Columbia University promises that its new campus in West Harlem will boast tree-lined blocks, new outdoor cafes and glass-walled buildings where arts and research will flourish. There's one problem, though, according to Klaus Jacob, a special research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University: It could all be underwater.

Under Jacob's worst case projections, more than half of the new campus could end up submerged by water if hit by the right storm.

Columbia's planners could have minimized the risk of damage, Jacob argues. Instead, they plan to build one large basement that connects the entire 17-acre campus, meaning that if one building floods, they all flood. Furthermore, he said, by locating the new campus' power plants underground, the school puts its energy source at risk.

The Columbia expansion is not the only large-scale project in New York in danger of flooding. With climate change promising more violent and frequent storms, much of the planned and existing development in the city could face severe floods,

Using a slide show he has developed - a kind of New York City centric "Inconvenient Truth" - Jacob is promoting the need to plan for the effects of climate change. While they may not have seen the presentation, many people are concerned. According to a survey released this week by Columbia and Yale Universities, 69 percent of New Yorkers believe "it is likely that parts of New York City will need to be abandoned due to rising sea levels over the next 50 years."

So how is the city preparing? Ron Shiffman, former city planning commissioner, has not seen much indication they are. "I think it's a big question mark," Shiffman said. "They say they're working on it, but I have yet to see anything."

Any decisions made in New York City about the best way to incorporate risks from climate change into land use plans would not be implemented until after Mayor Michael Bloomberg leaves office. That would be after the city has undertaken what Bloomberg has called "the most fundamental and geographically significant changes since the 1960s" -- and a redevelopment plan that, in the view of many, does not address the new reality of a wetter, warmer New York.

THE GROWING RISKS

With some 600 miles of waterfront, New York City is particularly vulnerable to storm surges and rising seas -- and to the effects of a warmer climate.

The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates temperatures will rise between four and thirteen degrees Fahrenheit in the next 90 years. Higher temperatures will increase the intensity and frequency of storms, lead to more rainfall during the winter due to less snow and create rising sea levels, all of which will make flooding more common and severe. Even under an optimistic scenario, the group predicts that the kind of flood the city now expects once every 100 years could occur an average of every 22 years by the turn of the century.

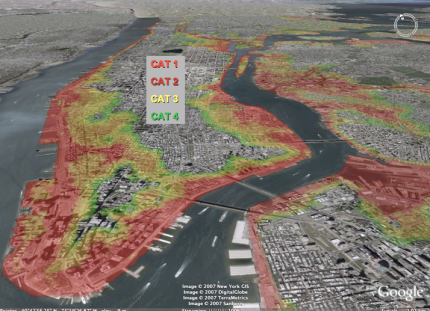

Over the next 80 years, sea levels around New York City could rise by 11.8 to 37.5 inches, according to calculations by the U.S. Global Change Research Program. As a result, "flooding by major storms would inundate many low-lying neighborhoods and shut down the metropolitan transportation system with much greater frequency," said a paper by the Columbia University Center for Climate Systems. Given this, the paper continued, many areas would face flooding from a Category 3 hurricane, including "the Rockaways, Coney Island, much of southern Brooklyn and Queens, portions of Long Island City, Astoria, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens, lower Manhattan, and eastern Staten Island from Great Kills Harbor north to the Verrazano Bridge."

The city's infrastructure could take a particularly heavy hit, according to Matthew Bowman, head of the Storm Surge Research Group at Stony Brook University. This, he has said, "includes subway entrances that are close to sea level, tunnels and their air and vent shafts, subway track and signal systems, bridge access roads, small bridges, airports, port freight-handling facilities, water pollution control plants and their tide-gate regulators, combined sewer outfalls, landfills, solid-waste transfer stations, pipelines, power plants, and buildings in areas with high property values and dense population."

Overall, Bowman figures, "In the future, a weaker storm will do the same damage that a severe storm does today."

How will this be experienced in different parts of the city?

Ground Zero

Storms could bring 10 foot-surges to lower Manhattan, affecting much of the new development planned in and around Ground Zero. The World Trade Center memorial could flood "unless they have special flood gates to seal it off," Vivien Gornitz, a special research scientist for NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies at Columbia University, told the Downtown Express.

The Lower Manhattan Development Corp. has dismissed the danger. "The designs would be resistant to those types of flooding dangers," a senior advisor, Victor Gallo, has said.

The structures in the trade center site will be set in a foundation popularly referred to as the bathtub. "This bathtub, with its memorial, with its museum and several other structures inside it and adjacent to it, could very well be flooded. Now, to pump out a whole bathtub with all those things - I think is not what we were looking forward to," Jacob told National Public Radio.

The transportation hub being built on Fulton Street also is vulnerable to flooding because of its low elevation, Jacob said.

Nearby neighborhoods, such as Greenwich Village and Little Italy, also are at very low elevations. Many buildings in these areas have masonry foundations, making them particularly vulnerable to damage, Joe Tortorella, a structural engineer and a member of the Disaster Preparedness Task Force of the American Institute of Architects, said in the Times.

In a severe storm, "if the water moves fast enough and recedes fast enough, there could be scouring like a tide that takes sand with it on the beach. As the water recedes, it pulls silt out and could undermine the building," Tortorella said. "It could be a disaster of epic proportions in New York for the smaller buildings."

Brooklyn Waterfront

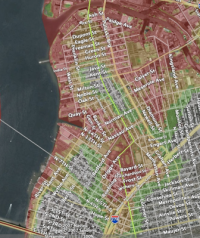

Areas of the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront slated for development -- which aim to bring tens of thousands of new residents -- are at risk of being flooded by a hurricane, according to the city's own maps. Sewers in Greenpoint already cannot deal with the rainwater from severe storms, such as those of last July and August.

Writing in the Brooklyn Paper, Tom Gilbert, a writer and historian who lives in the neighborhood, described driving on Morgan Avenue at the height of a major storm last July: "A river of water as high as my hubcaps roaring down the street and cascading over the sidewalk into basements, as panicked residents ran out of their houses."

Such a scene, he continued, reinforces "continuing doubts about how well the infrastructure of North Brooklyn is handling the building boom of the past five years and how well city and state government are managing this explosive growth."

Much of the new development "will occur along the East River waterfront, which is subject to flooding from storm surges. New construction will result in significant changes to the floodplain that may reduce its capacity for flood retention or alter stormwater flow characteristics," said Brooklyn Community Board One's Rezoning Task Force in comments on the draft of an Environmental Impact Statements on rezoning the area to accommodate more development.

For its part, the environmental impact statement generally says all new structures in the area should meet existing city and Federal Emergency Management Agency requirements. But it notes, "the proposed action would not involve any direct public funding for flood prevention or erosion control measures."

Queens

The changing climate threatens existing developments as well. The vast majority of damage resulting from this summer's flash floods were in Queens. After that storm, an underpass in Glendale was covered with 10 feet of water, raw sewage was forced up through people's toilets and sinks in Queens Village, and the tracks at Long Island Railroad's Bayside station were immersed.

Much of the area is on land that is low lying and getting even lower. Emily Lloyd, commissioner of the Department of Environmental Protection, has said that the water table in southeast Queens has risen 30 feet in 20 years, and now sits "just below the surface."

In March, the city created a Flood Mitigation Task Force to identify hotspots for flooding throughout the borough by March. Some progress has begun, and last month the Department of Environmental Protection announced a six-year effort to build a drainage pipe for Whitestone.

FACING THE PROBLEM

No matter what government, business and individual citizens do, a flash flood, is difficult to deal with. "All of the underground infrastructure basically becomes a drainage ditch," said Rae Zimmerman, professor of planning and public administration at New York University. But, she added, much more could be done to prevent these problems.

Task Forces and More Task Forces

Much of the planning to prepare for the effects of climate change will begin under the auspices of the myriad taskforces and advisory boards that are being formed as part of PlaNYC, the city's long term sustainability plan .

The administration is creating a multi-agency Climate Change Task Force to figure out how to protect the city's infrastructure. Most of that - including the subways, electricity and gas distribution systems and communications network - is underground.

The Department of Buildings is creating its own taskforce, and part of its goal is to develop amendments to the building codes to make buildings more storm resistant and inhabitable even without power.

Better Sewers

Perhaps the first problem the city needs to address is its sewers, which cannot cope with even normal amounts of rain. PlaNYC laid out a number of pilot studies for strategies to keep water out of the system in the first place. But after the subway flooding in August, the City Council took a more aggressive approach and passed legislation mandating a sustainable stormwater management plan by October. Another bill would mandate that capital projects paid for with a significant amount of city money retain, reuse and treat stormwater to keep it out of the sewers.

While experts support the new law, they consider it only a first step and are waiting for details to emerge. "The new law is definitely going to take the city in the right direction," says Larry Levine, a water expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council. "But just how quickly and effectively remains to be seen."

Housing

Providing temporary housing for a large, displaced population will take substantial planning. In beginning that effort, the city's Office of Emergency Management recently published the results of its design competition to create post-disaster housing.

The 10 winners of this competition all create homes that could be easily built and arranged to promote community. Each has been awarded $10,000 to further develop their projects, which will then be displayed again in May.

One would build homes on a series of barges attached to the mainland by threads that carry electrical cables and water and sewer lines. The barges would remain after reconstruction to provide parks and help restore a shoreline ecology decimated by centuries of industrialization. Another would use the debris from a disaster to create piers for new housing to be built upon.

Providing Insurance

Since 2004, 50,000 residents in the metropolitan area have had their homeowner's insurance policies canceled because of the risk of floods. Allstate, State Farm and Liberty Mutual now refuse to write new policies in the city because of the danger, according to the New York Times.

To help reduce rates in the city for flood insurance, which is issued by the federal government, PlaNYC wants the city to join a federal plan called the Community Rating System, which calls for lower insurance premiums in communities whose flood management plans exceed federal standards.

GRASSROOTS EFFORTS

Many experts believe that for any of these ideas to work, the public must play a key role. "Public support, or even public pressure" is needed to get city officials to confront the changing circumstances, said Susanne Moser, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who coauthored a report on this issue. "That means the public needs to know what to support, what to oppose .... It's important for citizens not to leave policy-making or policy-implementation only up to influential interests."

The city has started a pilot program to engage communities to help plan for the possible effects of climate change and to share their expertise about their neighborhood with officials. The first effort is in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, in partnership with UPROSE, a local Latino community group. The organization has held three planning discussions with a host of local residents with a goal of creating a climate change adaptation plan that reflects the community's thinking.

"We are looking at planning efforts, which may be different when you put the climate change lens on them," says Elizabeth Yeampierre, the group's executive director. "But we don't really know how the city is going to respond to this in the end. The problem is really the cost: What can or can't the city afford to do."

UPROSE hopes to have developed a plan by this spring.

WHAT OTHER CITIES ARE DOING

Although New York has begun confronting the effects of climate change, other governments in the nation are farther along in the process.

Kings County, Washington, which includes Seattle and its legendary rainfall, has made climate adaptation an integral part of its planning process. The county government's overall climate plan includes the Flood Control Zone District, an agency that builds and improves flood management infrastructure, buys back property at risk of flooding and limits new development that would contribute to flood risks.

King County Executive Ron Sims, the county's global warming team and the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington have written a roadmap for local, state and regional governments that wish to include climate adaptation in their planning.

"There are still many people who are reluctant to talk about specific adaptation or preparedness policies. But as responsible public leaders, we cannot afford the luxury of not preparing," Sims wrote in the introduction to the guide.

The map is being distributed through the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, which has started a new program called Climate Resilient Communities.

One of the earliest places to become a climate resilient community is Keene, New Hampshire, a city of about 23,000 people. Its Climate Adaptation Action Plan would identify areas with a 2 percent or greater chance of flooding every year and prevent future development in those areas.

It may come as no surprise that Keene is ahead of the curve. The city was ravaged by a storm of such intensity in 2005 -- one it is only expected to experience once every 500 years.

LOOKING FOR ANSWERS

Given that New York is an old and crowded city built on islands and along shorelines, experts agree there are no easy answers to protect its buildings and systems from flooding.

The subway and the sewers point out the complexity of the problem. Any water taken out of subways tunnels during a severe storm, such as last summer's, ends up in the sewer system, overtaxing that infrastructure. "You solve one problem and you create another," Madan Naik, chief structural engineer of New York City Transit, has said.

Others have envisioned barriers that will literally hold back the sea, such as those used in the Netherlands. In particular, some scientists have envisioned a system of three barriers that would operate together: one at the the Narrows at the mouth of New York Harbor between Staten Island and Brooklyn, another across the Upper East River and the third at the mouth of the Arthur Kill between New Jersey and Staten Island.

Jacob offers anther solution -- one that seems almost impossible to implement in a growing city of 8 million always searching for more space. He called for simply pulling back from low-lying, flood prone areas. "That," he has said, is the "price to be paid for pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere."

Â