The Council Addresses PCBs in Schools

In what advocates say is the most sweeping legislation in the country to tackle PCB-contamination problems, two City Council bills unanimously passed yesterday will inform parents and school employees of contamination in schools and add transparency to the clean-up process.

PCB, or polychlorinated biphenyl, is a chemical that was widely used as a coolant and dielectric before it was banned it in 1979 for its toxicity.

The first bill 563 requires the Department of Education to notify parents and employees of PCB testing results or if the school uses T12 fluorescents, an outdated type of lamp that often leaks PCB. A second bill 566 asks for detailed reports from the DOE on their progress and plan eradicating PCB from schools.

The effort was spearheaded by Councilmen Vincent Ignizio and Stephen Levin. Ignizio said he was inspired to act after he learned of a T12 fluorescent that was leaking PCB onto a carpet where grade-school children sat. "That's where this started," he said.

Nearly 800 city schools — built between the 1950s and late 1970s — are likely contaminated. PCB can hurt cognitive development in children, studies show. It also has been linked to cancer and a variety of other illnesses. Exposure to the chemical is particularly dangerous to young girls, who carry the chemicals in their bodies for years and pass them on to their offspring, as well as pregnant women, whose unborn children can be harmed by the exposure.

"Parents deserve to know what type of environment their children are learning in and school employees should be able to walk into their buildings with knowledge, not fear," Council Speaker Christine Quinn.

The First Signs of PCBs

PCB was first found in New York City schools in 2008, when a New York Daily News investigation found high levels of the chemical in nine schools. In 2009, New York Lawyers for the Public Interest sued the city to have schools officially tested. In the first three schools of the pilot study, all were found with dangerously high levels of the chemical in the T12 lights and caulking.

While the sources of PCB were removed from the three schools, other schools built during the so-called PCB era (the 1950s to 1979) have not been officially tested. The EPA advised an expedited removal of the T12 lights and later recommended an immediate fix. Then Deputy Mayor for Education Dennis Walcott (who is now the city’s school chancellor) asked the EPA to reconsider their recommendations, noting that the “theoretical risk of health impacts” was too low to justify what they estimate to be a $1 billion dollar clean-up. The EPA rejected this, and began testing schools independently, finding 93 percent of tested classrooms to have contamination.

Presently, a DOE spokesman explained in an email, T12 lighting fixtures are inspected for leaks and if found, they are immediately removed and notice is given to the community of the potential PCB risk and the plan for removing the source.

“As part of our comprehensive plan to replace all lighting fixtures in more than 700 school buildings within 10 years, we notify parents and the school communities where we have observed leaks and about the progress in removing the fixtures,” a statement read. “We are committed to updating this material on the DOE website and keeping parents and school communities informed about this issue.”

Health advocates and DOE critics say the ten-year plan isn’t fast enough. "We recognize it can't happen overnight, but you can't put a price tag on the health of our children,” New York Lawyers For the Public Interest's Christina Giorgio said. She and other members of the “Right to Know” Coalition lobbying against PCB contamination are asking the city to take care of the issue within 2 years. NYLPI has worked for years to pressure the DOE to rid schools of PCB; Giorgio is an attorney on their Environmental Justice team. They currently have a suit pending in federal court, where they hope to have a court order to remove the T12 lights more quickly.

The Right to Know

Michelle Chapman's ten-year-old daughter has attended two schools with the T12 fluorescent lights. During the school year, Chapman says her daughter has terrible headaches and fatigue. In the summer, her daughter's symptoms abate. Chapman believes that the exposure to PCBs is why her daughter is sick; she has scheduled a CAT scan and blood tests to confirm.

She hopes that the Council bills will inform and motivate parents to advocate for and expedite the clean-up of contaminated schools. "When they realize [the health risks] they're going to be mad as hell," she said.

“When you have a child as young as Kindergarten they are at the most critical time in their life to determine how healthy and how intelligent they will be.” Giorgio said. “This impacts intelligence, this impacts every system of the body.”

Knowledge is Power

Quinn said that the bills will inform and empower parents and employees so that they are able to advocate for themselves.

"If you find out that your child is being exposed to highly toxic chemicals, you’re going to do something about it, you’re going to demand action," said Giorgio. "We feel that this empowers parents to demand the next step which is to remove these lights – not in ten years – but actually in an expedited time frame of two years,” Giorgio said.

She notes these bills are, "Important first steps and important first victories," towards eradicating PCB, but that there is "more that needs to be done about it. These lights need to be removed and they need to me removed immediately."

Don't Forget Carbon Monoxide

In addition to the PCB bills, the City Council also voted to require landlords to update expired Carbon Monoxide detectors with new ones that emit a beep when they are no longer functional, something the current legislation does not mandate.

Will Community Bans on Hydrofracking Hold Up?

Communities across the state have passed legislation banning the controversial practice of hydraulic fracturing. The movement brings up questions of home rule and is being followed closely by the natural gas industry. Cuomo administration efforts to open the New York State section of the Marcellus Shale to drilling will require hydraulic fracturing, which critics say poses a serious threat to the safety of surface and underground water sources, and causes other environmental problems. Advocates of the process say it will boost upstate economies.

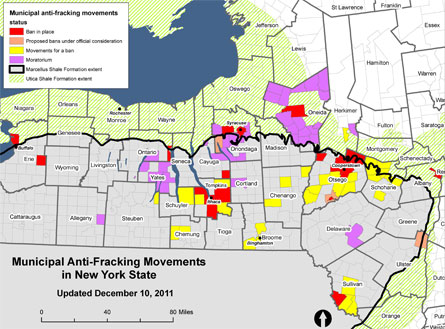

According to a list compiled by Keuka Citizens Against Hydrofracking, fifty-four upstate communities –spanning 14 counties and including the cities of Albany and Buffalo- have permanently banned or placed a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing and related activities within their boundaries. And more bans are on the way. Six upstate counties (Dutchess, Onondaga, Ontario, Sullivan, Tompkins and Ulster) have banned hydraulic fracturing on all county-owned lands. The practice is already restricted from the New York City and Syracuse watersheds.

Local efforts to restrict hydraulic fracturing have resulted in at least two legal challenges to date and these cases are being watched closely by the natural gas industry, upstate communities and environmental advocates. At issue is the concept of "home rule" and whether this extends to a community’s right to determine if gas drilling will take place in its midst.

The Ban in Middlefield

Middlefield Township, which is located in Otsego County and includes part of Cooperstown, enacted a zoning law in June that bans hydraulic fracturing, along with other types of high impact industrial activity.

Town Supervisor David Bliss explained that because nearby Lake Otsego supplies the village’s drinking water and the Susquehanna River sits on its western border, the community felt "substantial exposure" to possible risks related to hydraulic fracturing.

"Middlefield has a history of being forward thinking and a lot of citizens became alarmed. We did a lot of research. That (hydraulic fracturing) was something we didn’t want in our area. The general consensus from surveys and straw polls was that 80% were in favor (of a ban)," said Bliss.

A Middlefield landowner who signed a drilling lease now held by Gastem USA has filed suit against the town. At the first hearing on the case in New York State Supreme Court, Madison County, on December 13th, the judge reserved decision and is allowing further written submissions from parties through mid-January. A decision is not expected until February.

The legal challenge to the Middlefield ban on hydraulic fracturing centers on differing interpretations of state law and the question of whether banning an activity is itself a form of regulation. Levene, Gouldin & Thompson, attorneys representing the Middlefield landowner, argue in a statement released to the press that state law clearly places the authority to regulate oil and gas drilling activity in the hands of the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). They assert that all local bans violate Environmental Conservation Law 23-0303(2), which preempts local municipalities from passing laws regulating drilling activity.

David Clinton, a lawyer for the Town of Middlefield, responds that “state law says we cannot regulate drilling but it does not say anything about whether we can prohibit it. The law is silent.” He cites a 1987 case in which New York State’s highest court ultimately ruled in favor of a municipality that sought to control gravel mining through its zoning ordinance. Says Clinton, “town supervisors across the state are asking about this case.”

Similar legal action has been taken against the town of Dryden in Tompkins County, which amended its zoning ordinance to prohibit hydraulic fracturing and related activities in August. When announcing its lawsuit, Denver, CO-based Anschutz Exploration Corporation also asserted the preeminence of New York State jurisdiction over oil and gas exploration and development. Anschutz maintained that it, “Does not dispute the role of local governments,” but the corporation, “has commenced this litigation to protect its substantial lease holdings in the Town (of Dryden).”

Arguments regarding the legality of Dryden’s actions were heard in Tompkins County Supreme Court in November and now both sides are waiting for Judge Phillip Rumsey’s decision. Dryden’s town clerk, Stephanie Mulinos, points out that the town’s action had "overwhelming support. We held numerous public hearings." Calls to Chesapeake Energy and Cabot Energy were not returned.

Zoning Against Fracking

The DEC does not appear to have taken a definitive position on whether communities have the right to prohibit hydraulic fracturing. Lisa King of the DEC press office said in a written statement to the Gotham Gazette that, "A town can pass an ordinance but we do not know if it will be upheld in court given the current provision in the Environmental Conservation Law that states that local regulation of the oil, gas and solution mining industry is preempted except for local jurisdiction over roads or the rights of local governments under the real property tax law. The scope of this preemption must be left to the courts."

Despite the potential for a legal challenge, advocates report that efforts to pass local restrictions on hydraulic fracturing exist in at least 34 other upstate communities. One of these is the city of Binghamton, whose City Council will vote on a two-year hydraulic fracturing moratorium on December 21st. A restriction on drilling in Binghamton would be noteworthy because of its location in the Southern tier of New York, the section of the state considered most promising geologically for natural gas production. Most of the existing bans on hydraulic fracturing are found north of the Southern Tier.

Local communities wishing to control drilling activity have found allies in both houses of the New York State Legislature. Democratic Assembly Member Barbara Lifton of Tompkins County and Republican State Senator James Seward of Otsego County have proposed similar legislation authorizing local governments to address natural gas drilling in their zoning or planning ordinances. An earlier version of Lifton’s legislation, clarifying that home rule gives local communities the right to regulate drilling, has already passed in the Assembly but did not pass the Senate. Senator Seward introduced similar legislation just before the close of the 2011 legislative session and his bill will be re-introduced in 2012. According to Assembly Member Lifton, “We have a very strong tradition of home rule in New York State. It’s in our state constitution that locals have the power to regulate. If it (home rule) applies to gravel mining, it also applies to gas.”

Advocates Look for Other Ways

Along with bans enacted by local communities, environmental groups are preparing to take the State DEC to court because they say that the agency has not complied with provisions of its own environmental review process. The DEC released a revised draft of its Supplemental Generic Environmental Impact Statement (dSGEIS) for hydraulic fracturing this September. The public comment period on the revised draft has been extended until January 11th, 2012 because of the high volume of comments that have been submitted.

Katherine Hudson, Watershed Program Director for Riverkeeper, told Gotham Gazette that the DEC committed in 2009 to a thorough study of both the positive and negative socio-economic impacts of hydraulic fracturing for upstate communities. She stated that if the final version of the dSGEIS does not include the level of analysis required by the 2009 scope, Riverkeeper and other organizations will initiate proceedings in New York State Supreme Court to declare the DEC review process legally flawed and deficient, which could require the State to re-do the review process and impact statement.

Deborah Goldberg, managing attorney for Earth Justice’s northeast office, adds that “there is a virtual certainty of litigation” against the State. Goldberg cited other flaws in the State’s impact review process, including the drafting of drilling regulations before the impact statement has first been finalized. She also raised measures taken by other states –such as analysis of air emissions data in drilling areas- which could inform New York’s approach to drilling. "We want New York State regulations to be state of the art -- the gold standard."

But first, the State and its local communities must resolve who has the final say about where drilling can even take place. New York’s tradition of home rule faces a test with broad implications for residents statewide.

City Rules Could Transplant Gardens

While New York City adopts increasingly progressive measures to promote sustainability, at least one "green" group remains unsatisfied. Some community gardeners, charging that the most recent city regulations leave them largely unprotected, fear their plots of land could be snatched away at any time.

The rules, though framed as a gift to gardeners when enacted in September 2010, do not permanently protect existing gardens as an earlier agreement did. While 282 gardens remain protected, the Department of Parks and Recreation and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development reserved the right to swap the protected gardens for other similar space. That and other caveats outweigh any theoretical increase in protection, advocates say.

"We all hoped that the rules would say active gardens would be preserved, but they didn't," said Hannah Riseley-White, a community organizer for the nonprofit organization Green Guerillas. "When you read the text, it really says the gardens are protected, unless we want to sell them."

Close to 200 gardens out of around 450 -- a number that doesn’t include Department of Education gardens -- are vulnerable to sale and development under these rules, advocates say. But, more importantly, they believe, all city gardens ultimately remain in jeopardy because none of the legislation they sought made it into the 2010 agreement. Without laws to protect gardens, those who work on them say, nothing is guaranteed.

"Rules and regulations are only as good at the current administration," said Karen Washington, the president of the New York City Community Garden Coalition. "That's not permanency."

Governing Gardens

The rules governing community gardens have gone through a number of changes in the past 20 years. As community gardens became increasingly popular in the 1980s and '90s, gardeners wanted to preserve their limited growing space, while real-estate developers craved room to expand. In 1999, the Giuliani administration, which had methodically sold garden lots for housing development, put 119 gardens on the auction block in a single day. Nonprofit groups saved some of the gardens by purchasing them, and then-state Attorney General Eliot Spitzer filed suit to halt Giuliani's wholesale development of the green space. In 2002, freshly elected Mayor Michael Bloomberg settled that lawsuit, reaching an agreement with the attorney general to permanently exempt a sizeable batch of gardens from a bricks and concrete fate.

That agreement promised firm, permanent protection to 198 community gardens and preserved about 100 more Department of Education gardens, while designating around 150 gardens for sale and development. The accord provided an armistice to years of battle over the dwindling open space in New York City.

Or perhaps it was only a ceasefire. The rules expired in 2010, prompting the Bloomberg administration to issue new ones. Under these rules, gardens "permanently" protected in 2002 are now subject to "swaps." As a result, around 250 gardens will remain protected for the foreseeable future, but they won’t necessarily occupy the same space they do now. It is the garden that is protected -- not the land it lies on -- so the garden can technically be relocated with the land it once occupied subject to development.

Christopher Amato, who was lead attorney for the state at the time of the 2002 agreement, cautioned at a 2010 public hearing that this approach threatened to create "nomad gardens." Such gardens, he said, could be "forced to move every few years in response to development proposals until, presumably, the gardeners threw up their hands and abandon future gardening efforts."

Amato added that the 2010 rules were “inconsistent with both the letter and the spirit" of the 2002 agreement, as they would "eliminate or substantially weaken several key provisions."

Aresh Javadi, board member for the Community Garden Coalition, agreed. "Working through the attorney general's [2002] agreement," Javadi said, "it was clear that the 198 community gardens named as parks were to be protected permanently."

That is certainly the impression Bloomberg conveyed when he announced the 2002 deal. "We are providing permanent protection to hundreds of community gardens throughout New York City,” he said then, "and establishing a fair process for reviewing future proposals to develop other garden properties."

Now, though, the city has taken a different approach. When the Community Garden Coalition reminded administration officials of the 2002 comments, Javadi said, “They kinda said, in general that’s true but as long as the overall number is the same we can pick and choose what we'll bulldoze."

Javadi added, "With those clauses, they can do whatever they want to anybody."

The administration, for its part, has said that active gardens have nothing to worry about.

"Parks gardens are not available for development unless the garden is in default or inactive," said a representative for the parks department, who added that no gardens have yet been defaulted.

However the representative added, "Parks community gardens and [those under the Department of Housing Preservation and Development] have slightly different rules. ... Parks licenses gardens for four years while HPD's is only for one year." According to the housing department, it has jurisdiction over 26 gardens.

Trading Places

The fate of one Brooklyn garden highlights the dilemma inherent in the swaps.

Hart to Hart garden sits four blocks north of Tompkins Park in Bedford-Stuyvesant, a quarter block of grass enclosed by a linked fence. It grows mostly herbs and vegetables, and offers composting to its members. Its membership tripled in 2009, according to Green Thumb, the city program that manages, but doesn’t own, community gardens in the five boroughs.

When the city realized that Hart to Hart, though thriving, was one of the 150 gardens assigned to the housing department under the 2002 deal and thus vulnerable to future development, the agency decided to swap it with the Warwick Block Association community garden, a parks department lot that was less active. Now, Warwick is no longer a protected garden, even though it was granted permanent status in 2002.

Margot Dorn, the head contact for Hart to Hart, was largely unaware of the swap's logistics. "There were complicated dealings" associated with it, she said, but the city largely handled it without involvement from the gardeners.

The swap means that Hart to Hart will continue to function as it has, and in the same location, but is now classified as a protected parks department garden. Meanwhile, the Warwick garden became a housing department garden. Since those are not protected, the lot could be developed as housing in the future, leaving the Warwick group without a space of its own and, in essence, possibly shutting down one city garden.

Although the 2010 agreement said only gardens that were no longer active would lose their parks department protection, the city soon extended that to gardens that were merely "less active."

"Warwick was an active garden, but the city felt justified doing that swap in order to preserve Hart to Hart," said Riseley-White.

Additional Protection

Despite such struggles, community garden advocates say the 2010 rules do offer some policy improvements.

Now, at least, gardens losing their status have some warning. Notification goes to two people affiliated with the garden instead of one, helping to prevent communication snafus. And upon receiving such notification, groups now have 30 days to turn the situation around by proving their lot's viability. If they clean up messy weeds or increase community participation, the gardeners can save their lots.

Also, the new agreement affords some protections to any new gardens that may come in to existence, whereas the old one only applied to those established before the 2002 agreement.

And, says Javadi, the recent disputes have only energized gardening activists. His group is gathering documents that it hopes will prove which gardens are protected, in order to make that information widely available to the public.

"We really need to know exactly which gardens are the permanently protected ones," Javadi said. "Then, if any are impinged upon, we will very, very aggressively go after any agency that wants to hurt the community and its gardens."

As City Leases Industrial Sites for Schools, Concern About Safety Builds

The heat is on the Department of Education this summer, after environmental tests at a Bronx elementary school revealed yet another case of contamination.

Just five weeks before the start of the new school year, parents at PS 51X, known as the Bronx New School, received surprising news from the Department of Education. In a letter dated Aug. 5, the department announced that it was closing the current building and moving the school to an undisclosed location. Air quality tests had revealed unsafe levels of trichloroethylene (TCE), an industrial solvent. Although the New York state Department of Health stated that there were "no immediate medical concerns for students and staff," the city determined that adequate remediation could not be completed before the school starts in September.

The city leased the Bedford Park property, a former industrial site, in 1991. For two decades, it has operated as a school; but some parents now say that their children have complained of chronic headaches.

PS51X now joins a growing list of schools across the city that may be toxic. Under current law, the city can lease property and open a school on it without notifying community members, or making public any concerns about environmental hazards in the area. With approximately 96 schools throughout the city on leased properties and more in the pipeline, this could affect tens of thousands of children.

The Hazard in the Bronx

Many parents had no idea Bronx New School sat on a former industrial site. According to the city, the building's lease came up for renewal, triggering the environmental tests. Initial sampling occurred in January and found levels of TCE 10 times higher than the health department's standard for safety. A second round of tests, conducted in March, sampled the soil vapor beneath the school's basement floorboards, finding levels of TCE more than 10,000 times than the limit set by the state.

Now, parents, teachers and environmental advocates are demanding to know why the city waited so long to move the school. They will have the chance to ask such questions at a meeting with schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott scheduled for this Thursday, Aug. 18 at 6 p.m. at the Bronx High School of Science auditorium (75 W. 205th St.).

Education department spokesperson Marge Feinberg explained that the DOE waited for final scientific determination on the tests, which came in mid-July, before making a decision about relocating the school. She also emphasized that the highest levels of TCE were found under the building, in an area not used by teachers or students. But environmental advocacy groups worry that TCE vapors could have been migrating upward into classrooms from underneath the floor for some time.

Feinberg maintains that the city is "very conservative" when it comes to making sure schools are safe for occupancy. "Since the first term of the Bloomberg administration, we have renewed more than 65 school leases, and 51X is the first one where environmental conditions have caused us to abandon the lease renewal," she said. The city will conduct environmental audits on another 31 leased school sites over the next eight weeks, though it has not made a list of those schools available.

According to Michael Mulgrew, president of the United Federation of Teachers, before 2003 the city did not necessarily conduct environmental investigations when it leased properties. It is unclear, then, whether the Bronx school had ever been tested before now.

Transforming Brownfields into School Fields

Placing schools on former industrial properties is not a new practice. Over the past few decades, the city's own school buildings have reached and even exceeded capacity while other available space has become increasingly scarce. Former industrial properties are often the only sites large enough to accommodate new school buildings. "Our leasing program has been extremely successful in identifying sites for new school build-outs in districts where finding new school construction sites has been extraordinarily difficult," said Feinberg. Over the years, the education department's construction arm, the School Construction Authority has spent billions of dollars to remediate toxins.

However, a growing number of parents and advocates question whether, in its haste to make good on promises to reduce overcrowding, the School Construction Authority takes too many shortcuts. In particular, they charge that the city deliberately keeps the public in the dark when it comes to remediation plans. Lenny Siegel of the Center for Public Environmental Oversight, an independent consulting firm that has been called in to evaluate several New York City school sites, told the Daily News, "Someone should be on the ball making sure the air, water and soil are safe."

A Tales of Two Schools

At some schools, they are.

Last September, the city opened the Mott Haven Educational Campus, the Bloomberg administration's largest school construction project to date. A four-building site, the campus spans six acres and seats 2,000 students. It sits on a site purchased by the city that once contained a rail yard, a laundry and a plant that made gas from coal.

The project sparked controversy from the start. Both the Public Authorities Law and the State Environmental Quality Review Act require the city to solicit public comment and approval from the City Council on its plans for constructing on publicly owned properties and managing their environmental issues. In Mott Haven, community and City Council members argued that the city's plan for mitigating toxins was inadequate. Council members refused to approve it until the city provided for more intensive environmental study and remediation.

Eventually, the Department of Education spent $30 million to clean up the Mott Haven site. But community members continued to oppose the project, contending that the city kept them in the dark about long-term plans for maintaining and monitoring contamination there.

In 2007, the New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, acting on behalf of the Bronx Committee for Toxic Free Schools, a coalition of parents, neighborhood residents and community organizations, successfully sued the School Construction Authority and the Department of Education for violating the Public Authorities Law and the State Environmental Quality Review Act by not disclosing a Site Management Plan. This July, a state appeals court unanimously uphelda lower court ruling that, indeed, the city violated state environmental law in building the Mott Haven campus.

No such ruling is possible for the Bronx New School, however. Unlike Mott Haven, the city leased, rather than purchased that school property. Although the School Construction Authority must test and clean all sites before opening schools on them, when it comes to public information and oversight, leased and owned schools are not at all equal.

Leased sites fall through a gap in the Public Authorities Law, known as the "leasing loophole." The courts have interpreted the law as applying only to sites that the city owns and not those that it leases. In a nutshell, that means that leased schools do not require an environmental review under the State Environmental Quality Review Act , nor does the city need to make public its plans for building, remediating or monitoring those schools. As a result, "Parents, school staff and community members often have no idea that a leased school site sits on top of contaminated property and, more importantly, what the SCA has done to eliminate any health risks," said Dawn Philip, a staff attorney with New York Lawyers for the Public Interest who handled the Mott Haven case.

Falling into the Leasing Loophole

The Department of Education plans to create 30,000 new school seats over the next five years. By 2014, leasing will meet one third of its total capacity needs. That means one third of all city's schools will be subject to the leasing loophole.

The loophole first attracted attention in the 1990s when the city leased a former dry cleaning plant to house PS 141 in Harlem. The city spent millions of dollars converting the property into a school, but it opened it before environmental testing was completed. Within a week, tests revealed levels of perchlorethylene, or PCE, up to double the state's acceptable levels. The school shut down and has never reopened.

In another example, Mary McKinney walked out of her house in the Soundview section of the Bronx one day in 2004 to find construction crews. They were working on the former site of a military contractor that had generated tons of toxic waste including lead and industrial solvents. To her surprise, McKinney, who was a member of her community board at the time, learned that the land was slated to become a 1,000-student school, the Soundview Educational Campus. The education department had leased the property and the city's deputy mayor for education -- and now chancellor -- Dennis Walcott, had quietly signed a zoning waiver so the city could locate the building in an area zoned industrial -- all without any public notification.

Community members along with Lawyers for the Public Interest and then New York State Sen. Eric Schneiderman convinced the School Construction Authority to commission an independent environmental review of the site. According to the New York Times, testing revealed levels of mercury, chromium, lead, arsenic and other toxic substances much higher than state standards allow. Yet, the state health department determined that the levels did not pose immediate health risks. The campus remains open.

More recently, in 2009, Inwood parent Susan Ryan discovered that her son was zoned for P.S. 18 and P.S. 278. When she went to look at the schools, she found that both are adjacent to a carwash and within a block of the Kingsbridge bus depot, a Department of Sanitation garage and at least six auto-body repair shops. Ryan contacted Dawn Philip at Lawyers for the Public Interest and asked for help in filing a Freedom of Information Law request. The request revealed that "an oil spill at the school sites was reported to the [state] Department of Environmental Conservation in September 1999, yet due to a backlog, it was just assigned to an inspector [in 2009],Ryan wrote in a 2009 op-ed for the Daily News.

The construction authority agreed to hire Siegel's Center for Public Environmental Oversight to conduct an independent review of the school. The report found that current air quality levels were safe, but that the site carried significant risk of exposure to contaminants. It recommended careful, ongoing monitoring to ensure that neither vapors from the oil spill, nor other nearby contaminants migrate into classroom areas. As of now, it remains unclear whether and to what extent the School Construction Authority has taken up those suggestions, as the agency is not required to publicize such information.

Looking at the Long-term

While Ryan and other parents are relieved to hear that their children face no immediate dangers, they still have concerns. Because the leasing loophole allows the city to circumvent certain public notification processes, parents and advocates worry that there is no way to ensure that their children and others throughout the city will remain safe from contamination over the long-term. In some cases, even low-level exposures can cause harm, if they occur over long periods of time. "Why do we have to wait until our children are exhibiting symptoms of illness before we take action?" asked Ryan.

"We have teachers who are in these schools for years and years, we have students who are in these buildings for much of their childhood. So to answer parents' concerns by saying 'there's no immediate risk' misses the point," Philip agreed.

Take, for instance, PCBs, another toxic school issue that made major headlines this year. The federal Environmental Protection Agency maintains that the high levels of PCBs in lighting ballasts and caulking at multiple city schools do not constitute an immediate danger to students or school staff. Yet, the agency also pointed out that prolonged exposure to PCBs can cause brain damage or cancer in students and their teachers.

Similarly, the EPA associates long-term exposure to high levels of TCEs, such as those found in certain places at the Bronx New School, with disorders of the central nervous system and several types of cancers in humans, especially of the kidney, liver, cervix and lymphatic system.

Ensuring that toxins stay contained is, then, crucial, especially as contamination remains below the ground at most of these sites.

"The trick is to keep the protections in place over the life of the contamination and the life of the school," said Siegel. "Thus continuing vigilance is required to prevent exposures." That kind of vigilance only happens if the public knows what is going on.

Turning up the Heat

Philip and her colleagues at New York Lawyers for the Pubic Interest have been working with state Assemblymember Catherine Nolan and others to pass a bill that would amend state law to ensure that schools on leased property undergo the same community notification and City Council review processes as schools on city-owned land. The bill has come before the State Assembly several times and passed, but has gotten caught up in the State Senate. Philip remains hopeful that public pressure is growing to demand reform.

In the meantime, advocacy groups are working to identify and track the 31 leased schools sites currently slated for environmental testing. They also hope for a large turnout at the Aug. 18 meeting about PS 51X.

More generally, at any school that faces potential contamination, "Parents can request indoor air or an explanation for why it is not necessary to do any sampling," Siegel said. They can also pressure the city to hire an independent firm to analyze sampling results and to make all information public.

"Similar to the PCBs issue, this is fundamentally a right to know issue," Philip said, "We want new schools as much as anyone else but we also want safe and healthy schools. Children's health should not be compromised for the sake of expediency."

Melissa Checker is associate professor of urban studies at Queens College, CUNY and of anthropology and environmental psychology at the CUNY Graduate Center.

Food Revolution Prompts Entrepreneurs to Make It in New York

Despite once being a legendary city for food manufacturing -- Clarence Birdseye invented flash freezing here, for example -- New York for decades saw food processing slowly decline. Storied companies, like Stella d'Oro, Old London, Bazzini Nuts and Schaefer Beer left the city. City officials used almost every tool at their disposal to stem the tide -- nearly always unsuccessfully.

Yet even as brand-name, commercial companies were moving out to the drumbeat of apocalyptic headlines, a food revolution had started and today continues to transform the rules and the dynamics of New York's $5 billion food processing industry.

All over New York (and in other cities as well), well-educated, energetic young entrepreneurs are re-creating food manufacturing in their own image and according to their own ideology -- hip, local, creative, fun, unique, retro, sustainable. Propelled by many diverse forces -- the local food movement, climate change, immigration, the recession, waterfront development -- the products of New York's food revolution are now on display at all sorts of new venues, both profit-making and nonprofit. Breads, biscuits, syrups, beer, noodles, sauces, coffees, chocolates, cookies, ice cream, etc., are sold -- many after having been prepared at one of the two city-financed food incubators.

While food companies have closed or left, enough have opened to keep the numbers fairly steady. Figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that in 1990 the city had 938 food establishments. That decreased to a low of 872 in 2006, before climbing to 1,009 last year.

Small May Be Beautiful, But is it Profitable?

One might argue, however, that the artisanal products are not quite real in the same way that Old London Melba Toast or Stella d’Oro cookies are. Will they evolve into truly profitable businesses?

Seth Pinsky, president of the Economic Development Corp., notes that the city doesn’t need all the new producers to succeed, though it would like as many as possible to make it. He said that many food producers traditionally started small -- thus the incubators, which, says, Pinsky, are meant to nurture, but not provide a permanent home. When the companies reach a certain scale they need professional space and will move on.

This kind of city program directed at tiny (even one-person) firms is a far cry from the economic development strategy of, say, the 1970s, when the city focused on large enterprises, particularly Fortune 500 companies. Even then it was understood that 90 percent of city businesses had fewer than 50 employees -- but dealing with small businesses was deemed just too difficult, and the pay-offs too distant.

Today's zeitgeist is entirely different, with an admiration for the unique, particular and local -- especially in food. But can that zeitgeist be exploited to profitability? Can the many adorable vendors with their adorable products at, for example, the Smorgasburg or Dekalb Market in Brooklyn or the New Amsterdam Market in Manhattan, evolve into stable businesses?

Karen Karp, a prominent food consultant whose company motto is "good food is good business," points out that quite a few niche brands have gone mainstream. Terra Chips, for example, which was founded in a tiny private kitchen in Brooklyn 20 years ago to make delicious but nutritious root vegetable chips, was bought by the Hain Food Group (now the Hain Celestial Group) in 1998. In 2002, Hain moved Terra's production plant and its 90 jobs from Brooklyn to a 75,000-square-foot building in Moonachie, N.J.

Tom Cat Bakery, which opened in Long Island City in 1987 with a $120,000 investment, initially produced 300 loaves of French bread and sourdough and 400 rolls a day. By the time it was acquired by food-oriented venture capitalists in 2008, it had 275 employees, 900 customers, and $32 million in annual revenues.

But will Tom Cat have to follow Terra Chips -- and other successful companies -- across the water to New Jersey, or even out of the region altogether? "They really want to stay in Queens," says Karp, "but they’re bursting at the seams. Real estate is a problem."

To help entrepreneurs cope with New York's high cost of real estate and chronic space shortage, the city has responded with two very different options. The first is the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which has some 3.6 million square feet of space in 40 buildings distributed over 300 acres. The yard charges market rents but its city-owned status exempts tenants from paying property tax, which can be a significant savings.

Second, the Economic Development Corporation set up the entrepreneurial incubators, creating over 135,000 square feet of affordable work room for food. The incubators in turn have generated over $20 million in venture capital investment.

Take the Entrepreneur Space, which is a partnership between the Queens Economic Development Corp., headed by Seth Bornstein, and Mi Kitchen es su Kitchen, headed by Kathrine Gregory. Bornstein’s office had $500,000 in capital resulting from a shopping mall development that had to be reinvested in development projects in Queens. Using part of these funds plus an Economic Development Corp. grant of $175,000, Bornstein upgraded the former union training hall at 37th Street and Northern Boulevard into sleek, efficient kitchens, classrooms, and conference rooms. The 5,500-square-foot, professionally equipped commercial kitchen is open 24/7 and currently incubating over 150 clients, though the number fluctuates. The cheapest shift is early morning -- 1 a.m. to 7 a.m.—for $154; the most expensive is daytime -- 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. -- at $231.

Danny Lyu, who makes immensely popular Mexican sandwiches called Cemitasthat he sells at the Smorgasburg, says Entrepreneur Space is expensive but worth it. "The space is divided and segregated well," he notes, "but the atmosphere is communal. You help each other, and make sure everything is clean when you leave. If you don’t have your own bricks and mortar, you have to go into shared space, and you have to help each other to make it work."

The incubators provide kitchens that already meet health regulations and negotiates with the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to encourage a reassessment of regulations that can be destructive for fledgling enterprises. An ongoing problem for start-ups is that the health department requires caterers to have permanent premises.

"We're one of the licensed spaces," says Gregory. "All manufacturers operating here can get the appropriate licensing that allows them to sell food legally.”

Food Economics

One of the first elected officials to recognize the economic implications of food was Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer who in February 2009 released Food in the Public Interest. Noting that New Yorkers spend an impressive $30 billion annually on food, Stringer argued that the city should officially encourage and support local food systems -- New York State farms, farmers markets, urban gardens, processors.

The city, said Stringer, needed to analyze and designate its foodshed, the territory between where food is produced and where it’s consumed. Much like a watershed, which outlines the flow of water serving an area, a foodshed outlines the flow of food from land to table. Stringer urged giving growers of healthy food within roughly a 200-mile distance special access to the city's food markets and outlets. He also pushed for City Hall to allocate 20 percent of the $435 million school food budget to local producers and processors.

Joan Dye Gussow, the well-known nutritionist and gardener who is often called the matriarch of the sustainable food movement, recently commented, "If 20 years ago any elected official had talked to me about New York's foodshed I would have thought they were smoking dope. Nobody was discussing it. Nobody, at least in government, understood the implications of the city being hideously dependent on petroleum to get its food."

Part of the problem is that even as the old-style food industry was breaking down and being re-created in a different model, the city's food distribution system -- centered on the Hunts Point Market in the Bronx – also was showing its age. Handling some 70 percent (and $2 billion worth) of the fruits and vegetables eaten by New Yorkers, Hunts Point's physical plant has become dangerously inadequate. Dozens of diesel-run tractor-trailers are used to store produce, which is not only environmentally unsound but in violation of federal cold chain standards, which increasingly require an unbroken cold chain to maintain food within a stipulated temperature range.

Meanwhile, even as the city tries to figure out how to upgrade Hunts Point, the new upscale chains that have moved into New York -- Whole Foods and Trader Joe's, to name two -- have bypassed Hunts Point altogether, shipping in their own superior and often local produce. Only 2 percent of Hunts Point produce is local, according to City Council Speaker Christine Quinn.

Just five years ago, city residents wanting New Jersey peaches or New York apples bought them mainly at the Greenmarkets. Now they're available in good grocery stores -- and from suppliers like Fresh Direct. Even Wal-Mart, the nation's largest food seller that is anathema to some community activists, has a corporate policy of reaching out to small and medium-sized farmers, says Nevin Cohen, assistant professor of environmental studies at the New School. These suppliers have structured a very efficient distribution system that ignores Hunt’s Point, except when they run low on supplies.

Even as many markets offer ever more local produce to New Yorkers, Stringer makes the leap to the next problem: food processing. He urges City Hall to pursue "an industrial retention policy to promote the food processing industry by creating financial incentives for small-scale processing in the foodshed, which may include streamlining fees and permitting processes, incorporating food processing in wholesale market development, and training local workers."

Take fees. Nearly all local produce is shipped in by truck. But every truck coming over Port Authority bridges must pay tolls kept deliberately high both to support the port and to deter traffic. The tolls act as an unyielding, high tax on small business and are also often the first problem cited by established food businesses. When asked what he would most like government to reform to help his business, Steven Eisenstadt, CEO and president of Cumberland Packing Corp. (which makes Sweet’N Low and Sugar in the Raw, among other products) said: bridge tolls. At $80 a crossing, the trucks make hundreds of trips annually to deliver Cumberland’s raw materials, all of which must be imported to Brooklyn.

A Food Company That's Stayed

Cumberland is the kind of stable, profitable food business that once drove New York’s economy. Located both outside and within the gates of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Cumberland is a family business that is committed to its products, its neighborhood and its 385 employees, about 340 of whom are members of the United Food & Commercial Workers. "We've always made job retention and creation part of our mission," says Eisenstadt, "and have never laid anyone off. We have some antiquated machinery from my grandfather’s day that we keep going for the jobs. We believe in a double bottom line of profit and social responsibility."

Were Cumberland to automate fully, it could slash its workforce to some 80 workers -- which Eisenstadt says it has no intention of doing. Some 200 workers have been with the company for over 20 years.

The 19th century buildings are precisely the kind economists often cite as outdated for today's manufacturing: multi-story with cut-up floor plates and inefficient elevators. But, says Eisenstadt, "We've made it work. We’re profitable and happy here. The navy yard has been very good to us."

The question for the future is: Can the city hold onto its remaining old-time food manufacturers, like Cumberland in Brooklyn or Streit's Matzos on the Lower East Side? At the same time, will it be able to attract and nurture to profitability artisan manufacturers, and use its buying power to support local food?

"Over the last 25 years New York has remade itself into a world-class food city, with a new generation of high-end destination restaurants and markets," says Karen Karp. "Food is why many people come here. Yet our infrastructure, which is from the dark ages, doesn’t match our status as a world-class food city."

Can this be fixed? One thing for sure: The combination of elected officials paying attention to food issues and young voters pouring into the food sector as entrepreneurs and consumers means that food and its many issues will be on the agenda for the next set of elections. That will be a first for city politics and a development that may trigger a new phase in the food revolution.

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a senior fellow at the Regional Plan Association and director of its Center for Urban Innovation.

Food Policy Offers Tasty Morsels, Not a Complete Meal

In 2007, when New York City released PlaNYC 2030, "locavore" had been named the word of the year and Michael Pollan's Omnivore's Dilemma was a bestseller. Despite that, PlaNYC was virtually silent on the role that food plays in our city's sustainability.

The network of activists working to create a sustainable urban food system found this oversight particularly striking. Policies and programs to improve food access, nurture community gardens, promote healthy school food, and run composting programs were being ignored by the city’s sustainability plan.

In response, the four-year update to PlaNYC, releasedon the day before Earth Day this year acknowledged for the first time that sustainable food systems are critical to the city's well-being and included food as a cross-cutting issue. The update included a wide variety of food initiatives, including:

- An effort to use municipal land for urban agriculture, including 129 new community gardens on Housing Authority land and new gardens at schools;

- Continued efforts to work with farmers in the city's upstate watershed to minimize the use of fertilizer and adopt sustainable agriculture practices;

- An expansion of the Food Retail Expansion to Support Health, or FRESH, program that offers zoning and financial incentivizes to encourage supermarkets to locate in under-served neighborhoods;

- An exploration of ways to recycle food waste through composting and biofuel development.

On the Menu

Although Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and various advocacy groups already proposed most of the initiatives in PlaNYC, their inclusion in the mayor's sustainability document signals his intention to carry them out. And that's an important step forward. However, several limitations of PlaNYC raise questions about the long-term impact these disparate policies will have on the city's food system.

PlaNYC does not articulate a vision of a sustainable food system and does not explain how the discrete pieces fit together. A comprehensive food plan, on the other hand, would consider questions such as to what extent urban agriculture contributes to neighborhood sustainability, food security and environmental quality. It would look at how much space we should devote to it, and what additional resources are needed to support urban food production. What mix of farmers markets, CSAs, green bodegas, green carts, community gardens and supermarkets provides ample access to healthy food, and how can the city help ensure that each neighborhood has the right mix? Should New York City change how it buys food for schools and social service programs in order to support regional farmers, or should cost and minimal nutritional quality be the sole criteria?

The City's Role

PlaNYC claims that food "presents a unique planning challenge" because much of the food infrastructure "is privately owned and shaped by the tastes and decisions of millions of individual consumers." But many other complex urban systems addressed in more detail in PlaNYC include private infrastructure and are influenced by consumer decisions. Individual consumers shape the city's housing, energy, telecommunications and transportation infrastructures, all of which include public and private facilities.

In fact, the city controls an extensive food infrastructure. It owns and leases the terminal food markets, regulates and is a major land owner in the rural Catskill-Delaware watershed, and owns the land many urban gardens lease and farmers markets use. Beyond that, the city controls the infrastructure that prepares and serves food to our children and the residential waste disposal system that manages organic matter. And, as one of the largest institutional food buyers in the nation, the city could use the power of its purse to influence large institutional food producers and processors.

Despite this, the city has, until this point, devoted few resources to analyzing the food system comprehensively and so lacks information about it. (It is unfortunate that such research was not conducted between the initial PlaNYC and the update.) As a result, well-intentioned initiatives have been advanced in the absence of basic information about the food system, like the provenance of the food purchased by the city, how much food moves into and through the city, the availability of grocery stores, where people shop for their food, or the location of vacant city-owned land that might be gardened or farmed. The lack of understanding has made it difficult to design efficient, comprehensive, complementary policies as well as to prioritize new initiatives or evaluate their impact. Legislation pending in the City Council (Intro 615) would require gathering these basic metrics about food system, but the mayor's representatives have raised concerns in hearings about their capacity to do so.

Food Matters

Some 45 city agencies purchase food, support food growing, produce compost, teach about food, bring people to supermarkets, make decisions about land use, or regulate how food is grown, processed, distributed and sold This would seem to indicate the sustainability plan could have a major effect on our food system. But, because PlaNYC lacks the force of law, there is no assurance that any initiatives it mentions will be reflected in other agency plans, or that agencies will focus on the food system.

This has real consequences. For example, in the recently released Sustainable Stormwater Management Plan, the Department of Environmental Protection did not consider the role of urban farms in absorbing stormwater, while enhanced tree pits and porous pavement were featured. The Department of Sanitation chose to suspend its leaf and yard waste composting program a few years ago even though urban farmers have been clamoring for compost. The Office of Environmental Coordinationdoes not require developers preparing environmental impact assessments to consider the effects of their projects on the availability of fresh food, although it does require them to assess many other impacts, from open space to traffic. City procurement agencies have never been concerned about buying regionally-produced food, so they have not yet developed systems to track where the food served by the city comes from.

One of the goals of PlaNYC is to accommodate a million new residents in adequate housing located near transit, with functioning infrastructure and sufficient open space. Achieving this goal requires not only higher density development in locations with public transportation within New York City, but also fostering a sustainable foodshed that allows the peri-urban areas surrounding the city to remain relatively undeveloped.

Some cities, like San Francisco, have looked beyond the city boundaries in seeking to obtain municipal food from the region's foodshed. PlaNYC, however, suggests that such an effort would not be within the city’s purview, ignoring the connection between our city and the surrounding foodshed, and how New York City can influence the environmental impacts associated with food production outside of our five boroughs through the power of the public purse.

Overall, the Department of Education serves some 860,000 meals a day, while other New York City agencies serve 225 million meals and snacks annually. Adjusting procurement to give preference to regionally grown food for these millions of meals would channel a portion of what we spend on food to the region's farmers. A bill pending in the City Council (Int. No. 452) would require the city to try to purchase food grown or prepared in New York State. The administration has testified that it would be too difficult to do so for most food contracts.

PlaNYC offers no estimate on how much it would cost to bring the initiatives mentioned in the plan to fruition. For example, increasing access to fresh fruits and vegetables through farmers markets, CSAs and upgraded bodegas requires infrastructure, from wireless Electronic Benefit Transfer readers to refrigerators. Increasing urban farming requires more land, technical assistance, and clean compost. Yet city agencies like health, parks and sanitation are already stretched thin, while a single food policy coordinator, not a fully staffed food department, bears the responsibility for coordinating all these activities.

Only two of PlaNYC’s 198 pages are actually devoted to food. In contrast, just a week prior to the PlaNYC update, Minneapolis issued a comprehensive plan addressing only urban agriculture. Chicago's regional plan, Go To 2040, has an entire chapter devoted to sustainable local food. The New York City Council's own FoodWorks report is a comprehensive 90-page policy plan.

Now that PlaNYC officially acknowledges food to be essential to a "greener, greater New York," food advocates should press for a comprehensive food plan and changes to local law that make sustainable food practices a permanent part of city government.

Nevin Cohen is assistant professor of environmental studies at The New School.

School Boilers Set to Go from Filthy to Not Quite So Filthy

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg April announced the Clean Heat Campaign to end the use of No. 6 and No. 4 heating oil in the city, he made it clear he thinks these fuels are detrimental to the health of many New Yorkers.

While the administration presses private landlords to switch from both No. 6 and No. 4, though, the city itself plans plan to convert nearly 200 of its public schools from No. 6 to No. 4 heating oil --even though the mayor himself has acknowledged the hazards of heating oil No. 4.

"Shouldn't Mayor Bloomberg make it a priority to eradicate, rather than marginally reduce the problem of dirty oil that costs lives?' said Arthur Goldstein, teacher at Francis Lewis High School in Queens, one of the school slated to make the interim step.

Currently 232 city public schools burn No. 6 oil. The Department of Education plans to convert 198 of those schools to No. 4 heating oil by 2015. The other 34 schools are slated to eventually convert directly to No. 2 oil, according to Marge Feinberg, a spokesperson from the Department of Education.

"The faster these schools can switch to natural gas or No. 2 heating oil the better," said Isabelle Silverman, attorney for the Environmental Defense Fund, an organization that works with the mayor's office on the Clean Heat Campaign. "But of course there are those limitations that the city has to deal with."

The "limitations" Silverman spoke of are economic.

The Price of Clean

It costs about $8,000 to convert one school’s boiler from No. 6 oil to the somewhat cleaner but still polluting No. 4 oil. That comes out to roughly $1.7 million in total costs for all 198 schools slated for the transition. Conversely, converting a single boiler to heating oil No. 2 or natural gas costs well over $1.7 million alone, according to Feinberg.

The transition to heating oil No. 2 is far more expensive than the conversion to No. 4 oil, because switching to No. 2 oil requires a full boiler replacement. That full boiler replacement requires the removal of asbestos -- the hazardous mineral fiber that lines and insulates many older boilers. The Environmental Protection Agency began restricting the use of asbestos in the late 1980s because of the damaging effects the fiber has on respiratory health.

Since many of the schools' boilers predate the EPA crackdown, full boiler replacements at these schools would require asbestos removal. Students and faculty cannot be in the building during this process. Thus, construction work must be done during after school hours and on weekends, further driving up worker costs.

Feinberg said the Department of Education has secured enough funding to convert half of the 34 schools it is targeting to switch directly to No. 2 heating oil. No timetable was given for these conversions.

Dangers of No. 4 Oil

The Clean Heat Campaign, which is a part of Bloomberg's PlaNYC2030 environmental initiative, requires that No. 6 heating oil be phased out by 2015 and No. 4 heating oil by 2030.

The 10,000 buildings that burn these two oils account for just 1 percent of the buildings in New York City, but they emit 86 percent of the city's heating oil soot pollution. Heating oil is the largest contributor to air pollution in New York -- a city that received a failing air-quality grade from the American Lung Association.

No. 6 and No.4 heating fuel are lower-cost unrefined residual oils, which when burned, release toxic nickel and heavy soot, or black carbon, into the air, according to the 2009 Bottom of the Barrel report by Environmental Defense.Studies have found that these air pollutants have serious effects on the health of city residents. On average New York’s nickel levels are nine times higher than those in other U.S. cities. High levels of nickel in the air have been associated with increased cardiovascular disease and premature death, according to Bottom of the Barrel. Additionally, soot pollution has been linked to serious respiratory problems.

"We know that exposure to this soot pollution increases asthma emergencies, as well as a wide range of heart and lung ailments," said Rich Kassel, senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council. "Buildings that burn dirty heating oil contribute more particulate pollution than all of the cars and trucks in the city combined."

In order to offset the fact that regular No. 4 heating oil is only marginally less harmful than No. 6 heating oil, the city will require that buildings use low-sulfur No. 4 oil, which is a mixture of No. 6 oil and a larger amount of low-sulfur No. 2 oil. This requirement goes into effect in October 2012.

The Department of Education plans to use low-sulfur heating oil No. 4 going forward at the schools slated for conversion. Low-sulfur No. 4 oil reduces soot emissions by up to 40 percent. However, a significant portion of low-sulfur No. 4 consists of heating oil No. 6, so it still produces large amounts of metal pollution, according to Silverman.

According to the Environmental Defense Fund report, No. 2 heating oil and natural gas emit 95 percent and 96 percent less soot pollution respectively than heating oil No. 6, and both "eliminate harmful nickel emissions."

From 6 to 2

In light of that, some experts think the city should convert directly to No. 2 oil.

The people I talk to, who are experts on the subject, feel strongly that this isn't the best approach that schools should go from No. 6 to No. 2," said City Councilmember Gale Brewer about plans to convert schools to No. 4 oil. "They're urging natural gas and other kinds of fuels that would be much more efficient and healthier going forward.

No. 2 oil offers other benefits as well. Boilers using No. 6 and No. 4 oil require daily maintenance during cold-weather months to remove soot and quarterly maintenance to ensure that the boiler remains efficient over time. No. 2 oil requires maintenance work just once a year, and natural gas just once every other year.

Considering that No. 4 heating oil is supposed to be phased out by 2030, Brewer wonders whether really makes sense to convert from No.6 to No. 4 oil now -- when schools will eventually have to convert to No. 2 oil later.

"They're going to switch it later. I just wonder if you're going to be spending money twice," Brewer said. "You're going to be spending $8,000 now but you will be spending even more money again. Sometimes you have to spend a little more money in the beginning to save money in the end."

As compelling as the argument to convert to heating oil No. 2 is, it’s unclear whether a city struggling to keep teachers in classroom, can afford to put the best boilers in school basements. But the health benefits of No. 2 oil and natural gas use are clear, most experts believe. "From a health point-of-view," said Silverman, "all 10,000 buildings burning four and six oil should switch tomorrow."

From Garbage Dump to Energy Source

For years, popular urban legend on Staten Island held that there were only two things you could see from space -- the Great Wall of China and Fresh Kills Landfill. For over 50 years the landfill served as New York City's receptacle for trash, receiving approximately 29,000 tons of waste each day and spawning mounds reportedly taller than the Statue of Liberty.

The city officially closed Fresh Kills Landfill in 2001 and has since begun a 30-year process of reclaiming it as a park. The Freshkills Park project has become a poster child for Mayor Michael Bloomberg's PlaNYC initiative, a symbol of the city's movement toward sustainable, environmentally oriented growth. But despite the park's draft master plan, progress at Freshkills has been slow.

The vision entails not only converting what once had been a site of environmental blight into a verdant space for recreation and contemplation but also using the area as an energy source. To boost that effort, the Land Art Generator Initiative, or LAGI, a project aimed at integrating renewable energy infrastructure with public art, has announced that Freshkills Park would be the site for its 2012 international design competition, LAGINYC. If successful, LAGINYC has the potential to jumpstart the clean energy efforts at Freshkills -- and turn around 50 years of history for Staten Island.

Energy from Art

LAGI was founded by husband and-wife duo Robert Ferry and Elizabeth Monoianin in 2009 after they moved to Dubai. Ferry, an architect, and Monoianin, an interdisciplinary artist and designer, were inspired by the United Arab Emirates' Masdar initiative to introduce clean energy and sustainability to a region principally founded on the oil industry.

According to Ferry, LAGI aims to "create objects of profound beauty that are at the same time functional generators of clean energy" in the hope that public art "can help the transition to alternative energy." Ferry and Monoianin hope LAGI designs will “stimulate and challenge their viewers to re-conceptualize what clean energy can look like.

"All of the designs are new ways of thinking about renewable energy. … [They] create a vision for what the future can be," said Ferry.

LAGI's first ideas competition was held in the United Arab Emirates in 2010, drawing in hundreds of submissions from 40 countries worldwide. A panel of international artists, architects, academicians, industry leaders and writers chose Lunar Cubit as its winner in January 2011. Lunar Cubit, conceived by a New York-based team of Robert Flottemesch, Jen DeNike, Johanna Ballhaus and Adrian P. De Luca, proposes nine solar-paneled pyramids outside of Masdar City that would light up in accordance with the lunar cycle and generate energy for up to 250 houses in Abu Dhabi.

Runner-ups included Windstalk, a design for poles that use wind power in an effort to create a wind farm without turbines, and Solaris, a design for roughly 1,500 solar panels that resembles an ocean over the desert.

The winner of the LAGI competitions receives a $15,000 cash prize. LAGI, however, does not guarantee the construction of a design, although the initiative hopes to ultimately realize this goal. Ferry admits that Lunar Cubit's construction is still unclear, but he stressed that LAGI's intention is not just to generate innovative designs, but to build them as well.

"We're in really promising talks with very high-level people who have the ability to make it happen. … These things take time," he said.

From Garbage to Green

LAGI's mission is particularly relevant for Freshkills, whose history, according to park administrator Eloise Hirsh, has "carved a big, psychic scar for Staten Island." Ten years ago, the area was both environmentally dangerous and visually repellent. LAGI could turn that around by generating designs that have the potential to not only power thousands of homes with clean sources of energy, but transform the blighted landscape into something beautiful as well.

Aesthetics play a key part in correcting what occurred at Freshkills, Ferry thinks. "It's important that [clean energy infrastructure] responds to our natural desire for beauty and conceptual layering and interest rather than just having simple utilitarian objects."

The LAGINYC competition will complement the city's ongoing environmental efforts, Ferry said, which both "work to integrate renewable energy policies" and "embrace ambitious public art." In Hirsh's view, it's particularly fitting that the competition involve Freshkills, a park whose principal mission is to "promote innovative strategies for environmental sustainability."

Wind and Sun

Freshkills is not new to clean energy initiatives. Already the park boasts a gas collection system that recovers methane from the site's decomposing waste. The methane, sold to National Grid for $12 million a year, heats up to 22,000 homes in Staten Island. The Department of City Planning estimates that methane can be harvested from the site for at least 30 years.

The city also is looking into the feasibility of solar and wind power, although no plans have been formalized. In an April speech, Bloomberg announced a new PlaNYC target to generate 50 megawatts of clean energy from solar power plants installed over landfills.

While no specific development has yet to occur, Freshkills would be a prime location to carry out such a project. "The understanding was the Freshkills would be a part of that," said Nick Dmytryszyn, the environmental engineer for Staten Island.

The location is also seen as a prime site for wind energy. A 2007 study conducted by the New York State Energy Research and Development Agency confirmed that Freshkills could support seven wind turbines and generate up to 17.5 megawatts of energy, over a third of Bloomberg’s targeted goal.

"The fact is that it is doable, achievable," said Dmytryszyn, adding that the turbines "could supply the energy needs for 3 percent of the Staten Island population."

Borough President James Molinaro, one of the city's leading proponents of wind energy, has spent over three years trying to convince city officials of the feasibility of wind turbines at Freshkills. Last month city's, Environmental Protection commissioner, Cas Holloway, announced that the administration would look into Molinaro's proposal, promising Staten Islanders that they will "see movement on that pretty fast."

As of now, however, both the wind and solar projects are vaguely defined, and their actual implementation is far from certain.

"We're very hopeful about the feedback that we will get, but the projects are still in the pre-feasibility stages. We have commissioned studies and are awaiting findings," said Michael Saucier, press secretary for the Department of Environmental Protection.

Restoring a Landscape

Once completed, Freshkills Park is slated to be 2,200 acres, roughly three times the size of Central Park. Visions for the area are just as expansive. Freshkills will offer space for mountain biking, running, kayaking, and horseback riding, as well as cultural and educational programming. It will also serve as a focal point for the borough, with an "expansive network of paths, recreational waterways, and a system of park drives" that will connect it to surrounding neighborhoods.

At the heart of the Freshkills project, however, is a commitment to environmental renewal. According to Hirsh, it will "stand as a symbol for the kind of transformation that can happen in seriously compromised sites."

The Department of Parks and Recreation has various plans to restore the park's wetlands, eradicate invasive plants, and support a diverse wildlife habitat at the former landfill.

"They've made ecological restoration part of the vocabulary,” said Deborah Popper, a professor of environmental studies at the College of Staten Island. "You can definitely see things … changing. … You can see the trees being planted, then starting to take off. [Freshkills] is beginning to look very, very different."

But with recent delays in some of the park's preliminary projects, such as Owl Hollow Fields and many of Freshkills' clean energy proposals barely in the planning stages, some residents feel this transformation is still far off.

"Most of the Staten Island community, while welcoming something of this size, has realized [they] won't see it come to fruition in their lifetime," said Dmytryszyn. "There's always hesitation that there' s not going to be funding for a park of this size -- in Staten Island of all places."

While Popper has seen significant changes at Freshkills over the last five years -- including increased access into the Park, ecological restoration and city-sponsored special events -- she admits that many residents remain skeptical.

"People really remember, and it wasn't even that long ago, how horrible the place smelled. … You don’t forget that easily," she said. "For years its been drilled into people: It's not a safe place."

Echoing Dmytryszyn’s concerns, Popper acknowledged the residents' resentment and distrust of city officials.

"Why did the rest of the city give us garbage?" she said. "It's that constant feeling that we're off in the sidelines even though we're the borough that's growing so fast, even though we're the borough that’s contributing so much."

From Drive-Through to Destination

Perhaps, LAGINYC could help change that. A large-scale, site-specific installation at Fresh Kills could transform Staten Island. The island, which Freshkills Park designer James Corner once called "the place people drive through on their way to somewhere else," could "capture the imagination of the world," according to Ferry.

Echoing this sentiment, Hirsh said, "It's really going to be a great way to get creative attention to the many opportunities and constraints of this site, to Staten Island. It will help us engage larger public conversation."

Moreover, if the design actually is constructed at Freshkills, Ferry envisions it would draw attention to the park and its environs. Ferry believes the competition could have profound effects for Staten Island by providing "cultural value, economic development value [and] tourism potential."

For Staten Island, "the forgotten borough" as some call it, this would be true vindication for its 50 years as New York's garbage site. Perhaps, Popper said, Staten Island "could become a central spot instead of a congested pass-through." And, she said, if LAGINYC and, on a broader scale, Freshkills Park, succeed, future New Yorkers "won’t even know what it used to be."

Budget Cuts Could Beach Some City Swimmers

The heat of the late-afternoon sun beats down on the dry floor of the Douglass and DeGraw "Double-D" Pool in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn. The pool's entrance gate is padlocked. Not a soul lurks on the premises.

New York City's outdoor pool season does not begin until June 29. But some city residents face the prospect of seeing their community pool remain as devoid of life and water as Double-D Pool is now for the entire summer.

For the second straight year, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has proposed cuts in funding for New York City swimming pools to help close the city's budget gap. The budget proposal for fiscal year 2012 calls for the closure of four, as yet unnamed, city swimming pools and a shortened season for all pools.

Last year Double-D Pool, along with Wagner Pool in East Harlem, Fort Totten Pool in Queens and West Brighton Pool on Staten Island were slated for closure. Additionally, all of the city's 54 pools were set to close two weeks earlier than the usual Labor Day end date.

Fortunately for pool-goers, the City Council restored a portion of funding to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation at the 11th hour. This move saved the four pools from closure and allowed the summer pool season to continue through Labor Day.