Stated Meeting: Con Edison Rates and Reporting on Pesticides

In its latest evidence of displeasure with Con Edison, the City Council approved a resolution endorsing Council Speaker Christine Quinn's efforts to become an active party in the debate over the utility's proposed rate hike. At its stated meeting on October 17, the council also approved stricter reporting standards on the city's use of pesticides, closed a tax exemption loophole for a housing program and approved several modifications to the budget.

Blasting Con Edison

In May, Con Edison proposed a rate increase that would bump up residential customers' bills by 17 percent and commercial customers' bills by 10.7 percent next year. The proposal is currently before the state Public Service Commission, which must approve the utility's rate hike.

By giving Quinn the go ahead to join the commission's proceedings, the council would be privy to hearings, notices and documents regarding the rate increase. The resolution doing just that (Res. 1059) was unanimously approved by a voice vote.

The council's decision to formally join discussions regarding Con Edison's rate proposal is just one more example of the clash between the council and the utility. Prior to the resolution's vote, Quinn responded to the recent suggestion that the utility company would sue the city, claiming it was responsible for a steam pipe explosion this summer. In a letter to Con Edison, Quinn and Consumer Affairs Committee Chairman Leroy Comrie questioned the utility's evidence suggesting that leaky water pipes might have caused the blast.

"We've seen over the past year and half some stunning failure on the part of Con Edison," said Quinn in a press conference prior to the meeting. "In response to those actions most people would put their nose to the grind and try to do a good job. Con Edison, instead, has requested a 17 percent rate increase from their customers."

Members of the council came out against the rate increase last month, stating Con Edison would have to detail its capital expenses and provide better service before it is rewarded.

Use of Pesticides

Following up on a bill passed in 2005 that limited the use of pesticides in the city, the City Council approved legislation (Intro 612) that would clarify how the chemicals' use is monitored and reported. The bill was approved by a vote of 49 to 0.

Currently, the law requires city agencies to summarize the use of pesticides within their department and provide that information to the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the speaker of the City Council. The new legislation, which was sponsored by Councilmember James Gennaro, would also require the commissioner of the health department to submit an annual report summarizing pesticide use by all city agencies to the speaker.

"While the current law already prohibits the use of certain toxic chemicals by city agencies, today's legislation will allow the department of health to better and more efficiently evaluate agency use of pesticides in our communities," said Health Committee Chair Joel Rivera in a prepared statement.

Revising the Budget

As part of Quinn's budget transparency initiative, the council also released several revised budget documents that reveal the recipients of funding for large, citywide budget initiatives. The revisions (Res. 1090) were approved by a vote of 48 to 0.

When the budget was approved in June, the council released a list of member items – programs and initiatives that received grants in this year's budget – and included the name of the individual councilmember who proposed them. Gotham Gazette analyzed this list and revealed that programs proposed by Councilmember David Weprin had received the most funding. (For a full breakdown of who received the most, or the least, amount of funding in June click here.)

This new release details which organizations received city funding for broader initiatives, like a homeless prevention initiative proposed by Councilmember Annabel Palma. In June, the documents only listed the title of the citywide program and the amount of funding. Now, the document reveals which organizations will receive funding, how much they will receive and what councilmember proposed the initiative.

The council also released the names of organizations that received funding from the council members' discretionary funds dedicated to programs under the purview of the Department of the Aging and the Department of Youth and Community Development. Each member can dole out $151,714 for youth programs in his or her district and $108,750 for senior initiatives.

Closing A Tax Exempt Loophole

Under a program within the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, homes in poor condition can be purchased by the city, rehabilitated and sold to an individual who meets certain income restrictions. That owner would also receive a 10-year tax exemption.

Currently, if the owner were to resell the home, the second owner would also receive the tax exemption, regardless of income and assets. The council voted 49 to 0 to approve a rule change that closes this loophole. The tax exemption now terminates as soon as the home is sold to a second owner.

Public Plazas

The council also approved by a vote of 49 to 0 an amendment to a rezoning resolution (Res. 1103) that makes privately owned public plazas more inviting to the public. According to a City Council press release, the amendment will update design standards, including restrictions on size, seating, lighting and bike parking, and attempt to preserve and incorporate the character of the neighborhood.

Medical Examiner Redefined

To update the definition of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, the City Council approved legislation (Intro 604) that includes responsibilities the position has acquired over time. As technology progresses, the office has taken on larger tasks that are not reflected in the City Charter, such as DNA and forensic testing. The legislation, sponsored by Rivera, reflects and updates the office's responsibilities.

Â

Earth Day for the Internet

It was one of those moments when you get afk (away from keyboard) and meet irl (in real life).

On Saturday, September 22, a crowd of 150 or so people gathered in rain-soaked Washington Square Park to celebrate the Internet and raise awareness of the threats to its future.

This was One Web Day in New York. Susan Crawford kicked it off by talking about the threats to the Internet posed by government censorship in countries like China and by unchecked telecom monopolies in the United States. Crawford is a law professor who sits on the board of Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, which coordinates addresses on the Internet. She founded One Web Day last year as "a global Earth Day for the Internet," as she puts it, "to make sure that everyone understands the threats to our shared online future."

In battling those dangers to the Internet, One Web Day's philosophy seems to be that a good offense is the best defense.

Earlier in the day, New York University's Home Interactive Telecommunications Program had offered free classes in how to use online tools like Wikipedia and ShiftSpac -- which lets users modify any webpage through their browser and share the modifications with other users, so people can use it to customize, contextualize or improve anything they find online. Later, there would be a party at For Your Imagination (FYI) with Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, as the guest of honor. (The not-so-secret password for the event: IRL.)

A Worldwide Event for the Worldwide Web

There were related but autonomous celebrations around the world: In Ethiopia and Benin, cybercafes and universities offered free or discounted Internet access along with tutorials to get more people online. Many chapters of the Internet Society, an international professional membership association that establishes standards for the Internet, organized local events in Israel, India, Ecuador and elsewhere.

Democratic presidential candidate John Edwards released a statement in honor of the event emphasizing the need to close the digital divide and preserve the democratic nature of the Internet.

Probably the largest 2007 One Web Day event was in Berlin, where a reported 15,000 people marched to protest proposed government data retention policies. The new measures would shift Germany from being country with a constitutional right to “informational self-determination” to one with extremely aggressive surveillance measures, giving the government access to all communication and travel records, people’s biometric data and personal computers, even in the absence of a crime.

The policies are very broad, endangering doctors and journalists specifically, as well as the average German citizen. According to one of the few English language reports on the event, protesters chanted, "We are all 129a," referring to the expansive "Anti-Terror Paragraph" of the German Criminal Code. People held banners saying "Freiheit statt Angst" ("liberty instead of fear") and wore t-shirts with the face of Wolfgang Schäuble, the interior minister pushing the measures, over the phrase "Stasi 2.0," a reference to the old East German secret police.

One American observer described the German reaction to this kind of government overreaching as visceral. The protests against the measures, organized by the Working Group on Data Retention, have grown from just a couple of hundred at the first rallies a year and a half ago.

Promoting Awareness

Despite recent revelations about U.S. phone companies’ secretly collecting data on individuals at the federal government’s behest, things weren't quite so spirited back in overcast New York. Still, the speakers caught the attention of various passers-by.

While Dana Spiegel, executive director of NYCwireless, was speaking about his group’s efforts to hook up various city parks with wi-fi, an NYU student stopped to inquire what the event was about. She turned out to be a member of the campus chapter of Amnesty International, which is focusing on Internet censorship this semester. She had not heard of One Web Day before, but got instantly excited about it and starting collecting contact information.

Birju Pandya talked about his lighthearted efforts to promote goodwill with technology through Charityfocus.org. Andrew Baron spoke of the inspiration to start Rocketboom, one of the earliest video-blogs on the Web. I was there to announce the Digital Expansion Initiative, a community-led research effort to assess the barriers to Internet access in New York City.

There was nothing fancy about any of the speeches – no Powerpoint or flashing lights. But having it in the park definitely attracted attention. While Jimmy Wales was speaking, five women who appeared to be from three generations of the same family passed by. "That's the founder of Wikipedia," one of the younger women said. "You know Wikipedia?" The grandmother nodded.

Setting an Example

The city government has been holding public hearings into the state of Internet access for New Yorkers, with one in the Bronx in March, another in Brooklyn in May and additional ones planned for the other boroughs before the end of the year. They have had attracted a turnout comparable to that at the One Web Day event, but awareness of these Broadband Advisory Committee hearings across the city is appallingly low. (As part of the Digital Expansion Initiative’s citywide phone survey, researchers at NYU have been asking people if they've heard anything about it; so far not a single person has.)

Perhaps that's because the Broadband Advisory Committee has held the hearings in very official, but cloistered auditoriums during the day on weekdays. And the primary mode of announcing the events has been through email. In neither case are you likely to attract working folks who lack computers. The committee should be out in Washington Square Park (and Marcus Garvey Park and Maria Hernandez Park), especially considering that they're not just celebrating the Internet, but debating concrete proposals for local action to shape its future.

Crawford points out that Earth Day really took off because people had a picture of the Earth from space. One Web Day is trying to make the Web visible and tangible in the same way. "Being outside is important is because the point is to show that the Web is made of people," she says.

Crawford and her growing network of supporters and volunteers are already making plans for September 22, 2008. They hope to get schools and students more involved and to strengthen connections with groups like the Internet Society and the American Library Association. Like any good Web project, they are at once trying to strengthen the One Web Day organization and yet decentralize the organization's activities.

So, can we expect to see a 15,000-person protest march in New York City next year like the one in Berlin? Crawford says maybe: "We'll see things like that in the U.S. when we wake up." Â

Storm Warnings

Until the middle of the 20th century, such monsters weren't given names. They were simply called hurricanes. This particular hurricane was no simple one. At its peak, it had winds in excess of 160 miles per hour. It spit out storm surges from 10 to 12 feet. It whirled and raged up the Atlantic seaboard until it made landfall on Long Island on Sept. 21, 1938.

Once on land, it tore out a piece of Long Island, leaving a permanent hole, now called Shinnecock Inlet. It swept an entire movie theater, with 20 patrons inside, out to sea. It brushed aside whole farms, knocked out all electrical power above 59th Street and left the Bronx in total darkness. Before it was done, this storm, later to be called the Long Island Express, would take 700 lives, leave 63,000 people homeless and inflict $308 million ($6 billion in today's figures) worth of damage.

Could this happen again. And, if so, what can we do to protect lives and property?

Many experts say yes. "Roughly every 70 years the New York region gets a monster hurricane," Bill Evans, WABC-TV senior meteorologist and co-author of the new novel Category 7 wrote in an opinion piece in Newsday.

The National Hurricane Center's statistics corroborate Evans’ prediction. There seems to be a 20-year pattern in the frequency and intensity of Atlantic coast storms and hurricanes. Based on this pattern, the New York area can expect one or more category 3 Atlantic coast storms in the next several years.

|

Be Prepared The Office of Emergency Management has sent out over a million brochures, entitled Ready New York (Hurricanes and New York City), that give advice on what to do if a hurricane strikes and also designates where the evacuation zones are. As a first step, the office’s press secretary, Andrew Troisi, recommends that you go to the Office of Emergency Management's web site or call 311 to find the location of your local evacuation center. The office also recommends that New Yorkers: --develop a plan designating a place where the family should meet in case of an emergency; --create an emergency kit with 1 gallon of drinking water per person, canned food and a manual can opener, first aid kit, flashlight, radio (preferably the wind up kind that doesn't need batteries), 1 quart of bleach and an eyedropper for disinfecting water, phone, whistle and personal hygiene items; --put together a "go" bag in a waterproof package with things you may want to take with you in a waterproof package such as ATM and credit cards, $50 to $100 in cash, copies of important documents, car and house keys and current medical information, including doctors’ numbers.

|

|

Such a storm, Evans writes, "could send a 22-foot surge of water into Manhattan streets. Subways would be out for months …. Low-lying neighborhoods south of Sunrise Highway would be unrecognizable."

The city has not ignored this danger. Faced with the possibility of a severe hurricane or other storm, New York City’s Office of Emergency Management has developed a comprehensive storm plan for the city. It has assembled emergency plans, designated evacuation routes and advised New Yorkers on how to prepare (see box). But critics say the plan does not do enough.

Certainly New York presents some particular challenges to emergency planners. These include:

-- Many routes out of the city, jammed even on a normal rush hour, could become totally impassable in the event on an evacuation.

-- Millions of New Yorkers do not have cars they could use to evacuate the city.

-- The city is home to a large number of nursing homes and hospitals with sick and elderly people who could be difficult to move in an emergency.

-- New York’s aging infrastructure has proved vulnerable even to relatively minor downpours and storms.

Has the city done enough to address these concerns, particularly in low-lying areas such as the Rockaways? What more needs to be done?

Dangerous Storms

A hurricane is an organized rotating weather system that develops in the tropics and has a warm center of low barometric pressure with sustained winds of 74 miles per hour.

The strength of all hurricanes in the Western Hemisphere is measured by the Saffir-Simpson scale, which classifies storms into categories 1 to 5 based upon their wind speed and the height of the storm surge -- the coastal water blown inland.

A category 1 storm has sustained winds of 74 to 95 miles per hour and a storm surge of 4 to 5 feet. A category 5 hurricane has sustained winds of at least 156 miles per hour and a storm surge of 19 feet or more.

The New York-Long Island area has been hit by four category 3 hurricanes, with the most recent onestriking Long Island in 1960.

But hurricanes aren't the only potential threats out there. A Nor’easter, named because it generally travels northeast up the Atlantic seaboard, is not as organized or as windy as the hurricane but because it hangs around longer, can be just as destructive. A Nor’easter is formed when the cold dry arctic air of the jet stream blows south and collides with the warm moist air of the Gulf of Mexico. The resulting quarrel gives birth to an icy storm. Nor’easter winds are not as intense as those from hurricans, but because the storm has no eye and is irregularly shaped, a Nor’easter can cover a greater distance and therefore inflict as much damage as a hurricane.The City’s Plan

To cope with severe storms, the Office of Emergency Management has divided the city into three different kinds of zones -- A, B and C – ranked according to their likelihood of being flooded, according to the office’s press secretary, Andrew Troisi.

Zone A areas are low-lying lands likely to flood if any hurricane strikes the city. These are located in lower Manhattan, Coney Island and Brighton Beach, parts of the Rockaways, southern Queens and large sections of the coasts of Staten Island.

Zone B areas are less vulnerable low-lying lands where there will be flooding if a severe hurricane – category 3 or higher -- strikes the city. Zone B areas include Roosevelt Island, City Island and much of southern Queens, including John F. Kennedy International Airport.

In Zone C areas, flooding would occur only if a category 4 or 5 hurricane strikes the city. Among these areas are parts of East Harlem, and much of the eastern Bronx.

Most areas of the city, neighborhoods in the middle of Brooklyn and Queens, for example, as well as much of Manhattan’s West Side, are considered to be safe from a storm surge, regardless of the intensity of any hurricane. The city has not designated any evacuation center for New Yorkers in these sections.

Although New York is surrounded by water – and located on three different islands – unlike New Orleans, most of the city does not lie below sea level. "We can keep New Yorkers safe as long as we can get those affected to shelter," Troisi says. Currently, the city could provide shelter for more than 600,000 people.

In general, the city has tried to encourage New Yorkers to prepare themselves for a hurricane or other disaster (see box). "The key to any plan begins with education. First, find out if you live in an evacuation zone, then find out where your local evacuation center is," Troisi said.

To help residents find their evacuation center, the city has an on-line Hurricane Evacuation Zone Finder.

Subways, Cars and Buses

Since so many New Yorkers do not own cars, the city would use public transportation and extra buses to evacuate as many as 2 million people.

But simply having a vehicle might not be enough, Evans said in an interview. In a hurricane or other emergency, he said, "It's a matter of evacuating 2 million frightened people by public officials who have no experience in dealing with a crisis of this proportion. It's a matter of convincing people that this is something that they have never faced before…. People must realize that flooding is different from snow. We can shovel away many feet of snow; you can't shovel the ocean."

New Yorkers who normally rely on the subway system might find it shut down during a severe storm. Severe downpours and, in some places, high winds, shut down much of the subway system on August 8. Last week, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority issued a report concluding it had been unprepared for the storm and mishandled many aspects of the situation, particularly communicating to its own staff and to riders about the service disruptions. The authority committed itself to a number of steps, from giving Blackberry-like devices to its employees to installing new valves on drainpipes, to help prevent similar problems in the future. But despite such measures, authority executive director Eliot Sander said major storms would still have the potential to disrupt subway service in the future.

The Bronx River Parkway during the 2007 Nor'easter.

The sick and elderly could be particularly hard to evacuate. The office of Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer reviewed 49 nursing homes last year and found that the state department of health had failed to adequately prepare them for evacuation.

" After the lessons learned from Katrina and the 9/11 attacks," Stringer said in a December 2006 press release, "it’s unacceptable, for New York not to have viable emergency plans for our most vulnerable residents."

For its part, the city has considered the problem of the sick and elderly and would be prepared to evacuate them, Troisi said. "Under our emergency evacuation plan we will move the sick and elderly to safety first," he said. Government agencies would have time to prepare because, Troisi noted, "a hurricane is the one natural disaster that we will have ample warning that it is approaching."

Consulting the Community

To improve the plans, many observers call for more involvement from community leaders and residents.

" Right now there's too much planning from on high, and not enough discussion with local officials," Mike Duvalle, a community leader in the Rockaways, said. City officials, he said, need to "work out a comprehensive plan with local officials -- and then you allow them to do what's needed, enact the plan, without having to go to back to city or state authority for permission."

Community Emergency Response Teams provide some role for individual neighborhoods in dealing with disasters. The teams receive training from the police and fire departments in basic emergency response. During the August tornado in Bayridge, for example, the local CERT responded and helped clean up, according to Laura Singara, press secretary to Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz. The community teams in Sea Gate and Coney Island filled sandbags to prepare for a severe storm a few months ago.

The Vulnerable Rockaways

A major storm would not affect all parts of the city equally. Perhaps no area could prove as vulnerable as the Rockaways, a low-lying coastal peninsula with limited transportation.

Some 100,000 people live in Far Rockaway. The area, according to Duvalle, has the highest concentration of nursing homes and residential care facilities in New York. He estimates it could be home to as many as 3,000 sick and elderly people.

For the people in the Far Rockaway evacuation zone, the Cross Bay Bridge provides is only practical way out. The only other route is via the Nassau Expressway, a road running east from the Rockaways, which could be vulnerable to flooding. "We only have one subway out of the area, and that line is an elevated one and therefore it is exposed to the full brunt of a hurricane," Duvalle said. "We can't depend on evacuation alone."

John Baxter, cable talk show host and Far Rockaway community leader, laughs when asked whether the city is prepared to evacuate 3,000 people from Rockaway. "Get down on your knees, and say a prayer, and while you're down there kiss your butt goodbye," he said. "There is absolutely no way you can evacuate all these people."

To try to provide additional ways out, Queens Borough President Helen Marshall obtained money to buy Jet Skies for water rescues and inflatable water rescue rafts for the fire department. She now wants funds to purchase ferries that could be used to help evacuate Far Rockaway, press secretary Dan Andrews said.

" We must use all our resources," Duvalle said. "We can have private yachts listed for the purpose of evacuation. We should provide generators for gas stations in case of power outages - their tanks need electricity in order to pump. Our cars need their pumps in order to evacuate."

In addition Marshall believes steps must be taken to prevent disastrous flooding before it occurs. "Part of the reason why in the past southeast Queens has suffered through chronic flooding, is because the growth and development of the infrastructure has never kept pace with the growth and development of the area's population," Andrews said.

Flooding in the Rockaways

Evacuation would not be the only problem, according to City Councilmember James Sanders, whose district includes Far Rockaway and flood-prone southeastern Queens neighborhoods. He is concerned about Belmont Park racetrack, where many of his constituents could be taken in the event of a disaster. According to Sanders, "Some experts have noted that Belmont itself is on low-lying ground and in the event of a Katrina-like storm may be prone to flooding."

Sanders thinks the city should consider an alternative approach called sheltering in place. "The idea is when evacuation is neither possible or practical you make use of resources at your disposal and shelter in place," Sanders said. In Far Rockaway, where there are many tall apartment buildings, it could make sense to set up evacuation centers on upper floors of those buildings.

Jonathan Gaska of Far Rockaway’s Community Board 14 has doubts about this idea. Without backup generators, he said, these buildings could be without electricity, knocking out elevator service.

In general, Sanders faults the city’s planning for his district. "As a former marine I understand a little something about survival," he said. "Survival is a mindset that comes from preparation and creative thinking. The OEM's present mindset of evacuation alone doesn't have enough in regard to the former and nothing in regard to the later. My worse nightmare is for my district, in the wake of a Katrina-like storm, to end up being New York's Ninth Ward."

Not everyone in the Rockaways is critical of the city. Gaska said Katrina was "a slap in the face" that changed the attitude at the Office of Emergency Management. Since then, he said, "The OEM has been very good working with us." While the office has not agreed to all the community board’s requests, it has posted evacuation route signs along the peninsula and put backup generators in firehouses.

A Growing Threat?

Some meteorologists fear that New York could face an increased number of severe hurricanes in the future. They point out that, while the frequency of hurricanes has remained the same, the intensity of the storms has increased. Some say global warming could be causing this, although other scientists consider such arguments alarmist.

The experts disagree on whether global warming contributed to the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina, but some believe that if the ambient water temperature of the Atlantic Ocean goes up by one degree Celsius the higher water temperatures could create monster hurricanes. In light of this, could a category 5 hurricane strike New York?

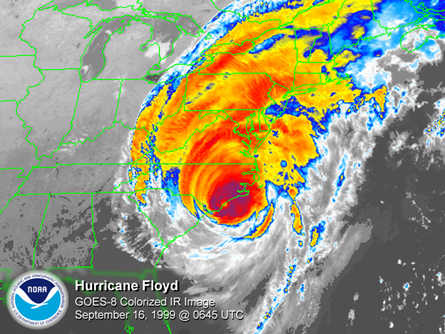

Officials feared Hurriance Floyd might hit New York City in 1999 but its effects on the city were minimal.

Troisi says no. "The temperatures of the waters surrounding the city are simply too low to allow for the development of any hurricane above the magnitude of a category 3," he said.

But a trip to the Rockaways leaves no doubt that even a category 3 storm could pose a major challenge. Duvalle drives over the Crossbay Bridge where vast expanses of water are all one can see on either side. "Imagine this highway filled panicky drivers in the middle of hurricane weather," Duvalle said.

On Rockaway beach scores of newly constructed condos are going up. A short distance beyond the condos is a narrow beach, beyond that nothing but a vast expanse of ocean and sky. Along the sea's horizon, misty white clouds are swept along by a steady wind. Speaking over the wind, Duvalle anticipates a future storm. "It is coming," he said. "It is not matter of if it comes - it is matter of when."

Thurman William Mathis is a schoolteacher who writes for the Queens newspaper "Our Times."Â

How Clean (or Dirty) Is Our Air?

During the spring, buried in the thickets of the debate over congestion pricing, was a great nugget in Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s PlaNYC 2030. Deep in the document was a promise: if PlaNYC 2030 was implemented, New York City would become the “cleanest big city in America.”

That got me thinking.

How clean is the air in New York City?

The short answer is that the nation’s air is cleaner than it’s been in decades, and so is New York’s. But New York City air is still polluted enough to send thousands of people to emergency rooms every summer and to send some of those people to early graves every year.

The longer answer is more complicated, and it goes like this:

Since 1970, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agencyhas set standards for the maximum amount of air pollution that is safe to breathe. In a city like New York, ozone (a principal ingredient of smog) and particulate matter (or soot) are the key pollutants—and the city has never met EPA’s standards for either pollutant. In each case, we are in the second-worst category (Los Angeles tops the "most polluted list" for both smog and soot). By this measure, the city seems to be in pretty bad pollution shape—especially because many environmental groups think that the current EPA standards are too weak.

Soot particles are the biggest pollution concern. A decade ago, the Natural Resources Defense Council (where I worked then, and now) estimated that 64,000 Americans died prematurely every year at then-current levels of particulate air pollution. More than 4,000 people of those premature deaths were in the New York metropolitan region.

In New York, diesel engines have long been at the heart of our local soot problem. When walking up Madison Avenue, most of the soot we breathe comes from a relatively small number of diesel engines—buses, trucks, and construction equipment. In more residential neighborhoods, home heating oil is diesel’s close—and even dirtier—cousin.

Sources of Particulate Soot on Madison Avenue

Diesel (and home heating oil) soot is really toxic stuff. If it’s not effectively filtered in the tailpipe, typical diesel exhaust contains dozens of cancer-causing chemicals. This toxic soup has been found to be at least a probable or likely human carcinogen by many of the world’s leading public health agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the National Toxicology Program and regulators in Germany, California and elsewhere.

Luckily, diesel soot pollution is a fixable problem. As of this year, all new diesel truck and bus engines are equipped with filters that remove more than 90 percent of this soot. And, NYC Transit buses have used these filters effectively for several years now, reducing their fleet-wide emissions by more than 95 percent since 1995. But most trucks, buses, and construction equipment don't have these filters.

So, in 2005, the Boston-based Clean Air Task Force revisited the soot problem, and focused on the specific problem of diesel soot. The task force estimated that people in Manhattan inhale enough toxic soot particles to create a lifetime cancer risk that is more than 3,200 times EPA’s so-called “acceptable” cancer risk. It gets even worse: According to the task force, more than 40,000 asthma attacks and almost 1,800 premature deaths were attributable to diesel soot pollution in neighborhoods throughout the city in 1999. That’s why the American Lung Association recently gave the City an “F” for its particulate soot levels.

But is the air really so horrible? As I write, the sky outside my window is bright blue. My daily “EnviroFlash” email from EPA and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation tells me that today’s pollution levels are “good” for both particles and ozone.

OK, I know better: EPA and environmental conservation department give a regional estimate. That estimate tells me nothing about local conditions. Recent studies show that diesel soot emissions along roadways create corridors of increased pollution, which leads to higher health impacts. Perhaps the most famous example can be found in northern Manhattan: With five Metropolitan Transit Authority bus depots and several busy north-south truck routes, Harlem and Washington Heights have higher air pollution levels—and much higher asthma rates—than their southern neighborhoods.

All of this underscores two important themes. First, it is important to acknowledge that we’ve made significant progress in reducing many sources of air pollution over the years, and our air is cleaner as a result. But, second, it is equally important to understand the job isn’t finished—we still fail to meet EPA’s health standards for ozone and particulate soot, and we need to create new ways to address the remaining sources of air pollution that seem to be pocketed in certain areas of the city.

Mayor Bloomberg’s PlaNYC 2030 strives to ensure that “every New Yorker” should breathe the cleanest air of any big city in America. We’re not there yet. Next month, I’ll dive into the plan and explore whether the plan will us meet his goal.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization, and is on the boards of the New York League of Conservation Voters and Transportation Alternatives.

Â

Making Coney Island Green

The city took a step toward sustaining historic Coney Island this summer when it put a roadblock in front of a $1.5 billion plan by Thor Equities to turn the legendary area into a resort enclave. As New Yorkers warmed up on Coney’s beaches, the administration threw cold water on the proposal to speed up the rides and bring in hotels and time-shares. Thor’s scaled-back plan, which included a glass-enclosed water park, three hotels and 400 time-share units, restaurants, movie theatres and high-tech arcades, was a bit much even for a city administration that likes to think big.

Now the question is whether the city can come up with an alternative that helps to sustain and build up what is left of the storied amusement area. Will they be able to do it without a mega-developer like Thor? And will the city continue to react to the schemes put forth by private developers rather than coming up with ideas of its own?

As incongruous as it might seem, Coney Island, with its honky-tonk image, could become a model of sustainable development. If the city wants that to happen, it could look to some key decisions already made at Coney.

Where’s the Plan?

New York City’s long-range sustainability plan, PlaNYC2030, says little about unique areas like Coney Island, which don’t fit in the category of residential neighborhood or an average business district. However, Coney Island redevelopment could play an important role in meeting the plan’s objectives of insuring that all New Yorkers live within a 10-minute walk of open space, cleaning up the city’s waterways, improving mass transit and air quality and reducing global warning.

If the past is any indication, the way to accomplish these objectives is through carefully thought-out small steps over a long period of time instead of giant commercial adventures and “big ideas.” For example, long before PlaNYC2030, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority renovated the Stillwell Avenue subway station, making it the greenest, most energy-efficient subway station in the city. Completed in 2006, the station has photovoltaic panels that provide solar energy and an open design that maximizes the use of natural sunlight. This example of smart design and public policy has given a small boost to the private amusement area and to many public facilities in the area.

Previously, the city preserved the Cyclone, Coney Island’s famed roller coaster that opened in 1927. It became a city landmark in 1988 and a federal landmark in 1991. This mostly wooden structure remains an icon of the amusement area, marking its identity as distinct from the kind of high-tech, high-priced theme parks epitomized by Six Flags.

The corporate amusement giants also cannot replicate the non-profit, Coney Island USA a focal point for many unique cultural and civic groups that have helped keep the historic area alive. And in yet another small step, the city government and the Coney Island Development Corporationnow plan to develop Steeplechase Plaza, a public park that would feature a restored B&B Carousel.

So it may be smarter for the city to think smaller and move one step at a time. The popularity of the relatively tiny Nellie Bly Amusement Park, only a couple of miles from Coney Island near Bensonhurst’s waterfront, suggests that many small parks might work better than one big one.

Stadiums On The Island?

In an earlier effort to spark development at Coney Island, the city encouraged the building of Keyspan Park, where the Brooklyn Cyclones minor league baseball team plays. This was a questionable addition to Coney Island’s waterfront when it was built during the Giuliani administration. The minor league field broke the classical Coney Island model that combined amusement park, beach and boardwalk. Stadiums for professional teams and leagues are great for team owners and the health and welfare of the small number of athletes who play in the stadiums, but do little more than encourage the sedentary lifestyle and junk food binging that contribute to the city’s epidemics of obesity and diabetes.

Still, compared to the monster Shea and Yankee Stadiums, Keyspan Park has opened the door to a different kind of professional sports. Much smaller than the baseball behemoths, Keyspan is only a stone’s throw from the boardwalk and beach, and the Abe Stark skating rink, and within walking distance of the amusement park. With affordable ticket prices and easy access via mass transit, it attracts families with limited recreational options in their neighborhoods and works as part of a daily outing. On the other hand, Shea and Yankee Stadiums function as enclosed enclaves, attracting a large fan base that drives, and they funnel people in and out as quickly as possible.

And why not put the arena for the Nets basketball team in Coney Island, as planner Simon Bertrang proposes? Two previous studies recommended Coney Island as a location for a professional arena, and until recently that view was held by Brooklyn’s political establishment. Wouldn’t the 18,000 seat arena that the basketball team’s owner, Forest City Ratner, now proposes to cram in between the Prospect Heights and Fort Greene neighborhoods make more sense nested in Coney Island’s amusement area?

If this was to happen – which is admittedly unlikely -- a Coney Island arena should not go the way of the New York Aquarium, which is isolated from the amusement park. Nor should it be dropped in next to Keyspan Park, thereby creating a big enclave of professional facilities. But if properly designed, the home court for the Nets could be physically integrated with Coney Island’s recreational facilities.

The City’s Role

The heart of Coney’s surviving amusement area, Astroland Amusement Park, closed for the season on September 9. The owner of the land, Thor Equities, may very well decide not to renew Astroland’s lease for next year’s season, although a petition campaign is underway to prevent this from happening.

Lacking the kind of public or private commitment given to the Cyclone and B&B Carousel, no amusement park can survive and keep prices affordable to average New Yorkers. Thor wants public subsidies to support any amusements it puts on the site.

In light of this, it is hard to imagine any steps at Coney Island going forward until the administration takes a more direct role in development. In the past, however, the city has tended to rely more on rezoning than direct intervention. Zoning leaves the door open for development but can’t substitute for complex planning with a strong dose of preservation, community engagement and attention to detail.

For a number of reasons, Coney Island cries out for an active city role. If we look to the year 2030 and beyond, Coney Island will probably be one of the most vulnerable areas to rising sea levels. While Coney’s 60,000 residents may be willing to risk flooding and evacuation, it certainly makes no sense to encourage more permanent housing there. Millions of dollars in public subsidies already go to maintain Coney Island’s beach and protect it from erosion. When will the cost of such efforts exceed the public benefit?

Beyond this, a strong public role is imperative if Coney Island is to remain affordable to New Yorkers, both as a place to live and a place to play. Today the park and recreation areas are a boon for New Yorkers with limited incomes and for Brooklynites. Preserving affordability on what was once known as America’s playground is as important as saving the Cyclone and is consistent with PlaNYC2030’s aim of preserving affordable housing.

See: Coney Island’s Summer of Reckoning and With Pizza, Pinball and Panache, Boardwalk Vendors Face Changes

Â

New Bills: Curbing to Cutting Trees

After approving the biggest rezoning plan in the city’s history at its stated meeting on September 10, several City Council members introduced legislation to take care of smaller, quality of life issues, such as regulating curb cuts, air conditioners and trees on construction sites.

Curbing Extra Curbing

Since 2004, Councilmember Vincent Gentile has introduced legislation twice calling for the restoration of curbs that have been illegally cut - which eliminate parking spots and allow cars to enter driveways - as well as for the notification of community boards when a construction project plans to propose one. Each time the legislation has stalled in the council’s transportation committee.

But he is trying again. Gentile, who represents Bay Ridge, often sees parking spots whither away as curb space is taken over by extra large driveways for particular residences, said his spokesman Eric Kuo. Under legislation introduced with Councilmember Domenic Recchia at the council’s stated meeting on September 10, (Intro 619), applications for curb cut permits to the Department of Buildings would have to be examined and forwarded to community boards for review.

" When someone does an illegal curb cut that takes away another parking space," said Kuo. "The intent is to get rid of illegal curb cuts. It's already been a big problem in our neighborhoods in Bay Ridge."

In companion legislation introduced by Gentile and Recchia, (Intro 620) residents could be fined for illegal curb cuts on their property. When illegal curb cuts are found, according to the bill, the Department of Transportation would require property owners to restore the curb or cover the cost for the department to do so. Kuo could not estimate how much the fines for such restoration would be.

According to the legislation, it is unclear how the transportation department would be notified of illegal curb cuts or how the restoration would be enforced. Kuo said they would work with the community and the council's transportation committee staff to work out the details.

Conditions for Air Conditioners

When residents of her Upper West Side district were reportedly ticketed for not using brackets to support air conditioners, Councilmember Gale Brewer introduced legislation that would clarify when brackets would be necessary.

The bill (Intro 618) requires brackets be installed when air conditioners cannot otherwise be safely attached to building facades. Because of new technology and updated units, brackets are often unnecessary.

Trees At Construction Sites

Councilmember Michael McMahon also introduced legislation (Intro 621) that mandates that trees larger than a six-inch diameter be protected during construction. When construction occurs on any building, curb, sidewalk or roadway a protective guard would have to be erected around the tree, under the new bill.

Â

Electricity, Gas and Broadband

Should broadband access join water, gas and electricity and be a basic utility available to all New Yorkers? Some advocates say yes and are likely to press that point as the New York City Broadband Advisory Committee continues to conduct hearings throughout the city.

The Broadband Advisory Committee, created by Local Law 126, exists to advise the mayor and City Council speaker “on issues pertaining to access to broadband technologies within the city of New York.” Broadband, as defined by that law is a “high-speed connection to the Internet” that enables the “fast relay of voice and data that many have come to expect.” Broadband capabilities are essential to many online activities, such as sharing videos, and make many other on-line tasks easier and quicker.

After holding hearings in all five boroughs, the advisory committee will issue recommendations on broadband policy to Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Telecommunications Policy Advisory Group.

The Broadband Advisory Committee has 15 members, eight appointed by Bloomberg and seven appointed by City Council Speaker Christine Quinn. In the main, the mayoral appointees are focused on how to implement telecommunications policies that will enhance the city’s economic competitiveness, while the council appointees have a stronger interest in reducing the “digital divide” between people who can afford broadband access and those who cannot.

A DEMAND FOR BROADBAND

The concern for easier and more affordable broadband access figured prominently in the most recent hearing, held in Brooklyn in late May. Senior citizens spoke of facing discrimination and isolation because they did not have strong computer skills. High school students explained about how high-speed Internet access could assist with their studies. And library administrator Steven Schecter described how people sit outside the walls of Brooklyn central library on Grand Army Plaza to enjoy the free wireless signal during hours when the library is not open. (Wireless is the most practical form of broadband access for outdoor spaces at this time.) Many people bemoaned the paucity of broadband access in various neighborhoods, as well as the high cost of the service that is available.

(Appropriately enough for a hearing about broadband access, most of the speaker presentations are available on YouTube – and would be painful to watch the clips on a dial-up connection. Carlos Pareja of Brooklyn Community Access TV produced a montage of testimony about how enhanced broadband access would benefit senior citizens who wish to re-enter the job market or keep in touch with their grandchildren. Clips of the day’s events are available on the advisory committee’s blog, along with transcripts of spoken testimony. Finally, an audio file of the entire three- hour hearing is available.)

At the hearings, according to coverage on the Empire Zone blog, many who spoke faulted the cost and quality of broadband service now available.

COMMITTEE MEMBERS RESPOND

In comments after the hearing, several members of the Broadband Advisory Committee commented on the necessity of good, quick Internet access, but with different degrees of intensity.

Shaun Belle, president and CEO of the Mount Hope Housing Company and chair of the advisory committee, said it “would be in the best interest of NYC as a whole to develop a comprehensive approach to developing at a minimum a broadband infrastructure for public consumption.” In Belle’s view, broadband should be “a public utility of sorts.” But he said , recognizing it as such would require the city to invest in “private partnerships and infrastructure.”

“The city has a responsibility to intercede and in effect declare the Internet is a â€Public Good’ and guarantee delivery of low cost broadband access to everyone,” said Andrew Rasiej, the founder of the Personal Democracy Forum and an unsuccessful candidate for public advocate in 2005.

To provide this service, he said, the city should build a ‒wireless mesh network’’ over the entire city that would avoid copper or cable hardwire delivery and accelerate access. Radically enhancing wireless access was the centerpiece of Rasiej’s campaign for public advocate.

Matthew Eisner, a Brooklyn writer who testified at the May hearing would go even further. “Why not just supply all New Yorkers with free, wireless Internet access?” he reportedly said. Explaining that he pays $60 a month for what he described as poor service, Eisner continued, “We’re a progressive city — why can’t we just have the city provide us with good, free wireless Internet service? I can’t think of a greater democratizing force than putting high-speed Internet service in the hands of all New Yorkers, not just those who can afford it.”

Failing to improve Internet access could have economic ramifications, Steven Masur, lawyer for start-up businesses, told the hearing. “If we in New York want to be competitive with places like the Silicon Valley, Mumbai or Shanghai, we need cheap widespread broadband access,” he warned the committee

But what does the administration plan to do? Wendy Lader, vice president of telecommunications policy at the Web New York City Economic Development Corporation, which includes the Telecommunications Policy Advisory Group, wrote, “The Bloomberg administration is committed to promoting innovative broadband solutions to support businesses and residents throughout neighborhoods in all five boroughs.” Ladet also said the corporation has commissioned a study on the current state of broadband in New York City and what steps the city might “take to ensure all New Yorkers have access to robust broadband services.”

In her comments, Lader did not explicitly make the “public good” arguments put forth by Belle and Rasiej. This difference of perspective could make for fascinating debate among advisory committee members but could also hinder their ability to provide clear, unanimous recommendations to the mayor and the City Council.

AN UNCHARTED PATH

But even if the committee agrees that the city must have universal, inexpensive – if not free — broadband access, New York would still face substantial challenges. No American city has yet developed a comprehensive policy for enhancing broadband access. In municipal government terms, this is still very new territory.

Philadelphia and San Francisco have both announced ambitious plans to enhance wireless access in each city. (This is analogous, but not identical to, increasing broadband access.) Advocates for enhanced municipal wireless access often hail these efforts. But nothing comes easily.

San Francisco reached an agreement under which EarthLink would build a citywide wireless network and Google would provide free basic Internet service. Mayor Gavin Newsom termed it “the best proposal of its kind in the United States.” But last month the city’s Board of Supervisors voted to delay action on the plan. Some critics expressed concern that the system could be used to store private information on individuals and charged that the free service might not be exactly free after all.

Philadelphia, which could have “America's biggest citywide wifi network,” would make Internet access available to low-income residents for $9.95 a month. But some Comments Potential users have objected, arguing the service should be entirely free.

In New York City, a robust dialogue about the future of broadband access is underway, accelerated by the committee hearings. But no meaningful policy action will occur until policymakers decide whether broadband is a utility or a luxury.

Â

Latest Round in the Garbage Wars

Protesters charged Manhattan "dumps on" poorer neighborhoods in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

Raising signs calling for "environmental justice" and shouting "NIMBY no, justice yes," residents of the Bronx and Brooklyn circled the office of State Assemblymember Deborah Glick last week.

The protestors, members of the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods said they are tired of getting dumped on, quite literally, and want the state to clear the way for a recycling station in downtown Manhattan.

The station is intended to ease the burden on the Bronx and Brooklyn, which now take most of the city's trash, and is part of an effort to make the city's solid waste management system fairer and more environmentally friendly. But in the latest development in the city's garbage wars, several Manhattan Assembly members and parks groups want to block the station. Glick, whose district abuts the site, and others said the peninsula simply is not a good place for the recycling station largely because it would impinge on Hudson River Park. Their critics, however, have accused of NIMBYism (not in my backyard) sentiments.

"It's Manhattan using its privilege," said Elizabeth Yeampierre , chair of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and executive director of UPROSE, a Latino community group based in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. "We want to let Glick know she is in the way. She is in the way of borough equity."

As the hours in the current state legislative session dwindle, some organizations and politicians still hope to get this final piece of the Solid Waste Management Plan approved in Albany. Although the City Council approved the plan last summer -- a decision mired in years of debate -- the state must still vote to allow construction of the recycling facility and education center on the Gansevoort peninsula in the Hudson River near 14th Street.

The Latest Chapter

The history of disposing waste in New York City is wrought with controversy. For five decades, all residential waste (now estimated at 12,000 tons per day) was taken to Staten Island. After former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani closed Fresh Kills in 2001, city officials scrambled to deal with the 50,000 tons of waste and recyclables collected each day. Meanwhile, most trash has been trucked through communities in the Bronx and Brooklyn where it is transferred to larger trucks that transport it to landfills, many out of state.

A 2004 report by a national environmental group concluded that 80 percent of the city's trash collected at private waste transfer stations piled up in just four of the city's 59 community board districts. All were outside of Manhattan, even though that borough creates 40 percent of the city's waste. As garbage trucks tore down city streets in the Bronx and Brooklyn, asthma rates in adjacent neighborhoods skyrocketed, an increase many link to the garbage trucks.

The plan proposed by Bloomberg and approved by council last year aims to shift the hauling of waste from trucks to barges and rails. It also would require every borough take care of its "fair share" of waste.

Under the plan, the city's waste would still end up in far-flung -- and costly -- landfills. But, according to city officials, the plan would eliminate 5.6 million truck miles annually and reduce the city's carbon emissions as well. The Gansevoort facility alone, they said, would reduce truck trips by 30,000 miles annually.

Although City Council passed the entire waste management plan last year, it has not yet been implemented. Some of the marine transfer stations are under construction, while others are being designed, said chair of the City Council's Sanitation and Solid Waste Management Committee Michael McMahon.

The Latest Hurdle

Some opponents of the Gansevoort facility want the recycling station moved to Pier 76, pictured here.

The state government also has approved the entire plan. But because the Gansevoort facility will be within Hudson River Park, it requires a second OK from the governor and legislature. The site is part of a five-mile stretch of open space running from Battery Place to West 59th Street. Opponents of the transfer station said its location would compromise the park, no matter how small the recycling facility may be.

Washington Heights Assemblymember Adriano Espaillat has introduced legislation that would allow the station to be built. He said he is optimistic that the legislature will consider the bill before the conclusion of its session this week. "There is never a perfect place and communities never really welcome this type of initiative," Espaillat said. "Many neighborhoods in the city have been relegated as dumping grounds. We must change that paradigm."

Bloomberg is pressuring Albany to pass Espaillat's legislation. In a letter sent to every member of the state legislature last week, the mayor stated it is "more than reasonable" to open the recycling station, which will take up two-thirds of an acre in a 550-acre park. Bloomberg also argues that the Department of Sanitation studied other sites for the marine transfer station, including those being proposed by opponents, and none were suitable.

Pier 76 especially, the letter states, is "ill-suited" for public use because roads and ramps would create narrow park spaces that would bring about safety concerns. Its proximity to the Lincoln Tunnel would also complicate the site's access.

The reactivation of the recycling marine transfer site at Gansevoort - where a station had operated until 1991 - would free up space currently taken up by recyclable materials at another waste transfer station on 59th Street. That, in turn, could further relieve pressure on the transfer stations in the Bronx and Brooklyn.

In particular, though, supporters of the solid waste plan fear any change in it -- such as moving the recycling facility from Gansevoort -- could derail the waste management plan, allowing trash to continue to pile up in less affluent communities outside of Manhattan.

"That part of the plan cannot go forward and you will have a domino effect," McMahon said.

In an attempt to protect the waste management plan, the City Council endorsed the reactivation of the Gansevoort station by a vote of 48 to 3 last week and urged the legislature to approve the bill. Those voting against the measure were Councilmembers Gale Brewer, Daniel Garodnick and Jessica Lappin, all of which are from Manhattan.

The plan's supporters also want the legislature to act before the end of the session, claiming the issue could be placed on a back burner and ultimately jeopardize the entire plan. "If it's not passed now... it's potentially a really missed opportunity," said Gavin Kearney, an attorney with New York Lawyers For The Public Interest, which works with the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods. "The push that we're getting from opponents to study alternative sites could really kill it."

Parks Versus the Plan

Opponents of the facility, including Friends of Hudson River Park, the Coalition to Protect Our Parks and Manhattan assembly members, Glick, Richard Gottfried and Linda Rosenthal, said the Gansevoort site poses an array of problems.

In a statement, Glick said, "It is unacceptable for the mayor to tout his environmental vision for the future, while his administration is seeking to dramatically reduce critical parkland in one of the most park-starved communities in the city."

Matthew Washington, the deputy director of the Friends of Hudson River Park, said the station could be built on other sites on the West Side -- areas that would not threaten parkland. A study by the groups supports a combined transfer facility at Pier 76 near 36th Street. The pier, the current site of the Manhattan tow pound, is more than twice the square footage of the Gansevoort and 59th Street sites combined, according to the study.

Park advocates have said their opposition is not a case of NIMBYism. "We think it's important for each borough to handle its own waste," Washington said. But, he added, "One of the things that's important to us is not alienating parkland."

Â

Name that Street

|

Hundreds turned out to celebrate last July as a portion of Church |

Update: On May 30, a sharply split City Council defeated an amendment that would have had the effect of renaming part of a Brooklyn street for Sonny Carson. For more, click here.

Millions of people in New York City walk, jog and stumble across streets named for the famous and the not so famous. New Yorkers can explore Columbus Avenue, jam on Bob Marley Boulevard, or be cool on Humphrey Bogart Place, but they can also stand and snicker at the corner of Seaman (named for a 17th-century landowning family) and Cumming (so dubbed in 1925 in honor of a now obscure local property owner).

Whether honoring celebrities or obscurities, street namings are generally quiet affairs with the City Council essentially rubber stamping the recommendations of the community boards. But the dispute over a four-block section of an avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant Brooklyn has renewed focus on the naming and renaming of city streets. On Wednesday, City Council will vote on a bill to rename 51 city streets in honor of various personages. The bill is controversial because of a name that is not in it - that of the late black activist Sonny Carson, hailed as a community hero by some and condemned as a bigot and criminal by others. A sharply divided council committee voted to delete Carson from the package last month. This debate follows another naming controversy - that one involving Corbin Place in Brooklyn, which got its name from Austin Corbin, a longtime Brooklyn developer and an anti Semite.

The council's predilection for devoting energy to street names most people will never use (Avenue of the Americas, for one) is often mocked as a waste of time, but in taking such action the council and by extension, the city has the power not only to bestow honors but also rewrite history. This raises the question of who gets to tell that history and determine who is a local hero - or a local villain. "Street names function as a barometer of social values at a given time, and as such have historical significance that goes beyond a name," wrote Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss, authors of Brooklyn by Name: How the Neighborhoods, Streets, Parks, Bridges and More Got Their Names.

THE POWER TO NAME

|

From Corbin, the anti-Semite, to Corbin, the Revolutionary War hero? |

As the City Council seeks to establish itself as a serious legislative body, its penchant for renaming streets has become an easy target. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, Councilmember James Oddo of Staten Island said the ceremonial gesture was a "luxury the city can no longer afford." Turning away from that task, he wrote at the time, "would symbolize a tangible step in redefining our role." In 2002, Oddo proposed a bill to take the council "out of the name changing game" by leaving the approval of the street renamings to community boards and allowing the council to override any ones it objects to.

The council did not go that far but rather than vote on all the name changes individually, since 2002,it has voted on street naming proposals in two package bills a year.

At the same time, the number of name changes has increased. In 1986, the parks committee evaluated just 25 proposals over the entire year. After 9/11 the number of street names began rising as the council started honoring rescue personnel and others who died in the attack. Last spring, for example, the City Council renamed 58 streets in the city, many for people who died in the terrorist attacks.

HOW IT'S DONE

|

|

Proposals for street renamings begin at the neighborhood level when local residents recommend a street name, usually in honor of a deceased neighborhood figure, to the local community board. Sometime they circulate petitions to demonstrate support.

The community board then approves or rejects the plan. Some community boards are reluctant to rename streets. When "Jerry Orbach Way" failed to pass Manhattan Community Board 5, Orbach's widow Elaine brought the proposal to neighboring Community Board 4, which approved the recommendation to rename the other corner of 53rd Street and 8th Avenue after the actor. Some community boards like to dole out the honors, as chairman of Manhattan Community Board 6's transportation committee Lou Seperky has noted: "There used to be a habit that we'd just name something after anyone who sneezed." Community Board 6 will likely recommend Kurt Vonnegut Way for the next package of street name bills.

Whether a struggle or a sneeze, if a community board votes to pass a street renaming proposal, the local council member then brings the recommendation to the Parks and Recreation Committee. If the committee affirms the proposal, the renaming is submitted to the council for a vote in one of the package bills. When and if the council votes yes, a new sign with the honorary name is erected next to the marker with the current, more mundane, label. (The original street names remain on all street maps.) So, for example, a new sign for Vonnegut Way would be added to the existing post overlooking the corner of 48th Street and Second Avenue where the writer used to walk his dog Flour.

THE CARSON CONTROVERSY

While Vonnegut has his detractors, a corner with his name is unlikely to spark the kind of furor that has surrounded the proposal for Sonny Carson Avenue. Since its introduction, the four-block stretch has been a constant topic of council meeting discussion, divided council members and prompted a lawsuit. And it has spurred Oddo to consider reintroducing his 2002 street renaming bill

Sometimes referred to as "The Mayor of Bed-Stuy," Sonny Abubadika Carson, a Korean War veteran, was involved in a variety of local causes in the local black community, such as the Republic of New Afrika, the African Burial Ground project, securing voting rights for ex-prisoners, the Black Men's Movement Against Crack and protests against police brutality. Additionally, his autobiography was turned into a movie The Education of Sonny Carson.

Recommended by the local community board and submitted for consideration by Councilmember Albert Vann, Carson would seem to be shoo in for an honorary street name. But Carson also had a record of criminal and racially motivated activities. In 1974, he served time in prison for kidnapping. He organized boycotts of Korean groceries where the protestors held up signs saying, "Don't Buy From Koreans" and "Don't Shop With People Who Don't Look Like Us." Carson said at the time, "In the future, there'll be funerals, not boycotts."

The activist made little secret of his attitudes. When asked about his anti-Semitic statements, for example, Carson replied, "I'm anti-white. Don't just limit me to a little group of people." And in a 1987 interview with the New York Times, Carson said, "You don't give us any justice, then there ain't going to be no peace. We're going to use whatever means necessary to make sure that everyone is disrupted in their normal life."

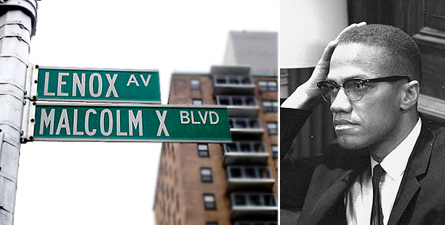

A stretch of Sixth Avenue north of 110th Street was renamed Lenox Avenue in 1887 after millionaire philanthropist and book collector James Lenox. In the late 1980s, the street got another name change to recognize Malcolm X.

But those backing the renaming say it is up to people in the community, in this case Bedford-Stuyvesant, to determine who they can honor. Explaining Carson's significance, Vann said, "He came into prominence at a time when the black community was asserting itself, defining itself, claiming itself and trying to make the community better for black people - he was a part of that struggle."

When it came time for the parks committee to vote, it split along racial lines with three white members -- Alan Gerson, Joseph Addabbo and Dennis Gallagher - voting to delete Carson's name. Chairwoman Helen Foster, who is black, voted against its removal, and another black member, Letitia James, abstained.

At a council meeting following that vote, Councilmember Charles Barron criticized the council for voting to "block the black community from self-determination of selecting our own heroes." He asked, "What could be more divisive, whether intentional or unintentional, than have four white members of this city council tell an entire black community no?"

Vann, who like Barron is black, also voiced concerns about the council setting a precedent for overriding local interests. "We can vote as a council against my district and against my community and against our self-determination," he said. Vann apparently takes a fairly broad view of that right. During a television appearance on NY1, he responded to a hypothetical inquiry about a German community wanting to name a street after Adolph Hitler. "I don't think they could withstand the pressure of doing that, ok? Do they have the right to offer that up? Yes, they do," Vann said. "If you could live with that identification, then I don't have a problem with the process."

Two members of the local Brooklyn community board sued the city council for removing Carson's name from consideration. Presiding Judge Leland DeGrasse rejected the claim, ruling that because the renaming of streets is a legislative matter rightfully under the purview of the city council.

AND WHAT ABOUT ALL THOSE OTHER STREETS?

During the heated debate, Barron said that, if the council failed to honor Carson, he would demand information on every person recommended for an honorary street name in the future. "We got street names of slave holders and racists all over Brooklyn," Barron reportedly said. Whether or not the council agrees with Barron's other comments, the frequency of streets named for slaveholders is indisputable.

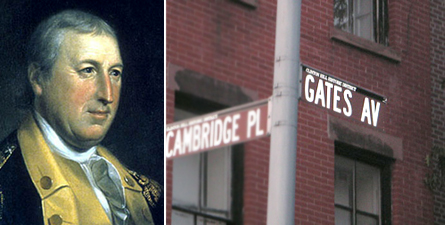

By one count, at least 70 New York City streets has slave owner names Takes Gates Avenue, the very name once slated to bear Carson's moniker. Its name honors Horatio Gates, a Revolutionary War general. For part of his adult life, Gates owned a Virginia plantation and slaves, although he freed them in 1790.

An influential historical figure and "founding father" of America, Thomas Jefferson is honored with a park and a high school (ironically in Barron's largely black). But as Barron pointed out at a recent council meeting, Jefferson could also be described as a slaveowner, rapist and pedophile. Foster added that Jefferson sold his own children into slavery.

Horatio Gates, a Revolutionary War general, whose name now graces what some would dub Sonny Carson Avenue, owned slaves who he eventually freed.

Of course, not only slaveowners are controversial. In 2003, the city renamed the corner of the Bowery and 2nd Street as "Joey Ramone Place," in memory of the Ramones singer. He got this honor despite having spent a number of years with a fairly major cocaine habit

The New York City Council has recognized the socialist and anti-imperialist activist and poet Pedro Pietri by renaming East Third Street between Avenues B and C in his honor. The council was apparently not alarmed that Pietri founded the Young Lords Party, which in the 1970s was often likened to the Black Panther Party

And Barron has criticized the council's accolades for the entertainer Al Jolson, who performed in blackface. New School Professor Joseph Ciolino, who has studied Jolson, has said the entertainer stood up for equality both on and off Broadway, and wore blackface for cosmetic effect. True or not, many New Yorkers still might not be amused.

And then there was the Bernard Kerik Correctional Center. In December 2001, while Kerik, a former city corrections commissioner, still served as police commission, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani agreed to rename the Manhattan House of Detention, popularly known as the Tombs, in Kerik's honor. Less than five years later, after Kerik had pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges, had been accused of seamy --if not illegal conduct -- and was still the subject of sundry other investigations, Mayor Michael Bloomberg removed his name from the jail.

The names of anti-Semites grace several street signs as well. Take Corbin Place, for example. Austin Corbin, a onetime president of the Long Island Rail Road, was also a member of the American Society for the Suppression of Jews who once asked, "If this is a free country, why can't we be free of the Jews?" Today, a thriving Jewish community resides on the street named after him, which some rabbis consider to be the best revenge. Others disagree and want the city to rededicate the street to another famous Corbin: Margaret Corbin, a Revolutionary War heroine. This way, the council can revise history without forcing residents to change their addresses.

But another anti-Semite is likely to keep his streets. New Amsterdam Governor Peter Stuyvesant, who tried to get the first Jewish settlers in America, expelled has his name attached to a large avenue, an apartment complex, a post office, a high school and other New York fixtures.

STREETS THAT FAILED

If Carson does not get his street, he will have company. A 1986 proposal to rename a street in honor of Ben Gurion, the first president of Israel, failed when representatives of the American-Arab Relations Committee and the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee testified against the recommendation, citing considerations for Palestine's independence and safety.

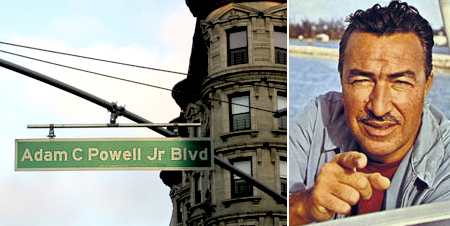

During his life, U.S. Representative Adam Clayton Powell attracted controversy but there was little opposition to putting his name on a portion of Seventh Avenue in his old congressional district.

Councilmember David Weprin withdrew a proposal to rename a street after assassinated Israeli tourism minister Rehavam Zeevi when he learned of Zeevi's hatred of Palestinians

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn has rejected efforts by activists to rename a Harlem street for Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has been on death row in Pennsylvania since being convicted of murdering a police officer in 1981. "Commemorative street renamings are generally awarded only posthumously. To the best of my knowledge, Mumia Abu Jamal is still alive, and is therefore not eligible to have a street renamed after him," she reportedly wrote one advocate.

Not bound by such considerations, in 2006, the Paris suburb of St. Denis France named one of its streets for Abu-Jamal. The U.S. Congress then passed a resolution asking the French government to remove the sign, thereby proving members of the New York City Council are not the only Americans to make a big deal of street names.

Â

Debating a Greener Future

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plan for a larger but more environmentally friendly New York City continues to attract praise and criticism. And already the plan is makings its mark.

In the days since the Earth Day speech, Bloomberg announced an executive budget that took some very early steps toward financing his grand vision. (See related story.) He revealed a plan for a largely industrial area near Shea Stadium, which he said exemplified green principle. Others disagreed. (See related story.) And the building department announced a long awaited revision of the building code that, among other things, would encourage environmental sound construction.

This week we offer more commentary and analysis of Bloomberg's vision to create an environmentally sustainable city heading toward the middle of the 21st century. Last week, our Sustainability Watch focused on the plan as a whole, but this week we look at specific parts of the proposal -- from its plans to clean up contaminated areas to how the bills will be paid. (For a guide to articles by topic area -- transportation, energy, land and water, money and jobs -- see below.)

Sustainability Watch, a joint project of Gotham Gazette and the Hunter College Center for Community Planning & Development, will try to keep alive the debates about what's good and not, look at what's missing, discuss how the plan is working and monitor the gaps between plan and practice. As part of this, we continue to urge you to comment on these articles and the mayor's plan through our message boards (attached to every article) or by emailing us at info at GothamGazette.com.

Transportation

The Outlook for Congestion Pricing

The Outlook for Congestion Pricing

By Bruce Schaller

Schaller Consulting

Officials from the outer boroughs and the suburbs have rushed to condemn the fee, but as the debate continues, the political calculations could change.

A Fee to Level the Playing Field

By Brian Ketcham

Traffic engineer

Motorists cost the rest of us billions of dollars a year. Congestion pricing aims to correct that.

Paying to Drive and to Park

By Paul Steely White

Executive director, Transportation Alternatives

Faced with likely opposition to his laudable plans for congestion pricing, Mayor Michael Bloomberg should also try to raise the cost of parking.

Improve Transit, Then Charge to Drive

By Hope Cohen

Deputy director, Center for Rethinking Development

Political and technological issues could stall congestion pricing, but there are many transit improvements the mayor can make in the meantime.