The Alarming Report About The EPA's Response To 9/11

When the Environmental Protection Agency's Office of the Inspector General released its long-awaited report on the agency's response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, reporters seized on a startling allegation -- that White House officials and former EPA director Christine Todd Whitman conspired to downplay the environmental impact of the World Trade Center collapse in the days immediately following the attacks. They offered reassurance without the proper evidence to do so.

But those who take a tour through the remaining 164 pages of the report might come out even more outraged and alarmed. If anything, the recent uproar over what the White House suppressed and when it suppressed it draws attention away from the report's deeper revelation, something Gotham Gazette writer Eric Goldstein noted in this space nearly a year ago. Though in many parts heroic, the city, state and federal government's collective environmental response to the September 11 attacks exhibited a glaring " leadership gap."

This gap is particularly troubling for New Yorkers. Though September 11 already ranks as the worst single-day environmental catastrophe to befall the city, it doesn't take much imagination to conjure up something that could be even worse. From the October, 2001, anthrax scare to ongoing concerns over a Chernobyl-level disaster at the upriver Indian Point nuclear power plant, New Yorkers are waking to the implications of treating the environment and public health as an afterthought during disaster recovery.

Step One: Closing the Leadership Gap

Two chapters of the report, about 20 pages total, defend the legality of the Environmental Protection Agency's behavior at and around Ground Zero, while at the same time chiding it for not being "proactive" enough in asserting its authority in various realms. One realm in particular, cleanup of indoor spaces contaminated by the attack, comes under special scrutiny. The report notes that in the first months after the attack agency press releases "deferred to the New York City Department of Health guidance even though EPA's position on indoor cleanup was different [from] the city's."

When it comes to explaining this institutional timidity, however, the report goes timid itself: "EPA does not have clear statutory authority to establish and enforce health-based regulatory standard for indoor air," the report notes. "Neither CERCLA [Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act] nor NCP [National Contingency Plan] obligate EPA to undertake response actions."

Buried on page 27, this explanation may turn out to be one true smoking gun in the entire document. Edward P. Richards, professor and director of the Louisiana State University's Law, Science and Public Health program, offers a plain English translation.

"The feds aren't really set up to manage a crisis," says Richards. "They really depend on the locals."

Two years after the attacks, New Yorkers can look back on the events of September 11, 2001, in a less emotional light. In addition to soul-stirring acts of heroism, it is now easy to see the naked battle for political supremacy at the World Trade Center site in the minutes, hours and days following the first airliner impact.

It shouldn’t be too surprising that this battle favored the locals — former Mayor Rudy Giuliani, city ironworkers, the New York City Department of Design and Construction — over the visitors — the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Occupational Safety & Health Administration, and the EPA. The raw emotions stirred up by the attacks prompted a can-do spirit which federal agencies were loathe to undermine.

Still, by deferring to local authority, mistakes were made. By January, complaints over the city's delegation of actual cleanup responsibility to individual owners and tenants in buildings surrounding Ground Zero prompted Jerrold Nadler, the U.S. Representative whose district includes Ground Zero, to cite a "gross disparity" in the EPA's handling of the Lower Manhattan cleanup compared with other contaminated sites around the country.

"New York was at the center of one of the most calamitous events in American history, and the EPA has essentially walked away," Nadler said in a February 11, 2002, testimony before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. Nadler's outcry would lead to the creation of a multi-agency cleanup effort led by EPA. Still, complaints lingered, and it wasn't until August, 2002 that the agency launched a full building-by-building cleanup process.

Aside from federal reliance on local responders and local contractors, the report also downplays the agency's own second-tier status within the Bush Administration. It notes that in July of last year, the Bush Administration, via the Department of Homeland Security, designated the EPA as the primary agency "responsible for decontamination of affected buildings and neighborhoods" and "determining when it is safe to return to those areas" after a terrorist attack, but neglects to mention the already-overburdened Office of Criminal Enforcement, Forensics and Testing, the internal division that handles such matters.

In July of this year, a report in CongressDaily revealed that the Office of Criminal Enforcement, Forensics and Testing currently faces a backlog of more than 1,500 cases as the Bush Administration has denied repeated requests to boost the division's manpower from 200 to 400 agents. Six Democratic senators and Vermont Independent Senator James Jeffords subsequently issued a joint request that the EPA's Inspector General investigate whether even the former count was inflated by Bush staffers.

The EPA, in other words, may lacks the staff to be a major player in any post-disaster response scenario.

Step Two: Closing the Liability Gap

Admittedly, if EPA officials had declared the World Trade Center and much of Lower Manhattan a Superfund site on September 12, 2001, they would have faced far more heat then than they do now. Such assertiveness, however, might prove necessary in future situations where no single mayor or governor holds uniform jurisdiction.

It might also preclude what is already shaping up to be a cruel irony of the September 11 attacks: New York City residents, in addition to suffering the worst psychological and health effects of the September 11 attacks, may wind up paying the legal bill as well.

Professor Richards notes that the EPA, because of the judicial branch's traditional deference to the executive branch on matters of policy, provides a less inviting target for post-disaster legal claims than the City of New York.

"Getting damages out of the federal government is a pretty unusual circumstance," Roberts says. "It happens, but you have to show the government used negligence and it wasn't just a policy decision. After all, the word policy implies that you have some sort of tradeoff — public health vs. public security — that the government is taking into account when it makes a decision."

Because the EPA took a back seat to the New York City Departments of Health and Environmental Protection in the first months after the attacks, however, this shield has no effect. U.S. District Judge Alvin Hellerstein recently served notice that local government agencies will have less luck pleading "governmental immunity" when he gave the green light to a victims' lawsuit against the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

Is New York City next in line? Judging by the feisty response of Kenneth Becker, chief of the World Trade Center Unit in the New York City Law Department, the city is already preparing a major battle. Taking issue with the agency's attempts to shift the blame on issues such as respirator usage at Ground Zero and testing for concrete dust and other non-asbestos particles, Becker's rebuttals merit their own special 10-age appendix within the report.

"The City believes EPA Region 2's comment that it did not want to take a more assertive stance because it would create a confrontation is not valid," writes Becker. "In fact, when at a point in time during the Response Effort, EPA suggested that its functions be transitioned to a contractor, the City urged the EPA not to do this and to continue to maintain an on-site presence and be part of the team."

Jay Cohen, deputy chief of the Law Department's World Trade Center Unit, says the report reveals no evidence of city negligence. "To the contrary," Cohen writes, "the report demonstrates the proactive approach of New York City agencies, in particular the Department of Environmental Protection."

Even so, the conflicting views encased in the report remains a sore point. Was the EPA too deferential to local authority or was it too ready to leave its local counterparts in the toxic dust? The report suggests that, unless bureaucratic tensions are resolved, future environmental disasters may look far too much like September 11, 2001.

The Power Broker Revisited

At a recent meeting in the Lower East Side about how to spend remaining federal funds to rebuild lower Manhattan, a group of protesters gathered outside, angry about how the money has been allocated so far. To rebuild, City Councilmember Margarita Lopez yelled, "you don't need a power broker. The only thing you need to do is talk to people in the community."

For many New Yorkers, the phrase "power broker" means one person: Robert Moses. And he wasn't known for talking to communities. He was known for "getting things done."

From 1924 until 1968, Moses built public works in the city and state, including seven city bridges, two tunnels under the East River, 658 playgrounds and 416 miles of parkways. He also destroyed neighborhoods, dislocating thousands, to make way for his expressways. His biographer, Robert Caro, wrote in The Power Broker that Moses was fond of saying, "When you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax." and "You can't make an omelet without breaking eggs."

In the decades since Moses' day, planning in New York City shifted to a community review process, to give neighborhoods more of a say in their own future. This has also meant that far fewer huge public works get built. But as plans develop for massive public building projects in lower Manhattan, for the 2012 Olympic bid, and on the island's far West Side, some say that New York City could learn from Moses' methods, while others worry that the power broker's worst tactics may already be at work.

Robert Moses

In The Power Broker, Caro writes that Moses was "America's greatest builder. He was the shaper of the greatest city in the New World." New Yorkers never elected Moses to anything, but he was able to amass power as governor after governor and mayor after mayor appointed him to important positions - at different points in his career, Moses was head of state and city parks, chair of the city's slum clearance commission, construction coordinator, and once occupied 12 different positions simultaneously. Moses used the power of the public authority to sell bonds, build roads, collect tolls and put the money back in to new projects.

Moses fell from power in the late 1960s and died in 1981, but his influence hangs over many current debates. In fact, New Yorkers are now discussing the future of some of the projects that Moses himself built, including Lincoln Center, the cultural hub that Moses created as a 1960s urban renewal project. And in the South Bronx, community groups have created a plan to tear down the Sheridan Expressway, a 1.25 mile-long part of Moses' legacy.

| Reading NYC Robert Caro's biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker, is Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club selection for August -- join us at the Borders bookstore at 100 Broadway (across from Trinity Church) at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, August 20 for a discussion of the book. |

Despite an incredible record of "getting things done," not everything that Moses proposed was built.

In fact, he lost a major public battle to build an expressway through lower Manhattan, after author and urban planner Jane Jacobs galvanized West Villagers and other lower Manhattan residents to stop the highway. The great builder also never succeeded in forging a road down Fire Island - in 1964, the Fire Island National Seashore was established instead. And Moses' Coliseum at Columbus Circle, which Caro called a "glowering exhibition tower whose name reveals Moses' preoccupation with achieving an immortality like that conferred on the Caesars of Rome," was torn down in 2000 to make way for the new Columbus Center.

Moses-sized Projects Today: Olympics and the West Side

But while the Coliseum may have fallen, the figure of Moses continues to inspire debates and influence projects today. When now deputy mayor Daniel Doctoroff and a group of developers, politicians and planners first assembled the bid to bring the 2012 Olympics to New York City, the New York Observer called the group "a hundred-headed Robert Moses... frustrated by decades of political paralysis and determined to resuscitate the long-vanished art of getting things built on a grand scale with brute political force."

When Moses was president of the New York World's Fair of 1964-65, he fought to turn the exposition's fairgrounds– shifting money around in secret, according to his biographer Robert Caro –into Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. When the park was dedicated, Moses said that the fair had "ushered in, at the very geographical and population center of New York, on the scene of a notorious ash dump, one of the very great municipal parks of our country."

The Olympics plan - which backers say would, like the World's Fair, use an international event as a catalyst for major city improvements - includes joining the two now-contaminated lakes in Moses' Flushing Meadows-Corona Park into one big venue for rowing competitions. It would also build an Olympic Village in Queens, extend the #7 line westward, and create an 86,000-seat Olympic Stadium on the far West Side of Manhattan.

The Olympics bid garnered New York the U.S. nomination for the games, but the city must compete against a dozen cities around the world before the International Olympic Committee selects a winner in 2005. Meanwhile, city officials say that construction on some of the Olympics plans cannot wait until the committee makes its choice.

The Olympic stadium is just one component of the Bloomberg administration's plans for the West Side, including building green spaces, rezoning the garment district, and using bonuses to encourage high-rise development and new office buildings. Residents have said that a stadium -- which together with an expanded Jacob Javits Center would extend 11 city blocks -- and new business district could bring more traffic, cause rents to go up and displace residents and small businesses.

According to Hunter College professor Tom Angotti, Robert Moses would have been happy to see the new plans for Manhattan's far West Side, which "would basically bring an end to Hells Kitchen, the historic rough-and-tumble neighborhood... that's been depleted of its population over the last century, cut up by giant renewal projects." In an article for Gotham Gazette, Angotti imagined a conversation about the project with Moses, who he depicts as saying, "[The mayor] did it my way. Didn't listen to those people who live there. What do they know anyway? You have to think big and think about the future! You want to expand midtown to the west, just do it! How do you think we got Lincoln Center?"

Ron Shiffman, director of the Pratt Institute for Community and Environmental Development, said that it is too early to tell whether the Olympics plans will truly benefit the city or will become the newest example of using Moses' "meat ax" to decide a neighborhood's future. The Olympics could create projects that leave the city a valuable legacy, but, he said, "if they don't engage in a planning process with the people who live there, then the project could emerge into the kind of planning that Moses was engaged in."

Rebuilding Downtown

As planning continues on the city's other Moses-sized project, rebuilding Ground Zero, many details about the project are still being debated nearly two years after the attacks. They are being discussed by master plan architect Daniel Libeskind, World Trade Center site owner the Port Authority, lease-holder Larry Silverstein, state and city officials, family members, residents, and many others. At many points during the rebuilding process, people have asked: who exactly is in charge here?

"New Yorkers are asking if our city needs another Robert Moses," Alexander Garvin wrote in Topic Magazine. "It is an appropriate question: Despite his mistakes and his failures, nobody, not even Baron Haussmann in 19th Century Paris, has ever done more to improve a city," added Garvin, who until this spring worked as top planner for the head rebuilding agency, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and also developed the plans for the 2012 Olympic bid. "In truth, Moses was not omnipotent, but rather an unusually gifted public servant who had mastered the Art of Getting Things Done. That art deserves attention more than ever."

Garvin wrote that the city should learn from Moses how to push forward with an agenda that many can agree on, how to compromise (as Moses did to build his Coliseum at Columbus Circle), and work for the kind of quality of design that Moses championed at Jones Beach. At the same time, Garvin wrote, any planning should make sure to include the public that Moses once sought to shut out of decisions.

But some involved in rebuilding say that it doesn't make sense to look back on the Moses method at all. Shiffman said that instead, New Yorkers should be proud of the distinctly non-Moses-like form that rebuilding the city has taken so far. "Given the fact that the World Trade Center site is controlled by the Port Authority and Larry Silverstein, it has been much more of a democratic process of planning than we have seen in a long time. Civic groups developed the framework and the standards by which the LMDC has to operate. And you can't forget July 15 of last year, when people turned down the original plans [at the Listening to the City town hall meeting]."

As Michael Kuo, a 9/11 victims' family member and a planner for the rebuilding project Imagine New York, said, "I think we are in a different era now."

* * * * * * * * * *

RELATED ARTICLE: A Community Plan for Moses’ â€Highway to Nowhere’

* * * * * * * * * *

Environmental Impact of Rebuilding Lower Manhattan

A new and possibly more contentious phase of the Lower Manhattan rebuilding effort is now beginning, as formal environmental reviews for key elements of the unprecedented reconstruction projects move into the spotlight.

In October, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation is scheduled to release a draft environmental impact statement, covering its proposed plan for a memorial and for the redevelopment of the World Trade Center site. That document will trigger a formal period of public comment, as well as public hearings, that are likely to focus on key details of the redevelopment plan for the 16 acre site that had been home to the twin towers until they were destroyed in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Meanwhile, the environmental review of a separate but related project -- the reconstruction and possible underground tunneling for West Street, which runs along the trade center's western edge -- is also expected to gain increased public scrutiny this fall.

As decision-makers begin their formal environmental reviews -- theoretically before making important design decisions about the redevelopment project and the adjacent roadway rebuilding -- the possibilities for conflict between environmental and civic groups on the one hand, and commercial interests on the other, seem increasingly likely.

WORLD TRADE CENTER MEMORIAL AND REDEVOPMENT PLAN

Public attention will of course continue to be centered on the planned memorial and redevelopment at the 16 acre World Trade Center site itself. The formal environmental review of this project is being coordinated by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, a subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation, although the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Governor George Pataki, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and others will play key behind-the-scenes roles.

The "proposed action" that is the subject of the forthcoming draft environmental impact statement includes a World Trade Center memorial and related improvements, up to 10 million square feet of office space, up to 1 million square feet of retail space, up to 1 million square feet of conference center and hotel facilities, as well as additional open space and cultural facilities.

Earlier this year, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation outlined its planned review process, listing the 14 city, state, bi-state and federal permits or approvals that may be required for whatever project is ultimately built on the trade center site. And it summarized the topics that the environmental impact statement will discuss, including among other things expected impacts on open space and recreational facilities, neighborhood character, traffic, noise, air quality and waste disposal.

The environmental study will also identify adverse consequences from the proposed project, discuss alternatives to the proposed action and describe mitigation measures that could minimize environmental harm.

In accordance with state and federal environmental laws, this environmental study will be released in draft form and be the subject of a formal public review period. After that, the development corporation will respond to comments and possibly modify elements of the analysis and the project before issuing a final environmental impact statement, seeking permits and approvals for the project and beginning actual construction.

The final environmental review is projected to be completed, in an accelerated process, sometime early next year. Governor George Pataki has announced plans for groundbreaking ceremonies to take place in September 2004.

ISSUES OF PUBLIC CONCERN

The development agency received wide-ranging reaction to its plan. One major concern of environmental and civic advocates is that the environmental study as currently designed will not examine options that would reduce the amount of office space to be created at the trade center site. The proposed 10 million square feet of office space has been a cornerstone of leaseholder Larry A. Silverstein's plans for rebuilding.

"The program for office space and retail space should be developed in light of the total needs for office space and retail for Lower Manhattan,” representatives of the Civic Alliance wrote in its formal response, “not according to leaseholder obligations to rebuild an office complex that dates back to the 1960s and embodies assumptions about urban revitalization vintage to that era." The Civic Alliance recommended that the environmental impact statement “evaluate...options for significantly less amounts of office and retail, and greater amounts of cultural, civic and open space" at the 16 acre site.

Another concern, once the rebuilding is under way, is how solid waste from the redeveloped trade center site (and the rest of Lower Manhattan) will be managed, and where energy needed for the new development will be generated. Environmental justice advocates warn that the redevelopment project should not place additional environmental burdens on other city neighborhoods.

A good plan for Lower Manhattan means a plan that will not require the building of yet another power plant or solid waste management facility in a poor neighborhood in order to meet the greater demands, says Gail Suchman, an attorney at New York Lawyers For the Public Interest, who represents the Organization of Waterfront Neighborhoods and other community groups.

"We hope and expect that this new project will be a world-class model for green building and energy efficiency," says Ashok Gupta, energy expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council (where I work). Gupta and other advocates note that the development corporation’s plans promise that they will “consider” green building and sustainability principles in the environmental review. But energy specialists caution that unless a strong set of such design guidelines are incorporated into the draft environmental impact statement, the prospects for making this new development a show-case for energy-efficiency would dim considerably.

Environmental and civic groups are also urging that the environmental review analyze "truckless goods delivery" for the trade center site and study incentives to reduce traffic, encourage walking and reduce pollution in and around the site. Many of these organizations also remain concerned that environmental review for the trade center site explicitly take into account the separate environmental reviews being conducted for other closely-linked projects (e.g., the permanent PATH station , the Fulton Street transit center, the West Street reconstruction) to insure that these projects do not proceed in isolation and that the cumulative impacts of the combined projects are fully analyzed.

In response to these and other challenges, the staff of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation remains optimistic.

"We were not surprised by the substantive points in the comments we received and we are going to explore alternatives that consider additional areas for commercial development outside of the 16 acre site," says LMDC Counsel Irene Cheng.

But the recent report that two insurance companies -- Allianz and AXA -- may block plans to demolish the damaged Deutsche Bank building, just south of the Trade Center site, could further complicate any proposal to disperse office and retail space beyond the 16 acres.

"As this is hardly a routine development project," the Bar Association’s Task Force the environmental review process should not be viewed as routine."

WEST STREET CONTROVERSY

On a different track, and outside of the public limelight, the New York State Department of Transportation is advancing a plan to reconstruct West Street (also known as route 9A) and to replace it with a covered tunnel that could cost up to $860 million.

At a recently held but little-publicized "public information" session, state transportation officials presented their plan for an underground bypass tunnel to be built -- during a five year construction period -- as a replacement for West Street. The only other option that would be considered by the transportation department in its environmental review process is a "no-build" alternative. Transportation officials suggested that the massive tunnel project would create a park-like setting above ground, provide more space for pedestrians and accommodate increased visitors.

But in contrast to the openness that environmental and civic groups believe the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation has displayed as that agency has advanced its redevelopment and memorial work, the State Department Of Transportation's environmental review plans for the West Street project have come under sharp criticism.

As things now stand, the state transportation department will conduct no public scoping process for its environmental review (since it claims only to be preparing a "supplemental" environmental impact statement to an eight year old environmental review document). The agency does not plan to study any low-scale alternatives to the tunnel project. Nor does the state believe it must even hold a public hearing when it releases its supplemental draft environmental impact statement next year.

Not surprisingly, public opposition is mounting. Local elected officials, including Representative Jerrold Nadler, Assemblymember Deborah Glick, and City Councilmember Alan Gerson, are expressing skepticism. And in a July 31st letter to State Transportation Commissioner Joseph Boardman, six transportation and environmental organizations -- Coalition to Save West Street, NYPIRG Straphangers' Campaign, Tri-State Transportation Campaign, Enviornmental Defense, NRDC and Tranportation Alternatives -- criticized both the process and the substance of the West Street reconstruction project.

Of course, the new State DOT plan for Route 9A is not the first time engineers have sought to address traffic issues along Manhattan's west side.

In the l930's master planner Robert Moses sought to advance his "West Side Improvement" project, including a five-mile expressway from the southern tip of Manhattan to 72nd Street. The story is recounted by Robert Caro is his award-winning biography of Robert Moses: "The Powerbroker."

"The West Side Improvement had two purposes," Mr.Caro writes: "to reclaim Manhattan's waterfront for its people, and to alleviate Manhattan's traffic congestion. It was to achieve these purposes that Robert Moses spent an incredibly large sum of money."

"But despite that expenditure -- all but inconceivable in terms of urban spending of that era -- the first of the two purposes was achieved only in part, " Mr.Caro concludes. "(I)nstead of reclaiming the waterfront for Manhattan's people, the West Side Improvement deprived them of it. And the second of the two purposes was not achieved at all."

With that history in mind, environmental and transportation groups are now gearing up for a fall campaign to secure a full-scale environmental review of the State Department of Transportation proposal for reconstructing West Street.

Eric Goldstein is co-director of the urban program at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Studying How To Avoid Blackouts

New York's blackouts are legendary. In 1965, a single transmission line failed in Toronto, Canada setting off a domino effect that within 15 minutes left 30 million people from Staten Island to Ontario in darkness. A movie was made about it starring Doris Day.

New York's blackouts are legendary. In 1965, a single transmission line failed in Toronto, Canada setting off a domino effect that within 15 minutes left 30 million people from Staten Island to Ontario in darkness. A movie was made about it starring Doris Day.

Though steps were taken to prevent local outages from overloading the region's power grid again, another blackout occurred on a sweltering summer night in 1977, when a lightning storm short-circuited the city. It was the summer of the Son of Sam and an era of fiscal crisis. The blackout brought vandalism, violence and arson. According to the Blackout History Project, police arrested more than 3,700 people, but could not control rampaging mobs in some parts of the city. This blackout did not lead to a Doris Day movie.

It might surprise New Yorkers to learn that, a quarter century later, there are some 2,000 power-line failures a year in the city. Consumers do not notice most of them because New York's electric system, which industry rating groups say is the most reliable in the country, is designed so that if one power line fails, another picks up the slack.

Still, the problem of blackouts persists. In 1999, cables burned and overheated, casting a shroud of darkness over the Washington Heights and Inwood areas of Manhattan for 18 hours -- the largest prolonged blackout since 1977. In 2001, equipment failures led to scattered outages in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx and Westchester. And last summer, a fire at a Con Edison transformer cut electricity for seven hours to Manhattan's East Side.

A variety of things can cause power outages, including equipment failures, fires and weather conditions, such as lightning. The lights went out in Washington Heights on a day when electricity usage topped 11,850 megawatts, then a Con Edison record. And so conservation efforts can help avert power outages.

But cable failure played a major role in the Washington Heights power failure and has contributed to many problems that consumers never notice. With that in mind, Con Edison and other utilities that rely on underground cables want to learn how to prevent cable failures before they occur. That is why they have opened a laboratory in the Bronx to find out what makes seemingly good cables go bad.

THE ELECTRIC UNDERGROUND

Con Edison maintains some 126,000 miles of cables, about two thirds of which are underground and so fairly immune to lightning and other vagaries of the weather. High voltage transmission lines bring electricity from generators to local sub-stations. Medium voltage lines, called feeder cables, then distribute power to transformer boxes. From there, it is delivered by low-voltage lines to individual homes and offices.

The utility divides its service area into 78 networks, 33 of them in Manhattan. Each network contains from six to 24 feeder cables. One or two downed feeders within a network may go unnoticed, but if more fail it can overload the network and lead to outages.

Therefore, the best way to prevent outages is to identify vulnerable cables before they fail. "That's the Holy Grail," said Con Edison spokesman Chris Olert. "Knowing, 'Well, that cable is going to fail in eight hours or a week.'"

Even though utilities can be allowed to pass the costs of replaced cables on to ratepayers, they prefer to replace only those cables most likely to fail, rather than be forced to replace hundreds of miles of cable that could still provide years of services. And since consumers pay for new cables in the form of higher electric bills, they may endorse this conservative approach - unless their lights go out.

"We did testing on cable installed in the 1920s. We pulled it out, and it was as good as new," said George Murray, a cable engineer and the lab's acting director. "So, rather than replace a cable because of some arbitrary standard like age, we want to leave that cable in service and target cables about to fail or give us a problem."

But preventing outages is not the only reason to replace cables, says Jason K. Babbie, a policy analyst with the New York Public Interest Research Group. He says older cables tend to leak more power than newer ones and that upgrading cables would improve efficiency, save energy and alleviate the need to build more generators and sub-stations.

"While a cable from the 1920s may still be working that doesn't mean it's working efficiently," he said. "One of the criteria that Con Ed should be considering is how to improve the efficiency of the system as a whole."

Environmental benefits may also come from replacing older cables. Paper insulation in older cables contains oil that can leak into the ground in small amounts. Lead casing can also pose a risk. Newer cables are insulated with plastic.

Nevertheless, at the moment Con Ed's focus is on figuring out which are the cables about to give. According to Murray, small manufacturing differences in cables can affect how they perform under duress. A common cause of cable failure is what Con Edison engineers call "trauma," physical damage usually done by workers making repairs to the snarl of cables, pipes and fiber optic wiring that compete for space beneath the city's streets. (To view a cross-section of the city's underbelly, visit National Geographic's site)

Rock salt, used to clear streets of snow and ice, also can wreak havoc on cables. Salt is not only corrosive, but also conductive. This means that salty run-off after snowstorms can eat through insulation and carry current between conductors and to the ground. "The more salt in winter, the more failures we get in the spring," said Murray. As a result, there have been a particularly large number of failures this year although the public has noticed few if any of them.

MOCK MANHOLES AND AUTOPSIES FOR CABLES

The $10 million Cable &Splice Center for Excellence on Con Ed's Van Nest campus near the 180th Street subway stop in the Bronx is a joint project of Con Edison and the Electric Power Research Institute, a national energy research and development organization. At the heart of the new facility is a mock manhole encased in soil where the climate can be controlled to mimic conditions underground. The lab also includes four voltage-testing areas, a diagnostic lab and an impulse generator that can simulate the effects of lightning. The lab's total of three manholes enable engineers to study how moisture and other weather conditions can affect cable joints, which are typically found in manholes. Minus rats, cockroaches, water bugs, methane gas buildup, tree roots, garbage and so forth, the manholes are exact replicas of their underground counterparts, Murray said.

The lab is outfitted with an array of equipment painted in cheerful primary colors, including bright red transformers that can step up electricity to 120,000 volts -- three to ten times the charge that normally runs through the city's distribution lines.

"It's like an autopsy for cables. It's where cables go to die," said Olert.

Con Edison and its fellow utilities hope the lab's efforts will enable it to develop a diagnostic system to repair legacy cables more efficiently. "You have to look at a lot of different factors," said Walter Zinger an electrical engineer with the Electric Power Research Institute who is coordinating the lab's work with that of other partners in the institute's Cable Testing Network. "Say the normal failure probability is 'X' and in this condition it is '10X.' You still don't want to replace all those cables because the probability [of failure] is still one in 100 . . . And that's why we do this."

The lab's first task will be to research feeder cables of the kind blamed for the power outage in Washington Heights in 1999.

RELIABILITY AND EFFICIENCY

Capital spending by utilities has gone down in the past several years but reliability has improved, with Con Edison achieving the highest reliability index in the state.

A study (in pdf format) released by the New York State Energy Planning Board in 2000 found that New York City had a significantly lower rate of service interruptions per customer than the rest of the state. It also found that, although capital investments in the power transmission system declined dramatically from 1988 to 1998 (from $304.4 million in constant 1998 dollars to just $90 million), the reliability of the state's transmission system improved during the same period.

"This suggests that transmission system expenditures are being used more effectively, or that these factors have less of an impact on actual reliability than other factors," the report concluded. Spending on operations and maintenance remained constant during the period studied.

But failures still occur. Following the Washington Heights blackout, the state Public Service Commission issued a report calling on Con Edison to take a number of steps to prevent further outages and called for "accelerated replacement of older, paper wrapped feeder cables." Con Edison reportedly agreed to spend $2.4 billion over five years in capital improvements to its distribution system.

David Flanagan, director of public information for the commission said that since then, the utility has been keeping its commitments.

Some question, though, whether the system will continue to be reliable without some increase in spending. A spokesperson for Assemblymember Paul Tonko, chair of the energy committee, said Tonko believes the decline in capital spending and in replacing skilled utility workers could lead to problems down the road.

Danny Peralta lived in Washington Heights during the blackout in 1999 and remembers families sleeping in neighborhood parks to keep cool. He worries that Con Edison does not invest as much in neighborhoods like his as it does in other parts of the city. "There were parts of the city where the lights went back on. My neighborhood was one of the last to get light. It spoke volumes about the politics of the city," he said.

Con Ed says that failures may occur more frequently outside midtown and downtown Manhattan because the networks in the outlying areas cover greater distances. As a result there are more cables and connections between the local sub-stations and the homes and offices they serve and so a greater statistical probability that one will fail, Murray said.

In the longer term, research in cable technology could eventually save money. Tonko and others think that super conductivity cables, which are currently under development and can carry five times as much electricity as copper wires of the same size, might some day open New York's system to more distant suppliers and thereby encourage greater competition, bringing down electricity prices. "If you had super conductivity coming into New York City and Long Island, you would then have more capacity," Tonko said. "If you have greater capacity to deliver you open up the system."

It could be decades, though, before this technology is ready for general use. "As the Cable Center evolves, we may find new uses for its testing equipment," said Olert. But for now, the lab's research is focused on maintaining existing cables and keeping the city switched on.

Editor's Note: This article was first posted on our site on Monday, August 11, 2003 -- three days before the blackout of 2003.

RELATED ARTICLE: After The Blackout - Going Back To The Experts

Death of Seneca Village

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

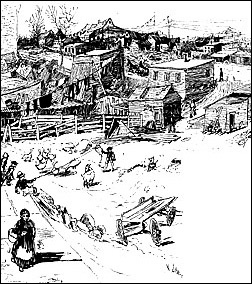

Turning Manhattan swampland into Central Park’s vast acres of woodlands, meadows and ponds took16 years and cost $14 million. But building Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s “Greensward Plan” was not without a human cost as well. More than 1,600 people were displaced by Central Park, including Manhattan’s first known community of African-American property owners, Seneca Village.

From 1825 to 1857, Seneca Village was located between 82nd and 89th Streets at Seventh and Eighth Avenues. The New York State Census of 1855 reported that 264 people, largely African-Americans but also Irish and German immigrants, lived in Seneca Village. By the time it was destroyed, the village had grown to include three churches, a school and several cemeteries.

There are many theories about how Seneca Village got its name, according to the New York Historical Society: it could have been named for the Seneca tribe of Native Americans, or a distortion of the word “Senegal,” where many of the village’s residents may have come from. It also may have been a code word used by Underground Railroad fugitives, or named in homage to Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, whose book Seneca’s Morals was popular among African American activists.

The community was founded on September 27, 1825 when an African American former boot black named Andrew Williams bought six lots of land for $125, and another African American laborer, named Epiphany Davis, bought 12, for $578. The trustees of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church purchased six lots of land on the same day.

Buying property in Seneca Village was relatively inexpensive compared to prices downtown, and by 1850, African Americans in Seneca Village were 39 times more likely to own property than African Americans in other parts of the city. This made them more able to participate in civic life -- at the time, the New York State Constitution of 1821 required that African-American males had to own $250 in property in order to vote.

In 1853, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church built a church in Seneca Village, and, according to a newspaper account of the time, church officials laid a special cornerstone that contained a Bible, a hymn book, the rules of the church, copies of the New York Tribune and the New York Sun, and a letter with the names of the church’s five trustees.

The new church would not stand long enough for the cornerstone’s contents to become more than a few years old. The state legislature set aside the land for Central Park in the same year that the church was built. During the 1850s, newspaper articles described Seneca Village as “Nigger Village.” The New York Daily Times wrote on July 9, 1856, about Seneca villagers, “The policemen find it difficult to persuade them out of the idea which has possessed their simple minds, that the sole object of the authorities in making the Park is to procure their expulsion from the homes which they occupy.”

The government used the power of eminent domain to force the people of Seneca Village out of the area, giving them the final notice to leave in the summer of 1856. Those who owned property were compensated, but many fought to keep their land or get a better payment. The residents of Seneca Village did not re-establish their community in another place, and instead scattered throughout the city.

The story of the village that was destroyed to make way for New York City's great park went largely untold until recently, and it was not until 2001 that the Central Park Conservancy put a plaque commemorating the lost community in the park.

An Escape from Reality

William Glackens, 1912, oil on canvas.

Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

On September 11, 2002, feeling an obligation to quietly commemorate the events of one year before, I set aside an hour to think about why I love New York. Central Park, the only backyard I have ever known, seemed the perfect place for such ruminations, so I settled down in Strawberry Fields and looked around. The park, as it turned out, was the absolute wrong place for me to celebrate the city. Complete strangers were smiling at one another! People were walking slowly, strolling even. This was not my New York. Sure, cabs were still racing through the 86th Street transverse and I spotted more than a few giant rats, but somehow, like magic, things were different in the park. That is exactly what I’ve loved about it, though, throughout my 20 years growing up here: The park offers me a place where the city rules are temporarily lifted.

Perhaps the change in rules was most apparent when I was young, because it was literal then. I did not have to hold my mother’s hand for fear of being "taken," there were no real streets to cross after looking both ways, and so I was pretty much free. In warm weather, I had the "ancient playground," where I filled my shoes and socks with sand within ten seconds of arriving. I had mountainous rocks to scale and Balto the brave medicine dog to inspire my adventures.

In the winter, there was sledding to do. Nothing else in Manhattan can offer a 5-year-old such abandon as flying down a hill, spinning in a saucer, until she runs out of steam or hits something. Nothing.

As I got older, and the intellectual and social pressures of New York began to pile up, I enjoyed the physical challenges offered by the park. For a respite from term papers about transcendentalism and music theory classes, I struggled to bike up the "big hill" on 110th Street without giving up and walking. And if the boy I liked at school turned out to prefer my best friend, I could always try to rollerblade down the hill by the "Stuart Little" pond without slowing down (I never quite mastered that). These days, my escapes from the fast-paced city involve trying to jog around the reservoir without being passed by anyone over 70 years old.

For me, the park is about suspended reality. For groups of middle schoolers at 1 a.m. on a Friday night, some controlled substance laws are temporarily forgotten (or so I hear). For young couples on an afternoon picnic, the complications of serious relationships are ignored for a while.

I now attend a college out west, where the whole enormous campus might as well be called a park. I can take pleasure in outdoor activities there, but something is missing. Without the nearby noise of 5th Avenue and the cerebral Metropolitan Museum, the park would not be so different, and without that contrast, the magic might be lost.

Sarah Lustbader, a NYC native and a student at Stanford University, is the 2003 Lenore Chester Searchlight intern for Gotham Gazette.

Recycling Revived

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg, as part of the last-minute budget negotiations with the City Council, agreed to resume plastic recycling (suspended a year ago), end the suspension of glass and yard waste recycling in 2004, and bring back Christmas tree recycling (suspended last fall), it was a decisive reversal from 18 months earlier, when the mayor’s elimination of these programs from the city’s program sparked outrage among recycling advocates, and seemed to spell a gloomy future for recycling in the city.

"The battle was tough, but we won the war," observed City Councilmember Michael McMahon of Staten Island, chairman of the council's committee on sanitation and solid waste, and a staunch recycling proponent.

Future battles remain. One twist in the current resumption of plastic service is an awkward every-other-week pickup schedule proposed by the Department of Sanitation. According to the recent City Hall agreement, that schedule will remain in effect from the first of August to the first of April, 2004, at which point, normal weekly service is expected to resume. Despite ongoing grumbles over institutional sandbagging, most city recycling advocates and their allies in the recycling industry are willing to look past such temporary obstacles and bask in the newfound resiliency of their movement.

Since the passage of Local Law 19, the 1989 ordinance that ordered the Department of Sanitation to set up a city-wide recycling program, recycling advocates and department of sanitation officials have butted heads over how to turn coins and bottles into cash. From the sanitation department’s perspective, recycling has put a consistent drain on both manpower and equipment. From the recycler's perspective, the sanitation department's own Soviet-like mania for one-size-fits-all solutions has made it difficult to tailor the city's recycling in a way that would make it more economically productive.

"It almost seems that whenever there was a decision that needed to be made, they made the wrong decision," says Marjorie Clarke, co-chair of the New York City Waste Prevention Coalition. "You begin to wonder: This can't totally be happenstance."

The end result, from the recycling view, has been a decade-long two-steps-forward, three-steps-back process that leaves proponents habitually wary whenever money comes into the conversation. That wariness has translated into strategies designed to stress the environmental benefits of recycling in a city that rarely sees those benefits firsthand.

That unwillingness to tread the bottom line proved a major handicap, however, in the wake of September 11. Faced with a huge budget deficit, Mayor Bloomberg bought into the Department of Sanitation's plan to save the city $56 million a year by ceasing plastic, aluminum and glass recycling.

"We have two recycling programs," said Bloomberg at the time. "One that works and one that does not." He was distinguishing between profitable paper recycling and unprofitable non-paper recycling.

A June, 2002 budget compromise saved aluminum but consigned plastic and glass to oblivion.

Reforming the Ranks

Talk to most city recycling advocates, and one event from the past year stands out. In November the Citywide Recycling Advisory Board (CRAB) and the Center for Economic and Environmental Partnership (CEEP) joined together as hosts of an industry roundtable at the downtown campus of Pace University.

A national summit for recyclers, consumers of recyclable commodities and industry lobbyists, the event represented the first major attempt to solicit outside help in driving home the economic sustainability of recycling.

"The city needed more education," says Clarke, a roundtable organizer during her tenure as chair of the Manhattan Citizen's Solid Waste Advisory Board (SWAB). "I figured that other cities were doing well. All we needed to do was bring in the information."

Clarke and her fellow organizers had little difficulty getting people to show up. In questioning both the financial and environmental merits of civic recycling, Mayor Bloomberg had in effect challenged the entire industry.

"New York is a bellwether for other programs across the country," notes roundtable attendee John Burgiel, national director of solid waste management for RW Beck. A Florida-base consulting firm, RW Beck has helped cities such as Denver, Cincinnati and Buffalo structure their recycling programs.

Burgiel and others would like to remind city officials of the great big market lying just beyond the five boroughs. Instead of going for the bulk discount, paying waste haulers to take both trash and recyclables, attendees proposed pushing the city into the role of auctioneer, selling off its plastic, aluminum and glass franchises to the highest bidder.

To get an idea of how it works, look no further than Visy Paper, a local subsidiary of Australian recycling giant Pratt industries. In 1995, Visy snuck its way into a city recycling contract by forging a deal with the Economic Development Corporation. In exchange for building a 200,000 square foot paper processing facility on Staten Island, Visy won itself a piece of the city paper stream. The facility opened in 1997, a year after Rudy Giuliani announced the impending closure of Fresh Kills. Since then, Visy has ramped up production, recyling 150,000 tons of city paper into corrugated boxes each year and paying $7 a ton for the privilege.

In other words, instead of the city having to pay companies to dump its trash – at a cost of at least $70 a ton – the city is being paid for the trash. Because of this, the arrangement with Visy translates into more than $11 million in savings for New York City taxpayers. On June 23, Visy and the mayor's office announced an ambitious 100,000 square foot expansion of the company's Staten Island facility to boost production even further.

A company called Hugo Neu has also forged ties with the city government. A major steel recycler, the New Jersey-based company offered to recycle the steel from the World Trade Center. It has since taken on a larger steel recycling contract with the city. Encouraged by the profitability of that enterprise, company executives made a play for New York City aluminum and plastic as well, offering to pay the city $5.10 per ton.

Considering that another company had put in a bid to charge the city $68 to get rid of that same material, Hugo Neu’s offer was one the Department of Sanitation could hardly refuse.

"This is not just an economic issue," said Hugo Neu general manager Robert Kelman at a May speech to the New York League of Conservation Voters. "This is a moral imperative."

What Next?

Moral imperatives aside, Hugo Neu's aggressive bidding has revived the image of recycling as a cost-effective enterprise. It has also prodded other local recyclers to seek their own portion of the city's mammoth recycling stream.

Carmen Cognetta, counsel to the council committee on sanitation and solid waste, hopes to speed the momentum.

"Recyclers used to be hesitant to deal with the city because they didn't get a good reception," Cognetta says. "I think once people see [the Hugo Neu bid] working, it will encourage more people to bid in the future."

One company eager to line up for city recyclables is Manhattan-based Sprint Recycling. Maite Quinn, the company’s managing director, says the market value for high quality paper runs well above the $7 per ton Visy currently pays for mixed paper and cardboard. If the city could find a way to segregate paper by type, it would boost profits even further.

"[New York] is not working as hard as other cities at getting the markets that do exist," she says. "We just put in a bid of $33 a ton for Jersey City's paper."

Another outcome of last year's roundtable has been a growing buzz over so-called "pay as you throw" funding systems. Under such a system, the city charges residents for trash pickup but not for recycling. In San Francisco "pay as you throw" has spurred the expansion of recycling streams in the realm of organic waste and kitchen compost. The city currently recycles half its waste, compared with New York City's 20 percent recycling rate in 2000-2001.

"'Pay as you throw' is a way to provide dedicated funding," says Robert Haley, recycling coordinator at San Francisco's Department of the Environment. "Come bad times or a budget crisis, you don't have to cut back recycling for lack of money."

Granted, San Francisco and New York are more than a continent apart when it comes to size, waste-stream burden and local markets for recyclable materials. Still, to get a hint of the future, New York reyclers can look to Canada's largest city, Toronto. Like New York, Toronto experienced the closure of its main landfill in the mid-1990s. Currently, the city exports about a fifth of its solid waste to Michigan. Through a combination of pay-as-you-throw and private contracts, the city is hoping to boost its recycling rate to 60 percent by 2006 and 100 percent by 2010.

"New York has challenges," says Lawson Oates, manager of Toronto's Solid Waste Management Division. "But it also has economies of scale that can be built in. That's an important factor."

Lawson, who also attended last November's roundtable, says he came away with a new respect for New York's waste stream. He recalls waking up at 3 a.m. to the sound of beeping sanitation trucks and workers clearing the enormous mound of garbage backs piled outside his hotel.

"I suddenly realized that nine floors wasn't as far up as I thought it was," Oates says.

Oates was equally surprised by the amount of manual labor that went into moving that waste stream. Oates says his own department has managed to boost productivity and rein in labor costs through wheeled bins in high density portions of the city. To stave off labor trouble, Oates' department has made sure to include union leaders in each step of the planning.

"With the four day work week, the union was wary but they eventually came on board," Oates says. "As a result, we've achieved economies and introduced some savings into our collection system."

Getting similar concessions out of the Department of Sanitation might be unlikely at the moment, but Oates' success has encouraged New York City planners to think creatively. Herein lies the final benefit of the recent waste management crisis: It has punctured the cultural hubris of a city used to viewing the outside world from a distance.

"For whatever reason, we have this mantra: We're New York. We're bigger than anybody. There's no other place we can learn from,'" Clarke says. "If you really think about it, half of New York is no different from any other large city. Only in Manhattan do you hit the problems most other cities never face."

Bloomberg: Savior or Shmendrik?

So how much credit should be given to Mayor Bloomberg, the man who, intentionally or unintentionally, forced the city's decades-old recycling program to prove recycling's economic sustainability?

For Resa Dimino, president of the Grass Roots Recycling Network and co-moderator of last November's roundtable, the answer is "not much." Dimino doesn't buy into the growing argument that the mayor's threat to suspend glass, plastic and even aluminum pickup in early 2002 was simply a case of managerial "tough love." Instead, she sees it as a costly example of brinksmanship in a city where residents have yet to experience the routine of a steady recycling program.

"I would argue that it would have been smarter to keep the program in place and go through the same kind of process," she says. "Instead, the city government just chose to ignore things until they reached crisis mode."

Others, such as McMahon, however, are willing to give the mayor the benefit of the doubt.

"I give the mayor credit in that he's the first mayor who admitted that recycling is a good idea for the environment and we can make it work financially," McMahon says. "Of course, we had to force feed him that a little bit. But in the final analysis he's doing the right thing by recycling."

Sam Williams is a NYC journalist.

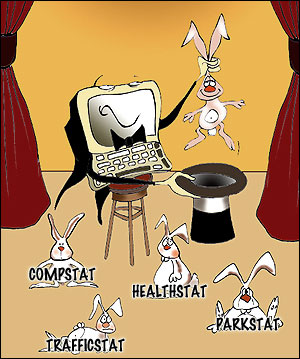

Compstatmania

When 57-year-old Alberta Spruill died after a botched police raid on her Harlem apartment in May, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly reacted immediately. Kelly apologized for her death, Bloomberg spoke at her funeral, both men promised an investigation. And, in a response that has become familiar in New York, the police department vowed to look at the numbers -- in this case to create a database with information on police raids conducted as the result of search warrants. The police department, like so many other city agencies and city governments, was hoping that another thorny problem could be solved by using yet another variation of Compstat.

When 57-year-old Alberta Spruill died after a botched police raid on her Harlem apartment in May, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly reacted immediately. Kelly apologized for her death, Bloomberg spoke at her funeral, both men promised an investigation. And, in a response that has become familiar in New York, the police department vowed to look at the numbers -- in this case to create a database with information on police raids conducted as the result of search warrants. The police department, like so many other city agencies and city governments, was hoping that another thorny problem could be solved by using yet another variation of Compstat.

In 1994, Police Commissioner William Bratton launched Compstat, a program that used hard data and stepped-up accountability to try to stem lawlessness in the city. It was, said George L. Kelling and William Sousa in a paper for the Manhattan Institute, "perhaps the single most important organizational/administrative innovation in policing during the latter half of the 20th century."

Officials in New York and elsewhere began copying it -- to fight crime but also to address many other problems as well. Soon, we had Healthstat and Parkstat and TrafficStat, and many more - with even more on the way.

Few seem to question whether there is a limit to the magic. But not everybody sees the trend as wholly positive. Indeed, some critics might go so far as to argue that Compstat actually played a part, albeit very indirectly, in Alberta Spruill's death.

THE BIRTH OF COMPSTAT

Collecting data and then mapping it has been used to identify trends and help find solutions since at least 1854, when a London doctor plotted the locations of more than 500 cholera deaths and saw that they clustered around one water pump. He had the handle of that water pump removed and ended the epidemic.

When William Bratton became police commissioner of New York City almost a century and a half later, he asked for a count of major crimes and where they occurred. A team of four police officers set to work transforming a rudimentary software program for small businesses into an elementary database with statistics about the seven crimes that municipalities must report to the Federal Bureau of Investigation -- murder, rape, robbery, felony assault, burglary, grand larceny and grand larceny auto. When the time came to save the file, one of the officers suggested naming it CompStat.

From this humble christening, something remarkable emerged. Police would enter crime reports into the computer system, which sorted them by type. Then officers pored over the weekly statistics to create maps and charts showing notable changes and emerging problem spots. Police department heads convened regular meetings to discuss the trends and strategies, inviting commanders from relevant precincts.

The sessions could be rough. As described by Craig Horowitz in New York magazine Jack Maple, the deputy police commissioner, "hammered every commander who came to a meeting unprepared. If robberies were up in the four-five that [commander] better have some suggestion to deal with it. Otherwise, he risked not only humiliation at the Compstat meeting but career derailment as well."

"In the Compstat meeting, people were accountable for getting the mission accomplished," said David Weisburd, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Maryland and the lead researcher on a Police Foundation study into the proliferation of Compstat. "The idea was, if you don't do the job, we are going to get rid of you, which was a radical idea. And if you do a good job, we are going to reward you." (The meetings are reportedly less contentious these days.)

But perhaps even more important than these meetings, write Kelling and Sousa, was the fact that Compstat spurred the development of local crime fighting strategies.

As Compstat evolved, crime fell sharply throughout the city, in all 76 precincts. The trend has continued. Overall, the serious crime rate (in pdf format) in 2002 was 65 percent lower than in 1993. For example, 2002 had 584 murders, compared to almost 2,000 in 1993.

Experts debate the true cause of that crime drop, pointing to the police department's pursuit of minor offenders during the Giuliani administration as well as demographic changes, the end of the crack epidemic and the strong economy. Some say that people in high crime neighborhoods, particularly young people, were angry at the violence and brought about the change themselves. Some critics note that other cities throughout the country also saw crime plummet in the 1990s - without Compstat.

Further, "the drop in crime [in New York] did not start in 1994," said Richard Holden (in pdf format), a professor of criminal justice at Central Missouri State University. Crime in the city peaked in 1990, Holden wrote, "and began its rapid decline from there. New York City was already in its fourth year of a dramatic downward trend in crime rates when it implemented its new approach."

"The data do not support a strong argument for Compstat causing, contributing to or accelerating the decline in homicides in New York City or elsewhere," criminologists John E. Eck and Edward R. McGuire have said.

But many officials and experts think, as Eli Silverman of John Jay College of Criminal Justice puts it, that Compstat "deserves some of the credit." The program received an Innovation in American Government Award, from Harvard's Kennedy School and the Ford Foundation, and officials in New York and beyond began looking for ways to apply it to other city scourges.

CHILDREN OF COMPSTAT

Over the past decade, especially in the past few years, city officials have implemented Compstat-like systems to address problems ranging from dangerous intersections to unruly inmates to negligent landlords.

First Compstat itself has evolved. "Compstat has changed over the years," said Detective Walter Burns, a spokesman for the New York City Police Department. "We've added different elements. The original concept was just dealing with precinct commanders. But one would come in and say, 'My problem is narcotics and I don't have a narcotics group. So bring narcotics into Compstat.' One says, 'I'm having a big problem with kids stealing cars.' Now auto theft is part of Compstat."

In New York, Trafficstat was among the first offshoots to take off. Also run by the police department, the program tracked accidents, arrests for driving while under the influence and other moving violations.

The Department of Correction implemented the Compstat model with T.E.A.M.S., its Total Efficiency Accountability Management System, and decreased overtime payments while increasing prison safety. The jails on Rikers Island became among the safest prison facilities in the nation, according to a report (in pdf format) about Compstat by the Rockefeller Foundation.

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation developed Parkstat. City parks were regularly rated for cleanliness and safety, and department supervisors were called upon monthly to account for their park's rating and discuss ways to solve problems. The percentage of parks rated acceptably clean and safe by the department rose from 47 percent in 1993 to 86 percent in 2001.

In August 2001, the Giuliani administration announced the Citywide Accountability Program which asked all city agencies to develop programs that implement the essential elements of Compstat. The agencies would collect data about their work and hold regular meetings with managers to find solutions to the problems revealed by the data. Currently, 20 city agencies participate in the program and publish data on the internet, where one can track all sorts of city statistics, from the numbers of complaints against taxi drivers to the number of malfunctioning off-track betting machines.

More "children of Compstat" appear every day. For example, the Mayor's Office of Health Insurance has been re-focusing Healthstat, a program designed to help uninsured New Yorkers enroll in publicly funded health insurance programs. In the first 18 months, participating agencies enrolled about 340,000 eligible New Yorkers. There are still 1.6 million uninsured New Yorkers, about 900,000 of whom are eligible for public insurance programs.

The Department of Education's new Office of School Safety and Planning will use elements of Compstat for SchoolSafe, a program that will identify schools with the highest crime rates and implement action plans.

And the Department of Transportation has M.O.V.E., a performance management and accountability system that meets twice each month to examine measurements of each operation's performance and to review its function and workflow.

And proposals for more Compstat type programs keep coming.

"We've done Compstat, let's do Jobstat," wrote Mike Wallace in his book 'A New Deal for New York.' Using the same kind of targeted analyses that helped reduce crime, he argues, we can help manufacturers stay in the city and nurture new kinds of industries.

Others think the Compstat approach can improve education in the city. "Changing the behaviors and attitudes of the school system toward parents and community won't be as easy," one-time mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer, now president of the Drum Major Institute, said. "That is why we proposed a Compstat-like mechanism for measuring the system's attempts to create meaningful relationships with parents and communities."

The Department of Homeless Services and the Vera Institute of Justice is gearing up for Homestat. The idea, says department spokesman Jim Anderson, is to examine the incidence of homelessness in various areas, as well as factors that may contribute to homelessness. The department hopes that a better understanding of factors contributing to homelessness will help it develop strategies to prevent homelessness, not simply try to house those already out on the streets.

The reaction to the death of Alberta Spruill provides more evidence of how much faith officials now put in tracking numbers. According to the New York Times, the Civilian Complaint Review Board had suggested as early as January that the police department track and store information on search warrants executed by police. Spruill's death apparently spurred the department to move to put the proposal into effect.

Some have even suggested a Compstat for city government as a whole. "Rather than casually assert that government is efficient, City Hall should create an Office of Continuing Reinvention to aggressively keep pursuing new streamlinings and efficiencies - a CompStat for all services," former Public Advocate Mark Green has suggested.

OTHER CITIES

Meanwhile, the idea has spread across the country. By 2000, a third of the country's 515 largest police departments had implemented a Compstat-like program, according to the Police Foundation study. Bratton, now chief of the Los Angeles police, has taken Compstat west with him, instituting it in America's second largest city last fall.

"That's an amazing diffusion of innovation," said David Weisburd, the lead investigator of the study. "I compared it to diffusion ranks of the fastest growing innovations, agricultural innovations and social innovations like birth control. Most innovations take a very long time to spread. This one, in comparison, was extremely fast."

The researchers at the Police Foundation believe that Compstat's popularity came from its top-down authority model. "Compstat emphasizes putting pressure on commanders," Weisburd said. "The drama occurs with the higher-ups."

Like their colleagues in New York, officials in other cities have created Compstats for other problems -- or a combination of problems. Baltimore, Maryland, has taken Mark Green's suggestion and implemented Citistat, which tracks city government as a whole. City agencies provide regular data about their work to a central office that analyzes the data and creates reports for the mayor.

"The charts, maps, and pictures tell a story of performance, and those managers are held accountable," said Matt Gallagher, director of operations for Citistat. Since the program was implemented, Baltimore has experienced a 40 percent reduction in payroll overtime, saving the city $15 million over two years, while taking on such indicators of urban blight as graffiti and abandoned vehicles.

Cities from Miami to Pittsburgh will soon implement similar programs.

The Compstat mania has gone so far that one proponent, Heather MacDonald of the Manhattan Institute has turned it into a verb. In a November 2001 Daily News column urging that Compstat techniques be used to track down terrorists, MacDonald wrote, "The FBI's anti-terrorism efforts should be Compstated in every city where the bureau operates."

NO MAGIC BULLET

Nobody has been heard suggesting that Compstat can root out members of Al Queda. But Eli Silverman, author of NYPD Battles Crime: Innovative Strategies in Policing says it makes sense for city officials to try to extend the Compstat model. "It''s not rocket science. It's fundamental management accounting," he says, adding, "if it's done right it can be very meaningful."

But he offers some caveats. When the system is introduced, it has to be explained to the organization. The basic information -- the numbers -- must be consistent. "The managers have to feel top management is serious about it," Silverman says, and management has to stick to it. The New York Police Department, he says, has done most of this. In particular, he says, the department "has been consistent about it. That's one of the secrets of its success."

Even Compstat's most ardent proponents concede that Compstat-style programs do have some downsides. "What is not counted tends to be discounted," wrote Dennis Smith and William Bratton in a Rockefeller Institute Report (in pdf format) that considered some of the unintended consequences of the New York City Police Department's Compstat.

Commanders tend to overlook other indicators of police performance, such as civilian complaints and patterns of police misconduct, including too-aggressive policing and a lack of respect for citizens. Critics say such an attention to the numbers helped create the aggressive police tactics of the late 1990s, leading to the killing by police of Amadou Diallo and frayed relations between the police department and many black and Hispanic communities. And, though relations have improved, some have suggested that the recent incident with Alberta Spruill is a continuation of the imbalance in police attitudes and values.

Sidney L. Harring, a professor of law at City University of New York Law School, and Gerda W. Ray of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, wrote in 1999, that as the police strove to increase arrests, they did not keep track of how many people they stopped and frisked on city streets. "That all of this scientifically structured, aggressive police work could be pulled off without even the most rudimentary data about its result reveals the hollow core of the social scientific foundation of New York City's highly managed policing. Compstat is no better than its flawed database," Harring and Ray said.

Indeed tracking systems are only as good as the numbers that guide them. Last month, police officials revealed that many felonies committed in the 10th precinct in Manhattan last year were improperly reported as misdemeanors, making the crime rate in the area appear lower than it really was. The department was investigating a former commander and a sergeant for downgrading crimes in the precinct, which includes Chelsea.

Police department spokesperson Michael O'Looney told the New York Times that the distortions were too small to have any impact on the Compstat statistics. But critics reportedly say that as crime has fallen, police commanders feel intensifying pressure to drive the numbers even lower. Since Compstat went into effect, "at least five police commanders have been accused of reclassifying crimes to improve their statistics, which are reviewed at sometimes contentious weekly Compstat meetings," William K. Rashbaum reported.

After Philadelphia began using Compstat, some police officials there also changed crime reports to make the areas under their command appear safer than they really were. "If a person was punched in the eye, it might have been written up as a hospital report, so it didn't reflect a crime had occurred," said Philadelphia police department Inspector Bill Colarulo, who said that checks and balances have since been put in place to avoid such fraud.