Greenway Glitches

Mayor Michael Bloomberg has made the creation of a Manhattan greenway a goal of his administration. Within two years of taking office, he completed an interim bicycle and pedestrian route around the entire island. He has supported putting into place the citywide 350-mile greenway plan, developed in 1993 by the Department of City Planning. But in Brooklyn, where the city is about to build one of the first sections of the trail envisioned along the downtown waterfront, the administration's current plans undermine the purpose of the greenway as a park space and a safe corridor for bicyclists and pedestrians.

All over the country, cities are creating landscaped bicycle and pedestrian paths (In PDF Format) for the many benefits they bring, including reducing traffic congestion, encouraging exercise, increasing real estate values and softening the hard edge of the city. So far, New York City has built about 100 miles of greenway, helped by the availability of federal transportation funding for this purpose.

Still to be built is the proposed Brooklyn Waterfront Trail in northwest Brooklyn, from the Brooklyn Bridge to Sunset Park. It would meet an existing path along Bay Ridge and could potentially connect with greenways along Jamaica Bay.

The first section of the trail slated to be built goes through the Columbia Street district, a mixed residential and industrial neighborhood wedged between the piers and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Cut off from the rest of Brooklyn by the highway and connected to the working waterfront, it has the feel of a village and views of the Manhattan skyline. In a neighborhood only a few blocks wide, residents created four community gardens, which are now official city parks, and have been trying for a decade to get the city to put in the greenway through their neighborhood.

The city is finally putting a pedestrian/bicycle path through the area as part of a long-planned road reconstruction to better accommodate truck traffic to the piers. But the current design would leave the greenway with a hole in one section, where it eliminates the green - and the off-street path for bicyclists - in favor of widening the road.

For several blocks along Van Brunt Street, the city Department of Transportation plans to narrow an existing wide sidewalk and route bicyclists onto striped bike lanes on both sides of the street. To rejoin the greenway going north, riders would have to cross the street just before a blind turn that is being redesigned to allow trucks to pass at higher speeds.

Hundreds of residents have signed a petition to Bloomberg asking him to intervene in the impending reconstruction project and establish an interim greenway on the existing harbor-side sidewalk.

Residents believe that the greenway is being downgraded in favor of widening the road because adjoining neighborhoods, which are more populous and politically powerful, want to divert traffic from their streets. They note that the Columbia Street area already has 14 lanes of moving traffic. The Department of Transportation did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Community Board 6, which stretches from the Red Hook and Columbia Street waterfront to Park Slope, approved the road reconstruction project. According to Craig Hammerman, the district manager, the roadwork was originally proposed 15 years ago to reduce the impact on the neighborhood of trucks going off the approved routes. "If we design the truck route properly, then we won't need to rely on enforcement down the line," he said. The project has since taken on two other elements - infrastructure work for the Third Water Tunnel and incorporating the Brooklyn Waterfront Trail. In the negotiations over the project, the

Department of Transportation agreed to turn over for a park a 100-foot site originally intended to divert trucks. "We believe the agency has gone as far as we can get them to go," Hammerman said.

Bicycle advocates credit the Department of Transportation with becoming more bicycle friendly in recent years. The agency has added 200 miles of bike lanes as well as bicycle crossings on all four East River bridges, one factor contributing to doubling of the number of people riding bicycles in the city over the past 20 years. But they say it has been less receptive to off-street greenways or even physically separated lanes, giving first priority to moving vehicular traffic through the city.

One example is on First and Second Avenues in Manhattan, where there are high volumes of traffic. The city chose not to put in a physically separated bike lane, "letting people fend for themselves in traffic," said Noah Budnick, projects director at the advocacy group Transportation Alternatives. "In the Columbia Street area where you have a community that very much supports building the off-street path, it's harder to understand why the city and the Department of Transportation don't want to choose the safe alternative," he said.

Dave Lutz, a neighborhood resident and member of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway Taskforce, an advocacy group, said that Van Brunt Street isn't the only place the city is putting a greenway along the road where there is space for it to go through a landscaped corridor. Lutz, who is also the director of the Neighborhood Open Space Coalition and one of the creators of the city's greenway plan, said, "As we paint those stripes on our streets and put greenway signs on those streets, we water down the term of what a greenway is. A greenway is a separate trail for pedestrians and bicyclists buffered by greenery."

The Overall Path

Because the land along the Brooklyn waterfront is controlled by so many different entities - including city agencies, the Port Authority, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and numerous private companies - piecing together a greenway promises to be a complicated and politically charged process.

The goal of greenway advocates is a 30-foot-wide, 14-mile-long landscaped off-street path along the waterfront. Such a trail would provide greenery and recreation for many neighborhoods that have very little public open space, as well as access to the borough's far-flung beaches and parks and its diverse neighborhoods. "It is as much a park space that you move through as a transportation corridor," said Robert Pirani, director of Environmental Programs at the Regional Plan Association, an independent planning group for the tri-state area.

Several local organizations are beginning to create an overall framework for the trail, which ultimately would be implemented by various city and state agencies and private landowners. The office of Borough President Marty Markowitz was instrumental in getting grants for the work through the New York State Waterfront Revitalization Program.

One of these organizations is the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative, Inc., led by two former members of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway Taskforce who split off from that group to take a more active role in planning and advocating for the overall path. Milton Puryear, director of planning for the initiative, said they believed that the way to "get around the DOT's refusal on Van Brunt Street and the quality we are after was to really communicate the whole vision and engage a much bigger population than the couple thousand people who live along the BQE."

Together with the Regional Plan Association, the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative has begun a six-month process of developing a route in Community Boards 2 and 6, from Red Hook to Newtown Creek in Greenpoint. The first public meeting was held in November. The planners will return with a conceptual plan at another public workshop on February 1.

In Community Board 7 in Sunset Park, the community-based organization UPROSE has trained neighborhood youths to lead a grassroots participation process to design a greenway through the largely Latino, Asian, and Arabic neighborhood. UPROSE helped block the construction of a power plant along the waterfront and is involved in a number of efforts to reduce pollution and increase greening in the neighborhood. The neighborhood has 35,000 young people, yet just a quarter-acre of parkland per thousand residents and almost no public access to the waterfront.

As the Brooklyn waterfront changes, there are many competing visions for how it should evolve. These range from preserving the working waterfront and encouraging water-borne transportation to current city proposals for housing, parks, and a cruise ship terminal. The city recently approved a zoning change in Red Hook to allow a controversial Ikea store to be built, and other big box stores may follow. These changes could provide opportunities for the creation of a green pathway, as well as obstacles.

Many of the projects proposed or in the works for the Brooklyn waterfront have the potential to increase automobile traffic unless there is an effort to develop alternatives. "Communities all across the country are trying to get automobile traffic off the waterfront so that the amenity value can benefit the community," said Pirani. "What is Brooklyn's waterfront edge going to be like? Is it going to be designed more for moving cars and trucks around the waterfront, or as more of a space for pedestrians and bicyclists and people being comfortable walking around it?"

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Saving Two Birds; Saving Staten Island

A little over a year ago, "Jurassic Park" author Michael Crichton delivered a speech to San Francisco's Commonwealth Club on the similarity between environmentalism and religion.

"Environmentalism seems to be the religion of choice for urban atheists," said Crichton. "There's an initial Eden, a paradise, a state of grace and unity with nature, there's a fall from grace into a state of pollution as a result of eating from the tree of knowledge, and as a result of our actions, there's a judgment day coming for us all. We are all energy sinners, doomed to die, unless we seek salvation, which is called sustainability."

His words replayed in my mind during the media coverage of New York's two most famous raptors – the red-tailed hawks Pale Male and Lola, after their unceremonious eviction from a 12th floor perch at 927 Fifth Avenue.

Biologists often lump predatory birds into the category known as "charismatic macrofauna" -- animal organisms big enough to impress or awe human observers. In their decade of residence alongside Central Park, Pale Male, Lola and their offspring have been the inspiration for a documentary movie, multiple television specials and magazine articles, not to mention a book, "Red-Tails in Love."

That may explain why the removal of their nest inspired a week’s worth of rallies, with nearly a hundred people gathered across the street chanting “ No nest, no peace.”

"Whatever Lola wants, Lola gets," read one sign.

"Honk-4-Hawks," read another.

"People want to see the nest brought back," E. J. Adams of the New York City Audubon Society politely explained to the press.

The co-op board reversed itself; Pale Male and Lola will return – demonstrating the benefits of ...not a religion... but what could be called emotional environmentalism. Before we elevate them to sacred status, however, it's important to realize that not all species have the benefit of a Manhattan address, celebrity neighbors, and a noble visage. Many, like the endangered Torrey's Mountain Mint and the American chestnut tree, do their living and dying invisibly in overlooked spaces such as Charleston Woods on Staten Island.

Saving Staten Island

The history of Staten Island and the history of Staten Island real estate development are often one and the same. Since the days of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the Staten Island economy has been built on one fundamental precept: Inside every cramped city apartment is a future Staten Island homeowner yearning to breathe free.

Forty years after the construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, however, many local groups are starting to question the wisdom of that notion. A hot real estate market coupled with a loophole-riddled building code have led to hasty, ill-conceived developments on an island already known for its crazy-quilt approach to neighborhood planning. But resistance has been piecemeal as well: "There's so many things going on on Staten Island that everybody is so busy taking care of their own little piece of turf," says Dennis Conwell, a Dongan Hills activist.

Lately, however, island environmental groups have been finding places to dig in. For the last 12 weeks, Kryscherville, a neighborhood just north of the Outerbridge Crossing, has been the scene of candlelight vigils as local environmental groups protest the potential construction of the island's third Home Depot store on 130 acres of city-owned woodland known as Charleston Woods. Event co-organizer David Burg of WildMetro says the protest was the only recourse after a failed legal attempt to block the sale to the Blumenfeld Development Group, a Syosset-based company that a 1999 New York Public Interest Research Group report ranked as the top-spending lobbyist in New York City.

Burg admits that turnout for the Sunday vigils has been slight -- most attract fewer than 12 participants -- and the media coverage negligible. Still, in giving activists a place to gather and vent their feelings, the group has managed to turn a local defeat into a victory of sorts. On November 17, delegates from 15 island groups convened for an island-wide "summit" on open space issues. Attendees pledged mutual support on everything from low-level single-lot disputes to large-scale projects such as the recently proposed Nascar racetrack in the wetlands region just below the Goethals Bridge. To sum up the "join or die" spirit of the gathering, delegates ambitiously titled their alliance the Coalition to Save Staten Island.

"The feeling is that there's just too much for existing groups to take on individually," Burg says. "It's now or never."

Most official remedies to the threat of overdevelopment involved changing “the width of streets or the number of curbs,” said Shirlee Marraccini, a resident of Great Kills and president of Turnaround Friends, a non-profit dedicated to converting abandoned or underutilized properties into community parkland. Such remedies do little to prevent the subdivision of existing city-owned or privately-owned lots currently regarded by most Staten Islanders as open space.

If recent behavior is any indication, island politicians are already sensing a shift in community sentiment, and responding accordingly; area representatives, for example, oppose development of the Charleston Woods site.

"Before we use the Charleston site for stores, we should put it to public use," writes Councilmember Andrew Lanza on Gotham Gazette. "The infrastructure of Staten Island has lagged behind development. We have overcrowded schools, we do not have enough parkland, and we do not have a single recreational ballfield on the South Shore."

For Conwell of Dongan Hills, political support is crucial but not as crucial as a coalition. Development is a many-headed opponent, he believes; without cross-island coordination, each local victory is outweighed by multiple losses.

"It's so hard to see information in the city," Conwell said. "Between tracking the auctions, trying to keep track of what the building is department doing, what the [Department of Environmental Protection] is doing, you also have to throw in the dimension of what our friends in Albany and Washington D.C. are doing. Everybody's got a little slice of responsibility, which adds to the confusion. Most of the time I've just seen things by watching the Internet."

Burg says even the limited pressure over the Home Depot development has scored results. Earlier this month, he says, attorneys from the Blumenfeld Development Group contacted WildMetro to set up a discussion on how to mitigate the project's environmental impact. Representatives from the company did not return calls requesting comment, but the company has a similar Home Depot/Costco project in East Harlem facing even more community pressure. The group is also talking with the city about preserving a 30-acre remainder of the Staten Island site as open woodland space.

While not exactly victories, such talks have done much to slow the fait accompli nature of local developmental politics. When coalition members gather in January, Marraccini hopes the group can come up with a few more places worthy of collective action.

"I sincerely believe that the Kryscher Hill-Charleston Wood project was the beginning of something," she says. "With all the natural areas going away, we really need to have one united voice. Hopefully, we will have some impact not just on one project but on all of them." The result won't restore us to Eden, but the members of the coalition hope that Staten Island, at least, will be saved.

Â

Using Energy More Efficiently In NYC

This is a good time for City Hall, and the city as a whole, to focus on using energy more efficiently.

There are many reasons to do so. For one, energy costs have been skyrocketing, and promise to rise even more steeply. The price of oil is already way up, and Con Edison is trying to get a rate increase of 6.7 percent.

Pollution also looms as a large threat. This summer, New York City joined eight states in announcing a lawsuit against five major polluters, whom they charge with contributing to global warming. These companies alone -- American Electric Power Company; the Southern Company; Tennessee Valley Authority; Xcel Energy Inc.; and Cinergy Corporation -- are responsible for ten percent of the nation's total carbon dioxide emissions.

"There is no dispute that global warming is upon us and that these defendants' carbon dioxide pollution is a major contributor," says Attorney General Eliot Spitzer.

At the same time, the demand for energy is increasing. In recent years, the number of electrical appliances in homes and offices (especially computers) has increased significantly. In August 2003, the high demand for energy led to a major blackout. While New York’s energy systems are some of the most modern, the state’s reserve of energy is 40 percent lower than regulators say it should be. That is one reason why power companies are proposing the construction of up to 15 more power plants in New York City.

Thus, reducing energy use would save money, prevent blackouts, reduce the need to build new power plants, and could also improve local air quality.

And one way to reduce energy use is to increase energy efficiency. There are some computers – and air conditioners and lights and household appliances and industrial motors – that run more efficiently than others. Most newer computers have software that can automatically save power when the computer has not been used for a certain amount of time. Experts also advocate for greater use of such cleaner and more efficient energy sources as solar power and wind power, as well as fuel cells. Frank Morris of the Sierra Club believes that better management of the demand for energy could reduce the city’s energy use by 35 percent.

Currently, there is a bill pending in the New York City Council that would create a new energy policy office. The law would require the city to develop a comprehensive energy policy, assess the efficiency of energy use in city facilities, set goals for the reduction of energy use, encourage energy conservation and the use of fossil fuel alternatives by both the public and private sector, and promote public awareness of the efficient use of energy.

One could reasonably question how effective this office would be, however, in light of the difficulties over another bill being considered by the City Council, which encourages City Hall to get its own house in order.

The bill focuses specifically on the use of city-owned computers. The city owns some 100,000 personal computers and office equipment, which could be made more efficient – and save some $1.4 million on energy costs – through the use of power-saving software.

But the city agency in charge of the computers, the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DoITT), opposes the legislation.

Why?

The city’s vast information technology infrastructure “makes the implementation of the proposed initiative difficult to deploy and enforce,” testified Ron Bergmann, a deputy commissioner at DoITT. “Agencies largely administer their own computer operations and have a diverse array of equipment, operating systems and applications.”

Laura Forlano is a doctoral student studying communication technology policy at Columbia University.Â

Leaving The Hudson River Out Of The Hudson Yard Plans

Ask anyone who has jogged, biked, skated or strolled along the Hudson River lately what their least favorite stretch is and you might be surprised at the response. It is not in the Meat Market area, where lamb and cow carcasses get unceremoniously dumped into refuse bins early each afternoon. It is not Gansevoort peninsula, where dozens of garbage trucks idle and queue at the beginning and end of their route. It is not the West 130s in Harlem where the North River Sewage Treatment Plant sits on the shore. No, the smelliest, most offensive stretch of the Hudson River Greenway is in Chelsea, right beside what is being called the Hudson Yards.

At West 30th Street sits the heliport. Helicopters – like most fossil fuel burning engines – do not run at peak efficiency at lower speeds. While landing or idling on the waterfront tarmac the smell of hot, unburnt fuel is overwhelming. The hundreds of takeoffs and landings here each day may seem to constitute a dense arrival and departure pattern for tourists and high rolling commuters, but the stifling reality is that the air quality along this stretch of the Hudson River Greenway is possibly the most unhealthy and certainly the most offensive one can find the length of the waterfront along the entire Manhattan shoreline of the Hudson.

Slightly more than four blocks north is Pier 76, home to the city’s tow pound.

This stretch of the Hudson River, then, is home to two unfortunate waterfront uses, neither of which makes use of the water in any way.

Sadder still, the city and the state do not have any plans to change this. At the same time that both city and state are pulling out all the stops to redevelop the West Side, attract the 2012 Olympics, and expand the convention center, it is unfathomable to think that more than a billion dollars in public money is to be spent to redevelop 11 blocks along the Hudson River with no real plan to improve the waterfront.

The greatest sea-change in urban living in New York City in the last 30 years is the transformation of urban waterfronts and waterways into exciting new public spaces. From the Gowanus Canal to the Bronx River, these once-derided waterways are now synonymous with grassroots success. And there is no revival to rival the rescue of the Hudson River along the west side of Manhattan, where the collapse of the Miller Highwayover thirty years ago opened the door for the removal of the detritus of commerce, parked and towed cars, crumbling pier sheds, and miles of chain link fence separating the hundreds of thousands of workers and residents in the adjacent communities from the most famous river in the United States.

But this is not happening in the area alongside what is being called, ironically, the Hudson Yards. The only thing the city is doing for the Hudson River in its plans for the Hudson Yards is stealing the river’s name. This stretch of Hudson River waterfront will not be the beneficiary of either the city’s investment of $600 million in the Hudson Yards, nor the state’s plan to expand the Javits Center. In fact, these two plans together in their present state will simply perpetuate the non-planning that has plagued so much of the city’s waterfront development in the last thirty years.

The neglect of the Hudson River in the Hudson Yards plan is the most short-sighted aspect of what is being promoted as a visionary, long-range plan. The city’s own map for the Hudson Yards area makes clear that the study deliberately left out the waterfront. As the Environmental Impact Statement for the project makes clear, the western terminus of the project area is not the river, but 12th Avenue. Despite the fact that images used to promote the Sports and Convention Center illustrate glorious river views and an active waterfront dotted with sailboats, ferries, and water taxis, the plan for the stadium itself includes merely building an elevated walkway over the West Side Highway to connect to Hudson River Park.

If this is visionary planning then I would rather take the proposed $600 million in city funding for the Hudson Yards and trade it in. For this awesome amount of money, one could complete Hudson River Park ($225 million), Brooklyn Bridge Park ($150 million), Sunset Park Waterfront Park ($25 million), Harlem River Park ($50 million) the South Bronx Greenway ($50 million) combined. With the extra $100 million we could create a few hundred street-end parks around the city in any of the places where few such large-scale waterfront opportunities still exist. The beneficiaries of all these investments may not be season ticket holders, of course, but we all must remember that the beauty of this city is not that not everyone can afford a skybox – it is that most of us don't want to be in one.

Carter Craft, an urban planner, is director of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.

Saving Oakland Lake

Jerry Iannece is a good example of the kind of person who can get things moving in New York City.

"I know how it works," says Iannece, a former district attorney who now serves as chairman of Queens Community Board 11. "The squeaky wheel gets the grease.”

Or, in this case, thanks to squeaky Iannece, Oakland Lake didn’t get the grease.

Iannece lives in Bayside Hills, a neighborhood near Oakland Lake, a spring-fed body of water that dates back to the last Ice Age; the parks department says it is the only one in Queens. Once teeming with wild fish and birds, it now serves mainly as an aesthetic backdrop for local joggers and a cement-lined way station for Canadian geese. Yosemite it's not, but in a corner of New York City dominated by the Cross Island Expressway and Northern Boulevard, it's a sentimental reminder of the days when canoes, not SUVs, were the primary mode of transportation in this corner of the city.

The problem facing the neighborhood was how to avoid the flooding to which the area was prone without emptying the runoff into Oakland Lake, which would then be contaminated with the toxic mixture of flood water, motor oil, fertilizer and other pollutants.

Engineers said the city would have to build a mile-long diversionary sewer pipeline, which would empty into the Little Neck Bay instead. Federal clean water regulations, meanwhile, demanded a new stormwater treatment facility. The price tag for the whole project would be as much as $160 million.

"Some people said that with that kind of money we should have just bought the dozen or so houses," says Iannece. "But if we did that, we'd be destroying a community. My response was, the city allowed this problem to happen. The city can fix it."

Elected president of the Bayside Hills Civic Association in 1996, Iannece at first used his newfound authority to press the Department of Environmental Protection to put its diversionary plan in motion. He also used it to lobby local residents on Springfield Boulevard and 46th Avenue, the two streets that would have to be torn up to make room for the new sewer pipeline. Most importantly, says Iannece, he courted prominent local politicians such as former Queens Borough President Claire Schulman and State Senator Frank Padavan, people with the power to move bureaucratic mountains with a single phone call.

"Jerry was extremely helpful," says Padavan. "In addition to reaching out to the community at large and getting me involved, he helped us overcome hurdles that would have kept the project from going through."

Among the chief hurdles was the Alley Pond Environmental Center, a bird and plant sanctuary located near the original sewer's untreated outfall. If the city had gone with its original plan, it would have dumped water into an area currently home to meadows and salt marshes. "Ecologically, it would have been a disaster," says Dr. Aline Euler, education director for the Alley Pond Environmental Center.

To keep waterborne pollutants from overwhelming the sensitive Alley Pond and Alley Creek ecosystems, city engineers agreed to move the sewer pipeline to the west, running it under Northern Boulevard.

As part of the compromise plan, the Department of Environmental Protection has also agreed to build storage tanks to capture water in low flow periods so that pumps can redirect that water to the Tallmans Island wastewater treatment plant for processing.

Meanwhile, both Euler and Iannece are looking to the project's final hurdle: the environmental remediation of Oakland Ravine, a portion of the Oakland Lake park which, thanks to the construction of 56th Avenue to the south, has been largely cut off from its historical watershed. A year ago, the Department of Environmental Protection appeared to waver on plans for a $10 million filtration system to handle the fast moving water coming down off the Queensborough College campus. Padavan brokered a meeting between Iannece and department officials. Both sides agreed to a more modest plan proposed by the parks department. The new plan uses parkland vegetation and "step pools" to filter out whatever contaminants work their way into the groundwater before that water hits the lake.

Euler, for one, is skeptical. "They really need to do a major job from an ecological standpoint, a sensitive design that takes into consideration trying to restore that lake to the way it was,” she says. “That lake was 15,000 years old and was working fine when the native Americans lived there. It was fine with the colonists. I hope that they do spend some money to improve it and restore it to the way it was."

Noting a century's worth of urban development, however, Iannece doesn't see that sort of remedy in the cards. He does, however, see the potential for something similar to the Staten Island Bluebelt, where park rangers have been able to bring back a semblance of native wetland amid an otherwise urban environment. Recent rumors that the Oakland Ravine portion of the project might fall out of the budget again have steeled his resolve to see it restored to a semblance of its native form.

"I think I might have to start kicking some butt again," he says.

While he doesn't consider himself an environmentalist, Iannece says he does think environmentalists and civic groups can work together to find more sustainable solutions to the man-made problems currently dogging the city. Advising other neighborhood groups on how to fix their own local problems, he keeps the advice simple: Start small, stay focused, and set yourself at least a five to ten year timetable for change.

"It's kind of like a war of attrition," he says. "I've been in rooms where 300 people would get up and yell at me. Still, if the community's focused, if the rhetoric is good, if the message is good, if the plan is good, you'll get the job done."

Planting Trees For Life

Hunts Point in the Bronx has an alarming number of children hospitalized for asthma -- the second highest rate in the city. It also has one of the lowest number of trees of any neighborhood in the city -- until recently, just one street tree per acre. Neighborhood activists saw a connection between the two statistics, looked at all the sources of pollution in the area – the 10,000 trucks that travel it daily, for one -- and formed a group called Greening for Breathing. Their goal is to plant a canopy of trees.

Hunts Point is just one of the neighborhoods with low-income, minority populations that have more pollution, more health problems, and fewer trees than the city as a whole. The average amount of land covered by trees in New York City is about 18 percent. In Hunts Point, canopy cover is 3.5 percent.

Trees lessen pollution by absorbing gases and intercepting particulates (the soot on the windowsill). By cooling the ground and filtering sunlight, they reduce the formation of ground-level ozone. In 2000, New York City’s street trees removed 1,500 metric tons of air pollution, according to an estimate by David J. Nowak, a scientist at the U.S.D.A Forest Service’s Northeastern Research Station. Studies (in pdf format) by Nowak and others have determined some of the variables that affect how much pollution a tree will remove, including its size, species, and location. For example, large trees remove about 70 times more pollution annually than smaller ones. An analysis by the Forest Service and SUNY’s School of Environmental Research of a survey done in 2003 found that just 322 trees in three New York City neighborhoods annually removed more than 500 pounds of pollutants from the air.

Street trees have many other benefits. They reduce energy use by shading sidewalks, buildings, and cars in summer, and buffering winds in the winter. They absorb greenhouse gases, slow stormwater runoff, and provide habitat for wildlife. Houses on leafy streets have higher real estate values, and trees in front of stores encourage pedestrian shopping. Research has shown that street trees create hospitable spaces — outdoor rooms — that bring neighbors together, resulting in stronger communities and lower crime.

Together with the city parks department, the group in Hunts Point came up with a detailed strategy (in pdf format) to survey existing trees, identify the best locations for new ones, plant them, and help them survive to maturity. They have planted 400 trees so far, and plan to plant an additional 75 a year for the next five years. "Eventually we’re going to have what I call an awning around us,” said Eva Sanjurjo, who has lived or worked in Hunts Point most of her life and was one of the founders of Greening for Breathing. “The awning is the trees."

Stitching together that awning is a slow process that requires a tremendous amount of legwork. The city will plant a tree on a sidewalk only if the owner of the adjacent property requests it, so volunteers have to find property owners and persuade them to submit a request. Because the parks department lacks the funding to care for trees once they are planted, a key part of the effort has been to recruit volunteers within the community to water, weed, and keep garbage from piling up around the newly planted trees, especially in the first few years when a tree is most vulnerable. To prevent vandalism and encourage stewardship, the plan includes special tree-planting days, workshops, and celebrations. "You can’t just plant trees and then you’re done — that’s the easiest way to fail," said Elena Conte, the group's coordinator. "What we’re working for is a much richer involvement."

As part of its current focus on the relationship between trees and public health, the parks department would like to replicate the Hunts Point project in ten communities around the city, and is working with the Department of Health to identify the locations, according to Fiona Watt, Chief of Foresty and Horticulture at the parks department. "Our focus and interest right now is how do we target our tree preservation, maintenance and planting programs to best support this emerging relationship and to improve public health in the areas that need it most."

A QUESTION OF FUNDING

The tree-planting efforts in Hunts Point as well in several other tree-poor areas around the city have been funded in part by the state, which has increased its support for urban forestry in recent years. Previously, the only money available for state urban forestry programs came from the federal government. In 2000, for the first time, New York began appropriating state funds for urban forestry, through the Environmental Protection Fund. Governor George Pataki singled out urban forestry as a priority in his State of the State address last January. Funds have also come from two separate settlements negotiated by New York State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, in which bus companies charged with illegal idling were required to spend a total of $147,000 for tree-planting in areas with high asthma rates and near public schools.

But state funding for urban forestry, totaling $450,000 over the last four years, still falls far short of what is needed, according to Nancy Wolf, executive director of the New York State Urban and Community Forestry Council: A survey of municipalities around the state, recently completed by the council but not yet published, showed "the need for tree-planting money is just colossal."

In New York City, the parks department receives less than half a percent of the city budget to maintain and run the parks, so very little money is available for street tree care. In 1997, the department instituted a regular block-by-block tree pruning program that reaches the city’s 500,000 trees once every ten to twelve years, but park advocates fight annually just to keep the money for pruning in the city budget. Ideally, trees should be pruned every seven years, if not sooner. Maintaining and protecting trees in other ways, like watering, monitoring for disease, and purchasing tree guards to fend off trucks and cars, is left to tree-loving citizens and non-profit groups like TreesNY.

The capital budget, which covers planting trees, has been more robust, although not nearly enough to substantially increase the city's overall street tree population. Funding has ranged from $7 million to $10 million a year for tree planting, except during last year’s budget shortfall, according to Watt. But the price of planting a tree has risen steeply, so the department is able to plant fewer trees for the same amount of money.

In many years, the department planted slightly more trees than it lost, although last year it planted 9,997 trees while it removed 11,412, according to the recently released Mayor’s Management Report.

In September, the City Council passed a resolution calling on the city, state, and federal governments to plant trees in "communities of color, communities of low income and communities with the highest asthma rates, that have historically had the fewest tree plantings." But it doesn't address the funding needed to achieve that goal.

"The city should start by spending $45 million, one-tenth of one percent of the city budget," said former parks commissioner Henry Stern. "That would give you a much stronger program than you have now."

Efforts like Greening Hunts Point offer the hope of making life better and healthier in the city’s communities of color. But to bring trees into all the neighborhoods that need them most will take more than City Council resolutions and pilot projects. Urban forestry would have to become a citywide priority, with sufficient funding, for the city to truly green its grayest blocks.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

The Mayor's New Garbage Plan

|

Also: Related in Community Gazettes:

|

Unlike most New Yorkers, Carl Van Putten and Lilian Garcia pay attention to garbage after it is thrown away. They have little choice: their neighborhood, Hunts Point, is home to many of the city's "waste transfer stations" - sheds where garbage trucks dump trash so that larger trucks can pick it up and carry it out of state.

"The minute I came to Hunts Point my son developed chronic asthma," said Garcia.

On any given morning, as many as ten garbage trucks stand idling within a block of Van Putten's home on Hunts Point Avenue, where the breeze sends the smell directly towards him.

"I don't have polite words for it," he said. "You can call it a fragrance, aroma, or odor, but it's still a stink. It's heavy."

That is why they were happy to learn of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's solid waste management plan (pdf format), which would move most of the 50,000 tons of trash the city produces each day by rail or barge, instead of by truck. [For more about the plan's effect on the South Bronx, read Dumping Ground No Longer?in the Community Gazettes for the South Bronx].

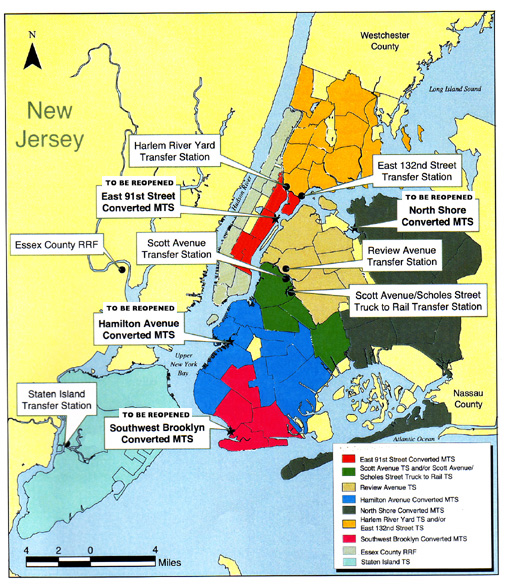

To do this, Bloomberg proposes to reopen four city-owned marine transfer stations, piers where trucks can dump trash onto barges, to handle the city's residential waste. The proposal is the third in a waste management plan that the mayor has rolled out over the last month:

- Recycling - The city signed a 20 year contract with Hugo Neu, a recycling company that will build a recyling station on the Brooklyn side of the East River.

- Commercial - A transfer station on 59th Street on Manhattan's West Side, is to be reopened to handle the city's commercial waste.

- Residential - Four transfer stations are to be reopened for residential garbage, one on Manhattan's Upper East Side, one in College Point, Queens, and two in Brooklyn (one in Red Hook and one in Gravesend).

The stations that the mayor wants to reopen were closed when the city stopped using Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island in 2001. Whether these stations handle commercial waste or residential waste doesn't matter much to those people who live near the stations; some don't see why the burden should now be placed on them.

"I know that the garbage has to go someplace," said Sandy Whitlock, who lives near the transfer station on the Upper East Side. "But it shouldn't have to impact a residential community." [For more, read The Garbage Returns to the Upper East Side in the Community Gazette].

Aside from complaints on the neighborhood level, some say the plan doesn't do enough to address the citywide trash problem. The prices the city pays to move its trash have risen substantially since Fresh Kills closed. Some out-of-state landfills that the city uses are nearing capacity, and the states where these landfills are located are often not much more interested in receiving the city's trash than are residents of the South Bronx.

Despite this, what the mayor describes as his comprehensive waste management policy stops at city limits, a shortcoming that experts like Benjamin Miller, former director of policy planning for the Department of Sanitation and author of the book Fat of the Land: Garbage in New York the Last 200 Years, see as its major flaw. [Read Miller's analysis, "The Waste Management Plan: Approve It, But Improve It"].

"The most important thing is where this stuff goes," Miller said, "and there's been no talk of that."

BURYING IT, BURNING IT, DUMPING IT

The challenge of dealing with garbage is not a new one to New York City. The city has long searched for an effective way to manage its waste - piling it onto islands, carting it to far-off lands, selling it to entrepreneurs, feeding it to hogs, burning it, or simply dumping it into the sea. Trash has been used as the foundation for airports, parks, and beaches. People trying to keep it from being shipped to their communities have proposed legislation and gotten into fistfights at City Hall to further their cases.

Many ambitious plans to manage the city's waste have not become anything more than words on paper. One supposedly temporary one, though, ended up turning into the largest manmade object on the planet.

When Fresh Kills landfill opened in 1947, it was slated to close within three years. Instead, it became the center of a citywide system that lasted until 2001. Sanitation Department trucks that collected residential waste and privately owned trucks that collected commercial waste would travel to one of eight marine transfer stations, where they would be emptied onto barges headed for Fresh Kills.

In the mid-1980s, the city raised the price of using these piers, and private companies built their own smaller truck transfer stations in places like the South Bronx and Northern Brooklyn. Trucks carting commercial waste transferred garbage to others headed out of state at dozens of these facilities. The city's residential waste, meanwhile, continued to go by barge to Fresh Kills.

In 1996, however, Mayor Giuliani pleased the Staten Islanders who made up an essential part of his political base by announcing that he would close down Fresh Kills. Consequently, the city-run marine transfer stations essential for the barge system were closed.

But by ending the Fresh Kills era without planning for the next, Giuliani left the city's own trucks with nowhere to go.

AFTER FRESH KILLS

The Sanitation Department began sending its trucks to the private transfer stations, where the trash they carried was dumped - or "tipped" - and reloaded, sometimes onto a train but usually onto a truck, and shipped out of state.

Private companies built these facilities based on their own business decisions, and the burden fell disproportionately on several neighborhoods. In a recent report (in pdf format), Environmental Defense, a national environmental group, found that 80 percent of the waste handled by private waste transfer stations goes to four of the city's 59 community board districts. "You have right now these stations located in neighborhoods where probably the land value was lower and the zoning was different. When [private companies] looked to set up those stations, [they] looked for those things," said Ramon Cruz of Environmental Defense. "Is that fair? No, but it's a function of the market."

The hundreds of trucks moving through these neighborhoods every day were not just smelly. Their weight took its toll on the roads, and their exhaust polluted the air. Asthma rates skyrocketed in areas where the stations were concentrated, a health effect linked directly to the garbage truck traffic.

Nor was this system particularly healthy for the city's economy. Shipping trash to landfills in Virginia or Pennsylvania was much more expensive than floating it to Staten Island. The per-ton contract for shipping garbage rose from $54 in 1997 to its present price of $74, a 40 percent increase over seven years. (If increased gas and labor prices are factored in, the increase is even larger.) The Department of Sanitation budget ballooned. Private companies saw their prices rise 50 percent over the same period.

Additionally, other states have resisted the city's garbage by imposing surcharges on out-of-state waste, and have passed laws to limit importation of trash. Federal legislation with the same goal has been introduced several times; there is currently legislation pending in both the House of Representatives and Senate.

To date, these laws have been overturned or rejected because they violate interstate commerce regulations, but they indicate the city's continuing vulnerability to events that are out of its control.

These problems are not secrets. But largely because any change in garbage policy alienates one political constituency or another, the city has faltered without a plan for years.

THE MAYOR'S PLAN

Over the last several weeks, Mayor Bloomberg has announced several proposals that, he says, add up to a comprehensive plan for dealing with garbage. The common element of his three plans is to shift from using trucks towards using barges and rail to move garbage out of the city.

To do this, the mayor intends to reopen four of the marine transfer stations that were closed along with Fresh Kills to haul the city's residential waste. Another station will handle the city's commercial waste.

The city's recycling will also be shipped via barge. The city will reopen a station at Gansevoort Street in Manhattan's meatpacking district, from which the recyclables will sail to a facility being constructed by scrap-metal company Hugo Neu in Brooklyn. The city also hopes to increase the proportion of its waste that gets recycled, to 25 percent of residential garbage by 2007 and then to 70 percent of both residential and commercial garbage by 2015.

The mayor has calculated that his plan to reopen the marine transfer stations for residential garbage will reduce truck traffic in the city by almost three million miles a year. This will have an obvious benefit for the city's roads; it will also reduce gas and labor costs and ease the environmental burden of waste management.

The city can count on its own trucks bringing residential waste where it would like. It cannot, however, simply force private companies to do the same with commercial waste. The Economic Development Corporation and the mayor's office are in the beginning stages of developing a system of incentives and regulations that will make its transfer station more attractive, while also raising the costs of running private transfer stations.

|

|

Clashing Communities

If the city can significantly reduce the use of private transfer stations, the negative effects of moving trash out of the city will be spread much more evenly, and the overall impact on the environment will be reduced. Community organizations and environmental groups that have long been calling for such changes are reacting positively to the idea.

Rare is the garbage plan that does not create resistance from those areas that will receive a larger burden, however, and this plan is no exception. Residents and local officials from the Upper East Side, represented by the mayor's chief political rival, Council Speaker Gifford Miller, object to the reopening of a station in their neighborhood. They say that the station's proximity to such a dense residential neighborhood is reason to keep it closed.

Miller makes a familiar argument: what is unhealthy in one neighborhood shouldn't be allowed in another. The Bronx and Brooklyn have used the same argument in their calls for Manhattan to handle it own trash; Staten Island periodically threatened to secede for decades, its residents' aspiration to become a separate city inspired largely by the feeling that the rest of New York was dumping its trash on their borough.

Bloomberg is unconvinced that the Upper East Side will suffer unfairly. "Every single part of this city has to participate in solving a very difficult problem," he said in response to Miller's objection, adding that the East Side produces a fair amount of residential trash and the facility already exists. "Nobody wants to have solid waste near them, but somebody's going to have to ... [Y]ou are limited to where you can site facilities."

While the mayor insists that politics did not fit into his decision to open this particular station, he does seem to have set up a political confrontation that could work to his advantage - hardly a rare move for politicians dealing with New York City's garbage.

An Expensive Plan With Dubious Economic Benefits

Bloomberg estimates that opening the marine transfer stations will cost $340 million, $85 million each. The total investment is actually larger, since the price of revamping the station for commercial waste or the operating expenses of these facilities are not included in this figure. (The recycling plant, on the other hand, is being built by Hugo Neu at no cost to the city; the contract by which it will handle the city's recycling is estimated to save $20 million annually).

The proponents of the plan are not promising a miraculous reduction in cost, though.

"It's not going to get cheaper; let's not kid ourselves," Sanitation Commissioner John Doherty said at the press conference where the details of the plan were announced. "What [this plan] is going to do is stabilize the costs."

But critics question whether it will even do that. A few large companies already run the waste management industry. According to the city Comptroller's office, 91 percent of the trash headed for landfills is controlled by one of three companies. Since a limited number of facilities can accept trash from barge or rail, the city may be making itself even more vulnerable to an uncompetitive market by relying solely on these two forms of transportation.

This problem underscores what critics say is a major weakness in the city's new plan: a failure to figure out where the garbage will go after it is shipped out of the city.

WHERE OUR GARBAGE GOES

The plan in its current form carefully itemizes how trash from each borough will leave the city. But the most distant destination it mentions is the Essex County Resource Recovery Facility, an incinerator in Newark New Jersey that converts a good portion of Manhattan's waste into energy. Newark is about 12 miles from midtown. But almost half of the 15 million tons of waste the city generates each year is sent to landfills in either Virginia or Pennsylvania, with some trucks driving as much as 1,300 miles roundtrip.

These trips are expensive, and are bound to get more so as gas prices rise, the landfills in other states fill up, and states continue to look for ways to keep New York City garbage out.

The effort of other states "is not slamming the door completely, but it's making the doors smaller, and it's making the price higher," said Benjamin Miller. "That's going to keep happening forever, and the only way to solve that problem … [is] to have a landfill in New York State."

The city comptroller's office agrees. In a report published this month (in pdf format), it advocated an in-state landfill. Although communities often don't want landfills, dumps do bring economic benefit, the report argued, and it makes sense to have that economic benefit go to New York State. In addition, a landfill in New York State that the city itself controlls would shield it from the anti-importation regulations in other states, and might even curb the enthusiasm to pass such laws.

For their part, the mayor's office and the Sanitation Department say that they sent a query (in pdf format) to upstate communities earlier this year asking them to consider a landfill for New York City waste and received no responses. Critics say the lack of interest is a result of a request so vague that it was impossible to take seriously.

WILL THE LATEST PLAN BE IMPLEMENTED?

Even under the best of conditions - if the City Council approves the plan, and the revamping of the now-closed stations goes according to schedule, and the commercial carters agree to use the city's facilities instead of their own - the new system will not be in place until 2007.

But plans dealing with garbage in New York City rarely enjoy the best of conditions. Big ideas tend to emerge, meet public resistance, fade away, and then sometimes re-emerge years or even decades later. Mayor Bloomberg himself announced a plan to reopen all eight marine transfer stations two years ago that quickly disappeared; Mayor Giuliani's comprehensive plan for garbage similarly vanished. Burning garbage used to be commonplace, but after spending a good deal of the 1990s planning for an incinerator at the Brooklyn Navy Yards, city officials now consider such facilities unspeakably bad ideas.

One big reason for this inability to latch onto a permanent solution, some say, is the public attitude. New Yorkers do not want to take responsibility for their own garbage. This helps explain, anthropologist Robin Nagle has pointed out, why sanitation workers might as well be invisible. They know more about any city neighborhood "than the most sophisticated sociologist just by observing what it discards," Nagle wrote in a recent online diary about her experiences working alongside NYC sanitation workers, "but no one [cares] about their insights. In fact, no one [cares] much about them at all."

The Waste Management Plan: Approve It, But Improve It

|

Also: Related in Community Gazettes:

|

The administration's new waste-management plan represents an important step in the right direction. It deserves to be approved. But it also deserves to be improved in a number of strategic ways that will make it truly cost-effective in the long run. Getting control of the facilities where our waste will ultimately be disposed of is the most critical of these strategic objectives.

THE PRIVATE SECTOR

Since the Fresh Kills landfill closed in 2001, New York, for the first time in its history, has depended on facilities in other states for the disposal of most of the 50,000 tons of solid waste it produces every day. The quarter of this material that the city's Sanitation Department collects is handed off to a highly organized private waste-disposal industry, in which a handful of firms own most of the country's available landfill capacity.

The per-ton fee charged by these not-so-benevolent oligopolists has increased, since the city started shipping garbage out of town in 1997, from $54 to $75 per ton—40 percent in seven years--while the fees paid by private businesses have increased by 50 percent. This steady climb, which affects not just New Yorkers but all our neighbors on the eastern seaboard who share access to the same landfills we use, is projected to continue in the decades ahead. To keep up with increase in cost, the city would have to lay off 300 or so full-time municipal workers every year.

OTHER STATES

If the sellers' market we blindly walked into with the unplanned closure of Fresh Kills were not enough, the severely tried patience of government officials in other states—New York State exports more refuse to place in landfills out-of-state than it puts in those within its own capacious boundaries—will further decrease our options. In 2002, Pennsylvania (which accepts roughly half of our waste) imposed a $4 per ton tax on all waste entering its landfills; in 2004 Governor Edward Rendell proposed increasing that tax by another $5 per ton.

After the announcement of Fresh Kills' impending closure, Virginia passed a law forbidding the import of out-of-state waste. That law was promptly struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court, as all such prior attempts had been, as a violation of the constitution's interstate commerce clause. But the failure of local initiatives does not preclude the eventual passage of some federal measure to limit the interstate shipment of waste, something that Congress in the last decades has seriously considered doing.

Moreover, there are perfectly legal means of excluding other states' waste—all that is required is having the public sector assume control over landfills, as Rhode Island and Delaware have done, or promulgating regulations that restrict the development of new landfill capacity, as South Carolina has. While it is not likely that New York's access to out-of-state landfills will be completely closed in the foreseeable future, it is inevitable that over time the export window will be narrowed. And equally inevitably, this will mean that disposal prices will increase even further.

NEW YORK'S OWN LANDFILL

The only viable long-term solution to this problem—as a compelling report (in pdf format) issued last week by City Comptroller Bill Thompson makes clear—is to develop or procure public waste disposal capacity, preferably in New York State, but wherever it is available on a cost-effective basis and easily accessible by the barges or railcars that impose much lower environmental and economic costs than trucks do.

And while some of this must be landfills (since there will always be some waste that cannot be managed in any other way), we also should use waste-to-energy facilities, which produce fewer adverse environmental impacts do landfills and are more cost-effective. (This is why the portion of the administration's recently released plan (in pdf format) that involves a long-term government-to-government contract for continued access to the Newark incinerator that already processes much of Manhattan's waste is a particularly good idea.)

OTHER ISSUES

While we are developing or procuring this publicly controlled waste-disposal capacity, there are other immediate steps we should be taking to reduce the volume of waste we must export and the cost of transporting it to its remote disposal locations.

One of these steps, as the comptroller's report makes clear, is using the city's contracting leverage to directly procure transportation services from the railroads. This is critically important for two reasons. First, if it does not do it, the city will inevitably pay much more—including a significant commission to the waste-industry middleman—than it would pay by negotiating a per-ton-mile transportation-services contract itself. Secondly, the logistical difficulties involved with contracting with the railroads represent a barrier that would exclude many smaller landfill operators, whose bids are essential if we are to enjoy a semblance of free-market competition.

The other thing we should do immediately is develop fair economic incentives for reducing the volume of waste that New Yorkers generate. (We should not try to reduce our waste volumes by using in-sink garbage disposals, either for residences or businesses, since this only increases public-sector costs and adverse environmental impacts.)

The single most effective way to do reduce garbage, as the experience of thousands of U.S. cities demonstrates, is by “metering” waste. Rather than having their waste-management costs buried within the city's general tax structure, New Yorkers would get an upfront deduction on their property-tax bills and would instead pay for having their waste removed by buying special bags or tags or paying on some other volume-based basis. Conscientious householders would thus save money relative to their current hidden tax payments and would no longer have to subsidize the wasteful habits of their neighbors.

Benjamin Miller, author of Fat of the Land: Garbage in New York, the Last Two Hundred Years (Four Walls Eight Windows, 2000), is a senior fellow at the CUNY Institute for Urban Systems.

The New Garbage Plan; New Worries About Flooding

New Garbage Plan

The major effect of the city's latest Solid Waste Management Plan, announced at a press conference this month by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Department of Sanitation Commissioner John Doherty, is to cut down on truck traffic through the city.

The city seeks to "retool" at least half of the eight "marine transfer stations" that have been largely idle since the closing of Fresh Kills landfill. Trucks have been shipping the garbage to out-of-state landfills since then. Now, sea-going vessels (and railroad cars) will do the shipping. Bloomberg estimated the elimination of at least 625 truck trips daily. "This would result in close to three million fewer truck miles on city streets."

Of course, this is not exactly comprehensive; the mayor's office has yet to find a way to reduce the city's mammoth residential trash load, currently averaging 12,000 tons a day. But the plan would at least reduce fuel consumption and truck-borne exhaust, two environmentally deleterious side-effects of the current trash-exporting system.

For more on this, see The Mayor's New Garbage Plan.

The Flood Next Time

Last month's torrential rains have once again reminded New Yorkers that while hurricanes generally do the bulk of their damage in places like Florida and North Carolina, they can still wreak plenty of havoc this far north. Remnants of Hurricane Ivan managed to shut down a dozen subway lines when flooding tunnels in Brooklyn and Manhattan imperiled the electrified third rail. On Sept. 28, remnants of Hurricane Jeanne disrupted service in a similar fashion out in Queens.

Such flooding leads to the natural question: What would it be like if New York City bore the brunt of the hurricane as opposed to the tail end?

Don't laugh. Two hurricanes hit the city in the 19th century and flooding from the lone 20th Century hurricane, the so-called Great Storm of 1938, killed more than 200 people on Long Island and parts of New England. According to Queens College geology professor Nicholas Coch, an expert on historical weather patterns, the city averages one major tropical cyclone a century.

"In the south they get a lot of hurricanes so it's easy to predict," says Coch. "Up here it's less predictable, so the more historical data we can gather, the better idea we have."

While the region may not have as many storms as Florida or North Carolina, those that do make it this far north pack a punch. Coch says the two hurricanes that hit the city in the 19th century most likely would have qualified as category two storms in terms of wind speed (96 to 110 miles per hour) but delivered broad regional damage equivalent to a category three storm.

"[Northern lattitude hurricanes] tend to have a larger wind field, move faster, and create very high surges."

Coch says the angled New York-New Jersey coastline tends to funnel storm energy onto local beaches and harbors. In the case of the city, the Verrazano Narrows acts like a meteorological megaphone, amplifying whatever storm waves make it through. In the 1821 hurricane, water level readings at the Battery showed a 13 foot rise in a single hour. "That was at low tide," Coch notes. "If the storm had hit during high tide, things would have been a lot worse."

New Yorkers who face down a hurricane in the 21st century might not be so lucky, even at low tide. Vivien Gornitz, a Columbia research scientist, studies sea level rise. Currently, she sees local waterways rising at a rate of 2.5 millimeters per year, 50 percent higher than the worldwide average. She expects that rate to accelerate in the coming decades as global warming draws more water out of mountain glaciers and polar pack ice and transfers it to the world's oceans.

"Whatever surge you'd see [in a future hurricane] would be superimposed on a higher sea level," says Gornitz. "With various levels of sea level rise, what we now consider 100 year storms could occur more often."

Put another way, the kind of local flooding that residents and insurance companies could pass off as a once-in-a-lifetime event may soon become a once-a-decade occurrence. Worst case models show a 10 foot rise in sea level, enough to cover the streets of Coney Island, Midland Beach, and Chinatown, hitting with a frequency of once every 5.5 years by 2080, assuming no change in coastal defenses.

Admittedly, 2080 is a long way off. Barring a major hurricane, Gornitz says the effects of climate change will look a lot like last month: Small storms will pack a bigger punch, resulting in more commuter and homeowner hassles and, over the long haul, readjusted flood insurance premiums, zoning and building-code changes designed to limit New Yorkers' flood exposure.

"I don't think it's going to be a sudden calamity," says Gornitz. "It's just going to magnify what we're already seeing."

Clearing the Air

With all of our focus on the war in Iraq, the upcoming elections, and the administration's ever-vacillating orange and yellow terror alerts, we New Yorkers may not be putting a mundane topic such as pollution very high on our list of worries. But while the problem may not grab our attention like a war, persistent environmental hazards in places like the Bronx are taking the lives of our children just the same.

Policymakers have the power to address these problems, but often seem to lack the will to. In Congress, we need to maintain tough standards and fund research to find technological solutions to environmental problems, while also tackling systemic issues such as access to health care.

HEALTH PROBLEMS IN THE SOUTH BRONX

The numbers are disturbing: New Yorkers suffer from the worst rates of asthma in the country, with over 10 percent of schoolchildren and more than 6 percent of the total population affected by the chronic respiratory disease. New York, along with Chicago, leads the nation in asthma deaths. Conditions are especially bad in the South Bronx, where 20 to 25 percent of schoolchildren suffer from asthma. Children in the area are hospitalized for asthma at a rate 250 percent higher than the rate for children in the rest of New York City, and 1000 percent higher than the rate for children in New York State as a whole.

South Bronx residents also cope with abnormally high rates of other respiratory illnesses, infant mortality, and immune deficiency disorders, while living in unhealthy conditions and having poorer access to healthcare.

Several local factors contribute to the pollution behind the respiratory illness epidemic. The South Bronx, besides being surrounded by highly trafficked highways, is home to a disproportionate share of the city's waste transfer stations. It is also a center of industrial activity. As a result, diesel trucks are omnipresent, creating dangerous levels of air pollution. The pollution from these trucks has been specifically linked to severe asthma attacks.

In low-income communities, health problems can quickly turn into social ones: Asthma, for example, is the number one cause of student absenteeism in New York City schools.

FUNDING RESEARCH AND GREEN SPACE

Since 1998, New York University, with cooperation from the local community, has conducted the South Bronx Environmental Health and Policy Study. The study, which I secured funding for, analyzes the environmental and public health effects associated with living near pollution sources, including waste transfer stations and major expressways.

So far, the study has observed the following:

• Hourly concentrations of diesel exhaust are higher at all of the South Bronx sites that have been tested than at the sites tested in Manhattan.

• Street level air sampling, using the study's mobile van laboratory, reveals that the concentrations of nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide are substantially higher than samples taken from rooftop monitoring sites. Air pollution is often more severe closer to the ground, and so it is important that it be studied where people actually are (on the ground), rather than just on rooftops, where it has traditionally been measured.

• Levels of most pollutants in the South Bronx are below U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards, with the exceptions of ozone and particulate matter.

• There is a strong association between zip codes with high asthma rates and those with a high number of industrial facilities, such as the waste transfer stations that are found all across the South Bronx.

The study is still underway. Its findings will help local policymakers better understand the relationship between air pollution and public health in the South Bronx. A series of papers written during the study are available at http://www.house.gov/serrano. Future research will examine demographic variables such as property values, poverty, and median household income to see what kinds of people are more likely to live close to dangerous waste transfer stations.

Students have already helped to disseminate the findings of the air pollution study to community leaders and residents and will continue to do so. These young people are participants in a program for high-school students from the South Bronx that gives them a chance to work with scientists and policy experts in public health and environmental science and to explore career opportunities in these areas.

TAKING ACTION

The findings of the South Bronx Environmental Health and Policy Study underscores how poor people bear a disproportionate share of the burden of our city's air-borne disease. Much needs to be done to address this injustice.

The first step is to enforce the clean air regulations that we already have in place. Unfortunately, the Bush administration has been working to systematically relax the tough standards of the Clean Air Act. While Democrats and some moderate Republicans have tried to challenge the administration in Congress, the Republican leadership of the House and Senate has refused to allow for the tough oversight that our citizens so desperately want and need.

GREENER PLACES, CLEANER TECHNOLOGY

In the most urban of American cities, our children must have access to open spaces where they can play and enjoy nature. But while parks make children's lives healthier and more fun, we should also pursue technological solutions to environmental challenges. Through policy initiatives, government can encourage the private sector to explore these possibilities. Using alternative, cleaner-burning fuels can go a long way in reducing the air pollution that afflicts our communities.

Alternative fuel technology development can also help to create jobs as innovative, more environmentally friendly companies provide economic growth and cleaner products. One of the great myths of our day holds that environmental protection and economic growth are incongruous. The Center for Sustainable Energy at Bronx Community College, which I helped fund, works to dispel that myth, showing the connection between growth and protection through education, training, and community engagement.

Congress needs to do more to combat the devastating effects of air pollution on the health of Americans. To that end, I have sponsored legislation to provide tax credits to businesses that use clean-fuel vehicles in high pollution areas. I have also co-sponsored the "Clean Smokestacks Act of 2003" that would amend the Clean Air Act to require the reduction of emissions from electric power plants. Unfortunately, the Republican Congressional leadership has not allowed these bills to advance through the House.

BETTER ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE

These are the sorts of measures we need to help reduce the environmental problems in places like the South Bronx. But from Boise to Brooklyn, asthma and other respiratory diseases would not be so damaging if we had universal health care in our country. Disadvantaged Americans are paying for our nation's disparities with their health and their lives. If asthmatics received proper preventative health care, they would be able to better manage their asthma and get access to the medication they so desperately need. Government needs to do more to expand access to health care and to encourage people to use the services already available.

As it stands now, many of our kids only get their asthma treated when it becomes so bad that they have to go to the emergency room. Studies have consistently shown that the amount we pay for emergency room visits costs more than it would to provide better preventive care. For these reasons, as well as in the interests of basic social justice, we must continue to fight to build an America that is not the only industrialized nation in the world without universal health coverage.

The challenges ahead of us are myriad and daunting. But if we truly believe in an America of equal opportunity, we must work to reduce the glaring environmental and health disparities that continue to afflict our needy communities.

José E. Serrano, a Democrat, represents the 16th Congressional District. He serves on the House Appropriations Committee and is a member of the Children's Environmental Health Caucus.

Â

Recycling Food Waste

New York City recycling has rallied in the last two years. Glass and plastic are back. Paper never left. Even local sewage, once decontaminated, is finding a productive use as organic fertilizer -- albeit with lingering odor and safety issues .

The next obvious target is food waste. New York leads the nation in wasting food. Up to 40 percent of the city's garbage every day are old bones and bologna sandwiches. One reason is the vast number of restaurants here - almost 18,000. But even the percentage of residential waste that are old food scraps is higher here than the national average (almost 13 percent here compared to 10 percent nationally). Residents of other cities stick their food waste in their backyard, creating nutrient-rich composting; too much of New York doesn't have such backyards. Food scraps that would be ground down kitchen sinks in Los Angeles or San Francisco end up at the curbside in Brooklyn or Manhattan.

Attempting to recycle more organic waste - food scraps and yard material -- would fit in with what is reportedly a new tilt in the city's waste management strategy. The New York City Department of Sanitation is scheduled this fall to present to the New York City Council its latest Comprehensive Solid Waste Management Plan, outlining what should be done over the next 20 years to handle the city's garbage. There are some clues that the city is looking to lessen its dumping bill by recycling more waste.

This fall the Department of Sanitation will resume passive yard waste collection at three facilities: Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island, Spring Creek in Brooklyn and Soundview in the Bronx. In the case of food waste, however, the only current recycling options for most residents and businesses are the local community garden programs that offer limited scale composting.

Barriers to expanding such voluntary programs are sizable. Christine Datz-Romero is a co-founder of the Lower East Side Ecology Center, a neighborhood program that currently recycles more than 60 tons a year of food waste. The program sells 10 tons of compost a year to local garden supply shops. The center hopes to expand -- it is currently exploring a plan to provide curbside pickup for the area encompassing the entire local community board - but Datz-Romero says that it won't be easy, given the need for permits, funding, and so forth. "If you started the process today, you would open the door on your facility in between three and four years -- if you're lucky."