Waiting to Wade

This story was done through a partnership between The Huffington Post's Eyes and Ears citizen journalism program and Gotham Gazette. Gotham Gazette reporter Courtney Gross wrote the piece using stories from New Yorkers gathered through The Huffington Post and Gotham Gazette. Sign up here to join Huffington Post's citizen journalism team covering New York to be part of more of these stories.

These were rough waters.

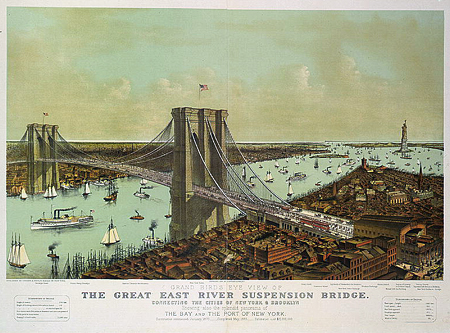

A group of 15 New Yorkers, including this reporter, set out on the East River Friday evening for a taste of the city’s sea salt. Two to a kayak, they trolled our marine superhighway, from the shores of Long Island City to the meandering, if slightly noxious, Newtown Creek, weaving between the city’s water taxis and bobbing in their wakes.

An activity once reserved for long weekends in the Catskills is now embarked upon here in the five boroughs –- life jackets included -– thanks to groups of aqua-friendly volunteers.

“I’m sorry I didn’t start coming out sooner,” said Ted Gruber, the de facto captain of one such group: the Long Island City Community Boathouse, which runs free kayaking programs every weekend. Gruber, a Greenpoint resident, has been paddling throughout the city’s tributaries and rivers for three years.

“Twenty years ago,” he added while pedaling his blue, foot-powered kayak in Newtown Creek, “it was unthinkable.”

Gotham Gazette on the Waterfront

.........................

National Parkland Not on Radar

Our parks columnist explores the national parkland along the New York Harbor -- an area most New Yorkers have never heard of.

.........................

The city has created a new plan for the ball fields on Randall's Island. Critics, though, are calling foul.

.........................

After three tries, a new Mass Transit Tunnel linking New Jersey and New York has broken ground. But advocates question whether this proposal will really ease traffic under the Hudson.

.........................

As planners and developers eye the water's edge, are grassroots and community advocates losing their say?

A lot of New Yorkers and many of you who responded to Gotham Gazette and Huffington Post’s inquiry on waterfront access say they also get their waterfront fix via vessel -- kayaking in Long Island City's Hallets Cove or paddle-boating under the Brooklyn Bridge.

Still, no one is ready to call the East River the new Grand Canal.

The Bloomberg administration’s pursuit of development along the city’s shorelines has brought a renewed focus to the waterfront. From preserving the working waterfront of Sunset Park to the construction of waterside parks in western Queens, points of access to the city’s 578 miles of water’s edge are popping up across the five boroughs. Though it may still be a long way from bringing the waterfront to every New Yorker, advocates say the city is no longer swimming upstream.

To tell us about your own waterfront activities or complaints, check out this map here.

Dipping a Toe In

Megan Browne, who lives in Dumbo at the mouth of the Brooklyn Bridge, takes her 5-year-old twins down to the water almost every day.

Browne, a 43-year-old California native who spent 16 years living abroad in Europe, said living by the waterfront is ideal -- even if New York’s waterfront recreational opportunities pale in comparison to other locations.

"In most European cities, I think they take much better advantage of the waterfront than New York does," said Browne. "It's always been a mystery to us."

But just 10 years ago, according to city officials and advocates, it was far worse. Up until the late 1980s, according to Department of Environmental Protection Deputy Commissioner for Wastewater Treatment Vincent Sapienza, more than 200 million gallons of sewage were discharged into the city's waterways every day -- a major impediment to waterfront recreation and development.

"Obviously, that made things pretty miserable," said Sapienza.

With the addition of new sewage treatment plants, Sapienza said the city is now capturing almost all of the city's wastewater during dry weather (during storms, it’s another story). The progress has allowed the state to designate almost all of the city’s waterways, including the East River, as boat and recreation friendly. The lower New York Bay, which includes the beaches of Staten Island and Coney Island, as well as parts of the Hudson River, from the Bronx to Westchester County, are deemed swimmable by the State Department of Environmental Conservation.

And as the water gets cleaner, more people are likely to jump in -- or at least paddle through, say advocates. President of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance Roland Lewis points out that a decade ago there were only two paddling organizations in the metropolitan area. Now there are 22, one of them being Gruber’s Long Island City-based kayakers.

As the East River lapped against the side of their yellow boats and salty water dripped from the tops of their paddles, the kayakers floated near Roosevelt Island, many wet from the waist down. Leslie McBeth, a Greenpoint resident that was joining for the first time, noted that the city’s newfound waterfront focus is even more evident from the water level. A shoreline once covered only with warehouses facing inland now has piers and large condominiums looking out on the water.

“It was kind of fun to see the city from a different perspective,” said McBeth. “There is so much water in New York… now people are facing it.”

The city, advocates say, is doing its part to encourage that. Last spring, the parks department launched the city’s first water trail –- a pathway made especially for kayaks, canoes and other marine recreation – connecting more than 160 miles of tributaries, creeks, rivers and bays.

Also within the past year, the City Council passed legislation requiring the city draft a waterfront plan every decade (the first is due out in December 2010); the city Planning Department revised its waterfront zoning rules, which it says will encourage more waterfront development and access; and the Bloomberg administration announced the expansion of ferry and water taxi terminals.

Much of this attention may be due to massive luxury residential development along the water. But whatever the impetus, advocates are cheering.

"I give them a very solid thumbs up on turning the corner," said Lewis. But, he added, "there is a long, long way to go."

Finding Your Way to the Edge

Gruber pedaled his way along Newtown Creek –- one of the city’s most polluted waterways –- as a putrid stench wafted overhead and beer cans floated by.

Lucky for this group, the rain had held off for a couple days. It could have been a much smellier story.

Thanks to the city’s combined sewer system, more than a tenth of an inch of rain can send millions of gallons of raw sewage spilling into our waterways. To avoid this, Sapienza said, the city is implementing a wide range of green (and clean) technologies, like porous pavement and green roofs that would trap the city’s stormwater or divert it from the system entirely. Two retention basins are already in use, holding millions of gallons of stormwater until it can gradually be released into the treatment system. Two more, one in Queens the other in Brooklyn, are scheduled to be in use next year.

The Department of Environmental Protection also sends boats out weekly during the warmer, recreation-friendly months to test contaminants in the water. (The boats go out monthly during the winter.) But unlike the city’s beaches, which have the health department sampling and notifying swimmers of water quality conditions , the city’s rivers and tributaries have no public notification system, and the health department does not sample them.

These conditions, says Lewis, prevent New Yorkers from utilizing the city’s waterways to their full potential.

“The limiting factor for a lot of recreation and enjoyment of the waterfront is the CSO [combined sewer overflow] issue,” said Lewis. “In this summer of rain it’s been particularly awful.”

Additionally, Lewis said, the less affluent areas of the five boroughs have a waterfront access drought. As an example, he noted that from Riverdale to the Bronx River, there is no launching point for the public to get onto the water.

Advocates want that to change. The more people use the waterway, said Lewis, the more the city will be required to accommodate them.

Back on the East River, the kayakers’ volunteer leader for the evening, Monica Schroeder, radioed to local marine traffic that the group would be paddling across the marine channel. A tugboat called back: “I’m eating kayakers tonight for dinner.”

Undeterred, the kayakers paddled on, claiming the East River for themselves.

Communities Drowned Out

Old tires. Invasive plants and rampant weeds. Mounds of garbage.

"Basically everything that ended up in the streets tended to end up in our riverway," said Miquela Craytor, executive director of Sustainable South Bronx.

Gotham Gazette on the Waterfront

.........................

Neglected National Parkland

Our parks columnist explores the national parkland along the New York Harbor -- an area most New Yorkers have never heard of.

.........................

The city has created a new plan for the ball fields on Randall's Island. Critics, though, are calling foul.

.........................

After three tries, a new Mass Transit Tunnel linking New Jersey and New York has broken ground. But advocates question whether this proposal will really ease traffic under the Hudson.

.........................

This is how she described the Bronx's Starlight Park -- a decrepit space, long-since abandoned by manufacturing companies who left behind remnants of contamination and debris.

This was, however, before her organization, and other local groups, intervened.

The revival of this park, and many others along the Bronx River waterfront, is thanks largely to Sustainable South Bronx, an environmental justice organization whose mission is sometimes stated as "greening the ghetto." Noting a lack of access to open spaces in their area, the organization's founder Majora Carter fought hard to secure a feasibility study for creating a greenway, which will eventually link restored parks up and down the Bronx River. To date, the project has secured nearly $30 million dollars, according to the group's Web site.

Today, Starlight Park is slated for a major renovation, which will include amenities such as ball fields, playgrounds, a floating dock and legitimate access to the visible – but often unreachable – Bronx River waterfront.

Sustainable South Bronx's activism has been admired nationwide, but community activism along New York City's coastlines is no longer a rarity, according to experts.

With a wave of development sweeping across the city's waterfronts, community-based groups are stepping up and making their voices heard -- initiating, advocating and constantly pushing for access in their neighborhoods. But even as the grassroots movement gains momentum, their priorities can sometimes get caught in a whirlpool of community, developer and city interest.

A Blue Movement

As the president and chief executive officer of the nonprofit Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance, Roland Lewis has seen the organization and power of grassroots groups along the city's shorelines.

"So many of these groups have taken it upon themselves to create access, use and participation in waterfront planning and development all across the city," said Lewis, whose organization is an umbrella of 400 local groups and agencies with ties to the New York and New Jersey coastline. "We sometimes call it a 'blue movement' and part of it is neighboring groups realizing that they have a stake."

Lewis said for most of New York's modern history, the waterfront "was cut off by industry, by roads, by rails. It became a place where no one wanted to be."

With many of these commercial enterprises leaving the coastlines, grassroots groups from Newtown Creek to the Hudson River are clamoring for their "stake" in the 578 miles of New York City waterfront -- 17 percent of the state's total coastline, according to the New York State Department of Coastal Resources.

The benefits to waterfront access are myriad for these communities -- a local economy stimulated by tourism and industry, the replacement of deteriorating brownfields, and the creation of recreation opportunities. The latter, said Lewis, is especially important for the outer boroughs, where the populations are traditionally underserved by open space.

"It's every person's right to be able to get to the water," said Lewis. "We can improve quality of life tremendously... especially for those of us who can't go out to the Hamptons."

Neighborhood and grassroots groups are in a unique position to push their agenda, according to Joan Byron, the director of Sustainability and Environmental Justice at the Pratt Center for Community Development. "There are things you can do from within government and you can only do from within government. But the power to advocate for specific projects is outside of government," said Byron. "Who else is going to do it?"

Organizations like Sustainable South Bronx, Friends of Brook Park and the Newtown Creek Alliance seem to be up to the challenge of trying to reconnect their constituents with one of the city's most valuable resources.

Community Voices Drowned Out

Judi Francis stands on a top level of a parking garage in Brooklyn Heights. She's facing toward the East River and the picturesque Manhattan skyline, but her gaze is downward at the proposed Brooklyn Bridge Park site.

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway roars underneath, as Francis points out the future pedestrian entranceway to the park, now under-construction, which she deems hazardous.

"See, it will be very dangerous to cross there," she says. She shows me where her organization, the Brooklyn Bridge Park Defense Fund, a community-group opposed to current park plans, wanted to tunnel beneath the expressway to create a safer thoroughfare. "But we can't because where that strand of trees is, that will be a 20-story high-rise," says Francis, a resident of the area for 30 years and president of the defense fund.

That very high-rise, along with five others, has become a major point of contention between some area residents and the Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corporation, a subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation, and a partnership of the state and the city. The governor and the mayor appoint their board. Francis charges that the city ignored years of community planning by local groups by erasing all recreational activities from park plans in favor of luxury condos, which the city says will help finance the project.

"One day I woke up like everybody in Brooklyn did, and I opened my New York Times, and a park that had been planned by the community all along the waterfront was suddenly transformed into a housing development with park-like elements," says Francis.

Francis, who says she speaks for 13 community associations and the local chapter of the Sierra Club, contends the condos have replaced a pool, skating rink and event venue, unofficially mapped by the neighborhood during 40 group sessions – making the future of the park a completely "passive" experience.

"You don't build a park with housing because the people who live inside the homes are not going to want people to tramp on their lawns," she said.

Francis isn't the only one disappointed in the plans. The Project for Public Spaces lists the Brooklyn Bridge Park in its design "Hall of Shame," along with other New York locales like Astor Place, Columbus Park Pavilion and the Federal Plaza.

"It's going to be beautiful but it will be limiting in terms of the amount of people and types of uses and flexibility to evolve over time," said Ethan Kent, vice president of Project for Public Spaces.

Kent said that waterfronts "are the face of the city" and should be designed to reflect the identity of an area. He said this was not the case for Brooklyn Bridge Park.

"Unfortunately it will be more of a suburban backyard or a Jamaica Bay, which again is beautiful, but not appropriate for the area," he said.

But Regina Myer, who heads the group charged with developing the site, the Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corporation, said that she has received a tremendous amount of community support. This includes the likes of Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy and Community Boards 2 and 6.

"There were numerous community meetings that took place over the history of this project," said Myer. "It just so happens that the [Brooklyn Bridge Park] Defense Fund objects to our financial model."

Myer said these criticisms represent "one particular perspective" and that the housing complexes developed out of a plan to keep the park financed and maintained – with support from the neighborhood.

"The planning process really did evolve based on different community groups, financial constraints and physical constraints," said Myer. "I think people have recognized that there's no other source for maintenance and economic funds."

A Community Balance

The debate at Brooklyn Bridge Park points out the difficulties of balancing a community's vision with the feasibility of implementing and financing development.

"Waterfront planning projects around the world are undergoing this renaissance and shift in uses," said Kent. "So many of them are leading to conflict and frustration on the part of all parties."

Kent said under the current administration, community group's voices are often silenced.

"Unfortunately it has been something of a hallmark of the earlier years of the Bloomberg administration. A lot of the big projects sort of floundered and were led more by EDC [Economic Development Corporation]."

There are similar sentiments outside of Brooklyn. Back at the Sustainable South Bronx, Craytor said officials and developers occasionally labeled parts of their plans as "details," while they were high priorities to the community.

"Essentially our role was to say, 'No, this is what the community wants, this is what we were pushing for, so we have to find a different way,'" said Craytor. "If it wasn't for our presence in the room, I truly believe that certain elements would've disappeared."

Kent said that despite past planning, he feels positive about future development.

"We're still hopeful that with another term they might make community-based planning and public planning a real legacy of their administration," said Kent.

As Francis watches her dream park transform, however, she remains discouraged.

"It's the way the mayor has sort of transformed the city," Francis lamented. "Unless you're in a position of great wealth or great power, your voice means nothing."

Legal Ruling Puts a Cork on the Bottle Bill

On Monday environmental activists were supposed to be celebrating. The expansion of the state's bottle law was scheduled to go into effect, placing deposits on bottled water, increasing the handling fees stores and redemption centers get per can or bottle and directing 80 percent of unclaimed deposit money from bottling companies to the state. But that didn't happen.

On May 29 federal court judge Thomas Griesa issued an order preventing implementation of the entire law until April 1, 2010. Griesa's ruling came in response to a lawsuit brought by a group of bottled water companies that claimed the law was unconstitutional. The state can appeal the decision.

"Nobody could have predicted the judge's ruling. We were totally shocked," said Laura Haight, chief environmental associate of the New York Public Interest Research Group. The delay could now cost the state $115 million in unclaimed bottle deposits it was supposed to start collecting this year. And stores and redemption centers that were scheduled to see an increase in bottle-handling fees will lose that revenue.

Water bottling companies were upset that the law would have gone into effect just a month after it was signed by Gov. David Paterson, denying them, they said enough time to adequately prepare. "The amendment makes major changes to the bottle bill's framework and for the first time applies to bottled water producers and distributors, who have no experience with the law's provisions," read the complaint filed by the companies. "The short time frame for compliance with the bottle bill is arbitrary and irrational and thus violates plaintiff's substantive due process rights and unduly burdens interstate commerce in violation of the Commerce Clause."

After the bill passed, Haight said she realized the "timetable was very rapid," and expected legislators to address the concerns. They didn't. Haight said state leaders could not "agree on language."

The law also required all returnable bottles sold in the state to have New York State-specific codes. Companies said meeting such a requirement would be expensive, violate the Interstate Commerce Clause in the U.S. Constitution and would be hard to comply with on such short notice. Griesa ruled that this portion of the bill cannot be implemented or enforced at all.

The Fight for the Bigger Bottle Bill

Advocates have fought for years to have the law extended to include mandatory deposits on beverages other than soda and beer. They argue the expansion would increase recycling and reduce litter. Year after year, the Democrat-controlled Assembly would act on the legislation only to have Senate Republicans ignore it. But this year, with Democrats in control of both houses of the legislature, the fight was supposed to get easier. Again, it didn't.

Haight recalls that when she and like-minded advocates discovered that the bottle bill had been included in the budget agreement, they felt they had pulled victory from the jaws of defeat.

The bill, though does not go as far as they would have liked. For one thing, it adds deposits only to bottled water, leaving fruit juices, energy drinks and all the other soft drinks that have proliferated over the past 30 years out entirely.

Beverage companies ran television and radio ads against the expanded bottle bill across the state. They complained the expansion of deposits to drinks other than soda would drive up prices and hurt their business. According to NYPIRG, groups opposing the legislation gave over $2 million to state political parties and politicians in the last election cycle.

In the days leading up to the budget deadline, Haight said, she was just as unsure of what was included in the budget deal between the state's top Democratic leaders as everyone else. "We didn't know what was going on. We were in the dark like everyone else. We didn't know, and the legislators didn't know, either," she said.

Finally, when the three men in the room emerged to share the details, Haight was elated to find that bottle bill was part of the deal. But some legislators were not. According to Haight, "There was a lot of consternation among members of the Senate, as they had not been consulted [about the contents of the budget deal], and some senators went to work to try to unravel the deal."

Lobbyists representing the beverage industry walked the Capitol's halls complaining ferociously to legislators. Environmental groups started a pressure campaign of their own by having constituents call the office of Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith. "Our calls shut down his phone system," said Haight. "To this day don't know how we did it."

Those voicing concerns about the bill and its timetable also became more clamorous, though. Legislative leaders acknowledged the June deadline might be too much to ask of bottlers and indicated they were interested in taking action to give them some breathing room. The action did not materialize, though, and on May 18 the International Bottled Water Association, Nestle Waters North America and Polar Beverages filed a lawsuit challenging the bill's constitutionality.

Kennedy Weighs In

Another shocker for environmental groups occurred when environmental advocate Robert Kennedy came out against the bottle bill and signed an affidavit in support of the beverage companies' lawsuit. In an op-ed for the New York Times titled "A Bottle Bill That Will Rot Your Teeth," Kennedy attacked the bill as being "cooked up by lobbyists for makers of sugared drinks and their allies in the legislature." Kennedy wrote that the bill was absurd for adding deposits on bottled water but not sugared beverages like tea and sports drinks. Kennedy also said the bill would hurt municipal recycling efforts by removing water bottles from their programs.

Environmental advocates were enraged that Kennedy hadn't consulted them before taking his position public. They also noted that he runs a water-bottling company. Kennedy's Keeper Springs sells bottled water and donates its profits to environmental causes. "At first I just thought, 'He's got a water-bottling company,'" said Haight.

Haight said that the legislature did not include flavored beverages because grocery store owners complained that bottles that once contained sugary drinks would be messy and dirty their stores. She said that municipal recycling programs support the bottle bill. "Our coalition includes municipal recyclers who were pushing for this," she said.

No Redemption

It is not just the state that will lose money because implementation of the bill has been delayed. "This is going to impact every place where you return bottles," said Sheila Rivers, chairwoman of the Bottle and Can Redemption Association. "Corner stores, local markets and bodegas are all going to feel it. This will have a huge impact on New York City," she said.

Delaying implementation of the entire bottle law for a year will hurt stores and redemption centers, said Rivers, because the law was scheduled to increase the handling fee they receive, from two cents to three-and-a-half cents per bottle. That increase, Rivers said, is decades overdue. "We have no way to raise prices when costs go up," she said.

On top of that, she noted, redemption centers have been gearing up to deal with the influx of now redeemable water bottles. "Up until Friday we thought this was going to start," said Rivers. "I was in a store on Monday where they had big signs saying, 'We take water bottles starting June 1.' We had to plan for this." Rivers said many redemption centers will probably have to lay off staff they hired in anticipation of the increased workload. "A lot of redemption centers have closed this year, and a lot more will close if we have to try to hang on until next April," she said.

What's Next?

Representatives of water bottling companies say they would like to see all bottled beverages have deposits. "What we think needs to happen right now is for the bill to be fixed to include all bottles, and to make sure unclaimed deposit revenue is funneled back to the municipalities to support community-based recycling," Trish Wexler, spokeswoman for Nestle Waters North America told the Associated Press.

Advocates say it is ludicrous for bottled water companies to say they back expanded recycling when they sued to bring an end to the bottle bill.

For now, activists are waiting to see how Attorney General Andrew Cuomo reacts to the ruling to see how the state might go ahead in addressing concerns about the bill. "We will know what the attorney general's office will do in the coming weeks," said Haight, "but the question is, will the legislature do their part if they have a role to play? Right now it seems they are comfortable to sit back and let the governor take the blame, but we aren't willing to do that."

Toxic Town

New York City may be known for its world renowned-parks and unfiltered drinking water, but the five boroughs are also home to some of the state's most polluted waterways and wastelands.

Some, like Fresh Kills, get attention. Others, like Newtown Creek, struggle for remediation for decades.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, there are 222 Superfund sites -- or abandoned toxic areas in desperate need of remediation -- in New York State. Last month, the federal government proposed to add another one to that list: the Gowanus Canal.

What that debate has shown us so far is remediation may be the easy part of toxic cleanup. Figuring out how to do it, who to blame and how to pay for it is where the real debate begins.

Hold your nose.

Gotham Gazette is unveiling some of the city's most polluted areas and the debates behind their remediation, from Staten Island's North Shore to Brooklyn's industrial waterways.

The Gowanus Canal: Everyone agrees the Brooklyn waterway and the area surrounding it need a cleanup, but residents and others differ on how to do it.

--Joshua Verleun, an attorney with Riverkeeper, writes that the area should be designated a Superfund site.

-- David Von Spreckelsen, a senior vice president of Toll Brothers, which hopes to build along the canal, argues the city has a better plan.

Newtown Creek: The estuary separating Brooklyn and Queens has earned the dubious distinction of being one of the country's most polluted waterways. Residents, advocates and others have long pleaded for a cleanup -- to no avail. Is that finally about to change?

Staten Island's North Shore: This area of approximately 5.2 square miles includes more than 20 sites the government or residents consider contaminated -- many of them close to apartment buildings and houses. In March, the community learned of further dangers.

Staten Island's Toxic Stew

A week after we posted this article, Melissa Checker learned of another perhaps even mrore serious toxic threat on Staten Island. A former warehouse on the North Shore played a significant part in the Manhattan Project, leaving behind levels of uranium contamination nearly 10 times higher than allowable standards in some places. Read her Wonkster post on this development.

This spring, residents of Staten Island's North Shore received news of a triple toxic whammy. First, on March 23, 300 gallons of oil spilled during a ship-to-ship transfer near the St. George ferry terminal. Then, on April 2, the federal Environmental Protection Agency announced that it found lead levels up to 10 times higher than acceptable on the site of a former Sedutto's ice cream factory, just steps away from several homes. That same night, the agency stated that it found elevated levels of lead and arsenic at nearby Veterans Park.

These events mark only the tip of a highly toxic iceberg threatening Staten Island's North Shore. An area of approximately 5.2 square miles, the North Shore contains approximately 21 sites that the Environmental Protection Agency or residents have identified as contaminated. All of them sit within 70 feet of homes and apartment buildings, and residents believe that many violate state environmental regulations. For Beryl Thurman, president of the North Shore Waterfront Conservancy, the industrial zone free-for-all "is like a Girls Gone Wild video."

Yet, the North Shore's toxic woes remain a dirty New York City secret. While Staten Island's most famous waste site, Fresh Kills, once the world's largest landfill, has received abundant attention in recent years, the media has largely ignored Staten Island's other toxic sites. North Shore residents find that they must fight to have their voices heard by state and local officials. Thurman believes it comes down to demographics. The North Shore has the borough's lowest household income, and 48 percent of its households are black or Hispanic. We are "a low-income community of color... If Staten Island is the 'forgotten borough' then on the food chain, we're way down low," Thurman said.

A visit to the North Shore dramatically illustrates the area's uneasy mix of residences and industry. A public pool perched on a hill above the harbor offers a view of garbage-loaded barges. Just west of the pool, an enormous mound of road salt housed at the nearby Atlantic Salt Co. rises high into the sky. Streets feature rows of 19th century shotgun houses side-by-side with notoriously noxious neighbors like a city Department of Sanitation garage, an auto demolition company and a waste transfer station, to name a few.

Residents also fear the specter of past industries. Before it was Sedutto's, the ice cream factory site housed a succession of lead companies. Other former facilities produced gypsum, railway freight cars, boats, ships and linseed oil. The remnants of the chemicals used haunt North Shore residents, who fear that the substances might leach into groundwater and circulate through the air, threatening public health.

They have reason to worry. According to the American Lung Association, Staten Island has the worst smog of any of the five boroughs, and the New York State Department of Health reports that the death rate from lung cancer on Staten Island is 48 percent higher than for the rest of New York City. Thurman herself was diagnosed with asthma in her early 40s. "It wasn't something that was in my family or that I had as a kid," she remembered. According to Thurman, many North Shore residents have developed rare forms of cancer.

Residents hope that remediation of the Sedutto's site will spur a larger effort to give all of the North Shore's toxic areas the attention they deserve. "A lead contaminated site in a residential area would not be tolerated in Brooklyn or Manhattan," said U.S. Rep. Michael McMahon, who represents the area. "We have a number of potentially toxic sites on Staten Island, and it is time to remediate them."

A Toxic Legacy

In stark contrast to its present state, until the late 1800s, Staten Island's North Shore served as a resort area for New York's hoi polloi. However, as the industrial revolution overtook New York, Staten Island's waterways became integral to the city's growing economy, and industries proliferated along the North Shore. By the turn of the 20th century, the area had become Staten Island's most densely populated in terms of industry and people.

It was not until the passing of zoning laws in 1961 that the city undertook a serious effort to limit the degree to which industries and residences could cohabitate. At that time, the city zoned almost half of Staten Island's waterfront, including all of the North Shore, for industrial use. New residences had to have buffers to protect them from certain kinds of industries, but the city permitted all existing industrial properties and residences to remain as they were.

Today, that mix continues. At present, the North Shore houses two private waste transfer stations, an abundance of salvage yards, a Department of Sanitation garage, a Con Edison plant, an Metropolitan Transportation Authority bus depot, a private luxury coach depot and a New York City Department of Environmental Protection sewer treatment plant. Many of these facilities have replaced older and even more noxious industries, but some require the use of oversized trucks, which frequently travel on local streets. That truck traffic contributes to the borough's overall poor air quality.

Hazardous Waters?

Bordering all of these sites is the tidal strait known as the Kill Van Kull. Every year, hundreds of cargo ships and tankers pass through the kull, which is zoned for industrial use. Fuel lines connecting New York and New Jersey run under the water. Some experts estimate that over 300 oil spills occur in the kull every year from the fuel lines and from ship transfers like the one in March. While the Coast Guard was able to clean up most of the March spill, the guard also has promised to step up its enforcement on spills in the Kill Van Kull, as well as illegal dumping.

Under New York law, waterfront industries must comply with the State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System to control discharges into waterways and groundwater. Local environmentalists, such as Jim Scarcella of the Natural Resources Protective Association, worry that because the regulation relies on factories and other sources to report any discharges themselves, facilities along the kull "might not be in compliance."

Portions of the Kill Van Kull are part of the Diamond Alkali Superfund Site, which includes the lower Passaic River and parts of the Newark Bay. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, these bodies of water contain dioxin, PCBs, mercury, DDT, pesticides and heavy metals from various companies that once manufactured pesticides -- including those used to make Agent Orange -- along the Newark Shore.

Local environmentalists fear the situation could get worse. Ongoing dredging by the Army Corps of Engineers and private waterfront industries could unearth those contaminants. In 2005, the Natural Resources Defense Council, NY/NJ Baykeeper and GreenFaith filed a successful lawsuit to stop the Army Corps of Engineers from dredging the kull. In a settlement, the Corps of Engineers agreed to adopt stricter environmental safety measures. Today, however, dredging continues near the Bayonne Bridge, adding noise to North Shore residents' long lists of pollution complaints.

For obvious reasons, the New York State Department of Health distributes fishing advisories throughout the North Shore warning people not to eat locally caught fish. Yet, subsistence fishing continues. For years, the North Shore Waterfront Conservancy has requested that either the Department of Environmental Conservation or the state health department place hazard signs at popular fishing areas, to no avail. "It's about liability and jurisdiction," Thurman suspects.

A Bittersweet Victory

The Sedutto's site represents a prime example of the North Shore's combination of past and present toxic threats. Its history with lead production made it a candidate for the federal Superfund program, which was enacted to clean up toxic sites. However, according to an Environmental Protection Agency spokesperson, the government team sent to inspect the area in the early 1980s had an incorrect address. Unable to find the property, the agency closed the case.

For the next two decades, Sedutto's sold and re-bought the site several times. By the late 1990s, the ice cream plant was no longer operating and the property sat vacant until Perfetto Construction purchased it in 2007. Last April Thurman noticed that Perfetto was using the site to store equipment and debris from a nearby sewer construction project.

"There's all this dust and dirt flying around on everything. So, I'm on the phone with the [New York State Department of Environmental Conservation] and the EPA going, 'what are you doing to protect the residents whose homes are right here?'" she said. Thurman also contacted her then City Council member, McMahon. Eventually, her efforts paid off -- the Department of Environmental Conservation issued a stop work order, and McMahon helped pressure the federal Environmental Protection Agency to re-open its investigation. The agency then discovered the elevated lead levels.

Upon making its April 2 announcement, the Environmental Protection Agency began initial remediation. The agency asked Perfetto to install silt fencing and hay bales around the site's perimeter to prevent migration of the lead, and is "evaluating further steps to be taken," according to a government spokesperson. Meanwhile, McMahon's office has coordinated with the Community Health Center of Richmond and the Beacon Christian Community Health Center to offer free lead testing to area residents.

The lead and arsenic contamination over at Veterans Park is unrelated to the Sedutto's site, according to an Environmental Protection Agency spokesperson. Rather, the agency traces the toxins there to the past use of pesticides by the Parks Department. Officials also maintain that contaminant levels are relatively insignificant -- lead is considered hazardous at 400 parts per million and was found at 516 parts per million one foot below the surface of the park. The hazardous threshold for arsenic is 16 parts per million. At Veterans Park, levels were discovered at 1.4 to 81.5 parts per million.

To protect park users, the agency has covered the ground with woodchips to contain any toxins that might surface. But community members continue to worry about the safety of the park, which remains under the jurisdiction of the city Department of Parks and Recreation. Local families use the park, mainly a grassy field, for picnicking, playing soccer, mini football and baseball games. As Thurman points out, "kids are throwing [the] mulch in each other's faces."

Community groups including North Shore Waterfront Conservancy and the Port Richmond Improvement Association and the local business organization, the Port Richmond Board of Trade, want the city to close the park and complete further remediation.

Since the April meeting, they also have asked the department to post warning signs around the park to no avail. In early May, residents took matters into their own hands and placed two 4-by-8 foot bilingual signs at the park. A few days later, the parks department removed them. "While we understand the community's concern, we cannot allow unauthorized signs on parks property," spokeswoman Meghan Lalor told the Staten Island Advance.

Other community requests for action have met with less dramatic but similarly limited results. For instance, residents asked to relocate two transit authority bus stops near the former Sedutto's site and requested more prominent signs warning of possible hazards there. They also want the Environmental Protection Agency to test nearby Faber Park for contamination.

Local Actions

Since its inception in 2001, the North Shore Waterfront Conservancy has been a persistent voice for environmental justice on the North Shore. For instance, in addition to campaigning to get the former Sedutto's site tested, Thurman, who recently won a 2009 EPA Environmental Quality Award for Individual Citizens, repeatedly calls the state Department of Environmental Protection to complain that the sewer treatment plant "stinks to high heaven" and needs a major upgrade.

The conservancy also sponsors ecotours and regular garbage cleanups of public spaces along the waterfront in order to educate community members about environmental and health issues. In another ongoing project, the groups are gathering a database of potentially contaminated sites that details their present and former uses, the chemicals involved in those uses and the health risks they present. Finally, it advocates for sustainable economic development along the waterfront, which would ensure existing businesses reduce emissions and bring in new, environmentally friendly business.

The last objective is shared by the Staten Island Economic Development Corp., which recently launched an effort to establish a Green Enterprise Trade Zone on Staten Island. The zone idea dovetails with many initiatives in Mayor Michael Bloomberg's PlaNYC 2030.

The North Shore Waterfront Conservancy supports such plans as long as they don't lead to gentrification and the displacement of North Shore residents, according to Thurman. She has reason to be wary -- the development corporation, along with City Councilmember James Oddo's office, held a "Staten Island Health and Environmental 2009" conference in September. They invited representatives from green-tech industries but neglected to reach out to conservancy or other local environmental groups.

For now, though, North Shore residents have focused their attention primarily on the more immediate future of the former Sedutto's site and Veterans Park. The Environmental Protection Agency plans to hold a public meeting in early June to discuss lead threats in the community. Meanwhile, North Shore residents and their advocates continue to pressure the agency, as well as its state and local counterparts, to clean up their acts.

"The general thing is to make the waterfront and the waterfront communities safe," states Thurman, "The way people are treated in those communities right now it's like because... you are in a certain income status, it's your lot in life that you suffer."

Melissa Checker is assistant professor of urban studies at Queens College, City University of New York. She is the author of Polluted Promises: Environmental Racism and the Search for Justice in a Southern Town.

The Brooklyn-Queens Border: As Polluted as Ever

Pewter-colored water lapped up onto the bottom concrete step of an industrially inspired public park on the bank of Newtown Creek.

Amid the new plantings and tall grass, a middle-aged man chased his tawny, rather stout canine around the concrete landscape -- one of the only access areas along the estuarine waterway.

He kept his dog away from the water's edge. And any passersby would likely do the same.

With an oil spill that carries its namesake and a putrid stench known to inspire headaches, Newtown Creek is the product of decades of oil refining, concrete crunching and trash condensing. The long-defunct oil mammoth, Standard Oil, called its shores home, and now so do its contemporaries, Exxon Mobil, Chevron and BP. These giants -- and many others, say advocates -- have helped make Newtown Creek one of the country's most polluted waterways.

For decades, residents and environmental advocates have been pushing for the federal government to clean up the creek, which divides Brooklyn and Queens, but to no avail. Now with the Gowanus Canal under consideration as a federal Superfund site -- a designation made by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency -- and the area's legislators on board, including Rep. Anthony Weiner and Rep. Nydia Velazquez, advocates hope that Newtown Creek will finally get its cleanup.

How It Got So Dirty?

Members of the Newtown Creek Alliance are probably the waterway's biggest champions.

Strolling the creek's Nature Walk, a small public walkway adjacent to the area's wastewater treatment facility, alliance members Michael Heimbinder, Laura Hofmann and Kate Zidar take in the less than picturesque view and the stench wafting from the stagnant channel with surprising pleasure.

Across the way, forming the start of Queens County, they spot the delivery truck parking lot for Fresh Direct. Next door towers of crumpled cars sit on a large barge most likely belonging to waste management company Hugo Neu.

"This neighborhood was pretty much the backyard of the industrial revolution," said Zidar, while, at her feet, a bright pink Clorox label floats by.

That industry, which may have lifted a country, deluged Newtown Creek with oil, chemicals and toxins.

The oil industry's history in the Greenpoint area dates back to the 1800s. During the 1870s, more than 50 oil refineries were located along the banks of the creek, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Between that time and the 1960s, Newtown Creek was a virtual oil refinery shopping mall -- all the heavy hitters were there, from Chevron to Mobil, now Exxon Mobil.

In 1978, during a routine helicopter flyover, the U. S. Coast Guard noticed an oil slick at the mouth of the creek, which meets the East River. That observation has today amounted to an oil spill, which released between 17 million and 30 million gallons into the creek, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. It is unclear, the agency says, whether the spill occurred over time -- a petroleum leak from companies' pipes that produced a pool of oil on the creek's floor -- or if it was one single and totally unnoticed event.

The Environmental Protection Agency also reports it is unclear which companies are wholly responsible -- though many name Exxon, Standard Oil's successor, as the primary offender.

Since that discovery, several companies have had "product recovery operations" around the site. Currently, there are no longer refinery operations on the creek. Exxon and Texaco operate recovery operations, and BP has a recovery and storage facility there.

In 1990, the oil companies and the state Department of Environmental Conservation reached an agreement to remove the petroleum, but critics allege its enforcement has been inadequate. According to the state, that effort has removed 10 million gallons of "petroleum product" from Newtown Creek.

Because of the spill, at least two lawsuits have emerged -- one from a number of Greenpoint residents and environmental advocacy group Riverkeeper and another from Attorney General Andrew Cuomo. The Riverkeeper suit is against Exxon, BP and Chevron, while Cuomo has targeted Exxon only. Both hope to spur a faster and more widespread cleanup of the creek.

The Health Cost

Possible health effects from the oil spill are not completely clear either. In 2007, the state tested some of the homes near the spill area for chemical vapors and determined that it was unlikely such contamination had occurred. Though the vast majority of either side of Newtown Creek is industrial, community advocates and officials fear the toxins may have leaked through the ground to homes less than a half-mile away.

The state has found, however, increased levels of methane, benzene, and other petroleum related compounds in commercial and industrial buildings within the neighborhood.

Some advocates disagree that the centuries worth of industry and production didn’t affect the health of the area's residents.

"My family's medical history reads like an Area 51 report," said Hofmann, who has lived in the neighborhood her entire life.

Hofmann, who is a plaintiff in the Riverkeeper lawsuit, says her whole family has been afflicted by an array of rare ailments and diseases -- from brain cancer to congenital spherocytosis, a type of anemia.

"The cumulative effects of everything are so far beyond anything we know, it's criminal," said Zidar.

The Work to be Done

Next to the former Standard Oil site, members of the alliance climb onto a protruding slab of cement to point out some of Exxon's "product capture" methods.

The water is stagnant, except for the small waves made by a passing boat named "Donna M" (most likely connected to an adjacent company), and the putrid smell forces alliance members to shroud their noses with their shirts.

"Too bad you can't photograph that smell," quipped Hofmann. "You need a scratch and sniff for that."

Everyone laughs.

On the left bank, what looks like a plastic buoy lies across the water, creating a horseshoe-like loop against the creek's edge. That, said alliance members, is part of what the area's oil companies use to keep in their product.

Several feet away, a large pipe bursts out of the bank, spitting out gallons of brownish water. That, they explain, is the outfall, which pours the treated water back into the creek. You can smell the petroleum elements, Heimbinder says.

In 20 years, little has been done to clean up the creek, advocates allege. Unlike the Gowanus, the entire Newtown Creek area is filled with manufacturing or other industries. If no one lives nearby, advocates say, any remediation is "out of site, out of mind."

Hence, the need for the federal government to step in, they say. If Newtown Creek were designated a Superfund site, the Environmental Protection Agency would take over the site's remediation. The agency would seek out responsible parties, and sue them to get funding for the cleanup, which would most likely include dredging the 3.5-mile stretch of channel.

If they lose these cases, they are committed to cleaning up the site with federal dollars. At the behest of the state Department of Environmental Conservation and former Sen. Hillary Clinton and Congress members Velazquez and Weiner, the Environmental Protection Agency started testing the water in January. It finished sampling last month and is currently analyzing the results, a spokesperson said.

The agency releases two sets of Superfund sites per year. Elizabeth Totman, an agency spokesperson, said the agency was not ready to release the results from the creek's testing. The agency would be releasing another set of potential Superfund site designees later this year -- maybe the creek will be one of them.

There are approximately 10 state designated Superfund sites near the Brooklyn banks of the creek, accounting for 36 percent of the state sites in the county.

In response to a request for comment, a Bloomberg administration spokesperson said: "The city hasn't yet taken a position on the potential Superfund designation of Newtown Creek. We’re doing internal analysis now and plan to meet with the EPA next month before expressing any view. The city plans to invest nearly $1.9 billion in Newtown Creek related projects over the next decade."

Not Just Oil

The area's longstanding oil refineries are not the only ones to blame for the creek's noxious state.

The city too could be named a responsible party if the creek were designated a Superfund site. Like the Gowanus, the creek falls victim to the city's combined sewer overflow system, which covers about 65 percent of the city.

Heavy rainfalls overwhelm our sewage treatment system, forcing millions of gallons of raw sewage to pour out into our waterways annually. Newtown Creek is an incredibly stagnant body of water, which leaves our trash and feces floating throughout it.

Standing at a combined sewer outfall at the far end of one of the creek's tributaries, Zidar, who is also a founding member of the Storm Water Infrastructure Matters Coalition, explains that this one particular site deluges the creek with 288 million gallons of water a year -- ranking number 25 out of 400 in the city.

The water doesn't move, she says with the creek's bank serving as her backdrop -- one could spot the remnants of a four-door car half in and half out of the water. Sewage then, she adds, just mixes into the creek.

"The dilution is the solution doesn't apply here," said Zidar.

Because the city's stormwater system is so vast, it would be impossible -- or incredibly expensive -- to reconstruct in its entirety. The city is in the process of implementing a number of policies to divert stormwater or capture it and release it slowly following a rainfall, but advocates question how much of an impact that will have.

A Long Waterway Ahead

There is a reason why Superfund sites are controversial. For one, litigation can take decades to settle. After 25 years, dredging on the Hudson River, a Superfund site, started just this month.

Advocates also wonder how dredging certain areas of the creek, effectively cutting off access to its use, would affect the area's industry, which still uses the waterway. The city's garbage carriers use Newtown Creek to carry our waste to out of state landfills and incinerators.

By and large, advocates and Greenpoint residents and representatives want something done. Bernie Ente, an alliance member and Maspeth resident, was touring the area in his large Suburban last week. He may attribute 20 years passing without the drive for a cleanup to a possible lack of grievance.

"It's just the neighbors to the right don't complain a lot," Ente said. Then he pointed to Calvary Cemetery.

Cleaning Up Pollution at New York's Ports

Our region depends on international shipping to maintain our daily habits and our long-term economic growth. Every day, huge ships bring goods from around the world to the Port of New York and New Jersey. Once these ships dock, cranes and other cargo-handling equipment unload the containers -- putting our clothes, toys, food, and other goods on diesel locomotives and trucks that carry them throughout the region.

These ships bring us what we want and what we need, when and where we want it. But they also bring us pollution that unnecessarily threatens the health of millions of New Yorkers who live near or downwind from our ports. Few ships (if any) are equipped with even the most basic pollution controls, and they typically burn a fuel that contains more than 2,000 times as much sulfur as a New York City Transit bus. Their smokestacks spew tons of particulate matter that trigger asthma attacks, cancers and thousands of premature deaths across the nation every year.

The pollution impacts of our region's port facilities are not limited to the ships in New York Harbor. The armada of cranes, cargo-handling equipment, locomotives, and trucks that ferry containers and their contents to every corner of the city and the region all use diesel-powered engines. Most operate without the most up-to-date pollution-cutting equipment.

Given that the Port of New York and New Jersey is the largest port on the East Coast, the third largest port in the nation and one of the 10 largest ports in the world, cleaning up port-related pollution must be a key part of the path to clean air and long-term sustainability in New York City.

Both the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey are taking this challenge seriously and are taking steps to clean up the delivery of goods into our region.

EPA Takes Action

On March 30, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced a new proposal to reduce ship pollution within 200 miles of U.S. shores. When this new policy is fully implemented, it will have significant public health benefits in port communities and throughout New York, given that ship emissions can travel downwind for hundreds of miles.

Under the agency's proposal, all U.S. and foreign ocean-going vessels in the so-called "Emission Control Area" (within 200 miles of New York Harbor and almost all U.S. shores) will be required to use dramatically cleaner fuel and more effective pollution controls for their engines than they now use. The proposal follows an international agreement reached last year that adopted new emissions standards for the largest container carrying and passenger cruise ships. Under this agreement, nations can petition the International Maritime Organization to create Emission Control Areas off their coasts. In these areas, large ships will have to use fuel that contains 98 percent less sulfur than today's typical bunker fuel and install pollution-cutting equipment to reduce nitrogen oxides by 80 percent, particulate matter by 85 percent, and sulfur oxides by 95 percent, compared to current emissions levels.

The reasons for EPA's concern are obvious. First, of the 100 major U.S. ports where container ships dock, 40 are in metropolitan areas that do not meet federal air quality standards. More than 87 million Americans live near these ports, and many millions more live downwind.

Second, ship emissions are projected to grow dramatically in relation to other pollution sources. According to the EPA, in 2001, oceangoing vessels contributed only about 6 percent of the nitrogen oxides, 10 percent of the particulate matter and roughly 40 percent of the sulfur oxides to the nation's transportation-related air pollution. Without these proposed regulations, ships would have been on a path toward contributing a much larger share: 34 percent of nitrogen oxides, 45 percent of particulate matter and 94 percent of sulfur oxides emissions by 2030. This huge increase would have come from the expected growth in the movement of goods by ship, as well as the dramatic reduction in pollution from cars, trucks, buses and other transportation sources.

A Cleaner Way to Move Cargo on Shore

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey oversees seven major cargo facilities around New York Harbor. Three are located in New York City -- Howland Hook Marine Terminal on Staten Island, the Red Hook Container Terminal in Brooklyn, and the Brooklyn-Port Authority Marine Terminal.

Reducing pollution from the cargo-handling services at the port is critically important, especially given the expected growth in goods moving into and through the region. Despite recent slips in cargo volumes due to the global drop in economic activity, shipping is forecast to more than triple at the Port Authority facilities over the next decade, from roughly 5 million TEUs (20-foot equivalent units, the industry standard) in 2006 to more than 15 million TEUs in 2020. Simply put, there is no way that New York and New Jersey can meet their federal pollution requirements without significantly reducing the port's pollution footprint. That is why clean air strategies play an important role in the sustainability plan that the Port Authority is implementing now.

Getting rid of the oldest trucks operating at the port must be central to any Port Authority clean up strategy. The average truck servicing the port is more than 10 years old, and approximately 15 percent of the trucks at the port were built before 1994 -- too old to be retrofit with any meaningful pollution-cutting filters.

Dramatically cutting truck pollution is feasible and is already happening elsewhere in the city. New York City Transit buses emit 97 percent less particulate soot pollution than they did in the mid-1990s, thanks to the fleet's Clean-Fuel Bus Program, implemented in 2000. Ninety percent of the New York City Transit emission reductions came from retiring the oldest, dirtiest buses in the fleet and replacing them with the cleanest possible engines. The rest of the pollution benefits came from retrofitting the remaining diesel engines with particulate filters.

Adapting the lessons of the New York City Transit cleanup to the port's trucks is critically important, especially to the communities closest to the terminals. Most of these are low-income communities or communities of color, sparking environmental justice considerations.

Here's how to adapt the New York City Transit program to the port's trucks: First, since truck engines that were built prior to 1994 cannot be retrofit, they should be retired as soon as possible. Replacing the oldest, dirtiest engines will provide the greatest emissions benefits, as the transit program has showed. The old engines should be replaced with new engines that are equipped with state-of-the-art particulate filters. These filters are now common in the transit world and are increasingly being used in commercial trucking. Second, engines built after 1994 can -- and should -- be retrofit with particulate filters that will bring them as close to the current federal standards as possible. Together, these steps will make a dramatic difference in the emissions profile of the port's trucks -- and in the air quality along the trucking routes in nearby communities.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard.

Stimulating a Cleaner Environment

and create new rail projects.

Last month, President Barack Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, otherwise known as the "stimulus package." This new law includes $463 billion in new spending, as well as $326 billion in tax cuts that aim to create more than 3.5 million jobs nationwide.

While most reports have focused on the job creation and economic development aspects of the bill, this law can be viewed through an energy, infrastructure and environmental lens. From that perspective, the stimulus package is one of the most significant energy and environmental laws in a long time -- thanks to roughly $80 billion in new investments that will lead to greater energy efficiency; increased use of solar, wind and other alternative energy sources; more funding for urban and suburban transit; additional money for modernizing our highways and bridges; new investments in high-speed rail; cleaner water; and upgraded environmental infrastructure. New York State stands to get a substantial portion of this spending, which will help public and private efforts to create a cleaner and more energy-efficient city and state.

Energy, Infrastructure and the Environment

The New York Times editorial board correctly noted that, if the energy and environmental provisions were separated into a stand-alone bill, it would be "the biggest energy bill in history," thanks to the new spending and tax incentives for energy and infrastructure investments. Overall, the plan will more than triple the amount of federal spending on clean-energy programs.

Major energy portions include:

* A three-year extension of the wind power tax credit, which would have expired at the end of this year, and the tax credit for geothermal and biomass renewable energy projects.

* $4.5 billion in direct spending to modernize the electricity grid with so-called "smart-grid" technologies;

* $6.3 billion in grants to the states for investments in energy efficiency and clean energy, plus $4.5 billion to increase the energy efficiency of federal government buildings;

* $6 billion in loan guarantees for renewable energy systems, biofuel projects and electric-power transmission facilities;

* $2 billion in loans to build advanced batteries and components for advanced vehicles, such as plug-in hybrid-electric cars;

* $5 billion to weatherize the homes of as many as 1 million low-income people;

* $3.4 billion appropriated to the Department of Energy for fossil energy research and development, such as storing carbon dioxide underground at coal power plants;

* A tax credit of between $2,500 and $5,000 for purchase of plug-in hybrid-electric vehicles (capped at 200,000 vehicles);

* $300 million to retrofit old, dirty diesel engines with pollution-cutting filters and other devices.

What Will New York Gain?

New York's environment will be a great beneficiary of this stimulus package. Given the senior role of several of our elected officials in Congress, that's not too surprising. Sen. Charles Schumer is the third-ranking Democrat in the Senate, Harlem Rep. Charles Rangel chairs the powerful House Ways & Means Committee, and Rep. Jerry Nadler is senior member of the House Transportation Committee and a perennial champion for New York's infrastructure investments. To fill out the team of powerful New York congressional members, Rep. Nita Lowey and Rep. Jose Serrano must be included, thanks to their senior seats on the influential House Appropriations Committee. All played key roles in ensuring that New York's environment would benefit from the stimulus plan.

Overall, New York is expected to receive $24.6 billion in funding from the act. But this doesn't begin to tell the full story.

Mass transit tops the list of environmental benefits for New York from the stimulus package. This funding could not come at a better time, given the Albany debate about the best way to save the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's subway, bus and train service and minimize any fare hikes.

The stimulus law will deliver more than $1.2 billion to help meet New York's mass transit needs. For the first time, Washington is sending our state more money for transit than for highway spending. Formula funds set in the bill will deliver at least $967 million for our existing transit system, plus another $254 million for investments to modernize our rail systems. Together, these transit funds exceed the $1.1 billion in federal stimulus funding for our highways. Plus, given our aging infrastructure, high proportion of the nation's rail passengers and over-crowded airports, it is reasonable to hope that New York will receive some of the new federal funding for rail projects ($9.3 billion), discretionary surface transportation projects ($1.5 billion) or airport improvements ($1.3 billion).

Energy efficiency and renewable energy in New York also will get a major boost. Overall, the law will invest $16.8 billion in energy efficiency and renewable energy projects and technologies. New York should reap significant benefits from these funds. For example, the state should receive $126 million from the State Energy Program, which provides grants to states and provides funding to state energy offices for renewable energy and energy efficiency projects. The state also will add another $31 million in energy efficiency and conservation block grants. Together, this creates a pool of $157 million that should help New York's budding alternative energy industries.

New York's low-income residents should also benefit from the energy and environmental provisions of the stimulus package. Indeed, the new law reserves $404 million for weatherization projects to help low-income New Yorkers. These funds will help reduce the carbon footprints of their homes, while also helping low-income New Yorkers withstand future energy price increases.

New York's water infrastructure will receive critical investments, thanks to the stimulus package. The state will receive $435 million from the Clean Water State Revolving Fund and another $85 million from the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund. Along with a recent court decision upholding the federal Environmental Protection Agency's approval of the city's plan to keep its drinking water clean and safe, these funds should benefit all New Yorkers who use our tap water.

Last but certainly not least, the bill contains $300 million to retrofit old, dirty diesel buses, trucks or other diesel engines. To a certain extent, this is a going-away present to New York from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Back in 2005, then-Sen. Clinton partnered with Sens. George Voinovich of Ohio and Thomas Carper of Delaware to pass the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act, a law that authorized up to $200 million per year to clean up dirty diesel engines. Unfortunately, less then $50 million was appropriated last year. In a little-noticed corner of the bill, the diesel retrofit program received $300 million for the next two years. Given that every dollar spent to reduce diesel pollution yields more than $15 in health benefits, this may be one of the greatest bargains of the environmental world.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC switchboard.

Mixing Gas and Water: Drilling in the City's Watershed.

Correction added at end of story (1/16/09)

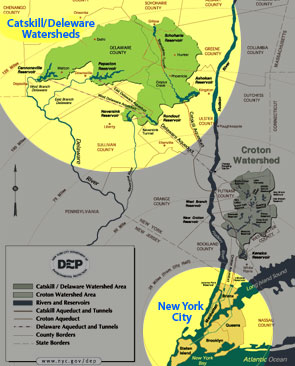

Turn on the tap and New Yorkers get completely unfiltered H2O, flowing from the upstate streams and rivers to faucets from the Bronx to Brooklyn.

Since 1993, the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency has exempted New York City from its filtration requirement, making it only one of a handful of major U. S. cities that does not have to filter its water before letting its citizens gulp. The city's system is the largest unfiltered water delivery system in the country.

Now, some New York City officials worry that anticipated gas drilling will jeopardize the water supply of more than 9 million people in the city and several upstate counties. Gas producers want to drill into the Marcellus Shale formation, part of which lies upstate. They would then inject millions of gallons of water treated with chemicals in order to extract what experts believe could be trillions of cubic feet of natural gas.

Proponents of the drilling say tapping the state's deep reserves of natural gas could bring a bonanza of royalties, jobs and tax revenues to cash-strapped upstate communities and help ease the state's budget crisis. Officials closer to New York City, however, say compromising the quality of the city's drinking water is too high a price to pay. They want the state to ban gas drilling in the watershed.

City Councilmember Jim Gennaro, who chairs the Environmental Protection Committee, has sounded the alarm about the potential cost of filtering the city's water. Gennaro has cautioned fellow committee members -- and anyone else who will listen -- that a filtration system could boast a price tag in the billions.

"What the people of the City of New York, I fear, are looking at is a $20 billion consequence to this 'drill baby drill' policy," Gennaro said.

The Energy Rush

Gas production in the Empire State is nothing new. The first gas well opened in the 19th century, according to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the agency that regulates oil and gas exploration and production.

Geologists have known for decades that potentially huge amounts of gas -- as much as 500 trillion cubic feet, according to one study -- are trapped in the Marcellus Shale formation, a succession of narrow slabs of subsurface rock that stretches through Appalachia from West Virginia to Ohio and New York's Southern Tier. About 30 counties in New York State sit over the formation, which is as much as 7,000 feet below ground in some places.

Because of the depth of the gas and the high density of the rock, traditional drilling and extraction methods have proved to be costly and inefficient. In the last few years, however, technological improvements in horizontal drilling and hydrologic fracturing, or "fracking," have made it more affordable to get the gas out.

As gas prices climbed and construction of the Millennium Pipelinefrom Cornng to Ramapo neared completion, fracking became more economically viable. Early 2008 saw a feeding frenzy of sorts among gas producers as agents for independent producers like Chesapeake Appalachia LLC, Chesapeake Appalachia LLC Fortuna Energy, Inc. and EOG Resources, Inc. rushed to secure drilling leases from upstate landowners and drilling permits from the Department of Environmental Conservation.

Today there are some 13,000 oil and gas wells in the state. According to the Department of Environmental Conservation, a dozen gas wells in Schulyer, Steuben, Chemung, Livingston and Allegany counties produced 19.7 million cubic feet of gas in 2007. In the last year, the state agency approved nearly 50 new well applications, according to the department.

The recent drop in gas prices and the economic crisis may have served to cool the gas rush for the time being. According to an October article in Oil and Gas Journal, 14 different operators had filed 77 permit applications for gas wells in the shale formation by the end of July, and the state approved 48 of the permits. As of October, only nine different operators had drilled 31 wells. No operators have requested or received -- a permit to drill in New York City’s watershed.

A rise in prices could spur renewed demand. Before gas prices backed off of their staggering high this summer, industry officials had projected that there would eventually be between 25,000 and 50,000 drilling pads upstate.

"This will be the environmental issue of the next decade, and it will be the biggest thing to hit the northeast since strip mining took apart West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky," said Al Appleton, a former city commissioner for the Department of Environmental Protection. "The scale of the potential damage is that great."

Getting the Gas

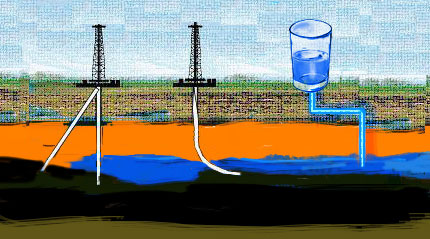

To extract the gas, the operator - typically an independent exploration and production company -- drills a conventional cement-cased vertical well bore into the earth down to the level of the shale.

The bore then turns 45-degrees to run horizontally through the center of the shale slab, which ranges in thickness from 50 to 100 feet. Fresh water, and lots of it, is mixed with chemicals and forced through the well bore and into the shale. The water causes the rock to fracture, allowing the gas to flow back into the bore for capture at the wellhead.

Hydro-fracking has been used for about 30 years, and while it has grown more reliable and affordable, it also requires up to five times more water per well than it did in decades past. A typical "frac job" in 1992 used less than 100,000 gallons of water, according to the state Department of Environmental Conservation; today the same job would require between a million and 5 million gallons.

Environmental Concerns

Hydro-fracking's biggest perceived threat to the environment comes from the chemicals that are used in frac fluids. Gas producers have been historically close-mouthed about what actually goes into the well bore, claiming the mix is a confidential trade secret. Foes of hydro-fracking, though, say they have identified by analysis more than 100 chemical compounds believed to be used in the process across the country. The list includes some highly toxic and carcinogenic compounds like benzene and formaldehyde, and ethylene glycol, as well as hydrochloric acid, N,N-dimethyl formamide, Gluteraldehyde and bleach.

The use of such chemicals creates an unacceptable risk to public health, in the view of Appleton, currently an environmental consultant and a senior fellow at City University of New York's Institute for Urban Systems. Under his leadership in the early 1990s, the city's Department of Environmental Protection launched an ambitious watershed protection program and convinced the federal Environmental Protection Agency to exempt it from filtering its water. In Appleton's opinion, the only reliable way to ensure that our drinking water supply remains safe is to ban gas drilling in the watershed.

"You've got to have a failsafe system. Once these pollutants are in the water they're very hard to get out," he said. "Standard filtration procedures don't get them out, and standard industrial toxic waste treatments, which have never been done on a scale like this before, [are] highly expensive and they're not 100 percent reliable."

There are a number of ways for toxins to find their way into the drinking water collection system, according to Appleton. Some percentage of fracking fluid is never recovered from the shale and instead remains in the ground where it can migrate to aquifers, the natural surface and below surface channels that move the groundwater to streams, rivers and reservoirs. Lax regulations or careless operations in the handling, storage and disposal of recovered frac fluid also pose a contamination risk.

The gas industry downplays the hazards. A report by one industry consultant - also a consultant to the state environmental department - points out that some of the chemicals used in fracking are common chemicals found in everyday household products and are heavily dliuted before being injected into the shale.

Not in New York