The 2006 School Budget -- Reasons To Be Pessimistic

Almost every public school parent, student and teacher takes it as an article of faith that city schools do not have enough money. Teachers spend their own money to purchase supplies, parents buy paper towels for their child’s classroom and students regard crowded classrooms and shabby playgrounds as the norm. But, as angry as many New Yorkers may be about this, they – or at least their elected representatives – do not blame Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Or so it would seem from the recent council hearing on next year’s budget for the Department of Education.

Earlier this month, Schools Chancellor Joel Klein appeared before the council’s Education Committee to answer questions on the proposed $14 billion operating budget for the Department of Education. Probably the most remarkable thing about the session was how peaceful – even cordial – it was. And the muted response extends beyond council chambers. Parents have stored away their Save Our Schools (SOS) buttons, and this spring has seen no banner waving rallies in front of Tweed Courthouse or angry letter-writing campaigns.

Certainly the sharp rise in results on standardized test scores by city students – released just two days before the council hearing -- contribute to some of the optimism. Council members and others were undoubtedly cheered by an increase, however slight, in school funding. The mayor says he has boosted city spending for education by a total of $2.5 billion since he took office.

But the aura of good feeling in the council chamber could fade. As savvy parents, council members and educators know, the optimistic budgets of spring can look far different in autumn. Last year, for example, many students showed up at school in September to find scheduled classes eliminated because of budget cuts. The Department of Education restored the bulk of those programs but only after weeks of turmoil at many city high schools.

Even now, the budget features some unanswered questions and possible dangers. For example, some wonder how much of the increase in the operating budget money will actually go into classrooms. The budget also makes two assumptions that are, from the city’s viewpoint, wildly optimistic: It assumes the education department will get almost $2 billion for capital expenses from Albany and that teachers will agree to a contract giving them merely a modest salary increase.

THE BUDGET INCREASE

All told, the mayor sees the Department of Education operating budget increasing by about a billion next year. This comes down to about $910 for each of the system’s 1.1 million students.

The increases include:

--$15 million to help at-risk students;

--$2.8 million for gifted and talented programs;

--money for new small schools, some designed to replace larger failing schools

--$4.6 million for English language learners and $2.8 million for a translation unit to help families that do not speak English;

--$95.9 for special education

--$13.4 million school security

But much of the budget increase, the chancellor readily admits, will not show up in classrooms. Some will go to pay increased fuel costs and fringe benefit costs. While he would rather spend this money in the classroom Klein said, he had no choice: Students have to get to school somehow, and, once there, they cannot sit in unheated classroom.

Since Klein took over, many people, including some of the Democratic candidates for mayor, have criticized him for spending too much on consultants and on high priced bureaucrats (educrats in the jargon) with little education experience. But parent activists and even council members will be hard-pressed to determine just how much money goes for such items. As a recent council guide to the education budget notes, “The education budget is so large and so vague that it’s easy to hide serious flaws within it and hard to spot trouble when it arises.”

Class size can be a case in point. The mayor’s executive budget calls for adding $10 million to keep class size in lower grades at its current level – but it does not set a clear numerical target.

Smaller classes remain popular – many educators say that they are one of the few proven ways to boost students' performance – and expensive. But while advocates for them appear, for the moment at least, to have removed the issue from the budget talk, it is part of the mayoral campaign. Council Speaker Gifford Miller, for example, would spend $380 million – generated by keeping the income tax surcharge on the richest New Yorkers – to limit classes in the lower elementary grades to 17 students. Borough President C. Virginia Fields and Former Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer have also called for smaller class sizes. At the same time, advocates for smaller classes have launched a drive (in pdf format) to put a ballot measure calling for smaller class size before voters in November.

THE CAPITAL BUDGET

In its four-year capital plan for 2006 to 2009, the city hopes to spend $10.5 billion to create more than 50,000 additional places for students around the city, restructure 44 schools, modernize science and computer labs and provide athletic facilities, among other improvements. In light of the overcrowding at many schools and shabby and outdated facilities at many others, the plan holds obvious appeal.

But there’s a hitch. According to the mayor’s budget, $6.5 billion of that money will come from the state. The city’s estimate derives from the judge’s order in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity lawsuit on the funding of education in the city. In his decision, Judge Leland DeGrasse ruled that the city schools needed an additional $9 billion in capital funding for the next five years. But, Governor George Pataki has appealed the judge’s ruling and the state has not budgeted any money to comply with DeGrasse’s ruling.

Of the $2.6 billion in the 2006 executive capital plan presented in April, $1.8 billion is to come from the state – but the state budget adopted this spring did not include those funds, creating a possible $1.8 billion gap in the capital budget. “Should we vote yes on a budget with $1.8 billion that’s not there?” education committee chair Eva Moskowitz asked Klein during his appearance at the council. “Can we get it before October? I don’t know. I wouldn’t hold my breath.”

Klein responded that the capital budget was not “pie in the sky. It is a court mandate.” But, he conceded, it would be hard to fund the programs without the state money. Despite repeated questioning, he would not say what he would advise the mayor to do if (cynics would say when) the money does not materialize.

The Educational Priorities Panel, a private group that works to improve education in the city, advises caution. It notes that the administration says no projects will be delayed. But the group adds in a statement on its web site, “In the past, capital budget cuts and increases have not necessarily been a good predictor of how many new schools will actually be built.”

If the Department of Education eventually cancels or delays some projects for lack of funds then council members, particularly those whose districts are affected, would squawk. But for now, at least, legislative and executive branch can present a united front, looking to Albany to come through.

THE MISSING CONTRACTS

The other big question mark in the budget involves labor costs. New York’s 100,000 public school teachers have been working without a contract for two years, as has the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, which represents 5,500 principals, assistant principals and other administrators. The teacher's union, the United Federation of Teachers, has recently stepped up demands for an accord and criticized Mayor Michael Bloomberg for not using the city’s $3.3 billion city surplus to reach a settlement with the teachers. Bloomberg, on the other hand, argues the surplus is temporary at best. The administration also says it wants to use the contract to force major changes in other aspects of the teachers contract – scrapping many seniority rules, making it easier to fire teachers, giving principals more authority over who they hire and so on.

Klein said the budget envisions the teacher’s a contract similar to that reached with many other city workers. But the teachers – along with police and firefighters – have resisted this idea, arguing that the city must pay teachers more if it is to compete with suburban school districts and keep qualified teachers in the city.

POLITICAL GAMES

As it is every year, the 2006 budget discussions also provide council members an opportunity to lobby for items of particular concern to their constituents. Vincent Gentile decried overcrowding at Fort Hamilton High School in his district. Diana Reyna outlined deteriorating conditions at the 850 Grand Street Campus. “We are bursting at the seams,” she said.

And Simcha Felder, most of whose Orthodox Jewish constituents do not use the public schools, urged the city to raise money by selling parts of some little used school playgrounds for real estate development. “It’s a no brainer,” he said. Many might agree – but not in the sense Felder meant.

Such gripes and proposals are all part of the game, as Klein apparently has learned very well. As he rushed out to another meeting, Moskowitz asked him whether he had a “philosophical objection” to giving teachers an allowance to buy books and supplies. The program was cut from this year’s budget – and last year’s as well. “No,” Klein said, “I don’t have a philosophical objection. You always put it back anyway.”

Â

The Real School Security Problem

|

Some of New York City's public schools now house "sweep rooms" for students cutting class, "holding cells" in the basement, and dozens of police and security guards. Unnoticed by many, these new additions are part of an unprecedented expansion of the criminal justice system into the educational domain.

In doing this, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has received inspiration from his predecessor. He has adopted the same "broken windows" theory that shaped former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's approach to fighting crime in New York City neighborhoods. The theory holds that minor signs of disorder, such as a single broken window, send a signal that no one cares, creating an opening for more -- and more serious -- offenses. So, to prevent crime you fix the broken window.

Thus, the Impact Schools Initiative, which takes its name from another police department program, Operation Impact, that put more police officers into high crime areas. Impact Schools is a joint effort by the police department, the Department of Education, and the mayor's office. Launched in January 2004, it targets middle and high schools with high levels of reported crime, and employs aggressive policing strategies to reduce violence and disorder.

But in light of new data profiling the Impact Schools, one must ask, "Which came first -- broken windows or broken schools?"

Impact Schools have more economically disadvantaged students and more black students than other city schools. They also tend to be more overcrowded, and less well funded than schools throughout the city, according to new research (in pdf format) by the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy. These problems existed before the launch of the mayor's Impact Schools initiative; only time will tell if conditions are changing. Looking back, we have to ask ourselves whether these schools had already been crying out for special attention -- not in the form of cops, security cameras, and "sweep rooms", but teachers, books, and computer rooms.

The facts speak for themselves. According to Drum Major Institute, the current 22 Impact Schools are operating at 111 percent capacity -– making them five percent more crowded than the average New York City public high school and seven percent more overcrowded than schools the Department of Education describes as similar. The worst of the Impact Schools, Walton High School and Christopher Columbus High, both in the Bronx, were at more than 180 percent capacity in 2004.

The city spent an average of $1,482 less for each student at an Impact School than it did at the average city high school in 2003. Furthermore, while the city increased spending on direct services in high schools by $1,217 per student between 2002 and 2003, average spending on students at the 22 Impact Schools rose by only an average of $609.

More than six in ten students at the 22 Impact Schools serving the lowest income families are poor enough for a free lunch (a benefit available to families whose incomes are up to 130 percent of the poverty line). This compares with about five in ten at the average city high school. At the six poorest Impact Schools, more than eight out of ten students are eligible for free lunch. At Walton High School -- also among the most crowded of the Impact Schools -- that number reaches nine in ten.

Additionally, the Impact Schools have a higher percentage of students of color and significantly fewer white students than the average city high school. More than half of students at the Impact Schools are black, compared with 35 percent in the average city high school. And there is also a slightly greater proportion of Hispanic students in the Impact Schools. At the same time, Impact Schools have a substantially lower share of white students -- 4.6 percent, as opposed to 14.2 percent.

Finally, ninth and tenth graders at Impact Schools were far more likely than their counterparts elsewhere in the city to be over age for their grade. By the time they reach high school, these older students, many of whom have had a difficult time in school, require additional resources to improve their academic performance. Getting extra help is made all the more difficult when a school is packed to the rafters and stretched to the limit, as is the case in the 22 Impact Schools.

Mayor Bloomberg seems eager to point to numbers showing crime falling at the Impact Schools this year over last.

But a recent analysis by the National Crime Victimization Survey has shown that putting police officers in schools does not stem violence. In fact, the opposite seems true: Schools using security measures such as law enforcement agents and surveillance cameras were associated with increased reports of school violence and disorder, while schools relying on more participatory efforts to educate youth on school rules and appropriate conduct were associated with less reported school crime.

The city has chosen to respond to the headline-grabbing visible symptoms of school disorder rather than treating the root causes, a complex social and education problem. If the city took a more thoughtful look at the 22 Impact Schools it would find they have much more in common than high rates of crime. Addressing those problems, and bringing the chronically resource-poor and overburdened Impact Schools up to the level of the rest of city schools, could go a long way toward making those schools safer, better places of learning.

The question for New York City now is not whether we fix the broken windows, but how?

Rhee, a fellow of the Drum Major Institute for Public Policy, is executive director of the Prison Moratorium Project

Money, Class Size and Mayoral Politics

Having once told voters to judge him on his handling of education in the city, Mayor Michael Bloomberg reacted jubilantly to the news on May 18 that reading scores for the city’s fourth graders had risen sharply this year. Of the students taking the test in 2005, almost 60 percent met state standards, an increase of about 10 percent over last year.

But amid the good news, a stubborn fact remains: Kids in New York City still do far worse on this type of exam than students elsewhere in the state. Statewide, 70 percent of fourth graders meet the standards.

Many of those looking to close that discrepancy -- or “achievement gap” -- see two, sometimes related solutions: Give the city schools more money and use a lot of that money to decrease class size. Both issues have emerged as hot topics in this year’s mayoral race.

The Funding Issue

The fight for more state funding for city schools dates at least back to the Dinkins administration when the Campaign for Fiscal Equity filed suit, seeking more funding for city schools. Despite numerous court rulings in the city’s favor, New York City public schools have not yet seen any of the billions of extra dollars the court ruled they should receive -- and thanks to court appeals by Governor George Pataki they are not likely to any time soon.

Bloomberg has made his position on this issue clear. He supports the court ruling that city schools get billions more. But he does not want the city to pay a single additional cent.

The courts did not address the question of how much of any new funding would come from the state and how much from the city, declaring that such decisions belong with the legislative branch, not the judiciary. But, Bloomberg has argued, any increase at all in city education spending would require cuts in other areas that "would harm the very children this lawsuit is designed to help." Michael Cardoza, the Bloomberg administration's corporation counsel, has even said that the city would reject any additional state funds if it had to chip in part of the settlement. And the mayor's proposed budget for fiscal year 2006 does not assume any big influx of state funds for education or any major additional city expense to match it.

His opponents clearly see him as vulnerable on education in general, and this funding case in particular. But they are also attacking each other.

In April, Fernando Ferrer proposed a tax of about a half a cent on sales of an average share of stock. Ferrer anticipated this would raise about $1 billion –- or, he said, enough to cover the city’s share of any negotiated settlement between city, state and courts in the CFE case. It makes sense to require Wall Street to contribute to education, the former Bronx borough president said, because “they are the industry that benefits most in seeing that New York’s children are educated to the highest of standards.”

Even though a similar, and far larger, tax existed in New York City until 1981, virtually everybody criticized Ferrer's proposal. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, whose support would probably be needed for such a tax to be enacted, said the idea was dead. Bloomberg called it a ``job-killing'' plan, and Representative Anthony Weiner, also running for mayor, termed it ``a mind-bogglingly bad idea.''

For her part, C. Virginia Fields says it is far too soon to be talking about how much the city will pay. “We need to have a much more aggressive position taken by the mayor of this city with the governor and the state legislature,” she says. The mayor needs to show the “kind of passion” he has exhibited on the West Side stadium and push the governor to provide “what’s right for the children of New York City."

Council Speaker Gifford Miller has proposed an extension of a tax surcharge on those earning more than $500,000 a year.

Weiner’s plan to provide funding for city schools calls for a tax on millionaires and cuts in some of Bloomberg’s pet education programs, such as paid parent coordinators in every school and the Leadership Academy, which trains prospective school principals.

The Class Size Debate

If and when the city gets any additional money, many parents, teachers and others want it to go toward reducing the number of students in city classrooms, particularly in the elementary school grades.

Just how much emphasis to put on cutting class size has been a key part of the educational debate in the city.

Advocates, such as the organization Class Size Matters, believe that no other single improvement can do as much to boost achievement as cutting class size. According to Class Size Matters, average class size in kindergarten through third grade in New York City is 22, down from 25 several years ago. But the group says that a quarter of students in the early elementary grades remain in classes with more than 25 children. This compares with an average class size of 20 in New York State as a whole. Class sizes become progressively large as children advance through public school, with high school classes in the city typically 34 students.

Led by Miller, members of the City Council have proposed reducing the average class size to 17 in early elementary grades, 20 in grades four and five, and 23 in middle school. At a mayoral candidates forum on education, Miller said that smaller class size is one of the things “that we know works” in improving education.

The other Democratic candidates express similar beliefs.

“Smaller class sizes is part of my overall list of things that we need to address,“ Fields says, along with better pay for teachers, expanded high school vocational programs, identifying students with possible problems at an early age and increasing the number of guidance counselors.

Chiding the mayor for not making overcrowding and class size a priority, Ferrer said, “Smaller classes mean our kids can get the individual attention they needed and deserve…Smaller classes work”

Not surprisingly, the teachers union has supported effort to reduce class size. “Lowering class sizes is one of the most basic, foundational reforms we can do to improve student achievement,” UFT President Randi Weingarten, said at a rally earlier this month, adding that some of the money in the court case must go toward reducing class size rather than being “squandered.”

The Bloomberg administration does not seem to agree. A 2003 audit by State Comptroller Alan Hevesi found the city did not create the number of new classrooms it was supposed to, despite being given money for that purpose. The mayor’s proposed 2006 budget includes increases in funding -– particularly for the mayor’s cherished program to create more small schools -– but has no additional money to cut class size. And in its plan for a sound, basic education, given to the courts last summer, the city said it would focus on leadership training, secondary school reform, early childhood education and special education and instruction for non-English speakers. The plan does not mention class size as a priority.

The Department of Education denies it ignores class size. Stephen Morello, communications director for Schools Chancellor Joel Klein, told the Sun recently that the administration already had cut class size and that reducing it further “is a key part of the city's five-year capital plan and its strategy for spending the CFE operating funds.”

But advocates, remaining skeptical, want to force the city to deal with class size. Class Size Matters has launched a drive to put on the November ballot a measure calling for the city to spend at least 25 percent of any CFE money on bringing down class size in the city to a level comparable to that in the rest of the state.

In 2003, advocates collected more than 114,000 signatures in support of a ballot proposal on class size. But Bloomberg managed to quash the vote. Since the mayor has his own ideas for charter reform measures , he could well bump the class size question off the ballot again this year, regardless of how many signatures advocates collect.

Â

Teaching Fellows Make Their Mark

"How many lives did your last spreadsheet change?" asks an advertisement on the downtown R train, as it rumbles toward lower Manhattan, filled with briefcase-toting professionals on their morning commutes.

The advertisement is for the New York City Teaching Fellows program, which recruits soul-searching professionals and recent college graduates with liberal arts degrees to teach in New York City's public schools. The program is founded on the premise that energetic, committed and well-educated people -- even those without teaching experience or training in education -- can help fill the critical teacher shortage in the city's poorest and hardest-to-staff schools and, in doing so, help turn those schools around. The fellows commit to two years of teaching in the public schools, receive a full salary and benefits, and earn a masters degree in education.

Now approaching its fifth anniversary, the Teaching Fellows program can point to many success stories. In dozens of interviews over the past year, principals told us that fellows have invigorated their teaching staffs and brought great enthusiasm and energy to their schools. And, while teacher retention is still a problem, the percentage of fellows who return for a second year has steadily improved.

The Teaching Fellows program, which began in 2000 with just 313 fellows, has grown into a significant presence in New York City schools. There are now 6,100 former and current teaching fellows in over 1,079 of the city's 1,300 public schools. That means that one in 15 of the city's 80,000 teachers is a Teaching Fellow. In 2004, fellows accounted for a quarter of all new hires in New York City public schools and a staggering half of all new hires in math and special education.

The program seems to have been most successful in the new small schools and in schools in which competent new administrators are seeking to improve student performance and staff morale. Even in high-poverty neighborhoods, there are effective schools in which fellows say they feel their hard work makes a difference in children's lives and where the fellows get guidance and support from their colleagues and supervisors.

Sadly, however, the program has not been uniformly successful. Fellows in poorly run schools with weak leadership tell us that they are set adrift in chaotic environments where no one helps them cope with students who have serious social and academic problems. Fellows in these dysfunctional schools say they feel completely isolated and so are more likely to quit. Even the most idealistic and hardest-working teachers cannot turn a school around without the help of a competent administration.

What Works

Many principals actively seek out teaching fellows because they have a reputation for being smart, energetic, and eager -- even if they have little formal training as a teacher.

"I've had nothing but wonderful experiences with them," says Ron Smolkin, principal of Independence High School in Manhattan, which opened in September 2003, and where six of the 30 teachers are fellows. "They are extremely bright, they want to save the world, and they grasp at every suggestion I make."

Administrators and fellows agree that the program has brought ambitious, motivated and talented people, who might otherwise never have considered teaching, into the public schools. " Many fellows say that the program offers a way to become involved in the public schools without spending several years -- and thousands of dollars -- to go to graduate school. "I know that I would not be teaching unless it were for the fellows," says a fellow now in his second year teaching 10th grade math and science in Brooklyn. " I've been lucky with being placed at a school with a good administration and lots of fellow fellows who I now call friends. The fellows are the best teachers at my school… [and] we are a great support network for one another. "

(Like many fellows interviewed for this article, this fellow asked to remain anonymous. As employees of the Department of Education, they are instructed not to speak with the press.)

Dozens of administrators credit the fellows with helping to change the culture and quality of instruction in their buildings. As a result, many fellows say they feel they are making a difference, not just in the lives of individual students, but in the quality and atmosphere of their schools as a whole.

What Doesn't Work

Fellows spend about seven weeks training and student teaching during the summer before they start as regular classroom teachers, but many say that summer school is not an accurate indicator of what they face in the classroom. The fellows program also matches all the teachers with mentors who visit their classroom about a dozen times during the school year. And the fellows take graduate courses in education. But, in general, the fellows are largely on their own.

As a result, their main association is not with the fellow program but with the school in which they teach. " I don't think of myself as a Teaching Fellow, except when I think about the fact that I was so poorly prepared to be a teacher," says Michelle Heller, a second year fellow at Discovery High School in the Bronx. " I identify myself as a teacher at Discovery High School. We have a strong, unified staff and take a lot of pride and ownership in our school."

Unfortunately, many schools that have the greatest need for fellows also have the weakest administrators and so provide the fewest opportunities for brand new teachers to learn their craft.

A third year teacher at a Brooklyn middle school, who entered teaching though the fellows program, says she bases her teaching largely on what she can remember from her own years as a middle school student. In her three years teaching in New York City public schools, she has not had a single opportunity to observe another classroom teacher, either within her school or outside of it.

"As a fellow, my number one support was another fellow who was one year ahead of me. He was my lifeline in the school, not because he has more experience, but because I can bounce ideas off him,” she said.

Some fellows in similar situations say that these pressures can overwhelm a brand new teacher. A former teaching fellow at a Manhattan high school, who quit during her second year, says that she entered the fellows program wanting to teach as a career, but is now seriously reconsidering that. " I am re-evaluating teaching as a profession because my experience was so miserable," she says. "What made teaching particularly difficult for me was the administration and the one-and-a-half hour math classes where the kids did not know how to add or subtract and I was trying to teach them algebra."

Vicki Bernstein, head of the Teaching Fellows program at the Department of Education, acknowledges that sending inexperienced teachers into the city's most difficult schools "would not be the optimal way to bring people into the teaching profession." But, she says, "That's where the need is."

Culture Clashes

Some principals complain that fellows, never having led a class before, often struggle with classroom management. And while some fellows wind up being excellent teachers, others are just not cut out for the job. Seasoned teachers and principals sometimes resent the fellows who they see as starry-eyed and naĂŻve outsiders. In many schools this is amplified by the fact that, despite efforts to recruit minority fellows, most teaching fellows are white, and the communities and schools they teach in are mostly black and Hispanic. Of the fellows who entered in 2004, roughly 58 percent are white, 19 percent are African American, 13 percent are Latino and 5 percent are Asian.

"I go to hiring halls full of fellows and it's overwhelmingly a white crowd," says Brian Leavy Devale, principal of PS 257 in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where 99 percent of the students are black or Latino. He says the fellows he has hired are excellent teachers and predicts that at least one will go on to be a principal or superintendent one day.

But, despite that, Devale prefers to hire people from the community so that the kids can have role models from similar backgrounds. "I'm all about keeping it open to people who have a vested interest in making it a better community, not just blowing in to try it out," says Devale. "It's a community school and I want to keep it that way."

"I've met some fellows who are going to go back after two years and write a book about 'my time in the urban jungle,'" he says. "Don't come in here to do a social experiment. It's a slap in the face."

Keeping the Fellows

Across the United States, public schools lose teachers faster than they can recruit them. During the 1990s, there was a steady rise in the number of new teachers entering the nation's public schools, but the number of teachers leaving rose even faster, according to "No Dream Denied," a January 2003 report by the National Commission on Teaching and America's Future. For example, in 1999-2000, U.S. public schools hired 232,000 teachers who had not taught the year before. The next year, more than 287,000 teachers left the public schools, resulting in net loss of 24 percent. "It is as if we were pouring teachers into a bucket with a fist-sized hole in the bottom," the report said.

The fellows program aims to train and retain educators for New York City. Because it is only five years old, it is difficult to know whether teachers who enter the city's schools through the fellows program are here to stay. But, so far, the retention rate for fellows has improved each year.

This year, 88 percent of fellows returned for a second year, compared to 80 percent in the first group. This is particularly encouraging when compared to the national retention rate for new teachers. Only 86 percent of new teachers nationwide return for a second year of teaching, according to the National Commission on Teaching and America's Future.

Bernstein attributes the improved improving retention rate to a rigorous selection process. Plus, she says, the program works hard to prepare fellows for the reality of teaching in the public schools. "People are going into challenging environments and we are doing a better job of giving them realistic expectations," says Bernstein. "At first, many hoped and thought they could make a difference instantly."

Room for Improvement

Many fellows say the program could be improved if, during their first year, they taught fewer classes and had more opportunities to observe senior teachers or receive professional development. Plus, fellows say that the program could better prepare and support the fellows with more intensive mentoring and with classes tailored to the realities of teaching in New York City public schools. Still, many say that it is difficult to imagine how they could have really been prepared for their first year in the classroom.

"The courses we took before we started teaching were helpless because nothing can prepare you for this," says a fellow in her second year as a special education teacher at a large middle school in Brooklyn. "I look back and can't believe I actually survived. But even on my worst day, I think 'Wow, I'm so lucky.’ I really am grateful. I got to jump right into teaching, and I get my masters. It's trial by fire. And I feel if I can do it here, I can do it anywhere."

This topic page has been adapted from articles that originally appeared on Insideschools.org, an independent guide to New York City public schools sponsored by Advocates for Children.

High School Students

New York City is restructuring its high schools. Some 42 new high schools were created last year, another 55 this year, and 45 more will be opened next year. Eventually, the plan is to replace all the large high schools with smaller schools, where the staff and the students will know one another better, and, so the thinking goes, the students will be encouraged to achieve more educationally.

What are the new schools like now, and how are they different from the other public schools? We can look at some answers using data from recently released “school report cards” for New York City combined with the most recent data on private high schools in New York City.

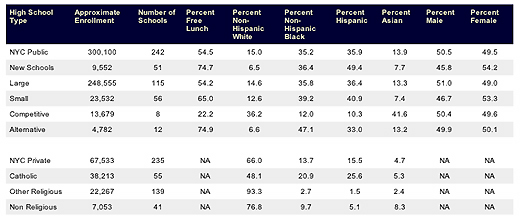

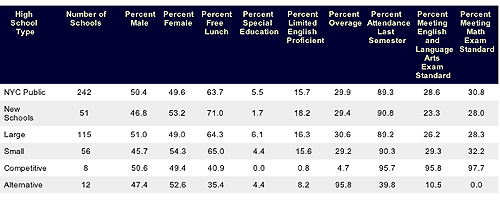

As the first table below shows, most New York City high school students are racial or ethnic minorities, but various high school categories draw very different mixes of students.

The average private school clearly serves a very different ethnic and racial clientele than the average public school. Overall, only 15 percent of New York City’s public high school students are white; by contrast, 66 percent of the private school students are.

It is important to keep in mind that 85 percent of all New York City students of high school age attend public high schools education as opposed to private ones.

So far, the transformation of New York City public schools does not seem to have affected the demographic composition of the various types of schools.

(To explain the definitions: The “new” high schools include those which were set up during the last several years, where often several schools share one building. The “large” high schools include the traditional local high school, as well as the vocational high schools. The “small” schools were established during earlier attempts to create small schools beginning in 1992. For this analysis, I am considering eight high schools as competitive; these include the traditionally competitive Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, Brooklyn Tech, and LaGuardia, the three new competitive high schools set up at Lehman, York and City College) and Townsend Harris in Queens, where it is difficult to gain admission. Alternative schools often serve students who are having problems in conventional educational settings.)

Among these different categories of public high schools, the ones that differ most markedly from the others are the competitive schools and the alternative schools. The competitive schools have a higher proportion of white and Asian students, a higher proportion of males, and a lower proportion of students on free or reduced lunch. The alternative schools on the other hand have a much lower proportion of white students and a higher proportion of students on free or reduced lunch (which is an indication of coming from a poverty-stricken household.)

The “new” high schools, on the other hand, seem to be drawing students roughly representative of all the public schools, as are the older “small” high schools, though the proportion of non-Hispanic whites is somewhat lower.

As for the ability of the students to meet the English and math standards – the new scores are not in yet. (The chart above shows the percentage meeting math and English standards of students newly admitted to the new schools. All that is clear is that some new schools seem to be aimed at low performing students.)

Whether the massive reorganization will improve educational outcomes for the vast bulk of New York City’s public high school remains to be seen.

Note on Sources

I am indebted to Lori Mei, Senior Instructional Manager, Assessment and Accountability, NYC Department of Education for supplying the data base used. The private school data were drawn from the Private School Universe Survey carried out by the National Center for Education Statistics of the US Department of Education. I also must acknowledge Jennifer Booher-Jennings of Columbia University for help with some of the school classification and in interpreting the results.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.Â

The Mayoral Candidates on Education

|

The mayoral candidates discussed education at an April 14 forum at St. Francis College in Brooklyn sponsored by the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, the union that represents principals and other administrators. Participating were Democratic candidates Fernando Ferrer, the former Bronx borough president; Manhattan Borough President C. Virginia Fields; City Council Speaker Gifford Miller and U.S. Representative Anthony Weiner, who arrived late because of a vote in Congress. Republican candidates Thomas Ognibene, the former City Council Republican leader, and Steve Shaw, an investment banker, also participated.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg was invited but, according to the forum's organizers, could not attend and asked to send a representative. The organizers rejected this idea.

Dominic Carter of NY1 and Brian Lehrer of WNYC moderated the discussion.

This is an edited transcript.

- Grading the Mayor

- Involving Parents

- Chancellor Klein's Performance

- The Role of Principals

- Furor at P.S. 34

- How Much Mayoral Control?

- Politics and Priorities Day Care

- Pre-K

- State of the System

GRADING THE MAYOR

Question: Mayoral control of the school system is something that many mayors sought and Mayor Bloomberg finally won from the state legislature. He says that voters should hold him accountable for education above all else. So, what grade would you give him on education from A to F? And if you think you can do better, please be specific as to how.

Gifford Miller: Education is the most important issue we're facing as a city. It's not just critical to our city for preserving our tax base; it's our moral responsibility to make sure that our children have a chance at a better life. I think we have a unique opportunity right now because of mayoral control, which is the best thing this mayor has done, but unfortunately he squandered that control.

If we were to use that control to focus on the fundamentals, on the things that we know work in education, we have an opportunity to move our schools forward. It's not as confusing or as difficult as this mayor suggests. We know what works: smaller class sizes, more quality teachers and principals, safer schools and stronger after-school programs. I'm afraid this mayor has chosen to focus on almost everything but those fundamentals and the results aren't good. Test scores are off, attendance is down, teachers are leaving the system in droves, violence is an increasing problem in our schools, and parents feel more disconnected than ever.

So I have to say that he's failed in his responsibility and a failure in responsibility is an F.

Thomas Ognibene: I would give the mayor an A for attempting to change education, but probably a D for implementation. I think he was well intentioned when he took control of the school system because it needed political control. But the problem was that instead of using his greatest assets -- the administrators, the principals, and the teachers -- to make sure there was quality education in the schools, he decided to centralize the school system again and run the school system from the Tweed building. Instead of allowing teachers, administrators, and principals to use their discretion and creativity to teach the children in the classrooms, they've mandated that education must take place at a certain pace and according to a certain schedule. That schedule isn't necessarily what the children need in order to learn.

If you're telling an administrator or a teacher that they have to teach a certain subject from 10:00 to 10:15 and they have to stop, even though the children are showing an interest in the subject matter and they want to learn more, you're going to lose the interest of the child. Eventually they're going to be turned off of education.

There are many things that [[Bloomberg]] could have done to make education better. One is that he could have evaluated the children, made sure that they were all tested so that they could learn at a pace that was suitable to them to acquire the educational skills that they need. He started a social promotion program. I think that was well intentioned, but the problem is that you may have children that can't acquire those skills by the third grade; they may need to go to the fourth grade or the fifth grade before they can acquire those skills. That's why you have to test them, you have to be much more flexible.

I want to stress: an A for trying, a C for implementation.

C. Virginia Fields: I would approach it similarly in that I would give the mayor an A for gaining control for of the school system because I do support mayoral control, but I would give a D for implementation. I think the mayor has missed opportunities in terms of doing the real work where it is needed.

Instead of focusing one of his major first initiatives on elimination of social promotion, I believe the mayor should have invested in the early childhood area, making sure that we are doing early assessment, making sure that we are making the interventions at the early level and monitoring those children, making sure they are receiving eye exams, ear exams so that, if they have problems with seeing or hearing, we don't have to wait until they reach the third grade to fail them. So he had a real opportunity to make some real investments in the interests of helping children move forward and he literally failed to do that.

I also think that he has been very dismissive of principals and other administrators in terms of involving principals and those who have the responsibility and should have the responsibilities of running our school. And that has affected morale, it has affected relationships, and it has a direct impact on the learning that takes place in the schools. So there have been real opportunities here to make some changes other than just reorganization after accepting mayoral control. We have a long ways to go and that's why I'm running because I would govern very differently in all of those areas.

Fernando Ferrer: It's one thing to gain control of our New York City school system, it's quite another to take responsibility for the 1.1 million children who parents send to our schools. The mayor gets high grades for taking control, the lowest possible grade for taking responsibility.

We essentially have two different visions about where our school system should be and where it should go. The mayor believes that it's sufficient to move around boxes on a table of organization, to build up the bureaucracy of the Tweed courthouse, to regulate the amount of minutes that educators may educate, and to bury educational leaders in mountains of reports and emails.

I view life differently. I believe that the magic either happens or doesn't happen in the classroom and that's the base upon which we must build. Creating excellent classroom environments with consistent, not uniform, curricula, with great teaching and learning in safe and secure and uncrowded environments, with after-school programs and giving troubled kids another alternative to their school buildings and giving struggling kids more time on tests.

I believe this mayor has succeeded brilliantly in gaining control, for that I give him an A. For vision and performance, for delivering on the promise of improving education, he's been an abysmal failure.

Steve Shaw: In terms of how I would grade Mayor Bloomberg, I would give him a C. He has made a strong effort, but in terms of what he's actually done, that's how we get down to the C.

But rather than focus on his failures, I want to focus specifically on what I would do differently and there are three specific areas. The first is governance, the next is curriculum, and the third is parental involvement.

With regard to governance, if you look at what happened, Mayor Bloomberg has put into place a rubber stamp type of advisory panel, which really doesn't engage the true stakeholders, the principals, the teachers, the parents. What I would do is have a panel, which would include the mayor, the chancellor, someone from the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, someone from the United Federation of Teachers and five parental representatives from all five boroughs.

The next is with regard to curriculum. Rather than focus on what Mayor Bloomberg has, which are reading programs which have lost federal funding for reading, what I would focus on is strong dose of phonics. What I would seek to do is to end bilingual education because I believe English immersion is what works. And I would seek to actively engage teachers, parents, and principals in any reforms that were made. Reforms don't get made from the top-down; they get made from the bottom-up.

And with parental involvement, I don't think the solution was to create another layer of bureaucracy I believe the way that you increase parental involvement is by doing things like eliminating school busing, which makes it very difficult for parents who want their kids to be in a neighborhood school to actually get involved in those schools. Those three areas are three specific things that I would do much differently than Mayor Bloomberg.

INVOLVING PARENTS

Question: Recently some parents groups expressed their disinterest in taking positions on the community district education councils because of the perception that these councils have been given no real power by the current mayor. In addition, the Panel for Educational Policy, which replaced the Board of Education, appears to many to be a rubber stamp of the mayor without the raucous, public involvement of times past. So, as mayor, how would you address the concerns of the public and specifically the interests of parents as stakeholders?

Virginia Fields: One of the key elements in terms of making our schools work is parental involvement. Over the years, I have been very actively involved in sponsoring parental conferences. Every year in those conferences, in terms of attendance it's grown so I know the value of that.

I would reach out in terms of strengthening the roles of the parent councils at the local level, making sure that they have the appropriate resources, the training and access to the decision-making as part of the work that they are asked to do. I would also ensure that the [Panel on Educational Policy] is able to function. They are indeed a rubber stamp, and it is regrettable because the level of people we have on that council include some parents but also educators. They simply are not asked or included in decision-making.

So, I would strengthen the role of each one of these entities to ensure that their voices are heard, that I listen to them and make sure that they too interact with parents. Setting the right climate, setting the right tone, so that parents know that they are not excluded and that their voices are also going to be listened to.

So it is a process of governance for me. Making sure that the appropriate voices are heard, with respect to parents, strengthening the structure that is in existence to create those kinds of engagements and as the mayor indicating and making it known that this is what I want to see happen.

Fernando Ferrer: It should surprise no one that parents are voting with their feet against this model of school governance. In droves not showing up for parents councils because they know what everybody else knows: The belief from City Hall and the Tweed Courthouse is they have no role in the education of their kids, no role in the governing of their schools. That's fundamentally wrong.

But the problem is magnified by the fact that we have the Panel for Educational Policy that is not only toothless, it barely has gums. When you see them walk down the center aisle of any school auditorium getting ready for their meeting, you see them walk in single file. The agenda has already been predetermined, confirming my worst fear of a board that does not legitimately decide out in the open important matters of public policy and budget making, where parents, community and city leaders can and should have an opportunity to get at it, to effect decision making and to effect a choice.

That's the biggest failure of this school governance plan. It has excluded parents. It's made decision in back rooms. and it really has forgotten what it's there for, making magic in the classrooms, bringing parents into the process and creating viable and sustainable communities of learners in every one of our schools.

Gifford Miller: First of all, parental involvement in a child's education is the most important variable in that child's educational success. And so we have to build a school system in which parents are welcomed, parents are embraced, and parents are given positive opportunities to affect their child's education.

My colleague here have talked a bunch about the Panel for Educational Policy, the education councils and the failure of this administration to embrace any kind of involvement of not just parents but anybody's opinion is not welcome at Tweed. Certainly as mayor I would strengthen both of those entities but more importantly I would focus on making sure that parents are involved in their child's classrooms, in their child's day-to-day learning.

One tremendously successful program that I've supported in the City Council is the HIP program. This is an Internet based program to allow teachers to communicate directly with parents. By just typing in a few keys they can reach all the parents in their class. What's interesting about this program is that it reaches not just parents who have Internet access but also gives parents who don't have Internet access an 800 number so that they can call in from any phone and receive a message from the teacher. This gives teachers a real opportunity to say, "Why was it that this child wasn't in class today? Here's the homework assignment. Here's something that we should be working on."

It meaningfully involves parents in the day-to-day education of their kids, and that where our focus should be. That's where any mayor's focus should be because that's where we make real change in the classroom that makes a difference to children.

Thomas Ognibene: Parents aren't involved because they've been deliberately excluded. But it's not just parents that have been deliberately excluded. Administrators, principals, and teachers have virtually been excluded from education because this mayor and his Department of Education choose to direct education from the Tweed building. If you want involved parents, you have to return education to where it belongs -- to each individual school. The principal is the lead educator, and the principal should decide policy in that school with the advice and understanding and consent of the teachers in that school.

When you return education to the school level, parents will become involved because the parents and their input are important to principals, administrators and teachers. And that's how you get the parents involved. Children will not learn if their sole point of education is in the school system. Children have to do homework. Their parents have to be involved.

Learning is a 24-hour event. I know this from my own family where my mother was a principal. If you stress education at home, the children will learn to love education, be proud of it and will hold the schools in reverence, and their teachers in reverence, and learn. If you exclude parents from the school system, the children are not going to learn.

We have to change the form of governance that we have and go back to a system where the Department of Education is minimized and the responsibility for education is with those who understand education: principals, administrators, and teachers. They deal with the children every day. They know what the children need. They can deal with the parents on a one-to-one level and really enhance the quality of education for children.

Steve Shaw: I think one of the first things we have to realize when we're talking about parental involvement is that there are a wide variety of parents out there. Many of the parents have the capability of getting involved in their kid's education, but many do not. And that's why I think adult education is a very important part of getting parents involved -- to make sure that parents know English, to make sure they know how to write and they know how to read. Under Mayor Bloomberg you would practically need a bloodhound to find an adult ed program. That would be different under my administration.

As I mentioned before, I would greatly restructure the educational advisory panel where five parental representatives would be on that panel. They would be elected by the general public. The elections would take place every two years. One person would represent every borough. I think that would be another way to engage the parents.

And the next thing is with regard to zoning. Now kids are zoned to go to a particular school. But what will happen is that all the kids with the really involved parents will try to go to one school. I used to live in Park Slope in Brooklyn, and everybody had to go to PS 321 because that was the very well-known school. And so what happens is that you have all the involved parents in one school and then you have a dearth of involved parents at the other schools.

What I think we need to have is strict enforcement of the zoning so that we have a wide variety of schools that have strong parental involvement from a wide variety of parents. Adult education, changing the panel and how it's constructed and changing the zoning, I think those are three things that will get the parents engaged in our schools.

CHANCELLOR KLEIN'S PERFORMANCE

Question: [[NORMNAL]]Now that the chancellor is selected directly by the mayor, what is your view of the proper relationship between the mayor and the chancellor? What criteria would you use to choose your chancellor? Would you remove Joel Klein?

Thomas Ognibene: I don't know if I have enough information to make a value judgment about Mr. Klein, but from what I can tell so far is he isn't running education the way I think education should be run.

My idea of the chancellor is someone who is steeped in the education process of the City of New York, someone who would come out of the New York City schools system, the kind of person who has taught in our schools, the kind of person who has been an administrator in our schools, the kind of person who's been a principal in our schools. They're the only ones who understand what is going on in our schools, what the teachers need, what the principals and administrators need to run the schools. You can't bring in a lawyer from Washington D.C. and give him a mandate.

[Klein] doesn't understand what our children need in order to be educated. He doesn't understand what teachers need and principals need to make a creative environment for the kids in their school. So if you bring in somebody without that educational history in New York, it simply isn't going to work.

We have to look for somebody who is an educator who is steeped in the traditions of New York City to be our next chancellor. So, yes, if I had the opportunity and I were mayor, Mr. Klein would be replaced by somebody who would be picked by a panel of educators, principals, administrators and teachers who would then interview and pick somebody who was a principal or administrator in our school system.

Question: But Mr. Klein did attend the New York City public school system.

Thomas Ognibene: He moved on to become a lawyer. He's distanced himself for many years from the needs of our schools and our system of education. It has to be someone who currently understands.

Steve Shaw: Yes, I would remove Joe Klein as schools chancellor. I believe one of the things he did which was absolutely inappropriate was ,when he fired the 45 principals, he released those names to the public. There needs to be a huge amount of respect between the administration and the principals and the teachers. If someone has to get fired, that's an unfortunate event and it can't be done as some sort of publicity stunt. The way he treats principals and teachers has been unacceptable and as a result I would not select him for my administration.

In terms of other reasons, I believe the type of top-down command of control system that he's put in place is inappropriate.

In terms of the type of person that I would look for I think it would be much like what Tom said. I don't think it's necessarily correct to say that just because someone is a lawyer doesn't mean he can't do a good job, but I think it's imperative that someone has a significant involvement in education in one form or another.

Virginia Fields: I certainly would not continue with Chancellor Klein. I do believe it is important to have an educator leading the largest urban public school system in the country - one who is steeped in terms of reform, making a difference, having come up through the system. And I know here in New York City we have so many who can fit that bill and I'm looking at a few of them now

I was very opposed to having to do a waiver [of professional education experience] for this chancellor at a time when we are looking to make the most major reforms. And when we look at others who have been brought into the system, they are of similar background. That has led to the disconnect, the disrespect, the lack of support, the lack of engagement, the lack of inclusion, the lack of following a system that would allow all of us, including elected officials, to be involved.

It has slowed down reforms that could have taken place for the past three years and it is unacceptable for the mayor of the chancellor to simply say it takes so much time. We know things take time, but they have been dismissive of educators and that is unacceptable.

So I would not continue with him and I would put in place, as I said, an educator and would look within the system because I think people who have been a part of the system start at a position much different than bringing in others from the outside.

Fernando Ferrer: This is April, and I hope you'll excuse me if I believe that, before one vote has even been cast in the primary or the general election, we shouldn't start hiring and firing high-ranking city officials at any debate.

But let me tell you what kind of chancellor of schools Mayor Ferrer would appoint. One who is, first and foremost, an educator. One who understands not merely what an organization is but what has to go on in the classroom and how to make that happen. Who has an appreciation for the fact that one-size-fits-all, cookie-cutter curriculum approaches don't work in a city as diverse and complex as New York City. Who values the input and the contribution of every educator and every parent. Who honors the voices of children but who, above all, shares my vision that magic should happen in every classroom in this city. And to make that magic happen, the chancellor has to be not a flunkie of any elected official. A chancellor has to be a champion for children, a champion of their parents and a champion of education in this city.

Question: Are you describing Mr. Klein as a quote "flunkie of the mayor?"

Fernando Ferrer: I know you need a story for 6 o'clock tonight, but that's not it.

Gifford Miller: Let me just say this, I am a huge fan of mayoral control, and I think the best thing that this mayor did was to get control of our school system because it creates the opportunity for real change, for really moving our schools forward. It puts, finally, the days of finger pointing and blame shifting behind us.

We now have not only the right, but also the responsibility, to hold the mayor and this chancellor accountable for the results of the last three and a half years. And, as I said earlier, the results of the last three and a half years have been very poor for our city's kids. Test scores are off. Attendance is down. Teachers are leaving the system in droves. Violence is an increasing problem. Parents feel more disconnected than ever.

So absolutely, I would replace this chancellor because he's the person who's been putting into place the wrong kinds of programs and the wrong sort of focus that is leading to these bad results. And I would choose a chancellor, certainly one with tremendous educational experience, an educator, someone with management experience. Someone who along with his or her top leadership represents the diversity of this entire city and somebody who's going to focus on the fundamentals that we know work in education, and that is the best possible teachers and principals in every school and classroom in the city. Instead of running them down, we have to build them up. Smaller classes sizes. Safer schools. And stronger after-school programs.

Question: Do you care that the current chancellor is a lawyer and had to get a waiver?

Gifford Miller: Just because the chancellor is a lawyer doesn't mean he wasn't going to succeed. In my opinion, he hasn't succeeded. Unfortunately it was a big gamble, and it hasn't played out.

THE ROLE OF PRINCIPALS

Question: This forum is being sponsored by the Council of Supervisors and Administrators, which represent principals, assistant principals and other supervisors. This question deals with their roles and their issues. The union believes that the new system has given principals more responsibilities for managing the budget and instruction in their schools and holds them more accountable for the success or failure of their schools, but that it provides them with less support to do this harder job. Do you believe the current system provides too little support to principals and if so what would you specifically change in their behalf?

Steve Shaw: I believe there are a couple of issues surrounding that question. One of the things, which I was speaking to a woman in the audience about, was the decision to remove the supervisors of special education and to put that straight in the lap of the principal. Oftentimes, the principal doesn't have a huge amount of experience in the area of special education and that's on top of all the other things that a principal needs to do. Special education is too important, too difficult, and too complex to treat in such a cavalier type of way. .

When you look at things such as the budget, currently from reading [[CSA President]] Jill Levy's testimony to the City Council, about 90 percent of the principals' budget is fixed, yet this administration keeps saying there's more autonomy -- even though they had to create special autonomy zones in order to give people the autonomy. I would seek to make the budget as discretionary as possible - I understand that. Obviously. a huge part of the expense is fixed with teacher salaries and staff salaries. but I would seek to move the number down from 90 percent to 70 percent.

In terms of accountability, it's very difficult when you are the CEO of a school and you don't have hiring and firing authority. And that's one thing that I would seek to address. I would put that into the hands of principals. They are the ones who are responsible. That's where the decision needs to be made. It can't be made through all sorts of appeals processes and the like. It can't be made from the Department of Education. It needs to be in the principals' hands, and that what I'll do as mayor.

Virginia Fields: I would certainly look to create support systems within the school starting with assistant principals. I would also work with the principals in terms of making decisions around staff development and the time at which that occurs. I've talked with a number of principals and they have informed me that staff development occurs twice a month at three o'clock after school and they are expected to be there to be a part of it. Yet they're not being compensated, and it's additional responsibility being given to them.

We need to look at what other additional responsibilities are being given to the principal, provide the needed support systems starting with assistant principals; provide the relevant staffing that is needed, including qualified teachers who are able to teach in the areas in which the needs exist; and to make sure that the other support systems are there.

Fernando Ferrer: There is much made in the past few years about the recent fad in treating our school systems and other government institutions like somebody's wholly owned subsidiary on a corporate model. And that might be fine for anything else, but not for public education. Not in New York City.

I don't view our school system as General Electric. Our principals, assistant principals, and teachers don't make refrigerators, stoves, and dishwashers. They educate. Elementary and high school principals are not CEOs in any remote sense. Let's get off that right away. They're principal teachers. Their job is to nurture, create, and sustain a viable community of learners that includes not only students but teachers and parents as well. That's their job.

They can't do their job because they have no support from district offices or regional offices. They're spending too much of their time leaving voice mails that are never answered, answering emails that are unnecessary -- and you all know what I mean. That is an enormous waste of enormous talent in our system, an enormous diversion of resources. It's an enormous perversion of what we should be doing to educate every child in every community in every borough of this city.

Gifford Miller: Let me first say that one of the most critical things that we can do in this school system to move it forward is to make sure that we support top quality principals and assistant principals in every single school in this city. Leadership really flows from the top, and parents know what difference a great principal can make in the life of their child.

I think it is absolutely true that this chancellor and the Department of Education have given a great deal more accountability in words and terms to principals but none of the actual responsibility, the ability to get things done. I'll give you an example of what I mean: School violence. It's a huge problem. This mayor and this chancellor have announced two separate zero tolerance policies since taking office. And we still don't have zero tolerance.

The simple reason is that the same time that they're telling principals, "You've got to have zero tolerance." They're also telling them that, if you suspend too many children, we'll fire you. And then they don't even give the principals the responsibility to crease safe environments. The school safety agents work for the local police supervisor instead of the principal of that school. So the principal says, "I need you on the second floor during third period because there's a disturbance between Class A and Class B." The safety agent says, "My supervisor told me to stare at this door and I can't move."

We have to change that. That is a problem of management and we have to change that by making sure that if we're going to give principals and assistant principals the accountability, as we should, to give them the responsibility and the ability to get the job done.

Thomas Ognibene: I come from both a public school background as a student and as someone whose wife is a school teacher and mother was a principal, and so from a private and parochial school background where I serve as a trustee of a large Catholic high school in New York. What I see is that there are certain benefits in the way that we run the [private] school that I think would be very beneficial to the people in the public school system.

First of all, we turn over control of the school to the principal and we provide the assistance so the principal can get the job done. The non-educational aspects of the school, there are personnel in the school who can handle that but they answer to the principal. The principal controls the safety and security personnel, and the principal is the integral component of negotiating a contract with the teachers in that school.

The principals in the schools have to have control of the budget. Most of all they have to have a contract that makes it conducive for them to administer and direct the person in the school so that they can get the best results. We don't have that. We want the principal to be responsible for the education of the children in the school, but we don't give them the options or the authority to administer the school fully.

FUROR AT P.S. 34

Question: Do you think the New York City Department of Education has been quick enough to act in the case of P.S. 34 in Queens [where an administrator allegedly insulted Haitian students, and forced them to sit on the floor and eat with their hands]? How would you balance the concerns of parents against the rights of principals?

Virginia Fields: As I read about the incident and have been hearing over the past couple of days it certainly is something that I find very disturbing, as I know all of you do. I think that everyone expects their child to be able to go to school, be treated with respect, with dignity and not be subjected to the kinds of allegations the reports as we heard them.

Having said that, I think it is incumbent upon the chancellor and the school to immediately get involved in terms of an investigation. You do not allow this to continue and allow it to be played out in the papers. As a mayor, I would have instructed the chancellor to immediately get involved with the situation and based on the reports, if necessary, to remove the principal and/or teacher if the facts warrant it while the review took place. I think the emotions behind this as it is continuing to escalate is causing tremendous difficulties in that community. If the report is not substantiated, bring the community together so that the issue can be dealt with out front.

I would expect that over the next couple of days more specific steps will have to be taken, and I think that the chancellor and the mayor should be at the forefront of making sure that actions are taken.

Fernando Ferrer: The events in that school were troubling and rise to a level of seriousness that demands the chancellor and the office of the special schools investigator be on site. Be on site to investigate, be on site to make a report, not only to the parents, but to the school community as well. And that's something that should have been going on right now. In fact, with the passage of a few days, why isn't that report already made to the community? Why isn't that report already made to school officials? Why isn't that report already made to the mayor and the schools chancellor?

Gifford Miller: First of all, the chancellor is responsible for the conduct of everything that goes o in the schools. And so the authority there stops at the top. He in this case needs to take responsibility for what's occurred and make sure the children in that school and their rights are being adequately protected.

To answer your question directly, I would balance the concerns by placing the highest priority on the children of that school, which is not to say that the principal or any of the other associated school personnel don't have due process rights. They do, but we need to have a system where the chancellor and the mayor can intervene to protect children and to protect the school community. Clearly, a very swift investigation needs to be concluded so that everybody's rights can be protected and so that the children in that school can go back to learning, the teachers back to teaching, and the principal back to directing the school.

HOW MUCH MAYORAL CONTROL?

Question: Let me follow up briefly on a pattern that I think I've heard here tonight. You all are for mayoral control of schools but you all seem to want to give some of that control away, including to the education advisory panel, which replaced the old Board of Education. So I'd like to know from each of you just how much power to you would you give to the education advisory council.

Steve Shaw: I think it should still be an advisory panel in nature. The buck needs to stop with the mayor. However, it can't be a rubber stamp as it currently is. New York City schools are too important to give to just one person's opinion -- or two people's opinion, which is really what the case is now. There needs to be significant engagement among a variety of constituencies, not only our administrators but parents and students as well. What I mentioned before was reforming the panel -- keeping it advisory in nature but what we would do is to make sure that we have meetings every month, which everyone would have to attend…

Question: Could they overrule you on anything if you were mayor? Mr. Ognibene, could they overrule you?

Thomas Ognibene: If I were mayor, nobody would overrule me. That's the whole point of being mayor, isn't it? I don't want to give any control back to the education panel. My control flows down directly to the principals and the schools. I may be the CEO, but I know that the people that are operating out in the field are the ones that are going to get the job done and get education done. I want to empower them, and they could answer to me through the chancellor.

Question: Borough President Fields, you specifically said the education panel is a rubber stamp. Do you want something more checking your power as mayor?

Virginia Fields: It was not about giving control to them but being inclusive, making sure that they were able to function in the roles in which they have been appointed, making sure that they are a part of making decisions. It also means communicating with them prior to meetings so you don't go to a meeting not knowing the outcome of votes, because you have engaged them and you have been having those conversations. So, it is about listening, it is about opening up a process so that their roles are fully implemented and that they are a part of a system. As mayor, I would make the decisions.

Question: There was one well-known incident where the mayor dismissed a number of the members who were going to vote with the majority to overrule him a key decision [on not promoting third graders who failed a standardized test]. Would you have acted differently?

Virginia Fields: I would not have had to act differently because I would have been involved in having discussions with those board members. The issues that they raised are the same results that came out of that process. That was not looking to evaluate students just on the bass of standardized tests, but making sure that other things were looked at. How has the student done in the class up until that point? What input can the parent make? What additional advice can teachers and principals make?

Question: You said you wouldn't have had to dismiss them. I guess you would have convinced them? But what if they still disagreed with you? Would you have let them vote you down?

Virginia Fields: I think that working on those issues the important thing is to include, to engage, to listen. Through that process, I am confident that we can reach common ground.

Gifford Miller: If I can't get a panel of people that I appoint to agree with something that I'm proposing then I have a serious problem and I ought to evaluate my policy. In this case, the mayor should have reevaluated his policy.