|

Hundreds turned out to celebrate last July as a portion of Church |

Update: On May 30, a sharply split City Council defeated an amendment that would have had the effect of renaming part of a Brooklyn street for Sonny Carson. For more, click here.

Millions of people in New York City walk, jog and stumble across streets named for the famous and the not so famous. New Yorkers can explore Columbus Avenue, jam on Bob Marley Boulevard, or be cool on Humphrey Bogart Place, but they can also stand and snicker at the corner of Seaman (named for a 17th-century landowning family) and Cumming (so dubbed in 1925 in honor of a now obscure local property owner).

Whether honoring celebrities or obscurities, street namings are generally quiet affairs with the City Council essentially rubber stamping the recommendations of the community boards. But the dispute over a four-block section of an avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant Brooklyn has renewed focus on the naming and renaming of city streets. On Wednesday, City Council will vote on a bill to rename 51 city streets in honor of various personages. The bill is controversial because of a name that is not in it - that of the late black activist Sonny Carson, hailed as a community hero by some and condemned as a bigot and criminal by others. A sharply divided council committee voted to delete Carson from the package last month. This debate follows another naming controversy - that one involving Corbin Place in Brooklyn, which got its name from Austin Corbin, a longtime Brooklyn developer and an anti Semite.

The council's predilection for devoting energy to street names most people will never use (Avenue of the Americas, for one) is often mocked as a waste of time, but in taking such action the council and by extension, the city has the power not only to bestow honors but also rewrite history. This raises the question of who gets to tell that history and determine who is a local hero - or a local villain. "Street names function as a barometer of social values at a given time, and as such have historical significance that goes beyond a name," wrote Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss, authors of Brooklyn by Name: How the Neighborhoods, Streets, Parks, Bridges and More Got Their Names.

THE POWER TO NAME

|

From Corbin, the anti-Semite, to Corbin, the Revolutionary War hero? |

As the City Council seeks to establish itself as a serious legislative body, its penchant for renaming streets has become an easy target. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, Councilmember James Oddo of Staten Island said the ceremonial gesture was a "luxury the city can no longer afford." Turning away from that task, he wrote at the time, "would symbolize a tangible step in redefining our role." In 2002, Oddo proposed a bill to take the council "out of the name changing game" by leaving the approval of the street renamings to community boards and allowing the council to override any ones it objects to.

The council did not go that far but rather than vote on all the name changes individually, since 2002,it has voted on street naming proposals in two package bills a year.

At the same time, the number of name changes has increased. In 1986, the parks committee evaluated just 25 proposals over the entire year. After 9/11 the number of street names began rising as the council started honoring rescue personnel and others who died in the attack. Last spring, for example, the City Council renamed 58 streets in the city, many for people who died in the terrorist attacks.

HOW IT'S DONE

|

|

Proposals for street renamings begin at the neighborhood level when local residents recommend a street name, usually in honor of a deceased neighborhood figure, to the local community board. Sometime they circulate petitions to demonstrate support.

The community board then approves or rejects the plan. Some community boards are reluctant to rename streets. When "Jerry Orbach Way" failed to pass Manhattan Community Board 5, Orbach's widow Elaine brought the proposal to neighboring Community Board 4, which approved the recommendation to rename the other corner of 53rd Street and 8th Avenue after the actor. Some community boards like to dole out the honors, as chairman of Manhattan Community Board 6's transportation committee Lou Seperky has noted: "There used to be a habit that we'd just name something after anyone who sneezed." Community Board 6 will likely recommend Kurt Vonnegut Way for the next package of street name bills.

Whether a struggle or a sneeze, if a community board votes to pass a street renaming proposal, the local council member then brings the recommendation to the Parks and Recreation Committee. If the committee affirms the proposal, the renaming is submitted to the council for a vote in one of the package bills. When and if the council votes yes, a new sign with the honorary name is erected next to the marker with the current, more mundane, label. (The original street names remain on all street maps.) So, for example, a new sign for Vonnegut Way would be added to the existing post overlooking the corner of 48th Street and Second Avenue where the writer used to walk his dog Flour.

THE CARSON CONTROVERSY

While Vonnegut has his detractors, a corner with his name is unlikely to spark the kind of furor that has surrounded the proposal for Sonny Carson Avenue. Since its introduction, the four-block stretch has been a constant topic of council meeting discussion, divided council members and prompted a lawsuit. And it has spurred Oddo to consider reintroducing his 2002 street renaming bill

Sometimes referred to as "The Mayor of Bed-Stuy," Sonny Abubadika Carson, a Korean War veteran, was involved in a variety of local causes in the local black community, such as the Republic of New Afrika, the African Burial Ground project, securing voting rights for ex-prisoners, the Black Men's Movement Against Crack and protests against police brutality. Additionally, his autobiography was turned into a movie The Education of Sonny Carson.

Recommended by the local community board and submitted for consideration by Councilmember Albert Vann, Carson would seem to be shoo in for an honorary street name. But Carson also had a record of criminal and racially motivated activities. In 1974, he served time in prison for kidnapping. He organized boycotts of Korean groceries where the protestors held up signs saying, "Don't Buy From Koreans" and "Don't Shop With People Who Don't Look Like Us." Carson said at the time, "In the future, there'll be funerals, not boycotts."

The activist made little secret of his attitudes. When asked about his anti-Semitic statements, for example, Carson replied, "I'm anti-white. Don't just limit me to a little group of people." And in a 1987 interview with the New York Times, Carson said, "You don't give us any justice, then there ain't going to be no peace. We're going to use whatever means necessary to make sure that everyone is disrupted in their normal life."

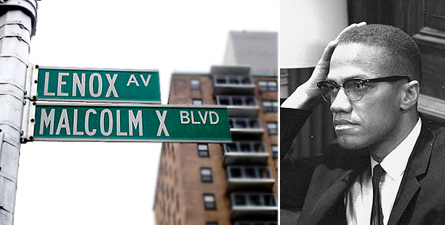

A stretch of Sixth Avenue north of 110th Street was renamed Lenox Avenue in 1887 after millionaire philanthropist and book collector James Lenox. In the late 1980s, the street got another name change to recognize Malcolm X.

But those backing the renaming say it is up to people in the community, in this case Bedford-Stuyvesant, to determine who they can honor. Explaining Carson's significance, Vann said, "He came into prominence at a time when the black community was asserting itself, defining itself, claiming itself and trying to make the community better for black people - he was a part of that struggle."

When it came time for the parks committee to vote, it split along racial lines with three white members -- Alan Gerson, Joseph Addabbo and Dennis Gallagher - voting to delete Carson's name. Chairwoman Helen Foster, who is black, voted against its removal, and another black member, Letitia James, abstained.

At a council meeting following that vote, Councilmember Charles Barron criticized the council for voting to "block the black community from self-determination of selecting our own heroes." He asked, "What could be more divisive, whether intentional or unintentional, than have four white members of this city council tell an entire black community no?"

Vann, who like Barron is black, also voiced concerns about the council setting a precedent for overriding local interests. "We can vote as a council against my district and against my community and against our self-determination," he said. Vann apparently takes a fairly broad view of that right. During a television appearance on NY1, he responded to a hypothetical inquiry about a German community wanting to name a street after Adolph Hitler. "I don't think they could withstand the pressure of doing that, ok? Do they have the right to offer that up? Yes, they do," Vann said. "If you could live with that identification, then I don't have a problem with the process."

Two members of the local Brooklyn community board sued the city council for removing Carson's name from consideration. Presiding Judge Leland DeGrasse rejected the claim, ruling that because the renaming of streets is a legislative matter rightfully under the purview of the city council.

AND WHAT ABOUT ALL THOSE OTHER STREETS?

During the heated debate, Barron said that, if the council failed to honor Carson, he would demand information on every person recommended for an honorary street name in the future. "We got street names of slave holders and racists all over Brooklyn," Barron reportedly said. Whether or not the council agrees with Barron's other comments, the frequency of streets named for slaveholders is indisputable.

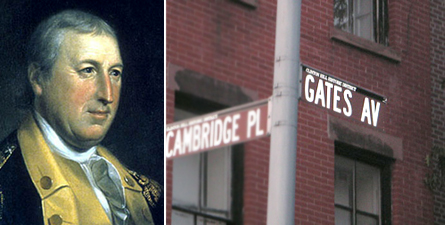

By one count, at least 70 New York City streets has slave owner names Takes Gates Avenue, the very name once slated to bear Carson's moniker. Its name honors Horatio Gates, a Revolutionary War general. For part of his adult life, Gates owned a Virginia plantation and slaves, although he freed them in 1790.

An influential historical figure and "founding father" of America, Thomas Jefferson is honored with a park and a high school (ironically in Barron's largely black). But as Barron pointed out at a recent council meeting, Jefferson could also be described as a slaveowner, rapist and pedophile. Foster added that Jefferson sold his own children into slavery.

Horatio Gates, a Revolutionary War general, whose name now graces what some would dub Sonny Carson Avenue, owned slaves who he eventually freed.

Of course, not only slaveowners are controversial. In 2003, the city renamed the corner of the Bowery and 2nd Street as "Joey Ramone Place," in memory of the Ramones singer. He got this honor despite having spent a number of years with a fairly major cocaine habit

The New York City Council has recognized the socialist and anti-imperialist activist and poet Pedro Pietri by renaming East Third Street between Avenues B and C in his honor. The council was apparently not alarmed that Pietri founded the Young Lords Party, which in the 1970s was often likened to the Black Panther Party

And Barron has criticized the council's accolades for the entertainer Al Jolson, who performed in blackface. New School Professor Joseph Ciolino, who has studied Jolson, has said the entertainer stood up for equality both on and off Broadway, and wore blackface for cosmetic effect. True or not, many New Yorkers still might not be amused.

And then there was the Bernard Kerik Correctional Center. In December 2001, while Kerik, a former city corrections commissioner, still served as police commission, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani agreed to rename the Manhattan House of Detention, popularly known as the Tombs, in Kerik's honor. Less than five years later, after Kerik had pleaded guilty to misdemeanor charges, had been accused of seamy --if not illegal conduct -- and was still the subject of sundry other investigations, Mayor Michael Bloomberg removed his name from the jail.

The names of anti-Semites grace several street signs as well. Take Corbin Place, for example. Austin Corbin, a onetime president of the Long Island Rail Road, was also a member of the American Society for the Suppression of Jews who once asked, "If this is a free country, why can't we be free of the Jews?" Today, a thriving Jewish community resides on the street named after him, which some rabbis consider to be the best revenge. Others disagree and want the city to rededicate the street to another famous Corbin: Margaret Corbin, a Revolutionary War heroine. This way, the council can revise history without forcing residents to change their addresses.

But another anti-Semite is likely to keep his streets. New Amsterdam Governor Peter Stuyvesant, who tried to get the first Jewish settlers in America, expelled has his name attached to a large avenue, an apartment complex, a post office, a high school and other New York fixtures.

STREETS THAT FAILED

If Carson does not get his street, he will have company. A 1986 proposal to rename a street in honor of Ben Gurion, the first president of Israel, failed when representatives of the American-Arab Relations Committee and the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee testified against the recommendation, citing considerations for Palestine's independence and safety.

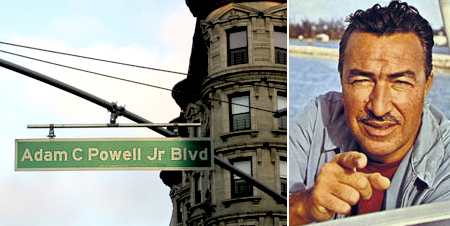

During his life, U.S. Representative Adam Clayton Powell attracted controversy but there was little opposition to putting his name on a portion of Seventh Avenue in his old congressional district.

Councilmember David Weprin withdrew a proposal to rename a street after assassinated Israeli tourism minister Rehavam Zeevi when he learned of Zeevi's hatred of Palestinians

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn has rejected efforts by activists to rename a Harlem street for Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has been on death row in Pennsylvania since being convicted of murdering a police officer in 1981. "Commemorative street renamings are generally awarded only posthumously. To the best of my knowledge, Mumia Abu Jamal is still alive, and is therefore not eligible to have a street renamed after him," she reportedly wrote one advocate.

Not bound by such considerations, in 2006, the Paris suburb of St. Denis France named one of its streets for Abu-Jamal. The U.S. Congress then passed a resolution asking the French government to remove the sign, thereby proving members of the New York City Council are not the only Americans to make a big deal of street names.

Â