DNA Redux

As reported in the Gotham Gazette last month, NYPD Police Commissioner Howard Safir has said DNA testing, which uses samples of genetic material to identify potential suspects, could revolutionize law enforcement, if only legislators would catch up to the technology. He's just gotten his wish. On February 23rd, Governor Pataki proposed new laws that would broadly expand the use of DNA in solving crimes. These proposals, the most aggressive measures in the country, would eliminate the statute of limitations on sixteen felonies and allow police to collect DNA samples from anyone convicted of a crime.

As in most U.S. states, current New York law restricts the use of DNA testing. Only those convicted of the most serious felony cases (about 65% of all felonies) must provide samples, and, with the exception of murder, crimes can only be prosecuted up to five years after they're committed. But DNA samples can reliably identify or clear a suspect well after five years' time, and can link an inmate convicted of one crime to others.

DNA testing has been a hot media topic in recent weeks. In a long piece for City Journal, Commissioner Safir championed DNA testing as a crime-fighting tool. In the pages of Newsweek, the founders of the Innocence Project, a legal center that seeks to overturn mistaken death row sentences, argued that making testing more accessible could help free many inmates who have been wrongly imprisoned. And in an article the Governor said influenced his decision to submit his proposals, the New York Times reported on rape cases in which DNA had identified suspects who could no longer be prosecuted under the statute of limitations.

It's not yet clear how the State Legislature, controlled by Democrats who have rejected some of the Governor's previous criminal justice initiatives, will vote on the new proposals. But with DNA on a fast track from obscurity to the top of New York's criminal justice agenda, don't be surprised to see DNA crime labs getting a lot of funding and attention.

Jerome Sounds Off:

"Verdicts do not send messages," defense attorneys in the Diallo trial told jurors, but of course we know better. The acquittals jurors handed out in Albany last Friday may have been based on sound legal judgment, but they still send a terrible message, especially to those living in the City's minority neighborhoods: no one was at fault in this case. What other response can you expect from the thousands who marched in demonstrations this past weekend? You feel either sadness or terrible rage.

What we need, then, is someone to step forward and deliver another message. Where do we go from here? The Reverend Calvin Butts, no stranger to political opportunism, called on his congregation to work against Mayor Giuliani's probable Senate run. Al Sharpton, who so effectively galvanized protestors last year, suggested a vague, untargeted boycott. Both men fanned their audiences' anger and resentment.

They've got that part right. But now's the time to turn heated emotions into something lasting, a way to change police practices in the City. We can expect the Mayor and Police Commissioner will do nothing until something forces their hand, as protesters did last year. There's no end of specific proposals that public pressure could highlight. Provide more funding for the CCRB and demand a commitment from the Commissioner to disclose how he's punishing officers guilty of abusing their power. Take former Commissioner William Bratton's suggestion to reduce the size of the force by 5,000 officers, allowing more training for those remaining. Curb the Street Crime Unit (a long overdue change that Comissioner Safir began last October when he shut down the infamous squad's headquarters and created eight separate units).

Community leaders could also take on a very unglamorous, time-consuming, and painstaking mission: working with community residents to hold their local precincts accountable. As Eli Silverman, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice wrote in the Gotham Gazette last year, "Like most citizens who hold Congress in low esteem but highly value their own Representative, many New Yorkers...resent the [NYPD] but seek more contact with their own beat officer." If the NYPD wants to win back some trust, and residents want to gain some sense of control over how their neighborhood is policed, one place to start is in community meetings with the precinct commander.

Normally, the precinct meetings held regularly across the city are a charade between self-appointed community VIPs and precinct commanders who play good cop for the evening. But a strong, coordinated group can put legitimate issues on the table and give residents and officers a chance to interact with each other outside of traditional roles.

Admittedly, it takes a little wishful thinking to imagine that people all over the city could be mobilized to improve the performance of their local police precincts. But after the painful unfolding of events this past weekend, I think we're entitled to it.

Jerome Chou is a freelance writer. He works part-time interviewing recently released ex-offenders about their re-entry into society.

Repeat Offenders

Paris Drake is accused of a senseless and brutal crime on a busy Midtown street in broad daylight. Whether or not he is convicted of bashing a woman's head with a brick, his arrest has highlighted the criminal justice system's failure to deal with repeat offenders.

Before the alleged attack, Drake had been jailed more than twenty times and was a free man for exactly 17 days out of the last eight years. Like many of his fellow inamtes, Drake was arrested several times on drug-related charges (an estimated 70% of the City's 70,000 inmates have a history of drug abuse). Most of his crimes were misdemeanors, which typically bring sentences of only a few weeks or months in jail.

Clearly, the system doesn't work for Drake and thousands of others who spend years cycling in and out of prison. Prison advocates call for more drug programs, but too often inmates themselves complain that these programs don't work. Most of the ex-cons I spoke to in a recent study of parole--even those who insisted they needed help to stay clean--ridiculed the rehab programs available to them. Some skipped out without consequences. When Drake, for instance, was finally ordered to seek treatment after years of revolving-door prison stints, he blew it off.

Mayor Giuliani and Governor Pataki have called for a kind of "three strikes and you're out" policy that would mandate longer sentences for repeat offenders after a certain number of misdemeanors in a given time period. Steven M. Fishner, the mayor's criminal justice coordinator, has said "It is for people like Paris Drake, for offenders who sell marijuana repeatedly in city parks, and for others who make a career of committing crimes and skating under the mandatory sentences for felonies."

Such a plan might please prison-happy public officials, but probably won't change criminal behavior. Why not? The motivation needed to go straight is extremely difficult to manufacture, whether you're giving inmates a boot camp regimen or drug programs, long terms upstate or slap-on-the-wrist sentences. The problem is, for those ex-cons who are determined not to return to prison, it's difficult to find a job that pays the bills, and exceedingly easy to get back into crime, especially selling and using drugs. Until this balance changes--perhaps by making effective pre-release programs a priority--no proposal to reduce the number of repeat offenders is likely to succeed.

Jerome Sounds Off:

Quality of Life Crime #54: Selling cheap goods on the subway. (Good thing too, since mostly recent Chinese immigrants are in that racket nowadays, and with their mangling of the language and their haggard countenances, these people are comical at best, downright disturbing if you're in a bad mood. Not the kind of thing you want the tourists to see. Plus, they're cutting into Duracell and Doublemint sales at legitimate rent-paying stores. And remember the "broken-windows" theory Ð today they're selling yo-yos, tomorrow they're hawking stolen watches, pretty soon they're robbing you at gunpoint when you try to take the train! That's why I'm glad I saw a sting operation last week--six uniformed and two plainclothes officers nabbing two guys who, I was told, make thousands of dollars a week selling $1 batteries. It's a good thing these crooks are off the streets now, but not before pocketing our hard-earned George Washingtons and menacing our quality of life.)

Jerome Chou is a freelance writer. He works part-time interviewing recently released ex-offenders about their re-entry into society.

Strip Searches

City officials have settled a lawsuit alleging the New York Police Department improperly strip-searched people arrested for minor offenses in Brooklyn, agreeing to pay $650,000 to 20 plaintiffs in the case. But the jury remains out on whether strip-searches are being used by police only in special circumstances for safety and to collect evidence, or as a matter of routine.

The settlement of the suit contrasts sharply with the 2001 settlement of a similar case involving alleged wrongdoing in Manhattan and Queens, when the city agreed to pay up to $50 million in a class-action suit. In that case, the city conceded its Corrections Department illegally strip-searched tens of thousands of people held in custody on minor charges during a ten-month period in 1996 and 1997.

Federal courts have ruled since the 1980s that strip-searches are allowed for those arrested for minor crimes only under special circumstances, such as when police have reason to suspect a detainee may have a hidden weapon or contraband, usually drugs.

In settling the Brooklyn case, the city has admitted no wrongdoing, although statements from those plaintiffs involved in the suit describe how they were humiliated after being arrested for misdemeanor crimes, sometimes publicly strip-searched in view of other inmates and officers of the opposite sex.

Police policy says strip searches, when necessary, should be "conducted by a member of the same sex as the arrested person in a secure area in utmost privacy and with no other arrestee present."

Yet the lawsuit and a report(in pdf format) issued in May by the Civilian Complaint Review Board paint a far different picture. The board investigated dozens of complaints filed since 2002, and found that in 2003, they were substantiated at a rate of about 19 percent.

Twelve strip-search complaints were substantiated by the review board last year. Through July of this year, the board has substantiated 14 strip-search complaints.

While those overall numbers are small, officers interviewed by the Civilian Complaint Review Board in response to complaints often described strip-searches as routine and necessary to look for drugs, even if the person was arrested for different reasons. This led the review board to express concern that the problem was more wide-spread than the number of complaints might suggest.

The review board sent a letter to Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly calling for better training of officers on how to conduct strip-searches and when strip-searches were permissible. Police officials have responded by saying that a new training video has been under development to give officers a better grasp of department policies on strip-searches.

Those involved in the lawsuit described their disappointment in the settlement to The New York Times.

One man in the Brooklyn lawsuit described for the Times how he was strip-searched after a traffic accident in which he was arrested on suspicion of having a suspended license. He described the crowded, dirty conditions of the holding cell, and then being asked to drop his pants in view of female officers.

"When the lawyers offered [the settlement] to me," the man told The Times, "they said, 'That's not bad for one night.' I said, 'You go try it.' I'm a knockaround guy. That night was pretty horrible."

When and how police conduct strip-searches have been questions raised by similar lawsuits across the country, and even the definition of "strip" search is not completely clear. Some legal scholars wonderexactly how much of a right people have not to be strip-searched.

But aside from when and where strip-searches are allowed, federal courts have ruled in similar cases this year that in order to reach class-action status -- and be eligible for multi-million dollar payouts, like the 2001 lawsuit -- the plaintiffs must prove that they are likely to be harmed in the future by police strip-searches. If those involved in the lawsuit were only involved in minor crimes, then it is unclear that those involved would be arrested again and subjected to similar treatment, according to the explanation presented by The Times.

What Goes In Must Come Out

What goes in must come out. Sasha Abramsky's "When They Get Out," in June's Atlantic Monthly, considers how booming incarceration rates have affected our society, and speculates about what will happen when these prisoners are released. The article focuses on national trends (in twelve states, for instance, ex-offenders can never vote again, which may lead to widespread disenfranchisement), but the implications for New York are obvious. One organizer estimates that beginning in the year 2005, New York's prisons will release about 30,000 inmates a year -- people who will have a hard time finding work and medical care. Abramsky asks important questions about a problem we've swept under the rug, but one we'll have to face up to eventually.

Jerome Sounds Off:

41 bullets, 1000 arrests, and countless Mayoral defensive postures later, what have we learned from the City's police brutality crisis? The infamous Street Crime Unit now sports uniforms -- not that the City's minority residents had too much trouble spotting groups of beefy white guys cruising their neighborhoods. Meanwhile, according to a recent poll, 25% of New York's white voters consider police brutality a "serious problem," compared to 81% of black voters. Despite the unlikely multiracial coalition that rallied around Al Sharpton's City Hall protests, as the chant goes, "No justice, no peace" -- at least not until both sides acknowledge common ground. Shrill activists have their sound bites. But who's speaking for residents of poor neighborhoods, who want more, not fewer, cops on the beat? And when will the Mayor and the Commissioner acknowledge the systemic racism that plagues the force? Sit back, we'll be here a while.

Jerome Chou is a freelance writer. He works part-time interviewing recently released ex-offenders about their re-entry into society.

The Uniqueness of Dante de Blasio

As New York took in the extent of the win by Bill de Blasio in the Democratic primary for mayor, the impact of a powerful television ad starring his son Dante seemed plain.

The ad hit on de Blasio’s main campaign points of taxing the wealthy, ending a “stop-and-frisk era that unfairly targets people of color” and universal pre-K. But it was the messenger that made it a show-stopper: A mixed-race kid with an exuberant Afro speaking to the camera about how his dad was “the only Democrat with the guts to really break with the Bloomberg years.”

De Blasio’s wife is a black woman, and both Dante and Chiara (his daughter) are mixed race. With his family and the ad featuring his son playing key roles in his campaign, de Blasio split the black vote almost evenly with former comptroller Bill Thompson., the only black candidate for mayor

Remember, in the primary between Hillary Clinton and Obama, who is mixed race, in 2008 Hillary Clinton did better among white and Hispanic voters than she did overall, and Barack Obama won the black vote by a very wide margin in an overall close race. In terms of who voted for whom, race mattered.

{sidebar id=14}

As Joe Lenski, the man behind the exit polls, said in the Daily News, "I don't know if I could ever remember a race where a black guy is (close to) losing the black vote, the woman is losing the woman vote, the Jewish guy is losing the Jewish vote. It's quite impressive .... De Blasio did a good job of saying, 'I'm one of you even though I'm not personally one of you.' He was able to say, 'my wife is African-American, my kids are multiracial."

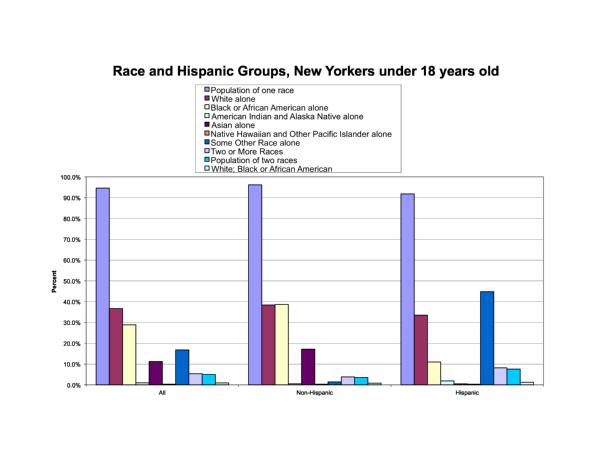

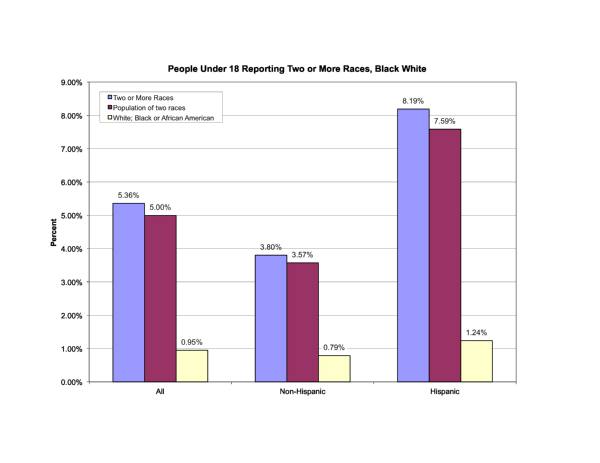

How unique is Dante de Blasio, the 16-year-old superstar of the 2013 elections, who communicated this important message? Just how many New Yorkers are non-Hispanic males who would identify themselves as black and white? An analysis of 2010 Census data shows that very few young New Yorkers are black and white, and even fewer are non-Hispanic black and white. Furthermore, there are much lower proportions of such individuals in New York City in the country at large. These data are presented in the accompanying table, and some are summarized in the two charts below.

For those under 18, there are 94,731 who report being of two or more races; 88,321 of these are of two races, and 16,735 are black and white. When one looks at those reporting that they are non-Hispanic black and white, there are only 8,980. Dante, it is plain, is in a very small group. However, these number also are self-reports; as has become obvious during the last few years, the genetic make-up of individuals does not necessarily mirror their self-reports.

The two charts also make it plain that the city has a lower proportion of multi-racial young people than does the United States in general; this is particularly true with respect to those reporting black and white. In the US as a whole, some 1.67 percent of youth are reported to be black and white, while in New York City the figure is 0.94 percent. (Other comparisons are in the accompanying table.)

But it’s clear that while Dante de Blasio may belong to a small group, the message he delivered was tailored for a much broader audience. It came in the midst of a contentious federal trial over whether the policy was unconstitutionally targeting black and Latinos.

Despite constant refrains by Bloomberg, Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly and some of the media to the contrary, the judge in the stop-and-frisk case, Shira Schiendlin, based her assessment of the practice on expert and factual testimony. Specifically, she drew her opinion on evidence that the police stops young blacks and Latinos disproportionately not only in terms of race and Hispanic status, but also in the neighborhoods that they tend to live in, and in terms of the crime rate in those neighborhoods.

Criminologist Jeffrey Fagan, the plaintiff’s expert in the case, in an article in the Columbia Law Review, has demonstrated that teenagers like Dante — who are perceived as black even though they may be mixed-race — have an 80 percent chance of being stopped. According to father de Blasio, he has discussed this with Dante at length to try to lessen his chances of being stopped.

Plainly, Dante’s uniqueness and the de Blasio family’s uniqueness, along with de Blasio’s position, which plainly attempt to address directly the concerns of many blacks and Latinos in New York City, helps to explain de Blasio’s electoral success.

But while the messenger may have been unique, it was the message that more than likely swayed voters to cast their ballots for his dad. Dante’s uniqueness and the powerful ad just made it possible for the message to get through.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer (www.socialexplorer.com), a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. He is co-editor of “New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future” (Oxford University Press, 2013). The opinions expressed are his alone.

New York’s Changing Electorate: What It Means for the Mayoral Candidates

Most New York citizens of voting age do not vote — and they definitely do not vote in mayoral primaries or elections.

That means this year’s candidates, If they have any hope of getting to Gracie Mansion, will need to build coalitions of supporters willing to get to the polls on primary day and Election Day from an increasingly diverse voter roll.

When Barack Obama beat Mitt Romney for President in 2012, less than 50 percent of those in the city who could have qualified to vote did so, with some 2.5 million votes cast. When Michael Bloomberg beat former Comptroller Bill Thompson for mayor in 2009, only 24 percent of those who could have voted did so, with approximately 1.2 million votes cast. The ratios were similar for every election since 1989.

The record in primaries is even worse. In the contested Democratic and Republican primaries for president in 2008, less than 1 million votes were cast or about 20 percent. In the Democratic primary for mayor in 2009, only 330,000 votes were cast — which would mean that only about 11 percent of registered voters — and less of all of those who could enroll and probably would enroll as Democrats bothered to turn out.

New York City has roughly 4.3 million registered active voters and an additional 375,000 inactive voters as of April 2013. So registration of active voters is about 86 percent of citizen of voting age population. However, that number is misleading, since beyond the inactive voters, about 23 percent of NYC registrants are characterized as deadwood for either having moved or died since they registered.

In short, only small fractions of New Yorkers who could vote do vote, and many are not even registered.

Turnout isn’t the only challenge facing candidates; they also must deal with the diversity of the electorate.

Since David Dinkins was elected mayor in 1989, the New York City electorate has also changed substantially both racially and ethnically. Immigrants and their children — many of whom are either Hispanic or non-white — are now eligible to vote, while the proportion of non-Hispanic white voting age citizens in New York City continues to decline.

This shift, however, has yet to propel a non-white candidate to the mayoralty since Dinkins, though it is plain from the candidacies of Fernando Ferrer in 2005 and Thompson in 2009 that Hispanics and blacks will vote for one of their own.

Most notably, the proportion of the electorate that is non-Hispanic white has dropped from 54 percent in 1990 to about 42 percent for the latest year. Most likely it has declined even more since then.

At the same time, the percent of the electorate that is non-Hispanic black has declined to about 24 percent after increasing slightly from 1990 to 2000. Meanwhile, the Hispanic electorate has grown from about 18 to 23 percent, and the Asian electorate has gone from about 4 percent to about 10 percent.

While roughly 90 percent of voting age non-Hispanic white population are citizens, and virtually all Puerto Ricans are citizens, only 26 percent of Mexicans are citizens. For the other Hispanic groups, the range is from the 40 to 60 percent. For instance, about 59 percent of Dominicans over 18 are citizens. (Click to see the tables).

The same pattern holds for the Asian groups. For South Asians, generally about 60 percent of the voting age are citizens, while for the Chinese and Koreans it is also about 60 percent. Both the growth of the immigrant population and the length of time specific groups are in the United States and the extent to which such groups have children and their children become 18 affects the size of the citizen population of each group. So as time goes on, more and more will be citizens and thus have a potential political clout.

The South Asian group is now about 2 percent of the electorate, the Dominicans and Chinese are both about 5 percent, while the Puerto Ricans are 11 percent. All of the other groups are no more than about one percent — and often much smaller. Of course, they are larger in certain areas, but only in a few cases do they approximate an absolute majority.

What then are the general implications of these changes in the electorate and the fact that so few New Yorkers vote in the Mayoral and other local elections?

First, registration of citizens in any group is very important. Due to the limitations of the enrollment data (birthplace is not collected and the count is not an accurate reflection of who is actually in the city and registered to vote), it is very difficult to understand exactly what the registration level is for citizens for each group.

However, getting those who can to file citizenship applications and then get them registered is critical. Once they are enrolled, for a group to maximize its influence it is necessary for them to turnout and vote.

At the same time, because non-Hispanic white electorate has declined to near 40 percent, winning an election means that other groups must work in coalition. If the new groups are split apart or split among themselves and one or more candidates from each group runs a campaign that does not reach across groups, they will undoubtedly lose.

This is a lesson that John Liu learned when he unsuccessfully ran for City Council in 1997. He faced two other opponents of Chinese descent, and challenged an incumbent who famously characterized the increase of Asians in the Flushing area, as an invasion. It was also a hard-earned lesson in the 2001 election when term limits forced a large turnover in the City Council but the number of seats won by community and ethnic activists was very few.

Though the growth of immigrant and ethnic groups can empower such groups, to win elective office usually requires reaching across groups and ethnic divisions and fashioning a winning coalition. It is also means getting members of those groups through the citizenship process, registered and to the polls.

That last step — identifying and getting voters to the polls — is just as important to any candidate as gaining wide public recognition and developing a favorable image. This year’s election may have a high turnout for a primary, but a high turnout would be anything just above 15 percent of those eligible to vote.

Now that New Yorkers are beginning the process of choosing a mayor, looking at the data on the changing electorate simply reinforces the fact about how broad the appeal must be to win elected office in New York City.

Not only do Republican candidates need to go beyond the 16 percent of electorate who enroll in the GOP as Bloomberg and Rudy Giuliani did, but Democratic candidates need to get support beyond their ethnic group and local area to even have chance.

Given all of this, it is not surprising that few are certain where the current election will go, either during the primary in September, the likely Democratic runoff, or the final election in November.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer (www.socialexplorer.com), a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. He is co-editor of “New York and Los Angeles: The Uncertain Future” (Oxford University Press, 2013). The opinions expressed are his alone.

What The Next City Council Will Likely Look Like

The next City Council will likely be demographically similar to the current one, though there may be an increase in both Asian and Latino membership.

That is one of the main takeaways from a review of the new Council lines approved by the city’s Districting Commission on Thursday but not released to the public until the following day.

A further look at the plan shows that it continues to protect incumbents, but was adjusted to accommodate some of the preferences of community and minority group advocates and others who complained loudly about the preliminary plan.

In addition, Lisa Hadley, a noted analyst of voting patterns in the context of redistricting, assessed the plan for any vulnerability to challenge by the Department of Justice and by Minority Voting Rights advocates and found that it unlikely to raise any issues.

Incumbency Protection

On average the new districts retain slightly over 87 percent of the population of the current districts, and 41 districts have at least 80 percent of that population.

Overall the plan continues the time honored tradition of incumbency protection, but it is worth noting that such concern for incumbents has been found by the Supreme Court to be a legitimate basis for redistricting.

However, there were noteworthy changes to districting lines that addressed concerns of critics.

A look at the data shows that a set of districts in northern Manhattan and the Bronx had large changes from 2003 to the new lines: Districts 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, and 15. It is also plain that 7, 8, 10, 14, 15, and 17, were changed substantially between the preliminary and the final plan.

This accommodates Hispanic and African American population change.

There was also substantial change between the current lines and the final lines, in Queens for Districts 25, 29, 32, and for District 39 in Brooklyn. Districts 25, 29 and 32 were modified substantially from the preliminary plan. Along with District 28, these changes satisfied some of the issues raised by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Nonetheless, the basic pattern except for the 10 districts noted, was for a plan that would serve to protect the incumbents or their likely successors.

Voting Rights Issues

Like many southern states and counties, the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn are subject to so-called pre-clearance by the Department of Justice.

This is to ensure that any changes to the voting system do not disadvantage minority groups: African Americans, Hispanics and Asians.

Generally a plan is tested to see if there is retrogression, which means that one would expect that fewer seats would be held by candidates of choice of minority groups.

The commission hired Lisa Hadley to conduct an analysis to assess whether the final plan met such a criterion. (I should note that in several cases, including a recent case in Port Chester, Lisa Hadley and I testified for the same parties. My work was more in formulating and analyzing the demographics of redistricting plans, while Lisa Hadley analyzed voting patterns.)

Hadley’s analysis finds that the plan passed by the redistricting commission preserves at least the same number of seats, where minorities will elect their candidate of choice compared to the current plan in the three covered counties.

I agree with Hadley on this, the plan will return a Council very similar demographically to the current council, though their may be an increase in both Asian and Latino membership.

A Jigsaw Puzzle

Redistricting for any jurisdiction is a series of tradeoffs among incumbency protection while following the five principles I outlined in an earlier column.

How these principles, along with incumbency protection, are implemented in practice depends on who is doing the map drawing. Redistricting is a bit like completing a jigsaw puzzle. All territory must go somewhere.

New York City redistricting is done by a Commission where a majority of members are appointed by the Council, while many of the mayoral appointees also have been very active politically. Though not exactly the same as being drawn by the Council itself, the Council still must approve the plan, and those in charge of drawing the map are beholden to the Council for their appointments.

If we had true non-partisan (as opposed to bi-partisan) redistricting in New York City, I am sure that incumbency would not play such a large role. (Indeed, it played little or no role in California, where the state’s recent redistricting was done by an independent non-partisan commission.)

Unless New York City adopts such a procedure, we can expect that the choice of constituents will still be shaped by the incumbents more than by the voters.

____

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer, a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

New Plan For City Council Districts

NEW YORK — A new proposed map for New York City Council district lines addresses some concerns of civil rights groups and reflects changing demographics, while also safeguarding incumbents.

But the Districting Commission was criticized for voting to approve the new plan at a meeting Thursday night before it had even released the information to the public. The full City Council must now approve the new map.

Since the commission also supplied an analysis related to the Voting Rights Act by Lisa Hadley, a renowned expert in that field, it is clear that the revised plan had been crafted days ago and could have been released at the Commission’s discretion.

The above map presents a view of the revised plan for new Council districts, along with whether or not the current incumbent is term limited. Courtesy of Social Explorer.

It took until Friday afternoon for the revised district plan to be posted on the Commission’s website for the public to view it.

Asked why the map was not released to the public before the Commission voted to approve it, the Commission’s executive director, Carl Hum, said there was still time for the public to make its comments on the plan.

“If there is a desire by the public to have more hearings, they can certainly voice that to the Council,” he said. The Council could also reject the lines, forcing the Commission to hold another hearing. “The process is far from over.”

He said that the new map was drawn taking into account comments from the public, civil rights groups and legislators, as well as maps created by members of the public.

Responding to criticism that the lines had been drawn to protect incumbency, he said legislators’ also had a stake in the process. “While not saying that's the primary consideration, or the overarching consideration … It is part of the toolkit,” he said.

>>>>Read Andrew A. Beveridge's analysis of the preliminary maps and how they protect incumbents.

Unlike the state, the city has a non-legislative redistricting commission, which has held hearings and a series of maps.

The commission consists of 15 members — seven appointed by the mayor, five by the Council Democrats and three by the Council Republicans. One third of the commissioners are from Manhattan, which has about one-fifth of the population, two from the Bronx and Brooklyn each, and three from Staten Island and Queens each.

This structure is seen by some political observers as an advance over the redistricting process at the state level, where legislators themselves were able to draw the lines for the Assembly and Senate lines after Gov. Andrew Cuomo waffled on his promise to veto any maps that were clearly gerrymandered.

Nevertheless, the proposed maps have been criticized for dividing neighborhoods and ignoring communities of shared interest.

>>>View a table about the new districts under the revised plan, including the incumbent, the year elected, term limit status, voting age, citizenship, race and Hispanic status.

The Unity coalition of minority advocates — including LatinoJustice PRLDEF, Asian American Legal Defense And Education Fund, and Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College — presented a common plan that attempted to keep neighborhoods intact and attempted to maximize the influence of African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans on the new Council.

In a statement released after Thursday night’s vote by the Commission, AALDEF noted that under the new proposed map that several Asian American communities remained divided but that some of the Unity Map’s suggestions were taken into account.

Jerry Vattamala, a staff attorney with ALDEF, said in a statement that the Commission’s proposed map “has room for improvement in enabling New York City’s federally protected communities of color to have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.”

___

Image of New York City, seen from space, courtesy of NASA.

Proposed City Council District Map Protects Incumbents

Editor's note: This commentary is based on the preliminary lines that were released before Thursday night's meeting by the Districting Commission. We will be updating it with additional information as it is released.

NEW YORK — The once-a-decade drama of redistricting the New York City Council is almost complete.

Much is at stake, not for party control, but over who will represent many of the city’s increasingly diverse neighborhoods for the next decade beginning with the 2013 election. Redistricting must be undertaken after each federal decennial Census.

The city's Districting Commission, appointed by the mayor and Council leaders to redraw the lines, voted unanimously in favor of a revised plan at a public meeting Thursday night. The new map has not been made available for review. The full City Council must now approve it.

The current Council has 46 Democrats and five Republicans. In 2013, an additional 18 seats will be open due to the impact of the change in the city’s charter regarding term limits. How those districts are drawn will have a lot to do with recruiting new political leadership in New York City for the next decade.

Unlike the state, the city has a non-legislative redistricting commission, which has held hearings and presented preliminary maps of the boroughs.

The commission consists of 15 members — seven appointed by the mayor, five by the Council Democrats and three by the Council Republicans. One third of the commissioners are from Manhattan, which has about one-fifth of the population, two from the Bronx and Brooklyn each, and three from Staten Island and Queens each. The most populous boroughs (Brooklyn and Queens) have almost three-fifths of the population, but the same number of commissioners as Manhattan. Staten Island, with not even six percent of the city’s population, has one-fifth of the commissioners. The commission has an executive director and a staff.

This structure is seen by some political observers as an advance over the redistricting process at the state level, where legislators themselves were able to draw the lines for the Assembly and Senate lines after Gov. Andrew Cuomo waffled on his promise to veto any maps that were clearly gerrymandered.

But since they are appointed by the mayor and the Council, it is perhaps unsurprising that the commissioners charged with redrawing the city's districts would follow the age old practice of “incumbency protection”: In the draft map that was released before Thursday's vote on a revised plan, district lines were tweaked at the expense of splitting some neighborhoods. This is a classic example of protecting those already in office by minimizing the amount of change within district lines — after all, probably the worst thing that can happen to an incumbent is to force him or her to run in a new district.

This seemingly business-as-usual approach appears to be in stark contrast to the Districting Commission’s efforts to be transparent about the process, allow for community input at hearings in the various boroughs and through an invitation to members of the public to submit their own proposed maps. Nevertheless, the proposed maps have been criticized for dividing neighborhoods and ignoring communities of shared interest.

The Unity coalition of minority advocates — including LatinoJustice PRLDEF, Asian American Legal Defense And Education Fund, and Center for Law and Social Justice at Medgar Evers College — presented a common plan that attempted to keep neighborhoods intact and attempted to maximize the influence of African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans on the new Council. Most of their suggestions were spurned, likely because many of them would have made it much more difficult for incumbents to keep their seats, or would have forced incumbents to accommodate themselves to new neighborhoods.

Despite the outcry from the Unity coalition and other groups, the Commission has proposed a plan that is basically same-old, same-old.

The above map presents a preliminary view of the new Council districts, along with whether or not the current incumbent is term limited. Click to enlarge. Courtesy of Social Explorer.

Redistricting Standards

To successfully complete redistricting and not be subject to challenge under federal law, the following principles must be followed:

- Relative population equality — generally, this is interpreted as being within plus or minus five percent of the average or ideal district size based here upon the population adjusted for prisoner locations.

- Contiguity — that the districts are in one piece.

- Compactness — that the districts are compact in shape.

- Political boundaries — that the districts do not split political or community boundaries.

- Given all of the above, that they keep racial and Hispanic communities together.

The fifth provision is very important in New York City, since the Bronx, Manhattan and Brooklyn are subject to pre-clearance by the U.S. Department of Justice. One of the main issues with pre-clearance relates to retrogression, meaning that the number of seats with a majority of the various minority groups from the 2003 districts must result in the same number or more seats unless population change makes this impossible.

It is this last point that has created the presents the biggest challenge to the Commission’s map-making.

Current Districts and Need for Change

Since redistricting is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, that 12 seats need to be adjusted, means that many more than that will be impacted, because the extra population to be added or subtracted from these 12 districts will need to come from or be put elsewhere. So substantial redistricting was necessary.

The Council currently has 2 Asians, 15 blacks, 8 Latinos, and one Black/Latino Councilman. But non-Hispanic whites make up 25 of the 51 seats in the Council. In terms of minority majority seats, the new Council will have nine majority Latino seats, 11 majority African American seats and one seat that is almost majority Asian. There are 21 non-Hispanic white seats and nine with no majority. Of those nine, five are plurality non-Hispanic white and four are plurality Hispanic. Based upon proportional representation by seats, the current Council is over-performing in returning minority districts.

>>>View a table about the new districts under the preliminary plan, including the incumbent, the year elected, term limit status, voting age, citizenship, race and Hispanic status.

The Unity coalition proposed a plan that would result in one more majority black district and one less majority Hispanic district. The Unity coalition asserts that their plan divides fewer neighborhoods. Such changes would be even more disruptive to the current set of incumbents, so was not seriously considered.

Of the council members retiring, six are black, one is black/Latino and two are Latino. In terms of majority seats, four are black, three are Hispanic, seven are majority non-Hispanic white and four have no majority. Of those four, two are plurality non-Hispanic white, and two are plurality Hispanic.

Based upon simple block voting, one might expect fewer black seats and more Hispanic seats. However, the last time that there were a large number of term-limited Council members, the vast bulk were replaced either by staff aides or family members. Few community activists or others could not find the wherewithal to win and sometimes to remain on the ballot.

One should expect that the 2013 election will be no different. Given the limited nature of the redistricting, I would expect that the new Council will maintain just about the same demographic profile as the current Council despite both population shifts and term limits.

____

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer, a premier online demographic web site, has done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993 and has been a contributor to Gotham Gazette since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.

Image of New York City, seen from space, courtesy of NASA.

The Attempt to Kill the ACS: Its Implications for New York City

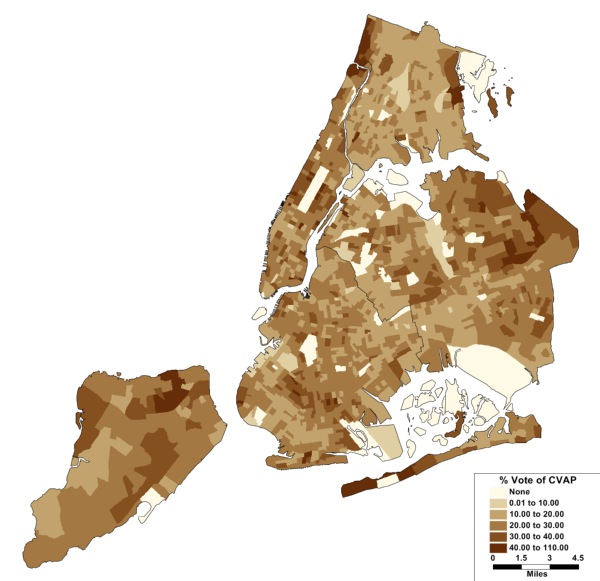

The map is an example of data available through the American Community Survey. It shows median household income from 2000 to 2006-2010. Maps courtesy Social Explorer.

Starting in 2005, the U.S. Census Bureau replaced the long form that the agency had relied on every 10 years to measure change in the nation's demographics with an annual survey that would deliver a much more immediate snapshot of the population. Now we have data that were available only once a decade, every year.

Today, the American Community Survey is used across the country by researchers, businesses and policymakers. Almost anything that a person would want to know about the population of the U.S. – from income to disability – can be found from a review of the data.

For New York City or, for that matter, any community across the country, the ACS is a critical tool for understanding demographic change down to the neighborhood level.

Given its importance, then, it might come as a bit of a surprise that the Republican majority in Congress wants to get rid of the ACS – and has even put forward an amendment to do so – arguing that it represents an unconstitutional invasion of privacy.

“It would seem that these questions hardly fit the scope of what was intended or required by the Constitution,” said Rep. Daniel Webster (R-Fla.), author of the amendment. "This survey is inappropriate for taxpayer dollar… It’s the definition of a breach of personal privacy. It’s the picture of what's wrong in Washington, D.C.”

It should, perhaps be noted, that there is no documented case of identifiable Census information falling becoming public or being used in an unauthorized way.

Compared to the data harvested by Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Amazon, Google, your credit card company and your healthcare provider, Census information is mostly quite benign. However, the ACS does collect information about race, ancestry, income, and marital status.

While the survey is not part of the constitutionally mandated population count, some version of it has been done by law as part of the decennial survey since the time of Thomas Jefferson. Virtually all questions on the current survey are there because of various Congressional mandates.

There has been an outpouring of support for the ACS, including from the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal: “Since the political class is attempting to define the GOP as insane and redefine â€moderation’ as anything President Obama favors, Republicans do themselves no favors by targeting a useful government purpose.”

The Times, in another editorial, pointed out that Webster has a link to ACS data about his district on his own website.

The outright ban is not expected to pass the Senate, but a bill making the ACS voluntary has been introduced there, and has already passed the house.Making the survey voluntary is certainly a possibility and would make it both more expensive to administer and less accurate and valuable, based upon the experience of Canada, which made a similar survey voluntary.

It is also possible that the House GOP will stick to its guns in committee and the Democrats will let the ACS be killed or compromised.

A recent workshop sponsored by the Committee on National Statistics of the National Academy of Sciences highlighted several hundred uses of the ACS, outside of the US government. Commercial users include Target Stores, Wal-Mart and others, as well as virtually all marketing research firms, political pollsters and so on. (The presentations are available here.)

Many of the Federal uses are mandated – including looking at commuting patterns to help plan transit facilities; understanding the affordability of housing; allocating funds for community block grants; allocating funds to school districts with high levels of poverty or immigrants; providing language assistance for voting; and assessing the need for free or reduced lunch at public schools.

Here's just a sampling of the ways that the ACS can be used to show important demographic change in New York City:

- That earnings for full-time workers showed a decline of 1.6 percent for all workers from $46,721 to $45,496, while for men the decline from $48,976 to $45,619 represents a drop of 6.9 percent. For women, the $43,126 to $42,198 decline is about 2.2 percent.

- That the proportion of the population now married declined from 43.4 percent to 39.0 percent from 2000 to 2010; the proportion of unmarried couple households increased from 5.2 percent to 6.2 percent; while those reporting same-sex unmarried partners showed a slight decline from 0.9 percent to 0.8 percent. (This may be due to the Census allowing same sex households to now report that they are married couples.)

- That, in 2000, 16.5 percent of all households had incomes of at least $150,000, but that by 2010, 17.1 percent of households had such incomes. Meanwhile, the median household income in the city had declined from $50,120 in 2000 to $48,743 in 2010 – a drop of about 2.5 percent. In other words, more New Yorkers had become very affluent, but the typical household had seen an income decline.

But forget about knowing all that if policymakers do away with the ACS. Politicians and researchers will know a whole lot less about who resides in the country, how they are faring and how the country is changing.

This may be the way the GOP House Majority would prefer it – so that politicians and commentators can make their appeals based upon opinion with no chance of contradiction or fact-checking. Of course, they point to cost-saving to tax payers and its supposed impact on privacy.

But the ACS’s demise will deprive the city and the nation of a major source of important information that researchers have relied on for decades.

It would be like asking astronomers to do astronomy without telescopes and physicians and biologists to work without microscopes.

____

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, is the president and co-founder of Social Explorer, a premier on-line demographic web site, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone.