New Rules Clean Up Dirty Ships

Large ships bring us the goods we want, when we want them. The coffee at the deli, the car on the lot and the sneakers in the store window — it is likely that they all came to New York on huge ships. Unfortunately though, these vessels also bring us something we do not want: pollution.

Ships remain some of the dirtiest polluters around. Now, however, the city and the federal Environmental Protection Agency have taken important steps to protect our health and reduce this air pollution. Harbor City The pollution from ships poses a particular problem for New York. Our region is home to the busiest port complex on the eastern seaboard. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey handles every type of cargo imaginable at Port Newark, Elizabeth-Port Authority Marine Terminal, Howland Hook Marine Terminal, the Auto Marine Terminal, Brooklyn-Port Authority Marine Terminal and Red Hook Terminal. (For a map of these facilities, click .)

Cargo growth is expanding unchecked with no end in sight -- a function of our global economy. In 2006, port facilities moved more than 30 million tons of ocean-borne cargo and handled 5 million 20-foot equivalent units, or TEUs, a measure equal to the size of a standard shipping container. This represented a sharp increase from the 2.2 million TEUs and 21.6 million tons of cargo in 2002. In New York, ships also carry people. If you live on Staten Island, your primary connection to Manhattan may be the orange-coated Staten Island Ferry, which carries 65,000 passengers every workday. And the region boasts new ferry and water taxi services each year.

Far from Ship Shape

Unfortunately, these large ships are the last bastion of dirty diesels. They emit huge quantities of a pollutant that the Environmental Protection Agency regulates as "PM10." This particulate matter is less than 10 microns in diameter, about 1/7 the width of a human hair, and is what most people would call "soot." When emitted by diesel engines, this soot contains dozens of known and probable carcinogens, and has been linked with hundreds of thousands of asthma attacks, nearly 24,000 premature deaths and more than $160 billion in health costs annually.

These ships also emit large amounts of a family of gases known as nitrogen oxides (or "NOx"). NOx emissions are a principal culprit in the region's chronic smog, the summertime pollution that can cause permanent lung damage and make city life harder for asthmatics, children, the elderly and others with heart or lung ailments. Unlike trucks, buses, construction equipment and other diesel engines (which are getting cleaner every year), the diesel engines that power our ships were, until very recently, virtually unregulated.

Cutting Ship Emissions

That is changing. On March 14, the federal Environmental Protection Agency announced a strong, new program that will dramatically clean up these engines in years to come. The plan, contained in a rule announced by agency Administrator Stephen L. Johnson, will cut soot pollution from new ship (and train) engines by 90 percent, starting in 2015. It will also cut NOx emissions by 80 percent, beginning in either 2014 or 2015, depending on the size and type of engine. And from now on, today's dirty engines will be required to be rebuilt to cleaner levels when they undergo their regularly scheduled overhauls. Since they get overhauled every four to five years, we will see significant emissions reductions fairly quickly.

Thousands of hospital visits and almost 1,400 premature deaths will be avoided nationally every year, as the nation's 40,000 ships and 21,000 diesel locomotives clean up in years to come. This also is an extremely cost-effective way to cut pollution. Judging from EPA's data, every dollar invested in cleaner diesel engines should result in up to $15 in health savings. Of course, ships last for decades. So, the region's port operators and freight haulers need to find ways to accelerate the clean up of today's dirty engines. We shouldn't have to wait for decades to reap the full benefits of EPA's new regulation.

Fueling the Ferry

Here in the city, cleaner ships are already on the way, In February, Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed a new law passed by City Council that will reduce the pollution plume from the Staten Island Ferry right now. This creates a model that may one day clean up all of the ferries and water taxis operating in New York Harbor. It's a significant step toward reducing ship pollution in New York. This new law requires the Staten Island Ferry to run on low-sulfur emission fuel and use the best-available pollution-cutting technology. Cleaner diesel ferries are already possible. A 2006 study by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority of private ferries in New York Harbor showed that using the low-sulfur fuel and a basic catalyst reduced soot by 32 to 60 percent. Ferries that were rebuilt to the levels in the new Environmental Protection Agency rule reduced soot by 84 percent and NOx by almost a quarter.

Indeed, some ferries have already taken important steps to reduce their emissions. The John F. Kennedy, the oldest boat in the fleet, was the first to use the new fuel, which combines truck-grade ultra-low-sulfur diesel fuel with 5 percent biodiesel. In 2006, a custom-built selective catalyst reduction system was added to the Alice Austen ferry. It reduces the ferry's emission of nitrogen oxide by 16.5 tons a year. The bottom line: The pollution caused by the ships steaming through New York Harbor has not been a front-page story. But ships add significantly to the pollution affecting all New Yorkers. Thanks to two important steps taken at the city and federal level, New Yorkers should reap significant benefits for years to come, while still enjoying goods from far away and the sunsets from the decks of the Staten Island Ferry.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard.Â

A City by the Sea -- or Under It?

Columbia University promises that its new campus in West Harlem will boast tree-lined blocks, new outdoor cafes and glass-walled buildings where arts and research will flourish. There's one problem, though, according to Klaus Jacob, a special research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University: It could all be underwater.

Under Jacob's worst case projections, more than half of the new campus could end up submerged by water if hit by the right storm.

Columbia's planners could have minimized the risk of damage, Jacob argues. Instead, they plan to build one large basement that connects the entire 17-acre campus, meaning that if one building floods, they all flood. Furthermore, he said, by locating the new campus' power plants underground, the school puts its energy source at risk.

The Columbia expansion is not the only large-scale project in New York in danger of flooding. With climate change promising more violent and frequent storms, much of the planned and existing development in the city could face severe floods,

Using a slide show he has developed - a kind of New York City centric "Inconvenient Truth" - Jacob is promoting the need to plan for the effects of climate change. While they may not have seen the presentation, many people are concerned. According to a survey released this week by Columbia and Yale Universities, 69 percent of New Yorkers believe "it is likely that parts of New York City will need to be abandoned due to rising sea levels over the next 50 years."

So how is the city preparing? Ron Shiffman, former city planning commissioner, has not seen much indication they are. "I think it's a big question mark," Shiffman said. "They say they're working on it, but I have yet to see anything."

Any decisions made in New York City about the best way to incorporate risks from climate change into land use plans would not be implemented until after Mayor Michael Bloomberg leaves office. That would be after the city has undertaken what Bloomberg has called "the most fundamental and geographically significant changes since the 1960s" -- and a redevelopment plan that, in the view of many, does not address the new reality of a wetter, warmer New York.

THE GROWING RISKS

With some 600 miles of waterfront, New York City is particularly vulnerable to storm surges and rising seas -- and to the effects of a warmer climate.

The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates temperatures will rise between four and thirteen degrees Fahrenheit in the next 90 years. Higher temperatures will increase the intensity and frequency of storms, lead to more rainfall during the winter due to less snow and create rising sea levels, all of which will make flooding more common and severe. Even under an optimistic scenario, the group predicts that the kind of flood the city now expects once every 100 years could occur an average of every 22 years by the turn of the century.

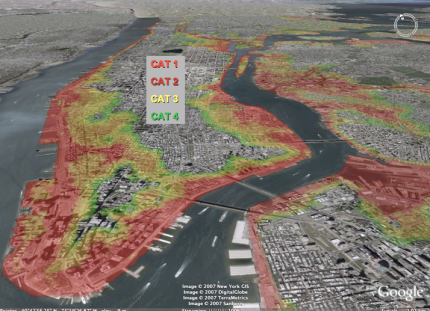

Over the next 80 years, sea levels around New York City could rise by 11.8 to 37.5 inches, according to calculations by the U.S. Global Change Research Program. As a result, "flooding by major storms would inundate many low-lying neighborhoods and shut down the metropolitan transportation system with much greater frequency," said a paper by the Columbia University Center for Climate Systems. Given this, the paper continued, many areas would face flooding from a Category 3 hurricane, including "the Rockaways, Coney Island, much of southern Brooklyn and Queens, portions of Long Island City, Astoria, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens, lower Manhattan, and eastern Staten Island from Great Kills Harbor north to the Verrazano Bridge."

The city's infrastructure could take a particularly heavy hit, according to Matthew Bowman, head of the Storm Surge Research Group at Stony Brook University. This, he has said, "includes subway entrances that are close to sea level, tunnels and their air and vent shafts, subway track and signal systems, bridge access roads, small bridges, airports, port freight-handling facilities, water pollution control plants and their tide-gate regulators, combined sewer outfalls, landfills, solid-waste transfer stations, pipelines, power plants, and buildings in areas with high property values and dense population."

Overall, Bowman figures, "In the future, a weaker storm will do the same damage that a severe storm does today."

How will this be experienced in different parts of the city?

Ground Zero

Storms could bring 10 foot-surges to lower Manhattan, affecting much of the new development planned in and around Ground Zero. The World Trade Center memorial could flood "unless they have special flood gates to seal it off," Vivien Gornitz, a special research scientist for NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies at Columbia University, told the Downtown Express.

The Lower Manhattan Development Corp. has dismissed the danger. "The designs would be resistant to those types of flooding dangers," a senior advisor, Victor Gallo, has said.

The structures in the trade center site will be set in a foundation popularly referred to as the bathtub. "This bathtub, with its memorial, with its museum and several other structures inside it and adjacent to it, could very well be flooded. Now, to pump out a whole bathtub with all those things - I think is not what we were looking forward to," Jacob told National Public Radio.

The transportation hub being built on Fulton Street also is vulnerable to flooding because of its low elevation, Jacob said.

Nearby neighborhoods, such as Greenwich Village and Little Italy, also are at very low elevations. Many buildings in these areas have masonry foundations, making them particularly vulnerable to damage, Joe Tortorella, a structural engineer and a member of the Disaster Preparedness Task Force of the American Institute of Architects, said in the Times.

In a severe storm, "if the water moves fast enough and recedes fast enough, there could be scouring like a tide that takes sand with it on the beach. As the water recedes, it pulls silt out and could undermine the building," Tortorella said. "It could be a disaster of epic proportions in New York for the smaller buildings."

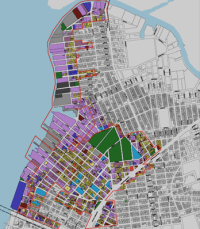

Brooklyn Waterfront

Areas of the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront slated for development -- which aim to bring tens of thousands of new residents -- are at risk of being flooded by a hurricane, according to the city's own maps. Sewers in Greenpoint already cannot deal with the rainwater from severe storms, such as those of last July and August.

Writing in the Brooklyn Paper, Tom Gilbert, a writer and historian who lives in the neighborhood, described driving on Morgan Avenue at the height of a major storm last July: "A river of water as high as my hubcaps roaring down the street and cascading over the sidewalk into basements, as panicked residents ran out of their houses."

Such a scene, he continued, reinforces "continuing doubts about how well the infrastructure of North Brooklyn is handling the building boom of the past five years and how well city and state government are managing this explosive growth."

Much of the new development "will occur along the East River waterfront, which is subject to flooding from storm surges. New construction will result in significant changes to the floodplain that may reduce its capacity for flood retention or alter stormwater flow characteristics," said Brooklyn Community Board One's Rezoning Task Force in comments on the draft of an Environmental Impact Statements on rezoning the area to accommodate more development.

For its part, the environmental impact statement generally says all new structures in the area should meet existing city and Federal Emergency Management Agency requirements. But it notes, "the proposed action would not involve any direct public funding for flood prevention or erosion control measures."

Queens

The changing climate threatens existing developments as well. The vast majority of damage resulting from this summer's flash floods were in Queens. After that storm, an underpass in Glendale was covered with 10 feet of water, raw sewage was forced up through people's toilets and sinks in Queens Village, and the tracks at Long Island Railroad's Bayside station were immersed.

Much of the area is on land that is low lying and getting even lower. Emily Lloyd, commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection, has said that the water table in southeast Queens has risen 30 feet in 20 years, and now sits "just below the surface."

In March, the city created a Flood Mitigation Task Force to identify hotspots for flooding throughout the borough by March. Some progress has begun, and last month the Department of Environmental Protection announced a six-year effort to build a drainage pipe for Whitestone.

FACING THE PROBLEM

No matter what government, business and individual citizens do, a flash flood, is difficult to deal with. "All of the underground infrastructure basically becomes a drainage ditch," said Rae Zimmerman, professor of planning and public administration at New York University. But, she added, much more could be done to prevent these problems.

Task Forces and More Task Forces

Much of the planning to prepare for the effects of climate change will begin under the auspices of the myriad taskforces and advisory boards that are being formed as part of PlaNYC, the city's long term sustainability plan .

The administration is creating a multi-agency Climate Change Task Force to figure out how to protect the city's infrastructure. Most of that - including the subways, electricity and gas distribution systems and communications network - is underground.

The Department of Buildings is creating its own taskforce, and part of its goal is to develop amendments to the building codes to make buildings more storm resistant and inhabitable even without power.

Better Sewers

Perhaps the first problem the city needs to address is its sewers, which cannot cope with even normal amounts of rain. PlaNYC laid out a number of pilot studies for strategies to keep water out of the system in the first place. But after the subway flooding in August, the City Council took a more aggressive approach and passed legislation mandating a sustainable stormwater management plan by October. Another bill would mandate that capital projects paid for with a significant amount of city money retain, reuse and treat stormwater to keep it out of the sewers.

While experts support the new law, they consider it only a first step and are waiting for details to emerge. "The new law is definitely going to take the city in the right direction," says Larry Levine, a water expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council. "But just how quickly and effectively remains to be seen."

Housing

Providing temporary housing for a large, displaced population will take substantial planning. In beginning that effort, the city's Office of Emergency Management recently published the results of its design competition to create post-disaster housing.

The 10 winners of this competition all create homes that could be easily built and arranged to promote community. Each has been awarded $10,000 to further develop their projects, which will then be displayed again in May.

One would build homes on a series of barges attached to the mainland by threads that carry electrical cables and water and sewer lines. The barges would remain after reconstruction to provide parks and help restore a shoreline ecology decimated by centuries of industrialization. Another would use the debris from a disaster to create piers for new housing to be built upon.

Providing Insurance

Since 2004, 50,000 residents in the metropolitan area have had their homeowner's insurance policies canceled because of the risk of floods. Allstate, State Farm and Liberty Mutual now refuse to write new policies in the city because of the danger, according to the New York Times.

To help reduce rates in the city for flood insurance, which is issued by the federal government, PlaNYC wants the city to join a federal plan called the Community Rating System, which calls for lower insurance premiums in communities whose flood management plans exceed federal standards.

GRASSROOTS EFFORTS

Many experts believe that for any of these ideas to work, the public must play a key role. "Public support, or even public pressure" is needed to get city officials to confront the changing circumstances, said Susanne Moser, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who coauthored a report on this issue. "That means the public needs to know what to support, what to oppose .... It's important for citizens not to leave policy-making or policy-implementation only up to influential interests."

The city has started a pilot program to engage communities to help plan for the possible effects of climate change and to share their expertise about their neighborhood with officials. The first effort is in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, in partnership with UPROSE, a local Latino community group. The organization has held three planning discussions with a host of local residents with a goal of creating a climate change adaptation plan that reflects the community's thinking.

"We are looking at planning efforts, which may be different when you put the climate change lens on them," says Elizabeth Yeampierre, the group's executive director. "But we don't really know how the city is going to respond to this in the end. The problem is really the cost: What can or can't the city afford to do."

UPROSE hopes to have developed a plan by this spring.

WHAT OTHER CITIES ARE DOING

Although New York has begun confronting the effects of climate change, other governments in the nation are farther along in the process.

Kings County, Washington, which includes Seattle and its legendary rainfall, has made climate adaptation an integral part of its planning process. The county government's overall climate plan includes the Flood Control Zone District, an agency that builds and improves flood management infrastructure, buys back property at risk of flooding and limits new development that would contribute to flood risks.

King County Executive Ron Sims, the county's global warming team and the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington have written a roadmap for local, state and regional governments that wish to include climate adaptation in their planning.

"There are still many people who are reluctant to talk about specific adaptation or preparedness policies. But as responsible public leaders, we cannot afford the luxury of not preparing," Sims wrote in the introduction to the guide.

The map is being distributed through the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, which has started a new program called Climate Resilient Communities.

One of the earliest places to become a climate resilient community is Keene, New Hampshire, a city of about 23,000 people. Its Climate Adaptation Action Plan would identify areas with a 2 percent or greater chance of flooding every year and prevent future development in those areas.

It may come as no surprise that Keene is ahead of the curve. The city was ravaged by a storm of such intensity in 2005 -- one it is only expected to experience once every 500 years.

LOOKING FOR ANSWERS

Given that New York is an old and crowded city built on islands and along shorelines, experts agree there are no easy answers to protect its buildings and systems from flooding.

The subway and the sewers point out the complexity of the problem. Any water taken out of subways tunnels during a severe storm, such as last summer's, ends up in the sewer system, overtaxing that infrastructure. "You solve one problem and you create another," Madan Naik, chief structural engineer of New York City Transit, has said.

Others have envisioned barriers that will literally hold back the sea, such as those used in the Netherlands. In particular, some scientists have envisioned a system of three barriers that would operate together: one at the the Narrows at the mouth of New York Harbor between Staten Island and Brooklyn, another across the Upper East River and the third at the mouth of the Arthur Kill between New Jersey and Staten Island.

Jacob offers anther solution -- one that seems almost impossible to implement in a growing city of 8 million always searching for more space. He called for simply pulling back from low-lying, flood prone areas. "That," he has said, is the "price to be paid for pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere."

Â

Opening the City's Greenmarkets

Everyone loves a farmer's market. From the bright, eye-catching crimson of cherries in July, to the subtle smell of cinnamon apple cider in January, they offer sensory delights during all seasons. Unfortunately, until recently, lower income New Yorkers often had limited access to the city's greenmarkets.

Residents of the city's less affluent communities have long complained that finding healthy foods, especially fresh produce can pose a real challenge in their neighborhoods. Now a series of initiatives by the city and state hope to make it easier for more New Yorkers to shop at farmer's markets.

Payment Problems

In 1999, the state government stopped the distribution of paper food stamps and joined the federal transition to Electronic Transfer Benefit, or EBT, cards. While this change was much more convenient for large supermarkets, the city's farmer's markets, which are open-air, had no access to the outlets necessary to process the electronic payments.

To address this, in 2001, the state Department of Agriculture and Markets and the Farmers' Market Federation of New York launched "The Wireless EBT Project," which provided wireless EBT machines to some individual farmer's market vendors. Although consumers generally applauded the effort, the machines often experienced delays of 20 to 30 second when processing the payments, a problem in the markets, where vendors rely on many small, quick sales.

In response, the project changed its format. Rather than give wireless terminals to individual vendors, some markets received a central terminal. Consumers swiped their benefit cards in exchange for wooden tokens, which they can then spend them as cash in that particular market. At the end of the day, farmers handed in their tokens to the manager for reimbursement. Although this made it easier for people to use EBTs, not every market could afford the central terminal or to have a manager to perform these duties.

In May 2006, City Council President Christine Quinn proposed allocating $81,200 to buy EBT machines for individual farmers, with the purpose of providing food stamp recipients with greater access to greenmarkets. Two markets received central EBT terminals, and two more were given EBT terminals for each vendor. Signs in English and Spanish informed consumers that food stamps were accepted.

Producing Results

Two years later, it seems that almost no one has anything bad to say about the EBT machines being used in the markets. Electronic benefits sales have increased from $1,000 in 20005 to $40,000 last year, according to Michael Hurwitz, greenmarket director for the Council on the Environment, which operates the greenmarket program. The terminals, he said, "have brought more money to farmers, and customers are thrilled that they can use them."

"There's been a tremendous positive response from customers," said Bob Lewis, the chief marketing representative for the state Department of Agriculture and Markets. "The advantage is that then the farmer doesn't need to have a terminal, so there's no account which requires a monthly fee. The other thing is that the farmer doesn't need to be authorized with food stamp program, so there's very little paperwork involved."

The East New York Farms farmer's market, which, unlike the greenmarkets, is not operated by the Council on the Environment, has accepted Electronic Benefits Transfers for three years. "I've noticed that over time it becomes more and more frequent. "Over time, I've noticed that the use of EBTs has become more frequent," said Jonah Braverman, urban agriculture coordinator for East New York Farms.

Adding Markets

Making it easier to pay at the market only goes so far. Before they can use the new machines customers have to be able to get to the market in the first place. That called for placing markets in more neighborhoods.

In June 2006, the Mayor's Community Affairs Unit, the Council on the Environmental Affairs of New York City and City Council decided to open 10 new greenmarkets in underserved neighborhoods in the South Bronx, North and Central Brooklyn, and Harlem. All were up and running by that August of that year. Two of the locations are in Harlem, for example, and one on the Lower East Side.

Clearly demands exists in lower income communities for what the greenmarkets have to offer. Most people using the Electronic Benefit Transfer at the market shunned prepared foods. "Eighty-two percent of our EBT sales last year went to fruits and vegetables," said Hurwitz. "We are committed to providing all New Yorkers with the opportunity to healthy fruits and vegetables."

Â

Stated Meeting: Wasting Electronics

After two years and tons of computers strewn to the curb, the City Council overwhelmingly approved legislation that requires manufacturers to recycle certain types of electronic waste.

Though ever member - besides the Republican minority - signed onto the legislation, the City Council is still staged for a fight over the measure with Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who claims it is unconstitutional and plans to veto it.

On other fronts, Council Speaker Christine Quinn was confronted with rare opposition from the body's Brooklyn delegation, which opposed her selection to fill the city clerk vacancy. The council approved former Bronx County Clerk Hector Diaz by a vote of 34 to 16.

Bloomberg Trashes E-Waste

In 2009, when New Yorkers are looking to be rid of that rusty television or outdated Macintosh, they won't have to throw it by the curb -- somewhat guiltily -- knowing that toxins would leak into the soil at some out of state landfill. Under legislation (Intro 104-A) sponsored by Councilmember Bill de Blasio, manufacturers will be required to take back such electronic goods for recycling. The bill was approved at the council's stated meeting on Wednesday by a vote of 47 to 3.

The legislation is rolled out in several stages, with a waste management plan due this year. Manufacturers, like Apple, will be required to take back electronics on a one-on-one basis by July 2009. By 2011, manufacturers will be required to take back orphaned electronics of the same type. Eventually a manufacturer must collect 65 percent of goods that they sell, calculated by weight, or be subject to a $50,000 fine.

The legislation is the first manufacturer-required in the nation, said city officials, and has been endorsed by numerous environmental advocacy groups. The bill covers primarily computers and televisions, but not household appliances, like a washer or dryer.

"I would go down the street and see those computers on the curbside, and it would drive me crazy all the time," said de Blasio. "It felt like the most wasteful situation to begin with."

According to the council, nearly 25,000 tons of electronics are picked up by the city annually. Under this bill, the manufacturer is entirely responsible for the proper recycling of its electronics.

That has raised concerns within the Bloomberg administration. During his radio address on Friday, Bloomberg said he would not enforce the legislation if the City Council overrode his veto, which they have enough votes to do. Bloomberg claimed putting the onus on the manufacturer to recycle is illegal and illogical, since it is usually a wholesaler who sells to the public not a manufacturer.

“We will not enforce it,” he said. “And we don’t have to enforce it because it violates a whole bunch of federal laws on interstate commerce.”

Environmental advocates, though, were quick to contest the mayor's comments. Kate Sinding, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said several other states, including New Jersey and Connecticut, have similar, producer responsible requirements, none of which have been found unconstitutional. Sinding said her group was prepared to do "whatever it takes" to ensure the legislation is implemented, including taking up the issue in court.

Political Patronage

Meetings were delayed for months regarding the selection of the city clerk, whose major responsibilities include keeping city documents, registration of lobbyists and oversight of the city's marriage bureau.

That tardiness was even more evident at the council's stated meeting Wednesday, when many members of the body remained behind closed doors in the basement of City Hall, reportedly debating what borough the city clerk should reside in: the Bronx or Brooklyn?

The most recent clerk, Victor Robles, was from Brooklyn, leading that delegation to lay claim over the position, which is primarily seen as political patronage. Diaz is a former assemblyman and has held the Bronx County Clerk position for 12 years.

Diaz will fill an unexpired term set to terminate in 2012. The position comes with a $185,700 salary.

This dispute, though many members referred to as amicable, is a rare one in the council, leading nearly a third of the body to vote against the selection (Reso 1276) of the City Council speaker.

During a meeting of the Committee on Rules, Privileges and Elections, Brooklyn Delegation Chair Erik Dilan said, "Mr. Diaz, again, it has nothing to do with you. Myself, as well as the Brooklyn delegation, cannot support the nominee."

Quinn said the council would easily move past its disagreement to concentrate on issues of citywide importance, from health care to transportation. The council's division, though, was seen as a loss for Quinn, who must soon rally the body in one direction on congestion pricing, which she supports.

Cleaner Ferries

In addition to the e-waste legislation, the council also approved a bill that requires all city owned or leased ferries use low sulfur emission fuel. The bill, (Intro 168-A), sponsored by Councilmember Alan Gerson, was approved by a vote of 50 to 0.

The legislation will require ferries to switch to the cleaner technology by July. It also mandates the city retire older ferries that do not meet newer environmental standards. Â

Measuring the Garbage Glut

Going green has never been more in vogue. Whether it's concern over climate change or an affinity for organic, pesticide-free products, New Yorkers are eating up the now trendy socio-political movement with a recyclable spoon.

And not surprisingly, our leaders are taking note. Almost every week brings an environmentally friendly announcement from the Bloomberg administration or the City Council. The council last week approved legislation requiring certain large stores and chains to recycle plastic bags - currently not recyclable under the city's system (see related story). Just a week earlier, Mayor Michael Bloomberg put on a green vest, literally, to encourage city dwellers to mulch their Christmas trees.

But though New Yorkers -- private citizens and government officials alike -- can talk the talk, it is less apparent whether we can walk the walk.

Talking About Recycling

When we began designing and researching our Garbage Game, we -- perhaps naively -- did not see the project solely as environmental journalism. In light of the city's long struggle to manage its solid waste, Gotham Gazette staff envisioned the game as a way to demonstrate the problems confronting our leaders as they balance difficult choices, such as saving cost versus reducing asthma.

Now that nearly 3,500 of you have played the Garbage Game, it's time to take a look at what you decided to do with the array of items we gave you and what those results mean. Did you recycle your plastic water bottle, or did you reuse it? Or did you do both?

Overwhelmingly, Garbage Game players took a more "eco-friendly approach," separating refuse from recyclables and minimizing mileage. When it was time for you to play sanitation commissioner, the vast majority of you followed Bloomberg's solid waste management plan -- essentially keeping your garbage local instead of trucking it to less affluent neighborhoods in the outer boroughs.

Sorting Your Trash

So now that you have managed the 64,000 tons of trash the city sees weekly, how do your choices compare to the policies the city has adopted and implemented.

About half of you decided to reduce waste. That is, you said you would not drink bottled water, you swore off disposable diapers or you chose to compost your apple cores in your own back yard -- for those of you who have back yards.

An even greater percentage decided to recycle. About 85 percent of Garbage Game players opted to recycle their junk mail. Interestingly, this compares with the 45 percent of paper that actually is recycled.

Though New York has not implemented its own e-waste legislation -- a bill is currently in the City Council that would require some manufacturers to take back electronics and recycle them -- more than 70 percent of you wanted to either donate your old cell phone to charity for reuse or drop it off at one of the occasional recycling events sponsored by the Department of Sanitation.

Some 8,000 New Yorkers brought 311 tons of electronics to these drop off events in 2006.

Though it is not unusual for New Yorkers to identify recycling as a good practice -- one Department of Sanitation marketing study from the late 1990s shows that more than 95 percent of residents think recycling can make a difference in their neighborhood -- some environmental and solid waste management advocates say New Yorkers do not always put that thought into practice.

"I think that's probably the majority viewpoint," said Laura Haight of the York Public Interest Research Group. But, she added, "What (New Yorkers) actually do is different from what they know. It's not uncommon for people to (just) say they recycled."

The city has approximately a 17 percent diversion rate for recyclable materials out of a possible 36 percent. That means that more than half the materials that could be recycled - from plastic jugs to soup cans - instead are thrown out with the rest of the trash.

Some environmental advocates and experts attribute this disparity to education. David Hurd, the director of the Office of Recycling Outreach and Education at the city's Council on the Environment, said there is a genuine eagerness among New Yorkers to recycle, but there is also confusion over what should or shouldn't be included in bins at the curbside.

"What we're finding out from the neighborhoods we work with is there are common areas of confusion," said Hurd. "New York City only accepts plastic bottles and jugs. People can't get it through their head that a yogurt container is not a bottle or a jug."

Gotham Gazette recognizes, as do most advocates who commented on our game's results, that our particular subset of readers might not be representative of the New York City population as a whole. On solid waste, actions, opinions and awareness vary throughout the city. For instance, according to report by the Department of Sanitation, certain neighborhoods in the Bronx recycle only about 9 percent of their waste, while neighborhoods on the Upper East Side have a diversion rate of approxiamtely 31 percent.

Thus, our results in no way accurately reflect the whole city's stance on waste management -- just that of readers and players like you.

Playing Commissioner

Where Garbage Game players and the Bloomberg administration differ most drastically may be when it comes to the approximately 50 percent who chose to reduce the waste stream entirely. Bloomberg can't really give New Yorkers that option - imagine if the city banned Huggies. It might not go over well.

Where you seem to agree, however, is in the distribution and management of this nearly unimaginable amount of waste. About 73 percent of you decided to truck your garbage locally and keep it out of neighborhoods that were once overburdened by most of the city's trash - areas in the Bronx and in Brooklyn. Local waste management is a crucial element of the mayor's solid waste management plan, which was approved by the council in 2006 and is currently being implemented.

Instead of trucking garbage across the city -- blanketing neighborhoods with diesel fumes and garbage garages reeking of waste -- the city decided to make every borough responsible for its own trash, at least in theory (see related story). The plan also relies on other modes of transportation besides trucks. The Bloomberg administration and the environmental community agree that using rail or barges is a cleaner way to transport material.

After you decided to truck your garbage to a local transfer station, about 90 percent of you moved to then transport it to a larger citywide center via barge. About 70 percent of Garbage Game players also opted to locally process the city's recyclable materials , thus reducing the amount of carbon emissions from transporting materials long distances across the country or to Asia. As a runner-up, players picked transporting recyclable raw material via railroad.

Some environmental advocates saw our unscientific results as a boost to the mayor's plan, which was mired in controversy for two years and required a considerable amount of wheeling and dealing at City Hall. The plan, said New York League of Conservation Voters Executive Director Marcia Bystryn, is an example of utilitarianism: Though one neighborhood or one individual has to make sacrifices, it's for the greater good.

"What I find very appealing and reassuring is that people, once they familiarize themselves with the options of solid waste management, understand the wisdom of the solid waste management plan," said Bystryn. "A critical issue is air emissions: The current system is heavily reliant upon truck traffic. It's not good for our air. It's not good for the climate."

While many of you agreed about how our non-recyclable refuse should get to its final destination, it was a toss-up for what that final destination should be. We gave you the options of land filling or incineration - the two least popular choices despite the fact that is currently where the city sends our trash - as well as sending refuse to a waste to energy plant or a materials recovery facility.

Players were split between the latter two: About 43 percent opted for a materials recovery facility, while 45 percent chose a waste to energy plant. Neither of these options are under consideration by the current administration, though they have been debated in the past.

A materials recovery facility -- one is used with mixed results in Chicago -- would send refuse and recyclables to one location, where they would then be sorted. Supporters of such plants argue more recyclables would be diverted from the waste stream because professionals would sort the trash. Others argue by lumping all of the materials together, some recyclable materials will unavoidably be contaminated -- that newspaper would be soiled by a leaky carton of spoiled milk - thus making the material less valuable for resale in the recycling market.

A recycling station slated for Sunset Park -- part of the mayor's management plan -- is a materials recovery facility, city officials said. It would sort jumbled recyclable materials, though it would not receive other types of trash.

On the other hand, waste to energy plants have also had varied success across the country -- one on Long Island powers the community it serves and adjacent homes. Once thought dangerous and dirty, some advocates say the technology has been cleaned up and should again be considered a viable option.

One player wrote us the following after gaming with garbage: "Energy-from-waste needs to be further explored as new technology and increasingly stringent emissions guidelines have allowed the industry to gain positive acceptance worldwide, and yet the U.S. continues to rely heavily on land-based disposal, and the last time I checked, they weren't making more land."

Touché gamer, touché.

Counting Cost

One of our most consistent complaints from players and readers was that we didn't provide a measurement to compare your results against how the Department of Sanitation manages waste.

Given the options we offered -- such as obliterating water bottles from the waste stream entirely, forcing parched New Yorkers to the tap -- these figures are difficult to accurately and fairly compare. But, we will provide you with some examples.

When following the game's most popular choices, which included eliminating diapers, food scraps and water bottles completely from the waste stream, a player would design a garbage plan that cost the city approximately $104.6 million. That cost can be attributed to the vast reduction in the total amount of waste or recyclables.

Using figures from the Independent Budget Office on the cost of disposing refuse and recyclables as well as factoring in how much the city earns from selling this raw material, the city spends $268.9 million. That number inlcudes only the items in the game: water bottles, food waste, cell phones, etc..

Taking these figures into account, it becomes clear the cost of waste management decreases with the reduction of the waste stream. City Hall, though, cannot force New Yorkers to start using their junk mail as grocery lists nor can they make parents use cloth diapers (Some gamers were discouraged that we didn't include the option of not having children at all. "The most environmentally conscious thing I can do is not procreate," wrote one player.)

Beyond reduction, what is apparent, according to figures from the Department of Sanitation, is cleaner solid waste management is more costly. According to an economic analysis of the mayor's solid waste management plan, the old system - which used diesel trucks to transport recyclable and refuse materials across the city and country - cost the city about $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2005. The new system following complete implementation would increase to $1.45 billion.

Grinding Garbage

Our project tapped into the emotions and policy persuasions of some, who commented, on our site and elsewhere, on the seemingly impossible task of reducing and managing New York City's waste.

The most substantive criticism the game received came from the Neighborhood Retail Alliance blog which faulted us for offering composting as the only way to cut back on the amount of food waste going to landfills. Instead, the blog wrote, the game should have allowed players to opt for food waste disposals -- those machines that let you dump your garbage down the drain and cover your ears as it is ground up and sent to the city's sewage system.

The game did not include this option partly because of concern about whether disposals would overload the city's already overtaxed sewage system and because they seem just barely on the radar here.

But they are a choice. The city lifted the ban on the disposals in 1997. In a comment on the Wonkster posting on the grinder debate, Kendall Christiansen, a spokesman for a company that makes disposals, observed that the city's Department of Environmental Protection had determined that the grinders' "public benefits significantly outweighed their de minimus impacts (and that was before Fresh Kills closed)."

Whatever interest Christiansen has in the issue, some environmentalists have backed the use of disposals at least in conjunction with a recycling program. Like them or not, though, they remain rare. Even the Neighborhood Retail Alliance concedes residential disposals are few and far between. But, it continues, that is not due to their inherent shortcomings, but because their "use is optional and no one pays for their garbage removal. If folks paid a disposal fee, you can bet that this would change pretty quickly."

A Never-ending Pile

We have received ample criticism and praise for the Garbage Game, from Sanitation Commissioner John Doherty to readers like yourself. And just because some of you have demonstrated that you're environmentally well-versed, that doesn't mean the city will recycle more or that policy and political challenges will no longer be dumped in our laps.

Take one gamers account: "I am a retired sanitation superintendent and enjoyed the challenge of this game. We had the same problems in 1989... It is a never ending problem."

As the city continues to grapple with how to deal with the billions of pounds of trash generated here annually, we will continue to keep our eyes, and noses, on growing or shrinking policy options.

Â

Recycling Stops and Starts

Some New Yorkers empty their garbage cans and heave their plastic bags onto the street never to think of the contents again. But the more than 3 million tons of trash generated in the city annually from Sunnyside to Morningside Heights does not evaporate as soon as it is tossed into the back of a white sanitation truck.

And just like our solid waste, the debate over the city's solid waste management policy is hard to get rid of.

It may have been more than a year and a half since Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed the new solid waste management plan into law, but debate continues, and much remains unresolved.

Politicking upstate has stalled the full implementation of the mayor's plan, and, beyond that, the administration has just sparked a debate over the city's two-decade old recycling law by submitting some revisions to the City Council. The move has already brought slight retaliation from environmental groups, who fear the law does not do enough to advance recycling.

Following the release of our Garbage Game in November and the analysis of our results (see related story), we have some garbage-based issues to catch up with. Here are a few.

Recycling on the Hudson

The solid waste management plan was approved in the summer of 2006 after years of back and forth between residents, council members and environmental groups. The city's truck-based system - which sent our garbage to the outer boroughs in Department of Sanitation white dump trucks - had become the bane of several communities.

The 2006 plan was supposed to tackle that. By creating a system of marine transfer stations in every borough, not only would neighborhoods that had been saddled with the waste burden - like areas of the Bronx and Brooklyn - be able to breathe easier, but Manhattan would finally be responsible for its contribution to the waste stream, environmental advocates said.

The plan calls for a recycling center off the Gansevoort peninsula near 14th Street, which would serve as both an education center and collection site. The site, supporters say, neatly fits into the administration's attempt to convert the truck-based system into a rail or barge based one, reducing toxic fumes.

But the center hit a snag upstate. Because the facility would be located in Hudson River Park, the state legislature must pass, and the governor must sign, an amendment to the act that created the waterfront esplanade. Three Manhattan assembly members, Deborah Glick, Linda Rosenthal and Dick Gottfried, have blocked that measure in Albany.

Environmental advocates claim the stall is an example of NIMBYism. "It's the give and take of Albany politics," said Marcia Bystryn, the executive director of the New York League of Conservation Voters. "No one ever wants a garbage facility in their neighborhood... That's not just a transfer station. That's anything to do with sanitation."

Glick, though, argues that the city could find a more appropriate site. According to a position paper, she opposes the Gansevoort center because it would replace valuable parkland, and she argues there are alternative locations, like Pier 76 near 36th Street, that would be more suitable.

Late last year, environmental groups, City Council members and Bloomberg all lobbied Albany to push through the amendment. But some political observers say, that was not enough to counter Glick's alliance with Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver.

A spokesman from the mayor's office said the administration was "hopeful" the amendment would be approved in the current legislative session, which began last week. When asked what the administration would do should the amendment not move in this session, the spokesman repeated the administration's positive outlook.

Recycling Everywhere

The history of recycling in New York City may be even more tumultuous than the history of solid waste generally. Over the past 20 years or so, recycling has started and stopped, and increased and fallen in popularity.

Some of this has been fought out in the courts. When the city first approved a recycling law in 1989, it set the benchmarks the city would aim for every year in total tons rather than as a percentage of waste collected. Because the city overestimated the amount of solid waste residents would produce, city officials said, it was unable to meet these goals.

As a result, the Department of Sanitation faced lawsuits brought by the Natural Resources Defense Council, residents and council members, who wanted to compel the city to meet its tonnage requirements. In the latest of those suits, a State Supreme Court judge ruled the benchmarks were "simply unattainable," sparking a revision of the law.

A bill ( Intro 668) revising the city's recycling law was introduced at the City Council in December and thus far has received little attention. As negotiations between the city and local stakeholders continue, the debate could heat up.

"Now, at least theoretically, everyone is on the same page," said Eric Goldstein, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. "The city has come out with an initial draft that is an attempt to revise the tonnage benchmarks, and I think the environmental community and solid waste experts have some additional ideas on how best to reform the legislation."

Already some advocates claim the proposal weakens the city's recycling tonnage requirement. Under the 1989 law, the city must recycle 4,250 tons per day. Under the new legislation, those benchmarks are put into percentages, from an 18 percent diversion rate in July to a 25 percent diversion rate by 2016. Currently, the city's recycling diversion rate hovers at about 17 percent.

The mayor's solid waste management plan outlines a detailed explanation for the need to turn the benchmarks into percentages and for the need for "adaptive" and "realistic" goals that can fluctuate with the waste stream. A 25 percent diversion rate is set out specifically.

Advocates and environmentalists say the law's revision does not further the city's recycling program. "We will have a counter proposal on the mandatory tonnage requirements as well as additional provisions for enhancing the effectiveness of the city's program more comprehensively," Goldstein said.

Â

Bagging Plastic Pile-Ups

Every time you leave your home, you usually return with at least one plastic bag, which is then destined for two places: To join the other dozens accumulating under your kitchen sink or the trash.

But under a new bill approved by the City Council on January 9, you will have another way to dispose of these notorious nuisances. You will be able to drop them off at large stores or chains throughout the city, which will be required to recycle them.

Paper or Plastic?

Pushed through the City Council in a little more than two months, the plastic bag legislation ( Intro 640) will require stores larger than 5,000 square feet or chains with more than five locations in New York City to take back the plastic bags. The legislation was approved by a vote of 44 to 2, with council members Vincent Ignizio and Dennis Gallagher dissenting.

The legislation, introduced by Councilmember Peter Vallone Jr. and Council Speaker Christine Quinn, received support from supermarket and business associations and environmental groups as well as plastic bag manufacturers. In addition to the plastic bags, the recycling bins could also accept other plastic film, such as bags from dry cleaners. Stores will have six months to comply with the bill, which mandates that pharmacies, grocery stores and other large businesses keep collection bins for recycling in visible locations and also requires they sell reusable, cloth bags.

"Shoppers that faced the paper or plastic conundrum now have a new option -- cloth," said Vallone.

Stores will be required to contract with recyclers, who can use the bags to make plastic furniture, new bags or even decks. Plastic bags make up about 2.73 percent of the overall city waste stream, or about 91,830 tons a year, according to the Department of Sanitation. It is estimated that New York City residents use 1 billion plastic bags annually. Nationwide estimates are about 84 billion bags a year.

Plastic bags are not included within the city's recycling program, because they are made of a blend of plastics and are consequently hard to handle.

Under the legislation, the plastic bags provided at stores would have to have messages encouraging the shopper to return it to a participating location.

Since the bill's introduction, several changes, including a drastic reduction in the proposed fines, were made. When first introduced , the bill carried a $2,000 a day fine for noncompliance. Under the approved version, the fines were decreased to $300 a day. The changes were presumably made to compromise with the supermarket industry.

Quinn said if compliance is not as high as the council expects, it can always revise the law.

Though advocacy and business groups eventually sided with the council and supported the legislation, it took some bargaining, said Pat Brodhagen, vice president of public affairs for the Food Industry Alliance. The group, said Brodhagen, had no objection to recycling plastic bags. In fact, she noted, several of its members already do so voluntarily. But, she added, the original fines were exorbitant.

"I think we successfully argued these fines were out of proportion," said Brodhagen. "Now, we say we can and will do this."

Though the financial impact on businesses is expected to be small, according to Quinn, that did not stop one council member from voting against the legislation for that reason. Gallagher said, "I received some complaints from local businesses.… It's government taking a step I don't agree with."

An Extra Week

The City Council also approved legislation (Intro 675 ) extending the deadline by one week for Mayor Michael Bloomberg to submit his preliminary budget proposal. The budget must now be in by Jan. 24. Â

An Environmentalist's Wish List for 2008

The start of the New Year presents us with a great opportunity to take stock of the old year and to plan for the new. It's also time to make some wishes.

2007 brought some game-changing environmental events in New York. Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced PlaNYC2030, which set out to bring greenhouse gases and congestion pricing to the city. Governor Eliot Spitzer released his proposal to implement the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a multistate effort to reduce carbon emissions to 13 percent below 1990 levels by 2019. The state legislature passed, and the governor signed, the New York Ocean and Great Lakes Ecosystem Conservation Act, a new law that, for the first time, requires agencies to work together to promote the sustainable use and protection of New York’s ocean and Great Lakes ecosystems.

There are a ton of details and work to be done to implement all of these programs (and others that I didn’t mention). But New Yorkers can be thankful that their city and state took such major steps.

AND NOW WHAT?

Much remains to be done. So, as we head into the new year, here is my list of wishes.

PlaNYC 2030

While the wish list extends beyond PlaNYC2030, the mmayor’s incredibly ambitious proposal with 127 different housing, transportation, energy, open space and other initiatives still offers a fine starting point. Most of the goodies in it don’t require Albany's approval to move forward. But the cornerstone of the plan is congestion pricing -- charging people to drive into or around parts of Manhattan during the workweek. Implementing this system will be important to reduce traffic, improve air quality and raise funds for critical transit infrastructure investments throughout the region. And, if it works here, congestion pricing is likely to be adopted in other cities that are struggling with increased traffic and unmet infrastructure needs. Congestion pricing, though, does require approval in the state capitol as well as by the City Council.

My 2008 wish: The city and Albany should cut their deals, make their compromises and enact a congestion pricing plan emerges that raises even more net revenue for transit improvements than the mayor’s original proposal.

Transit Funding

If New York City gains another million residents, as the 2030 plan anticipates, it will need the transit infrastructure to get them around the city. And that means more than the East Side Access for the Long Island Rail Road riders, the Second Avenue Subway and the extension of the 7 lines -- as important as all three projects are. It means more service for all five boroughs — service and service that reflects the development patterns of the future, rather than the commuting patterns that existed decades ago when the IND and IRT were built. It also means fixing the chronic under-funding of the system from Albany (we have 84 percent of the state’s transit riders, but get only 63 percent of the state transit funding).

My 2008 wish: In addition to implementing the congestion pricing program, the city and the state shouldwill find ways to increase their funding contributions to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s five-year, $32 billion capital program that will be presented next March. And I hope that they do it in a way that doesn’t add more burdens to the already taxed (in more ways than one) straphangers.

E-Waste

Old televisions and computers contain a slew of toxins (including lead, mercury and cadmium) that should never get buried in landfills or burned in incinerators. But the city’s current electronics recycling program requires people to lug their electronics to odd locations on random days. No wonder most New Yorkers throw this stuff in the trash.

My 2008 wish: The city should adopt Intro. 104, the “Electronics Collection, Recycling and Reuse Law,” which would require manufacturers to take certain electronic products back for recycling after consumers are done with them. Not only would this help take toxics out our waste stream, but it also will save money for the city by reducing the burden on the city's Department of Sanitation and keeping some garbage out of landfills.

Stormwater and Sewage Overflows

Every year, roughly 27 billion gallons of untreated sewage gets mixed with stormwater runoff, and ends up bringing pathogens and other pollution into the city’s waterways. These combined sewer overflows put the public’s health at risk, damage our marine ecology and frequently make our waters unsuitable for recreational activities. Over the long haul, PlaNYC 2030 boldly aims to remake the urban landscape by keeping sewage and polluted stormwater out of our waters. But, in the short run, we need legislation to help us reach this goal.

My 2008 wish: The City Council should pass three bills (Intros. 628, 629 and 630) that, collectively, would help ensure that future administrations follow through on PlaNYC 2030’s ambitions. Together, the bills call for a sustainable stormwater plan for each of the city's waterways; mandate that new city capital projects use environmentally friendly technology and take stormwater issues into account; and require trees to be planted to help absorb stormwater before it goes into the sewage system.)

Jamaica Bay

One of the great things about New York is its proximity to amazing outdoor environments. Here’s a great example: Jamaica Bay, home to the only federal wildlife refuge accessible by subway, sits right under the flight path to Kennedy airport. This gem hosts nearly 20 percent of North America’s bird species each year, along with an amazing array of fish and shellfish. But Jamaica Bay is jeopardized by water pollution — most dangerously, nitrogen pollution from four city wastewater treatment plants.

My wish for 2008: Six years ago, the stars aligned to create an ambitious pollution fighting plan for Long Island Sound. The state Department of Environmental Conservation should adopt a comparable plan to protect Jamaica Bay for generations to come.

And one final wish: As environmentalists and other concerned New Yorkers work for these goals, may we all have a safe, clean, green and great 2008.

Rich Kassel, who writes Gotham Gazette's environment page, is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization and blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard.

Because of a typographical error during editing, this article originally had an incorrect number for the MTA capital programs. The correct amount for the five-year program is $32 billion. Â

Is 'Nalgene' Hazardous to Your Health?

Earlier this month, Mountain Equipment Co-op, the "REI of Canada," pulled its Nalgene bottles from its shelves, citing concern over potential health risks. It seems that those iconic bottles (Neat colors! Cool graphics! Originally used in laboratories!) that are ubiquitous in backpacks, dorm rooms and office refrigerators are made of a type of plastic that has been linked with infertility, lower sperm counts, enlarged prostrate glands, pre-cancerous lesions in breast and prostate tissue, and other symptoms of hormone disruption.

How many New Yorkers carry a Nalgene bottle with them wherever they go because they want a reusable, environmentally preferable alternative to bottled water? How many New Yorkers carry a Nalgene bottle for their children wherever they go because they fear that softer plastic baby bottles will leach hormone-disrupting phthalates, especially when filled with acidic juices? How many New Yorkers carry a Nalgene bottle wherever they go, just because the bottles are nearly unbreakable and are really colorful?

And, reading this now, how many New Yorkers suddenly feel like Charlie Brown does, whenever Lucy pulls the football away from him, one more time? Like Charlie Brown, how many Nalgene-carrying New Yorkers will learn about this latest health risk and want to shout â€Aaaarrrrggghhhhh!"

The Polycarbonate Problem

Before you fill your Nalgene bottle with cement and jump in the Hudson River, here are some basics:

Most Nalgene bottles are made from polycarbonate. (You can distinguish polycarbonate from other plastics because the polycarbonate bottles have the number 7 in the little recycling triangle on the bottom). Polycarbonate is a form of plastic that is comprised mostly of bisphenol A (BPA), an endocrine disruptor that mimics the female hormone, estrogen. In animal studies, BPA has been associated with the abnormalities listed above, as well as with obesity and insulin resistance – a condition that commonly precedes the development of diabetes. If all that wasn't bad enough, BPA also has been shown in animal studies to cause changes in behavior. (Could it have been his Nalgene bottle -- and not the steroids -- that caused an enraged Roger Clemens to throw a broken bat at Mike Piazza during Game 2 of the 2000 World Series?)

Not surprisingly, industry-funded studies have failed to find these same effects. And, the jump from animal studies to human impacts is an imperfect one, so there is a lot of controversy around the toxic effects of BPA. Although we can't say with certainty that BPA causes the same problems in humans as it does in the laboratory animals, the weight of scientific evidence should prompt us to err on the side of caution and avoid BPA exposures where possible.

We also know that more than 90 percent of the general population carries residues of BPA in their bodies. How is that possible? After all, not everybody drinks from Nalgene bottles. But the BPA chemical is ubiquitous. Epoxy resins containing BPA line the cans of tomato sauce and leach into the sauce, thanks to the acidity of the tomatoes. It lines the insides of your Coke and juice cans—whoops, there's that acid-enhanced leaching again. Canned fruits? Yup, you'll find BPA in those cans too. Here are some other BPA sources: the insides of the cans of infant formula, some dental sealants and even that polycarbonate pitcher that came with your Brita filter.

What You Can Do

Eliminating exposure to BPA is probably close to impossible, given its ubiquity. But reducing exposure to this chemical makes sense, especially for children (their developing bodies are especially prone to the health impacts of endocrine disruptors like BPA). Avoiding polycarbonate bottles is one step in reducing exposure to endocrine disruptors. (An important note here: Although Nalgene has become the "Kleenex" of the polycarbonate world, all polycarbonate bottles contain BPA, so you should avoid bottles with that little "7" in the recycling triangle, whether they come from Nalgene, Starbucks or your Brita filter system.) If you use these bottles, recognize that high temperatures (e.g., your dishwasher), acidic liquids (e.g., juice), and any discoloration or cracking due to age are all likely to increase BPA leaching.

There are better options for storing drinks: an unlined stainless steel container (e.g. Klean Kanteen) or another type of plastic container, such as polyethylene or polypropylene, which doesn't contain BPA. (Look for the number 1, 2, or 5 in the recycling triangle on the bottom of the container.)

Second, recognize that more of our collective exposures are likely to come from BPA in cans especially if the contents are highly acidic such as a tomato-based product or soda. San Marzano tomatoes may be the best for cooking, but buying them in glass or those milk carton-like boxes will keep BPA out of the sauce. Likewise, canned pineapple may have been the only way to eat that fruit when we were kids, but now buying fresh is the BPA-free way to enjoy it.

Want to find out more? The Environmental Working Group, California, and a group called Environmental Defence in Canada all have good information on their websites.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization, and is on the boards of the New York League of Conservation Voters and Transportation Alternatives. He blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard at http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/rkassel.

Â

Breathing Easier in 2030 and Beyond

(This is the last in a three-part exploration of some key air pollution issues in New York. To read the earlier columns click here and here.)

Almost a year ago in Queens, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the outlines of his sustainability plan. He presented a great slide show, and one of the highlights came when the mayor contrasted the current state of our air – we fail to meet federal air quality standards for ozone and particulate matter — with his goal of enabling every New Yorker “to breathe the cleanest air of any big city in America.” (Another highlight was seeing the amazing panorama of New York City at the Queens Museum of Art, where the event was held. If you’ve never seen it, you’ve got to go.)

But what did Bloomberg’s pledge really mean? Air quality has improved in the city over the years, and some of the worst air quality in the nation isn’t in the big cities: California’s Bakersfield, in the San Joaquin Valley, is home to the second-worst particulate pollution and the highest ozone pollution in the country, despite its complete lack of skyscrapers.

Even if the city were to do nothing, the air should keep getting cleaner, thanks to the implementation of federal programs to reduce pollution from cars, trucks and construction and farm equipment.

But one problem with federal programs is that they are very good at reducing pollution from some sources (especially vehicles, since the fleets turn over relatively quickly), but not so good with others, like power plants (thanks to loopholes that allow power plants to be modified without being cleaned up).

An even bigger problem may be that federal programs don’t focus on what happens when you combine millions of pollution sources in the same place, like New York City. In most cases, a new car will be much, much cleaner than the old car it replaces. But if you put 2 million cars on the same island, that island will have a lot of pollution.

HOW WILL PLANYC 2030 IMPROVE OUR AIR?

PlaNYC focuses on particulate pollution because it has the most serious health impacts and because New York, by the administration’s own admission, lags other big cities in programs to control it. According to the mayor’s plan, more than half of the particulate pollution (regulated as “PM2.5,” or particles less than 2.5 microns in diameter; about 1/60th the width of a human hair) we breathe is beyond the city’s reach. It’s governed by federal standards, blows in from states to the west or both. PlaNYC 2030 defines “clean air” in terms of the amount of fine particulate pollution per square mile—a neat metric to figure out how to compare the apples and oranges of pollution in New York City with its smaller brethren. To have the “cleanest air of any big city in America” (currently, Philadelphia and Dallas are the title holders), the officials estimate New York City needs to cut local particulate pollution by 39 percent per square mile.

PlaNYC 2030 includes a basket of strategies to achieve its 39 percent particulate reduction—split between buildings (23 percent) and vehicles (16 percent).

Interestingly, many of these strategies also will help achieve other goals in the plan. For example, implementing the city’s energy and global warming proposals for buildings will cut particulate pollution by 6 percent citywide. Switching to more efficient power plants that burn natural gas or biodiesel blends will add another 17 percent reduction. Together, these steps will hit the city’s 23 percent reduction target for particulate pollution, and play a major role to reduce global warming pollution in the city by 30 percent.

Cleaner Heating Oil

Here’s a simple step in the plan that makes so much sense that it’s hard to believe that it hasn’t happened on its own: reducing the sulfur content in home heating oil from today’s 2,000 parts-per-million to the 500 parts per million that is already used in most construction equipment. This would improve the efficiency and reduce the maintenance needs of the city’s boilers and reduce citywide particulate pollution by 2.5 percent.

Cleaner Transportation

Transportation has its share of win-win ideas too. For example, the city estimates that waiving the city’s sales tax on hybrid cars would reduce global warming pollution by 1 percent and reduce particulate pollution by 3 percent by 2030. This assumes 10 percent of the cars will be hybrids by2030, a pretty conservative assumption. Various elements of the transportation plan – not just congestion pricing in Manhattan but also improving the fuel efficiency of taxis and other for-hire vehicles, and cleaning up diesel trucks and buses -- each add significantly to the total. Of this list, retrofitting or replacing the school buses and sanitation trucks that ply every neighborhood should make a fast, significant difference in community-level air quality.

On the other hand, some of these programs cost significant money and are not under the mayor’s umbrella. For example, it’s a great idea to propose that the Port Authority clean up its ferries, but somebody has to pay the $75,000 to $90,000 per engine to accomplish that. The airports all contribute to local air pollution, but it’s up to the Port Authority and the Federal Aviation Administration to OK any program to cut emissions there. Retrofitting diesel trucks may be the most cost-effective idea in the whole plan: Every dollar of diesel retrofit yields more than $12 in health benefits, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Experience in other states, though, suggests strongly that private trucking firms will not invest without some public funding. California and Texas each have public funds of more than $100 million a year to fund these projects, but a similar fund for New York is not on the political radar screen yet.

MAKING IT HAPPEN

So what’s the bottom line? We can’t eliminate air pollution entirely, so aiming to have the cleanest air of any big city is the right target. PlaNYC is comprehensive, pragmatic and feasible, but implementing it will not be easy. That will require consistent advocacy and attention at every level of government. Some ideas, such as lowering the sulfur levels in home heating oil, are no-brainers but have not happened yet. Others – cleaning up city school buses, for one -- make a lot of sense but require more political will and funding than they ever have had. And, finally, the third set of ideas, including lowering ferry and airport emissions, require political leadership that goes far beyond the city.

PlaNYC 2030 lays out a good roadmap of how to ensure that the city’s air continues to improve. Despite the progress in asthma hospitalizations reported on last month (and thanks to all of you who commented on this piece), New York City kids continue to face asthma rates that can be more than double the national average. The city still fails to meet the federal pollution standards for particulate and ozone pollution. Our work is just beginning.

Want to learn more about the plan? Check out the city’s October 22 status report.

Rich Kassel is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), where he focuses on urban air pollution and transportation issues. He also chairs the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a regional transportation advocacy organization, and is on the boards of the New York League of Conservation Voters and Transportation Alternatives. He blogs on a variety of environmental issues on the NRDC Switchboard at http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/rkassel. Â

Bagging Plastic Bags

It's the same situation for many New Yorkers. Lurking under your kitchen sink is a growing, almost uncontrollable number of plastic shopping bags. The environmentally conscious city dweller habitually hoards bags, because here, as in many places across the city and state, the bags are not recycled.

Now the City Council is aiming to reduce that accumulating pile. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Councilmember Peter Vallone have introduced legislation that would require stores larger than 5,000 square feet to recycle plastic bags.

In addition to the plastic bag bill, members introduced several other pieces of legislation throughout October, from broadening the definition of tenant harassment to limiting engine idling.

Piling Up Plastic Bags

Plastic bags have not traditionally been recycled, because – unlike plastic water bottles - they are a blend of several plastics and are so relatively hard to handle. In fact, only 4 percent of bags are recycled in the country as opposed to 25 percent of plastic bottles.

Under the council's proposed legislation (Intro 640), stores over 5,000 square feet would have to provide large bins for reusable plastic bags in a visible place near the front of the store. They would also be required to use plastic bags that state, "Please return this bag to a participating store for recycling," and to also offer reusable bags for sale.