Recycling's Next Chapter

The Department of Sanitation has resumed both glass recycling and once-a-week collection of residential recyclable material, thus ending the latest, and most harrowing, chapter in New York City's 20 year-old recycling saga.

Once a week, residents are now expected to put their non-paper recyclables -- metal, plastic, and glass -- in blue curbside containers, and their paper recyclables -- junk mail, bundled newspaper and cardboard -- in green containers. Residents who don't have blue or green containers can use clear plastic bags or can order stickers, free, by calling 311 or visiting the city's Web site.

That glass is now being recycled once again is, some say, little more than a symbolic victory. Sure, it is an improvement over simply sending empty bottles to the landfill. But the Department of Sanitation trucks currently collect all different kinds of glass together, regardless of color, and this reduces the resale value often to the point of worthlessness.

This explains why Hugo Neu Schnitzer East, the Jersey City recycler that offered to pay the city for its metal and plastic last year, has drastically revised its bid. The city now pays Hugo Neu $51 per ton to process all non-paper recyclables. This is still about 50 percent less than what it would cost to dump the material in a landfill, but, coupled with the added labor costs for weekly routes, recycling has decisively shifted to an expense rather than a revenue source.

However, not everybody sees the victory as just symbolic. Some say it is a strategic victory, helping build the momentum for recycling.

"I am a firm believer that the more that we recycle the better it is not only for the environment but also for the city's economy," argues Staten Island councilmember Michael McMahon, chairman of the council's Solid Waste Committee.

Such arguments have gained added weight in recent weeks thanks to the Independent Budget Office's recent report analyzing the Department of Sanitation's budgetary math. Yes, the report concludes, recycling costs more than ordinary garbage collection, $47 million more in fiscal year 2002, but only as long as the amount of recyclables collected remains less than the amount of ordinary garbage collected.

The reason: hidden overhead costs. When department budgetmakers divide general and administrative costs, they do so by routes, not tonnage. Because recycling routes yield less weight on average -- 6.3 tons vs. 10.3 tons for ordinary garbage routes in 2002 -- recycling carries a disproportionate share of overhead burden when the numbers are reassessed on a cost-per-ton basis.

"It's the relative inefficiency of (recycling) collection that makes it more expensive," summarizes Preston Niblack of the Independent Budget Office. "Right now the comparison is swamped by the collection inefficiencies associated with recycling pickup."

In other words, says Niblack, shifting glass from the waste bin to the recycling bin is more than a symbolic gesture. Increase the amount of recyclables and you increase the average weight, and overall efficiency, of each recycling route. If the weight of recyclables became equal to the weight of ordinary garbage, you could conceivably eliminate the disparity in costs.

Kitchen Compost?

Given this analysis, is there another quick way to increase recycling tonnages beyond glass? McMahon sees kitchen compost as an obvious next step. "It adds a lot of weight, and it's environmentally the easiest thing to recycle," he says.Virali Gokaldas, policy director for the Natural Resources Defense Council, agrees, noting that, because of space concerns, New Yorkers tend to throw out more food waste as a proportion of their daily trash -- 15 percent, while the national average is nine percent

"Food is one of the greatest untapped opportunities for cost savings," Gokaldas says "Composting is the next step if the city wants to save money on its trash bill."

So far, the Department of Sanitation's attempts to integrate kitchen waste into the recycling stream have yet to move past the pilot project stage. Without a robust aftermarket or a Hugo Neu-style benefactor willing to take bagged items directly out of the trucks, compost remains a long term prospect at best.

"At this point we are not looking to add other recyclables," says Kathy Dawkins, a Department of Sanitation spokesperson.

Education

Niblack sees education as the best way to bulk up city recycling bins. Though long chided by local critics, the Department of Sanitation's Bureau of Waste Prevention, Reuse and Recycling had been earning praise for its educational programs prior to the 2002 plastic and glass suspension. To prepare residents for the resumption of glass and once-a-week service, the bureau orchestrated a series of Sunday newspaper inserts and a direct mail campaign aimed at four million households. All in all, it expects to spend close to $4 million within the next few months.

"That's a pretty good starting point, but the jury's still out," says McMahon. "I'd like to see more public service commercials. I'd like to see more advertising, especially in less traditional media, Web sites."

Robert Lange, president of the Bureau of Waste Prevention, Reuse and Reycling, didn't respond to calls for comment, but Dawkins said the Department of Sanitation is "committed to making recycling work" and has spread its $4 million advertising budget across a variety of media, including radio and television, as well as direct telemarketing.

McMahon, meanwhile, says he would like proof that Mayor Michael Bloomberg himself is a member the "strategic victory" camp as well. In a joint statement with Sanitation Commissioner John Doherty last month, Bloomberg described the current recycling program as both more "cost effective and environmentally-friendly" than the one it has now replaced.

"I call upon the mayor to continue using his bully pulpit to call for recycling like he does for 311," says McMahon, citing the increasing popularity of the city's telephone information program. "We have to get the message out: Eight million people can't just landfill this stuff anymore."

For links to sites concerned with Garbage in New York, check out Gotham Gazette Suggests.

Getting Federal Money To Improve The Port Of New York

Every year major legislation is passed in Washington that has a significant impact on many things in New York City, including the waterfront. If forces in the city as well as Albany worked more closely together this impact could be dramatically more positive than it is now.

The U.S. House recently voted to approve the Transportation Equity Act, a law that sets funding levels for virtually all transportation projects throughout the country for the next six years. Given that the average household spends 19 percent of its income on transportation, more than on any other expense except housing, one would think this critical legislation would be a rallying point for the New York delegation as it once was. In fact, the law would not exist in its present form were it not for the vision and leadership of the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan who authored the original bill in 1991. That year, what had long been known as the "Highway Bill" was reconceived and rewritten to encompass all modes of transportation - in addition to cars and trucks -- bicycles, boats, trains, and traffic calming devices such as speed bumps were incorporated into our federal funding formulas for how we spend gas tax revenues.

Since that time, critical funding has come to the city for such diverse projects as the Long Island Railroad East Side Access, the Second Ave subway, the citywide Bicycle Network, Soundview Park Greenway, and a slew of new ferry terminals all under construction including St. George, Whitehall Street, and Pier 79 on Manhattan's west side.

In Washington, the House's version of the Transportation Bill will now have to be resolved with the Senate's version ($318 Billion) and the President's ($247 billion) before the current deadline expires April 30 (it's already been extended twice). The president came in with the lowest number because it was felt that, given the current economic climate, nothing more would be affordable without an increase in the gas tax--a non-starter in an election year. Of course, the Texas Transportation Institute's 2003 Urban Mobility Study shows that congestion in the nation's 75 largest urban areas has increased again this year, as it has in every area every year since 1982. While today's papers decry "expensive" gas, in relative terms it is as cheap as it has been in three decades, and all it is giving us is more traffic congestion.

While the focus of many people is on land-side transportation, the reality is that with global trade at all-time high levels, the land transit is only half of the picture. The nation's seaports currently handle 95 percent of our international trade, and virtually every one of them has access problems on both the waterside and landside.

With 1.3 billion tons of cargo valued at $764 billion moving through U.S. ports each year, our infrastructure is ever-strained to meet the growing demands of international trade. The Port of New York and New Jersey handles nearly 12 percent of this amount, meaning that one of every eight dollars in port commerce nationwide passes in and out of New York Harbor, mostly underneath the Verrazano Narrows Bridge.

The federal policy to improve the port is largely influenced by the Water Resources Development Act. While traditionally the domain of dredgers, shippers, and people in flood prone areas, this legislation is increasingly incorporating environmental components such as watershed planning and environmental restoration projects, and that's a good thing.

In the current budget year, for instance, $103 million in federal dollars are being spent to deepen the Port of New York and New Jersey's shipping channels. These investments are needed, advocates say, to accommodate the larger and larger ships which are bringing goods to the larger and larger retail stores popping up throughout the country. At the same time, the US Army Corps of Engineers is spending approximately $1 million to advance an environmental project known as the "Hudson-Raritan" restoration; the current phase of work brings federal money to help clean-up the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn and the Passaic River in New Jersey-two of our areas most abused water bodies. This is a prime example of how the New York and New Jersey delegations can and should work together more closely.

Looking ahead, what's needed are federal policies that embrace the waterways in terms of mobility, recreation, and environmental restoration. When legislative and funding opportunities arise such as the Transportation and Water Resources Bills, we must have leadership in our Congressional delegation so our city and port can not just remain competitive, but set a higher standard for the other major cities and ports around the country with whom we increasingly find ourselves competing.

Carter Craft, an urban planner, is program director of the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance.

How To Make An Excellent City Park System

For years, New York City park supporters have been calling on the city to provide an adequate baseline of funding for parks and recreation. Indeed, having sufficient resources – in staffing, land, and equipment - is one of the key factors contributing to an excellent urban park system, according a recent study by the Trust for Public Land. New York spends far less on parks than the cities with the best systems in the country. But the report, The Excellent City Park System, looks beyond funding to identify other measures that make a city park system great.

"If you don’t have other factors like good planning, community involvement, and good access, then throwing money at it won’t solve all of the challenges," said the study’s author, Peter Harnik, who directs the trust’s Green Cities Program. The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, which has developed a number of innovative programs in recent years, can benefit from the research in this report as it works to improve the city’s vast network of parks, playgrounds, fields, forests, and recreation facilities.

The Excellent City Park System is based on two days of discussions by 25 experts on urban and park issues, followed by surveys and phone interviews with park directors all over the country. The seven measures of excellence it discusses include:

- a clear mission

- an ongoing planning and community involvement process

- sufficient assets to meet the system’s goals

- user satisfaction

- safety from physical hazards and crime

- and equitable access for all residents no matter where they live, how much money they have, or whether they have physical disabilities.

The seventh measure -- "in many respects the most important one," said Harnik -- is having benefits for the city beyond the boundaries of the park.

Excellent Practices

The report also highlights numerous "excellent practices" from cities all over the country. One of the examples cited is the New York City Parks Inspection Program, which conducts 4,000 park visits a year focusing especially on the safety of grounds and equipment.

Squeezing More Greenery Amidst The Concrete

City park departments are limited by factors beyond their control, like the location of existing parkland. For example, it would be difficult for New York, with little vacant land and high-priced real estate, to have a park within six blocks of nearly every resident, as Denver does. The report mentions New York City’s planting of more than 2,000 concrete traffic triangles and medians under the Greenstreets program as a way to squeeze more greenery into a built-out landscape. Nevertheless, with some areas totally devoid of usable parks, New York could learn from Chicago, which has greatly increased green and open space through a collaborative effort of the city’s planning department, public schools, and two park agencies. The project, called the CitySpace Plan, studied community park needs and every parcel of existing private and public open space. It also worked with other government agencies and numerous civic and business organizations to understand and make use of the economic and regulatory processes that encourage the creation of parkland, as well as to change regulations or laws that discourage it.

A Master Plan

One thing that many of the country’s best park systems have in common is a frequently updated master plan developed with substantive community involvement. An ideal plan, according to the report, would inventory resources, identify needs and goals, and set strategies, timelines, and budgets to implement those goals. Although New York City does not have such a plan, the Department of Parks and Recreation has recognized the need to do more long-term, in-depth planning, according to Deputy Commissioner Liam Kavanagh. The department is in the midst of developing a 10-year capital plan that is looking not only at spending on specific park infrastructure but also at longer-term needs as the city’s population and its use of parks changes.

Citizen Advisory Board

Another hallmark of excellent parks that New York City lacks is a citizen advisory board. Instead, said Kavanagh, the parks department’s advisory mechanism is the 59 community boards. "We agree with the spirit of that recommendation," he said, "but I don’t know if a formal citizen advisory board would work so well in New York. New York is really a collection of neighborhoods, and people feel attached to their neighborhood, more so than their borough or even the city as a whole."

Harnik disagreed. "Each community board is only interested in its own community," he said. "It’s hard for any citizen to have a big picture of the New York City park system if it is not constituted as a citizen advisory board to the park system as a whole."

Community Involvement

Over the last couple of decades, community involvement in New York City parks has taken root and grown like a weed. Almost half the parks in the city have affiliated groups, and 12,000 New Yorkers volunteer in their local parks through Partnerships for Parks. The grassroots activists organized by New Yorkers for Parks, a citywide coalition that serves as both watchdog and advocate, held park budget cuts to a minimum during the economic downturn of the last few years. Taking this further, however, involving citizens in a system-wide planning process for the parks can translate into greater public support for funding. In cities that have done this, including Seattle and Nashville, voters or elected officials subsequently approved additional spending on parks.  Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Concessions

The parks department needs to do a better job of monitoring whether concessionaires are making agreed-upon improvements to the park facilities they lease, according to an audit by the office of New York City Comptroller William C. Thompson, Jr.

The Department of Parks and Recreation licenses about 600 businesses that pay to operate on parkland or in park buildings. In some cases, the owner of a concession, such as a skating rink, golf course, or restaurant, contracts with the city to spend a certain amount of money to make specific improvements to the facility they operate. According to the comptroller’s report, 37 of the 58 concessions inspected had not completed promised capital improvements totaling $10 million. The audit determined that the department did not make sure that improvements were started and completed on the specified dates and that it did not conduct routine inspections of the work.

The audit also found that it was difficult to track the status of projects because the parks department did not obtain required documentation from concessionaires. It noted that 10 of the 37 businesses with uncompleted capital improvements claimed that the department had authorized them to modify or cancel the projects, but neither the department nor the concessionaires could show paperwork certifying that changes had been requested and approved.

The parks department, however, disputed the findings. The department noted in a press release that the businesses audited met or exceeded their required capital investment by a combined total of more than $15 million. "The inaccuracies of the comptroller’s audit send the wrong message to businesses working with the city," said Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe. Nevertheless, the department said that it was expanding its current policy "to assure that all changes to contract requirements, regardless of size, will be documented in writing" and that it would include reports on concession capital projects in its monthly revenue management meetings.

WHERE SHOULD THE REVENUE GO?

Last year, parks department concessions brought in nearly $60 million. But the parks department doesn’t get to keep the revenue; instead, it goes to the city’s general fund. New Yorkers for Parks and other advocates believe that the revenue should go to the department, in addition to its regular city appropriations. These advocates have been working for years to increase parks funding. They say the extra money would help rebuild the department’s fulltime staff of skilled professionals, which has dropped 60 percent over the last 15 years ago, and fund more recreation programs.

Joseph Pupello, president of the New York Restoration Project, a non-profit group that has been restoring parks in upper Manhattan and the Bronx, believes that concessions can be a growing source of revenue as well as a way to enhance the park experience. "Stop bashing the parks department and starting coming up with creative ways to make concessions a wonderful part of the city," he said. "There is so much new opportunity for creativity and entrepreneurship in parks," particularly in the outer boroughs where the population is growing and parks are being improved. His organization has invested in the New Leaf Café, a restaurant in an historic building in Fort Tryon Park.

Some park supporters worry, however, that increasing the number of concessions could lead to too much or inappropriate commercialization. Their worst fears seemed to be realized last year when the parks department announced that it would contract with Wendy’s to put a restaurant in a closed comfort station in a Bronx park. Others object to turning over more public space to activities, like golf, where people have to pay to play, while neighborhoods where poor people live are short of green space and sports facilities.

Some of these concerns might be allayed by a new breed of concessionaires -- the non-profit organizations that support and help manage the parks. These organizations have as much of an interest in beautifying and improving their parks as they do in raising funds. The Prospect Park Alliance, for example, operates all of the concessions within Prospect Park. It recently won the contract to take over the tennis center at the nearby Parade Grounds, whose previous concessionaire had failed to build a clubhouse and make other promised improvements.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden.

Waterfront 'Access' May Actually Keep Public Out

Over a decade ago, New York City made sweeping changes to its zoning rules that require the construction of public esplanades in new residential and commercial development along its 580 miles of waterfront. The zoning also requires that developers keep open streets that lead to the waterfront.

But the new rules do not apply to industrial areas, and they are now being used in a back handed way to justify conversion of industrially-zoned land to residential. Industrial areas were not required to have public access under the faulty logic that it necessarily interferes with industrial activity. But if decent public access had been required, residents might be more tolerant of their industrial neighbors. What remains of the working waterfront is too often used for warehousing or garbage transfer, or lies vacant while speculators wait for the city to rezone it. This might not be the case if the city had from the start adopted a policy of making these areas more appealing to everyone.

In Greenpoint/Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the City Planning Department is selling its scheme to rezone the industrial waterfront for market-rate high-rise housing by using the upside-down argument that this is the only way the community will get public access to the waterfront. They say that only expensive housing yields developers enough profits so they can build and maintain an esplanade and public access.

The outcome of the rezoning may very well be just the opposite. Even with certain contextual design features built into the zoning, high rise housing is likely to create a wall of luxury apartments sharply separated from this low- rise neighborhood. Luxury rents will put pressures on and displace tenants and homeowners in upland areas without providing new units affordable to people with modest incomes. Without protections for industry, the neighborhood will change even more rapidly from vibrant mixed use community to swank bedroom enclave. Residents now looking forward to a chance to get to the waterfront may discover that the public access they were promised does not work for them or that they cannot even afford to stay in the neighborhood. But by then it will be too late.

Years ago people who now live and work in Williamsburg and Greenpoint came up with a more sensible notion of how to get public access. They developed waterfront plans that call for a mixture of low-rise housing, compatible industry, retailing, and public access to the waterfront. The plans were approved by the City Planning Commission and City Council. The city's rezoning, however, would give them a luxury residential enclave on the waterfront.

Attractively redeveloped waterfronts all over the world include lots of low-rise development with intensely utilized public greenways. In Barcelona, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen government played the leading role, creating opportunities for private development without compromising the public character of the waterfront. Government there does not wait for new development but builds public esplanades in already established neighborhoods. London's Docklands, on the other hand, is a massive waterfront development that followed the private model. Government there had to step in to rescue developers from bankruptcy and eventually ended up spending billions to pay for public amenities.

Another part of the argument by New York City officials is that the old industrial sites are contaminated and soil remediation is so expensive that the costs can only be recovered by building lots of expensive housing. This is only a small part of the truth. The other part is that remediation costs vary widely and are not necessarily budget-busters. Also, nice subsidies are available for low- and mid-rise housing. For the last two decades the city has subsidized the construction of one- to three-family homes affordable to people with modest incomes through a program that was profitable enough to attract lots of private developers. But here is the biggest item that gets left out of calculations: by rezoning their land the city is giving developers huge windfall profits. The city could recover some of these profits and invest them in a way that implements the community's vision for a mixed use waterfront.

Public Planning and Public Money

Behind this logic is the premise that little or no public money should go to revitalize the waterfront. The downtown Brooklyn waterfront, for example, will have a few big commercial developers to pay for a public park that allows people to stroll along the riverfront. The Hudson River greenway would not have been built without its godfathers.

This logic goes back to the 1970s fiscal crisis, which immediately followed the demise of the port. Unfortunately, long after the city's fiscal comeback, the idea that private development is the only option for the public remains a cornerstone of city policy. Even civic and community groups that have been fighting for decades for a public waterfront have come to accept this privatizing logic. The newest generation of community activists has no memory of a time when it was normal for people to expect government to put up the financing for a public benefit.

While communities are told they cannot have subsidies, developers are finding new ways to dip into public coffers to fatten their deals. For example, say you want to build a stadium or convention center with deep public subsidy. You create a public corporation to issue tax-exempt bonds (a form of subsidy), condemn land (a form of subsidy), and limit tax contributions (a form of subsidy). You can also say the bonds will get paid back by taxes on the private owners some time in the distant future, knowing full well that the privates can decide to go elsewhere, end up in bankruptcy court, or plead for public subsidies decades from now when no one will remember who made the promises.

Planning in the public interest should mean that everyone knows the costs and benefits involved. Our elected officials, public servants and communities should make decisions on the waterfront based on a mutually accepted vision of the future, not somebody's bottom line.

Tom Angotti is Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College, City University of NY, editor of Progressive Planning Magazine, and a member of the Task Force on Community-based Planning.

Sludge and Scandal

When Alvarado Sorin gives a tour of the New York Organic Fertilizer Company’s plant in Hunts Point, which processes what was originally the city's raw sewage into fertilizer for farmers, she is sure to warn people about the stink. Few know that stench better. A consultant for the company, and a member of the local community board who serves as the Bronx community liaison for the company, Sorin takes the call anytime the smells inside their plant get too much for local residents. Even with a full quarter mile between the plant and the nearest residence, the calls are frequent.

But ask some local residents, and they will say something else at the plant stinks. "The smell is not just a nuisance," says Elena Conte of Sustainable South Bronx, a Hunts Point environmental group. "It's what's in the smell that concerns folks."

Launched in 1993, the New York Organic Fertilizer Company is the largest facility of its type in the world. It processes up to 40 percent of the city's treated sewage sludge (up to 300 tons a day, according to the company), and has the capacity to handle the city's entire output, if needed. It is the flagship operation for Synagro Technologies Inc., a Houston-based company that bills itself as an "industry leader in biosolids, sludge, and residuals management."

At first glance, the conversion of sewage into commercial fertilizer appears to be an environmental "win-win." Both the 1972 Clean Water Act and the 1988 Ocean Dumping Act put limitations on how cities dispose of the solid waste that passes down toilets, sinks, and gutters. Currently, the choice boils down to one of three options:

- incineration,

- landfill dumping,

- conversion to fertilizer.

That's where the trouble starts. Environmental groups, decrying the cozy relationship between the EPA and industry, have argued over the last two decades that the standards used to determine the safety of recycled sewage are dangerously lax. Of particular concern are so-called "Class B" fertilizers which undergo little more than a brief heating process to kill bacteria and can be spread in certain limited environments such as open pastureland. In 2002 Synagro settled out of court with the family of Shayne Conner, a New Hampshire man who died in his sleep a month after the spread of such fertilizer on a neighboring field. Although the settlement required that the family members state the lack of scientific evidence of the company's complicity, the EPA, in the wake of similar suits, announced last month that it would review its safety standards on 15 chemicals found in recycled sewage sludge and, according to the New York Times, look for pathogens.

As a producer of Class A fertilizer -- a more tightly regulated product that can be mixed with other forms of fertilizer for general agricultural use -- the New York Organic Fertilizer Company's Bronx plant runs its sludge through an intense heating process designed to kill pathogens. Nevertheless, there are concerns over heavy metals, such as iron, lead, and zinc, a byproduct of both industrial waste and human waste.

There was also concern when, last September, there was an explosion at the plant, caused by a volatile mixture of oxygen-rich air and swirling dust inside a silo.

Although the explosion caused no injuries and did damage only to the silo's interior, the New York Post headline -- "Dung Flung" -- caused some apprehension halfway around the world, in Hawaii.

There, the Honolulu City Council was considering a proposal by Synagro for a similar plant. That is undoubtedly why the company purchased tickets to fly Alvarado Sorin and Marta Rivera, chair of community board 2, to Hawaii, where they offered testimony favorable to the company.

"I felt it was very important for your community to know that sometimes media can get a hold of a story and sensationalize it," said Rivera, according to a printed transcript of the December 3 testimony. "Unfortunately, people do not want to hear the truth and the truth is Synagro has been a responsible company."

This little junket caused a different kind of explosion. The Daily News ran two stories in January playing up the quid-pro-quo element of the emerging scandal while also hinting at a possible investigation by the city's Conflict of Interest Board.

The Conflict of Interest Board declines to say now whether or not a complaint has been filed. Rivera, meanwhile, resigned her position as chair of community board 2, though she still remains a member of the board. At a February 3 meeting to hire her successor, Alvarado Sorin, announced that she, too, was resigning as chair of the board's economic development committee but not from the board itself. She took responsibility for the decision to invite Rivera to Honolulu, which she said in retrospect was wrong, but blasted fellow board members for feeding the media the story.

Speaking a day later in the conference room at the New York Organic Fertilizer Company facility, Sorin sounded more conciliatory, focusing on the facility's ongoing attempts to maintain an open dialogue with its harshest critics.

"The community organizations are asking for more accountability from the managers and to have more input," she says. "My operations people have no problem sitting with the people if that's what they want."

Marian Feinberg, health coordinator for the South Bronx Clean Air Coalition, has yet to be convinced. Earlier this month, she and other community members participated in a sitdown with managers following a tour of the plant. It wasn't the first time her organization and the plant had attempted a clear-the-air session, but, while the meeting was long -- "We were there long enough that we all had to go home and wash our coats and clothes," she says -- she does not believe that much was accomplished.

More important than direct communication, Feinberg says, is the pressure finally coming from outside the borough. The demand for better, cleaner process is increasing, thanks to:

- the EPA standards review

- the personal injury lawsuits

- a pending state Department of Environmental Conservation review of the New York Organic Fertilizer Company's airborne emissions permit

- the growing number of grass roots groups willing to trade information and keep one another apprised of the latest developments

"We will meet whatever guidelines the state and federal governments set for us," Sorin says.

It is doubtful whether that pressure will be enough to result in zero odors and close-to-zero emissions, which is why plant opponents have created a slogan that has become their rallying cry -- "clean it up or shut it down."

Children and Pollution: School Buses, Second-Hand Smoke

Community groups have been fighting diesel fuel emissions for years. Finally, in late January, four bus companies representing 60 percent of the yellow school buses that are contracted by the Department of Education agreed to stop idling when they are parked near schools following an investigation by State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer. Three companies have also agreed to retrofit some buses with new exhaust filters.

Spitzer’s office reportedly found that the four companies routinely parked their buses with the engine running for as long as half an hour, even though city law limits idling to three minutes. Idling by the four school bus companies, according to the attorney general, resulted in annual emissions in the metropolitan region of some 1.3 tons of particulate matter, 20 tons of carbon monoxide and 60 tons of nitrogen oxides. The companies are required to monitor their drivers and will have to comply with the agreement within 30 days, by the end of February. They will also pay the city $47,000 to plant trees near schools.

(The Attorney General will continue to investigate a dozen smaller companies that operate the remaining 40 percent of buses.)

THE DANGERS OF DIESEL

New York City’s poor air quality is particularly hard on children, whose lungs are fragile and still developing. The city’s 6,000 yellow school buses, because they are run on diesel fuel, are particularly lethal to their 173,000 riders: Particles from diesel exhaust are carcinogenic; truck and car emissions can lead to heart disease; air pollution aggravates allergies, asthma and other respiratory illness. “Major airborne pollutants such as lead, carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide, contribute to the city’s high incidence of asthma (double the New York State average, in some neighborhoods, and up to six times the national average) and other respiratory ailments,” says the New York League of Conservation Voters. And it’s worse for those inside the bus than those outside, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

More than two years ago, the New York State Power Authority launched a $6 million program to install diesel fuel pollution control systems on a thousand of the buses. “Diesel particulate filters trap exhaust particles and, combined with an engine adjustment and the switch to using ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel (with all related costs covered by the power authority), emissions on the school buses are reduced by 90 percent,” Gotham Gazette reported last June. But not one school bus company took advantage of the free program.

One of the sites Spitzer’s office investigated was a public school in the East Village, says Rebecca Kalin of Asthma Free School Zone, which works to reduce asthma-related absenteeism and illness by working with parents, teachers, school staff and area residents to improve air quality in and around public schools. “There are three schools inside the building and 11 school buses outside,” Kalin says. “They idle as long as two hours at a time. It’s a narrow street and the teachers slam their windows shut at pick-up time. And cars trying to pass get stuck by the buses, so they idle, too.”

Kalin is working with City Councilmember Margarita LĂłpez to introduce legislature to designate all public schools in the city asthma-free school zones and post a sign saying as much. “We hope the sign will become like the Good Housekeeping Seal,” Kalin says. “We want to empower people to knock on windows, point to the sign, and ask the driver to turn off the engine.”

INFANTS AND SMOKERS

To further emphasize the danger of the poor air quality in New York City, a new study(in pdf format) finds that exposure to a combination of smoke and pollutants is even worse than exposure to just one factor. It causes lower birth-weight and smaller head circumference in newborns, standard measurements of fetal growth. Lower birth weight has been linked with learning disabilities.

The study, which was conducted by Columbia University’s Center for Children's Environmental Health, compared 226 infants whose mothers lived during pregnancy in households with an active smoker to those whose mothers did not. The newborns of mothers living with smokers weighed seven percent less than average and the circumferences of their heads were three percent smaller. The women in the study were African-Americans and Dominicans living in Washington Heights, central Harlem and the South Bronx, where the asthma rates are the highest nationwide and the rates of low birth weight are the highest in the city.

Using a new technique, researchers tracked the pollutants by measuring DNA damage to get an individual measure of exposure to hydrocarbons, which are caused by truck and car emissions, home heating systems and power generation. “These findings underscore the importance of smoking bans, public education and policies that limit pollution,” said center director Dr. Frederica Perera.

The findings are noteworthy because pollutants affect the human body simultaneously, rather than separately, which is the way they are frequently studied, the researchers told the New York Times : “Previous research has explored the effect of secondhand smoke and urban air pollution independently on fetuses.”

Sasha Nyary, formerly on the staff of Life Magazine and the mother of a public school student, edits the newsletter of The Fifth Avenue Committee, a community-based organization.

The Feds And Clean Air

New York City has traditionally regarded clean air as more of a journey than a destination. Since Congress passed the first Clean Air Act in 1970, ozone, smog, and particulate matter levels have decreased dramatically throughout the city and the surrounding region. Still, with the prevailing winds bringing in a fresh (or, rather, stale) supply of pollution every day, local levels remain disappointingly high when measured against most other regions of the country.

The Bush Administration says it would like to change that. In 2002 it proposed a new rule that it says will reduce emissions faster by introducing a more flexible permit process. Critics, however, argue that "flexibility" is simply a code word for relaxed standards and are fighting the proposal.

The Bush argument, which parallels that of administration allies in the coal and power industries, has it that the current interpretation of "major" is absurdly low. In 1999, for example, the Environmental Protection Agency filed seven lawsuits against utilities that had modified their facilities without reapplying for a new permit. In one suit, the agency cited a new furnace floor and replaced steam drum parts as sufficiently major modifications.

Utility industry lobbyists and the agency's current leadership argue that such strict interpretations -- and the cost of buying the new "best available" technologies that goes into qualifying for a new permit -- only encourages power companies to let their aging power plants grow dirtier and less efficient.

Given the challenge of cleaning up its own skies, you would think that New York City would be sympathetic to such arguments. Not so. Last March, together with the city of San Francisco and 27 Connecticut municipalities, the city joined in a 14-state lawsuit that aims to block the Environmental Protection Agency’s rule change.

For the city, the issue comes down to health care costs: More upwind pollutants means more asthma and more hospitalization cases.

"It doesn't take a genius to see that this is a rollback," says one city attorney close to the case. "If they're not rollbacks, the government has a role to explain why they aren't, and they haven't done that yet."

For decades, Republican lawmakers and their conservative Democratic allies pushed for compromises that would take regulatory power away from the Environmental Protection Agency. Now, states and municipalities, even as they flex their own regulatory muscles, are insisting that the federal agency retain its tough Clinton-era standards.

The one state leading the way is New York. Attorney General Eliot Spitzer has built on the successes of his predecessors in going after the out-of-state polluters whose smokestacks contribute to acid rain and other local problems.

Judith Enck, a policy advisor to Spitzer, says the Office of the Attorney General has targeted 30 coal-burning power plants both in New York and out of state over the last five years. Until last November, when the Environmental Protection Agency suspended ongoing investigations into 50 facilities, citing the rule change, the state was counting on the federal government to carry out a similar crackdown in other regions.

"Three years into the dance, we lost our partner," says Enck.

City lawyers, meanwhile, have undergone a role reversal. Only four years ago the city was the defendant in a civil lawsuit citing the Clean Air Act. Settled in 2000, the lawsuit stemmed from EPA charges that the New York City Department of Sanitation had been improperly handling discarded refrigerators and air conditioners, allowing the ozone layer-depleting freon inside to escape into the atmosphere. In the final settlement, the city agreed to pay a $1 million penalty and implement $3 million in new environmental programs.

Since then, the city has worked to get its own environmental house in order. Included in that effort are a series of epidemiological surveys studying the direct and indirect health impacts of air pollution on city residents.

One city attorney, speaking anonymously, says the Law Department was "happy to jump in" on the states' case, albeit in a background role.

The city has assisted the state in building its case mainly by offering local statistics on the hospitalization costs related to ozone and fine particulate matter -- the two local byproducts of increased upwind pollution. Dr. Thomas Frieden, commissioner of the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, says these statistics are the product of a two year long campaign to fill in the "major gaps" on local air pollution and its after-effects.

"What we know is that particulate matter and the amount of particulate matter in the air correlates with heart disease and death," Frieden says. "Both particulate and ozone are reasonable markers of air quality problems that may exacerbate asthma and other conditions for vulnerable people."

This linkage has been enough for the states’ legal argument to include dramatic information about health care in the city. Thanks in part to the city's data, federal judges have agreed to put the federal rules change on hold pending the outcome of the case. A three judge panel in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, the primary venue for such policy disputes, made its decision on December 23, just three days before the revised policy was slated to go into effect.

Mike Leavitt, the new commissioner of the Environmental Protection Agency, says the agency will "vigorously defend" the new rule. He also maintains, however, that the agency, via the Department of Justice, would continue pressing the 1999 lawsuits filed under the old, Clinton-era interpretations.

Meanwhile, the former Utah governor has pushed the wind-borne pollutants debate into a new direction, unveiling the "Interstate Air Quality Rule." Aimed at the 29 states that currently fail to meet federal standards, the new rule would nationalize the "cap and trade" pollution credits program -- an outgrowth of the 1990 Clean Air Act.

"Our belief is simple: people do the right things faster, and they do more of it, when they have an incentive and the latitude to do it in a way that makes sense for them," said Leavitt in a Jan. 19 speech at the Edison Electric Institute, an electric utilities trade group.

Such comments, while rooted in federalist Republican doctrine, acknowledge the failures of a policing system that, to date, has allowed more than half the nation's states and 530 individual counties to skirt compliance. With air standards set to get even tougher in the coming years, it also acknowledges that, like it or not, the federal government has to play a stronger leadership role on the environmental front -- something Enck and her colleagues have been calling for all along.

"The EPA has been missing in action when it comes to air pollution," Enck says. "We truly want them involved in these cases."

Graffiti 2004

An unused building a few blocks from City Hall in lower Manhattan has become a magnet for grafitti writers. |

"It's in the middle of the night, it's in the middle of the afternoon," patrol president Frank Kotnik said. "They are teenage girls. They are middle-aged men. They are white. They are black. They are poor. They are from affluent families. But one thing is for sure. They keep on coming."

While some New Yorkers look at graffiti nostalgically as an art movement from a bygone era, and others as an old war long since won, plenty of New Yorkers say it is a problem that has not gone away; they fear it is getting worse. In response, Councilmember Hiram Monserrate of Queens has introduced a bill that would require property owners to take responsibility for their defaced buildings. Owners of commercial or residential buildings with six or more units would have 30 days to remove graffiti before the city issues fines of up to $300. The bill also calls on the state to provide property tax exemptions for those landlords in order to cover the cost of graffiti removal.

"Graffiti continues to be a major nuisance in many areas of this city, fostering an atmosphere of neglect," said Councilmember Peter Vallone, a co-sponsor of the bill. "We've reached a point where something more has to be done, because there are many owners in my district and other neighborhoods that have shown every inclination that they will never clean up their properties."

There is opposition to the measure. Opponents are not arguing artistic freedom, but claiming economic hardship. Neal Dunatov of Small Property Owners of New York said a fine would burden property owners already suffering from the economic downturn and the increase in property taxes.

FROM SUBWAYS TO STREETS

The city's multi-agency Anti-Graffiti Task Force has removed more than 16.3 million square feet of graffiti from about 6,250 sites across New York City since July 2002. And the task force is not alone. Since July 2002, the Department of Transportation has painted over more than 4.1 million square feet of graffiti on areas surrounding the New York City highways. During that same time, the Department of Parks and Recreation has removed over two million square feet. Other city agencies have removed scrawls from hundreds of other sites. The police department has made 468 arrests for graffiti-related crimes.

These efforts are not driven solely by aesthetic considerations. Graffiti, many believe, conveys an image of urban decay and despair. In expounding their "broken windows" theory in 1982, conservative theorists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling wrote in an article, "If the first broken window in a building is not repaired, then people who like breaking windows will assume that no one cares about the building and more windows will be broken. Soon the building will have no windows."

When graffiti emerged in New York City on a large scale in the mid-1960s, it was primarily the work of political activists and street gangs. In 1971 the New York Times profiled a Washington Heights writer who went by the tag TAKI, marking the first mainstream recognition of the graffiti subculture. Writing rapidly spread to the subways. A 1973 article in New York magazine by Richard Goldstein entitled "The Graffiti Hit Parade" hailed the artistic value of the graffiti artists. But many saw the bulk of graffiti writers simply as vandals, tagging as many subway cars as possible, much to the frustration of a beleaguered Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

By the late 1970s, the authority made elimination of graffiti a high priority, buffing trains to remove it and increasing security in train yards. In the mid-1980s, the city restricted the sale of spray paint to minors, further reducing graffiti. On May 12, 1989, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority officially declared graffiti dead in the system.

It is not that graffiti has exactly risen from the dead. It simply moved from the train yards to city streets. And there it has stayed.

"We have seen a resurgence in graffiti in this city, matching a rise in gang activity in some areas," Monserrate said. "These gangs use graffiti as a source of communication. The reality is, the longer it stays up, the worse the criminal activity in an area becomes. The city is suffering at the hands of these graffiti vandals, who I refuse to call artists."

HOLDING OWNERS ACCOUNTABLE

In response, most council members have launched anti-graffiti initiatives in their districts. And in January, 2003, Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed two laws -- one that toughened penalties for people repeatedly arrested for doing graffiti and another that makes it more difficult for minors to buy acid etching cream that some use to make their mark on windows and other surfaces.

But some say additional legislative efforts are needed to address the many privately owned sites around the city smeared with graffiti. Currently, before cleaners -- whether they are paid city workers or community volunteers -- can clean a property, the owner must sign a waiver granting them permission.

"It's a matter of access and liability," said Councilmember Anthony Avella, who has led clean-up campaigns and founded the North Shore Anti-Graffiti Volunteers. "We've got the supplies, we've got the manpower, and we do it for nothing, but if we can't get the owner to sign a waiver giving us permission, we can't gain access."

"I can't tell you how much time we've spent calling and banging on doors, but either they [the owners] can't be found or just don't care enough to have it cleaned," testified Councilmember Melinda Katz.

"It's very frustrating that no matter how hard we try to remove this blight, there are many landlords, mostly absentee landlords, that just don't give a damn," Councilmember Philip Reed said. He supports placing liens on properties whose owners ignore multiple violations.

Kotnick of the Glendale Civilian Observation Patrol admits Monserrate's bill "would victimize the victim twice, hitting them with a fine on top of the act of vandalism," but, he adds, "This isn't aimed at the responsible, law-abiding owners. There are property owners who have lost faith in the system and simply collect their rents and don't put a dime back into their properties."

The legislation faces an uphill battle nonetheless. Testifying at the hearing, Community Assistance Unit Commissioner Jonathan Greenspun said he "applauds the concept" of Monserrate's proposal. But he called the measure "unworkable" because it does not define what graffiti is, nor address the issue of added costs from the massive influx of requests for clean-ups that the legislation would drive.

In the meantime, private groups continue to do what they can. The Greater Ridgewood Restoration Corp. -- a non-profit organization that charges a $100 fee for cleanings in the area covered by Community Board 5 -- uses labor supplied by a work release program from the Department of Corrections and a community service program from the Department of Probation.

As one former "tagger" who "bombed" train yards and other sites throughout Brooklyn in the 1990s, Eric Berg adamantly opposes prison sentences for graffiti vandals, but concedes that such laws were definitely a deterrent for him. "As I developed a goal for my life," Berg said, "I no longer felt that doing graffiti was a risk worth taking."

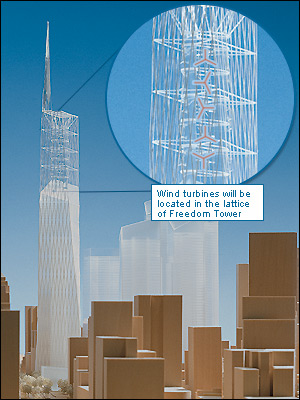

Green Buildings

The latest design of the Freedom Tower at Ground Zero includes power-generating wind turbines in the upper section - or "lattice" - of the building. |

To the uninitiated, this might sound like a Don Quixote-like delusion; putting windmills in a skyscraper certainly has never been done before. But Freedom Tower's innovations are actually part of a trend. Whether the windmills prove feasible or not, a number of such environmentally conscious skyscrapers are going up across New York City. These so-called "green buildings," a term that is being used with increasing frequency, are designed to be healthier and more comfortable for the people living or working inside them. They aim to save energy, produce less pollution and conserve natural resources.

For years, New York builders were slow to embrace the idea of green buildings. But this is abruptly changing. "In the next three to four years," says Wayne Tusa of the U.S. Green Building Council, "the number of green apartments in New York City will rise from essentially zero to perhaps 3,000."

It's already happening. Just down the block from the proposed Freedom Tower, in Battery Park City, stands a residential high-rise billed as one of the most environmentally friendly in any city in the world. The Solaire, which opened last summer, features solar panels that provide five percent of the building's electricity; water for the toilets that has been recycled from the showers, sinks and dishwashers; and paints and adhesives that have no toxic or carcinogenic chemicals.

Advocates of such green buildings conjure up a city slowly filling with occupants paying less money for energy, feeling healthier and enjoying the knowledge that in some small way, their actions are making New York City an easier place to live and breathe. Critics question whether such features can ever have any significant impact on the environment in a city the size of New York, and whether they are worth the cost.

WHAT MAKES IT GREEN?

The environmentally conscious practices begin during construction, as builders seek out recycled materials and avoid those that give off harmful gases. (One such harmful material is particleboard, which is made with glues that give off formaldehyde.) And the builders recycle as much construction debris as possible.

Existing buildings can be renovated to consume less energy and be more environmentally friendly. For example, developers can keep the existing steel and the masonry frame, but replace the walls, windows and heating and cooling systems. In its New York offices, the Natural Resources Defense Council renovated a loft in the Flatiron District to emphasize natural lighting by adding a three-story atrium.

A former brewery in Brooklyn, now an apartment building, was renovated with a number of environmentally friendly features, including something of a meadow on its roof. Advocates of such green roofs say they keep buildings cooler in the summer and can also filter the air and rainwater, while providing a habitat for birds, butterflies and bees.

Once in operation, green buildings employ a variety of features that distinguish them from more conventional buildings. Some use solar panels to generate electricity and heat water; others put up windows that are double paned, filled with an insulating gas and treated with a special glazing that lets light but not heat pass through. Many of the buildings use special filters to clean more pollutants from the air than those in standard buildings. And in some, residents can take advantage of special storage areas for bicycles or landscaped roof decks, while the cleaning staff use products free of toxic chemicals.

Such practices, advocates argue, do more than benefit their occupants. Using less electricity can cut pollution from power plants and reduce, at least theoretically, the risk of a blackout that would affect all New Yorkers. In the same way, using less water helps everyone, especially during water shortages such as the one in 2002.

GREEN BUILDINGS IN NEW YORK

While outsiders might view New York City as the opposite of environmentally friendly, the city's very density means that residents use less energy and other resources than most Americans. "The city has long embodied many green principles," according to the Museum of the City of New York which is presenting an exhibition on "sustainable architecture" until January 19. As evidence, the museum cites Central Park, mass transit and the design of early skyscrapers. But it says, "In the post-World War II era, changes in zoning regulations and the widespread use of air-conditioning contributed to the design of glass-and-steel boxes...Wrapped in miles of inoperable, tinted-glass windows, high-rises housed office workers who, it was argued, no longer needed to be close to sources of natural light and ventilation. These buildings require massive amounts of fossil fuels to operate."

Some observers see signs that the attitudes that created such buildings are changing. They point to a number of buildings that have recently opened in the city.

The new high rise at 4 Times Square, popularly known as the Conde Nast building, boasts 1.6 million square feet of "environmentally conscious design," including circulating 50 percent more air through the building than is required by law and using non-toxic cleaning materials.

In residences, the poster child for green building is the Solaire. From the outside, the Solaire is almost indistinguishable from the neighboring buildings, but its guts -- the solar panels, the special air filters and so on -- are what make it special. In fact, some residents may barely notice the Solaire's unique features at first. Lyron Andrews moved into the Solaire not because he was looking for an environmental super-structure, but because he loved the serenity of the neighborhood, the acres of play space for his daughter and the striking views of the Hudson River.

But now Andrews and his family are grateful for other aspects of their new home. Andrews' 6-year-old daughter suffers from allergies. In their old apartment in Park Slope, she had to use an air purifier. But because the Solaire filters fresh air coming into the building twice, Andrews says, "After only one night in the new building, her allergies were gone, even without the purifier."

The Solaire is a luxury development. The eight-story building now going up at 1400 Fifth Avenue in East Harlem is not. Two thirds of its 128 apartments are reserved for buyers with annual incomes between $53,000 and $103,000, and many of the apartments will look out on a housing project. But like the Solaire, 1400 Fifth is considered to be among the country's most environmentally friendly urban designs. "Everyone deserves affordable housing that is built in a way that sustains the environment," says Carlton Brown of Full Spectrum New York, the developer of 1400 Fifth.

To do this, Brown starts with the premise that waste costs money. Well-insulated, tightly sealed windows will allow for a smaller heating and cooling system. While most builders make their walls on the construction site, Brown uses walls prefabricated in a factory. He also uses a lightweight composite recycled steel frame, which allows him to use less masonry. Such practices consume less material than conventional construction methods, produce less trash to send to the landfill -- and cut costs.

With that money, Brown says, "you can reinvest in those areas that will cost a little more," like recycled or renewable materials or a highly energy efficient heating and cooling system. (The heating and cooling at 1400 Fifth comes from a geothermal heat pump, a device that takes advantage of the relatively unchanging underground temperature of the earth, which is cooler than the air in the summer and warmer in the winter.)

Taken with the rest of the efficiency measures, 1400 Fifth is expected to eat up 70 percent less energy than a comparable multifamily building. "In the end, the costs about even out," Brown says. "A sustainable environment can be built at any income level."

And there are other environmentally sound projects that have been built with a close eye on costs. These include 299 East Third Street, a new affordable housing development in Alphabet City, and the award-winning Melrose Commons II affordable housing apartments in the South Bronx.

But expense remains a major concern. While developers of 1400 Fifth say the project will cost no more than a conventional building, The Solaire cost eight percent to 14 percent more than a conventional building of the same size. And its developer, Russell C. Albanese, recently told the New York Times that the 293 apartments in the building rent at about five percent above the going market rate.

It seems clear that, for now at least, green buildings will be hard pressed to succeed if they cannot keep costs down. A recent survey by Roper ASW found that few Americans are willing to pay a lot extra for environmentally friendly products. "If you look at the green consumer," environmental marketing consultant Jacquelyn Ottman told Indoor Air, the "consumer part is more important than the green part. People buy laundry detergent to get their clothes clean, not to save the planet."

And a Clifton, Virginia, developer has pointed out that most people looking for a place to live tend to focus more on location, the floor plan and nearby schools than on non-toxic insulation and energy efficient cooling.

THE GOVERNMENT ROLE

Cities such as Austin, Texas, and San Francisco have long featured environmentally sound construction, but the movement did really begin in New York City until recently, when the state and city governments began getting involved.

In 2000, Governor George Pataki unveiled a green building tax credit, the first one of its kind in the country, that has allowed some developers of environmentally friendly buildings to write off as much as $6 million on their tax bill.

The impetus for the Solaire came from the Battery Park City Authority, a semi-autonomous state entity, which in 2000 adopted some of the most stringent green building requirements in the country. When these requirements are applied to the next generation of buildings to go up in Battery Park City, they will make that area of lower Manhattan one of the most environmentally-conscious urban neighborhoods in the world.

Another big institutional booster has been the city itself. In 1999, the Department of Design and Construction developed a set of guidelines that encourage, though do not require, environmentally sound building methods for municipal projects. So far, the guidelines have led to 16 pilot projects with a total construction cost of approximately $700 million. One, the Queens Botanical Garden Administration Building, now under construction, will be a pioneer in the field. Among other features, it will include a system for collecting and reusing rainwater.

And most recently, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a citywide competition that would give awards of $5,000 for environmentally conscious designs for various types of buildings. "With major renewal projects in Lower Manhattan, downtown Brooklyn, western Queens, Greenpoint/Williamsburg and the far West Side of Manhattan," said Bloomberg, "the need for sustainable development is as great today as in any time in our city's history."

Nothing going on in New York, though, will do more to affect the future of design and construction than the redevelopment of the World Trade Center site. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation has committed itself to incorporating sustainable design in the rebuilding plans, and the Port Authority has earmarked $100 million in capital funds for it. The details are slow in coming, and it is unclear how all this will ultimately be reflected in the final designs -- other than the wind-powered Freedom Tower. But if the most talked-about architecture on earth does indeed go green, it may create the kind of momentum that eventually persuades the entire New York construction industry to come around on the idea of building environmentally conscious apartments and offices.

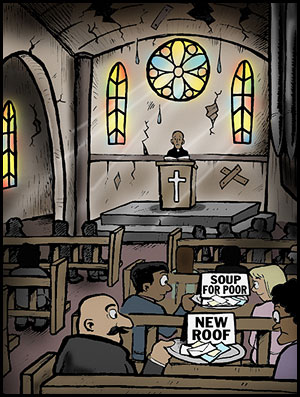

Religion And Historic Preservation

Also in this series, four NYC congregations try to balance their religous missions with preserving their buildings:

|

With carefully chosen words and an inspired delivery, Reverend James Kowalski, the dean of St. John the Divine in upper Manhattan, urged his audience to support the world's largest Gothic cathedral.

The massive Episcopal church, which broke ground in 1892, the same year that Ellis Island opened, needs $20 million in repairs, the pastor said. In addition to being a house of worship, it also serves as a school, homeless shelter, soup kitchen, art museum, concert hall, and one of the most visited tourist destinations in the city - all of which costs money.

"We dare to say that we want to be a cathedral for all people," Kowalski said. "With your help, this cathedral will have more of the resources it needs to carry out that mission faithfully, respectful of the treasures of its architectural legacy."

But on this day, the reverend's exhortations were not aimed at his congregation nor was he trying to solicit contributions for the offering plate.

Kowalski was testifying before the New York City's Landmarks Preservation Commission. He was trying to broker a deal that would preserve the cathedral as a historic landmark and still allow the church to lease a portion of the surrounding grounds to Columbia University, which is interested in putting a 20-story building on the site.

The deal eventually fell apart.

Responding to an outcry from neighbors, the New York City Council rejected the arrangement in October, arguing that development would threaten the historic site. It was one of the few times in city history that the council overturned a landmarks designation.

The case of St. John the Divine is just the most recent example of conflict between advocates for historic preservation and religious institutions in New York City. The locations, architectural details, and religions vary, but similar issues often emerge. (Read profiles of four houses of worship across the city that are struggling to balance history and ministry.)

On one side are those who argue that many churches, synagogues, and mosques are historic treasures. In a sense, they say, the buildings belong to the whole city and must be preserved for future generations.

On the other side are religious leaders and congregations who argue that historic preservation can pose significant hardships. If all the money goes to maintaining century-old buildings, they contend, there is nothing left for charity.

BIRTH OF THE LANDMARK

In response to the demolition of Pennsylvania Station in 1963, Mayor Robert Wagner established the Landmarks Preservation Commission, a city agency charged with protecting sites and buildings that hold "special character or special historical or aesthetic interest."

Since it was founded, the Landmarks Preservation Commission has designated over 1,200 sites and 79 historic districts in the city.

Religious institutions are unique and must be preserved, advocates say. They are some of the oldest structures in the city, dating back to before the Revolutionary War. The spires, domes, and towers were often designed by the most prominent architects of the time, and interiors are decorated with rare craftsmanship and materials. They are also symbolic - not only for those who worship within their walls - but of the struggle for religious freedoms in America and the ethnic diversity of New York.

"Our religious institutions are treasures," said Robert Tierney, chair of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. "Historically, architecturally, and culturally - they make a major contribution to our city."

Some congregations welcome landmark designation because they fear the demise of their historic - and spiritually significant - places.

"Most of the time, older congregations want to preserve whatever they can and are desperate for the [landmark] designation," said City Councilmember Simcha Felder, who chairs the council's landmarks committee.

In Harlem, one congregation is currently trying to use landmark status to re-open its church, St. Thomas the Apostle, which the Archdiocese of New York closed in August. Each week, parishioners still gather to say prayers outside their padlocked building, and they protest in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral in midtown Manhattan. (Read more about the church.)

A LEGACY OF CONFLICT

There is also a long history of conflict between historic preservation and religious institutions in New York City.

In 1918, St. John's Chapel on Varick Street in lower Manhattan was demolished. Those who wanted to preserve the chapel included Theodore Roosevelt, Mayor George McClellan, and banker J.P. Morgan, but the rector of Trinity Church, which owned the property, said that "to care for ancient monuments of civic interest" was not the church's primary responsibility.

For the next five decades, many historic buildings - including churches and synagogues - were torn down to make way for new construction.

While landmark status preserves sites, it also carries additional regulations beyond traditional building and zoning codes. If a building or site has a landmark designation, for example, the owners must get approval from the commission before construction or even repairs can be performed. The commission considers issues such as how windows should be repaired, what kinds of materials are used to fix a roof, and where air conditioning units are installed.

And so some religious groups want to control their own properties and they oppose - or at least are wary - of landmark status.

One of the most famous conflicts in the city's history involved St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church on 51st Street and Park Avenue. In 1980, the church proposed demolishing its community house and replacing it with a 59-story office tower. Neighbors and preservation groups vigorously opposed the idea. When the Landmarks Preservation Commission blocked the plans, the church sued the city, citing the First Amendment. The legal battle lasted until 1991, when the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the city.

CHURCH VS. STATE

For some religious leaders, historic preservation - at least as it is currently practiced under New York City law - is a violation of basic religious freedoms.

Churches, mosques, and synagogues can be designated as landmarks even over the objections of religious leaders or trustees. In these instances, opponents say, the government is interfering with the mission and finances of a house of worship.

"Every dollar that comes into a church is for the purpose of ministry," argues Reverend N. J. L'Heureux, director of the Queens Federation of Churches and chairman of a lobbying group that opposes landmark status for religious properties. "The government should not be able to come in and say that those religious dollars must be used for museum creation."

During the New York City Charter revision process in 1989, L'Heureux's group, the Interfaith Commission on Landmarking of Religious Property, was successful in placing on the ballot an amendment to create a special, independent tribunal to hear the appeals of religious organizations that feel the Landmarks Preservation Commission has made unfair decisions. They unsuccessfully lobbied for a change in state law that would require consent of a church or synagogue before landmark regulations could be applied to a property. And in 1997, the group opposed a City Council law that would have allowed fines for failure to repair landmark designated buildings.

"The Interfaith Commission came to the conclusion that landmark status is one of the biggest threats to religious congregations," said L'Heureux.

Advocates for historic preservation argue that religion is not an exemption from the law.

"When a Catholic priest drives a car, he must have a drivers license; when a Baptist pastor hires a janitor to mop up, he must pay minimum wage; and when a Presbyterian minister invests money, he must abide by security regulations," said Kent Barwick of the Municipal Art Society. "Our society is governed by regulations."

Still in recent years, the battles over church-state land use issues have continued, even at the highest levels of government.

In 1993, Congress passed a law that exempted religious institutions from certain land-use rules on the basis that they might infringe on religious freedoms. The law was eventually declared unconstitutional.

And this past summer, President George W. Bush allowed federal grants to be used to renovate historic religious landmarks designated by the National Parks Service. Some are concerned it may break down church-state barriers by using taxpayer money for religious endeavors.

THE COST OF PRESERVATION

Most congregations are not primarily concerned with church-state issues, rather they feel threatened by changes in demographics and what they mean for their future.

In recent years, city congregations have lost members to the suburbs, neighborhoods have changed from one dominant ethnic group to another, and mainline denominations have seen drastic declines in attendance. Many churches, synagogues, and mosques simply don't have the money to maintain their buildings, and so they are looking for ways to generate revenue.

"We identified it as a crisis 25 years ago and it is still with us," said Anne Friedman of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, an organization that offers financial and consulting services to help preserve historic sites. "Particularly in New York City where real estate is so valuable, we will continue to see increasing development pressure on or near historic religious properties."

For example, West-Park Presbyterian, a 100-member congregation on 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, learned that it could cost up to $8 million to repair the roof and crumbling stonework on the outside of the church. The church's endowment will run out in two to three years, the pastor said, and current income cannot cover the costs. The congregation decided to explore selling the property to developers who would demolish it and replace it with an apartment building. (Read more about the church)

"When you are looking at repairs that are that large, you're faced with serious questions," said Reverend Robert Brashear.

Still there are resources and provisions to help religious institutions.

There are grant and loan programs to help churches, mosques, and synagogues. They don't pay taxes because of their non-profit status and many congregations also qualify for certain zoning exemptions. And the city's landmark law also includes a hardship appeal, a provision that allows religious institutions to challenge Landmark Preservation Commission decisions if they feel it presents an extreme economic situation.

"Most often it is not a case of some poor church in Bed-Stuy that wants to fix their roof and the city is telling them they have to use solid gold shingles," said Barwick. "These conflicts happen on Park Avenue, where someone says `we can make a lot of money for charitable purposes by selling off the building.'"

WHOSE HISTORY?

Just what is historically significant and who gets to decide what is important and what is not often fuels debate between houses of worship and their neighbors.