Garbage

A large white garbage truck parks next to a 20-foot-high mountain of trash in the South Bronx. The truck's rear hatch opens, and ten tons of waste pours out -- a heap of black plastic bags, brightly colored crushed toys, pieces of furniture.

This is Harlem River Yard, one of some 100 "transfer stations" in the city where some 1,100 such trucks deliver 11,000 tons of waste generated by residents, public agencies and non-profit corporations every day. Getting rid of it costs the city almost $3 million a day, nearly a 40 percent increase from five years ago. Private carters handle the garbage generated by businesses, including restaurants -- another 13,000 or so tons per day.

For years, city officials have wrestled with what to do with all of this trash. In the 1940s, the city opened Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island. Even thought Fresh Kills was supposed to be only temporary, most garbage went there for 53 years. But in May 1996, Governor George Pataki, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and Staten Island Borough President Guy Molinari announced a plan to close Fresh Kills.

Other articles in this series:

|

The Giuliani administration then proposed placing the garbage on barges and shipping it to Linden, New Jersey. From there, it would have been loaded on trains and shipped to out-of-state landfills. But the plan was sidelined by charges of corruption in Linden.

Since then the city has struggled, without much success to find an economical, environmentally sound alternative.

Today, city sanitation trucks take most garbage to one of the privately owned transfer stations such as the one in the South Bronx. There, inside a 60,000 square-foot warehouse, compacters -- heavy machines that resemble bulldozers -- ride over the garbage so that it takes up less room. As these machines work, mist drifts from the ceiling to keep the dust level down.

More than half the city's transfer stations are concentrated in a few low-income areas, such as Red Hook, Greenpoint, Williamsburg and Sunset Park in Brooklyn; Hunter's Point and South Jamaica in Queens; and the South Bronx. Truck traffic clogs the streets in those communities, and residents complain of pollution from diesel exhaust.

"These land-based transfer stations are poorly regulated," said Ramon Cruz of Environmental Defense, a non-profit organization. "And they are very close to residential areas where poor people and people of color live. This is the environmental justice issue within the city."

More than half the garbage processed in the Bronx -- some 3,300 tons -- comes from other boroughs, according to Jaime Rivera, director of South Bronx Clean Air Coalition. "We are not going to take it any more, not even one more pound," he said.

To reduce truck traffic and better distribute the transfer stations, Mayor Michael Bloomberg last year proposed hauling the trash to marine-transfer stations in each borough. These facilities used to load refuse on barges for shipment to Fresh Kills. In the post-Fresh Kills era, the garbage would be put in containers, placed on barges and later sent by ship or train to its final destination. But earlier this year, a Sanitation Department deputy commissioner told the City Council that opening the marine-transfer stations would cost about $400 million, much more than the original estimate of $240 million. The department also now says that rebuilding the transfer stations will take far longer that had been anticipated.

Despite all this, Bloomberg says he has not abandoned that idea. But earlier this month he admitted little progress had been made on his plan. And administration officials said they were seeking alternatives. A consultant will review a variety of schemes, the New York Times reports, including sending the trash to the Caribbean or using a new technology that burns the trash at an exceedingly high temperature to convert it into natural gas and a stone-like material.

Most environmentalists had supported the plan for using marine-transfer stations. “We think it is environmentally better because you are less dependant on heavy-duty trucks with diesel engines,” said Cruz at Environmental Defense. “Reopening of the marine system or rail, or a combination of both, would be much better [than the current system]. ”

For now, however, the city still depends on facilities such as the Harlem River Yard. There, heavy machines called wheel loaders push the compacted trash toward rail cars. Machines called grapples pick up the garbage and drop it into rail cars. Every day, a train of about 35 of these rail cars leaves the Harlem Yard, packed with garbage and heading to a landfill in Waverly, Virginia, about 400 miles away. Waste Management owns and operates the landfill, as well as four other transfer facilities in the city. Except for Harlem Yard, all the transfer stations ship waste by truck.

Of all the city trash, about 19 percent ends up being burned in incinerators that produce energy. The rest is destined for landfills, virtually all of them out of state. The private owner of the transfer station -- not the city -- decides where the garbage will go and pays the costs for shipping it there.

Fees for getting rid of the garbage -- so-called tipping fees -- rose sharply during the 1980s but have stabilized some since then. And they vary widely -- between $10 to almost $100 a ton -- depending upon the location and the method of disposal. Whatever the fees, the city has no choice but to pay.

New ideas and technologies are coming along, but the basis of solid waste management -- dump or burn -- remains unchanged. The city instituted recycling in the 1990s and then partly suspended the program in 2002 because of its fiscal crisis. This July, the city partly restored recycling, and it is now accepting proposals from private companies to resume a full recycling program next spring.

But this may not be enough, some experts say. "The city needs structural changes for waste management," said Benjamin Miller, author of the book, "Fat of the Land: The Garbage of New York -- The Last Two Hundred Years. "It's absolutely critical to have an overall plan. We cannot just keep on doing things, ad hoc, one step at a time."

Water

New York City's water supply system has been called a marvel of engineering -- the eighth wonder of the world. It covers some 2,000 square miles, runs as deep as 1,100 feet underground and supplies as much as 1.5 billion gallons of water per day to more than nine million people.

Other articles in this series:

|

But even at the earliest stages of its journey -- as water trickles down the face of the mountains of the Catskills -- the people in charge of New York's water supply worry about its quality. As these trickles gather momentum and join together into streams, the city's scientists are right there serving as monitors, looking for heavy algae growth and other signs of pollution, including microscopic animals that can cause stomach problems and diarrhea.

Before 1842, New York's water supply consisted of a single fetid pool in lower Manhattan, and water-born disease was common.

Now, after the water flows from hundreds of small Catskill Mountain streams and the Delaware River into 19 upstate reservoirs, it is naturally filtered by rocks and soil. Once it reaches the reservoirs, it is allowed to sit for a while. That is so that impurities in the water can settle to the bottom.

From the reservoir, water is discharged into the city's aqueducts. The New York City Department of Environmental Protection must check the aging upstate aqueducts for leaks. In June, the city sent an unmanned submarine to inspect a damaged 45-mile stretch of the Delaware Aqueduct. Results from the submarine's 16-hour photographic journey are still being studied, but according to officials, the aqueduct has at least two known leaks that spill as much as 36 million gallons of water a day.

The water that does get through then enters the city distribution system. Most cities filter their water at this stage of the process. But New York does not.

"The water that comes into New York City aqueducts is frequently of superior quality than filtered systems, but it also makes it very fragile," said Jim Tierney, the city official in charge of protecting the reservoirs and the region surrounding it, known as the watershed. "It makes protective efforts to keep pollutants out of the water all the more important."

With that in mind, in 1997, city, state and federal agencies and environmental groups reached an agreement designed to protect New York's watershed, which, though comprising just a fraction of the state's total land area, supplies water to half the state's population. "If there's anything you have to protect in New York," Tierney said, "it's this watershed."

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has waived the requirement that the city filter much of its water. But the city did not apply for a waiver for water coming from the Croton watershed and must now build a filtration plant. The city is currently reviewing three potential sites for the plant, one in Westchester and two in the Bronx. The plant must be operating by 2010 or 2011, depending on which site is chosen.

New York does treat its water though. Chlorine is added to kill organisms such as Giardia, which can cause diarrhea in humans. At each stage of the journey from here on, chlorine levels will be carefully calibrated and monitored, to make sure there is enough chlorine to kill bacteria and parasites -- but not so much that it makes the water disagreeable.

One part of fluoride per million parts of water goes in to help New Yorkers fight tooth cavities. The city adds orthophosphate to keep lead from leaching into the water, while some of the city’s water also gets a dose of sodium hydroxide to make it less corrosive.

Once water is treated, it enters City Tunnels No. 1 and 2, the main distribution tunnels. Pressure in the tunnels forces water up vertical shafts and into the city's water mains.

If there is a leak in either of these tunnels, there is little the city can do. Sandhogs are digging a 60-mile-long third water tunnel, but construction is not scheduled to be completed until 2020. Until then, engineers cannot shut down the city's two existing tunnels for repair.

"A disaster could happen at any moment, a disaster of epic proportions, or they will get the tunnel built in time. Nobody knows," said Jeff Jones of Environmental Advocates.

From the tunnels, the water branches out into the city’s water pipes. Some of these were first put into service in the 1800s, and as residents of Washington Heights discovered recently, they can burst, shooting geysers 20 feet into the air, turning streets into lakes, flooding basements and leaving hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage in their wake. New York City experiences 600 breaks per year on average, according to the Department of Environmental Protection. Even minor ones can sully the water supply and cause disruptions.

Before the water enters individual homes and buildings, it is tested again at one of the nearly 1,000 sampling stations throughout the city. Tony Speranza is one of 16 Department of Environmental Protection field collectors charged with monitoring water quality to ensure it meets federal and state guidelines. On a recent morning, Speranza's route took him to the corner of Maiden Lane and (aptly) Water Street. Inside an inconspicuous metal box resembling an oversized parking meter was a simple faucet and miniature basin.

First, Speranza disinfected and flushed the tap. Then, he pulled a milk crate filled with specimen containers -- each one labeled and bar-coded -- from the truck that doubles as his roving laboratory. As water gushed into the basin, Speranza checked for telltale signs of contamination.

According to Speranza, even small variances in temperature or conductivity (a measure of metals in the water) can indicate a problem in the system. And curbside sampling is especially important when it comes to monitoring chlorine.

From here, water is carried by service pipes to individual buildings -- and finally to residents' faucets. Officials will check some of this water as well, testing for lead levels. This final point marks the end of an extraordinary journey, one that is powered entirely by gravity.

If there are problems, as people like Speranza certainly know there are, still, as far as he is concerned, "New York City water is the best in the world."

Electricity

There are several ways to look at electricity. The most obvious is in our homes, the 100 to 220 volts that turn on the lights, run the computers and the television, cool us down in the summer and (in many homes) allow us to cook our food. The least obvious is at the level of the atom: An electric current is created when a magnetic field causes the outer electrons of an atom to escape.

Other articles in this series:

|

Another way is to look at the tall stacks of Keyspan's Ravenswood Power Station in Astoria sending out billowing plumes of steam and gas, a power plant that has been a major source of New York City's electricity since its construction in 1965. The plant can produce 2,200 megawatts, which is approximately up 25 percent of what the entire city needs on its most demanding day during the summer -- known as peak load.

But most New Yorkers looked at electricity with a new awe during one 24-hour period in August. You can make all the electricity you want, but transmission is key, as much of the Northeast, including New York City, learned when it suffered through one of the worst blackouts in history on August 14. Two weeks later, a blackout put the brakes on London during rush hour, and on September 28, a blackout darkened much of Rome.

The key to effective transmission and distribution is the grid, a somewhat ambiguous term that refers to the branching maze of cables and wires both overhead and underground through which electricity moves.

The production of electricity involves transforming energy from one form to another. Some kind of mechanical energy is needed to turn the rotating blades of the turbines that create the magnetic field. In New York State, thanks to Niagara Falls, that mechanical energy is hydropower some 16 percent of the time. Nuclear energy is the source about 20 percent of the time. Most of the rest is provided by fossil fuel.

Since New York City uses so much electricity, it is required to produce 80 percent of its peak load within city boundaries, from plants like Ravenswood. The first step in creating electricity at Ravenswood involves burning fuel to heat water.

The burning of fuel -- Ravenswood uses only natural gas and sometimes oil -- creates 1,000-degree steam in Ravenswood's 11-story-high boilers. (Ravenswood used to burn coal, which is far more polluting than the fuels it now uses.)

That steam then turns the rotating blades of the turbines. The turbines hold magnets that rotate 60 times per second. The magnets are each surrounded by a cylinder wrapped with copper wire. Every turn of the magnet creates an electric current in the copper wire.

Despite advances, this whole process of producing electricity is not very efficient. Only one third of the coal used in electricity generation, for example, is actually delivered to customers as electricity. The remainder is used up in the process or wasted.

After the energy is generated, it must reach the places that need it. High-voltage wires are fed to a handful of substations in the city through five major lines.

From these main substations, electricity goes out via other cables (know as feeders) to 45 area substations covering a smaller area. It then travels through the grid to still smaller areas and finally, to individual homes and businesses.

"The grid is where all the electricity flows. Companies generate power onto the grid and consumers get power from the grid," said Timothy Logan of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, a grassroots environmental network.

Each small area in the grid has its own circuit breaker, says Chris Olert of Con Edison. "The reason for this is reliability, to isolate a problem within a couple of blocks."

The local grid is 89,000 miles of underground cables and 33,000 miles of overhead wires that deliver electricity to 3.1 million locations in the five boroughs and Westchester County. The upkeep of this local grid is Con Ed's responsibility.

The transmission route from the plant to the consumer is a process of reducing voltages, otherwise known as "stepping down." This is done by transformers. When electricity is sent out from a plant, it is at a voltage high enough to fry or melt any device -- the lines outside Ravenswood carry up to 345,000 volts. At each branch along the grid, the electricity is stepped-down a little more until it reaches the 100 to 220-volt level for household usage.

And we use more of it all the time. Con Edison estimates that, every year, electricity use will be two percent to three percent higher than it was in the previous year. The top ten days of electricity consumption have all occurred in the last three years.

The New York Stock Exchange And Wall Street's Future

Outside the New York Stock Exchange Outside the New York Stock Exchange |

When the mayor and the governor held a press conference last week at the New York Stock Exchange, they promised a “bold vision” for a “new financial district.” At first glance, what they announced seemed neither bold nor even much of a vision. They presented plans to repave some streets outside the exchange, replace temporary concrete barricades with permanent fences and remove the parked pickup trucks that have been serving as makeshift safety barriers at several downtown intersections.

Even the timing of their press conference – the day before Thanksgiving – seemed to be saying: This is no big deal.

Modest as the plans seem, however, they were a welcome holiday gift to the business leaders and merchants of Lower Manhattan. Wall Street has been clamoring for officials to do something about the stifling security measures that have impeded traffic for more than two years; the complaints began while the twin towers were still burning.

If the streets outside the New York Stock Exchange are undergoing cosmetic changes, the changes happening inside the colonnaded marble building at Broad and Wall Streets are the most dramatic since the Great Depression.

After a series of scandals, the exchange in September named a new director, John S. Reed, who has set about trying to restore public confidence by completely restructuring the institution.

But even some of the exchange's biggest customers are questioning its very nature, suggesting that its time-honored trading floor, and the jobs it generates, be replaced with an electronic system similar to that used by fast-growing NASDAQ.

For New York City, the stakes are especially high. By thoroughly restructuring itself, the exchange is attempting to preserve jobs while retaining its primacy among stock markets and its position at the epicenter of the financial services industry. This industry is arguably the most important in New York, one that accounts for a third of the city's economy and a quarter of its tax revenues.

Even without the recent stock market scandals, New York's position as financial capital has been eroding. In the year 2000, the securities industry in New York City employed 189,000 people; a year later, thanks to the economic slowdown, the figure was down to 175,500. In 1991, the city had just over 30 percent of the nation's securities-related jobs. A decade later, thanks to the rise of electronic stock trading, the figure was below 24 percent. And this was before September 11th, 2001.

When the exchange threatened to leave town and move to New Jersey, city and state officials were quick to offer more than a billion dollars to keep it, promising new headquarters across the street from the current location.

The plans for the new exchange were scrapped after 9/11. Perhaps it is a sign of an era of lowered expectations that, instead of the Giuliani-era press conference announcing a billion-dollar subsidy, the one last week touted changes to the landscape that would cost a total of just some $10 million, paid for by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. In both cases, though, officials were communicating much the same message: Something must be done.

The New York Stock Exchange, says William Freund, its former chief economist, is facing not just temporary turmoil but a future of ever-greater competition. "I'm confident that it is going to prevail as an institution,” says Freund, now director of the Freund Center for the Study of Securities at Pace University. “But increasingly it will be a very tough fight."

CRISES

Departing New York Stock Exchange chief Dick Grasso, who leaves amid amid revelations of possible trading abuses and conflicts of interest. Departing New York Stock Exchange chief Dick Grasso, who leaves amid amid revelations of possible trading abuses and conflicts of interest. |

The New York Stock Exchange has weathered many crises since 1792, when a group of traders met beneath a buttonwood tree on Wall Street and formed a loose association that grew into the world's most powerful financial market.

Recent times, however, have been especially difficult. The dotcom bust, revelations that star analysts touted questionable stocks to boost their firms' investment banking businesses and the collapse of such high-flyers as Enron, Worldcom and Tyco shook investor confidence and tainted the investment industry.

This summer, scandal hit the exchange itself after revelations that New York Stock Exchange chairman Richard Grasso was awarded a $187.5 million pay package by a board of directors that he essentially controlled. One particularly irksome item was the $5 million bonus Grasso received for getting the exchange up and running after September 11, 2001. Thousands of others on Wall Street worked tirelessly at the time without any extra compensation.

Though Grasso is widely credited with preserving the New York exchange's share of the market for stocks, during his tenure the exchange developed a reputation for being a vast insiders' playground. His departure unleashed revelations of possible trading abuses and conflicts of interest at the exchange and elsewhere in the financial industry, including a series of investigations by New York State Attorney General Elliot Spitzer that further tarnished Wall Street's image.

UNLIKELY RADICAL

To replace Grasso the exchange tapped as interim chairman the 64-year-old Reed, a former Citicorp chairman known for his fascination with organization charts and information systems.

Coming back from the island off the coast of France where he had comfortably retired, Reed got right to work and declared that he would take a hands-on approach. He set about completely revamping the exchange, making its operations more transparent to both investors and regulators.

"I am a revolutionary," Reed told London's Financial Times in a November 13 interview, his first after taking over.

Reed proposed sweeping changes in the way the exchange is governed. In place of its 27-member board, he called for creating two panels. An eight-member board intended to be independent of the exchanges' management would be responsible for governance and regulation. A second "board of executives," with 20 members drawn from Wall Street firms, specialists and others in the securities industry, would oversee day-to-day operations.

"I am a revolutionary," John Reed told London's Financial Times. "I am a revolutionary," John Reed told London's Financial Times. |

Reed's plan was approved by the exchange in mid-November, but the Securities and Exchange Commission still has to give its approval. So far, reaction is lukewarm.

The commission's new head, William Donaldson, favors replacing the exchange's self-regulatory apparatus with a totally separate, independent system. New York State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, who controls pension funds and is involved in a nationwide coalition aimed at reforming corporate governance, said he too was "disappointed"with the exchange's plan.

Still, the efforts are radical for an institution that has been resistant to change. "If the New York Stock Exchange gets reformed, which I think is a pretty good bet right now, this is on a par with the reforms of 1933 and 1934," Charles R. Geisst, a Wall Street historian and professor at Manhattan College in the Bronx, told The Washington Post recently.

And however the governance issue plays out, an even more sweeping change may soon alter the open auction system that has been central to the New York Stock Exchange's trading system for decades.

Like many self-styled reformers, Reed may find that his revolution overtakes him and acquires a life of its own. With the iron-willed Grasso gone, old discontents are bubbling to the surface, threatening to touch off a new battle over the structure of the exchange and the very shape of U.S. financial markets.

Lately, some of the exchange's biggest customers, among them giant mutual funds and government pension funds, are saying out loud what had only been whispered in the past: that it's time to dump the NYSE's "open outcry" trading system, which relies on middlemen called specialists, and move to an electronic system that would mean lower costs for investors and would offer fewer opportunities for corruption.

This would mean the end of the exchange's famous trading floor, with its frenzied auctions and piles of discarded order slips.

AN ENTERTAINING ANACHRONISM

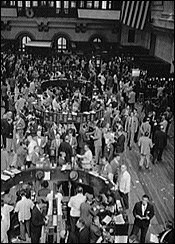

In an age of microchips, the New York Stock Exchange trading floor is an entertaining anachronism.

At the exchange, when an order comes in, either by phone or electronically, it is sent to one of some 430 specialists, who handles all of the trading for that stock and several others. These specialists are the people in the colored jackets who can be seen striding around or waving bits of paper in TV news shots of the trading floor.

The trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, 1955. The trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, 1955. |

Each specialist, who is stationed at a booth on the floor of the exchange, essentially conducts an auction of his stocks, matching buyers and sellers or dipping into his own company's holdings to make sure there are enough shares available.

Once buyers and sellers are matched, the specialist reports the results of the transaction and the information is sent out to quote systems so that others know the stock's most recent trading price.

On electronic exchanges like Nasdaq, computers scan all the orders and match up buyers and sellers at the best available price.

The New York Stock Exchange's human-based trading system is, of course, supported by a vast network of electronics. Thanks to computers and productivity gains, it now trades an average of 1.5 billion shares a day; just a couple of decades ago it handled a couple of hundred million.

Critics say that computers are more efficient and far less likely to bend the rules for their own gain.

Because the New York Stock Exchange's specialists, unlike all other traders, have knowledge of all the bids and asking prices on a stock, they can gauge the direction of share prices before anybody else. Stock market officials say this allows them to maintain a fair and orderly market by stepping in and bringing sellers and buyers closer together. But critics charge that the specialists are perfectly positioned to fleece other traders.

"In the biggest, deepest market on the planet, I don't understand why there has to be someone who has advantage over everyone else" Scott DeSano, head of global equity trading at Fidelity, told USA Today. "All we're trying to promote are free, competitive markets."

Others point out that some of the large mutual funds that are criticizing the specialist system own stakes in fledgling electronic stock trading outfits that would like to siphon business away from the New York Stock Exchange.

The New York Stock Exchange is determined to defend its long-established ways.

"The specialist system works and it works very well," NYSE spokesman Rich Adamonis said.

WILL 'WALL STREET' STAY ON WALL STREET?

Amid all the uncertainty surrounding the stock exchange, one thing is clear:the New York Stock Exchange will stay in its columned 1901 edifice -- at least, for the moment.

A couple of years ago, it seemed virtually certain that the exchange would move to a new building across the street. In the biggest of all the Giuliani-era business retention deals, the city and the state agreed to shell out as much as $1.1 billion over a number of years to keep the New York Stock Exchange from carrying out its threat to leave for New Jersey. As part of the package, the city agreed to buy land for the exchange's new trading floor. A residential building on Wall Street was even emptied in anticipation of the project.

But the deal was put on hold after the September 11 attacks, and eventually the exchange, after rethinking the wisdom of building a conspicuous new headquarters, pulled out entirely. The city had already spent some $80 million.

So will Wall Street stay forever on Wall Street? The exchange now has an auxiliary facility in Brooklyn, at the Metrotech Center, in case of further disaster in Lower Manhattan, and another such facility at undisclosed location in the city. It is considering other sites in the suburbs.

A New Future For The Great Port

Few holiday shoppers along Fordham Road in the Bronx or Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn or Roosevelt Avenue in Queens probably take the time to contemplate the waterfront, much less imagine how connected they are to the ship captains, truck drivers, warehouse managers, and stock boys who make their living from the port of New York and New Jersey. But the bargains New Yorkers seek on the shopping streets of the city began fantastic voyages in factories far away.

Far from being the mere backdrop to nostalgic old movies, the port is not only alive, it recently crossed a number of new milestones.

In the summer, another 1,000 longshoreman were hired, the first time in more than three decades that the on-dock labor force grew. This is not for lack of work, given that globalization has been fueling tremendous growth in international trade for the last half-century. Instead, advances in technology such as the shift from break-bulk to containerization have made port commerce much less labor intensive: A handful of workers, one in a crane and a few working on-dock vehicles can do the work that hundreds did back in the 1950s. The port now employs more than 228,000 people region-wide, making it a close competitor to education and health care as a major employer in New York City.

This fall, the port announced a 14.3 percent increase in container volumes, those modular steel boxes that sit on a truck trailer and arrive stacked in piles of thousands aboard oceangoing cargo ships. While the increase in imports was more than 16 percent for the first half of the year, the increase in exports through the port nearly topped 10 percent. The value of goods moved through the port in the period was also impressive: at more than 42 billion dollars for six months, this amount surpasses the value of the tourism industry in New York City over an entire year. The port isn't resting on these laurels either. They are fast-tracking a number of dredging projects to ease the approach to the container terminals along the Kill Van Kull and Newark Bay.

Undoubtedly the greatest sea-change of 2003 was seen in the Port Authority's recent support of the cross-harbor freight tunnel. As reported in Crain's New York Business, Port Authority Executive Director Joe Seymour has decided that building the tunnel is critical to regional and national security. To a region that has added millions in population yet not created a new cross-harbor linkage in 40 years, it is increasingly obvious that more linkages across our region are critical if we are to continue to add to the competitive advantage in transportation that makes New York a great place to live, work, and yes, consume. The benefits of the tunnel would be many.

Ironically, there is no press release on the Port Authority Web site announcing this new willingness to embrace a massive public works project that they have staved off for more than 70 years. The agency's acceptance of the cross harbor freight tunnel, however mild, is in no small part due to the diligence and dedication of a small group within the city's Economic Development Corporation, who for years now have shepherded a cross-harbor freight study through the exploration of more than three dozen options to link New York and New Jersey across the water, including the tunnel. The draft environmental impact statement is expected in a matter of months.

Looking ahead, the city will need more than massive regional projects such as the freight tunnel; we need local infrastructure too. Another milestone passed quietly in November, when the Manhattan and Bronx Surface Operating Transit Authority cleared out all the buses from Pier 57 in Hudson River Park. With a "request for expressions of interest" now out on the streets, it is looking more and more like another waterfront transportation facility may be hacked up by golf clubs and squash rackets. With a big-box store headed for Erie Basin, the largest protected inlet within New York City, it looks more and more as if the city is turning a blind eye to freight movement just as New York State and the Port Authority are starting to catch on.

Carter Craft, an urban planner, is program director of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.

Advocates For The Ill

When illness strikes, middle-class patients and their families can quickly slip into poverty. As they struggle with the impacts of sickness, such as pain, changing family roles and changing work situations, they may not know that they are eligible for support that could prevent further financial decline.

Patients already poor could become even worse off.

This is why a shadow industry has emerged to let ill people know what public benefits they are entitled to, to help them fill out applications, even to communicate with government caseworkers when things go wrong.

Finding a trained advocate is often the only thing that keeps a family together in their own home. However, many agencies serve only a slice of the population with specific characteristics, so another large part of what they do is “information and referral,” often between one another.

• Housing Works is one of dozens of agencies serving the HIV+ population. Its case managers, among their other duties, struggle to get the city’s HIV/AIDS Service Agency to fulfill its mandate to coordinate services for their clients.

• People with other specific diseases or conditions may turn to specialty organizations, such as Cancer Care, Inc., which employs 50 social workers trained to help cancer patients deal with the emotional, financial, and medical effects of their illness.

• Independent living centers help low-income people with disabilities to apply for social security benefits and similar income supports, and navigate agencies and courts concerned with such major life issues as child welfare and housing.

• Immigrants, descendants of different ethnic groups, and subgroups of these populations have their own social service agencies. For example, Blue Card was founded by Jewish refugees in 1939, and is still helping low-income Jewish Holocaust survivors to cover the gap between inadequate incomes and the rising cost of living.

• Supportive housing providers not only house residents with mental illness or substance abuse histories. They also provide rehabilitative treatment and coordinate residents’ public benefits and other social services.

• Many senior centers have social workers on staff to help members get the benefits they are entitled to. They sometimes report having a hard time convincing impoverished elderly people to apply for food stamps, due to the stigma attached to “welfare”.

Every hospital employs “discharge planners,” usually social workers, whose role includes making sure that after a hospital stay, patients have a place to go home to, and someone to help them with everyday tasks, if necessary. Single parents who can manage their own daily lives may need a homemaker for their children. Poor people may need help applying for Medicaid so that they can afford follow-up health care.

However, once the patient is back home, the hospital discharge planner is rarely involved in making sure that services work as planned, or that they change to meet changing needs.

When a government agency denies an application for benefits or services, or reduces or ends existing services, legal help can be needed to reverse the decision. Each government agency has an appeals process that, in theory, does not require a lawyer’s assistance. However, layers of inadequately trained personnel separate clients and their advocates from the officials who judge their appeals. It can be equally difficult to learn the process of appealing a decision that denies services, to gather documents and successfully present a client’s case, and to compel an agency to comply with a hearing officer’s decision in the client’s favor.

The New York Legal Assistance Group launched the LegalHealth project in September 2001 as a response to the complex needs of people with serious and chronic illnesses, and low-income patients needing medical care. Since then, they have directly helped more than 600 patients, and trained over 1,000 medical professionals and social workers how to identify and deal with the legal problems of low-income, chronically ill patients.

A typical LegalHealth client is a cancer survivor who missed a Medicaid appointment while she was in the hospital for treatment. The missed appointment triggered a halt to her welfare benefits, which could have prevented her from paying rent and resulted in her family becoming homeless, not for the first time. She also was required to go to Family Court to be a witness in a child support hearing, despite her severe illness.

The New York Legal Assistance Group successfully appealed the cutoff of her welfare checks, accompanied her to Family Court to ensure that proceedings went as quickly as possible, helped her draw up a will providing for legal guardianship of her young son, and assisted her with income tax problems.

Linda Ostreicher, a former budget analyst for the New York City Council, is a freelance writer and consultant to nonprofits.

Stopping The Truckers From Idling At Hunts Point

A half-dozen trucks are lined up on Halleck Street outside the Hunts Point Produce Market. The seats are empty, but the engines are running as drivers squirrel up in the back of their cabs and while away the hours with the help of a little satellite television. They are.waiting for an open bay inside the market.

It's an unusual sight in this neighborhood only when you consider that it comes less a week after the market's promised November 1st crackdown on excessive idling. The product of an agreement with the state attorney general's office, the crackdown is supposed to send a message to out-of-state truckers: In a state that forbids non- operational idling past five minutes and a city that forbids it past three minutes, the city has zero tolerance for egregious offenders.

For Majora Carter, executive director of Sustainable South Bronx, a local non-profit dedicated to the environmental remediation of this blue collar neighborhoods, it's a frustrating reminder that some messages take a while to get through.

"We thought the agreement was great," says Carter. "The problem now is enforcement. There's still an atmosphere that says you can do whatever you want."

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S "CARROT"

Clearing up that atmosphere, not to mention the real atmosphere of Hunts Point, is no easy task. Idling is a problem citywide, as recent attempts to clean up the city's school bus fleet has dramatized.

Here in Hunts Point, however, the issue is a little more pressing. Site of the two largest wholesale markets in the city -- the produce market and the nearby Hunts Point Cooperative, a wholesale meat market -- Hunts Point is a magnet for big rigs and the sooty exhaust they bring. Little wonder the neighborhood scores among the highest in the city when it comes to childhood asthma rates -- 10 per thousand vs. 6.06 per thousand citywide and 3.36 nationwide according to a 2000 New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene study.

Lem Srolovic of the Attorney General's environmental protection bureau, the organization that forged a June, 2003 deal with the Hunts Point Produce Market to launch the self-policing program, says his office is weighing other ways to reduce emissions in the neighborhood. Still, with only four lawyers covering a region that stretches from Poughkeepsie to Montauk, Srolovic admits to being selective in both methods and targets.

"We've decided that with out tools and our resources, we could be most effective at the fleet or market level," Srolovic says.

In the case of the Hunts Point Produce Market, a regional wholesale supplier to local green grocers, that meant applying a strategy perfected over the last three years against large scale operators such as Frito-Lay, Inc. and Greyhound Lines, Inc. First, Srolovic and his staff documented the high number of residential complaints over truck exhaust and truck noise, building a quality-of-life component into the state's case. Second, they gathered together a paper trail of police and traffic citations, framing the market as a nuisance. Finally, they offered market operators a carrot-or-stick proposition: Fix the problem yourself or have the state fix it at the market's expense.

"The state idling law specifically puts an obligation on the owner or operator of real estate that exercises control over vehicles operating within that real estate," says Srolovic. "So there is a direct legal obligation on the market's part to effectively control idling."

To their credit, market operators chose the carrot. The market has hired four enforcement officers who, since the beginning of the month, have been issuing citations to trucks ignoring the local anti-idling statutes. Citations run from $250 to $875 depending on the nature of the offense.

SHIFTING THE EXHAUST

In stepping up enforcement within its own gates, however, the Hunts Point Produce Market has achieved the unfortunate short term result of pushing more scofflaws --and more exhaust -- out into unpoliced neighborhood streets.

Eager to correct this problem, politicians, neighborhood groups, and even the market itself are now searching for fresh carrots and scarier sticks.

On the carrot side, Carter and her colleagues point to the nearby Hunts Point Cooperative Market, and its 28 ."ATE" bays - ATE standing for Advanced Truck Electrification. They were created with funds from a combination of government and non-profit agencies.

Outfitted with air conditioners and heating units, these towers pipe in basic amenities that allow truckers to live and sleep in their rigs while waiting for an open slot in one of the terminal bays.

"They've got everything: Internet, cable TV, 125 channels," notes Ernie Digenstein, a trucker dropping off a load of frozen turkeys at the meat market.

Based out of Watertown, South Dakota, Digenstein says the towers are fairly standard at truck stops across the country and provide a welcome alternative to the engine wear and fuel consumption that comes with operating a truck engine in idle mode as a way to generate heat and power.

Still, old habits die hard. So do old attitudes. New York's reputation as one of the costliest destinations in the country creates a situation where many drivers don't feel an obligation to do the city, or its residents, any favors.

"If it's below zero, and the towers are full, I don't care how many tickets I'm gonna get," says Digenstein. "I need heat."

THE NEXT STEP?

Such attitudes will take a while to overcome. Hunts Point Produce Market managers are already talking with companies about installing similar units. In the meantime, local politicians are working on the stick-side of the equation. The New York City Council is currently weighing a bill, Bill No. 366, to increase the number of traffic officers authorized to issue citations for off-route driving and excessive idling.

Srolovic of the Attorney General's Office sees the June agreement as a "first step" and acknowledges that more steps will need to be taken in order to diminish the problem in a way that will satisfy Carter and other local residents. At the same time, however, he says his office is already looking toward the next major step in the hope that truck and bus companies, at least at the management level, don't take the current enforcement gap as a signal to relax.

"This is not the end of the idling enforcement story," Srolovic says."We do have other investigations underway."

Siting The Power Plant at Newtown Creek

Krysia Holowacz knows dirty. A former resident of Eastern Europe who emigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s, she's seen what industrial pollution can do to a once pristine landscape.

So when she drives her car down a semi-paved street that dead-ends 12 feet above the blackened waters of Newtown Creek, the waterway that separates Greenpoint from Long Island City, it's hard not to notice the awe.

"Can you believe this?" asks Holwacz, rising out of the car, holding her arms wide, and struggling to be heard over a pair of cranes lifting demolished cars off a nearby scrap metal barge.

The view is, indeed, awe-inspiring. Picture the Thames River at its Dickensian worst, only replace the tanneries and rendering plants with asphalt recovery and waste transfer stations, and you'll get a pretty good idea. Fortunately, it's a view few New Yorkers ever experience. Nearly two centuries of continuous industrial development and the quirky street patterns of the Brooklyn-Queens border combine to make this one of the least-accessible portions of the city.

That's one reason Mayor Michael Bloomberg, in a radio address earlier this month, offered Newtown Creek as a compromise site for a new 1,100 megawatt TransGas Energy power plant. Originally slated for the East River side of the neighborhood, the plant has drawn stiff opposition from local groups and environmental advocates who would like to see the East River waterfront cleaned up.

SAVVY COMPROMISE, OR DEVIL'S BARGAIN

Politically speaking, the mayor's compromise is a savvy move. Exchanging one site for another opens up the two mile Williamsburg-Greenpoint waterfront to residential redevelopment -- a move the mayor thinks will lure billions of dollars into the local economy. At the same time, it offers an easy solution to the city's pressing energy needs.

But for local activists like Holawacz, who lives in Greenpoint, the compromise is an environmental equivalent of the devil's bargain: As much as she wants a clean riverfront with more open space for parks, Holowacz, a community liaison for the Newtown Creek Water Pollution Control Plant who already fields plenty of complaints over that plant's ongoing expansion, recoils at the thought of adding yet another source of toxic emissions to this already-beleaguered corner of Greenpoint.

"This community is inundated," says Holowacz. "We get all the smell and all the paper and all the scrap metal. You can't put everything the city needs into one corner."

Officially, the decision on where to put the TransGas plant isn't the mayor's to make. That power resides at the state level, where Governor George Pataki has expressed support for new power plants as a way to meet the city's surging energy demand and decrease dependence on the regional grid. In May, the mayor's office threw its weight behind the neighborhood groups and developers who have opposed the siting of a power plant near Bushwick Inlet on the grounds that it would foil ongoing efforts to redevelop the Greenpoint-Williamsburg riverfront from industrial to residential use.

"This administration recognizes the need for new power plants and transmission lines," noted Daniel Doctoroff, deputy mayor for economic development and rebuilding, in a July 15 editorial for the Daily News." [But] when a power plant comes into conflict with a historic chance to rezone the waterfront to develop a 2-mile waterside walkway and create much-needed housing (both affordable and market-rate), it is in the city's best interest to find a more suitable location to benefit all parties."

In the final week of September, the mayor's office thought it had just that when it talked ExxonMobil, current owner of a derelict storage facility located on Kingsland Ave. a half mile downstream from the Kosciusko Bridge, into possibly selling the lot to TransGas as an alternate site.

SITE OF LARGE OIL SPILL

The deal is a tenuous one. The new site carries heavy legal baggage. In the 1950s and 1960s it was the site of the nation's largest underground oil spill; more than 17 million gallons seeped out of tanks and pipes and into an underground aquifer, a multi-year discharge that wasn't detected until the Coast Guard noticed a major oil plume in the creek in the late 1970s. In 1989 Mobil (now ExxonMobil) assumed cleanup responsibilities but according to an August report in the Polish Daily News has removed only about two million gallons to date. At that rate, the site will be fully remediated by 2030.

"You're talking about a discharge larger than the Exxon Valdez," says Riverkeeper legal investigator Basil Seggos, likening the 52 acre site to the famous 11 million gallon oil spill in Alaska in 1991. "You're not just talking about water pollution. You're talking about hydrostatic pressure of a new plant and trucks possibly extending the plume.

Neighborhood activists have concerns beyond underground oil. For the last 15 years, Greenpoint and Williamsburg residents have been united in their effort to rezone and redevelop the two mile East River waterfront. To accommodate this rezoning, they've agreed to leave new industrial development along Newtown Creek.

"Every city has an industrial area, and we decided that is our industrial area," says Joe Vance, co- chair of the Greenpoint Waterfront Association for Parks and Planning. "We'd certainly like to see the pollution cleaned up, but we'd like to keep that area industrial. The city needs the jobs. There's lots of really good companies, there. We don't want to see them go."

DIVIDING THE COMMUNITY

At the same time, Vance and other rezoning advocates fear the psychological impact of adding a power plant to a neighborhood that is already dealing with the expansion of the Newtown Creek sewage treatment facility. Soon to be the city's largest, the plant and its many odors have already prompted grumbles over residents on one side of the neighborhood selling out their poorer neighbors on the other.

"What you're doing is dividing the community along McGuiness Avenue," says Community Board 1 rezoning task force chairman Christopher Olechowski. "If [the mayor's plan] goes forward, it sets up kind of an imbalance in the community. It favors a waterfront rezone for market rate development but leaves the other side of the community as sort of a second tier segment."

For this reason, community activists and their environmental allies around the city have been hesitant to endorse the mayor's compromise. Still, Olechowski says even silence can come across as a tacit endorsement compared to the relative outcry over the East River site.

"I haven't heard any strong voices from any of the elected officials saying, 'We won't tolerate this,'" Olechowski says. "Maybe it's something I've missed, but I haven't seen it, yet."

David Yassky, the councilmember whose district includes Greenpoint, opposes the original siting plan but has yet to give the mayor's compromise proposal much thought.

"If somebody wants to put a power plant on the Exxon Mobil site they're going to have to file hundreds of pages of documents on what the environmental impact's going to be," Yassky says. "At this point, it really isn't far enough along for me to be able to comment."

Neighborhood activists and environmental groups, meanwhile, are trying to make sure the issue doesn't get to that point. Riverkeeper is set to announce a fresh series of lawsuits aimed at companies it says are currently the leading polluters along Newtown Creek. Neighborhood activists, meanwhile, are recycling the same arguments used against the original plant site.

"Why not upgrade existing power plants just like they're upgrading the sewer plant?" says Holowacz, noting that a number of local, oil-burning plants could gain increased efficiency while reducing toxic emissions if they switched to natural gas as a fuel source. "It's basically the same law, and yet they're not doing it."

With the recent blackout, however, energy companies like TransGas hold a momentary edge. The city's demand for power is growing, and August's power outage will still be fresh in minds of voters going to the polls next November. Even though the outage was the result of supply problems outside the city, the time has never been better, politically at least, to push for local plants.

Vance says the neighborhood still has the strength to hold its ground even without the real estate developers that helped foil the East River site.

"Greenpoint used to be the weakest link," he says. "Politicians looking at a map wondering where they could put something and get the least fallout always pointed here. That began to change in 2000 with the ConEd/Keyspan plant vote."

At the same time, Vance says, it will take a concerted effort to make sure that neighbors who see riverfront redevelopment as a community-wide issue also see Newtown Creek's overloaded banks in a similar light.

"People throw around the term 'Not In My Backyard'," Vance says. "But the East River was our front yard, and we can't put anything more in the backyard, because it's full. I challenge anybody to find any community in the city that has more citywide projects like this."

The Sewer System

Sewage was probably the last thing on the minds of most New Yorkers during the August 14 blackout. But while millions of people struggled to get home or contact loved ones, city workers watched helplessly as untreated waste poured into the East River from a pumping station at Avenue D and East 13th Street. With no electricity, nothing could prevent the pressure of the water from pushing open the gates that control the discharge of untreated sewage and so it simply blasted out.

Other articles in this series:

|

By the time the power came back, 145 million gallons of raw sewage - water from toilets and sinks as well as storm runoff -- had flowed into the East River from 13th Street and another 345 million gallons had spilled from treatment plants along the Hudson River in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Sewage accidents caused by blackouts are rare, of course. What most people do not realize, however, is that spills are quite common. Even after decades of expensive upgrades designed to curb pollution, raw sewage regularly pours into the waterways around New York City because the sewer system uses outdated technology.

Failing sewers are not a problem limited to New York City. On November 4, all voters in the state, including those in New York City, will be asked to approve a constitutional amendment (in pdf format). that would help some smaller upstate communities upgrade their wastewater facilities.

Construction of a Tunnel Sewer under 10th Avenue, 1938.

The measure will not help New York City control sewage spills or deal with the other problems of its massive sewer system. The city will be on its own when it comes to maintaining aged pipes, getting rid of environmentally harmful nitrogen, and dispelling the persistent belief that alligators live in its sewers.

FROM DITCHES TO DUMPING TO DECAY

New York City's sewer system, an engineering marvel and a murky source of urban legend, contains 6,600 miles of mains and pipes. Placed end to end, the city's sewers would stretch from Times Square to Fairbanks, Alaska and back. About 70 percent of that vast sewer system consists of combined sewers, which carry runoff from storms as well as waste from sinks, tubs and toilets. Some of the pipes still in use were laid 150 years ago when the modern sewer system began.

The city's first underground sewer of any kind goes back even further, to Dutch Colonial times, when a channel was dug down the middle of Broad Street and decked over. But well into the 19th century, most waste was typically disposed of in backyard outhouses, dumped into the gutter or poured into the ponds and streams that still existed in many parts of Manhattan.

Explosive growth in the early 1800s forced New York to finally confront its sanitation problems. In 1849, after years of haphazard planning and a series of deadly cholera outbreaks, the city started systematically building sewers. Between 1850 and 1855, New York laid 70 miles of sewers. In the second half of the 19th century, it expanded the network throughout the metropolis. By 1902, sewers served virtually all the developed sections of the city, and even tenement houses began offering private flush toilets. Today, sanitary sewers snake their way beneath all but a handful of outlying streets, and storm sewers crisscross just about every neighborhood.

THE JOURNEY

Each day, the city's 14 sewage treatment plants handle 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater, roughly 162 gallons for every man, woman and child who lives in the city.

Whenever you flush or turn on a faucet, the wastewater flows through pipes that lead to sewer pipes, called mains, in the street. Sewer mains are typically three to five feet in diameter. Runoff from rainstorms (and all the stuff that collects in the gutter) joins it in combined mains.

Building a Trunk Sewer in Queens, 1938

|

The sewage and runoff flow into a series of progressively larger pipes until they reach the wastewater treatment plant. The system relies almost entirely on gravity to keep the waste moving, although pumps help where the topography is difficult.

For decades, the waste simply went from the pipes out into the waterways surrounding the city. Most treatment plants in the city were not built until after World War II, and the last of these, the North River plant in West Harlem and the Red Hook plant in Brooklyn, were not completed until the late 1980s. As recently as 1986, all the sewage from the Upper West Side of Manhattan flowed untreated into the Hudson River. Ending that sewage flow played a big role in the river's rebirth.

Now the sewage goes to a plant for several stages of treatment. In the first stage, known as primary treatment, the water flows through filters and then collects in pools, where solids settle to the bottom so they can be removed. Until 1992, the city dumped about five million tons a year of these solids, known as sludge, in the ocean. It now dehydrates the sludge at special de-watering facilities that reduce its volume dramatically. The sludge is then either carted to dumps out of state or processed into materials that can be used for landfill cover.

In the secondary treatment stage, the wastewater is sent to large tanks where bacteria consume nutrients and organic materials. After the bacteria do their job and die a natural death, they are allowed to settle out of the water in tanks and then the cleaned water is released. One of the byproducts of the bacteria processing the waste is nitrogen, which mostly comes from the breakdown of ammonia in the sewage.

OVERFLOWING PROBLEMS

That is what happens when the system operates properly, but all too often it does not. Whenever there is a significant rainfall, sewer pipes overflow, and trash and chemicals pour directly into rivers and bays. Normally, all the waste in a combined system - toilets, sinks and runoff -- flows into sewage treatment plants. But when it rains heavily, all the the pipes tend to become overwhelmed and spill their contents. Each year, about 40 billion gallons of wastewater pours out of the combined system " a seemingly large amount but far less than in the past," city officials say

"Any time you get over a tenth of an inch of rain per hour, there are overflows," says Terry Backer of Connecticut-based Long Island Soundkeeper, an environmental group. "Oil, garbage, ethylene glycol [antifreeze], dog poop and everything in the gutters comes blasting out of the system, and then we tell our kids to go swimming in it."

Now that the city has upgraded its sewage treatment plants to comply with the federal Clean Water Act, it will focus on stanching such overflows and limiting the amount of nitrogen discharged from the sewer system into waters feeding Long Island Sound. "The key sewer-related issue right now for us is definitely the decrease of overflows," says Ian Michael, press secretary of the Department of Environmental Protection. The city has embarked on a 10-year overflow reduction program that will cost $2 billion, he says.

Environmentalists have been pressing the city about this. The current situation is "outrageous," Sarah J. Meyland, executive director of Citizens Campaign for the Environment, told The New York Times recently. "Across the board there often is a very casual feeling about allowing raw sewage back into the environment under sporadic circumstances, as if sewage is really not that bad."

Construction Crew at a Storm Sewer in Queens, 1938

|

Many see the combined sewers as the culprit. Only about 800 U.S. cities still rely on combined systems. The rest, some 20,000 municipalities, carry wastewater and storm runoff in separate pipes. The separate sewer systems prevent overflows and are more efficient because treatment plants do not have to accommodate storm runoff along with wastewater.

But building separate sewers in New York would be prohibitively expensive. Instead the city is constructing huge underground reservoirs where the overflow can be held until water levels subside and the waste can be safely pumped into the treatment plants without spilling.

Poor equipment poses another problem. The 13th Street plant had emergency generators to prevent spills but they failed during the blackout. Some in the community have opposed the generators because the neighborhood already has a Con Edison plant in addition to the pump station. But the city is ready to install new backup power systems.

THE NITROGEN PROBLEM

The city is also under pressure to reduce the amount of nitrogen it discharges along with treated sewage water. Nitrogen feeds huge growths of algae, which deplete the supply of oxygen in the water as they die and decompose, choking fish and other marine life. Environmental groups say that excessive nitrogen levels in New York City's wastewater have undermined efforts by other Long Island Sound communities that have spent hundreds of millions of dollars to clean up discharges and restore the marine ecosystem.

One such group, Soundkeeper, filed suit in federal court in 1998 accusing the city of failing to comply with nitrogen regulations and trying to delay a clean up. After the states of New York and Connecticut joined the environmentalists' action, the city in late 2001 agreed to begin nitrogen reduction, using natural chemical reactions.

But some environmentalists think this is not enough. At a hearing before an administrative law judge in Nassau County on October 2, Soundkeeper argued that the city should be held to stricter standards under its permit to discharge wastewater. The city, which has invested heavily in nitrogen removal in recent years, says it is doing plenty and should be able to seek the most cost-effective solutions. The hearing process could take four to six months.

AGING EQUIPMENT

In the sewer pipes, age is a continual and critical issue. The heavily used system still includes 1850s-vintage pipes below parts of Lower Manhattan. Sewer workers regularly send remote-controlled video cameras through the pipes to try to spot leaks and cracks and patch or replace damaged pipes before they break. But replacing whole stretches of old pipes is not an option, because officials believe that even a major water or sewer main break is less disruptive than ripping up miles of streets to lay new pipes. "We know for a fact that they'll continue to last," Michaels says. "It is not just a matter of crossing your fingers and hoping they keep working."

The city is also repairing one of its oldest treatment plants, Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, where a fire in August damaged the odor-control system and sent foul-smelling gases wafting over the surrounding residential neighborhood.

The measure on the ballot this fall is designed to help smaller communities fund some of the projects New York City has already undertaken. If passed, it would allow counties and municipalities to exclude the cost of building or refurbishing sewers from municipal debt limits until 2014. Assemblymember Robert K. Sweeney of Suffolk County, who sponsored the measure in the Assembly, says it will help communities that have small tax bases by allowing them to borrow for sewer projects without having to postpone building roads and schools. The debt limit is pegged to the size of the tax base,

"In the past 10 years there have been less than two dozen communities statewide, most of them upstate, that have been covered by this," says Sweeney. The measure, which sailed through the state legislature earlier this year, renews a provision first enacted in 1963.

LATER, ALLIGATOR

Whatever the problems facing New York's sewer system, video inspections of the sewers do not turn up colonies of alligators.

Contrary to popular mythology, there are more alligators living in Manhattan apartments than underneath the city.

The alligator story is an old one, but it got a big boost in 1959, with the publication of Robert Daly's otherwise credible book, The World Beneath the City. Daly relied a bit too heavily on an imaginative former sewer inspector named Thomas May who said that, as he went on his rounds, he encountered reptiles of "alarming sizes."

A new sewer-related urban legend has been born in recent years. The story goes that marijuana, hurriedly flushed down toilets to keep it from police and prying parents, has taken root in the sewers. Fed by nutrient-rich sewage but deprived of sunlight, it mutated into an extremely potent albino form. Known as New York White, this pot is said to be incredibly expensive. That's because to harvest it, you have to get past, yup, alligators.

Natural Gas

The natural gas that boiled the water for a cup of tea on a stove in Queens Village last night began its journey near Nova Scotia some 140 million years ago. The muddy bottom of a lush swamp turned into something harder and began buckling. Plant and animal matter that had decayed and turned into methane and propane filled the gap underneath the buckled surface and remained there for eons.

Other articles in this series:

|

Not long ago, a drill bit finally hit the pocket to extract these ancient gases and pipelines brought them the thousand miles to the grills and stoves, as well as the furnaces, clothing dryers and power plants, of New York City.

The odyssey of natural gas is impressive. Only decades ago, the fuel was viewed as nothing more than a pesky byproduct of petroleum, a nuisance that made it more difficult to extract the "black gold" underneath.

Now natural gas itself has become a kind of gold. It's not just for breakfast anymore: Many city homeowners made the switch from oil to gas heat for their furnaces in the mid-1990s, and federal clean-air legislation pushed local power plants to do the same, with some wonderful results: cleaner facilities, better fuel efficiency, and less dependence on a worldwide marketplace dominated by OPEC oil ministers.

But as demand has risen, so too has cost. The federal Energy Information Administration predicted earlier this month that the average American family will pay nine percent more for natural gas heat this winter than last.

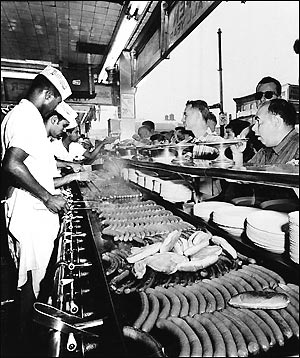

Cooking with natural gas at Coney Island, 1958.

This will still be less than for oil -- an estimated average of $841 compared to $927 -- but it is not likely to stay that way, according to New York State Assemblyman Paul Tonko, chairman of the Assembly Energy Committee. And there is a danger, Tonko says, in relying more and more on this one fuel source: "As natural gas becomes in larger measure the fuel of choice for both heating and electricity generation, we're creating a very risky situation for consumers."

THE JOURNEY

The term "natural gas" often leads to confusion. Some confuse it with the gasoline used in cars. But at room temperature, natural gas is just that, a gas, while gasoline is a liquid. Natural gas, says Ed Yutkowitz, a spokesman for Keyspan, can also be confused with the gas that lit New York's streets and fueled its stoves until the 1950s. That gas, which was highly toxic, came from superheating coal. But, beginning in the middle of the 20th century, companies began building pipelines to transport gas itself, providing for a far cleaner energy source.

The gas that Con Edison, Keyspan and smaller suppliers deliver to customers in New York City comes from places throughout the southwest United States and Canada -- a domestic marketplace impervious to foreign competition. Some of the gas has been piped down from the waters off Sable Island, a skinny piece of land about 100 miles off the southwest coast of Nova Scotia. Once known as "the graveyard of the Atlantic" because of the hazard it posed for ships, it is now home to six gas fields.

When the drill hits the pocket, the hot gas, suddenly liberated by the reduction in pressure, rises upward to the wellhead. At Sable Island, water is removed from the gas on off shore platforms before the gas goes via pipes to Goldboro, a small town that was once the scene of a gold rush and now hopes to profit from an energy boom. There, engineers filter out byproducts and impurities, such as sand and rock. Once processed, the gas is compressed and pushed down a new set of pipelines.

In some countries, the gas is chilled to minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit to get it into liquid form. Then it is loaded on tankers and shipped. But in the United States and Canada, the gas remains in its gaseous state.

Over the last century, more than a million miles of pipeline have been built in North America, connecting hundreds of natural gas wells in the Rockies, Gulf of Mexico and Appalachian Mountain regions to the burners on your stove. Like tributaries of a river, the pipelines keep feeding into other pipelines, the gas propelled along the route by pressure. Interstate pipelines, up to 42 inches wide, feature compressor stations every 50 miles that keep the gas pressurized. At top pressure, the gas moves at a speed of roughly 30 miles per hour.

At certain central locations -– so-called hubs in Louisiana, Illinois and Ontario -- commodities traders in suits and ties take over from the engineers in jeans and t-shirts. Buying and selling multimillion dollar contracts, they act as middlemen between the energy companies that extract the gas and the major utilities that use it to supply customers with heat in the winter and a little extra electricity in the summer. Since 1990, when the government deregulated the market, just about anybody with enough money can go into business as a natural gas middleman or speculator. Buying up cheap natural gas delivery contracts and reselling them whenever prices spiked transformed Houston-based Enron Inc. from a humble pipeline company into one of the most profitable companies of the 1990s, until greed helped precipitate its fall from grace.

THROUGH THE 'CITY GATE'

The New York Mercantile Exchange, or NYMEX, is the primary scene for buying and selling natural gas contracts. Once bought, these contracts can be resold or cashed in for delivery at the Henry Hub, a convergence point for six regional pipelines located in western Louisiana. Like the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the daily price of Henry Hub contracts serves as a benchmark for the overall cost of American natural gas.

Once a utility company or major manufacturer has purchased a natural gas contract for delivery, it must find a pipeline company to bring that gas to its own pipes and storage tanks.

Years ago, these pipeline companies played the role of wholesalers, buying and selling gas at a markup. Since deregulation, they've become more like interstate trucking companies, charging only for the cost of transportation. This cost varies depending on pipeline capacity. When demand jumps, pipelines deliver gas around the clock, raising the cost for last-minute, emergency deliveries.

Only four companies currently compete to deliver natural gas from the Henry Hub to the "city gate" — industry parlance for Con Ed and Keyspan's local pipeline systems. Of these four companies, one, Tulsa-based Williams Inc., is responsible for more than 50 percent of all natural gas delivered. If Williams were to lose one of its four feeder pipelines into the city because of a malfunction or terrorist attack, New Yorkers wouldn't go through anything as sudden or catastrophic as the August 14 blackout, but they would experience a sudden jump in energy prices.

While few worry about the overall long-term supply being in danger of depletion -- gas is a relatively abundant resource, and has a "large volume" of undiscovered reserves, according to the U.S. Department of Energy -- there is great concern about the current capacity of regional pipelines to bring enough gas to New York in order to meet the increasing local demand.

A number of new pipeline projects could boost the flow of natural gas into New York City. The 2002 State Energy Plan lists more than ten projects approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. "We're going to need more [system] capacity if we want more market growth," says Mike Scott, author of the State Energy Plan's chapter on natural gas infrastructure.

Karl Brack, spokesman for Columbia Gas Transmission, is more blunt: "There simply is not enough [pipeline] capacity to meet the needs of the region," says Brack, whose Virginia-based company is preparing to build a pipeline connecting downstate New York with a Canadian pipeline running under Lake Ontario.

When the gas crosses the "city gate," local distributors, such as Con Edison and Keyspan, add mercaptan, the chemical that gives gas that rotten egg smell. This is a safety measure; without such an additive natural gas is odorless and colorless so it would be impossible to detect a possibly deadly leak.

In New York City, the gas stays underground. It moves into local pipes called mains, running under streets and passing through emergency shutoff valves. One final branch, about an inch in diameter, brings the gas to the Queens Village home, where it may be used for heating and drying clothes, as well as cooking.

Although Con Edison and Keyspan divide the city in terms of service — Con Edison serving Manhattan, Bronx and portions of Queens, Keyspan serving the remainder — New York is one of the few states where residents have the ability to choose their local gas provider. In other words, outside companies can deliver gas via Keyspan's or Con Edison's local pipeline system just as telephone companies can deliver long distance service via Verizon's local telephone network. But, to date, this competition has played out more on paper than in reality.

THE MARKET

New York, once a laggard in natural gas demand, now accounts for six percent of nationwide natural gas consumption, compared with five percent for petroleum and one percent for coal, according to the New York State Energy Research and Development Association.

The increased demand has contributed to the upward drift in prices and the growing concern about local supply. New Yorkers already reeling from the August blackout could be in for a second shock this winter. If cold weather forces Con Edison and Keyspan to deplete their winter reserves, New Yorkers could see their winter energy bills spike even higher than they did three winters ago. Then, the utilities had to supplement their supplies and were forced to pay two to three times the normal wholesale rate. As always, the utilities passed the cost along to their customers, who wondered why their electric and gas bills had suddenly doubled.

To avoid yet another energy ambush, government agencies and utility companies are slowly getting the word out about the potential for higher bills this winter.

If we get a repeat of the warm 2001-2002 winter, energy prices should remain elevated but stable. If we get a repeat of last winter's cold weather, things could get ugly even for heating oil users. With natural gas now qualifying as the number one fuel for local power plants — 28 percent of all electricity used in the state comes from generators powered by natural gas, says the New York State Energy Research and Development Association — everyone is a natural gas user nowadays.

That's quite a change from the days when oil workers treated natural gas as garbage.

The Alarming Report About The EPA's Response To 9/11

When the Environmental Protection Agency's Office of the Inspector General released its long-awaited report on the agency's response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, reporters seized on a startling allegation -- that White House officials and former EPA director Christine Todd Whitman conspired to downplay the environmental impact of the World Trade Center collapse in the days immediately following the attacks. They offered reassurance without the proper evidence to do so.