education, and created some simple maps. Beyond this, using some estimates based upon reasonable guesses of the test outcomes, I was able to get some idea of the composition of the Gifted and Talented programs. Simply put, the kids who find their way into the preferred programs, whether public or private are much different than the average New York City elementary kid. They are much more likely to be from intact, higher income families and to be non-Hispanic white.

Private School Kids are Different

Now that Gossip Girl is on TV, and Horace Mann's violations of academic and due process have been exposed by New York Magazine, outsiders may sense that private school kids are different from public school kids, at least in high school. Of course, most private schools are not at the rarefied financial and academic levels of Collegiate, Brearley, Spence, Horace Mann, Ethical Culture and the like. Indeed, the vast bulk of private schools in New York City are run by the two Catholic archdioceses, while there are yeshivas, along with a few Lutheran, Muslim and other religious schools.

In 2006 about 22 percent of 518,000 elementary students (kindergarten through grade 4) attended private school according to the census's American Community Survey. Table 1 compares the elementary private school kids with those attending public school.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Only about 17 percent of the public school kids are non-Hispanic white, compared with about 57 percent of the private school kids. The private school kids are also less likely to be Hispanic, black or Asian than public school kids. While about 79 percent of kids in private school come from married couple families, only half the public school kids do. The median family income of the private school kids is $63,000 almost double that of public school kids with $33,750. Most of those parents who chose private schools for the children are willing and able to pay the tuition. Many, many public school families never could.

Map 1 presents the percent of elementary children by sub-borough (which follow the boundaries of community planning districts, except that two in lower Manhattan and two in the Bronx are combined.) As that map makes plain, in the Upper East Side of Manhattan (the home Gossip Girl) more than half of all elementary kids attend private school. This percentage is quite high in other parts of Manhattan, as well, including the Upper West Side and midtown and downtown. It is in exactly in these areas that the baby boom for non-Hispanic whites has occurred in the last few years.

In Brooklyn, the percent of children attending private school is especially high in Williamsburgh and Greenpoint, as well as in Borough Park. Here, of course, there is a high concentration of observant Jewish parents, Also in Brooklyn, the area including Sheepshead Bay has relatively high private school enrollment. Private schools, even the religious ones, cater to the parents with some means and enrollment is concentrated in those areas.

Deciding Who's Gifted

The rejiggered selection criteria for slots in New York City's Gifted and Talented program, requires taking a test, usually in kindergarten, and scoring in the 90th percentile. Students who clear this hurdle are likely be from non-Hispanic white families and from affluent families. Many of their parents can afford pre-school, lessons, nannies and the like. When their children take a test, even at age four or five, they are prepared and have a huge advantage over other students.

The Department of Education has not released full data about the racial and Hispanic composition, as well as the eligibility status for "free or reduced lunch program," of the admitted students. What we do know is that the number of students qualifying for gifted and talented slots radically changed for many districts between last year and this year. This year District 2 in a large swath of Manhattan had 15.2 percent of its students qualifying, while District 3, on the Upper West Side, qualified 22.3 percent. Most districts were well below 5 percent. Map 2 gives the overall rate of gifted and talented students qualified compared to the total in the cohort. These figures include all students who would be eligible for the first time for Gifted and Talented programs this year, whether or not they applied.

The percent of non-Hispanic whites and the percent not qualifying for free and reduced lunch is highly correlated with percent qualifying for Gifted and Talented programs. Using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study of Kindergarten, I found that non-Hispanic whites are much more likely than non-Hispanic blacks or Hispanics to score in the 90th percentile or above on a cognitive test. Their performance does vary by which test -- math, language or general knowledge -- is being used.

Since New York City now uses similar tests to screen for gifted and talented, I assumed that non-Hispanic whites would outperform Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks, and would have a 150 percent greater chance to meet the cutoff for the Gifted and Talented classes. For 100 non-Hispanic blacks and 100 non-Hispanic whites, this means that if 10 non-Hispanic whites meet the cutoff only two non-Hispanic blacks would do.

Performance on tests taken at kindergarten is highly influenced by the student's family environment of the student. This means the actual difference between white students and other may be even greater in New York City, where there are very high differences in income and education between non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites, especially in Manhattan.

The results of the estimates are shown in Table 2.

|

|||||||||||||||

Non-Hispanic whites and Asians almost triple their percentage, while the percent non-Hispanic black and Hispanic plunges. In short, students accepted in the Gifted and Talented program are not all representative of the students in New York City, and less so this year than last year.

As the baby boom in Manhattan shows little sign of ebbing, we can expect the middle class kindergarten crunch to continue. Parents here can chose between many types of private and religious schools, selective schools, their neighborhood elementary school or gifted and talented program. But the suburbs are just a short train ride away, and many have lots of slots for new elementary school students available to anyone who can afford to live there.

Â

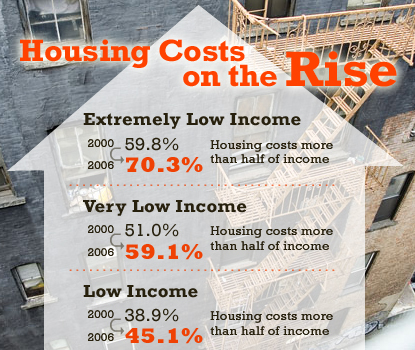

Housing Squeeze Shows No Sign of Easing

To anyone look for an apartment in New York's City "free market," affordable housing can seem to be an oxymoron. While a well-known real-estate developer recently claimed that any housing rented or sold in New York City was affordable to the particular renter or purchaser, when the usual standards are applied many New Yorkers live in unaffordable conditions.

Generally, affordable means spending no more than 30 percent of household income on housing. For a household with an income of $100,000, affordable housing then would mean rent, utilities and other charges (but not phone and cable) or mortgage, maintenance and utilities would amount to no more than $2,775 per month. For New Yorkers at 80 percent of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development median ($56,570), which the department considers the top of lower income, the figure would be about $1,575.

U.S. Rep. Anthony Weiner’s recent report that 28 percent of New York households who rent spend more than half their incomes on housing and his call for increased federal subsidies, public housing and other government measures served as yet another reminder of the severe problems of housing affordability in New York City and the lack of government action to remedy it.

In 2000, 36.7 percent of New Yorkers lived in unaffordable units. By 2006, that the percentage had increased to 46.0 percent, which means that about 280,000 more New York City households now live in non-affordable housing than they did eight years ago. An analysis by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development using the 2000 Census showed that one fifth of New York City households then spent more than half of their income on income. By 2006 that had increase to almost one quarter. (More results are in the accompanying table below.)

An analysis of American Community Survey data shows that paying for housing poses an increasing burden on less affluent New Yorkers. The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development defines extremely low-income households as those with incomes of less than $21,251 for a family of four; very low income as families of four making less than $35,419; and low income families as those with incomes of below $56,760 for a four-person household. Click on image for full table.

These results were produced using the latest available American Community Survey data. I performed the same analysis that HUD had done for the 2000 Census. Of those New York households classified as low income, 71.9 percent lived in unaffordable housing, an increase from increased from 62.6 percent in 2000. The number of these less affluent households spending more than 50 percent increased from 38.9 percent to 45.1 percent during the same period. (The accompanying table has more detail.)

This can be attributed to a number of developments. The median house value almost doubled from 2000 to 2006, and many people stretched their budgets to buy in what they saw as a booming market. Rents at complexes such as Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village were increased to luxury levels, while many buildings left Mitchell-Lama moderate-income housing program. Meanwhile, it was reported last week that private companies are buying up inexpensive apartments in the hopes of converting them to higher priced buildings once the current tenants leave. With fewer and fewer rent-regulated apartments available, it is no surprise that an affordable apartment in New York City is becoming scarcer and scarcer.

The mayor's PlaNYC2030 for sustainable growth acknowledges the affordable housing issue. The plan expects a net increase of about 300,000 homes to accommodate the growth of the population from 2005 through 2030. To accommodate the housing needs, it outlines a series of steps, including a large number of residential “upzonings” to make it possible to build higher density housing than is now permitted in many areas in the city, housing within easy access to transit and an effort to create and preserve affordable housing using city land, subsidies, and incentives.

This is not the mayor's first attempt to address the housing crunch. The results from New Housing Marketplace to promote moderately priced homes brings into high relief just how difficult it is to make housing more affordable here. That plan calls for 165,000 units of affordable housing: about 73,000 preserved and about 92,000 newly constructed. After four years, the Independent Budget Office found that about 40,000 units were preserved and 24,000 units were new. At the same time, the city lost 280,000 affordable apartments and houses in the last six years. The challenge, according to the Independent Budget Office, is to build new homes affordable to low and moderate income households, as well as to middle-income households.

Unfortunately, Weiner is right. To create affordable housing requires subsidies and funding on a scale undreamed of since before the Reagan administration. The reason for this is obvious. Those most in need of affordable housing, cannot afford market rate housing. Yet, one can go only so far to use market rate housing to subsidize lower priced rate housing.

Density bonuses, set asides, 80/20 arrangements, etc., do help. But New York City need more than 1 million more affordable units along with significant efforts to make sure that the recent losses do not continue. There is little chance that the city, state or federal government will be willing to pay the bill for that. In the meantime, the search for affordable housing in New York will become more and more difficult, and more residents will abandon the search and move elsewhere or not even bother to come here.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

A Religious City

When commentators discuss parts of the country where people hold strongly to religious beliefs and practices, they rarely include New York. In fact, for much of its history, people from the rest of the U.S. have tended to view the city as a godless metropolis in a largely god-fearing land.

The statistics, though, tell a very different story. If belonging to a religion translates to being religious, New Yorkers are very religious when compared to Americans as a whole. The proportion of people identified as adhering to an organized religion in New York City makes the five boroughs as religious as many places in the so-called "Bible Belt." Yet people here belong - and do not belong - to different religions than residents of other parts of the country.

An estimated 6.8 million New Yorkers - or more than 83 percent of the population -- were identified as being affiliated with some organized religion in 2000. This rate of adherents is higher than all the states except Louisiana - even slightly higher than Utah. (These numbers include those who were said to be affiliated with many different religious groups and were adjusted to take into account non-reporting and other factors.)

Since 1990, though, there seems to be some decline in religious affiliation in New York City. In 2000, three-fifths of all New Yorkers were reported as affiliated with one or another religious body and so were called religious "adherents." The number was down to 4.8 million from just over 5 million in 1990. (These are the unadjusted figures.)

| New York City | New York State | United States | |

| All Religions (adjusted) | |||

| Adherents | 6,682,139 | 14,366,781 | 173,046,520 |

| Rate | 83.44 | 75.71 | 61.49 |

| All Religions (Unadjusted) | |||

| Adherents | 4,783,779 | 11,459,836 | 141,364,420 |

| Adherence Rate | 59.74 | 60.39 | 50.23 |

The data used here are from the Religious Congregations and Membership Survey sponsored by the Association of Statisticians of Religious Bodies and distributed by the Association of Religious Data Archives. These data ask representatives of each congregation for the number of members they serve. Data on religious adherents was released February 1 and are available through www.socialexplorer.com Social Explorer and from the www.thearda.com Association of Religious Data Archives.

| Brooklyn | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | Bronx | |

| All Religions (adjusted) | |||||

| Adherents | 2,359,578 | 1,374,628 | 1,411,006 | 396,026 | 1,140,902 |

| Adherence Rate | 95.71 | 89.42 | 63.29 | 89.25 | 85.61 |

| All Religions (unadjusted) | |||||

| Adherents | 1,552,336 | 1,075,375 | 1,072,693 | 332,964 | 750,411 |

| Adherence Rate | 62.97 | 69.96 | 48.12 | 75.04 | 56.31 |

Looking at the whole metropolitan area, which includes 39 counties in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, as well as Pike County, Pennsylvania, almost 79 percent of the population are adherents, making the metro area 31st out of 276 in terms of religious affiliation. Virtually all the metropolitan areas reporting a higher proportion are in the South, including Lafayette, Louisiana, with the New York City area having a higher proportion of adherents than the Salt Lake City or Little Rock area.

Furthermore, New York State is the fifth most religious state. Only Louisiana, Mississippi, Utah and North Dakota have a higher proportion of religious adherents.

At the other end of the scale, West Virginia, Maine, Nevada, Washington and Oregon have the smallest percentage of their populations identified as belonging to an organized religion. Between 35 percent and 40 percent of their residents are adherents, compared to New York State's 75 percent. Metropolitan areas in those states have similarly low rates of religious membership.

A Diversity of Faiths

Religious though New York City may be, its mix of religious, as with its mix of residents, differs greatly from the rest of the United States. New York City is much more Catholic (62 percent versus 44 percent) and much more Jewish (22 percent versus 4.3 percent) than is the rest of the United States.

While smaller in number, Muslims and members of various Eastern Orthodox churches also have more members proportionately in New York City than in the state or the country. For example, slightly more than 2 percent of New Yorkers attend mosques, compared to only about a half of 1 percent of all Americans.

Protestants are much less well represented among New York City's religious members. In New York City 4.2 percent of religious adherents belong to evangelical Protestant churches and 6.5 to mainline Protestant churches, compared to 28.2 percent and 18.5 percent, respectively, for the nation as a whole

The pattern of religions varies throughout the city. Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn have a higher proportion of Jews and Muslims, while Staten Island and the Bronx are much more Catholic. Manhattan has the highest proportion of mainline Protestants, while Brooklyn leads in terms of Evangelical Protestants.

| Brooklyn | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | Bronx | |

| Catholics | 58.8% | 52.5% | 60.0% | 79.6% | 77.5% |

| Evangelical Protestant | 5.5% | 3.0% | 3.9% | 2.8% | 4.2% |

| Mainline Protestant | 6.6% | 9.3% | 5.7% | 4.3% | 4.7% |

| Jewish | 24.4% | 29.2% | 22.2% | 10.1% | 11.2% |

| Muslim | 3.7% | 3.4% | 4.9% | 2.4% | 1.6% |

| Eastern Orthodox | 0.7% | 1.8% | 2.7% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| Other Religions | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

Measuring Religion

The data presented here represent one method of measuring religion in the United States. Other measures, such as the American Religious Identification Survey estimate religion by asking individuals their religious identification.

Both approaches to measuring religion have some biases. However, the general patterns found seem to be the same. Both identify New York City and State as quite religious and the Pacific Northwest to be much less so. They also corroborate one another in terms of the patterns of religion identification and membership in the city. In the s religious identification survey, taken in 2001, about 13.4 percent of New York State residents did not identify with any religion. Estimating the number of people affiliated with any religion, though, particularly for Muslims and Jews, poses difficulties. The Census does not ask people about their religious affiliation.

To look at the figures for about 150 religious denominations by county and state, go to www.thearda.com or to www.socialexplorer.com A book was recently published that presented much more detail from the ARIS: Religion in a Free Market. Further analysis of data similar to that presented here can be found in The Churching of America, 1776 to 2005.

| New York City | New York State | United States | |

| % of Adherents By Group | |||

| Catholics | 62.0% | 65.9% | 43.9% |

| Evangelical Protestant | 4.2% | 4.9% | 28.2% |

| Mainline Protestant | 6.5% | 11.3% | 18.5% |

| Jewish | 21.9% | 14.4% | 4.3% |

| Muslim | 3.5% | 2.0% | 1.1% |

| Eastern Orthodox | 1.4% | 1.0% | 0.7% |

| Other Religions | 0.4% | 0.5% | 3.2% |

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Will the 2010 Census "Steal" New Yorkers?

Throughout the 1990s, New York City's population appeared to grow from about 7.35 million until it reached slightly over 8.0 million for the first time ever. Since then, growth continued, and by 2006 New York City was said to have somewhat in excess of 8.2 million people. As preparations ramp up for the 2010 Census, most would expect that that count will register New York City's continued gains. Yet when the Census numbers are announced, New York City's renewed growth could appear to have halted and even reversed -- not because fewer people actually live here but because of new Census procedures.

Censuses, including the ones in the United States, are really about two things: power and money. The main use of the count is to reapportion Congress and redraw lines for the state legislature and local government bodies. Simply put, every extra person in New York City (and by extension New York State) leads to extra power for the state and the city, and to additional government funds.

The growth in largely Democratic New York City in 1990s, as depicted by the Census, along with declines in population in more Republican areas upstate, led to a serious problem for the GOP-dominated State Senate. Instead of simply shifting some seats from Republican areas to Democratic ones, as the Census would seem to have indicated, the Senate tried to instead solve its dilemma by adding an extra seat to the body and forcing massive redrawing of lines in New York City, while keeping them largely intact in Long Island and upstate.

Counting More New Yorkers

While more people did live in New York City 2000 than in 1990, a large share of the growth in population recorded by the 2000 Census is due to the efforts of the Population Division of the Department of City Planning and its director Joseph Salvo. Indeed, perhaps half the growth can be attributed to their efforts to include formerly overlooked households in the Census and make sure they were counted. Some of these households were never reached, so the data on them came from their neighbors, with the Census Bureau filling in some of the blanks. Now the bureau headquarters in Washington is challenging the methods and approaches that led to New York City's surprising growth. In effect, it claims, some of the households counted do not actually exist.

For the 2000 count, the Census Bureau allowed local authorities to examine and update the local address file and add the following types of units:

- New construction

- Conversions of buildings from non-residential to residential use

- Garages converted to residences

- Attics or basements used as apartments

- Subdividing that yields apartments

The city planning department counted both doorbells and mailboxes to try to assess the many different types of conversions that had taken place. Many of these homes, of course, are illegal and do not have an official Certificate of Occupancy. Nonetheless, many people live in such apartments and should be counted. In 2000, the planning department suggested the addition of 439,069 additional housing units. The Census Bureau eventually accepted about 370,000 of these residences, including about 86,000 after an appeal by the city. The homes from the appeal alone would have added on the order of 200,000 to 250,000 New Yorkers to the Census.

Since 1960, the census has sent long forms, requesting more detailed information, to a certain percentage of homes. The 2010 Census will no longer have a long form. The questions that formerly were part of the "long form, are now administered yearly in the American Community Survey, which began in 2005 and first was released in 2006.

Beyond that change, the planning for the 2010 Census includes a much more restrictive definition of what constitutes a household. Indeed, Census staff suggests that if there is any question about how many units are in a given structure they will consult with the property owner, who very likely may have illegally divided it, to find out how many unites are "actually" in the building. Some landlords, of course, will be loathe to report their illegal units, and will deny their existence. Furthermore, there seem to be plans to send only one form to each address, even though there are many instances where two households share a mailbox. If these procedures are put into place, New York City could very well lose hundreds of thousands of population in the 2010 Census Count.

An Alternative Plan

Joseph Salvo suggests that the Census use a method called update and enumerate. In that method, questionnaires are not mailed. Instead Census workers walk blocks with a list of addresses in hand, knock on doors, update addresses and count residents. This method is used in other places, such as resorts and Native American reservations, where it is difficult to ascertain the number of households in a given area. In sections of Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx, where there are many households and residents in some structures, such a method done properly would lead to a more accurate count than mailing forms.

The 2010 Census will be used for reapportionment and redistricting and population estimates, as well as providing the basis for all population reporting for the community survey in the coming decade. As such, its accuracy is vital for New York City and the share of power and money it will have both in the United States and in the state.

Unless New York City's special characteristics are taken into account, it is plain that the city will be a loser in the 2010 Census, as it was for decades and decades until 2000. We are lucky to have Joseph Salvo and his Department of City Planning team as our advocates. Without them, New York City would have never officially reached the 8 million made and in 2010 could turn out to be below it once again.

(The discussion of LUCA in the 2000 and 2010 Census is drawn from Joseph Salvo's presentation to New York Chapter of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, September 27, 2007. That presentation is available on the Web site. My presentation on the results from the American Community Survey is available here. Any opinions expressed are mine and mine alone.) Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

The End of 'White Flight?'

Year after year, decade after decade, New York City was home to a rapidly changing and increasingly diverse population. Whites were seen as fleeing the five boroughs, while blacks, Hispanics and immigrants replaced them. At the same time, the median incomeof city family was barely growing and often declining. Now according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s huge 2006 American Community Survey, as well as the census’ own estimates, most of these trends seem to have ended. There even are signs that they may have been reversed:

Some highlights:

* The African American population is declining. The proportion of non-Hispanic African Americans dropped from 24.5 percent of the city’s population in 2000 to 23.7 percent in 2006. The number declined from 1,962,154 to 1,947,328.

* Hispanic growth has almost ceased. The proportion of Hispanics in New York barely grew from 27.0 percent in 2000 to 27.6 percent in 2006. In the last year for which estimates are available, the Hispanic population in the entire city increased by only 911people.

* The non-Hispanic white population is no longer declining. The proportion of Non-Hispanic whites declined from 51.9 percent of the population in 1980 to 35.0 percent in 2000 -- a drop of about 17 percent. From 2000 to 2006, the proportion dropped by only 0.2 percent.

* The increase in the number of foreign-born New Yorkers has slowed from a stream to a trickle. After rising from 18.2 percent of the population in 1970 to 35.9 percent in 2000, the percent of foreign-born grew only an additional 1.1 percent from 2000 to 2006.

. The Asian population continues to grow at a rapid pace. The proportion of Asians in New York City grew from about 19.6 percent to 23.3 percent and increased by over 350,000 in six years. This is one trend that continues.

* There remains little growth in income. In constant 2006 dollars, the median income of a New York City family was $53,105 in 1970. Since then, it has gone up and down a bit and in 2006 was $51,830. During the past 36 years, there has very little net change in median family income in New York City.

Reversing the Trends

The reversal of many long-standing demographics trend is particularly pronounced in Manhattan, as Table 1 shows. The proportion of foreign born, Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks all declined in the borough, while the percentage of non-Hispanic whites increased. But Manhattan differed from the rest of the city when it came to income. Rather than remaining stagnant, median family income there soared from about $61,000 in 2000 to $71,000 six years later.

The trends embody a shift in attitudes about the city. In the 1970s and 1980s, many middle-class people and whites left New York City, and even Manhattan was considered a “difficult” place to live. Now New York City -– particularly Manhattan -- is becoming a sought after venue, at least for those who can afford it.

For instance, in 2000 the median house value for all owner-occupied housing in Manhattan was $423,000. By 2006 it had risen to $787,000, an increase of 86 percent. In the city as a whole, the median value of homes occupied by their owners climbed from $259,000 in 2000 to $496,000 in 2006, an increase of 91 percent.

The increases in income and the declines in the percentage of foreign-born, black and Hispanic New Yorkers, particularly in Manhattan, seem to indicate that the people who have come to the city recently are more affluent than those who left or decided not to not come at all. More analysis will elucidate this.

The real question is whether the trends that shaped New York City for much of the latter half of the 20th century historic will reemerge, whether the trends will substantially reverse or whether the city will experience little change. In Manhattan the trends already have reversed, with the borough becoming increasingly white and affluent. The rest of the city could follow. This already seems to be the case in some “Manhattanesque” neighborhoods, such as Brooklyn Heights, Williamsburg and Astoria.

On the other hand, the recent changes may simply be the result of the recent boom in finance and real estate. If that boom ends, then the demographic change of the first years of the 21st century could simply represent a blip in the continued long-term trends. Or some other trend or trends may emerge.

Only the future will reveal the answer. But one thing is certain; the demographic and population changes in New York City will likely be both unexpected and fascinating.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Feeling the Effects of a Housing Bust

The soaring values of apartments and houses in the city gave many New Yorkers a major real estate obsession during the first part of this decade. After residential real estate prices took over a decade to climb back to their levels of 1987 (the beginning of the last real estate crash), property values began to soar in 2000 and continued their heady ascent until recently. Now, of course, real estate price increases are yesterday's news as buyers dry up, inventories of unsold properties mount, sub-prime mortgages readjust and foreclosures increase.

This fall in the housing market will have many effects in New York City. But some New Yorkers, particularly lower-income people, blacks and Hispanics, will feel more pain than others.

The End of the Boom

The 2000 census reported that the median property value was $258,966 (in 2006 dollars) for all owner occupied housing in New York City. By 2006 the value had risen to $496,400 an increase of $237,434 or 91.7 percent. By 2005, though, much of the escalation had run its course, and from 2005to 2006, the median increased by a mere $32,916 or 7.1 percent.

Meanwhile, according to U.S. Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke, losses from sub-prime mortgages (higher interest loans taken out by people who cannot qualify for conventional mortgages) have far exceeded "even the most pessimistic estimates."

These will probably mean pain for the New York City. As residential real estate prices decline, tax revenues will fall. Some residents will lose their homes, and others will be strained near the breaking point to pay their mortgages or will take advantage of various state and federal loan "stretch-out" or "work-out" provisions that have yet to be enacted.

The rise in housing prices was fueled by new mortgage products that allowed people to buy homes with no down payment upfront. Many of these loans did not require income verification. Then the mortgages were packaged and sold as securities to financial institutions. The failure of many people to repay their loans set off the recent credit crunch.

The Big Losers

What does the housing bubble and likely bust mean for New York City. Which residents are most affected?

For one, the credit crunch and its reverberations on Wall Street could ultimately affect the bonuses of Wall Street traders and brokers.

The effects, though, go far beyond that. New York City, despite many claims to the contrary, actively participated in the housing bubble of 2000 to 2006. Data from the Census Bureau’s 2006 American Community Survey, released on September 12, 2007 provides a view of the many ways that New Yorkers are vulnerable to any meltdown in real estate value and accompanying credit crisis in the mortgage industry.

In New York City in 2006, almost half of all those with mortgages spent more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs, including mortgage, taxes, insurance and utilities. More than one quarter paid over 50 percent. Of those who purchased homes with a mortgage in the last two years, half were paying at least 32 percent of their income for housing costs, and one quarter were paying 55 percent or more.

For Hispanics, African-Americans and Asians, the figures were even higher. Half of Hispanics paid at least 37 percent and one quarter spent 81 percent or more. Among non-Hispanic African Americans the figures were 44 percent and 71 percent, and for non-Hispanic Asians the figures were 38 and 63 percent. On the other hand, for non-Hispanic whites half were paying at least 24 percent and one quarter 40 percent or more. Plainly, non-Hispanic whites are not straining their budgets to the same extents as Hispanics, blacks and Asians to buy a piece of the American dream.

The high home ownership costs often reflect the introductory terms of loans that make them "affordable," for the first few years. When such loans readjust, the costs increase.

The picture looks particularly difficult for people purchased homes in 2005 and 2006. They made their purchase at what appears to be the top of this particular housing bubble. They may be in for a serious financial loss, as mortgages readjust while the underlying value of their properties decline. Those who have been in their houses for years generally do not pay as much of their income for housing costs, and though they may lose paper value, they will be able to continue to live in their home, as long as they did not refinance it using a new mortgage product.

Those most at risk of losing their homes because of high housing costs are more than proportionally minority, less educated, either very young or very old, and most especially with much lower incomes than those living in affordable situations. (See Table for the results.) The median income of those paying less than 30 percent of their income on housing is $120,900. For those paying between 30 and 50 percent of their income, though, the median is $74,390, and for those paying over 50 percent the median income is $39,900.

Not surprisingly, the areas with the highest proportion of income going for home ownership costs are in Queens (especially Jackson Heights, East Elmhurst and Corona), Brooklyn (notably Borough Park, Greenpoint/Williamsburg, Bushwick, East New York, Ridgewood, Cypress Hill, Highland Park and New Lots) or the Bronx (in particular Morris Heights, University Heights and Fordham.) Manhattan homeowners do not appear to be spending more than they can afford to anywhere the extent of those in the other boroughs. (See map.)

In short, the housing bubble, fueled in part by sub-prime mortgages affects New Yorkers in different ways. However. even many New Yorker who do not work on Wall Street or have a sub-prime mortgage may feel the pinch. As residential property values decline and tax revenues fall, all New Yorkers who depend on city services or who work for the city or state will face stringencies. Thought the housing bubble may have been exciting for many, particularly those selling mortgages or moving into houses they probably could not afford, its hangover is likely to affect everyone.

(Note on sources: This analysis was largely based upon the Public Use Micro Data Sample, or PUMS, from the 2006 American Community Survey, while some data are drawn from tabulated data from that survey and the 2005 survey and the 2000 Census. All responses are based upon self-reports of income, house value, race, education, etc. The data are subject to sample variation.)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

Women of New York City

New York women are different, especially those who live in Manhattan. They are much more likely to be single, earn more money, and have more education than women living in the rest of the United States. And while the same percent of New York women are working as women elsewhere in the country, the jobs they are doing are much different. These are some of the significant results from an analysis of data from the 2005 Census.

About 45 percent of New York City women ages 25 to 64 ever married. In Manhattan, it’s just 37 percent. Elsewhere in the country, however, some 61 percent of women live with a spouse. Manhattan is one of the counties with the highest percent of those living on their own in the United States. Table 1 shows the proportion living with a spouse for men and women in two age ranges. As is plain from that table, those living in Manhattan and the outer boroughs follow a very different pattern than those in the rest of the United States.

Among those 25 to 64, while 63 percent of all Manhattan women have at least four years of college, slightly less than 30 percent of outer borough and other women in the United States have that level of educational achievement. When it comes to holding a job, 69 percent of Manhattan women, 60 percent of outer borough women, and 67 percent of women living elsewhere were working. When one looks at the type of jobs held by women in Manhattan compared to the rest of the United States the differences are striking. Though relatively small proportions, Manhattan women are much more likely to be actresses (about 14 times), authors(about 9 times); lawyers and judges (about 9 times), as well as dancers, photographers, stock and bond salesmen, psychologists, editors and reporters, architects, artists, economists, designers, physicians and surgeons and a range of other professions than in the rest of the United States.

Considering earnings, Table 2 present some information for women working full time in various occupations. In most occupations, men out-earn women. But this is especially true in Manhattan for law, medicine and stock and bonds salesmen. In each of these areas men out-earn women by more than two to one. Even the very high levels of education for Manhattan women do not wipe out this disparity. But female secretaries, designers and authors in Manhattan do earn more than men in those fields.

Women with a spouse in Manhattan have much higher household income, but have lower earnings than those who do not have a spouse. For men, however, those with a spouse have much higher earnings and household income than those without. The pattern is much less marked for those living in the outer boroughs or in the rest of the United States. This suggests that some women in Manhattan though working do not contribute to the family or household income as much proportionately as do their male spouse. This is directly related to the occupational income gaps between men and women in Manhattan. Remember, the very high income professions, such as law and financestill are predominantly male, at least at the highest income levels, even if more women are in them in Manhattan than any where else.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â