The natural gas that boiled the water for a cup of tea on a stove in Queens Village last night began its journey near Nova Scotia some 140 million years ago. The muddy bottom of a lush swamp turned into something harder and began buckling. Plant and animal matter that had decayed and turned into methane and propane filled the gap underneath the buckled surface and remained there for eons.

Other articles in this series:

|

Not long ago, a drill bit finally hit the pocket to extract these ancient gases and pipelines brought them the thousand miles to the grills and stoves, as well as the furnaces, clothing dryers and power plants, of New York City.

The odyssey of natural gas is impressive. Only decades ago, the fuel was viewed as nothing more than a pesky byproduct of petroleum, a nuisance that made it more difficult to extract the "black gold" underneath.

Now natural gas itself has become a kind of gold. It's not just for breakfast anymore: Many city homeowners made the switch from oil to gas heat for their furnaces in the mid-1990s, and federal clean-air legislation pushed local power plants to do the same, with some wonderful results: cleaner facilities, better fuel efficiency, and less dependence on a worldwide marketplace dominated by OPEC oil ministers.

But as demand has risen, so too has cost. The federal Energy Information Administration predicted earlier this month that the average American family will pay nine percent more for natural gas heat this winter than last.

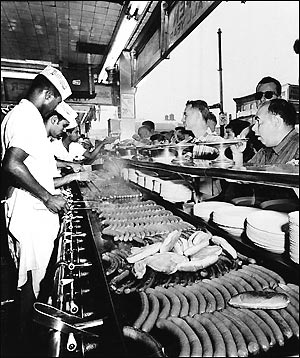

Cooking with natural gas at Coney Island, 1958.

This will still be less than for oil -- an estimated average of $841 compared to $927 -- but it is not likely to stay that way, according to New York State Assemblyman Paul Tonko, chairman of the Assembly Energy Committee. And there is a danger, Tonko says, in relying more and more on this one fuel source: "As natural gas becomes in larger measure the fuel of choice for both heating and electricity generation, we're creating a very risky situation for consumers."

THE JOURNEY

The term "natural gas" often leads to confusion. Some confuse it with the gasoline used in cars. But at room temperature, natural gas is just that, a gas, while gasoline is a liquid. Natural gas, says Ed Yutkowitz, a spokesman for Keyspan, can also be confused with the gas that lit New York's streets and fueled its stoves until the 1950s. That gas, which was highly toxic, came from superheating coal. But, beginning in the middle of the 20th century, companies began building pipelines to transport gas itself, providing for a far cleaner energy source.

The gas that Con Edison, Keyspan and smaller suppliers deliver to customers in New York City comes from places throughout the southwest United States and Canada -- a domestic marketplace impervious to foreign competition. Some of the gas has been piped down from the waters off Sable Island, a skinny piece of land about 100 miles off the southwest coast of Nova Scotia. Once known as "the graveyard of the Atlantic" because of the hazard it posed for ships, it is now home to six gas fields.

When the drill hits the pocket, the hot gas, suddenly liberated by the reduction in pressure, rises upward to the wellhead. At Sable Island, water is removed from the gas on off shore platforms before the gas goes via pipes to Goldboro, a small town that was once the scene of a gold rush and now hopes to profit from an energy boom. There, engineers filter out byproducts and impurities, such as sand and rock. Once processed, the gas is compressed and pushed down a new set of pipelines.

In some countries, the gas is chilled to minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit to get it into liquid form. Then it is loaded on tankers and shipped. But in the United States and Canada, the gas remains in its gaseous state.

Over the last century, more than a million miles of pipeline have been built in North America, connecting hundreds of natural gas wells in the Rockies, Gulf of Mexico and Appalachian Mountain regions to the burners on your stove. Like tributaries of a river, the pipelines keep feeding into other pipelines, the gas propelled along the route by pressure. Interstate pipelines, up to 42 inches wide, feature compressor stations every 50 miles that keep the gas pressurized. At top pressure, the gas moves at a speed of roughly 30 miles per hour.

At certain central locations -– so-called hubs in Louisiana, Illinois and Ontario -- commodities traders in suits and ties take over from the engineers in jeans and t-shirts. Buying and selling multimillion dollar contracts, they act as middlemen between the energy companies that extract the gas and the major utilities that use it to supply customers with heat in the winter and a little extra electricity in the summer. Since 1990, when the government deregulated the market, just about anybody with enough money can go into business as a natural gas middleman or speculator. Buying up cheap natural gas delivery contracts and reselling them whenever prices spiked transformed Houston-based Enron Inc. from a humble pipeline company into one of the most profitable companies of the 1990s, until greed helped precipitate its fall from grace.

THROUGH THE 'CITY GATE'

The New York Mercantile Exchange, or NYMEX, is the primary scene for buying and selling natural gas contracts. Once bought, these contracts can be resold or cashed in for delivery at the Henry Hub, a convergence point for six regional pipelines located in western Louisiana. Like the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the daily price of Henry Hub contracts serves as a benchmark for the overall cost of American natural gas.

Once a utility company or major manufacturer has purchased a natural gas contract for delivery, it must find a pipeline company to bring that gas to its own pipes and storage tanks.

Years ago, these pipeline companies played the role of wholesalers, buying and selling gas at a markup. Since deregulation, they've become more like interstate trucking companies, charging only for the cost of transportation. This cost varies depending on pipeline capacity. When demand jumps, pipelines deliver gas around the clock, raising the cost for last-minute, emergency deliveries.

Only four companies currently compete to deliver natural gas from the Henry Hub to the "city gate" — industry parlance for Con Ed and Keyspan's local pipeline systems. Of these four companies, one, Tulsa-based Williams Inc., is responsible for more than 50 percent of all natural gas delivered. If Williams were to lose one of its four feeder pipelines into the city because of a malfunction or terrorist attack, New Yorkers wouldn't go through anything as sudden or catastrophic as the August 14 blackout, but they would experience a sudden jump in energy prices.

While few worry about the overall long-term supply being in danger of depletion -- gas is a relatively abundant resource, and has a "large volume" of undiscovered reserves, according to the U.S. Department of Energy -- there is great concern about the current capacity of regional pipelines to bring enough gas to New York in order to meet the increasing local demand.

A number of new pipeline projects could boost the flow of natural gas into New York City. The 2002 State Energy Plan lists more than ten projects approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. "We're going to need more [system] capacity if we want more market growth," says Mike Scott, author of the State Energy Plan's chapter on natural gas infrastructure.

Karl Brack, spokesman for Columbia Gas Transmission, is more blunt: "There simply is not enough [pipeline] capacity to meet the needs of the region," says Brack, whose Virginia-based company is preparing to build a pipeline connecting downstate New York with a Canadian pipeline running under Lake Ontario.

When the gas crosses the "city gate," local distributors, such as Con Edison and Keyspan, add mercaptan, the chemical that gives gas that rotten egg smell. This is a safety measure; without such an additive natural gas is odorless and colorless so it would be impossible to detect a possibly deadly leak.

In New York City, the gas stays underground. It moves into local pipes called mains, running under streets and passing through emergency shutoff valves. One final branch, about an inch in diameter, brings the gas to the Queens Village home, where it may be used for heating and drying clothes, as well as cooking.

Although Con Edison and Keyspan divide the city in terms of service — Con Edison serving Manhattan, Bronx and portions of Queens, Keyspan serving the remainder — New York is one of the few states where residents have the ability to choose their local gas provider. In other words, outside companies can deliver gas via Keyspan's or Con Edison's local pipeline system just as telephone companies can deliver long distance service via Verizon's local telephone network. But, to date, this competition has played out more on paper than in reality.

THE MARKET

New York, once a laggard in natural gas demand, now accounts for six percent of nationwide natural gas consumption, compared with five percent for petroleum and one percent for coal, according to the New York State Energy Research and Development Association.

The increased demand has contributed to the upward drift in prices and the growing concern about local supply. New Yorkers already reeling from the August blackout could be in for a second shock this winter. If cold weather forces Con Edison and Keyspan to deplete their winter reserves, New Yorkers could see their winter energy bills spike even higher than they did three winters ago. Then, the utilities had to supplement their supplies and were forced to pay two to three times the normal wholesale rate. As always, the utilities passed the cost along to their customers, who wondered why their electric and gas bills had suddenly doubled.

To avoid yet another energy ambush, government agencies and utility companies are slowly getting the word out about the potential for higher bills this winter.

If we get a repeat of the warm 2001-2002 winter, energy prices should remain elevated but stable. If we get a repeat of last winter's cold weather, things could get ugly even for heating oil users. With natural gas now qualifying as the number one fuel for local power plants — 28 percent of all electricity used in the state comes from generators powered by natural gas, says the New York State Energy Research and Development Association — everyone is a natural gas user nowadays.

That's quite a change from the days when oil workers treated natural gas as garbage.