How the City Has Reduced Soot

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation recently predicted that the downstate region of New York State (including all of the city, plus Long Island and the lower Hudson Valley) soon will meet the federal annual health standard for soot (a.k.a. fine particulate matter), for the first time ever.

This prediction came in the department's draft plan, released last month. It is good news for anybody who breathes - and it's worth understanding what is working and what isn't.

Why "Particulate Matter" Matters

Public health experts agree that this kind of soot pollution is one of the most dangerous forms of air pollution. In the U.S., tens of thousands of premature deaths are attributable to soot pollution annually. Roughly 4,000 such deaths occur in New York City every year.

Soot pollution creates real-world impacts beyond statistical premature deaths. Dozens of studies have shown that soot particles trigger asthma attacks and emergencies, bronchitis, cancer and heart disease. Plus, the black carbon core of many soot particles has been linked to global warming and especially related to melting sea ice in the Arctic. In fact, some scientists believe that this black carbon may be the second most important global warming pollutant after carbon dioxide.

How the System Works

Under the federal Clean Air Act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is required to set "National Ambient Air Quality Standards" for six common, so-called criteria pollutants. Besides particulate matter, these include ground-level ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides and lead. These standards are health standards - in other words, EPA sets the limits based on its best understanding of the effects of pollution on human health and environmental welfare. To arrive at this, the agency uses scientific criteria and periodically reviews the most up-to-date literature. EPA does not look at technical feasibility or costs in setting these standards (those only come into play when the states devise strategies to meet the standards).

Once EPA sets its standards, states have to monitor their air quality. If an area fails to meet the standard, the EPA designates it is as a "nonattainment area," which triggers a legally enforceable obligation for the state to create a plan to reduce the pollution on a set timetable. If a state ignores this obligation, it risks losing the right to control its own pollution and could face extra pollution hurdles for any new industry. In extreme cases, a state could even lose its federal highway funding.

In 1997, EPA set its most recent standards for annual and daily exposure to fine particulate soot. These standards limit our exposure to particles that are no larger than 2.5 microns in diameter. To get a sense of how small these particles are, about 70 of them could stretch across the width of a single human hair. The particles are so small that they can easily evade the defense mechanisms of our noses and throats, and lodge in the deepest depths of our lungs.

How is NYC Meeting the Standard?

The Clean Air Act allows states to figure out the best, most cost-effective ways to cut pollution in their own air. Strategies that work best in Houston or Los Angeles may not work well in New York or may not be the cheapest way to achieve the desired pollution reductions.

Here in New York, diesel pollution lies at the heart of our soot problem. Back in 1995, the state Department of Environmental Conservation identified diesel engines as the source of more than half of the particulate soot pollution breathed by New Yorkers on the sidewalks of Madison Avenue. This led to a broad campaign to clean up the buses in New York, and for the EPA to adopt cleaner federal standards for new diesel engines.

In 1998, EPA adopted new standards that would cut diesel pollution from new engines by 40 percent, starting in 2004. (Thanks to a consent decree in litigation against the nation's engine makers, these cleaner engines hit the market in October 2002.) By 2000, the state agreed to clean up the Metropolitan Transportation Authority buses, with a comprehensive program to use a cleaner, ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel; retire the oldest buses and replace them with the cleanest, new buses available; and to retrofit the remaining buses with advanced soot-busting filters.

The clean-up of the MTA New York City Transit fleet has been a smashing success. Today, the fleet emits 97 percent less particulate soot pollution than it did in 1995, when the Natural Resources Defense Council ran ads on the buses that read "Standing behind this bus could be more dangerous than standing in front of it." The fleet's early commitment to hybrid-electric buses was a smart bet against higher fuel prices that pays off with every mile. And, the fleet's clean-up program serves as a model for large city fleets around the globe.

The MTA program also helped lay the technical and political foundation for the national cleanup of diesel trucks and buses. EPA adopted new pollution standards for trucks and buses in 2001 that, in effect, nationalized the fuel and emissions goals of the MTA program: ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel for all buses and trucks, plus at least 90 percent emission reductions from all new engines.

The New York State draft plan for particulate matter shows that these programs to reduce diesel pollution are working. Since 2002, diesel soot emissions have been cut by 54 percent.

In contrast, the state's data show clearly that pollution from other sources has not decreased. "Point" sources (large facilities like refineries or power plants) and "area" sources (smaller sources that collectively add up to a lot of pollution citywide, like heating units in residential buildings) have actually gone up by almost 12 and 8 percent, respectively.

In other words, thanks to cleaner diesels, New York is on the path to cleaner, safer air.

New Yorkers cannot breathe easily yet. We still fail to meet the EPA standard for ground-level ozone (smog), which is highest in summer months. A city law that requires contractors to cut pollution from their construction equipment is being widely ignored, and few of the city's school buses use the most advanced soot filters to protect the children riding them. And, when EPA designates nonattainment areas for its daily particulate matter standard late next year, it's likely that New York will have to take further steps to reduce its soot pollution.

But for several years, it's been clear that New York -- and the diesel industry -- have been investing in cleaner diesel fuels and soot-cutting technologies. Now, for the first time, we can see the long-term data trends to confirm this, and the real-world benefits of these investments.

Â

Making Black Cars Green

Now that congestion pricing is behind us (at least for now), attention can turn to other PlaNYC 2030 proposals to lower the carbon footprint of some of the traffic we see every day in our city.

To do that, the Taxi and Limousine Commission recently approved regulations will increase the fuel economy of all new "black cars" that service the city's business community to a minimum of 25 miles-per-gallon (mpg) next year and to a minimum of 30 mpg beginning in 2010.

The proposal to green the city's roughly 10,000 black cars is an obvious follow-up to last year's regulation that is, slowly but surely, converting the city's yellow cabs to fuel-efficient hybrids, thanks to Local Law 72 of 2005.

Switching to more fuel-efficient models (whether hybrid or not) cuts fuel costs for drivers and operators, while reducing the global warming impacts of the overall industry.

Though this new regulation is well intentioned, it may not provide as much global warming as possible.

The Myth of MPG

Here's why: the use of "mpg" ratings (set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for all cars sold in the U.S.) as the performance indicator is an imperfect way to measure the global warming impact of these vehicles. It's imperfect for two reasons.

First, the agency's mpg ratings are flawed because they are based on the agency's assumptions regarding the typical style of driving in cities and on highways across the nation. These assumptions bear no relationship to the way black cars are actually driven in New York City. To put it as simply as possible, EPA assumes cars drive faster, sit in less traffic, idle less, and use less air-conditioning than any city black car.

Second, mpg ratings are imperfect because there are significant, so-called "upstream" global warming emissions that stem from the manufacturing and transport of the vehicles to New York, as well as from the production, refining, processing and/or transport of whatever fuel is used (i.e., gasoline, diesel, biofuels, or alternative fuels such as natural gas or electric power). The agency's ratings govern only the amount of fuel that one can expect to use in typical city or highway driving, not the actual global warming pollution that comes from the driving (and the production) of the car.

A Footprint Approach

A more comprehensive approach would be to measure the full, life-cycle "carbon footprint" of the vehicles. Such an approach would ensure that the city is driving the black car industry towards the vehicles that provide the least amount of global warming pollution.

Of course, requiring car fleets to calculate their carbon footprint is a bit harder than simply reading the EPA mpg ratings. So, a practical solution would be to give fleets a choice: fleets could choose to comply with the regulation simply by using vehicles that meet the mpg threshold —- or they could use vehicles that provide, on a life-cycle basis, an equivalent or better carbon footprint. Providing this option would open the door to alternative fuel vehicles that may have very low upstream emissions, yet that do not meet the Environmental Protection Agency's mpg threshold of the regulation.

How could this work?

The city could add an alternative compliance mechanism to its newly approved regulations that allows (but does not require) fleets to use a full, life-cycle global warming analysis to demonstrate compliance with the new rule. With such an alternative compliance mechanism in place, a vehicle with low upstream impacts could comply with the rule, even if its mpg rating does not meet the 25 or 30 mpg threshold (or, as in the case of some vehicles that are retrofitted to run on alternative fuels, no EPA mpg rating at all).

Adding such a mechanism would move the city closer to the ground-breaking approach being proposed in California. In that state, regulators are considering a "low-carbon" approach to regulating fuels and vehicles, rather than regulating mpg or biofuels. The city should share California's goal: to encourage the fuels and vehicles that are the lowest in global warming impact on a life-cycle basis, rather than rely on the more-limited view of the miles-per-gallon of the vehicle, the amount of biofuels used, or the emissions at the tailpipe (all of which are used in various PlaNYC 2030 proposals).

Setting Standards

Lawyers reading this may say, "Wait a minute - the City cannot set its own emission standards."

That's right: only the Environmental Protection Agency and California can set emissions standards for vehicles, and other states can choose to follow them (New York tends to follow the more stringent California standards). But the approach summarized above would not run afoul of the federal restrictions on the city's ability to set vehicle emission standards, because it would not be a mandatory requirement on the fleets. Instead, it would simply be an alternative compliance mechanism that could be used by the fleets or not, as they wish. Thus, such a mechanism should comply with the federal restrictions on the city's ability to regulate vehicle emissions.

The Taxi and Limousine Commission deserves support for its plan to improve the environmental performance of the city's black cars.

Like the yellow cabs, these vehicles drive more miles, consume more fuel, and emit more pollution than other cars on city streets. However, the commission can make a strong plan even stronger by amending the final rule to enable fleets to use life-cycle analyses to unlock the potential of lower-carbon vehicles that could provide effective service in the five boroughs.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC switchboard.

Back to the Sustainability Watch homepage

Â

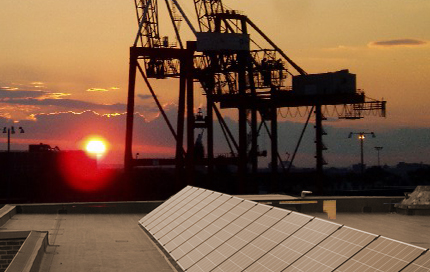

Blocking the Sun: Solar in the City

Looking out at New York Harbor from my window in Red Hook in Brooklyn, I imagine the water rising. Red Hook, before it was developed to handle the needs of a growing port in the 1800s, looked much like the wetlands of Jamaica Bay. It was a series of islands, some of which were below water at high tide. Global warming is a threat to the place, just as it is a threat to many low-lying areas of the city including the entire southern plains of Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg's PlaNYC notes that one way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions could be by moving from fossil fuel to solar energy. New Jersey and Long Island make solar power installation easy. Unfortunately New York does not offer much encouragement to the small homeowner who tries to convert to solar. On the contrary, it requires a permit process for rooftop installation of wind and solar systems that would make the old Soviet Union proud.

That said, living near the water forces you to take global warming seriously. So I set out to do my part by installing solar panels on my house. I imagined a project similar to stringing together a computer or stereo system would make me ready for the solar age and net metering. (Net metering allows daytime solar power to be moved to Con Edison's wires and nighttime power to be drawn from the system.) I was prepared to string a metal-sheathed cable from my roof to my electric meter and then plug a small windmill and solar panel into a DC/AC inverter and transformer. An electrician would then inspect what I did and wire it to my electric meter and I would be set. Total cost, I figured, would be $10,000 to $15,000 and while it would take some time for me to recover my investment, I assumed I would get there before the rising waters flooded my home.

The Rising Tide of Paperwork

What I found was a bureaucratic and featherbedding nightmare that could discourage the most ardent environmentalist. New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), the city Department of Buildings, the Bureau of Electrical Control (whatever that is?), Underwriters Laboratories and Con Edison each have separate applications and work permits. A licensed architect must submit drawings. Three separate inspections of the installation must be made before the switch can be flipped. It has been reported that required approvals can take several years. The additional cost of all this government regulation more than cancels out the substantial tax incentives that government proudly provides in the name of encouraging energy independence.

Richard Klein operates Quixotic Systems, a small business that has installed more than 25 solar systems over the past three years. "Overregulation has brought the cost in New York up to the highest in the nation," Klein told me. "Government does not understand what a small business needs to develop a market or what a home owner can afford." Asked what can be done to make sustainable power work in New York City he quickly answered, "Consolidate permitting, streamline paperwork, have fewer entities involved."

The Energy Audit

For my project, I started with the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. An agency representative at an Energy Smart Fair at Gateway National Recreation Area in Brooklyn told me the most likely way to reduce energy costs was by reducing the use of energy in my home. The state's Energy Research and Development Authority suggested an energy audit by one of their contractors. On the scheduled date of the audit, the contractor placed an airtight exhaust fan in my front doorway and began to measure places in my home where air was entering the building. They gave me good advice about insulation, promoted the Energy Star appliance program and noted places in my home that were not airtight enough. They told me that I had already made the big changes. The stove and furnace had electric pilot lights. The house was 99 percent compact fluorescent. All appliances except the toaster were Energy Star.

They followed up with a multi-page report. It concluded that I should replace three windows and a couple of doors and put down a new roof. Additionally, I should add some blow-in cellulose insulation to one corner of one floor of my home. The contractor's estimate for the work after tax rebates was $15,000. The work was eligible for tax rebates only if I did it with a certified contractor. My utility costs would be reduced by approximately $12 a month after work was completed. I can do the math.

There was no mention of solar or wind power in the report, even though I had mentioned them in my discussions with the contractor. In the end, the agency that should be promoting solar power throughout the state was silent.

Wind on the Roof

If it's so hard to install solar panels, how about wind power? Here in Red Hook the wind blows 24/7 for nine months of the year.

Small-scale windmills are not suitable for most New York City rooftops, but they also are discouraged by regulation. Installations of small rooftop windmills, even those that can be placed on a pole no more intrusive than a TV antenna, require the same permitting process that is needed to add a new floor to a building. There should be a way to develop a set of rules that says "yes, but" rather than "no, except."

There is much to look forward to in PlaNYC. New buildings will be constructed to be more energy efficient. Additional tax incentives will encourage rooftop solar. Green roofs and the use of succulent plants on specially designed roofs to reduce water flows to sewers are encouraged. Energy efficiency is promoted with new incentives. But PlaNYC must address the roadblocks presented by governments and utilities if we ever hope to see a significant move to renewable energy.

Looking down on Red Hook from the highest subway station in New York (the F line at Smith & 9th Streets), the bare black rooftops of the many buildings stretch to the waters' edge. There aren't even clotheslines on those roofs. Does everyone in the city use electricity or gas to dry clothes? PlaNYC says nothing about using rooftops to dry clothes.

Perhaps instead these roofs are the perfect place to build an ark in anticipation of the coming flood. I wonder how many permits are required.

Dave Lutz is the executive director of Neighborhood Open Space Coalition, which works for a healthier, greener city.

Back to the Sustainability Watch homepage

Â

An Unknown Urban Forest

It is often said that parks are the lungs of the city. But just as parks help clean the air and cool the city, so do an often neglected resource: the thousands of privately owned front and back yards of the city's rowhouses and apartment houses. The tools to green the city are right under our noses — and PlaNYC2030 and most of New York City's citizens are missing them.

While Mayor Michael Bloomberg's PlaNYC highlights and relies on the substantive and undeniable environmental benefits of publicly owned open space, privately owned public space is barely even on the city radar screen. As environmental concerns move front and center and urban open spaces are increasingly threatened, these back yards suddenly appear to be a valuable resource that we can no longer afford to disregard.

Environmental Benefits of Open Spaces

A groundbreaking 1996 study conducted by the U.S. Forest Service found that New York City trees remove over 2,000 tons of air pollution a year and store over 1.3 million tons of carbon annually. Think of trees actually cleaning the air, mitigating the pollution from cars and coal burning industries. These trees are the heavyweights of the global and the local environment -— to overlook their value is foolhardy and short-sighted.

Maintaining and planting trees also cools the ambient air during the hot summer months and is an effective mitigation strategy to impact the urban heat island effect -— a term used to convey the fact that urban, asphalt-laden centers can be as much as 10 degrees hotter than their surrounding, greener areas. If trees have the ability to make areas cooler, use of air conditioning is likely to decrease where trees are more abundant.

Other environmental benefits of tree planting and open spaces relate to the fact that permeable surfaces allow rain water to percolate slowly into our water table, instead of flooding our aging water treatment system — of particular concern because when the city's drains are overwhelmed by a quick influx of heavy rains, untreated sewage overflows into our waterways.

It is slowly seeping into our collective urban consciousness that cities cannot look to the Amazon forests only to combat global warming. We too must become ever more active stewards of our environment. Just as more of us are recycling, using compact florescent light bulbs and eschewing plastic bags (slowly!), public discourse should zero in on ways that encourages everyone — tenants, landlords and private property owners — to maximize the environmental benefits of existing open spaces.

New York City Back Yards

While “city backyards” might seem like an oxymoron, our city has a lot of them -- even in Manhattan. Wherever 19th century rowhouses survive —- Harlem, the upper east and west sides, Park Slope, East New York and many other areas -— significant, but hidden open spaces composed of adjoining back yards flourish. On the Upper West Side alone, these rear yards total over 100 acres of open space -— that is about one-eighth the size of the entire Upper West Side and almost 14 percent of the size of Central Park.

If we were to add up all the open spaces in private back and front yards in the entire city, we would find that there are many hundreds of acres of privately owned open spaces that are overlooked by individiduals and city planning and environment officials alike — and we can reason that these back yards have similar environmental benefits as the trees and open spaces in our parks. The lungs of the city are comprised of publicly and privately owned trees and open spaces, but air that is cleansed is shared by us all.

Soon, we might find out just how much these open spaces contribute to the city's climate.

LANDMARK WEST!, an Upper West Side community based preservation advocacy group, is partnering with Columbia University Center for Climate Systems Research and the City University of New York's Institute for Sustainable Cities to analyze the micro-climates in sample rowhouse blocks on the Upper West Side. This project will quantify the environmental benefits of rowhouse back yards. Just as it was important for the city to study publicly owned trees and open spaces before it devised its PlaNYC environmental initiatives, it is important to collect solid scientific data as a foundation on which to develop public policy with regard to privately owned open spaces, to maximize the potential environmental good that these back yards offer the city.

The findings of the LANDMARK WEST! partnership could also determine whether and to what degree these back yards reduce ambient air temperature, alleviating the urban heat island effect, and reduce air pollution, improving air quality. Other useful information, such as measuring permeable surfaces, will be gathered to calculate how much rainwater these backyard surfaces divert from New York City's water treatment system, thus reducing its burden (and associated costs) during peak rains.

PlaNYC Environmental Initiatives

If the city is serious about planting one million trees by 2030, it must also encourage preservation and maintenance of existing trees, be they on private property or public land. City agencies should not approve building permits without considering the environmental effects and all associated costs of demolition, and it should not approve rear yard additions and other building projects that destroy trees or reduce permeable surfaces without considering the associated environmental and economic costs.

Otherwise, the city will spend millions planting street trees in the neighborhood front yards, while trees in backyards are destroyed or die because property owners have not embraced the cultural shift that will be needed to maximize the environmental benefits of these hidden open spaces. A sustained commitment to the principles PlaNYC 2030 and extensive coordination within and between our many city departments and public and private citizens will be critical if the goals are to be realized.

Unfortunately, this coordination and commitment is already coming up short. Even the Parks Department is violating some basic tenets of PlaNYC. According to the New York Times, the department is seeking to cut down 14 trees at Union Square; on Randall's Island, an unspecified number of trees were felled to make way for sports fields and countless trees were also destroyed (some say more than 400) to make way for the new Yankee Stadium. Not only were these trees uprooted and killed, but the newly installed fields are made of synthetic turf, a material which increases temperatures markedly, violating yet another central tenet of PlaNYC. Making the internal PlaNYC contradictions even more apparent, asphalt was installed to replace pavements instead of using permeable pavement surfaces, as forward-thinking urban planners are doing. While there are myriad political impediments to some of the city environmental initiatives, some initiatives involve less money but a lot more coordination, commitment and imagination.

The city must assist community based projects — such as the LANDMARK WEST! Project — to quantify the environmental benefits of trees and open spaces in the city's back yards, to shed light and provide guidance to green these overlooked back areas. Imagine the possibilities if we nurture each little piece of open space we already have. The city will be a healthier —- and a more pleasant -— place to live.

Evan Mason is Special Projects Coordinator at LANDMARK WEST!, a non-profit community group working to preserve the best of the Upper West Side's architectural heritage from 59th to 110th Streets between Central Park West and Riverside Drive.

Back to the Sustainability Watch homepage

Â

Cleaning Up a Creek

On a waterway like Newtown Creek, one of the dirtiest in North America, progress must be measured in decades.

The creek is an open wound in the heart of New York City. Slowly flowing through Queens and Brooklyn before being blended by the tides into the East River, its waters carry oil slicks, floating trash, and billions of gallons of raw sewage in New York Harbor each year. Its shoreline is home to dozens of contaminated sites, decaying waterfront property, and one of the nation's largest underground oil spills. There is no natural space and only a single sliver of a park.

Surrounding neighborhoods—Greenpoint, East Williamsburg, Maspeth, Long Island City—have shouldered the pollution burden for a century. Whether by design or by destiny, Newtown Creek will serve as a test site for the initiatives proposed by Mayor Bloomberg in plaNYC 2030.

Tackling Contamination

One year into plaNYC, the view of Newtown Creek hasn't changed perceptibly. The lack of progress in the field underscores the monumental nature of the challenge. While plaNYC did not address Newtown Creek directly, many of its initiatives, if carried through, would bode well for its restoration. The mayor's initiative presented citywide goals that would speed up the remediation and redevelopment of contaminated sites, create new parks and green spaces and address the problem of raw sewage in the harbor.

On contaminated sites, the mayor proposed eleven initiatives aimed at fast-tracking cleanups, increasing public involvement, and streamlining redevelopment. Newtown Creek has seen progress on the public involvement front. The Greenpoint Manufacturing Design Center, Riverkeeper, and the Newtown Creek Alliance were recently awarded a $625,000 grant from the New York's Department of State for a community-driven brownfields study—an application the city strongly supported. The study will lay out a vision for the creek and leverage money and support for cleanups.

On open space, the mayor proposed seven initiatives aimed at increasing the amount of green cover around the city. In 2007, the city opened the first ever park along the creek—this one at the Newtown Creek sewage plant—and is set to open up a second on the Greenpoint waterfront in 2008.

The Sewage Issue

On the problem of raw sewage, the mayor proposed ten initiatives for improving harbor water quality, yet on this important issue the outlook for Newtown Creek remains clouded. Raw sewage has plagued Newtown Creek -- as it has throughout the harbor -- because of the city's outmoded sewer system, which mixes stormwater from the street with sewage from buildings. A tenth-of-an-inch of rain can overload the system, forcing the combined stream to overflow untreated into the harbor, severely impacting water quality.

The problem disproportionately affects Newtown Creek because it no longer has a natural flushing mechanism. The mayor set a goal to open 90 percent of city's tributaries to human contact by improving treatment systems and expanding green cover across the city in an effort to keep stormwater from ever entering the sewer system. This seemingly ambitious goal, however, would only open harbor tributaries like Newtown Creek, to boaters -- kayakers, swimmers and waders must still beware. A truly ambitious goal of opening up one hundred percent of the harbor to safe human contact would have served as a powerful lever for change, and it would have demonstrated that the city was prepared to hold itself more accountable.

A Cleaner Future

Despite this shortcoming, the future for Newtown Creek looks brighter as a result of plaNYC 2030.

Ten years ago, City Hall shunned talk of environmental sustainability. Today, we have a Mayor with a vision and a forum for public input. The hard work is ahead. The success of the plaNYC initiatives on Newtown Creek as well as other tributaries citywide will depend on public support for a bold environmental agenda and an engaged City Hall and City Council.

In the short-term, the mayor must demonstrate his ability to break down institutional barriers and archaic mindsets that had hastened the decline of the environment. In the long-term, the success of PlaNYC 2030 will depend on the political endurance of the city's future leadership, so that today's momentum is not wasted.

Basil Seggos is the Chief Investigator and Hudson River Program Director at Riverkeeper.

Back to the Sustainability Watch homepage

Â

The Dirty Side of Biodiesel

of greenhouse gases and toxic air emissions.

With oil prices at an all time high, a quagmire in Iraq that more than one pundit has attributed to our massive energy appetite and a general consensus on the threat posed by global warming, dumping fossil fuels in favor of "renewable" ones made from domestically grown crops sounds like a win-win situation. In this light, Councilman James Genarro's bioheat bill, which proposes we add vegetable-based biodiesel to traditional diesel heating oil supplies in New York City, appears to be sound policy. Unfortunately, biodiesel has an oft overlooked dirty side and few of its touted benefits hold up under closer scrutiny.

Bioheat proponents claim that substituting biodiesel for petroleum can curtail oil imports, improve air quality and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In reality, a biodiesel mandate would encourage environmentally destructive farming practices, have no impact on foreign oil consumption, increase greenhouse gas emissions, drive up food prices and devour millions of dollars in taxpayer subsidies.

As for the improved air quality claims, it's a false comparison. The choice is not between biodiesel and New York City's current high sulfur diesel heating oil standards. The choice is between biodiesel and ultra low sulfur diesel -- a new fuel standard that shares a similarly positive air quality profile with biodiesel. To Councilman Gennaro's credit, the better half of his bill supports replacing high sulfur diesel heating oil with ultra low sulfur diesel.

What's at Stake?

A million households and thousands of businesses in New York City consume approximately 500 million gallons of high sulfur diesel heating oil annually. Because the sulfur content of fuels is directly related to emissions of fine particulate matter, heating oil ranks as the largest source of particulate matter in the city. Able to penetrate into the deepest portions of the lungs, this particulate matter contributes to premature death from heart and lung disease, cardiac arrhythmias, heart attacks, asthma attacks and bronchitis.

A recent report released by the energy consulting firm Synapse Energy Economics confirms that by mandating ultra low sulfur diesel heating oil for New York City, we can reduce particulate emissions by more than two-thirds. The report also describes how ultra low sulfur diesel improves furnace efficiency, decreasing fuel consumption and reducing maintenance. That means that by heating our homes with ultra low sulfur diesel we can save money while reducing greenhouse gas and particulate emissions.

Squeezing Renewable Energy from Non-Renewable Resources

Biodiesel can be refined from a wide variety of vegetable oils and animal fats, but in the U.S. subsidies and tariffs make soybean oil the dominant feedstock. Soybeans may be a renewable resource, but America's industrial-scale farms devour and destroy enormous quantities of non-renewable and irreplaceable resources.

Powering the machines that plow, plant, harvest, cast fertilizers, spray pesticides and pump irrigation is energy intensive. The fossil fuels consumed by on-farm operations release significant quantities of greenhouse gases and toxic air emissions.

Adding to soybean agriculture's formidable fossil fuel tally, large amounts of natural gas are needed to produce the nitrogen based fertilizers that promote their growth. These fertilizers break down in fields releasing nitrous oxides -- a global warming agent hundreds of times more potent than carbon dioxide. When these fertilizers leach from farm fields they poison drinking water and ravage marine ecosystems. Run-off from Midwestern farm fields ends up in the Gulf of Mexico where it contributes to a New Jersey-size "dead zone" almost entirely absent of marine life.

Making matters worse, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reports that 91 percent of the U.S. soybean acreage planted in 2007 was genetically engineered to tolerate herbicides, a development that has boosted glyphosate herbicide applications several fold. Glyphosate, a powerful weed killer, is the third most common cause of pesticide illness in farm workers and research indicates that exposure is linked to rare cancers, miscarriages and premature births.

If passed, Genarro's bioheat bill will force New Yorkers to consume approximately 100 million gallons of biodiesel annually by 2013. With an average yield of 58 gallons of biodiesel per acre of soybeans, heating our homes and businesses would require approximately 1.7 million acres of soybeans, which in turn, according to figures garnered from a 1998 Department of Energy report, would require:

Soybeans may be green, but growing them is most certainly not.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Food Prices Rise

The U.S. is on track to produce 3.3 billion gallons of biodiesel in 2009 -- a quantity of fuel that would consume nearly every acre of U.S. soybeans, yet meet only 6 percent of our diesel demand. That 6 percent is not going to secure our energy independence, but it will increase greenhouse gas emissions and raise food prices.

Every acre of food diverted for fuel requires that another acre be planted to grow the missing food, and when land is cleared for cultivation, it releases up to 420 times more carbon than the fossil fuels it displaces. Low-income countries offer cheap land and labor, and tropical crops, such as palm, can yield eight times more oil per acre than soybeans. If we continue to mandate the consumption of biodiesel, we will exhaust domestic soybean acreages, and production will then shift to the tropics. An analysis by the Clean Air Task Force finds Europe's appetite for biodiesel is already registering in Indonesia and Malaysia, where thousands of acres of forest have been cleared to make way for palm oil plantations -- destroying wildlife habitat and releasing millions of tons of greenhouse gases in the process.

Switching land from food to fuel also raises food prices. In the U.S., demand for corn based fuels has contributed to a dramatic spike in the price of corn. This is also pushing up the cost of corn-intensive foods such as dairy, eggs and meat, which is pinching New Yorkers pockets. In Mexico, the high price of corn, which threatens the food security of millions living on less than a dollar a day, has sparked widespread protests.

Our Tax Dollars at Work

Hundreds of government programs have been created to support virtually every stage of production and consumption relating to biodiesel. Everyone from soybean farmers to biodiesel distributors get handouts -- compliments of the taxpayer. According to the Global Subsidies Initiative, every year grants, tax breaks, cheap credit and regulatory mandates funnel hundreds of millions of dollars into promoting biodiesel, doling out around $2 for every gallon consumed.

Yet despite these massive subsidies, biodiesel is still not competitively priced against ultra low sulfur diesel. Or at least it wasn't until the recently passed state budget allotted another handout to agribusiness: the bioheat tax credit. Taxpayers should now be prepared to shell out another 20 cents per gallon to subsidize the biodiesel used to heat homes in the state.

Heating our homes with biodiesel would result in serious consequences for our health and the environment. There is no reason why New Yorkers should bear these costs when an easy solution is at hand.

By simply switching to ultra low sulfur diesel heating oil, a fuel standard already mandated for on-road vehicles and New York City ferries, we can dramatically improve the quality of the air we breathe daily while reducing oil consumption and greenhouse gas emissions through improved furnace efficiency. And we can do it without depending on taxpayer subsidized, unsustainable and environmentally destructive biodiesel.

Michael Heimbinder is Executive Director of Habitatmap, a Brooklyn-based environmental health justice non-profit.Â

Why a Bioheat Mandate?

Over the last year, New Yorkers have been led to believe that the worst thing they can do for the environment is drive their car. According to PlaNYC, cars and light trucks contribute approximately 17 percent of the city’s total carbon emissions, a number that will decrease considerably with the popularity of hybrid and alternative fuel vehicles.

However, a whopping 79 percent of New York City’s carbon dioxide emissions come from buildings -- from the burning of heating oil and natural gas. So environmentally speaking, the worst thing we can do is wait any longer for meaningful building emissions reforms, such as the bioheat and low sulfur heating mandate outlined in Intro 594.

One part of the building emissions problem well within our power to change at the local level is in the heating oil sector. The emergence of biodiesel -- a cleaner-burning, renewable energy source that is processed from plant and vegetable oils in the United States and is blended with diesel for use in trucks and blended with heating oil for use in buildings--has finally made this possible.

A Smart Solution

Bioheat, as this blend of heating oil and biodiesel is called, displaces up to 20 percent of petroleum-based heating oil with renewable “B100 biodiesel” that is made from vegetable or plant oils like soy or recycled restaurant grease.

A “B20 bioheat blend,” which is 20 percent renewable biodiesel, significantly reduces carbon emissions and fine particulate matter, a major contributor to asthma and one reason why parts of New York City have some of the highest asthma rates in the United States. My bill would require this blend be used throughout New York City, in both commercial and residential properties, by 2013.

Bioheat also reduces our dependence on foreign oil by displacing a significant amount of petroleum with a domestic product.

Bioheat seamlessly replaces heating oil in all boilers, requires no expensive modifications and is available today through at least a half dozen companies in the New York Metropolitan Area. Yet only a very small fraction of the 1.2 million heating oil households and commercial heating oil users burn bioheat.

An Immediate Solution

So why do we need Intro 594 to require that all heating oil buildings use bioheat? Because unless bioheat is mandated, we will be having this conversation 10 years from now, while more damage is done to our environment, more New Yorkers suffer from asthma and our dependence on foreign oil continues to be ignored.

That is not to say there aren’t many important questions that need to be addressed:

Cost: Currently, bioheat costs more than heating oil. That is why I sponsored City Council Resolution 1303, which urged the governor and the State Legislature to ensure the passage of a four-year Bioheat Tax Credit, which, fortunately, was adopted in the state budget. It goes a long way to bridging the cost gap for homeowners and residential landlords.

Supply: According to the National Biodiesel Board, in 2006, 250 million gallons of biodiesel were produced in the United States -- more than triple the amount produced in the previous year. And New York City will likely be host to a 110 million-gallon-capacity biodiesel processing facility -- a proposal by Metro Fuel Oil currently slated for Brooklyn, which could be one of the largest facilities in the country.

Equipment feasibility: B20 bioheat has been used in New York City for several years with no reported equipment problems. One of the largest heating oil equipment manufacturers in the country now warranties bioheat and with the ASTM International standards organization set to strengthen its commitment to bioheat this summer, all manufacturers will likely follow suit.

Sustainability: The primary feedstock used to produce biodiesel in the United States is soy. When processing soy for biodiesel, the food value -- which accounts for 80 percent of the soy bean -- is left untouched. Therefore, it is not a “food for fuel” issue. It is also plentiful, with the United States leading the world in soy exports for many years. Recent confusion on “biofuels,” which includes the more controversial ethanol, has led some to question all biofuels-- but the details are what are important. American-grown soy-based biodiesel has not been pegged as problematic. Plus, it is expected by many that in just a few years biodiesel will be made with oil made from algae which can be made cheaper and has higher yields.

A Feasible Solution

In the year since I held the first oversight hearing on the use of biofuels in New York City and then introduced Intro 594, I am proud to have witnessed a broad-based coalition of unlikely allies form around this bill and this issue.

In announcing the bill, environmental groups like Environmental Defense and health advocacy groups like the American Lung Association stood shoulder to shoulder with the New York Oil Heating Association and several heating oil companies. The New York League of Conservation Voters included the bioheat mandate in its 2008 New York City Policy Agenda and the Mayor’s Office of Long Term Planning and Sustainability testified in favor of Intro 594 at my committee’s hearing earlier this year.

There are some who think that New York should wait on a bioheat mandate; that we should wait for California to come out with a report on air emissions; wait for the economy to pick up; wait until a new technology emerges. If we wait long enough, we’ll come up with even more reasons to wait. At the peril of our health and environment, we have waited decades for the forces of science and technology to converge with commercial viability and political will to produce a more renewable, more domestic, cleaner, greener heating product.

The fact is there is no reason to wait. Like gasoline, heating oil is too integrated into our energy infrastructure to disappear any time soon. It is here today and it will be here tomorrow. My bill proposes the how--the only question remaining is when do we make heating oil cleaner, greener and more domestic?

That time is now.

Councilmember James Gennaro has represented District 24 in Queens since 2002. He chairs the council's Committee on Environmental Protection. Â

Jumpstarting the Greenways System

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg made his 2007 Earth Day speech announcing PlaNYC to reduce greenhouse emissions in New York City, scientists were predicting that the North Pole's ice cap would be almost fully melted by 2040. Now, just a year later, the predicted date of that event is 2015.

In contrast, New York City's greenways system, one of our best chances to dramatically reduce transportation emissions, is moving ahead at a glacial pace. Although PlaNYC calls for connections in the bicycle network, and while building a system of greenways has been city policy for more than 15 years, construction has been slow. Due to intransigence by the city Department of Transportation's engineers, greenway development seems to have ground to a halt. The question now is whether a new transportation commissioner will be able to move the glacier in the remaining 20 months of the Bloomberg administration.

The 350-mile city greenways system of pedestrian and cycling trails separated from roadways was to be developed mostly along parks, waterfronts, cemetery edges and other breaks in the street grid, and along parkway and railroad right-of-ways. Sheltered from traffic, the greenways would improve the safety of pollution-free transportation and encourage cycling by children. (Statistics indicate that a smaller percentage of youth are learning to ride bicycles, and surveys show that parental fear of traffic is the reason.)

Over the last 15 years, the New York City parks department has built new trails in parks in every borough, but not one mile to connect these trails has been built along a city street controlled by the city's Department of Transportation. Every effort by advocates and agency insiders to get the department to begin connecting the trails has been thwarted. For example, the Brooklyn Waterfront greenway became a street-widening project that eliminated the sidewalk that was to become the greenway. UN Plaza has been offered at least a dozen times as a way to connect the two segments of the Manhattan East River trail but that never happened.

For the greenway system to serve its purpose, the city must provide sheltered lanes to encourage fearful cyclists to cycle on roadways. Painting stripes on streets does not make a greenway. The city's greenways plan calls for separated trails with trees and landscaping to shield pedestrians from particulate pollution and with clear signage to direct cyclists.

What Needs to Be Done

After 15 years of fighting, I have come up with 10 steps to help the city make greenways a reality. These projects are on the agendas of greenway advocates around the city.

First Avenue first: A separate bike lane, modeled on the new Ninth Avenue lane, should be installed along First Avenue and United Nations Plaza to connect the two existing sections of the East River Greenway. This will give East Side commuters the same continuous off-street cycling option that thousands of New Yorkers who use the West Side greenway have had for years.

Not about Manhattan only: An additional separated bike lane should be installed as an interim greenway along the entire Queens and Brooklyn East River waterfront from Red Hook to Flushing Meadows Park.

The Staten Island commute: The almost completed Staten Island South Shore greenway should be connected to the Staten Island Ferry. Lightly trafficked streets can be easily reconfigured to complete this important commuter route.

Recognize opportunities for major improvement: Crotona Parkway and Southern Boulevard are two parallel streets in the Bronx that are separated by a park not much wider than a traffic island. Crotona Parkway should be reconfigured to discourage through traffic and to encourage bike traffic as proposed in a 10-year-old plan prepared by the Neighborhood Open Space Coalition and the Bronx Council for Environmental Quality.

Greenways are also walking trails: Greenways should be a priority in the Million Trees program and should feature benches and drinking fountains. Creating greened environments for walking is a national health priority since they will increase physical activity.

Make signage easy to follow: "Interim-greenway" signs should be installed along the entire 350-mile NYC Greenways route using the well-recognized and Art Commission-approved signage that has been in use in city parks for years.

Fast track improvements: Measures to protect cyclists from motorists should be implemented along the entire system including greened traffic islands. There should be a citywide strategy and policy for implementation rather than the failed and expensive piecemeal approach.

Put trails on key bridges: While much has been done to improve pedestrian and bike access to the East River bridges over the years, the Verrazano, Whitestone/Throgs Neck and Outerbridge/Goethals bridges continue to be dead ends. The attitude that cyclists can travel around inaccessible bridges and pedestrians can take a bus has to end.

Provide access to all bridges: Many smaller bridges are also inaccessible. The transportation department should inventory bridge access and see that all bridge access points are direct and easy to find.

Create long-distance greenways: A special effort should be made to complete long distance routes that feature the dramatic interplay between the built city and the natural world. The city's greenways would connect to the East Coast Greenway system stretching from Maine to Florida. New York's other long distance greenways include the Gateway Greenway, which connects Jamaica Bay to Sandy Hook, N.J.; and the Hudson River Greenway from Troy, N.Y. and the Erie Canal to the Battery. This would promote ecotourism in the region.

The Benefits of Greenways

There are a number of reasons to implement this program. Existing greenways are heavily utilized. The Hudson River Greenway, for example, is sometimes credited with kick-starting the current cycling renaissance in New York City. But this is not just a Manhattan phenomenon. National Park Service personnel have noted significant increases in cycling past Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn after a greenway link was built along Flatbush Avenue. The more people travel on greenways, whether by bicycle or on foot, the less energy they use, the less pollution they produce and the more healthy exercise they get.

The greenways system was meant to provide a travel alternative for New Yorkers. A disconnected series of isolated local park paths will not accomplish that. If PlaNYC2030's goals of drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions from motor vehicles are to become a reality, the city will need to move quickly to put an alternative infrastructure in place.

Dave Lutz is the executive director of Friends of Gateway and Neighborhood Open Space Coalition, which works for a healthier, greener city.

For a guide to the city's greenways, click here. Â

Making Zero Waste Part of the Plan

significantly reduce New York City's carbon footprint.

Amid the pages and pages of ideas and proposals to move New York toward sustainability in PlaNYC, there is barely a mention of solid waste. Even though solid waste has a huge environmental impact, PlaNYC ignores both the problem and the new movement toward zero waste.

Meanwhile, the extension of the few, current, pilot-sized initiatives in the city's most recent long-term solid waste management plan will do little to prevent. It only tentatively addresses a small portion of the 40 percent of total waste of the waste stream that is the organics fraction. Just a tiny fraction of the sanitation department's more than $1 billion budget goes to waste prevention.

Other forward-thinking countries, states and communities have already set a goal of zero waste and are aggressively implementing programs, legislation and incentives to achieve it. Widely misunderstood, zero waste simply means that our discards are recycled, composted, reused or not created in the first place. None of these materials should be disposed of in incinerators or landfills or exported, as New York currently does with almost 85 percent of its waste.

The Impact of Garbage

PlaNYC showed the volume of greenhouse gases that cause global warming emitted from within the city's borders. Providing that information is a great accomplishment. But the report does not go far enough. It only counts the gases actually emitted in the city, ignoring all the greenhouse gases that result from producing products and packaging that New Yorkers use and from bringing those goods to us.

New York City's carbon footprint (the total amount of greenhouse gases produced to support human activities here) should extend to the activities and communities that supply and manufacture the things that we demand. Various estimates show that "upstream" impacts account for 70 percent of emissions caused by products and materials that eventually become waste. Logging, mining and manufacturing towns have a huge carbon footprint totally disproportionate to their populations. Much of it derives from goods they provide to us. Not taking responsibility for these carbon emissions is wrong also because we then have no impetus to innovate and pursue measures to reduce them (i.e., zero waste initiatives).

The report also ignores the carbon emissions and other impacts of getting rid of waste. It does not include the emission deriving from the disposal of New York City's waste at incinerators in Newark and elsewhere, in Pennsylvania and Virginia landfills or transporting the materials (most of which is recyclable, compostable and/or would not have to be created in the first place) to these facilities.

The city's carbon footprint report indicates that buildings create 79 percent of the carbon emissions, while solid waste was responsible for only 3 percent of the city's greenhouse gas emissions in 1995 when the Fresh Kills landfill was open and zero after that. For all the reasons mentioned, this is an inaccurate estimate.

The effects of landfills, the most common waste management practice used by New York City, are particularly damaging, according to the federal Environmental Protection Agency. "It results in the release of methane from the anaerobic decomposition of organic materials. Methane is 21 times more potent a GHG than carbon dioxide," the agency has found.

Incineration creates toxic ash that must be disposed of. Despite significant technological advances in reducing emissions of toxic gases, greenhouse gases are emitted from waste-to-energy plants, and the amount of energy they generate is less than the amount required to log, mine, manufacture and move new materials to replace them.

If the city were to acknowledge the environmental impacts of its residents' demand for goods and materials, it would have to take a much bolder approach to conserving materials than its does in its 2030 goals or solid waste management plan. Conversely, if we disassociate ourselves from the contributions that our demands for and disposal of products and packaging make to global warming, we will have no reason to reduce our consumption and increase reuse, recycling and composting.

Cutting Back on Waste

No method can reduce the environmental impacts of waste as much as waste prevention. New York State's Solid Waste Management Act of 1988 states that waste prevention is the most environmentally desirable option for dealing with solid waste. Recycling, reuse and composting are near the top of preferred methodologies.

Recognizing a need for a bolder vision, in 2004 a coalition of solid waste experts, including myself, wrote "Reaching for Zero: The Citizens' Plan for Zero Waste in New York City," a 200-page, 20-year plan. Each year is packed with innovative measures to maximize waste prevention, reuse, recycling and composting, and with associated economic development, education, enforcement, transportation, financing, legislation and research. It proposes specific short, mid and long-term tonnage goals, overall as well as for prevention, reuse, recycling and composting. The report recommends the creation of an extensive new reuse and composting collection and processing infrastructure and innovative pilot and research programs.

Examples of short-term measures to bolster reuse include 40 neighborhood swap shops, four reuse complexes and four material recovery facilities with a fleet of trucks. Mid-term examples include construction of anaerobic digestion facilities to convert 45 percent of the city's food, yard and soiled papers to biogas and an organic fertilizer product, which can be used elsewhere.

The plan calls for legislation to ban recyclables and compostables from export to landfills and incinerators and to require that manufacturers take back more products for repair and reuse. A "pay as you throw" billing system, used in 7,000 U.S. communities, would reward residents for recycling, composting and throwing out less waste and penalize wasters. As export is reduced, jobs in the local reuse, recycling and composting sectors would rise. Clearly, zero waste would have been a perfect framework for PlaNYC and the city's solid waste plan.

In 2005, I organized an environmental coalition to work with the Assembly to strengthen and modernize the state's Solid Waste Management Act so that local plans would have to adhere to practices aimed at achieving zero waste and that municipalities would actually implement all measures in those plans. (To read the coalition's legislative redraft and recommendations, click here.)

Here are specific recommendations for how the city can get closer to zero waste.

* Add a commitment to PlaNYC to ensure movement away from export, landfilling and incineration toward achieving zero waste disposal by 2030.

* Correct the city's carbon footprint inventory document to account for and take ownership of the greenhouse gases produced elsewhere as a result of demand and acquisition of materials by the city and its residents.

* Correct the city's solid waste management plan so that it adopts the measures recommended in "Reaching for Zero."

* Supply the funding necessary to implement the zero waste measures.

* Enact the modifications to the NYS Solid Waste Management Act of 1988 to modernize the policy goals to include zero waste and require that localities' plans include and that they implement a sufficient number and diversity of these measures.

Maggie Clarke of Maggie Clarke Environmental has a doctorate in earth and environmental sciences and is a long-time New York City-based solid waste scientist, researcher, educator, and activist.Â

Clearing New York City Streets

The state legislature's refusal to approve Mayor Michael Bloomberg's plan to collect a fee from drivers entering the most congested parts of Manhattan leaves unanswered the question of how to finance construction of transportation infrastructure vital to the city's future. But on the narrower problem of reducing congestion, New York City has a pricing mechanism it can employ for use of the streets without asking Albany's permission: Parking.

Undervalued parking is a major enticement for people to bring cars to the city. In fact, the availability of free parking at or near the workplace is the single best predictor of whether someone will drive to work. Too many employers provide subsidized parking to their workers. And among those employers are all levels of government and the court systems.

Stop Giving Away the Streets

The mayor recently announced the first steps in controlling the rampant use of "placards" that permit users to park in any legal spot without paying -- and are often abused to include parking illegally, in bus stops, alongside hydrants and even on sidewalks. A city-issued report on placard usage in Lower Manhattan found that "there typically are no available legal spaces" for drivers arriving midday as placard vehicles are ubiquitous -- leaving the new arrivals to drive around, adding to traffic as they seek a space. The report confirmed the popular impression that placard holders often have free rein to ignore the law entirely.

This is not just a Manhattan problem. Free-parking privileges encourage police officers and teachers, in particular, to drive their private cars to precinct houses and schools - all over the city. The same is true for clergy, who receive free spaces in front of their houses of worship. Press and diplomats also have special privileges, which encourage them to use cars.

Even when street parking is not free, it's too cheap - a small fraction of what it costs to park in a garage. Convenient curbside parking should be somewhat less expensive than secure off-street parking, but not to the extent it is now.

The mayor's PlaNYC most famously proposes the congestion charge, but it also includes an initiative to expand the use of Muni-meters to commercial districts throughout the five boroughs. These advanced meters allow parkers to use a variety of cash and non-cash forms of payment. The city should take this opportunity to raise prices for curbside parking - now the cheapest real estate around - and use the available technology to raise and lower prices according to demand.

Keeping Cars Moving

To decrease traffic, parking lanes must cost more, and moving lanes must stay clear. New Yorkers name the same street-clogging problems over and over: double-parking, taxi pickups and drop-offs, and "blocking the box" (entering an intersection when unable to exit it during a signal cycle, thus backing up traffic for at least a block).

Stepping up enforcement of box-blocking is another PlaNYC priority. Unfortunately, it requires Albany's good graces to allow Traffic Enforcement Agents to issue tickets for this infraction - which is technically a moving violation. But the New York Police Department can enforce the gridlock law now -- and should.

The Traffic Congestion Mitigation Commission, which recommended the congestion-pricing program, also suggested adding cab stands at key sites. The city could expand on that idea and identify curb areas -- possibly including vacant bus stops -- for taxi pick-ups and drop-offs.

Cracking down on double-parking requires no new program at all - just making it a priority for law enforcement.

Finally, the city should put an end to practices that increase traffic backups: streets closed for fairs, parades, and motorcades; overzealous security barricades; unnecessary obstructions from construction projects.

These remedies are not glamorous, and they won't yield the funds New York needs for building subways, fixing bridges, and buying buses, but they will help ease the city's traffic for now and until some brave new mayor tries once again to advance some version of congestion pricing.

Hope Cohen is deputy director of the Manhattan Institute's Center for Rethinking Development.Â

Reclaiming New York's Blighted Waters

From his 30-foot wooden skiff, Andy Willner points out a sailboat headed north through the narrow tidal strait. A double-crested cormorant flies above, its sleek black form unmistakable on the powder blue sky. A grassy mountain rises behind the sailboat, stretching for miles. In a few hours, low tide will bring snowy egrets, glossy ibis and great blue herons by the score.

At this moment, it is easy to forget that the mountain is Fresh Kills Landfill, the largest landfill on earth, so massive it is among the few manmade structures that can be seen from space. Just as improbably, the water under the boat is the Arthur Kill, arguably America's busiest industrial waterway, lined on both sides with refineries and factories.

Since a massive oil spill in 1990, nature has staged a remarkable comeback here, thanks in large part to a newfound appreciation for how improvement of long-neglected waterways like the Arthur Kill can enhance the quality of life for millions of people.

The story of Arthur Kill is remarkable in and of itself. It also parallels the journeys of other industrial waterways in New York - from Newtown Creek to the Bronx River - that advocates hope will someday run clean, providing habitat for wildlife and recreation and respite for New Yorkers.

Launch the slideshow

Curtailing Pollution

Connecting Newark Bay with Raritan Bay along Staten Island's western shore, the Arthur Kill is vital to New York Harbor and the Hudson-Raritan Estuary. With the Manhattan skyline visible in the distance, thousands of tankers ship billions of gallons of oil through the strait each year, making the Arthur Kill more heavily traveled than the Panama Canal.

As recently as a few decades ago, the Arthur Kill was so polluted that crabs and clams would die within an hour of being submerged in its waters. That began to change with the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, which forced the construction of modern sewage treatment facilities throughout the metropolitan area.

"The Clean Water Act reduced sewage runoff, and the water improved dramatically," says Katharine Parsons, a senior scientist at Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences. "That allowed crabs and shrimp to recolonize the area, and the birds followed." Beginning in 1986, Parsons fund the numbers of egrets, herons and increasing by 15 percent each year.

That all changed on New Years Day 1990, when Exxon spilled 567,000 gallons of oil into Arthur Kill.

"We had just started monitoring the kill in 1989, and you talk about being baptized in oil," says Willner, who is retiring after 18 years as executive director for the environmental organization NY/NJ Baykeeper. "It was awful, but it led to the restoration and awareness of how important these wetlands were. These smaller parcels are like the last little gardens of Eden in this vast gray industrial area."

The oil spill was particularly damaging for birds such like snowy egrets and glossy ibis, which tends to be choosy eaters and could no longer rely on the crabs devastated by the massive oil spill.

For nature to bounce back, humans had to take a more active role. Later that year, New York City and the state Department of Environmental Conservation agreed to allocate $600 million to clean up Fresh Kills and other leaking city landfills. Federal agencies joined state and city agencies in New York and New Jersey in addressing the mounting debris, much of it from garbage barges going to Fresh Kills, that had ruined shorelines throughout the metropolitan area and forced hundreds of public beach closures in the late 1980s.

Through the Floatables Action Plan, over 350 million pounds of debris have since been collected from New York Harbor. By surveying the harbor and picking up the waste, the plan managed to control the driftwood, plastic bags and bottles, garbage barge waste, and other debris that lined the banks of Arthur Kill.

"Once people began managing a lot of the waste going to Fresh Kills, habitat started to develop," says Mark Gallagher, an environmental consultant who has worked on wetlands restoration projects. "When the shoreline was covered with floatables, it was awfully hard for herons to forage."

The infamous stench that often wafted over the region was finally corralled with the construction of a landfill gas extraction system that captures the methane and converts it into reusable natural gas.

The city shut Fresh Kills in 2001. That same year, Fresh Kills upgraded its leachate collection system, finally containing the hazardous runoff that had flown unabated into the Arthur Kill and New York Harbor for decades. Together the two events had a major effect. Recovery could begin - with a little help.

Rebuilding a Habitat

The area could begin to heal itself. "Nature has a built-in resilience to it," says Glenn Phillips, executive director of New York City Audubon. "For wetlands, their job is to mitigate the environment. If we leave them alone, let them do their work, they fix our mistakes."

Nature needed a little help, however. At restoration sites throughout the estuary, salt marshes destroyed by industry and oil spills are being replanted with native spartina alterniflora, a hardy salt-marsh cordgrass that may have evolved natural resistance to low levels of contamination.

Ecologists replanted six acres under the Goethals Bridge after the Exxon spill, and helped it become a thriving salt marsh again. Six acres is hardly a vast wilderness, but it is a start. Each of those single acres can hold a million fiddler crabs.

"It's the corniest line, but it really is true with tidal wetlands - if you build it, they will come," says Gallagher. "The very first day you let the tide come in, the fish and crabs come in with the tide. Soon after that you see birds... there to eat the fish."

The buffet lasts all year, as the Arthur Kill remains ice-free even during the fiercest winters. When ice seals off the Raritan River and other nearby rivers and lakes, thousands of buffleheads, mergansers and other ducks flock to the Arthur Kill at the mouth of its largest tributary, New Jersey's Rahway River.

Over 8,000 acres of the Arthur Kill watershed have been preserved, mostly along its tributaries. Nearly 4,000 wading birds now nest in the estuary. Many of them feed in the Arthur Kill and nest on the archipelago of small islands in Kill Van Kull and the East River. The abundance of the "harbor herons" would have seemed far-fetched a century ago, when many of these species were on the verge of extinction.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1914 allowed the herons and egrets to recover around the nation, but they seemed to be in no hurry to recolonize the filthy waters of the Big Apple. Now the recovering ecosystems of Fresh Kills Landfill attract birds migrating along the Atlantic Flyway, forming a substantial wildlife corridor with the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge and the 2,500-acre Staten Island Greenbelt.

Other wildlife has returned as well.

Bill Schultz, the long-time Raritan Riverkeeper and a former Perth Amboy fireman, began wreck-diving in the Arthur Kill about 20 years ago. He has seen the harbor's biodiversity improve first-hand, encountering schools of fish swarming like a single organism, loggerhead sea turtles, and even a sand shark.

Most dramatic is New York Harbor's own Atlantic sturgeon - an armor-plated, toothless behemoth that evolved during the reign of the dinosaurs, and can grow as large as 12 feet long and weigh nearly 800 pounds.

People also are starting to return to this Industrial Venice. "There's no question public use is increasing in the Arthur Kill," says Willner, who kayaks the harbor with other environmentalists in a group they jokingly call "Nine Jerks," short for NY-NJ Endangered River Kayakers. "We see sailboats a lot, and people picnic in some spots and even swim or jet-ski."

At Staten Island's popular Tottenville Beach, visitors walk along outcrops of terminal moraine, where the Wisconsin Glacier reached its limit around 75,000 years ago. The Hudson River initially carved out the Arthur Kill - "kille" is the Dutch term for river channel - when its main channel was blocked by glaciers or moraine east of Staten Island. Those remnants of the last ice age remained visible on Tottenville's old roads, which were paved with millions of oyster shells in the early 1900s.

North of Tottenville, Fresh Kills now points the way to further use of the area. The Parks Department is transforming 2,200 acres of once-noxious land - nearly half of which is actual landfill - into a public park. Three times larger than Central Park, Fresh Kills will again be home to native habitat from maritime oak forest and pine barrens to salt marsh and native prairies, as well as athletic fields and nature trails.

The future park offers guided bus tours twice a month from April to November, and the tours fill up quickly, according to Parks Department spokesperson Trish Bertuccio.

"People are looking forward to creating new memories, and they're anticipating something great," she says. "We call it a park of the 21st century, catering to a new generation of park users that do things like kayaking, canoeing, mountain biking and watching birds, and maybe even horseback riding."

Construction of the park's first project, recreational fields at Owl Hollow, starts this spring. The complete Fresh Kills Park, however, is estimated to take at least 30 years.

The Challenges Ahead

Much still remains to be done for the Arthur Kill to fully recover.

"The progress has been extraordinary," says Baykeeper's Willner. "But like many places in the estuary, it's been one step forward, one step back."

The kill's undersea life - including bluefish, winter flounder and striped bass - offers a perfect example. The soaring population of fish has attracted recreational anglers and crabbers. But government advisories warn against frequent consumption of locally caught seafood, particularly for children and pregnant women.

"Some of the most contaminated areas still in New York Harbor are the sediments of Arthur Kill, Kill Van Kull, and Newark Harbor," says Parsons. "The sediment problems are not intractable, but they're very difficult. They're not just a problem for the birds, but for subsistence fishermen who may not understand the risks they're taking in eating contaminated fish."

Last year's New York City Audubon survey of the harbor herons also found no herons nesting on the Arthur Kill islands. "They nest in New York, but they almost entirely forage and feed in New Jersey," says Audubon's Phillips.

Experts attribute the Arthur Kill's nesting decline on raids on nests by raccoons and other mammals, human disturbance and a recent Asian longhorned beetle infestation, which required many suitable nesting trees to be destroyed.

For Parsons, the recent decline in breeding by wading birds in the Arthur Kill is telling.

"The legacy from the industrial era caught up to them," she says. "It caused the birds to not reproduce enough to be sustained. Even though they were successful, they were marginally successful."

"New York Harbor is definitely experiencing an improvement, a slow purging of the toxins the way you would expect," says Parsons. "It's a cause for hope, although not at the pace needed by these birds on the harbor today."

On to the Bronx and Brooklyn

As the activists of the Arthur Kill work to speed up a long-term recovery, similar goals are being pursued on polluted waterways across New York City.

In the heart of the Bronx, the Bronx River Alliance teamed with the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, the parks department, the Army Corps of Engineers and dozens of other groups, agencies and residents to restore the lower Bronx River, an eight-mile stretch infamous for its urban decay. The alliance combines monitoring and cleanups with recreation like greenway biking trails and kayaking programs.

The Canal, on the Brooklyn waterfront, was long known for its stagnant, putrid water. But in 1999, the environmental protection department reactivated the canal's pump system after 40 years of neglect.

"Now we have horseshoe crabs using the shallow water for their mating dance in the spring, then blue crabs coming in for mating, and by fall large schools of fish," says Owen Foote, a founder of the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club. "Shortly after sunset, the whole shoreline comes to life with the splashes where the big fish are eating the little fish."

The Gowanus Dredgers host public canoeing events and shoreline cleanups, and they've launched similar clubs along Newtown Creek between Long Island City and Greenpoint, the East River's Buttermilk Channel, and the Staten Island shoreline.

Still, the water is by no means pristine. "Our t-shirts on the back say, 'Don't flush when it rains,'" says Foote, "because the sewage plant can't handle the capacity and it goes straight into the water."

The DEP last year approved a $125 million water quality improvement plan to modernize the canal's pumping station and reduce the levels of sewage discharge into the Gowanus. While this will help, heavy rains will still send sewage into the canal.

New York City's sewage problem is hardly limited to the Gowanus. Each year, an estimated 27 billion gallons of raw sewage and polluted stormwater enter New York Harbor, a particular problem for sheltered waterways such as the Gowanus.

While modernizing the sewage system will take years and cost millions, source controls - planting more trees and vegetated areas - could prove equally effective at capturing the stormwater before it enters the sewage system. Cities such as Chicago and Washington D.C. successfully utilize similar greening measures to control runoff.

The challenges facing New York Harbor are many. But if the Arthur Kill can start to recover, with all the deadly destruction heaped into its water and along its shoreline, there is hope yet for just about any waterway.