Queens Groups Are Divided Over District Lines

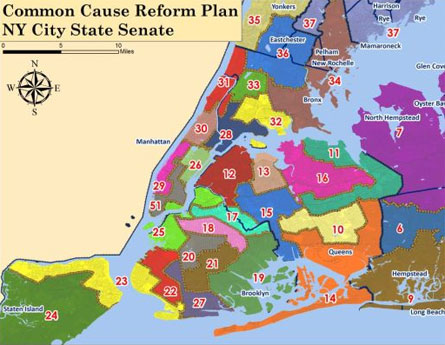

District Lines by Common Cause

With the preliminary redistricting maps to be announced next week, tensions are rising in Queens, where communities are split along legislative lines and rival plans to redraw them.

Many Asian-American groups, joined by some Latinos, have pushed for State Senate and Assembly borders to be redrawn around a single, cohesive Asian community which would cut across Queens and Nassau county lines. Others, led by the group Eastern Queens United, have categorically opposed this.

The groups’ main argument centers around what constitutes “communities of interest” and whether or not race and ethnicity is a key factor in determining these. Moreover, politicians and analysts have said that grouping voters from the two counties together will give Republicans an edge. Both sides have distanced themselves from party considerations.

“We were able to meet with numerous groups throughout the city and develop community boundary lines and narratives to accompany them,” said Jerry Vattamala, a staff attorney with the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF).

Asian-Americans are a growing population in New York. Over the past ten years, the number of Asians in New York City has risen from about 1 million to about 1.42 million, growing from 5.5 percent to 7.3 percent of the total New York population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Over 500,000 Asian Americans live in Queens.

The influx came mostly from immigration, according to James Hong, the Civic Participation Coordinator at MinKwon Center for Community Action, a Korean group. He said that many Asian-Americans who live in these areas have common interests, especially with regard to immigration law, language accommodations and socioeconomic concerns.

Despite their growing numbers, Asian voters are under-represented because their communities sit on top of many legislative partitions, according to AALDEF. Asian communities in Richmond Hill and Elmhurst are split into as many as six assembly segments, said Vattamala.

The current lines “absolutely split up Asian-American Communities,” said Hong. “The effect of diluting the Asian Vote has been very significant.”

In July 2011, 14 Asian-American groups including AALDEF and MinKwon have teamed up to form the Asian-American Community Coalition on Redistricting and Democracy (ACCORD), which has endorsed a proposed redistricting plan called “Unity map." The map was created by AALDEF, PRLDEF (Latino Justice group), the National Institute for Latino Policy and the Center for Law and Social Justice of Medgar Evers college. It was submitted it to the state’s legislative task force on redistricting.

But many other residents and politicians of Queens are opposed to the Unity plan, saying that it doesn’t make sense to put residents of Queens and Long Island in a single Assembly or Senate district. Eastern Queens United, which includes civic groups from Glen Oaks, Floral Park, New Hyde Park, Bellerose and Queens Village, said that the common interest of Queens communities far outweighs any common interests along ethnic lines.

“This is unacceptable,” said Bob Friedrich, the President of Glen Oaks Village Cooperative. “We don’t wan to divide these communities along ethnic, color or religious lines. It serves the needs of politicians to divide these communities.”

Eastern Queens United held a community meeting last week, discussing the redistricting. Assemblyman David Weprin and State Senator Tony Avella attended the meeting, with Avella pledging to vote against any plan, which cuts legislative districts across county lines.

“I understand the goal and agree with it but the way they’ve gone about it is not only inappropriate, it’s reverse gerrymandering,” said Avella, who has met with ACCORD and criticized its proposals. He said that the coalition’s proposals have only gotten worse since they were initially proposed and that they would give Republican legislators an unfair edge in Queens.

He added that as of October 12, ACCORD admitted to failing to consult with South Asian groups whose interests might be different than those of Chinese and Korean Americans. MinKwon’s Hong denied this claim, saying that ACCORD had met with many South Asian groups, including Taking Our Seat as early as July 11.

Still, many lawmakers and analysts think that combining sections of Queens and Nassau Counties would benefit Republicans because of the large number of conservative voters that live in Nassau. Arthur “Jerry” Kremer, a lobbyist and former Assemblyman said that there are no communities of interest that cross county lines that “it is not uncommon for minority legislators to find that their districts are cut up and combined with others.” He added, however, that significant change in Nassau County is likely this time around.

Both ACCORD and Eastern Queens United have denied that their proposals had to do with partisan considerations. Spokespeople for each have said that their primary interest is keeping communities together.

Senator Martin Malave Dilan said that the likeliest areas to see change in the coming redistricting process are in Queens/Nassau, Hudson Valley and the Saratoga area. However, Dean Skelos, the Republican Senate Majority Leader, said that the 63rd senate district will not be in Long Island. Eastern Queens United’s Bob Friedrich said that this was a good start while ACCORD offered no comment.

A previsous version of this article incorrectly named ACCORD as the author of The Unity Map.

Common Cause Helps the Public Get Involved in Redistricting

Map by Common Cause

Common Cause maps the city's Congressional Districts.

This week a number of Assembly Democrats got a peek at what their new district lines will look like if the Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment has anything to say about it. And LATFOR, with legislative leaders, has for decades had the final word on drawing district lines for the state. The process of redistricting was conducted in secret, lines were drawn to protect incumbents and maintain the senate Republicans’ majority, legislators were consulted on what would be convenient for them. The people were as far away from the process as possible.

Even when their plans were challenged in the court as politically motivated or inherently in violation of the law, LATFOR and the majority leaders came out on top.

But this time things have changed. Thanks to the internet, the process by which legislative districts are carved up is no longer such a mystery. Mapping technology allows any citizen with a computer, some spare time and the proper information to draw up their own set of maps. Earlier this week Common Cause issued their own lines and teamed up with Newsday to present the public with an interactive mapping tool so that they can try it themselves.

"We have been outspoken about the problems with the current process, which is characterized by partisanship and political self-interest," said Common Cause’s executive director, Susan Lerner, during a conference call with the press. "Our goal has been to show that there is no practical impediment—it’s only a political one—to achieving fair, non-politicized district maps."

Looking for Input

"It is kind of like pulling back the curtain,"said Sen. Liz Krueger, who has been looking forward to seeing Common Cause’s lines for months. She apparently wasn’t the only one.

Assemblyman Jack McEneny, Democratic chair of LATFOR, said that he and his colleagues have been waiting to see what Common Cause produced, and the plan is to utilize parts of their maps.

"We have been anticipating them for some time," said McEneny. "We will take a look at them and see what good parts we can incorporate into our plan. Then I would expect we will begin to have public hearings in January."

As for what it feels like to have the public breathing down his neck while he is doing a job that used to be draped in secrecy, McEneny said, "Things have changed. It is part of democracy to be second guessed. We grow up thinking things are either good or bad, but there is a lot of gray here, a lot of competing interests and groups who value certain things over others."

The Power of Politics

Although they are happy to see the public given a chance to be more informed and involved in the redistricting process, members of other good government groups are skeptical that Common Cause’s efforts will change the end result.

"I think they (Common Cause) looked at lines in a non-partisan manner, and that is refreshing. It looks to me that they managed to keep communities of interest together without regard to incumbents, and that is refreshing. But I don’t think it will make a darn bit of difference. I don’t think LATFOR has regards for anything but incumbency protection," said Barbara Bartoletti of the League of Women Voters.

Dick Dadey, executive director of Citizens Union (Gotham Gazette is published by Citizens Union Foundation, the sister organization to Citizens Union), agreed with Bartoletti.

"I think the maps are very instructive of how impartial districts could be drawn but I’m doubtful they will be utilized by LATFOR because of the political reality," said Dadey.”

The Compromise

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has promised to veto any lines that are drawn up by LATFOR, but he has also indicated that a veto would cause chaos—chaos that he would like to avoid. For months Cuomo’s office has been negotiating for a compromise that would avoid a veto. So far nothing has come of it. Cuomo’s office did not return calls for comment.

If such a deal came together it is unlikely to make use of Common Cause’s maps, as they are based on the kind of change that would happen if politics were not involved, whereas current negotiations are based on what will get senate Republicans to the table to agree to some sort of compromise.

Dadey said that he has spoken with the three parties involved in the negotiations. "Even though we may add a level of openness to the 2012 process it will be a political decision and Common Cause’s maps are apolitical," said Dadey.

The idea is to achieve a deal that would see less drastic change this year but perhaps something more substantive for the next round of redistricting in ten years. There is a sense among some at the negotiating table that Common Cause’s lines could frighten Senate Republicans away.

"To achieve reform we will need the unusual convergence of interests that include the Senate Republicans. Any reform any reform must treat all parties fairly now and in the future," said Dadey.

Others see things differently. They think the lines might make Senate Republicans more apt to make a deal that would avoid a veto, which would mean putting their future in the hands of a judge—especially when a judge could use Common Cause’s lines as an example of what districts might look like with without legislators drawing them.

But other advocates point to New York’s demographics and the fact that a majority of New Yorkers are registered Democrats.

Krueger thinks that Common Cause’s lines will serve as a guide post for LATFOR, Cuomo, or the courts if it does come down to a veto. Now that the public has been informed about the process, Krueger thinks it will be hard for LATFOR to ignore the fact that people are watching and won’t accept the excuses LATFOR used to make, excuses like, "There was no other way we could have drawn them."

Common Cause isn’t the only group allowing people to try their hand at redistricting. Fordham University is holding a competition for teams to redraw New York’s district lines. One of the participants is a ten-year-old child from Michigan.

Just How Bad is it?

A recent report by Citizens Union showed just how integral the redistricting process has been to keeping incumbents in their seats and maintaining the balance of power in Albany. The report showed that 96 percent of incumbents have been reelected since 2002. In 2006 100 percent of incumbents were reelected. The report shows that the current redistricting process makes elections far less competitive and as a result reduces voter turnout. Furthermore the report shows that minorities are underrepresented. "There are 15 different Assembly districts in New York City where the Asian-American population exceeds 20 percent, but there is only one [Asian] representative in the Assembly," Citizen Union’s Alex Camarda.

10 Years Later: Enumerating the Loss at Ground Zero

Photo by Joshua Schwimmer

The direct losses to New York and the United States from the World Trade Center attack are incalculable when one considers the personal and emotional loss to family and friends of the victims, as well as to all other New Yorkers, who have contended with the specter of 9/11 during the past decade. Yet, the magnitude of the losses and especially the recovery are being calculated daily. Indeed, Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently claimed: "As we look back on the past decade, and as the picture of what has happened here comes into sharper focus, I believe the re-birth and revitalization of Lower Manhattan will be remembered as one of the greatest comeback stories in American history."

Other aspects of the impact of the tragedy also can be measured. Here we use demography to look at the victims, the neighborhood and the financial businesses -- the so-called FIRE or Finance, Insurance and Real Estate, sector -- to gauge the magnitude of the loss and extent of the recovery from 9/11 for Manhattan and the city. As we will see though Lower Manhattan has come back in certain respects, Manhattan no longer accounts for over half of all employment in the FIRE sector. Perhaps, this is not surprising given the magnitude of the attack.

Individuals and Businesses Lost

Information provided by the medical examiner and the Federal Emergency Management Agency and unearthed by the New York Times helped fill in the picture of this unprecedented catastrophe. Census information on businesses and those working in lower Manhattan before the attack throw into high relief the stark dimensions of the direct toll.

All of New York City and the United States lived through the attack, but those who died came from very narrow slivers of space, both actual and socio-economic. Indeed, more than two thirds of the 2,753 victims, or at least 1,946, died on the upper floors near or above where the planes crashed: the top 19 floors of the North Tower and the top 33 floors of the South Tower. When one adds the firefighters (343), police and other rescue workers (about 90) and the victims from the two planes (157), one has accounted for almost 90 percent of all victims.

The bond trading firm Cantor Fitzgerald lost 658 employees; Marsh and McLennan, an insurance firm, 295; Aon, another insurance firm, 176; Fiduciary Trust International, a financial firm, 87; the Port Authority, 75; Windows on the World Restaurant, 73; Carr Futures, a brokerage firm that is now part of Newedge, 69; Keefe, Bruyette and Woods, a security brokerage firm, 67; and equity analysts Sandler O’Neil and Partners, 67. All these companies had offices on high floors in the towers. Risk magazine, the trade bible of the derivatives industry, which defined much of finance in the last two decades, was having a conference at the top floor restaurant Windows on the World. Everyone in attendance, including many high executives, perished.

Given the firms for whom many of those in the World Trade Center worked, as well as the large number of firefighters and other rescue workers, the other demographic facts should not be that surprising. The victims were overwhelmingly male (about 75 percent), young (many under 40, most under 50) and white (about 75 percent). Only about 8 percent were black, 9 percent Hispanic and about six percent Asian. About 75 percent were born in the United States, and the others originated from many different countries. Together New York and New Jersey residents accounted for about 87 percent of the victims. Many of the airplane passengers came from Boston and California.

As for the neighborhoods where the victims lived, we now know that the Upper East Side had the most losses (44), while Hoboken, N.J., had the highest proportion of loss of any single area, losing 39 residents, or about one per thousand. Given the high paying jobs at many of the companies in the World Trade Center, it is not surprising that many of the victims lived in very affluent parts of the metropolitan area, including the Upper East Side and Basking Ridge, N.J.

10048 and the Financial District

The World Trade Center had its own ZIP code, bounded by West, Vesey, Church and Liberty streets. According to the census, in 2000 only 55 people resided in that zone, but in terms of business activity, the area was something to behold. Within its boundaries, some 1,294 establishments employed about 31,119 people, and 928 of these firms were in finance or real estate, including insurance.

Altogether, the 1,294 companies paid about $3.9 billion (all figures are in 2009 dollars) in wages and salaries, averaging about $126,000 per employee, far higher than the average for the New York metro salary of about $69,300 per employee. Few other ZIP codes and none outside of the Financial District rivaled the World Trade Center in generating employment income per employee. Most of the stores, restaurants and other retail establishments paid high rent to be in the trade center. Sandwich shops and other establishments, where less well-off employees worked, were mostly "just" across the street in another ZIP code.

Lower Manhattan accounted for about 3 percent of the employment and over 5 percent of the earnings in the large New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania Metropolitan area, which extends to Montauk at the tip of Long Island in one direction and to Hope County, Pa., in the other. The finance sector accounted for about 9.2 percent of the employment in the entire region, but 19.2 percent of the wages paid in the New York metropolitan area in 2000.

The 2,000 or so victims who worked in offices will never return to their desks at the World Trade Center. The many victims who served them -- from the staff at Windows on the World, to the firefighters and other emergency personnel who tried to save them --will not return either. Beyond them, another 30,000 workers, who used to work at the trade center, also do not go there anymore.

The loss of ZIP code 10048 represented a blow to the heart of the financial district. Indeed, those working there, though just a small slice of the city's population, nonetheless represented many aspects of New York City society: the wealthy older executives at the Risk conference or running some of the firms, the young traders on the make (some of whom no doubt spent their very high incomes), the immigrants working in the service fields, the computer techs, the lawyers and others all supporting the financial community defined ZIP code 10048.

The Neighborhood Today

Ten years on, data suggest that the recovery from the 9/11 is not yet complete, neither for Manhattan's financial sector nor for the area in lower Manhattan that included the World Trade Center. Many more people live in Lower Manhattan today than were counted in the 2000 census, as the singular focus on finance and the rest of FIRE sector could have dimmed.

Considering employment in downtown Manhattan south of the Holland Tunnel, in 2000 there were about 248,000 employees with average salaries of about $120,000 per year. By 2005 that figure had risen to 271,000 averaging about $115,000. By 2009 in the midst of the financial crisis, the number had declined to 268,000 and the average income had dropped to about $106,000. Though employment is up somewhat, the average wages, even before the boom and bust, has lagged those in 2000, indicating, perhaps, more employment in other less lucrative sectors and less employment in the extremely lucrative FIRE sector.

When one looks at the entire financial sector including real estate and insurance, it employed just over 400,000 people in Manhattan in 2000 with average salaries of $202,000 per year. By 2005, the number had declined to 374,000 employees who averaged $208,000, and by 2009 some 362,000 employees averaged $195,500.

Though Lower Manhattan seems to have recovered in terms of employment if not in terms of income, the financial sector in Manhattan seems to have taken a blow from which it has yet to recover. When the financial sector in Manhattan is compared to financial sector in the entire metropolitan area it is plain that some of its jobs have moved away from Manhattan. The sector in this larger region showed some decline to 2005 and then a small increase to 2009. In 2000, Manhattan accounted for 50.7 percent of the employment in finance in the wider metropolitan area. By 2005 that percentage had declined to 46.6 percent, and by 2009 it dropped further to 44.0 percent.

So 10 years after 9/11, exactly what will happen to the area that was designated 10048 has yet to be fully determined, as conflicts continue over what will be built in the shadow of the towers and who will occupy the new offices. Beyond 10048, however, the financial sector seems to have not recovered completely, though employment, if not average income, has continued to increase in lower Manhattan. It seems Manhattan has permanently lost a substantial share of the financial sector.

It is true several banks and other businesses are planning sites inlower Manhattan and in the area around the trade center, and many have moved back to the areas. Despite all of that, the FIRE sector in Manhattan still is diminished and seems to be declining relative to the rest of the metropolitan area. So beyond the memories of the victims and the grief of their families, Manhattan and New York City are likely never to fully recover the losses to the financial sector brought on by 9/11.

Source Note: All the data regarding the number of employees and wages paid are from the County Business Pattern data,which includes some data on Zip Code Business Patterns)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Under a new name, census data stands ready for perusal

Photo by PaulSh

The 2010 census has been rolling out since February with New York state getting the first of its data on March 24 and more data releases during the summer. Yet, almost every day reporters, redistricting specialists and even other demographers ask when data to answer questions such as the following will be released:

- When will we know the number of immigrants in New York City and in various neighborhoods throughout the city?

- How many Hispanic citizens of voting age live in Washington Heights?

- Has the median income in Jackson Heights grown or declined since 2000?

- How many veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars live in Staten Island? In the Bronx? On the Upper West Side?

- Which recent college graduates are ending up with jobs? How much do they make? How many are living at home with their parents?

- Has the number of people working in finance increased?

The answer is simple and surprising: "All the information you need was already released on Dec. 14 last year."

As you may recall, the census form you filled out last spring had just a few basic questions. So the data released on the basis of that can only include: number of people, dwelling owned with or without a mortgage or rented with or without cash rent, relationship to householder, sex, age, and race or races, including principal tribe or group, if Native-American, Asian or Pacific Islander. The other data -- indeed the data that in many ways is the most interesting and heavily used -- comes from the American Community Survey, or ACS, which is actually "the rest of the census" and was released in December.

The New Census

The census has been radically redesigned, and many census users have yet to catch up. Every census from 1940 through 2000 included a "short form" given to everyone to get a full enumeration of the population, as dictated by law. It asked only for very basic demographic information. The Census Bureau also administered a "long form" questionnaire that went to only a sample of persons or households and included a much larger set of social and demographic questions.

In 2000 the short form included only eight questions for the householder and six for every person living in the household. These were the same basic questions that would be asked in 2010 about sex, age, relationship to the householder, race and Hispanic status.

About one in six households received the "long form," which included some 53 questions. In addition to the basic questions in every census form, this survey also contained questions on a whole panoply of characteristics, including housing, moving in the last five years, employment, detailed income sources, military service, disability status, ancestry, place of birth and education.

Until 2010, the long form and short form were distributed in tandem, but then the government split them. Beginning in 2005, the Census Bureau began to collect data for the American Community Survey, which is very similar to the old long form. That survey gets responses from about 2 million households and residents of group quarters (prison, dormitory, institution) every year, and tracks the same sort of data that was produced by the long form sample. The survey takes place all year and interviews, where necessary, are conducted by permanent staff -- not the temporary workers who interview for decennial census.

The Census Bureau releases three sets of data each year from the community survey: the one-year, the three-year and the five-year files. The one-year file is released for areas of at least 65,000 in population, the three-year file for areas of at least 20,000 and the five-year file for all of the areas for which the long form was released (block-groups, tracts and higher). The census releases data only for certain locations with larger populations at one and three-year intervals. This is because, since the ACS is a sample, its reliability depends on sample size.

So on Dec. 14, 2010, the Census Bureau released the first five-year file from the American Community Survey, including all the data that used to be released from the census long form. This totaled 32,000 columns with 675,000 rows of data. These data are comparable to what was compiled from the 2000 Census and allow one to answer many questions at the neighborhood level, where data are needed beyond the few questions in the 2010 census.

Using the Data

There are some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form. The first five-year file includes data from 2005 through 2009, while the long form data were collected on the same date as the census. So now relatively current data are available and updated every year. This can be problematic for users -- for instance, the five-year file includes data from both before and after the financial crisis of 2007-08. On the other hand, the benefit is that even for small areas data never are more than a few years out of date. For larger areas the one-year file (from 2009) and the three-file (for 2007-2009) also are available. So we now have detailed social and economic data for a large sample available in a much more timely fashion every year.

As was the case with the long form, the community survey is a sample and so subject to sampling error. The confidence interval is often expressed as percent or number plus or minus another number that defines the interval. For instance: Bush 51, Gore 49 plus or minus 3 percent. The estimate should be between 54 percent Bush, 46 percent Gore to 48 percent Bush to 52 percent Gore. This would be accurate 90 percent, 95 percent or 99 percent of the time, depending upon the level chosen.

Unfortunately, the Census Bureau's approach to estimating the confidence interval is flawed in a number of ways and vastly overestimates the potential error in many instances. For example, if no one is found from a given group, say Native Americans or Italians or Colombians in a given tract in Brooklyn, the confidence interval is arbitrarily set to some number (often 75) and is noted in the data. This would mean, if it were taken literally, that the number of a group in a given tract could be plus or minus 75 and potentially create a negative population count. The Census Bureau now has a note that such absurdities should not be taken seriously, but this implies that the method for computing confidence intervals they used is wrong.

The bureau also used this flawed method in deciding whether to release tables for specific areas from the one-year and three-year files, something it calls "filtering." For example, for years, the bureau did not release foreign place of birth for people living in the Bronx or Staten Island. There are many, many examples of filtered data, which makes the data less useful. (A memo I wrote to the Census Bureau on the topic of their estimation of confidence intervals and it misuse, along with the agency's response is available here. )

At this point, the Census Bureau is mulling over what to do, but in the meantime one should realize that many of the reported confidence intervals are too large and can make it difficult to correctly estimate the confidence interval in cases where the user wants to combine data from individual neighborhoods to come up with statistics for larger areas.

A second issue with the American Community Survey is that its results at the county level are forced to conform to the system used by Census Bureau for yearly population estimates. This means that the actual number reported for a given location in the community survey may conflict with the census counts. This problem, of course, afflicts New York City, where the American Community Survey and census estimates are much higher -- about 250,000 people -- than the census counts. However, the proportions of a given group or category in the community survey should be correct, even if the totals are incorrect. Direct comparisons of totals in the survey files with those in the census files, though, can lead to anomalies.

In sum, despite some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form data, the survey is in most ways superior. Not only is the data released more often and in a more timely fashion, but the numbers may be more accurate since the survey is conducted by a permanent interview staff. So the next time you cannot find the data you want in the census report look for it in the American Community Survey.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Under a New Name, Census Data Stands Ready for Perusal

Photo by PaulSh

The 2010 census has been rolling out since February with New York state getting the first of its data on March 24 and more data releases during the summer. Yet, almost every day reporters, redistricting specialists and even other demographers ask when data to answer questions such as the following will be released:

- When will we know the number of immigrants in New York City and in various neighborhoods throughout the city?

- How many Hispanic citizens of voting age live in Washington Heights?

- Has the median income in Jackson Heights grown or declined since 2000?

- How many veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars live in Staten Island? In the Bronx? On the Upper West Side?

- Which recent college graduates are ending up with jobs? How much do they make? How many are living at home with their parents?

- Has the number of people working in finance increased?

The answer is simple and surprising: "All the information you need was already released on Dec. 14 last year."

As you may recall, the census form you filled out last spring had just a few basic questions. So the data released on the basis of that can only include: number of people, dwelling owned with or without a mortgage or rented with or without cash rent, relationship to householder, sex, age, and race or races, including principal tribe or group, if Native-American, Asian or Pacific Islander. The other data -- indeed the data that in many ways is the most interesting and heavily used -- comes from the American Community Survey, or ACS, which is actually "the rest of the census" and was released in December.

The New Census

The census has been radically redesigned, and many census users have yet to catch up. Every census from 1940 through 2000 included a "short form" given to everyone to get a full enumeration of the population, as dictated by law. It asked only for very basic demographic information. The Census Bureau also administered a "long form" questionnaire that went to only a sample of persons or households and included a much larger set of social and demographic questions.

In 2000 the short form included only eight questions for the householder and six for every person living in the household. These were the same basic questions that would be asked in 2010 about sex, age, relationship to the householder, race and Hispanic status.

About one in six households received the "long form," which included some 53 questions. In addition to the basic questions in every census form, this survey also contained questions on a whole panoply of characteristics, including housing, moving in the last five years, employment, detailed income sources, military service, disability status, ancestry, place of birth and education.

Until 2010, the long form and short form were distributed in tandem, but then the government split them. Beginning in 2005, the Census Bureau began to collect data for the American Community Survey, which is very similar to the old long form. That survey gets responses from about 2 million households and residents of group quarters (prison, dormitory, institution) every year, and tracks the same sort of data that was produced by the long form sample. The survey takes place all year and interviews, where necessary, are conducted by permanent staff -- not the temporary workers who interview for decennial census.

The Census Bureau releases three sets of data each year from the community survey: the one-year, the three-year and the five-year files. The one-year file is released for areas of at least 65,000 in population, the three-year file for areas of at least 20,000 and the five-year file for all of the areas for which the long form was released (block-groups, tracts and higher). The census releases data only for certain locations with larger populations at one and three-year intervals. This is because, since the ACS is a sample, its reliability depends on sample size.

So on Dec. 14, 2010, the Census Bureau released the first five-year file from the American Community Survey, including all the data that used to be released from the census long form. This totaled 32,000 columns with 675,000 rows of data. These data are comparable to what was compiled from the 2000 Census and allow one to answer many questions at the neighborhood level, where data are needed beyond the few questions in the 2010 census.

Using the Data

There are some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form. The first five-year file includes data from 2005 through 2009, while the long form data were collected on the same date as the census. So now relatively current data are available and updated every year. This can be problematic for users -- for instance, the five-year file includes data from both before and after the financial crisis of 2007-08. On the other hand, the benefit is that even for small areas data never are more than a few years out of date. For larger areas the one-year file (from 2009) and the three-file (for 2007-2009) also are available. So we now have detailed social and economic data for a large sample available in a much more timely fashion every year.

As was the case with the long form, the community survey is a sample and so subject to sampling error. The confidence interval is often expressed as percent or number plus or minus another number that defines the interval. For instance: Bush 51, Gore 49 plus or minus 3 percent. The estimate should be between 54 percent Bush, 46 percent Gore to 48 percent Bush to 52 percent Gore. This would be accurate 90 percent, 95 percent or 99 percent of the time, depending upon the level chosen.

Unfortunately, the Census Bureau's approach to estimating the confidence interval is flawed in a number of ways and vastly overestimates the potential error in many instances. For example, if no one is found from a given group, say Native Americans or Italians or Colombians in a given tract in Brooklyn, the confidence interval is arbitrarily set to some number (often 75) and is noted in the data. This would mean, if it were taken literally, that the number of a group in a given tract could be plus or minus 75 and potentially create a negative population count. The Census Bureau now has a note that such absurdities should not be taken seriously, but this implies that the method for computing confidence intervals they used is wrong.

The bureau also used this flawed method in deciding whether to release tables for specific areas from the one-year and three-year files, something it calls "filtering." For example, for years, the bureau did not release foreign place of birth for people living in the Bronx or Staten Island. There are many, many examples of filtered data, which makes the data less useful. (A memo I wrote to the Census Bureau on the topic of their estimation of confidence intervals and it misuse, along with the agency's response is available here. )

At this point, the Census Bureau is mulling over what to do, but in the meantime one should realize that many of the reported confidence intervals are too large and can make it difficult to correctly estimate the confidence interval in cases where the user wants to combine data from individual neighborhoods to come up with statistics for larger areas.

A second issue with the American Community Survey is that its results at the county level are forced to conform to the system used by Census Bureau for yearly population estimates. This means that the actual number reported for a given location in the community survey may conflict with the census counts. This problem, of course, afflicts New York City, where the American Community Survey and census estimates are much higher -- about 250,000 people -- than the census counts. However, the proportions of a given group or category in the community survey should be correct, even if the totals are incorrect. Direct comparisons of totals in the survey files with those in the census files, though, can lead to anomalies.

In sum, despite some differences between the American Community Survey and the old census long form data, the survey is in most ways superior. Not only is the data released more often and in a more timely fashion, but the numbers may be more accurate since the survey is conducted by a permanent interview staff. So the next time you cannot find the data you want in the census report look for it in the American Community Survey.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Failure of Redistricting Reform Could Bring Reprise of 2002's Fiasco

Photo by Boss Tweed

Former Mayor Ed Koch got a majority of state legislators to sign a pledge saying they supported redistricting reform but, so far, that has not translated into change

As the current state legislative session winds down, efforts to reform the redistricting process in New York state appear to be dead. Yet, at this very moment the new Citizens Redistricting Commission in California, which has final authority, has released a preliminary plan that in the process of cleaning up lines would radically alter the California congressional delegation.

It would add up to five Hispanic seats, increase the number of Democrats and throw a number of sitting U.S. representatives into the same district. Beyond that, the commission's proposal may end up creating the Democratic super majorities in both houses of the state legislature needed to raise the state's taxes and pull it out of its financial crisis.

Meanwhile in New York state, despite former Mayor Ed Koch's efforts to get many legislators to pledge to vote for reform, despite the fact that Gov. Andrew Cuomo claims to be making it a priority and despite universal support of the usual good government groups, no bill has been reported out or is expected to come to the floor before the session is over in a few days. This means that the same chaotic system that brought us an impasse in Congress and the deadlocked State Senate will remain in place for this round.

Obstacles n New York

The California experience throws into high relief why reform of the legislature by the legislature repeatedly fails in New York state despite receiving lip service support for the last few years. Two reasons stand:

- If the system changed, incumbents would not be protected, and many would face opponents who are also sitting legislators.

- Under the current system, demographic shifts that would throw both houses into Democratic hands can be contained. This was done in 2002 and will likely be repeated this time around.

A constitutional amendment would make it possible to have the type of reform that happened in California. But for that to happen, the legislature would have to pas the measure in two sessions, and the voters would then have to ratify it.

The Democrats could have started the process by passing a constitutional amendment on redistricting reform last year when they controlled both houses of the legislature. They did not. If they had -- and if the amendment passed again this term -- it could have been on the ballot this November, in time for this round of redistricting.

The enactment of a legislative reform remains possible. This would mean that a commission would draw lines, but the legislature and the governor would have to approve the lines and so would have final say. Even this limited reform has not made it to the floor of either house.

When one looks at what is ahead for redistricting, it is obvious why this has happened. Republican senators do not want to lose their majority, and the Democrats in the Assembly do not want to risk their individual seats and lose a few members from the majority, despite their overwhelming advantage. This stalemate occurred even though the fiasco that was redistricting last time is about to be rerun, and everyone claims to support reform.

The Results Last Time

The population shifts found in the 2010 census are very similar to those in 2000, and now as then two congressional seats have been lost. In 2002 a judge declared an impasse after the legislature failed to act, and a set of congressional lines were proposed by a special master. At the point a deal was cut and the present congressional lines were approved.

In the last redistricting, all plans initially considered for the State Senate involved 61 seats, the total number at that time. Then at the 11th hour, a new plan was proposed. It added one seat downstate bringing the total number of senate districts to 62.

In addition, the plan carefully allocated the population so that every district downstate was overpopulated and every district upstate was under populated. It also maintained the so-called Velella racial gerrymander, (the seat now held by Jeffrey Klein); and cracked and packed minorities in Long Island. "Cracking" involves splitting a large bloc of minority voters into several districts, so that they cannot chose their preferred candidate. "Packing" means putting a large block of minorities into one district so as to reduce their impact several districts.

This plan was challenged in federal court unsuccessfully. Because it allowed for an even number of senators, it led directly to the State Senate deadlock in 2009.

The Assembly plan in some ways was the mirror image of the Senate plan. Most districts upstate were over populated, many downstate were under populated. Incumbents were protected.

What Can We Expect This Time?

I have prepared data on the population and the citizens of voting age population by various groups for the present set of lines. Here is what New York State faces. For Congress:

- All congressional districts are under populated. (Congressional seats are required to be effectively equal.)

- Two seats will be lost, One from districts from 1 to 14 or 15, which encompasses the city and its suburbs. The other seat will come from upstate -- from districts 16 through 29.

- Districts 10, 6 and 11have a majority of voting age citizens who are African Americans.

- District 16has a majority of Hispanic voting age citizens.

- Two additional districts have a majority of Hispanic and African Americans of voting age combined. Two more are near such a majority.

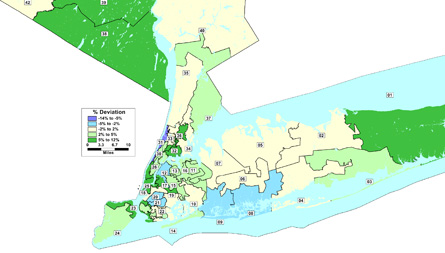

Currently all but one of the state's congressional districts -- District 1 in eastern Long Island -- is smaller than the ideal district. For a larger map showing how much each district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

For the State Senate:

- 13 districts are under populated (based upon a deviation of 5 percent from the ideal), while eight are over populated.

- Most under-populated districts are upstate.

- Six districts have a majority of African American citizens of voting age.

- Two districts have a majority of Hispanic citizens of voting age.

- Four districts have a majority of Hispanics and African Americans of citizen of voting age combined.

Under New York's current State Senate districts, voters upstate -- many in largely Republican areas -- have more clout than their downstate counterparts. Most of the districts with fewer voters than average are upstate, while those with a larger number of voters are more likely to be closer to New York City. For a map showing how much each State Senate district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Under New York's current State Senate districts, voters upstate -- many in largely Republican areas -- have more clout than their downstate counterparts. Most of the districts with fewer voters than average are upstate, while those with a larger number of voters are more likely to be closer to New York City. For a map showing how much each State Senate district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Many of the State Senate districts in and around the city are larger than normal for the state, giving their residents less power. A glaring exception is District 31, stretching along the West Side of Manhattan and into the Bronx. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Many of the State Senate districts in and around the city are larger than normal for the state, giving their residents less power. A glaring exception is District 31, stretching along the West Side of Manhattan and into the Bronx. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.For the Assembly:

- 26 districts are under populated and 22 are over populated based upon a 5 percent deviation.

- Fifteen districts have a majority of Africans American citizens of voting age.

- Twelve districts have a majority of Hispanic citizens of voting age.

- Eight additional districts have a majority of Hispanics and African American citizens of voting age combined.

For a table listing all 150 State Assembly districts and their demographic characteristics, as well as their size, go here.

With 150 Assembly districts, those deviating sharply from ideal size are more scattered around the state than is the case with State Senate districts. For a map showing how much each State Assembly district deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Heavily Democratic New York City has a large number of State Assembly districts that are substantially smaller than normal, giving their resident ore clout in the Assembly than people who live in more Republican Long Island. For a map showing how much each district in the metropolitan area deviates from the average -- or ideal -- size, go here.

Hammer Lock

The population's changes are massive, but the legislature together with the governor have chosen to keep complete control of the redistricting process (except for possible court or Justice Department intervention) for another round. They will maintain their power, as they have in the past. Unlike California, there is little prospect for fair redistricting in New York State, only chaos similar to the last round. (To view my recent testimony in Albany on Redistricting Reform, go here and here.)

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Wounded City's Pride but Probably Got the Numbers Right

Photo by Jason Chiu

The 2010 census poured cold water on Mayor Michael Bloomberg's rosy view that New York City would hit 9 million long before 2030. The census found that, instead of growing to 8,421,789 residents as the census estimated just a few days before the official numbers were released, New York City had only 8,175,153 residents, some 246,636 less than expected.

The estimated brisk growth pace of 5.2 percent since 2000, suddenly became a phlegmatic 2.1 percent. Indeed, if present trends continue New York City will not make it to 9 million until sometime in the decade of 2050. In short, the growth rate, if correct, means that many of the enthusiastic proclamations about the city's unique growth and its attractiveness as a place to live are simply wrong.

Predictably, the mayor, who made his fortune purveying presumably accurate financial information, is not willing to believe that the census's careful enumeration of New York’s population could be correct. He is planning to challenge it, and other officials are supporting that challenge. However, instead of taking the issue to court, they plan to invoke the Census Bureau's own Count Resolution process. This is a technical procedure that generally corrects blatantly wrong counts. After 2000, for example, the Census Bureau placed a number of prisons and college dorms in the wrong cities, counties and towns. When these mistakes were brought to the Census Bureau’s attention, it corrected such obvious errors.

New York's argument for an adjustment is much more complex relying as it does upon the increase in vacancies and the undercounting of immigrants. Indeed, there are at least four reasons to have confidence in the census count.

1. Housing vacancies are on the rise in New York City and throughout the country:

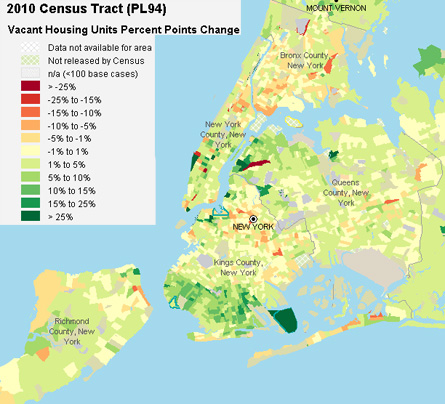

Over the decade New York City did see an increase of about 170,000 housing units, but, according to the Census, the number of vacant units rose by some 82,000.

Bloomberg explanation: The census misclassified many occupied units as vacant.

Home and apartment vacancy rates rose between 2000 and 2010 -- in New Yrk and throughout much of the country (For a larger version of this image, go here.

Possible other explanation: Many of the new units were built as part of the boom and remain vacant. As the accompanying map shows, the rise in vacant units occurred not in the immigrant areas in Brooklyn and Queens, but rather in other areas such as the far West Side and Bay Ridge Brooklyn. Most of the other cities in the United States experienced a large increase in the proportion of vacant units. Indeed New York City's increase of 2.15 percent means that it ranked 79th out of the 109 cities with more than 200,000 population in 2010. New York City, along with the rest of the United States, experienced a housing bubble and still working through the extra units that were constructed during that bubble. So the vacancies may be real, unless New York City experienced growth unlike any city in the country.

2. This census missed many immigrants.

The Bloomberg administration has said the census staff was unable to count many newcomers to the city, particularly those who came to the country illegally or live in illegally divided apartments.

Other explanation: Of course some immigrants were missed, but it is also true that immigration of all sorts slowed during the financial crisis. It may be that New York’s immigrant fueled growth may have tapered off.

Certainly the strong increase in immigrants seen in places like Queens and Brooklyn during the decade of the 1990s has slowed substantially, as the climate for immigrants has become much less friendly nationally and their job prospects have ebbed. Indeed, Jeffrey Passel and D'Vera Cohn at the Pew Center estimatedthat the number of illegal immigrants to the US declined by about one million between 2007 and 2009. New York City seems likely to have experienced some of this decrease.

3. The 2000 census may have overcounted New York City.

This is a seldom discussed point, but if the census, because of the very real difficulties of getting an accurate count in a city as diverse as new York, could have overcounted the number of people in the five borough in 2000 due to putting phantom residents into housing units that did not exist or by double counting some. (For more on this, see my earlier column.) If this happened and the excess was reversed in 2010, New York City's apparent growth would be less than its real growth.

Apparently the census also considered this possibility as I outline in another previous column: . If the city had been overcounted by say 200,000 in 2000, and was not overcounted this time, its real growth would actually be about 4.7 percent. Any overcount would serve as the base for the census estimates during the past decade, so if the city were overcounted by 200,000 in 2000 -- and so really had about about 7.8 million people -- then the estimated growth of roughly 420,000, would bring the census estimate almost exactly to the same number as were counted in 2010.

4. The 1990 census undercounted New York's population.

An undercount in the 1990 census, which New York and other big cities challenged in an unsuccessful lawsuit, means that the increase in the 1990s was overstated. Any undercount in 1990 combined with the possible overcount in 2000 would have inflated the percentage growth between 1990 and 2000. Because many demographic and econometric models use recent growth to estimate future growth, the projection for the first decade of the 21st century then could have vastly overestimated population growth.

All in all then, it is quite likely that the 2010 census count is basically accurate, but that the growth rate for the city is more than suggested by the change between 2000 and the 2010 census. New York, it seems, did participate in the slowing of immigration and overbuilding that were common in the 2000s.

When question about the city's growth, Bureau of the Census director Robert Groves said, "This is the time when many mayors receive counts that disappoint." Though Bloomberg and his administration indeed may be disappointed, the census surprise for New York City pales in comparison with that for Detroit. The wrong estimate there implied that Detroit had about 200,000 more people than it had -- meaning the numbers originally projected the Motor City as being 28 percent larger than it turned out to be.

Many cities in the United States, especially in the East, had population loss or very slow growth since 2000. Maybe it is disheartening that New York’s apparent growth in the 1990s did not continue into the 2000s, but after the 9/11 attacks and the financial crisis, maybe the city's continued though slower growth indicates not weakness but just how robust New York City is.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Brings Unpleasant Surprise for State Politicians

These maps show the estimated shifts in population between the 2000 Census and 2009. As has been true for decades, upstate regions continue to lose population.

New York state received a nasty surprise from the Census Bureau on Dec. 21. According to the first results from census 2010, the state has 163,351 fewer people than the bureau estimated it did on July 1, 2009. As a result, New York will lose two congressional seats, bringing its total down to 27, tying it with Florida.

The loss of two congressional seats will set off a huge redistricting fight. Beyond representation in Congress, the diminished New York state population will have a major impact on the amount of federal aid that the state receives.

The Missing New Yorkers

If New York's population had matched the July 1, 2009 estimate, it would have lost only one seat. If the estimated rate of growth in the population from 2008 to 2009 had continued to April 1, 2010, then the state would have 19,596,910 residents, some 218,808 more than the 19,378,102 persons who were actually enumerated.

This chart compares the population count in the 2000 census and the year-to-year estimates with the final count in 2010. The purple indicates how much larger the 2010 count would have been if the estimated trends had continued. (Click on the chart to view a larger image.)

Demographers and politicos are scratching their heads trying to figure out how this happened and what the implications will be. Unlike California, which has already claimed an undercount and protests the census results , New York state is still contemplating the impact and sources of this apparent population loss.

An examination into which parts of the state were overestimated or undercounted is necessary. Once the redistricting data are released in March, we will have much better information.

In general, though, there are three possible explanations:

-- The procedure by which the census creates estimates is flawed.

-- There are problems with the census 2010 count.

-- The 2000 count may have been somewhat inflated, and the new count reflects a return to reality.

Each of these explanations could be true in various ways. The census estimates are based upon births and deaths and international and domestic migration. Immigration -- foreign or domestic -- is particularly hard to capture, and the number of immigrants to New York state may have declined. Foreign immigration would mostly affect the city and downstate, while domestic immigration is important upstate.

New York state has many "hard to count" areas, especially in the city. Though major efforts were made to count residents from these areas, it may be that the backlash from 9/11 and a perceived increase in anti-immigration sentiment led some immigrants to be less willing to participate in the census than they were in 2000. Similar problems may have affected upstate, if the census outreach was ineffective.

Finally, technical issues related to the addition of extra addresses arising from a census check of addresses in 2000 may have led to duplication. If so, it is possible that the city population was somewhat overcounted in 2000. Since the census numbers from 2000 become the base for the census estimates, if those extra addresses were removed or the Census Bureau eliminated more duplicate addresses, then the population in the city, especially in parts of Queens and Brooklyn would be less than was estimated.

Up for Grabs

Whatever the reason for the lower count in New York State, the implications for congressional redistricting are massive. Most of the population losses occurred in upstate New York, while the gains were in areas in and around the city, most particularly in outer ring suburbs.

The table below shows each district's population gain or loss, and some characteristics of the district, including the current incumbent, his or her party, the member's vote in the November elections and the degree to which the districts deviates from the ideal population size of 717,707 people.

| District | Party | Name | Incumbent | 2010 Vote Percentage | Pop 2000 | Estimated Population 2010 | Change from 2000 | Deviation from Ideal | % Deviation |

| 1 | Dem | Timothy Bishop | Yes | 50.05 | 654,360 | 713,122 | 58,762 | -4,586 | -0.64% |

| 2 | Dem | Steve Israel | Yes | 56.60 | 654,360 | 687,889 | 33,529 | -29,819 | -4.15% |

| 3 | Rep | Peter King | Yes | 72.00 | 654,361 | 653,477 | -884 | -64,230 | -8.95% |

| 4 | Dem | Carolyn McCarthy | Yes | 53.70 | 654,360 | 657,810 | 3,450 | -59,897 | -8.35% |

| 5 | Dem | Gary Ackerman | Yes | 62.40 | 654,361 | 699,143 | 44,782 | -18,565 | -2.59% |

| 6 | Dem | Gregory Meeks | Yes | 94.90 | 654,361 | 654,564 | 203 | -63,144 | -8.80% |

| 7 | Dem | Joseph Crowley | Yes | 79.70 | 654,360 | 673,522 | 19,162 | -44,186 | -6.16% |

| 8 | Dem | Jerrold Nadler | Yes | 75.00 | 654,360 | 695,491 | 41,131 | -22,217 | -3.10% |

| 9 | Dem | Anthony Weiner | Yes | 58.50 | 654,360 | 691,231 | 36,871 | -26,476 | -3.69% |

| 10 | Dem | Edolphus Towns | Yes | 91.00 | 654,361 | 680,793 | 26,432 | -36,915 | -5.14% |

| 11 | Dem | Yvette Clarke | Yes | 90.30 | 654,361 | 668,394 | 14,033 | -49,314 | -6.87% |

| 12 | Dem | Nydia Velazquez | Yes | 92.90 | 654,360 | 688,434 | 34,074 | -29,273 | -4.08% |

| 13 | Rep | Mike Grimm | No | 51.50 | 654,361 | 698,637 | 44,276 | -19,071 | -2.66% |

| 14 | Dem | Carolyn Maloney | Yes | 74.90 | 654,361 | 666,335 | 11,974 | -51,372 | -7.16% |

| 15 | Dem | Charles Rangel | Yes | 79.90 | 654,361 | 661,747 | 7,386 | -55,961 | -7.80% |

| 16 | Dem | Jose E. Serrano | Yes | 95.40 | 654,360 | 684,421 | 30,061 | -33,287 | -4.64% |

| 17 | Dem | Eliot Engel | Yes | 72.10 | 654,360 | 668,910 | 14,550 | -48,797 | -6.80% |

| 18 | Dem | Nita Lowey | Yes | 62.00 | 654,360 | 669,824 | 15,464 | -47,883 | -6.67% |

| 19 | Rep | Nan Hayworth | No | 52.80 | 654,361 | 709,848 | 55,487 | -7,859 | -1.10% |

| 20 | Rep | Christopher Gibson | No | 55.40 | 654,360 | 675,617 | 21,257 | -42,091 | -5.86% |

| 21 | Dem | Paul Tonko | Yes | 59.30 | 654,361 | 660,109 | 5,748 | -57,599 | -8.03% |

| 22 | Dem | Maurice Hinchey | Yes | 52.40 | 654,361 | 662,365 | 8,004 | -55,342 | -7.71% |

| 23 | Dem | Bill Owens | Yes | 48.10 | 654,361 | 652,743 | -1,618 | -64,965 | -9.05% |

| 24 | Rep | Richard Hanna | No | 52.90 | 654,361 | 633,497 | -20,864 | -84,210 | -11.73% |

| 25 | Rep | Ann Marie Buerkle | No | 50.20 | 654,361 | 646,863 | -7,498 | -70,845 | -9.87% |

| 26 | Rep | Christopher Lee | Yes | 73.80 | 654,361 | 646,879 | -7,482 | -70,829 | -9.87% |

| 27 | Dem | Brian Higgins | Yes | 60.80 | 654,361 | 624,284 | -30,077 | -93,423 | -13.02% |

| 28 | Dem | Louise Slaughter | Yes | 65.20 | 654,360 | 604,913 | -49,447 | -112,795 | -15.72% |

| 29 | Rep | Thomas Reed | No | 56.50 | 654,361 | 647,243 | -7,118 | -70,465 | -9.82% |

As the table makes plain, Districts 1 through 19 will need to lose one seat, while districts 20 through 29 will lose the second seat. Though District 28, represented by Louise Slaughter, and District 27, represented by Brian Higgins, are the farthest below the new ideal of 717,707, it will require 10 districts becoming only 9 to make upstate districts conform to population equality. Similarly, even though most districts in the downstate area have been growing, the 19 downstate districts will need to become 18 to leave New York with the 27 seats to which it is entitled.

Thanks to the new census count, New York state is now in for two separate games of musical chairs to find out which representatives will no longer have seats to call their own.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Likely to Offer Accurate Count of New Yorkers

Photo by Quinn Dombrowski

The 2010 census appears to be on its way to be a major success for New York City. We should be grateful for the unprecedented engagement of community, neighborhood and ethnic organizations, as well as adequate funds for communication, outreach and advertising. This all led to a substantial increase in the rate of initial mail response for New Yorkers. When the state population counts that determine the number of seats in Congress are released on Dec. 28t and the block level data for reapportionment for legislative districts are released in March, New York City should do quite well.

The initial response rate rose from 57 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2010 in New York City. The overall national rate stayed the same at 72 percent.

The increased initial participation in the city means both better data and cheaper data collection. When people respond to the initial mailing, the Census Bureau does not have send out enumerators to knock on doors and collect the information, saving money.

While some households that do not respond become "hard to count," the largest fraction of households visited by enumerators easily provided information when contacted, some even apologizing for not sending in their form on time. Other housing units whose residents did not respond proved to be vacant. Enumerators revisited any vacant units to confirm that no one lived there.

Filling in the Gaps

Of course, in any huge operation like the census there are bound to be glitches here and there, but the Census Bureau established built in checks to assure accuracy. Most of the error and difficulties encountered by some census enumerators will be corrected during the quality control phase. For instance, any home that had an incorrect address was rechecked, and a small sample of households is being reinterviewed to validate the accuracy of the original count. Checks also exist to eliminate duplicate responses for those who filled out the form in more than one residence.

Despite the relative success and the efforts at quality control, some groups are very difficult to interview, leaving some missed homes and some incorrect or inconsistent information. To address this, the Census Bureau has a number of procedures it follows when it cannot get an interview or the response is either not complete or inconsistent with other responses from the household. These technique, based on statistical methods, come under the heading "imputation and allocation. "

There are two types of imputation and allocation:

Whole unit imputation comes into play when there is no answer for a unit known to be occupied. In such cases, the census applies what is known as the "hot deck" procedure and determines -- or imputes -- the characteristics of the household from those of other nearby households.

The term "hot deck" harkens back to the time when computers used punched cards. The hot deck contained information on those who were recently tabulated from the same neighborhood living in the same type of unit. Such data still exists -- even if the hot deck does not -- and is used to fill in information on nearby, missing with similar known characteristics.

The other method is "item and person allocation," where a household has provided answers, but they either incomplete answers or include inconsistencies. Here the information on the occupants that do exist is used to impute, much as the "hot deck'" was for the vacant unit So one can impute sex by using first name, if it is known. A Committee of the National Academy of Sciences discussed and reviewed these census procedures.

The New York Data

In the past, New York City has relied more on imputed data than the U.S. as whole has. The table below presents information on the imputation of basic characteristics in the city in 2000. The census reported that 4.7 percent of the housing units' vacancy statuses were imputed. In 8.9 percent, it imputed whether or not the unit was owned or rented. This compares with 2.6 percent for vacancy and 4.8 percent for owned or rented nationally.

| United States | New York City | Bronx | Kings | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island | |

| Overall Person Imputations | |||||||

| Any Item Imputed | 10.9% | 20.0% | 26.4% | 22.3% | 16.5% | 17.8% | 10.6% |

| Population Substituted | 1.2% | 3.9% | 5.7% | 5.4% | 1.2% | 3.4% | 1.5% |

| Specific Imputations | |||||||

| One or more items Impurted | 9.6% | 16.1% | 20.7% | 16.9% | 15.2% | 14.3% | 9.1% |

| Race Impurted | 4.0% | 7.4% | 12.3% | 6.9% | 7.1% | 5.9% | 3.7% |

| Hispanic Impurted | 4.4% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 7.5% | 5.6% | 6.2% | 4.1% |

| Sex Impurted | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 1.7% | 0.9% |

| Age Impurted | 3.7% | 5.8% | 5.9% | 6.7% | 5.7% | 5.3% | 3.5% |

| Relationship Impurted | 2.1% | 3.6% | 3.9% | 4.2% | 2.8% | 3.5% | 2.0% |

| Housing Imputations | |||||||

| Vacancy Impurted | 2.6% | 4.7% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 4.0% | 5.7% | 3.1% |

| Tenure Impurted | 4.8% | 8.9% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 5.8% | 8.0% | 5.1% |

| Source: Census 2000 Tabulation From Summary File 1. | |||||||

As to imputation for persons, some 20 percent of New York City's 2000 population had at least one item imputed, compared with 10.8 percent for the United States as a while For example, in New York City 11.3 percent of people had their race imputed, versus 5.2 percent for the United States . In the Bronx, the figures are 26.4 percent for any imputation, and 16.0 percent for race..

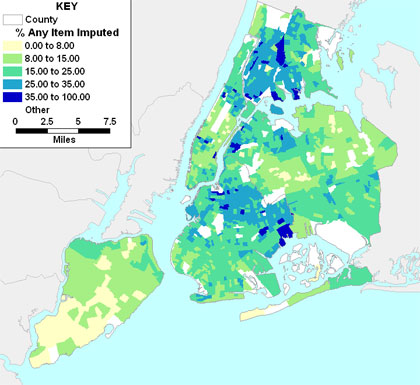

Imputation varies widely throughout the city, as the table and map show. Areas with high proportions of poor and minority households, such as much of the Bronx, Bedford Stuyvesant, Flatbush and Harlem, as well as heavily immigrant area like Northwest Queens have high levels of imputation. In most of Staten Island and parts of Queens, and of Manhattan levels of imputation are low.

<br/ >

<br/ >

Imputation makes up for many of the problems in data collection, including non-response and inaccurate or misleading information. It improves the quality of the census and the overall results by filling in holes and fixing other problems.

Since 1980, many have argued for statistical adjustment of the Census based upon sampling of the "hard to count" population. The Supreme Court has ruled against adopting this approach. The census has used imputation and allocation since 1960. So in a later ruling the court found that such methods were a legitimate means to improve the count.

What then of the 2010 census? First, it seems to have done even better in New York than the 2000 Census. Like the 2000 census, 2010 will prove to be better than the 1990 census, which missed on the order of 400,000 New Yorkers. Second, the various quality control methods will help assure accurate information. Third, the use of allocation and imputation means that even where there are gaps or inconsistencies in the collected data, the data will be improved, so the census will be even more reliable. In short, the 2010 Census is shaping up to be very accurate and reliable.

You can count on it!

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Census Likely to Offer Accurate Count of New Yorkers

Photo by Quinn Dombrowski

The 2010 census appears to be on its way to be a major success for New York City. We should be grateful for the unprecedented engagement of community, neighborhood and ethnic organizations, as well as adequate funds for communication, outreach and advertising. This all led to a substantial increase in the rate of initial mail response for New Yorkers. When the state population counts that determine the number of seats in Congress are released on Dec. 28t and the block level data for reapportionment for legislative districts are released in March, New York City should do quite well.

The initial response rate rose from 57 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2010 in New York City. The overall national rate stayed the same at 72 percent.

The increased initial participation in the city means both better data and cheaper data collection. When people respond to the initial mailing, the Census Bureau does not have send out enumerators to knock on doors and collect the information, saving money.

While some households that do not respond become "hard to count," the largest fraction of households visited by enumerators easily provided information when contacted, some even apologizing for not sending in their form on time. Other housing units whose residents did not respond proved to be vacant. Enumerators revisited any vacant units to confirm that no one lived there.

Filling in the Gaps

Of course, in any huge operation like the census there are bound to be glitches here and there, but the Census Bureau established built in checks to assure accuracy. Most of the error and difficulties encountered by some census enumerators will be corrected during the quality control phase. For instance, any home that had an incorrect address was rechecked, and a small sample of households is being reinterviewed to validate the accuracy of the original count. Checks also exist to eliminate duplicate responses for those who filled out the form in more than one residence.

Despite the relative success and the efforts at quality control, some groups are very difficult to interview, leaving some missed homes and some incorrect or inconsistent information. To address this, the Census Bureau has a number of procedures it follows when it cannot get an interview or the response is either not complete or inconsistent with other responses from the household. These technique, based on statistical methods, come under the heading "imputation and allocation. "

There are two types of imputation and allocation:

Whole unit imputation comes into play when there is no answer for a unit known to be occupied. In such cases, the census applies what is known as the "hot deck" procedure and determines -- or imputes -- the characteristics of the household from those of other nearby households.

The term "hot deck" harkens back to the time when computers used punched cards. The hot deck contained information on those who were recently tabulated from the same neighborhood living in the same type of unit. Such data still exists -- even if the hot deck does not -- and is used to fill in information on nearby, missing with similar known characteristics.

The other method is "item and person allocation," where a household has provided answers, but they either incomplete answers or include inconsistencies. Here the information on the occupants that do exist is used to impute, much as the "hot deck'" was for the vacant unit So one can impute sex by using first name, if it is known. A Committee of the National Academy of Sciences discussed and reviewed these census procedures.

The New York Data

In the past, New York City has relied more on imputed data than the U.S. as whole has. The table below presents information on the imputation of basic characteristics in the city in 2000. The census reported that 4.7 percent of the housing units' vacancy statuses were imputed. In 8.9 percent, it imputed whether or not the unit was owned or rented. This compares with 2.6 percent for vacancy and 4.8 percent for owned or rented nationally.

| ' | United States | New York City | Bronx | Kings | Manhattan | Queens | Staten Island |

| Overall Person Imputations | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Any Item Imputed | 10.9% | 20.0% | 26.4% | 22.3% | 16.5% | 17.8% | 10.6% |

| Population Substituted | 1.2% | 3.9% | 5.7% | 5.4% | 1.2% | 3.4% | 1.5% |

| ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Specific Imputations | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| One or more items Impurted | 9.6% | 16.1% | 20.7% | 16.9% | 15.2% | 14.3% | 9.1% |

| Race Impurted | 4.0% | 7.4% | 12.3% | 6.9% | 7.1% | 5.9% | 3.7% |

| Hispanic Impurted | 4.4% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 7.5% | 5.6% | 6.2% | 4.1% |

| Sex Impurted | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 1.7% | 0.9% |

| Age Impurted | 3.7% | 5.8% | 5.9% | 6.7% | 5.7% | 5.3% | 3.5% |

| Relationship Impurted | 2.1% | 3.6% | 3.9% | 4.2% | 2.8% | 3.5% | 2.0% |

| ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Housing Imputations | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Vacancy Impurted | 2.6% | 4.7% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 4.0% | 5.7% | 3.1% |

| Tenure Impurted | 4.8% | 8.9% | 12.4% | 11.0% | 5.8% | 8.0% | 5.1% |

| Source:' Census 2000 Tabulation From Summary File 1. | |||||||

As to imputation for persons, some 20 percent of New York City's 2000 population had at least one item imputed, compared with 10.8 percent for the United States as a while For example, in New York City 11.3 percent of people had their race imputed, versus 5.2 percent for the United States . In the Bronx, the figures are 26.4 percent for any imputation, and 16.0 percent for race..

Imputation varies widely throughout the city, as the table and map show. Areas with high proportions of poor and minority households, such as much of the Bronx, Bedford Stuyvesant, Flatbush and Harlem, as well as heavily immigrant area like Northwest Queens have high levels of imputation. In most of Staten Island and parts of Queens, and of Manhattan levels of imputation are low.

<br/ >

<br/ >

Imputation makes up for many of the problems in data collection, including non-response and inaccurate or misleading information. It improves the quality of the census and the overall results by filling in holes and fixing other problems.